- Privacy Policy

Home » Critical Analysis – Types, Examples and Writing Guide

Critical Analysis – Types, Examples and Writing Guide

Table of Contents

Critical Analysis

Definition:

Critical analysis is a process of examining a piece of work or an idea in a systematic, objective, and analytical way. It involves breaking down complex ideas, concepts, or arguments into smaller, more manageable parts to understand them better.

Types of Critical Analysis

Types of Critical Analysis are as follows:

Literary Analysis

This type of analysis focuses on analyzing and interpreting works of literature , such as novels, poetry, plays, etc. The analysis involves examining the literary devices used in the work, such as symbolism, imagery, and metaphor, and how they contribute to the overall meaning of the work.

Film Analysis

This type of analysis involves examining and interpreting films, including their themes, cinematography, editing, and sound. Film analysis can also include evaluating the director’s style and how it contributes to the overall message of the film.

Art Analysis

This type of analysis involves examining and interpreting works of art , such as paintings, sculptures, and installations. The analysis involves examining the elements of the artwork, such as color, composition, and technique, and how they contribute to the overall meaning of the work.

Cultural Analysis

This type of analysis involves examining and interpreting cultural artifacts , such as advertisements, popular music, and social media posts. The analysis involves examining the cultural context of the artifact and how it reflects and shapes cultural values, beliefs, and norms.

Historical Analysis

This type of analysis involves examining and interpreting historical documents , such as diaries, letters, and government records. The analysis involves examining the historical context of the document and how it reflects the social, political, and cultural attitudes of the time.

Philosophical Analysis

This type of analysis involves examining and interpreting philosophical texts and ideas, such as the works of philosophers and their arguments. The analysis involves evaluating the logical consistency of the arguments and assessing the validity and soundness of the conclusions.

Scientific Analysis

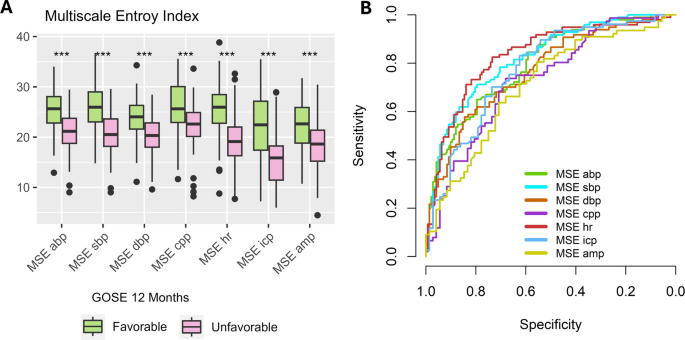

This type of analysis involves examining and interpreting scientific research studies and their findings. The analysis involves evaluating the methods used in the study, the data collected, and the conclusions drawn, and assessing their reliability and validity.

Critical Discourse Analysis

This type of analysis involves examining and interpreting language use in social and political contexts. The analysis involves evaluating the power dynamics and social relationships conveyed through language use and how they shape discourse and social reality.

Comparative Analysis

This type of analysis involves examining and interpreting multiple texts or works of art and comparing them to each other. The analysis involves evaluating the similarities and differences between the texts and how they contribute to understanding the themes and meanings conveyed.

Critical Analysis Format

Critical Analysis Format is as follows:

I. Introduction

- Provide a brief overview of the text, object, or event being analyzed

- Explain the purpose of the analysis and its significance

- Provide background information on the context and relevant historical or cultural factors

II. Description

- Provide a detailed description of the text, object, or event being analyzed

- Identify key themes, ideas, and arguments presented

- Describe the author or creator’s style, tone, and use of language or visual elements

III. Analysis

- Analyze the text, object, or event using critical thinking skills

- Identify the main strengths and weaknesses of the argument or presentation

- Evaluate the reliability and validity of the evidence presented

- Assess any assumptions or biases that may be present in the text, object, or event

- Consider the implications of the argument or presentation for different audiences and contexts

IV. Evaluation

- Provide an overall evaluation of the text, object, or event based on the analysis

- Assess the effectiveness of the argument or presentation in achieving its intended purpose

- Identify any limitations or gaps in the argument or presentation

- Consider any alternative viewpoints or interpretations that could be presented

- Summarize the main points of the analysis and evaluation

- Reiterate the significance of the text, object, or event and its relevance to broader issues or debates

- Provide any recommendations for further research or future developments in the field.

VI. Example

- Provide an example or two to support your analysis and evaluation

- Use quotes or specific details from the text, object, or event to support your claims

- Analyze the example(s) using critical thinking skills and explain how they relate to your overall argument

VII. Conclusion

- Reiterate your thesis statement and summarize your main points

- Provide a final evaluation of the text, object, or event based on your analysis

- Offer recommendations for future research or further developments in the field

- End with a thought-provoking statement or question that encourages the reader to think more deeply about the topic

How to Write Critical Analysis

Writing a critical analysis involves evaluating and interpreting a text, such as a book, article, or film, and expressing your opinion about its quality and significance. Here are some steps you can follow to write a critical analysis:

- Read and re-read the text: Before you begin writing, make sure you have a good understanding of the text. Read it several times and take notes on the key points, themes, and arguments.

- Identify the author’s purpose and audience: Consider why the author wrote the text and who the intended audience is. This can help you evaluate whether the author achieved their goals and whether the text is effective in reaching its audience.

- Analyze the structure and style: Look at the organization of the text and the author’s writing style. Consider how these elements contribute to the overall meaning of the text.

- Evaluate the content : Analyze the author’s arguments, evidence, and conclusions. Consider whether they are logical, convincing, and supported by the evidence presented in the text.

- Consider the context: Think about the historical, cultural, and social context in which the text was written. This can help you understand the author’s perspective and the significance of the text.

- Develop your thesis statement : Based on your analysis, develop a clear and concise thesis statement that summarizes your overall evaluation of the text.

- Support your thesis: Use evidence from the text to support your thesis statement. This can include direct quotes, paraphrases, and examples from the text.

- Write the introduction, body, and conclusion : Organize your analysis into an introduction that provides context and presents your thesis, a body that presents your evidence and analysis, and a conclusion that summarizes your main points and restates your thesis.

- Revise and edit: After you have written your analysis, revise and edit it to ensure that your writing is clear, concise, and well-organized. Check for spelling and grammar errors, and make sure that your analysis is logically sound and supported by evidence.

When to Write Critical Analysis

You may want to write a critical analysis in the following situations:

- Academic Assignments: If you are a student, you may be assigned to write a critical analysis as a part of your coursework. This could include analyzing a piece of literature, a historical event, or a scientific paper.

- Journalism and Media: As a journalist or media person, you may need to write a critical analysis of current events, political speeches, or media coverage.

- Personal Interest: If you are interested in a particular topic, you may want to write a critical analysis to gain a deeper understanding of it. For example, you may want to analyze the themes and motifs in a novel or film that you enjoyed.

- Professional Development : Professionals such as writers, scholars, and researchers often write critical analyses to gain insights into their field of study or work.

Critical Analysis Example

An Example of Critical Analysis Could be as follow:

Research Topic:

The Impact of Online Learning on Student Performance

Introduction:

The introduction of the research topic is clear and provides an overview of the issue. However, it could benefit from providing more background information on the prevalence of online learning and its potential impact on student performance.

Literature Review:

The literature review is comprehensive and well-structured. It covers a broad range of studies that have examined the relationship between online learning and student performance. However, it could benefit from including more recent studies and providing a more critical analysis of the existing literature.

Research Methods:

The research methods are clearly described and appropriate for the research question. The study uses a quasi-experimental design to compare the performance of students who took an online course with those who took the same course in a traditional classroom setting. However, the study may benefit from using a randomized controlled trial design to reduce potential confounding factors.

The results are presented in a clear and concise manner. The study finds that students who took the online course performed similarly to those who took the traditional course. However, the study only measures performance on one course and may not be generalizable to other courses or contexts.

Discussion :

The discussion section provides a thorough analysis of the study’s findings. The authors acknowledge the limitations of the study and provide suggestions for future research. However, they could benefit from discussing potential mechanisms underlying the relationship between online learning and student performance.

Conclusion :

The conclusion summarizes the main findings of the study and provides some implications for future research and practice. However, it could benefit from providing more specific recommendations for implementing online learning programs in educational settings.

Purpose of Critical Analysis

There are several purposes of critical analysis, including:

- To identify and evaluate arguments : Critical analysis helps to identify the main arguments in a piece of writing or speech and evaluate their strengths and weaknesses. This enables the reader to form their own opinion and make informed decisions.

- To assess evidence : Critical analysis involves examining the evidence presented in a text or speech and evaluating its quality and relevance to the argument. This helps to determine the credibility of the claims being made.

- To recognize biases and assumptions : Critical analysis helps to identify any biases or assumptions that may be present in the argument, and evaluate how these affect the credibility of the argument.

- To develop critical thinking skills: Critical analysis helps to develop the ability to think critically, evaluate information objectively, and make reasoned judgments based on evidence.

- To improve communication skills: Critical analysis involves carefully reading and listening to information, evaluating it, and expressing one’s own opinion in a clear and concise manner. This helps to improve communication skills and the ability to express ideas effectively.

Importance of Critical Analysis

Here are some specific reasons why critical analysis is important:

- Helps to identify biases: Critical analysis helps individuals to recognize their own biases and assumptions, as well as the biases of others. By being aware of biases, individuals can better evaluate the credibility and reliability of information.

- Enhances problem-solving skills : Critical analysis encourages individuals to question assumptions and consider multiple perspectives, which can lead to creative problem-solving and innovation.

- Promotes better decision-making: By carefully evaluating evidence and arguments, critical analysis can help individuals make more informed and effective decisions.

- Facilitates understanding: Critical analysis helps individuals to understand complex issues and ideas by breaking them down into smaller parts and evaluating them separately.

- Fosters intellectual growth : Engaging in critical analysis challenges individuals to think deeply and critically, which can lead to intellectual growth and development.

Advantages of Critical Analysis

Some advantages of critical analysis include:

- Improved decision-making: Critical analysis helps individuals make informed decisions by evaluating all available information and considering various perspectives.

- Enhanced problem-solving skills : Critical analysis requires individuals to identify and analyze the root cause of a problem, which can help develop effective solutions.

- Increased creativity : Critical analysis encourages individuals to think outside the box and consider alternative solutions to problems, which can lead to more creative and innovative ideas.

- Improved communication : Critical analysis helps individuals communicate their ideas and opinions more effectively by providing logical and coherent arguments.

- Reduced bias: Critical analysis requires individuals to evaluate information objectively, which can help reduce personal biases and subjective opinions.

- Better understanding of complex issues : Critical analysis helps individuals to understand complex issues by breaking them down into smaller parts, examining each part and understanding how they fit together.

- Greater self-awareness: Critical analysis helps individuals to recognize their own biases, assumptions, and limitations, which can lead to personal growth and development.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Cluster Analysis – Types, Methods and Examples

Data Collection – Methods Types and Examples

Delimitations in Research – Types, Examples and...

Discriminant Analysis – Methods, Types and...

Research Process – Steps, Examples and Tips

Research Design – Types, Methods and Examples

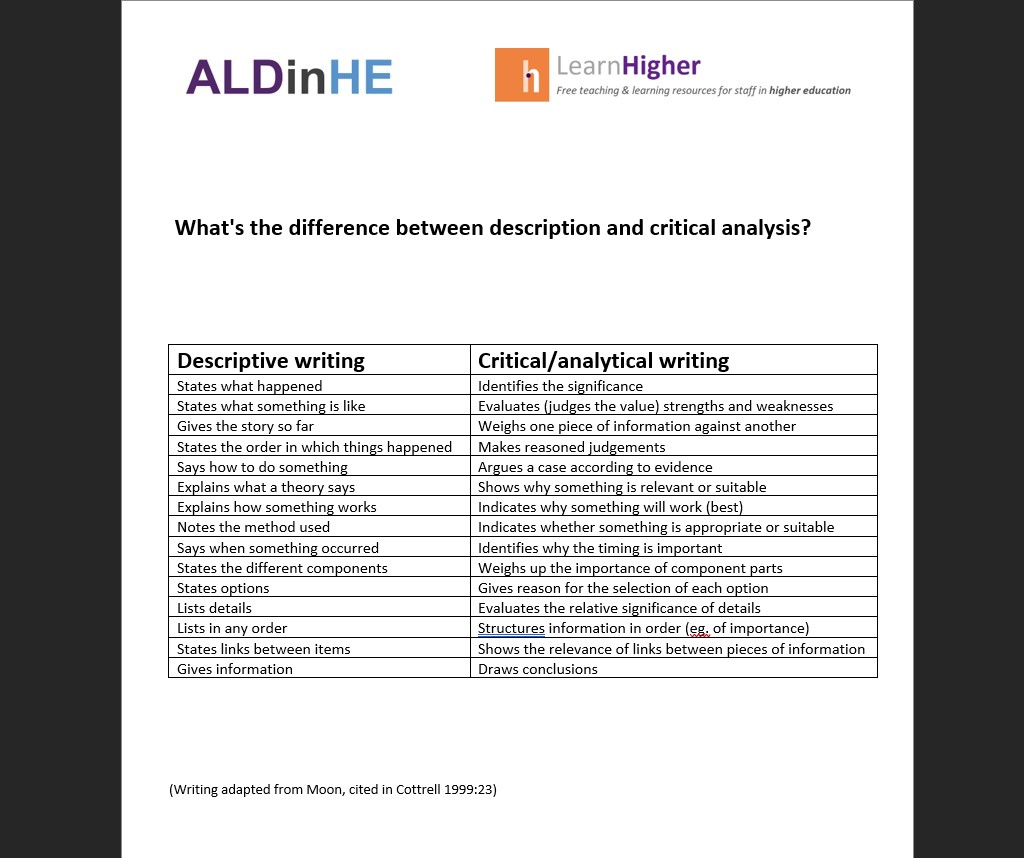

Critical writing: Descriptive vs critical

- Managing your reading

- Source reliability

- Critical reading

- Descriptive vs critical

- Deciding your position

- The overall argument

- Individual arguments

- Signposting

- Alternative viewpoints

- Critical thinking videos

Jump to content on this page:

“Descriptions: they report information about something, but they don't perform any kind of reasoning - and nor do they pass judgement on or analyse the information they contain.” Tom Chatfield, Critical Thinking

Many of students are told that their writing is too descriptive and not critical enough. But what does this actually mean? This page describes both sorts of writing so that you can see the difference and gives examples of how to make your writing less descriptive and more critical.

Descriptive versus critical writing

Descriptive writing.

This is an essential element of academic writing but it is used to set the background and to provide evidence rather than to develop argument. When writing descriptively you are informing your reader of things that they need to know to understand and follow your argument but you are not transforming that information in any way. This is usually writing about things you have read, done (often as part of reflective writing ) or observed.

Critical writing

When writing critically, you are developing a reasoned argument and participating in academic debate. Essentially you are persuading your reader of your position on the topic at hand. This is about taking the information you have described and using it in some way. This could be writing things like:

- why it is relevant to your argument,

- how it relates to other literature,

- how it relates to the focus of your assignment

- how a theory can be put into practice,

- why it is significant,

- why you are not persuaded by it,

- how it leads you to reach your conclusion.

The University of Leeds gives some good examples of descriptive vs critical writing on their website: Critical writing .

Table comparing functions of descriptive and critical writing

The table below gives more examples of the difference between descriptive and critical writing

Persuade don't inform

To summarise, when you are writing critically you are persuading the reader of your position on something whereas when you are writing descriptively you are just informing them of something you have read, observed or done. We take you through the process of deciding on, and demonstrating your position in your writing on the next page: Deciding your position .

- << Previous: Critical reading

- Next: Deciding your position >>

- Last Updated: Feb 13, 2024 10:53 AM

- URL: https://libguides.hull.ac.uk/criticalwriting

- Login to LibApps

- Library websites Privacy Policy

- University of Hull privacy policy & cookies

- Website terms and conditions

- Accessibility

- Report a problem

Chapter 6: Thinking and Analyzing Rhetorically

6.8 What is Critical Analysis

Julie A. Townsend

What is critical analysis?

Critical analysis is a term that students may hear often, especially as they progress through university courses and move into the twenty-first century workforce. Teachers and future employers want to see critical analysis applied in a variety of ways. Every context will have different ways that are standard for critical analysis of situations, data, and problems. Broadly, critical thinking is a way of looking at a situation that goes beyond first impressions and cliches. This section will describe specific techniques for critical analysis that can be used across different situations, especially for discovering more about writing and topics relevant to writing studies.

How can I do critical analysis?

William Thelin in Writing Without Formulas offers eight concrete ways to perform critical analysis: “interrogating the obvious,” “seeing patterns,” “finding what’s not there,” looking at “race, class, and gender,” “twisting the cliché,” “unearthing agendas,” and asking, “who profits?” (28—47). The following sections are originally derived from Thelin’s categories but are modified to better study writing in context, since many first-year writing classes at CSU following the “writing-about-writing” theme (as described by Downs and Wardle in “Teaching about writing, righting misconceptions”).

This chapter will work from an example scenario in which the writer aims to detail and understand the reading, writing, communication, and education that is taking place in one online asynchronous course. The writer’s originating research question is: What kinds of reading, writing, communication, and education takes place in this one asynchronous course? After the writer has written down their initial thoughts on the course and how communication works in the specific situation, they can use the following guidelines to write more and dig deeper into the context they are studying.

Detailing the Basics

Before the writer can use critical analysis, they need to clearly identify and describe details in the context. Details can help the writer more clearly understand the situation they are studying. Details are also necessary for readers to follow along with the critical analysis that the writer is performing.

Questions to help the writer detail the basics for studying communication in one asynchronous online course

- What did the instructor write?

- What are the students expected to write?

- Where, how, and why are they expected to write?

- How does communication between students occur?

- What about communication with the teacher?

- How is the course organized?

- What kinds of resources are used in the course?

- Are students expected to read every word on the course page? What words are they required to read?

- What kinds of external documents does the teacher expect students to use?

When the writer begins critical analysis with details of the basic situation, nothing is too mundane or obvious to skip over in the writing process. Specific details help the context come to life for both the writer and the readers. Writers should aim to draw a living picture of the situation. Then, from that living picture, the writer can work to analyze the situation in a more complete manner using the following suggestions.

Look for clusters, patterns, and coordination

After the writer has a drawn a clear picture for themselves and for the reader of what kinds of reading, writing, and communication are going on in the context they are describing, they can look for connections and links among these texts, resources, and people.

- A cluster includes technologies, people, texts, or ideas that exist near one another in a situation.

- o Clusters and patterns can help writers see the relationships between different elements and can help the writer see and understand a situation differently.

- o Coordination can help the writer see how separate acts of reading, writing, and communication work together to complete larger tasks.

Questions to help the writer find clusters, patterns, and coordination while studying communication in one asynchronous online course

- How does the student in the course group together texts to perform a task?

- Has the instructor supplied readings that the students need to write about?

- How does the student use assigned texts (possibly with other texts or technologies) in their writing process?

- What about external texts that the student needs to gather? How do those texts work into their writing process?

- Are certain texts often grouped together in the instruction or writing process?

- What kinds of resources do students tie together to complete assignments?

- How do technologies outside of the course (like using social media or messaging classmates) work in conjunction with other texts and resources when the student is completing course work?

A deeper look at coordination

In writing studies, researchers can look for how texts are used in coordination with one another to learn more about the writing process and to describe how exactly people write and get work done. The concept of textual coordination (Slattery, “Technical writing as textual coordination”; Pigg, “Coordinating constant invention”) helps researchers to better understand how writers use resources (from computer programs to emails to syllabi to dictionaries) to write.

For research writing especially, writers tend to have multiple tabs or windows open on their computers with articles, websites, and the word processor they are using. The tying together of these resources by the writer is textual coordination. According to Shaun Slattery in “Undistributing Work through Writing”, the study of textual coordination emerged from researchers looking into how distributed work takes place in environments that are often mediated by computers (313). Many twenty-first century knowledge-working careers use a model of distributed work and rely on “the ability to identify, rearrange, circulate, abstract, and broker information” (Johnson-Eilola qtd. on Slattery 312). While most first-year writers may not have much career experience in knowledge working, they do have experience tying together resources and technologies. For example: reading a homework assignment and taking notes in a separate document and then using those texts in an essay is an example of textual coordination.

Looking through the lens of intersectionality

This section is borrowed (using Creative Commons Licensing) from “Unit I: An Introduction to Women, Gender, and Sexuality Studies” in the open-education resource textbook An Introduction to Women, Gender, and Sexuality Studies . “Within intersectional frameworks, race, class, gender, sexuality, age, ability, and other aspects of identity are considered mutually constitutive; that is, people experience these multiple aspects of identity simultaneously and the meanings of different aspects of identity are shaped by one another. In other words, notions of gender and the way a person’s gender is interpreted by others are always impacted by notions of race and the way that person’s race is interpreted. For example, a person is never received as just a woman, but how that person is racialized impacts how the person is received as a woman. So, notions of blackness, brownness, and whiteness always influence gendered experience, and there is no experience of gender that is outside of an experience of race. In addition to race, gendered experience is also shaped by age, sexuality, class, and ability; likewise, the experience of race is impacted by gender, age, class, sexuality, and ability.” For more information on intersectionality, read more in their chapter and textbook .

By asking questions about race, class, gender, ability, sexuality, and the intersections between these categories, writers can perform more critical analysis.

Questions to help the writer perform analysis with intersectional lenses while studying communication in one asynchronous online course

- What is the race, class, gender, sexuality, and ability of the authors of the readings we are assigned? How do these categories intersect in the lives of the authors?

- Do the statistics of the authors assigned for students to read match with the demographics of experts in the field?

- How are race, class, gender, ability, and sexuality distributed in the field overall?

- If there are inequalities in the demographics of professionals in the field, are there initiatives that work towards inviting more diversity into the field?

- What kinds of reading, writing, and communication are missing or different from similar contexts?

- Could resources be added to enhance communication, representation, understanding, or ease of access? What would those resources be?

What could be added?

In this stage of analysis, the writer should take a few steps back from the details of the context they are studying so that they might be able to see what could be added to the environment they are studying . The writer could compare the context they are studying to other contexts to help see what might be missing.

Questions to help the writer perform analysis on what could be added?

If the writer is performing critical analysis in a context where the previously discussed categories might not apply, “What is Critical Analysis?” by The University of Bradford offers a broad framework for critical analysis that can be applied beyond topics relevant to writing, reading, and communication. The University of Bradford describes critical analysis as part of the process that includes: “description,” “analysis,” and “evaluation” (2). For description, it suggests that writers focus on answering questions starting with “what”, “where”, “who”, and “when” (2). For the analysis stage, it suggests answering “how”, “why”, and “what if?” (2). Evaluation includes “so what?” and “what next?” Writers can use the categories outlined here to perform critical analysis that adds depth, texture, and details to thoughts and observations.

Works Cited

Downs, Douglas, and Elizabeth Wardle. “Teaching about writing, righting misconceptions:(Re)envisioning” first-year composition” as” Introduction to Writing Studies”.” College composition and communication (2007): 552-584.

Kang, Miliann, Donovan Lessard, Laura Heston, and Sonny Nordmarken. Introduction to Women, Gender, and Sexuality Studies . UMassAmherst Libraries, Pressbooks.

Pigg, Stacey. “Coordinating constant invention: Social media’s role in distributed work.” Technical Communication Quarterly 23.2 (2014): 69-87.

Slattery, Shaun. “Technical writing as textual coordination: An argument for the value of writers’ skill with information technology.” Technical Communication 52.3 (2005): 353.

Slattery, Shaun. “Undistributing work through writing: How technical writers manage texts in complex information environments.” Technical Communication Quarterly 16.3 (2007): 311-325.

Thelin, William. Writing Without Formulas. Second edition. Cengage, 2009. “What is Critical Analysis?” Academic Skills Advice. The University of Bradford. Accessed 17 October 2019.

A Guide to Rhetoric, Genre, and Success in First-Year Writing by Julie A. Townsend is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Feedback/Errata

Comments are closed.

- The Open University

- Guest user / Sign out

- Study with The Open University

My OpenLearn Profile

Personalise your OpenLearn profile, save your favourite content and get recognition for your learning

About this free course

Become an ou student, download this course, share this free course.

Start this free course now. Just create an account and sign in. Enrol and complete the course for a free statement of participation or digital badge if available.

4 The difference between descriptive and critical writing

It is important that you understand the difference between descriptive writing and adopting a critical stance, and are able to show clear evidence of your understanding in your writing. Table 2 provides some examples of this.

Writing a Critical Analysis

What is in this guide, definitions, putting it together, tips and examples of critques.

- Background Information

- Cite Sources

Library Links

- Ask a Librarian

- Library Tutorials

- The Research Process

- Library Hours

- Online Databases (A-Z)

- Interlibrary Loan (ILL)

- Reserve a Study Room

- Report a Problem

This guide is meant to help you understand the basics of writing a critical analysis. A critical analysis is an argument about a particular piece of media. There are typically two parts: (1) identify and explain the argument the author is making, and (2), provide your own argument about that argument. Your instructor may have very specific requirements on how you are to write your critical analysis, so make sure you read your assignment carefully.

Critical Analysis

A deep approach to your understanding of a piece of media by relating new knowledge to what you already know.

Part 1: Introduction

- Identify the work being criticized.

- Present thesis - argument about the work.

- Preview your argument - what are the steps you will take to prove your argument.

Part 2: Summarize

- Provide a short summary of the work.

- Present only what is needed to know to understand your argument.

Part 3: Your Argument

- This is the bulk of your paper.

- Provide "sub-arguments" to prove your main argument.

- Use scholarly articles to back up your argument(s).

Part 4: Conclusion

- Reflect on how you have proven your argument.

- Point out the importance of your argument.

- Comment on the potential for further research or analysis.

- Cornell University Library Tips for writing a critical appraisal and analysis of a scholarly article.

- Queen's University Library How to Critique an Article (Psychology)

- University of Illinois, Springfield An example of a summary and an evaluation of a research article. This extended example shows the different ways a student can critique and write about an article

- Next: Background Information >>

- Last Updated: Feb 14, 2024 4:33 PM

- URL: https://libguides.pittcc.edu/critical_analysis

- Join ALDinHE

Association for Learning Development in Higher Education

What’s the difference between description and critical analysis?

- Description

- Reviews (0)

The difference between descriptive and critical writing

It is important that students understand the difference between descriptive writing and adopt a critical stance, and are able to show clear evidence of their understanding in their writing. This downloadable resource provides some examples of this.

There are no reviews yet.

Only logged in customers who have purchased this product may leave a review.

Additional Resource Information

View resources by author(s): LearnHigher

Institution(s): LearnHigher

License: Creative Commons licence (4.0)

Categories: LearnHigher Resources | Critical Thinking and Reflection

Published: 26/01/2012

Resource Categories

- Cambridge Libraries

Study Skills

Critical analysis: home.

- Reading Critically

What is Critical Analysis?

Analysis is a word that is also often used when taking a critical approach to something. It could be that you look at some evidence and if you think it is good quality, you may choose to include that in your essay or writing to help support your argument. When you have analysed different sets of evidence you may synthesize all the ideas gathered from multiple sources bringing together the relevant information into a different argument or idea.

To evaluate something or someone, you think and consider it or them in order to make a judgment about it/them; this could be as simple as how good or bad they are. When you critically evaluate something or someone you consider how judgments vary from different perspectives and how some judgments are stronger than others. This often means creating an objective, reasoned argument for your overall case, based on the evaluation from different perspectives.

Taking a critical approach when you are studying involves constantly asking questions and keeping an open mind.

- Next: Reading Critically >>

- Last Updated: Aug 9, 2023 11:57 AM

- URL: https://libguides.cam.ac.uk/criticalanalysis

© Cambridge University Libraries | Accessibility | Privacy policy | Log into LibApps

BibGuru Blog

Be more productive in school

- Citation Styles

How to write a critical analysis

Unlike the name implies a critical analysis does not necessarily mean that you are only exploring what is wrong with a piece of work. Instead, the purpose of this type of essay is to interact with and understand a text. Here’s what you need to know to create a well-written critical analysis essay.

What is a critical analysis?

A critical analysis examines and evaluates someone else’s work, such as a book, an essay, or an article. It requires two steps: a careful reading of the work and thoughtful analysis of the information presented in the work.

Although this may sound complicated, all you are doing in a critical essay is closely reading an author’s work and providing your opinion on how well the author accomplished their purpose.

Critical analyses are most frequently done in academic settings (such as a class assignment). Writing a critical analysis demonstrates that you are able to read a text and think deeply about it. However, critical thinking skills are vital outside of an educational context as well. You just don’t always have to demonstrate them in essay form.

How to outline and write a critical analysis essay

Writing a critical analysis essay involves two main chunks of work: reading the text you are going to write about and writing an analysis of that text. Both are equally important when writing a critical analysis essay.

Step one: Reading critically

The first step in writing a critical analysis is to carefully study the source you plan to analyze.

If you are writing for a class assignment, your professor may have already given you the topic to analyze in an article, short story, book, or other work. If so, you can focus your note-taking on that topic while reading.

Other times, you may have to develop your own topic to analyze within a piece of work. In this case, you should focus on a few key areas as you read:

- What is the author’s intended purpose for the work?

- What techniques and language does the author use to achieve this purpose?

- How does the author support the thesis?

- Who is the author writing for?

- Is the author effective at achieving the intended purpose?

Once you have carefully examined the source material, then you are ready to begin planning your critical analysis essay.

Step two: Writing the critical analysis essay

Taking time to organize your ideas before you begin writing can shorten the amount of time that you spend working on your critical analysis essay. As an added bonus, the quality of your essay will likely be higher if you have a plan before writing.

Here’s a rough outline of what should be in your essay. Of course, if your instructor gives you a sample essay or outline, refer to the sample first.

- Background Information

Critical Analysis

Here is some additional information on what needs to go into each section:

Background information

In the first paragraph of your essay, include background information on the material that you are critiquing. Include context that helps the reader understand the piece you are analyzing. Be sure to include the title of the piece, the author’s name, and information about when and where it was published.

“Success is counted sweetest” is a poem by Emily Dickinson published in 1864. Dickinson was not widely known as a poet during her lifetime, and this poem is one of the first published while she was alive.

After you have provided background information, state your thesis. The thesis should be your reaction to the work. It also lets your reader know what to expect from the rest of your essay. The points you make in the critical analysis should support the thesis.

Dickinson’s use of metaphor in the poem is unexpected but works well to convey the paradoxical theme that success is most valued by those who never experience success.

The next section should include a summary of the work that you are analyzing. Do not assume that the reader is familiar with the source material. Your summary should show that you understood the text, but it should not include the arguments that you will discuss later in the essay.

Dickinson introduces the theme of success in the first line of the poem. She begins by comparing success to nectar. Then, she uses the extended metaphor of a battle in order to demonstrate that the winner has less understanding of success than the loser.

The next paragraphs will contain your critical analysis. Use as many paragraphs as necessary to support your thesis.

Discuss the areas that you took notes on as you were reading. While a critical analysis should include your opinion, it needs to have evidence from the source material in order to be credible to readers. Be sure to use textual evidence to support your claims, and remember to explain your reasoning.

Dickinson’s comparison of success to nectar seems strange at first. However the first line “success is counted sweetest” brings to mind that this nectar could be bees searching for nectar to make honey. In this first stanza, Dickinson seems to imply that success requires work because bees are usually considered to be hard-working and industrious.

In the next two stanzas, Dickinson expands on the meaning of success. This time she uses the image of a victorious army and a dying man on the vanquished side. Now the idea of success is more than something you value because you have worked hard for it. Dickinson states that the dying man values success even more than the victors because he has given everything and still has not achieved success.

This last section is where you remind the readers of your thesis and make closing remarks to wrap up your essay. Avoid summarizing the main points of your critical analysis unless your essay is so long that readers might have forgotten parts of it.

In “Success is counted sweetest” Dickinson cleverly upends the reader’s usual thoughts about success through her unexpected use of metaphors. The poem may be short, but Dickinson conveys a serious theme in just a few carefully chosen words.

What type of language should be used in a critical analysis essay?

Because critical analysis papers are written in an academic setting, you should use formal language, which means:

- No contractions

- Avoid first-person pronouns (I, we, me)

Do not include phrases such as “in my opinion” or “I think”. In a critical analysis, the reader already assumes that the claims are your opinions.

Your instructor may have specific guidelines for the writing style to use. If the instructor assigns a style guide for the class, be sure to use the guidelines in the style manual in your writing.

Additional t ips for writing a critical analysis essay

To conclude this article, here are some additional tips for writing a critical analysis essay:

- Give yourself plenty of time to read the source material. If you have time, read through the text once to get the gist and a second time to take notes.

- Outlining your essay can help you save time. You don’t have to stick exactly to the outline though. You can change it as needed once you start writing.

- Spend the bulk of your writing time working on your thesis and critical analysis. The introduction and conclusion are important, but these sections cannot make up for a weak thesis or critical analysis.

- Give yourself time between your first draft and your second draft. A day or two away from your essay can make it easier to see what you need to improve.

Frequently Asked Questions about critical analyses

In the introduction of a critical analysis essay, you should give background information on the source that you are analyzing. Be sure to include the author’s name and the title of the work. Your thesis normally goes in the introduction as well.

A critical analysis has four main parts.

- Introduction

The focus of a critical analysis should be on the work being analyzed rather than on you. This means that you should avoid using first person unless your instructor tells you to do otherwise. Most formal academic writing is written in third person.

How many paragraphs your critical analysis should have depends on the assignment and will most likely be determined by your instructor. However, in general, your critical analysis paper should have three to six paragraphs, unless otherwise stated.

Your critical analysis ends with your conclusion. You should restate the thesis and make closing remarks, but avoid summarizing the main points of your critical analysis unless your essay is so long that readers might have forgotten parts of it.

Make your life easier with our productivity and writing resources.

For students and teachers.

Academic writing

- Thinking about grammar

- Correct punctuation

- Writing in an academic style

Styles of writing

Descriptive writing, analytical writing, reflective writing.

- Effective proof reading

When you’re asked to write an assignment you might immediately think of an essay, and have an idea of the type of writing style that’s required.

This is likely to be a ‘discursive’ style, as often in an essay you’re asked to discuss various theories, ideas and concepts in relation to a given question. For those coming to study maths and science subjects, you might be mistaken in thinking that any guidance on writing styles is not relevant to you.

In reality, you’ll probably be asked to complete a range of different assignments, including reports, problem questions, blog posts, case studies and reflective accounts. So for the mathematicians and scientists amongst you, you’re likely to find that you’ll be expected to write more at university than perhaps you’re used to. You may be asked to write essays, literature reviews or short discussions, in which all the advice on this course, including the advice below, is of relevance. In addition, even writing up your equations or findings will require you to carefully consider your structure and style. Different types of assignment often call for different styles of writing, but within one assignment you might use a variety of writing styles depending on the purpose of that particular section.

Three main writing styles you may come across during your studies are: descriptive , analytical and reflective . These will require you to develop your writing style and perhaps think more deeply about what you’ve read or experienced, in order to make more meaningful conclusions.

The diagram below shows examples of each of these writing styles. It takes as an example a trainee teacher’s experience within a classroom and shows how the writing style develops as they think more deeply about the evidence they are presented with.

All of these forms of writing are needed to write critically . You’ll come across the term critical in lots of contexts during your studies, for example critical thinking, critical writing and critical analysis. Critical writing requires you to:

• view a topic from a variety of angles

• evaluate evidence

• present a clear conclusion

• and reflect on the limitations of your own argument.

So how will you know which writing style is needed in your assignments? As mentioned, most academic assignments will require a certain amount of description but your writing should mainly be analytical and critical. You’ll be given an assignment brief and marking guidelines, which will make clear the expectations with regards to writing style. Make sure you read these carefully before you begin your assignment.

It’s unlikely that you’ll be asked to only write descriptively , though this form of writing is useful in certain sections of reports and essays. You’ll need elements of description in essays before you go on to analyse and evaluate. The description is there to help the reader understand the key principles and for you to set the scene. But description, in this case, needs to be kept to a minimum.

However descriptive writing is often used in the methodology and findings sections of a report, or when completing a laboratory report on an experiment. Here you’re describing (for instance) the methods you adopted so that someone else can replicate them should they need to. Descriptive writing focuses on answering the ‘what?’ ‘when’ and ‘who’ type questions.

Analytical writing style is often called for at university level. It involves reviewing what you’ve read in light of other evidence. Analytical writing shows the thought processes you went through to arrive at a given conclusion and discusses the implications of this. Analytical writing usually follows a brief description and focuses on answering questions like: ‘why?’ ‘how?’ and ‘so what?’

Have a look at our LibGuide on Critical Analysis: Thinking, Reading, and Writing for more in-depth guidance on analytical writing.

Not all writing will require you to write reflectively . However you might be asked to write a reflective account after a work placement or find that at the end of a report it might be appropriate to add some personal observations. This style of writing builds on analysis by considering the learning you’ve gained from practical experience. The purpose of the reflection is to help you to make improvements for the future and, as such, it is a more ‘personal’ form of academic writing often using the first person. Evidence still has a key role in reflective writing; it’s not just about retelling your story and how you felt. And evidence in the case of reflection will include your own personal experience which adds to the discussion. Reflective writing focuses on future improvements and answers questions like ‘what next?’

- Practice-based and reflective learning LibGuide More details on thinking and writing reflectively.

- << Previous: Writing in an academic style

- Next: Effective proof reading >>

- Last Updated: Apr 30, 2024 10:24 AM

- URL: https://libguides.reading.ac.uk/writing

404 Not found

Understanding and solving intractable resource governance problems.

- In the Press

- Conferences and Talks

- Exploring models of electronic wastes governance in the United States and Mexico: Recycling, risk and environmental justice

- The Collaborative Resource Governance Lab (CoReGovLab)

- Water Conflicts in Mexico: A Multi-Method Approach

- Past projects

- Publications and scholarly output

- Research Interests

- Higher education and academia

- Public administration, public policy and public management research

- Research-oriented blog posts

- Stuff about research methods

- Research trajectory

- Publications

- Developing a Writing Practice

- Outlining Papers

- Publishing strategies

- Writing a book manuscript

- Writing a research paper, book chapter or dissertation/thesis chapter

- Everything Notebook

- Literature Reviews

- Note-Taking Techniques

- Organization and Time Management

- Planning Methods and Approaches

- Qualitative Methods, Qualitative Research, Qualitative Analysis

- Reading Notes of Books

- Reading Strategies

- Teaching Public Policy, Public Administration and Public Management

- My Reading Notes of Books on How to Write a Doctoral Dissertation/How to Conduct PhD Research

- Writing a Thesis (Undergraduate or Masters) or a Dissertation (PhD)

- Reading strategies for undergraduates

- Social Media in Academia

- Resources for Job Seekers in the Academic Market

- Writing Groups and Retreats

- Regional Development (Fall 2015)

- State and Local Government (Fall 2015)

- Public Policy Analysis (Fall 2016)

- Regional Development (Fall 2016)

- Public Policy Analysis (Fall 2018)

- Public Policy Analysis (Fall 2019)

- Public Policy Analysis (Spring 2016)

- POLI 351 Environmental Policy and Politics (Summer Session 2011)

- POLI 352 Comparative Politics of Public Policy (Term 2)

- POLI 375A Global Environmental Politics (Term 2)

- POLI 350A Public Policy (Term 2)

- POLI 351 Environmental Policy and Politics (Term 1)

- POLI 332 Latin American Environmental Politics (Term 2, Spring 2012)

- POLI 350A Public Policy (Term 1, Sep-Dec 2011)

- POLI 375A Global Environmental Politics (Term 1, Sep-Dec 2011)

Distinguishing between description and analysis in academic writing

When I switched from chemical engineering (my undergraduate degree) to political science and human geography (my doctoral degree), I went through economics of technical change and international marketing (my Masters). But the chemical engineering component was still very strong during my Masters. I remember reading comments from a professor’s marker (yes, my professor didn’t even grade my essay!) saying “ lacks analysis “.

WHAT THE HELL IS ANALYSIS IF NOT WHAT I AM WRITING THEN?! Now, when I read student essays, or Masters/PhD theses, I find myself writing similar comments: “ this is a very good description, but lacks real analysis “. I asked both the Political Scientists Facebook group (of which I’m proud of being part of) and the Research Companion Facebook group (a fantastic resource created by Dr. Petra Boynton, author of the book “The Research Companion”).

I received A LOT of really good feedback on both groups (who said that Facebook was only good for posting photos of your kids?) which I am detailing here (I’ve asked for permission to attribute whoever recommended a particular book or reading).

Political Scientists

- The Craft of Research . (by Booth et al) Shane Gunderson, Cheryl Van Den Handel, and Jay De Sart recommended this book, which I have read and own. This is a book on how to undertake social science research, and it’s one I definitely recommend too.

- They Say, I Say . Omar Wasow recommended this book, seconded by Jackie Gehring. Erin Ackerman, author of the “Analyze This: Writing in the Social Sciences” chapter of “They Say, I Say” book, mentioned that her chapter Chapter 13 is focused on social sciences’ writing and a few political science examples.

- Empirical Research in Political Science (by Leanne Powner). I had heard of Leanne’s work before and I *thought* I had a copy of this book, but I think it’s one of the ones I lost at MPSA 2016 (don’t ask). So, I’ve requested an examination copy and will report back once I’ve read it.

- Writing a Research Paper in Political Science: A Practical Guide to Inquiry, Structure, and Method (by Lisa Baglioni). Recommended by Mirya Holman, Mary Anne Mendoza, and Jay De Sart. I don’t own this book either, but the comments I read were that the book walks the student through the process of writing a research paper quite clearly. I’ve also requested an examination copy, and will report back once I’ve read it

- Matthew Parent recommended a handout by John Gerring et al (yes, Gerring from case studies! The excerpt is from Gerring and Dino Christenson’s forthcoming book). I love both Gerring and Christenson’s work so I’m always happy to promote it.

I found through Google a few handouts, but these three were the ones that stood out to me, and were also the simplest for me to refer my students for a reading.

- Summary vs. Description vs. Analysis vs. Argument . One handout I found clearly describes the differences between summary, description, analysis and argument. This one is an anthropology-focused one .

- This checklist tells the reader how to distinguish between description (telling things how they are, detailed accounts of facts and data) and analysis (explaining the implications, tying theory and empirical evidence to the description).

- This short guide from the University of Birmingham Writing Centre on critical thinking and the differences between analytical and descriptive writing really outlines when you use description, when you should be analyzing and how to differentiate between both.

Over on The Research Companion Facebook group, I got a few responses.

- Dr. Helen Kara recommended her book: Research and evaluation for busy students and practitioners. A time saving guide (having read some of her work and writing, I can vouch for it!).

- Sarah Howcutt shared with me a couple of handouts where she clearly explains what description is and how to insert analysis into your paragraphs.

I then searched my own Mendeley library for examples of good articles I had read that could show my students what analysis looks like, vis-a-vis descriptive text. Here are a few examples I tweeted.

Describing refers to providing details. Analyzing implies comparing, contrasting, weighing the evidence for additional insight, critiquing — Dr Raul Pacheco-Vega (@raulpacheco) May 8, 2017

The first one is from a World Development 2014 article by Alison Post and Veronica Herrera on public service delivery in Latin America (focusing on water and wastewater). Here, I wanted the reader to see how Herrera and Post set up a comparison between what the literature says versus what their own analysis shows.

. @veromsherrera and Alison Post offer an excellent example of the “They Say/I Say” model, showing what literature says vs their analysis pic.twitter.com/SYUMxtd543 — Dr Raul Pacheco-Vega (@raulpacheco) May 8, 2017

. @veromsherrera Note that here @veromsherrera and Post analyze the literature on privatization and offer their own analysis of what it fails to account for. — Dr Raul Pacheco-Vega (@raulpacheco) May 8, 2017

. @veromsherrera This is important when teaching our students: contrast what the literature says with your own empirical findings. Also, model They Say/I Say — Dr Raul Pacheco-Vega (@raulpacheco) May 8, 2017

. @veromsherrera If you’re wondering what I mean by the “They Say/I Say” model, it’s based on Graff & Birkenstein book https://t.co/Nu7SkRPKT4 h/t @owasow — Dr Raul Pacheco-Vega (@raulpacheco) May 8, 2017

This example comes from Kathryn Harrison’s 2002 Governance article comparing US/Canada/Sweden and dioxins control policy. This paper investigates the role of ideas, interests and institutions on policy change. In this example, I wanted to show how Harrison weighs evidence from each one of the three case studies and evaluates the differential impact that ideas, interests and institutions had on policy evolution.

In comparison of pulp and paper policies US/Canada/Sweden, @khar1958 weighs evidence & explanatory power of ideas, interests & institutions pic.twitter.com/ce2tbqxhmb — Dr Raul Pacheco-Vega (@raulpacheco) May 8, 2017

. @khar1958 Note that while @khar1958 finds compelling evidence of impact of ideas, she points out to interplay of ideas, interests AND institutions. — Dr Raul Pacheco-Vega (@raulpacheco) May 8, 2017

. @khar1958 This is important when we teach students to offer evidence. We need to tell them to offer alternative explanations, weigh evidence/results. — Dr Raul Pacheco-Vega (@raulpacheco) May 8, 2017

I then used Josh Cousins and Josh Newell’s article on political-industrial ecology in Los Angeles’ water supply infrastructure to show the reader how Cousins and Newell present descriptive text on Los Angeles and its water supply and then connect it to the literature through analysis.

In their paper on the urban industrial-political ecology of Los Angeles water supply, @JoshJCousins & Newell link description w/analysis pic.twitter.com/IPesNK1uSx — Dr Raul Pacheco-Vega (@raulpacheco) May 8, 2017

. @JoshJCousins I used pink to denote descriptive text, and orange to show where Cousins & Newell link the description above with theoretical underpinnings. — Dr Raul Pacheco-Vega (@raulpacheco) May 8, 2017

I used Megan Hatch and Elizabeth Rigby’s article on state-level governments as laboratories of democracy and their study of state-level inequality to show how you can use data (quantitative, in this case) to create an argument and dispel previously held beliefs/preconceived ideas/previous theoretical and empirical findings with their own.

Here, @meganehatch & E. Rigby show (graph above screenshot) how their results counter our traditional understanding of inequality in states pic.twitter.com/Ew3wTHcsYc — Dr Raul Pacheco-Vega (@raulpacheco) May 8, 2017

I also used a paper by Melissa Merry on tweeting and the framing of gun policy using the Narrative Policy Framework. In this example I wanted to show how Merry mobilizes her empirical findings to construct a new measure and to explain the theoretical and empirical implications of her findings.

. @melpoague offers good example of ANALYSIS – “here is how I constructed an index, and what my results imply” (on gun policy narratives) pic.twitter.com/yXUyPCijWk — Dr Raul Pacheco-Vega (@raulpacheco) May 8, 2017

From David Carter and Chris Weible’s study of smoking bans in Colorado in 1977 and 2006, I drew an example where I show how Carter and Weible set up an empirical question (a hypothesis) and then use their data to explain differences between both smoking bans.

In their paper comparing Colorado smoking bans 1977 vs 2006 @DCarterSLC and @chris_weible answer 1 of their questions w data & analysis pic.twitter.com/0SY5E1VAhs — Dr Raul Pacheco-Vega (@raulpacheco) May 8, 2017

Another way in which researchers show they’ve done analysis is in case study selection. In this paper by Rob de Leo and Donnelly, they do a study of policy transfer and the adoption of the Affordable Care Act in Massachusetts. De Leo and Donnelly clearly outline the various reasons why choosing this particular case makes sense.

In their paper on policy transfer and implementation of the Affordable Care Act, @r_deLeo and Donelly clearly outline case study selection pic.twitter.com/afeHzT8amM — Dr Raul Pacheco-Vega (@raulpacheco) May 8, 2017

I am thankful to everyone who provided me with links to books, handouts, etc. And I hope this blog post will be useful to anybody who needs to teach analysis vs. description. I certainly will be using it with my own students and research assistants!

You can share this blog post on the following social networks by clicking on their icon.

Posted in academia , writing .

Tagged with academic writing , analysis , synthesis , writing .

By Raul Pacheco-Vega – May 7, 2017

One Response

Stay in touch with the conversation, subscribe to the RSS feed for comments on this post .

Continuing the Discussion

[…] cover). 3. Do the exercises suggested in that book as you go along. 4. Once you have discerned the difference between describing and analyzing, and how to write arguments, you should be able to identify key ideas within paragraphs more easily […]

Leave a Reply Cancel Some HTML is OK

Name (required)

Email (required, but never shared)

or, reply to this post via trackback .

About Raul Pacheco-Vega, PhD

Find me online.

My Research Output

- Google Scholar Profile

- Academia.Edu

- ResearchGate

My Social Networks

- Polycentricity Network

Recent Posts

- “State-Sponsored Activism: Bureaucrats and Social Movements in Brazil” – Jessica Rich – my reading notes

- Reading Like a Writer – Francine Prose – my reading notes

- Using the Pacheco-Vega workflows and frameworks to write and/or revise a scholarly book

- On framing, the value of narrative and storytelling in scholarly research, and the importance of asking the “what is this a story of” question

- The Abstract Decomposition Matrix Technique to find a gap in the literature

Recent Comments

- Hazera on On framing, the value of narrative and storytelling in scholarly research, and the importance of asking the “what is this a story of” question

- Kipi Fidelis on A sequential framework for teaching how to write good research questions

- Razib Paul on On framing, the value of narrative and storytelling in scholarly research, and the importance of asking the “what is this a story of” question

- Jonathan Wilcox on An improved version of the Drafts Review Matrix – responding to reviewers and editors’ comments

- Catherine Franz on What’s the difference between the Everything Notebook and the Commonplace Book?

Follow me on Twitter:

Proudly powered by WordPress and Carrington .

Carrington Theme by Crowd Favorite

- Translators

- Graphic Designers

Please enter the email address you used for your account. Your sign in information will be sent to your email address after it has been verified.

Analytical vs. Descriptive Writing: Definitions and Examples

Scholars at all levels are expected to write. People who are not students or scholars often engage in writing for work, or to communicate with friends, family, and strangers through email, text messages, and social media. Academia recognizes two major types of writing—descriptive writing and analytical writing—which are both used in non-academic situations as well. As you might expect, descriptive writing focuses on clear descriptions of facts or things that have happened, while analytical writing provides additional analysis.

Descriptive writing is the most straightforward type of academic writing. It provides accurate information about "who", "what", "where", and "when". Examples of descriptive writing include:

- Summarizing an article (without offering additional insight)

- Stating the results of an experiment (without analyzing the implications)

- Describing a newsworthy event (without discussing possible long-term consequences)

High school students and undergraduates are most commonly asked to write descriptively, to show that they understand the key points of a specific topic (e.g. the major causes of World War II).

Analytical writing goes beyond summarizing information and instead provides evaluation, comparison, and possible conclusions. It addresses the questions of "why?", "so what?", and "what next?". Examples of analytical writing include:

- The discussion section of research papers

- Opinion pieces about the likely consequences of newsworthy events and the steps that should be taken in response.

High school students and undergraduates are sometimes asked to write analytically to "stretch their thinking". Possible topics might include "Could World War II have been avoided?" and "How can CRISPR-Cas9 technology improve human health?". The value of any such analysis is entirely dependent on the writer's ability to understand and clearly explain relevant information, which would be explained through descriptive writing. For graduate students and professional researchers, the quality of their work is at least partially based on the quality of their analysis.

The following table from The Study Skills Handbook by Stella Cottrell (2013, 4th edition, Palgrave Macmillan, page 198) is commonly used to summarize the differences between descriptive writing and analytical writing.

Description and analysis are also used in spoken communication such as presentations and conversations, and in visual communication such as diagrams and memes. In all of these cases, it is important to communicate clearly and effectively, and to use reliable sources of information.

Descriptive writing and analytical writing are often used in combination. In job application cover letters and essays for university admission, adding analytical text can provide context for otherwise unremarkable statements.

- Descriptive text: "I graduated from Bear University in 2020 with a B.S. in Chemistry and a cumulative GPA of 3.056."

- Analytical text: "While I struggled with some of my introductory courses, I proactively sought help to fill gaps in my understanding, and earned an "A" grade for all five of my senior year science courses. Therefore, I believe I am a strong candidate for . . ."

Combining description and analysis can also be very effective when discussing the significance of research results.

- Descriptive text: "Our study found significant (>2 ug/L) concentrations of polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) in blood samples from all 5,478 study participants."

- Analytical text: "These results are alarming because the sample population included people who range in age from 1 month old to 98 years old, who live on five different continents, who reside in extremely rural areas and in urban areas, and who have little to no direct contact with products containing PFAS. PFAS are called "forever chemicals" because they are estimated to take hundreds or thousands of years to degrade. According to the US Centers for Disease Control (CDC), PFAS can move through soils to contaminate drinking water, and bioaccumulate in animals. Further research is urgently needed to better understand the adverse effects that PFAS have on human health, to identify the source of PFAS in rural communities, and to develop a method to sequester or destroy PFAS that have already entered the environment."

In both of the examples above, the analytical text includes additional facts (e.g. "A" grade for senior science courses; 1 month old to 98 years old) that help strengthen the argument. The student's transcript and the research paper's results section would contain these same facts—along with many others—written descriptively or presented in graphs, tables, or lists. For the analytical text, the author is trying to persuade the reader, and has therefore selected relevant facts to support their argument.

In the example about PFAS, the author's argument is further strengthened by citing additional information from a reputable source (the CDC). In reports where the author is supposed to be unbiased (e.g. a journalist writing descriptively), a similar effect can be obtained by quoting reputable sources. For example, "Professor of environmental science Kim Lee explains that PFAS are. . ." In these situations, it is often appropriate to present opposing views, as long as they come from reputable sources. This strategy of quoting or citing reputable sources can also be effective for students and professionals who do not have strong credentials in the topic under discussion.

Analytical writing supports a point of view

People cannot choose their own facts, but the same facts can be used to support very different points of view. Let's consider some different points of view that can be supported by the PFAS example from above.

- Scientific point of view: "Further research is urgently needed to better understand the adverse effects that PFAS have on human health, to identify the source of PFAS in rural communities, and to develop a method to sequester or destroy PFAS that have already entered the environment."

- Policy point of view: "Legislative action is urgently needed to ban the use of all PFAS, instead of banning new PFAS one at a time. Abundant and reliable data strongly indicates that all PFAS have similar effects, even if they have small differences in chemical composition. Given such evidence, the impetus must be on the chemical industry to prove safety, rather than on the general public to prove harm."

- Legal point of view: "Chemical companies have known about the danger of PFAS for years, but hid the evidence and continued to use these chemicals. Therefore, individuals and communities who have been harmed have the right to sue for damages."

These three points of view focus on three different fields (science, policy, and law), but all have a negative view of PFAS. The next example shows how the same factual information can be used to support opposing views.

- Descriptive text: " According to Data USA , the average fast food worker in 2019 was 26.1 years old, and earned a salary of $12,294 a year."

- Point of view #1: "These data show why raising the minimum wage is unnecessary. Most fast food workers are young, with many being teenagers who are making extra money while living with their parents. The majority will eventually transition to jobs that require more skills, and that are rewarded with higher pay. If we mandate that companies pay low-skill workers more than required by the free market, then more highly skilled workers will also demand a pay raise. This will hurt businesses, contribute to inflation, and have no net benefit."

- Point of view #2: "These data show why raising the minimum wage is so important. On average, for every 16-year-old working in fast food for extra money, there is a 36-year-old trying to make ends meet. As factory jobs have moved overseas, employees without specialized skills have turned to fast food for steady employment. According to the UC Berkeley Labor Center , for families with someone working full-time (40 hours/week) in fast food, more than half are enrolled in public assistance programs. These include Medicaid, food stamps, and the Earned Income Tax Credit. Therefore, taxpayers are subsidizing companies that pay poverty wages, so that their employees can have access to basic necessities like food and healthcare."

A primary purpose of analytical writing is to show how facts (explained through descriptive writing) support a particular conclusion or a particular path forward. This often requires explaining why an alternative interpretation is less satisfactory. This is how scholarly work—and good discussions in less formal situations—contribute to our collective understanding of the world.

Related Posts

Key Changes in APA 7th Edition That You Should Know

The Best Way to Structure Your Thesis or Dissertation

- Academic Writing Advice

- All Blog Posts

- Writing Advice

- Admissions Writing Advice

- Book Writing Advice

- Short Story Advice

- Employment Writing Advice

- Business Writing Advice

- Web Content Advice

- Article Writing Advice

- Magazine Writing Advice

- Grammar Advice

- Dialect Advice

- Editing Advice

- Freelance Advice

- Legal Writing Advice

- Poetry Advice

- Graphic Design Advice

- Logo Design Advice

- Translation Advice

- Blog Reviews

- Short Story Award Winners

- Scholarship Winners

Need an academic editor before submitting your work?

Your Teams. All Sources.

© 2024 BVM Sports. Best Version Media, LLC.

NBA Draft Lottery Winners’ Recent Impact vs. Historic Legends: A Critical Analysis

The Hawks won the NBA Draft lottery, but recent No. 1 overall picks have not had the transformative impact they once did, raising concerns about the evolving landscape of top draft selections.

- In the 2021-22 and 2022-23 seasons, no player chosen first overall made it to the first or second All-NBA teams.

- Over the past 10 years, there have been 14 instances of players drafted outside the top 10 earning first-team All-NBA honors.

The decline in impact from No. 1 overall picks may also reflect a combination of teams' drafting inefficiencies and a potential decrease in talent development within various basketball systems.

- Recent NBA Drafts have seen a lack of immediate game-changing talents at the No. 1 spot, contrasting with historical trends of impactful top draft selections.

- The emergence of top-tier NBA talents outside the top 10 picks in recent years indicates a shift in the drafting landscape towards undervalued players.

The NBA hopes upcoming drafts may witness the rise of new elite talents like Edwards, Wembanyama, and Banchero, potentially ushering in a new era of impactful top picks.

As the nature of No. 1 overall picks' impact evolves, NBA teams may need to reconsider their drafting strategies and explore untapped talent pools to secure future success in a changing draft landscape.

Read more at @sportingnews

The summary of the linked article was generated with the assistance of artificial intelligence technology from OpenAI

@sportingnews • @TSNMike

The Hawks won the NBA Draft lottery, but No. 1 overall picks haven't been the game-changers they once were | Sporting News

Top leagues, think your team or athlete is better show us, submit your story, photo or video.

We use cookies to ensure that we give you the best experience on our website. If you continue to use this site we will assume that you are happy with it.

OK Privacy policy

Elections Today

Recent projections, delegate tracker, maryland, west virginia and nebraska primaries 2024: alsobrooks beats trone, gop incumbents survive, biden once slammed trump's china tariffs. now he's building on them: analysis.

Biden’s tariffs on $18B worth of Chinese goods focus on strategic industries.

Although the Biden administration won't admit it, new tariffs on China announced Tuesday represent a major shift for President Joe Biden .

Back in 2019, Biden slammed then-President Donald Trump 's move to impose tariffs on $300 billion worth of Chinese imports.

"Trump doesn't get the basics. He thinks his tariffs are being paid by China," Biden said at the time. "Any freshman econ student could tell you that the American people are paying his tariffs."

Then in 2020, while campaigning for the White House, Biden vowed to remove Trump's tariffs if elected.

Studies have shown that American consumers largely bore the brunt of those taxes.

But now, not only is Biden keeping those Trump-era tariffs in place, he actually is building on them.

It's true that Biden's new tariffs on $18 billion worth of Chinese imports are narrowly focused on a few strategic industries. At a Rose Garden event unveiling the new actions, Biden touted it as a "smart approach" to target goods such as electric vehicles, solar cells, steel, aluminum and certain medical equipment.

But he is maintaining many of the broad-based tariffs from the Trump-era that he was once highly critical of.

MORE: Biden announces new China tariffs on electric vehicles, solar, chips and more

U.S. Trade Representative Katherine Tai was repeatedly pressed on the apparent reversal during the White House daily press briefing.

Related Stories

Biden hikes tariffs on Chinese EVs, solar cells, steel, aluminum — and snipes at Trump

- May 14, 5:03 AM

Biden announces new tariffs on China

- May 14, 12:53 PM

US plans to impose major new tariffs on EVs, other Chinese green energy imports, AP sources say

- May 10, 5:59 PM

"In terms of the price that Americans paid for in the previous era, some of that -- maybe a lot of it -- was about the chaos and unpredictability that it created and the escalation that resulted," Tai said.

Tai added that in addition to looking at prices, the yearslong review of the Trump-era tariffs also investigated whether they had changed China's behavior.

"Not only have we not seen the problematic practices subsidize in some areas, we have seen them get worse. And in that light, there is actually no reason for us, no justification to relieving the tariff burdens on the trade with Beijing," she said.

Still, the National Retail Federation is calling on Biden to repeal those tariffs, arguing that "as consumers continue to battle inflation, the last thing the administration should be doing is placing additional taxes on imported products that will be paid by U.S. importers and eventually U.S. consumers."

Biden's shift partly reflects the political environment -- with both Biden and Trump fighting to appear tougher on China in what's shaping up to be a 2024 rematch -- but it also reflects growing recognition that China's trade practices are undercutting American manufacturers and workers.