Principedia

History Department

Insights into the historical discipline.

Strategies for Approaching Readings and Precept in History Courses

Vocabulary in the discipline: Primary sources are documents that date from the time being discussed. Secondary sources are documents that discuss or analyze primary sources.

For example: If your History class is studying ancient Greece, a primary source would be a play Sappho wrote, while a secondary source would be a recent article written about Sappho’s literary work.

However, if you are writing about the arguments made by a group of scholars who have studied Sappho, the above “secondary source” would become a primary source for this particular paper topic, while a secondary source would be an article that analyzes prior scholarship on Sappho.

Readings for Discussion: In high school, many students were given textbooks, and all assessments and class material were derived from the textbook. Some AP courses may have done exercises using primary source analysis. At Princeton, many history courses have a variety of assigned texts. Often, there might be a textbook that is a more dry and detailed version of what you may have seen in your high school history classes, but it is recommended reading, not required. The assignments will appear in the syllabus to give background for the lectures that week. Usually, history classes will assign a mix of primary source readings (documents from the time period you are discussing in class) and secondary source readings (scholarly essays written by academics addressing change/continuity over time of one of the class themes). While in high school you may have been asked to give a summary of events, in precept you are expected not only to understand the chronology of historical events, but have arguments derived from the reading materials as to why the events unfolded in the way that they did. There is no one right answer. Although it might feel strange to make assertions as an independent thinker instead of regurgitating dates, if you ask yourself the following questions while reading, you will assemble various insights and theories into why and how historical events happened.

Questions to Ask Oneself When Reading Discussion Material for Precept/Seminar:

“Although interdisciplinary, what distinguishes historical research and writing is that historians seek to understand previous eras and other societies on their own terms rather than from the perspective of our own time.” (PU History Dpt.)

Your answers to the following questions will help you contribute to precept discussion. You may not be able to fully answer every (or any) question, but thinking about each question as you read, and writing down the answer in the margins, your notebook, or computer will help you to use the same document to address a variety of topics, each revealing something different in the text. Who wrote it? Consider: What are the author’s race, gender, sexuality, class, political positions in their society? Would this person have been expected to write a piece like this? (ie who would have been the typical author of such a piece? For ex: Is a wealthy person writing about the ability of poor people to make a living? Is the author of a political speech a politician, or an actor? How does the person’s social/political/economic relation to their topic affect the way you analyze the piece?)

What are they saying? Consider: Who/What are they referring to? What do they think about it? How are they supporting their arguments? What are they ignoring?

When did they write it? Consider: What else was going on at that time globally and locally?

Where did they write it? Consider: Where was it published?

Why did they write it? Consider: What political, social, or economic forces may have affected their decision to write it? Who do you think was their intended audience? Who, in that time period and place, would have disagreed with what they argue?

How do they write it? Consider: What is their tone? How is their argument structured?

Do you agree with the author? Why or why not? How does this document help you understand the complexities of life as a person with [identities] in [geographic region] in [time period]?

What surprised you about this text? What confuses you? What seems familiar to you? → then ask, why did you have those reactions at those moments? How did your assumptions or prior knowledge affect your reading of the text?

Strategies for Approaching Assessments in History Courses

Myth: History classes ask you to memorize dates and battles for success in the course. Reality: “Historians seek to understand changes and continuities in the past and comprehend how the present came to be.” (PU History Dpt.) Demands of Princeton History courses reflect this aim.

Compared to high school: Those who have taken the AP tests in history might find some of the assessments and assignments for Princeton history classes familiar. Although few, if any history courses, assess students using multiple choice questions, many will have in-class essays for the midterm or final exams. The essays will have a comparative element, or a change over time component to them, and thus echo the style of essays high school students may have written for the AP tests. Often times, history professors will provide a list of sample in-class essay questions, and one or two will appear on the final, with students (also often) having the choice to choose between the questions.

A common prompt on in-class essays will ask students to discuss political, economic, and/or social change over time with a particular concept from the course. A way to study for such a question – which does not demand students to memorize many specific dates but instead to think broadly about movements and shifts in belief or practice – is to go through lecture notes with three different highlighters to mark points that help to trace the evolution of political, social, or economic events. Then, you can return to your notes to trace the changes in one of these categories.

Comprehensive exams take place during the exam period of the spring semester of senior year for history concentrators. They are a minor part of being a history concentrator, and are not supposed to require outside research. Instead, their purpose is to show the department what students have learned from their History coursework. They consist of two five-page papers that can be written using class notes. Students pick two out of about eight questions to answer for the exam. Although some questions can be answered using a variety of course materials, others are much more specific. Students should keep lecture notes from their history classes in case questions on the exams can be answered with them.

Strategies for Approaching Learning in History Lectures

Some professors design their lectures such that the historical content is delivered chronologically over the course of the semester. Other times, professors will deliver topics based on theme. Clues as to how the professor will deliver the lectures are in the course title: while some include a date range, like “Europe from Antiquity to 1700” (suggesting lectures will proceed chronologically) while others, like “Religion, Gender, and Sexuality in Colonial Latin America” are more likely to be structured thematically.

Strategies for Writing Papers in History Courses

Thesis statements: Try not to universalize, because there are always paradoxes! Think of popular opinion as a spectrum, and not a binary.

For example: A community is never all pro-war or all pro-peace. People fighting for revolution fight for different reasons, even if they technically all want a revolution, etc.

While we like to put people or ideas in neat categories, in reality we can’t make a definitive statement that will always be true. A more typical historical observation might be, “Many people believed in [idea A] in [time period and place], but those who didn’t instead argued for [idea B], [idea C] or [idea D].” One might go on to explain why each group believed in their specific idea.

Magic thesis statement: pointing out a pattern or trend while recognizing the contrasts or dissenting elements within that same data/document set.

Academics often write papers that disrupt the common conception of a people, event, or place at a specific time period using primary sources that are newly discovered or ones that the historian believes have been misinterpreted.

Department Resources

The History department has a variety of written resources on its website under the tab “Resources.” These include calendar dates for juniors and seniors to help structure independent work, a guide to independent work for the department, and junior paper and senior thesis guidelines.

Independent work guidelines

Both independent work calendars provide a bare bones outline for the writing process – each calendar gives a deadline for a partial first draft, and the first full draft, followed by the final due date. If students would like more internal deadlines, they have to decide these with their advisors. Sometimes advisors will impose internal deadlines on their advisees. Each junior seminar instructor has a different approach to their course. Department guide: what is it answering/not answering? Student’s point of view? The History Department Independent Work Guide is an 18-page, single-spaced, comprehensive overview of demands and strategies for completing independent work for the department. In addition to walking students through questions and strategies (even with motivational support!) for approaching questions, research, writing, and revision, it provides resources at each step where students can get outside help. For example, the online guide includes hyperlinks where students can make appointments at the Writing Center, or with the History librarian at Firestone. The sole aspect of independent work that the guide does not address is the often-overlooked importance of finding an appropriate advisor for someone and their project.

Students have one advisor for independent work in their junior and senior years. In their junior fall, the instructor of their junior seminar is their advisor. In the spring, students must research and decide on their own who they would like to be their advisor. The history department website says that students list three preferences and submit them to the department, but this is not the practice in reality. For many students, they must meet with potential advisors and ask them individually. The history department does not give guidelines for how juniors might approach choosing a spring JP or senior thesis advisor. Ideally, one’s advisor is an expert in the field that is of interest to the student, however there are other factors that go into a positive advisor-advisee relationship. Geographic region and time period are certainly relevant to one’s choice, but they are only part of influential factors for the relationship. Another important aspect to consider is field (consider as a lens through which a historian focuses on a part of history), for example: political, gender, economic, intellectual, environmental, or post-colonial. Under the heading “Fields” on the department website, you can explore the biographies and research interests of the history department professors.

A less-discussed aspect of advising includes mentorship. Students might look for the opportunity to build personal connections to faculty members, and develop academic relationships in which they feel comfortable asserting themselves and asking questions. In this case, in addition to field, geographic region, and time period, these students should consider which professors with whom they or their friends have felt comfortable when taking academic risks. If a strong mentor-mentee relationship is of high importance to the student, they might consider asking a professor who does not share their research interests to be their advisor if they are a professor the student trusts. With the accessibility of other professors, the rising availability of sources online, and the expertise of the History librarians, students can find sources through other avenues than their professor’s research experience.

Princeton University Undergraduate Senior Theses, 1924-2023

Members of the princeton community wishing to view a senior thesis from 2014 and later while away from campus should follow the instructions outlined on the oit website for connecting to campus resources remotely..

- Communities Collections

Collections in this community

Aeronautical engineering, 1945-1975, african american studies, 2020-2023, anthropology, 1961-2023, architecture school, 1968-2023, art and archaeology, 1926-2023, astrophysical sciences, 1990-2023, biochemical sciences, 1968-1985, biology, 1925-1990, chemical and biological engineering, 1931-2023, chemistry, 1926-2023, civil and environmental engineering, 2000-2023, civil engineering and operations research, 1931-2000, classics, 1934-2023, comparative literature, 1975-2023, computer science, 1987-2023, creative writing program, 1995-2023, east asian studies, 1951-2023, east asian studies program, 2017-2022, ecology and evolutionary biology, 1992-2023, economics, 1927-2023, electrical and computer engineering, 1932-2023, engineering and applied science, 1933-1987, english, 1925-2023, french and italian, 2002-2023, geosciences, 1929-2023, german, 1958-2023, global health and health policy program, 2017-2023, history, 1926-2023, independent concentration, 1972-2023, mathematics, 1934-2023, mechanical and aerospace engineering, 1924-2023, medieval studies, 1976-1981, modern languages, 1926-1958, molecular biology, 1954-2023, music, 1948-2023, near eastern studies, 1969-2023, neuroscience, 2017-2023, operations research and financial engineering, 2000-2023, oriental studies, 1959-1969, philosophy, 1924-2023, physics, 1936-2023, politics, 1927-2023, princeton school of public and international affairs, 1929-2023, program in dance, program in visual arts, psychology, 1930-2023, religion, 1946-2023, robotics and intelligent systems program, romance languages and literatures, 1928-2002, slavic languages and literature, 1962-2023, sociology, 1954-2023, south asian studies program, spanish and portuguese, 2002-2023, special program in humanities, 1936-1972, statistics, 1967-1985, theater program, 1940-2023.

- Skip to search box

- Skip to main content

Princeton University Library

History senior thesis survival guide.

- Finding primary sources at Princeton

- Finding primary sources elsewhere

- Primary source guides

- Practical advice

For visiting libraries and archives

- Finding bibliographies

- Finding book reviews

- Historiography for beginners

- Footnotes made easy This link opens in a new window

Now, plan your trip. Check the web pages of the library or archive you plan to visit for information about:

- Access (Is the collection open for research? Do you need a letter of introduction? Will you need to register before using their collections?)

- Hours (Are they open on the weekend? Closed for renovations?)

- Copies and scans (Is self-service copying/scanning possible, or must you have copies made by their staff? What are the fees? Can you use a digital camera?

- Availability of materials (Are materials paged from remote storage? How long will you have to wait? Are some materials temporarily inaccessible?)

- Arrangement of materials (Are there indexes, inventories, or finding aids for manuscript collections?)

- Practicalities (Directions, parking?)

Also, you may want to consult Archives Made Easy , a web site that provides tips for researchers visiting many archives in the U.S. and elsewhere.

- << Previous: Primary source guides

- Next: Finding out what other historians think >>

- Last Updated: Dec 19, 2023 1:59 PM

- URL: https://libguides.princeton.edu/history/seniorthesis

Senior Thesis

Undergraduate Program Office 609-258-4861 [email protected]

The senior thesis is a scholarly paper focused on the policy issue in public or international affairs that is of greatest interest to the student. It is based on extended research and is the major project of the senior year.

Each student must complete a senior thesis that addresses a specific policy question and either draws out policy implications or offers policy recommendations (or both).

The Princeton School of Public and International Affairs awards several scholarships each year for travel and living expenses related to senior thesis research.

The University’s requirement for a senior comprehensive examination is satisfied in the School by an oral defense of the thesis. Students prepare a response to written evaluations from their thesis advisor and a second reader, followed by a question-and-answer period.

Senior Thesis Advising: The Senior Thesis Advisor Selection Guide - Students should use this to identify thesis advisors who match their interests and possible thesis topics. This tool is organized by faculty issue and regional expertise.

Senior Thesis Deadlines

Thesis Proposal Form Due Thursday, September 21, 2023

You must submit your thesis proposal form, signed by your advisor, via email to [email protected] by 12pm (noon).

First Semester Progress Report Due Monday, December 4, 2023

You must submit your first-semester progress report to your advisor and to [email protected] by 12pm (noon).

Complete Draft Friday, March 1, 2024

First drafts of all of your chapters are due to your thesis advisor by 12pm (or earlier per any agreement with your thesis advisor).

Thesis Due Monday, April 8, 2024

An electronic copy must be submitted to the Undergraduate Program Office ( [email protected] ) by 12:00 p.m. (noon). Upload a PDF of your thesis, for archiving at MUDD Library, via the centralized University Senior Thesis Submission Site . See page 9 of the Senior Thesis Guide for additional thesis deadline information.

Oral Examinations May 8th – May 9th, 2024

The University’s requirement for a senior comprehensive examination is satisfied by an oral examination based on your thesis.

Guide to Senior Independent Work

Please review this document completely and thoroughly for more information on your senior thesis.

Getting Started in Data Analysis: Topic Selection and Crafting of a Research Question - Independent research projects start with the selection of a topic and the crafting of a feasible research question. This video maps the initial steps to help...

All independent work that involves research with human subjects must first be reviewed and approved by the University’s Institutional Review Board . The mission of the Institutional Review Board (IRB) is to protect the rights, privacy, and welfare of human participants in research conducted by faculty, staff, and students.

If you plan to conduct research involving human subjects for your Senior Thesis, you must first consult with IRB prior to beginning your interviews to determine whether an IRB application, review, and approval are required for our project. The department recommends Seniors should complete the process in October or November, if possible.

Email a synopsis of the proposed activity (3 paragraphs) to the IRB: [email protected] . Include the draft measurements (survey, questionnaire, interview guide), if applicable.

Please visit the eRIA-IRB training site for more information.

Should you have questions as you prepare the materials, please consult IRB at [email protected] or your advisor for assistance.

SPIA Thesis Funding - Students can apply for funding by accessing the online application in the Student Activities Funding Engine (SAFE)

In addition to your consultations with your thesis advisor, we strongly recommend that you meet regularly with the Princeton School of Public and International Affairs Writing Advisor, for assistance in conceptualizing and organizing your thesis, developing your arguments, and reviewing your writing. They can best help you if you meet with him early in (as well as throughout) the process. Writing advisors can be reached at [email protected] .

Library Resource Guide - A guide for seniors who are conducting thesis research

An excellent senior thesis can be 75 pages or less. No thesis should be longer than 115 pages. Any page after 115 may or may not be read by the second reader. A thesis longer than 115 pages will not be considered for a SPIA thesis prize.

The 115-page limit includes:

- the abstract

- the table of contents

- ancillary material such as tables and charts

- all footnotes

The page limit does not include:

- the title page

- the dedication

- the honor code statement

- the bibliography

Include the Honor Pledge, and your signature on the last page.

Use a 1-inch margin on the left, right, top and bottom.

Double-space all text (except long quotations, footnotes and bibliography).

Number your pages.

Make sure the thesis is single sided.

Use a 12‑point size type and a readable font. Avoid the use of multiple fonts and type sizes(other than footnotes, which may be in a smaller font).

Indent paragraphs and avoid paragraphs longer than a page.

Within chapters, use only two levels of headings, either in bold or underlined and placed at the left margin or centered. The primary heading is all caps, the secondary is caps and lower case:

Pages should be organized as follows:

Title page (see format on next page)

Second page: Dedications (optional)

Third page: Acknowledgements

Fourth page: Table of Contents

Fifth page: Abstract

Last page: The last page must contain the following: This thesis represents my own work in accordance with University Regulations. Your signature

Seeley G. Mudd Manuscript Library Senior Thesis Catalog - is a catalog of theses written by seniors at Princeton University from 1926 to present

The Princeton School of Public and International Affairs will grant extensions only for severe personal illness, accident, or family emergency. The request for an extension must be made in writing. Extensions to a date no later than the University’s deadline for submitting senior independent work may be granted by the Associate Dean of the Program, Paul Lipton, [email protected] . After this deadline, extensions may be granted only by the Dean of your residential college.

Under no circumstances will extensions be granted for any reason connected with computer problems . Students should therefore save, backup, print their work in a manner designed to prevent last-minute crises.

One-third of the thesis final grade will be deducted for each four days (or fraction of four days) that the thesis is late. Please see the Guide to Independent Work for more information.

Submit one electronic copy in PDF format to the SPIA undergraduate office, [email protected] , by the Deadline. Must also upload a PDF of your thesis, for archiving at MUDD library, via a centralized University Senior Thesis Submission Site .

The thesis is graded by the thesis advisor, who is the first reader of the senior thesis, and by a second reader assigned by the Undergraduate Program Office. The grade is calculated as follows:

- If the readers' grades are identical, that is the final grade.

- If the readers' grades differ by one full grade (e.g., A to B) or less, the average grade is the final grade.

- If the readers’ grades differ by more than one full letter grade, the two readers consult to determine the final grade; if they are unable to agree, the Faculty Chair of the Undergraduate Program determines the grade.

The Undergraduate Program office will determine any penalty for lateness, which will be included in the grade reported to the Registrar .

A thesis that receives a grade of A or higher and a statement of support from both readers (and is within the page limit) may be considered for a Princeton School of Public and International Affairs thesis prize. Prizes are awarded by a specially appointed School faculty committee that weighs the relative merits of all theses under consideration. Prizes are presented at the Class Day ceremony.

SPIA Prize Theses - Sample Prize theses from 2017 to present

Senior Thesis Project Planning Map and Timeline

Monthly schedule, july, august, & september.

Goal: Identify topic & advisor

Deadline: September 18 - Name of Senior Thesis Advisor Due

- Drawing on past coursework, independent work, or maybe just curiosity, decide on a topic that interests you personally. What problem puzzles you? What aspect of politics would you like to understand in depth?

- The secret at this stage is to identify an interesting area to do research in without narrowing your mind so much that you won’t benefit from other people’s advice—most importantly, the Politics faculty.

- Begin exploratory reading on your topic. Note specific questions that you might want to answer. It helps to come up with several specific questions in case one turns out to be impractical.

- A good thesis topic is one that excites and motivates you; a good research question is one that can be answered by an advanced undergraduate in six months!

- Use the list of available advisors in Politics to identify available faculty members in your topic area.

- Write potential advisors with a short description of your topic idea. In your email, introduce yourself as a Politics senior and request a brief meeting to discuss the possibility of thesis advising. It usually makes sense to ask several faculty members at the same time.

- Substance matters in finding the right advisor, but so does style. Find someone with matching expectations about frequency of meeting schedule, amount of guidance, and forms of communication. Be prepared to bring up these considerations in your meeting.

- In almost all cases, Politics Department faculty members advise Politics seniors. The reason is simple: You’re writing a Politics thesis; you’re getting a degree in Politics; your thesis will be evaluated by a second reader who is a Politics professor.

- If there is a compelling case that an advisor from another academic unit is more appropriate, you may request written permission from Professor Matias Iaryczower choose an advisor not in Politics. But you must first do your homework. You have to show that no one in Politics can cover your topic, that your topic is actually a Politics topic, and that your potential advisor elsewhere would in fact agree to advise you.

- We encourage you to apply for funding because conducting your own research with your own money is fun. But you need a plan, and you must work with your advisor in developing the plan.Find out whether you have to get approval for your interviews or survey from the University’s Institutional Review Board (IRB) for Human Subjects at the Office of Research and Project Administration. NOTE: ALL students who apply for Politics thesis funding are REQUIRED to ask the IRB to review their proposed project PRIOR to submitting the funding application in SAFE. You will be asked to upload proof of the email that you sent the IRB ( [email protected] )as part of submitting your application. This important step must be completed by the October 25 application deadline to demonstrate that you have started the process.

- If you collect data and your data collection falls under the IRB’s jurisdiction, you cannot start without formal IRB approval, and the IRB process may take one to two months.

- Senior thesis research funding opportunities will be posted in the Student Activity Funding Engine (SAFE) . NOTE: The Politics thesis funding application will be posted in SAFE by the start of Fall classes. You should apply to the Office of Undergraduate Research and other University funders as applicable, but make sure you check their deadlines in SAFE as they will differ from that of the Politics Department.

Goal: Work out your specific topic with your advisor; make a detailed plan

Deadline: October 25 - Politics thesis research funding application is due online in SAFE by 11:59 PM

[NOTE: See above for more information about funding opportunities.]

- Write a tentative, working thesis statement that spells out your research question, why it matters, and how you intend to answer it.

- Create a working list of important secondary sources to read, and locate them. Consult the bibliographies of the most useful secondary sources (check your syllabi). Although searching article databases can yield useful sources that you might otherwise miss, you should not attempt a random or exhaustive survey of the literature. Your goal is to identify 5-10 most important sources, not to read them cover-to-cover (yet) or to come up with dozens of vaguely relevant readings.

- Turn in a short thesis proposal and your bibliography to your advisor for feedback.

- Schedule time to discuss your research plan with Politics Librarian Jeremy Darrington , the Survey Research Center or the relevant entities to assist with primary evidence collection.

Goal: Thesis proposal

- lays out the problem

- justifies the topic as a significant one for understanding politics

- clearly states the argument you will make

- tells the reader how your argument builds on other scholarship

- lays out the specific research plan for gathering evidence

- concludes with the theoretical implications of the argument

- Consider turning in an annotated bibliography to your advisor for feedback. Explain how the readings will inform your own argument. Will a given book help you elaborate your argument? Will it help you to locate primary sources? Will it offer an alternative argument to your own, one you will refute with evidence?

- Consider your advisor’s feedback. Work with him or her to get ready for collection of original data, interviews, archival work, or whatever evidence you will use in your research.

Goal: A draft of one chapter

The best way to make progress and get help from your advisor is to share your work. Have at least one chapter drafted and submit it to your advisor for feedback before Winter Break.

WINTER BREAK

Goal: Examine your evidence, start answering your research question

You should use this time for evidence gathering and writing. Write a rough draft of one evidence chapter.

Goal: A draft of your evidence chapter

Turn in a draft of one evidence chapter immediately after break. Also provide a short outline of the thesis, chapter by chapter (one paragraph each). Write a rough draft of the remaining evidence chapters.

Make a realistic plan for the next two months; time management helps you complete your thesis.

Goal: A full draft of your thesis

February is writing time! Complete the main analyses, revise earlier chapters in light of new developments and advisor suggestions.

Faculty need time management, too. That’s why we have a draft deadline. If you turn in your draft by the deadline, your advisor will have sufficient time to read it -and more importantly, you will have sufficient time to implement changes. Drafts turned in past the deadline may not receive full comments and feedback.

MARCH & APRIL

Goal: Finish the job

Deadlines: March 4 - Turn in a full draft to your advisor. April 3 - Submit your senior thesis to the Politics Department

Revise thesis based on advisor feedback.

TIP: Students are encouraged to view existing Politics senior theses as samples. You can either visit the Seeley G. Mudd Manuscript Library, where all senior theses submitted to Princeton University are housed, or you can log into Thesis Central to conduct a search. If you would like to examine theses that have won prizes, go to Honors and Awards section of our site and then navigate to “Recent Recipients, Senior Thesis Prizes”. Here you can view exemplary senior theses by primary fields.

Outline of Senior Thesis

Every thesis is different, but here is a general outline of how you may choose to organize your thesis.

Chapter I: Introduction

The introduction should make clear the question your thesis addresses. It should explain why addressing this question is important in the field of politics. Also, explain the alternative arguments that exist and the gaps in the existing literature that your thesis addresses.

Chapter II: Theory (and history)

This chapter should develop your argument and ground it in secondary sources. In detail, explain your idea, and justify its validity with as many good reasons as you can. For many theses, this requires a historical component that sets the argument in the context of a sequence of events in the real world of politics. Your core chapters (see below) may also be historical, but by contrast they will contain lots of detailed evidence. This chapter is the place to define concepts and explain how your idea relates to and draws on the writings of other people. A short thesis may fold this chapter into the introductory chapter.

Chapters III, IV (and V): Evidence (The Core)

Here you methodically lay out the evidence that supports the argument you have developed in the early chapters. Be sure to explain where the evidence came from and why it is valid. If you executed a study of your own (interviews, experiment, survey) then you may need a separate chapter that contains the research design and provides details on how you collected the data. If you rely on data collected by someone else, give a brief description of how it was collected, so that readers can judge its validity. Be sure you know the potential sources of error or bias in the data, so that you can explain why it is valid. Always note the sample size and the process of sample selection, and detail the characteristics of the sample. If you are using a historical case (e.g., a city, or an organization, or a leader), then justify the reason for selecting that case and not others. It is often useful to include tables or figures. If you do so, explain in the text what the reader is to learn from each table or figure. Each table should be self-explanatory, but the text should highlight what is important about it.

Chapter V(or VI): Conclusion

Remind readers of your argument and summarize the evidence you presented. Show how you have established the argument with the evidence. Draw implications for the general topic from the details of what you have found and argued. Remind readers again of the reasons your question is important for understanding politics. Knowing what we now know about your topic, what can we conclude about politics?

IMPORTANT NOTE: Your thesis must be your own original work. Be sure to cite sources properly. To avoid inadvertent plagiarism, make sure to read the University regulations regarding academic integrity as taken from Princeton’s Rights, Rules, Responsibilities .

View, save, or print a PDF with the information contained above .

Princeton University Library

SPECIAL COLLECTIONS

Special Collections Schedule - Summer 2024

The Special Collections reading rooms in Firestone and Mudd Libraries will be closed on the following upcoming holidays: Monday, May 27 (Memorial Day), Wednesday, June 19 (Juneteenth), Thursday, July 4 (Independence Day), and Monday, September 2 (Labor Day). We will be closing at 12:00pm on Friday, June 14. We will also begin our Summer Hours, 9am-4:15pm, on Monday, June 3. During this time we stop paging at 3:45pm.

You are here

- Conducting Research

- Catalogs & Databases

Catalog of Princeton University Senior Theses

Thesistypewriterfou768.jpg.

List of theses starting in 1926 written by seniors at Princeton University. Not all departments are represented. Princeton University network connected patrons may view most 2014 to current theses.

7 Princeton Traditions in My Last Semester

May 16, 2024, amélie lemay.

As a follow-up to my sophomore blog post about 7 traditions in my first on-campus semester , I now present to you 7 traditions from my final semester.

1. Taking 3 courses + thesis

In the final semester, seniors generally take a lighter course load to have additional time to focus on the thesis. This spring I only took 3 courses plus the thesis (which counts as a course), giving me more time to focus on my project than when I have a typical 4-5 course load. This also gave me time for graduate school interviews, student visit days, and other tasks associated with planning for life post-Princeton.

2. Choosing a grad school program

Come March, I was notified of my acceptances to the different graduate school programs I'd applied to. In the fall, I'll be starting a doctoral program in Civil and Environmental Engineering at MIT working with Dr. Desirée Plata! Being able to share this news with my professors and letter of recommendation writers was exciting and rewarding.

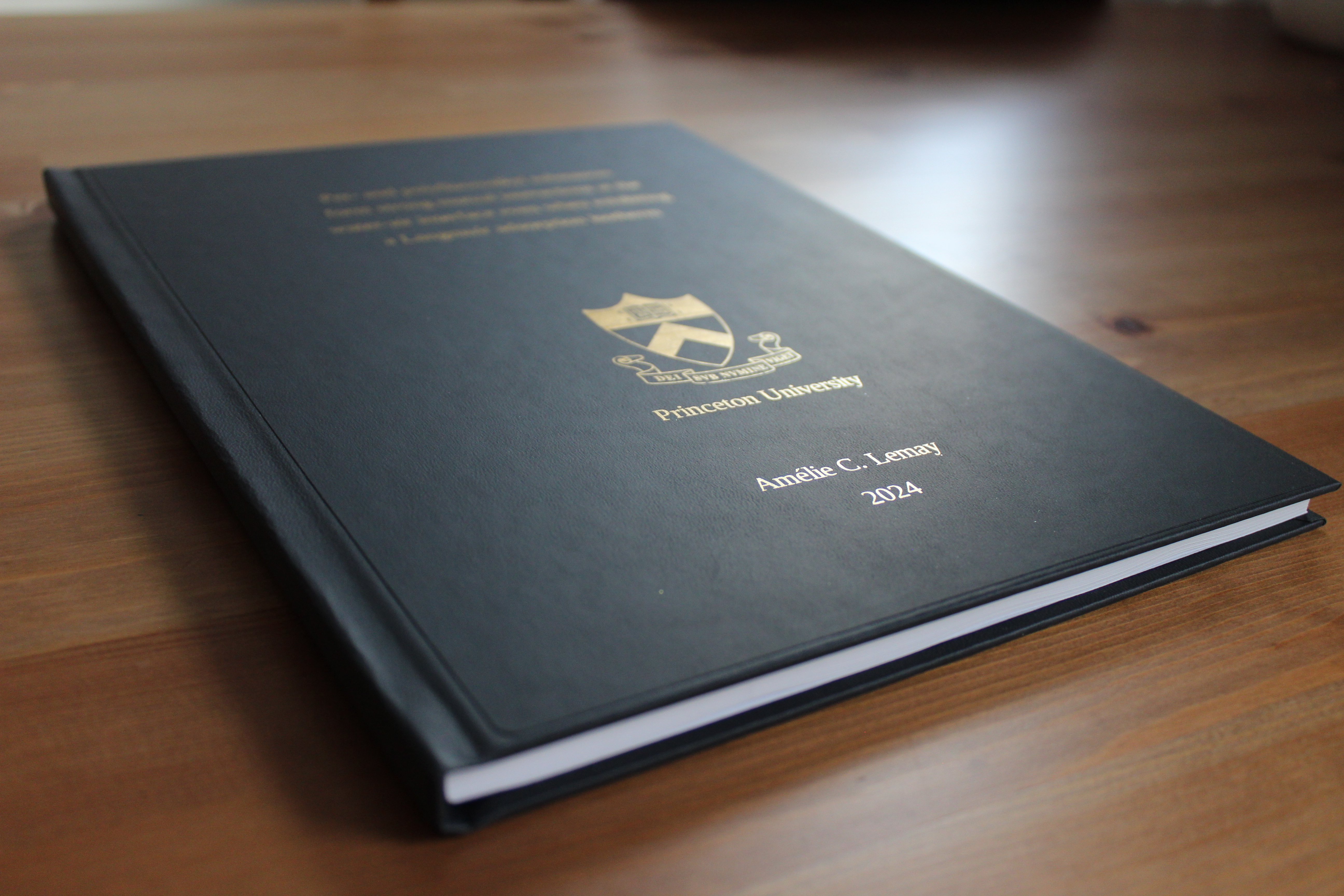

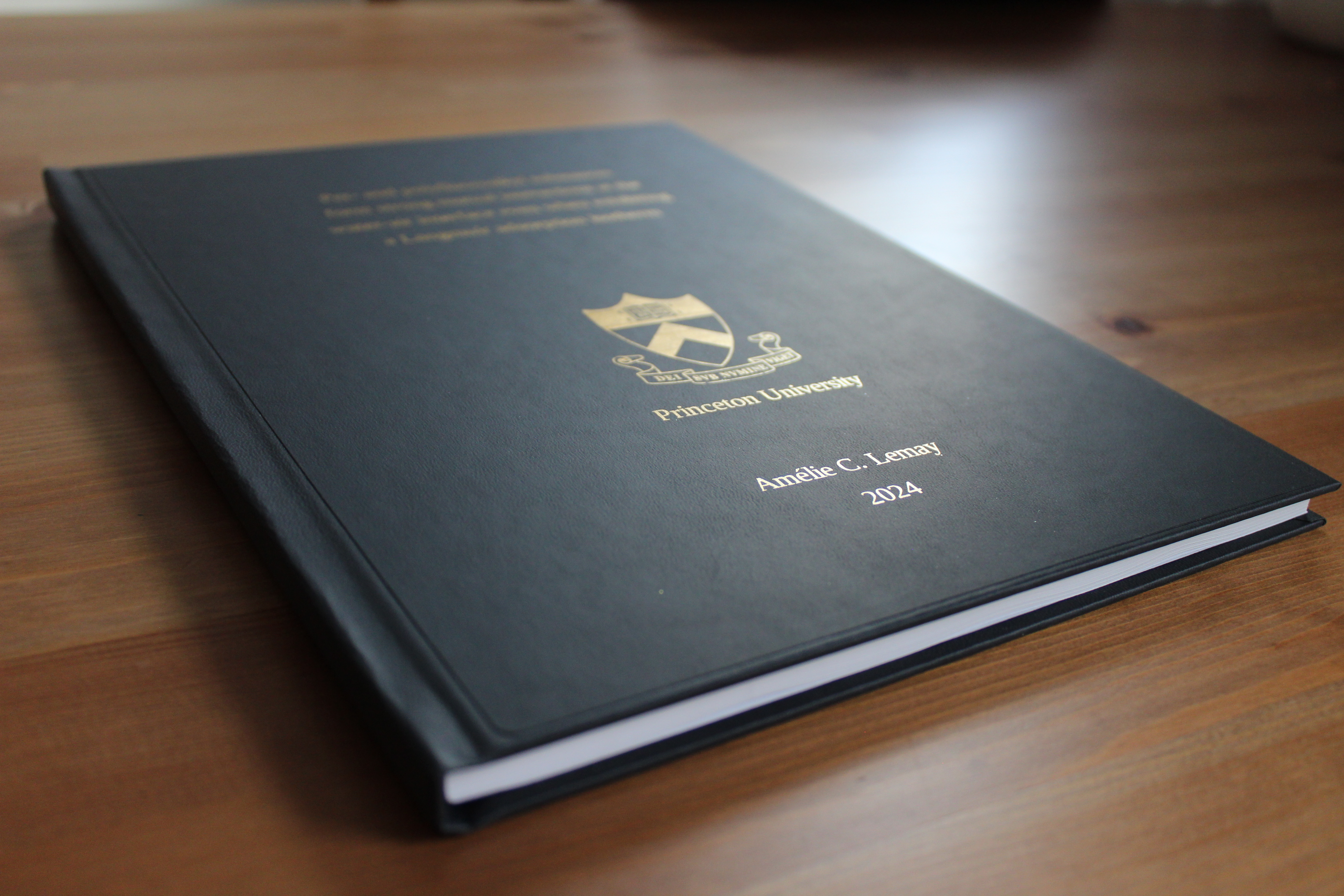

3. Printing and binding my thesis

In mid-April, my thesis was wrapping up, and it was time for official printing and binding. Printing your thesis is optional, but it's traditional to present a leather-bound copy to your advisor. I chose to print my thesis and was incredibly proud to present the culmination of my project to Dr. Bourg.

4. Stepping into the Fountain of Freedom post-thesis submission

Following submission of the thesis, seniors will step into the Fountain of Freedom to officially mark the beginning of the mythical "PTL" (post-thesis life). The water wasn't very warm on the day after my department's thesis submission date (April 15), but I still honored the tradition by stepping into the water.

5. Wearing my class jacket

Formerly known as a " beer jacket ," to be worn by seniors at the Nassau Inn to protect their day clothes, the class jacket is now the de facto uniform for Reunions. The jacket prominently displays your class year, making it easy to spot your classmates among the masses of orange and black that flock to campus for Reunions each May. Our class voted on the design in the fall, and I'm really pleased with the final design.

6. Taking photos by the bronze tigers

Our class government offered free sessions with a pro photographer by the bronze tigers, and I also took photos of my friends myself. We brought numerous graduation props (thesis, class jacket, cap) to the session.

7. Walking through FitzRandolph Gate

At Commencement, I'll walk through FitzRandolph Gate for the first time since the class of 2024 Pre-Rade in my first on-campus semester. Legend has it that students who walk through the gates between the Pre-Rade and Commencement won't graduate in four years. All appears to be on track for me to officially receive my diploma on May 28, but I certainly won't be taking any chances between now and then.

And with that, my undergraduate experience at Princeton has come to a close! I've truly loved my time here, and I'll forever be grateful to Old Nassau.

Related Articles

Commencement commences, amor fati: embracing my path through princeton, plasa’s inaugural latine history series.

7 Princeton Traditions in My Last Semester

May 16, 2024, amélie lemay.

As a follow-up to my sophomore blog post about 7 traditions in my first on-campus semester , I now present to you 7 traditions from my final semester.

1. Taking 3 courses + thesis

In the final semester, seniors generally take a lighter course load to have additional time to focus on the thesis. This spring I only took 3 courses plus the thesis (which counts as a course), giving me more time to focus on my project than when I have a typical 4-5 course load. This also gave me time for graduate school interviews, student visit days, and other tasks associated with planning for life post-Princeton.

2. Choosing a grad school program

Come March, I was notified of my acceptances to the different graduate school programs I'd applied to. In the fall, I'll be starting a doctoral program in Civil and Environmental Engineering at MIT working with Dr. Desirée Plata! Being able to share this news with my professors and letter of recommendation writers was exciting and rewarding.

3. Printing and binding my thesis

In mid-April, my thesis was wrapping up, and it was time for official printing and binding. Printing your thesis is optional, but it's traditional to present a leather-bound copy to your advisor. I chose to print my thesis and was incredibly proud to present the culmination of my project to Dr. Bourg.

4. Stepping into the Fountain of Freedom post-thesis submission

Following submission of the thesis, seniors will step into the Fountain of Freedom to officially mark the beginning of the mythical "PTL" (post-thesis life). The water wasn't very warm on the day after my department's thesis submission date (April 15), but I still honored the tradition by stepping into the water.

5. Wearing my class jacket

Formerly known as a " beer jacket ," to be worn by seniors at the Nassau Inn to protect their day clothes, the class jacket is now the de facto uniform for Reunions. The jacket prominently displays your class year, making it easy to spot your classmates among the masses of orange and black that flock to campus for Reunions each May. Our class voted on the design in the fall, and I'm really pleased with the final design.

6. Taking photos by the bronze tigers

Our class government offered free sessions with a pro photographer by the bronze tigers, and I also took photos of my friends myself. We brought numerous graduation props (thesis, class jacket, cap) to the session.

7. Walking through FitzRandolph Gate

At Commencement, I'll walk through FitzRandolph Gate for the first time since the class of 2024 Pre-Rade in my first on-campus semester. Legend has it that students who walk through the gates between the Pre-Rade and Commencement won't graduate in four years. All appears to be on track for me to officially receive my diploma on May 28, but I certainly won't be taking any chances between now and then.

And with that, my undergraduate experience at Princeton has come to a close! I've truly loved my time here, and I'll forever be grateful to Old Nassau.

Related Articles

Commencement commences, amor fati: embracing my path through princeton, plasa’s inaugural latine history series.

What Six Senior Music Majors’ Say About Their Theses

As the Spring semester concludes and in anticipation for the Class of 2024’s graduation, the Music Department asked six Senior Music Majors to expand on their creative theses and offer advice to future students preparing their own. The Music Department is proud to share the results of each Music Major’s cumulative work at Princeton, which highlights scholarly research and true mastery of their disciplines.

Jared Bozinko

Thesis: SIN PHONY for two soprano clarinets, two auxiliary clarinets, two saxophones, and two horns

Jared: In the process of writing SIN PHONY , I found inspiration in seemingly twee places. Poulenc’s Sonata for horn, trumpet and trombone, Prokofiev’s Romeo and Juliet , a 1995 clarinet quartet by Met Opera clarinetist Sean Osborn, and Ligeti’s Six Bagatelles , a quirky wind quintet version of his Musica ricercata . SIN PHONY is a chamber piece, technically an octet, for clarinets, saxes, and horns. My advisor, Dr. Dmitri Tymoczko, has been indispensable to the process, guiding me all fall semester in writing short chamber music sketches, which became the basis of the material that makes up my thesis. The process was so smooth and, at points, genuinely fun, and it was a great challenge as a composer to blend disparate thematic material from sketches written completely separately into cohesive, compelling music that had cohesion and let my compositional voice shine through.

Tanaka Dunbar Ngwara

Thesis: Paivapo ’76: A New Musical

Tanaka: My thesis was an original musical entitled Paivapo ’76 and set in Domboshava Zimbabwe in 1976, during the Zimbabwean Liberation War. The show deals with the conflict between traditional practice/spirituality and Christianity, and explores themes of community, first love and grief. I received the Alex Adam ’07 Award to conduct research for this project over the summer and since the musical also served as independent work for my theater and music theater certificates, I was able to premiere the piece on May 3rd, 4th and 5th in the Wallace Theater in the Lewis Center Complex.

Thesis: Flung Into Space: A Collection of Songs

Nina: My thesis is a collection of six songs titled Flung Into Space . It consists of three story heavy songs about my life, along with an electronic counterpart for each which explores the same topic from a new perspective.

Rupert Peacock

Thesis: John Farrant’s “O Lord Allmighty (ca. 1570): The English Anthem at Ely Cathedral With Critical Edition

Rupert: My thesis is a critical edition and history surrounding a piece of unpublished English choral music. The piece is called “O Lord Almighty” by John Farrant. I went to the library at Cambridge University and looked through manuscripts from Ely cathedral, which is about 10 minutes from where I live in the UK. I found lots of great and famous choral works, but stumbled across this piece by Farrant almost by accident. Professor Wendy Heller taught me everything I needed to know to get this done. She’s an expert in critical editions and this kind of research. I couldn’t have done it without her.

Molly Trueman

Thesis: Angels & Aliens: The Making of an Album

Molly: For my thesis, I wrote and recorded my debut full-length album entitled Angels & Aliens . Based around acoustic guitar and vocals, the album has an alternative indie-folk feel. This is a milestone I’ve been working towards for a few years now, so I’m incredibly grateful that this album ended up being my thesis.

Gabriela Veciana

Thesis: Breaking the Sound Barrier: Investigating Latine Racial Bias Through Reggaetón Music

Gabriela: For my thesis, I researched colorism within Latine communities through reggaetón music. I knew I was interested in looking at identity and Latin music, but it wasn’t until I heard my advisor, Lisa Margulis, present her work in music cognition that I saw a potential connection with psychology fields.

If you were to describe your thesis in one word, what would it be?

Jared : Darksided (hehe)

Tanaka: Fusion

Nina: Honest

Rupert: Difficult!

Molly: Extraterrestrial

Gabriela: Interdisciplinary!

What advice would you give to future seniors on creating a successful thesis?

Jared: Don’t be afraid that your thesis isn’t going to materialize in time, instead, always try to remember just why you chose this amazing department, and to remember your likely lifelong personal devotion to music. There’s a lot to love about being able to share your art as the capstone of your work at Princeton.

Tanaka: If you can, use the thesis as an opportunity to work on something that you’ve always wanted to do, but never had the time to do! It’s amazing to have the excuse of a thesis project to give you the drive and space to complete it.

Nina: Try to start without judgement. The hardest part of writing my thesis was my own expectations of what my thesis should look like.

Rupert: It has to be something you care about and/or are passionate about. It got to the point where I was actually looking forward to the next steps in my thesis and enjoyed working on it. That was crucial for motivation!

Molly: In terms of creating a thesis, my biggest piece of advice is to find a topic that you’re truly passionate about. Don’t settle for something you don’t care about.

Gabriela: You don’t always have to have a topic and then find an advisor, you can start by finding an advisor you are interested in working with and craft your topic from there.

What are your plans after graduation?

Jared: Still figuring it out, though I’m certain I want music to be a core component of my everyday life. I am trying to move to Philadelphia and get involved with their variety of music scenes, from DIY punk basement shows to chamber orchestras to early music groups. I also want to continue composing and am eager to hone my craft even further wherever I go.

Tanaka: I’m going to attend the Royal Academy of Music for Music Theater vocal performance! I’m very excited to be in a new city, and get to do another music degree in a conservatory.

Nina: I’m moving to Nashville, TN and pursuing a career as a performing musician. I’ll also be releasing music soon as a part of the band Upwhirl, as well as later this year releasing my thesis.

Rupert: I am going to split my time between singing and construction!

Molly: After graduation, I’m going to McGill University to study in the Sound Recording program.

Gabriela: I hope to work in theater administration in New York!

In Other News

Student Perspectives: The Musical Odyssey of Princeton’s Adrian Thananopavarn

Jan 18, 2024

Adrian P. Thananopavarn ’24, Math major with certificates in Computer Science and Music Composition, premieres “March of Dusk” with Princeton University Sinfonia

How 3 Princeton Students Spend a Monday at the Royal College of Music

Dec 7, 2023

Dorothy Junginger ’25, Kyle Tsai ’25, and Audrey Yang ’25 are currently participating in Princeton’s immersive abroad program this semester at the Royal College of Music in London.

Music Major Kasey Shao Named 2024 Gilmore Young Artist

Sep 18, 2023

The Department of Music congratulates Kasey Shao (Class of 2025), a Music Major who is pursuing Minors in Piano Performance and Engineering Biology, who was one of two students named 2024 Gilmore Young Artists. We caught up with Kasey this summer following the official announcement to discuss how she found out she’d been selected, what she has planned for her 2024 Gilmore recitals and piano commission, and what’s on the docket for her final two years at Princeton.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Senior Thesis Guidelines ... "A senior thesis submitted to the History Department of Princeton University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts." ... History Department, Princeton University 129 Dickinson Hall, Princeton, NJ 08544-1017 Phone: 609-258-4159 Fax: 609-258-5326 ...

Senior Thesis Guidelines; Student Expectations; Senior Departmental Examination; Funding Opportunities; Independent Work in History: A Guide; Distribution Reqs; ... History Department, Princeton University 129 Dickinson Hall, Princeton, NJ 08544-1017 Phone: 609-258-4159 Fax: 609-258-5326

Phone: 609-258-4159 Fax: 609-258-5326. Undergraduate: 609-258-6725 · Graduate: 609-258-5529. Email: ·. ·. The Guidelines for the graduate program in History are intended to be a reference for all policies and procedures relevant to the Ph.D. programs in History and History of Science.

History Thesis Guidelines Senior Calendar. Academic Planning Tools. History Major Requirements Office Hours Library Resources. Footer. History Department, Princeton University 129 Dickinson Hall, Princeton, NJ 08544-1017 Phone: 609-258-4159 Fax: 609-258-5326 ...

Any prospective or current graduate student who wishes further information and advice about the fit between the Program's guidelines and their particular circumstances can direct their questions to the Director of Graduate Studies for the History of Science at 107 Dickinson Hall, History Department, Princeton University, Princeton, NJ 08544 ...

Princeton University Library One Washington Road Princeton, NJ 08544-2098 USA (609) 258-1470

Senior Thesis Guidelines; Student Expectations; Senior Departmental Examination; Funding Opportunities; Independent Work in History: A Guide; Distribution Reqs; ... History Department, Princeton University 129 Dickinson Hall, Princeton, NJ 08544-1017 Phone: 609-258-4159 Fax: 609-258-5326

HIS 407 - History Behind the Headlines: Native America in the News. HIS 445: Winston Churchill, Anglo-America, & the "Special Relationship". HIS 450: Abolitionism and the Fall of American Slavery. HIS 562: British Histories/Global Histories, c. 1750-1950. HIS 581: Research Seminar in American History.

For dissertations written from 1989 to the present, search the library catalog for "Princeton University. Dept. of History" as author; for earlier, try a keyword search for "history and thesis and princeton." A card file and a local database at Mudd may help in locating theses that are obscure or missing in the Main Catalog.

The History department has a variety of written resources on its website under the tab "Resources.". These include calendar dates for juniors and seniors to help structure independent work, a guide to independent work for the department, and junior paper and senior thesis guidelines.

Princeton University Undergraduate Senior Theses, 1924-2023 Members of the Princeton community wishing to view a senior thesis from 2014 and later while away from campus should follow the instructions outlined on the OIT website for connecting to campus resources remotely. ... History, 1926-2023 Independent Concentration, 1972-2023

Princeton University Library One Washington Road Princeton, NJ 08544-2098 USA (609) 258-1470

Integral to the senior thesis process is the opportunity to work one-on-one with a faculty member who guides the development of the project. Thesis writers and advisers agree that the most valuable outcome of the senior thesis is the chance for students to enhance skills that are the foundation of future success, including creativity, intellectual engagement, mental discipline and the ability ...

Bound Ph.D. Dissertations in the Mudd Manuscript Library stacks. The Princeton University Archives located within the Seeley G. Mudd Manuscript Library is the official repository for Undergraduate Senior Theses, Master's Theses and Ph.D. Dissertations. Princeton University undergraduate senior theses range from 1924 to the present.

Class of 2024 Senior Thesis Timeline. Thesis Central open to submissions March 25, 2024. Last day for students to submit to Thesis Central is May 7, 2024 (Dean's Date) Review and approvals must be complete by June 24, 2024. Senior Theses are published in DataSpace between late June and prior to the start of the fall semester. About Thesis Central

Thesis Central will be available for student submissions starting in March 25th, 2024 thru the 2024 Dean's date, May 7th, 2024. To access the site, go to the Princeton Thesis Central homepage and login with your netid. Allow roughly 20 minutes to complete the upload process. Note: be sure to check with your home department for additional ...

Students who are enrolled in a thesis-based Master's degree program must upload a PDF of their thesis to Princeton's ETD Administrator site (ProQuest) just prior to completing the final paperwork for the Graduate School. These programs currently include: The Department of Chemical and Biological Engineering (M.S.E.)

History Department, Princeton University 129 Dickinson Hall, Princeton, NJ 08544-1017 Phone: 609-258-4159 Fax: 609-258-5326 Undergraduate: 609-258-6725 · Graduate: 609-258-5529

Limited funding is provided by the School of Engineering and Applied Science for theses which require financial support for special travel needs, acquisition of data, or other special requirements. Awards are typically around 250 to 500 dollars, but not all proposals can be funded.

A JP written in the Department of Near Eastern Studies is normally an essay of 20 to 30 double-spaced pages, while a senior thesis is typically a focused essay of 70 to 100 double-spaced pages (or around 25,000 words of text excluding footnotes). Both focus on topics related to the peoples, history, societies, religions, politics and/or ...

Senior Thesis. The senior thesis is a scholarly paper focused on the policy issue in public or international affairs that is of greatest interest to the student. It is based on extended research and is the major project of the senior year. Each student must complete a senior thesis that addresses a specific policy question and either draws out ...

The collection contains the senior theses of Princeton undergraduates. Not every senior thesis completed by a Princeton student is represented in this collection, as some science-related theses are held at the Lewis Library. Most of the senior theses remain in their original format, however select volumes have been converted to microfiche.

Wednesday. 10/25/2023. Politics Senior Thesis Research Funding Application Due in SAFE by 11:59 PM. Monday. 3/4/2024. Draft of Senior Thesis Due to Advisor by 5:00 PM. Wednesday. 4/3/2024. Senior Thesis Due by 4:00 PM to Department of Politics.

Special Collections Schedule - Summer 2024. The Special Collections reading rooms in Firestone and Mudd Libraries will be closed on the following upcoming holidays: Monday, May 27 (Memorial Day), Wednesday, June 19 (Juneteenth), Thursday, July 4 (Independence Day), and Monday, September 2 (Labor Day). We will be closing at 12:00pm on Friday ...

May 16, 2024. Amélie Lemay. As a follow-up to my sophomore blog post about 7 traditions in my first on-campus semester, I now present to you 7 traditions from my final semester. 1. Taking 3 courses + thesis. In the final semester, seniors generally take a lighter course load to have additional time to focus on the thesis.

Guidelines: Thesis Style Sheet. Submission: For AY 2023-2024, the department is requiring a hardcover bound copy and an electronic copy of your thesis. Both the hardcover bound copy must be dropped off to the English Department office (22 McCosh Hall) and an electronic submission is due to the Senior Thesis Drop Box Folder by April 16, 2024 at ...

May 16, 2024. Amélie Lemay. As a follow-up to my sophomore blog post about 7 traditions in my first on-campus semester, I now present to you 7 traditions from my final semester. 1. Taking 3 courses + thesis. In the final semester, seniors generally take a lighter course load to have additional time to focus on the thesis.

Jennifer Altmann for the Princeton Graduate School. May 16, 2024. The Graduate School has presented 10 graduate students with its annual Teaching Awards in recognition of their outstanding abilities as instructors. Winners were selected by a committee chaired by Lisa Schreyer, deputy dean of the Graduate School, and composed of the academic ...

Rupert: My thesis is a critical edition and history surrounding a piece of unpublished English choral music. The piece is called "O Lord Almighty" by John Farrant. ... Princeton University Music Department Woolworth Center, Princeton, NJ 08544 tel: 609.258.4241 fax: 609.258.6793 . Resources. Student Resources; Faculty Resources;

Senior Thesis Guidelines; Student Expectations; Senior Departmental Examination; ... Two History Seniors Win 2024 Spirit of Princeton Award for Service, Contributions to Campus Life ... History Department, Princeton University 129 Dickinson Hall, Princeton, NJ 08544-1017 Phone: 609-258-4159 Fax: 609-258-5326 ...