An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- CBE Life Sci Educ

- v.21(3); Fall 2022

Writing and Using Learning Objectives

Rebecca b. orr.

† Division of Academic Affairs, Collin College, Plano, TX 75074

Melissa M. Csikari

‡ HHMI Science Education, BioInteractive, Chevy Chase, MD 20815

Scott Freeman

§ Department of Biology, University of Washington, Seattle, WA 98195

Michael C. Rodriguez

∥ Educational Psychology, College of Education and Human Development, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN 55455

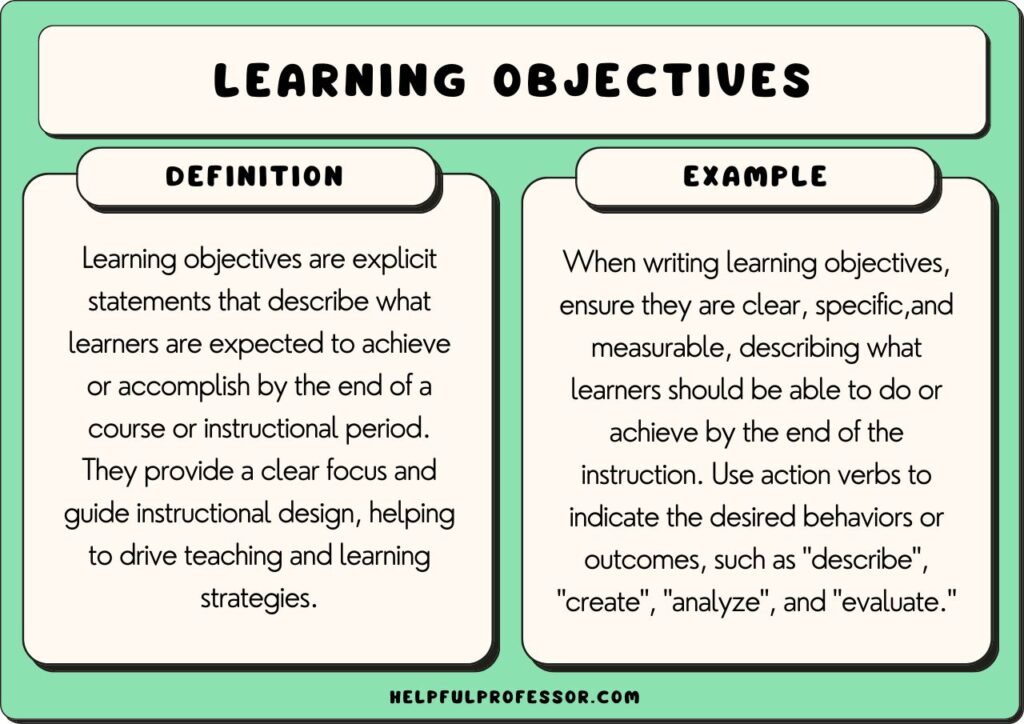

Learning objectives (LOs) are used to communicate the purpose of instruction. Done well, they convey the expectations that the instructor—and by extension, the academic field—has in terms of what students should know and be able to do after completing a course of study. As a result, they help students better understand course activities and increase student performance on assessments. LOs also serve as the foundation of course design, as they help structure classroom practices and define the focus of assessments. Understanding the research can improve and refine instructor and student use of LOs. This essay describes an online, evidence-based teaching guide published by CBE—Life Sciences Education ( LSE ) at http://lse.ascb.org/learning-objectives . The guide contains condensed summaries of key research findings organized by recommendations for writing and using LOs, summaries of and links to research articles and other resources, and actionable advice in the form of a checklist for instructors. In addition to describing key features of the guide, we also identify areas that warrant further empirical studies.

INTRODUCTION

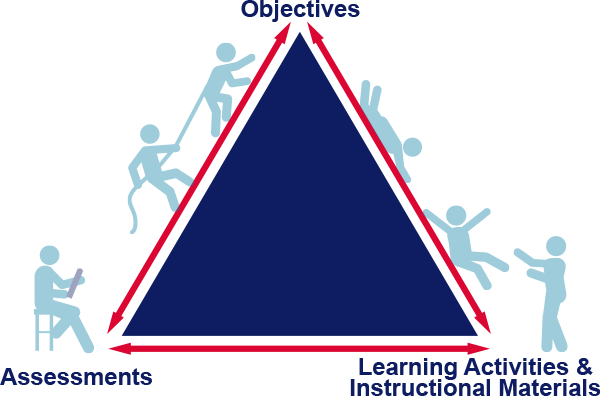

Learning objectives (LOs) are statements that communicate the purpose of instruction to students, other instructors, and an academic field ( Mager, 1997 ; Rodriguez and Albano, 2017 ). They form the basis for developing high-quality assessments for formative and summative purposes. Once LOs and assessments are established, instructional activities can help students master the material. Aligning LOs with assessments and instructional practice is the essence of backward course design ( Fink, 2003 ).

Many terms in the literature describe statements about learning expectations. The terms “course objectives,” “course goals,” “learning objectives,” “learning outcomes,” and “learning goals” are often used interchangeably, creating confusion for instructors and students. To clarify and standardize usage, the term “objective” is defined as a declarative statement that identifies what students are expected to know and do . At the same time, “outcome” refers to the results measured at the end of a unit, course, or program. It is helpful to think of LOs as a tool instructors use for describing intended outcomes, regardless of the process for achieving the outcome ( Mager, 1997 ). The term “goal” is less useful. Although it is often used to express more general expectations, there is no consistent usage in the literature.

In this guide, “learning objective” is defined as a statement that communicates the purpose of instruction using an action verb and describes the expected performance and conditions under which the performance should occur. Examples include:

- At the end of this lesson, students should be able to compare the processes of diffusion, osmosis, and facilitated diffusion, and provide biological examples that illustrate each process.

- At the end of this lesson, students should be able to predict the relative rates at which given ions and molecules will cross a plasma membrane in the absence of membrane protein and explain their reasoning.

In terms of content and complexity, LOs should scaffold professional practice, requirements for a program, and individual course goals by communicating the specific content areas and skills considered important by the academic field ( Rodriguez and Albano, 2017 ). They also promote course articulation by supporting consistency when courses are taught by multiple instructors and furnishing valuable information about course alignment among institutions. As a result, LOs should serve as the basis of unit or module, course, and program design and can be declared in a nested hierarchy of levels. For clarity, we describe a hierarchy of LOs in Table 1 .

Levels of LOs ( Rodriguez and Albano, 2017 )

| Type of LO | Scope and context | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Institutional | Broad, institution specific | |

| Programmatic | Broad, program specific | |

| Course level | Broad, course specific, and student centered | |

| Instructional | Specific and descriptive, module or lesson specific, and student focused |

a Hereafter, our use of the term “learning objectives” specifically refers to instructional LOs.

This article describes an evidence-based teaching guide that aggregates, summarizes, and provides actionable advice from research findings on LOs. It can be accessed at http://lse.ascb.org/learning-objectives . The guide has several features intended to help instructors: a landing page that indicates starting points ( Figure 1 ), syntheses of observations from the literature, summaries of and links to selected papers ( Figure 2 ), and an instructor checklist that details recommendations and points to consider. The focus of our guide is to provide recommendations based on the literature for instructors to use when creating, revising, and using instructional LOs in their courses. The Effective Construction section provides evidence-based guidelines for writing effective LOs. The Instructor Use section contains research summaries about using LOs as a foundational element for successful course design, summaries of the research that supports recommended practices for aligning LOs with assessment and classroom instruction, and direction from experts for engaging with colleagues in improving instructor practice with LOs. The Student Use section includes a discussion on how students use LOs and how instructor guidance can improve student use of LOs, along with evidence on the impact of LO use coupled with pretests, transparent teaching methods, and summaries of LO-driven student outcomes in terms of exam scores, depth of learning, and affect (e.g., perception of utility and self-regulated learning). Some of the questions and considerations that serve to organize the guide are highlighted in the following sections.

LO guide landing page, which provides readers with an overview of choice points.

Screenshots representing summaries of and links to selected papers.

WRITING EFFECTIVE INSTRUCTIONAL LEARNING OBJECTIVES

Writing LOs effectively is essential, as their wording should provide direction for developing instructional activities and guide the design of assessments. Effective LOs clearly communicate what students should know and be able to do and are written to be behavioral, measurable, and attainable ( Rodriguez and Albano, 2017 ). It is particularly important that each LO is written with enough information to ensure that other knowledgeable individuals can use the LO to measure a learner’s success and arrive at the same conclusions ( Mager, 1997 ). Clear, unambiguous wording encourages consistency across sections and optimizes student use of the stated LOs.

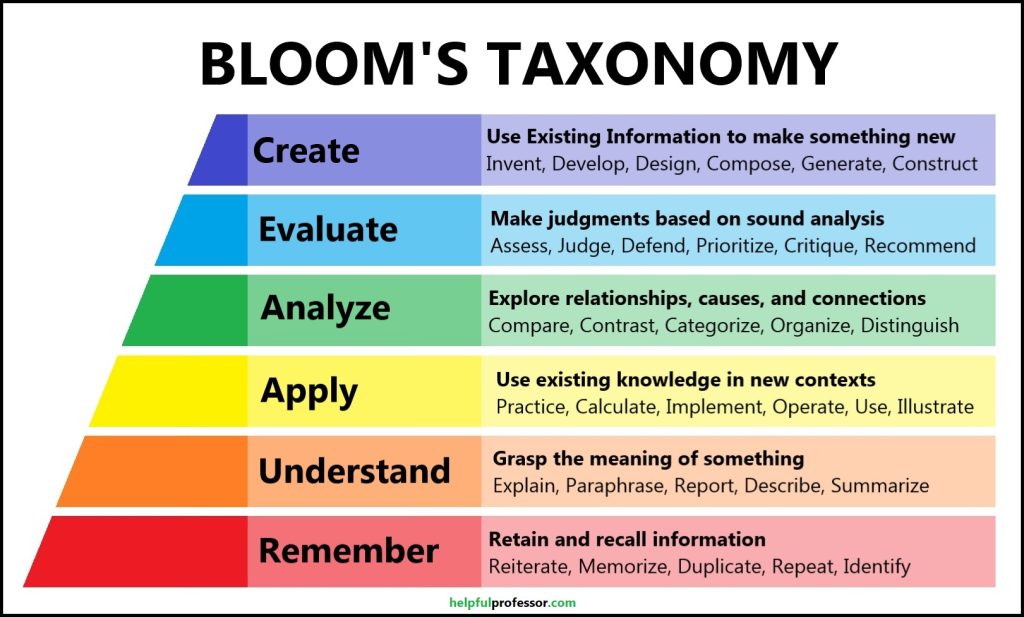

Effective LOs specify a visible performance—what students should be able to do with the content—and may also include conditions and the criteria for acceptable performance ( Mager, 1997 ). When constructing an LO, one should use an action verb to describe what students are expected to know and be able to do with the disciplinary knowledge and skills ( Figure 3 ). Bloom’s taxonomy of cognitive skills provides a useful framework for writing LOs that embody the intended complexity and the cognitive demands involved in mastering them ( Bloom, 1956 ; Anderson and Krathwohl, 2001 ). Assessment items and course activities can then be aligned with LOs using the Blooming Biology Tool described by Crowe et al. (2008) . However, LOs should not state the instructional method(s) planned to accomplish the objectives or be written so specifically as to be assessment tasks themselves ( Mager, 1997 ).

Components of an LO.

Our Instructor Checklist provides specific recommendations for writing LOs, along with a link to examples of measurable action verbs associated with Bloom’s taxonomy.

COURSE DESIGN: ALIGNING LEARNING OBJECTIVES WITH ASSESSMENT AND CLASSROOM INSTRUCTION

Course designs and redesigns built around clear and measurable LOs result in measurable benefits to students (e.g., Armbruster et al. , 2009 , and other citations in the Course and Curriculum Design and Outcomes section of this guide). LOs are established as the initial step in backward design ( McTighe and Wiggins, 2012 ). They provide a framework for instructors to 1) design assessments that furnish evidence on the degree of student mastery of knowledge and skills and 2) select teaching and learning activities that are aligned with objectives ( Mager, 1997 ; Rodriguez and Albano, 2017) . Figure 4 depicts depicts integrated course course design, emphasizing the dynamic and reciprocal associations among LOs, assessment, and teaching practice.

Components of integrated course design (after Fink, 2003 ).

Used in this way, LOs provide a structure for planning assessments and instruction while giving instructors the freedom to be creative and flexible ( Mager, 1997 ; Reynolds and Kearns, 2017 ). In essence, LOs respond to the question: “If you don’t know where you’re going, how will you know which road to take and how do you know when you get there?” ( Mager, 1997 , p. 14). When assessments are created, each assessment item or task must be specifically associated with at least one LO and measure student learning progress on that LO. The performance and conditions components of each LO should guide the type of assessment developed ( Mager, 1997 ). Data gathered from assessment results (feedback) can then inform future instruction. The Assessment section of our guide contains summaries of research reporting the results of aligning assessment with LOs and summaries of frameworks that associate assessment items with LOs.

The purpose of instruction is communicated to students most effectively when instructional activities are aligned with associated instructional and course-level LOs (e.g., Chasteen et al. , 2011 , and others within the Instructor Use section of this guide). The literature summarized in the Course and Curriculum Design section of the guide supports the hypothesis that student learning is strongly impacted by what instructors emphasize in the classroom. In the guide’s Student Buy-In and Metacognition section, we present strategies instructors have used to ensure that LOs are transparent and intentionally reinforced to students . When LOs are not reinforced in instruction, students may conclude that LOs are an administrative requirement rather than something developed for their benefit. The guide’s Instructor Checklist contains evidence-based suggestions for increasing student engagement through making LOs highly visible.

Using LOs as the foundation of course planning results in a more student-centered approach, shifting the focus from the content to be covered to the concepts and skills that the student should be able to demonstrate upon successfully completing the course (e.g., Reynolds and Kearns, 2017 , and others within the Active Learning section of this guide). Instead of designing memorization-driven courses that are “a mile wide and an inch deep,” instructors can use LOs to focus a course on the key concepts and skills that prepare students for future success in the field. Group problem solving, discussions, and other class activities that allow students to practice and demonstrate the competencies articulated in LOs can be prioritized over lectures that strive to cover all of the content. The guide’s Active Learning section contains a summary of the literature on the use of LOs to develop activities that promote student engagement, provide opportunities for students to practice performance, and allow instructors to gather feedback on learning progress. The evidence-based teaching guides on Group Work and Peer Instruction provide additional evidence and resources to support these efforts.

ENGAGING WITH COLLEAGUES TO IMPROVE LEARNING OBJECTIVES

Momsen et al. (2010) examined Bloom’s level of assessment items and course goals from 50 faculty in 77 introductory biology courses for majors. The authors found that 93% of the assessment items were rated low-level Bloom’s, and 69% of the 250 course goals submitted were rated low-level Bloom’s ( Momsen et al. , 2010 ). A recent survey of 38 instructors of biology for nonmajors found similar results. Heil et al. (unpublished data) reported that 74% of the instructors surveyed write their own LOs, and 95% share their LOs with their students ( Heil et al. , unpublished data ). The action verbs used in 66% of these LOs were low-level Bloom’s cognitive skills, assessing knowledge and comprehension ( Heil et al. , unpublished data ). Further, an analysis of 1390 LOs from three best-selling biology textbooks for nonscience majors found that 89% were rated Bloom’s cognitive skill level 1 or level 2. Vision & Change competencies, as articulated in the BioSkills Guide ( Clemmons et al. , 2020 ), were only present in 17.7% of instructors’ LOs and 7% of the textbook LOs ( Heil et al. , unpublished data ). These data suggest that, in introductory biology for both majors and nonmajors, most instructors emphasize lower-order cognitive skills that are not aligned with teaching frameworks.

Researchers have documented effective strategies to improve instructors’ writing and use of LOs. The guide’s Engaging with Colleagues section contains summaries demonstrating that instructor engagement with the scholarship of teaching and learning can improve through professional development in collaborative groups—instructors can benefit by engaging in a collegial community of practice as they implement changes in their teaching practices (e.g., Richlin and Cox, 2004 , and others within the Engaging with Colleagues section of the guide). Collaboration among institutions can create common course-level LOs that promote horizontal and vertical course alignment, which can streamline articulation agreements and transfer pathways between institutions ( Kiser et al. , 2022 ). Departmental efforts to map LOs across program curricula can close gaps in programmatic efforts to convey field-expected criteria and develop student skills throughout a program ( Ezell et al. , 2019 ). The guide contains summaries of research-based recommendations that encourage departmental support for course redesign efforts (e.g., Pepper et al. , 2012 , and others within the Engaging with Colleagues section of the guide).

HOW DO LEARNING OBJECTIVES IMPACT STUDENTS?

When instructors publish well-written LOs aligned with classroom instruction and assessments, they establish clear goalposts for students ( Mager, 1997 ). Using LOs to guide their studies, students should no longer have to ask “Do we have to know …?” or “Will this be on the test?” The Student Use section of the guide contains summaries of research on the impact of LOs from the student perspective.

USING LEARNING OBJECTIVES TO GUIDE STUDENT LEARNING

Researchers have shown that students support the use of LOs to design class activities and assessments. In the Guiding Learning section of the guide, we present evidence documenting how students use LOs and how instructors can train students to use them more effectively ( Brooks et al. , 2014 , and other citations within this section of the guide). However, several questions remain about the impact of LOs on students. For example, using LOs may improve students’ ability to self-regulate, which in turn may be particularly helpful in supporting the success of underprepared students ( Simon and Taylor, 2009 ; Osueke et al. , 2018 ). But this hypothesis remains untested.

There is evidence that transparency in course design improves the academic confidence and retention of underserved students ( Winkelmes et al. , 2016 ), and LOs make course expectations transparent to students. LOs are also reported to help students organize their time and effort and give students, particularly those from traditionally underserved groups, a better idea of areas in which they need help ( Minbiole, 2016 ). Additionally, LOs facilitate the construction of highly structured courses by providing scaffolding for assessment and classroom instruction. Highly structured course design has been demonstrated to improve all students’ academic performance. It significantly reduces achievement gaps (difference in final grades on a 4.0 scale) between disadvantaged and nondisadvantaged students ( Haak et al. , 2011 ). However, much more evidence is needed on how LOs impact underprepared and/or underresourced students:

- Does the use of LOs lead to increased engagement with the content and/or instructor by underprepared and/or underserved students?

- Does LO use have a disproportionate and positive impact on the ability of underprepared and/or underresourced students to self-direct their learning?

- Is there a significant impact on underserved students’ academic performance and persistence with transparent LOs in place?

In general, how can instructors help students realize the benefits of well-written LOs? Research indicates that many students never receive instruction on using LOs ( Osueke et al. , 2018 ). However, when students receive explicit instruction on LO use, they benefit ( Osueke et al. , 2018 ). Examples include teaching students how to turn LOs into questions and how to answer and use those questions for self-assessment ( Osueke et al. , 2018 ). Using LOs for self-assessment allows students to take advantage of retrieval practice, a strategy that has a positive effect on learning and memory by helping students identify what they have and have not learned ( Bjork and Bjork, 2011 ; Brame and Biel, 2015 ). Some students, however, may avoid assessment strategies that identify what they do not understand or know because they find difficulty uncomfortable ( Orr and Foster, 2013 ; Dye and Stanton, 2017 ).

Brooks et al. (2014) reported that about one-third of students surveyed indicated that they had underestimated the depth of learning required to pass an assessment on the stated LOs. Further, students may have difficulty understanding the scope or expectations of stated LOs until after learning the content. Research on how instructors should train students to use LOs has been limited, and many of these open questions remain:

- What are the best practices to help students use LOs in self-assessment strategies?

- How can instructors motivate students to go outside their comfort zones for learning and use LOs in self-assessment strategies?

- How can instructors help students better understand the performance, conditions, and criteria required by the LOs to demonstrate successful learning?

- How might this differ for learners at different institutions, where academic preparedness and/or readiness levels may vary greatly?

CAPITALIZING ON THE PRETEST EFFECT

The guide’s Pretesting section contains research findings building on the pretesting effect reported by Little and Bjork (2011) . Pretesting with questions based on LOs has been shown to better communicate course expectations to students, increase student motivation and morale by making learning progress more visible, and improve retention of information as measured by final test scores ( Beckman, 2008 ; Sana et al. , 2020 ). Operationalizing LOs as pretest questions may serve as an effective, evidence-based model for students to self-assess and prepare for assessment. The research supporting this strategy is very limited, however, prompting the following questions:

- How broadly applicable—in terms of discipline and course setting—is the benefit of converting LOs to pretest questions?

- Is the benefit of operationalizing LOs to create pretests sustained when converting higher-level Bloom’s LOs into pretest questions?

- Does the practice of using LOs to create pretest questions narrow students’ focus such that the breadth/scope of their learning is overly limited/restricted? This is particularly concerning if students underestimate the depth of learning required by the stated LOs ( Brooks et al. , 2014 ).

- Could this practice help instructors teach students to use LOs to self-assess with greater confidence and persistence?

STUDENT OUTCOMES

The guide concludes with research summaries regarding the specific benefits to students associated with the use of LOs. Specifically, 1) alignment of LOs and assessment items is associated with higher exam scores (e.g., Armbruster et al. , 2009 , and others within the Outcomes section of the guide); 2) exam items designed to measure student mastery of LOs can support higher-level Bloom’s cognitive skills (e.g., Armbruster et al. , 2009 , and others within the Outcomes section of the guide); and 3) students adjust their learning approach based on course design and have been shown to employ a deeper approach to learning in courses in which assessment and class instruction are aligned with LOs ( Wang et al. , 2013 ).

CHALLENGES IN MEASURING THE IMPACT OF LEARNING OBJECTIVES

It is difficult to find literature in which researchers measured the impact of LOs alone on student performance due to their almost-necessary conflation with approaches to assessment and classroom practices. We argue that measuring the impact of LOs independently of changes in classroom instruction or assessment would be inadvisable, considering the role that LOs play in integrated course design ( Figure 4 ). Consistent with this view, the guide includes summaries of research findings on course redesigns that focus on creating or refining well-defined, well-written LOs; aligning assessment and classroom practice with the LOs; and evaluating student use and/or outcomes ( Armbruster et al. , 2009 ; Chasteen et al. , 2011 ). We urge instructors to use LOs from this integrated perspective.

CONCLUSIONS

We encourage instructors to use LOs as the basis for course design, align LOs with assessment and instruction, and promote student success by sharing their LOs and providing practice with how best to use them. Instructor skill in using LOs is not static and can be improved and refined with collaborative professional development efforts. Our teaching guide ends with an Instructor Checklist of actions instructors can take to optimize their use of LOs ( http://lse.ascb.org/learning-objectives/instructor-checklist ).

Acknowledgments

We thank Kristy Wilson for her guidance and support as consulting editor for this effort and Cynthia Brame and Adele Wolfson for their insightful feedback on this paper and the guide. This material is based upon work supported in part by the National Science Foundation under grant number DUE 201236 2. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors. They do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.

- Anderson, L. W., Krathwohl, D. R. (2001). A taxonomy for learning, teaching, and assessing: A revision of Bloom’s taxonomy of educational objectives (Complete ed.). New York, NY: Longman. [ Google Scholar ]

- Armbruster, P., Patel, M., Johnson, E., Weiss, M. (2009). Active learning and student-centered pedagogy improve student attitudes and performance in introductory biology . CBE—Life Sciences Education , 3 ( 8 ), 203–213. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Beckman, W. S. (2008). Pre-testing as a method of conveying learning objectives . Journal of Aviation/Aerospace Education & Research , 17 ( 2 ), 61–70. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bjork, E. L., Bjork, R. A. (2011). Making things hard on yourself, but in a good way: Creating desirable difficulties to enhance learning . In Gernsbacher, M. A., Pomerantz, J. (Eds.), Psychology and the real world: Essays illustrating fundamental contributions to society (2nd ed., pp. 59–68). New York, NY: Worth Publishers. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bloom, B. S. (1956). Taxonomy of educational objectives: The classification of educational goals by a committee of college and university examiners. Handbook I: Cognitive domain . New York, NY: David McKay. [ Google Scholar ]

- Brame, C. J., Biel, R. (2015). Test-enhanced learning: The potential for testing to promote greater learning in undergraduate science courses . CBE—Life Sciences Education , 14 , 1–12. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Brooks, S., Dobbins, K., Scott, J., Rawlinson, M., Norman, R. I. (2014). Learning about learning outcomes: The student perspective . Teaching in Higher Education , 19 ( 6 ), 721–733. [ Google Scholar ]

- Chasteen, S. V., Perkins, K. K., Beale, P. D., Pollock, S. J., Wieman, C. E. (2011). A thoughtful approach to instruction: Course transformation for the rest of us . Journal of College Science Teaching , 40 , 24–30. [ Google Scholar ]

- Clemmons, A. W., Timbrook, J., Herron, J. C., Crowe, A. J. (2020). BioSkills Guide: Development and national validation of a tool for interpreting the Vision and Change core competencies . CBE—Life Sciences Education , 19 ( 20 ), 1–19. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Crowe, A., Dirks, C., Wenderoth, M. P. (2008). Biology in Bloom: Implementing Bloom’s taxonomy to enhance student learning in biology . CBE—Life Sciences Education , 7 ( 4 ), 368–381. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Dye, K. M., Stanton, J. D. (2017). Metacognition in upper-division biology students: Awareness does not always lead to control . CBE—Life Sciences Education , 16 ( 2 ), 1–14. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ezell, J. D., Lending, D., Dillon, T. W., May, J., Hurney, C. A., Fulcher, K. H. (2019). Developing measurable cross-departmental learning objectives for requirements elicitation in an information systems curriculum . Journal of Information Systems Education , 30 ( 1 ), 27–41. [ Google Scholar ]

- Fink, L. D. (2003). A self-directed guide to designing courses for significant learning . San Francisco, CA: Dee Fink & Associates. https://www.deefinkandassociates.com/GuidetoCourseDesignAug05.pdf [ Google Scholar ]

- Haak, D. C., HilleRisLambers, J., Pitre, E., Freeman, S. (2011). Increased structure and active learning reduce the achievement gap in introductory biology . Science , 332 ( 6034 ), 1213–1216. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Heil, H., Gormally, C., Brickman, P. (in press). Low-level learning and expectations for non-science majors . Journal of College Science Teaching . [ Google Scholar ]

- Kiser, S., Kayes, L. J., Baumgartner, E., Kruchten, A., Stavrianeas, S. (2022). Statewide curricular alignment & learning outcomes for introductory biology: Using Vision & Change as a vehicle for collaboration . American Biology Teacher , 84 ( 3 ), 130–136. [ Google Scholar ]

- Little, J. L., Bjork, E. L. (2011). Pretesting with multiple-choice questions facilitates learning . Cognitive Science , 33 , 294–299. [ Google Scholar ]

- Mager, R. F. (1962). Preparing instructional objectives: A critical tool in the development of effective instruction (1st ed.). Palo Alto, CA: Fearon Publishers. [ Google Scholar ]

- Mager, R. F. (1997). Preparing instructional objectives: A critical tool in the development of effective instruction (3rd ed.). Atlanta, GA: Center for Effective Performance. [ Google Scholar ]

- McTighe, J., Wiggins, G. (2012, March). Understanding by design framework . Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development. [ Google Scholar ]

- Minbiole, J. (2016). Improving course coherence & assessment rigor: “Understanding by Design” in a nonmajors biology course . American Biology Teacher , 78 ( 6 ), 463–470. [ Google Scholar ]

- Momsen, J. L., Long, T. M., Wyse, S. A., Ebert-May, D. (2010). Just the facts? Introductory undergraduate biology courses focus on low-level cognitive skills . CBE—Life Sciences Education , 9 ( 4 ), 435–440. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Orr, R., Foster, S. (2013). Increasing student success using online quizzing in introductory (majors) biology . CBE—Life Sciences Education , 12 ( 3 ), 509–514. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Osueke, B., Mekonnen, B., Stanton, J. D. (2018). How undergraduate science students use learning objectives to study . Journal of Microbiology & Biology Education , 19 ( 2 ), 1–8. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Pepper, R. E., Chasteen, S. V., Pollock, S. J., Perkins, K. K. (2012). Facilitating faculty conversations: Development of consensus learning goals . AIP Conference Proceedings , 1413 , 291. [ Google Scholar ]

- Reynolds, H. L., Kearns, K. D. (2017). A planning tool for incorporating backward design, active learning, and authentic assessment in the college classroom . College Teaching , 65 ( 1 ), 17–27. [ Google Scholar ]

- Richlin, L., Cox, M. D. (2004). Developing scholarly teaching and the scholarship of teaching and learning through faculty learning communities . New Directions for Teaching and Learning , 97 , 127–135. [ Google Scholar ]

- Rodriguez, M. C., Albano, A. D. (2017). The college instructor’s guide to writing test items: Measuring student learning . New York, NY: Routledge. [ Google Scholar ]

- Sana, F., Forrin, N. D., Sharma, M., Dubljevic, T., Ho, P., Jalil, E., Kim, J. A. (2020). Optimizing the efficacy of learning objectives through pretests . CBE—Life Sciences Education , 19 ( 3 ), 1–10. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Simon, B., Taylor, J. (2009). What is the value of course-specific learning goals? Journal of College Science Teaching , 39 , 52–57. [ Google Scholar ]

- Wang, X., Su, Y., Cheung, S., Wong, E., Kwong, T. (2013). An exploration of Biggs’ constructive alignment in course design and its impact on students’ learning approaches . Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education , 38 , 477–491. [ Google Scholar ]

- Winkelmes, M., Bernacki, M., Butler, J., Zochowski, M., Golanics, J., Weevil, K. H. (2016). A teaching intervention that increases underserved college students’ success . Peer Review , 18 ( 1/2 ), 31–36. [ Google Scholar ]

- Learning Objectives

What is a Learning Objective?

Bloom (1956) suggests a six-stage hierarchy of cognitive competencies :

- Knowledge - Students can collect and restate information.

- Comprehension - Students can interpret and understand information.

- Application - Students can apply information to solve problems.

- Analysis - Students can organize and analyze information.

- Synthesis - Students can create information from information.

- Evaluation - Students can compare and assess information and ideas.

In an update to Bloom, Anderson and Krathwohl (2001) argue that students should be able to:

Undergraduate research experiences that engage students in the scientific method require and develop skills that can be mapped to Bloom's taxonomy and require students to do the tasks that Anderson and Krathwohl suggest they should be able to. And rather than offering isolated experiences with each of the steps of the scientific method, their relationships to one another become transparent, furthering one's understanding of what it means to "do science." Before going headfirst into an undergraduate research experience, you want to consider how directly and deeply you want students engaged in each step of the research process. This will help you determine where you place an undergraduate research experience in your curriculum or course, or if you do undergraduate research outside of the classroom instead (perhaps as part of a summer research experience).

As an example, if your key learning objectives are related to synthesis and evaluation, you may want the culminating project in your class to be a research paper and, if time is limited, you may want to supply students with the background literature and data for the project rather ask them to collect it themselves. If you have an opportunity to supervise the project as an independent study, though, you may have time to work on each of the six competencies more intensely and can involve your student just as seriously in tasks like reviewing the literature and collecting data as in evaluating evidence.

Krathwohl et al (1964) suggests a hierarchy of affective competencies , and you may consider forming some affective learning objectives as well. These competencies are:

- Receiving - Students can notice and tolerate ideas.

- Responding - Students can respond to ideas by investing in them in some way.

- Valuing - Students can demonstrate to others that they value some ideas.

- Organizing - Students can connect that value to existing ones.

- Characterizing - Students' actions are consistent with the internalized values.

Developing Learning and Content Objectives

Here are some tips for writing cognitive learning objectives from the Higher Education Academy.

« Previous Page Next Page »

- Campus Living Laboratory

- ConcepTests

- Conceptual Models

- Cooperative Learning

- Earth History Approach

- Experience-Based Environmental Projects

- First Day of Class

- Gallery Walks

- Indoor Labs

- Interactive Lecture Demonstrations

- Interactive Lectures

- Investigative Case Based Learning

- Just in Time Teaching

- Mathematical and Statistical Models

- Peer Review

- Role Playing

- Service Learning

- Socratic Questioning

- Spreadsheets Across the Curriculum

- Studio Teaching in the Geosciences

- Teaching Urban Students

- Teaching with Data

- Teaching with GIS

- Teaching with Google Earth

- ...click to see 28 more...

- Teaching with Visualizations

- Undergraduate Research

- What is Undergraduate Research?

- Why Use Undergraduate Research Experiences?

- How To Engage Undergraduates in Research

- Forms of Undergraduate Research Experiences

- Determine Project Needs

- Set Expectations

- Structure the Critical Elements

- Provide the Right Support

- Assess the Experience

- Further the Undergraduate Research Experience

- References and Resources

- Using an Earth System Approach

- About this Site

- Accessibility

Citing and Terms of Use

Material on this page is offered under a Creative Commons license unless otherwise noted below.

Show terms of use for text on this page »

Show terms of use for media on this page »

- None found in this page

- Initial Publication Date: July 30, 2010

- Short URL: https://serc.carleton.edu/48175 What's This?

Educational resources and simple solutions for your research journey

What Are Research Objectives and How to Write Them (with Examples)

Table of Contents

Introduction

Research is at the center of everything researchers do, and setting clear, well-defined research objectives plays a pivotal role in guiding scholars toward their desired outcomes. Research papers are essential instruments for researchers to effectively communicate their work. Among the many sections that constitute a research paper, the introduction plays a key role in providing a background and setting the context. 1 Research objectives, which define the aims of the study, are usually stated in the introduction. Every study has a research question that the authors are trying to answer, and the objective is an active statement about how the study will answer this research question. These objectives help guide the development and design of the study and steer the research in the appropriate direction; if this is not clearly defined, a project can fail!

Research studies have a research question, research hypothesis, and one or more research objectives. A research question is what a study aims to answer, and a research hypothesis is a predictive statement about the relationship between two or more variables, which the study sets out to prove or disprove. Objectives are specific, measurable goals that the study aims to achieve. The difference between these three is illustrated by the following example:

- Research question : How does low-intensity pulsed ultrasound (LIPUS) compare with a placebo device in managing the symptoms of skeletally mature patients with patellar tendinopathy?

- Research hypothesis : Pain levels are reduced in patients who receive daily active-LIPUS (treatment) for 12 weeks compared with individuals who receive inactive-LIPUS (placebo).

- Research objective : To investigate the clinical efficacy of LIPUS in the management of patellar tendinopathy symptoms.

This article discusses the importance of clear, well-thought out objectives and suggests methods to write them clearly.

What is the introduction in research papers?

Research objectives are usually included in the introduction section. This section is the first that the readers will read so it is essential that it conveys the subject matter appropriately and is well written to create a good first impression. A good introduction sets the tone of the paper and clearly outlines the contents so that the readers get a quick snapshot of what to expect.

A good introduction should aim to: 2,3

- Indicate the main subject area, its importance, and cite previous literature on the subject

- Define the gap(s) in existing research, ask a research question, and state the objectives

- Announce the present research and outline its novelty and significance

- Avoid repeating the Abstract, providing unnecessary information, and claiming novelty without accurate supporting information.

Why are research objectives important?

Objectives can help you stay focused and steer your research in the required direction. They help define and limit the scope of your research, which is important to efficiently manage your resources and time. The objectives help to create and maintain the overall structure, and specify two main things—the variables and the methods of quantifying the variables.

A good research objective:

- defines the scope of the study

- gives direction to the research

- helps maintain focus and avoid diversions from the topic

- minimizes wastage of resources like time, money, and energy

Types of research objectives

Research objectives can be broadly classified into general and specific objectives . 4 General objectives state what the research expects to achieve overall while specific objectives break this down into smaller, logically connected parts, each of which addresses various parts of the research problem. General objectives are the main goals of the study and are usually fewer in number while specific objectives are more in number because they address several aspects of the research problem.

Example (general objective): To investigate the factors influencing the financial performance of firms listed in the New York Stock Exchange market.

Example (specific objective): To assess the influence of firm size on the financial performance of firms listed in the New York Stock Exchange market.

In addition to this broad classification, research objectives can be grouped into several categories depending on the research problem, as given in Table 1.

Table 1: Types of research objectives

| Exploratory | Explores a previously unstudied topic, issue, or phenomenon; aims to generate ideas or hypotheses |

| Descriptive | Describes the characteristics and features of a particular population or group |

| Explanatory | Explains the relationships between variables; seeks to identify cause-and-effect relationships |

| Predictive | Predicts future outcomes or events based on existing data samples or trends |

| Diagnostic | Identifies factors contributing to a particular problem |

| Comparative | Compares two or more groups or phenomena to identify similarities and differences |

| Historical | Examines past events and trends to understand their significance and impact |

| Methodological | Develops and improves research methods and techniques |

| Theoretical | Tests and refines existing theories or helps develop new theoretical perspectives |

Characteristics of research objectives

Research objectives must start with the word “To” because this helps readers identify the objective in the absence of headings and appropriate sectioning in research papers. 5,6

- A good objective is SMART (mostly applicable to specific objectives):

- Specific—clear about the what, why, when, and how

- Measurable—identifies the main variables of the study and quantifies the targets

- Achievable—attainable using the available time and resources

- Realistic—accurately addresses the scope of the problem

- Time-bound—identifies the time in which each step will be completed

- Research objectives clarify the purpose of research.

- They help understand the relationship and dissimilarities between variables.

- They provide a direction that helps the research to reach a definite conclusion.

How to write research objectives?

Research objectives can be written using the following steps: 7

- State your main research question clearly and concisely.

- Describe the ultimate goal of your study, which is similar to the research question but states the intended outcomes more definitively.

- Divide this main goal into subcategories to develop your objectives.

- Limit the number of objectives (1-2 general; 3-4 specific)

- Assess each objective using the SMART

- Start each objective with an action verb like assess, compare, determine, evaluate, etc., which makes the research appear more actionable.

- Use specific language without making the sentence data heavy.

- The most common section to add the objectives is the introduction and after the problem statement.

- Add the objectives to the abstract (if there is one).

- State the general objective first, followed by the specific objectives.

Formulating research objectives

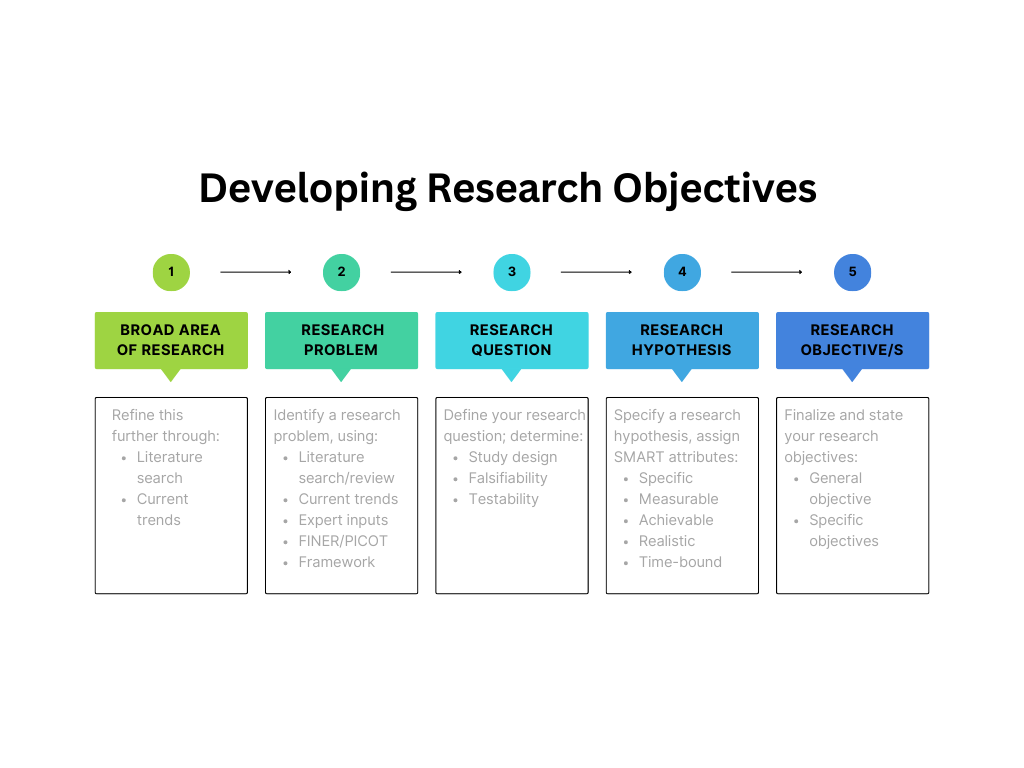

Formulating research objectives has the following five steps, which could help researchers develop a clear objective: 8

- Identify the research problem.

- Review past studies on subjects similar to your problem statement, that is, studies that use similar methods, variables, etc.

- Identify the research gaps the current study should cover based on your literature review. These gaps could be theoretical, methodological, or conceptual.

- Define the research question(s) based on the gaps identified.

- Revise/relate the research problem based on the defined research question and the gaps identified. This is to confirm that there is an actual need for a study on the subject based on the gaps in literature.

- Identify and write the general and specific objectives.

- Incorporate the objectives into the study.

Advantages of research objectives

Adding clear research objectives has the following advantages: 4,8

- Maintains the focus and direction of the research

- Optimizes allocation of resources with minimal wastage

- Acts as a foundation for defining appropriate research questions and hypotheses

- Provides measurable outcomes that can help evaluate the success of the research

- Determines the feasibility of the research by helping to assess the availability of required resources

- Ensures relevance of the study to the subject and its contribution to existing literature

Disadvantages of research objectives

Research objectives also have few disadvantages, as listed below: 8

- Absence of clearly defined objectives can lead to ambiguity in the research process

- Unintentional bias could affect the validity and accuracy of the research findings

Key takeaways

- Research objectives are concise statements that describe what the research is aiming to achieve.

- They define the scope and direction of the research and maintain focus.

- The objectives should be SMART—specific, measurable, achievable, realistic, and time-bound.

- Clear research objectives help avoid collection of data or resources not required for the study.

- Well-formulated specific objectives help develop the overall research methodology, including data collection, analysis, interpretation, and utilization.

- Research objectives should cover all aspects of the problem statement in a coherent way.

- They should be clearly stated using action verbs.

Frequently asked questions on research objectives

Q: what’s the difference between research objectives and aims 9.

A: Research aims are statements that reflect the broad goal(s) of the study and outline the general direction of the research. They are not specific but clearly define the focus of the study.

Example: This research aims to explore employee experiences of digital transformation in retail HR.

Research objectives focus on the action to be taken to achieve the aims. They make the aims more practical and should be specific and actionable.

Example: To observe the retail HR employees throughout the digital transformation.

Q: What are the examples of research objectives, both general and specific?

A: Here are a few examples of research objectives:

- To identify the antiviral chemical constituents in Mumbukura gitoniensis (general)

- To carry out solvent extraction of dried flowers of Mumbukura gitoniensis and isolate the constituents. (specific)

- To determine the antiviral activity of each of the isolated compounds. (specific)

- To examine the extent, range, and method of coral reef rehabilitation projects in five shallow reef areas adjacent to popular tourist destinations in the Philippines.

- To investigate species richness of mammal communities in five protected areas over the past 20 years.

- To evaluate the potential application of AI techniques for estimating best-corrected visual acuity from fundus photographs with and without ancillary information.

- To investigate whether sport influences psychological parameters in the personality of asthmatic children.

Q: How do I develop research objectives?

A: Developing research objectives begins with defining the problem statement clearly, as illustrated by Figure 1. Objectives specify how the research question will be answered and they determine what is to be measured to test the hypothesis.

Q: Are research objectives measurable?

A: The word “measurable” implies that something is quantifiable. In terms of research objectives, this means that the source and method of collecting data are identified and that all these aspects are feasible for the research. Some metrics can be created to measure your progress toward achieving your objectives.

Q: Can research objectives change during the study?

A: Revising research objectives during the study is acceptable in situations when the selected methodology is not progressing toward achieving the objective, or if there are challenges pertaining to resources, etc. One thing to keep in mind is the time and resources you would have to complete your research after revising the objectives. Thus, as long as your problem statement and hypotheses are unchanged, minor revisions to the research objectives are acceptable.

Q: What is the difference between research questions and research objectives? 10

| Broad statement; guide the overall direction of the research | Specific, measurable goals that the research aims to achieve |

| Identify the main problem | Define the specific outcomes the study aims to achieve |

| Used to generate hypotheses or identify gaps in existing knowledge | Used to establish clear and achievable targets for the research |

| Not mutually exclusive with research objectives | Should be directly related to the research question |

| Example: | Example: |

Q: Are research objectives the same as hypotheses?

A: No, hypotheses are predictive theories that are expressed in general terms. Research objectives, which are more specific, are developed from hypotheses and aim to test them. A hypothesis can be tested using several methods and each method will have different objectives because the methodology to be used could be different. A hypothesis is developed based on observation and reasoning; it is a calculated prediction about why a particular phenomenon is occurring. To test this prediction, different research objectives are formulated. Here’s a simple example of both a research hypothesis and research objective.

Research hypothesis : Employees who arrive at work earlier are more productive.

Research objective : To assess whether employees who arrive at work earlier are more productive.

To summarize, research objectives are an important part of research studies and should be written clearly to effectively communicate your research. We hope this article has given you a brief insight into the importance of using clearly defined research objectives and how to formulate them.

- Farrugia P, Petrisor BA, Farrokhyar F, Bhandari M. Practical tips for surgical research: Research questions, hypotheses and objectives. Can J Surg. 2010 Aug;53(4):278-81.

- Abbadia J. How to write an introduction for a research paper. Mind the Graph website. Accessed June 14, 2023. https://mindthegraph.com/blog/how-to-write-an-introduction-for-a-research-paper/

- Writing a scientific paper: Introduction. UCI libraries website. Accessed June 15, 2023. https://guides.lib.uci.edu/c.php?g=334338&p=2249903

- Research objectives—Types, examples and writing guide. Researchmethod.net website. Accessed June 17, 2023. https://researchmethod.net/research-objectives/#:~:text=They%20provide%20a%20clear%20direction,track%20and%20achieve%20their%20goals .

- Bartle P. SMART Characteristics of good objectives. Community empowerment collective website. Accessed June 16, 2023. https://cec.vcn.bc.ca/cmp/modules/pd-smar.htm

- Research objectives. Studyprobe website. Accessed June 18, 2023. https://www.studyprobe.in/2022/08/research-objectives.html

- Corredor F. How to write objectives in a research paper. wikiHow website. Accessed June 18, 2023. https://www.wikihow.com/Write-Objectives-in-a-Research-Proposal

- Research objectives: Definition, types, characteristics, advantages. AccountingNest website. Accessed June 15, 2023. https://www.accountingnest.com/articles/research/research-objectives

- Phair D., Shaeffer A. Research aims, objectives & questions. GradCoach website. Accessed June 20, 2023. https://gradcoach.com/research-aims-objectives-questions/

- Understanding the difference between research questions and objectives. Accessed June 21, 2023. https://board.researchersjob.com/blog/research-questions-and-objectives

R Discovery is a literature search and research reading platform that accelerates your research discovery journey by keeping you updated on the latest, most relevant scholarly content. With 250M+ research articles sourced from trusted aggregators like CrossRef, Unpaywall, PubMed, PubMed Central, Open Alex and top publishing houses like Springer Nature, JAMA, IOP, Taylor & Francis, NEJM, BMJ, Karger, SAGE, Emerald Publishing and more, R Discovery puts a world of research at your fingertips.

Try R Discovery Prime FREE for 1 week or upgrade at just US$72 a year to access premium features that let you listen to research on the go, read in your language, collaborate with peers, auto sync with reference managers, and much more. Choose a simpler, smarter way to find and read research – Download the app and start your free 7-day trial today !

Related Posts

Simple Random Sampling: Definition, Methods, and Examples

What is a Case Study in Research? Definition, Methods, and Examples

- Teaching Tips

The Ultimate Guide to Writing Learning Objectives: Definitions, Strategies and Examples

Simple steps to writing effective, measurable learning objectives for university and college educators. This guide includes practical approaches and helpful examples.

Top Hat Staff

While it’s natural to focus on theory and concepts when designing your course, it’s equally important to think about the net result you want to achieve in terms of student learning. Learning objectives focus on just that—they articulate what students should be able to know, do and create by the end of a course. They’re also the key to creating a course in which courseware, context, teaching strategies, student learning activities and assessments all work together to support students’ achievement of these objectives.

This guide presents essential information about how to write effective, measurable learning objectives that will create a strong structure and instructional design for your course.

Table of contents

What are learning objectives, learning objectives vs. learning outcomes, how to write learning objectives, tools for developing effective learning objectives, examples of learning objectives.

Learning objectives identify what the learner will know and be able to do by the end of a course. Grounded in three primary learning areas—attitudes, skills and knowledge—clear learning objectives help organize student progress throughout the curriculum .

While the terms “learning objectives” and “learning outcomes” are often used interchangeably, there are subtle differences between them.

One key distinction is that learning objectives are a description of the overarching goals for a course or unit. Learning outcomes , on the other hand, outline goals for the individual lessons comprising that course or unit. Learning outcomes should be measurable and observable, so students can gauge their progress toward achieving the broader course objectives.

Another distinction between the two concepts is that learning objectives focus on the educator or institution’s educational goals for the course. For students, goals and progress in a specific course or program are measured by learning outcomes.

Learning objectives help students understand how each lesson relates to the previous one. This way, students can understand how each course concept relates to the course’s goals, as well as degree or course goals. When writing measurable student learning objectives, instructors should ensure that they are structured in a way that makes it easy for students to assess their own progress, as well as the way forward in their learning.

Strong learning objectives should:

- Focus on what students should learn in a course rather than what the instructor plans to teach

- Break down each task into an appropriate sequence of skills students can practice to reach each objective

- Make use of action-oriented language

- Be clear and specific so students understand what they will learn and why they are learning it

Learning objectives should also be measurable. In order to be effective, they must lay out what success looks like. This way, students can accurately gauge their progress and performance. From these criteria, students should be able to clearly identify when they have completed an element of the course and are ready to move on to the next one.

Key elements to consider

By answering certain fundamental questions, you can begin the process of developing clear learning objectives armed with the information to craft them effectively.

- Which higher-order skills or practical abilities do you want students to possess after attending your course that they did not possess beforehand?

- What do your students need to know and understand in order to get from where they are now to where you want them to be by the end of the course?

- Which three main items do you want students to take away from your course if they learn nothing else?

3 steps to writing learning objectives

Writing strong and effective learning objectives is a matter of three simple steps:

- Explain the precise skill or task the student will perform.

- Describe how the student will execute the given skill or task and demonstrate relevant knowledge and competency—a quiz, test, group discussion, presentation, research project.

- Lay out the specific criteria you will use to measure student performance at the end of the learning experience.

Bloom’s Taxonomy

Used to develop effective learning objectives, Bloom’s Taxonomy is an educational framework that is designed to help educators identify not only subject matter but also the depth of learning they want students to achieve. Then, these objectives are used to create assessments that accurately report on students’ progress towards these outcomes.

The revised Bloom’s Taxonomy (2001) comprises three domains—cognitive, affective and psychomotor. In creating effective learning objectives, most educators choose to focus on the cognitive domain. The cognitive domain prioritizes intellectual skills such as critical thinking, problem-solving, and creating a knowledge base. The levels of this domain span from simple memorization designed to build the knowledge of learners, to creating a new idea or working theory based on previously learned information. In this domain, learners are expected to progress linearly through the levels, starting at “remember” and concluding at “create,” in order to reach subject mastery.

The following are the six levels of the cognitive domain:

- Remembering

- Understanding

Action verbs

These action verbs and sample learning objectives are mapped to each level of Bloom’s Taxonomy’s cognitive domain. Here, we provide a breakdown of how to implement each level in your classroom. Some examples of action verbs useful for articulating each of the levels within the cognitive domain include:

- Sample learning objective: Upon completion of a geography workshop, students will be able to list the different layers of rock in a given natural structure.

- Sample learning objective: By the end of a Sociology lesson, students will be able to identify instruments for collecting data and measurements for the conducting and planning of research.

- Sample learning objective: After a lesson on literary analysis, students will be able to assign a cohesive reading list for an imagined class on a particular subtopic within the literary realm.

- Sample learning objective: At the end of a course in global economics, students will be able to analyze the economic theories behind various macroeconomic policies and accurately categorize them.

- Sample learning objective: Upon completion of a course on the history of war, students will be able to compare and contrast any two historic wars using timelines of the respective conflicts.

- Sample learning objective: Upon completion of the astronomy course, students will be able to predict the motion and appearance of celestial objects and curate data on the subject from multiple sources and communicate procedures, results and conclusions properly.

The SMART strategy

Simply put, learning objectives are goals for teaching and learning. They provide a sense of direction, motivation and focus. By setting objectives, you can provide yourself and your students with a target to aim for. A straightforward way to set realistic, achievable expectations is through the SMART strategy, ensuring objectives are:

- Specific : Unambiguous, well-defined and clear.

- Measurable : Designed with specific criteria of how to measure your progress toward the accomplishment of the goal in mind.

- Achievable : Attainable and possible to achieve.

- Realistic : Within reach, realistic, and relevant to the course or program’s purpose.

- Timely : With a clearly defined timeline, including a starting date and a target date, to ensure you can set mini-milestones and check-ins throughout the duration of your course.

By writing measurable learning objectives you can better choose and organize content and use that to select the most appropriate instructional strategies and assessments to meet the learning goals for your course.

- Using language formally vs. informally

- Explaining how to write and speak in each type of language

- Teaching others how to choose and use the appropriate type of language in different situations

- Good example: Upon completion of this course, students will possess the ability to identify and develop instruments for collecting data and measures for executing academic research.

- Poor example: After completing this course, students will be able to explain the organizational structure.

- Poor example: Students will comprehend the importance of the Civil War.

The first two are good learning objectives because they explain the exact skill or task the student will perform, as well as how they will be tested and evaluated on their performance. The second examples are poor because they are vague and do not include how the knowledge acquired will be evaluated.

Student learning improves when they know what is expected of them. When learning objectives are clear, students are better prepared for a deeper approach to learning. This means that students seek meaning, relate and extend ideas, look for patterns and underlying principles, check evidence, examine arguments critically and engage with course content in a more sophisticated way.

For instructors, this means a more engaged and connected classroom community that works together. By setting clear guidelines for what you intend to teach and for students to learn, you can ensure that you are laying the foundation for a successful and more motivating educational experience.

Hattie, J. A. C., & Donoghue, G. M. (2016). Learning strategies: a synthesis and conceptual model. Science of Learning , 1, 1–13. doi:10.1038/npjscilearn.2016.13

Marsh, P.A. (2007). What is known about student learning outcomes and how does it relate to the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning? International Journal for the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, 1(2), article 22.

Trigwell, K. & Prosser, M. (1991). Improving the quality of student learning: the influence of learning context and student approaches to learning on learning outcomes. Higher Education , 22(3), 251–266.

Recommended Readings

25 Effective Instructional Strategies For Educators

The Complete Guide to Effective Online Teaching

Subscribe to the top hat blog.

Join more than 10,000 educators. Get articles with higher ed trends, teaching tips and expert advice delivered straight to your inbox.

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Starting the research process

- Research Objectives | Definition & Examples

Research Objectives | Definition & Examples

Published on July 12, 2022 by Eoghan Ryan . Revised on November 20, 2023.

Research objectives describe what your research is trying to achieve and explain why you are pursuing it. They summarize the approach and purpose of your project and help to focus your research.

Your objectives should appear in the introduction of your research paper , at the end of your problem statement . They should:

- Establish the scope and depth of your project

- Contribute to your research design

- Indicate how your project will contribute to existing knowledge

Table of contents

What is a research objective, why are research objectives important, how to write research aims and objectives, smart research objectives, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about research objectives.

Research objectives describe what your research project intends to accomplish. They should guide every step of the research process , including how you collect data , build your argument , and develop your conclusions .

Your research objectives may evolve slightly as your research progresses, but they should always line up with the research carried out and the actual content of your paper.

Research aims

A distinction is often made between research objectives and research aims.

A research aim typically refers to a broad statement indicating the general purpose of your research project. It should appear at the end of your problem statement, before your research objectives.

Your research objectives are more specific than your research aim and indicate the particular focus and approach of your project. Though you will only have one research aim, you will likely have several research objectives.

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

Research objectives are important because they:

- Establish the scope and depth of your project: This helps you avoid unnecessary research. It also means that your research methods and conclusions can easily be evaluated .

- Contribute to your research design: When you know what your objectives are, you have a clearer idea of what methods are most appropriate for your research.

- Indicate how your project will contribute to extant research: They allow you to display your knowledge of up-to-date research, employ or build on current research methods, and attempt to contribute to recent debates.

Once you’ve established a research problem you want to address, you need to decide how you will address it. This is where your research aim and objectives come in.

Step 1: Decide on a general aim

Your research aim should reflect your research problem and should be relatively broad.

Step 2: Decide on specific objectives

Break down your aim into a limited number of steps that will help you resolve your research problem. What specific aspects of the problem do you want to examine or understand?

Step 3: Formulate your aims and objectives

Once you’ve established your research aim and objectives, you need to explain them clearly and concisely to the reader.

You’ll lay out your aims and objectives at the end of your problem statement, which appears in your introduction. Frame them as clear declarative statements, and use appropriate verbs to accurately characterize the work that you will carry out.

The acronym “SMART” is commonly used in relation to research objectives. It states that your objectives should be:

- Specific: Make sure your objectives aren’t overly vague. Your research needs to be clearly defined in order to get useful results.

- Measurable: Know how you’ll measure whether your objectives have been achieved.

- Achievable: Your objectives may be challenging, but they should be feasible. Make sure that relevant groundwork has been done on your topic or that relevant primary or secondary sources exist. Also ensure that you have access to relevant research facilities (labs, library resources , research databases , etc.).

- Relevant: Make sure that they directly address the research problem you want to work on and that they contribute to the current state of research in your field.

- Time-based: Set clear deadlines for objectives to ensure that the project stays on track.

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

If you want to know more about the research process , methodology , research bias , or statistics , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

Methodology

- Sampling methods

- Simple random sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Cluster sampling

- Likert scales

- Reproducibility

Statistics

- Null hypothesis

- Statistical power

- Probability distribution

- Effect size

- Poisson distribution

Research bias

- Optimism bias

- Cognitive bias

- Implicit bias

- Hawthorne effect

- Anchoring bias

- Explicit bias

Research objectives describe what you intend your research project to accomplish.

They summarize the approach and purpose of the project and help to focus your research.

Your objectives should appear in the introduction of your research paper , at the end of your problem statement .

Your research objectives indicate how you’ll try to address your research problem and should be specific:

Once you’ve decided on your research objectives , you need to explain them in your paper, at the end of your problem statement .

Keep your research objectives clear and concise, and use appropriate verbs to accurately convey the work that you will carry out for each one.

I will compare …

A research aim is a broad statement indicating the general purpose of your research project. It should appear in your introduction at the end of your problem statement , before your research objectives.

Research objectives are more specific than your research aim. They indicate the specific ways you’ll address the overarching aim.

Scope of research is determined at the beginning of your research process , prior to the data collection stage. Sometimes called “scope of study,” your scope delineates what will and will not be covered in your project. It helps you focus your work and your time, ensuring that you’ll be able to achieve your goals and outcomes.

Defining a scope can be very useful in any research project, from a research proposal to a thesis or dissertation . A scope is needed for all types of research: quantitative , qualitative , and mixed methods .

To define your scope of research, consider the following:

- Budget constraints or any specifics of grant funding

- Your proposed timeline and duration

- Specifics about your population of study, your proposed sample size , and the research methodology you’ll pursue

- Any inclusion and exclusion criteria

- Any anticipated control , extraneous , or confounding variables that could bias your research if not accounted for properly.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Ryan, E. (2023, November 20). Research Objectives | Definition & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved June 30, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/research-process/research-objectives/

Is this article helpful?

Eoghan Ryan

Other students also liked, writing strong research questions | criteria & examples, how to write a problem statement | guide & examples, get unlimited documents corrected.

✔ Free APA citation check included ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

- eLearning Platform

- eLearning Content

- Access 800 Courses on our Platform

- Bespoke eLearning

- Our Pricing

- Request a Demo

- Content Partnerships

- Whitepapers

- Most Popular Blogs

- Personal Learning Journeys

- Training Feedback Form

- Training Needs Analysis Template

- Personal Development Plan Template

- Learning and Development Strategy

- Talent Management Strategy

- Kirkpatrick Evaluation Model

- Microlearning

- Informal Learning

- 70 20 10 Learning

Home » Blog » Learning Objectives: How to Write, Types and Examples

Learning Objectives: How to Write, Types and Examples

For students, learning objectives provide an overview of the key points and main building blocks covered in a topic.

Skillshub’s experience in the academic and corporate world shows that having established learning objectives can help to improve engagement, motivation, and results.

As a thought leader in the field of educational objectives, we believe there are several types and structures of learning objectives you should consider when planning a course or lesson.

In this article, we’ll look at how to write learning objectives effectively, different types of learning objectives, and provide some example objectives to help you get started.

What are Learning Objectives?

Before we cover the details of writing learning objectives, it’s important to understand what they are and why having them is essential.

Learning objectives provide an overview of the topics covered in a course or lesson and allow everyone involved—teachers, students, and even administrators—to have a shared understanding of the goals for any given session.

In simple terms, learning objectives:

- Outline what students should be able to do after completing the lesson

- Provide a shared understanding of the topics covered in a course or lesson

- Help teachers plan and assess learning activities

- Allow administrators to monitor student progress

- Make it easier for students to review key material

Essentially, learning objectives provide a framework that benefits everyone involved in the learning process.

Learn How To Create Personal Learning Journeys For FREE!

What’s the difference between a learning objective and a learning outcome.

Learning outcomes and learning objectives are superficially similar, as in both cases, the two terms are used to describe what students should be able to do after completing a course or lesson.

However, there is an essential distinction between the two.

A learning objective refers specifically to the topics that will be covered during a lesson/course. Learning outcomes, on the other hand, look beyond mere knowledge and provide evaluations on how well students can apply what they’ve learned.

For instance, a learning objective may be to “understand the components of the water cycle”. A learning outcome related to this might be to “identify ways in which humans are impacting the global water cycle.”

The learning objective here defines how the lesson or course should be structured, while the learning outcome provides an evaluation of how well students understand and can apply what they have learned.

Benefits of Well-Written Learning Objectives

Now that you’ve got a clearer understanding of what learning objectives are and how they differ from learning outcomes, let’s take a look at the benefits of having well-crafted learning objectives in place.

There is a wide range of material benefits associated with creating and leveraging learning objectives, including:

Improved lesson and course planning

A clearly stated learning objective provides the basis for lesson and course planning. Well-written objectives help teachers identify not only the topics that need to be covered, but also the resources (e.g., books or videos) needed to cover them effectively.

Improved assessment

Having established learning objectives in place helps teachers create assessments which accurately evaluate student understanding of any given topic.

Teachers can use learning objectives to create quizzes, tests, and other assessments to accurately evaluate student knowledge.

Improved student understanding

Clear learning objectives are helpful for students in a number of ways.

For instance, having an overview of the topics covered in a lesson or course can help students track their progress more effectively and identify areas which may need review.

Furthermore, having objectives in place can help reduce the cognitive load associated with learning new topics, allowing students to focus more on their understanding of a subject rather than worrying about what needs to be done next.

Increased student engagement

Having established learning objectives in place can help keep students and employees engaged during lessons and lectures.

When students have a clear understanding of the topics covered, it becomes easier for them to follow along with the lesson plan and stay focused on the topic at hand.

Furthermore, providing objectives can motivate students by setting out specific goals they should be working towards.

More effective communication between teachers, students, and administrators

A shared understanding of learning objectives helps to ensure effective communication between all stakeholders in the educational process.

Teachers can use objectives to effectively communicate expectations with students, while administrators can use them to monitor student progress.

Having established learning objectives also makes it easier for teachers and administrators to identify potential issues or areas in which students may need additional support.

A better focus on the topics covered in a given course or lesson

Finally, having learning objectives in place helps to ensure that all stakeholders are focusing on the topics covered in a lesson or course.

Objectives set out specific goals which everyone should be working towards and help to keep discussions focused.

By providing an overview of the topics covered, learning objectives can also help teachers identify areas which need further exploration or review.

Overall, having clear learning objectives can help to improve results by providing everyone involved with a shared understanding of the goals of any given lesson or course.

How to Write Effective Learning Objectives

While the basic idea of learning objectives is simple, the act of creating effective learning objectives requires a bit more thought and consideration.

Let’s take a look at some tips to help you craft practical learning objectives:

Understanding the ABCD Model

The ABCD model provides a foundation for creating effective learning objectives.

The ABCD stands for: