Desertification: what is it and why is it one of the greatest threats of our time?

Deep trouble. Image: REUTERS/ Mohamed Nureldin Abdallah

.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo{-webkit-transition:all 0.15s ease-out;transition:all 0.15s ease-out;cursor:pointer;-webkit-text-decoration:none;text-decoration:none;outline:none;color:inherit;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:hover,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-hover]{-webkit-text-decoration:underline;text-decoration:underline;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:focus,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-focus]{box-shadow:0 0 0 3px rgba(168,203,251,0.5);} Robert McSweeney

.chakra .wef-9dduvl{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-9dduvl{font-size:1.125rem;}} Explore and monitor how .chakra .wef-15eoq1r{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-size:1.25rem;color:#F7DB5E;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-15eoq1r{font-size:1.125rem;}} Agriculture, Food and Beverage is affecting economies, industries and global issues

.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;color:#2846F8;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{font-size:1.125rem;}} Get involved with our crowdsourced digital platform to deliver impact at scale

Stay up to date:, agriculture, food and beverage.

Desertification has been described as the “ the greatest environmental challenge of our time ” and climate change is making it worse.

While the term may bring to mind the windswept sand dunes of the Sahara or the vast salt pans of the Kalahari, it’s an issue that reaches far beyond those living in and around the world’s deserts, threatening the food security and livelihoods of more than two billion people.

The combined impact of climate change, land mismanagement and unsustainable freshwater use has seen the world’s water-scarce regions increasingly degraded. This leaves their soils less able to support crops, livestock and wildlife.

This week, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) will publish its special report on climate change and land . The report, written by hundreds of scientists and researchers from across the world, dedicates one of its seven chapters solely to the issue of desertification.

Ahead of the report, Carbon Brief looks at what desertification is, the role that climate change plays and what impact it is having around the world.

Defining desertification

In 1994, the UN established the United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification (UNCCD) as the “sole legally binding international agreement linking environment and development to sustainable land management”. The Convention itself was a response to a call at the UN Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro in 1992 to hold negotiations for an international legal agreement on desertification.

The UNCCD set out a definition of desertification in a treaty adopted by parties in 1994. It states that desertification means “land degradation in arid, semi-arid and dry sub-humid areas resulting from various factors, including climatic variations and human activities”.

So, rather than desertification meaning the literal expansion of deserts, it is a catch-all term for land degradation in water-scarce parts of the world. This degradation includes the temporary or permanent decline in quality of soil, vegetation, water resources or wildlife, for example. It also includes the deterioration of the economic productivity of the land – such as the ability to farm the land for commercial or subsistence purposes.

Arid, semi-arid and dry sub-humid areas are known collectively as “drylands”. These are, unsurprisingly, areas that receive relatively little rain or snow each year. Technically, they are defined by the UNCCD as “areas other than polar and sub-polar regions, in which the ratio of annual precipitation to potential evapotranspiration falls within the range from 0.05 to 0.65”.

In simple terms, this means the amount of rainfall the area receives is between 5-65% of how much it loses through evaporation and transpiration from the land surface and vegetation, respectively. Any area that receives more than this is referred to as “humid”.

You can see this more clearly in the map below, where the world’s drylands are identified by different grades of orange and red shading. Drylands encompass around 38% of the Earth’s land area, covering much of North and southern Africa, western North America, Australia, the Middle East and Central Asia. Drylands are home to approximately 2.7 billion people (pdf) – 90% of whom live in developing countries.

Drylands are particularly susceptible to land degradation because of scarce and variable rainfall as well as poor soil fertility. But what does this degradation look like?

There are numerous ways in which the land can degrade. One of the main processes is erosion – the gradual breaking down and removal of rock and soil. This is typically through some force of nature – such as wind, rain and/or waves – but can be exacerbated by activities including ploughing, grazing or deforestation.

A loss of soil fertility is another form of degradation. This can be through a loss of nutrients, such as nitrogen, phosphorus and potassium, or a decline in the amount of organic matter in the soil. For example, soil erosion by water causes global losses of as much as 42m tonnes of nitrogen and 26m tonnes of phosphorus every year. On farmed land, this inevitably needs to be replaced through fertilisers at significant cost. Soils can also suffer from salinisation – an increase in salt content – and acidification from overuse of fertilisers.

Then there are lots of other processes that are classed as degradation, including a loss or shift in vegetation type and cover, the compaction and hardening of the soil, an increase in wildfires, and a declining water table through excessive extraction of groundwater.

Have you read?

If we want to solve climate change, water governance is our blueprint.

Mix of causes

According to a recent report from the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES), “land degradation is almost always the result of multiple interacting causes”.

The direct causes of desertification can be broadly divided between those relating to how the land is – or isn’t – managed and those relating to the climate. The former includes factors such as deforestation, overgrazing of livestock, over-cultivation of crops and inappropriate irrigation; the latter includes natural fluctuations in climate and global warming as a result of human-caused greenhouse gas emissions.

Then there are underlying causes as well, the IPBES report notes, including “economic, demographic, technological, institutional and cultural drivers”.

Looking first at the role of the climate, a significant factor is that the land surface is warming more quickly than the Earth’s surface as a whole. (This is because the land has a lower “ heat capacity ” than the water in the oceans, which means it needs less heat to raise its temperature.) So, while global average temperatures are around 1.1C warmer now than in pre-industrial times , the land surface has warmed by approximately 1.7C. The chart below compares changes in land temperatures in four different records with a global average temperature since 1970 (blue line).

Global average land temperatures from four datasets: CRUTEM4 (purple), NASA (red), NOAA (yellow) and Berkeley (grey) for 1970 to the present day, relative to a 1961-90 baseline. Also shown is global temperature from the HadCRUT4 record (blue). Chart by Carbon Brief using Highcharts .

While this sustained, human-caused warming can by itself add to heat stress faced by vegetation, it is also linked to worsening extreme weather events , explains Prof Lindsay Stringer , a professor in environment and development at the University of Leeds and a lead author on the land degradation chapter of the forthcoming IPCC land report. She tells Carbon Brief:

“Climate change affects the frequency and magnitude of extreme events like droughts and floods. In areas that are naturally dry for example, a drought can have a huge impact on vegetation cover and productivity, particularly if that land is being used by high numbers of livestock. As plants die off due to lack of water, the soil becomes bare and is more easily eroded by wind, and by water when the rains do eventually come.”

(Stringer is commenting here in her role at her home institution and not in her capacity as an IPCC author. This is the case with all the scientists quoted in this article.)

Both natural variability in climate and global warming can also affect rainfall patterns around the world, which can contribute to desertification. Rainfall has a cooling effect on the land surface, so a decline in rainfall can allow soils to dry out in the heat and become more prone to erosion. On the other hand, heavy rainfall can erode soil itself and cause waterlogging and subsidence.

For example, widespread drought – and associated desertification – in the Sahel region of Africa in the second half of the 20th century has been linked to natural fluctuations in the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans , while research also suggests a partial recovery in rains was driven by warming sea surface temperatures in the Mediterranean .

Dr Katerina Michaelides , a senior lecturer in the Drylands Research Group at the University of Bristol and contributing author on the desertification chapter of the IPCC land report, describes a shift to drier conditions as the main impact of a warming climate on desertification. She tells Carbon Brief:

“The main effect of climate change is through aridification, a progressive change of the climate towards a more arid state – whereby rainfall decreases in relation to the evaporative demand – as this directly affects water supply to vegetation and soils.”

Climate change is also a contributing factor to wildfires , causing warmer – and sometimes drier – seasons that provide ideal conditions for fires to take hold. And a warmer climate can speed up the decomposition of organic carbon in soils, leaving them depleted and less able to retain water and nutrients .

As well as physical impacts on the landscape, climate change can impact on humans “because it reduces options for adaptation and livelihoods, and can drive people to overexploit the land”, notes Stringer.

That overexploitation refers to the way that humans can mismanage land and cause it to degrade. Perhaps the most obvious way is through deforestation. Removing trees can upset the balance of nutrients in the soil and takes away the roots that helps bind the soil together, leaving it at risk of being eroded and washed or blown away.

Forests also play a significant role in the water cycle – particularly in the tropics. For example, research published in the 1970s showed that the Amazon rainforest generates around half of its own rainfall. This means that clearing the forests runs the risk of causing the local climate to dry, adding to the risk of desertification.

Food production is also a major driver of desertification. Growing demand for food can see cropland expand into forests and grasslands , and use of intensive farming methods to maximise yields. Overgrazing of livestock can strip rangelands of vegetation and nutrients.

This demand can often have wider political and socioeconomic drivers, notes Stringer:

“For example, demand for meat in Europe can drive the clearance of forest land in South America. So, while desertification is experienced in particular locations, its drivers are global and coming largely from the prevailing global political and economic system.”

Local and global impacts

Of course, none of these drivers acts in isolation. Climate change interacts with the other human drivers of degradation, such as “unsustainable land management and agricultural expansion, in causing or worsening many of these desertification processes”, says Dr Alisher Mirzabaev , a senior researcher at the University of Bonn and a coordinating lead author on the desertification chapter of the IPCC land report. He tells Carbon Brief:

“The [result is] declines in crop and livestock productivity, loss of biodiversity, increasing chances of wildfires in certain areas. Naturally, these will have negative impacts on food security and livelihoods, especially in developing countries.”

Stringer says desertification often brings with it “a reduction in vegetation cover, so more bare ground, a lack of water, and soil salinisation in irrigated areas”. This also can mean a loss of biodiversity and visible scarring of the landscape through erosion and the formation of gullies following heavy rainfall.

“Desertification has already contributed to the global loss of biodiversity”, adds Joyce Kimutai from the Kenya Meteorological Department . Kimutai, who is also a lead author on the desertification chapter of the IPCC land report, tells Carbon Brief:

“Wildlife, especially large mammals, have limited capacities for timely adaptation to the coupled effects of climate change and desertification.”

For example, a study (pdf) of the Cholistan Desert region of Pakistan found that the “flora and fauna have been thinning out gradually with the increasing severity of desertization”. And a study of Mongolia found that “all species richness and diversity indicators declined significantly” because of grazing and increasing temperatures over the last two decades.

Degradation can also open the land up to invasive species and those less suitable for grazing livestock, says Michaelides:

“In many countries, desertification means a decline in soil fertility, a reduction in vegetation cover – especially grass cover – and more invasive shrub species. Practically speaking, the consequences of this are less available land for grazing, and less productive soils. Ecosystems start to look different as more drought tolerant shrubs invade what used to be grasslands and more bare soil is exposed.”

This has “devastating consequences for food security, livelihoods and biodiversity”, she explains:

“Where food security and livelihoods are intimately tied to the land, the consequences of desertification are particularly immediate. Examples are many countries in East Africa – especially Somalia, Kenya and Ethiopia – where over half of the population are pastoralists relying on healthy grazing lands for their livelihoods. In Somalia alone, livestock contributes around 40% of the GDP [Gross Domestic Product].”

The UNCCD estimates that around 12m hectares of productive land are lost to desertification and drought each year. This is an area that could produce 20m tonnes of grain annually.

This has a considerable financial impact. In Niger, for example, the costs of degradation caused by land use change amounts to around 11% of its GDP . Similarly in Argentina, the “total loss of ecosystem services due to land-use/cover change, wetlands degradation and use of land degrading management practices on grazing lands and selected croplands” is equivalent to about 16% of its GDP .

Loss of livestock, reduced crop yields and declining food security are very visible human impacts of desertification, says Stringer:

“People cope with these kinds of challenges in various ways – by skipping meals to save food; buying what they can – which is difficult for those living in poverty with few other livelihood options – collecting wild foods, and in extreme conditions, often combined with other drivers, people move away from affected areas, abandoning the land.”

People are particularly vulnerable to the impacts of desertification where they have “insecure property rights, where there are few economic supports for farmers, where there are high levels of poverty and inequality, and where governance is weak”, Stringer adds.

Another impact of desertification is an increase in sand and dust storms. These natural phenomena – known variously as “sirocco”, “haboob”, “yellow dust”, “white storms”, and the “harmattan” – occur when strong winds blow loose sand and dirt from bare, dry soils. Research suggests that global annual dust emissions have increased by 25% between the late nineteenth century and today, with climate change and land use change the key drivers.

Dust storms in the Middle East, for example, “are becoming more frequent and intense in recent years”, a recent study found. This has been driven by “long-term reductions in rainfall promot[ing] lower soil moisture and vegetative cover”. However, Stringer adds that “further research is needed to establish the precise links between climate change, desertification and dust and sandstorms”.

Dust storms can have a huge impact on human health, contributing to respiratory disorders such as asthma and pneumonia, cardiovascular issues and skin irritations, as well as polluting open water sources. They can also play havoc with infrastructure, reducing the effectiveness of solar panels and wind turbines by covering them in dust, and causing disruption to roads, railways and airports .

Climate feedback

Adding dust and sand into the atmosphere is also one of the ways that desertification itself can affect the climate, says Kimutai. Others include “changes in vegetation cover, surface albedo (reflectivity of the Earth’s surface), and greenhouse gases fluxes”, she adds.

Dust particles in the atmosphere can scatter incoming radiation from the sun, reducing warming locally at the surface, but increasing it in the air above. They can also affect the formation and lifetimes of clouds, potentially making rainfall less likely and thus reducing moisture in an already dry area.

Soils are a very important store of carbon. The top two metres of soil in global drylands, for example, store an estimated 646bn tonnes of carbon – approximately 32% of the carbon held in all the world’s soils.

Research shows that the moisture content of the soil is the main influence on the capacity for dryland soils to “mineralise” carbon. This is the process, also known as “soil respiration”, where microbes break down the organic carbon in the soil and convert it to CO2. This process also makes nutrients in the soil available for plants to use as they grow.

Soil respiration indicates the soil’s ability to sustain plant growth . And typically, respiration declines with decreasing soil moisture to a point where microbial activity effectively stops . While this reduces the CO2 the microbes release, it also inhibits plant growth, which means the vegetation is taking up less CO2 from the atmosphere through photosynthesis. Overall, dry soils are more likely to be net emitters of CO2.

So as soils become more arid, they will tend to be less able to sequester carbon from the atmosphere, and thus will contribute to climate change. Other forms of degradation also generally release CO2 into the atmosphere, such as deforestation , overgrazing – by stripping the land of vegetation – and wildfires .

Mapping troubles

“Most dryland environments around the world are being affected by desertification to some extent,” says Michaelides.

But coming up with a robust global estimate for desertification is not straightforward, explains Kimutai:

“Current estimates of the extent and severity of desertification vary greatly due to missing and/or unreliable information. The multiplicity and complexity of the processes of desertification make its quantification even more difficult. Studies have used different methods based on different definitions.”

And identifying desertification is made harder because it tends to emerge relatively slowly, adds Michaelides:

“At the start of the process, desertification may be hard to detect, and because it’s slow it may take decades to realise that a place is changing. By the time it is detected, it may be hard to halt or reverse.”

Desertification across the Earth’s land surface was first mapped in a study published in the journal Economic Geography in 1977. It noted that: “For much of the world, there is little good information on the extent of desertification in individual countries”. The map – shown below – graded areas of desertification as “slight”, “moderate”, “severe” or “very severe” based on a combination of “published information, personal experience, and consultation with colleagues”.

In 1992, the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) published its first “ World Atlas of Desertification ” (WAD). It mapped global human-caused land degradation, drawing heavily on the UNEP-funded “ Global Assessment of Human-induced Soil Degradation ” (GLASOD). The GLASOD project was itself based on expert judgement, with more than 250 soil and environmental scientists contributing to regional assessments that fed into its global map, which it published in 1991.

The GLASOD map, shown below, details the extent and degree of land degradation across the world. It categorised the degradation into chemical (red shading), wind (yellow), physical (purple) or water (blue).

While GLASOD was also used for the second WAD , published in 1997, the map came under criticism for a lack of consistency and reproducibility. Subsequent datasets, such as the “ Global Assessment of Land Degradation and Improvement ” (GLADA), have benefitted from the addition of satellite data .

Nevertheless, by the time the third WAD – produced by the Joint Research Centre of the European Commission – came around two decades later, the authors “decided to take a different path”. As the report puts it:

“Land degradation cannot be globally mapped by a single indicator or through any arithmetic or modelled combination of variables. A single global map of land degradation cannot satisfy all views or needs.”

Instead of a single metric, the atlas considers a set of “14 variables often associated with land degradation”, such as aridity, livestock density, tree loss and decreasing land productivity.

As such, the map below – taken from the Atlas – does not show land degradation itself, but the “convergence of evidence” of where these variables coincide. The parts of the world with the most potential issues (shown by orange and red shading) – such as India, Pakistan, Zimbabwe and Mexico – are thus identified as particularly at risk from degradation.

As desertification cannot be characterised by a single metric, it is also tricky to make projections for how rates of degradation could change in the future.

In addition, there are numerous socio-economic drivers that will contribute. For example, the number of people directly affected by desertification is likely to increase purely because of population growth. The population living in drylands across the world is projected to increase by 43% to four billion by 2050.

The impact of climate change on aridity is also complicated. A warmer climate is generally more able to evaporate moisture from the land surface – potentially increasing dryness in combination with hotter temperatures.

However, climate change will also affect rainfall patterns, and a warmer atmosphere can hold more water vapour, potentially increasing both average and heavy rainfall in some areas.

There is also a conceptual question of distinguishing long-term changes in the dryness of an area with the relatively short-term nature of droughts.

In general, the global area of drylands is expected to expand as the climate warms. Projections under the RCP4.5 and RCP8.5 emissions scenarios suggest drylands will increase by 11% and 23% , respectively, compared to 1961-90. This would mean drylands could make up either 50% or 56%, respectively, of the Earth’s land surface by the end of this century, up from around 38% today.

This expansion of arid regions will occur principally “over southwest North America, the northern fringe of Africa, southern Africa, and Australia”, another study says, while “major expansions of semiarid regions will occur over the north side of the Mediterranean, southern Africa, and North and South America”.

Research also shows that climate change is already increasing both the likelihood and severity of droughts around the world . This trend is likely to continue. For example, one study , using the intermediate emissions scenario “RCP4.5”, projects “large increases (up to 50%–200% in a relative sense) in frequency for future moderate and severe drought over most of the Americas, Europe, southern Africa, and Australia”.

Another study notes that climate model simulations “suggest severe and widespread droughts in the next 30–90 years over many land areas resulting from either decreased precipitation and/or increased evaporation”.

However, it should be noted that not all drylands are expected to get more arid with climate change. The map below, for example, shows the projected change for a measure of aridity (defined as the ratio of rainfall to potential evapotranspiration , PET) by 2100 under climate model simulations for RCP8.5. The areas shaded red are those expected to become drier – because PET will increase more than rainfall – while those in green are expected to become wetter. The latter includes much of the Sahel and East Africa, as well as India and parts of northern and western China.

Climate model simulations also suggest that rainfall, when it does occur, will be more intense for almost the entire world , potentially increasing the risks of soil erosion. Projections indicate that most of the world will see a 16-24% increase in heavy precipitation intensity by 2100.

Limiting global warming is therefore one of the key ways to help put a break on desertification in future, but what other solutions exist?

The UN has designated the decade from January 2010 to December 2020 as the “United Nations decade for deserts and the fight against desertification”. The decade was to be an “opportunity to make critical changes to secure the long-term ability of drylands to provide value for humanity’s well being”.

What is very clear is that prevention is better – and much cheaper – than cure. “Once desertification has occurred it is very challenging to reverse”, says Michaelides. This is because once the “cascade of degradation processes start, they’re hard to interrupt or halt”.

Stopping desertification before it starts requires measures to “protect against soil erosion, to prevent vegetation loss, to prevent overgrazing or land mismanagement”, she explains:

“All these things require concerted efforts and policies from communities and governments to manage land and water resources at large scales. Even small scale land mismanagement can lead to degradation at larger scales, so the problem is quite complex and hard to manage.”

At the UN Conference on Sustainable Development in Rio de Janeiro in 2012, parties agreed to “strive to achieve a land-degradation neutral world in the context of sustainable development”. This concept of “ land degradation neutrality ” (LDN) was subsequently taken up by the UNCCD and also formally adopted as Target 15.3 of the Sustainable Development Goals by the UN General Assembly in 2015.

The idea of LDN, explained in detail in the video below, is a hierarchy of responses: first to avoid land degradation, second to minimise it where it does occur, and thirdly to offset any new degradation by restoring and rehabilitating land elsewhere. The outcome being that overall degradation comes into balance – where any new degradation is compensated with reversal of previous degradation.

“Sustainable land management” (SLM) is key to achieving the LDN target, says Dr Mariam Akhtar-Schuster , co-chair of the UNCCD science-policy interface and a review editor for the desertification chapter of the IPCC land report. She tells Carbon Brief:

“Sustainable land management practices, which are based on the local socio-economic and ecological condition of an area, help to avoid desertification in the first place but also to reduce ongoing degradation processes.”

SLM essentially means maximising the economic and social benefits of the land while also maintaining and enhancing its productivity and environmental functions. This can comprise a whole range of techniques, such as rotational grazing of livestock, boosting soil nutrients by leaving crop residues on the land after harvest, trapping sediment and nutrients that would otherwise be lost through erosion, and planting fast-growing trees to provide shelter from the wind.

But these measures can’t just be applied anywhere, notes Akhtar-Schuster:

“Because SLM has to be adapted to local circumstances there is no such thing as a one size fits all toolkit to avoid or reduce desertification. However, all these locally adapted tools will have the best effects if they are embedded in an integrated national land use planning system.”

Stringer agrees that there’s “no silver bullet” to preventing and reversing desertification. And, it’s not always the same people who invest in SLM who benefit from it, she explains:

“An example here would be land users upstream in a catchment reforesting an area and reducing soil erosion into water bodies. For those people living downstream this reduces flood risk as there is less sedimentation and could also deliver improved water quality.”

However, there is also a fairness issue if the land users upstream are paying for the new trees and those downstream are receiving the benefits at no cost, Stringer says:

“Solutions therefore need to identify who ‘wins’ and who ‘loses out’ and should incorporate strategies that compensate or minimise inequities.”

“Everyone forgets that last part about equity and fairness,” she adds. The other aspect that has also been overlooked historically is getting community buy-in on proposed solutions, says Stringer.

Research shows that using traditional knowledge can be particularly beneficial for tackling land degradation. Not least because communities living in drylands have done so successfully for generations, despite the tricky environmental conditions.

This idea is increasingly being taken on board, says Stringer – a response to “top-down interventions” that have proved “ineffective” because of a lack of community involvement.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Related topics:

The agenda .chakra .wef-n7bacu{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-weight:400;} weekly.

A weekly update of the most important issues driving the global agenda

.chakra .wef-1dtnjt5{display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;-webkit-flex-wrap:wrap;-ms-flex-wrap:wrap;flex-wrap:wrap;} More on Industries in Depth .chakra .wef-17xejub{-webkit-flex:1;-ms-flex:1;flex:1;justify-self:stretch;-webkit-align-self:stretch;-ms-flex-item-align:stretch;align-self:stretch;} .chakra .wef-nr1rr4{display:-webkit-inline-box;display:-webkit-inline-flex;display:-ms-inline-flexbox;display:inline-flex;white-space:normal;vertical-align:middle;text-transform:uppercase;font-size:0.75rem;border-radius:0.25rem;font-weight:700;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;line-height:1.2;-webkit-letter-spacing:1.25px;-moz-letter-spacing:1.25px;-ms-letter-spacing:1.25px;letter-spacing:1.25px;background:none;padding:0px;color:#B3B3B3;-webkit-box-decoration-break:clone;box-decoration-break:clone;-webkit-box-decoration-break:clone;}@media screen and (min-width:37.5rem){.chakra .wef-nr1rr4{font-size:0.875rem;}}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-nr1rr4{font-size:1rem;}} See all

Robot rock stars, pocket forests, and the battle for chips - Forum podcasts you should hear this month

Robin Pomeroy and Linda Lacina

April 29, 2024

Agritech: Shaping Agriculture in Emerging Economies, Today and Tomorrow

Confused about AI? Here are the podcasts you need on artificial intelligence

Robin Pomeroy

April 25, 2024

Which technologies will enable a cleaner steel industry?

Daniel Boero Vargas and Mandy Chan

Industry government collaboration on agritech can empower global agriculture

Abhay Pareek and Drishti Kumar

April 23, 2024

Nearly 15% of the seafood we produce each year is wasted. Here’s what needs to happen

Charlotte Edmond

April 11, 2024

- Data & knowledge

- Land & life

Desertification

- News & stories

Desertification poses a serious challenge to sustainable development and humanity’s ability to survive in many areas of the world. The UNCCD’s goal is a future that avoids, reduces, and reverses desertification. Our work paves the way for a land degradation neutral world, one that fosters sustainable development to achieve the goals set in the UN’s 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.

Humanity needs productive land. Yet the desertification and the mounting losses of productive land driven by human action and climate change have the potential to change the way billions of people will live, both now and later in this century. The warming global climate means desertification poses a challenge across the world, especially in existing drylands. As the global population increases, ever-larger areas are devoted to intensive agriculture. Widely, excessive irrigation erodes precious soil and depletes aquifers, especially in arid areas.

Currently, about 500 million people live within areas that have experienced desertification since the 1980s. People living in already degraded or desertified areas are increasingly negatively affected by climate change. Desertification aggravates existing economic, social, and environmental problems like poverty, poor health, lack of food security, biodiversity loss, water scarcity, forced migration, and lowered resilience to climate change or natural disasters.

Addressing desertification requires long-term integrated strategies that focus on:

- improving already degraded land

- ongoing rehabilitation and conservation

- managing sustainable land and water resources.

We work with scientists and governments to monitor land changes worldwide and drive efforts to slow land degradation. We do so by focusing on incentives that motivate and drive producers and consumers to change their behavior.

We advise and support the development, adoption, monitoring, and evaluation of policies designed to ensure all the world’s land-based ecosystems not only survive, but thrive, supporting the wellbeing of present and future generations.

Related news

UNCCD Executive Secretary visit to Mauritania: A focus on desertification and cooperation

19th Meeting of the Science-Policy Interface: Opening remarks by Ibrahim Thiaw

Land issues high on UN Environment Assembly agenda

billion people worldwide are negatively impacted by desertification

of GDP is lost due to desertification per year

Publications

Desertification is a silent, invisible crisis that is destabilizing communities on a global scale. As the effects of climate change undermine livelihoods, inter-ethnic clashes are breaking out within and across states and fragile states are turning to militarization to…

Global Land Outlook (GLO)

The second edition of the Global Land Outlook (GLO2), Land Restoration for Recovery and Resilience, sets out the rationale, enabling factors, and diverse pathways by which countries and communities can reduce and reverse land degradation.

Desertification, land degradation and drought

Related sdgs, protect, restore and promote sustainable use ....

Description

Publications.

Paragraph 33 of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development focuses on the linkage between sustainable management of the planet’s natural resources and social and economic development as well as on “strengthen cooperation on desertification, dust storms, land degradation and drought and promote resilience and disaster risk reduction” .

Sustainable Development Goal 15 of the 2030 Agenda aims to “protect, restore and promote sustainable use of terrestrial ecosystems, sustainably manage forests, combat desertification, and halt and reverse land degradation and halt biodiversity loss” .

The economic and social significance of a good land management, including soil and its contribution to economic growth and social progress is recognized in paragraph 205 of the Future We Want. In this context, Member States express their concern on the challenges posed to sustainable development by desertification, land degradation and drought, especially for Africa, LDCs and LLDCs. At the same time, Member States highlight the need to take action at national, regional and international level to reverse land degradation, catalyse financial resources, from both private and public donors and implement both the United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification (UNCCD) and its 10- Year Strategic Plan and Framework (2008-2018).

Furthermore, in paragraphs 207 and 208 of the Future We Want, Member States encourage and recognize the importance of partnerships and initiatives for the safeguarding of land resources, further development and implementation of scientifically based, sound and socially inclusive methods and indicators for monitoring and assessing the extent of desertification, land degradation and drought. The relevance of efforts underway to promote scientific research and strengthen the scientific base of activities to address desertification and drought under the UNCCD is also addressed.

Combating desertification and drought were discussed by the Commission on Sustainable Development in several sessions. In the framework of the Commission's multi-year work programme, CSD 16-17 focused, respectively in 2008 and 2009, on desertification and drought along with the interrelated issues of Land, Agriculture, Rural development and Africa.

In accordance with its multi-year programme of work, CSD-8 in 2000 reviewed integrated planning and management of land resources as its sectoral theme. In its decision 8/3 on integrated planning and management of land resources, the Commission on Sustainable Development noted the importance of addressing sustainable development through a holistic approach, such as ecosystem management, in order to meet the priority challenges of desertification and drought, sustainable mountain development, prevention and mitigation of land degradation, coastal zones, deforestation, climate change, rural and urban land use, urban growth and conservation of biological diversity.

The sectoral cluster of land, desertification, forests and biodiversity, as well as mountains (chapters 10-13 and 15 of Agenda 21) were considered by CSD-3 in 1995 and again at the five-year review in 1997.

The UN Conference on Environment and Development (UNCED) called upon the United Nations General Assembly to establish an Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee (INCD) to prepare, by June 1994, an international convention to combat desertification in those countries experiencing serious drought and/or desertification, particularly in Africa. The Convention was adopted in Paris on 17 June 1994 and opened for signature there on 14-15 October 1994. It entered into force on 26 December 1996.

Deserts are among the "fragile ecosystems" addressed by Agenda 21, and "combating desertification and drought" is the subject of Chapter 12. Desertification includes land degradation in arid, semi-arid and dry sub humid areas resulting from various factors, including climatic variations and human activities. Desertification affects as much as one-sixth of the world's population, seventy percent of all drylands, and one-quarter of the total land area of the world. It results in widespread poverty as well as in the degradation of billion hectares of rangeland and cropland.

Integrated planning and management of land resources is the subject of chapter 10 of Agenda 21, which deals with the cross-sectoral aspects of decision-making for the sustainable use and development of natural resources, including the soils, minerals, water and biota that land comprises. This broad integrative view of land resources, which are essential for life-support systems and the productive capacity of the environment, is the basis of Agenda 21's and the Commission on Sustainable Development's consideration of land issues.

Expanding human requirements and economic activities are placing ever increasing pressures on land resources, creating competition and conflicts and resulting in suboptimal use of resources. By examining all uses of land in an integrated manner, it makes it possible to minimize conflicts, to make the most efficient trade-offs and to link social and economic development with environmental protection and enhancement, thus helping to achieve the objectives of sustainable development. (Agenda 21, para 10.1) The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) is the task manager for chapter 10 of Agenda 21.

Publication - Making Peace with Nature A scientific blueprint to tackle the climate, biodiversity and pollution emergencies

Part I of the report addresses how the current expansive mode of development degrades and exceeds the Earth’s finite capacity to sustain human well-being. The world is failing to meet most of its commitments to limit environmental damage and this increasingly threatens the achievement of the Sustain...

Transforming our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development

This Agenda is a plan of action for people, planet and prosperity. It also seeks to strengthen universal peace in larger freedom, We recognize that eradicating poverty in all its forms and dimensions, including extreme poverty, is the greatest global challenge and an indispensable requirement for su...

Climate change and desertification: Anticipating, assessing & adapting to future change in drylands - Impulse Report

Climate change and desertification: Anticipating, assessing and adapting to future change in drylands The ‘Impulse report’, a preparatory document for the Third Scientific Conference of the UN Convention to Combat Desertification (UNCCD), to be held in Cancún Mexico this 9-12 March 2015 has been pub...

Transforming Land Management Globally

Combatting land degradation is a key component of the post 2015 development agenda. The linkage between land degradation and other global environmental challenges is more recognized than ever before. We must leverage the increasing attention being given to land to further promote sustainable land ma...

“Combating desertification/land degradation and drought for poverty reduction and sustainable development: the contribution of science, technology, traditional knowledge and practices” Preliminary conclusions

The effects of demographic pressure and unsustainable land management practices on land degradation and desertification are being exacerbated worldwide due to the effects of climate change, which include (but are not limited to) changing rainfall patterns, increased frequency and intensity of drough...

WHITE PAPER II: Costs and Benefits of Policies and Practices Addressing Land Degradation and Drought in the Drylands

- Drylands are complex social-ecological systems, characterized by non-linearity of causation, complex feedback loops within and between the many different social, ecological, and economic entities, and potential of regime shifts to alternative stable states as a result of thresholds. As such, dryla...

Brazil Low-carbon - Country Case Study

In order to mitigate the impacts of climate change, the world must drastically reduce global GHG emissions in the coming decades. According to the IPCC, to prevent the global mean temperature from rising over 3oC, atmospheric GHG concentrations must be stabilized at 550 ppm. By 2030, this will requi...

Sustainable land use for the 21st century

This study is part of the Sustainable Development in the 21st century (SD21) project. The project is implemented by the Division for Sustainable Development of the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs and funded by the European Commission - Directorate-General for Environment - T...

Trends in Sustainable Development 2008-2009

This report highlights key developments and recent trends in agriculture, rural development, land, desertification and drought, five of the six themes being considered by the Commission on Sustainable Development (CSD) at its 16th and 17th sessions (2008-2009). A separate Trends Report addresses de...

Sustainable Development Innovation Briefs: Issue 8

Foreign land purchases for agriculture: what impact on sustainable development? Private investors and governments have recently stepped up foreign investment in farmlandin the form of purchases or long-term lease of large tracks of arable land, notably in Africa. This brief examines the implication...

Sustainable Development Innovation Briefs: Issue 7

The contribution of sustainable agriculture and land management to sustainable development....

Expert Group Meeting on SDG 15 (Life on land) and its interlinkages with other SDGs

In preparation for the review of SDG 15— “Protect, restore and promote sustainable use of terrestrial ecosystems, sustainably manage forests, combat desertification, and halt and reverse land degradation and halt biodiversity loss”—and its role in advancing sustainable development across the 2030 Ag

Expert Group Meetings on 2022 HLPF Thematic Review

The theme of the 2022 high-level political forum on sustainable development (HLPF) is “Building back better from the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) while advancing the full implementation of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development”. The 2022 HLPF will have an

UNEP Environment Assembly

United nations forum on forests, fourteenth meeting of the conference of the parties to the convention on biological diversity (cop14), expert group meeting on sustainable development goal 15: progress and prospects.

In preparation for the 2018 HLPF, the Division for Sustainable Development Goals of the Department of Economic and Social Affairs (DSDG-DESA) organized an Expert Group Meeting (EGM) on SDG 15 and its role in advancing sustainable development through implementation of the 2030 Agenda, in partnership

IYS Closure Event

The World Soil Day 2015 will host the 'closure' event of the International Year of Soils. It will also coincide with the launch of the first 'Status of the World Soil Resources Report'.

21st Session of the Conference of the Parties and 11th Session of the Conference of the Parties serving as the meeting of the Parties to the Kyoto Protocol- UNFCCC COP 21/ CMP 11

The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, or “UNFCCC”, was adopted during the Rio de Janeiro Earth Summit in 1992. It entered into force on 21 March 1994 and has been ratified by 196 States, which constitute the “Parties” to the Convention – its stakeholders. This Framework Conven

United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification (UNCCD) - 12th Session

The United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification (UNCCD) will host its Twelfth Session of the Conference of the Parties (COP12) in Ankara, Turkey, from 12 October to 23 October 2015. The conference will take place at the Congresium Ankara-ATO International Convention and Exhibition Centre. De

Third Plenary Assembly of the Global Soil Partnership

The Food and Agriculture Organization extends an invitation to attend the Third Plenary Assembly of the Global Soil Partnership (GSP) to be held from 22 to 24 June 2015 at FAO headquarters in Rome. The opening meeting will commence at 09.00 hours on Monday 22 June. The Provisional Agenda is attach

- January 2015 SDG 15 - Desertification SDG 15 aims at protecting, restoring and promoting sustainable use of terrestrial ecosystems, sustainable manage forests, combat desertification, and halt and reverse land degradation and halt biodiversity loss. Target 15.3 in particular reads to achieve "by 2030, combat desertification, restore degraded land and soil, including land affected by desertification, drought and floods, and strive to achieve a land degradation-neutral world".

- January 2012 Future We Want (Para 205-209) The economic and social significance of a good land management, including soil and its contribution to economic growth and social progress is also recognized in paragraph 205 of the Future We Want. In this context, Member States express their concern on the challenges posed to sustainable development by desertification, land degradation and drought, especially for Africa, LDCs and LLDCs. At the same time, Member States highlight the need to take action at national, regional and international level to reverse land degradation, catalyze financial resources, from both private and public donors and implement both the United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification (UNCCD) and its 10- Year Strategic Plan and Framework (2008-2018). Furthermore, in paragraphs 207 and 208 of the Future We Want, Member States encourage and recognize the importance of partnerships and initiatives for the safeguarding of land resources, further development and implementation of scientifically based, sound and socially inclusive methods and indicators for monitoring and assessing the extent of desertification, land degradation and drought. The relevance of efforts underway to promote scientific research and strengthen the scientific base of activities to address desertification and drought under the UNCCD is also taken into account by paragraph 208.

- January 2010 UN Decade on Desertification Launched by the General Assembly with the adoption of Resolution A/RES/64/201, the UN Decade for Deserts and the Fight Against Desertification was designed to address the Parties'concern about the worsening of the situation of desertification and its negative impact on the achievement of the Millennium Development Goals. The Decade started in January 2010 and will end in December 2020 with the aim of promoting action ensuring the protection of dry-lands.

- January 2008 CSD-16 (Chap.2 C,D,E) CSD-16 focused on the thematic cluster of agriculture, rural development, land, drought, desertification and Africa.

- January 2006 Int. Year of Deserts and Desertification The International Year of Deserts and Desertification was launched to highlight the threat represented by the advancing of deserts and the loss it may cause to biodiversity. Through this International Year, the UN aimed at raising public awareness on this issue and at reversing the trend of desertification, setting the world on a safer and more sustainable path of development.

- January 2000 CSD-8 (Chap. 4) As decided at UNGASS, the economic, sectoral and cross-sectoral themes under consideration for CSD-8 were sustainable agriculture and land management, integrating planning and management of land resources and financial resources, trade and investment and economic growth.CSD-6 to CSD-9 annually gathered at the UN Headquarters for spring meetings. Discussions at each session opened with multi-stakeholder dialogues, in which major groups were invited to make opening statements on selected themes followed by a dialogue with government representatives.

- January 1996 UNCCD The only legally binding international agreement connecting environment and development to sustainable land management, UNCCD addresses the arid, semi-arid and dry sub-humid areas, known as the drylands, where some of the most vulnerable ecosystems and peoples can be found. In 2007 the 10-Year Strategy of the UNCCD (2008-2018) was adopted and on that occasion, parties to the Convention further specified their goals: "to forge a global partnership to reverse and prevent desertification/land degradation and to mitigate the effects of drought in affected areas in order to support poverty reduction and environmental sustainability". The Convention was adopted in Paris on 17 June 1994 and entered into force on 26 December 1996, 90 days after the 50th ratification was received. 194 countries and the European Union are Parties as at April 2015.

- January 1992 Agenda 21 (Chap. 10 and 12) Integrated planning and management of land resources is the subject of chapter 10 of Agenda 21, which deals with the cross-sectoral aspects of decision-making for the sustainable use and development of natural resources, including the soils, minerals and water that land comprises. Included in the sections devoted to the management of fragile ecosystems, chapter 12 has focused on combating desertification and droughts. The priority to keep in mind while combating desertification is identified by Chap 12.3 in the need to implement "preventive measures for lands that are not yet degraded, or which are only slightly degraded. However, the severely degraded areas should not be neglected. In combating desertification and drought, the participation of local communities, rural organizations, national Governments, non-governmental organizations and international and regional organizations is essential".

Sand dunes show the increasing desertification of the Tibetan Plateau, as land dries out and vegetation cover vanishes due to human activity.

- ENVIRONMENT

Desertification, explained

Humans are driving the transformation of drylands into desert on an unprecedented scale around the world, with serious consequences. But there are solutions.

As global temperatures rise and the human population expands, more of the planet is vulnerable to desertification, the permanent degradation of land that was once arable.

While interpretations of the term desertification vary, the concern centers on human-caused land degradation in areas with low or variable rainfall known as drylands: arid, semi-arid, and sub-humid lands . These drylands account for more than 40 percent of the world's terrestrial surface area.

While land degradation has occurred throughout history, the pace has accelerated, reaching 30 to 35 times the historical rate, according to the United Nations . This degradation tends to be driven by a number of factors, including urbanization , mining, farming, and ranching. In the course of these activities, trees and other vegetation are cleared away , animal hooves pound the dirt, and crops deplete nutrients in the soil. Climate change also plays a significant role, increasing the risk of drought .

All of this contributes to soil erosion and an inability for the land to retain water or regrow plants. About 2 billion people live on the drylands that are vulnerable to desertification, which could displace an estimated 50 million people by 2030.

Where is desertification happening, and why?

The risk of desertification is widespread and spans more than 100 countries , hitting some of the poorest and most vulnerable populations the hardest, since subsistence farming is common across many of the affected regions.

More than 75 percent of Earth's land area is already degraded, according to the European Commission's World Atlas of Desertification , and more than 90 percent could become degraded by 2050. The commission's Joint Research Centre found that a total area half of the size of the European Union (1.61 million square miles, or 4.18 million square kilometers) is degraded annually, with Africa and Asia being the most affected.

The drivers of land degradation vary with different locations, and causes often overlap with each other. In the regions of Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan surrounding the Aral Sea , excessive use of water for agricultural irrigation has been a primary culprit in causing the sea to shrink , leaving behind a saline desert. And in Africa's Sahel region , bordered by the Sahara Desert to the north and savannas to the south, population growth has caused an increase in wood harvesting, illegal farming, and land-clearing for housing, among other changes.

The prospect of climate change and warmer average temperatures could amplify these effects. The Mediterranean region would experience a drastic transformation with warming of 2 degrees Celsius, according to one study , with all of southern Spain becoming desert. Another recent study found that the same level of warming would result in "aridification," or drying out, of up to 30 percent of Earth's land surface.

A herder family tends pastures beside a growing desert.

When land becomes desert, its ability to support surrounding populations of people and animals declines sharply. Food often doesn't grow, water can't be collected, and habitats shift. This often produces several human health problems that range from malnutrition, respiratory disease caused by dusty air, and other diseases stemming from a lack of clean water.

Desertification solutions

In 1994, the United Nations established the Convention to Combat Desertification (UNCCD), through which 122 countries have committed to Land Degradation Neutrality targets, similar to the way countries in the climate Paris Agreement have agreed to targets for reducing carbon pollution. These efforts involve working with farmers to safeguard arable land, repairing degraded land, and managing water supplies more effectively.

The UNCCD has also promoted the Great Green Wall Initiative , an effort to restore 386,000 square miles (100 million hectares) across 20 countries in Africa by 2030. A similar effort is underway in northern China , with the government planting trees along the border of the Gobi desert to prevent it from expanding as farming, livestock grazing , and urbanization , along with climate change, removed buffering vegetation.

However, the results for these types of restoration efforts so far have been mixed. One type of mesquite tree planted in East Africa to buffer against desertification has proved to be invasive and problematic . The Great Green Wall initiative in Africa has evolved away from the idea of simply planting trees and toward the idea of " re-greening ," or supporting small farmers in managing land to maximize water harvesting (via stone barriers that decrease water runoff, for example) and nurture natural regrowth of trees and vegetation.

"The absolute number of farmers in these [at-risk rural] regions is so large that even simple and inexpensive interventions can have regional impacts," write the authors of the World Atlas of Desertification, noting that more than 80 percent of the world's farms are managed by individual households, primarily in Africa and Asia. "Smallholders are now seen as part of the solution of land degradation rather than a main problem, which was a prevailing view of the past."

For Hungry Minds

Related topics.

- AGRICULTURE

- DEFORESTATION

You May Also Like

They planted a forest at the edge of the desert. From there it got complicated.

Forests are reeling from climate change—but the future isn’t lost

Why forests are our best chance for survival in a warming world

How to become an ‘arbornaut’

Palm oil is unavoidable. Can it be sustainable?

- Paid Content

- Environment

- Photography

- Perpetual Planet

History & Culture

- History & Culture

- History Magazine

- Mind, Body, Wonder

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Your US State Privacy Rights

- Children's Online Privacy Policy

- Interest-Based Ads

- About Nielsen Measurement

- Do Not Sell or Share My Personal Information

- Nat Geo Home

- Attend a Live Event

- Book a Trip

- Inspire Your Kids

- Shop Nat Geo

- Visit the D.C. Museum

- Learn About Our Impact

- Support Our Mission

- Advertise With Us

- Customer Service

- Renew Subscription

- Manage Your Subscription

- Work at Nat Geo

- Sign Up for Our Newsletters

- Contribute to Protect the Planet

Copyright © 1996-2015 National Geographic Society Copyright © 2015-2024 National Geographic Partners, LLC. All rights reserved

- EO Explorer

- Global Maps

- Comments This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

- Climate Change

- Policy & Economics

- Biodiversity

- Conservation

Get focused newsletters especially designed to be concise and easy to digest

- ESSENTIAL BRIEFING 3 times weekly

- TOP STORY ROUNDUP Once a week

- MONTHLY OVERVIEW Once a month

- Enter your email *

Desertification: Causes, Effects, And Solutions

Soaring temperatures and improper disaster management have resulted in increased desertification rates across the globe. Coupled with droughts and a drop in agricultural productivity, the effects of desertification cannot be ignored. To curb such high rates of land degradation that many regions of the world are experiencing, effective risk management is needed. What is desertification and what are the main causes and solutions?

What Is Desertification?

Desertification has a few varying definitions, but mostly centres around semi-arid, sub-humid lands; in simple terms, it can be described as areas with low or variable rainfall. In addition, there is also the added element of human-induced land degradation owing to an expanding population and rampant deforestation.

Land degradation is a systematic global issue. The scale of the problem has been questioned for decades, with estimates of degraded areas ranging between 15 to 60 million kilometres. Currently, an estimated 2 billion people live on drylands vulnerable to this phenomenon and scientists predict that the effects of desertification could lead to the displacement of around 50 million people by 2030 as a result of the soaring temperatures, large-scale deforestation, and ecosystem damage in many parts of the world. Alone in Asia, more than 2 billion people will be living in dryland conditions, while Africa sees at least 1 billion in the same (Figure 1) .

What Are the Causes of Desertification?

Land degradation has been ongoing for several decades. Droughts – increasingly frequent extreme weather events caused by global warming – also amplify this situation and can lead to the depletion of nutrients from the soil and the inability of land to regrow plants, resulting in drylands that currently cover about 40% of the globe, from the Mediterranean regions and the south-western parts of the US to Asia and the Middle East. Droughts, coupled with land degradation, give rise to desertification.

But this phenomenon is also caused by activities such as urbanisation, ranching, mining, and clearing of land and emission generation. By further contributing to a rise in temperatures and a reduction in precipitation, human interventions create a vicious cycle that only exacerbates the issue.

The degradation of land leads to a reduction in soil productivity, which can lead to a variety of complexities such as environmental hazards, food insecurity as well as loss of biodiversity and ecosystem services.

Where Does Desertification Occur the Most?

More than 60% of Central Asia is vulnerable to desertification processes. Soaring temperatures in parts of China, Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan, and many other countries have been a cause of concern. Scientists have concluded that, since the 1980s, much of the Central Asian region was classified as having a desert climate . However, the issue has now spread toward northern Uzbekistan and Kyrgyzstan, southern Kazakhstan, and around the areas of the Junggar Basin in north-western China. Mountains across the continental region have become hotter and wetter, resulting in the retreat of glaciers. An example of this is the Tian Shan region in north-western China . Here, an increase in temperature and precipitation in the form of rain instead of snow has contributed to the melting of ice at mountain tops . Thereby, glaciers in Central Asia are unable to replenish ice and as a consequence, less meltwater will flow to nearby regions, causing water shortages that affect people as well as the agricultural sector.

You Might Also Like: Glaciers in China Melting at ‘Shocking’ Pace, Scientists Say

Desertification is a huge issue also in Africa. For example, poor harvesting and a surge in barren lands continue to plague the inhabitants of Engaruka, Tanzania . In Mauritania, a drop in rainfall has worsened agricultural production and has left many farmers struggling to grow enough food to eat or sell.

What Are the Main Effects of Desertification?

Desertification is attributed to soaring temperatures and/or drop in precipitation; this is likely to result in the modification and replacement of plant communities by species that are adapted to hotter and drier conditions. The most common change induced by desertification is the conversion of native vegetation by woody plants and invasive shrub species (for example Bufflegrass and Onion-weed in southwest America, and the Tamarisk plant in the Sahara).

In this regard, Jeffrey Dukes, an ecologist from Carnegie Institution for Science’s Department of Global Ecology at Stanford said : “[Desertification] is going to have consequences for things like the grazing animals that are dependent on the steppe or the grasslands”. In some regions, he adds, extended periods of drought will reduce the land’s productivity until it becomes ‘dead’ soil.

Desertification can also cause loss of biodiversity and loss of aquifers. In Africa, with nearly 45% of the landmass experiencing desertification, many people face even greater risks. In Mauritania, the dire situation has caused food insecurity, housing problems and population health declines . Villagers are trying to migrate as their houses become buried under the sand in addition to a lack of water sources and income.

Desertification has also led to an increase in the frequency of dust storms. Particulate matter, pathogens, and allergens are detrimental to human health. The health effects caused by dust storms are greatest in the areas in the immediate vicinity of their origin and regions like the Sahara Desert, Central, and eastern Asia, the Middle East, and Australia are largely affected. In places such as the Sahara region, the Middle East, and South as well as East Asia, dust storms have been attributed to causing approximately 15–50% of all cardiopulmonary deaths .

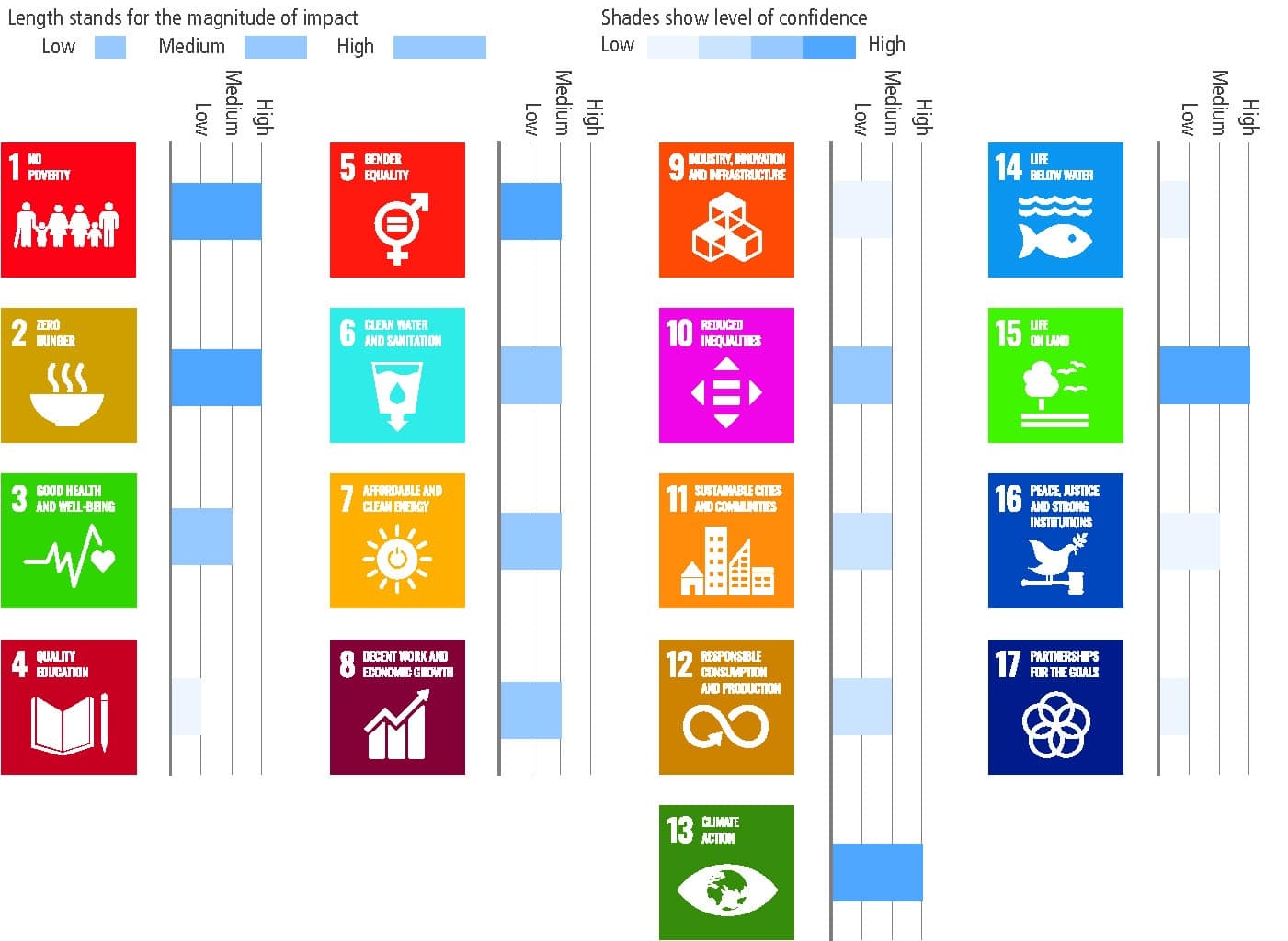

The impacts of desertification in conjunction with climate change on socio-economic systems were also exemplified in an IPCC Report on climate change and land degradation. The report suggests that the interplay between desertification and climate change greatly affects the achievement of the targets of SDGs 13 (climate action) and 15 (life on land) , thereby highlighting the need for efficient policy actions on land degradation neutrality and climate change mitigation (Figure 2) .

How Can We Solve Desertification?

A new global approach of proactive action and risk management efforts is warranted in today’s changing landscape and climate. Droughts seem to be concurrent with desertification in many parts of the Earth.

In Niger, local bodies have rehabilitated land to restore soil fertility, which has positively affected the country whose economy is largely dependent on agriculture. Here, the smallholder farmers have taken the initiative into their own hands by developing the principle of farmer-managed natural regeneration (FMNR) . This technique involves the regeneration and multiplication of valuable trees whose roots already lay underneath their land, encouraging significant tree growth. Felled tree stumps, sprouting root systems, and seeds are regrown; this has boosted soil productivity, improved agricultural income and the lands are greener than before.

Village communities in Kenya and Tanzanian are fighting droughts and desertification by digging semi-circular trenches that store water when it rains, thereby retaining moisture for plants and trees.

Some World Bank-funded projects have helped carry out ecological restoration and fixing of sand dunes in north-western China. One of the major problems of desertification is the migration or shifting of sands threatening infrastructure, villages, and irrigated farmland. Stabilisation of dunes (synonymously dune-fixing) is based on the straw-checkerboard technique. This technique involves planting straws of wheat, rice, reeds, and other plants in a checkerboard shape where half is buried and the other half is exposed. Desertification control efforts have also benefited several communities living in these areas by creating jobs and increasing incomes through the growing of sand-fixing shrub species and greenhouses .

Several other countries have already taken charge of curbing land degradation through tree-planting efforts. A nationwide ongoing effort is the “Great Green Wall of China” which has aimed to plant 88 million acres of forests in a 3000-mile network with a goal to tackle deforestation. A similar anti-desertification tree planting ambition, “Great Green Wall” of Africa has also been moving steadily since its inception in 2007. The plan to restore the degraded lands of the Sahel Region has had its fair share of progress and setbacks, but last year’s major boost announced at the One Planet Summit has planned to accelerate its completion in order to support the local farmers and support the agriculture business.

Every year, the United Nations observes the World Day to Combat Desertification and Drought, an occasion to promote public awareness of the presence of desertification and drought. This day is considered a unique moment to remind people of the ways in which land degradation can be solved through efficient problem-solving techniques and the cooperation between local, governmental, and environmental bodies.

You might also like: The Great Green Wall Receives an Economic Boost, But Is It Enough to Save It?

In May 2022, the 15th Conference of Parties (COP15) of the United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification (UNCCD) brought together ministers, high-level officials, the private sector, NGOs, and stakeholders to adopt resolutions that aim to drive progress in the protection and restoration of land . Among the resolutions adopted to curb desertification were the development of land restoration projects as well as increasing efforts to involve women in land management and collect gender-disaggregated data on the impacts of desertification and droughts. Promoting land-based jobs for youth and land-based youth entrepreneurship to strengthen youth participation and robust data monitoring of land restoration processes was also highlighted. Another key moment from this event was the launch of the Abidjan Legacy Programme; a US$2.5 billion project to strengthen supply chains while tackling the issues of deforestation and climate change.

The takeaways from this are straightforward: A call to action and risk management efforts should be at the forefront of every planned proposal to curb environmental degradation. Be it land, soil, or water, efficient cooperation, and community efforts will certainly go a long way in mitigating the consequences of climate change and environmental degradation.

This story is funded by readers like you

Our non-profit newsroom provides climate coverage free of charge and advertising. Your one-off or monthly donations play a crucial role in supporting our operations, expanding our reach, and maintaining our editorial independence.

About EO | Mission Statement | Impact & Reach | Write for us

About the Author

Keegan Carvalho

10 of the World’s Most Endangered Animals in 2024

10 of the Most Endangered Species in India in 2024

International Day of Forests: 10 Deforestation Facts You Should Know About

Hand-picked stories weekly or monthly. We promise, no spam!

- Phone This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

Boost this article By donating us $100, $50 or subscribe to Boosting $10/month – we can get this article and others in front of tens of thousands of specially targeted readers. This targeted Boosting – helps us to reach wider audiences – aiming to convince the unconvinced, to inform the uninformed, to enlighten the dogmatic.

Desertification 101: Definition, Types, Causes and Effects

Deserts, which are found on every continent, stretch across more than ⅕ of the globe’s total land area. While many think of deserts as barren wastelands devoid of life, deserts are home to some of the most specialized organisms on the planet. Around 1 billion humans also live in deserts. Plants, animals and humans have adapted to these harsh environments, but that doesn’t mean they can survive anything. As human activities like agriculture and mining cause land degradation, deserts are getting dryer while lusher, greener areas are transforming into deserts through a process called desertification. In this article, we’ll define what desertification is, its different types, its causes and its effects.

Desertification is a type of land degradation where once-productive and thriving land transforms into dry, desert landscapes. Features include a loss of plant life, soil erosion, degraded soil quality, water scarcity and so on. The effects on plants, animals and humans can be devastating.

How is desertification defined?

Deserts are extremely dry areas of land that, according to data from National Geographic, get no more than 10 inches of rain every year. Because deserts are so dry, living things like plants and animals must adapt to the area’s harsh conditions. During long stretches without rain, many plant seeds can lie dormant until a light sprinkle of rain triggers fast growth. Animals, which can include camels, foxes, snakes, lizards, rabbits and rats, tend to be nocturnal, which helps them avoid the hot sun. Humans can adapt, as well. In fact, around 6% of the human population lives in deserts. Life in the desert can be very difficult as food, water and shelter are hard to come by. Heat, desert dust and dehydration can also harm human health.

Desertification may sound like it refers to the expansion of existing deserts, but it also means land degradation that causes harm to soil, water, plants, wildlife and so on. Desertification has happened throughout time, but in 1994, the United Nations recognized it as a serious issue . They established the United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification , which is the only legally binding international treaty that connects environment and development to sustainable land management. The treaty defines desertification as “land degradation in arid, semi-arid and dry sub-humid areas resulting from various factors, including climatic variations and human activities.” The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), which is the UN body focused on climate change research, uses the same definition. Their 2019 special report on climate and land found with high confidence that desertification has increased in some drylands, while climate change will increase the risks from desertification.

Check out this online course on understanding and protecting the environment.

What are the types of desertification?

There are two main types of desertification: desertification as a natural process and desertification as a result of human activity. Because humans have such a significant impact on the climate, the types of desertification often v. Let’s explore both:

Natural desertification

According to Britannica, most deserts form on the eastern sides of big subtropical high-pressure cells. These are wheels of wind that move clockwise in the Northern Hemisphere and counterclockwise in the South. When moist air rises near the Equator and cools down, it turns into clouds and rain. As this air moves toward the pole, it releases its rain, but when it starts wheeling back to the Equator, the air starts descending. The air becomes warmer and more compressed, which does not allow for cloud and rain formation. Without much rain, the areas below become deserts. The world’s oldest desert is likely the Sahara Desert, whose origins remain a mystery. At its youngest, this North African desert could be thousands of years old, but many believe it’s around 5 million years old .

Human-driven desertification

Humans are responsible for the second type of desertification. Without activities like poor land management, overconsumption, agricultural land expansion and so on, this type of desertification would not be as severe. According to Britannica, desertification affects four main areas : irrigated croplands, rain-fed croplands, grazing lands and dry woodlands. We’ll discuss specific causes and effects of human-driven desertification in the next section of this article.

Desertification is just one environmental issue we need to address. Here’s our article on 20 other issues .

What causes desertification?

Desertification has many causes that play off one another. As an example, experts talk about climate change and desertification as a hand-in-hand relationship. Climate change makes desertification worse, while desertification also exacerbates the effects of climate change. That means most of the factors causing desertification are driving – and reinforcing – climate change. Here are five specific causes:

Overgrazing

When plants are exposed to grazing for too long or without rest periods, the land starts to degrade. This became clear in Mongolia in 2013. Known for its large grasslands, Mongolia has depended on animals like sheep and goats. Overgrazing has led to serious issues. In a study published by Global Change Biology, researchers discovered that overgrazing by sheep and goats degraded about 70% of the grasslands in the Mongolian Steppe. That meant overgrazing was responsible for 80% of the vegetation loss, while the remaining 20% was lost because of a decrease in rain. Desertification is making the Gobi Desert, a desert larger than France and Germany combined, grow.