- Spencer Greenberg

- Nov 26, 2018

- 11 min read

12 Ways To Draw Conclusions From Information

Updated: Sep 25, 2023

There are a LOT of ways to make inferences – that is, for drawing conclusions based on information, evidence or data. In fact, there are many more than most people realize. All of them have strengths and weaknesses that render them more useful in some situations than in others.

Here's a brief key describing most popular methods of inference, to help you whenever you're trying to draw a conclusion for yourself. Do you rely more on some of these than you should, given their weaknesses? Are there others in this list that you could benefit from using more in your life, given their strengths? And what does drawing conclusions mean, really? As you'll learn in a moment, it encompasses a wide variety of techniques, so there isn't one single definition.

1. Deduction

Common in: philosophy, mathematics

If X, then Y, due to the definitions of X and Y.

X applies to this case.

Therefore Y applies to this case.

Example: “Plato is a mortal, and all mortals are, by definition, able to die; therefore Plato is able to die.”

Example: “For any number that is an integer, there exists another integer greater than that number. 1,000,000 is an integer. So there exists an integer greater than 1,000,000.”

Advantages: When you use deduction properly in an appropriate context, it is an airtight form of inference (e.g. in a mathematical proof with no mistakes).

Flaws: To apply deduction to the world, you need to rely on strong assumptions about how the world works, or else apply other methods of inference on top. So its range of applicability is limited.

2. Frequencies

Common in: applied statistics, data science

95% of the time that X occurred in the past, Y occurred also.

X occurred.

Therefore Y is likely to occur (with high probability).

Example: “95% of the time when we saw a bank transaction identical to this one, it was fraudulent. So this transaction is fraudulent.”

Advantages: This technique allows you to assign probabilities to events. When you have a lot of past data it can be easy to apply.

Flaws: You need to have a moderately large number of examples like the current one to perform calculations on. Also, the method assumes that those past examples were drawn from a process that is (statistically) just like the one that generated this latest example. Moreover, it is unclear sometimes what it means for “X”, the type of event you’re interested in, to have occurred. What if something that’s very similar to but not quite like X occurred? Should that be counted as X occurring? If we broaden our class of what counts as X or change to another class of event that still encompasses all of our prior examples, we’ll potentially get a different answer. Fortunately, there are plenty of opportunities to make inferences from frequencies where the correct class to use is fairly obvious.

If you've found this article valuable so far, you may also like our free tool

Common in : financial engineering, risk modeling, environmental science

Given our probabilistic model of this thing, when X occurs, the probability of Y occurring is 0.95.

Example: “Given our multivariate Gaussian model of loan prices, when this loan defaults there is a 0.95 probability of this other loan defaulting.”

Example: "When we run the weather simulation model many times with randomization of the initial conditions, rain occurs tomorrow in that region 95% of the time."

Advantages: This technique can be used to make predictions in very complex scenarios (e.g. involving more variables than a human mind can take into account at once) as long as the dynamics of the systems underlying those scenarios are sufficiently well understood.

Flaws: This method hinges on the appropriateness of the model chosen; it may require a large amount of past data to estimate free model parameters, and may go haywire if modeling assumptions are unrealistic or suddenly violated by changes in the world. You may have to already understand the system deeply to be able to build the model in the first place (e.g. with weather modeling).

4. Classification

Common in: machine learning, data science

In prior data, as X1 and X2 increased, the likelihood of Y increased.

X1 and X2 are at high levels.

Therefore Y is likely to occur.

Example: “Height for children can be approximately predicted as an (increasing) linear function of age (X1) and weight (X2). This child is older and heavier than the others, so we predict he is likely to be tall.”

Example: "We've trained a neural network to predict whether a particular batch of concrete will be strong based on its constituents, mixture proportion, compaction, etc."

Advantages: This method can often produce accurate predictions for systems that you don't have much understanding of, as long as enough data is available to train the regression algorithm and that data contains sufficiently relevant variables.

Flaws: This method is often applied with simple assumptions (e.g. linearity) that may not capture the complexity of the inference problem, but very large amounts of data may be needed to apply much more complex models (e.g to use neural networks, which are non-linear). Regression also may produce results that are hard to interpret – you may not really understand why it does a good job of making predictions.

5. Bayesianism

Common in: the rationality community

Given my prior odds that Y is true...

And given evidence X...

And given my Bayes factor, which is my estimate of how much more likely X is to occur if Y is true than if Y is not true...

I calculate that Y is far more likely to be true than to not be true (by multiplying the prior odds by the Bayes factor to get the posterior odds).

Therefore Y is likely to be true (with high probability).

Example: “My prior odds that my boss is angry at me were 1 to 4, because he’s angry at me about 20% of the time. But then he came into my office shouting and flipped over my desk, which I estimate is 200 times more likely to occur if he’s angry at me compared to if he’s not. So now the odds of him being angry at me are 200 * (1/4) = 50 to 1 in favor of him being angry.”

Example: "Historically, companies in this situation have 2 to 1 odds of defaulting on their loans. But then evidence came out about this specific company showing that it is 3 times more likely to end up defaulting on its loans than similar companies. Hence now the odds of it defaulting are 6 to 1 since: (2/1) * (3/1) = 6. That means there is an 85% chance that it defaults since 0.85 = 6/(6+1)."

Advantages: If you can do the calculations in a given instance, and have a sensible way to set your prior probabilities, this is probably the mathematically optimal framework to use for probabilistic prediction. For instance, if you have a belief about the probability of something, then you gain some new evidence, you can prove mathematically that Bayes's rule tells you how to calculate what your new probability should now be that incorporates that evidence. In that sense, we can think of many of the other approaches on this list as (hopefully pragmatic) approximations of Bayesianism (sometimes good approximations, sometimes bad ones).

Flaws: It's sometimes hard to know how to set your prior odds, and it can be very hard in some cases to perform the Bayesian calculation. In practice, carrying out the calculation might end up relying on subjective estimates of the odds, which can be especially tricky to guess when the evidence is not binary (i.e not of the form “happened” vs. “didn’t happen”), or if you have lots of different pieces of evidence that are partially correlated.

If you’d like to learn more about using Bayesian inference in everyday life, try our mini-course on The Question of Evidence . For a more math-oriented explanation, check out our course on Understanding Bayes’s Theorem .

6. Theories

Common in: psychology, economics

Given our theory, when X occurs, Y occurs.

Therefore Y will occur.

Example: “One theory is that depressed people are most at risk for suicide when they are beginning to come out of a really bad depression. So as depression is remitting, patients should be carefully screened for potentially increasing suicide risk factors.”

Example: “A common theory is that when inflation rises, unemployment falls. Inflation is rising, so we should predict that unemployment will fall.”

Advantages: Theories can make systems far more understandable to the human mind, and can be taught to others. Sometimes even very complex systems can be pretty well approximated with a simple theory. Theories allow us to make predictions about what will happen while only having to focus on a small amount of relevant information, without being bogged down by thousands of details.

Flaws: It can be very challenging to come up with reliable theories, and often you will not know how accurate such a theory is. Even if it has substantial truth to it and is right often, there may be cases where the opposite of what was predicted actually happens, and for reasons the theory can’t explain. Theories usually only capture part of what is going on in a particular situation, ignoring many variables so as to be more understandable. People often get too attached to particular theories, forgetting that theories are only approximations of reality, and so pretty much always have exceptions.

Common in: engineering, biology, physics

We know that X causes Y to occur.

Example: “Rusting of gears causes increased friction, leading to greater wear and tear. In this case, the gears were heavily rusted, so we expect to find a lot of wear.”

Example: “This gene produces this phenotype, and we see that this gene is present, so we expect to see the phenotype in the offspring.”

Advantages: If you understand the causal structure of a system, you may be able to make many powerful predictions about it, including predicting what would happen in many hypothetical situations that have never occurred before, and predicting what would happen if you were to intervene on the system in a particular way. This contrasts with (probabilistic) models that may be able to accurately predict what happens in common situations, but perform badly at predicting what will happen in novel situations and in situations where you intervene on the system (e.g. what would happen to the system if I purposely changed X).

Flaws: It’s often extremely hard to figure out causality in a highly complex system, especially in “softer” or "messier" subjects like nutrition and the social sciences. Purely statistical information (even an infinite amount of it) is not enough on its own to fully describe the causality of a system; additional assumptions need to be added. Often in practice we can only answer questions about causality by running randomized experiments (e.g. randomized controlled trials), which are typically expensive and sometimes infeasible, or by attempting to carefully control for all the potential confounding variables, a challenging and error-prone process.

Common in: politics, economics

This expert (or prediction market, or prediction algorithm) X is 90% accurate at predicting things in this general domain of prediction.

X predicts Y.

Example: “This prediction market has been right 90% of the time when predicting recent baseball outcomes, and in this case predicts the Yankees will win.”

Advantages: If you can find an expert or algorithm that has been proven to make reliable predictions in a particular domain, you can simply use these predictions yourself without even understanding how they are made.

Flaws: We often don’t have access to the predictions of experts (or of prediction markets, or prediction algorithms), and when we do, we usually don’t have reliable measures of their past accuracy. What's more, many experts whose predictions are publicly available have no clear track record of performance, or even purposely avoid accountability for poor performance (e.g. by hiding past prediction failures and touting past successes).

9. Metaphors

Common in: self-help, ancient philosophy, science education

X, which is what we are dealing with now, is metaphorically a Z.

For Z, when W is true, then obviously Y is true.

Now W (or its metaphorical equivalent) is true for X.

Therefore Y is true for X.

Example: “Your life is but a boat, and you are riding on the waves of your experiences. When a raging storm hits, a boat can’t be under full sail. It can’t continue at its maximum speed. You are experiencing a storm now, and so you too must learn to slow down.”

Example: "To better understand the nature of gasses, imagine tons of ping pong balls all shooting around in straight lines in random directions, and bouncing off of each other whenever they collide. These ping pong balls represent molecules of gas. Assuming the system is not inside a container, ping pong balls at the edges of the system have nothing to collide with, so they just fly outward, expanding the whole system. Similarly, the volume of a gas expands when it is placed in a vacuum."

Advantages: Our brains are good at understanding metaphors, so they can save us mental energy when we try to grasp difficult concepts. If the two items being compared in the metaphor are sufficiently alike in relevant ways, then the metaphor may accurately reveal elements of how its subject works.

Flaws: Z working as a metaphor for X doesn’t mean that all (or even most) predictions that are accurate for situations involving Z are appropriate (or even make any sense) for X. Metaphor-based reasoning can seem profound and persuasive even in cases when it makes little sense.

10. Similarities

Common in: the study of history, machine learning

X occurred, and X is very similar to Z in properties A, B and C.

When things similar to Z in properties A, B, and C occur, Y usually occurs.

Example: “This conflict is similar to the Gulf War in various ways, and from what we've learned about wars like the Gulf War, we can expect these sorts of outcomes.”

Example: “This data point (with unknown label) is closest in feature space to this other data point which is labeled ‘cat’, and all the other labeled points around that point are also labeled ‘cat’, so this unlabeled point should also likely get the label ‘cat’.”

Advantages: This approach can be applied at both small scale (with small numbers of examples) and at large scale (with millions of examples, as in machine learning algorithms), though of course large numbers of examples tend to produce more robust results. It can be viewed as a more powerful generalization of "frequencies"-based reasoning.

Flaws: In the history case, it is difficult to know which features are the appropriate ones to use to evaluate the similarity of two cases, and often the conclusions this approach produces are based on a relatively small number of examples. In the machine learning case, a very large amount of data may be needed to train the model (and it still may be unclear how to measure which examples are similar to which other cases, even with a lot of data). The properties you're using to compare cases must be sufficiently relevant to the prediction being made for it to work.

11. Anecdotes

Common in: daily life

In this handful of examples (or perhaps even just one example) where X occurred, Y occurred.

Example: “The last time we took that so-called 'shortcut' home, we got stuck in traffic for an extra 45 minutes. Let's not make that mistake again.”

Example: “My friend Bob tried that supplement and said it gave him more energy. So maybe it will give me more energy too."

Advantages: Anecdotes are simple to use, and a few of them are often all we have to work with for inference.

Flaws: Unless we are in a situation with very little noise/variability, a few examples likely will not be enough to accurately generalize. For instance, a few examples is not enough to make a reliable judgement about how often something occurs.

12. Intuition

My intuition (that I may have trouble explaining) predicts that when X occurs, Y is true.

Therefore Y is true.

Example: “The tone of voice he used when he talked about his family gave me a bad vibe. My feeling is that anyone who talks about their family with that tone of voice probably does not really love them.”

Example: "I can't explain why, but I'm pretty sure he's going to win this election."

Advantages: Our intuitions can be very well honed in situations we’ve encountered many times, and that we've received feedback on (i.e. where there was some sort of answer we got about how well our intuition performed). For instance, a surgeon who has conducted thousands of heart surgeries may have very good intuitions about what to do during surgery, or about how the patient will fare, even potentially very accurate intuitions that she can't easily articulate.

Flaws: In novel situations, or in situations where we receive no feedback on how well our instincts are performing, our intuitions may be highly inaccurate (even though we may not feel any less confident about our correctness).

Do you want to learn more about drawing conclusions from data?

If you'd like to know more about when intuition is reliable, try our 7-question guide to determining when you can trust your intuition.

We also have a full podcast episode about Mental models that apply across disciplines that you may like:

Click here to access other streaming options and show notes.

Recent Posts

How to think about group differences

How to decide between competing explanations and theories

How collective memories can sometimes be inaccurate: Investigating the Mandela Effect

Reading Comprehension Strategy #4: Drawing Conclusions

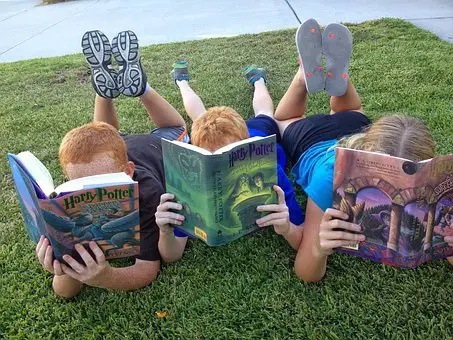

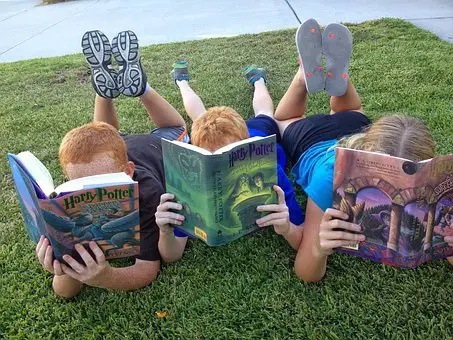

Today’s post in our reading comprehension series is about drawing conclusions by going beyond the words on the page.

When a reader collects clues from the text, they can make a variety of types of educated guesses that help them understand what they are reading. It allows them to draw out more information from the text and understand humor.

Drawing conclusions can be a particularly hard task for some readers. Below, I break down how we can help our children develop this skill during other tasks, including games and then apply the skills they have learned to reading.

Click here to read the last three posts about visualizing what we read, connecting background knowledge with what we read , and asking questions while we read .

(Note: This post contains affiliate links for your convenience. Click here to read our full disclosure . )

How We Draw Conclusions

We draw conclusions by collecting clues as we read and then put them together to make an educated guess. What clues do you gather while you read the following excerpt?

“Well get a move on, I want you to look after the bacon. And don’t you dare let it burn, I want everything perfect on Duddy’s birthday.”

Harry groaned.

“What did you say?” his aunt snapped through the door.

“Nothing, nothing…”

Dudley’s birthday — how could he have forgotten? Harry got slowly out of bed and started looking for socks. He found a pair under his bed and, after pulling a spider off one of them, put them on. Harry was used to spiders, because the cupboard under the stairs was full of them, and that was where he slept.”

Now, I did not give you any more direction than to just gather clues. But, if you were using this exercise to help your child build the skill of drawing conclusions, you could have asked them to specifically collect clues about how Harry and his aunt get along.

In this case, we have the clue of the aunt not speaking very nicely to Harry…”get a move on” and “don’t you dare let it burn”. We also have the clue of Harry groaning instead of answering in an excited way about Duddy’s birthday. And then his aunt “snaps”. Next we learn that Harry sleeps in a cupboard under the stairs that is full of spiders. That is a big clue! We can determine from all of this information that Harry and his aunt do not get along well.

How characters feel about each other in a story is just one of several different types of conclusions a reader might draw from a text they are reading. Here are some other important types of conclusions, we learn to make…

Types of Conclusions

Predict what will happen next. We often read to see what happens next in a story. As you are reading, your brain is collecting clues and you may envision where a story is headed. Sometimes an author may throw a plot twist in there and take the story in a different direction. Sometimes the author might use foreshadowing to give you bread crumbs to follow through the story. Rosie’s Walk by Pat Hutchins is a picture book with almost no words. But the pictures help us draw the conclusion early on that the fox is going to keep following the hen around the barnyard getting into one accident after another.

- Hutchins, Pat (Author)

- English (Publication Language)

- 32 Pages - 08/01/1971 (Publication Date) - Aladdin (Publisher)

Determine the meaning of an unknown word. When we encounter a word we don’t know in our reading, we need to ask some questions to draw a conclusion about its meaning…What is the thing being used for? Is this action being described in a positive or negative way? What else do we know about this person? If we ask the right questions and make good educated guesses we may be able to determine the meaning of the word without interrupting our reading to look it up. This is referred to as using context clues.

A really fun way to work on this skill is with books that incorporate a few words from another language in the book. Everyone can work together to use the clues from the pictures and the words around them to figure out what the word from another language means. Isla and Abuela by Arthur Dorros are two books to get you started.

- Dorros, Arthur (Author)

- 40 Pages - 05/01/1997 (Publication Date) - Puffin Books (Publisher)

Connect different points in the story. Something might be revealed in a story (or movie) that fills in another part of the storyline. Marvel movies do this all the time! We recently watched Ant-Man and the Wasp and at the end of the movie, a clue is given that connects the movie to the end of another movie, Avengers: Infinity War. A savvy watcher realizes that the events in the two movies have been occurring at the same time.

Fill in blank spots in the movie you are making in your mind. In our first article in this series , we talked about visualizing what you are reading. One example I included was a description of Marilla in Anne of Green Gables. We are told that she is tall and thin and that her hair has gray streaks. We can then draw the conclusion that she is old enough to have gray hair and fill in her age in the movie we are making in our mind. We are not told what she is wearing so we need to work harder to collect clues from different parts of the text to fill in her clothing in the movie in our mind.

Answer questions that you might have wondered. You may have questions you wonder while you are reading that are not answered explicitly by the text. Instead, you have to collect clues and make your own prediction. Maybe you have wondered what happened in a character’s past to make him so mean. As his past is revealed throughout the story, you can draw conclusions to answer your question.

But we don’t just draw conclusions while reading…

Drawing Conclusions in the Real World

We draw conclusions from the world around us all the time and this is a skill that can be taught at a very early age.

See dark clouds outside? It is probably going to rain.

Are the clouds really tall? Then it might mean a thunderstorm.

Are the leaves turning red, yellow, and orange? They will fall off the tree soon and the temperatures will get cooler and the days will be shorter.

Go to a store and there are no cars in the parking lot? As you approach, you notice that the store is dark. You draw the conclusion that the store is closed.

These are all observations you can point out to young children. At first you will probably need to model your conclusion for them. But eventually you could make the observation and then say “You know what that means?” and give them a chance to draw a conclusion. Pretty soon they will notice the clues on their own and come to you and share their observations and conclusions.

Continue to look for other examples where you can point out clues in your child’s world and help them draw conclusions. Then carry this skill and these examples over to the books you read.

Drawing Conclusions from Pictures

Picture books are a great way to start drawing conclusions in books. You can start by calling attention to details in the pictures just like in the above “real world” examples.

For example, in the book The Day the Crayons Quit by Drew Daywalt , each crayon has written a letter of complaint and there is a picture that goes with each letter. Before reading the letters to your children, you could have them look at the accompanying picture and see if they can guess what the letter might be about. Even older children would have fun with this.

- Funny back-to-school story.

- Duncan's crayons quit coloring. Crayons have feelings, too.

- What can Duncan do to appease the crayons and get them back coloring?

- Contains 40 pages and measures 9.25" x 6.25".

- Recommended for ages 3 - 7 years.

The Perfect School Picture by Deborah Diesen is another book where you could have kids look at the pictures and predict what problems might show up in the main character’s school picture. You could then read each page to add information to what your child has noticed and at the end of the book see how the picture day went.

- Diesen, Deborah (Author)

- 32 Pages - 07/02/2019 (Publication Date) - Abrams Books for Young Readers (Publisher)

If You Give a Mouse a Cookie by Laura Numeroff is another picture book that is great for practicing predicting what will happen next. Kids won’t be able to use pictures this time. They will have to think about word associations. When the mouse is given each object, prompt kids to think about what that object might make him want next.

- For Mac system 7.0 or later (OSX in CLASSIC OS)

- Interactive book

- Hardcover Book

- Numeroff, Laura (Author)

With older kids, you can use cartoons as picture prompts to draw conclusions. In a recent Calvin and Hobbes cartoon , Calvin is yelling at someone who has left the scene. After looking at the cartoon with your child, you could ask him what he wonders about the cartoon. And then ask him what a possible answer might be to what he wonders. Finally, ask him what makes him thinks that .

Regardless of how your child responds, praise anything they share. If your children think there are “right” and “wrong” answers, then they may hesitate to share any thoughts about the pictures.

If you find your child is reluctant to answer, you can model by wondering something aloud, coming up with an answer, and then pointing out why you think that. As you model be intentional with your language…talk about searching for clues . Say you are making a prediction . When we label steps like this for our children they understand better what we are doing and can cue themselves using those same words as they work through the steps.

In our last post about asking questions , we talked about looking at the cover of the book and prompting your child to wonder something about what they see. Now you can prompt two more steps… guessing an answer and giving resaons for why they think that is the answer.

Games You Can Play

There are several games you can play with your children to help them work on drawing conclusions. These games will help children learn to pay attention to clues, ask good questions, draw on their background knowledge to apply it to the current situation, and make educated guesses.

Charades , where a person acts out something, and everyone else has to guess what it is, is a great game to work on drawing conclusions.

Twenty Questions adds language to the guessing game. Someone thinks of a person, place, or thing and the other people can ask up to 20 yes/no questions to narrow down choices and guess what the person is thinking of.

Another language game is a Simile Game. Someone starts a simile and other people fill in the blank. The first person might start with “As shiny as a __________.” The other players may say “gold”, “foil”, “a star” or any other object that pops into their head.

There are also commercial language games that help children learn to draw conclusions such as Hedbanz and Taboo .

- ALL NEW GAME: It’s the 2nd edition of the quick question “What am I?” game! Includes 6 new bands- Dino, Narwhal, Robot, Flower, Butterfly, & Brain PLUS 25 bonus cards in this Walmart exclusive version!

- SIMPLE TO PLAY: Pick a headband, place a card in it and play to figure out what’s shown on your card. Using yes/no questions, be the first to guess 3 cards correctly and you win!

- FAMILY GAME NIGHT: Hedbanz is a must-have in your collection of family games for kids and adults. It is for everyone ages 6 and up. For 2-6 players, bring along when you are in need of fun board games for family night.

- SPIN MASTER PUZZLES, TOYS & GAMES: A world of jigsaw puzzles and family board games for kids, teens, and adults. Plus strategy, cards, and classic board games like dominoes, mahjong, or a chess set.

- ENTERTAINMENT FOR EVERYONE: When you are with friends, bring a Spin Master game, toy, or cards. For family game nights, birthday gifts, party games, travel, and whenever you just want to have fun.

- GAME FOR KIDS TO CHALLENGE PARENTS: Gather the family together It's kids vs. parents in this edition of the Taboo game

- TWO DIFFERENT CARD DECKS: The hilarious kids vs. parents game is a fun twist on the classic Taboo game. It includes a kids' deck and an adult deck of cards. The kids' deck features familiar Guess words and only 2 forbidden words

- THE GAME OF FORBIDDEN WORDS: Includes over 1, 000 Guess words on 260 cards; get teammates to say the Guess word on the card without saying the forbidden words

- INCLUDES A SQUEAKER: Oops Say a forbidden word shown on the card and opponents will squeak the squeaker and the other team gets the point

- FUN, FAST-PACED GAME: Race against the included one-minute timer in this fun and fast-paced family game

These games are a great way to get ready for what our goal is…

Drawing Conclusions While Reading

By the time your child gets to reading full-length books, they have had lots of practice drawing conclusions. However, they may need some help connecting that process to a full-length book. Read alouds , once again, are a great way to support them through this process.

Start by wondering some questions while looking at the cover of the book and then make some predictions as you start to read. Look for clues along the way to see if your predictions were correct or if you need to revise them as you go. You may need to go look at the cover again or reread an earlier passage as you revise your predictions. You may elaborate on your predictions, tweak them, or throw them out all together and come up with new ones.

As always, if your children are having trouble coming up with ideas on their own, model your thinking out loud. Use words like search , clues , predict , and conclude . Show your children how you are bringing in background knowledge to help you make your predictions.

Here are some sentence starters you can model and then prompt your children with:

- I wonder…

- An answer might be…

- I think this book will be about…

- I predict…

- I think next _____________ will happen.

- My guess is… (Using the word ‘guess’ keeps the pressure down.)

- I think that because…

- Ooh, this is a surprise… (For when you need to revise your predictions.)

- My conclusion is…

Remember to always praise any thinking your children do even if you think it is way off base. This will keep them thinking and offering ideas! And remember to use these same strategies to help you figure out unknown words and to fill in some details in the movies you are making in your minds.

If you feel your child needs some more intentional practice with drawing conclusions, check out the Inference Jones series of workbooks from the Critical Thinking Co.

- Robert E. Owen (Author)

- 48 Pages - 07/02/2024 (Publication Date) - The Critical Thinking (Publisher)

As you can see, each of the strategies we have talked about in this series connect to each other. To keep it simple, it is best to pick one strategy to focus on for a week or two. Once you feel comfortable using it during a read aloud, add in another strategy for a week or two and think about how you can connect them together. If you start to feel that you have too many things to focus on while reading, back off on some of them and practice just one or two strategies until they become a natural part of the reading process.

Next week, we will cover the reading comprehension strategy of determining what is important. This is another higher level skill that is necessary to reading informative texts and is critical to learning. So make sure to come back next week for some concrete strategies.

If you enjoyed this post then you may be interested in reading 7 Keys to Comprehension: How to Help Your Kids Read It and Get It!

- Zimmermann, Susan (Author)

- 224 Pages - 07/22/2003 (Publication Date) - Harmony (Publisher)

Newest Product

Join Our FREE Resource Library

Complete the Form:

Our Math Program

Our Spelling Program

How We Learned to Read

Our Astronomy Program

Search by Category

- Family Field Trips

- FREE Unit Studies

- Fun Homeschooling Ideas

- Help for Struggling Learners

- Homeschool Reviews

- How To Teach Your Child

- Number Sense

- Organizing Your Homeschool

- Teaching Academic Subjects

- Teaching Life Skills

- Uncategorized

© Peanut Butter Fish Lessons 2016 – Present

Privacy Overview

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |

Last updated 27/06/24: Online ordering is currently unavailable due to technical issues. We apologise for any delays responding to customers while we resolve this. For further updates please visit our website: https://www.cambridge.org/news-and-insights/technical-incident

We use cookies to distinguish you from other users and to provide you with a better experience on our websites. Close this message to accept cookies or find out how to manage your cookie settings .

Login Alert

- > How to Do Research

- > Draw conclusions and make recommendations

Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction: Types of research

- Part 1 The research process

- 1 Develop the research objectives

- 2 Design and plan the study

- 3 Write the proposal

- 4 Obtain financial support for the research

- 5 Manage the research

- 6 Draw conclusions and make recommendations

- 7 Write the report

- 8 Disseminate the results

- Part 2 Methods

- Appendix The market for information professionals: A proposal from the Policy Studies Institute

6 - Draw conclusions and make recommendations

from Part 1 - The research process

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 09 June 2018

This is the point everything has been leading up to. Having carried out the research and marshalled all the evidence, you are now faced with the problem of making sense of it all. Here you need to distinguish clearly between three different things: results, conclusions and recommendations.

Results are what you have found through the research. They are more than just the raw data that you have collected. They are the processed findings of the work – what you have been analysing and striving to understand. In total, the results form the picture that you have uncovered through your research. Results are neutral. They clearly depend on the nature of the questions asked but, given a particular set of questions, the results should not be contentious – there should be no debate about whether or not 63 per cent of respondents said ‘yes’ to question 16.

When you consider the results you can draw conclusions based on them. These are less neutral as you are putting your interpretation on the results and thus introducing a degree of subjectivity. Some research is simply descriptive – the final report merely presents the results. In most cases, though, you will want to interpret them, saying what they mean for you – drawing conclusions.

These conclusions might arise from a comparison between your results and the findings of other studies. They will, almost certainly, be developed with reference to the aim and objectives of the research. While there will be no debate over the results, the conclusions could well be contentious. Someone else might interpret the results differently, arriving at different conclusions. For this reason you need to support your conclusions with structured, logical reasoning.

Having drawn your conclusions you can then make recommendations. These should flow from your conclusions. They are suggestions about action that might be taken by people or organizations in the light of the conclusions that you have drawn from the results of the research. Like the conclusions, the recommendations may be open to debate. You may feel that, on the basis of your conclusions, the organization you have been studying should do this, that or the other.

Access options

Save book to kindle.

To save this book to your Kindle, first ensure [email protected] is added to your Approved Personal Document E-mail List under your Personal Document Settings on the Manage Your Content and Devices page of your Amazon account. Then enter the ‘name’ part of your Kindle email address below. Find out more about saving to your Kindle .

Note you can select to save to either the @free.kindle.com or @kindle.com variations. ‘@free.kindle.com’ emails are free but can only be saved to your device when it is connected to wi-fi. ‘@kindle.com’ emails can be delivered even when you are not connected to wi-fi, but note that service fees apply.

Find out more about the Kindle Personal Document Service .

- Draw conclusions and make recommendations

- Book: How to Do Research

- Online publication: 09 June 2018

- Chapter DOI: https://doi.org/10.29085/9781856049825.007

Save book to Dropbox

To save content items to your account, please confirm that you agree to abide by our usage policies. If this is the first time you use this feature, you will be asked to authorise Cambridge Core to connect with your account. Find out more about saving content to Dropbox .

Save book to Google Drive

To save content items to your account, please confirm that you agree to abide by our usage policies. If this is the first time you use this feature, you will be asked to authorise Cambridge Core to connect with your account. Find out more about saving content to Google Drive .

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

Inductive Reasoning | Types, Examples, Explanation

Published on January 12, 2022 by Pritha Bhandari . Revised on June 22, 2023.

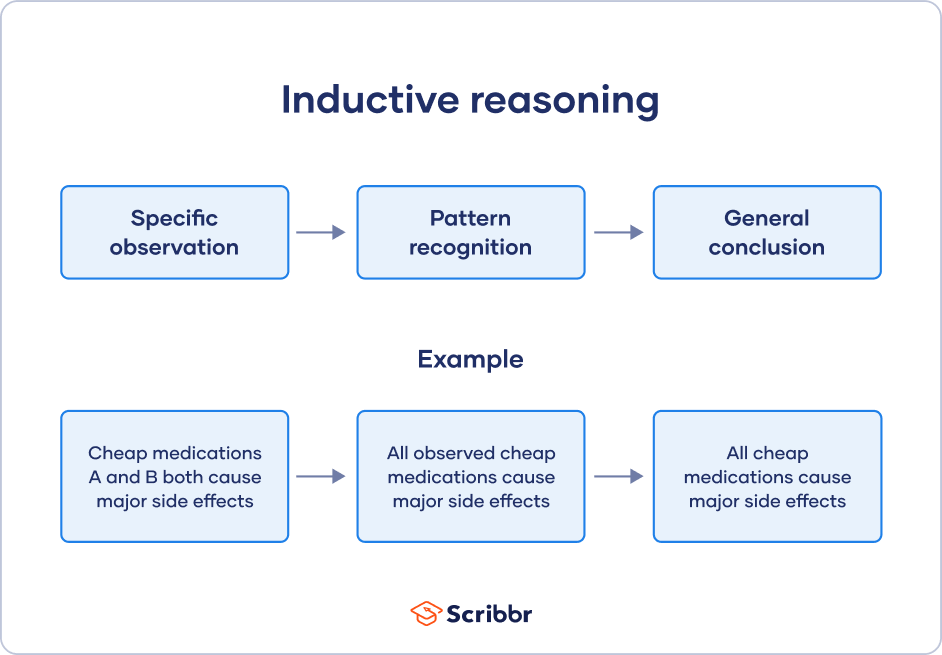

Inductive reasoning is a method of drawing conclusions by going from the specific to the general. It’s usually contrasted with deductive reasoning , where you go from general information to specific conclusions.

Inductive reasoning is also called inductive logic or bottom-up reasoning.

Note Inductive reasoning is often confused with deductive reasoning. However, in deductive reasoning, you make inferences by going from general premises to specific conclusions.

Table of contents

What is inductive reasoning, inductive reasoning in research, types of inductive reasoning, inductive generalization, statistical generalization, causal reasoning, sign reasoning, analogical reasoning, inductive vs. deductive reasoning, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about inductive reasoning.

Inductive reasoning is a logical approach to making inferences, or conclusions. People often use inductive reasoning informally in everyday situations.

You may have come across inductive logic examples that come in a set of three statements. These start with one specific observation, add a general pattern, and end with a conclusion.

| Stage | Example 1 | Example 2 |

|---|---|---|

| Specific observation | Nala is an orange cat and she purrs loudly. | Baby Jack said his first word at the age of 12 months. |

| Pattern recognition | Every orange cat I’ve met purrs loudly. | All babies say their first word at the age of 12 months. |

| General conclusion | All orange cats purr loudly. | All babies say their first word at the age of 12 months. |

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

In inductive research, you start by making observations or gathering data. Then , you take a broad view of your data and search for patterns. Finally, you make general conclusions that you might incorporate into theories.

You distribute a survey to pet owners. You ask about the type of animal they have and any behavioral changes they’ve noticed in their pets since they started working from home. These data make up your observations.

To analyze your data, you create a procedure to categorize the survey responses so you can pick up on repeated themes. You notice a pattern : most pets became more needy and clingy or agitated and aggressive.

Inductive reasoning is commonly linked to qualitative research , but both quantitative and qualitative research use a mix of different types of reasoning.

There are many different types of inductive reasoning that people use formally or informally, so we’ll cover just a few in this article:

Inductive reasoning generalizations can vary from weak to strong, depending on the number and quality of observations and arguments used.

Inductive generalizations use observations about a sample to come to a conclusion about the population it came from.

Inductive generalizations are also called induction by enumeration.

- The flamingos here are all pink.

- All flamingos I’ve ever seen are pink.

- All flamingos must be pink.

Inductive generalizations are evaluated using several criteria:

- Large sample: Your sample should be large for a solid set of observations.

- Random sampling: Probability sampling methods let you generalize your findings.

- Variety: Your observations should be externally valid .

- Counterevidence: Any observations that refute yours falsify your generalization.

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

Statistical generalizations use specific numbers to make statements about populations, while non-statistical generalizations aren’t as specific.

These generalizations are a subtype of inductive generalizations, and they’re also called statistical syllogisms.

Here’s an example of a statistical generalization contrasted with a non-statistical generalization.

| Specific observation | 73% of students from a sample in a local university prefer hybrid learning environments. | Most students from a sample in a local university prefer hybrid learning environments. |

|---|---|---|

| Inductive generalization | 73% of all students in the university prefer hybrid learning environments. | Most students in the university prefer hybrid learning environments. |

Causal reasoning means making cause-and-effect links between different things.

A causal reasoning statement often follows a standard setup:

- You start with a premise about a correlation (two events that co-occur).

- You put forward the specific direction of causality or refute any other direction.

- You conclude with a causal statement about the relationship between two things.

- All of my white clothes turn pink when I put a red cloth in the washing machine with them.

- My white clothes don’t turn pink when I wash them on their own.

- Putting colorful clothes with light colors causes the colors to run and stain the light-colored clothes.

Good causal inferences meet a couple of criteria:

- Direction: The direction of causality should be clear and unambiguous based on your observations.

- Strength: There’s ideally a strong relationship between the cause and the effect.

Sign reasoning involves making correlational connections between different things.

Using inductive reasoning, you infer a purely correlational relationship where nothing causes the other thing to occur. Instead, one event may act as a “sign” that another event will occur or is currently occurring.

- Every time Punxsutawney Phil casts a shadow on Groundhog Day, winter lasts six more weeks.

- Punxsutawney Phil doesn’t cause winter to be extended six more weeks.

- His shadow is a sign that we’ll have six more weeks of wintery weather.

It’s best to be careful when making correlational links between variables . Build your argument on strong evidence, and eliminate any confounding variables , or you may be on shaky ground.

Analogical reasoning means drawing conclusions about something based on its similarities to another thing. You first link two things together and then conclude that some attribute of one thing must also hold true for the other thing.

Analogical reasoning can be literal (closely similar) or figurative (abstract), but you’ll have a much stronger case when you use a literal comparison.

Analogical reasoning is also called comparison reasoning.

- Humans and laboratory rats are extremely similar biologically, sharing over 90% of their DNA.

- Lab rats show promising results when treated with a new drug for managing Parkinson’s disease.

- Therefore, humans will also show promising results when treated with the drug.

Inductive reasoning is a bottom-up approach, while deductive reasoning is top-down.

In deductive reasoning, you make inferences by going from general premises to specific conclusions. You start with a theory, and you might develop a hypothesis that you test empirically. You collect data from many observations and use a statistical test to come to a conclusion about your hypothesis.

Inductive research is usually exploratory in nature, because your generalizations help you develop theories. In contrast, deductive research is generally confirmatory.

Sometimes, both inductive and deductive approaches are combined within a single research study.

Inductive reasoning approach

You begin by using qualitative methods to explore the research topic, taking an inductive reasoning approach. You collect observations by interviewing workers on the subject and analyze the data to spot any patterns. Then, you develop a theory to test in a follow-up study.

Deductive reasoning approach

If you want to know more about statistics , methodology , or research bias , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Chi square goodness of fit test

- Degrees of freedom

- Null hypothesis

- Discourse analysis

- Control groups

- Mixed methods research

- Non-probability sampling

- Quantitative research

- Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Research bias

- Rosenthal effect

- Implicit bias

- Cognitive bias

- Selection bias

- Negativity bias

- Status quo bias

Inductive reasoning is a method of drawing conclusions by going from the specific to the general. It’s usually contrasted with deductive reasoning, where you proceed from general information to specific conclusions.

In inductive research , you start by making observations or gathering data. Then, you take a broad scan of your data and search for patterns. Finally, you make general conclusions that you might incorporate into theories.

Inductive reasoning takes you from the specific to the general, while in deductive reasoning, you make inferences by going from general premises to specific conclusions.

There are many different types of inductive reasoning that people use formally or informally.

Here are a few common types:

- Inductive generalization : You use observations about a sample to come to a conclusion about the population it came from.

- Statistical generalization: You use specific numbers about samples to make statements about populations.

- Causal reasoning: You make cause-and-effect links between different things.

- Sign reasoning: You make a conclusion about a correlational relationship between different things.

- Analogical reasoning: You make a conclusion about something based on its similarities to something else.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Bhandari, P. (2023, June 22). Inductive Reasoning | Types, Examples, Explanation. Scribbr. Retrieved July 1, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/inductive-reasoning/

Is this article helpful?

Pritha Bhandari

Other students also liked, inductive vs. deductive research approach | steps & examples, exploratory research | definition, guide, & examples, correlation vs. causation | difference, designs & examples, "i thought ai proofreading was useless but..".

I've been using Scribbr for years now and I know it's a service that won't disappoint. It does a good job spotting mistakes”

In order to continue enjoying our site, we ask that you confirm your identity as a human. Thank you very much for your cooperation.

- U.S. Locations

- UMGC Europe

- Learn Online

- Find Answers

- 855-655-8682

- Current Students

Online Guide to Writing and Research

The research process, explore more of umgc.

- Online Guide to Writing

Planning and Writing a Research Paper

Draw Conclusions

As a writer, you are presenting your viewpoint, opinions, evidence, etc. for others to review, so you must take on this task with maturity, courage and thoughtfulness. Remember, you are adding to the discourse community with every research paper that you write. This is a privilege and an opportunity to share your point of view with the world at large in an academic setting.

Because research generates further research, the conclusions you draw from your research are important. As a researcher, you depend on the integrity of the research that precedes your own efforts, and researchers depend on each other to draw valid conclusions.

To test the validity of your conclusions, you will have to review both the content of your paper and the way in which you arrived at the content. You may ask yourself questions, such as the ones presented below, to detect any weak areas in your paper, so you can then make those areas stronger. Notice that some of the questions relate to your process, others to your sources, and others to how you arrived at your conclusions.

Checklist for Evaluating Your Conclusions

| Checked | Questions |

| ✓ | Does the evidence in my paper evolve from a stated thesis or topic statement? |

| ✓ | Do all of my resources for evidence agree with each other? Are there conflicts, and have I identified them as conflicts? |

| ✓ | Have I offered enough evidence for every conclusion I have drawn? Are my conclusions based on empirical studies, expert testimony, or data, or all of these? |

| ✓ | Are all of my sources credible? Is anyone in my audience likely to challenge them? |

| ✓ | Have I presented circular reasoning or illogical conclusions? |

| ✓ | Am I confident that I have covered most of the major sources of information on my topic? If not, have I stated this as a limitation of my research? |

| ✓ | Have I discovered further areas for research and identified them in my paper? |

| ✓ | Have others to whom I have shown my paper perceived the validity of my conclusions? |

| ✓ | Are my conclusions strong? If not, what causes them to be weak? |

Key Takeaways

- Because research generates further research, the conclusions you draw from your research are important.

- To test the validity of your conclusions, you will have to review both the content of your paper and the way in which you arrived at the content.

Mailing Address: 3501 University Blvd. East, Adelphi, MD 20783 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License . © 2022 UMGC. All links to external sites were verified at the time of publication. UMGC is not responsible for the validity or integrity of information located at external sites.

Table of Contents: Online Guide to Writing

Chapter 1: College Writing

How Does College Writing Differ from Workplace Writing?

What Is College Writing?

Why So Much Emphasis on Writing?

Chapter 2: The Writing Process

Doing Exploratory Research

Getting from Notes to Your Draft

Introduction

Prewriting - Techniques to Get Started - Mining Your Intuition

Prewriting: Targeting Your Audience

Prewriting: Techniques to Get Started

Prewriting: Understanding Your Assignment

Rewriting: Being Your Own Critic

Rewriting: Creating a Revision Strategy

Rewriting: Getting Feedback

Rewriting: The Final Draft

Techniques to Get Started - Outlining

Techniques to Get Started - Using Systematic Techniques

Thesis Statement and Controlling Idea

Writing: Getting from Notes to Your Draft - Freewriting

Writing: Getting from Notes to Your Draft - Summarizing Your Ideas

Writing: Outlining What You Will Write

Chapter 3: Thinking Strategies

A Word About Style, Voice, and Tone

A Word About Style, Voice, and Tone: Style Through Vocabulary and Diction

Critical Strategies and Writing

Critical Strategies and Writing: Analysis

Critical Strategies and Writing: Evaluation

Critical Strategies and Writing: Persuasion

Critical Strategies and Writing: Synthesis

Developing a Paper Using Strategies

Kinds of Assignments You Will Write

Patterns for Presenting Information

Patterns for Presenting Information: Critiques

Patterns for Presenting Information: Discussing Raw Data

Patterns for Presenting Information: General-to-Specific Pattern

Patterns for Presenting Information: Problem-Cause-Solution Pattern

Patterns for Presenting Information: Specific-to-General Pattern

Patterns for Presenting Information: Summaries and Abstracts

Supporting with Research and Examples

Writing Essay Examinations

Writing Essay Examinations: Make Your Answer Relevant and Complete

Writing Essay Examinations: Organize Thinking Before Writing

Writing Essay Examinations: Read and Understand the Question

Chapter 4: The Research Process

Planning and Writing a Research Paper: Ask a Research Question

Planning and Writing a Research Paper: Cite Sources

Planning and Writing a Research Paper: Collect Evidence

Planning and Writing a Research Paper: Decide Your Point of View, or Role, for Your Research

Planning and Writing a Research Paper: Draw Conclusions

Planning and Writing a Research Paper: Find a Topic and Get an Overview

Planning and Writing a Research Paper: Manage Your Resources

Planning and Writing a Research Paper: Outline

Planning and Writing a Research Paper: Survey the Literature

Planning and Writing a Research Paper: Work Your Sources into Your Research Writing

Research Resources: Where Are Research Resources Found? - Human Resources

Research Resources: What Are Research Resources?

Research Resources: Where Are Research Resources Found?

Research Resources: Where Are Research Resources Found? - Electronic Resources

Research Resources: Where Are Research Resources Found? - Print Resources

Structuring the Research Paper: Formal Research Structure

Structuring the Research Paper: Informal Research Structure

The Nature of Research

The Research Assignment: How Should Research Sources Be Evaluated?

The Research Assignment: When Is Research Needed?

The Research Assignment: Why Perform Research?

Chapter 5: Academic Integrity

Academic Integrity

Giving Credit to Sources

Giving Credit to Sources: Copyright Laws

Giving Credit to Sources: Documentation

Giving Credit to Sources: Style Guides

Integrating Sources

Practicing Academic Integrity

Practicing Academic Integrity: Keeping Accurate Records

Practicing Academic Integrity: Managing Source Material

Practicing Academic Integrity: Managing Source Material - Paraphrasing Your Source

Practicing Academic Integrity: Managing Source Material - Quoting Your Source

Practicing Academic Integrity: Managing Source Material - Summarizing Your Sources

Types of Documentation

Types of Documentation: Bibliographies and Source Lists

Types of Documentation: Citing World Wide Web Sources

Types of Documentation: In-Text or Parenthetical Citations

Types of Documentation: In-Text or Parenthetical Citations - APA Style

Types of Documentation: In-Text or Parenthetical Citations - CSE/CBE Style

Types of Documentation: In-Text or Parenthetical Citations - Chicago Style

Types of Documentation: In-Text or Parenthetical Citations - MLA Style

Types of Documentation: Note Citations

Chapter 6: Using Library Resources

Finding Library Resources

Chapter 7: Assessing Your Writing

How Is Writing Graded?

How Is Writing Graded?: A General Assessment Tool

The Draft Stage

The Draft Stage: The First Draft

The Draft Stage: The Revision Process and the Final Draft

The Draft Stage: Using Feedback

The Research Stage

Using Assessment to Improve Your Writing

Chapter 8: Other Frequently Assigned Papers

Reviews and Reaction Papers: Article and Book Reviews

Reviews and Reaction Papers: Reaction Papers

Writing Arguments

Writing Arguments: Adapting the Argument Structure

Writing Arguments: Purposes of Argument

Writing Arguments: References to Consult for Writing Arguments

Writing Arguments: Steps to Writing an Argument - Anticipate Active Opposition

Writing Arguments: Steps to Writing an Argument - Determine Your Organization

Writing Arguments: Steps to Writing an Argument - Develop Your Argument

Writing Arguments: Steps to Writing an Argument - Introduce Your Argument

Writing Arguments: Steps to Writing an Argument - State Your Thesis or Proposition

Writing Arguments: Steps to Writing an Argument - Write Your Conclusion

Writing Arguments: Types of Argument

Appendix A: Books to Help Improve Your Writing

Dictionaries

General Style Manuals

Researching on the Internet

Special Style Manuals

Writing Handbooks

Appendix B: Collaborative Writing and Peer Reviewing

Collaborative Writing: Assignments to Accompany the Group Project

Collaborative Writing: Informal Progress Report

Collaborative Writing: Issues to Resolve

Collaborative Writing: Methodology

Collaborative Writing: Peer Evaluation

Collaborative Writing: Tasks of Collaborative Writing Group Members

Collaborative Writing: Writing Plan

General Introduction

Peer Reviewing

Appendix C: Developing an Improvement Plan

Working with Your Instructor’s Comments and Grades

Appendix D: Writing Plan and Project Schedule

Devising a Writing Project Plan and Schedule

Reviewing Your Plan with Others

By using our website you agree to our use of cookies. Learn more about how we use cookies by reading our Privacy Policy .

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

6 How do I Draw a Conclusion?

In drawing conclusions (making inferences), you are really getting at the ultimate meaning of things – what is important, why it is important, how one event influences another, and how one happening leads to another. Simply getting the facts in reading is not enough. You must think about what those facts mean to you.

- Review all the information stated about the person, setting, or event.

- Next, look for any facts or details that are not stated, but inferred.

- Analyze the information and decide on the next logical step or assumption.

- The reader comes up with a conclusion based on the situation.

College Reading & Writing: A Handbook for ENGL- 090/095 Students Copyright © by Yvonne Kane; Krista O'Brien; and Angela Wood. All Rights Reserved.

Share This Book

Drawing Conclusions

Drawing conclusions is an essential skill for comprehending fiction and informational texts. Passages with text-dependent questions, response activities, worksheets, and test prep pages provide practice through a variety of literary, science, and social studies topics at every grade level.

TRY US RISK-FREE FOR 30 DAYS!

ADD TO YOUR FILE CABINET

THIS RESOURCE IS IN PDF FORMAT

Printable Details

- Number of pages:

- Guided Reading Level:

- Common Core:

The power has been restored and the SLO Campus will reopen on June 5.

- Cuesta College Home

- Current Students

- Student Success Centers

Study Guides

- Reading Comprehension

- Inferences and Conclusions

Making Inferences and Drawing Conclusions

Read with purpose and meaning.

Drawing conclusions refers to information that is implied or inferred. This means that the information is never clearly stated.

Writers often tell you more than they say directly. They give you hints or clues that help you "read between the lines." Using these clues to give you a deeper understanding of your reading is called inferring . When you infer , you go beyond the surface details to see other meanings that the details suggest or imply (not stated). When the meanings of words are not stated clearly in the context of the text, they may be implied – that is, suggested or hinted at. When meanings are implied, you may infer them.

Inference is just a big word that means a conclusion or judgement . If you infer that something has happened, you do not see, hear, feel, smell, or taste the actual event. But from what you know, it makes sense to think that it has happened. You make inferences everyday. Most of the time you do so without thinking about it. Suppose you are sitting in your car stopped at a red signal light. You hear screeching tires, then a loud crash and breaking glass. You see nothing , but you infer that there has been a car accident. We all know the sounds of screeching tires and a crash. We know that these sounds almost always mean a car accident. But there could be some other reason, and therefore another explanation, for the sounds. Perhaps it was not an accident involving two moving vehicles. Maybe an angry driver rammed a parked car. Or maybe someone played the sound of a car crash from a recording. Making inferences means choosing the most likely explanation from the facts at hand.

There are several ways to help you draw conclusions from what an author may be implying. The following are descriptions of the various ways to aid you in reaching a conclusion.

General Sense

The meaning of a word may be implied by the general sense of its context, as the meaning of the word incarcerated is implied in the following sentence:

Murderers are usually incarcerated for longer periods of time than robbers.

You may infer the meaning of incarcerated by answering the question "What usually happens to those found guilty of murder or robbery?" What have you inferred as the meaning of the word incarcerated ?

If you answered that they are locked up in jail, prison, or a penitentiary, you correctly inferred the meaning of incarcerated .

When the meaning of the word is not implied by the general sense of its context, it may be implied by examples. For instance,

Those who enjoy belonging to clubs, going to parties, and inviting friends often to their homes for dinner are gregarious .

You may infer the meaning of gregarious by answering the question, "What word or words describe people who belong to clubs, go to parties a lot, and often invite friends over to their homes for dinner?" What have you inferred as the meaning of the word gregarious ?

If you answered social or something like: "people who enjoy the company of others", you correctly inferred the meaning of gregarious .

Antonyms and Contrasts

When the meaning of a word is not implied by the general sense of its context or by examples, it may be implied by an antonym or by a contrasting thought in a context. Antonyms are words that have opposite meanings, such as happy and sad. For instance,

Ben is fearless, but his brother is timorous .

You may infer the meaning of timorous by answering the question, "If Ben is fearless and Jim is very different from Ben with regard to fear, then what word describes Jim?"

If you answered a word such as timid , or afraid , or fearful , you inferred the meaning of timorous .

A contrast in the following sentence implies the meaning of credence :

Dad gave credence to my story, but Mom's reaction was one of total disbelief.

You may infer the meaning of credence by answering the question, "If Mom's reaction was disbelief and Dad's reaction was very different from Mom's, what was Dad's reaction?"

If you answered that Dad believed the story, you correctly inferred the meaning of credence; it means belief .

Be Careful of the Meaning You Infer!

When a sentence contains an unfamiliar word, it is sometimes possible to infer the general meaning of the sentence without inferring the exact meaning of the unknown word. For instance,

When we invite the Paulsons for dinner, they never invite us to their home for a meal; however, when we have the Browns to dinner, they always reciprocate .

In reading this sentence, some students infer that the Browns are more desirable dinner guests than the Paulsons without inferring the exact meaning of reciprocate . Other students conclude that the Browns differ from the Paulsons in that they do something in return when they are invited for dinner; these students conclude correctly that reciprocate means "to do something in return."

In drawing conclusions (making inferences), you are really getting at the ultimate meaning of things – what is important, why it is important, how one event influences another, how one happening leads to another.

Simply getting the facts in reading is not enough. You must think about what those facts mean to you.

- Uses of Critical Thinking

- Critically Evaluating the Logic and Validity of Information

- Recognizing Propaganda Techniques and Errors of Faulty Logic

- Developing the Ability to Analyze Historical and Contemporary Information

- Recognize and Value Various Viewpoints

- Appreciating the Complexities Involved in Decision-Making and Problem-Solving

- Being a Responsible Critical Thinker & Collaborating with Others

- Suggestions

- Read the Textbook

- When to Take Notes

- 10 Steps to Tests

- Studying for Exams

- Test-Taking Errors

- Test Anxiety

- Objective Tests

- Essay Tests

- The Reading Process

- Levels of Comprehension

- Strengthen Your Reading Comprehension

- Reading Rate

- How to Read a Textbook

- Organizational Patterns of a Paragraph

- Topics, Main Ideas, and Support

- Interpreting What You Read

- Concentrating and Remembering

- Converting Words into Pictures

- Spelling and the Dictionary

- Eight Essential Spelling Rules

- Exceptions to the Rules

- Motivation and Goal Setting

- Effective Studying

- Time Management

- Listening and Note-Taking

- Memory and Learning Styles

- Textbook Reading Strategies

- Memory Tips

- Test-Taking Strategies

- The First Step

- Study System

- Maximize Comprehension

- Different Reading Modes

- Paragraph Patterns

- An Effective Strategy

- Finding the Main Idea

- Read a Medical Text

- Read in the Sciences

- Read University Level

- Textbook Study Strategies

- The Origin of Words

- Using a Dictionary

- Interpreting a Dictionary Entry

- Structure Analysis

- Common Roots

- Word Relationships

- Using Word Relationships

- Context Clues

- The Importance of Reading

- Vocabulary Analogies

- Guide to Talking with Instructors

- Writing Help

Cuesta College Celebrates 59th Commencement Ceremony

Miossi art gallery presents annual student art showcase, cuesta college's book of the year presents acclaimed author myriam gurba, build your future.

Register for Summer and Fall

- Foundations

- Write Paper

Search form

- Experiments

- Anthropology

- Self-Esteem

- Social Anxiety

Drawing Conclusions

For any research project and any scientific discipline, drawing conclusions is the final, and most important, part of the process.

This article is a part of the guide:

- Null Hypothesis

- Research Hypothesis

- Defining a Research Problem

- Selecting Method

Browse Full Outline

- 1 Scientific Method

- 2.1.1 Null Hypothesis

- 2.1.2 Research Hypothesis

- 2.2 Prediction

- 2.3 Conceptual Variable

- 3.1 Operationalization

- 3.2 Selecting Method

- 3.3 Measurements

- 3.4 Scientific Observation

- 4.1 Empirical Evidence

- 5.1 Generalization

- 5.2 Errors in Conclusion

Whichever reasoning processes and research methods were used, the final conclusion is critical, determining success or failure. If an otherwise excellent experiment is summarized by a weak conclusion, the results will not be taken seriously.

Success or failure is not a measure of whether a hypothesis is accepted or refuted, because both results still advance scientific knowledge.

Failure lies in poor experimental design, or flaws in the reasoning processes, which invalidate the results. As long as the research process is robust and well designed, then the findings are sound, and the process of drawing conclusions begins.

The key is to establish what the results mean. How are they applied to the world?

What Has Been Learned?

Generally, a researcher will summarize what they believe has been learned from the research, and will try to assess the strength of the hypothesis.

Even if the null hypothesis is accepted, a strong conclusion will analyze why the results were not as predicted.

Theoretical physicist Wolfgang Pauli was known to have criticized another physicist’s work by saying, “it’s not only not right; it is not even wrong.”

While this is certainly a humorous put-down, it also points to the value of the null hypothesis in science, i.e. the value of being “wrong.” Both accepting or rejecting the null hypothesis provides useful information – it is only when the research provides no illumination on the phenomenon at all that it is truly a failure.

In observational research , with no hypothesis, the researcher will analyze the findings, and establish if any valuable new information has been uncovered. The conclusions from this type of research may well inspire the development of a new hypothesis for further experiments.

Generating Leads for Future Research

However, very few experiments give clear-cut results, and most research uncovers more questions than answers.

The researcher can use these to suggest interesting directions for further study. If, for example, the null hypothesis was accepted, there may still have been trends apparent within the results. These could form the basis of further study, or experimental refinement and redesign.

Question: Let’s say a researcher is interested in whether people who are ambidextrous (can write with either hand) are more likely to have ADHD. She may have three groups – left-handed, right-handed and ambidextrous, and ask each of them to complete an ADHD screening.

She hypothesizes that the ambidextrous people will in fact be more prone to symptoms of ADHD. While she doesn’t find a significant difference when she compares the mean scores of the groups, she does notice another trend: the ambidextrous people seem to score lower overall on tests of verbal acuity. She accepts the null hypothesis, but wishes to continue with her research. Can you think of a direction her research could take, given what she has already learnt?

Answer: She may decide to look more closely at that trend. She may design another experiment to isolate the variable of verbal acuity, by controlling for everything else. This may eventually help her arrive at a new hypothesis: ambidextrous people have lower verbal acuity.

Evaluating Flaws in the Research Process

The researcher will then evaluate any apparent problems with the experiment. This involves critically evaluating any weaknesses and errors in the design, which may have influenced the results .

Even strict, ' true experimental ,' designs have to make compromises, and the researcher must be thorough in pointing these out, justifying the methodology and reasoning.

For example, when drawing conclusions, the researcher may think that another causal effect influenced the results, and that this variable was not eliminated during the experimental process . A refined version of the experiment may help to achieve better results, if the new effect is included in the design process.

In the global warming example, the researcher might establish that carbon dioxide emission alone cannot be responsible for global warming. They may decide that another effect is contributing, so propose that methane may also be a factor in global warming. A new study would incorporate methane into the model.

What are the Benefits of the Research?

The next stage is to evaluate the advantages and benefits of the research.

In medicine and psychology, for example, the results may throw out a new way of treating a medical problem, so the advantages are obvious.

In some fields, certain kinds of research may not typically be seen as beneficial, regardless of the results obtained. Ideally, researchers will consider the implications of their research beforehand, as well as any ethical considerations. In fields such as psychology, social sciences or sociology, it’s important to think about who the research serves and what will ultimately be done with the results.

For example, the study regarding ambidexterity and verbal acuity may be interesting, but what would be the effect of accepting that hypothesis? Would it really benefit anyone to know that the ambidextrous are less likely to have a high verbal acuity?

However, all well-constructed research is useful, even if it only strengthens or supports a more tentative conclusion made by prior research.

Suggestions Based Upon the Conclusions

The final stage is the researcher's recommendations based on the results, depending on the field of study. This area of the research process is informed by the researcher's judgement, and will integrate previous studies.

For example, a researcher interested in schizophrenia may recommend a more effective treatment based on what has been learnt from a study. A physicist might propose that our picture of the structure of the atom should be changed. A researcher could make suggestions for refinement of the experimental design, or highlight interesting areas for further study. This final piece of the paper is the most critical, and pulls together all of the findings into a coherent agrument.

The area in a research paper that causes intense and heated debate amongst scientists is often when drawing conclusions .

Sharing and presenting findings to the scientific community is a vital part of the scientific process. It is here that the researcher justifies the research, synthesizes the results and offers them up for scrutiny by their peers.