- Instructions for authors

- Guidelines Book Reviews

- Online First Articles

- Book Reviews

- Book Series

- Reading Guides

- Conferences

Marxist Literary Criticism: An Introductory Reading Guide

Daniel Hartley

(First published in French at: http://revueperiode.net/guide-de-lecture-critique-litteraire-marxiste/ )

Marxist literary criticism investigates literature’s role in the class struggle. The best general introductions in English remain Terry Eagleton’s Marxism and Literary Criticism (Routledge, 2002 [1976]) and, a more difficult but foundational book, Fredric Jameson’s Marxism and Form (Princeton UP, 1971). The best anthology in English remains Terry Eagleton and Drew Milne’s Marxist Literary Theory: A Reader (Blackwell, 1996). The bibliographic essay that follows does not aim to be exhaustive; because it is quite long, I have indicated what I take to be the major texts of the tradition with a double asterisk and bold font: ** .

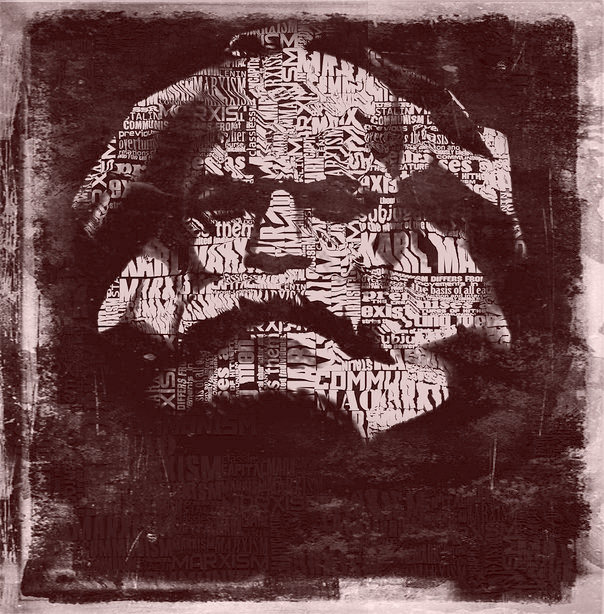

From Marx to Stalinist Russia

It is well-known that Marx himself was a voracious reader across multiple languages and that, as a young man, he composed poetry as well as an unfinished novel and fragments of a play. S.S. Prawer’s Karl Marx and World Literature (Verso, 2011 [1976]) is the definitive guide to all literary aspects of Marx’s writings. Marx and Engels also expressed views on specific literary works or authors in various contexts. Three in particular are well known: in The Holy Family (1845), Marx and Engels submit Eugène Sue’s global bestseller The Mysteries of Paris to a rigorous literary and ideological critique, which became important for Louis Althusser’s theory of melodrama (see ‘The “Piccolo Teatro”: Bertolazzi and Brecht’ in For Marx (Verso, 2005 [1965])); both Marx and Engels sent letters to Ferdinand Lassalle, a German lawyer and socialist, expressing reservations about his play Franz von Sickingen (1858-9), which they felt had downplayed the historical role of plebeian and peasant elements in the 1522-3 uprising of the Swabian and Rheinland nobility, thereby diminishing the tragic scope of his drama and causing his characters to be two-dimensional mouthpieces of history; finally, Marx planned but never actually wrote a whole volume on Balzac’s La Comédie humaine , of which Engels said that he had ‘learned more [from it] than from all the professed historians, economists, and statisticians of the period together.’ Marx and Engels’ interest in Balzac is particularly important since it suggests that literary prowess and a capacity to represent the fundamental social dynamics of a given historical period are not dependent upon an author’s self-avowed political positions (Balzac was a royalist). This point would become important for theories of realism developed by György Lukács [1] and Fredric Jameson. Various fragments of Marx and Engels’ writings on art and literature have been collected by Lee Baxandall and Stefan Morawski in Marx and Engels on Literature and Art: A Selection of Writings (Telos Press, 1973). Marx and Engels’ ultimate influence on what became ‘Marxist literary criticism’ is less a result of these isolated fragments than the historical materialist method as such.

A useful, if overly simplistic, periodisation of Marxist literary criticism has been proposed by Terry Eagleton in the introduction to his and Drew Milne’s Marxist Literary Theory: A Reader (Blackwell, 1996). Eagleton divides Marxist criticism into four kinds: anthropological, political, ideological, and economic (I shall focus on the first three). ‘Anthropological’ criticism, which he claims predominated during the period of the Second International (1889-1916), asks such fundamental questions as: what is the function of art within social evolution? What are the relations between art and human labour? What are the social functions of art and what is its relation to myth? This approach obtained (partially) in such works as G.V. Plekhanov’s Art and Social Life (Foreign Languages Press, 1957 [1912]) and Christopher Caudwell’s Illusion and Reality (Macmillan, 1937). ‘Political’ criticism dates to the Bolsheviks and their preparation for – and defence of – the Russian Revolutions of 1905 and, especially, 1917. Lenin’s essays on Tolstoy from 1908-11, collected in On Literature and Art (Progress Publishers, 1970), argue that the contradictions in Tolstoy’s work between advanced anti-capitalist critique and patriarchal, moralistic Christianity are a ‘mirror’ of late nineteenth-century Russian life and the weakness of residually feudal peasant elements of the 1905 revolution. (This argument was famously revisited by Pierre Macherey in his major Althusserian work of literary theory, Towards a Theory of Literary Production (Routledge Classics, 2006 [1966])). The most important text of this period, however, is almost certainly Trotsky’s Literature and Revolution** (Haymarket, 2005 [1925]). A landmark survey of the entire Russian literary terrain, it provides a unique record of the literary and stylistic upheavals brought about by social revolution. The book locates in literary forms and styles the ambiguous political tendencies of their authors, and is driven by the ultimate goal of producing a culture and collective subjectivity adequate to the construction of socialism.

This period of revolutionary ferment also gave rise to one of the most powerful and sophisticated intellectual schools in the history of Marxist literary criticism: the Bakhtin Circle. Led by Mikhail Mikhailovich Bakhtin (whose own relation to the Marxist tradition is ambiguous), the Circle produced subtle philosophical analyses of the social and cultural issues posed by the Russian Revolution and its degeneration into Stalinist dictatorship. Centred around the key idea of dialogism , which holds that language and literature are formed in a dynamic, conflictual process of social interaction, the Circle distinguished between monologic forms such as epic and poetry (associated with the monologism of Stalinism itself), and the novel whose heteroglossia (a polyphonic combination of social and literary idioms) and dialogism imbue it with a critical, popular resistance. Key works include Bakhtin’s Problems of Dostoevsky’s Poetics (University of Minnesota Press, 1984 [1929/ 2 nd revised edition 1963]), his four key articles on the novel (anthologised in English as The Dialogic Imagination: Four Essays** (University of Texas Press, 1981 [1934-41])), and Rabelais and His World (MIT Press, 1968 [1965]). Often overshadowed by Bakhtin, but of equal importance, are P.N. Medvedev’s masterly book-length Marxist critique of Russian formalism (which is also a social theory of literature in its own right), The Formal Method in Literary Scholarship** (Johns Hopkins University Press, 1978 [1928]), and V.N. Voloshinov’s Marxist theory of language: Marxism and the Philosophy of Language** (Harvard UP, 1986 [1929]). The latter was important to Raymond Williams’ later work (he discovered it by chance on a library shelf at Cambridge) and has informed Jean-Jacques Lecercle’s seminal A Marxist Philosophy of Language (Haymarket, 2004).

‘Western Marxism’ and Beyond

Eagleton dates his third category, ‘ideological criticism,’ to the period of ‘Western Marxism.’ The latter is a much-contested notion that became influential in the Anglophone world following the publication of Perry Anderson’s Considerations on Western Marxism (Verso, 1976), a study of intellectuals including György Lukács, Karl Korsch, Theodor W. Adorno, Max Horkheimer, Walter Benjamin, Herbert Marcuse, Jean-Paul Sartre, Louis Althusser, Antonio Gramsci, Galvano Della Volpe, and Lucio Colletti. Anderson claims that, in contradistinction to previous generations of Marxists, Western Marxism is characterised by a period of political defeat (to fascism in the 1930s), a structural divorce of Marxist intellectuals from the masses, and – consequently – a written style that is often complex, obscure or antithetical to practical political action. Whether or not one endorses Anderson’s account, it is a useful periodising category.

If Lenin and Trotsky were concerned with literature primarily as an extension of immediate political struggles, critics of the mid-century were far closer to the preoccupations of the Bakhtin Circle, understanding literature as indirectly political – not least through the ideology of form . If Soviet socialist realism, the definitive study of which is Régine Robin’s Socialist Realism: An Impossible Aesthetic (Stanford UP, 1992 [1986]), was largely indifferent to form and style and fixated on ‘transparent’ heroic-proletarian content, critics such as Adorno and Lukács focused far more on literary form and the manner in which it crystallises ideologies. In many works, this attention to form is coextensive with a dialectical approach to criticism, partly inspired by the Hegelianised Marxism of Lukács and Korsch. Such an approach is characterised by an emphasis on reflexivity and totality: it stresses the way in which ‘the [critic’s] mind must deal with its own thought process just as much as with the material it works on’ (Fredric Jameson); it holds that literary works internalise social forms, situations and structures, yet simultaneously refuse them (thereby generating a critical negativity that resists vulgar economic or political reductionism); and it takes the mediated (not external or abstract) social totality as its ultimate critical purview. As Adorno put it in an introductory lecture on the dialectic in 1958:

on the one hand, we should not be content, as rigid specialists, to concentrate exclusively on the given individual phenomena but strive to understand these phenomena in the totality within which they function in the first place and receive their meaning; and, on the other hand, we should not hypostatize this totality, this whole, in which we stand, should not introduce the whole dogmatically from without, but always attempt to effect this transition from the individual phenomenon to the whole with constant reference to the matter itself.

The pinnacle of such dialectical criticism is to be found in the work of Adorno himself. See especially: Prisms (MIT Press, 1955) and Notes to Literature I & II** (Columbia UP, 1991 & 1992 [1958 & 1961]), which contain a range of extraordinary essays, as well as the posthumously published Aesthetic Theory (Continuum, 1997 [1970]) – the definitive philosophical statement on art and the aesthetic in the immediate postwar period.

Adorno was profoundly influenced by Walter Benjamin, eleven years his senior. The pair first met in Vienna in 1923 and continued a lifelong friendship of lively intellectual debate (thoroughly analysed by Susan Buck-Morss in The Origin of Negative Dialectics (Free Press, 1977)). Benjamin’s profoundly original and essayistic work, which combines historical materialism with Jewish mysticism, ranges across a multitude of topics, with highlights including: a Kantian yet Kabbalist-influenced theory of cognition, Baroque drama and allegory, Baudelaire (a pivotal figure in Benjamin’s lifelong obsession with Paris as ‘Capital of the Nineteenth Century’), Kafka, Proust (whose mémoire involontaire he associates with surrealist shocks), Brecht (with whom he also shared a lifelong friendship), surrealism, language, and translation. In English, readers new to Benjamin might wish to consult the relevant essays in Illuminations** (Fontana, 1970) and Reflections (Schocken, 1978) as well as the theory of Baroque drama and allegory in The Origins of German Tragic Drama (Verso, 1998 [1928]). Those with a taste for completism may also wish to take on Benjamin’s enormous study of nineteenth-century Paris, consisting solely of fragments: The Arcades Project (Harvard UP, 2002 [1982]). Harvard University Press have published 4 volumes of Benjamin’s Selected Writings (2004-6).

Another towering figure of twentieth-century Marxist criticism is the Hungarian philosopher György Lukács. His 1923 work History and Class Consciousness (Merlin Press, 1971 [1923]) was hugely influential: it broke with the Second International emphasis on Marxism as a doctrine, stressing instead that Marxism is a dialectical method premised upon the category of totality, and made ‘reification’ a fundamental Marxist concept. Prior to his Marxist radicalisation, Lukács wrote two major works of literary criticism: the first, Soul and Form (Columbia UP, 2010 [1910]), is a (criminally) neglected set of passionate, tormented essays on the relation between art and life, the perfect abstractions of form versus the myriad imperfect minutiae of the human soul. These oppositions become connected to larger social contradictions between life and work, concrete and abstract, artistic fulfilment and bourgeois vocation; what Lukács is clearly seeking is a way of mediating or overcoming these oppositions, yet the tormented style is a sign that he has not yet located it. He continued these reflections in one of the truly great literary-critical works of the twentieth century: The Theory of the Novel** (MIT Press, 1971 [1920]). Contrasting the novel with the epic, Lukács argues that where the latter is the form that organically corresponds to an ‘integrated’ (i.e., non-alienated, non-reified) civilisation in which the social totality is immanently reconciled and sensually present, the novel is ‘the epic of an age in which the extensive totality of life is no longer directly given, in which the immanence of meaning in life has become a problem, yet which still thinks in terms of totality.’ The second half of the book expounds a typology of the novel, concluding with a vaguely hopeful sign that Dostoevsky may offer a way out of the impasses of bourgeois modernity.

Through the experience of World War I and the Russian Revolution, Lukács ultimately arrived at the Marxist positions of History and Class Consciousness . Crucially, his later highly influential theory of realism should be read in the context of this book’s central essay on reification, since realism for Lukács is in many ways the narrative equivalent of the de-reified (and potentially dereifying) standpoint of the proletariat. In Studies in European Realism ** (Merlin Press, 1972) and Writer and Critic (Merlin Press, 1978) (see especially the essay ‘Narrate or Describe?’), Lukács argues that the great realists (Balzac, Tolstoy, Thomas Mann) penetrate beneath the epiphenomena of daily life to reveal the hidden objective laws at work which constitute society as such. In other works, however, this attachment to realism descends into anti-modernist literary-critical dogmatism (see, e.g., The Meaning of Contemporary Realism (Merlin Press, 1963 [1958])). The other major critical work by Lukács is The Historical Novel ** (Penguin, 1969 [1937/1954]), a foundational study of the genre of the historical novel from its explosion in Walter Scott to its twentieth-century inheritors such as Heinrich Mann.

In France, the work of Sartre on committed literature is well-known. Situations I (Gallimard, 1947) collects his early texts on Faulkner, Dos Passos, Nabokov and others (recently translated as Critical Essays: Situations 1 (University of Chicago Press, 2017)). Notable here is the manner in which Sartre deduces an entire personal metaphysics from the styles and forms of these works, which he then judges against his own existentialist phenomenology of freedom and what Fredric Jameson has called his ‘linguistic optimism’ (for Sartre, everything is sayable – a position the French philosopher Alain Badiou would radicalise and mathematise). Styles like Faulkner’s, which implicitly deny this freedom, are held up for censure. The masterpiece of this period and approach is What Is Literature?** (Routledge Classics 2001, [1947]), which includes not only the well-known (and much criticised) passages on the supposed transparency of prose versus the potentially apolitical opaqueness of poetry, but also a rich and subtle history of French writers’ relations to their (virtual or actual) publics: a relation which, after the failed revolution of 1848, becomes one of denial. It concludes with a rallying cry for a ‘actual literature’ [ littérature en acte ] that would strive for a classless society in which ‘there is no difference of any kind between [a writer’s] subject and his public .’ Sartre’s work came under criticism in Roland Barthes’ Writing Degree Zero (Hill & Wang, 2012 [1953]); for Barthes, commitment occurs not at the level of content but at that of ‘writing’ [ écriture ] (or form) – though one might contest the simplistic understanding of Sartre’s argument on which this is based. More recently, these problematics have been resurrected – and challenged – by Jacques Rancière in The Politics of Literature (Polity, 2010 [2007]), which argues that the politics of literature has nothing to do with the personal political proclivities of the author; rather, literature is political because as literature it ‘intervenes into this relationship between practices and forms of visibility and modes of saying that carves up one or more common worlds .’ Readers might also consult Sartre’s major studies of individual writers, including Baudelaire (Gallimard, 1946), Saint Genet (Gallimard, 1952), and – a three-tome magnum opus – L’Idiot de la Famille (Gallimard, 1971-2).

Lucien Goldmann, a Romanian-born French critic, developed an approach that became known as ‘genetic structuralism.’ He examined the structure of literary texts to discover the degree to which it embodied the ‘world vision’ of the class to which the writer belonged. For Goldmann literary works are the product, not of individuals, but of the ‘transindividual mental structures’ of specific social groups. These ‘mental structures’ or ‘world visions’ are themselves understood as ideological constructions produced by specific historical conjunctures. In his best-known work, The Hidden God (Verso, 2016 [1955]), he connects recurring categories in the plays of Racine (God, World, Man) to the religious movement known as Jansenism, which is itself understood as the world vision of the noblesse de robe , a class fraction who find themselves dependent upon the monarchy (the ‘robe’) but, since they are recruited from the bourgeoisie, politically opposed to it. The danger of Goldmann’s work is that the ‘homologies’ he draws between work, world vision and class, are premised upon a simplistic ‘expressive causality’.

Such expressive theories of causality were, famously, one of Louis Althusser’s philosophical and political targets. Proposing a theory of the social totality as decentred, consisting of multiple discontinuous practices and temporalities (in For Marx (Verso, 2005 [1965]) and Reading Capital (Verso, 2016 [1965])), Althusser’s fragmentary writings on art and literature unsurprisingly emphasise art’s discontinuous relation to ideology and the social totality. In his 1966 ‘Letter on Art in Reply to André Daspre,’ Althusser argues that art is not simply an ideology like any other but neither is it a theoretical science: it makes us see ideology, makes it perceivable, thereby performing an ‘internal distanciation’ on ideology itself. Pierre Macherey developed this insight into an entire, extremely sophisticated theory of literary production in Towards a Theory of Literary Production** (Routledge, 2006 [1966]). For Macherey, ideology is both inscribed in and ‘redoubled’ or ‘made visible’ by literary texts just as much by what they do not say as by what they overtly proclaim: they are structured by eloquent silences . As Warren Montag has written of Macherey and Étienne Balibar’s work of this time: ‘these texts are intelligible, that is, become the objects of an adequate knowledge, only on the basis of contradictions that may be understood as their immanent cause.’ Alain Badiou published an important critique and further development of Macherey’s argument in ‘The Autonomy of the Aesthetic Process’ (1966) (appears in Badiou’s The Age of Poets (Verso, 2014)), and Terry Eagleton’s Criticism and Ideology (New Left Books, 1976) – a major Althusserian intervention in the British literary critical scene – was strongly influenced by Macherey’s work. For Badiou’s later writings on literature, see Handbook of Inaesthetics (Stanford UP, 2004 [1998]), On Beckett (Clinamen Press, 2002), and The Age of the Poets (Verso, 2014); Jean-Jacques Lecercle has traced these developments in Badiou and Deleuze Read Literature (Edinburgh UP, 2012). Macherey continued his own literary critical trajectory in À quoi pense la littérature? (PUF, 1990), Proust. Entre littérature et philosophie (Éditions Amsterdam, 2013), and Études de philosophie littéraire (De l’incidence éditeur, 2014).

British and US-American Marxist Literary Criticism: Raymond Williams, Terry Eagleton and Fredric Jameson

Raymond Williams was perhaps the most important British literary critic of the twentieth century. For a sense of his entire career, see the book-length interviews conducted by the editorial board of the New Left Review in Politics and Letters (Verso, 2015 [1979]). Of the vast range of his writings on literature, Marxism and Literature** (Oxford UP, 1977) is the most important from the perspective of literary criticism. It is the culmination of Williams’ increasing engagement, through the rise of the New Left from the mid-1950s, with the whole range of ‘Western Marxist’ texts discussed above, many of which were slowly being translated into English throughout the 1960s and 70s. Williams’ consistent manoeuvre in this book is to suggest the ways in which traditionally ‘Marxist’ theories of culture and literature remain residually idealist. Williams here formulates his mature positions on several of his key conceptual innovations: selective tradition, ‘dominant, residual and emergent’ (the three-fold temporality of the historical present), structure of feeling, and alignment. Yet the book must also be read in the context of the previous ground-breaking literary critical works that made it possible: The Long Revolution (Chatto & Windus, 1961), a theory of modernity as viewed from the perspective of the sociology of literature and artistic production; Modern Tragedy (Verso, 1979 [1966]), which combines a Marxist theory of tragedy with a powerful justification of revolution as our modern tragic horizon; Drama from Ibsen to Brecht (Penguin, 1973 [1952/ 1964]), a materialist theory of modern drama; The English Novel From Dickens to Lawrence (Chatto & Windus, 1970), a social history of the English novel (designed, in part, to challenge the hegemony of F. R. Leavis’ The Great Tradition (Chatto & Windus, 1948)); and – most importantly – The Country and the City ** (Oxford UP, 1973), a majestic literary and social history of urbanisation and the capitalist development of town and country relations. In his later work, Williams also wrote much to challenge prevailing idealist theories of modernism: see The Politics of Modernism (Verso, 1989).

Terry Eagleton was Williams’ student at Cambridge. Coming from a working-class Catholic background, Eagleton’s early writings were primarily concerned with Catholic theories of the body and language. A turning point came with the publication of Criticism and Ideology** (New Left Books, 1976), which signalled Eagleton’s conversion to Althusserianism and his intellectual break with Williams (it contains a now notorious chapter in which he accuses Williams of being a romantic, idealist, empiricist, populist!), though it had been preceded by the Goldmannian Myths of Power: A Marxist Study of the Brontës (Palgrave, 2005 [1975]). In the 1980s, Eagleton became increasingly interested in the revolutionary potential of criticism itself, partly by way of Walter Benjamin’s readings of Brecht (see Walter Benjamin, or Towards a Revolutionary Criticism (Verso, 1981)), and partly via feminism ( The Rape of Clarissa: Writing, Sexuality, and Class Struggle in Samuel Richardson (Blackwell, 1982)). He has written a wide-ranging trilogy on Irish cultural history, but his most important mid-to-late works are arguably The Ideology of the Aesthetic ** (Blackwell, 1990), a detailed critical history of the entire aesthetic tradition, and Sweet Violence: The Idea of the Tragic (Blackwell, 2002), a major Marxist reconceptualisation of tragic theory and literature. An overview of his life and work can be found in the book-length interview The Task of the Critic: Terry Eagleton in Dialogue (Verso, 2009).

Fredric Jameson, perhaps best-known for his theory of postmodernism ( Postmodernism, or, the Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism (Durham UP, 1991), was integral in the dissemination of ‘Western Marxist’ ideas in the Anglophone world. As mentioned at the outset, Marxism and Form** (Princeton UP, 1971) is a key introduction to many of these ideas. It includes detailed chapters on Adorno, Benjamin, Bloch, Lukács, and Sartre, as well as a major methodological essay on ‘dialectical criticism’. Jameson tested many of these ideas in a highly unusual work of ideological recuperation: Fables of Aggression: Wyndham Lewis, the Modernist as Fascist (University of California Press, 1979). Perhaps Jameson’s most enduring work, however, is The Political Unconscious** (Cornell UP, 1981). Based on a modernised version of the medieval system of allegory, it develops a model of reading based on three levels: the text as symbolic act, the text as ‘ideologeme’ (‘the smallest intelligible unit of the essentially antagonistic collective discourses of social classes’) and the text as ‘ideology of form’. Its ultimate claim is that every literary text, via a system of (non-expressive) allegorical mediations, can be linked back to the non-transcendable horizon of History as class struggle. Jameson is also an important theorist of modernism, as witness his major work A Singular Modernity** (Verso, 2002) and the essay collection The Modernist Papers (Verso, 2007). His most important recent literary critical work is The Antinomies of Realism (Verso, 2013). Jameson also published a highly controversial article, ‘Third-World Literature in the Era of Multinational Capitalism’ ( Social Text , 1986), which alone has given rise to a vast secondary literature (the best-known critique of it being Aijaz Ahmad’s in In Theory: Classes, Nations, Literatures (Verso, 1992)). Jameson is undoubtedly the most important cultural critic of the late twentieth century.

Contemporary Criticism

It is impossible to do justice to the range and richness of contemporary Marxist criticism, so I can only hope to indicate a few important works. Franco Moretti has been an influential figure in the field. His work on the Bildungsroman foregrounded the way in which the symbolic form of ‘youth’ mediated the contradictions of modernity and effected the transition from the heroic subjectivities of the Age of Revolution to the mundane and unheroic normality of everyday bourgeois life ( The Way of the World: The Bildungsroman in European Culture** (Verso, 1987)). His study of the ‘modern epic,’ meanwhile, focused on such texts as Goethe’s Faust , Melville’s Moby Dick and Gabriel García Márquez’ One Hundred Years of Solitude , arguing that they are ‘ world texts, whose geographical frame of reference is no longer the nation-state, but a broader entity – a continent, or the world-system as a whole’ ( The Modern Epic: The World-System from Goethe to García Márquez (Verso, 1996)). In a move that would prove influential for materialist theories of ‘world literature’ (including his own), Moretti employs the categories of Immanuel Wallerstein’s world-systems analysis to suggest that such ‘world texts’ or ‘modern epics,’ whilst unknown to the relatively homogeneous states of the core are typical of the semi-periphery where combined development prevails. [2] Moretti has since extended this ‘geography of literary forms’ in ‘Conjectures on World Literature’** ( New Left Review , 2000). Taking its cue from Goethe and Marx’s remarks on Weltliteratur , and combining these with insights drawn from the Brazilian Marxist critic Roberto Schwarz, ‘Conjectures’ holds that world literature is ‘[o]ne, and unequal: one literature … or perhaps, better, one world literary system (of inter-related literatures); but a system which is different from what Goethe and Marx had hoped for, because it’s profoundly unequal.’ Moretti’s most important work, though, is arguably his most recent publication: The Bourgeois: Between History and Literature** (Verso, 2013), a socio-literary study of the figure of the bourgeois, whose true ‘hero’ is the rise of literary prose.

The most significant of Moretti’s inheritors is the Warwick Research Collective (WReC), whose book Combined and Uneven Development: Towards a New Theory of World-Literature (Liverpool UP, 2015) aims to ‘resituate the problem of “world literature,” considered as a revived category of theoretical enquiry, by pursuing the literary-cultural implications of the theory of combined and uneven development.’ Fusing Fredric Jameson’s ‘singular modernity’ thesis with a Moretti-inflected world-systems analysis and Trotsky’s theory of combined and uneven development, the Warwick Research Collective defines world-literature as ‘ the literature of the world-system ’. World-literature (with a hyphen to show its fidelity to Wallersteinian world-systems analysis) is that literature which ‘registers’ in form and content the modern capitalist world-system. The book is also an intervention into debates on the definition of modernism. If ‘modernisation’ is understood as the ‘imposition’ of capitalist social relations on ‘cultures and societies hitherto un- or only sectorally capitalised’, and ‘modernity’ names ‘the way in which capitalist social relations are “lived”’, then ‘modernism’ is that literature which ‘encodes’ the lived experience of the ‘capitalisation of the world’ produced by modernisation.

Individual members of the Warwick Research Collective have also made important contributions to what might (problematically) be termed ‘Marxist postcolonial theory’. Benita Parry’s Postcolonial Studies: A Materialist Critique (Routledge, 2004) brings together a series of sophisticated essays which, whilst recognising the significance of much work done under the emblem of postcolonial studies, suggest that the material impulses of colonialism – its appropriation of physical resources, exploitation of human labour and institutional repression – have been omitted from mainstream postcolonial work (by Subaltern Studies, Edward Saïd, Homi Bhabha and Gayatri Chakracorty Spivak). Neil Lazarus’ The Postcolonial Unconscious (Cambridge UP, 2011) not only extends this critique but attempts to reconstruct the entire field of postcolonial studies by developing new Marxist concepts attentive to the insights of postcolonial theory. Upamanyu Pablo Mukherjee has likewise charted new terrain for Marxist postcolonial studies, but has done so with increased sensitivity to ecology (see Postcolonial Environments Nature: Culture and the Contemporary Indian Novel in English (Palgrave, 2010)). This approach has been strengthened by Sharae Deckard’s ambitious research project on ‘world-ecological literature’ (for a programmatic summary, see her forthcoming ‘Mapping Planetary Nature: Conjectures on World-Ecological Fiction’).

In other recent work:

- Alex Woloch has developed a theory of minor characters and protagonists in the realist novel that connects the ‘asymmetric structure of characterization – in which many are represented but attention flows to a delimited center’ to the ‘competing pull of inequality and democracy within the nineteenth-century bourgeois imagination’ ( The One vs. the Many , Princeton UP, 2003).

- Anna Kornbluh has offered a nuanced materialist account of realism’s formal mediations and ‘realisations’ of finance in Realizing Capital: Financial and Psychic Economies in Victorian Form (Fordham University Press, 2014).

- Joshua Clover has argued that the period from the 1970s to the economic crisis of 2007-8 should be understood as the (Braudelian) ‘Autumn of the system.’ His fundamental thesis is ‘that an organizing trope of Autumnal literature is the conversion of the temporal to the spatial ’. It is this conversion that non -narrative forms such as poetry are better able to grasp and figure forth’ (‘Autumn of the System: Poetry and Financial Capital.’ JNT: Journal of Narrative Theory , 2011).

- In The Matter of Capital (Harvard UP, 2011) Christopher Nealon emphasises the ubiquity and variety of thematic, formal and intertextual poetic reflections upon capitalism across poetry of the ‘American century.’ He shows that poets as diverse as Ezra Pound, W. H. Auden, John Ashbery, Jack Spicer, the Language poets, Claudia Rankine and Kevin Davies ‘have at the center of their literary projects an attempt to understand the relationship between poetry and capitalism, most often worked out as an attempt to understand the relationship of texts to historical crisis’.

- Ruth Jennison’s The Zukofsky Era (Johns Hopkins UP, 2012), argues that ‘the Objectivists of the Zukofsky Era inherit the first [modernist] generation’s experimentalist break with prior systems of representation, and … strive to adequate this break to a futurally pointed content of revolutionary politics.’

- Sarah Brouillette has published a range of important work on the history of the book market and creative industries. See especially, Literature and the Creative Economy (Stanford UP, 2014).

- My own book, The Politics of Style: Towards a Marxist Poetics (Brill/ Haymarket, 2017), develops a materialist theory of style through an immanent critique of the work of Raymond Williams, Terry Eagleton and Fredric Jameson.

[1] Sometimes rendered in English as ‘Georg Lukács’.

[2] For explanations of these complex terms (world-systems analysis, core, semi-periphery), see Wallerstein’s World-Systems Analysis: An Introduction (Duke UP, 2004).

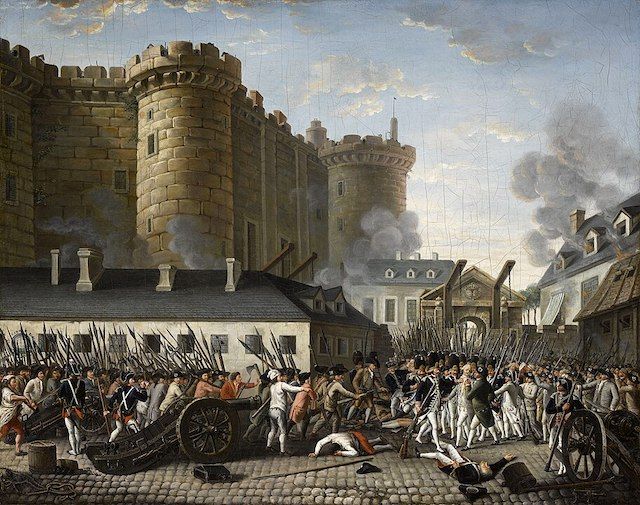

Image derived from “Marxism” by rdesign812 is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Historical Materialism is a Marxist journal, appearing four times a year, based in London. Founded in 1997 it asserts that, not withstanding the variety of its practical and theoretical articulations, Marxism constitutes the most fertile conceptual framework for analysing social phenomena, with an eye to their overhaul. In our selection of material we do not favour any one tendency, tradition or variant. Marx demanded the ‘Merciless criticism of everything that exists’: for us that includes Marxism itself.

- Submissions

- Subject List

- Take a Tour

- For Authors

- Subscriber Services

- Publications

- African American Studies

- African Studies

- American Literature

- Anthropology

- Architecture Planning and Preservation

- Art History

- Atlantic History

- Biblical Studies

- British and Irish Literature

- Childhood Studies

- Chinese Studies

- Cinema and Media Studies

- Communication

- Criminology

- Environmental Science

- Evolutionary Biology

- International Law

- International Relations

- Islamic Studies

- Jewish Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Latino Studies

- Linguistics

Literary and Critical Theory

- Medieval Studies

- Military History

- Political Science

- Public Health

- Renaissance and Reformation

- Social Work

- Urban Studies

- Victorian Literature

- Browse All Subjects

How to Subscribe

- Free Trials

In This Article Expand or collapse the "in this article" section Marxism

Introduction, general overviews.

- The Frankfurt School

- Beyond the Frankfurt School

- Marxist-Inspired Existentialism and Postmodernism

- Historically Oriented Accounts

- Feminist Theory

- Eco-Feminism

- Marxist Anti-Racism/Critical Race Theory

- Socialist Feminist/Anti-Racist Critical Race Theory

- Critical Theory in Environmentalism

- Beyond Critical Theory

- Contemporary Marxist Theory

Related Articles Expand or collapse the "related articles" section about

About related articles close popup.

Lorem Ipsum Sit Dolor Amet

Vestibulum ante ipsum primis in faucibus orci luctus et ultrices posuere cubilia Curae; Aliquam ligula odio, euismod ut aliquam et, vestibulum nec risus. Nulla viverra, arcu et iaculis consequat, justo diam ornare tellus, semper ultrices tellus nunc eu tellus.

- Antonio Gramsci

- Bertolt Brecht

- Chantal Mouffe

- Critical Theory

- Cultural Materialism

- Frankfurt School

- Slavoj Žižek

- Socialist/Marxist Feminism

- Terry Eagleton

- Theodor Adorno

- Walter Benjamin

Other Subject Areas

Forthcoming articles expand or collapse the "forthcoming articles" section.

- Black Atlantic

- Postcolonialism and Digital Humanities

- Find more forthcoming articles...

- Export Citations

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Marxism by Wendy Lynne Lee LAST REVIEWED: 26 July 2017 LAST MODIFIED: 26 July 2017 DOI: 10.1093/obo/9780190221911-0031

Marxism encompasses a wide range of both scholarly and popular work. It spans from the early, more philosophically oriented, Karl Marx of the Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844 and the German Ideology , to later economic works like Das Kapital , to specifically polemical works like The Communist Manifesto . While our focus is not Marx’s own contributions to philosophy or political economy, per se, it is important to note that the sheer breadth of scholarship rightly regarded as “Marxist” or “Marxian,” owes itself to engagement with texts ranging across the works of a younger, more explicitly Hegelian, “philosophical Marx” to those of the more astute, if perhaps more cynical, thinker of his later work, to the revolutionary of the Manifesto’s “Workers unite!” Hence, while it is not surprising to see an expansive literature that includes feminist, anti-racist, and environmental appropriations of Marx, it is also not unexpected to see considerable conflict and variation as a salient characteristic of any such compilation. Indeed, it is difficult to capture the full range of what “Marxism” includes, and it is thus important to acknowledge that to some extent the choice of organizing category is destined to be arbitrary. But this may be more a virtue than a deficit since not only have few thinkers had more significant global impact, few have seen their work applied to a broader range of issues, philosophic, economic, geopolitical, environmental, and social. Marx’s conviction that the point of philosophy is not merely to know the world but to change it for the good continues to infuse the essential bone marrow of virtually every major movement for economic, social, and now environmental justice on the beleaguered planet. Although his principle focus may have been the emancipation of workers, the model he articulates for understanding the systemic injustices inherent to capitalism is echoed in Marxist analyses of oppression across disciplines as otherwise diverse as political economy, feminist theory, anti-slavery analyses, aesthetic experience, liberation theology, and environmental philosophy. To be sure, Marxism is not Marx; it is not necessarily even a reflection of Marx’s own convictions. But however far flung from Marx’s efforts to turn G. F. W. Hegel on his head, Marxism has remained largely true to its central objective, namely, to demonstrate the dehumanizing character of an economic system whose voracious quest for capital accumulation is inconsistent not only with virtually any vision of the good life, but with the necessary conditions of life itself.

For a general overview of Karl Marx, look to Sidney Hook’s Toward the Understanding of Karl Marx: A Revolutionary Interpretation (1933), Isaiah Berlin’s Karl Marx (1963), Louis Dupré’s The Philosophical Foundations of Marxism (1966), Frederic Bender’s Karl Marx: The Essential Writings (1972), or David Mc’Lellan’s Karl Marx: Selected Writings (1977). General overviews of Marxism present, however, a more daunting challenge. These range not only over an expansive array of subject matter, but also across a wide and diverse span of application. A distinctive feature of Marxist scholarship is the effort to include interpretation of Marx’s original arguments and their application to a range of issues. Georg Lukacs offers an example of this strategy in History and Class Consciousness ( Lukacs 1966 ). Louis Althusser takes a similar tack in Reading Kapital ( Althusser 1998 ) and For Marx ( Althusser 2006 ) arguing for an important philosophical transition between the young Marx and the Marx of Kapital —that Marxism should reflect this “epistemological break.” Throughout a career which included Marx and Literary Criticism ( Eagleton 1976 ), Why Marx was Right ( Eagleton 2011 ), and Marx and Freedom ( Eagleton 1997 ), Terry Eagleton demonstrates why Marx and Marxism remain relevant to our reading of literature. In On Marx ( Lee 2002 ), Wendy Lynne Lee endeavors to bridge the gap between general introduction and application via contemporary examples relevant to Marxist scholars and civic activists across a range of disciplines and accessibility. John Sitton’s Marx Today ( Sitton 2010 ) takes a historically contextualized approach to contemporary socialist theorizing via The Communist Manifesto . Through a diverse selection including Albert Einstein’s “Why Socialism?,” John Bellamy Foster and Robert McChesney’s “Monopoly-Finance Capital and the Paradox of Accumulation,” and Terry Eagleton’s “Where Do Postmodernists Come From?,” Sitton demonstrates the continuing relevance of the Marxist commitment to make philosophy speak to real world issues. One of the best general works, however, is Kevin M. Brien’s Marx, Reason, and the Art of Freedom ( Brien 2006 ). Brien argues that Marxism can and should proceed from the assumption that, contrary to Althusser, Marx can be read as a coherent whole. As Marx Wartofsky puts it, Brien’s reading of Marx creates opportunities to theorize an internally consistent Marxism, but also incites “lively criticism.” Lastly, though perhaps less a general introduction to Marxism than to a Marxist view of political/economic revolution, the Norton Critical Edition of The Communist Manifesto ( Bender 2013 ) includes essays situating Marx’s incendiary pamphlet in the history of Marxist scholarship. It includes a rich selection of pieces devoted to themes including the revolutionary potential of Marx’s critique of capitalism (Mihailo Markoviç), his theory of wage labor (Ernest Mandel), Marxist ethics (Howard Selsam), and the applicability of Marxist analyses to contemporary dilemmas (Slavoj Zizek, Joe Bender).

Althusser, Louis. Reading Kapital . London: New Left Review/Verso, 1998.

In Reading Kapital Althusser argues for an epistemological break between the young Marx and the Marx of Kapital . Marxist analyses, according to Althusser, should not only reflect this maturation in Marx’s thinking, but should seek to understand and capitalize on the important changes in Marx’s view of capitalism.

Althusser, Louis. For Marx . London: New Left Review/Verso, 2006.

In For Marx Althusser continues his argument for an epistemological break between the young Marx and the Marx of Kapital utilizing specifically Freudian and Structuralist concepts to support his analysis. The focus here is on the “scientific” Marx as opposed to the younger, more Hegelian thinker. But, as Althusserlater acknowledged, more attention needed to be paid to class struggle.

Bender, Frederic, ed. The Communist Manifesto: A Norton Critical Edition . New York: Norton, 2013.

The Norton Critical Edition of The Communist Manifesto includes essays situating Marx’s incendiary pamphlet in the history of Marxist scholarship. It includes a rich selection of pieces devoted to themes including the revolutionary potential of Marx’s critique of capitalism (Mihailo Markoviç), his theory of wage labor (Ernest Mandel), a socialist feminist interpretation (Wendy Lynne Lee), a Marxist-inspired ethics (Howard Selsam), and an analysis of the applicability of Marxist work to contemporary dilemmas (Slavoj Zizek, Joe Bender).

Brien, Kevin M. Marx, Reason, and the Art of Freedom . Amherst, NY: Humanity Books, 2006.

In Marx, Reason, and the Art of Freedom Brien argues that Marxism can and should proceed from the assumption that Marx can be read as a coherent whole, that is, that there’s no “epistemological break” as identified by Althusser. As Marx scholar Marx Wartofsky puts it, Brien’s reading of Marx creates opportunities to theorize an internally consistent Marxism, but also incites “lively criticism.”

Eagleton, Terry. Marx and Literary Criticism . Oakland: University of California Press, 1976.

In Marx and Literary Criticism , Eagleton’s seminal work, he shows how and why it is that Marx is relevant to our reading not only of political economy, but to a wide array of literature. Among other topics, he offers an analysis of the relationship of literature to its historical context, and of literature to political activity. He also situates Marxist critique in the larger context of understanding the human relationship to society and civilization.

Eagleton, Terry. Marx and Freedom . London: Phoenix House, 1997.

In Marx and Freedom , Eagleton continues his critique of capitalism, arguing that freedom means not only liberation from material constraints to more creative praxis, but emancipation from capitalist labor as a variety of alienation. Eagleton incorporates a very rich account of individual perception and activity as key to realizing freedom.

Eagleton, Terry. Why Marx Was Right . New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2011.

In Why Marx Was Right Eagleton adopts a more combative tone, defending against the claim that Marxism has outlived its usefulness. He takes on a number of common objections to Marxism, including that it leads to tyranny, or that it’s ideologically reductionistic.

Lee, Wendy Lynne. On Marx . Belmont, CA: Wadsworth, 2002.

Lee’s aim is to offer an introduction to Marx and to Marxism accessible to a wide range of disciplines and audiences. On Marx also provides concise possible applications of Marxist themes for use in environmental philosophy and feminist theory with an emphasis on bridging the gap between philosophical comprehension and activist application—theory and praxis.

Lukacs, Georg. History and Class Consciousness: Studies in Marxist Dialectics . Cambridge, MA: MIT, 1966.

History and Class Consciousness offers a classic example of a strategy common in Marx scholarship, namely, an interpretation of Marx’s work (particularly the concept of alienation), the influence of G. W. F. Hegel on Marx, and an application of Marx to contemporary themes, in Lukacs’s case, the defense of Bolshevism.

Sitton, John. Marx Today: Selected Works and Recent Debates . New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010.

DOI: 10.1057/9780230117457

Marx Today takes a historically contextualized approach to contemporary socialist theorizing via The Communist Manifesto , among other Marx’s works. Aimed at a broad audience, this anthology includes both sympathetic and critical readings. Sitton’s selections demonstrate the relevance of the Marxist commitment to make philosophy speak to real world issues.

back to top

Users without a subscription are not able to see the full content on this page. Please subscribe or login .

Oxford Bibliographies Online is available by subscription and perpetual access to institutions. For more information or to contact an Oxford Sales Representative click here .

- About Literary and Critical Theory »

- Meet the Editorial Board »

- Achebe, Chinua

- Adorno, Theodor

- Aesthetics, Post-Soul

- Affect Studies

- Afrofuturism

- Agamben, Giorgio

- Anzaldúa, Gloria E.

- Apel, Karl-Otto

- Appadurai, Arjun

- Badiou, Alain

- Baudrillard, Jean

- Belsey, Catherine

- Benjamin, Walter

- Bettelheim, Bruno

- Bhabha, Homi K.

- Biopower, Biopolitics and

- Blanchot, Maurice

- Bloom, Harold

- Bourdieu, Pierre

- Brecht, Bertolt

- Brooks, Cleanth

- Caputo, John D.

- Chakrabarty, Dipesh

- Conversation Analysis

- Cosmopolitanism

- Creolization/Créolité

- Crip Theory

- de Certeau, Michel

- de Man, Paul

- de Saussure, Ferdinand

- Deconstruction

- Deleuze, Gilles

- Derrida, Jacques

- Dollimore, Jonathan

- Du Bois, W.E.B.

- Eagleton, Terry

- Eco, Umberto

- Ecocriticism

- English Colonial Discourse and India

- Environmental Ethics

- Fanon, Frantz

- Feminism, Transnational

- Foucault, Michel

- Freud, Sigmund

- Frye, Northrop

- Genet, Jean

- Girard, René

- Global South

- Goldberg, Jonathan

- Gramsci, Antonio

- Greimas, Algirdas Julien

- Grief and Comparative Literature

- Guattari, Félix

- Habermas, Jürgen

- Haraway, Donna J.

- Hartman, Geoffrey

- Hawkes, Terence

- Hemispheric Studies

- Hermeneutics

- Hillis-Miller, J.

- Holocaust Literature

- Human Rights and Literature

- Humanitarian Fiction

- Hutcheon, Linda

- Žižek, Slavoj

- Imperial Masculinity

- Irigaray, Luce

- Jameson, Fredric

- JanMohamed, Abdul R.

- Johnson, Barbara

- Kagame, Alexis

- Kolodny, Annette

- Kristeva, Julia

- Lacan, Jacques

- Laclau, Ernesto

- Lacoue-Labarthe, Philippe

- Laplanche, Jean

- Leavis, F. R.

- Levinas, Emmanuel

- Levi-Strauss, Claude

- Literature, Dalit

- Lonergan, Bernard

- Lotman, Jurij

- Lukács, Georg

- Lyotard, Jean-François

- Metz, Christian

- Morrison, Toni

- Mouffe, Chantal

- Nancy, Jean-Luc

- Neo-Slave Narratives

- New Historicism

- New Materialism

- Partition Literature

- Peirce, Charles Sanders

- Philosophy of Theater, The

- Postcolonial Theory

- Posthumanism

- Postmodernism

- Post-Structuralism

- Psychoanalytic Theory

- Queer Medieval

- Race and Disability

- Rancière, Jacques

- Ransom, John Crowe

- Reader Response Theory

- Rich, Adrienne

- Richards, I. A.

- Ronell, Avital

- Rosenblatt, Louse

- Said, Edward

- Settler Colonialism

- Stiegler, Bernard

- Structuralism

- Theatre of the Absurd

- Thing Theory

- Tolstoy, Leo

- Tomashevsky, Boris

- Translation

- Transnationalism in Postcolonial and Subaltern Studies

- Virilio, Paul

- Warren, Robert Penn

- White, Hayden

- Wittig, Monique

- World Literature

- Zimmerman, Bonnie

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

Powered by:

- [66.249.64.20|185.80.151.41]

- 185.80.151.41

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Marxist Literary Criticism: An Introductory Reading Guide

2019, Historical Materialism

Appeared online here: http://www.historicalmaterialism.org/index.php/reading-guides/marxist-literary-criticism-introductory-reading-guide?fbclid=IwAR2vioz8HnlwSHpgoUdnH6cnwFNE7D2gb7juShyG0-z2LxNmyzYevqJLH8I

Related Papers

Ramkrishna Bhattacharya

An attempt to dispel the notion that Marxist literary criticism is nothing but the sociology of literature. On the contrary, the joint yardstick of the historical and the aesthetic is of essence.

Journal of Teaching and Research in English Literature

Aditya Kumar Panda

In 20th century, literary criticism has witnessed influences from many schools of critical inquiries. One of the major schools is Marxist literary criticism. This paper highlights the major tenets of Marxist literary criticism. In other words, it studies the Marxist approach to literature.

complex, more than Shakespeare because we know more about the lives of women—Jane Austen and Virginia Woolf included. Both the victimization and the anger experienced by women are real, and have real sources, everywhere in the environment, built into society, language, the structures of thought. They will go on being tapped and explored by poets, among others. We can neither deny them, nor will we rest there. A new generation of women poets is already working out of the psychic energy released when women begin to move out towards what the feminist philosopher Mary Daly has described as the "new space" on the boundaries of patriarchy. 8 Women are speaking to and of women in these poems, out of a newly released courage to name, to love each other, to share risk and grief and celebration. To the eye of a feminist, the work of Western male poets now writing reveals a deep, fatalistic pessimism as to the possibilities of change, whether societal or personal, along with a familiar and threadbare use of women (and nature) as redemptive on the one hand, threatening on the other; and a new tide of phallocentric sadism and overt woman-hating which matches the sexual brutality of recent films. "Political" poetry by men remains stranded amid the struggles for power among male groups; in condemning U.S. imperialism or the Chilean junta the poet can claim to speak for the oppressed while remaining, as male, part of a system of sexual oppression. The enemy is always outside the self, the struggle somewhere else. The mood of isolation, self-pity, and self-imitation that pervades "nonpolitical" poetry suggests that a profound change in masculine consciousness will have to precede any new male poetic—or other—inspiration. The creative energy of patri-archy is fast running out; what remains is its self-generating energy for destruction. As women, we have our work cut out for us. 1976 In the preface to his book, Eagleton writes ironically: "No aoubt we shall soon see Marxist criticism comfortably wedged between Freudian and mythological approaches to literature, as yet one more stimulating academic 'approach,' one more well-tilled field of inquiry for students to tramp." He, urges against such an attitude, believing it "dangerous" to the centrality of Marxism as an agent of social change. Despite his warning, however, and because of his claims for the significance of Marxist criticism, Eagleton's opening chapters, dealing with tuo topics central to literary criticism, are here presented for some thoughtful "tramping." "Marxism," which in some quarters remains a pejorative term, is in fact an indispensable concern in modern intellectual history. Developed primarily as a way of examining historical, economic, and social issues, Marxist doctrine does not deal explicitly with theories of literature; consequently, there is no one orthodox Marxist school (as there is an orthodox Freudianism), but rather a diversity of Marxist readings. Eagleton's own discussion partly illustrates this diversity: he uses the familiar derogatory term "vulgar Marxism" to refe-to the simplistic deterministic notion that a literary work is nothing more than the direct product of its socioeconomic base. Aware also of how Marxist theory can be perverted, Eagleton in another chapter 's scorn-" ful of such politically motivated corruptions as the Stalinist doctrine From Marxism and Literary Criticism;

Modern Language Review, 78, 632-4

Michael Wilding

Here is an overview of different aspects of Marxist literary criticism From Marx's own works through Engels, Lenin, Trotsky, Mao Zedong, Plekhanov, Mehring and Gramsci down to Lukacs.

Asian journal of multidisciplinary studies

junaid shabir

Marxism gives a new dimension to the study of literature by laying stress upon the importance of history within which various social and cultural trends emerge. It helps us to gain a practical and systematic world view by devoting self to the intense study of history. It evaluates the modern society from a unique prism of master-slave view— Bourgeoisie and Proletariat. The account of the horrid tale of proletariat’s oppression is recorded well in the seminal works of Karl Marx like Das Capital , The Communist Manifesto , The German Ideology and so on. A literary artist is deeply affected by the social, economic and political upheavels in the society and tries to give a true account of it in his literary works. Marxism helps the artist to unravel the self interest of the bourgeoisie by putting an end to the patriarchal and feudal idyllic relations which shook the ecstacies of brutal exploitation coated with religious fervor and sentimentalism. In this paper, an attempt has been made...

Robert Kashindi

Marxism in Literary or Art in our 21 St centuries is built around a debate of methodology and application when a critic is requested to evaluate a literary text or genre. Though disparities of thoughts in the point of views of some scholars such as: Georg Lukacs, Karl Korsch, Antonio Gramsci, Louis Althusser etc. have been involved in scientific debates whether Marxism as a sociological approach finds a better reliable application in literature. Marxism as a political ideology of Karl Marx was not designed for literary study, literature in terms of form, politics, ideology, and consciousness, numbers of research skills are required for a critic in almost literary components. While the question of methodology and application in literary analysis is still unsettled in the areas of literary studies so, it appears very difficult and ambiguous to some literary students and English teachers in our local universities in Bukavu (DRC) when prior involving in literary evaluation. Furthermore,...

Tiyas Mondal

Wan Anayati

DOI: 10.21276/sjahss.2018.6.5.11 Abstract: This paper attempts to elaborate the milieu of Marxist criticism by exposing the types of Marxist movements and ideologies occurred throughout the history. The objective of this study is to present various milieus of Marxism that can be incorporated in the realm of literary discussions. Therefore, the authors utilized the qualitative descriptive approach by selecting various texts that encompass the existence of Marxism criticism. The authors believe that the exploration of this research brings a comprehensive alternative toward Marxist as one of the school of literary criticisms taught in every English department. Marxism is a scientific theory of human societies and of the practice of transforming them; and what that means, rather more concretely, is that the narrative Marxism has to deliver is the story of the struggles of men and women to free themselves from certain forms of exploitation and oppression (Eagleton 12). Furthermore, it is...

RELATED PAPERS

Alexandra Chavarria Arnau

Bioinformatics & Computational Biology

ernesto gomez

IFAC-PapersOnLine

Alexander Raikov

GENEL TÜRK TARİHİ ARAŞTIRMALARI DERGİSİ

Dr. ibrahim güneş

Jurnal Neraca Peradaban

sarwani sarwani

International Journal of Engineering Research and

kedharnath sairam

International Journal of Geosciences

Mikhail Nilov

Japanese Journal of Clinical Oncology

Mitsuru Sasako

Journal of Public Health

Salma Afifi

Jurnal Ilmiah Psikologi Terapan

EVA MEIZARA

Theresa Handwerk

실시간카지노 토토사이트

IEEE Transactions on Power Electronics

Johann Kolar

Baltic Journal of Modern Computing

RePEc: Research Papers in Economics

Taofik M Ibrahim

Bioelectrochemistry

Julius Cirak

Biomedical Journal of Scientific & Technical Research

nahid sarlak

Notulae Botanicae Horti Agrobotanici Cluj-Napoca

Monica Bodea

International Journal of Public Health

Priscilla Abechi

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

- Directories

- General Literary Theory & Criticism Resources

- African Diaspora Studies

- Critical Disability Studies

- Critical Race Theory

- Deconstruction and Poststructuralism

- Ecocriticism

- Feminist Theory

- Indigenous Literary Studies

- Marxist Literary Criticism

- Narratology

- New Historicism

- Postcolonial Theory

- Psychoanalytic Criticism

- Queer and Trans Theory

- Structuralism and Semiotics

- How Do I Use Literary Criticism and Theory?

- Start Your Research

- Research Guides

- University of Washington Libraries

- Library Guides

- UW Libraries

- Literary Research

Literary Research: Marxist Literary Criticism

What is marxist literary criticism.

"A form of cultural criticism that applies Marxist theory to the interpretation of cultural texts, using the key concepts of historical materialism, political economy, and ideology."

Brief Overviews:

- " Marxist Criticism ." Twentieth-Century Literary Criticism.

- " Marxist Criticism ." A Dictionary of Critical Theory .

- " Marxist Theory and Criticism ." The Johns Hopkins Guide to Literary Theory and Criticism.

Notable Scholars:

Theodor Adorno

(With Walter Benjamin, Ernst Bloch, Bertolt Brecht, Georg Lukács)

Walter Benjamin

- The Cambridge Companion to Walter Benjamin , 2004.

Terry Eagleton

Eagleton, Terry. Criticism and Ideology: a Study in Marxist Literary Theory . NLB, 1976.

Eagleton, Terry. Marxism and Literary Criticism . University of California Press, 1976.

Antonio Gramsci

Forgacs, David, et al. Antonio Gramsci: Selections From Cultural Writings . Lawrence & Wishart, 2012.

Gramsci, Antonio, et al. Selections from the Prison Notebooks of Antonio Gramsci . Edited by Quintin Hoare and Geoffrey Nowell-Smith, Lawrence & Wishart, 2003. Further Selections .

Fredric Jameson

Jameson, Fredric. The Political Unconscious: Narrative as a Socially Symbolic Act . Cornell University Press, 1981.

Jameson, Fredric. Marxism and Form: Twentieth-Century Dialectical Theories of Literature . Princeton University Press, 1972.

György Lukács

Lukács, György. History and Class Consciousness: Studies in Marxist Dialectics . Translated by Rodney Livingstone, MIT Press, 1971.

German edition, Geschichte und klassenbewusstsein: studien über marxistische dialektik

Pierre Macherey

Althusser, Louis, et al. Reading Capital: the Complete Edition . Verso, the imprint of New Left Books, 2015.

French edition, Lire le Capital

French edition, Pour une théorie de la production littéraire

Introductions & Anthologies

Also see other recent books discussing or using Marxist criticism in literature and scholar-recommended sources on Marxism via Oxford Bibliographies.

Buchanan, Ian. "Marxist Criticism." In A Dictionary of Critical Theory . Oxford University Press, 2010. Foley, Barbara. Marxist Literary Criticism Today , Pluto Press, 2019, p. 122.

- << Previous: Indigenous Literary Studies

- Next: Narratology >>

- Last Updated: May 16, 2024 1:27 PM

- URL: https://guides.lib.uw.edu/research/literaryresearch

Table of Contents

Ai, ethics & human agency, collaboration, information literacy, writing process, marxist criticism.

- © 2023 by Angela Eward-Mangione - Hillsborough Community College

Marxist Criticism refers to a method you'll encounter in literary and cultural analysis. It breaks down texts and societal structures using foundational concepts like class, alienation, base, and superstructure. By understanding this, you'll gain insights into how power dynamics and socio-economic factors influence narratives and cultural perspectives

What is Marxist Criticism?

Marxist Criticism refers to both

- an interpretive framework

- a genre of discourse .

Marxist Criticism as both a theoretical approach and a conversational genre within academic discourse . Critics using this framework analyze literature and other cultural forms through the lens of Marxist theory, which includes an exploration of how economic and social structures influence ideology and culture. For example, a Marxist reading of a novel might explore how the narrative reinforces or challenges the existing social hierarchy and economic inequalities.

Marxist Criticism prioritizes four foundational Marxist concepts:

- class struggle

- the alienation of the individual under capitalism

- the relationship between a society’s economic base and

- its cultural superstructure.

Related Concepts

Dialectic ; Hermeneutics ; Literary Criticism ; Semiotics ; Textual Research Methods

Why Does Marxist Criticism Matter?

Marxist criticism thus emphasizes class, socioeconomic status, power relations among various segments of society, and the representation of those segments. Marxist literary criticism is valuable because it enables readers to see the role that class plays in the plot of a text.

What Are the Four Primary Perspectives of Marxism?

Did karl marx create marxist criticism.

Karl Marx himself did not create Marxist criticism as a literary or cultural methodology . He was a philosopher, economist, and sociologist, and his works laid the foundation for Marxist theory in the context of social and economic analysis. The key concepts that Marx developed—such as class struggle, the theory of surplus value, and historical materialism—are central to understanding the mechanisms of capitalism and class relations.

Marxist criticism as a distinct approach to literature and culture developed later, as thinkers in the 20th century began to apply Marx’s ideas to the arts and humanities. It is a product of various scholars and theorists who found Marx’s social theories to be useful tools for analyzing and critiquing literature and culture. These include figures such as György Lukács, Walter Benjamin, Antonio Gramsci, and later the Frankfurt School, among others, who expanded Marxist theory into the realms of ideology, consciousness, and cultural production.

So, while Marx provided the ideological framework, it was later theorists who adapted his ideas into what is now known as Marxist criticism.

Who Are the Key Figures in Marxist Theory?

Bressler notes that “Marxist theory has its roots in the nineteenth-century writings of Karl Heinrich Marx, though his ideas did not fully develop until the twentieth century” (183).

Key figures in Marxist theory include Bertolt Brecht, Georg Lukács, and Louis Althusser. Although these figures have shaped the concepts and path of Marxist theory, Marxist literary criticism did not specifically develop from Marxism itself. One who approaches a literary text from a Marxist perspective may not necessarily support Marxist ideology.

For example, a Marxist approach to Langston Hughes’s poem “ Advertisement for the Waldorf-Astoria ” might examine how the socioeconomic status of the speaker and other citizens of New York City affect the speaker’s perspective. The Waldorf Astoria opened during the midst of the Great Depression. Thus, the poem’s speaker uses sarcasm to declare, “Fine living . . . a la carte? / Come to the Waldorf-Astoria! / LISTEN HUNGRY ONES! / Look! See what Vanity Fair says about the / new Waldorf-Astoria” (lines 1-5). The speaker further expresses how class contributes to the conflict described in the poem by contrasting the targeted audience of the hotel with the citizens of its surrounding area: “So when you’ve no place else to go, homeless and hungry / ones, choose the Waldorf as a background for your rags” (lines 15-16). Hughes’s poem invites readers to consider how class restricts particular segments of society.

What are the Foundational Questions of Marxist Criticism?

- What classes, or socioeconomic statuses, are represented in the text?

- Are all the segments of society accounted for, or does the text exclude a particular class?

- Does class restrict or empower the characters in the text?

- How does the text depict a struggle between classes, or how does class contribute to the conflict of the text?

- How does the text depict the relationship between the individual and the state? Does the state view individuals as a means of production, or as ends in themselves?

Example of Marxist Criticism

- The Working Class Beats: a Marxist analysis of Beat Writing and (studylib.net)

Discussion Questions and Activities: Marxist Criticism

- Define class, alienation, base, and superstructure in your own words.

- Explain why a base determines its superstructure.

- Choose the lines or stanzas that you think most markedly represent a struggle between classes in Langston Hughes’s “ Advertisement for the Waldorf-Astoria .” Hughes’s poem also addresses racial issues; consider referring to the relationship between race and class in your written response.

- Contrast the lines that appear in quotation marks and parentheses in Hughes’s poem. How do these lines differ? Does it seem like the lines in parentheses respond to the lines in quotation marks, the latter of which represent excerpts from an advertisement for the Waldorf-Astoria published in Vanity Fair? How does this contrast illustrate a struggle between classes?

- What is Hughes’s purpose for writing “ Advertisement for the Waldorf-Astoria ?” Defend your interpretation with evidence from the poem.

Brevity - Say More with Less

Clarity (in Speech and Writing)

Coherence - How to Achieve Coherence in Writing

Flow - How to Create Flow in Writing

Inclusivity - Inclusive Language

The Elements of Style - The DNA of Powerful Writing

Suggested Edits

- Please select the purpose of your message. * - Corrections, Typos, or Edits Technical Support/Problems using the site Advertising with Writing Commons Copyright Issues I am contacting you about something else

- Your full name

- Your email address *

- Page URL needing edits *

- Comments This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

Other Topics:

Citation - Definition - Introduction to Citation in Academic & Professional Writing

- Joseph M. Moxley

Explore the different ways to cite sources in academic and professional writing, including in-text (Parenthetical), numerical, and note citations.

Collaboration - What is the Role of Collaboration in Academic & Professional Writing?

Collaboration refers to the act of working with others or AI to solve problems, coauthor texts, and develop products and services. Collaboration is a highly prized workplace competency in academic...

Genre may reference a type of writing, art, or musical composition; socially-agreed upon expectations about how writers and speakers should respond to particular rhetorical situations; the cultural values; the epistemological assumptions...

Grammar refers to the rules that inform how people and discourse communities use language (e.g., written or spoken English, body language, or visual language) to communicate. Learn about the rhetorical...

Information Literacy - Discerning Quality Information from Noise

Information Literacy refers to the competencies associated with locating, evaluating, using, and archiving information. In order to thrive, much less survive in a global information economy — an economy where information functions as a...

Mindset refers to a person or community’s way of feeling, thinking, and acting about a topic. The mindsets you hold, consciously or subconsciously, shape how you feel, think, and act–and...

Rhetoric: Exploring Its Definition and Impact on Modern Communication

Learn about rhetoric and rhetorical practices (e.g., rhetorical analysis, rhetorical reasoning, rhetorical situation, and rhetorical stance) so that you can strategically manage how you compose and subsequently produce a text...

Style, most simply, refers to how you say something as opposed to what you say. The style of your writing matters because audiences are unlikely to read your work or...

The Writing Process - Research on Composing

The writing process refers to everything you do in order to complete a writing project. Over the last six decades, researchers have studied and theorized about how writers go about...

Writing Studies

Writing studies refers to an interdisciplinary community of scholars and researchers who study writing. Writing studies also refers to an academic, interdisciplinary discipline – a subject of study. Students in...

Featured Articles

Academic Writing – How to Write for the Academic Community

Professional Writing – How to Write for the Professional World

Credibility & Authority – How to Be Credible & Authoritative in Speech & Writing

A Beginner’s guide to Fundamental Principles of Marxism

Marxist thought primarily critiques capitalism. It was founded by the renowned German philosopher, theorist and revolutionist Karl Hein Marx (1818-1883) and Fredrich Engels. Besides being a globally adapted and practised social and political theory, Marxism has influenced prominent modern literary theories like historicism, feminism, deconstruction, postcolonialism and cultural studies. This article discusses the fundamental principles of Marxism as established by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels.

What are the Fundamental Principles of Marx’s Thought?

The foremost step towards understanding marxist literary theory is to be familiar with the basic principles of Marxism.

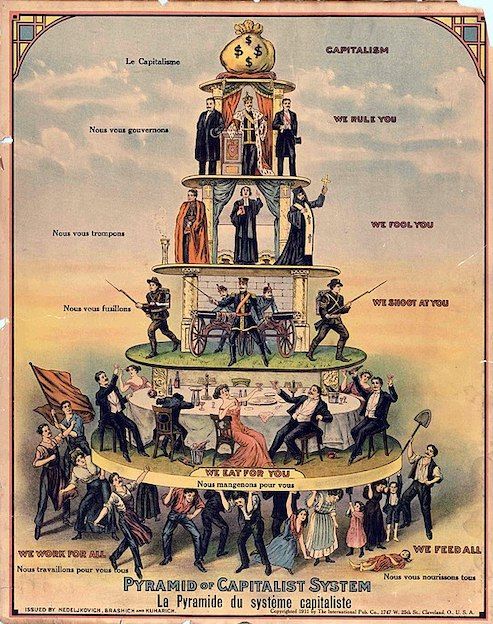

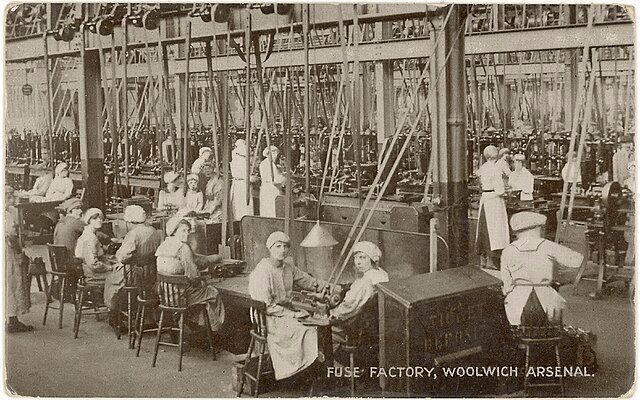

I. Critique of Capitalism

A capitalistic society is characterised by features such as private ownership of means of production, minimal governmental intervention, and profit. For example, the United States is a typical capitalist society. Most of the means of production in the U.S. are privately owned by individual entrepreneurs or private corporations. The economy of the nation is primarily driven by profit and has minimal governmental intervention. One of the most significant and foremost principles of marxism is the critique of capitalism.

Karl Marx objected to Capitalism on the basis of four factors:

- Capitalism concentrated the means of production, property, and wealth in the hands of a particular class, the bourgeoisie.

- Since wealth belongs exclusively to the bourgeoisie, the proletariat or the working class is constantly exploited and oppressed. Capitalism generates a working class that exists only as long as they are able to find work. The workers are employable as long as they generate profit for the bourgeoisie and increase their capital. Thus, the working class is reduced to a commodity serving for the benefits of the capitalist class.

- Capitalism possesses an imperialistic nature. In order to perpetuate their wealth, the bourgeoisie exploits globally and “creates a world after its own image”.

- Capitalism reduces all human relationships to a cash nexus that are driven by self-interest and monetary calculations. Even a family is reduced to an economic commodity. A bourgeois man in a capitalistic society reduces the wife to a source of production. Within a capitalistic society, it is the capital that has a character or an individuality. All individuals are completely chained to it and are robbed off their identities.

II. Dialectic of History is motivated by material forces- Impact of Hegel on Marx

Vladimir Lenin has accurately pointed out that “I t is impossible completely to understand Marx’s Capital, and specially its first chapter, without having thoroughly studied and understood the whole of Hegel’s Logic. ” Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel or G.W.F Hegel (1770-1831) was one of the most influential German philosophers who significantly shaped Marx’s philosophy. Hegel regarded dialectics as the hallmark of his philosophy and used it in his Encyclopedia of Philosophical Sciences (1817) and Elements of the Philosophy of Right (1820)

Understanding Hegel’s Dialectics

Hegel’s concept of dialectics is primarily a synthesis of opposites. It is popularly known as the triad of thesis, antithesis and synthesis . It is a process where tensions are eventually resolved throughout history. In the first stage, a thesis is proposed, or an idea is defined. This initial thesis is a simplistic and individualistic definition of an idea. During the second stage, there is an antithesis that opposes the definition of the proposed initial thesis, and in the process provides a wider scope to the initial idea. The final stage or the synthesis is the reconciliation between the thesis and the antithesis. It acts as a union between the particular and the universal. Hegel employed dialectical methodology while exploring the concept of freedom in the Philosophy of Right. We can utilise this to understand the dialectical methodology.

- Thesis: The concept of Freedom: This would include the simple and individual definition of freedom. Freedom means that one is free to do whatever they want to without considering any external factors.

- Antithesis : The antithesis criticises the definition of freedom. It points out that if everyone began to do as they pleased and practised absolute freedom without any social consciousness, it would inevitably result in chaos. Thus, it attempts to situate the concept of freedom against a wider social context.

- Synthesis: The final stage unites the thesis and the antithesis while providing a wider scope to the meaning of freedom. The abstract and absolute idea of freedom eventually gets synthesised to ‘freedom within a civil society’. Thus, synthesis not only reconciles thesis and antithesis, but also generates a new definition of freedom where individuals can do as they please as long as they are in harmony with societal peace. There exists a balance between absolute freedom and restriction.

Even though the triad of Thesis-Antithesis-Synthesis is famously attributed to Hegel, he never employed these terms for his dialectical methodology. The triad of thesis-antithesis-synthesis was coined by the German philosopher Johann Gottlieb Fitche . Nevertheless, it provides an outline to his philosophy of dialectics. Hegel extensively explains his dialectical method in Encyclopedia Logic , the first part of his Encyclopedia of Philosophical Sciences . According to him, a logic has three moments: