How to Write a Social Science or Humanities Thesis/Dissertation

Writing a thesis/dissertation is a huge task, and it is common to feel overwhelmed at the start. A thesis and a dissertation are both long pieces of focused research written as the sum of your graduate or postgraduate course.

The difference between a thesis and a dissertation can depend on which part of the world you are in. In Europe, a dissertation is written as part of a Master’s degree, while a thesis is written by doctoral students. In the US, a thesis is generally the major research paper written by Master’s students to complete their programs, while a dissertation is written at the doctoral level.

The purpose of both types of research is generally the same: to demonstrate that you, the student, is capable of performing a degree of original, structured, long-term research. Writing a thesis/dissertation gives you experience in project planning and management, and allows you the opportunity to develop your expertise in a particular subject of interest. In that sense, a thesis/dissertation is a luxury, as you are allowed time and resources to pursue your own personal academic interest.

Writing a thesis/dissertation is a larger project than the shorter papers you likely wrote in your coursework. Therefore, the structure of a thesis/dissertation can differ from what you are used to. It may also differ based on what field you are in and what kind of research you do. In this article, we’ll look at how to structure a humanities or social science thesis/dissertation and offer some tips for writing such a big paper. Once you have a solid understanding of how your thesis/dissertation should be structured, you will be ready to begin writing.

How are humanities and social science thesis/dissertations structured?

The structure of a thesis/dissertation will vary depending on the topic, your academic discipline, methodology, and the place you are studying in. Generally, social science and humanities theses/dissertations are structured differently from those in natural sciences, as there are differences in methodologies and sources. However, some social science theses/dissertations can use the same format as natural science dissertations, especially if it heavily uses quantitative research methods. Such theses/dissertations generally follow the “IMRAD” model :

- Introduction

Social science theses/dissertations often range from 80-120 pages in length.

Humanities thesis/dissertations, on the other hand, are often structured more like long essays. This is because these theses/dissertations rely more heavily on discussions of previous literature and/or case studies. They build up an argument around a central thesis citing literature and case studies as examples. Humanities theses/dissertations tend to range from between 100-300 pages in length.

The parts of a dissertation: Starting out

Never assume what your reader knows! Explain every step of your process clearly and concisely as you write, and structure your thesis/dissertation with this goal in mind.

As you prepare your topic and structure your social science or humanities thesis/dissertation, always keep your audience in mind. Who are you writing for? Even if your topic is other experts in the field, you should aim to write in sufficient detail that someone unfamiliar with your topic could follow along. Never assume what your reader knows! Explain every step of your process clearly and concisely as you write, and structure your thesis/dissertation with this goal in mind.

While the structure of social science and humanities theses/dissertations differ somewhat, they both have some basic elements in common. Both types will typically begin with the following elements:

What is the title of your paper?

A good title is catchy and concisely indicates what your paper is about. This page also likely has your name, department and advisor information, and ID number. However, the specific information listed varies by institution.

Acknowledgments page

Many people probably helped you write your thesis/dissertation. If you want to say thank you, this is the place where it can be included.

Your abstract is a one-page summary (300 words or less) of your entire paper. Beginning with your thesis/dissertation question and a brief background information, it explains your research and findings. This is what most people will read before they decide whether to read your paper or not, so you should make it compelling and to the point.

Table of contents

This section lists the chapter and subchapter titles along with their page numbers. It should be written to help your reader easily navigate through your thesis/dissertation.

While these elements are found at the beginning of your humanities or social science thesis/dissertation, most people write them last. Otherwise, they’ll undergo a lot of needless revisions, particularly the table of contents, as you revise, edit, and proofread your thesis/dissertation.

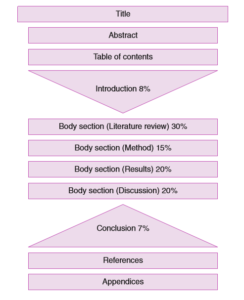

The parts of a humanities thesis/dissertation

As we mentioned above, humanities and some social science theses/dissertations follow an essay-like structure . A typical humanities thesis/dissertation structure includes the following chapters:

- References (Bibliography)

The number of themes above was merely chosen as an example.

In a humanities thesis/dissertation, the introduction and background are often not separate chapters. The introduction and background of a humanities thesis/dissertation introduces the overall topic and provides the reader with a guide for how you will approach the issue. You can then explain why the topic is of interest, highlight the main debates in the field, and provide background information. Then you explain what you are investigating and why. You should also specifically indicate your hypothesis before moving on to the first thematic chapter.

Thematic chapters (and you can have as many of them as your thesis/dissertation guidelines allow) are generally structured as follows:

- Introduction: Briefly introduce the theme of the chapter and inform the reader what you are going to talk about.

- Argument : State the argument the chapter presents

- Material : Discuss the material you will be using

- Analysis : Provide an analysis of the materials used

- Conclusion : How does this relate to your main argument and connect to the next theme chapter?

Finally, the conclusion of your paper will bring everything together and summarize your argument clearly. This is followed by the references or bibliography section, which lists all of the sources you cited in your thesis/dissertation.

The parts of a social science thesis/dissertation

In contrast to the essay structure of a humanities thesis/dissertation, a typical social science thesis/dissertation structure includes the following chapters:

- Literature Review

- Methodology

Unlike the humanities thesis/dissertation, the introduction and literature review sections are clearly separated in a social science thesis/dissertation. The introduction tells your reader what you will talk about and presents the significance of your topic within the broader context. By the end of your introduction, it should be clear to your reader what you are doing, how you are doing it, and why.

The literature review analyzes the existing research and centres your own work within it. It should provide the reader with a clear understanding of what other people have said about the topic you are investigating. You should make it clear whether the topic you will research is contentious or not, and how much research has been done. Finally, you should explain how this thesis/dissertation will fit within the existing research and what it contributes to the literature overall.

In the methodology section of a social science thesis/dissertation, you should clearly explain how you have performed your research. Did you use qualitative or quantitative methods? How was your process structured? Why did you do it this way? What are the limitations (weaknesses) of your methodological approach?

Once you have explained your methods, it is time to provide your results . What did your research find? This is followed by the discussion , which explores the significance of your results and whether or not they were as you expected. If your research yielded the expected results, why did that happen? If not, why not? Finally, wrap up with a conclusion that reiterates what you did and why it matters, and point to future matters for research. The bibliography section lists all of the sources you cited, and the appendices list any extra information or resources such as raw data, survey questions, etc. that your reader may want to know.

In social science theses/dissertations that rely more heavily on qualitative rather than quantitative methods, the above structure can still be followed. However, sometimes the results and discussion chapters will be intertwined or combined. Certain types of social science theses/dissertations, such as public policy, history, or anthropology, may follow the humanities thesis/dissertation structure as we mentioned above.

Critical steps for writing and structuring a humanities/social science thesis/dissertation

If you are still struggling to get started, here is a checklist of steps for writing and structuring your humanities or social science thesis/dissertation.

- Choose your thesis/dissertation topic

- What is the word count/page length requirement?

- What chapters must be included?

- What chapters are optional?

- Conduct preliminary research

- Decide on your own research methodology

- Outline your proposed methods and expected results

- Use your proposed methodology to choose what chapters to include in your thesis/dissertation

- Create a preliminary table of contents to outline the structure of your thesis/dissertation

By following these steps, you should be able to organize the structure of your humanities or social science thesis/dissertation before you begin writing.

Final tips for writing and structuring a thesis/dissertation

Although writing a thesis/dissertation is a difficult project, it is also very rewarding. You will get the most out of the experience if you properly prepare yourself by carefully learning about each step. Before you decide how to structure your thesis/dissertation, you will need to decide on a thesis topic and come up with a hypothesis. You should do as much preliminary reading and notetaking as you have time for.

Since most people writing a thesis/dissertation are doing it for the first time, you should also take some time to learn about the many tools that exist to help students write better and organize their citations. Citation generators and reference managers like EndNote help you keep track of your sources and AI grammar and writing checkers are helpful as you write. You should also keep in mind that you will need to edit and proofread your thesis/dissertation once you have the bulk of the writing complete. Many thesis editing and proofreading services are available to help you with this as well.

Editor’s pick

Get free updates.

Subscribe to our newsletter for regular insights from the research and publishing industry!

What are the parts of a social science thesis/dissertation? +

A social science thesis/dissertation is usually structured as follows:

How long is a typical social science thesis/dissertation? +

What are the parts of a humanities thesis/dissertation +.

Humanities theses/dissertations are usually structured like this:

- Thematic Chapters

What is the typical structure of a thematic chapter in a humanities thesis/dissertation? +

A thematic chapter in a humanities thesis/dissertation is structured like this:

How long is a typical humanities thesis/dissertation? +

A typical humanities thesis/dissertation tends to range from 100 to 300 pages in length.

Library Guides

Dissertations 2: structure: thematic.

In the humanities, a thematic dissertation is often structured like a long essay. It can contain:

Title page

Abstract

Table of contents

Introduction

Literature review (which can be included in the introduction rather than as a separate chapter. Check with your supervisor if you are unsure).

Theme 1

Theme 2

Theme 3

Conclusion

Bibliography

Appendices

Abstracts are used by other researchers to establish the relevance of the study to their own work. Therefore, they should contain the what, why, who, where and how of your project.

They are typically between 250 – 300 words long, offer a summary of the main findings and present the conclusions, so you should attempt to write an abstract (if requested), after you have finished writing the dissertation.

A typical abstract summarises:

What the study aimed to achieve

The methodology used

Why the research was conducted

Why the research is important

Who/what was researched

Table of Contents

The table of contents should list all the items included in your dissertation.

It is a good idea to use the electronic table of contents feature in Word to automatically link it to your chapter headings and page numbers. Attempting to manually create a table of contents means that you will have to adjust your page numbers every time you edit your work before submission, which may waste valuable time!

This useful video will walk you through the formatting of longer documents using the electronic table of contents feature.

Introduction

The introduction explains the how, what, where, when, why and who of the research. It introduces the reader to your dissertation and should act as a clear guide as to what it will cover.

The introduction may include the following content:

Introduce the topic of the dissertation

- State why the topic is of interest

- Give background information on the subject.

- Refer to the main debates in the field

Identify the scope of your research

- Highlight what hasn't already been said by the literature

- Demonstrate what you seek to investigate, and why

- Present the aim of the dissertation.

- Mention your research question or hypothesis

Indicate your approach

- Introduce your main argument (especially if you have a research question, rather than hypothesis).

- Mention your methods/research design.

- Outline the dissertation structure (introduce the main points that you will discuss in the order they will be presented).

Normally, the introduction is roughly 10% of a dissertation word count.

Literature Review

The term “literature” in “literature review” comprises scholarly articles, books, and other sources (e.g. reports) relevant to a particular issue, area of research or theory. In a dissertation, the literature review illustrates what the literature already says on your research subject, providing summary and synthesis of such literature.

It is generally structured by topic, starting from general background and concepts, and then addressing what can be found - and cannot be found - on the specific focus of your dissertation. Indeed, the literature review should identify gaps in the literature, that your research aims to fill. This requires you to engage critically with the literature, not merely reproduce the critical understanding of others.

In sum, literature reviews should demonstrate how your research question can be located in a wider field of inquiry. Therefore, a literature review needs to address the connections between your work and the work of others by highlighting links between them. In doing so, you will demonstrate the foundations of your project and show how you are taking the line of inquiry forwards.

By the end of your literature review, your reader should be able to see:

The gap in knowledge and understanding which you say exists in the field.

How your research question will work within that gap.

The work other researchers have carried out and the issues debated in the field.

That you have a good understanding of the field and that you are critically engaged with the debates (Burnett, 2009).

For more detailed guidance on how to write literature reviews, check out the Literature Review Guide.

Theme Chapters

In a thematic structure, the core chapters present analysis and discussion of different themes relevant to answer the research question and support the overall argument of the dissertation. The chapters will include analysis of texts/ research material. They can explore and connect academic theories/research to develop an argument. Stella Cottrell offers some good guidance on how to structure your theme chapters. Each chapter should have the following elements (Cottrell, 2014, p183):

Theme: What is the theme of this chapter? Sequence your themes logically (e.g. from general to specific).

Argument: What argument does this chapter present?

Material: What material you will be using for this chapter?

Clustering: What are the main points you want to make? Deal with one point at a time, and don't jum around? Dedicate your points to sub-headings and paragraphs.

Sequence: In what order are you going to present the points you want to make in this chapter? Draw an outline of the chapter before starting writing it.

Introduction and Conclusion: Each chapter should have a short introduction and conclusion.

The conclusion is the final chapter of your dissertation. It should flow logically from the previously presented text; therefore, you should avoid introducing new ideas, new data, or a new direction.

Ideally, the conclusion should leave the reader with a clear understanding of the discovery or argument you have advanced.

This can be done by:

Summarising and synthesising your main findings and how they relate to your research question or hypotheses

Demonstrating the relevance and importance of your work in the wider context of your field. For example, what recommendations would you make for future research? What do we know now that we didn’t know before?

Link your conclusion to your introduction as both frame your dissertation.

A conclusion is roughly five to ten percent of the word count of the dissertation.

Avoid excessive detail. Decide what your reader needs to know.

Don’t introduce any new information such as theories, data or ideas.

Sum up the main points of your research.

Bibliography

While writing your dissertation, you would have referred to the works and research of many different authors and editors in your field of study. These works should be acknowledged in the bibliography where you will list writers alphabetically by surname.

For example:

Poloian, L.R. (2013). Retailing principles: global, multichannel, and managerial viewpoints. New York: Fairchild. Biggs, J. and Tang, C. (2011). Teaching for quality learning at university . Maidenhead: Open University Press. Ramsay, P., Maier, P. and Price, G. (2010). Study skills for business and management students . Harlow: Longman.

Unless otherwise specified by your module leader, the University uses the Harvard (author-date) style of citing and referencing. For more guidance and support on how to reference effectively check out the Referencing Guide . You can also book an appointment with an Academic Engagement Librarian for extra help with referencing.

While the main results of your study should be placed in the body of your dissertation, any extra information can be placed in the appendices chapter. This supplementary information, for instance, can consist of graphs, charts, or tables that demonstrate less significant results or interview transcripts that would disrupt the flow of the main text if they were included within it.

You can create one long appendix section or divide it into smaller sections to make it easier to navigate. For example, you might want to have an appendix for images, an appendix for transcripts, and an appendix for graphs. Each appendix (each graph or chart, etc.) should have its own number and title. Further, the sources for all appendices should be acknowledged through referencing and listed in the bibliography.

Don’t forget to mention each appendix at least once during your dissertation! This can be done using brackets in the following way: (see appendix 1).

- << Previous: Standard

- Last Updated: Nov 23, 2021 3:47 PM

- URL: https://libguides.westminster.ac.uk/c.php?g=692395

CONNECT WITH US

- How it works

How to Structure a Dissertation – A Step by Step Guide

Published by Owen Ingram at August 11th, 2021 , Revised On September 20, 2023

A dissertation – sometimes called a thesis – is a long piece of information backed up by extensive research. This one, huge piece of research is what matters the most when students – undergraduates and postgraduates – are in their final year of study.

On the other hand, some institutions, especially in the case of undergraduate students, may or may not require students to write a dissertation. Courses are offered instead. This generally depends on the requirements of that particular institution.

If you are unsure about how to structure your dissertation or thesis, this article will offer you some guidelines to work out what the most important segments of a dissertation paper are and how you should organise them. Why is structure so important in research, anyway?

One way to answer that, as Abbie Hoffman aptly put it, is because: “Structure is more important than content in the transmission of information.”

Also Read: How to write a dissertation – step by step guide .

How to Structure a Dissertation or Thesis

It should be noted that the exact structure of your dissertation will depend on several factors, such as:

- Your research approach (qualitative/quantitative)

- The nature of your research design (exploratory/descriptive etc.)

- The requirements set for forth by your academic institution.

- The discipline or field your study belongs to. For instance, if you are a humanities student, you will need to develop your dissertation on the same pattern as any long essay .

This will include developing an overall argument to support the thesis statement and organizing chapters around theories or questions. The dissertation will be structured such that it starts with an introduction , develops on the main idea in its main body paragraphs and is then summarised in conclusion .

However, if you are basing your dissertation on primary or empirical research, you will be required to include each of the below components. In most cases of dissertation writing, each of these elements will have to be written as a separate chapter.

But depending on the word count you are provided with and academic subject, you may choose to combine some of these elements.

For example, sciences and engineering students often present results and discussions together in one chapter rather than two different chapters.

If you have any doubts about structuring your dissertation or thesis, it would be a good idea to consult with your academic supervisor and check your department’s requirements.

Parts of a Dissertation or Thesis

Your dissertation will start with a t itle page that will contain details of the author/researcher, research topic, degree program (the paper is to be submitted for), and research supervisor. In other words, a title page is the opening page containing all the names and title related to your research.

The name of your university, logo, student ID and submission date can also be presented on the title page. Many academic programs have stringent rules for formatting the dissertation title page.

Acknowledgements

The acknowledgments section allows you to thank those who helped you with your dissertation project. You might want to mention the names of your academic supervisor, family members, friends, God, and participants of your study whose contribution and support enabled you to complete your work.

However, the acknowledgments section is usually optional.

Tip: Many students wrongly assume that they need to thank everyone…even those who had little to no contributions towards the dissertation. This is not the case. You only need to thank those who were directly involved in the research process, such as your participants/volunteers, supervisor(s) etc.

Perhaps the smallest yet important part of a thesis, an abstract contains 5 parts:

- A brief introduction of your research topic.

- The significance of your research.

- A line or two about the methodology that was used.

- The results and what they mean (briefly); their interpretation(s).

- And lastly, a conclusive comment regarding the results’ interpretation(s) as conclusion .

Stuck on a difficult dissertation? We can help!

Our Essay Writing Service Features:

- Expert UK Writers

- Plagiarism-free

- Timely Delivery

- Thorough Research

- Rigorous Quality Control

“ Our expert dissertation writers can help you with all stages of the dissertation writing process including topic research and selection, dissertation plan, dissertation proposal , methodology , statistical analysis , primary and secondary research, findings and analysis and complete dissertation writing. “

Tip: Make sure to highlight key points to help readers figure out the scope and findings of your research study without having to read the entire dissertation. The abstract is your first chance to impress your readers. So, make sure to get it right. Here are detailed guidelines on how to write abstract for dissertation .

Table of Contents

Table of contents is the section of a dissertation that guides each section of the dissertation paper’s contents. Depending on the level of detail in a table of contents, the most useful headings are listed to provide the reader the page number on which said information may be found at.

Table of contents can be inserted automatically as well as manually using the Microsoft Word Table of Contents feature.

List of Figures and Tables

If your dissertation paper uses several illustrations, tables and figures, you might want to present them in a numbered list in a separate section . Again, this list of tables and figures can be auto-created and auto inserted using the Microsoft Word built-in feature.

List of Abbreviations

Dissertations that include several abbreviations can also have an independent and separate alphabetised list of abbreviations so readers can easily figure out their meanings.

If you think you have used terms and phrases in your dissertation that readers might not be familiar with, you can create a glossary that lists important phrases and terms with their meanings explained.

Looking for dissertation help?

Researchprospect to the rescue then.

We have expert writers on our team who are skilled at helping students with quantitative dissertations across a variety of STEM disciplines. Guaranteeing 100% satisfaction!

Introduction

Introduction chapter briefly introduces the purpose and relevance of your research topic.

Here, you will be expected to list the aim and key objectives of your research so your readers can easily understand what the following chapters of the dissertation will cover. A good dissertation introduction section incorporates the following information:

- It provides background information to give context to your research.

- It clearly specifies the research problem you wish to address with your research. When creating research questions , it is important to make sure your research’s focus and scope are neither too broad nor too narrow.

- it demonstrates how your research is relevant and how it would contribute to the existing knowledge.

- It provides an overview of the structure of your dissertation. The last section of an introduction contains an outline of the following chapters. It could start off with something like: “In the following chapter, past literature has been reviewed and critiqued. The proceeding section lays down major research findings…”

- Theoretical framework – under a separate sub-heading – is also provided within the introductory chapter. Theoretical framework deals with the basic, underlying theory or theories that the research revolves around.

All the information presented under this section should be relevant, clear, and engaging. The readers should be able to figure out the what, why, when, and how of your study once they have read the introduction. Here are comprehensive guidelines on how to structure the introduction to the dissertation .

“Overwhelmed by tight deadlines and tons of assignments to write? There is no need to panic! Our expert academics can help you with every aspect of your dissertation – from topic creation and research problem identification to choosing the methodological approach and data analysis.”

Literature Review

The literature review chapter presents previous research performed on the topic and improves your understanding of the existing literature on your chosen topic. This is usually organised to complement your primary research work completed at a later stage.

Make sure that your chosen academic sources are authentic and up-to-date. The literature review chapter must be comprehensive and address the aims and objectives as defined in the introduction chapter. Here is what your literature research chapter should aim to achieve:

- Data collection from authentic and relevant academic sources such as books, journal articles and research papers.

- Analytical assessment of the information collected from those sources; this would involve a critiquing the reviewed researches that is, what their strengths/weaknesses are, why the research method they employed is better than others, importance of their findings, etc.

- Identifying key research gaps, conflicts, patterns, and theories to get your point across to the reader effectively.

While your literature review should summarise previous literature, it is equally important to make sure that you develop a comprehensible argument or structure to justify your research topic. It would help if you considered keeping the following questions in mind when writing the literature review:

- How does your research work fill a certain gap in exiting literature?

- Did you adopt/adapt a new research approach to investigate the topic?

- Does your research solve an unresolved problem?

- Is your research dealing with some groundbreaking topic or theory that others might have overlooked?

- Is your research taking forward an existing theoretical discussion?

- Does your research strengthen and build on current knowledge within your area of study? This is otherwise known as ‘adding to the existing body of knowledge’ in academic circles.

Tip: You might want to establish relationships between variables/concepts to provide descriptive answers to some or all of your research questions. For instance, in case of quantitative research, you might hypothesise that variable A is positively co-related to variable B that is, one increases and so does the other one.

Research Methodology

The methods and techniques ( secondary and/or primar y) employed to collect research data are discussed in detail in the Methodology chapter. The most commonly used primary data collection methods are:

- questionnaires

- focus groups

- observations

Essentially, the methodology chapter allows the researcher to explain how he/she achieved the findings, why they are reliable and how they helped him/her test the research hypotheses or address the research problem.

You might want to consider the following when writing methodology for the dissertation:

- Type of research and approach your work is based on. Some of the most widely used types of research include experimental, quantitative and qualitative methodologies.

- Data collection techniques that were employed such as questionnaires, surveys, focus groups, observations etc.

- Details of how, when, where, and what of the research that was conducted.

- Data analysis strategies employed (for instance, regression analysis).

- Software and tools used for data analysis (Excel, STATA, SPSS, lab equipment, etc.).

- Research limitations to highlight any hurdles you had to overcome when carrying our research. Limitations might or might not be mentioned within research methodology. Some institutions’ guidelines dictate they be mentioned under a separate section alongside recommendations.

- Justification of your selection of research approach and research methodology.

Here is a comprehensive article on how to structure a dissertation methodology .

Research Findings

In this section, you present your research findings. The dissertation findings chapter is built around the research questions, as outlined in the introduction chapter. Report findings that are directly relevant to your research questions.

Any information that is not directly relevant to research questions or hypotheses but could be useful for the readers can be placed under the Appendices .

As indicated above, you can either develop a standalone chapter to present your findings or combine them with the discussion chapter. This choice depends on the type of research involved and the academic subject, as well as what your institution’s academic guidelines dictate.

For example, it is common to have both findings and discussion grouped under the same section, particularly if the dissertation is based on qualitative research data.

On the other hand, dissertations that use quantitative or experimental data should present findings and analysis/discussion in two separate chapters. Here are some sample dissertations to help you figure out the best structure for your own project.

Sample Dissertation

Tip: Try to present as many charts, graphs, illustrations and tables in the findings chapter to improve your data presentation. Provide their qualitative interpretations alongside, too. Refrain from explaining the information that is already evident from figures and tables.

The findings are followed by the Discussion chapter , which is considered the heart of any dissertation paper. The discussion section is an opportunity for you to tie the knots together to address the research questions and present arguments, models and key themes.

This chapter can make or break your research.

The discussion chapter does not require any new data or information because it is more about the interpretation(s) of the data you have already collected and presented. Here are some questions for you to think over when writing the discussion chapter:

- Did your work answer all the research questions or tested the hypothesis?

- Did you come up with some unexpected results for which you have to provide an additional explanation or justification?

- Are there any limitations that could have influenced your research findings?

Here is an article on how to structure a dissertation discussion .

Conclusions corresponding to each research objective are provided in the Conclusion section . This is usually done by revisiting the research questions to finally close the dissertation. Some institutions may specifically ask for recommendations to evaluate your critical thinking.

By the end, the readers should have a clear apprehension of your fundamental case with a focus on what methods of research were employed and what you achieved from this research.

Quick Question: Does the conclusion chapter reflect on the contributions your research work will make to existing knowledge?

Answer: Yes, the conclusion chapter of the research paper typically includes a reflection on the research’s contributions to existing knowledge. In the “conclusion chapter”, you have to summarise the key findings and discuss how they add value to the existing literature on the current topic.

Reference list

All academic sources that you collected information from should be cited in-text and also presented in a reference list (or a bibliography in case you include references that you read for the research but didn’t end up citing in the text), so the readers can easily locate the source of information when/if needed.

At most UK universities, Harvard referencing is the recommended style of referencing. It has strict and specific requirements on how to format a reference resource. Other common styles of referencing include MLA, APA, Footnotes, etc.

Each chapter of the dissertation should have relevant information. Any information that is not directly relevant to your research topic but your readers might be interested in (interview transcripts etc.) should be moved under the Appendices section .

Things like questionnaires, survey items or readings that were used in the study’s experiment are mostly included under appendices.

An Outline of Dissertation/Thesis Structure

How can We Help you with your Dissertation?

If you are still unsure about how to structure a dissertation or thesis, or simply lack the motivation to kick start your dissertation project, you might be interested in our dissertation services .

If you are still unsure about how to structure a dissertation or thesis, or lack the motivation to kick start your dissertation project, you might be interested in our dissertation services.

Whether you need help with individual chapters, proposals or the full dissertation paper, we have PhD-qualified writers who will write your paper to the highest academic standard. ResearchProspect is UK-based, and a UK-registered business, which means the UK consumer law protects all our clients.

All You Need to Know About Us Learn More About Our Dissertation Services

FAQs About Structure a Dissertation

What does the title page of a dissertation contain.

The title page will contain details of the author/researcher, research topic , degree program (the paper is to be submitted for) and research supervisor’s name(s). The name of your university, logo, student number and submission date can also be presented on the title page.

What is the purpose of adding acknowledgement?

The acknowledgements section allows you to thank those who helped you with your dissertation project. You might want to mention the names of your academic supervisor, family members, friends, God and participants of your study whose contribution and support enabled you to complete your work.

Can I omit the glossary from the dissertation?

Yes, but only if you think that your paper does not contain any terms or phrases that the reader might not understand. If you think you have used them in the paper, you must create a glossary that lists important phrases and terms with their meanings explained.

What is the purpose of appendices in a dissertation?

Any information that is not directly relevant to research questions or hypotheses but could be useful for the readers can be placed under the Appendices, such as questionnaire that was used in the study.

Which referencing style should I use in my dissertation?

You can use any of the referencing styles such as APA, MLA, and Harvard, according to the recommendation of your university; however, almost all UK institutions prefer Harvard referencing style .

What is the difference between references and bibliography?

References contain all the works that you read up and used and therefore, cited within the text of your thesis. However, in case you read on some works and resources that you didn’t end up citing in-text, they will be referenced in what is called a bibliography.

Additional readings might also be present alongside each bibliography entry for readers.

You May Also Like

If your dissertation includes many abbreviations, it would make sense to define all these abbreviations in a list of abbreviations in alphabetical order.

Dissertation Methodology is the crux of dissertation project. In this article, we will provide tips for you to write an amazing dissertation methodology.

Your dissertation introduction chapter provides detailed information on the research problem, significance of research, and research aim & objectives.

USEFUL LINKS

LEARNING RESOURCES

COMPANY DETAILS

- How It Works

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Dissertation

How to Write a Dissertation | A Guide to Structure & Content

A dissertation or thesis is a long piece of academic writing based on original research, submitted as part of an undergraduate or postgraduate degree.

The structure of a dissertation depends on your field, but it is usually divided into at least four or five chapters (including an introduction and conclusion chapter).

The most common dissertation structure in the sciences and social sciences includes:

- An introduction to your topic

- A literature review that surveys relevant sources

- An explanation of your methodology

- An overview of the results of your research

- A discussion of the results and their implications

- A conclusion that shows what your research has contributed

Dissertations in the humanities are often structured more like a long essay , building an argument by analysing primary and secondary sources . Instead of the standard structure outlined here, you might organise your chapters around different themes or case studies.

Other important elements of the dissertation include the title page , abstract , and reference list . If in doubt about how your dissertation should be structured, always check your department’s guidelines and consult with your supervisor.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Be assured that you'll submit flawless writing. Upload your document to correct all your mistakes.

Table of contents

Acknowledgements, table of contents, list of figures and tables, list of abbreviations, introduction, literature review / theoretical framework, methodology, reference list.

The very first page of your document contains your dissertation’s title, your name, department, institution, degree program, and submission date. Sometimes it also includes your student number, your supervisor’s name, and the university’s logo. Many programs have strict requirements for formatting the dissertation title page .

The title page is often used as cover when printing and binding your dissertation .

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

The acknowledgements section is usually optional, and gives space for you to thank everyone who helped you in writing your dissertation. This might include your supervisors, participants in your research, and friends or family who supported you.

The abstract is a short summary of your dissertation, usually about 150-300 words long. You should write it at the very end, when you’ve completed the rest of the dissertation. In the abstract, make sure to:

- State the main topic and aims of your research

- Describe the methods you used

- Summarise the main results

- State your conclusions

Although the abstract is very short, it’s the first part (and sometimes the only part) of your dissertation that people will read, so it’s important that you get it right. If you’re struggling to write a strong abstract, read our guide on how to write an abstract .

In the table of contents, list all of your chapters and subheadings and their page numbers. The dissertation contents page gives the reader an overview of your structure and helps easily navigate the document.

All parts of your dissertation should be included in the table of contents, including the appendices. You can generate a table of contents automatically in Word.

If you have used a lot of tables and figures in your dissertation, you should itemise them in a numbered list . You can automatically generate this list using the Insert Caption feature in Word.

If you have used a lot of abbreviations in your dissertation, you can include them in an alphabetised list of abbreviations so that the reader can easily look up their meanings.

If you have used a lot of highly specialised terms that will not be familiar to your reader, it might be a good idea to include a glossary . List the terms alphabetically and explain each term with a brief description or definition.

In the introduction, you set up your dissertation’s topic, purpose, and relevance, and tell the reader what to expect in the rest of the dissertation. The introduction should:

- Establish your research topic , giving necessary background information to contextualise your work

- Narrow down the focus and define the scope of the research

- Discuss the state of existing research on the topic, showing your work’s relevance to a broader problem or debate

- Clearly state your objectives and research questions , and indicate how you will answer them

- Give an overview of your dissertation’s structure

Everything in the introduction should be clear, engaging, and relevant to your research. By the end, the reader should understand the what , why and how of your research. Not sure how? Read our guide on how to write a dissertation introduction .

Before you start on your research, you should have conducted a literature review to gain a thorough understanding of the academic work that already exists on your topic. This means:

- Collecting sources (e.g. books and journal articles) and selecting the most relevant ones

- Critically evaluating and analysing each source

- Drawing connections between them (e.g. themes, patterns, conflicts, gaps) to make an overall point

In the dissertation literature review chapter or section, you shouldn’t just summarise existing studies, but develop a coherent structure and argument that leads to a clear basis or justification for your own research. For example, it might aim to show how your research:

- Addresses a gap in the literature

- Takes a new theoretical or methodological approach to the topic

- Proposes a solution to an unresolved problem

- Advances a theoretical debate

- Builds on and strengthens existing knowledge with new data

The literature review often becomes the basis for a theoretical framework , in which you define and analyse the key theories, concepts and models that frame your research. In this section you can answer descriptive research questions about the relationship between concepts or variables.

The methodology chapter or section describes how you conducted your research, allowing your reader to assess its validity. You should generally include:

- The overall approach and type of research (e.g. qualitative, quantitative, experimental, ethnographic)

- Your methods of collecting data (e.g. interviews, surveys, archives)

- Details of where, when, and with whom the research took place

- Your methods of analysing data (e.g. statistical analysis, discourse analysis)

- Tools and materials you used (e.g. computer programs, lab equipment)

- A discussion of any obstacles you faced in conducting the research and how you overcame them

- An evaluation or justification of your methods

Your aim in the methodology is to accurately report what you did, as well as convincing the reader that this was the best approach to answering your research questions or objectives.

Next, you report the results of your research . You can structure this section around sub-questions, hypotheses, or topics. Only report results that are relevant to your objectives and research questions. In some disciplines, the results section is strictly separated from the discussion, while in others the two are combined.

For example, for qualitative methods like in-depth interviews, the presentation of the data will often be woven together with discussion and analysis, while in quantitative and experimental research, the results should be presented separately before you discuss their meaning. If you’re unsure, consult with your supervisor and look at sample dissertations to find out the best structure for your research.

In the results section it can often be helpful to include tables, graphs and charts. Think carefully about how best to present your data, and don’t include tables or figures that just repeat what you have written – they should provide extra information or usefully visualise the results in a way that adds value to your text.

Full versions of your data (such as interview transcripts) can be included as an appendix .

The discussion is where you explore the meaning and implications of your results in relation to your research questions. Here you should interpret the results in detail, discussing whether they met your expectations and how well they fit with the framework that you built in earlier chapters. If any of the results were unexpected, offer explanations for why this might be. It’s a good idea to consider alternative interpretations of your data and discuss any limitations that might have influenced the results.

The discussion should reference other scholarly work to show how your results fit with existing knowledge. You can also make recommendations for future research or practical action.

The dissertation conclusion should concisely answer the main research question, leaving the reader with a clear understanding of your central argument. Wrap up your dissertation with a final reflection on what you did and how you did it. The conclusion often also includes recommendations for research or practice.

In this section, it’s important to show how your findings contribute to knowledge in the field and why your research matters. What have you added to what was already known?

You must include full details of all sources that you have cited in a reference list (sometimes also called a works cited list or bibliography). It’s important to follow a consistent reference style . Each style has strict and specific requirements for how to format your sources in the reference list.

The most common styles used in UK universities are Harvard referencing and Vancouver referencing . Your department will often specify which referencing style you should use – for example, psychology students tend to use APA style , humanities students often use MHRA , and law students always use OSCOLA . M ake sure to check the requirements, and ask your supervisor if you’re unsure.

To save time creating the reference list and make sure your citations are correctly and consistently formatted, you can use our free APA Citation Generator .

Your dissertation itself should contain only essential information that directly contributes to answering your research question. Documents you have used that do not fit into the main body of your dissertation (such as interview transcripts, survey questions or tables with full figures) can be added as appendices .

Is this article helpful?

Other students also liked.

- What Is a Dissertation? | 5 Essential Questions to Get Started

- What is a Literature Review? | Guide, Template, & Examples

- How to Write a Dissertation Proposal | A Step-by-Step Guide

More interesting articles

- Checklist: Writing a dissertation

- Dissertation & Thesis Outline | Example & Free Templates

- Dissertation binding and printing

- Dissertation Table of Contents in Word | Instructions & Examples

- Dissertation title page

- Example Theoretical Framework of a Dissertation or Thesis

- Figure & Table Lists | Word Instructions, Template & Examples

- How to Choose a Dissertation Topic | 8 Steps to Follow

- How to Write a Discussion Section | Tips & Examples

- How to Write a Results Section | Tips & Examples

- How to Write a Thesis or Dissertation Conclusion

- How to Write a Thesis or Dissertation Introduction

- How to Write an Abstract | Steps & Examples

- How to Write Recommendations in Research | Examples & Tips

- List of Abbreviations | Example, Template & Best Practices

- Operationalisation | A Guide with Examples, Pros & Cons

- Prize-Winning Thesis and Dissertation Examples

- Relevance of Your Dissertation Topic | Criteria & Tips

- Research Paper Appendix | Example & Templates

- Thesis & Dissertation Acknowledgements | Tips & Examples

- Thesis & Dissertation Database Examples

- What is a Dissertation Preface? | Definition & Examples

- What is a Glossary? | Definition, Templates, & Examples

- What Is a Research Methodology? | Steps & Tips

- What is a Theoretical Framework? | A Step-by-Step Guide

- What Is a Thesis? | Ultimate Guide & Examples

Planning & Structuring your Chapters

This guide offers advice on the dissertation structure, how to plan and structure your chapters and how to develop your argument throughout your dissertation.

1. Dissertation Structure

A dissertation in the arts and humanities is usually a largely theoretical examination of a subject. The traditional structure of an arts and humanities dissertation is outlined below:

- Introduction

- Chapter 3....etc

- Bibliography

The content and structure of the main chapters will be determined by you. There are different ways of structuring these chapters which will be outlined in this guide. Choose a structure that best suits your dissertation topic.

In an arts & humanities dissertation you are aiming to have a clear argument throughout. The chapters are like a series of interlinked essays with a clear flow between them. You don't want them to feel like three isolated essays, your argument must be threaded through them all and tie them all together in your conclusion . There will be more advice on developing your argument later in this guide.

Dissertation structure varies between departments so make sure you check your module handbook for the preferred format. Past student dissertations are available through EPrints .

Dissertation Writing Groups

The invites applications for Humanities Dissertation Writing Groups. These competitive grants will encourage supportive and critical discussion of dissertation prospecti and drafts of dissertation chapters in the humanities.

The funds will provide support for small groups of interdisciplinary graduate students to convene regularly to share drafts of dissertation chapters and to discuss research and writing strategies for approaches to the group's common interdisciplinary focus. The selected groups of graduate students will meet throughout the 2024-25 academic year and, preferably, through the summer of 2025.

Grants of $250 per participant will be made available to groups of 4-5 participants who can demonstrate that their research interests productively converge. These groups would include students working in at least two different humanities graduate fields or groups within a single field whose research lends an interdisciplinary approach to their fields. The use of these funds will be flexible, from copying and dinner/refreshments to financial support for special research materials or trips to be shared by the group.

Applications should include a schedule of meetings (roughly one every 2-3 weeks) to be held in the course of the academic year, which would necessarily include regular circulation to the group of chapters-in-progress by each member. Such sessions should offer substantive response and discussion by the group of each individual chapter. If the groups consist of students who have very recently passed the A-Exam, their sessions could be focused on penning a prospectus.

All applicants must have completed the A-Exam by September 15, 2024, with at least two members of the group having completed the A-Exam by September 1, 2024.

The competition will be adjudicated by the Humanities Council.

Application Guidelines

Applications for Humanities Dissertation Writing Groups should be submitted by one member who will assume organizational responsibility for an additional stipend. Each writing group should consist of a minimum of four members (with no more than five) . Groups should be prepared to convene by September 1, 2024.

Applicants should submit the following materials as one .pdf file :

1. A dissertation writing group title and statement of no more than 750 words describing a rationale for linking the work of participants from different disciplines or disciplinary perspectives. The statement should show how each participant's perspective would contribute to elaborating and enriching a common context for writing.

2. A one-paragraph description of the dissertation project from each participant.

3. A CV for each member of the group.

4. A schedule of meetings and activities for the coming year. The basic requirement is a series of meetings organized around the circulation, presentation, and discussion of 2 chapters in progress by each member (a prospectus counts as a chapter).

No budget proposal is necessary.

Deadline: March 22, 2024

Please send all application materials in a single .pdf to Amanda Brockner at [email protected] .

How To Write A Dissertation Introduction

A Simple Explainer With Examples + Free Template

By: Derek Jansen (MBA) | Reviewed By Dr Eunice Rautenbach (D. Tech) | March 2020

If you’re reading this, you’re probably at the daunting early phases of writing up the introduction chapter of your dissertation or thesis. It can be intimidating, I know.

In this post, we’ll look at the 7 essential ingredients of a strong dissertation or thesis introduction chapter, as well as the essential things you need to keep in mind as you craft each section. We’ll also share some useful tips to help you optimize your approach.

Overview: Writing An Introduction Chapter

- The purpose and function of the intro chapter

- Craft an enticing and engaging opening section

- Provide a background and context to the study

- Clearly define the research problem

- State your research aims, objectives and questions

- Explain the significance of your study

- Identify the limitations of your research

- Outline the structure of your dissertation or thesis

A quick sidenote:

You’ll notice that I’ve used the words dissertation and thesis interchangeably. While these terms reflect different levels of research – for example, Masters vs PhD-level research – the introduction chapter generally contains the same 7 essential ingredients regardless of level. So, in this post, dissertation introduction equals thesis introduction.

Start with why.

To craft a high-quality dissertation or thesis introduction chapter, you need to understand exactly what this chapter needs to achieve. In other words, what’s its purpose ? As the name suggests, the introduction chapter needs to introduce the reader to your research so that they understand what you’re trying to figure out, or what problem you’re trying to solve. More specifically, you need to answer four important questions in your introduction chapter.

These questions are:

- What will you be researching? (in other words, your research topic)

- Why is that worthwhile? (in other words, your justification)

- What will the scope of your research be? (in other words, what will you cover and what won’t you cover)

- What will the limitations of your research be? (in other words, what will the potential shortcomings of your research be?)

Simply put, your dissertation’s introduction chapter needs to provide an overview of your planned research , as well as a clear rationale for it. In other words, this chapter has to explain the “what” and the “why” of your research – what’s it all about and why’s that important.

Simple enough, right?

Well, the trick is finding the appropriate depth of information. As the researcher, you’ll be extremely close to your topic and this makes it easy to get caught up in the minor details. While these intricate details might be interesting, you need to write your introduction chapter on more of a “need-to-know” type basis, or it will end up way too lengthy and dense. You need to balance painting a clear picture with keeping things concise. Don’t worry though – you’ll be able to explore all the intricate details in later chapters.

Now that you understand what you need to achieve from your introduction chapter, we can get into the details. While the exact requirements for this chapter can vary from university to university, there are seven core components that most universities will require. We call these the seven essential ingredients .

The 7 Essential Ingredients

- The opening section – where you’ll introduce the reader to your research in high-level terms

- The background to the study – where you’ll explain the context of your project

- The research problem – where you’ll explain the “gap” that exists in the current research

- The research aims , objectives and questions – where you’ll clearly state what your research will aim to achieve

- The significance (or justification) – where you’ll explain why your research is worth doing and the value it will provide to the world

- The limitations – where you’ll acknowledge the potential limitations of your project and approach

- The structure – where you’ll briefly outline the structure of your dissertation or thesis to help orient the reader

By incorporating these seven essential ingredients into your introduction chapter, you’ll comprehensively cover both the “ what ” and the “ why ” I mentioned earlier – in other words, you’ll achieve the purpose of the chapter.

Side note – you can also use these 7 ingredients in this order as the structure for your chapter to ensure a smooth, logical flow. This isn’t essential, but, generally speaking, it helps create an engaging narrative that’s easy for your reader to understand. If you’d like, you can also download our free introduction chapter template here.

Alright – let’s look at each of the ingredients now.

#1 – The Opening Section

The very first essential ingredient for your dissertation introduction is, well, an introduction or opening section. Just like every other chapter, your introduction chapter needs to start by providing a brief overview of what you’ll be covering in the chapter.

This section needs to engage the reader with clear, concise language that can be easily understood and digested. If the reader (your marker!) has to struggle through it, they’ll lose interest, which will make it harder for you to earn marks. Just because you’re writing an academic paper doesn’t mean you can ignore the basic principles of engaging writing used by marketers, bloggers, and journalists. At the end of the day, you’re all trying to sell an idea – yours is just a research idea.

So, what goes into this opening section?

Well, while there’s no set formula, it’s a good idea to include the following four foundational sentences in your opening section:

1 – A sentence or two introducing the overall field of your research.

For example:

“Organisational skills development involves identifying current or potential skills gaps within a business and developing programs to resolve these gaps. Management research, including X, Y and Z, has clearly established that organisational skills development is an essential contributor to business growth.”

2 – A sentence introducing your specific research problem.

“However, there are conflicting views and an overall lack of research regarding how best to manage skills development initiatives in highly dynamic environments where subject knowledge is rapidly and continuously evolving – for example, in the website development industry.”

3 – A sentence stating your research aims and objectives.

“This research aims to identify and evaluate skills development approaches and strategies for highly dynamic industries in which subject knowledge is continuously evolving.”.

4 – A sentence outlining the layout of the chapter.

“This chapter will provide an introduction to the study by first discussing the background and context, followed by the research problem, the research aims, objectives and questions, the significance and finally, the limitations.”

As I mentioned, this opening section of your introduction chapter shouldn’t be lengthy . Typically, these four sentences should fit neatly into one or two paragraphs, max. What you’re aiming for here is a clear, concise introduction to your research – not a detailed account.

PS – If some of this terminology sounds unfamiliar, don’t stress – I’ll explain each of the concepts later in this post.

#2 – Background to the study

Now that you’ve provided a high-level overview of your dissertation or thesis, it’s time to go a little deeper and lay a foundation for your research topic. This foundation is what the second ingredient is all about – the background to your study.

So, what is the background section all about?

Well, this section of your introduction chapter should provide a broad overview of the topic area that you’ll be researching, as well as the current contextual factors . This could include, for example, a brief history of the topic, recent developments in the area, key pieces of research in the area and so on. In other words, in this section, you need to provide the relevant background information to give the reader a decent foundational understanding of your research area.

Let’s look at an example to make this a little more concrete.

If we stick with the skills development topic I mentioned earlier, the background to the study section would start by providing an overview of the skills development area and outline the key existing research. Then, it would go on to discuss how the modern-day context has created a new challenge for traditional skills development strategies and approaches. Specifically, that in many industries, technical knowledge is constantly and rapidly evolving, and traditional education providers struggle to keep up with the pace of new technologies.

Importantly, you need to write this section with the assumption that the reader is not an expert in your topic area. So, if there are industry-specific jargon and complex terminology, you should briefly explain that here , so that the reader can understand the rest of your document.

Don’t make assumptions about the reader’s knowledge – in most cases, your markers will not be able to ask you questions if they don’t understand something. So, always err on the safe side and explain anything that’s not common knowledge.

#3 – The research problem

Now that you’ve given your reader an overview of your research area, it’s time to get specific about the research problem that you’ll address in your dissertation or thesis. While the background section would have alluded to a potential research problem (or even multiple research problems), the purpose of this section is to narrow the focus and highlight the specific research problem you’ll focus on.

But, what exactly is a research problem, you ask?

Well, a research problem can be any issue or question for which there isn’t already a well-established and agreed-upon answer in the existing research. In other words, a research problem exists when there’s a need to answer a question (or set of questions), but there’s a gap in the existing literature , or the existing research is conflicting and/or inconsistent.

So, to present your research problem, you need to make it clear what exactly is missing in the current literature and why this is a problem . It’s usually a good idea to structure this discussion into three sections – specifically:

- What’s already well-established in the literature (in other words, the current state of research)

- What’s missing in the literature (in other words, the literature gap)

- Why this is a problem (in other words, why it’s important to fill this gap)

Let’s look at an example of this structure using the skills development topic.

Organisational skills development is critically important for employee satisfaction and company performance (reference). Numerous studies have investigated strategies and approaches to manage skills development programs within organisations (reference).

(this paragraph explains what’s already well-established in the literature)

However, these studies have traditionally focused on relatively slow-paced industries where key skills and knowledge do not change particularly often. This body of theory presents a problem for industries that face a rapidly changing skills landscape – for example, the website development industry – where new platforms, languages and best practices emerge on an extremely frequent basis.

(this paragraph explains what’s missing from the literature)

As a result, the existing research is inadequate for industries in which essential knowledge and skills are constantly and rapidly evolving, as it assumes a slow pace of knowledge development. Industries in such environments, therefore, find themselves ill-equipped in terms of skills development strategies and approaches.

(this paragraph explains why the research gap is problematic)

As you can see in this example, in a few lines, we’ve explained (1) the current state of research, (2) the literature gap and (3) why that gap is problematic. By doing this, the research problem is made crystal clear, which lays the foundation for the next ingredient.

#4 – The research aims, objectives and questions

Now that you’ve clearly identified your research problem, it’s time to identify your research aims and objectives , as well as your research questions . In other words, it’s time to explain what you’re going to do about the research problem.

So, what do you need to do here?

Well, the starting point is to clearly state your research aim (or aims) . The research aim is the main goal or the overarching purpose of your dissertation or thesis. In other words, it’s a high-level statement of what you’re aiming to achieve.

Let’s look at an example, sticking with the skills development topic:

“Given the lack of research regarding organisational skills development in fast-moving industries, this study will aim to identify and evaluate the skills development approaches utilised by web development companies in the UK”.

As you can see in this example, the research aim is clearly outlined, as well as the specific context in which the research will be undertaken (in other words, web development companies in the UK).

Next up is the research objective (or objectives) . While the research aims cover the high-level “what”, the research objectives are a bit more practically oriented, looking at specific things you’ll be doing to achieve those research aims.

Let’s take a look at an example of some research objectives (ROs) to fit the research aim.

- RO1 – To identify common skills development strategies and approaches utilised by web development companies in the UK.

- RO2 – To evaluate the effectiveness of these strategies and approaches.

- RO3 – To compare and contrast these strategies and approaches in terms of their strengths and weaknesses.

As you can see from this example, these objectives describe the actions you’ll take and the specific things you’ll investigate in order to achieve your research aims. They break down the research aims into more specific, actionable objectives.

The final step is to state your research questions . Your research questions bring the aims and objectives another level “down to earth”. These are the specific questions that your dissertation or theses will seek to answer. They’re not fluffy, ambiguous or conceptual – they’re very specific and you’ll need to directly answer them in your conclusions chapter .

The research questions typically relate directly to the research objectives and sometimes can look a bit obvious, but they are still extremely important. Let’s take a look at an example of the research questions (RQs) that would flow from the research objectives I mentioned earlier.

- RQ1 – What skills development strategies and approaches are currently being used by web development companies in the UK?

- RQ2 – How effective are each of these strategies and approaches?

- RQ3 – What are the strengths and weaknesses of each of these strategies and approaches?

As you can see, the research questions mimic the research objectives , but they are presented in question format. These questions will act as the driving force throughout your dissertation or thesis – from the literature review to the methodology and onward – so they’re really important.

A final note about this section – it’s really important to be clear about the scope of your study (more technically, the delimitations ). In other words, what you WILL cover and what you WON’T cover. If your research aims, objectives and questions are too broad, you’ll risk losing focus or investigating a problem that is too big to solve within a single dissertation.

Simply put, you need to establish clear boundaries in your research. You can do this, for example, by limiting it to a specific industry, country or time period. That way, you’ll ringfence your research, which will allow you to investigate your topic deeply and thoroughly – which is what earns marks!

Need a helping hand?

#5 – Significance

Now that you’ve made it clear what you’ll be researching, it’s time to make a strong argument regarding your study’s importance and significance . In other words, now that you’ve covered the what, it’s time to cover the why – enter essential ingredient number 5 – significance.

Of course, by this stage, you’ve already briefly alluded to the importance of your study in your background and research problem sections, but you haven’t explicitly stated how your research findings will benefit the world . So, now’s your chance to clearly state how your study will benefit either industry , academia , or – ideally – both . In other words, you need to explain how your research will make a difference and what implications it will have .

Let’s take a look at an example.

“This study will contribute to the body of knowledge on skills development by incorporating skills development strategies and approaches for industries in which knowledge and skills are rapidly and constantly changing. This will help address the current shortage of research in this area and provide real-world value to organisations operating in such dynamic environments.”

As you can see in this example, the paragraph clearly explains how the research will help fill a gap in the literature and also provide practical real-world value to organisations.

This section doesn’t need to be particularly lengthy, but it does need to be convincing . You need to “sell” the value of your research here so that the reader understands why it’s worth committing an entire dissertation or thesis to it. This section needs to be the salesman of your research. So, spend some time thinking about the ways in which your research will make a unique contribution to the world and how the knowledge you create could benefit both academia and industry – and then “sell it” in this section.

#6 – The limitations

Now that you’ve “sold” your research to the reader and hopefully got them excited about what’s coming up in the rest of your dissertation, it’s time to briefly discuss the potential limitations of your research.

But you’re probably thinking, hold up – what limitations? My research is well thought out and carefully designed – why would there be limitations?

Well, no piece of research is perfect . This is especially true for a dissertation or thesis – which typically has a very low or zero budget, tight time constraints and limited researcher experience. Generally, your dissertation will be the first or second formal research project you’ve ever undertaken, so it’s unlikely to win any research awards…

Simply put, your research will invariably have limitations. Don’t stress yourself out though – this is completely acceptable (and expected). Even “professional” research has limitations – as I said, no piece of research is perfect. The key is to recognise the limitations upfront and be completely transparent about them, so that future researchers are aware of them and can improve the study’s design to minimise the limitations and strengthen the findings.

Generally, you’ll want to consider at least the following four common limitations. These are:

- Your scope – for example, perhaps your focus is very narrow and doesn’t consider how certain variables interact with each other.

- Your research methodology – for example, a qualitative methodology could be criticised for being overly subjective, or a quantitative methodology could be criticised for oversimplifying the situation (learn more about methodologies here ).

- Your resources – for example, a lack of time, money, equipment and your own research experience.

- The generalisability of your findings – for example, the findings from the study of a specific industry or country can’t necessarily be generalised to other industries or countries.

Don’t be shy here. There’s no use trying to hide the limitations or weaknesses of your research. In fact, the more critical you can be of your study, the better. The markers want to see that you are aware of the limitations as this demonstrates your understanding of research design – so be brutal.

#7 – The structural outline

Now that you’ve clearly communicated what your research is going to be about, why it’s important and what the limitations of your research will be, the final ingredient is the structural outline.The purpose of this section is simply to provide your reader with a roadmap of what to expect in terms of the structure of your dissertation or thesis.