How to conduct qualitative interviews (tips and best practices)

Last updated

18 May 2023

Reviewed by

Miroslav Damyanov

However, conducting qualitative interviews can be challenging, even for seasoned researchers. Poorly conducted interviews can lead to inaccurate or incomplete data, significantly compromising the validity and reliability of your research findings.

When planning to conduct qualitative interviews, you must adequately prepare yourself to get the most out of your data. Fortunately, there are specific tips and best practices that can help you conduct qualitative interviews effectively.

- What is a qualitative interview?

A qualitative interview is a research technique used to gather in-depth information about people's experiences, attitudes, beliefs, and perceptions. Unlike a structured questionnaire or survey, a qualitative interview is a flexible, conversational approach that allows the interviewer to delve into the interviewee's responses and explore their insights and experiences.

In a qualitative interview, the researcher typically develops a set of open-ended questions that provide a framework for the conversation. However, the interviewer can also adapt to the interviewee's responses and ask follow-up questions to understand their experiences and views better.

- How to conduct interviews in qualitative research

Conducting interviews involves a well-planned and deliberate process to collect accurate and valid data.

Here’s a step-by-step guide on how to conduct interviews in qualitative research, broken down into three stages:

1. Before the interview

The first step in conducting a qualitative interview is determining your research question . This will help you identify the type of participants you need to recruit . Once you have your research question, you can start recruiting participants by identifying potential candidates and contacting them to gauge their interest in participating in the study.

After that, it's time to develop your interview questions. These should be open-ended questions that will elicit detailed responses from participants. You'll also need to get consent from the participants, ideally in writing, to ensure that they understand the purpose of the study and their rights as participants. Finally, choose a comfortable and private location to conduct the interview and prepare the interview guide.

2. During the interview

Start by introducing yourself and explaining the purpose of the study. Establish a rapport by putting the participants at ease and making them feel comfortable. Use the interview guide to ask the questions, but be flexible and ask follow-up questions to gain more insight into the participants' responses.

Take notes during the interview, and ask permission to record the interview for transcription purposes. Be mindful of the time, and cover all the questions in the interview guide.

3. After the interview

Once the interview is over, transcribe the interview if you recorded it. If you took notes, review and organize them to make sure you capture all the important information. Then, analyze the data you collected by identifying common themes and patterns. Use the findings to answer your research question.

Finally, debrief with the participants to thank them for their time, provide feedback on the study, and answer any questions they may have.

- What kinds of questions should you ask in a qualitative interview?

Qualitative interviews involve asking questions that encourage participants to share their experiences, opinions, and perspectives on a particular topic. These questions are designed to elicit detailed and nuanced responses rather than simple yes or no answers.

Effective questions in a qualitative interview are generally open-ended and non-leading. They avoid presuppositions or assumptions about the participant's experience and allow them to share their views in their own words.

In customer research , you might ask questions such as:

What motivated you to choose our product/service over our competitors?

How did you first learn about our product/service?

Can you walk me through your experience with our product/service?

What improvements or changes would you suggest for our product/service?

Have you recommended our product/service to others, and if so, why?

The key is to ask questions relevant to the research topic and allow participants to share their experiences meaningfully and informally.

- How to determine the right qualitative interview participants

Choosing the right participants for a qualitative interview is a crucial step in ensuring the success and validity of the research . You need to consider several factors to determine the right participants for a qualitative interview. These may include:

Relevant experiences : Participants should have experiences related to the research topic that can provide valuable insights.

Diversity : Aim to include diverse participants to ensure the study's findings are representative and inclusive.

Access : Identify participants who are accessible and willing to participate in the study.

Informed consent : Participants should be fully informed about the study's purpose, methods, and potential risks and benefits and be allowed to provide informed consent.

You can use various recruitment methods, such as posting ads in relevant forums, contacting community organizations or social media groups, or using purposive sampling to identify participants who meet specific criteria.

- How to make qualitative interview subjects comfortable

Making participants comfortable during a qualitative interview is essential to obtain rich, detailed data. Participants are more likely to share their experiences openly when they feel at ease and not judged.

Here are some ways to make interview subjects comfortable:

Explain the purpose of the study

Start the interview by explaining the research topic and its importance. The goal is to give participants a sense of what to expect.

Create a comfortable environment

Conduct the interview in a quiet, private space where the participant feels comfortable. Turn off any unnecessary electronics that can create distractions. Ensure your equipment works well ahead of time. Arrive at the interview on time. If you conduct a remote interview, turn on your camera and mute all notetakers and observers.

Build rapport

Greet the participant warmly and introduce yourself. Show interest in their responses and thank them for their time.

Use open-ended questions

Ask questions that encourage participants to elaborate on their thoughts and experiences.

Listen attentively

Resist the urge to multitask . Pay attention to the participant's responses, nod your head, or make supportive comments to show you’re interested in their answers. Avoid interrupting them.

Avoid judgment

Show respect and don't judge the participant's views or experiences. Allow the participant to speak freely without feeling judged or ridiculed.

Offer breaks

If needed, offer breaks during the interview, especially if the topic is sensitive or emotional.

Creating a comfortable environment and establishing rapport with the participant fosters an atmosphere of trust and encourages open communication. This helps participants feel at ease and willing to share their experiences.

- How to analyze a qualitative interview

Analyzing a qualitative interview involves a systematic process of examining the data collected to identify patterns, themes, and meanings that emerge from the responses.

Here are some steps on how to analyze a qualitative interview:

1. Transcription

The first step is transcribing the interview into text format to have a written record of the conversation. This step is essential to ensure that you can refer back to the interview data and identify the important aspects of the interview.

2. Data reduction

Once you’ve transcribed the interview, read through it to identify key themes, patterns, and phrases emerging from the data. This process involves reducing the data into more manageable pieces you can easily analyze.

The next step is to code the data by labeling sections of the text with descriptive words or phrases that reflect the data's content. Coding helps identify key themes and patterns from the interview data.

4. Categorization

After coding, you should group the codes into categories based on their similarities. This process helps to identify overarching themes or sub-themes that emerge from the data.

5. Interpretation

You should then interpret the themes and sub-themes by identifying relationships, contradictions, and meanings that emerge from the data. Interpretation involves analyzing the themes in the context of the research question .

6. Comparison

The next step is comparing the data across participants or groups to identify similarities and differences. This step helps to ensure that the findings aren’t just specific to one participant but can be generalized to the wider population.

7. Triangulation

To ensure the findings are valid and reliable, you should use triangulation by comparing the findings with other sources, such as observations or interview data.

8. Synthesis

The final step is synthesizing the findings by summarizing the key themes and presenting them clearly and concisely. This step involves writing a report that presents the findings in a way that is easy to understand, using quotes and examples from the interview data to illustrate the themes.

- Tips for transcribing a qualitative interview

Transcribing a qualitative interview is a crucial step in the research process. It involves converting the audio or video recording of the interview into written text.

Here are some tips for transcribing a qualitative interview:

Use transcription software

Transcription software can save time and increase accuracy by automatically transcribing audio or video recordings.

Listen carefully

When manually transcribing, listen carefully to the recording to ensure clarity. Pause and rewind the recording as necessary.

Use appropriate formatting

Use a consistent format for transcribing, such as marking pauses, overlaps, and interruptions. Indicate non-verbal cues such as laughter, sighs, or changes in tone.

Edit for clarity

Edit the transcription to ensure clarity and readability. Use standard grammar and punctuation, correct misspellings, and remove filler words like "um" and "ah."

Proofread and edit

Verify the accuracy of the transcription by listening to the recording again and reviewing the notes taken during the interview.

Use timestamps

Add timestamps to the transcription to reference specific interview sections.

Transcribing a qualitative interview can be time-consuming, but it’s essential to ensure the accuracy of the data collected. Following these tips can produce high-quality transcriptions useful for analysis and reporting.

- Why are interview techniques in qualitative research effective?

Unlike quantitative research methods, which rely on numerical data, qualitative research seeks to understand the richness and complexity of human experiences and perspectives.

Interview techniques involve asking open-ended questions that allow participants to express their views and share their stories in their own words. This approach can help researchers to uncover unexpected or surprising insights that may not have been discovered through other research methods.

Interview techniques also allow researchers to establish rapport with participants, creating a comfortable and safe space for them to share their experiences. This can lead to a deeper level of trust and candor, leading to more honest and authentic responses.

- What are the weaknesses of qualitative interviews?

Qualitative interviews are an excellent research approach when used properly, but they have their drawbacks.

The weaknesses of qualitative interviews include the following:

Subjectivity and personal biases

Qualitative interviews rely on the researcher's interpretation of the interviewee's responses. The researcher's biases or preconceptions can affect how the questions are framed and how the responses are interpreted, which can influence results.

Small sample size

The sample size in qualitative interviews is often small, which can limit the generalizability of the results to the larger population.

Data quality

The quality of data collected during interviews can be affected by various factors, such as the interviewee's mood, the setting of the interview, and the interviewer's skills and experience.

Socially desirable responses

Interviewees may provide responses that they believe are socially acceptable rather than truthful or genuine.

Conducting qualitative interviews can be expensive, especially if the researcher must travel to different locations to conduct the interviews.

Time-consuming

The data analysis process can be time-consuming and labor-intensive, as researchers need to transcribe and analyze the data manually.

Despite these weaknesses, qualitative interviews remain a valuable research tool . You can take steps to mitigate the impact of these weaknesses by incorporating the perspectives of other researchers or participants in the analysis process, using multiple data sources , and critically analyzing your biases and assumptions.

Mastering the art of qualitative interviews is an essential skill for businesses looking to gain deep insights into their customers' needs , preferences, and behaviors. By following the tips and best practices outlined in this article, you can conduct interviews that provide you with rich data that you can use to make informed decisions about your products, services, and marketing strategies.

Remember that effective communication, active listening, and proper analysis are critical components of successful qualitative interviews. By incorporating these practices into your customer research, you can gain a competitive edge and build stronger customer relationships.

Should you be using a customer insights hub?

Do you want to discover previous research faster?

Do you share your research findings with others?

Do you analyze research data?

Start for free today, add your research, and get to key insights faster

Editor’s picks

Last updated: 11 January 2024

Last updated: 15 January 2024

Last updated: 17 January 2024

Last updated: 12 May 2023

Last updated: 30 April 2024

Last updated: 18 May 2023

Last updated: 25 November 2023

Last updated: 13 May 2024

Latest articles

Related topics, .css-je19u9{-webkit-align-items:flex-end;-webkit-box-align:flex-end;-ms-flex-align:flex-end;align-items:flex-end;display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-flex-direction:row;-ms-flex-direction:row;flex-direction:row;-webkit-box-flex-wrap:wrap;-webkit-flex-wrap:wrap;-ms-flex-wrap:wrap;flex-wrap:wrap;-webkit-box-pack:center;-ms-flex-pack:center;-webkit-justify-content:center;justify-content:center;row-gap:0;text-align:center;max-width:671px;}@media (max-width: 1079px){.css-je19u9{max-width:400px;}.css-je19u9>span{white-space:pre;}}@media (max-width: 799px){.css-je19u9{max-width:400px;}.css-je19u9>span{white-space:pre;}} decide what to .css-1kiodld{max-height:56px;display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;}@media (max-width: 1079px){.css-1kiodld{display:none;}} build next, decide what to build next.

Users report unexpectedly high data usage, especially during streaming sessions.

Users find it hard to navigate from the home page to relevant playlists in the app.

It would be great to have a sleep timer feature, especially for bedtime listening.

I need better filters to find the songs or artists I’m looking for.

Log in or sign up

Get started for free

Root out friction in every digital experience, super-charge conversion rates, and optimize digital self-service

Uncover insights from any interaction, deliver AI-powered agent coaching, and reduce cost to serve

Increase revenue and loyalty with real-time insights and recommendations delivered to teams on the ground

Know how your people feel and empower managers to improve employee engagement, productivity, and retention

Take action in the moments that matter most along the employee journey and drive bottom line growth

Whatever they’re are saying, wherever they’re saying it, know exactly what’s going on with your people

Get faster, richer insights with qual and quant tools that make powerful market research available to everyone

Run concept tests, pricing studies, prototyping + more with fast, powerful studies designed by UX research experts

Track your brand performance 24/7 and act quickly to respond to opportunities and challenges in your market

Explore the platform powering Experience Management

- Free Account

- For Digital

- For Customer Care

- For Human Resources

- For Researchers

- Financial Services

- All Industries

Popular Use Cases

- Customer Experience

- Employee Experience

- Net Promoter Score

- Voice of Customer

- Customer Success Hub

- Product Documentation

- Training & Certification

- XM Institute

- Popular Resources

- Customer Stories

- Artificial Intelligence

Market Research

- Partnerships

- Marketplace

The annual gathering of the experience leaders at the world’s iconic brands building breakthrough business results, live in Salt Lake City.

- English/AU & NZ

- Español/Europa

- Español/América Latina

- Português Brasileiro

- REQUEST DEMO

- Experience Management

- Qualitative Research Interviews

Try Qualtrics for free

How to carry out great interviews in qualitative research.

11 min read An interview is one of the most versatile methods used in qualitative research. Here’s what you need to know about conducting great qualitative interviews.

What is a qualitative research interview?

Qualitative research interviews are a mainstay among q ualitative research techniques, and have been in use for decades either as a primary data collection method or as an adjunct to a wider research process. A qualitative research interview is a one-to-one data collection session between a researcher and a participant. Interviews may be carried out face-to-face, over the phone or via video call using a service like Skype or Zoom.

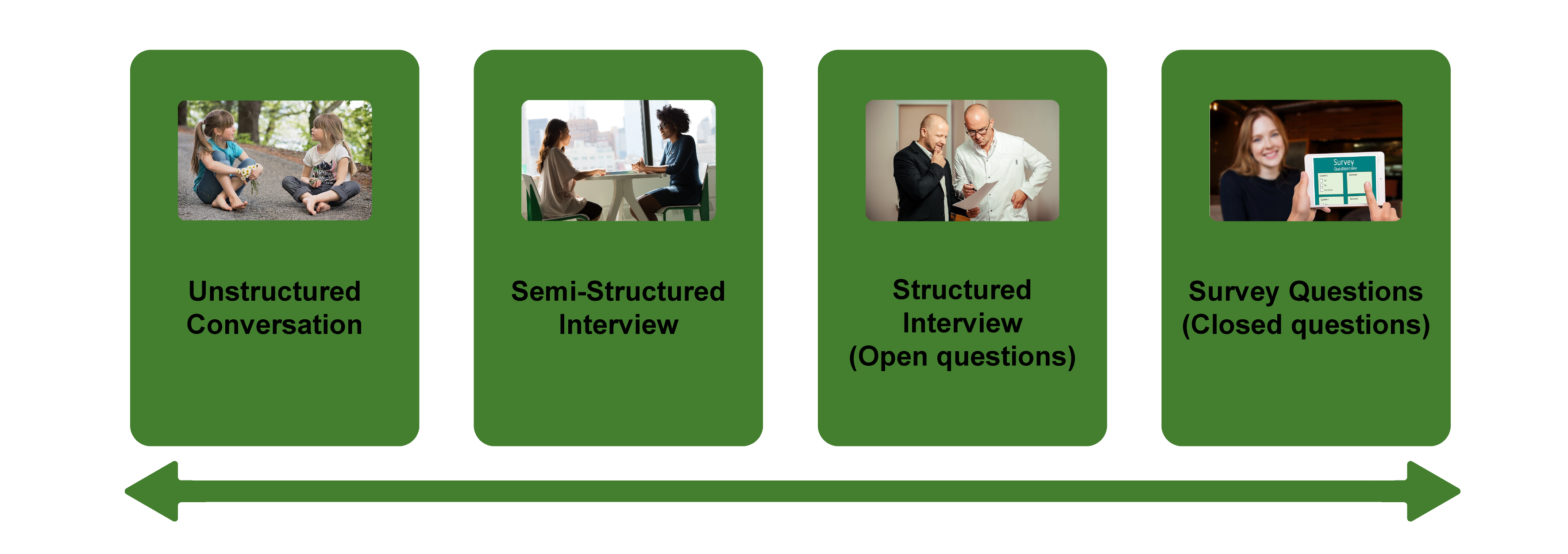

There are three main types of qualitative research interview – structured, unstructured or semi-structured.

- Structured interviews Structured interviews are based around a schedule of predetermined questions and talking points that the researcher has developed. At their most rigid, structured interviews may have a precise wording and question order, meaning that they can be replicated across many different interviewers and participants with relatively consistent results.

- Unstructured interviews Unstructured interviews have no predetermined format, although that doesn’t mean they’re ad hoc or unplanned. An unstructured interview may outwardly resemble a normal conversation, but the interviewer will in fact be working carefully to make sure the right topics are addressed during the interaction while putting the participant at ease with a natural manner.

- Semi-structured interviews Semi-structured interviews are the most common type of qualitative research interview, combining the informality and rapport of an unstructured interview with the consistency and replicability of a structured interview. The researcher will come prepared with questions and topics, but will not need to stick to precise wording. This blended approach can work well for in-depth interviews.

Free eBook: The qualitative research design handbook

What are the pros and cons of interviews in qualitative research?

As a qualitative research method interviewing is hard to beat, with applications in social research, market research, and even basic and clinical pharmacy. But like any aspect of the research process, it’s not without its limitations. Before choosing qualitative interviewing as your research method, it’s worth weighing up the pros and cons.

Pros of qualitative interviews:

- provide in-depth information and context

- can be used effectively when their are low numbers of participants

- provide an opportunity to discuss and explain questions

- useful for complex topics

- rich in data – in the case of in-person or video interviews , the researcher can observe body language and facial expression as well as the answers to questions

Cons of qualitative interviews:

- can be time-consuming to carry out

- costly when compared to some other research methods

- because of time and cost constraints, they often limit you to a small number of participants

- difficult to standardize your data across different researchers and participants unless the interviews are very tightly structured

- As the Open University of Hong Kong notes, qualitative interviews may take an emotional toll on interviewers

Qualitative interview guides

Semi-structured interviews are based on a qualitative interview guide, which acts as a road map for the researcher. While conducting interviews, the researcher can use the interview guide to help them stay focused on their research questions and make sure they cover all the topics they intend to.

An interview guide may include a list of questions written out in full, or it may be a set of bullet points grouped around particular topics. It can prompt the interviewer to dig deeper and ask probing questions during the interview if appropriate.

Consider writing out the project’s research question at the top of your interview guide, ahead of the interview questions. This may help you steer the interview in the right direction if it threatens to head off on a tangent.

Avoid bias in qualitative research interviews

According to Duke University , bias can create significant problems in your qualitative interview.

- Acquiescence bias is common to many qualitative methods, including focus groups. It occurs when the participant feels obliged to say what they think the researcher wants to hear. This can be especially problematic when there is a perceived power imbalance between participant and interviewer. To counteract this, Duke University’s experts recommend emphasizing the participant’s expertise in the subject being discussed, and the value of their contributions.

- Interviewer bias is when the interviewer’s own feelings about the topic come to light through hand gestures, facial expressions or turns of phrase. Duke’s recommendation is to stick to scripted phrases where this is an issue, and to make sure researchers become very familiar with the interview guide or script before conducting interviews, so that they can hone their delivery.

What kinds of questions should you ask in a qualitative interview?

The interview questions you ask need to be carefully considered both before and during the data collection process. As well as considering the topics you’ll cover, you will need to think carefully about the way you ask questions.

Open-ended interview questions – which cannot be answered with a ‘yes’ ‘no’ or ‘maybe’ – are recommended by many researchers as a way to pursue in depth information.

An example of an open-ended question is “What made you want to move to the East Coast?” This will prompt the participant to consider different factors and select at least one. Having thought about it carefully, they may give you more detailed information about their reasoning.

A closed-ended question , such as “Would you recommend your neighborhood to a friend?” can be answered without too much deliberation, and without giving much information about personal thoughts, opinions and feelings.

Follow-up questions can be used to delve deeper into the research topic and to get more detail from open-ended questions. Examples of follow-up questions include:

- What makes you say that?

- What do you mean by that?

- Can you tell me more about X?

- What did/does that mean to you?

As well as avoiding closed-ended questions, be wary of leading questions. As with other qualitative research techniques such as surveys or focus groups, these can introduce bias in your data. Leading questions presume a certain point of view shared by the interviewer and participant, and may even suggest a foregone conclusion.

An example of a leading question might be: “You moved to New York in 1990, didn’t you?” In answering the question, the participant is much more likely to agree than disagree. This may be down to acquiescence bias or a belief that the interviewer has checked the information and already knows the correct answer.

Other leading questions involve adjectival phrases or other wording that introduces negative or positive connotations about a particular topic. An example of this kind of leading question is: “Many employees dislike wearing masks to work. How do you feel about this?” It presumes a positive opinion and the participant may be swayed by it, or not want to contradict the interviewer.

Harvard University’s guidelines for qualitative interview research add that you shouldn’t be afraid to ask embarrassing questions – “if you don’t ask, they won’t tell.” Bear in mind though that too much probing around sensitive topics may cause the interview participant to withdraw. The Harvard guidelines recommend leaving sensitive questions til the later stages of the interview when a rapport has been established.

More tips for conducting qualitative interviews

Observing a participant’s body language can give you important data about their thoughts and feelings. It can also help you decide when to broach a topic, and whether to use a follow-up question or return to the subject later in the interview.

Be conscious that the participant may regard you as the expert, not themselves. In order to make sure they express their opinions openly, use active listening skills like verbal encouragement and paraphrasing and clarifying their meaning to show how much you value what they are saying.

Remember that part of the goal is to leave the interview participant feeling good about volunteering their time and their thought process to your research. Aim to make them feel empowered , respected and heard.

Unstructured interviews can demand a lot of a researcher, both cognitively and emotionally. Be sure to leave time in between in-depth interviews when scheduling your data collection to make sure you maintain the quality of your data, as well as your own well-being .

Recording and transcribing interviews

Historically, recording qualitative research interviews and then transcribing the conversation manually would have represented a significant part of the cost and time involved in research projects that collect qualitative data.

Fortunately, researchers now have access to digital recording tools, and even speech-to-text technology that can automatically transcribe interview data using AI and machine learning. This type of tool can also be used to capture qualitative data from qualitative research (focus groups,ect.) making this kind of social research or market research much less time consuming.

Data analysis

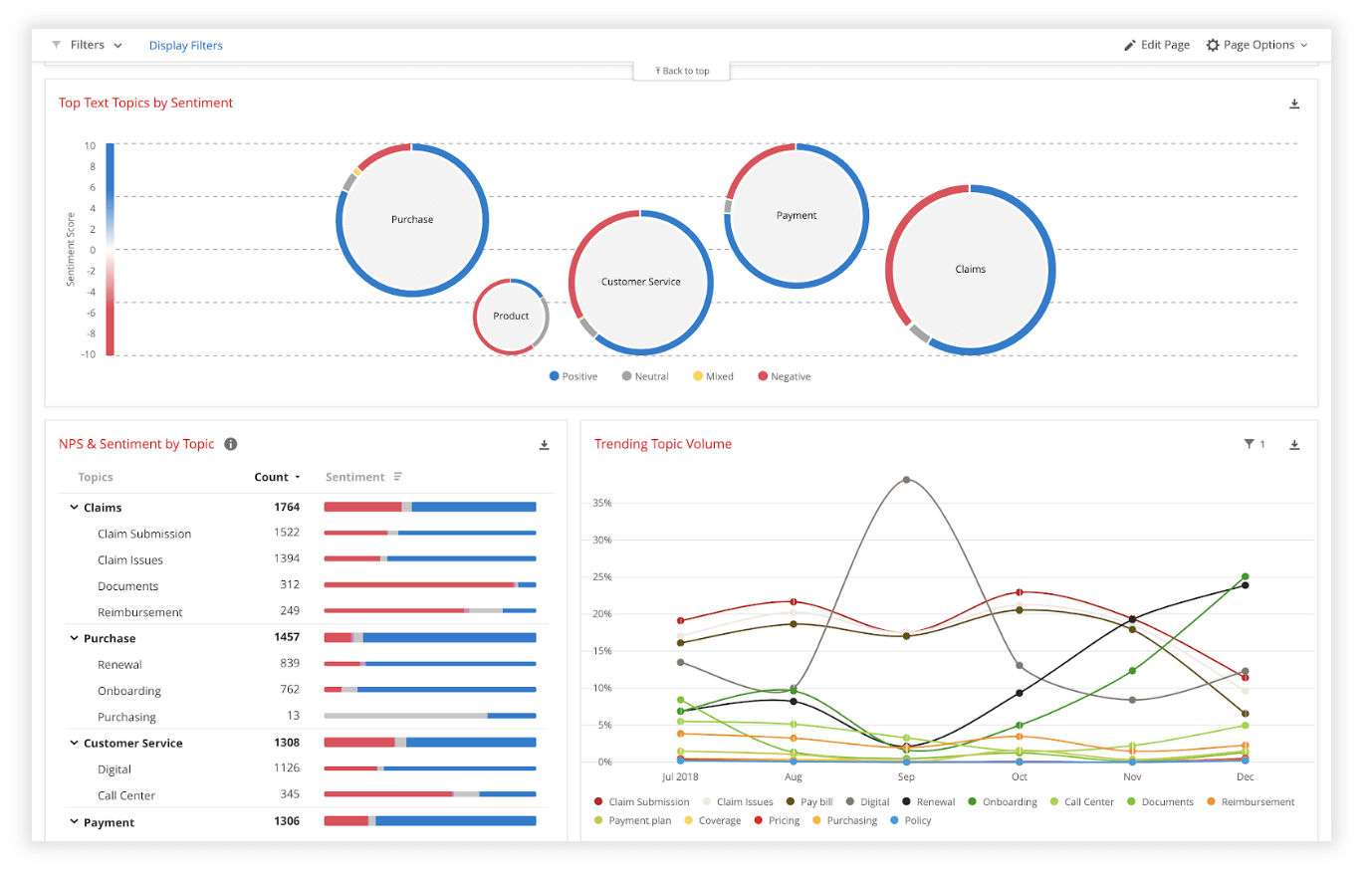

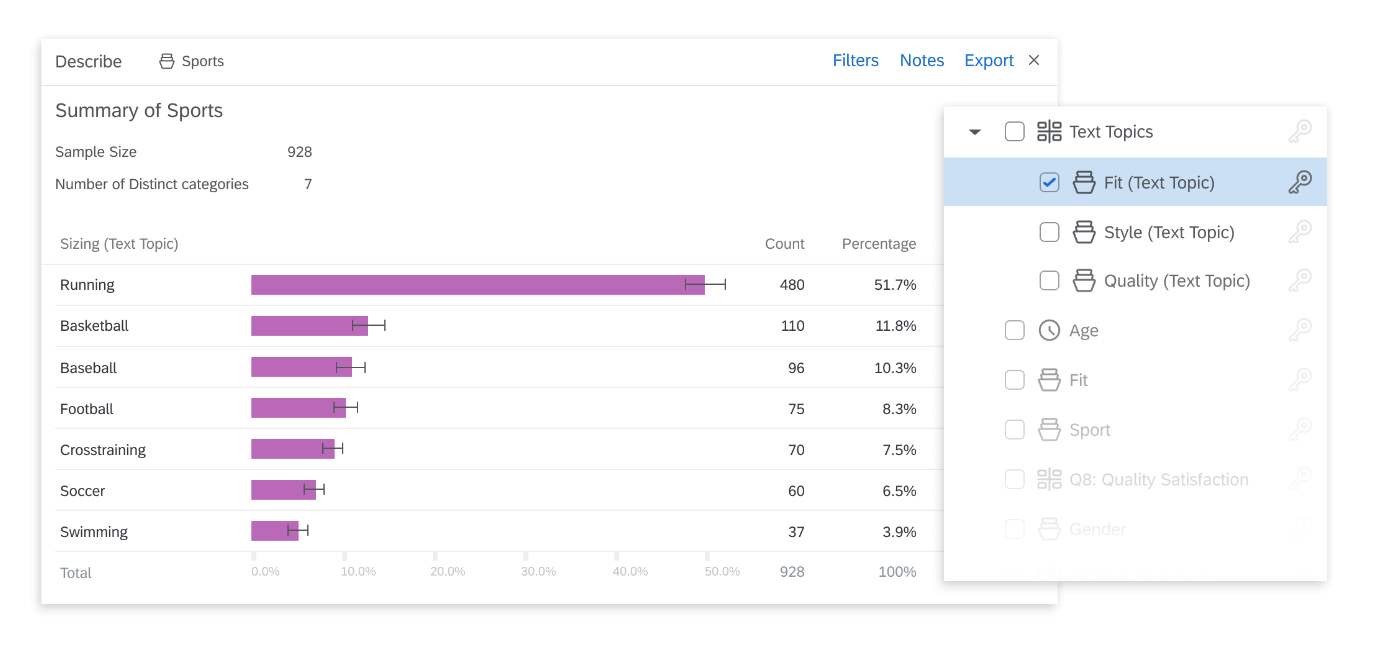

Qualitative interview data is unstructured, rich in content and difficult to analyze without the appropriate tools. Fortunately, machine learning and AI can once again make things faster and easier when you use qualitative methods like the research interview.

Text analysis tools and natural language processing software can ‘read’ your transcripts and voice data and identify patterns and trends across large volumes of text or speech. They can also perform khttps://www.qualtrics.com/experience-management/research/sentiment-analysis/

which assesses overall trends in opinion and provides an unbiased overall summary of how participants are feeling.

Another feature of text analysis tools is their ability to categorize information by topic, sorting it into groupings that help you organize your data according to the topic discussed.

All in all, interviews are a valuable technique for qualitative research in business, yielding rich and detailed unstructured data. Historically, they have only been limited by the human capacity to interpret and communicate results and conclusions, which demands considerable time and skill.

When you combine this data with AI tools that can interpret it quickly and automatically, it becomes easy to analyze and structure, dovetailing perfectly with your other business data. An additional benefit of natural language analysis tools is that they are free of subjective biases, and can replicate the same approach across as much data as you choose. By combining human research skills with machine analysis, qualitative research methods such as interviews are more valuable than ever to your business.

Related resources

Market intelligence 10 min read, marketing insights 11 min read, ethnographic research 11 min read, qualitative vs quantitative research 13 min read, qualitative research questions 11 min read, qualitative research design 12 min read, primary vs secondary research 14 min read, request demo.

Ready to learn more about Qualtrics?

Five Tips for Conducting Effective Qualitative Interviews

An interviewer conducts household survey in rural El Salvador for a Center for Health Policy and Inequalities Research study. Photo by Hy V. Huynh.

Published March 12, 2018 under Research News

In qualitative research, in-depth interviews can be an immensely helpful investigative tool. However, the nuances of one-on-one interviewing can sometimes make it difficult to obtain useful results. Rae Jean Proeschold-Bell , associate research professor and founding director of the Evidence Lab at the Duke Global Health Institute, frequently integrates qualitative interviews into her research. In this article, she shares five interviewing tips that have served her well.

1. Convey Intent

Proeschold-Bell says it’s important for the interviewer to know the intent behind each question so that it can be clearly conveyed to the interviewee. Understanding the intent of a question, she’s found, helps interviewers decide whether or not the participant has fully answered the question. This way, they can ask follow-up questions and not leave gaps at the time of data collection. Proeschold-Bell recommends writing the intent of each question below it in italics on the interview script.

Proeschold-Bell also suggests a few more subtle techniques for helping interviewees understand what is really being asked and soliciting pertinent and thorough responses. Asking the question in several different ways can help clarify its meaning. Follow-up prompts such as “That’s really helpful; tell me more about that,” or “Can you describe what was unpleasant about it?” can also give interviewees helpful guidance in crafting their responses.

“You can also convey intent by explaining more broadly why you’re doing the research, so interviewees will be more likely to give you relevant information,” Proeschold-Bell said.

2. Don’t Sway the Participants

Acquiescence bias, which occurs when interviewees agree with what they think the interviewer wants to hear instead of giving their unbiased answer, can often prevent interviewees from sharing all relevant information. Research from Focus Groups: A Practical Guide for Applied Research shows that when power dynamics are present in an interview, it may be especially difficult for an interviewee to give an honest answer.

To minimize acquiescence bias, interviewers can emphasize that the participant is the expert in the subject matter of the interview. For example, they can start the interview by saying, “I’ve asked you to talk with me today because you are an expert in what it’s like to be a patient in Eldoret.”

Interviewers should also avoid nodding or other body language that expresses agreement with the participant. Instead, interviewers should say, “That’s very helpful,” or “Thank you for those thoughts.” Otherwise, participants might elaborate on a point that isn’t actually very important to them just because the interviewer seemed to agree.

Proeschold-Bell also recommends that interviewers pay attention to—and record—interviewees’ non-verbal responses, which often communicate feelings and attitudes that the verbal response doesn’t capture.

3. Eliminate Interviewer Bias

Proeschold-Bell says it’s critically important to eliminate interviewer bias through the interview process. Knowing the interview guide extremely well helps an interviewer pace the interview to avoid running out of time, and adhering to the scripted wording for each question helps maintain unbiased prompting across all interviews. Additionally, if an interviewee starts answering a question that is going to be asked later, the interviewer can ask them to wait.

It’s best to ask interview questions in a specific order because covering certain questions first may influence how interviewees think during later questions. Finally, she recommends, “Ask all questions of all respondents, even if you think you know what they’ll say. They will surprise you sometimes!”

4. Consider a “Test Run” Period

Proeschold-Bell sees her first several interviews for a study as pilots. Learning from these first few test runs and improving questions and interview techniques for future interviews can have a significant impact on the quality of the study. This means that data quality from the first few interviews may not be as strong since some of the questions change, but the data from the interviews later on will be more useful. Proeschold-Bell recommends numbering interviews chronologically to link interviews to the phase of development in which they were conducted.

5. Make Time for Post-Interview Reflection

After an interview, Proeschold-Bell recommends immediately reviewing the data. “This helps capture good ideas that may otherwise be forgotten,” she says. In fact, she suggests creating a review form with a few open-ended questions that can help capture strong reactions and flag questions that didn’t work well or questions that should be added.

It’s also helpful, she says, to note responses that were different from those given in previous interviews. Doing this may generate ideas to analyze more carefully later on.

Looking for more research design tools? Check out Proeschold-Bell’s recent article, “ Five Tips for Designing an Effective Survey .”

Proeschold-Bell recommends that interviewers pay attention to—and record—interviewees’ non-verbal responses, which often communicate feelings and attitudes that the verbal response doesn’t capture.

- Rae Jean Proeschold-Bell

Related News

Around DGHI

DGHI Sends Off the Class of 2024

May 13, 2024

Student Stories

Student Spotlight: Yesel Trillo-Ordonez MS’GH’25

May 2, 2024

Centering Maternal and Infant Health in the Workplace

Chapter 11. Interviewing

Introduction.

Interviewing people is at the heart of qualitative research. It is not merely a way to collect data but an intrinsically rewarding activity—an interaction between two people that holds the potential for greater understanding and interpersonal development. Unlike many of our daily interactions with others that are fairly shallow and mundane, sitting down with a person for an hour or two and really listening to what they have to say is a profound and deep enterprise, one that can provide not only “data” for you, the interviewer, but also self-understanding and a feeling of being heard for the interviewee. I always approach interviewing with a deep appreciation for the opportunity it gives me to understand how other people experience the world. That said, there is not one kind of interview but many, and some of these are shallower than others. This chapter will provide you with an overview of interview techniques but with a special focus on the in-depth semistructured interview guide approach, which is the approach most widely used in social science research.

An interview can be variously defined as “a conversation with a purpose” ( Lune and Berg 2018 ) and an attempt to understand the world from the point of view of the person being interviewed: “to unfold the meaning of peoples’ experiences, to uncover their lived world prior to scientific explanations” ( Kvale 2007 ). It is a form of active listening in which the interviewer steers the conversation to subjects and topics of interest to their research but also manages to leave enough space for those interviewed to say surprising things. Achieving that balance is a tricky thing, which is why most practitioners believe interviewing is both an art and a science. In my experience as a teacher, there are some students who are “natural” interviewers (often they are introverts), but anyone can learn to conduct interviews, and everyone, even those of us who have been doing this for years, can improve their interviewing skills. This might be a good time to highlight the fact that the interview is a product between interviewer and interviewee and that this product is only as good as the rapport established between the two participants. Active listening is the key to establishing this necessary rapport.

Patton ( 2002 ) makes the argument that we use interviews because there are certain things that are not observable. In particular, “we cannot observe feelings, thoughts, and intentions. We cannot observe behaviors that took place at some previous point in time. We cannot observe situations that preclude the presence of an observer. We cannot observe how people have organized the world and the meanings they attach to what goes on in the world. We have to ask people questions about those things” ( 341 ).

Types of Interviews

There are several distinct types of interviews. Imagine a continuum (figure 11.1). On one side are unstructured conversations—the kind you have with your friends. No one is in control of those conversations, and what you talk about is often random—whatever pops into your head. There is no secret, underlying purpose to your talking—if anything, the purpose is to talk to and engage with each other, and the words you use and the things you talk about are a little beside the point. An unstructured interview is a little like this informal conversation, except that one of the parties to the conversation (you, the researcher) does have an underlying purpose, and that is to understand the other person. You are not friends speaking for no purpose, but it might feel just as unstructured to the “interviewee” in this scenario. That is one side of the continuum. On the other side are fully structured and standardized survey-type questions asked face-to-face. Here it is very clear who is asking the questions and who is answering them. This doesn’t feel like a conversation at all! A lot of people new to interviewing have this ( erroneously !) in mind when they think about interviews as data collection. Somewhere in the middle of these two extreme cases is the “ semistructured” interview , in which the researcher uses an “interview guide” to gently move the conversation to certain topics and issues. This is the primary form of interviewing for qualitative social scientists and will be what I refer to as interviewing for the rest of this chapter, unless otherwise specified.

Informal (unstructured conversations). This is the most “open-ended” approach to interviewing. It is particularly useful in conjunction with observational methods (see chapters 13 and 14). There are no predetermined questions. Each interview will be different. Imagine you are researching the Oregon Country Fair, an annual event in Veneta, Oregon, that includes live music, artisan craft booths, face painting, and a lot of people walking through forest paths. It’s unlikely that you will be able to get a person to sit down with you and talk intensely about a set of questions for an hour and a half. But you might be able to sidle up to several people and engage with them about their experiences at the fair. You might have a general interest in what attracts people to these events, so you could start a conversation by asking strangers why they are here or why they come back every year. That’s it. Then you have a conversation that may lead you anywhere. Maybe one person tells a long story about how their parents brought them here when they were a kid. A second person talks about how this is better than Burning Man. A third person shares their favorite traveling band. And yet another enthuses about the public library in the woods. During your conversations, you also talk about a lot of other things—the weather, the utilikilts for sale, the fact that a favorite food booth has disappeared. It’s all good. You may not be able to record these conversations. Instead, you might jot down notes on the spot and then, when you have the time, write down as much as you can remember about the conversations in long fieldnotes. Later, you will have to sit down with these fieldnotes and try to make sense of all the information (see chapters 18 and 19).

Interview guide ( semistructured interview ). This is the primary type employed by social science qualitative researchers. The researcher creates an “interview guide” in advance, which she uses in every interview. In theory, every person interviewed is asked the same questions. In practice, every person interviewed is asked mostly the same topics but not always the same questions, as the whole point of a “guide” is that it guides the direction of the conversation but does not command it. The guide is typically between five and ten questions or question areas, sometimes with suggested follow-ups or prompts . For example, one question might be “What was it like growing up in Eastern Oregon?” with prompts such as “Did you live in a rural area? What kind of high school did you attend?” to help the conversation develop. These interviews generally take place in a quiet place (not a busy walkway during a festival) and are recorded. The recordings are transcribed, and those transcriptions then become the “data” that is analyzed (see chapters 18 and 19). The conventional length of one of these types of interviews is between one hour and two hours, optimally ninety minutes. Less than one hour doesn’t allow for much development of questions and thoughts, and two hours (or more) is a lot of time to ask someone to sit still and answer questions. If you have a lot of ground to cover, and the person is willing, I highly recommend two separate interview sessions, with the second session being slightly shorter than the first (e.g., ninety minutes the first day, sixty minutes the second). There are lots of good reasons for this, but the most compelling one is that this allows you to listen to the first day’s recording and catch anything interesting you might have missed in the moment and so develop follow-up questions that can probe further. This also allows the person being interviewed to have some time to think about the issues raised in the interview and go a little deeper with their answers.

Standardized questionnaire with open responses ( structured interview ). This is the type of interview a lot of people have in mind when they hear “interview”: a researcher comes to your door with a clipboard and proceeds to ask you a series of questions. These questions are all the same whoever answers the door; they are “standardized.” Both the wording and the exact order are important, as people’s responses may vary depending on how and when a question is asked. These are qualitative only in that the questions allow for “open-ended responses”: people can say whatever they want rather than select from a predetermined menu of responses. For example, a survey I collaborated on included this open-ended response question: “How does class affect one’s career success in sociology?” Some of the answers were simply one word long (e.g., “debt”), and others were long statements with stories and personal anecdotes. It is possible to be surprised by the responses. Although it’s a stretch to call this kind of questioning a conversation, it does allow the person answering the question some degree of freedom in how they answer.

Survey questionnaire with closed responses (not an interview!). Standardized survey questions with specific answer options (e.g., closed responses) are not really interviews at all, and they do not generate qualitative data. For example, if we included five options for the question “How does class affect one’s career success in sociology?”—(1) debt, (2) social networks, (3) alienation, (4) family doesn’t understand, (5) type of grad program—we leave no room for surprises at all. Instead, we would most likely look at patterns around these responses, thinking quantitatively rather than qualitatively (e.g., using regression analysis techniques, we might find that working-class sociologists were twice as likely to bring up alienation). It can sometimes be confusing for new students because the very same survey can include both closed-ended and open-ended questions. The key is to think about how these will be analyzed and to what level surprises are possible. If your plan is to turn all responses into a number and make predictions about correlations and relationships, you are no longer conducting qualitative research. This is true even if you are conducting this survey face-to-face with a real live human. Closed-response questions are not conversations of any kind, purposeful or not.

In summary, the semistructured interview guide approach is the predominant form of interviewing for social science qualitative researchers because it allows a high degree of freedom of responses from those interviewed (thus allowing for novel discoveries) while still maintaining some connection to a research question area or topic of interest. The rest of the chapter assumes the employment of this form.

Creating an Interview Guide

Your interview guide is the instrument used to bridge your research question(s) and what the people you are interviewing want to tell you. Unlike a standardized questionnaire, the questions actually asked do not need to be exactly what you have written down in your guide. The guide is meant to create space for those you are interviewing to talk about the phenomenon of interest, but sometimes you are not even sure what that phenomenon is until you start asking questions. A priority in creating an interview guide is to ensure it offers space. One of the worst mistakes is to create questions that are so specific that the person answering them will not stray. Relatedly, questions that sound “academic” will shut down a lot of respondents. A good interview guide invites respondents to talk about what is important to them, not feel like they are performing or being evaluated by you.

Good interview questions should not sound like your “research question” at all. For example, let’s say your research question is “How do patriarchal assumptions influence men’s understanding of climate change and responses to climate change?” It would be worse than unhelpful to ask a respondent, “How do your assumptions about the role of men affect your understanding of climate change?” You need to unpack this into manageable nuggets that pull your respondent into the area of interest without leading him anywhere. You could start by asking him what he thinks about climate change in general. Or, even better, whether he has any concerns about heatwaves or increased tornadoes or polar icecaps melting. Once he starts talking about that, you can ask follow-up questions that bring in issues around gendered roles, perhaps asking if he is married (to a woman) and whether his wife shares his thoughts and, if not, how they negotiate that difference. The fact is, you won’t really know the right questions to ask until he starts talking.

There are several distinct types of questions that can be used in your interview guide, either as main questions or as follow-up probes. If you remember that the point is to leave space for the respondent, you will craft a much more effective interview guide! You will also want to think about the place of time in both the questions themselves (past, present, future orientations) and the sequencing of the questions.

Researcher Note

Suggestion : As you read the next three sections (types of questions, temporality, question sequence), have in mind a particular research question, and try to draft questions and sequence them in a way that opens space for a discussion that helps you answer your research question.

Type of Questions

Experience and behavior questions ask about what a respondent does regularly (their behavior) or has done (their experience). These are relatively easy questions for people to answer because they appear more “factual” and less subjective. This makes them good opening questions. For the study on climate change above, you might ask, “Have you ever experienced an unusual weather event? What happened?” Or “You said you work outside? What is a typical summer workday like for you? How do you protect yourself from the heat?”

Opinion and values questions , in contrast, ask questions that get inside the minds of those you are interviewing. “Do you think climate change is real? Who or what is responsible for it?” are two such questions. Note that you don’t have to literally ask, “What is your opinion of X?” but you can find a way to ask the specific question relevant to the conversation you are having. These questions are a bit trickier to ask because the answers you get may depend in part on how your respondent perceives you and whether they want to please you or not. We’ve talked a fair amount about being reflective. Here is another place where this comes into play. You need to be aware of the effect your presence might have on the answers you are receiving and adjust accordingly. If you are a woman who is perceived as liberal asking a man who identifies as conservative about climate change, there is a lot of subtext that can be going on in the interview. There is no one right way to resolve this, but you must at least be aware of it.

Feeling questions are questions that ask respondents to draw on their emotional responses. It’s pretty common for academic researchers to forget that we have bodies and emotions, but people’s understandings of the world often operate at this affective level, sometimes unconsciously or barely consciously. It is a good idea to include questions that leave space for respondents to remember, imagine, or relive emotional responses to particular phenomena. “What was it like when you heard your cousin’s house burned down in that wildfire?” doesn’t explicitly use any emotion words, but it allows your respondent to remember what was probably a pretty emotional day. And if they respond emotionally neutral, that is pretty interesting data too. Note that asking someone “How do you feel about X” is not always going to evoke an emotional response, as they might simply turn around and respond with “I think that…” It is better to craft a question that actually pushes the respondent into the affective category. This might be a specific follow-up to an experience and behavior question —for example, “You just told me about your daily routine during the summer heat. Do you worry it is going to get worse?” or “Have you ever been afraid it will be too hot to get your work accomplished?”

Knowledge questions ask respondents what they actually know about something factual. We have to be careful when we ask these types of questions so that respondents do not feel like we are evaluating them (which would shut them down), but, for example, it is helpful to know when you are having a conversation about climate change that your respondent does in fact know that unusual weather events have increased and that these have been attributed to climate change! Asking these questions can set the stage for deeper questions and can ensure that the conversation makes the same kind of sense to both participants. For example, a conversation about political polarization can be put back on track once you realize that the respondent doesn’t really have a clear understanding that there are two parties in the US. Instead of asking a series of questions about Republicans and Democrats, you might shift your questions to talk more generally about political disagreements (e.g., “people against abortion”). And sometimes what you do want to know is the level of knowledge about a particular program or event (e.g., “Are you aware you can discharge your student loans through the Public Service Loan Forgiveness program?”).

Sensory questions call on all senses of the respondent to capture deeper responses. These are particularly helpful in sparking memory. “Think back to your childhood in Eastern Oregon. Describe the smells, the sounds…” Or you could use these questions to help a person access the full experience of a setting they customarily inhabit: “When you walk through the doors to your office building, what do you see? Hear? Smell?” As with feeling questions , these questions often supplement experience and behavior questions . They are another way of allowing your respondent to report fully and deeply rather than remain on the surface.

Creative questions employ illustrative examples, suggested scenarios, or simulations to get respondents to think more deeply about an issue, topic, or experience. There are many options here. In The Trouble with Passion , Erin Cech ( 2021 ) provides a scenario in which “Joe” is trying to decide whether to stay at his decent but boring computer job or follow his passion by opening a restaurant. She asks respondents, “What should Joe do?” Their answers illuminate the attraction of “passion” in job selection. In my own work, I have used a news story about an upwardly mobile young man who no longer has time to see his mother and sisters to probe respondents’ feelings about the costs of social mobility. Jessi Streib and Betsy Leondar-Wright have used single-page cartoon “scenes” to elicit evaluations of potential racial discrimination, sexual harassment, and classism. Barbara Sutton ( 2010 ) has employed lists of words (“strong,” “mother,” “victim”) on notecards she fans out and asks her female respondents to select and discuss.

Background/Demographic Questions

You most definitely will want to know more about the person you are interviewing in terms of conventional demographic information, such as age, race, gender identity, occupation, and educational attainment. These are not questions that normally open up inquiry. [1] For this reason, my practice has been to include a separate “demographic questionnaire” sheet that I ask each respondent to fill out at the conclusion of the interview. Only include those aspects that are relevant to your study. For example, if you are not exploring religion or religious affiliation, do not include questions about a person’s religion on the demographic sheet. See the example provided at the end of this chapter.

Temporality

Any type of question can have a past, present, or future orientation. For example, if you are asking a behavior question about workplace routine, you might ask the respondent to talk about past work, present work, and ideal (future) work. Similarly, if you want to understand how people cope with natural disasters, you might ask your respondent how they felt then during the wildfire and now in retrospect and whether and to what extent they have concerns for future wildfire disasters. It’s a relatively simple suggestion—don’t forget to ask about past, present, and future—but it can have a big impact on the quality of the responses you receive.

Question Sequence

Having a list of good questions or good question areas is not enough to make a good interview guide. You will want to pay attention to the order in which you ask your questions. Even though any one respondent can derail this order (perhaps by jumping to answer a question you haven’t yet asked), a good advance plan is always helpful. When thinking about sequence, remember that your goal is to get your respondent to open up to you and to say things that might surprise you. To establish rapport, it is best to start with nonthreatening questions. Asking about the present is often the safest place to begin, followed by the past (they have to know you a little bit to get there), and lastly, the future (talking about hopes and fears requires the most rapport). To allow for surprises, it is best to move from very general questions to more particular questions only later in the interview. This ensures that respondents have the freedom to bring up the topics that are relevant to them rather than feel like they are constrained to answer you narrowly. For example, refrain from asking about particular emotions until these have come up previously—don’t lead with them. Often, your more particular questions will emerge only during the course of the interview, tailored to what is emerging in conversation.

Once you have a set of questions, read through them aloud and imagine you are being asked the same questions. Does the set of questions have a natural flow? Would you be willing to answer the very first question to a total stranger? Does your sequence establish facts and experiences before moving on to opinions and values? Did you include prefatory statements, where necessary; transitions; and other announcements? These can be as simple as “Hey, we talked a lot about your experiences as a barista while in college.… Now I am turning to something completely different: how you managed friendships in college.” That is an abrupt transition, but it has been softened by your acknowledgment of that.

Probes and Flexibility

Once you have the interview guide, you will also want to leave room for probes and follow-up questions. As in the sample probe included here, you can write out the obvious probes and follow-up questions in advance. You might not need them, as your respondent might anticipate them and include full responses to the original question. Or you might need to tailor them to how your respondent answered the question. Some common probes and follow-up questions include asking for more details (When did that happen? Who else was there?), asking for elaboration (Could you say more about that?), asking for clarification (Does that mean what I think it means or something else? I understand what you mean, but someone else reading the transcript might not), and asking for contrast or comparison (How did this experience compare with last year’s event?). “Probing is a skill that comes from knowing what to look for in the interview, listening carefully to what is being said and what is not said, and being sensitive to the feedback needs of the person being interviewed” ( Patton 2002:374 ). It takes work! And energy. I and many other interviewers I know report feeling emotionally and even physically drained after conducting an interview. You are tasked with active listening and rearranging your interview guide as needed on the fly. If you only ask the questions written down in your interview guide with no deviations, you are doing it wrong. [2]

The Final Question

Every interview guide should include a very open-ended final question that allows for the respondent to say whatever it is they have been dying to tell you but you’ve forgotten to ask. About half the time they are tired too and will tell you they have nothing else to say. But incredibly, some of the most honest and complete responses take place here, at the end of a long interview. You have to realize that the person being interviewed is often discovering things about themselves as they talk to you and that this process of discovery can lead to new insights for them. Making space at the end is therefore crucial. Be sure you convey that you actually do want them to tell you more, that the offer of “anything else?” is not read as an empty convention where the polite response is no. Here is where you can pull from that active listening and tailor the final question to the particular person. For example, “I’ve asked you a lot of questions about what it was like to live through that wildfire. I’m wondering if there is anything I’ve forgotten to ask, especially because I haven’t had that experience myself” is a much more inviting final question than “Great. Anything you want to add?” It’s also helpful to convey to the person that you have the time to listen to their full answer, even if the allotted time is at the end. After all, there are no more questions to ask, so the respondent knows exactly how much time is left. Do them the courtesy of listening to them!

Conducting the Interview

Once you have your interview guide, you are on your way to conducting your first interview. I always practice my interview guide with a friend or family member. I do this even when the questions don’t make perfect sense for them, as it still helps me realize which questions make no sense, are poorly worded (too academic), or don’t follow sequentially. I also practice the routine I will use for interviewing, which goes something like this:

- Introduce myself and reintroduce the study

- Provide consent form and ask them to sign and retain/return copy

- Ask if they have any questions about the study before we begin

- Ask if I can begin recording

- Ask questions (from interview guide)

- Turn off the recording device

- Ask if they are willing to fill out my demographic questionnaire

- Collect questionnaire and, without looking at the answers, place in same folder as signed consent form

- Thank them and depart

A note on remote interviewing: Interviews have traditionally been conducted face-to-face in a private or quiet public setting. You don’t want a lot of background noise, as this will make transcriptions difficult. During the recent global pandemic, many interviewers, myself included, learned the benefits of interviewing remotely. Although face-to-face is still preferable for many reasons, Zoom interviewing is not a bad alternative, and it does allow more interviews across great distances. Zoom also includes automatic transcription, which significantly cuts down on the time it normally takes to convert our conversations into “data” to be analyzed. These automatic transcriptions are not perfect, however, and you will still need to listen to the recording and clarify and clean up the transcription. Nor do automatic transcriptions include notations of body language or change of tone, which you may want to include. When interviewing remotely, you will want to collect the consent form before you meet: ask them to read, sign, and return it as an email attachment. I think it is better to ask for the demographic questionnaire after the interview, but because some respondents may never return it then, it is probably best to ask for this at the same time as the consent form, in advance of the interview.

What should you bring to the interview? I would recommend bringing two copies of the consent form (one for you and one for the respondent), a demographic questionnaire, a manila folder in which to place the signed consent form and filled-out demographic questionnaire, a printed copy of your interview guide (I print with three-inch right margins so I can jot down notes on the page next to relevant questions), a pen, a recording device, and water.

After the interview, you will want to secure the signed consent form in a locked filing cabinet (if in print) or a password-protected folder on your computer. Using Excel or a similar program that allows tables/spreadsheets, create an identifying number for your interview that links to the consent form without using the name of your respondent. For example, let’s say that I conduct interviews with US politicians, and the first person I meet with is George W. Bush. I will assign the transcription the number “INT#001” and add it to the signed consent form. [3] The signed consent form goes into a locked filing cabinet, and I never use the name “George W. Bush” again. I take the information from the demographic sheet, open my Excel spreadsheet, and add the relevant information in separate columns for the row INT#001: White, male, Republican. When I interview Bill Clinton as my second interview, I include a second row: INT#002: White, male, Democrat. And so on. The only link to the actual name of the respondent and this information is the fact that the consent form (unavailable to anyone but me) has stamped on it the interview number.

Many students get very nervous before their first interview. Actually, many of us are always nervous before the interview! But do not worry—this is normal, and it does pass. Chances are, you will be pleasantly surprised at how comfortable it begins to feel. These “purposeful conversations” are often a delight for both participants. This is not to say that sometimes things go wrong. I often have my students practice several “bad scenarios” (e.g., a respondent that you cannot get to open up; a respondent who is too talkative and dominates the conversation, steering it away from the topics you are interested in; emotions that completely take over; or shocking disclosures you are ill-prepared to handle), but most of the time, things go quite well. Be prepared for the unexpected, but know that the reason interviews are so popular as a technique of data collection is that they are usually richly rewarding for both participants.

One thing that I stress to my methods students and remind myself about is that interviews are still conversations between people. If there’s something you might feel uncomfortable asking someone about in a “normal” conversation, you will likely also feel a bit of discomfort asking it in an interview. Maybe more importantly, your respondent may feel uncomfortable. Social research—especially about inequality—can be uncomfortable. And it’s easy to slip into an abstract, intellectualized, or removed perspective as an interviewer. This is one reason trying out interview questions is important. Another is that sometimes the question sounds good in your head but doesn’t work as well out loud in practice. I learned this the hard way when a respondent asked me how I would answer the question I had just posed, and I realized that not only did I not really know how I would answer it, but I also wasn’t quite as sure I knew what I was asking as I had thought.

—Elizabeth M. Lee, Associate Professor of Sociology at Saint Joseph’s University, author of Class and Campus Life , and co-author of Geographies of Campus Inequality

How Many Interviews?

Your research design has included a targeted number of interviews and a recruitment plan (see chapter 5). Follow your plan, but remember that “ saturation ” is your goal. You interview as many people as you can until you reach a point at which you are no longer surprised by what they tell you. This means not that no one after your first twenty interviews will have surprising, interesting stories to tell you but rather that the picture you are forming about the phenomenon of interest to you from a research perspective has come into focus, and none of the interviews are substantially refocusing that picture. That is when you should stop collecting interviews. Note that to know when you have reached this, you will need to read your transcripts as you go. More about this in chapters 18 and 19.

Your Final Product: The Ideal Interview Transcript

A good interview transcript will demonstrate a subtly controlled conversation by the skillful interviewer. In general, you want to see replies that are about one paragraph long, not short sentences and not running on for several pages. Although it is sometimes necessary to follow respondents down tangents, it is also often necessary to pull them back to the questions that form the basis of your research study. This is not really a free conversation, although it may feel like that to the person you are interviewing.

Final Tips from an Interview Master

Annette Lareau is arguably one of the masters of the trade. In Listening to People , she provides several guidelines for good interviews and then offers a detailed example of an interview gone wrong and how it could be addressed (please see the “Further Readings” at the end of this chapter). Here is an abbreviated version of her set of guidelines: (1) interview respondents who are experts on the subjects of most interest to you (as a corollary, don’t ask people about things they don’t know); (2) listen carefully and talk as little as possible; (3) keep in mind what you want to know and why you want to know it; (4) be a proactive interviewer (subtly guide the conversation); (5) assure respondents that there aren’t any right or wrong answers; (6) use the respondent’s own words to probe further (this both allows you to accurately identify what you heard and pushes the respondent to explain further); (7) reuse effective probes (don’t reinvent the wheel as you go—if repeating the words back works, do it again and again); (8) focus on learning the subjective meanings that events or experiences have for a respondent; (9) don’t be afraid to ask a question that draws on your own knowledge (unlike trial lawyers who are trained never to ask a question for which they don’t already know the answer, sometimes it’s worth it to ask risky questions based on your hypotheses or just plain hunches); (10) keep thinking while you are listening (so difficult…and important); (11) return to a theme raised by a respondent if you want further information; (12) be mindful of power inequalities (and never ever coerce a respondent to continue the interview if they want out); (13) take control with overly talkative respondents; (14) expect overly succinct responses, and develop strategies for probing further; (15) balance digging deep and moving on; (16) develop a plan to deflect questions (e.g., let them know you are happy to answer any questions at the end of the interview, but you don’t want to take time away from them now); and at the end, (17) check to see whether you have asked all your questions. You don’t always have to ask everyone the same set of questions, but if there is a big area you have forgotten to cover, now is the time to recover ( Lareau 2021:93–103 ).

Sample: Demographic Questionnaire

ASA Taskforce on First-Generation and Working-Class Persons in Sociology – Class Effects on Career Success

Supplementary Demographic Questionnaire

Thank you for your participation in this interview project. We would like to collect a few pieces of key demographic information from you to supplement our analyses. Your answers to these questions will be kept confidential and stored by ID number. All of your responses here are entirely voluntary!

What best captures your race/ethnicity? (please check any/all that apply)

- White (Non Hispanic/Latina/o/x)

- Black or African American

- Hispanic, Latino/a/x of Spanish

- Asian or Asian American

- American Indian or Alaska Native

- Middle Eastern or North African

- Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander

- Other : (Please write in: ________________)

What is your current position?

- Grad Student

- Full Professor

Please check any and all of the following that apply to you:

- I identify as a working-class academic

- I was the first in my family to graduate from college

- I grew up poor

What best reflects your gender?

- Transgender female/Transgender woman

- Transgender male/Transgender man

- Gender queer/ Gender nonconforming

Anything else you would like us to know about you?

Example: Interview Guide

In this example, follow-up prompts are italicized. Note the sequence of questions. That second question often elicits an entire life history , answering several later questions in advance.

Introduction Script/Question

Thank you for participating in our survey of ASA members who identify as first-generation or working-class. As you may have heard, ASA has sponsored a taskforce on first-generation and working-class persons in sociology and we are interested in hearing from those who so identify. Your participation in this interview will help advance our knowledge in this area.

- The first thing we would like to as you is why you have volunteered to be part of this study? What does it mean to you be first-gen or working class? Why were you willing to be interviewed?

- How did you decide to become a sociologist?

- Can you tell me a little bit about where you grew up? ( prompts: what did your parent(s) do for a living? What kind of high school did you attend?)

- Has this identity been salient to your experience? (how? How much?)

- How welcoming was your grad program? Your first academic employer?

- Why did you decide to pursue sociology at the graduate level?

- Did you experience culture shock in college? In graduate school?

- Has your FGWC status shaped how you’ve thought about where you went to school? debt? etc?

- Were you mentored? How did this work (not work)? How might it?

- What did you consider when deciding where to go to grad school? Where to apply for your first position?

- What, to you, is a mark of career success? Have you achieved that success? What has helped or hindered your pursuit of success?

- Do you think sociology, as a field, cares about prestige?

- Let’s talk a little bit about intersectionality. How does being first-gen/working class work alongside other identities that are important to you?

- What do your friends and family think about your career? Have you had any difficulty relating to family members or past friends since becoming highly educated?

- Do you have any debt from college/grad school? Are you concerned about this? Could you explain more about how you paid for college/grad school? (here, include assistance from family, fellowships, scholarships, etc.)

- (You’ve mentioned issues or obstacles you had because of your background.) What could have helped? Or, who or what did? Can you think of fortuitous moments in your career?

- Do you have any regrets about the path you took?

- Is there anything else you would like to add? Anything that the Taskforce should take note of, that we did not ask you about here?

Further Readings

Britten, Nicky. 1995. “Qualitative Interviews in Medical Research.” BMJ: British Medical Journal 31(6999):251–253. A good basic overview of interviewing particularly useful for students of public health and medical research generally.

Corbin, Juliet, and Janice M. Morse. 2003. “The Unstructured Interactive Interview: Issues of Reciprocity and Risks When Dealing with Sensitive Topics.” Qualitative Inquiry 9(3):335–354. Weighs the potential benefits and harms of conducting interviews on topics that may cause emotional distress. Argues that the researcher’s skills and code of ethics should ensure that the interviewing process provides more of a benefit to both participant and researcher than a harm to the former.

Gerson, Kathleen, and Sarah Damaske. 2020. The Science and Art of Interviewing . New York: Oxford University Press. A useful guidebook/textbook for both undergraduates and graduate students, written by sociologists.

Kvale, Steiner. 2007. Doing Interviews . London: SAGE. An easy-to-follow guide to conducting and analyzing interviews by psychologists.

Lamont, Michèle, and Ann Swidler. 2014. “Methodological Pluralism and the Possibilities and Limits of Interviewing.” Qualitative Sociology 37(2):153–171. Written as a response to various debates surrounding the relative value of interview-based studies and ethnographic studies defending the particular strengths of interviewing. This is a must-read article for anyone seriously engaging in qualitative research!

Pugh, Allison J. 2013. “What Good Are Interviews for Thinking about Culture? Demystifying Interpretive Analysis.” American Journal of Cultural Sociology 1(1):42–68. Another defense of interviewing written against those who champion ethnographic methods as superior, particularly in the area of studying culture. A classic.

Rapley, Timothy John. 2001. “The ‘Artfulness’ of Open-Ended Interviewing: Some considerations in analyzing interviews.” Qualitative Research 1(3):303–323. Argues for the importance of “local context” of data production (the relationship built between interviewer and interviewee, for example) in properly analyzing interview data.

Weiss, Robert S. 1995. Learning from Strangers: The Art and Method of Qualitative Interview Studies . New York: Simon and Schuster. A classic and well-regarded textbook on interviewing. Because Weiss has extensive experience conducting surveys, he contrasts the qualitative interview with the survey questionnaire well; particularly useful for those trained in the latter.

- I say “normally” because how people understand their various identities can itself be an expansive topic of inquiry. Here, I am merely talking about collecting otherwise unexamined demographic data, similar to how we ask people to check boxes on surveys. ↵

- Again, this applies to “semistructured in-depth interviewing.” When conducting standardized questionnaires, you will want to ask each question exactly as written, without deviations! ↵

- I always include “INT” in the number because I sometimes have other kinds of data with their own numbering: FG#001 would mean the first focus group, for example. I also always include three-digit spaces, as this allows for up to 999 interviews (or, more realistically, allows for me to interview up to one hundred persons without having to reset my numbering system). ↵

A method of data collection in which the researcher asks the participant questions; the answers to these questions are often recorded and transcribed verbatim. There are many different kinds of interviews - see also semistructured interview , structured interview , and unstructured interview .