Calcworkshop

Law of Syllogism & Detachment Explained w/ 19 Powerful Examples!

// Last Updated: January 21, 2020 - Watch Video //

In order to win a debate or an argument, you must have sound fact and reasoning as to why you are convinced you are right. It’s not enough to just believe you are right, you have to prove it.

Jenn, Founder Calcworkshop ® , 15+ Years Experience (Licensed & Certified Teacher)

Therein lies the difference between inductive reasoning and deductive reasoning.

Inductive vs Deductive Reasoning

Inductive reasoning uses patterns and observations to draw conclusions, and it’s much like making an educated guess.

Whereas, deductive reasoning uses facts, definitions and accepted properties and postulates in a logical order to draw appropriate conclusions.

Geometry Logic Statements

There are two laws of logic involved in deductive reasoning:

- Law of Detachment

- Law of Syllogism

To better understand these two ideas, let’s take a deeper look.

The Law of Detachment

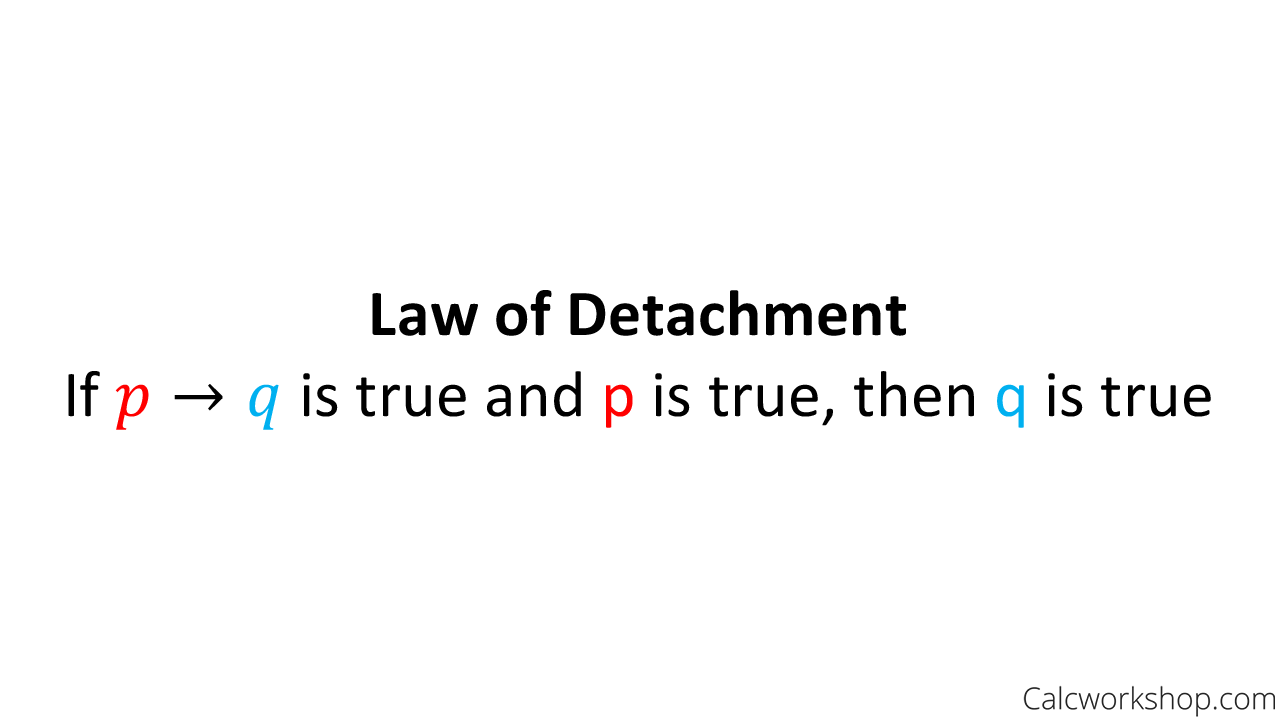

Law of Detachment Definition

If p equals q and p is also true. Then q is true.

If a bird is the largest of all birds then it is flightless. And if an ostrich is the largest living bird. Then an ostrich is flightless.

The Law of Syllogism

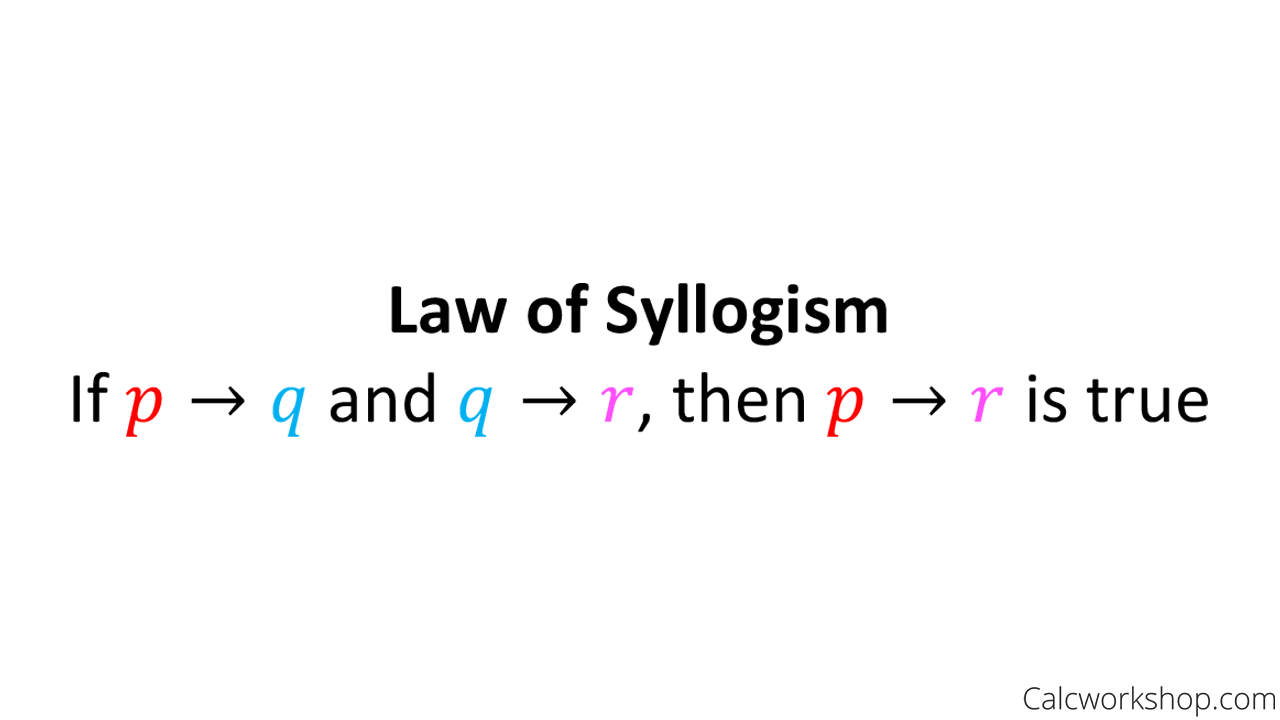

Law of Syllogism Definition

If p equals q and if q equals r, then p equals r.

If you wear school colors, then you have school spirit. If you have school spirit, then you feel great. If you wear school colors, then you feel great.

Using these two logic laws we are able to write conclusions and provide reasons for our statements using more than just intuition but sound fact.

Together we will look at countless examples of how to provide conclusions and reasons for such arguments as:

- Collinear Points

- Congruent Angles

- Angle Bisectors

And more importantly, deductive reasoning, is the way in which geometric proofs are written, as Spark Notes nicely states. Consequently, this lesson will introduce the framework for writing a two-column proof that will be used in subsequent lessons.

Deductive Reasoning – Lesson & Examples (Video)

- Introduction to deductive reasoning

- 00:00:25 – Overview of the laws of detachment and syllogism

- 00:05:09 – Use the law of detachment to determine if the statement is valid (Examples #1-2)

- 00:08:17 – Use the law of syllogism to write the statement that follows (Examples #3-5)

- Exclusive Content for Member’s Only

- 00:13:24 – Use logic to give a reason for each statement (Examples #6-11)

- 00:24:22 – Name the definition used for each conclusion (Examples #12-16)

- 00:30:46 – Draw a conclusion and name the definition used as the reason (Examples #17-19)

- Practice Problems with Step-by-Step Solutions

- Chapter Tests with Video Solutions

Get access to all the courses and over 450 HD videos with your subscription

Monthly and Yearly Plans Available

Get My Subscription Now

Still wondering if CalcWorkshop is right for you? Take a Tour and find out how a membership can take the struggle out of learning math.

Law of Syllogism

Imagine you are at the ticket counter of your favorite gaming store.

You are third in the queue.

Each transaction with a customer takes about 2 minutes.

You have only 10 minutes to get your ticket before the counter closes.

What can you infer from the above situation? Can you draw any conclusion?

You may be very happy that there is a fair chance that you can get your ticket.

While drawing this conclusion, you must have used the "Law of syllogism."

Those logical inferences that you draw are outcomes of the law of syllogism.

Even in a game of chess, you use several logical conclusions for taking the next steps in the game.

For example, if I defend my king what happens to the knight right up there!

Let us look at the law of syllogism in more detail and understand the definition of the law of syllogism and its examples in real life.

Lesson Plan

Law of syllogism in geometry, law of syllogism definition.

The word "Syllogism" has a Greek origin and it means deduction or inference.

Syllogism refers to drawing inferences from given prepositions or sentences.

The Law of Syllogism is actually a part of deductive reasoning where we arrive at conclusions by logical reasoning.

It is similar to the transitive property: if a = b and b= c, then a=c.

It is like a chain rule.

Law of Syllogism Example

Statement 1: If it is a Monday, I have school.

Statement 2: If I have school, I have my math class.

The conclusion that we can draw from the above two statements is, "If it is a Monday, then I have math class."

This law of syllogism is a wonderful tool for proving many mathematical statements, especially in geometry.

Structure of a Syllogism

In the rule of syllogism, there are three parts involved.

Each of these parts is called a conditional argument.

The hypothesis is the conditional statement that follows after the word if .

The inference follows after the word then .

To represent each phrase of the conditional statement, a letter is used.

The pattern looks like this:

Statement 1: If P, then Q.

Statement 2: If Q, then R.

Statement 3: If P, then R.

Statements 1 and 2 are called the premises of the given argument.

If they are true, then the correct inference must be statement 3.

Using the Law of Syllogism to Draw a Conclusion

Let us look at this geometry problem.

Draw a conclusion from the following true statements using the Law of Syllogism.

P: If a quadrilateral is a square, then it has four right angles.

Q: If a quadrilateral has four right angles, then it is a rectangle.

Here, statement P is true but statement Q is not true.

So, even though there is an immediate inference that a square is a rectangle, it is not valid as P is true, but not Q.

What Are the 3 Types Of Syllogisms?

Syllogisms are arguments usually with two statements (or premises).

Major premise: a point in general.

Minor premise: a particular argument.

The conclusion is based on both statements.

There are 3 main types of syllogisms. They are as follows.

Conditional Syllogism: If A is true, then B is true (If A, then B).

Categorical Syllogism: If A is in C, then B is in C.

Disjunctive Syllogism: If A is true, B is not true (A or B).

Now that we know what syllogism is about, let us try some examples to understand it better.

Choose the correct option using the law of syllogism:

Statement 1: All bats are mammals.

Statement 2: No birds are bats.

Conclusions:

a) No birds are mammals.

b) Some birds are not mammals.

c) No bats are birds.

d) All mammals are bats.

Solved Examples

Help John draw a conclusion using the law of syllogism.

Statement 1: If a number ends in 0, then it is divisible by 10.

Statement 2: If a number is divisible by 10, then it is divisible by 5.

Let P be the statement "The number ends in 0"; let Q be the statement "It is divisible by 10"; and let R be the statement "It is divisible by 5."

Then (1) and (2) can be re-written as:

1) If P, then Q.

2) If Q, then R.

Thus, by the Law of Syllogism, we can infer:

3) If P, then R.

That means, if a number ends in 0, then it is divisible by 5.

Draw a conclusion using the law of syllogism.

All bikes have wheels. I ride a bike.

This scenario belongs to a categorical syllogism.

Major Premise : All bikes have wheels.

Minor Premise : I ride a bike.

So, by the law of syllogism, we can conclude that my bike has wheels.

Noah had a conversation with his friend.

Noah: All bunnies are cute.

Friend: My cousin's pet is also cute.

Therefore, the pet is a bunny.

Do you think the conclusion is valid?

These statements do not fall in any specific category of syllogism, so there is a high chance that we may end up in fallacy.

Major Premise : All bunnies are cute.

Minor Premise : My cousin's pet is also cute.

Conclusion : The pet is a bunny.

Not every cute pet is a bunny.

Help Harry draw a conclusion using the law of syllogism.

\(\angle A\) and \(\angle C\) are equal. \(\angle B\) and \(\angle C\) are equal.

So, the statements can be considered as:

P: \(\angle A = \angle C\)

Q: \(\angle B = \angle C\)

R: \(\angle A = \angle B\)

So, by the Law of Syllogism, we can infer:

Thus, \(\angle A = \angle B = \angle C\)

- Choose the valid conclusion using the law of syllogism:

Statements:

- All technicians are villagers.

- No villager is a doctor.

- All doctors are managers.

- No technician is a manager.

- All villagers being managers is a possibility.

Interactive Questions

Let's summarize.

The mini-lesson targeted the fascinating concept of the law of syllogism. The math journey around the law of syllogism starts with what a student already knows, and goes on to creatively crafting a fresh concept in the young minds. Done in a way that not only it is relatable and easy to grasp, but also will stay with them forever. Here lies the magic with Cuemath.

About Cuemath

At Cuemath , our team of math experts is dedicated to making learning fun for our favorite readers, the students!

Through an interactive and engaging learning-teaching-learning approach, the teachers explore all angles of a topic.

Be it worksheets, online classes, doubt sessions, or any other form of relation, it’s the logical thinking and smart learning approach that we, at Cuemath, believe in.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. what is the law of detachment.

The law of detachment helps to arrive at a new valid conclusion from the given statements. 1) If P, then Q 2) P

By the Law of Detachment, we can conclude that Q is valid.

For example,

1) If you are a bird, then you live in a nest.

2) You are a bird.

Let P be the statement, "You are a bird"; let Q be the statement, "You live in a nest".

\(\therefore\) You live in a nest.

2. What is the Law of Contrapositive?

The negation and inversion of the original statement which conveys the same meaning is called the contrapositive.

Interchange the hypothesis and the conclusion of the inverse statement to form the contrapositive of the given statement.

The law of contraposition states that the given statement is valid if and only if its contrapositive is true.

3. What is the Law of Converse?

Interchange the hypothesis and the conclusion in order to form the converse of the given statement.

Statement: If two triangles are congruent, then their corresponding angles are equal.

Converse: If the corresponding angles of the two triangles are equal, then the triangles are congruent.

Note that, the converse of a statement need not hold good in every case.

4. What are the three types of syllogism?

5. what is the pattern of a syllogism.

In the rule of syllogism, there are three conditional arguments.

The hypothesis is the conditional statement that follows after the word if.

The inference follows after the word then.

The pattern looks like this:

Major Premise: If P, then Q.

Minor Premise: If Q, then R.

Conclusion: If P, then R.

6. What is the purpose of syllogism?

The law of syllogism is especially used in proving geometrical statements.

It is also used to derive logical conclusions from the given statements (or premises).

- Live one on one classroom and doubt clearing

- Practice worksheets in and after class for conceptual clarity

- Personalized curriculum to keep up with school

I. Definition

A syllogism is a systematic representation of a single logical inference . It has three parts: a major premise, a minor premise, and a conclusion. The parts are defined this way:

- The major premise contains a term from the predicate of the conclusion

- The minor premise contains a term from the subject of the conclusion

- The conclusion combines major and minor premise with a “therefore” symbol (∴)

When all the premises are true and the syllogism is correctly constructed, a syllogism is an ironclad logical argument .

II. Examples and Explanation

- All men are mortal (major premise)

- Socrates is a man (minor premise)

- ∴ Socrates is mortal (conclusion)

Notice that the major premise provides the predicate, while the minor premise provides the subject. As long as both premises are true, the conclusion must be true as well.

- Cats make good pets (major premise)

- Dogs and cats are equally good as pets (minor premise)

- ∴ dogs make good pets (conclusion)

Is this argument true? It depends! Some people might disagree with the premises, or with the conclusion. It’s a matter of opinion. However, the logical validity of the syllogism is not a matter of opinion, because the conclusion really does follow from the premises. That is, if the premises are true, then the conclusion must be true as well. That makes it a logically valid syllogism regardless of whether or not you agree with the premises or the conclusion!

- This car is expensive (minor premise)

- All expensive cars are Ferraris. (major premise)

- ∴ this car is a Ferrari. (conclusion)

The major premise in this syllogism, of course, is wrong. In terms of its logical structure, there’s nothing wrong with the syllogism. But it’s based on a faulty assumption, and therefore the argument doesn’t work. If the major premise were true, then the conclusion would follow, which means the syllogism is perfectly logical. It just so happens that the premise isn’t true.

III. The Importance of Syllogisms

Syllogisms represent the strongest form of logical argument, so if you could build an argument entirely out of syllogisms it would probably be very persuasive! Like triangles in architecture, the syllogism is the strongest logical structure. When formed correctly, they are indisputable in terms of their logical validity.

However, it’s important to remember what syllogisms don’t do: they don’t prove their own premises. So you could build an argument out of very strong syllogisms, but it wouldn’t work if its original premises weren’t correct. Thus, you have to ensure that the starting point of your argument is solid, or no amount of syllogisms will make the argument successful as a whole.

IV. How to Write a Syllogism

- Start with the conclusion. Most of the time, you’re writing a syllogism as a way of laying out the steps in your argument – steps you’ve already worked out in your head. So you can easily start with the conclusion. That’s the most important part of the syllogism, the part that you’re trying to prove through logic.

Example: Although most have live young, some mammals lay eggs.

- Break the conclusion down into subject and predicate . The grammar of your conclusion will dictate the logical structure of the syllogism you use to support it. So you have to be able to recognize subject and predicate in the sentence.

Although most have live young, some mammals (subject)

lay eggs (predicate)

- Locate the key terms . Take the subject and predicate, and boil them down to their key terms. Get rid of unnecessary adjectives and other extraneous words, and just focus on the word or words that carry the weight of the sentence.

mammals | lay eggs

- Craft your premises . Remember that the major premise will contain the key terms of the predicate, while the minor premise contains the key terms of the subject. Craft separate sentences around these key terms such that they fit together into a syllogism.

Echidnas are mammals (minor premise)

Echidnas lay eggs (major premise)

- Check whether the conclusion follows from the premises . Can you make a persuasive “if…then” statement using your premises to prove your conclusion? If not, the syllogism is not logically structured and will not work in your argument.

If echidnas are mammals AND echidnas lay eggs, then of course it follows that some mammals must lay eggs.

- Check whether the premises are persuasive. If you think the reader will accept both premises, and the syllogism is logically sound, then this step in your argument will be beyond criticism. However, bear in mind that a skeptical reader will often find ways to doubt your premises, so don’t take them for granted!

Echidnas are mammals (persuasive because of scientific consensus)

Echidnas lay eggs (persuasive because of empirical observation)

V. When to Use a Syllogism

Syllogisms are very abstract representations, and you rarely see them outside of formal logic and analytic philosophy . In other fields, it’s probably best not to write the syllogism out as part of your paper. However, it can still be very useful as a mental exercise! Even if you don’t end up showing the whole syllogism to your reader, you can write it out on scratch paper as a way of evaluating your own argument. If you can write your argument out in syllogism form, then you know it’s logical. If not, then there may be more work for you to do before the argument is ready for submission.

VII. Examples in Philosophy and Literature

- 60 men together can work 60 times as quickly as one man alone.

- One man alone can dig a whole in one minute.

- Therefore, 60 men can dig a whole in one second.

Each step in this syllogism seems to make sense, and the syllogism itself is logically sound. But the conclusion is clearly wrong! That’s because premise #1 is deceptive: in theory it’s true that 60 men can work 60 times as fast as one. But in practice things are not so simple, as Bierce’s clever example shows.

- Everything white is sweet

- Salt is white

- ∴ salt is sweet.

Clearly, premise #2 is wrong, and the conclusion is wrong as well. But if premise #2 were correct, then the conclusion would be correct as well. That means the syllogism is logically valid though factually incorrect

VIII. Examples in Popular Culture

- Women like men who buy [this brand of alcohol].

- You are a man and you want women to like you.

- Therefore, you should buy [this brand].

There are many potential problems with this argument, but the most obvious one is that it (probably) has at least one false premise: women probably don’t truly prefer men who purchase that particular brand. In addition, the viewer may well be a woman or a gay man, in which case the other premise is also false.

- “That’s a faulty syllogism. Just because you call Bill a dog doesn’t mean he is a dog.” (Dr. House, House )

In one episode of House , the title character refers to a “faulty syllogism” in a way that’s not entirely clear. But the syllogism he’s referring to looks like this:

- I call Bill a dog.

- Things are whatever I call them.

- ∴ Bill is a dog.

The syllogism is clearly faulty because premise #2 is false.

a. Major premise

b. Enthymeme

c. Conclusion

d. Minor premise

a. Its major premise is wrong

b. Its minor premise is wrong

c. Its conclusion is wrong

d. Any of the above

a. An entire argument

b. A single inference

c. An enthymeme

d. A faulty logical structure

a. Write out its major enthymeme

b. Use them to evaluate your argument

c. Write the outline of the syllogism

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

Margin Size

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

2.7: Deductive Reasoning

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 2147

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

Drawing conclusions from facts.

Deductive reasoning entails drawing conclusion from facts. When using deductive reasoning there are a few laws that are helpful to know.

Law of Detachment: If \(p\rightarrow q\) is true, and \(p\) is true, then \(q\) is true. See the example below.

Here are two true statements:

- If a number is odd (p), then it is the sum of an even and odd number (q).

- 5 is an odd number (a specific example of p) .

The conclusion must be that 5 is the sum of an even and an odd number (q).

Law of Contrapositive: If \(p\rightarrow q\) is true and \(\sim q\) is true, then you can conclude \(\sim p\). See the example below.

- If a student is in Geometry (\(p\)), then he or she has passed Algebra I (\(q\)).

- Daniel has not passed Algebra I (a specific example of \(\sim q\) ).

The conclusion must be that Daniel is not in Geometry ( \(\sim q\)) .

Law of Syllogism: If \(p\rightarrow q\) and \(q\rightarrow r\) are true, then \(p\rightarrow r\) is true. See the example below.

Here are three true statements:

- If Pete is late (\(p\)), Mark will be late (\(q\)).

- If Mark is late (\(q\)), Karl will be late (\(r\)).

- Pete is late (\(p\)).

Notice how each “then” becomes the next “if” in a chain of statements. If Pete is late, this starts a domino effect of lateness. Mark will be late and Karl will be late too. So, if Pete is late, then Karl will be late (\(r\)) , is the logical conclusion.

What if you were given a fact like "If you are late for class, you will get a detention"? What conclusions could you draw from this fact?

Example \(\PageIndex{1}\)

Suppose Bea makes the following statements, which are known to be true.

If Central High School wins today, they will go to the regional tournament. Central High School won today.

What is the logical conclusion?

These are true statements that we can take as facts. The conclusion is: Central High School will go to the regional tournament .

Example \(\PageIndex{2}\)

Here are two true statements.

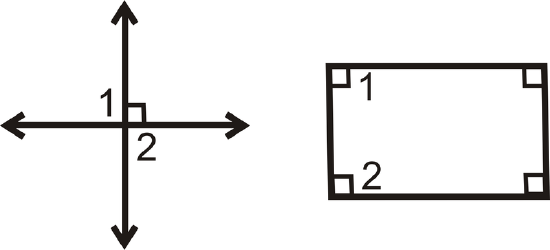

If \(\angle A\) and \(\angle B\) are a linear pair, then \(m\angle A+m\angle B=180^{\circ}\).

\(\angle ABC\) and \(\angle CBD\) are a linear pair .

What conclusion can you draw from this?

This is an example of the Law of Detachment, therefore:

\(m\angle ABC+m\angle CBD=180^{\circ}\)

Example \(\PageIndex{3}\)

Determine the conclusion from the true statements below.

Babies wear diapers.

My little brother does not wear diapers.

The second statement is the equivalent of \(\sim q\). Therefore, the conclusion is \(\sim p\), or: My little brother is not a baby .

Example \(\PageIndex{4}\)

\(m\angle 1=90^{\circ}\) and \(m\angle 2=90^{\circ}\).

What conclusion can you draw from these two statements?

Here there is NO conclusion. These statements are in the form:

\(p \rightarrow q\)

We cannot conclude that \(\angle 1\) and \(\angle 2\) are a linear pair.

Here are two counterexamples:

Example \(\PageIndex{5}\)

If you are not in Chicago, then you can’t be on the \(L\).

Sally is on the \(L\).

If we were to rewrite this symbolically, it would look like:

\(\sim p \rightarrow \sim q\)

Even though it looks a little different, this is an example of the Law of Contrapositive. Therefore, the logical conclusion is: Sally is in Chicago .

Determine the logical conclusion and state which law you used (Law of Detachment, Law of Contrapositive, or Law of Syllogism). If no conclusion can be drawn, write “no conclusion.”

- People who vote for Jane Wannabe are smart people. I voted for Jane Wannabe.

- If Rae is the driver today then Maria is the driver tomorrow. Ann is the driver today.

- All equiangular triangles are equilateral. \(\delta ABC\) is equiangular.

- If North wins, then West wins. If West wins, then East loses.

- If \(z>5\), then \(x>3\). If \(x>3\), then \(y>7\).

- If I am cold, then I wear a jacket. I am not wearing a jacket.

- If it is raining outside, then I need an umbrella. It is not raining outside.

- If a shape is a circle, then it never ends. If it never ends, then it never starts. If it never starts, then it doesn’t exist. If it doesn’t exist, then we don’t need to study it.

- If you text while driving, then you are unsafe. You are a safe driver.

- If you wear sunglasses, then it is sunny outside. You are wearing sunglasses.

- If you wear sunglasses, then it is sunny outside. It is cloudy.

- I will clean my room if my mom asks me to. I am not cleaning my room.

- Write the symbolic representation of #8. Include your conclusion. Does this argument make sense?

- Write the symbolic representation of #10. Include your conclusion.

- Write the symbolic representation of #11. Include your conclusion.

Additional Resources

Video: Types of Reasoning: Deductive Principles - Basic

Activities: Deductive Reasoning Discussion Questions

Study Aids: Types of Reasoning Study Guide

Practice: Deductive Reasoning

Real World: Deductive Reasoning

Syllogism Definition

What is a syllogism? Here’s a quick and simple definition:

A syllogism is a three-part logical argument, based on deductive reasoning, in which two premises are combined to arrive at a conclusion. So long as the premises of the syllogism are true and the syllogism is correctly structured, the conclusion will be true. An example of a syllogism is "All mammals are animals. All elephants are mammals. Therefore, all elephants are animals." In a syllogism, the more general premise is called the major premise ("All mammals are animals"). The more specific premise is called the minor premise ("All elephants are mammals"). The conclusion joins the logic of the two premises ("Therefore, all elephants are animals").

Some additional key details about syllogisms:

- First described by Aristotle in Prior Analytics , syllogisms have been studied throughout history and have become one of the most basic tools of logical reasoning and argumentation.

- Sometimes the word syllogism is used to refer generally to any argument that uses deductive reasoning.

- Although syllogisms can have more than three parts (and use more than two premises), it's much more common for them to have three parts (two premises and a conclusion). This entry only focuses on syllogisms with three parts.

Syllogism Pronunciation

Here's how to pronounce syllogism: sil -uh-jiz-um

Structure of Syllogisms

Syllogisms can be represented using the following three-line structure, in which A, B, and C stand for the different terms:

- All A are B.

- All C are A.

- Therefore, all C are B.

Another way of saying the same thing is as follows:

Notice how the "A" functions as a kind of "middle" for the other terms. You could, for instance, write the syllogism as: C = A = B, therefore C = B.

Types of Syllogism

Over the years, more than two dozen different variations of syllogisms have been identified. Most of them are pretty technical and obscure. But it's worth being familiar with the most common types of syllogisms.

Universal Syllogisms

Universal syllogisms are called "universal" because they use words that apply completely and totally, such as "no" and "none" or "all" and "only." The two most common forms of universal syllogisms are:

- All mammals are animals.

- All elephants are mammals.

- Therefore, all elephants are animals.

- No mammals are frogs.

- Therefore, no elephants are frogs.

Particular Syllogisms

Particular syllogisms use words like "some" or "most" instead of "all" or "none." Within this category, there are two main types:

- All elephants have big ears.

- Some animals are elephants.

- Therefore, some animals have big ears.

- No doctors are children.

- Some immature people are doctors.

- Therefore, some immature people are not children.

Enthymemes are logical arguments in which one or more of the premises is not explicitly stated, but is instead implied. Put another way: an enthymeme is a kind of abbreviated syllogism in which the writer presumes that the audience will accept the implied and unstated premise. For instance, the following statement is an enthymeme:

- "Socrates is mortal because he's human."

This enthymeme is an abbreviation of a famous syllogism:

- All humans are mortal.

- Socrates is human.

- Therefore Socrates is mortal.

The enthymeme leaves out the major premise. It instead assumes that all readers will understand and agree that "Socrates is mortal because he's human" without needing the explicit statement that "all humans are mortal."

Syllogistic Fallacies

A "fallacy" is the name for a mistake in logic. Syllogisms often seem like very simple statements, but you may be surprised how often people make logical mistakes when trying to put together simple syllogisms. For example, it may seem logical to make a statement like "Some A are B, and some C are A, therefore some C are B," such as:

- Some nice people are teachers.

- Some people with red hair are nice.

- Therefore, some teachers have red hair.

Each of these categorical propositions is, after all, true—but in fact the final proposition, while true in itself, is not the logical conclusion of the two preceding premises. In other words, the first two propositions, when combined, don't actually prove that the conclusion is true. So even though each statement is independently true, the "syllogism" above is actually a logical fallacy. Here's an example of a false syllogism whose logical fallacy is a bit easier to see.

- Some trees are tall things.

- Some tall things are buildings.

- Therefore, some trees are buildings.

The error in both of the above examples is called the "fallacy of the undistributed middle," since in each example the A is not "distributed" across the B and C in such a way that the B and C terms actually overlap. Other types of syllogistic fallacies exist, but this is by far the most common logical error people make with syllogisms.

Syllogism Examples

Syllogisms appear more often in rhetoric and logical argumentation than they do in literature, but the following are a few of the more memorable examples of the use of syllogism in literature.

Syllogism in Timon of Athens by Shakespeare

In this passage from a lesser-known work of Shakespeare, titled Timon of Athens, the character Flavius asks Timon whether he has forgotten him. Timon responds with a syllogism.

Flavius: Have you forgot me, sir? Timon: Why dost ask that? I have forgot all men; Then, if thou grant’st thou’rt a man, I have forgot thee.

So the structure of Timon's syllogism is as follows:

- All men are men that Timon has forgotten.

- Flavius is a man.

- Therefore, Flavius is a man that Timon has forgotten.

Syllogistic Fallacy in The Merchant of Venice by Shakespeare

In The Merchant of Venice , a beautiful, young woman named Portia is arranged to marry whomever can correctly guess which of three caskets contains her portrait: the gold, the silver, or the lead casket. A prince comes to solve the riddle, and thinks he has worked out the answer when he reads the following inscription on the gold casket:

“Who chooseth me shall gain what many men desire.”

Upon reading this inscription, the suitor immediately exclaims:

Why, that’s the lady. All the world desires her.

But he's mistaken; the gold casket does not contain the portrait of Portia. The suitor clearly thinks he has made a logical deduction using the structure of a syllogism:

- All men desire Portia;

- Many men desire what is in this chest;

- Therefore what is in the chest is (the portrait of) Portia.

But this "syllogism" is actually an example of the "fallacy of the undistributed middle," as we described above. In other words, it's the equivalent of saying "some trees are tall, and some buildings are tall, so therefore some buildings are trees."

Syllogism in "Elegy II" by John Donne

The following poem by John Donne contains a syllogism, though Donne takes some liberties with language in putting his syllogism together:

All love is wonder; if we justly do Account her wonderful, why not lovely too?

These lines could be translated into the structure of a syllogism like so:

- All love is wonder.

- She inspires wonder (or she is "wonderful").

- Therefore, she inspires love (or she is "lovely").

Syllogism in "To His Coy Mistress" by Andrew Marvell

If you look closely, you can see that this poem by Andre Marvell contains a subtle syllogism, scattered throughout the poem. Embedded in the beginning, middle, and end of the poem are the major premise , the minor premise , and the conclusion .

Had we but world enough and time, This coyness, lady, were no crime. We would sit down, and think which way To walk, and pass our long love’s day. Thou by the Indian Ganges’ side Shouldst rubies find; I by the tide Of Humber would complain. I would Love you ten years before the flood, And you should, if you please, refuse Till the conversion of the Jews. My vegetable love should grow Vaster than empires and more slow; An hundred years should go to praise Thine eyes, and on thy forehead gaze; Two hundred to adore each breast, But thirty thousand to the rest; An age at least to every part, And the last age should show your heart. For, lady, you deserve this state, Nor would I love at lower rate. But at my back I always hear Time’s wingèd chariot hurrying near; And yonder all before us lie Deserts of vast eternity. Thy beauty shall no more be found; Nor, in thy marble vault, shall sound My echoing song; then worms shall try That long-preserved virginity, And your quaint honour turn to dust, And into ashes all my lust; The grave’s a fine and private place, But none, I think, do there embrace. Now therefore, while the youthful hue Sits on thy skin like morning dew, And while thy willing soul transpires At every pore with instant fires, Now let us sport us while we may, And now, like amorous birds of prey, Rather at once our time devour Than languish in his slow-chapped power.

You might translate the above as follows:

- Being coy is fine so long as there's lots of time.

- There isn't any time. (I can hear "time's winged chariot" right behind me!)

- Therefore, don't be coy. (We should be amorous "while we may.")

Why Do Writers Use Syllogisms?

Writers use syllogisms because they're a useful tool for making an argument more convincing in persuasive writing and rhetoric. More specifically, writers might choose to use syllogism because:

- Using a syllogism can help make a logical argument sound indisputable, whether it's being used to illustrate a simple point or a complex one.

- Although syllogisms may seem somewhat tedious—since often they are just spelling out things that most people already know—it is helpful to clarify the terms and basic assumptions of an argument before proceeding with your main points.

- As shown in the Merchant of Venice example from above, even a false or poorly constructed syllogism can help make an ill-conceived argument sound airtight, since using the language and structure of logical argumentation can be very convincing even if the logic itself isn't sound.

Other Helpful Syllogism Resources

- The Wikipedia Page on Syllogism: A helpful, though technical resource if you want to learn more about the history of syllogisms, the many different types, and how the different ways they can be described using symbols.

- The Dictionary Definition of Syllogism: A basic definition, including a bit on the etymology: the root of the word is the Greek verb "to infer."

- To-the-point syllogism : An extremely to the point page on basic syllogisms and enthymeme.

- PDFs for all 136 Lit Terms we cover

- Downloads of 1929 LitCharts Lit Guides

- Teacher Editions for every Lit Guide

- Explanations and citation info for 40,694 quotes across 1929 books

- Downloadable (PDF) line-by-line translations of every Shakespeare play

- Figurative Language

- Slant Rhyme

- Deus Ex Machina

- Pathetic Fallacy

- Polysyndeton

- Characterization

- Juxtaposition

Become a math whiz with AI Tutoring, Practice Questions & more.

Law of Syllogism

In mathematical logic, the Law of Syllogism says that if the following two statements are true:

(1) If p , then q .

(2) If q , then r .

Then we can derive a third true statement:

(3) If p , then r .

If the following statements are true, use the Law of Syllogism to derive a new true statement.

1) If it snows today, then I will wear my gloves.

2) If I wear my gloves, my fingers will get itchy.

Let p be the statement "it snows today", let q be the statement "I wear my gloves", and let r be the statement "my fingers get itchy".

Then (1) and (2) can be written

1) If p , then q .

2) If q , then r .

So, by the Law of Syllogism, we can deduce

3) If p , then r

If it snows today, my fingers will get itchy.

- Asian Studies Tutors

- Series 32 Test Prep

- SAT Subject Test in Japanese with Listening Test Prep

- Virginia Bar Exam Test Prep

- SAT Subject Test in Chemistry Courses & Classes

- Series 16 Test Prep

- GMAT Tutors

- Writing Tutors

- Actuarial Exam IFM Courses & Classes

- CTRS - A Certified Therapeutic Recreation Specialist Test Prep

- 8th Grade Social Studies Tutors

- SBAC Tutors

- SE Exam - Professional Licensed Engineer Structural Engineering Exam Courses & Classes

- Pathophysiology Tutors

- IB Visual Arts SL Tutors

- Aragonese Tutors

- Series 51 Courses & Classes

- CCNA Cyber Ops - Cisco Certified Network Associate-Cyber Ops Test Prep

- Alaska Bar Exam Test Prep

- Cleveland Tutoring

- Oklahoma City Tutoring

- Raleigh-Durham Tutoring

- Columbus Tutoring

- Tulsa Tutoring

- San Diego Tutoring

- Albuquerque Tutoring

- Tucson Tutoring

- San Antonio Tutoring

- Philadelphia Tutoring

- LSAT Tutors in Seattle

- Biology Tutors in San Francisco-Bay Area

- LSAT Tutors in Washington DC

- Computer Science Tutors in Seattle

- Chemistry Tutors in Dallas Fort Worth

- Computer Science Tutors in San Francisco-Bay Area

- Physics Tutors in Miami

- SSAT Tutors in Miami

- Computer Science Tutors in Boston

- French Tutors in Miami

How Do You Use the Law of Detachment to Draw a Valid Conclusion?

See the Law of Detachment in action! This tutorial shows you an example that uses the Law of Detachment to make a conclusion.

- conditional statement

Further Exploration

Deductive reasoning.

What is the Law of Syllogism?

If you have related conditional statements, the Law of Syllogism can help you link those conditional statements into one conditional statement. In this tutorial, you'll see how to combine related conditional statements using the Law of Syllogism.

- Terms of Use

- PRO Courses Guides New Tech Help Pro Expert Videos About wikiHow Pro Upgrade Sign In

- EDIT Edit this Article

- EXPLORE Tech Help Pro About Us Random Article Quizzes Request a New Article Community Dashboard This Or That Game Popular Categories Arts and Entertainment Artwork Books Movies Computers and Electronics Computers Phone Skills Technology Hacks Health Men's Health Mental Health Women's Health Relationships Dating Love Relationship Issues Hobbies and Crafts Crafts Drawing Games Education & Communication Communication Skills Personal Development Studying Personal Care and Style Fashion Hair Care Personal Hygiene Youth Personal Care School Stuff Dating All Categories Arts and Entertainment Finance and Business Home and Garden Relationship Quizzes Cars & Other Vehicles Food and Entertaining Personal Care and Style Sports and Fitness Computers and Electronics Health Pets and Animals Travel Education & Communication Hobbies and Crafts Philosophy and Religion Work World Family Life Holidays and Traditions Relationships Youth

- Browse Articles

- Learn Something New

- Quizzes Hot

- This Or That Game

- Train Your Brain

- Explore More

- Support wikiHow

- About wikiHow

- Log in / Sign up

- Philosophy and Religion

How to Understand Syllogisms

Last Updated: March 7, 2024 Approved

This article was co-authored by wikiHow Staff . Our trained team of editors and researchers validate articles for accuracy and comprehensiveness. wikiHow's Content Management Team carefully monitors the work from our editorial staff to ensure that each article is backed by trusted research and meets our high quality standards. wikiHow marks an article as reader-approved once it receives enough positive feedback. In this case, several readers have written to tell us that this article was helpful to them, earning it our reader-approved status. This article has been viewed 573,617 times. Learn more...

A syllogism is a logical argument composed of three parts: the major premise, the minor premise, and the conclusion inferred from the premises. Syllogisms make statements that are generally true in a particular situation. In doing so, syllogisms often provide for both compelling literature and rhetoric, as well as irrefutable argumentation. [1] X Research source Syllogisms are an integral component of the formal study of logic, and are commonly featured in aptitude tests meant to assess logical reasoning abilities.

Familiarizing Yourself with the Vocabulary of Syllogisms

- Consider the conclusion of a syllogism to be the “thesis” of an argument. In other words, the conclusion is the point proven by the premises.

- Notice that the minor premise is more specific, and immediately relates to the major premise.

- If each of the prior statements are considered valid, the logical conclusion would be “David Foster Wallace is mortal.”

- Consider the example: “All birds are animals. Turkey vultures are bird. All turkey vultures are animals.”

- Here, “animal” is the major term, as it is in both the major premise and is the predicate of the conclusion.

- “Turkey vulture” is the minor term, as it is in the minor premise and is the subject of the conclusion.

- Notice that there is also a categorical term shared by the two premises, in this case “bird.” This is called the middle term, and is of immense importance in determining the figure of the syllogism, which is addressed in a later step.

- Another way to think of the logical sequence employed by categorical syllogisms is that they all employ the logical sequence of “Some/all/no _____ is/isn't ______.”

- In "All X are Y" propositions, the subject (X) is distributed.

- In "No X are Y" propositions, both the subject (X) and the predicate (Y) are distributed.

- In "Some X are Y" propositions, neither the subject nor the predicate are distributed.

- In "Some X are not Y" propositions, the predicate (Y) is distributed.

- In specific terms, enthymemes disregard the major premise and combine the minor premise with the conclusion.

- For instance, consider the syllogism: “All dogs are canine. Lola is a dog. Lola is a canine.” The enthymeme of this same logical sequence would be: “Lola is a canine because she's a dog.”

- Another example of an enthymeme is “David Foster Wallace is mortal because he is human.”

Identifying an Invalid Syllogism

- For instance, consider the syllogism: “All dogs can fly. Fido is a dog. Fido can fly.” This syllogism is logically valid, but since the major premise is untrue, the conclusion is clearly inaccurate and the syllogism is unsound.

- The structure of the argument made by a syllogism – the reasoning of the argument itself – is what you're assessing when assessing a syllogism for logical validity. When assessing soundness, you're assessing both its validity and the factual accuracy of its premises.

- Further, at least one of a syllogism's two premises must be affirmative, as no valid conclusion can follow from two negative premises. For example, "No pencils are cats, some cats are not pets, therefore some pets are not pencils" has true premises and a true conclusion, but is invalid because of its two negative premises. If transposed, it would reach the nonsensical conclusion that some pets are pencils.

- Further, at least one premise of a valid syllogism must contain a universal form. If both premises are particular, then no valid conclusion can follow. For example,“some cats are black" and "some black things are tables" are both particular propositions, so it cannot follow that "some cats are tables".

- You'll often simply know that a syllogism that breaks one of these rules is invalid without thinking about it, as it will likely sound illogical.

- For instance: “If you keep eating Jolly Ranchers every day, you're putting yourself at risk for diabetes. Sterling doesn't eat Jolly Ranchers every day. Sterling is not at risk for diabetes.”

- This syllogism is not valid for several reasons. Among them, Sterling may eat copious amounts of Jolly Ranchers several days a week – just not every day – which would still place him at risk for diabetes. Or, Sterling may eat cake every day, which would definitely place him at risk for diabetes.

- As another example: "All dogs love food" and "John loves food" does not logically indicate that "John is a dog." These are called fallacies of the undistributed middle, wherein a term that links the two phrases is never fully distributed.

- Beware of the fallacy of the illicit major, too. For instance, consider: "All cats are animals. No dogs are cats. No dogs are animals." This is invalid because the major term "animals" is undistributed in the major premise – not all animals are cats, but the conclusion relies on this insinuation.

- The same may be said of an illicit minor . For instance: "All cats are mammals. All cats are animals. All animals are mammals." This is invalid because, again, not all animals are cats, and the conclusion relies on this invalid insinuation.

Determining the Form and Figure of a Categorical Syllogism

- “A” propositions propose a universal affirmative, such as “all [categorical or specific term] are [a different categorical or specific term].” For example “All cats are felines.”

- “E” propositions propose exactly the opposite: a universal negative. For instance, “no [categorical of specific term] are [a different categorical or specific term].” More demonstratively, “No dogs are felines.”

- “I” propositions include a particular affirmative qualification in reference to one of the terms in the premise. For instance, “Some cats are black.”

- “O” propositions are the opposite, including a particular negative qualification. For instance, “Some cats are not black.”

- For instance, consider a categorical syllogism with the mood of AAA: “All X are Y. All Y are Z. So, all X are Z.

- A mood refers only to the types of propositions employed in a syllogism of standard order – major premise, minor premise, conclusion – and may be the same for two different forms based on the figure of the syllogisms in question.

- In a first figure syllogism, the middle term serves as subject in the major premise and predicate in the minor premise: "All birds are animals. All parrots are birds. All parrots are animals".

- In a second figure syllogism, the middle term serves as predicate in the major premise and predicate in the minor premise. For instance: "No foxes are birds. All parrots are birds. No parrots are foxes."

- In a third figure syllogism, the middle term serves as subject in the major premise and subject in the minor premise. For instance: "All birds are animals. All birds are mortals. Some mortals are animals."

- In a fourth figure syllogism, the middle term serves as predicate in the major premise and subject in the minor premise. For instance: "No birds are cows. All cows are animals. Some animals are not birds."

- For first figure syllogisms, the valid forms are AAA, EAE, AII, and EIO.

- For second figure syllogisms, the valid forms are EAE, AEE, EIO, and AOO.

- For third figure syllogisms, the valid forms are AAI, IAI, AII, EAO, OAO, and EIO.

- For fourth figure syllogisms, the valid forms are AAI, AEE, IAI, EAO, and EIO.

Community Q&A

You Might Also Like

- ↑ http://literarydevices.net/syllogism/

- ↑ https://owl.english.purdue.edu/owl/owlprint/659/

About This Article

To understand syllogisms, practice recognizing the major premise. An example of a major premise is “All humans are mortal.” Next, recognize the second part of the syllogism, the minor premise. An example of a minor premise is “David Foster Wallace is a human.” Finally, apply the premises to each other: if David is a human, then according to the major premise, David is also a mortal. You can then determine that the conclusion of the syllogism is “David Foster Wallace is mortal.” For more information on how to determine the validity of a syllogism, continue reading! Did this summary help you? Yes No

- Send fan mail to authors

Reader Success Stories

Elisha Eddie

Nov 24, 2017

Did this article help you?

Onesmo Joseph

Sep 10, 2016

Apr 13, 2016

Feb 18, 2019

Chris Hammer

Featured Articles

Trending Articles

Watch Articles

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Do Not Sell or Share My Info

- Not Selling Info

Get all the best how-tos!

Sign up for wikiHow's weekly email newsletter

- Mathematicians

- Math Lessons

- Square Roots

- Math Calculators

- Law of Detachment – Explanation and Examples

JUMP TO TOPIC

What Is the Law of Detachment?

Law of detachment examples, practice problems, law of detachment – explanation and examples.

The law of detachment states that if the antecedent of a true conditional statement is true, then the consequence of the conditional statement is also true.

This law regards the truth value of conditional statements.

Before moving on with this section, make sure to review conditional statements and the law of syllogism .

This section covers:

- What is the Law of Detachment?

The law of detachment states that if a conditional statement is true and its antecedent is true, then the consequence must also be true.

Recall that the antecedent is what follows the word “if” in a conditional statement. A consequence is what follows the word “then.”

Note that this does not work the other way unless the statement is biconditional. That is, if the consequence is true, it is impossible to conclude whether the antecedent is true or false.

Similarly, if the antecedent is false, that is not enough information to conclude that the consequence is true.

In mathematical logic, this fact is:

If “$P \rightarrow Q$ is true and $P$ is true, then $Q$ is true.

There are endless examples both in mathematics and beyond of the law of detachment.

One example is a coffee shop that gives a free drink to every 25th customer. As a conditional statement, this is “If someone is the 25th customer, then they get a free drink.”

Thus, if you are the 25th customer, you know you will get a free drink. Likewise, if your friend is the 25th customer, you know he will get a free drink.

Someone could get a free drink in another way. For example, they could have a coupon. Therefore, knowing someone got a free drink is not enough to conclude that they were the 25th customer. Likewise, if someone is not the 25th customer, that is not enough information to know that they did not get a free drink.

This section covers common examples of problems involving the law of detachment and their step-by-step solutions.

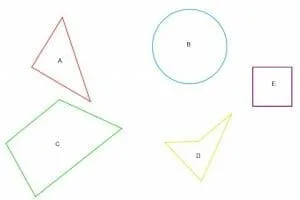

Suppose the following statement is true:

For every convex quadrilateral, the interior angles add up to $360^{\circ}$.

Which of the following figures can you conclude that the interior angles total $360^{\circ}$?

If a figure satisfies the antecedent, it must also satisfy the consequence.

The first two figures, A and B, are not quadrilaterals. Therefore, it is not possible to conclude that the sum of the interior angles to $360^{\circ}$ from the statement.

Figures C, D, and E are all quadrilaterals. Figure D, however, is not convex. Therefore, there is not enough information to make a conclusion.

Since figures C and E are both convex quadrilaterals, the law of detachment says the consequence of the conditional statement is true. Therefore, the total of their interior angles is $360^{\circ}$.

If it rains, then I will bring an umbrella.

Now consider separately that the following are also true. What can be concluded?

A. It is raining.

B. I will bring an umbrella.

Consider situation A first.

Since the antecedent of the true conditional statement is true, the consequence must also be true. Therefore, these two statements are enough to conclude that I will bring an umbrella.

In the second case, the statements “if it rains, then I will bring an umbrella” and “I will bring an umbrella” are both true.

In this case, the statement and its consequence are true. Unfortunately, this is not enough information to conclude that it is raining. In fact, no conclusions can be drawn from this information alone.

“It is a gizmo if and only if it is a widget.”

A. It is a gizmo.

B. It is a widget.

Note that in this case, the conditional statement is a biconditional statement. Recall that a biconditional statement is one for which $P \rightarrow Q$ and $Q \rightarrow P$ are both true.

Now, first, assume A.

In this case, the biconditional statement being true means that the statement “if it is a gizmo, then it is a widget” is true. Since “it is a gizmo” is the antecedent, and it is true, it is possible to conclude the consequence. Therefore, conclude that it is a widget.

Now, consider case B. Since the biconditional statement is true, the statement “if it is a widget, then it is a gizmo” is also true.

Since the antecedent of this true statement is true, the consequence must also be true. Therefore, it is possible to conclude that it is a gizmo.

Suppose that the following two statements are both true.

- “If it is a cat, then it is a feline.”

- “If it is a feline, then it is a mammal.”

Then, suppose separately that each of the following are true.

A. It is a mammal.

B. The animal is a feline.

C. It is a cat.

First, for A, assume that the three statements, “if it is a cat, then it is a feline,” “if it is a feline, then it is a mammal,” and “it is a mammal,” are all true. In this case, “it is a mammal” is the consequence of the second statement. Since it is not an antecedent, there is nothing to conclude.

For B, assume the statements “if it is a cat, then it is a feline,” “if it is a feline, then it is a mammal,” and “it is a feline” are true.

In this case, the first statement is extraneous. “It is a feline” is the antecedent of the second conditional statement. Since it is true and so is the antecedent, the consequence must also be true. Therefore, it is a mammal.

Finally, assume “if it is a cat, then it is a feline,” “if it is a feline, then it is a mammal,” and “it is a cat” are all true. Combining the first statement, “if it is a cat, then it is a feline,” with “it is a cat” is enough to conclude that “it is a feline is true.”

That is not all, however. In this case, it is also important to remember the law of syllogism. This states that if $P \rightarrow Q$ and $Q \rightarrow R$ are both true, then $P \rightarrow R$. Here, since “if it is a cat, then it is a feline” and “if it is a feline, then it is a mammal” are both true, “if it is a cat, then it is a mammal must be true.”

Therefore, since “it is a cat” is true, the consequence “it is a mammal” must also be true.

Use the law of syllogism and the law of detachment to draw conclusions if all of the following are true:

1. “If Dante fails his test, he will fail his class.”

2. “If Adventures in Space is on television, Dante will stay up to watch television.”

3. “Adventures in Space is on television.”

4. “If Dante fails his class, he will get in trouble with his parents.”

5. “If Dante stays up to watch television, then he will fail his test.”

The first step, in this case, is to put the statements in a more logical order so that it is easier to apply the law of syllogism.

Statement 3 is the only one that is not a conditional statement, so it should go at the end.

Statement 2 states that “if Adventures in Space is on television, Dante will stay up to watch television.” Since “Adventures in Space is on television” is not the consequence of any other statement, this one is likely first.

In fact, starting at statement 2, it is possible to make a string of statements where the consequence of one is the antecedent of the next.

Statement 2 $\rightarrow$ statement 5 $\rightarrow$ statement 1 $\rightarrow$ statement 4. Then, the end is statement 3.

Using the law of syllogism with the first four statements yields “if Adventures in Space is on television, he (Dante) will get in trouble with his parents.” Since each of the intermediary statements is true, this statement is true.

The antecedent of this statement, “Adventures in Space is on television,” is also true. Therefore, by the law of detachment, the conclusion of the statement, “Dante will get in trouble with his parents,” must also be true.

1. Suppose the following statement is true: “If a prime number is greater than two, then it is odd.” Which of the following are odd based on this statement? A. 2 B. 3 C. 5 D. 9 E. 10

2. Suppose the following is a true statement: “If it is October, then it is fall.” What can be concluded from the following? A. It is October 8 B. The date is September 29 C. It is fall

3. Let these statements be true: “If it is a carrot, it is a vegetable.” “It is a cabbage.” What can be concluded?

4. Suppose these statements are true: “$P \rightarrow Q$.” “$\neg Q$.” What can be concluded?

5. Suppose these statements are true: “If it is cheese, it contains dairy.” “If it contains dairy, Sonja cannot eat it.” “It is cheese.” What can be concluded?

- Only the numbers 3 and 5 because the number 9 is odd, but the statement doesn’t give enough information to conclude that.

- A means it is fall. Nothing can be concluded from B and C.

- Nothing can be concluded.

- By contrapositive, concluded $\neg P$.

- By the law of detachment, it is dairy. Because of this and the law of syllogism, Sonja cannot eat it.

Images/mathematical drawings are created with GeoGebra .

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Inductive reasoning uses patterns and observations to draw conclusions, and it's much like making an educated guess. Whereas, deductive reasoning uses facts, definitions and accepted properties and postulates in a logical order to draw appropriate conclusions. ... 00:08:17 - Use the law of syllogism to write the statement that follows ...

Then this three-sided polygon is a triangle. The law of syllogism provides for two conditional statements ("If …") followed by a conclusion ("Then …"). Logicians usually assign letters to these parts of the syllogism: Law of Syllogism Definition & Examples. Statement 1: If p, then q; Statement 2: If q, then r; Statement 3: If p, then r;

A syllogism is a form of logical reasoning. These syllogism examples show how different premises can lead to conclusions. Learn the six syllogism rules, too.

The law of syllogism provides its user with the power to connect three statements in the form of premise/ premise/ conclusion. Example 2: If you vote for me, then I can complete my projects. If I ...

Now, using the law of syllogism, the conclusion is "if it is a thing, then it is a gizmo." These conditional statements are nonsense, so it is impossible to determine whether they are true or false. Example 4. Use the law of syllogism to draw conclusions based on the following statements. A. If it is a flying elephant, then it has stripes ...

Using the Law of Syllogism to Draw a Conclusion. Let us look at this geometry problem. Draw a conclusion from the following true statements using the Law of Syllogism. P: If a quadrilateral is a square, then it has four right angles. Q: If a quadrilateral has four right angles, then it is a rectangle.

How to Write a Syllogism. Start with the conclusion. Most of the time, you're writing a syllogism as a way of laying out the steps in your argument - steps you've already worked out in your head. So you can easily start with the conclusion. That's the most important part of the syllogism, the part that you're trying to prove through ...

This is called the Law of Syllogism. The Law of Syllogism says that if p → q and q → r are true, then p → r is the logical conclusion. Typically, when there are more than two linked statements, we continue to use the next letter(s) in the alphabet to represent the next statement(s); r → s, s → t, and so on. Determining Conclusions . 1.

Using the Law of Syllogism Algebra Use the Law of Syllogism to draw a conclusion from the following true statements. If a number is prime, then it does not have repeated factors. If a number does not have repeated factors, then it is not a perfect square. You have two true conditionals where the conclusion of one is the hypothesis of

Our conclusion—remember, the law of syllogism, it's like the chain rule: "If p, then q. If q, then r. Therefore. . ."—let's see this conclusion here: "If p, then r." ... arguments here, two sentences, and I want you to use the law of syllogism to draw a valid conclusion. I'm going to move on to the next slide. Be sure to press pause and ...

2.7: Deductive Reasoning. Page ID. Drawing conclusions from facts. Deductive reasoning entails drawing conclusion from facts. When using deductive reasoning there are a few laws that are helpful to know. Law of Detachment: If p → q p → q is true, and p p is true, then q q is true. See the example below. Here are two true statements:

Here's a quick and simple definition: A syllogism is a three-part logical argument, based on deductive reasoning, in which two premises are combined to arrive at a conclusion. So long as the premises of the syllogism are true and the syllogism is correctly structured, the conclusion will be true. An example of a syllogism is "All mammals are ...

Your already know the following notion. A syllogism is called valid if the conclusion follows logically from the premises in the sense of Chapter 2: whatever we take the real predicates and objects to be: if the premises are true, the conclusion must be true. The syllogism is invalid otherwise. Here is an example of a valid syllogism:

In this video math tutorial we discuss what the law of detachment and law of syllogism are and how to recognize them. We also discuss a couple of examples a...

Learn how to work with the law of detachment and the law of syllogism in this free math video tutorial by Mario's Math Tutoring. We go through some examples ...

Welcome to today's video tutorial in which we are going to learn how to use the law of syllogism: formula, steps and examples.Don't forget... #OMG! Oh Math Gad!

Deduction is drawing a conclusion from something known or assumed. This is the type of reasoning we use in almost every step in a mathematical argument. Mathematical induction is a particular type of mathematical argument. It is most often used to prove general statements about the positive integers.

The Law of Syllogism in logic helps us draw conclusions from two given conditional statements. Conditional statements can be represented as "if p, then q." Examples include: "If it snows tomorrow, then class will be canceled." "If my grade is lower than 50%, then I''m going to fail." The Law of Syllogism connects two conditional statements when ...

In this tutorial, you'll see how to combine related conditional statements using the Law of Syllogism. Virtual Nerd's patent-pending tutorial system provides in-context information, hints, and links to supporting tutorials, synchronized with videos, each 3 to 7 minutes long. In this non-linear system, users are free to take whatever path ...

A syllogism (Greek: συλλογισμός, syllogismos, 'conclusion, inference') is a kind of logical argument that applies deductive reasoning to arrive at a conclusion based on two propositions that are asserted or assumed to be true. "Socrates" at the Louvre. In its earliest form (defined by Aristotle in his 350 BC book Prior Analytics), a deductive syllogism arises when two true premises ...

The conclusion then follows logically from the premises. Syllogistic reasoning plays a more-or-less explicit role in many academic and professional domains outside philosophy, including mathematics, science, and law among other fields. Syllogism example in law. Premise: Either the defendant should be convicted or there is reasonable doubt.

How to apply the law of syllogism in geometry is explained with examples in this video.

1. Recognize how a syllogism makes an argument. To understand syllogisms, you need to familiarize yourself with several terms often used when discussing formal logic. At the most basic level, a syllogism is the simplest sequence of a combination of logical premises that lead to a conclusion.

Use the law of syllogism and the law of detachment to draw conclusions if all of the following are true: 1. "If Dante fails his test, he will fail his class." 2. "If Adventures in Space is on television, Dante will stay up to watch television." 3. "Adventures in Space is on television." 4.

Delving into the logical structure of syllogisms can enhance your ability to dissect complex arguments. The key components include the major premise, minor premise, and conclusion.