Erik Erikson’s Stages of Psychosocial Development

Saul Mcleod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul Mcleod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

On This Page:

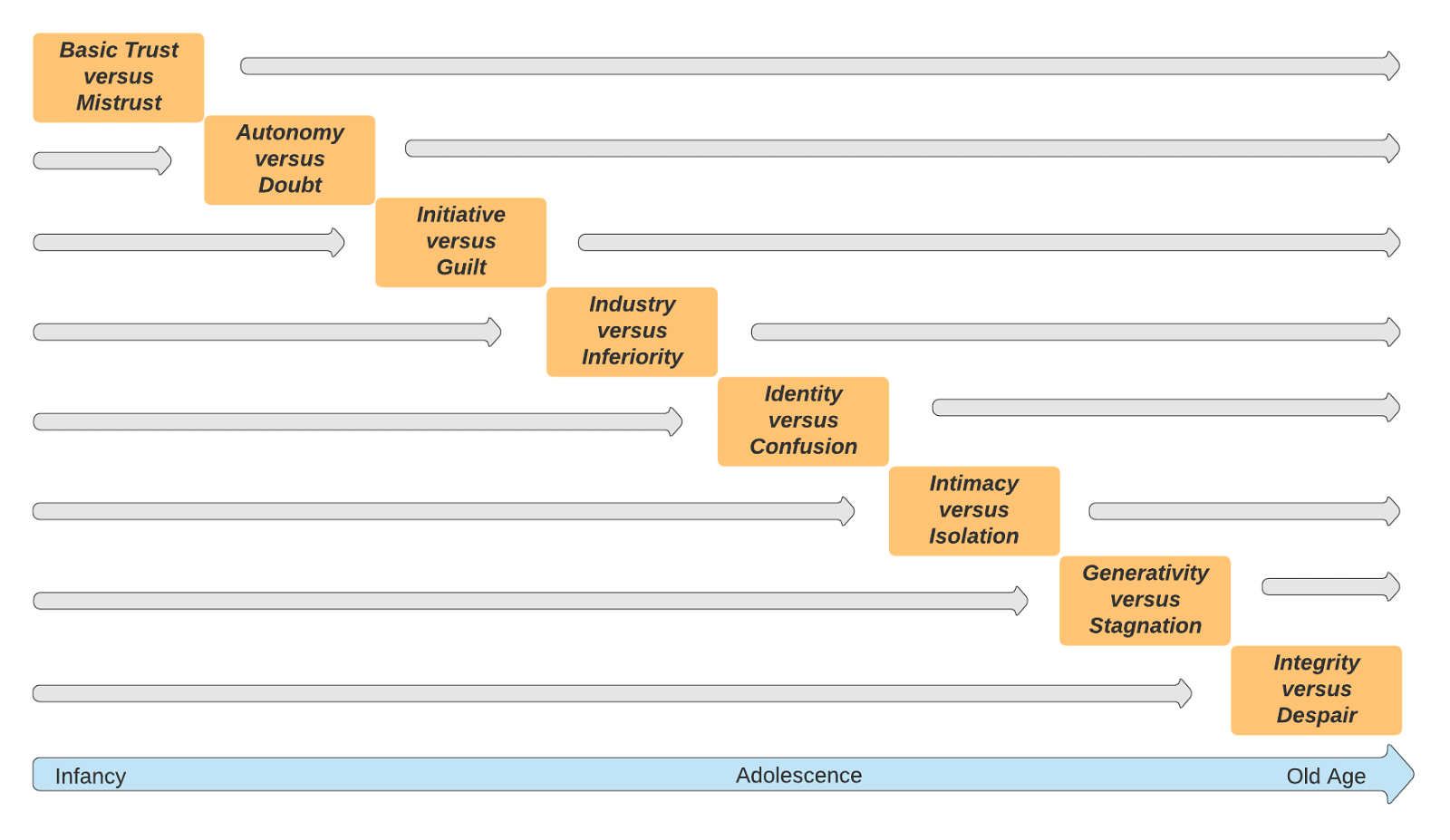

Erikson maintained that personality develops in a predetermined order through eight stages of psychosocial development, from infancy to adulthood. During each stage, the person experiences a psychosocial crisis that could positively or negatively affect personality development.

For Erikson (1958, 1963), these crises are psychosocial because they involve the psychological needs of the individual (i.e., psycho) conflicting with the needs of society (i.e., social).

According to the theory, successful completion of each stage results in a healthy personality and the acquisition of basic virtues. Basic virtues are characteristic strengths that the ego can use to resolve subsequent crises.

Failure to complete a stage can result in a reduced ability to complete further stages and, therefore, a more unhealthy personality and sense of self. These stages, however, can be resolved successfully at a later time.

Stage 1. Trust vs. Mistrust

Trust vs. mistrust is the first stage in Erik Erikson’s theory of psychosocial development. This stage begins at birth continues to approximately 18 months of age. During this stage, the infant is uncertain about the world in which they live, and looks towards their primary caregiver for stability and consistency of care.

Here’s the conflict:

Trust : If the caregiver is reliable, consistent, and nurturing, the child will develop a sense of trust, believing that the world is safe and that people are dependable and affectionate.

This sense of trust allows the child to feel secure even when threatened and extends into their other relationships, maintaining their sense of security amidst potential threats.

Mistrust : Conversely, if the caregiver fails to provide consistent, adequate care and affection, the child may develop a sense of mistrust and insecurity .

This could lead to a belief in an inconsistent and unpredictable world, fostering a sense of mistrust, suspicion, and anxiety.

Under such circumstances, the child may lack confidence in their ability to influence events, viewing the world with apprehension.

Infant Feeding

Feeding is a critical activity during this stage. It’s one of infants’ first and most basic ways to learn whether they can trust the world around them.

It sets the stage for their perspective on the world as being either a safe, dependable place or a place where their needs may not be met.

This consistent, dependable care helps the child feel a sense of security and trust in the caregiver and their environment.

They understand that when they have a need, such as hunger, someone will be there to provide for that need.

These negative experiences can lead to a sense of mistrust in their environment and caregivers.

They may start to believe that their needs may not be met, creating anxiety and insecurity.

Success and Failure In Stage One

Success in this stage will lead to the virtue of hope . By developing a sense of trust, the infant can have hope that as new crises arise, there is a real possibility that other people will be there as a source of support.

Failing to acquire the virtue of hope will lead to the development of fear. This infant will carry the basic sense of mistrust with them to other relationships. It may result in anxiety, heightened insecurities, and an over-feeling mistrust in the world around them.

Consistent with Erikson’s views on the importance of trust, research by Bowlby and Ainsworth has outlined how the quality of the early attachment experience can affect relationships with others in later life.

The balance between trust and mistrust allows the infant to learn that while there may be moments of discomfort or distress, they can rely on their caregiver to provide support.

This helps the infant to build resilience and the ability to cope with stress or adversity in the future.

Stage 2. Autonomy vs. Shame and Doubt

Autonomy versus shame and doubt is the second stage of Erik Erikson’s stages of psychosocial development. This stage occurs between the ages of 18 months to approximately 3 years. According to Erikson, children at this stage are focused on developing a sense of personal control over physical skills and a sense of independence.

Autonomy : If encouraged and supported in their increased independence, children will become more confident and secure in their ability to survive.

They will feel comfortable making decisions, explore their surroundings more freely, and have a sense of self-control. Achieving this autonomy helps them feel able and capable of leading their lives.

Shame and Doubt : On the other hand, if children are overly controlled or criticized, they may begin to feel ashamed of their autonomy and doubt their abilities.

This can lead to a lack of confidence, fear of trying new things, and a sense of inadequacy about their self-control abilities.

What Happens During This Stage?

The child is developing physically and becoming more mobile, discovering that he or she has many skills and abilities, such as putting on clothes and shoes, playing with toys, etc.

Such skills illustrate the child’s growing sense of independence and autonomy.

For example, during this stage, children begin to assert their independence, by walking away from their mother, picking which toy to play with, and making choices about what they like to wear, to eat, etc.

Toilet Training

This is when children start to exert their independence, taking control over their bodily functions, which can greatly influence their sense of autonomy or shame and doubt.

Autonomy : When parents approach toilet training in a patient, supportive manner, allowing the child to learn at their own pace, the child may feel a sense of accomplishment and autonomy.

They understand they have control over their own bodies and can take responsibility for their actions. This boosts their confidence, instilling a sense of autonomy and a belief in their ability to manage personal tasks.

Shame and Doubt : Conversely, if the process is rushed, if there’s too much pressure, or if parents respond with anger or disappointment to accidents, the child may feel shame and start doubting their abilities.

They may feel bad about their mistakes, and this can lead to feelings of shame, self-doubt, and a lack of confidence in their autonomy.

Success and Failure In Stage Two

Erikson states parents must allow their children to explore the limits of their abilities within an encouraging environment that is tolerant of failure.

Success in this stage will lead to the virtue of will . If children in this stage are encouraged and supported in their increased independence, they become more confident and secure in their own ability to survive in the world.

The infant develops a sense of personal control over physical skills and a sense of independence.

Suppose children are criticized, overly controlled, or not given the opportunity to assert themselves. In that case, they begin to feel inadequate in their ability to survive, and may then become overly dependent upon others, lack self-esteem , and feel a sense of shame or doubt in their abilities.

How Can Parents Encourage a Sense of Control?

Success leads to feelings of autonomy, and failure results in shame and doubt.

Erikson states it is critical that parents allow their children to explore the limits of their abilities within an encouraging environment that is tolerant of failure.

For example, rather than put on a child’s clothes, a supportive parent should have the patience to allow the child to try until they succeed or ask for assistance.

So, the parents need to encourage the child to become more independent while at the same time protecting the child so that constant failure is avoided.

A delicate balance is required from the parent. They must try not to do everything for the child, but if the child fails at a particular task, they must not criticize the child for failures and accidents (particularly when toilet training).

The aim has to be “self-control without a loss of self-esteem” (Gross, 1992).

The balance between autonomy and shame and doubt allows the child to understand that while they can’t always control their environment, they can exercise control over their actions and decisions, thus developing self-confidence and resilience.

Stage 3. Initiative vs. Guilt

Initiative versus guilt is the third stage of Erik Erikson’s theory of psychosocial development. During the initiative versus guilt stage, children assert themselves more frequently through directing play and other social interaction.

Initiative : When caregivers encourage and support children to take the initiative, they can start planning activities, accomplish tasks, and face challenges.

The children will learn to take the initiative and assert control over their environment.

They can begin to think for themselves, formulate plans, and execute them, which helps foster a sense of purpose.

Guilt : If caregivers discourage the pursuit of independent activities or dismiss or criticize their efforts, children may feel guilty about their desires and initiatives.

This could potentially lead to feelings of guilt, self-doubt, and lack of initiative.

These are particularly lively, rapid-developing years in a child’s life. According to Bee (1992), it is a “time of vigor of action and of behaviors that the parents may see as aggressive.”

During this period, the primary feature involves the child regularly interacting with other children at school. Central to this stage is play, as it allows children to explore their interpersonal skills through initiating activities.

The child begins to assert control and power over their environment by planning activities, accomplishing tasks, and facing challenges.

Exploration

Here’s why exploration is important:

Developing Initiative : Exploration allows children to assert their power and control over their environment. Through exploration, children engage with their surroundings, ask questions, and discover new things.

This active engagement allows them to take the initiative and make independent choices, contributing to their autonomy and confidence.

Learning from Mistakes : Exploration also means making mistakes, and these provide crucial learning opportunities. Even if a child’s efforts lead to mistakes or failures, they learn to understand cause and effect and their role in influencing outcomes.

Building Self-Confidence : When caregivers support and encourage a child’s explorations and initiatives, it bolsters their self-confidence. They feel their actions are valuable and significant, which encourages them to take more initiative in the future.

Mitigating Guilt : If caregivers respect the child’s need for exploration and do not overly criticize their mistakes, it helps prevent feelings of guilt. Instead, the child learns it’s okay to try new things and perfectly fine to make mistakes.

Success and Failure In Stage Three

Children begin to plan activities, make up games, and initiate activities with others. If given this opportunity, children develop a sense of initiative and feel secure in their ability to lead others and make decisions. Success at this stage leads to the virtue of purpose .

Conversely, if this tendency is squelched, either through criticism or control, children develop a sense of guilt . The child will often overstep the mark in his forcefulness, and the danger is that the parents will tend to punish the child and restrict his initiative too much.

It is at this stage that the child will begin to ask many questions as his thirst for knowledge grows. If the parents treat the child’s questions as trivial, a nuisance, or embarrassing or other aspects of their behavior as threatening, the child may feel guilty for “being a nuisance”.

Too much guilt can slow the child’s interaction with others and may inhibit their creativity. Some guilt is, of course, necessary; otherwise the child would not know how to exercise self-control or have a conscience.

A healthy balance between initiative and guilt is important.

The balance between initiative and guilt during this stage can help children understand that it’s acceptable to take charge and make their own decisions, but there will also be times when they must follow the rules or guidelines set by others. Successfully navigating this stage develops the virtue of purpose.

How Can Parents Encourage a Sense of Exploration?

In this stage, caregivers must provide a safe and supportive environment that allows children to explore freely. This nurtures their initiative, helps them develop problem-solving skills, and builds confidence and resilience.

By understanding the importance of exploration and providing the right support, caregivers can help children navigate this stage successfully and minimize feelings of guilt.

Stage 4. Industry vs. Inferiority

Erikson’s fourth psychosocial crisis, involving industry (competence) vs. Inferiority occurs during childhood between the ages of five and twelve. In this stage, children start to compare themselves with their peers to gauge their abilities and worth.

Industry : If children are encouraged by parents and teachers to develop skills, they gain a sense of industry—a feeling of competence and belief in their skills.

They start learning to work and cooperate with others and begin to understand that they can use their skills to complete tasks. This leads to a sense of confidence in their ability to achieve goals.

Inferiority : On the other hand, if children receive negative feedback or are not allowed to demonstrate their skills, they may develop a sense of inferiority.

They may start to feel that they aren’t as good as their peers or that their efforts aren’t valued, leading to a lack of self-confidence and a feeling of inadequacy.

The child is coping with new learning and social demands.

Children are at the stage where they will be learning to read and write, to do sums, and to do things on their own. Teachers begin to take an important role in the child’s life as they teach specific skills.

At this stage, the child’s peer group will gain greater significance and become a major source of the child’s self-esteem.

The child now feels the need to win approval by demonstrating specific competencies valued by society and develop a sense of pride in their accomplishments.

This stage typically occurs during the elementary school years, from approximately ages 6 to 11, and the experiences children have in school can significantly influence their development.

Here’s why:

Development of Industry : At school, children are given numerous opportunities to learn, achieve, and demonstrate their competencies. They work on various projects, participate in different activities, and collaborate with their peers.

These experiences allow children to develop a sense of industry, reinforcing their confidence in their abilities to accomplish tasks and contribute effectively.

Social Comparison : School provides a context where children can compare themselves to their peers.

They gauge their abilities and achievements against those of their classmates, which can either help build their sense of industry or lead to feelings of inferiority, depending on their experiences and perceptions.

Feedback and Reinforcement : Teachers play a crucial role during this stage. Their feedback can either reinforce the child’s sense of industry or trigger feelings of inferiority.

Encouraging feedback enhances the child’s belief in their skills, while persistent negative feedback can lead to a sense of inferiority.

Building Life Skills : School also provides opportunities for children to develop crucial life skills, like problem-solving, teamwork, and time management. Successfully acquiring and utilizing these skills promotes a sense of industry.

Dealing with Failure : School is where children may encounter academic difficulties or fail for the first time.

How they learn to cope with these situations— and how teachers and parents guide them through these challenges—can influence whether they develop a sense of industry or inferiority.

Success and Failure In Stage Four

Success leads to the virtue of competence , while failure results in feelings of inferiority .

If children are encouraged and reinforced for their initiative, they begin to feel industrious (competence) and confident in their ability to achieve goals.

If this initiative is not encouraged, if parents or teacher restricts it, then the child begins to feel inferior, doubting his own abilities, and therefore may not reach his or her potential.

If the child cannot develop the specific skill they feel society demands (e.g., being athletic), they may develop a sense of Inferiority.

Some failure may be necessary so that the child can develop some modesty. Again, a balance between competence and modesty is necessary.

The balance between industry and inferiority allows children to recognize their skills and understand that they have the ability to work toward and achieve their goals, even if they face challenges along the way.

How Can Parents & Teachers Encourage a Sense of Exploration?

In this stage, teachers and parents need to provide consistent, constructive feedback and encourage effort, not just achievement.

This approach helps foster a sense of industry, competence, and confidence in children, reducing feelings of inferiority.

Stage 5. Identity vs. Role Confusion

The fifth stage of Erik Erikson’s theory of psychosocial development is identity vs. role confusion, and it occurs during adolescence, from about 12-18 years. During this stage, adolescents search for a sense of self and personal identity, through an intense exploration of personal values, beliefs, and goals.

Identity : If adolescents are supported in their exploration and given the freedom to explore different roles, they are likely to emerge from this stage with a strong sense of self and a feeling of independence and control.

This process involves exploring their interests, values, and goals, which helps them form their own unique identity.

Role Confusion : If adolescents are restricted and not given the space to explore or find the process too overwhelming or distressing, they may experience role confusion.

This could mean being unsure about one’s place in the world, values, and future direction. They may struggle to identify their purpose or path, leading to confusion about their personal identity.

During adolescence, the transition from childhood to adulthood is most important. Children are becoming more independent and looking at the future regarding careers, relationships, families, housing, etc.

The individual wants to belong to a society and fit in.

Teenagers explore who they are as individuals, seek to establish a sense of self, and may experiment with different roles, activities, and behaviors.

According to Erikson, this is important to forming a strong identity and developing a sense of direction in life.

The adolescent mind is essentially a mind or moratorium, a psychosocial stage between childhood and adulthood, between the morality learned by the child and the ethics to be developed by the adult (Erikson, 1963, p. 245).

This is a major stage of development where the child has to learn the roles he will occupy as an adult. During this stage, the adolescent will re-examine his identity and try to find out exactly who he or she is.

Erikson suggests that two identities are involved: the sexual and the occupational.

Social Relationships

Given the importance of social relationships during this stage, it’s crucial for adolescents to have supportive social networks that encourage healthy exploration of identity.

It’s also important for parents, teachers, and mentors to provide guidance as adolescents navigate their social relationships and roles.

Formation of Identity : Social relationships provide a context within which adolescents explore different aspects of their identity.

They try on different roles within their peer groups, allowing them to discover their interests, beliefs, values, and goals. This exploration is key to forming their own unique identity.

Peer Influence : Peer groups often become a significant influence during this stage. Adolescents often start to place more value on the opinions of their friends than their parents.

How an adolescent’s peer group perceives them can impact their sense of self and identity formation.

Social Acceptance and Belonging : Feeling accepted and fitting in with peers can significantly affect an adolescent’s self-esteem and sense of identity.

They are more likely to develop a strong, positive identity if they feel accepted and valued. Feeling excluded or marginalized may lead to role confusion and a struggle with identity formation.

Experiencing Diversity : Interacting with a diverse range of people allows adolescents to broaden their perspectives, challenge their beliefs, and shape their values.

This diversity of experiences can also influence the formation of their identity.

Conflict and Resolution : Social relationships often involve conflict and the need for resolution, providing adolescents with opportunities to explore different roles and behaviors.

Learning to navigate these conflicts aids in the development of their identity and the social skills needed in adulthood.

Success and Failure In Stage Five

According to Bee (1992), what should happen at the end of this stage is “a reintegrated sense of self, of what one wants to do or be, and of one’s appropriate sex role”. During this stage, the body image of the adolescent changes.

Erikson claims adolescents may feel uncomfortable about their bodies until they can adapt and “grow into” the changes. Success in this stage will lead to the virtue of fidelity .

Fidelity involves being able to commit one’s self to others on the basis of accepting others, even when there may be ideological differences.

During this period, they explore possibilities and begin to form their own identity based on the outcome of their explorations.

Adolescents who establish a strong sense of identity can maintain consistent loyalties and values, even amidst societal shifts and changes.

Erikson described 3 forms of identity crisis:

- severe (identity confusion overwhelms personal identity)

- prolonged (realignment of childhood identifications over an extended time)

- aggravated (repeated unsuccessful attempts at resolution)

Failure to establish a sense of identity within society (“I don’t know what I want to be when I grow up”) can lead to role confusion.

However, if adolescents don’t have the support, time, or emotional capacity to explore their identity, they may be left with unresolved identity issues, feeling unsure about their roles and uncertain about their future.

This could potentially lead to a weak sense of self, role confusion, and lack of direction in adulthood.

Role confusion involves the individual not being sure about themselves or their place in society.

In response to role confusion or identity crisis , an adolescent may begin to experiment with different lifestyles (e.g., work, education, or political activities).

Also, pressuring someone into an identity can result in rebellion in the form of establishing a negative identity, and in addition to this feeling of unhappiness.

Stage 6. Intimacy vs. Isolation

Intimacy versus isolation is the sixth stage of Erik Erikson’s theory of psychosocial development. This stage takes place during young adulthood between the ages of approximately 18 to 40 yrs. During this stage, the major conflict centers on forming intimate, loving relationships with other people.

Intimacy : Individuals who successfully navigate this stage are able to form intimate, reciprocal relationships with others.

They can form close bonds and are comfortable with mutual dependency. Intimacy involves the ability to be open and share oneself with others, as well as the willingness to commit to relationships and make personal sacrifices for the sake of these relationships.

Isolation : If individuals struggle to form these close relationships, perhaps due to earlier unresolved identity crises or fear of rejection, they may experience isolation.

Isolation refers to the inability to form meaningful, intimate relationships with others. This could lead to feelings of loneliness, alienation, and exclusion.

Success and Failure In Stage Six

Success leads to strong relationships, while failure results in loneliness and isolation.

Successfully navigating this stage develops the virtue of love . Individuals who develop this virtue have the ability to form deep and committed relationships based on mutual trust and respect.

During this stage, we begin to share ourselves more intimately with others. We explore relationships leading toward longer-term commitments with someone other than a family member.

Successful completion of this stage can result in happy relationships and a sense of commitment, safety, and care within a relationship.

However, if individuals struggle during this stage and are unable to form close relationships, they may feel isolated and alone. This could potentially lead to a sense of disconnection and estrangement in adulthood.

Avoiding intimacy and fearing commitment and relationships can lead to isolation, loneliness, and sometimes depression.

Stage 7. Generativity vs. Stagnation

Generativity versus stagnation is the seventh of eight stages of Erik Erikson’s theory of psychosocial development. This stage takes place during during middle adulthood (ages 40 to 65 yrs). During this stage, individuals focus more on building our lives, primarily through our careers, families, and contributions to society.

Generativity : If individuals feel they are making valuable contributions to the world, for instance, through raising children or contributing to positive changes in society, they will feel a sense of generativity.

Generativity involves concern for others and the desire to contribute to future generations, often through parenting, mentoring, leadership roles, or creative output that adds value to society.

Stagnation : If individuals feel they are not making a positive impact or are not involved in productive or creative tasks, they may experience stagnation.

Stagnation involves feeling unproductive and uninvolved, leading to self-absorption, lack of growth, and feelings of emptiness.

Psychologically, generativity refers to “making your mark” on the world through creating or nurturing things that will outlast an individual.

During middle age, individuals experience a need to create or nurture things that will outlast them, often having mentees or creating positive changes that will benefit other people.

We give back to society by raising our children, being productive at work, and participating in community activities and organizations. We develop a sense of being a part of the bigger picture through generativity.

Work & Parenthood

Both work and parenthood are important in this stage as they provide opportunities for adults to extend their personal and societal influence.

Work : In this stage, individuals often focus heavily on their careers. Meaningful work is a way that adults can feel productive and gain a sense of contributing to the world.

It allows them to feel that they are part of a larger community and that their efforts can benefit future generations. If they feel accomplished and valued in their work, they experience a sense of generativity.

However, if they’re unsatisfied with their career or feel unproductive, they may face feelings of stagnation.

Parenthood : Raising children is another significant aspect of this stage. Adults can derive a sense of generativity from nurturing the next generation, guiding their development, and imparting their values.

Through parenthood, adults can feel they’re making a meaningful contribution to the future.

On the other hand, individuals who choose not to have children or those who cannot have children can also achieve generativity through other nurturing behaviors, such as mentoring or engaging in activities that positively impact the younger generation.

Success and Failure In Stage Seven

If adults can find satisfaction and a sense of contribution through these roles, they are more likely to develop a sense of generativity, leading to feelings of productivity and fulfillment.

Successfully navigating this stage develops the virtue of care . Individuals who develop this virtue feel a sense of contribution to the world, typically through family and work, and feel satisfied that they are making a difference.

Success leads to feelings of usefulness and accomplishment, while failure results in shallow involvement in the world.

We become stagnant and feel unproductive by failing to find a way to contribute. These individuals may feel disconnected or uninvolved with their community and with society as a whole.

This could potentially lead to feelings of restlessness and unproductiveness in later life.

Stage 8. Ego Integrity vs. Despair

Ego integrity versus despair is the eighth and final stage of Erik Erikson’s stage theory of psychosocial development. This stage begins at approximately age 65 and ends at death. It is during this time that we contemplate our accomplishments and can develop integrity if we see ourselves as leading a successful life.

Ego Integrity : If individuals feel they have lived a fulfilling and meaningful life, they will experience ego integrity.

This is characterized by a sense of acceptance of their life as it was, the ability to find coherence and purpose in their experiences, and a sense of wisdom and fulfillment.

Despair : On the other hand, if individuals feel regretful about their past, feel they have made poor decisions, or believe they’ve failed to achieve their life goals, they may experience despair.

Despair involves feelings of regret, bitterness, and disappointment with one’s life, and a fear of impending death.

This stage takes place after age 65 and involves reflecting on one’s life and either moving into feeling satisfied and happy with one’s life or feeling a deep sense of regret.

Erikson described ego integrity as “the acceptance of one’s one and only life cycle as something that had to be” (1950, p. 268) and later as “a sense of coherence and wholeness” (1982, p. 65).

As we grow older (65+ yrs) and become senior citizens, we tend to slow down our productivity and explore life as retired people.

Success and Failure In Stage Eight

Success in this stage will lead to the virtue of wisdom . Wisdom enables a person to look back on their life with a sense of closure and completeness, and also accept death without fear.

Individuals who reflect on their lives and regret not achieving their goals will experience bitterness and despair.

Erik Erikson believed if we see our lives as unproductive, feel guilt about our past, or feel that we did not accomplish our life goals, we become dissatisfied with life and develop despair, often leading to depression and hopelessness.

This could potentially lead to feelings of fear and dread about their mortality.

A continuous state of ego integrity does not characterize wise people, but they experience both ego integrity and despair. Thus, late life is characterized by integrity and despair as alternating states that must be balanced.

Strengths and Weaknesses of Erikson’s Theory

By extending the notion of personality development across the lifespan, Erikson outlines a more realistic perspective of personality development, filling a major gap in Freud’s emphasis on childhood. (McAdams, 2001).

- Based on Erikson’s ideas, psychology has reconceptualized how the later periods of life are viewed. Middle and late adulthood are no longer viewed as irrelevant, because of Erikson, they are now considered active and significant times of personal growth.

- Erikson’s theory has good face validity . Many people find they can relate to his theories about various life cycle stages through their own experiences.

Indeed, Erikson (1964) acknowledges his theory is more a descriptive overview of human social and emotional development that does not adequately explain how or why this development occurs.

For example, Erikson does not explicitly explain how the outcome of one psychosocial stage influences personality at a later stage.

Erikson also does not explain what propels the individual forward into the next stage once a crisis is resolved. His stage model implies strict sequential progression tied to age, but does not address variations in timing or the complexity of human development.

However, Erikson stressed his work was a ‘tool to think with rather than a factual analysis.’ Its purpose then is to provide a framework within which development can be considered rather than testable theory.

The lack of elucidation of the dynamics makes it challenging to test Erikson’s stage progression hypotheses empirically. Contemporary researchers have struggled to operationalize the stages and validate their universal sequence and age ranges.

Erikson based his theory of psychosocial development primarily on observations of middle-class White children and families in the United States and Europe. This Western cultural perspective may limit the universality of the stages he proposed.

The conflicts emphasized in each stage reflect values like independence, autonomy, and productivity, which are deeply ingrained in Western individualistic cultures. However, the theory may not translate well to more collectivistic cultures that value interdependence, social harmony, and shared responsibility.

For example, the autonomy vs. shame and doubt crisis in early childhood may play out differently in cultures where obedience and conformity to elders is prioritized over individual choice. Likewise, the identity crisis of adolescence may be less pronounced in collectivist cultures.

As an illustration, the identity crisis experienced in adolescence often resurfaces as adults transition into retirement (Logan, 1986). Although the context differs, managing similar emotional tensions promotes self-awareness and comprehension of lifelong developmental dynamics.

Applications

Retirees can gain insight into retirement challenges by recognizing the parallels between current struggles and earlier psychosocial conflicts.

Retirees often revisit identity issues faced earlier in life when adjusting to retirement. Although the contexts differ, managing similar emotional tensions can increase self-awareness and understanding of lifelong psychodynamics.

Cultural sensitivity can increase patient self-awareness during counseling. For example, nurses could use the model to help adolescents tackle identity exploration or guide older adults in finding purpose and integrity.

Recent research shows the ongoing relevance of Erikson’s theory across the lifespan. A 2016 study found a correlation between middle-aged adults’ sense of generativity and their cognitive health, emotional resilience, and executive function.

Interprofessional teams could collaborate to create stage-appropriate, strengths-based care plans. For instance, occupational therapists could engage nursery home residents in reminiscence therapy to increase ego integrity.

Specific tools allow clinicians to identify patients’ current psychosocial stage. Nurses might use Erikson’s Psychosocial Stage Inventory (EPSI) to reveal trust, autonomy, purpose, or despair struggles.

With this insight, providers can deliver targeted interventions to resolve conflicts and support developmental advancement. For example, building autonomy after a major health crisis or fostering generativity by teaching parenting skills.

Erikson vs Maslow

How does Maslow’s hierarchy of needs differ from Erikson’s stages of psychosocial development?

Erikson vs Freud

Freud (1905) proposed a five-stage model of psychosexual development spanning infancy to puberty, focused on the maturation of sexual drives. While groundbreaking, Freud’s theory had limitations Erikson (1958, 1963) aimed to overcome.

- Erikson expanded the timeline through the full lifespan, while Freud focused only on the first few years of life. This more holistic perspective reflected the ongoing social challenges confronted into adulthood and old age.

- Whereas Freud highlighted biological, pleasure-seeking drives, Erikson incorporated the influence of social relationships, culture, and identity formation on personality growth. This broader psychosocial view enhanced realism.

- Erikson focused on the ego’s growth rather than the primacy of the id. He saw personality developing through negotiation of social conflicts rather than only frustration/gratification of innate drives.

- Erikson organized the stages around psychosocial crises tied to ego maturation rather than psychosexual erogenous zones. This reformulation felt more relevant to personal experiences many could identify with.

- Finally, Erikson emphasized healthy progression through the stages rather than psychopathology stemming from fixation. He took a strengths-based perspective focused on human potential.

Summary Table

Like Freud and many others, Erik Erikson maintained that personality develops in a predetermined order, and builds upon each previous stage. This is called the epigenetic principle.

Erikson’s eight stages of psychosocial development include:

Bee, H. L. (1992). The developing child . London: HarperCollins.

Brown, C., & Lowis, M. J. (2003). Psychosocial development in the elderly: An investigation into Erikson’s ninth stage. Journal of Aging Studies, 17 (4), 415–426.

Erikson, E. H. (1950). Childhood and society . New York: Norton.

Erickson, E. H. (1958). Young man Luther: A study in psychoanalysis and history . New York: Norton.

Erikson, E. H. (1963). Youth: Change and challenge . New York: Basic books.

Erikson, E. H. (1964). Insight and responsibility . New York: Norton.

Erikson, E. H. (1968). Identity: Youth and crisis . New York: Norton.

Erikson E. H . (1982). The life cycle completed . New York: W.W. Norton & Company.

Erikson, E. H. (1959). Psychological issues . New York, NY: International University Press

Fadjukoff, P., Pulkkinen, L., & Kokko, K. (2016). Identity formation in adulthood: A longitudinal study from age 27 to 50. Identity , 16 (1), 8-23.

Freud, S. (1905). Three essays on the theory of sexuality. Standard Edition 7 : 123- 246.

Freud, S. (1923). The ego and the id . SE, 19: 1-66.

Gross, R. D., & Humphreys, P. (1992). Psychology: The science of mind and behavior . London: Hodder & Stoughton.

Logan , R.D . ( 1986 ). A reconceptualization of Erikson’s theory: The repetition of existential and instrumental themes. Human Development, 29 , 125 – 136.

Malone, J. C., Liu, S. R., Vaillant, G. E., Rentz, D. M., & Waldinger, R. J. (2016). Midlife Eriksonian psychosocial development: Setting the stage for late-life cognitive and emotional health. Developmental Psychology , 52 (3), 496.

McAdams, D. P. (2001). The psychology of life stories . Review of General Psychology , 5(2), 100.

McCrae, R. R., & Costa Jr, P. T. (1997). Personality trait structure as a human universal . American Psychologist, 52(5) , 509.

Meeus, W., van de Schoot, R., Keijsers, L., & Branje, S. (2012). Identity statuses as developmental trajectories: A five-wave longitudinal study in early-to-middle and middle-to-late adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence , 41 , 1008-1021.

Osborne, J. W. (2009). Commentary on retirement, identity, and Erikson’s developmental stage model. Canadian Journal on Aging/La Revue canadienne du vieillissement , 28 (4), 295-301.

Rosenthal, D. A., Gurney, R. M., & Moore, S. M. (1981). From trust on intimacy: A new inventory for examining Erikson’s stages of psychosocial development. Journal of Youth and Adolescence , 10 (6), 525-537.

Sica, L. S., Aleni Sestito, L., Syed, M., & McLean, K. (2018). I became adult when… Pathways of identity resolution and adulthood transition in Italian freshmen’s narratives. Identity , 18 (3), 159-177.

Vogel-Scibilia, S. E., McNulty, K. C., Baxter, B., Miller, S., Dine, M., & Frese, F. J. (2009). The recovery process utilizing Erikson’s stages of human development. Community Mental Health Journal , 45 , 405-414.

What is Erikson’s main theory?

Erikson said that we all want to be good at certain things in our lives. According to psychosocial theory, we go through eight developmental stages as we grow up, from being a baby to an old person. In each stage, we have a challenge to overcome.

If we do well in these challenges, we feel confident, our personality grows healthily, and we feel competent. But if we don’t do well, we might feel like we’re not good enough, leading to feelings of inadequacy.

What is an example of Erikson’s psychosocial theory?

Throughout primary school (ages 6-12), children encounter the challenge of balancing industry and inferiority. During this period, they start comparing themselves to their classmates to evaluate their own standing.

As a result, they may either cultivate a feeling of pride and achievement in their academics, sports, social engagements, and family life or experience a sense of inadequacy if they fall short.

Parents and educators can implement various strategies and techniques to support children in fostering a sense of competence and self-confidence.

Related Articles

Child Psychology

Vygotsky vs. Piaget: A Paradigm Shift

Interactional Synchrony

Internal Working Models of Attachment

Freudian Psychology

Attachment Theory and Psychoanalysis

Soft Determinism In Psychology

Branches of Psychology

- Tools and Resources

- Customer Services

- Affective Science

- Biological Foundations of Psychology

- Clinical Psychology: Disorders and Therapies

- Cognitive Psychology/Neuroscience

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational/School Psychology

- Forensic Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems of Psychology

- Individual Differences

- Methods and Approaches in Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational and Institutional Psychology

- Personality

- Psychology and Other Disciplines

- Social Psychology

- Sports Psychology

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Article contents

Identity development in adolescence and adulthood.

- Jane Kroger Jane Kroger Department of Psychology, University of Tromsoe

- https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190236557.013.54

- Published online: 27 February 2017

Psychoanalyst Erik Erikson was the first professional to describe and use the concept of ego identity in his writings on what constitutes healthy personality development for every individual over the course of the life span. Basic to Erikson’s view, as well as those of many later identity writers, is the understanding that identity enables one to move with purpose and direction in life, and with a sense of inner sameness and continuity over time and place. Erikson considered identity to be psychosocial in nature, formed by the intersection of individual biological and psychological capacities in combination with the opportunities and supports offered by one’s social context. Identity normally becomes a central issue of concern during adolescence, when decisions about future vocational, ideological, and relational issues need to be addressed; however, these key identity concerns often demand further reflection and revision during different phases of adult life as well. Identity, thus, is not something that one resolves once and for all at the end of adolescence, but rather identity may continue to evolve and change over the course of adult life too.

Following Erikson’s initial writings, subsequent theorists have laid different emphases on the role of the individual and the role of society in the identity formation process. One very popular elaboration of Erikson’s own writings on identity that retains a psychosocial focus is the identity status model of James Marcia. While Erikson had described one’s identity resolution as lying somewhere on a continuum between identity achievement and role confusion (and optimally located nearer the achievement end of the spectrum), Marcia defined four very different means by which one may approach identity-defining decisions: identity achievement (commitment following exploration), moratorium (exploration in process), foreclosure (commitment without exploration), and diffusion (no commitment with little or no exploration). These four approaches (or identity statuses) have, over many decades, been the focus of over 1,000 theoretical and research studies that have examined identity status antecedents, behavioral consequences, associated personality characteristics, patterns of interpersonal relations, and developmental forms of movement over time. A further field of study has focused on the implications for intervention that each identity status holds. Current research seeks both to refine the identity statuses and explore their dimensions further through narrative analysis.

- identity status

- identity formation

- adolescence

Introduction

We know what we are, but not what we may be . Shakespeare, Hamlet

The question of what constitutes identity has been answered differently through different historical epochs and through different theoretical and empirical approaches to understanding identity’s form and functions. However, basic to all identity definitions is an attempt to understand the entity that, ideally, enables one to move with purpose and direction in life and with a sense of internal coherence and continuity over time and place. Despite the changing physique that aging inevitably brings and the changing environmental circumstances that one invariably encounters through life, a well-functioning identity enables one to experience feelings of personal meaning and well-being and to find satisfying and fulfilling engagements in one’s social context. The means by which one experiences a feeling of sameness in the midst of continual change is the focus of identity theory and research.

Historically, concerns with questions of identity are relatively recent. Baumeister and Muraven ( 1996 ) and Burkitt ( 2011 ) have noted how changes in Western society, specifically the degree to which society has dictated one’s adult roles, have varied enormously over time. Additional changes have occurred in the loosening of social guidelines, restrictions, and constraints, such that contemporary late adolescents experience almost unlimited freedom of choice in their assumption of adult roles and values. In Medieval times, adolescents and adults were prescribed an identity by society in a very direct manner. Social rank and the kinship networks into which one was born set one’s adult roles for life. In early modern times, wealth rather than kinship networks became the standard for self-definition. In the first half of the twentieth century , apprenticeship systems that prepared adolescents for one specific line of work were giving way to more liberal forms of education, thus preparing adolescents for a broad range of occupational pathways. A more liberal educational system, however, eventually required occupational choice in line with one’s own interests and capacities. In addition, many regions in the United States became more tolerant of diversity in attitudes and values, and gender roles became more fluid. Thus, by the middle of the twentieth century in the United States and many other Western nations, the burden of creating an adult identity was now falling largely on the shoulders of late adolescents themselves.

Into this twentieth century United States context came Erik Erikson, a German immigrant (escaping Hitler’s rise to power) and psychoanalyst, trained by Anna Freud. Erikson began his clinical work and writings on optimal personality development in the Boston area, focusing, in particular, on the concept of identity and identity crisis . As an immigrant, Erikson was acutely attuned to the role of the social context and its influence on individual personality development, and, as a psychoanalyst, he was also adept at understanding the roles of conscious as well as unconscious motivations, desires, and intentions, as well as biological drives on individual behavior.

Erikson ( 1963 ) first used the term “ego identity” to describe a central disturbance among some of his veteran patients returning from World War II with a diagnosis of “shell shock” (or currently, post-traumatic stress disorder), who seemed to be experiencing a loss of self-sameness and continuity in their lives:

What impressed me most was the loss in these men of a sense of identity. They knew who they were; they had a personal identity. But it was as if subjectively, their lives no longer hung together—and never would again. There was a central disturbance in what I then started to call ego identity. (Erikson, 1963 , p. 42)

Through identity’s absence in the lives of these young men, Erikson came to understand the tripartite nature of identity, that he believed to be comprised of biological, psychological, and social factors. It was often a particular moment in a soldier’s life history where soma, psyche, and society conspired to endanger identity foundations that necessitated clinical care. And, thus, it was through disruptions to individual identity that Erikson more clearly came to understand identity’s form and functions.

Erikson has often been referred to as “identity’s architect” (e.g., Friedman, 1999 ), and his initial writings on identity served as the springboard for many later theorists and researchers to examine further identity’s many dimensions. Erikson’s psychosocial approach will thus serve as the organizing framework for a review of research on identity development during adolescent and adult life.

Erikson’s Psychosocial Orientation

Erikson’s ( 1963 , 1968 ) understanding of identity views the phenomenon as a result of the mutual interaction of individual and context; while individual interests and capacities, wishes and desires draw individuals to particular contexts, those contexts, in turn, provide recognition (or not) of individual identity and are critical to its further development. Erikson stressed the important interactions among the biological, psychological, and social forces for optimal personality development. He suggested a series of eight psychosocial tasks over the course of the life span that follow an epigenetic principle, such that resolution to one task sets the foundation for all that follow. Identity vs. Role Confusion is the fifth psychosocial task that Erikson identified, becoming of primary importance during adolescence. Resolution to preceding tasks of Trust vs. Mistrust, Autonomy vs. Doubt and Shame, Initiative vs. Guilt, Industry vs. Inferiority are the foundations upon which one’s resolution to Identity vs. Role Confusion is based, according to Erikson; resolution to subsequent adult tasks of Intimacy vs. Role Confusion, Generativity vs. Stagnation, and Integrity vs. Despair all similarly depend upon resolution to the Identity vs. Role Confusion task of adolescence.

Erikson ( 1963 , 1968 ) postulated a number of key identity concepts that have served as foundations for much subsequent identity research. For Erikson, identity formation involves finding a meaningful identity direction on a continuum between identity attainment and role confusion . The process of identity formation requires identity exploration and commitment , the synthesis of childhood identifications into a new configuration, related to but different from, the sum of its parts. The identity formation process is extremely arduous for some, and the resolutions of a negative identity or identity foreclosure are two means by which the identity formation process can be bypassed. A negative identity involves identity choices based on roles and values that represent polar opposites of those espoused by one’s family and/or immediate community. Thus, the daughter of a Midwestern minister of religion runs away to become a prostitute in inner city Chicago. A foreclosed identity resolution also avoids the identity formation process by basing identity-defining choices on key identifications, mostly with parental values, without exploring potential alternatives.

Erikson ( 1963 , 1968 ) also proposed several further concepts for optimal identity development. A moratorium process, the active consideration and exploration of future possible identity-defining adult roles and values, was considered vital to optimal identity development. Erikson also became well known for his use of the term identity crisis , an acute period of questioning one’s own identity directions. And finally, Erikson stressed that while an initial resolution to the Identity vs. Role Confusion task often occurs during adolescence, identity is never resolved once and for all, but rather remains open to modifications and alterations throughout adult life. The strength of Erikson’s approach lies in its consideration of both individual and sociocultural factors and their mutual interaction in identity construction and development. Erikson’s model of identity development has wide applicability across cultural contexts and highlights the ongoing nature of identity development throughout adulthood. Weaknesses include his imprecise language, which at times makes operationalization of key concepts difficult, and his historically dated concepts regarding women’s identity development.

While other psychosocial models have evolved from Erikson’s original writings (e.g., Whitbourne’s [ 2002 ] identity processing theory, Berzonsky’s [ 2011 ] social cognitive identity styles, McAdams’s [ 2008 ] narrative approach), it is Erikson’s identity formation concepts, particularly those operationalized by Marcia ( 1966 ) (Marcia, Waterman, Matteson, Archer, & Orlofsky, 1993 ) that have generated an enormous volume of empirical research over past decades and will be the primary focus of subsequent sections of this article.

Erikson’s Psychosocial Approach and Marcia’s Identity Status Model

As a young Ph.D. student in clinical psychology, James Marcia was interested in Erikson’s writings but suspected that the process of identity formation during late adolescence to be somewhat more complicated than what Erikson ( 1963 ) had originally proposed. While Erikson had conceptualized an identity resolution as lying on a continuum between identity and role confusion, an entity that one had “more or less of,” Marcia proposed that there were four qualitatively different pathways by which late adolescents or young adults went about the process of forming an identity. Based on the presence or absence of exploration and commitment around several issues important to identity development during late adolescence, Marcia ( 1966 ; Marcia et al., 1993 ) developed a semi-structured Identity Status Interview to identify four identity pathways, or identity statuses, among late adolescent or young adult interviewees.

An individual in the identity achieved status had explored various identity-defining possibilities and had made commitments on his or her own terms, trying to match personal interests, talents, and values with those available in the environmental context. Equally committed to an identity direction was the foreclosed individual, who had formed an identity, but without undergoing an exploration process. This person’s identity had been acquired primarily through the process of identification—by assuming the identity choices of significant others without serious personal consideration of alternative possibilities. An individual in the moratorium identity status was very much in the process of identity exploration, seeking meaningful life directions but not yet making firm commitments and often experiencing considerable discomfort in the process. Someone in the diffusion identity status had similarly not made identity-defining commitments and was not attempting to do so.

Marcia et al.’s ( 1993 ) Identity Status Interview was designed to tap the areas (or domains) of occupation, political, religious, and sexual values that had been described by Erikson as key to the identity formation process. In Marcia’s view, however, the nature of the identity domain was not as critical to the assessment of identity status as was finding the identity-defining issues most salient to any given individual. Marcia suggested the use of clinical judgment in assigning a global identity status, the mode that seemed to best capture an adolescent’s identity formation process. It must be noted that Marcia and his colleagues (Marcia et al., 1993 ) have never attempted to capture all of the rich dimensions of identity outlined by Erikson through the Identity Status Interview; such a task would be unwieldy, if not impossible. Marcia does, however, build on Erikson’s concepts of identity exploration and comment to elaborate these identity dimensions in relation to those psychosocial roles and values identified by Erikson as key to the identity formation process of many late adolescents.

Subsequent to the original Identity Status Interview, several paper-and-pencil measures were developed to assess Marcia’s four identity statuses. One widely used measure has been the Extended Objective Measure of Ego Identity Status (EOM-EIS II), devised and revised through several versions by Adams and his colleagues (Adams, Bennion, & Huh, 1989 ; Adams & Ethier, 1999 ). This questionnaire measure enables identity status assessments in four ideological (occupation, religion, politics, philosophy of life) and four interpersonal domains (friendships, dating, gender roles, recreation/leisure), as well as providing a global rating.

Different dimensions of identity exploration and commitment processes have also been identified through several recent and expanded identity status models (Luyckx, Goossens, Soenens, & Beyers, 2006 ; Crocetti, Rubini, & Meeus, 2008 ). Luyckx and his colleagues differentiated two types of exploration (exploration in breadth and exploration in depth) and two types of commitment (commitment making and identification with commitment). Exploration in breadth is that moratorium process identified by Marcia, while exploration in depth describes the process of considering a commitment already made and how well it expresses one’s own identity. Commitment making refers to deciding an identity-defining direction, while identification with commitment describes the process of integrating one’s commitments into an internal sense of identity. Later, Luyckx and his colleagues (Luyckx, Schwartz, Berzonsky, Soenens, Vansteenkiste, Smits, et al., 2008 ) also identified a process of ruminative exploration.

Meeus and his colleagues (e.g., Crocetti, Rubini, & Meeus, 2008 ) also identified three identity processes: commitment, exploration in depth, and reconsideration of commitments. Commitment here refers to the dimensions of commitment making and identification with commitment in the Luyckx, Goossens, Soenens, and Beyers ( 2006 ) model; exploration in depth corresponds to that dimension in the Luyckx model. Reconsideration of commitment refers to one’s willingness to replace current commitments with new ones. In this model, commitment and reconsideration reflect identity certainty and uncertainty, respectively, in the identity formation process.

Through cluster analysis, these two groups of researchers have extracted clusters that match all of Marcia’s original identity statuses. In addition, Luyckx and his colleagues (Luyckx, Goossens, Soenens, Beyers, & Vansteenkiste, 2005 ) identified two types of diffusion—troubled and carefree—while Meeus, van de Schoot, Keijsers, Schwartz, and Branje ( 2010 ) found two types of moratoriums—classical (where the individual exhibits anxiety and depression in the identity exploration process) and searching (where new commitments are considered without discarding present commitments). Work has now begun to explore the identity formation process during adolescence and young adulthood with these refined identity statuses, which hold interesting implications for understanding both adaptive and non-adaptive identity development.

Over the time since Marcia’s initial studies, the identity statuses have been examined in relation to personality and behavioral correlates, relationship styles, and developmental patterns of change over time. Most of the studies reviewed in subsequent sections address some aspect of identity development during adolescence or young adulthood; a later section will focus on identity development research during adulthood. It must be further noted that discussion of identity statuses here will be limited to general (or global) identity and its relationship to associated variables.

Personality and Behavioral Correlates of the Identity Statuses

Work utilizing Marcia’s original identity status model, as well as its more recent refinements, have focused on personality and behavioral variables associated with each identity status in order to help validate the model; such studies have produced some reasonably consistent results over time. In terms of personality variables associated with the identity statuses, Kroger and her colleagues (e.g., Martinussen & Kroger, 2013 ) have produced a series of findings utilizing techniques of meta-analysis. Meta-analysis is a “study of studies,” using statistical procedures to examine (sometimes contradictory) results from different individual studies addressing comparable themes over time. Results from such meta-analytic studies allow greater confidence in results than a narrative review of individual studies can provide. The personality variables of self-esteem, anxiety, locus of control, authoritarianism, moral reasoning, and ego development and their relations to identity status have attracted sufficient studies for meta-analyses to be undertaken and are described in the sections that follow. While a number of other personality variables have also been examined in identity status studies over the past decades, their numbers have been insufficient to enable meta-analytic studies.

An initial database for all studies included in the meta-analytic work described in the following sections was comprised of some 565 English-language studies (287 journal publications and 278 doctoral dissertations) identified from PsycInfo, ERIC, Sociological Abstracts, and Dissertation Abstracts International databases, using the following search terms: identity and Marcia, identity and Marcia’s, and ego identity. Cohen’s ( 1988 ) criteria were used to define small, medium, and large effect sizes. In some of the meta-analyses that follow, different methods were used to assess identity status (categorical ratings of identity status and scale measures of identity status). Separate meta-analyses had to be undertaken for studies utilizing each of these two types of identity status assessments for statistical reasons.

Self-Esteem

Ryeng, Kroger, and Martinussen ( 2013a ) undertook meta-analytic studies of the relationship between identity status and global self-esteem. A total of twelve studies with 1,124 participants provided the data for these studies. The achieved identity status was the only status to have a positive correlation with self-esteem ( r = .35), considered to be moderate in effect size. Mean correlations between self-esteem and the moratorium, foreclosure, and diffusion statuses were all negative (−.23, −.23, and −.20, respectively) and considered small to moderate in effect size. All of these correlations were significantly different from zero, based on their confidence intervals. When identity status was assessed categorically, there was no difference in effect size between achievements and foreclosures on self-esteem measures. The effect size for the foreclosure-diffusion comparison ( g̅ = −0.19) was small to medium and also significant. Remaining comparisons evidenced small effect size differences in self-esteem scores. Findings here were mixed, as previous research had also produced mixed results on the question of whether foreclosure self-esteem scores would be lower than or similar to those of the identity achieved. Here, results show that only the achieved status (when the identity statuses were measured by continuous scales) produced a moderately positive correlation with self-esteem, while there was no difference in effect sizes between the achieved and foreclosed identity status when studies assessing identity status categorically were analyzed. Thus, the relationship between identity status and self-esteem may depend upon how identity status is measured.

Lillevoll, Kroger, and Martinussen ( 2013a ) examined the relationship between identity status and generalized anxiety through meta-analysis. Twelve studies involving 2,104 participants provided data for this investigation. Effect size differences in anxiety scores for moratoriums compared with foreclosures ( g̅ = 0.39) and for the foreclosure–diffusion comparison ( g̅ = −0.40) were small to moderate. Additionally the confidence intervals for both of these effect sizes did not contain zero, indicating a significant result. A significant moderate effect size ( g̅ = 0.46) was also found in the achievement–foreclosure comparison, but for men only. As predicted, foreclosures had lower anxiety scores compared with all other identity statuses except the achievement women. While it was predicted that those in the achievement identity status would have lower anxiety scores than those in moratorium and diffusion statuses, a small but significant effect size difference was found for the achievement–moratorium comparison only ( g̅ = −0.22). Thus, the moratoriums showed higher generalized anxiety scores than foreclosures, who, in turn, showed lower anxiety scores than the diffusions and male achievements. It appears that unexamined identity commitments undertaken by the foreclosures provided relief from the anxieties and uncertainties of uncommitted identity directions experienced by the moratoriums and diffusions.

Locus of Control

Lillevoll, Kroger, and Martinussen ( 2013b ) examined the relationship between identity status and locus of control. Some five studies with a total of 711 participants provided data for this study. A positive correlation between identity achievement and internal locus of control ( r = .26) and a negative correlation between identity achievement and external locus of control ( r = −.17) was found; these effect sizes are considered small to medium. The moratorium identity status was negatively correlated with internal locus of control ( r = −.17) and positively with an external locus of control ( r = .17), both considered small to medium effect sizes. The foreclosure status was negatively correlated the internal locus of control ( r = −.12) and positively with external locus of control ( r = .19), both considered small to medium effect sizes. The diffusions’ status was negatively correlated with internal locus of control ( r = −.15) and positively with external locus of control ( r = .23), both considered small to medium effect sizes. Apart from the moratorium findings, which were anticipated to reflect an internal locus of control, all other results were in expected directions. It appears that the ability to undertake identity explorations on one’s own terms by the identity achieved is associated with an internal locus of control. Moratorium, foreclosure, and diffusion statuses are associated with an external locus of control.

Authoritarianism

The relationship between identity status and authoritarianism was investigated by Ryeng, Kroger, and Martinussen ( 2013b ) through meta-analysis. Some nine studies involving 861 participants provided data for this study. The mean difference between authoritarianism scores for the achievement—foreclosure comparison ( g̅ = −0.79) was large in terms of Cohen’s criteria and significant. The mean difference in authoritarianism scores for the moratorium–foreclosure comparison ( g̅ = −0.67) was medium and significant, while the mean difference in authoritarianism scores for the foreclosure and diffusion identity statuses was medium ( g̅ = 0.42) and significant. Other comparisons were relatively small and not significant. That the foreclosures scored higher on authoritarianism than all other identity statuses is consistent with expectations. Foreclosures often base their identity commitments on their identifications with significant others, rather than exploring identity options on their own terms; thus, the rigidity and intolerance of authoritarian attitudes seem to characterize the terms of their identity commitments, in contrast to the more flexible commitments of the identity achieved or moratoriums in the process of finding their own identity directions.

Ego Development

Jespersen, Kroger, and Martinussen ( 2013a ) examined studies utilizing Loevinger’s ( 1976 ) measure of ego development in relation to the identity statuses through meta-analysis. Eleven studies involving 943 participants provided data for this investigation. Odds ratios (OR) were used to examine frequency distributions of the categorical data. Results of correlational studies showed a moderate, positive relationship between ego development and identity status ( r = .35), which was significant. Results from categorical assessments of identity status also showed a strong relationship between identity status and ego development (mean OR = 3.02). This finding means that the odds of being in a postconformist level of ego development were three times greater for those high in identity statuses (achievement and moratorium) compared with those in the low identity statuses (foreclosure and diffusion). The study also found a moderate relationship between identity achievement and ego development (mean OR = 2.15), meaning that the odds of being in a postconformist level of ego development were over two times greater for those in the identity achievement status than remaining identity statuses. However, no relationship was found between the foreclosed/nonforeclosed identity statuses and the conformist/nonconformist levels of ego development, contrary to prediction (mean OR = 1.31). While results indicate a strong likelihood of being in a post-conformist level of ego development for the identity achieved and moratoriums, as one would predict, it is somewhat surprising that the foreclosure status was not associated with conventional levels of ego development. This lack of association requires further investigation.

Moral Reasoning

A meta-analysis of moral reasoning stages (using Kohlberg’s [ 1976 ] stages in relation to the identity statuses) was also undertaken by Jespersen, Kroger, and Martinussen ( 2013b ). Some ten studies involving 884 participants provided data appropriate for this study. Results showed a small positive mean correlation (.15) between identity status and moral reasoning development, which was significant. Results from categorical assessments of both measures indicated a strong relationship between high identity status (achievement and moratorium) and postconventional levels of moral reasoning (mean OR = 4.57). This result means that the odds of being in the postconventional level of moral reasoning are about four and a half times greater for the high identity status group (achievement and moratorium) than the low (foreclosure and diffusion) group. A strong relationship was also found between the achieved identity status and the postconventional level of moral reasoning (mean OR = 8.85), meaning that the odds of being in a postconventional level of moral reasoning were almost nine times greater for the identity achieved than for other identity statuses. However, no significant relationship appeared for the foreclosed/nonforeclosed identity statuses and the conventional/nonconventional levels of moral reasoning, contrary to prediction. While a meaningful relationship was found between postconventional stages of moral reasoning and the moratorium and achievement identity statuses, it is again surprising that no relationship appeared for the foreclosed identity status and conventional levels of moral reasoning. This finding warrants further investigation.

Additional Personality and Behavioral Variables

A number of additional personality and behavioral variables have been explored in relation to the identity statuses, but no further meta-analyses have yet been undertaken. With regard to the newer, more refined measures of identity status, some additional personality and behavioral associations have been noted. Luyckx et al. ( 2008 ) found ruminative exploration related to identity distress and low self-esteem, while exploration in breadth and depth were positively related to self-reflection. Furthermore, commitment-making (particularly identification with commitment) was associated with high self-esteem, high academic and social adjustment, as well as with low depressive symptoms. Crocetti et al. ( 2008 ) similarly found strong, positive associations between commitment and self-concept clarity, in addition to strong negative associations between in-depth exploration and reconsideration of commitment with self-reflection. Emotional stability was strongly associated with commitment and negatively with in-depth exploration.

Recent work has performed cluster analyses on the exploration and commitment variables, finding four clusters replicating Marcia’s four identity statuses (with the diffusion status including carefree and diffuse diffusions) and an undifferentiated status (Schwartz et al., 2011 ). In terms of psychosocial functioning, achievements were significantly higher than carefree diffusions on a measure of self-esteem; diffusions, in turn, were significantly lower than all other identity statuses on this variable. On a measure of internal locus of control, achievements and moratoriums were significantly higher and carefree diffusions significantly lower than all other identity statuses. On psychological well-being, identity achievements scored significantly higher and carefree diffusions significantly lower than all other identity status groups. For general anxiety, moratoriums and the two diffusion groups scored significantly higher than achievement and foreclosure groups, while the moratoriums scored significantly higher than foreclosures and the two diffusions groups on depression. These findings are generally in line with findings of earlier studies using Marcia’s original model.

Further behavioral studies in relation to the identity statuses have consistently found the identity diffusion status to be related to psychosocial problem behaviors. Delinquent behavior (e.g., Jessor, Turbin, Costa, Dong, Zhang, & Wang, 2003 ; Schwartz, Pantin, Prado, Sullivan, & Szapocznik, 2005 ), substance abuse (e.g., Jones & Hartmann, 1988 ; Laghi, Baiocco, Longiro, & Baumgartner, 2013 ), risky behaviors (e.g., unsafe sex, Hernandez & DiClemente, 1992 ), social, physical aggression, and rule-breaking (carefree diffusions, Schwartz et al., 2011 ), and procrastination (Shanahan & Pychyl, 2006 ) have all been linked with the identity diffusion status. By contrast, the identity achieved have demonstrated a low prevalence of all preceding problem behaviors, coupled with high levels of agency or self-direction and commitment making (e.g., Schwartz et al., 2011 ; Shanahan & Pychyl, 2006 ). Moratoriums have also scored relatively high on levels of social and physical aggression, although they have also scored high on a number of psychosocial measures of well-being (e.g., Schwartz et al., 2011 ).

Relationships and the Identity Statuses

While a number of relational issues have been explored in identity status research (e.g., parental attitudes toward childrearing, family styles of communication, and friendship styles), to date, meta-analyses have been undertaken to examine identity status only in relation to attachment patterns and intimacy or romantic relationships.

Bartholomew and Horowitz ( 1991 ) have proposed that one’s very unique attachment history and subsequent working models of attachment lead to one of four different adolescent/adult attachment styles, or patterns of relating to significant others; these attachment styles become activated particularly in times of stress. S ecurely attached individuals are at ease in becoming close to others and do not worry about being abandoned or having someone become too close to them. Furthermore, they are interdependent—comfortable depending on others and having others depend on them. Those using the avoidant attachment style find it difficult to trust and depend on others and are uncomfortable in becoming too emotionally close. The preoccupied (anxious/ambivalent) attachment group wants to be close to others but worries that others will not reciprocate and will abandon them, while the fearful attachment group wants to be emotionally close to others but are too frightened of being hurt to realize this desire.