- Speech Crafting →

How to Write an Informative Speech Outline: A Step-by-Step Guide

It’s the moment of truth — the anxiety-inducing moment when you realize writing the outline for your informative speech is due soon. Whether you’re looking to deliver a report on the migratory patterns of the great white stork or give a lecture on the proper techniques of candle making, knowing how to write an effective outline is essential.

That’s why we’ve put together this complete, step-by-step guide on how to write an informative speech outline. From selecting a topic to transitioning during your speech, this guide will have you well on your way to writing a compelling informative speech outline . So grab your pen and paper, put on your thinking cap, and let’s get started!

What is an Informative Speech Outline?

An informative speech outline is a document used to plan the structure and core content of a public speech. It’s used by speakers to ensure their talk covers all the important points, stays on-topic and flows logically from one point to another. By breaking down complex topics into smaller, concise sections, an effective outline can help keep a speaker organized, set objectives for their talk, support key points with evidence and promote audience engagement. A well-structured outline can also make a presentation easier to remember and act as an invaluable reminder if nerves ever get the better of the speaker. On one hand, an informative speech outline enables speakers to cover multiple ideas in an efficient manner while avoiding digressions. On the other hand, it’s important that speakers remain flexible to adjust and adapt content to meet audience needs. While there are some tried-and-tested strategies for creating outlines that work, many successful speakers prefer to tweak and modify existing outlines according to their personal preferences. In conclusion, preparing an informative speech outline can boost confidence and create an effective structure for presentations. With this in mind, let’s now look at how to structure an informative speech outline

How to Structure an Informative Speech Outline

The structure of your informative speech outline should be based on the points you need to cover during your presentation. It should list out all of the main points in an organized and logical manner, along with supporting details for each point. The main structure for an informative speech should consist of three parts: the introduction, body and conclusion.

Introduction

When starting to craft your structure, begin by introducing the topic and giving a brief synopsis of what the audience can expect to learn from your speech. By setting up what they will gain from your presentation, it will help keep them engaged throughout the rest of your talk. Additionally, include any objectives that you want to achieve by the end of your speech.

The body of an informative speech outline typically consists of three parts: main points, sub-points, and supporting details. Main points are the core topics that the speaker wishes to cover throughout the speech. These can be further broken down into sub-points, that explore the main ideas in greater detail. Supporting details provide evidence or facts about each point and can include statistics, research studies, quotes from experts, anecdotes and personal stories . When presenting an informative speech, it is important to consider each side of the topic for an even-handed discussion. If there is an argumentative element to the speech, consider incorporating both sides of the debate . It is also important to be objective when presenting facts and leave value judgments out. Once you have determined your main points and all of their supporting details, you can start ordering them in a logical fashion. The presentation should have a clear flow and move between points smoothly. Each point should be covered thoroughly without getting overly verbose; you want to make sure you are giving enough information to your audience while still being concise with your delivery.

Writing an informative speech outline can be a daunting yet rewarding process. Through the steps outlined above, speakers will have created a strong foundation for their speech and can now confidently start to research their topics . The outline serves as a guiding map for speakers to follow during their research and when writing their eventual speech drafts . Having the process of developing an informative speech broken down into easy and manageable steps helps to reduce stress and anxiety associated with preparing speeches .

- The introduction should be around 10-20% of the total speech duration and is designed to capture the audience’s attention and introduce the topic.

- The main points should make up 40-60% of the speech and provide further detail into the topic. The body should begin with a transition, include evidence or examples and have supporting details. Concluding with a recap or takeaway should take around 10-20% of the speech duration.

While crafting an informative speech outline is a necessary step in order for your presentation to run smoothly, there are many different styles and approaches you can use when creating one. Ultimately though, the goal is always to ensure that the information presented is factual and relevant to both you and your audience. By carefully designing and structuring an effective outline, both you and your audience will be sure to benefit greatly from it when it comes time for delivering a successful presentation .

Now that speakers know how to create an effective outline, it’s time to begin researching the content they plan to include in their speeches. In the next section we’ll discuss how to conduct research for an informative speech so speakers are armed with all the facts necessary to deliver an interesting and engaging presentation .

How to Research for an Informative Speech

When researching an informative speech, it’s important to find valid and reliable sources of information. There are many ways that one can seek out research for an informative speech, and no single method will guarantee a thorough reliable research. Depending on the complexity of the topic and the depth of knowledge required, a variety of methods should be utilized. The first step when researching for an informative speech should be to evaluate your present knowledge of the subject. This will help to determine what specific areas require additional research, and give clues as to where you might start looking for evidence. It is important to know the basic perspectives and arguments surrounding your chosen topic in order to select good sources and avoid biased materials. Textbooks, academic journals, newspaper articles, broadcasts, or credible websites are good starting points for informational speeches. As you search for information and evidence, be sure to use trustworthy authors who cite their sources. These sources refer to experts in the field whose opinions add credibility and can bolster your argument with facts and data. Evaluating these sources is particularly important as they form the foundation of your speech content and structure. Analyze each source critically by looking into who wrote it and evaluating how recent or relevant it is to the current conversation on your chosen topic. As with any research paper, one must strive for accuracy when gathering evidence while also surveying alternative positions on a topic. Considering both sides of a debate allows your speech to provide accurate information while remaining objective. This will also encourage audience members to draw their conclusions instead of taking your word for it. Furthermore, verifying sources from multiple angles (multiple avenues) ensures that information is fact-checked versus opinionated or biased pieces which might distort accuracy or mislead an audience member seeking truth about a controversial issue. At this stage in preparing for an informative speech, research should have been carried out thoroughly enough to allow confidently delivering evidence-based statements about a chosen topic. With all of this necessary groundwork completed, it’s time to move onto the next stage: sourcing different types of evidence which will allow you to illustrate your point in an even more helpful way. It is now time to transition into discussing “Sources & Evidence”.

Sources and Evidence

When crafting an informative speech outline, it is important to include accurate sources and valid evidence. Your audience needs to be sure that the content you are presenting not only reflects a clear understanding of the topic but is also backed up with reliable sources. For example, if you are speaking about climate change, include research studies, statistics, surveys and other forms of data that provide concrete evidence that supports your argument or position. Additionally, be sure to cite any sources used in the speech so that your audience can double-check the accuracy. In some cases, particularly when discussing sensitive topics, each side of the issue should be addressed. Not only does this make for a more balanced discussion, it also allows you to show respect for different points of view without compromising your own opinion or position. Presenting both sides briefly will demonstrate a comprehensive understanding of the subject matter and show your ability to present a well-rounded argument. Knowing how to source accurately and objectively is key to creating an informative speech outline which will be compelling and engaging for an audience. With the right sources and evidence utilized correctly, you can ensure that your argument is both authoritative and convincing. With these fundamentals in place, you can move on to developing tips for crafting an informative speech for maximum impact and engagement with the listeners.

Tips for Crafting an Informative Speech

When crafting an informative speech, there are certain tips and tricks that you can use to make sure your outline is the best it can be. Firstly, if you are speaking about a controversial issue, make sure you present both sides of the argument in an unbiased manner. Rely on researching credible sources, and discuss different points of views objectively. Additionally, organize and prioritize your points so that they are easy to follow and follow a logical progression. Begin with introducing a succinct thesis statement that briefly summarizes the main points of your speech. This will give the audience a clear idea of what topics you will be discussing and help retain their attention throughout your speech. Furthermore, be mindful to weave in personal anecdotes or relevant stories so that the audience can better relate to your ideas. Make sure the anecdotes have a purpose and demonstrate the key themes effectively. Acquiring creative ways to present data or statistics is also important; avoid inundating the audience with too many facts and figures all at once. Finally, ensure that all visual aids such as props, charts or slides remain relevant to the subject matter being discussed. Visual aids not only keep listeners engaged but also make difficult concepts easier to understand. With these handy tips in mind, you should be well on your way to constructing an effective informative speech outline! Now let’s move onto exploring some examples of effective informative speech outlines so that we can get a better idea of how it’s done.

Examples of Effective Informative Speech Outlines

Informative speeches must be compelling and provide relevant details, making them effective and impactful. In order to create an effective outline, speakers must first conduct extensive research on the chosen topic. An effective informative speech outline will clearly provide the audience with enough information to keep them engaged while also adhering to a specific timeframe. The following are examples of how to effectively organize an informative speech: I. Introduction: A. Stimulate their interest – pose a question, present intriguing facts or establish a humorous story B. Clearly state the main focus of the speech C. Establish your credibility– explain your experience/research conducted for the speech II. Supporting Points: A. Each point should contain facts and statistics related to your main idea B. Each point should have its own solid evidence that supports it III. Conclusion: A. Summarize supporting points B. Revisit your introduction point and explain how it’s been updated/changed through the course of the discussion C. Offer a final statement or call to action IV. Bibliography: A. Cite all sources used in creating the speech (provide an alphabetical list) Debate both sides of argument if applicable: N/A

Commonly Asked Questions

What techniques can i use to ensure my informative speech outline is organized and cohesive.

When crafting an informative speech outline, there are several techniques you can use to ensure your speech is organized and cohesive. First of all, make sure your speech follows a logical flow by using signposting , outlining the main ideas at the beginning of the speech and then bulleting out your supporting points. Additionally, you can use transitions throughout the speech to create a smooth order for your thoughts, such as ‘next’ and ‘finally’. Furthermore, it is important that each point in your outline has a specific purpose or goal, to avoid rambling and confusion. Finally, use visual aids such as charts and diagrams to emphasise key ideas and add clarity and structure to your speech. By following these techniques , you can ensure your informative speech outline is well organized and easy to follow.

How should I structure the order of the information in an informative speech outline?

The structure of an informative speech outline should be simple and organized, following a linear step-by-step process. First, you should introduce the topic to your audience and provide an overview of the main points. Next, give an explanation of each point, offer evidence or examples to support it, and explain how it relates to the overall subject matter. Finally, you should conclude with a summary of the main points and a call for action. When structuring the order of information in an informative speech outline, it is important to keep topics distinct from one another and stick to the logical progression that you have established in your introduction. Additionally, pay attention to chronology if appropriate; when discussing historical events, for example, make sure that they are presented in the correct order. Moreover, use transition phrases throughout your outline to help move ideas along smoothly. Finally, utilize both verbal and visual aids such as diagrams or graphics to illustrate complex knowledge effectively and engage your audience throughout your presentation.

What are the essential components of an informative speech outline?

The essential components of an informative speech outline are the introduction, body, and conclusion. Introduction: The introduction should establish the topic of your speech, provide background information, and lead into the main purpose of your speech. It’s also important to include a strong attention-grabbing hook in order to grab the audience’s attention. Body: The body is where you expand on the main points that were outlined in the introduction. It should provide evidence and arguments to support these points, as well as explain any counterarguments that might be relevant. Additionally, it should answer any questions or objections your audience may have about the topic. Conclusion: The conclusion should restate the purpose of your speech and summarize the main points from the body of your speech. It should also leave your audience feeling inspired and motivated to take some kind of action after hearing your speech. In short, an effective informative speech outline should strongly focus on bringing all of these elements together in a cohesive structure to ensure that you deliver an engaging presentation that educates and informs your audience.

Informative Speech

Informative Speech Outline

Informative Speech Outline - Format, Writing Steps, and Examples

People also read

Informative Speech Writing - A Complete Guide

Good Informative Speech Topics & Ideas

Collection of Ideas and ‘How To’ Demonstrative Speech Topics

10+ Informative Speech Examples - Get Inspiration For Any Type

Understanding Different Types of Informative Speeches with Examples

Are you tasked with delivering an informative speech but don’t know how to begin? You're in the right place!

This type of speech aims to inform and educate the audience about a particular topic. It conveys knowledge about that topic in a systematic and logical way, ensuring that the audience gets the intended points comprehensively.

So, how do you prepare for your speech? Here’s the answer: crafting an effective informative speech begins with a well-structured outline.

In this guide, we'll walk you through the process of creating an informative speech outline, step by step. Plus, you’ll get some amazing informative speech outline examples to inspire you.

Let’s get into it!

- 1. What is an Informative Speech Outline?

- 2. How to Write an Informative Speech Outline?

- 3. Informative Speech Outline Examples

What is an Informative Speech Outline?

An informative speech outline is like a roadmap for your presentation. It's a structured plan that helps you organize your thoughts and information in a clear and logical manner.

Here's what an informative speech outline does:

- Organizes Your Ideas: It helps you arrange your thoughts and ideas in a logical order, making it easier for your audience to follow your presentation.

- Ensures Clarity: An outline ensures that your speech is clear and easy to understand. It prevents you from jumping from one point to another without a clear path.

- Saves Time: With a well-structured outline, you'll spend less time searching for what to say next during your speech. It's your cheat sheet.

- Keeps Your Audience Engaged: A well-organized outline keeps your audience engaged and focused on your message. It's the key to a successful presentation.

- Aids Memorization: Having a structured outline can help you remember key points and maintain a confident delivery.

How to Write an Informative Speech Outline?

Writing a helpful speech outline is not so difficult if you know what to do. Here are 4 simple steps to craft a perfect informative outline.

Step 1: Choose an Engaging Topic

Selecting the right topic is the foundation of a compelling, informative speech. Choose unique and novel informative speech topics that can turn into an engaging speech.

Here's how to do it:

- Consider Your Audience: Think about the interests, knowledge, and expectations of your audience. What would they find interesting and relevant?

- Choose Your Expertise: Opt for a topic you're passionate about or knowledgeable in. Your enthusiasm will shine through in your presentation.

- Narrow It Down: Avoid broad subjects. Instead, focus on a specific aspect of the topic to keep your speech manageable and engaging.

With these tips in mind, you can find a great topic for your speech.

Step 2: Conduct Some Research

Now that you have your topic, it's time to gather the necessary information. You need to do thorough research and collect some credible information necessary for the audience to understand your topic.

Moreover, understand the types of informative speeches and always keep the main purpose of your speech in mind. That is, to inform, educate, or teach. This will help you to avoid irrelevant information and stay focused on your goal.

Step 3: Structure Your Information

Now that you have the required information to make a good speech, you need to organize it logically. This is where the outlining comes in!

The basic speech format consists of these essential elements:

Moreover, there are two different ways to write your outline:

- The complete sentence format

- The key points format

In the complete sentence outline , you write full sentences to indicate each point and help you check the organization and content of the speech.

In the key points format, you just note down the key points and phrases that help you remember what you should include in your speech.

Step 4: Review and Revise

Finally, once you've created your initial informative speech outline, you need to review and revise it.

Here's how to go about it:

- Ensure Clarity: Review your outline to ensure that your main points and supporting details are clear and easy to understand.

- Verify Logical Sequence: Double-check the order of your points and transitions. Ensure that the flow of your speech is logical and that your audience can follow it easily.

- Eliminate Redundancy: Remove any redundant or repetitive information. Keep your outline concise and to the point.

- Time Yourself: Estimate how long it will take to deliver your speech. Ensure it fits within the allotted time frame, whether it's a few minutes or an hour.

- Get Feedback: Share your outline with a friend, family member, or colleague and ask for their input. Fresh eyes can provide valuable suggestions for improvement.

Follow these basic steps and write a compelling speech that gives complete knowledge about the topic. Here is a sample outline example that will help you better understand how to craft an informative speech outline.

Informative Speech Outline Format

Informative Speech Outline Examples

Let’s explore a few example outlines to help you visualize an informative speech outline. These examples illustrate the outlines for different topics and subjects.

Mental Health Informative Speech Outline

Stress Informative Speech Outline

Social Media Informative Speech Outline

Informative Speech Outline Template

Informative Speech Outline Sample

To sum it up,

Creating an effective outline is your pathway to delivering an impactful, organized, and engaging speech. Making an outline for your speech ensures that your message shines through with clarity and purpose.

With the help of the steps and examples given above, you will be able to create a well-structured outline for your informative speech. So go ahead and deliver an engaging informative speech with the help of outlines.

Moreover, if you're passionate about public speaking but find speech writing a tedious task, your worries can now take a back seat. At MyPerfectWords.com , we offer a convenient solution.

Our essay writing service is dedicated to providing you with top-notch content, ensuring you get the results you desire.

So, why wait? Buy Speech today and elevate your public speaking game.

Write Essay Within 60 Seconds!

Cathy has been been working as an author on our platform for over five years now. She has a Masters degree in mass communication and is well-versed in the art of writing. Cathy is a professional who takes her work seriously and is widely appreciated by clients for her excellent writing skills.

Paper Due? Why Suffer? That’s our Job!

Keep reading

Informative Speech

Informative Speech Outline

Last updated on: Apr 26, 2024

Learn How to Create an Informative Speech Outline

By: Cathy A.

Reviewed By: Rylee W.

Published on: May 26, 2020

-11770.jpg )

Presenting a detailed informative speech can be really nerve-wracking, especially if you're not sure where to start.

An informative speech is a powerful way of sharing knowledge with your audience. It needs to be well-formatted and properly structured. This type of speech allows you to inform the audience about a topic in depth.

Most people try to wing it, and that's why they bomb. They get up in front of an audience and have no idea what to say next. This is why an outline is necessary for enough preparation.

So how do you write an effective outline to make your speech successful?

Here you will learn how to outline your speech in the most effective and easiest steps. Moreover, you’ll also get some outline examples and tips to help you put the steps into practice.

So let’s get into it!

-11770.jpg)

On this Page

Why Create an Outline for Informative Speech?

An informative speech outline is a great way to organize your ideas and thoughts before you start writing. It allows you to see the flow of your speech and that all main points are cohesive with each other.

Moreover, a clear and concise outline helps you develop your thoughts on a topic. It also creates a structure to help you keep track of all the points you want to make.

So, to be an effective speaker, you need to create a clear outline for an informative speech. Read on to learn how you can do that.

How to Write an Informative Speech Outline?

Making an outline for your speech is not as difficult as you may think. You just need to follow some basic steps, and your outline will be good to go.

Below are the steps that will help you create a well-written outline:

Step 1 – Choose a Topic that Interests You

Speech topics are usually assigned, but if you have to pick on your own, create a list of topics that interest you. Select one topic about which there is still so much to learn and explore.

Since it is a descriptive speech, the topic should give you the space to provide information to the audience.

Need inspiration for a topic? Find 100+ unique and interesting informative speech topics to engage your audience.

Step 2 – Gather Information

After choosing the topic, start the research phase and gather relevant information. The information should be so that it helps to satisfy your specific purpose of delivering the speech.

Also, make sure that you collect information from credible and trustworthy sources. You can collect data for your speech from:

- Scholarly articles

- Encyclopedias

- Government documents

The more you research, the more easily you write a good informative speech.

Step 3 – Write Points for an Introduction

Now that you have all the information, start writing the outline. Begin with writing points for your introduction. The introduction is the first part of your speech that introduces the topic to your audience and previews the main points you are going to discuss.

Here’s how to proceed:

- Start with a hook or attention-grabber to engage your audience. You can use a quote, a statistic or fact, or a thought-provoking question to begin your speech and grab your listener’s attention.

- Next, make an outline of points that’ll help you provide context or essential background information about the topic.

- Finally, clearly mention the main topic of your speech and preview the points you are going to discuss next.

Step 4 – Organize Your Main Body

Once the outline for your intro is complete, move on to the main body. The body of an informative speech provides explanation, information, description, and examples about the topic to cover it in detail.

- Write the first point you would like to discuss. Under the first point, add any information, examples, or explanation you want to present.

- Similarly, write down your second main point and write all the information you gathered related to it that you would like to offer.

- Move onto the next point. Cover all the points one-by-one until all the information you want to provide is coherently organized and categorized.

Step 5 – Add a Conclusion

The conclusion of an informative speech aims to summarize the information in such a way that it becomes easier to remember. That is, you should provide short key takeaways and a memorable ending as the conclusion of your speech.

Follow these steps:

- Begin your conclusion with a brief summary of the main points discussed throughout your speech. This helps the audience recall important details.

- Highlight why understanding this information is valuable or how it can benefit them in some way. This reinforces the importance of what you've shared.

- Finally, add a call-to-action, such as encouraging your audience to apply the knowledge they've gained or to further explore the topic.

Step 6 – Improve & Revise as Needed

As you finish adding points for the conclusion, the main outline writing steps are done. Now, you simply need to look it up once again, find areas of improvement, and revise. Here are some key steps to improve and refine your speech:

- Review your speech for clarity and coherence. Your ideas should progress logically from one point to the next, and that transitions between sections should be smooth.

- Assess whether your speech effectively captures and maintains the audience's interest throughout. Look for opportunities to incorporate engaging anecdotes, relevant examples, or multimedia elements such as images or videos for better understanding.

- Go through each section of your speech to ensure the information is accurate and relevant. Verify any facts, statistics, or examples you've included, and make sure they support your main points effectively.

Informative Speech Outline Template

There are two ways to write the outline of your speech:

- Complete Sentence Format: In this format, you can write full sentences in the outline, so that help you check the content of the speech.

- Key Point Format: Or, you can simply note down the keywords or points that help you remember what you should include in your speech.

So, you have the chance to choose whichever outline format suits your needs best.

Whether you choose to write complete sentences or keywords and points, use this template below to craft your informative speech outline.

Informative Speech Outline Examples

Done with understanding what an informative speech outline is? Now let’s move to see some samples of informative speech outline. With the help of these professionally written examples, you can get the inspiration to create a good one yourself.

Check the below informative speech outline samples and get an idea of the perfect outline.

Simple Informative Speech Outline Example

Informative Speech Outline about Social Media

Informative Speech Outline about Depression

Informative Speech Outline about Covid 19

Global Warming Informative Speech Outline

Mental Health Informative Speech Outline

Anxiety Informative Speech Outline

Sleep Informative Speech Outline

Informative Speech Outline About Education

Informative Speech Outline Format 3-5 Minutes

Taking Depression Seriously Informative Speech Outline

Sample Informative Speech Outline

Mental Illness Informative Speech Outline

Tips for a More Effective Informative Speech Outline

Following are the tips you should follow to impress the audience with your speech.

- Tailor your outline according to your audience. Consider their interests, knowledge level, and preferences when developing your outline. Adapt your content to effectively address your specific audience and keep them engaged throughout your speech.

- Include visual aids such as infographics or diagrams while making your outline. This material will help you convey your points more clearly to the audience.

- Use a consistent structure for your topic. For instance, you can use the problem-solution, cause-effect, or compare-contrast format, depending on the nature of your topic. However, keep it consistent throughout.

- Seek feedback by sharing your outline with peers, mentors, or instructors. Use their insights to make any necessary revisions.

Mistakes To Avoid

Here are mistakes to avoid while creating an informative speech outline:

- Do not overload your outline with excessive information, as it can overwhelm your audience.

- Steer clear of a disorganized structure that confuses your audience.

- Do not provide shallow information; instead, ensure depth and substance in your main points.

- Avoid neglecting transitions, as it can disrupt the flow of your speech.

- Do not overlook the importance of engaging your audience through visuals, storytelling, and rhetoric.

- Avoid inadequate time management, as it can lead to rushing or exceeding the allocated time.

Wrapping Up!

Now, you have a complete guide to writing an informative speech outline.

Moreover, if you need professional help in creating a speech that is an attention-getter, consult MyPerfectPaper.net .

Our team of professional writers will help you create an engaging, interesting, and creative speech. All you have to say is ‘ write my paper for me ’, and our expert writers will take your speech writing stress away!

So, contact us now and get an expertly crafted speech at affordable rates.

Are you feeling overwhelmed with assignments? Our AI paper writer can help you manage your workload. Try it out and stay on top of your studies!

Marketing, Literature

Cathy has been been working as an author on our platform for over five years now. She has a Masters degree in mass communication and is well-versed in the art of writing. Cathy is a professional who takes her work seriously and is widely appreciated by clients for her excellent writing skills.

Was This Blog Helpful?

Keep reading.

- Everything you Need to Know About Informative Speech – Types, Writing Steps, & Example

- 100+ Informative Speech Topics for 2024

-11769.jpg)

- List of Interesting Demonstration Speech Ideas & Topics

-11771.jpg)

People Also Read

- autobiography vs biography

- compare and contrast essay writing

- types of essay

- how to write an essay

- classification essay topics

Burdened With Assignments?

Advertisement

- LEGAL Privacy Policy

© 2024 - All rights reserved

Planning and Presenting an Informative Speech

In this guide, you can learn about the purposes and types of informative speeches, about writing and delivering informative speeches, and about the parts of informative speeches.

Purposes of Informative Speaking

Informative speaking offers you an opportunity to practice your researching, writing, organizing, and speaking skills. You will learn how to discover and present information clearly. If you take the time to thoroughly research and understand your topic, to create a clearly organized speech, and to practice an enthusiastic, dynamic style of delivery, you can be an effective "teacher" during your informative speech. Finally, you will get a chance to practice a type of speaking you will undoubtedly use later in your professional career.

The purpose of the informative speech is to provide interesting, useful, and unique information to your audience. By dedicating yourself to the goals of providing information and appealing to your audience, you can take a positive step toward succeeding in your efforts as an informative speaker.

Major Types of Informative Speeches

In this guide, we focus on informative speeches about:

These categories provide an effective method of organizing and evaluating informative speeches. Although they are not absolute, these categories provide a useful starting point for work on your speech.

In general, you will use four major types of informative speeches. While you can classify informative speeches many ways, the speech you deliver will fit into one of four major categories.

Speeches about Objects

Speeches about objects focus on things existing in the world. Objects include, among other things, people, places, animals, or products.

Because you are speaking under time constraints, you cannot discuss any topic in its entirety. Instead, limit your speech to a focused discussion of some aspect of your topic.

Some example topics for speeches about objects include: the Central Intelligence Agency, tombstones, surgical lasers, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, the pituitary gland, and lemmings.

To focus these topics, you could give a speech about Franklin Delano Roosevelt and efforts to conceal how he suffered from polio while he was in office. Or, a speech about tombstones could focus on the creation and original designs of grave markers.

Speeches about Processes

Speeches about processes focus on patterns of action. One type of speech about processes, the demonstration speech, teaches people "how-to" perform a process. More frequently, however, you will use process speeches to explain a process in broader terms. This way, the audience is more likely to understand the importance or the context of the process.

A speech about how milk is pasteurized would not teach the audience how to milk cows. Rather, this speech could help audience members understand the process by making explicit connections between patterns of action (the pasteurization process) and outcomes (a safe milk supply).

Other examples of speeches about processes include: how the Internet works (not "how to work the Internet"), how to construct a good informative speech, and how to research the job market. As with any speech, be sure to limit your discussion to information you can explain clearly and completely within time constraints.

Speeches about Events

Speeches about events focus on things that happened, are happening, or will happen. When speaking about an event, remember to relate the topic to your audience. A speech chronicling history is informative, but you should adapt the information to your audience and provide them with some way to use the information. As always, limit your focus to those aspects of an event that can be adequately discussed within the time limitations of your assignment.

Examples of speeches about events include: the 1963 Civil Rights March on Washington, Groundhog's Day, the Battle of the Bulge, the World Series, and the 2000 Presidential Elections.

Speeches about Concepts

Speeches about concepts focus on beliefs, ideas, and theories. While speeches about objects, processes, and events are fairly concrete, speeches about concepts are more abstract. Take care to be clear and understandable when creating and presenting a speech about a concept. When selecting a concept, remember you are crafting an informative speech. Often, speeches about concepts take on a persuasive tone. Focus your efforts toward providing unbiased information and refrain from making arguments. Because concepts can be vague and involved, limit your speech to aspects that can be readily explained and understood within the time limits.

Some examples of topics for concept speeches include: democracy, Taoism, principles of feminism, the philosophy of non-violent protest, and the Big Bang theory.

Strategies for Selecting a Topic

In many cases, circumstances will dictate the topic of your speech. However, if the topic has not been assigned or if you are having difficulty figuring out how to frame your topic as an informative speech,the following may be useful.

Begin by thinking of your interests. If you have always loved art, contemplate possible topics dealing with famous artists, art works, or different types of art. If you are employed, think of aspects of your job or aspects of your employer's business that would be interesting to talk about. While you cannot substitute personal experience for detailed research, your own experience can supplement your research and add vitality to your presentation. Choose one of the items below to learn more about selecting a topic.

Learn More about an Unfamiliar Topic

You may benefit more by selecting an unfamiliar topic that interests you. You can challenge yourself by choosing a topic you'd like to learn about and to help others understand it. If the Buddhist religion has always been an interesting and mysterious topic to you, research the topic and create a speech that offers an understandable introduction to the religion. Remember to adapt Buddhism to your audience and tell them why you think this information is useful to them. By taking this approach, you can learn something new and learn how to synthesize new information for your audience.

Think about Previous Classes

You might find a topic by thinking of classes you have taken. Think back to concepts covered in those classes and consider whether they would serve as unique, interesting, and enlightening topics for the informative speech. In astronomy, you learned about red giants. In history, you learned about Napoleon. In political science, you learned about The Federalist Papers. Past classes serve as rich resources for informative speech topics. If you make this choice, use your class notes and textbook as a starting point. To fully develop the content, you will need to do extensive research and perhaps even a few interviews.

Talk to Others

Topic selection does not have to be an individual effort. Spend time talking about potential topics with classmates or friends. This method can be extremely effective because other people can stimulate further ideas when you get stuck. When you use this method, always keep the basic requirements and the audience in mind. Just because you and your friend think home-brew is a great topic does not mean it will enthrall your audience or impress your instructor. While you talk with your classmates or friends, jot notes about potential topics and create a master list when you exhaust the possibilities. From this list, choose a topic with intellectual merit, originality, and potential to entertain while informing.

Framing a Thesis Statement

Once you settle on a topic, you need to frame a thesis statement. Framing a thesis statement allows you to narrow your topic, and in turns allows you to focus your research in this specific area, saving you time and trouble in the process.

Selecting a topic and focusing it into a thesis statement can be a difficult process. Fortunately, a number of useful strategies are available to you.

Thesis Statement Purpose

The thesis statement is crucial for clearly communicating your topic and purpose to the audience. Be sure to make the statement clear, concise, and easy to remember. Deliver it to the audience and use verbal and nonverbal illustrations to make it stand out.

Strategies For Framing a Thesis Statement

Focus on a specific aspect of your topic and phrase the thesis statement in one clear, concise, complete sentence, focusing on the audience. This sentence sets a goal for the speech. For example, in a speech about art, the thesis statement might be: "The purpose of this speech is to inform my audience about the early works of Vincent van Gogh." This statement establishes that the speech will inform the audience about the early works of one great artist. The thesis statement is worded conversationally and included in the delivery of the speech.

Thesis Statement and Audience

The thesis appears in the introduction of the speech so that the audience immediately realizes the speaker's topic and goal. Whatever the topic may be, you should attempt to create a clear, focused thesis statement that stands out and could be repeated by every member of your audience. It is important to refer to the audience in the thesis statement; when you look back at the thesis for direction, or when the audience hears the thesis, it should be clear that the most important goal of your speech is to inform the audience about your topic. While the focus and pressure will be on you as a speaker, you should always remember that the audience is the reason for presenting a public speech.

Avoid being too trivial or basic for the average audience member. At the same time, avoid being too technical for the average audience member. Be sure to use specific, concrete terms that clearly establish the focus of your speech.

Thesis Statement and Delivery

When creating the thesis statement, be sure to use a full sentence and frame that sentence as a statement, not as a question. The full sentence, "The purpose of this speech is to inform my audience about the early works of Vincent van Gogh," provides clear direction for the speech, whereas the fragment "van Gogh" says very little about the purpose of the speech. Similarly, the question "Who was Vincent van Gogh?" does not adequately indicate the direction the speech will take or what the speaker hopes to accomplish.

If you limit your thesis statement to one distinct aspect of the larger topic, you are more likely to be understood and to meet the time constraints.

Researching Your Topic

As you begin to work on your informative speech, you will find that you need to gather additional information. Your instructor will most likely require that you locate relevant materials in the library and cite those materials in your speech. In this section, we discuss the process of researching your topic and thesis.

Conducting research for a major informative speech can be a daunting task. In this section, we discuss a number of strategies and techniques that you can use to gather and organize source materials for your speech.

Gathering Materials

Gathering materials can be a daunting task. You may want to do some research before you choose a topic. Once you have a topic, you have many options for finding information. You can conduct interviews, write or call for information from a clearinghouse or public relations office, and consult books, magazines, journals, newspapers, television and radio programs, and government documents. The library will probably be your primary source of information. You can use many of the libraries databases or talk to a reference librarian to learn how to conduct efficient research.

Taking Notes

While doing your research, you may want to carry notecards. When you come across a useful passage, copy the source and the information onto the notecard or copy and paste the information. You should maintain a working bibliography as you research so you always know which sources you have consulted and so the process of writing citations into the speech and creating the bibliography will be easier. You'll need to determine what information-recording strategies work best for you. Talk to other students, instructors, and librarians to get tips on conducting efficient research. Spend time refining your system and you will soon be able to focus on the information instead of the record-keeping tasks.

Citing Sources Within Your Speech

Consult with your instructor to determine how much research/source information should be included in your speech. Realize that a source citation within your speech is defined as a reference to or quotation from material you have gathered during your research and an acknowledgement of the source. For example, within your speech you might say: "As John W. Bobbitt said in the December 22, 1993, edition of the Denver Post , 'Ouch!'" In this case, you have included a direct quotation and provided the source of the quotation. If you do not quote someone, you might say: "After the first week of the 1995 baseball season, attendance was down 13.5% from 1994. This statistic appeared in the May 7, 1995, edition of the Denver Post ." Whatever the case, whenever you use someone else's ideas, thoughts, or words, you must provide a source citation to give proper credit to the creator of the information. Failure to cite sources can be interpreted as plagiarism which is a serious offense. Upon review of the specific case, plagiarism can result in failure of the assignment, the course, or even dismissal from the University. Take care to cite your sources and give credit where it is due.

Creating Your Bibliography

As with all aspects of your speech, be sure to check with your instructor to get specific details about the assignment.

Generally, the bibliography includes only those sources you cited during the speech. Don't pad the bibliography with every source you read, saw on the shelf, or heard of from friends. When you create the bibliography, you should simply go through your complete sentence outline and list each source you cite. This is also a good way to check if you have included enough reference material within the speech. You will need to alphabetize the bibiography by authors last name and include the following information: author's name, article title, publication title, volume, date, page number(s). You may need to include additional information; you need to talk with your instructor to confirm the required bibliographical format.

Some Cautions

When doing research, use caution in choosing your sources. You need to determine which sources are more credible than others and attempt to use a wide variety of materials. The broader the scope of your research, the more impressive and believable your information. You should draw from different sources (e.g., a variety of magazines-- Time, Newsweek, US News & World Report, National Review, Mother Jones ) as well as different types of sources (i.e., use interviews, newspapers, periodicals, and books instead of just newspapers). The greater your variety, the more apparent your hard work and effort will be. Solid research skills result in increased credibility and effectiveness for the speaker.

Structuring an Informative Speech

Typically, informative speeches have three parts:

Introduction

In this section, we discuss the three parts of an informative speech, calling attention to specific elements that can enhance the effectiveness of your speech. As a speaker, you will want to create a clear structure for your speech. In this section, you will find discussions of the major parts of the informative speech.

The introduction sets the tone of the entire speech. The introduction should be brief and to-the-point as it accomplishes these several important tasks. Typically, there are six main components of an effective introduction:

Attention Getters

Thesis statement, audience adaptation, credibility statement, transition to the body.

As in any social situation, your audience makes strong assumptions about you during the first eight or ten seconds of your speech. For this reason, you need to start solidly and launch the topic clearly. Focus your efforts on completing these tasks and moving on to the real information (the body) of the speech. Typically, there are six main components of an effective introduction. These tasks do not have to be handled in this order, but this layout often yields the best results.

The attention-getter is designed to intrigue the audience members and to motivate them to listen attentively for the next several minutes. There are infinite possibilities for attention-getting devices. Some of the more common devices include using a story, a rhetorical question, or a quotation. While any of these devices can be effective, it is important for you to spend time strategizing, creating, and practicing the attention-getter.

Most importantly, an attention-getter should create curiosity in the minds of your listeners and convince them that the speech will be interesting and useful. The wording of your attention-getter should be refined and practiced. Be sure to consider the mood/tone of your speech; determine the appropriateness of humor, emotion, aggressiveness, etc. Not only should the words get the audiences attention, but your delivery should be smooth and confident to let the audience know that you are a skilled speaker who is prepared for this speech.

The crowd was wild. The music was booming. The sun was shining. The cash registers were ringing.

This story-like re-creation of the scene at a Farm Aid concert serves to engage the audience and causes them to think about the situation you are describing. Touching stories or stories that make audience members feel involved with the topic serve as good attention-getters. You should tell a story with feeling and deliver it directly to the audience instead of reading it off your notecards.

Example Text : One dark summer night in 1849, a young woman in her 20's left Bucktown, Maryland, and followed the North Star. What was her name? Harriet Tubman. She went back some 19 times to rescue her fellow slaves. And as James Blockson relates in a 1984 issue of National Geographic , by the end of her career, she had a $40,000.00 price on her head. This was quite a compliment from her enemies (Blockson 22).

Rhetorical Question

Rhetorical questions are questions designed to arouse curiosity without requiring an answer. Either the answer will be obvious, or if it isn't apparent, the question will arouse curiosity until the presentation provides the answer.

An example of a rhetorical question to gain the audiences attention for a speech about fly-fishing is, "Have you ever stood in a freezing river at 5 o'clock in the morning by choice?"

Example Text: Have you ever heard of a railroad with no tracks, with secret stations, and whose conductors were considered criminals?

A quotation from a famous person or from an expert on your topic can gain the attention of the audience. The use of a quotation immediately launches you into the speech and focuses the audience on your topic area. If it is from a well-known source, cite the author first. If the source is obscure, begin with the quote itself.

Example Text : "No day dawns for the slave, nor is it looked for. It is all night--night forever . . . ." (Pause) This quote was taken from Jermain Loguen, a fugitive who was the son of his Tennessee master and a slave woman.

Unusual Statement

Making a statement that is unusual to the ears of your listeners is another possibility for gaining their attention.

Example Text : "Follow the drinking gourd. That's what I said, friend, follow the drinking gourd." This phrase was used by slaves as a coded message to mean the Big Dipper, which revealed the North Star, and pointed toward freedom.

You might chose to use tasteful humor which relates to the topic as an effective way to attract the audience both to you and the subject at hand.

Example Text : "I'm feeling boxed in." [PAUSE] I'm not sure, but these may have been Henry "Box" Brown's very words after being placed on his head inside a box which measured 3 feet by 2 feet by 2 1\2 feet for what seemed to him like "an hour and a half." He was shipped by Adams Express to freedom in Philadelphia (Brown 60,92; Still 10).

Shocking Statistic

Another possibility to consider is the use of a factual statistic intended to grab your listener's attention. As you research the topic you've picked, keep your eyes open for statistics that will have impact.

Example Text : Today, John Elway's talents are worth millions, but in 1840 the price of a human life, a slave, was worth $1,000.00.

Example Text : Today I'd like to tell you about the Underground Railroad.

In your introduction, you need to adapt your speech to your audience. To keep audience members interested, tell them why your topic is important to them. To accomplish this task, you need to undertake audience analysis prior to creating the speech. Figure out who your audience members are, what things are important to them, what their biases may be, and what types of subjects/issues appeal to them. In the context of this class, some of your audience analysis is provided for you--most of your listeners are college students, so it is likely that they place some value on education, most of them are probably not bathing in money, and they live in Colorado. Consider these traits when you determine how to adapt to your audience.

As you research and write your speech, take note of references to issues that should be important to your audience. Include statements about aspects of your speech that you think will be of special interest to the audience in the introduction. By accomplishing this task, you give your listeners specific things with which they can identify. Audience adaptation will be included throughout the speech, but an effective introduction requires meaningful adaptation of the topic to the audience.

You need to find ways to get the members of your audience involved early in the speech. The following are some possible options to connect your speech to your audience:

Reference to the Occasion

Consider how the occasion itself might present an opportunity to heighten audience receptivity. Remind your listeners of an important date just passed or coming soon.

Example Text : This January will mark the 130th anniversary of a "giant interracial rally" organized by William Still which helped to end streetcar segregation in the city of Philadelphia (Katz i).

Reference to the Previous Speaker

Another possibility is to refer to a previous speaker to capitalize on the good will which already has been established or to build on the information presented.

Example Text : As Alice pointed out last week in her speech on the Olympic games of the ancient world, history can provide us with fascinating lessons.

The credibility statement establishes your qualifications as a speaker. You should come up with reasons why you are someone to listen to on this topic. Why do you have special knowledge or understanding of this topic? What can the audience learn from you that they couldn't learn from someone else? Credibility statements can refer to your extensive research on a topic, your life-long interest in an issue, your personal experience with a thing, or your desire to better the lives of your listeners by sifting through the topic and providing the crucial information.

Remember that Aristotle said that credibility, or ethos, consists of good sense, goodwill, and good moral character. Create the feeling that you possess these qualities by creatively stating that you are well-educated about the topic (good sense), that you want to help each member of the audience (goodwill), and that you are a decent person who can be trusted (good moral character). Once you establish your credibility, the audience is more likely to listen to you as something of an expert and to consider what you say to be the truth. It is often effective to include further references to your credibility throughout the speech by subtly referring to the traits mentioned above.

Show your listeners that you are qualified to speak by making a specific reference to a helpful resource. This is one way to demonstrate competence.

Example Text : In doing research for this topic, I came across an account written by one of these heroes that has deepened my understanding of the institution of slavery. Frederick Douglass', My Bondage and My Freedom, is the account of a man whose master's kindness made his slavery only more unbearable.

Your listeners want to believe that you have their best interests in mind. In the case of an informative speech, it is enough to assure them that this will be an interesting speech and that you, yourself, are enthusiastic about the topic.

Example Text : I hope you'll enjoy hearing about the heroism of the Underground Railroad as much as I have enjoyed preparing for this speech.

Preview the Main Points

The preview informs the audience about the speech's main points. You should preview every main body point and identify each as a separate piece of the body. The purpose of this preview is to let the audience members prepare themselves for the flow of the speech; therefore, you should word the preview clearly and concisely. Attempt to use parallel structure for each part of the preview and avoid delving into the main point; simply tell the audience what the main point will be about in general.

Use the preview to briefly establish your structure and then move on. Let the audience get a taste of how you will divide the topic and fulfill the thesis and then move on. This important tool will reinforce the information in the minds of your listeners. Here are two examples of a preview:

Simply identify the main points of the speech. Cover them in the same order that they will appear in the body of the presentation.

For example, the preview for a speech about kites organized topically might take this form: "First, I will inform you about the invention of the kite. Then, I will explain the evolution of the kite. Third, I will introduce you to the different types of kites. Finally, I will inform you about various uses for kites." Notice that this preview avoids digressions (e.g., listing the various uses for kites); you will take care of the deeper information within the body of the speech.

Example Text : I'll tell you about motivations and means of escape employed by fugitive slaves.

Chronological

For example, the preview for a speech about the Pony Express organized chronologically might take this form: "I'll talk about the Pony Express in three parts. First, its origins, second, its heyday, and third, how it came to an end." Notice that this preview avoids digressions (e.g., listing the reasons why the Pony Express came to an end); you will cover the deeper information within the body of the speech.

Example Text : I'll talk about it in three parts. First, its origins, second, its heyday, and third, how it came to an end.

After you accomplish the first five components of the introduction, you should make a clean transition to the body of the speech. Use this transition to signal a change and prepare the audience to begin processing specific topical information. You should round out the introduction, reinforce the excitement and interest that you created in the audience during the introduction, and slide into the first main body point.

Strategic organization helps increase the clarity and effectiveness of your speech. Four key issues are discussed in this section:

Organizational Patterns

Connective devices, references to outside research.

The body contains the bulk of information in your speech and needs to be clearly organized. Without clear organization, the audience will probably forget your information, main points, perhaps even your thesis. Some simple strategies will help you create a clear, memorable speech. Below are the four key issues used in organizing a speech.

Once you settle on a topic, you should decide which aspects of that topic are of greatest importance for your speech. These aspects become your main points. While there is no rule about how many main points should appear in the body of the speech, most students go with three main points. You must have at least two main points; aside from that rule, you should select your main points based on the importance of the information and the time limitations. Be sure to include whatever information is necessary for the audience to understand your topic. Also, be sure to synthesize the information so it fits into the assigned time frame. As you choose your main points, try to give each point equal attention within the speech. If you pick three main points, each point should take up roughly one-third of the body section of your speech.

There are four basic patterns of organization for an informative speech.

- Chronological order

- Spatial order

- Causal order

- Topical order

There are four basic patterns of organization for an informative speech. You can choose any of these patterns based on which pattern serves the needs of your speech.

Chronological Order

A speech organized chronologically has main points oriented toward time. For example, a speech about the Farm Aid benefit concert could have main points organized chronologically. The first main point focuses on the creation of the event; the second main point focuses on the planning stages; the third point focuses on the actual performance/concert; and the fourth point focuses on donations and assistance that resulted from the entire process. In this format, you discuss main points in an order that could be followed on a calendar or a clock.

Spatial Order

A speech organized spatially has main points oriented toward space or a directional pattern. The Farm Aid speech's body could be organized in spatial order. The first main point discusses the New York branch of the organization; the second main point discusses the Midwest branch; the third main point discusses the California branch of Farm Aid. In this format, you discuss main points in an order that could be traced on a map.

Causal Order

A speech organized causally has main points oriented toward cause and effect. The main points of a Farm Aid speech organized causally could look like this: the first main point informs about problems on farms and the need for monetary assistance; the second main point discusses the creation and implementation of the Farm Aid program. In this format, you discuss main points in an order that alerts the audience to a problem or circumstance and then tells the audience what action resulted from the original circumstance.

Topical Order

A speech organized topically has main points organized more randomly by sub-topics. The Farm Aid speech could be organized topically: the first main point discusses Farm Aid administrators; the second main point discusses performers; the third main point discusses sponsors; the fourth main point discusses audiences. In this format, you discuss main points in a more random order that labels specific aspects of the topic and addresses them in separate categories. Most speeches that are not organized chronologically, spatially, or causally are organized topically.

Within the body of your speech, you need clear internal structure. Connectives are devices used to create a clear flow between ideas and points within the body of your speech--they serve to tie the speech together. There are four main types of connective devices:

Transitions

Internal previews, internal summaries.

Within the body of your speech, you need clear internal structure. Think of connectives as hooks and ladders for the audience to use when moving from point-to-point within the body of your speech. These devices help re-focus the minds of audience members and remind them of which main point your information is supporting. The four main types of connective devices are:

Transitions are brief statements that tell the audience to shift gears between ideas. Transitions serve as the glue that holds the speech together and allow the audience to predict where the next portion of the speech will go. For example, once you have previewed your main points and you want to move from the introduction to the body of the Farm Aid speech, you might say: "To gain an adequate understanding of the intricacies of this philanthropic group, we need to look at some specific information about Farm Aid. We'll begin by looking at the administrative branch of this massive fund-raising organization."

Internal previews are used to preview the parts of a main point. Internal previews are more focused than, but serve the same purpose as, the preview you will use in the introduction of the speech. For example, you might create an internal preview for the complex main point dealing with Farm Aid performers: "In examining the Farm Aid performers, we must acknowledge the presence of entertainers from different genres of music--country and western, rhythm and blues, rock, and pop." The internal preview provides specific information for the audience if a main point is complex or potentially confusing.

Internal summaries are the reverse of internal previews. Internal summaries restate specific parts of a main point. To internally summarize the main point dealing with Farm Aid performers, you might say: "You now know what types of people perform at the Farm Aid benefit concerts. The entertainers come from a wide range of musical genres--country and western, rhythm and blues, rock, and pop." When using both internal previews and internal summaries, be sure to stylize the language in each so you do not become redundant.

Signposts are brief statements that remind the audience where you are within the speech. If you have a long point, you may want to remind the audience of what main point you are on: "Continuing my discussion of Farm Aid performers . . . "

When organizing the body of your speech, you will integrate several references to your research. The purpose of the informative speech is to allow you and the audience to learn something new about a topic. Additionally, source citations add credibility to your ideas. If you know a lot about rock climbing and you cite several sources who confirm your knowledge, the audience is likely to see you as a credible speaker who provides ample support for ideas.

Without these references, your speech is more like a story or a chance for you to say a few things you know. To complete this assignment satisfactorily, you must use source citations. Consult your textbook and instructor for specific information on how much supporting material you should use and about the appropriate style for source citations.

While the conclusion should be brief and tight, it has a few specific tasks to accomplish:

Re-assert/Reinforce the Thesis

Review the main points, close effectively.

Take a deep breath! If you made it to the conclusion, you are on the brink of finishing. Below are the tasks you should complete in your conclusion:

When making the transition to the conclusion, attempt to make clear distinctions (verbally and nonverbally) that you are now wrapping up the information and providing final comments about the topic. Refer back to the thesis from the introduction with wording that calls the original thesis into memory. Assert that you have accomplished the goals of your thesis statement and create the feeling that audience members who actively considered your information are now equipped with an understanding of your topic. Reinforce whatever mood/tone you chose for the speech and attempt to create a big picture of the speech.

Within the conclusion, re-state the main points of the speech. Since you have used parallel wording for your main points in the introduction and body, don't break that consistency in the conclusion. Frame the review so the audience will be reminded of the preview and the developed discussion of each main point. After the review, you may want to create a statement about why those main points fulfilled the goals of the speech.

Finish strongly. When you close your speech, craft statements that reinforce the message and leave the audience with a clear feeling about what was accomplished with your speech. You might finalize the adaptation by discussing the benefits of listening to the speech and explaining what you think audience members can do with the information.

Remember to maintain an informative tone for this speech. You should not persuade about beliefs or positions; rather, you should persuade the audience that the speech was worthwhile and useful. For greatest effect, create a closing line or paragraph that is artistic and effective. Much like the attention-getter, the closing line needs to be refined and practiced. Your close should stick with the audience and leave them interested in your topic. Take time to work on writing the close well and attempt to memorize it so you can directly address the audience and leave them thinking of you as a well-prepared, confident speaker.

Outlining an Informative Speech

Two types of outlines can help you prepare to deliver your speech. The complete sentence outline provides a useful means of checking the organization and content of your speech. The speaking outline is an essential aid for delivering your speech. In this section, we discuss both types of outlines.

Two types of outlines can help you prepare to deliver your speech. The complete sentence outline provides a useful means of checking the organization and content of your speech. The speaking outline is an essential aid for delivering your speech.

The Complete Sentence Outline

A complete sentence outline may not be required for your presentation. The following information is useful, however, in helping you prepare your speech.

The complete sentence outline helps you organize your material and thoughts and it serves as an excellent copy for editing the speech. The complete sentence outline is just what it sounds like: an outline format including every complete sentence (not fragments or keywords) that will be delivered during your speech.

Writing the Outline

You should create headings for the introduction, body, and conclusion and clearly signal shifts between these main speech parts on the outline. Use standard outline format. For instance, you can use Roman numerals, letters, and numbers to label the parts of the outline. Organize the information so the major headings contain general information and the sub-headings become more specific as they descend. Think of the outline as a funnel: you should make broad, general claims at the top of each part of the outline and then tighten the information until you have exhausted the point. Do this with each section of the outline. Be sure to consult with your instructor about specific aspects of the outline and refer to your course book for further information and examples.

Using the Outline

If you use this outline as it is designed to be used, you will benefit from it. You should start the outline well before your speech day and give yourself plenty of time to revise it. Attempt to have the final, clean copies ready two or three days ahead of time, so you can spend a day or two before your speech working on delivery. Prepare the outline as if it were a final term paper.

The Speaking Outline

Depending upon the assignment and the instructor, you may use a speaking outline during your presentation. The following information will be helpful in preparing your speech through the use of a speaking outline.

This outline should be on notecards and should be a bare bones outline taken from the complete sentence outline. Think of the speaking outline as train tracks to guide you through the speech.

Many speakers find it helpful to highlight certain words/passages or to use different colors for different parts of the speech. You will probably want to write out long or cumbersome quotations along with your source citation. Many times, the hardest passages to learn are those you did not write but were spoken by someone else. Avoid the temptation to over-do the speaking outline; many speakers write too much on the cards and their grades suffer because they read from the cards.

The best strategy for becoming comfortable with a speaking outline is preparation. You should prepare well ahead of time and spend time working with the notecards and memorizing key sections of your speech (the introduction and conclusion, in particular). Try to become comfortable with the extemporaneous style of speaking. You should be able to look at a few keywords on your outline and deliver eloquent sentences because you are so familiar with your material. You should spend approximately 80% of your speech making eye-contact with your audience.

Delivering an Informative Speech

For many speakers, delivery is the most intimidating aspect of public speaking. Although there is no known cure for nervousness, you can make yourself much more comfortable by following a few basic delivery guidelines. In this section, we discuss those guidelines.

The Five-Step Method for Improving Delivery

- Read aloud your full-sentence outline. Listen to what you are saying and adjust your language to achieve a good, clear, simple sentence structure.

- Practice the speech repeatedly from the speaking outline. Become comfortable with your keywords to the point that what you say takes the form of an easy, natural conversation.

- Practice the speech aloud...rehearse it until you are confident you have mastered the ideas you want to present. Do not be concerned about "getting it just right." Once you know the content, you will find the way that is most comfortable for you.

- Practice in front of a mirror, tape record your practice, and/or present your speech to a friend. You are looking for feedback on rate of delivery, volume, pitch, non-verbal cues (gestures, card-usage, etc.), and eye-contact.

- Do a dress rehearsal of the speech under conditions as close as possible to those of the actual speech. Practice the speech a day or two before in a classroom. Be sure to incorporate as many elements as possible in the dress rehearsal...especially visual aids.

It should be clear that coping with anxiety over delivering a speech requires significant advanced preparation. The speech needs to be completed several days beforehand so that you can effectively employ this five-step plan.

Anderson, Thad, & Ron Tajchman. (1994). Informative Speaking. Writing@CSU . Colorado State University. https://writing.colostate.edu/guides/guide.cfm?guideid=52

- Games, topic printables & more

- The 4 main speech types

- Example speeches

- Commemorative

- Declamation

- Demonstration

- Informative

- Introduction

- Student Council

- Speech topics

- Poems to read aloud

- How to write a speech

- Using props/visual aids

- Acute anxiety help

- Breathing exercises

- Letting go - free e-course

- Using self-hypnosis

- Delivery overview

- 4 modes of delivery

- How to make cue cards

- How to read a speech

- 9 vocal aspects

- Vocal variety

- Diction/articulation

- Pronunciation

- Speaking rate

- How to use pauses

- Eye contact

- Body language

- Voice image

- Voice health

- Public speaking activities and games

- About me/contact

Informative speech examples

4 types of informative speeches: topics and outlines

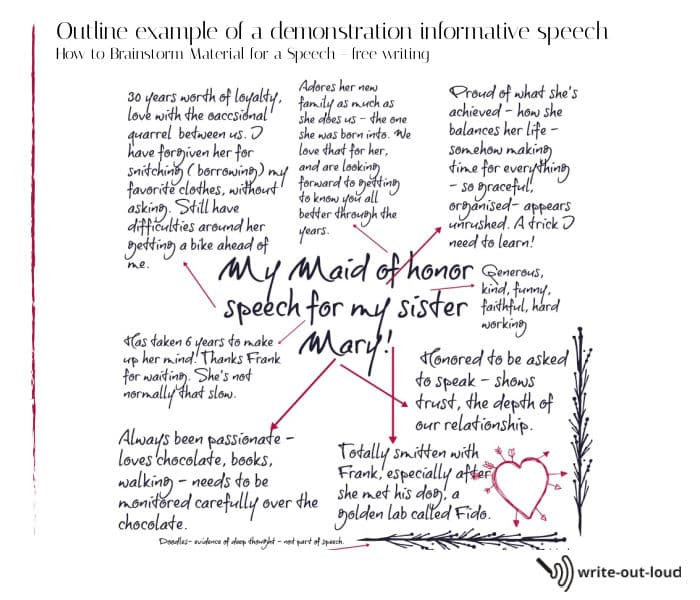

By: Susan Dugdale | Last modified: 08-05-2023

The primary purpose of an informative speech is to share useful and interesting, factual, and accurate information with the audience on a particular topic (issue), or subject.

Find out more about how to do that effectively here.

What's on this page

The four different types of informative speeches, each with specific topic suggestions and an example informative speech outline:

- description

- demonstration

- explanation

What is informative speech?

- The 7 key characteristics of an informative speech

We all speak to share information. We communicate knowledge of infinite variety all day, every day, in multiple settings.

Teachers in classrooms world-wide share information with their students.