How to Write a Monologue: Tips and Examples

Hello, dear readers. So you want to write a monologue? We assume that’s why you’re here. And you’re in the right place! In this article, you’ll learn all about what exactly a monologue is, its purpose in literature and media, and how to write your very own.

Tune in to learn the secrets behind a great monologue.

What Is a Monologue?

Firstly, what exactly is a monologue? And what is its purpose? There are different types of monologue that you may wish to know about before deciding which kind you will write. Let's dive in.

Definition of Monologue

A monologue is a lengthy, uninterrupted speech, spoken by a single character in theatre plays, novels, movies, television, or essentially, any media that uses actors. That is why, for the purposes of this article, we will use the terms ‘audience’, ‘listener’, ‘viewer’, and ‘reader’ interchangeably to refer to the intended audience of your monologue.

We’ll also use the terms ‘watch’, ‘listen’, and ‘read’ interchangeably, to refer to the concept of written material enjoyed in any format.

The word ‘monologue’ comes from the Greek words ‘monos’ and ‘logos’, meaning ‘alone’ and ‘speech’ respectively.

What is the Purpose of a Monologue?

Monologues tend to be used to give the audience more information about the story or the character’s thoughts, personality, or motivations. They give a glimpse into the character’s thought process when making a decision, which helps us, the audience, make sense of that decision.

A monologue also invites viewers, listeners, and readers into the speaker’s mind and gives them a glimpse of their true nature. Just in the same way, we can’t truly get to know someone unless they let us in on their innermost thoughts and, sometimes, secrets, our knowledge of a fictional character would remain limited if it weren’t for monologues giving us some insight.

Monologues can also be used to move the story forward. Indeed, telling part of a story through speech instead of scenes can save time and explain in more detail what has happened, in a way that imagery or dialogue couldn’t.

A monologue is also a great way to pack a lot of information into a scene, in a way that dialogue might not allow, due to the back and forth of the speech between characters and perhaps, at times, the unwillingness of the characters to reveal some information to one another.

Generally, the information given in a speech usually cannot be given in dialogue - at least not in the same way - and this is the reason why monologues exist. Remember this, as it will be important to take into consideration when you come to write your monologue, as we will come to explain in a later section.

Types of Monologue

Here are the following types of monologues:

A soliloquy is a type of monologue given by a character who assumes nobody is listening to them. They are speaking to themselves, rather than to another character or the audience.

Soliloquies give a privileged insight into a character’s thoughts, and can therefore be used to explain some of their choices, motivations, or actions.

Since the character delivering the soliloquy is unaware that anyone can hear them, they tend to reveal pretty personal and private information in these monologues. Of course, the audience can hear them, and sometimes another character might also be listening secretly.

The famous To Be Or Not To Be by William Shakespeare is an example of a soliloquy. Hamlet delivers this speech without intending for anyone to hear it. It’s a lament of his feelings.

Dramatic monologue

A dramatic monologue is quite the opposite of a soliloquy. Indeed, this type is a speech given by a character, with the intention of another character and/or the audience of hearing it.

When you watch the President’s speech on TV, for example, you are watching a dramatic monologue.

A character will usually deliver a dramatic monologue to reveal specific intentions.

Interior monologue

An interior monologue gives the audience access to the character’s stream of consciousness. The character is aware that the audience is listening, and they are delivering the speech to confess their thoughts and feelings to them, or to give the audience an essential part of information.

The difference is that, unlike a dramatic monologue, the character isn’t speaking directly to the audience.

They fill in the blanks and provide the reader, listener, or viewer with a clearer picture of what’s going on.

For example, you might hear an interior monologue in between scenes during a movie or a sitcom.

Fight Club is a great example of interior monologues. It is full of them throughout the movie, with Edward Norton as the narrator, giving us some insight into his thoughts, which, as it turns out, ends up playing an essential role in understanding the story. Without this ongoing interior monologue, the story wouldn't make sense.

Origins of Monologues

Drama as we know it evolved from Greek theatre, which started as long ago as 700 BC. Originally, it consisted mostly of monologues and did not contain much acting or dialogue between characters.

It evolved into more complex setups: now more characters were being added in to play out the storyline, and dialogues between characters were helping to carry the story forward. But even then, monologues were invaluable in helping transmit parts of the story to the audience.

Imagine, for example, having to relay to the audience that years have gone by, and the man has departed on his travels, and the woman in the meantime got pregnant unexpectedly. All of this on a small stage in 500 BC. Of course, this could also be done using signs or acting, but it would be much easier to explain with a monologue, don’t you think?

How to Write a Monologue

Are you ready to get onto the juicy bit? It’s time to write your own monologue. Whether you’re writing for a theatre play, a movie, a novel, a speech on TV, or any other medium, the following tips will help you in your endeavor.

Get Your Timing Right When You Write a Monologue

If you’re writing a monologue with the purpose of it being part of a bigger piece of writing, then timing is everything. If you don’t place it correctly, it could feel a little forced, or come across as fake to your audience. Or, quite simply, it might not deliver the dramatic effect you’d like it to.

You could place your monologue at the beginning or end of the scene or movie, or you could strategically place it at another crucial moment.

Thinking about your monologue’s purpose will help you decide the optimal time for your character to deliver their monologue.

A monologue at the beginning

Having a character deliver a monologue at the beginning of a scene, movie, act or chapter can help set the mood and tone for what’s to come. This can be useful if you want to implement a sudden change in tone, for example. Or if you want to introduce an unexpected side to a character.

Think of Henry Hill’s monologue at the start of Goodfellas. This iconic speech gives an introduction to one of the main characters, and immediate insight into his way of thinking, as well as his hopes and desires.

A monologue at the end

A monologue at the end of a scene helps summarize, emphasize the moral, or end on a particular note.

Think of Red’s parole monologue at the end of the immensely popular movie The Shawshank Redemption . It brings together the moral of the story by expressing the lessons Red has learned from his time in prison.

This monologue cleverly gives us insight into the meaning he has derived from his countless dialogues with other characters throughout the movie, as well as his experiences, all of which we have been witness to. This speech has a strong impact on the audience and leaves us feeling a particular way - as per the writer’s intentions.

A monologue as a transition

Monologues, as we have mentioned already, are a good way to mark a transition between two ideas. If you’re using a monologue for this purpose, then there aren’t any rules around where exactly you should place it. This comes down to your judgment.

Placement is still important. It is essential to place it somewhere that makes sense. Even more so if it’s a monologue serving as a transition since placing it in the middle of a scene can really interrupt the flow if it isn’t done naturally. Don’t get us wrong, you can have a monologue in the middle of a scene - if it makes sense.

Know Your Monologue’s Purpose

As has been mentioned earlier, a monologue must be used to do something a dialogue cannot. Otherwise, it will seem ill-placed and forced, and the audience will wonder why you’re using a monologue as opposed to another type of speech. So ask yourself, when your monologue is written - could this have been better communicated in a dialogue? If so, your monologue needs to be stronger.

A monologue can carry so much power. The best ones give us goosebumps as there are high stakes involved. Think of Buffy the Vampire Slayer delivering a long speech to her Scooby Gang about why they can defeat the big bad - even though this one is scarier and stronger than any other before.

Or take Sean Maguire’s speech about love and loss in the iconic Good Will Hunting. It is highly impactful - on the viewers, as well as Matt Damon’s character Will.

Another great monologue is Lester’s speech in American Beauty about how time stretches right before you die, which is delivered as he is about to die.

These monologues are notorious and will be remembered always, because of the emotions they elicited.

Be deliberate about your monologue’s purpose, and determine what it will be before you begin writing it. As discussed earlier, the purpose will also determine where it goes in your scene/movie if you are indeed writing one.

Knowing your monologue’s purpose will help it to fit seamlessly into the scene, and the overall evolution of the story will flow. It will also help you decide which type of monologue it should be - dramatic, soliloquy, or interior.

Give Your Monologue Structure

A clear beginning, middle, and end are essential parts of a monologue. You can almost think of a monologue as a standalone piece of writing. In fact, sometimes it is. Perhaps you’re here because you just want to write a monologue that will stand alone. In any case, the monologue should begin and end with a specific purpose.

Usually, the ending will be some sort of revelation on the speaker’s part. If the purpose of the monologue was for the character to have an internal struggle around which action to take, then the monologue might end with a decision.

If the monologue was telling a story about the character’s past, the end might explain how this impacts them today.

Choose the Right Length For Your Monologue

A monologue can be any length, as long as you follow the above rules. The length is less important than what the monologue is accomplishing and how well it is doing it. You could lose your reader/viewer within the first few sentences if the monologue is boring. Conversely, an enthralling and well-written monologue can keep the reader engaged for paragraphs or hours at a time (depending on the medium).

If your monologue is intended for an audiovisual medium, after writing it, it can be a good idea to perform it out loud the way you would like it to be performed by the actor - conveying the right emotions and taking the relevant pauses in speech. This is because a monologue can last for longer when spoken than it seems when being read in your head.

Of course, if you’re writing a monologue only, as opposed to a monologue that will fit into a broader picture (movie, book, etc.) then it’s likely to be somewhat longer since the entire performance rests on this monologue. Again, that isn’t a problem, it just raises the stakes in terms of keeping the listener engaged. Think about why they would want to listen to you if they don’t know anything about you/your character. And if they do know you, what more might they want to know?

Start to Write a Monologue With a Hook

You should spike the reader’s curiosity from the very beginning of the speech so that the listener will want to pay attention until the end. Here are a few ways you can do that.

- Use humor when you write a monologue: People love to laugh. Opening with humor is a great way to get people engaged and wanting more. Humor done well is usually a winner. If you’d like to know more about that, check out our recent article on writing comedy .

- Resonate with the audience: If they feel like you get them, your audience will be more than happy to stick around. Start with something they can resonate with.

- Inject an element of surprise: Try saying something a little controversial or challenging. The audience won’t expect it and they’ll be curious to see where you’re going. So make sure you are going somewhere with it.

- Get emotional: People like the idea that there’s something bigger at play. There’s always a way to make your topic tap into something larger than what it first appears to be.

What Makes a Good Monologue?

Now’s the time to edit and rewrite what needs to be improved upon. Remember, writing is a process. You aren’t expected to get it right the first time. Many drafts will be required, and that’s okay. Have fun with your monologue. Workshop it. Get ideas from friends.

Here are some tips to check if your monologue can hold its ground. You can use these tips to check in at different stages of your writing process, or when you’re done writing and are ready to make some tweaks.

Can it Stand Alone?

Ask yourself: if you take your monologue out of context, will it stand on its own pretty well? If the answer is yes, there’s a good chance your monologue is of high quality.

Since a monologue needs a clear beginning and end, as explained earlier, it can usually stand alone and make perfect sense.

Does it Add to the Story?

Despite being able to stand alone, within the intended context it adds fresh details to the story. So this is another element of a good quality monologue. It reveals something new to the audience.

Maybe it’s some juicy info that they didn’t know about a character. Maybe it raises the stakes. Maybe it makes the audience care more. Whatever it is, it grips the listener and keeps them hooked until the end of the monologue.

Character Profile and Character Development When You Write a Monologue

Your characters must act in a way the audience expects them to. Think of how a real person would act. Sure, we sometimes act out of character, but mostly we stick to a fairly unchangeable set of values and act in largely predictable ways. Your characters should do the same.

It can help to design character profiles, going into quite a lot of depth around their traits, thoughts, likes and dislikes, hobbies, and so on. Even if you don’t plan to use this information in your story directly, it can help you know your characters like your back pocket. And this in turn will help you write realistic monologues because they paint your character’s thoughts in a way that seems natural.

Even if their monologue is revealing something completely unexpected, the audience won’t question it so long as the character development was leading to this, or if they believe it’s possible in any way.

Does it Flow?

The best way to know if your monologue flows naturally is to perform it out loud. If you can, hire an actor to perform it. This will allow you to take the place of the audience and really listen . Does it grab your attention? Does the character behave in a way and use words that they would be expected to? Is the tone consistent throughout? Does the ending feel natural or is it a little abrupt? Is it long enough? Perhaps it feels too long and some elements can be cut.

There’s no better way for you to know how your monologue will come across to an audience than by putting yourself in the audience’s shoes. Of course, reading it out loud to another person will also help, as they will have the objectivity that you won’t, from hearing the piece for the first time.

How to Get Better at Writing Monologues

If you enjoyed the process of writing a monologue, you may want to write more. That’s great! If you want to get your creative juices flowing, monologues are a great choice because they are so rich and diverse, and there are many directions you can go with it.

It’s important to hone your craft and make sure that you’re improving your skills over time. Here is some advice for you to get better and better at writing monologues.

As they say, practice makes perfect. Keep writing, make it a daily practice. You can find time to write a little each day. Try using writing prompts - you can find these online, or in journals bought specifically for this purpose.

When you practice, you don’t have to practice only writing monologues. Just getting your creative juices flowing will help you. The more you tap into that side of your brain, the more it will become a habit, and the easier inspiration will come.

Speaking of inspiration, try to find it in mundane moments or objects. Pay attention to what’s around you and imagine writing a story about it.

Enjoy the Process When You Write a Monologue

Before, we said, “practice makes perfect”. Of course, there’s no such thing as perfection, especially in the world of creativity, since everyone’s taste is different and art is subjective.

Besides, we don’t recommend that you aim for perfection. Why? Because this will rob you of the joy of the process.

Writer Mark Ronson once said that he used to write with the anticipation of the piece being performed, always thinking ahead. Then when he got his piece to the stage and he was finally “there”, he had “made it”, he would realize that the most enjoyable part of the process was actually the writing.

Moral of the story is? Enjoy each stage when you’re in it. Don’t wish your time away. Don’t dwell on being imperfect or wondering how popular your piece of writing will be. That’s not the most important part. Because the truth is that when you find joy in your writing, this will be felt in your writing, as it will naturally improve.

Learn From the Pros

Watch, read, listen to and mimic the pros. What are they doing? Find out about their daily rituals, and their practices around writing, listen to their advice, and take in their tips.

This applies to writing monologues or writing in general.

You can buy books, watch Ted Talks, listen to podcasts, and take a course; the list of resources to help you improve your writing is endless. Head to reputable sites created by the people who have been there, who are doing it, who are living it, and listen to what they have to say. Learn from their expertise.

Expose Your Mind to Good Writing

There’s no better way to be exposed to good writing than to read good writing. Or watch well-written movies.

Pay attention to the dialogue. Study the writing and see if you can detect patterns. Read/watch the material over and over, join a study group, and dissect the whole thing. Not only is this loads of fun, but it will seriously help improve your writing.

Final Thoughts on How to Write a Monologue

So hopefully by now, you have the tools to write a strong monologue, so what are you waiting for? Get started! We believe in getting started before you feel ready, because the inspiration will come as you are writing, and practice makes perfect.

Remember, above all, to have a lot of fun with it. Having a goal for your monologue is valid, but it isn’t everything. Writing should be a fun and enjoyable process, so make sure not to omit that side of things, too.

Good luck writing your monologue!

Learn More:

- How to Write a Postcard (Tips and Examples)

- How to Write Comedy: Tips and Examples to Make People Laugh

- How to Write Like Ernest Hemingway

- How to Write a Follow-Up Email After an Interview

- How to Write a Formal Email

- 'Master's Student' or 'Masters Student' or 'MS Student': Which is Correct?

- How to Write Height Correctly - Writing Feet and Inches

- How Long Does It Take to Write 1000 Words

- How to Write an Inequality: From Number Lines or Word Problems

- How to Write a Letter to the President (With Example)

- How to Write a 2-Week Notice Email

- How to Write an Out-of-Office (OOO) Email

- How to Write a Professional ‘Thank You’ Email

- How to End an Email (Sign Off Examples)

- How to Sound Polite in Your Emails

We encourage you to share this article on Twitter and Facebook . Just click those two links - you'll see why.

It's important to share the news to spread the truth. Most people won't.

Add new comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Post Comment

Related Topics

- How to Write a Book

- Writing a Book for the First Time

- How to Write an Autobiography

- How Long Does it Take to Write a Book?

- Do You Underline Book Titles?

- Snowflake Method

- Book Title Generator

- How to Write Nonfiction Book

- How to Write a Children's Book

- How to Write a Memoir

- Mistakes to Avoid When Writing a Book

- How to Write a Book Title

- How to Write a Book Introduction

- How to Write a Dedication in a Book

- How to Write a Book Synopsis

- Author Overview

- Types of Writers

- How to Become a Writer

- Document Manager Overview

- Screenplay Writer Overview

- Technical Writer Career Path

- Technical Writer Interview Questions

- Technical Writer Salary

- Google Technical Writer Interview Questions

- How to Become a Technical Writer

- UX Writer Career Path

- Google UX Writer

- UX Writer vs Copywriter

- UX Writer Resume Examples

- UX Writer Interview Questions

- UX Writer Skills

- How to Become a UX Writer

- UX Writer Salary

- Google UX Writer Overview

- Google UX Writer Interview Questions

- Technical Writing Certifications

- Grant Writing Certifications

- UX Writing Certifications

- Proposal Writing Certifications

- Content Design Certifications

- Knowledge Management Certifications

- Medical Writing Certifications

- Grant Writing Classes

- Business Writing Courses

- Technical Writing Courses

- Content Design Overview

- Documentation Overview

- User Documentation

- Process Documentation

- Technical Documentation

- Software Documentation

- Knowledge Base Documentation

- Product Documentation

- Process Documentation Overview

- Process Documentation Templates

- Product Documentation Overview

- Software Documentation Overview

- Technical Documentation Overview

- User Documentation Overview

- Knowledge Management Overview

- Knowledge Base Overview

- Publishing on Amazon

- Amazon Authoring Page

- Self-Publishing on Amazon

- How to Publish

- How to Publish Your Own Book

- Document Management Software Overview

- Engineering Document Management Software

- Healthcare Document Management Software

- Financial Services Document Management Software

- Technical Documentation Software

- Knowledge Management Tools

- Knowledge Management Software

- HR Document Management Software

- Enterprise Document Management Software

- Knowledge Base Software

- Process Documentation Software

- Documentation Software

- Internal Knowledge Base Software

- Grammarly Premium Free Trial

- Grammarly for Word

- Scrivener Templates

- Scrivener Review

- How to Use Scrivener

- Ulysses vs Scrivener

- Character Development Templates

- Screenplay Format Templates

- Book Writing Templates

- API Writing Overview

- Business Writing Examples

- Business Writing Skills

- Types of Business Writing

- Dialogue Writing Overview

- Grant Writing Overview

- Medical Writing Overview

- How to Write a Novel

- How to Write a Thriller Novel

- How to Write a Fantasy Novel

- How to Start a Novel

- How Many Chapters in a Novel?

- Mistakes to Avoid When Writing a Novel

- Novel Ideas

- How to Plan a Novel

- How to Outline a Novel

- How to Write a Romance Novel

- Novel Structure

- How to Write a Mystery Novel

- Novel vs Book

- Round Character

- Flat Character

- How to Create a Character Profile

- Nanowrimo Overview

- How to Write 50,000 Words for Nanowrimo

- Camp Nanowrimo

- Nanowrimo YWP

- Nanowrimo Mistakes to Avoid

- Proposal Writing Overview

- Screenplay Overview

- How to Write a Screenplay

- Screenplay vs Script

- How to Structure a Screenplay

- How to Write a Screenplay Outline

- How to Format a Screenplay

- How to Write a Fight Scene

- How to Write Action Scenes

- How to Write a Monologue

- Short Story Writing Overview

- Technical Writing Overview

- UX Writing Overview

- Reddit Writing Prompts

- Romance Writing Prompts

- Flash Fiction Story Prompts

- Dialogue and Screenplay Writing Prompts

- Poetry Writing Prompts

- Tumblr Writing Prompts

- Creative Writing Prompts for Kids

- Creative Writing Prompts for Adults

- Fantasy Writing Prompts

- Horror Writing Prompts

- Book Writing Software

- Novel Writing Software

- Screenwriting Software

- ProWriting Aid

- Writing Tools

- Literature and Latte

- Hemingway App

- Final Draft

- Writing Apps

- Grammarly Premium

- Wattpad Inbox

- Microsoft OneNote

- Google Keep App

- Technical Writing Services

- Business Writing Services

- Content Writing Services

- Grant Writing Services

- SOP Writing Services

- Script Writing Services

- Proposal Writing Services

- Hire a Blog Writer

- Hire a Freelance Writer

- Hire a Proposal Writer

- Hire a Memoir Writer

- Hire a Speech Writer

- Hire a Business Plan Writer

- Hire a Script Writer

- Hire a Legal Writer

- Hire a Grant Writer

- Hire a Technical Writer

- Hire a Book Writer

- Hire a Ghost Writer

Home » Blog » How to Write a Monologue in 7 Simple Steps

How to Write a Monologue in 7 Simple Steps

TABLE OF CONTENTS

There was a time when monologues were used in theatres but things are different now. Monologues are used in books, movies, novels , science fiction , TV series, and pretty much everywhere.

Writing a monologue needs creativity and a systematic approach. You can’t just start writing a good monologue without a plan. A poorly written monologue will bore readers, they might lose interest, or they might skip the monologue outright. In any case, it’s a big loss as a writer if you fail to connect with your readers at any stage.

A great writer makes readers read every single word – not just once – but multiple times.

If you are new to monologue writing and have little or no idea of where to begin, what to include, and how to write a monologue, this actionable step-by-step guide is your best bet.

How to Write a Monologue: Step-By-Step Guide

Writing a monologue doesn’t just require practice but it needs a systematic approach. You can’t just write anything and name it as a dramatic monologue, and expect your audience to make sense of it.

If you are new to monologue writing, the following 7-step guide to writing a powerful monologue will help you master the art.

Step #1: Define the Purpose of the Monologue

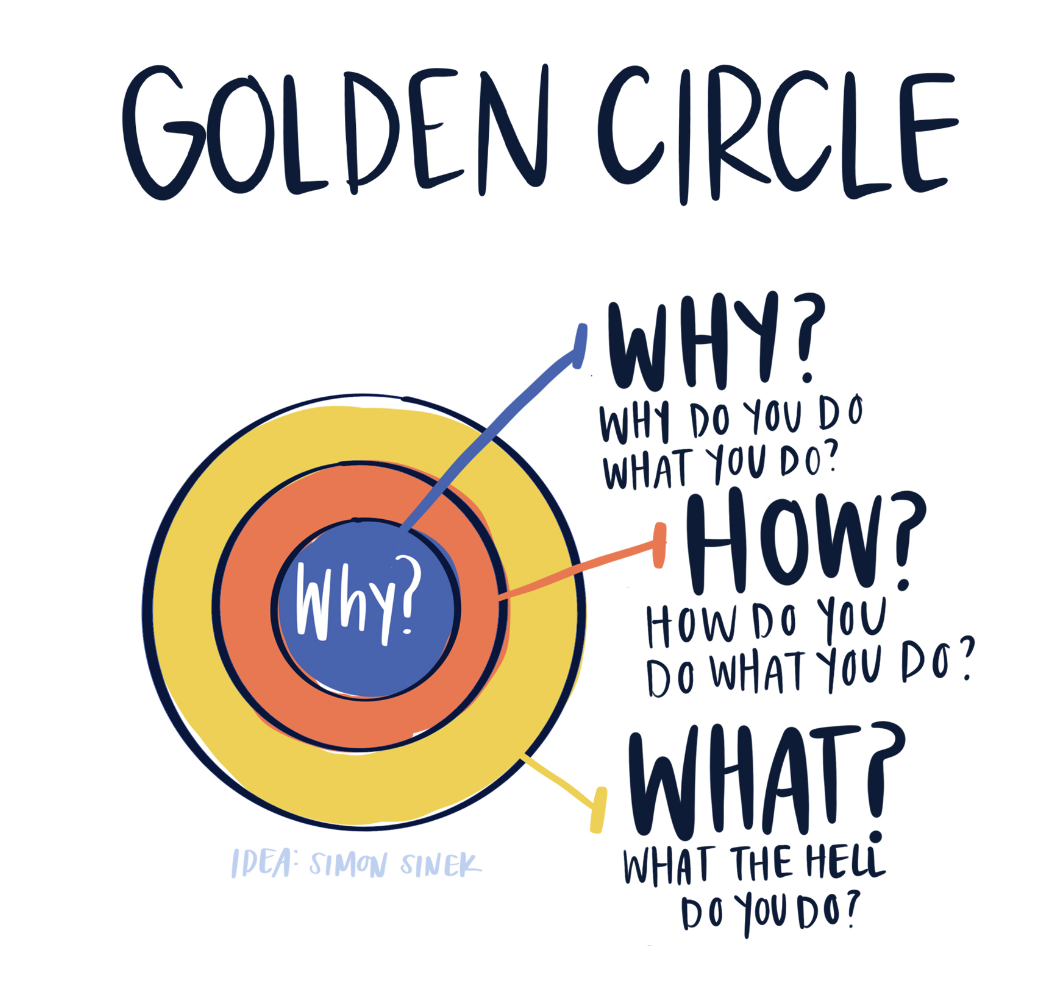

You don’t have to add a monologue to your story just for the sake of it rather you must have a clear purpose and objective that you wish to achieve with the help of a monologue. Remember the following golden circle :

Ask yourself: Why, how, and what of the monologue to clearly define its purpose.

For example, you can use monologue to reveal a secret. Writers use monologues to express a character’s true emotions or thoughts that are, otherwise, hard to express via dialogues. Whenever you find it hard to communicate with the readers via dialogue, you must consider using a monologue.

Defining the purpose of the monologue is the first and most crucial step in the writing process. You can use monologue for a wide range of purposes such as:

- Emotional release by a character

- Revealing a secret

- Answering questions related to the storyline or character

- Sharing feelings and thoughts of a character

- Communicating with the readers

Ideally, you need to make sure you are using monologue to either let a weak character express his/her views or have one of the main characters speak aloud.

Step #2: Develop Character Profile

Character development is a must. When you decide to write a monologue and you have set its purpose, you know the character already. You now need to set up the complete character profile to ensure the speech is delivered appropriately.

Remember, monologue is different. It has to be powerful, attention-grabbing, and interesting so that the audience doesn’t lose interest. You don’t just have to focus on the speech and its words rather the actor or character delivering it must be worked upon too.

Building a character profile that matches the monologue is essential. Here is a list of the major things to consider for profiling:

- Speaking style

- Character’s voice

- Tone and pitch

- Facial expressions

- Body language

- Emotions and feelings

And other details you think are necessary. Check out this 12-step guide to creating a powerful character profile .

Most of these details might not appear in the story but these are necessary as it helps you craft a better monologue. For example, the tone, pitch, and speaking style might not be visible in the book, however, when you set these upfront, you’ll be able to use words, sentences, terms, and phrases that help you deliver the tone, pitch, and style.

Character development and profiling specifically for an effective monologue are essential to keep it natural and meaningful.

Use Squibler to write your monologue and store your character, their details , dialogue , and descriptions so that you keep the characters constant throughout the story as you want them to be. You can always invoke the details by just writing the character’s name when writing your monologues with it.

Step #3: Identify the Audience

The audience refers to the people your character will be addressing. The audience is the target of your character’s monologue . If your character is addressing himself/herself, the audience in this case will be the character himself/herself.

When writing a good monologue, make sure you have a target audience identified. It will help you write a better monologue. Avoid writing your monologue without any specific audience.

For example, if there is a character expressing his feelings for another character, decide if the other character must be present or if the monologue will be delivered in his/her absence.

These petty details are always in your mind as a writer, but it is essential to write them down so that you can avoid assumptions while writing a monologue. Just because you know the audience of the monologue doesn’t mean readers will know it too.

Use Squibler’s smart writer to develop and extend the monologue. You can provide manual instructions about your intended audience, the type of conversation, and the plot to the AI tool and it will generate content within seconds for you according to your needs.

Step #4: Craft a Powerful Beginning

Now is the time to start writing the monologue. A monologue has three distinct parts: Beginning, middle, and end.

The beginning of the monologue must be powerful, and intriguing, and it must be attention-grabbing.

The first must line sets the stage for a secret and the second line further tells the readers what they must expect from the monologue.

The beginning should set the tone and mood of the monologue so it must be crafted carefully. The best approach is to write an outline for the entire monologue and then craft a beginning according to the outline.

Here are a few tips on writing an attention-grabbing beginning for your monologue:

- Stick with the purpose of your monologue and make sure the beginning adheres to the purpose

- The first line must be the best

- Start the monologue with a secret, fact, joke, or deep emotion to hook the readers

- One of the basic approaches to writing a killer monologue introduction is to begin it with the most crucial sentence (the crux of the monologue), and then explain it throughout the monologue

- Define the character and the need for the monologue. Why a speech is needed in the first place?

- Set the tone and mood by using the right words, expressions, attire, and scene.

One of the key features of writing a monologue is to use software that you are comfortable with. Using a monologue writing software saves you from a lot of issues such as formatting and organization of ideas.

Squibler , for instance, is the best AI writing app that provides you with an AI smart writer, multiple templates, and outlines that save you from the pain of doing everything from scratch. You can use an existing template and instruct the Smart Writer to generate engaging and relevant content for. Consider using a writing app so you can focus on writing instead of formatting, organizing, template, and outlining, and what’s better than using an AI one where you don’t even have to write by yourself?

Step #5: Write the Middle Part

As a writer, I’m sure you the importance of creating conflict and resolving it. The best technique to write the middle section of your interior monologue is to use conflict and climax to make it work.

This is the crux of the monologue where you have to explain everything by building your case. One of the most common ways to write a monologue is to build past-present interaction. The character, in this case, refers to past feelings and emotions and connects them to present and/or future events, actions, or thoughts.

Here is an overview of the important things to consider when writing the mid-section of a monologue:

- Use conflict to build reader interest as it works best for monologue writing. Focus on the word choice.

- Build the speech in a way that leads to the climax. Use an interconnected series of actions, words, and feelings that lead to the climax or a decisive action.

- An important revelation about the character that’s alien to the readers and other characters is often the best way to use a climax in a monologue.

- The secret (or climax) must be related to the plot and the rest of the story. It must not be an isolated climax that doesn’t impact the plot.

- Create suspense as it will keep readers hooked. Since a monologue is a speech by one character, readers might likely get bored if it lacks suspense or climax. Develop suspense with a plot twist.

The middle part of the monologue is where you need to present everything. It must be well-written and must connect with the readers emotionally. Not to forget, it must fulfill the purpose of the monologue.

If you feel stuck with adding the details and conflict, Squibler’s smart writer takes the lead. You can instruct the tool about the context, plot, and intensity you want to add, and it will generate conflict-rich intense content around your plot. If you don’t like some segment, don’t worry, you can always edit it.

Step #6: Craft a Clear Ending

A monologue without a proper ending is a rare scene. The end of the scene or the monologue must be clear, sound, and logical. It needs to give something new to the readers in the shape of a climax or a plot twist.

There are several important considerations for the ending including:

- It needs to conclude the monologue with a very strong point

- The ending must justify the purpose of the monologue

- It must end with something new preferably something that readers don’t expect at all

- The ending must show readers how the story will move forward from this point.

When you are done with the ending, you’ll have a clear view of the full monologue. This is a good time to revisit your entire monologue and see if it fits well in the story.

Step #7: Refine and Tweak

Finally, you are all set to refine, proofread, and edit your monologue. Refining your monologue is important because it is a long speech that might make readers bored. Unlike interactive dialogues, a monologue needs special attention as it’s not interactive.

Follow these advanced techniques to refine and polish your monologue:

- Read it and see how well it fits in the overall story

- See if it meets the objective and does it conveys the same message that you wanted to deliver

- Have a few experts read the monologue for improvements and suggestions

- The monologue must be short so try removing words, phrases, and weak sentences

- Keep it simple by breaking lengthy complex sentences into short phrases.

The issue of polishing and refining is taken care of by the writing app if you are using one. When you are using a monologue writing app , you’ll have a set template and outline to follow that saves you from refining your work.

What is a Monologue?

A monologue is a speech (usually long) by a single character in a film, book, novel, or story. It can be used for varied purposes such as to share a character’s viewpoints or to explain something to the readers (or audience).

Monologues originated from theatres where a character used to make a long speech to address the audience to share thoughts. But monologues aren’t limited to theatres only and are used widely in the literature in plays of all types. One of the famous monologue examples is Polonius’s speech to his son in Hamlet by William Shakespeare:

Here is another example of a monologue from Mark Antony in Julius Caesar:

Friends, Romans, countrymen, lend me your ears; I come to bury Caesar, not to praise him. The evil that men do lives after them; good is oft interred with their bones; So let it be with Caesar. The noble Brutus Hath told you Caesar was ambitious: If it were so, it was a grievous fault, And grievously hath Caesar answer’d it. Here, under leave of Brutus and the rest– For Brutus is an honourable man; So are they all, all honourable men– Come I to speak in Caesar’s funeral. He was my friend, faithful and just to me: Brutus says he was ambitious; Brutus is an honourable man.

There are different types of monologues that you can choose from. An understanding of the types of monologues helps you better craft it.

It is a monologue that’s used in drama and was used extensively in theatre in the 16th, 17th, and 18th centuries. The character expresses his/her feelings in the speech while other characters and actors stay silent.

Interior Monologue

It is a monologue that’s used in both fiction and nonfiction stories where a protagonist expresses his/her thoughts and mindset. It depicts the thoughts (and feelings) that a character is going through.

Dramatic Monologue

It is a poem that’s written as a speech. You’ll find dramatic monologues in Robert Browning’s poems such as My Last Duchess . It is also used in novels where a character expresses his/her views and psychological viewpoint to the readers.

Advanced Tips and Tricks to Write a Monologue

Now that you know how to write a monologue in 7 easy steps, it is time to look at advanced tips, techniques, and tricks to refine and improve your monologue. You already know the basics and you know how to get started, the following tips will help you take your monologue writing skills to the next level:

- The monologue must be concise . Generally, great monologues are long speeches but you need to make sure you aren’t adding too many details. Edit it multiple times to ensure it only consists of relevant and important details and nothing else. While the concept is to have a long speech, it doesn’t necessarily mean you have to keep it lengthy. Maintain a balance.

- Have a clear understanding of the type of monologue you’ll be writing . This goes beyond the purpose of the monologue. You can choose to write a contemporary monologue instead of a poetic one. If you aren’t sure what type of monologue you’ll write, it will get extremely tough to make sense of the final product.

- The monologue must have a strong point of view, and climax , and it must have a strong impact on the story and/or character. The idea of a great monologue is to convey important details via a speech delivered by a single character. If the outcome of a monologue isn’t intriguing and it doesn’t impact the story significantly, what’s the point of writing a monologue?

- Avoid adding too many monologues close to each other . Monologues must be used when you have to convey important information or you need to reveal a secret or add a twist to the story. Having multiple monologues simultaneously means disclosing too much important information together and that’s where it gets confusing and rather boring for the readers. Add monologues at the right place where it makes the most sense.

- Read, read, and read . The more you read the best monologues, the better. It will help you understand how to write a monologue, how to structure it, what type of language to use, and so on. You’ll find a lot of monologues throughout the literature, consider reading a few of them before writing a monologue for the first time.

- Focus on the structure of the monologue , that is, it must have a clear introduction, middle, and conclusion. Consider it a story within your story with a proper opening line and ending.

- Use a writing app or software to simplify and fasten the writing process. A writing app will help you get started quickly by selecting a relevant monologue template, adding text, and that’s all. It saves you a lot of time and you can focus on writing the monologue instead of other non-writing tasks. Consider using Squibler that’s one of the best AI writing apps in the market. You can not just write, re-write, and generate content with AI, but also organize, collaborate, and assign work on the same tool.

Final Remarks

You are ready to start writing your own monologue . You know the steps on how to write a monologue, what to expect, how to make it appealing, and what techniques to use. It is time to get into it practically.

A monologue isn’t much different from any other type of writing. Once you have the first monologue ready, you’ll see how easy the process is. Simply follow the step-by-step guide in the article and you’ll be good to go.

As a writer, you might not face any obstacles in writing a monologue. You will know how to connect with the readers, how to use climax, how to reveal secrets, how to build a character, how to connect past events to present events, how to remove fluff from the text, and so on. This seems familiar, right?

Monologues aren’t much different from any other story you write. You can master it with little practice. The more you write them, the better. Your skills will improve significantly over time.

Here is a list of the most common questions that authors ask when writing monologues:

How do I start writing a monologue?

To begin your monologue, focus on a strong, relatable theme or emotion. Dive into personal experiences, observations, or fictional scenarios that evoke the intended feeling. Remember, the key is to connect with your audience through genuine expression.

Should I follow a specific structure for my monologue?

While there’s no strict formula, consider starting with a compelling opening, followed by a development of your main idea, and conclude with a memorable closing. Allow your thoughts to flow naturally, maintaining a conversational tone that keeps listeners engaged.

How long should a monologue be?

Aim for a duration that maintains the audience’s interest. Generally, 3-5 minutes is a good guideline, but let the content dictate the length. Ensure each word serves a purpose, keeping the monologue concise and impactful.

Can I use humor in a serious monologue?

Absolutely! Humor can be a powerful tool to engage your audience and create a connection. However, balance is key. Integrate humor thoughtfully, ensuring it complements the overall tone and reinforces your message rather than distracting from it.

How do I make my monologue authentic and relatable?

Inject your personality into the narrative. Share personal anecdotes, use everyday language, and express genuine emotions. Allow your unique voice to shine through, creating a connection that resonates with the audience and makes your monologue memorable.

Related Posts

Published in What is a Screenplay?

Join 5000+ Technical Writers

Get our #1 industry rated weekly technical writing reads newsletter.

- Scriptwriting

What is a Monologue — Definition, Examples & Types Explained

S ome of the most iconic lines in the history of literature and cinema have come from monologues. As a character spills their thoughts and emotions into a speech, they often create memorable lines that connect to characters and the audience. In this article, we’ll take a look at some iconic monologues and analyze what exactly a monologue is. We’ll also take a look at the three types of monologues with examples of each. Let’s dive in.

Watch: 'You Talking To Me?' Scene Breakdown

Subscribe for more filmmaking videos like this.

What is a Monologue

First, let’s define monologue .

Screenwriting is a skill but writing dialogue is an art unto itself. What writer wouldn't want to indulge in a flowing and expansive speech? Well, as most writing teachers will tell you, this is an indulgence one should only partake in when necessary. A successful monologue, in other words, is a strategic one.

MONOLOGUE DEFINITION

What is a monologue.

A monologue is a long form speech delivered by a single character in a play or a film. The term monologue derives from the Greek words “ monos ” which translates to “alone” and “ logos ” which means “speech.” These speeches are used by writers to express a character’s thoughts, emotions, or ideas. Depending on what type of monologue is used, the character can be addressing themself, another character, or the audience.

Types of Monologues:

What is a monologue used for, what is the purpose of a monologue.

A story is made up of bits of information that is communicated to the audience over time. When it comes to information regarding a character’s thoughts or emotions, a monologue is effective at efficiently communicating this info to the audience and/or to another character.

A monologue is often the vocalization of a character’s thoughts giving insight that reveals details about a story’s plot or its characters. This character’s speech in and of itself can propel the story forward based on how other characters react to it and what events are caused by it.

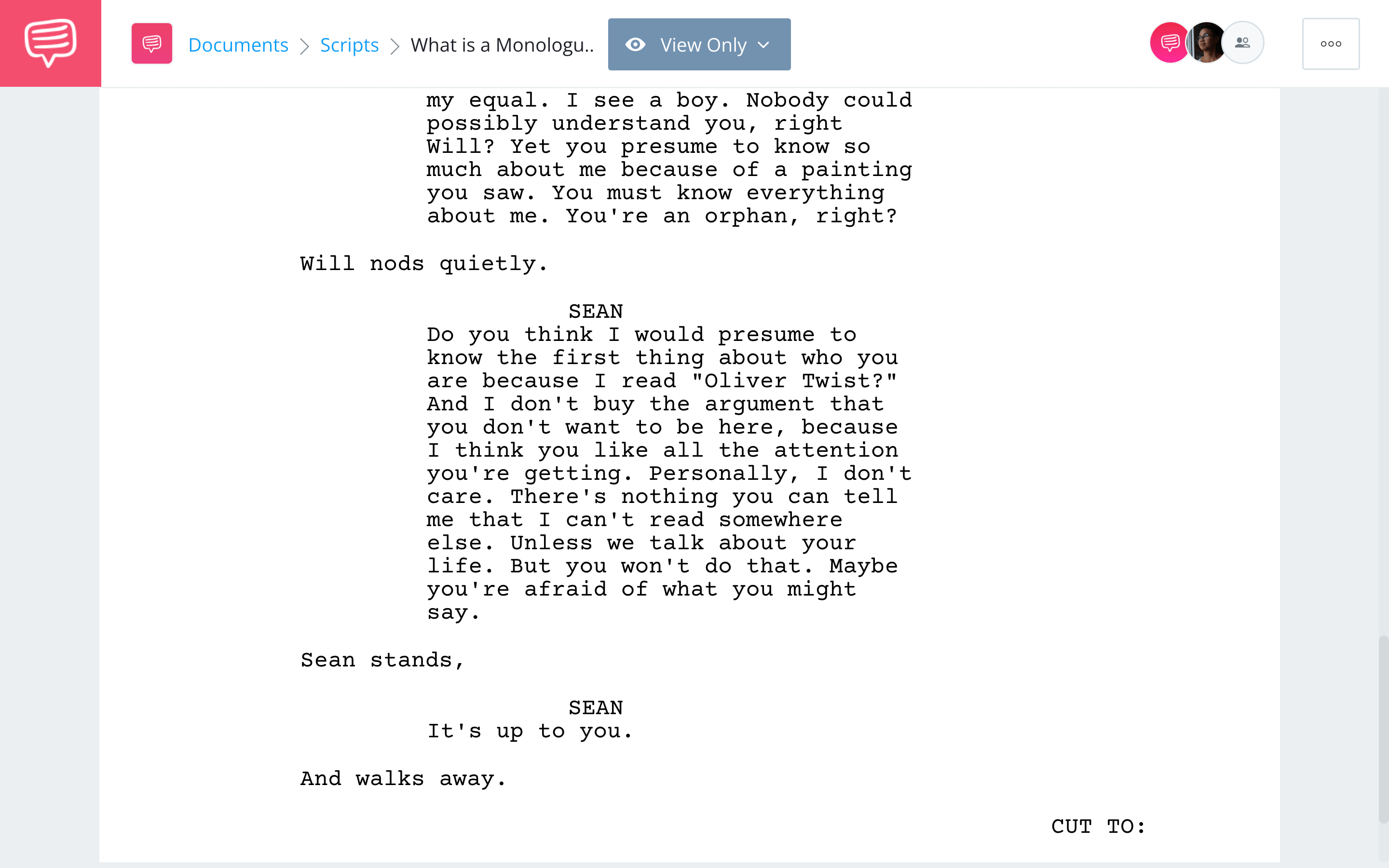

A great example of this can be found in the Good Will Hunting script . Will (Matt Damon) is resistant to any court mandated therapist. However, this monologue by Sean (Robin Williams) caused Will to finally be open to meeting further with him.

We brought the iconic monologue into StudioBinder's screenwriting software to analyze it further. Click the image below to read the entire scene. With writing this good, no wonder this script won the Oscar.

Good Will Hunting script • Read the entire scene

As you can see, this monologue does multiple things simultaneously for the film’s story. It reveals exposition about Sean. We learn he is a veteran, that he loved his wife deeply, and that he lost his wife to cancer.

At the same time, the monologue propels the plot forward by allowing Sean to finally break through to Will.

Good monologues will either reveal character information or plot info. A great monologue will reveal both while moving the story forward all at the same time. Let’s take a look at the different types of monologues you can use in your own work.

Related Posts

- What Does a Screenwriter Do? →

- Fundamental Ways to Write ‘Realistic’ Dialogue →

- FREE: Write and create professionally formatted screenplays →

What is a Monologue in Literature and Film?

Types of monologues.

It is important to understand the type of monologues and their unique properties. There are three different types of monologues that are all defined by who the monologue is delivered to. Who the monologue is delivered to also influences the content of the monologue.

What is the difference between a monologue and a soliloquy? This is a great place to start. A soliloquy is a type of monologue in which a character delivers a long speech to themself rather than to another character or to the audience. In a way, a soliloquy is a character talking to themself trying to analyze their own thoughts, emotions, or predicament.

One of the most famous excerpts from any play in history is in fact a soliloquy from Shakespeare’s Hamlet . In this iconic soliloquy, sometimes known as the to be or not to be monologue Hamlet ponders life and death and whether the hardships of life are too difficult to manage.

To be, or not to be, that is the question:

Whether 'tis nobler in the mind to suffer

The slings and arrows of outrageous fortune,

Or to take arms against a sea of troubles

And by opposing end them. To die—to sleep,

No more; and by a sleep to say we end

The heart-ache and the thousand natural shocks

That flesh is heir to: 'tis a consummation

Devoutly to be wish'd. To die, to sleep;

To sleep, perchance to dream—ay, there's the rub:

For in that sleep of death what dreams may come,

When we have shuffled off this mortal coil,

Must give us pause—there's the respect

That makes calamity of so long life.

For who would bear the whips and scorns of time,

Th'oppressor's wrong, the proud man's contumely,

The pangs of dispriz'd love, the law's delay,

The insolence of office, and the spurns

That patient merit of th'unworthy takes,

When he himself might his quietus make

With a bare bodkin? Who would fardels bear,

To grunt and sweat under a weary life,

But that the dread of something after death,

The undiscovere'd country, from whose bourn

No traveller returns, puzzles the will,

And makes us rather bear those ills we have

Than fly to others that we know not of?

Thus conscience doth make cowards of us all,

And thus the native hue of resolution

Is sicklied o'er with the pale cast of thought,

And enterprises of great pith and moment

With this regard their currents turn awry

And lose the name of action.

From this monologue example, you can see that soliloquies are often the most genuine and honest because a character is talking to themself and has no reason to lie. So the reliability behind the monologue is not questioned by the audience.

Dramatic monologue

A monologue that is delivered by a character to another character or to the audience is defined as a dramatic dialogue. Dramatic dialogues are long in length and often unbroken by the speech of other characters.

These are the most common monologues found in film since characters deliver monologues mainly to other characters. While dramatic monologues in both film and plays are commonly delivered to other characters, they can also be delivered directly to the audience if the fourth wall is broken .

One of the best movie monologues from Call Me By Your Name is a showstopper. Delivered by a pitch-perfect Michael Stuhlbarg, this speech has everything you’d want in a monologue. It feels natural yet important, and it is informed both by the reactions of Elio and Mr. Perlman’s own internal struggles. Give it a watch:

Call Me By Your Name • a monologue from a movie

Internal monologue.

An internal monologue is a type of monologue in which a character’s thoughts are expressed but not vocalized in the world of the story. In literature, this is often expressed in italicized paragraphs to indicate that the words are not spoken out loud. In a play, this can be delivered as an aside. In film, an internal monologue is delivered through voice over as a way for the audience to witness the thoughts of a character.

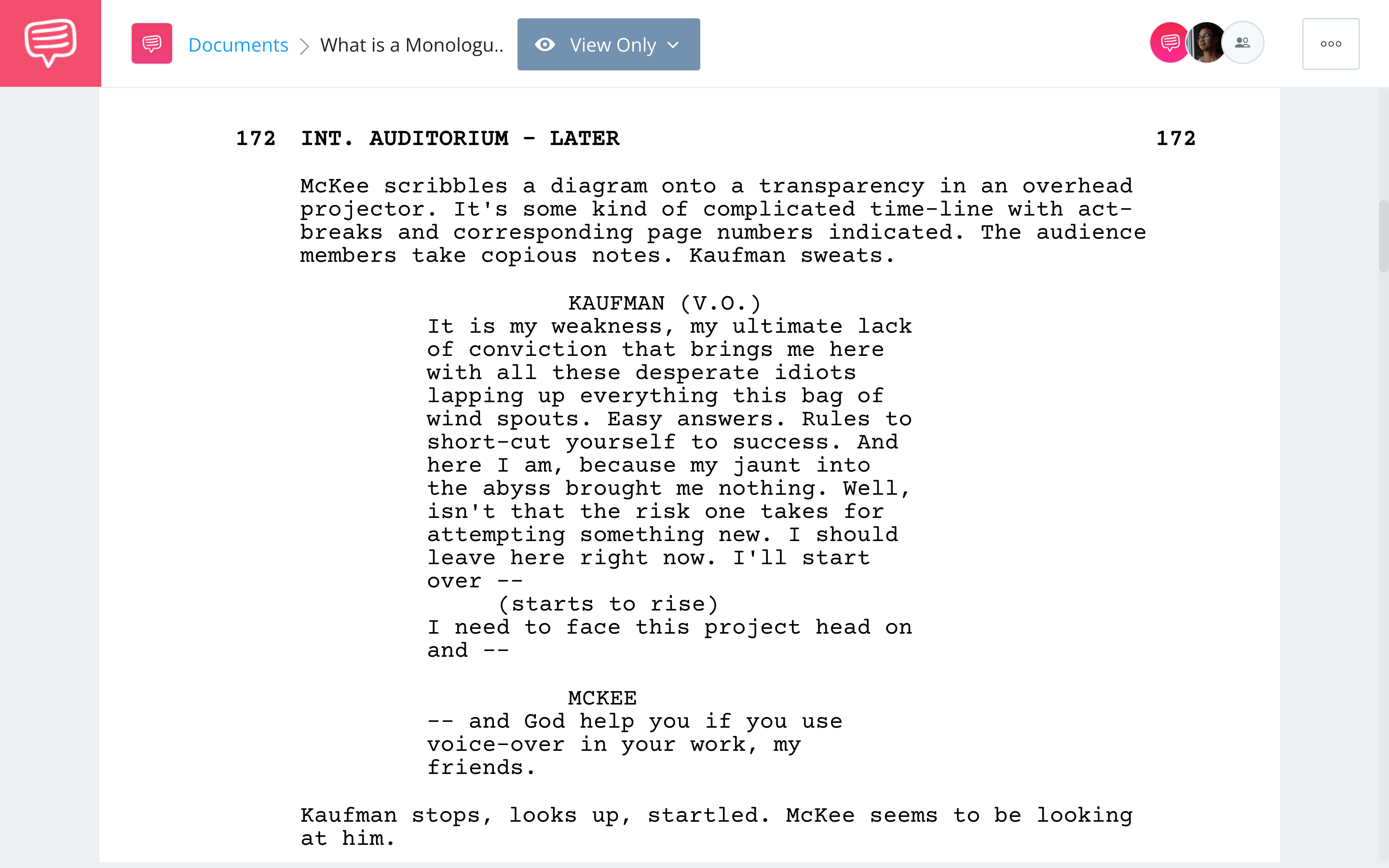

This brilliant internal monologue from one of Charlie Kaufman’s best films Adaptation gives us insight into what the character is thinking. This is then immediately and ironically ridiculed by the speaker in the scene.

McKee monologue

And here's the scene from the script. A bit of screenwriting about how to be a great screenwriter!

Adaptation Monologue Example • Read Full Scene

Like the irony underscores in the scene, internal monologues and voice over can be dangerous and ineffective when used as a crutch. But when used cleverly as it is in this example by Charlie Kaufman, it can elevate the creativity of a film and how it connects to an audience.

How to Write ‘Realistic’ Dialogue

Monologues in film are most commonly delivered within a larger dialogue scene. A part of creating a memorable monologue is by writing great dialogue that frames it. In our next article, we lay out some fundamental tips to writing realistic, compelling dialogue.

Up Next: Writing ‘Realistic’ Dialogue →

Write and produce your scripts all in one place..

Write and collaborate on your scripts FREE . Create script breakdowns, sides, schedules, storyboards, call sheets and more.

- Pricing & Plans

- Product Updates

- Featured On

- StudioBinder Partners

- The Ultimate Guide to Call Sheets (with FREE Call Sheet Template)

- How to Break Down a Script (with FREE Script Breakdown Sheet)

- The Only Shot List Template You Need — with Free Download

- Managing Your Film Budget Cashflow & PO Log (Free Template)

- A Better Film Crew List Template Booking Sheet

- Best Storyboard Softwares (with free Storyboard Templates)

- Movie Magic Scheduling

- Gorilla Software

- Storyboard That

A visual medium requires visual methods. Master the art of visual storytelling with our FREE video series on directing and filmmaking techniques.

We’re in a golden age of TV writing and development. More and more people are flocking to the small screen to find daily entertainment. So how can you break put from the pack and get your idea onto the small screen? We’re here to help.

- Making It: From Pre-Production to Screen

- VFX vs. CGI vs. SFX — Decoding the Debate

- What is a Freeze Frame — The Best Examples & Why They Work

- TV Script Format 101 — Examples of How to Format a TV Script

- Best Free Musical Movie Scripts Online (with PDF Downloads)

- What is Tragedy — Definition, Examples & Types Explained

- 0 Pinterest

Tips on Writing a Monologue

Writing a monologue can be challenging because they have to show character and plot detail without bogging down the play or making the audience yawn.

A successful dramatic monologue should indicate what’s in the mind of one character while adding emotion or wow-factor to the rest of the play.

You may choose to write a monologue to add pepper to the play or raise the stakes in general. Most importantly, you should begin by constructing your monologue before writing and polishing it to perfection.

These clear-cut guidelines will help you write your monologue.

What is a Monologue?

Simply put, a monologue is a long presentation by a solo character in a film or theatre gig.

Monologues can be one character having a conversation with themselves or the audience, or they can be a character conveying a message to others in the scene.

The word monologue is an antonym of the word dialogue and is derived from the Greek terms that stand for alone and speak.

The primary goal of writing a monologue is to give meaning to your storytelling- to offer your audience more information about a character or the plot.

Applied tactfully, a monologue is an awesome way to share your internal thoughts or backstory of a character or mention particular elements about your plot.

How to Distinguish a Monologue from a Soliloquy

A monologue that involves a character talking to themselves, “internal monologue” is known as a “soliloquy.”

You can identify this tool in William Shakespeare’s famous plays and specifically the soliloquy “To Be or Not to Be” speech from Hamlet. In the soliloquy, Hamlet questions whether he should continue to challenge his malicious uncle or kill himself.

Key Tips for Writing an Effective Monologue

Just because monologues involve one character doesn’t mean they are simple to write. Monologue scripts should be written with singular consideration and moderation. You wouldn’t want to bore your audience while failing to drive the point home at the end of the day.

Below are the important factors to keep in mind when writing a monologue:

- The Character’s Essence

Newbie scriptwriters can be overly ambitious by writing monologues to display their writing techniques; however, be wary of this as it can rapidly pull viewers out of the plot.

With so many monologues to explore, when writing yours, you should make it feel natural and inconspicuous in your story, so it should be voiced by your character along with their viewpoint.

Start by using language that is authentic to your character to help craft a constructive monologue.

- The Character’s Backstory or Significance to the Storyline

The essence of monologues is to unfold significant details about a character or the plot, so you must advance the speaking character and capture the plot for them to occupy even before you begin your writing.

Monologues aid in telling the audience about a character’s previous experiences and traits.

- The Character’s Ambition

In reality, you rarely sit down and have a conversation with yourself unless you have a dire reason or a life-changing decision to make. Similarly, for any monologue, the character should have a motivation for it.

How to Write a Dramatic Monologue

Superior monologues are well-structured with an introduction, a body and a conclusion. This build-up of a resolution is crucial in long stories because they prevent stories from becoming stale and boring.

So here’s how to organize your monologue:

Ideally, people don’t randomly talk to themselves unless they’re nutjobs! They start to monologue in reaction to an event that took place or something that was said.

When writing a monologue, try easing in your audience with your first line. Something as simple as “ I can’t stop thinking about that thing that happened last week” is a great way for a character to begin a monologue speech.

Middle

The central part of a monologue can be the toughest one to crack. Because people often get bored with long speeches, it’s good to keep your monologues interesting by making them unpredictable.

Incorporate tiny tricks and shocking twists into your storytelling. Use captivating plot features to unique character descriptions to maintain the freshness of your monologues.

It’s a common practice to wrap up monologues using convincing statements that explain the essence of the plot. However, don’t overindulge in this technique as it can be monotonous and uninteresting. Rather, trust your viewers to extract the meaning of the monologue themselves.

Takeaways for Writing a Solid Monologue

- Practice, Practice, Practice

The best tool for writing an effective monologue is to practice. Your first monologues may seem amateur but keep pushing and you’ll see your monologue writing skills improving in no time!

- Pay Attention to Detail

Monologues created in general language are unmemorable. The best monologues apply concrete details that readers can latch onto and recall. Spice up your monologues by adding striking words.

When feeling mentally blocked, try using your five senses to create imagery to make them unforgettable.

- Keep it Short and Sweet

Monologues shouldn’t fill up tons of script space- they should be as concise as possible. This doesn’t mean all your monologues have to be short; rather focus on editing and pointing out the important details.

The more centred your monologue, the more compelling and notable it will be for your audience.

- Arrangement is Crucial

Monologues are powerful writing tools but too many of them clustered in your story will bother your readers. Restrain yourself by creating a few monologues and spacing them out in your story so they’re not too close together. This will make each monologue stand out and protect your audience from boredom.

- Learn From the Best

Prominent monologues draw their inspiration from other prominent monologues. So if you’re feeling stuck, tap into the skills of great monologue writers such as William Shakespeare.

After you’ve gone through Hamlet, look into Romeo and Juliet and A Midsummer Night’s Dream .

Overall, enjoy writing your monologue! If you feel like something isn’t working out, you are mandated to substitute it until it rings true.

Head on over to LivingWriter – make a blank story and start crafting your masterpiece right now!

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Writing Tips

- Travel Writing

- Try LivingWriter

- How to Write a Powerful Monologue (With Examples)

by Joe Keith | Feb 19, 2022 | Theater | 0 comments

Since ancient Greek theater, a powerful monologue can be used as a way to captivate an audience. Some of the greatest moments in theatre and films have come in the form of monologues.

However, it is one thing to have monologues in your script, and it is another thing to know why you are writing them as well as how to write them well.

Before going into all the interesting details about writing a strong monologue, let’s see what a monologue actually is.

My musician friends could always practice what they loved doing, but I can’t go on a street corner and start reciting a monologue. Acting is very collaborative, and you always need other people with you – mainly an audience. Julia Stiles

What is a Monologue?

The word “monologue” consists of the Greet roots for “alone” and “speak.” The term refers to a long speech by a single character that is either addressing other characters in the scene or talking to the audience.

A monologue can serve a specific purpose in storytelling. If used carefully, a powerful monologue can give the audience more details about a plot or a character. They are a great way to share the backstory of a character or his internal thoughts.

While monologues and soliloquy are similar (since in both, speeches are presented by a single character), the main difference between them is that the speaker in a monologue reveals his thoughts to other characters in the scene or the audience, while the speaker in a soliloquy expresses his thoughts to himself.

Examples of Powerful Monologues

- Jocasta in Oedipus the King: “Why should a mortal man, the sport of chance, with no assured foreknowledge, be afraid?”

- Antigone in Antigone: “Yea for these laws were not ordained by Zeus, And she who sits enthroned with gods below…”

- Marc Antony in Julius Caesar: “Friends, Romans, Countrymen, lend me your ears; I have come to bury Caesar, not to praise him…”

- Flute (as Thisbe) in A Midsummer Night’s Dream: “Asleep, my love? What, dean, my dove? O Pyramus, arise!”

- Gloucester in Richard III: “Now is the winter of our discontent Made glorious summer by this sun of York…”

- Jacques in As You Like it: “All the world’s a stage, And all the men and women merely players…”

- Hamlet in Hamlet: “To be, or not to be, that is the question…”

- Viola in Twelfth Night: “I left no ring with her: what means this lady?”

Monologue Structuring Tips

The structuring of a good monologue is similar to that of a good story ; it will have a beginning, a middle, and an end. Without a buildup and a resolution, long stories can become stale and monotonous.

- Beginning: there’s always a reason to initiate a monologue, even in real life. People usually start speaking in response to something that happened or was said. Your first line must make a smooth transition into a monologue. An easy way to start a monologue could be “I was thinking of what was said of him…”

- Middle: This is usually the toughest part to write in a monologue. This is because long speeches can bore your viewers, and so it is important to avoid predictable monologues. You can achieve this by crafting little twists and turns into the storytelling. Adding such interesting plot details, and unique ways the character describes them can keep your monologues engaging and fresh.

- End: it is common for monologues to end with a quick statement of meaning, especially monologues meant to convince other characters in the scene to do something. You don’t have to do so much explanation nonetheless, you can trust your audience to find meaning in it for themselves.

In conclusion , there has to be a purpose for using a monologue in a play or film. It shouldn’t be used merely to tell what you can’t show. Instead, it should add more depth to your story, or be a call to action.

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Recent Posts

- Boost Your Confidence With Dancing

- How to Find Your Acting Niche

- 5 Plays Every Actor Should Read

- Why is Music so Important for Motivation?

Recent Comments

- PRO Courses Guides New Tech Help Pro Expert Videos About wikiHow Pro Upgrade Sign In

- EDIT Edit this Article

- EXPLORE Tech Help Pro About Us Random Article Quizzes Request a New Article Community Dashboard This Or That Game Popular Categories Arts and Entertainment Artwork Books Movies Computers and Electronics Computers Phone Skills Technology Hacks Health Men's Health Mental Health Women's Health Relationships Dating Love Relationship Issues Hobbies and Crafts Crafts Drawing Games Education & Communication Communication Skills Personal Development Studying Personal Care and Style Fashion Hair Care Personal Hygiene Youth Personal Care School Stuff Dating All Categories Arts and Entertainment Finance and Business Home and Garden Relationship Quizzes Cars & Other Vehicles Food and Entertaining Personal Care and Style Sports and Fitness Computers and Electronics Health Pets and Animals Travel Education & Communication Hobbies and Crafts Philosophy and Religion Work World Family Life Holidays and Traditions Relationships Youth

- Browse Articles

- Learn Something New

- Quizzes Hot

- This Or That Game

- Train Your Brain

- Explore More

- Support wikiHow

- About wikiHow

- Log in / Sign up

- Education and Communications

How to Write a Monologue for a Play

Last Updated: February 8, 2023 Fact Checked

This article was co-authored by Ben Whitehair . Ben Whitehair is a Social Media Expert and the Chief Operating Officer (COO) of TSMA Consulting. With over a decade of experience in the social media space, he specializes in leveraging social media for business and building relationships. He also focuses on social media’s impact on the entertainment industry. Ben graduated summa cum laude from The University of Colorado at Boulder with BAs in Theatre and Political Science as well as a Leadership Certificate. In addition to his work as CIO, Ben is a certified business and mindset coach and National Board Member of SAG-AFTRA. He is also a successful entrepreneur as the Co-Founder of Working.Actor, the premier business academy and coaching community for actors. There are 9 references cited in this article, which can be found at the bottom of the page. This article has been fact-checked, ensuring the accuracy of any cited facts and confirming the authority of its sources. This article has been viewed 318,483 times.

Dramatic monologues can be tricky to write as they must provide character detail and plot without bogging down the play or boring the audience. An effective dramatic monologue should express the thoughts of one character and add emotion or intrigue to the rest of the play. You may decide to write a monologue to add character detail to the play or to raise the stakes of the play overall. You should start by structuring the monologue so you can then write and polish the monologue to perfection.

Structuring the Monologue

- You can write a monologue for the main character to give them a chance to speak on their own, or for a minor character to give them a chance to finally express themselves.

- The monologue should add tension, conflict, or emotion to the rest of the play and give the audience new insight into an existing issue or problem.

- For example, if there's a character who has been mute during the first act, they could have a monologue in the second act where they reveal why they are mute.

- A monologue can address a specific character, especially if the speaker wants to express their emotions or feelings to them. The character can also express their thoughts or feelings about an event for the audience's benefit.

- Create an outline that includes a beginning, middle, and end for the monologue. Note what will occur in each stage of the monologue.

- For example, you may write: “Beginning: Elena the mute speaks. Middle: Elena tells us why and how she became mute. Ending: Elena realizes she prefers staying silent to saying her thoughts out loud.”

- Alternatively, write the first and last lines of the monologue, then create the content between them to generate ideas and thoughts for the monologue.

- The Duchess of Berwick’s monologue in Oscar Wilde’s Lady Windermere’s Fan . [3] X Research source

- Jean’s monologue in August Strindberg’s Miss Julie . [4] X Research source

- Christy’s monologue in John Millington Synge’s The Playboy of the Western World . [5] X Research source

- “My Princesa” monologue by Antonia Rodriguez.

Writing the Monologue

- You may start the monologue with a big revelation right away, such as Christy’s monologue in John Millington Synge’s The Playboy of the Western World . [6] X Research source

- Christy's monologue tells the audience right away that the speaker killed his father. It then discusses the events leading up to the murder and how the speaker feels about his actions.

- For example, the “My Princesa” monologue is written from the perspective of a Latino father. He uses terms and sayings that are specific to him, such as “whoop his ass” and “Oh hell naw!” These make the monologue engaging and add character detail.

- Another example is The Duchess of Berwick’s monologue. Wilde uses the character’s casual, conversational tone to reveal the plot and keep the audience engaged. [7] X Research source

- For example, in his monologue, Christy addresses his father's murder by reflecting on past choices and moments that may have lead to his pivotal decision.

- For example, Jean’s monologue opens with striking images of his childhood, “I lived in a hovel provided by the state, with seven brothers and sisters and a pig; out on a barren stretch where nothing grew, not even a tree...”

- The details in the monologue help to paint a clear picture of Jean’s childhood hovel. They also add to his character and help the reader get a better sense of his past.

- For example, in his monologue, Christy reveals that his father was not a very considerate person or a good father. He explains that he did the world a favor by killing his father. [11] X Research source

- For example, in his monologue, Jean reveals that he tried to kill himself because he was born too low to be with Miss Julie. He then ends the monologue with a reflection on what he learned about his feelings for Miss Julie. [13] X Research source

Polishing the Monologue

- Remove any redundant lines or awkward phrases. Cut out any words that do not add to the character’s voice or language. Include only the essential details in the monologue.

- Note moments where the monologue is confusing or verbose. Simplify these areas so the monologue is easy to follow for the listener.

Sample Monologues

Expert Q&A

You Might Also Like

- ↑ http://pediaa.com/how-to-write-a-monologue/

- ↑ Ben Whitehair. Acting Coach. Expert Interview. 3 June 2021.

- ↑ https://www.openingmonologue.com/from/lady-windermeres-fan/

- ↑ https://www.openingmonologue.com/?s=miss+julie

- ↑ https://www.instantmonologues.com/preview/Synge_Playboy

- ↑ http://www.monologuearchive.com/s/synge_001.html

- ↑ http://www.monologuearchive.com/w/wilde_008.html

- ↑ http://www.monologuegenie.com/monologue-writing-101.html

- ↑ http://www.monologuearchive.com/s/strindberg_012.html

About This Article

To write a monologue for a play, break your monologue up so there's a beginning, middle, and end, like you're telling a mini story. You should write the monologue from the perspective of one of the characters in the play, and it should have a clear purpose, like adding tension to the play or helping the audience understand something. For example, your monologue could be one of the main characters explaining to the audience how they killed someone. Try to keep your monologue short and to the point, and avoid using long or redundant sentences. To learn how to polish your monologue when you're finished writing it, scroll down! Did this summary help you? Yes No

- Send fan mail to authors

Reader Success Stories

Jan 13, 2018

Did this article help you?

Agnes Riedmann

Feb 8, 2018

Apr 29, 2017

Khushi Khakhar

Jan 21, 2017

Maram Muhmed

Feb 10, 2017

Featured Articles

Trending Articles

Watch Articles

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Do Not Sell or Share My Info

- Not Selling Info

wikiHow Tech Help Pro:

Develop the tech skills you need for work and life

Story Arcadia

How To Write A Monologue

Writing a monologue can be a challenging but rewarding task. Whether you are a playwright, actor, or simply someone looking to express themselves through the art of solo performance, crafting a compelling monologue requires careful attention to detail and a deep understanding of character and storytelling.

The first step in writing a monologue is to choose a compelling and relatable topic. This could be a personal experience, an issue that is important to you, or a fictional scenario that resonates with your audience. Once you have chosen your topic, it’s important to consider the perspective from which you will be speaking. Are you speaking as yourself, or are you embodying a character? Understanding the point of view from which you are speaking will help guide the tone and language of your monologue.

Next, consider the structure of your monologue. A well-crafted monologue typically has a clear beginning, middle, and end. The beginning should grab the audience’s attention and establish the setting and context of the monologue. The middle should delve deeper into the topic at hand, exploring emotions, conflicts, and revelations. The end should provide closure or leave the audience with something to ponder.

When it comes to writing the actual dialogue of your monologue, it’s important to make every word count. Each line should serve a purpose in advancing the story or revealing something about the character. Consider using vivid imagery, sensory details, and figurative language to bring your words to life and engage the audience’s imagination.

As you write your monologue, don’t be afraid to revise and refine your work. Read it aloud to yourself or perform it for others to get feedback on how it resonates. Pay attention to pacing, rhythm, and emotional beats as you fine-tune your performance.

In conclusion, writing a monologue requires careful consideration of topic, perspective, structure, dialogue, and revision. By approaching this task with creativity and dedication, you can create a powerful piece of solo performance that resonates with audiences and leaves a lasting impact.

Related Pages:

- How To Write Slam Poetry

- How To Write A Performance Review

- How To Write Performance Review

- How To Write An Editorial

- How To Write A Narrative

- How To Write A Problem Statement

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Literary Terms

- Definition & Examples

- When & How to Use a Monologue

I. What is a Monologue?

A monologue is a speech given by a single character in a story. In drama, it is the vocalization of a character’s thoughts; in literature, the verbalization. It is traditionally a device used in theater—a speech to be given on stage—but nowadays, its use extends to film and television.

II. Example of a Monologue

A monologue speaks at people, not with people. Many plays and shows involving performers begin with a single character giving a monologue to the audience before the plot or action begins. For example, envision a ringleader at a circus…

Ladies and Gentleman, Boys and Girls!

Tonight, your faces will glow with wonder

As you witness some of the greatest acts ever seen in the ring!