Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

2.3 Methods of Researching Media Effects

Learning objectives.

- Identify the prominent media research methods.

- Explain the uses of media research methods in a research project.

Media theories provide the framework for approaching questions about media effects ranging from as simple as how 10-year-old boys react to cereal advertisements to as broad as how Internet use affects literacy. Once researchers visualize a project and determine a theoretical framework, they must choose actual research methods. Contemporary research methods are greatly varied and can range from analyzing old newspapers to performing controlled experiments.

Content Analysis

Content analysis is a research technique that involves analyzing the content of various forms of media. Through content analysis, researchers hope to understand both the people who created the content and the people who consumed it. A typical content analysis project does not require elaborate experiments. Instead, it simply requires access to the appropriate media to analyze, making this type of research an easier and inexpensive alternative to other forms of research involving complex surveys or human subjects.

Content analysis studies require researchers to define what types of media to study. For example, researchers studying violence in the media would need to decide which types of media to analyze, such as television, and the types of formats to examine, such as children’s cartoons. The researchers would then need to define the terms used in the study; media violence can be classified according to the characters involved in the violence (strangers, family members, or racial groups), the type of violence (self-inflicted, slapstick, or against others), or the context of the violence (revenge, random, or duty-related). These are just a few of the ways that media violence could be studied with content-analysis techniques (Berger, 1998).

Archival Research

Any study that analyzes older media must employ archival research, which is a type of research that focuses on reviewing historical documents such as old newspapers and past publications. Old local newspapers are often available on microfilm at local libraries or at the newspaper offices. University libraries generally provide access to archives of national publications such as The New York Times or Time ; publications can also increasingly be found in online databases or on websites.

Older radio programs are available for free or by paid download through a number of online sources. Many television programs and films have also been made available for free download, or for rent or sale through online distributors. Performing an online search for a particular title will reveal the options available.

Resources such as the Internet Archive ( www.archive.org ) work to archive a number of media sources. One important role of the Internet Archive is website archiving. Internet archives are invaluable for a study of online media because they store websites that have been deleted or changed. These archives have made it possible for Internet content analyses that would have otherwise been impossible.

Surveys are ubiquitous in modern life. Questionaires record data on anything from political preferences to personal hygiene habits. Media surveys generally take one of the following two forms.

A descriptive survey aims to find the current state of things, such as public opinion or consumer preferences. In media, descriptive surveys establish television and radio ratings by finding the number of people who watch or listen to particular programs. An analytical survey, however, does more than simply document a current situation. Instead, it attempts to find out why a particular situation exists. Researchers pose questions or hypotheses about media, and then conduct analytical surveys to answer these questions. Analytical surveys can determine the relationship between different forms of media consumption and the lifestyles and habits of media consumers.

Surveys can employ either open-ended or closed-ended questions. Open-ended questions require the participant to generate answers in their own words, while closed-ended questions force the participant to select an answer from a list. Although open-ended questions allow for a greater variety of answers, the results of closed-ended questions are easier to tabulate. Although surveys are useful in media studies, effective use requires keeping their limitations in mind.

Social Role Analysis

As part of child rearing, parents teach their children about social roles. When parents prepare children to attend school for example, they explain the basics of school rules and what is expected of a student to help the youngsters understand the role of students. Like the role of a character in a play, this role carries specific expectations that differentiate school from home. Adults often play a number of different roles as they navigate between their responsibilities as parents, employees, friends, and citizens. Any individual may play a number of roles depending on his or her specific life choices.

Social role analysis of the media involves examining various individuals in the media and analyzing the type of role that each plays. Role analysis research can consider the roles of men, women, children, members of a racial minority, or members of any other social group in specific types of media. For example, if the role children play in cartoons is consistently different from the role they play in sitcoms, then certain conclusions might be drawn about both of these formats. Analyzing roles used in media allows researchers to gain a better understanding of the messages that the mass media sends (Berger, 1998).

Depth Interviews

The depth interview is an anthropological research tool that is also useful in media studies. Depth interviews take surveys one step further by allowing researchers to directly ask a study participant specific questions to gain a fuller understanding of the participant’s perceptions and experiences. Depth interviews have been used in research projects that follow newspaper reporters to find out their reasons for reporting certain stories and in projects that attempt to understand the motivations for reading romance novels. Depth interviews can provide a deeper understanding of the media consumption habits of particular groups of people (Priest, 2010).

Rhetorical Analysis

Rhetorical analysis involves examining the styles used in media and attempting to understand the kinds of messages those styles convey. Media styles include form, presentation, composition, use of metaphors, and reasoning structure. Rhetorical analysis reveals the messages not apparent in a strict reading of content. Studies involving rhetorical analysis have focused on media such as advertising to better understand the roles of style and rhetorical devices in media messages (Gunter, 2000).

Focus Groups

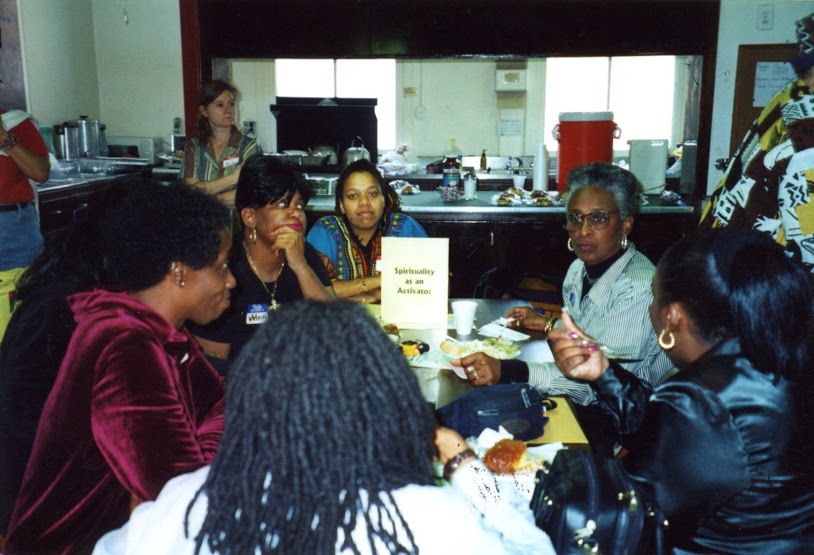

Like depth interviews, focus groups allow researchers to better understand public responses to media. Unlike a depth interview, however, a focus group allows the participants to establish a group dynamic that more closely resembles that of normal media consumption. In media studies, researchers can employ focus groups to judge the reactions of a group to specific media styles and to content. This can be a valuable means of understanding the reasons for consuming specific types of media.

Focus groups are effective ways to obtain a group opinion on media.

Wikimedia Commons – CC BY-SA 3.0.

Experiments

Media research studies also sometimes use controlled experiments that expose a test group to an experience involving media and measure the effects of that experience. Researchers then compare these measurements to those of a control group that had key elements of the experience removed. For example, researchers may show one group of children a program with three incidents of cartoon violence and another control group of similar children the same program without the violent incidents. Researchers then ask the children from both groups the same sets of questions, and the results are compared.

Participant Observation

In participant observation , researchers try to become part of the group they are studying. Although this technique is typically associated with anthropological studies in which a researcher lives with members of a particular culture to gain a deeper understanding of their values and lives, it is also used in media research.

Media consumption often takes place in groups. Families or friends gather to watch favorite programs, children may watch Saturday morning cartoons with a group of their peers, and adults may host viewing parties for televised sporting events or awards shows. These groups reveal insights into the role of media in the lives of the public. A researcher might join a group that watches football together and stay with the group for an entire season. By becoming a part of the group, the researcher becomes part of the experiment and can reveal important influences of media on culture (Priest).

Researchers have studied online role-playing games, such as World of Warcraft , in this manner. These games reveal an interesting aspect of group dynamics: Although participants are not in physical proximity, they function as a group within the game. Researchers are able to study these games by playing them. In the book Digital Culture, Play, and Identity: A World of Warcraft Reader , a group of researchers discussed the results of their participant observation studies. The studies reveal the surprising depth of culture and unwritten rules that exist in the World of Warcraft universe and give important interpretations of why players pursue the game with such dedication (Corneliussen & Rettberg, 2008).

Key Takeaways

- Media research methods are the practical procedures for carrying out a research project. These methods include content analysis, surveys, focus groups, experiments, and participant observation.

- Research methods generally involve either test subjects or analysis of media. Methods involving test subjects include surveys, depth interviews, focus groups, and experiments. Analysis of media can include content, style, format, social roles, and archival analysis.

Media research methods offer a variety of procedures for performing a media study. Each of these methods varies in cost; thus, a project with a lower budget would be prohibited from using some of the more costly methods. Consider a project on teen violence and video game use. Then answer the following short-response questions. Each response should be a minimum of one paragraph.

- Which methods would a research organization with a low budget favor for this project? Why?

- How might the results of the project differ from those of one with a higher budget?

Berger, Arthur Asa. Media Research Techniques (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 1998), 23–24.

Corneliussen, Hilde and Jill Walker Rettberg, “Introduction: ‘Orc ProfessorLFG,’ or Researching in Azeroth,” in Digital Culture, Play, and Identity: A World of Warcraft Reader , ed. Hilde Corneliussen and Jill Walker Rettberg (Cambridge, MA: Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 2008), 6–7.

Gunter, Barrie. Media Research Methods: Measuring Audiences, Reactions and Impact (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2000), 89.

Priest, Susanna Hornig Doing Media Research: An Introduction (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2010), 16–22.

Priest, Susanna Hornig Doing Media Research , 96–98.

Understanding Media and Culture Copyright © 2016 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Case Studies on Media Reporting and Media Influence During the COVID-19 Pandemic

- First Online: 03 March 2022

Cite this chapter

- Kejo Starosta 5

Part of the book series: Sustainable Management, Wertschöpfung und Effizienz ((SMWE))

267 Accesses

The COVID-19 virus that has spread throughout the world since the beginning of 2020 brought disruptive changes at many levels, including demographic, economic, and social shifts. In the media environment, too, the pandemic brought unprecedented changes, with unprecedented media reporting on a single topic. The following case studies try to analyse how this infodemic spread throughout Europe and how it affected society as well as consumers and businesses.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Eglisau, Switzerland

Kejo Starosta

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Kejo Starosta .

1 Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary file1 (PDF 11876 kb)

Rights and permissions.

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2022 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden GmbH, part of Springer Nature

About this chapter

Starosta, K. (2022). Case Studies on Media Reporting and Media Influence During the COVID-19 Pandemic. In: Measuring the Impact of Online Media on Consumers, Businesses and Society. Sustainable Management, Wertschöpfung und Effizienz. Springer Gabler, Wiesbaden. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-36729-9_10

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-36729-9_10

Published : 03 March 2022

Publisher Name : Springer Gabler, Wiesbaden

Print ISBN : 978-3-658-36728-2

Online ISBN : 978-3-658-36729-9

eBook Packages : Business and Management Business and Management (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Follow us on Facebook

- Follow us on Twitter

- Criminal Justice

- Environment

- Politics & Government

- Race & Gender

Expert Commentary

Measuring the media agenda: How to research news coverage trends on topics

2014 study in Political Communication presenting recommendations for researchers studying news media agenda trends.

Republish this article

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License .

by Joanna Penn, The Journalist's Resource May 27, 2014

This <a target="_blank" href="https://journalistsresource.org/media/measuring-agenda-how-research-coverage-trends-topics/">article</a> first appeared on <a target="_blank" href="https://journalistsresource.org">The Journalist's Resource</a> and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.<img src="https://journalistsresource.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/cropped-jr-favicon-150x150.png" style="width:1em;height:1em;margin-left:10px;">

The amount of media coverage that different subjects receive can affect public knowledge and opinion on that issue, which in turn can influence policy makers and legislators , both in terms of setting the agenda and influencing its direction. Likewise, the more politicians and the public are concerned with certain subjects, the more likely they are to be covered in the media. The media’s ability to shape opinion in this way makes patterns of coverage a key variable in determining how the democratic system functions.

But what is a scientifically valid approach to discerning these patterns with precision? Many researchers point toward factors that encourage a single national media agenda, such as shared norms for news-worthiness, limited resources for newsgathering, and copycat propensities among journalists. If a single national news agenda exists for a topic, then studying one or two news sources to understand the media’s coverage of that topic is a valid approach. However, critics point out that a single source may have a particular set of influences that alter the amount of attention it gives to different issues, making it a poor proxy for the wider news agenda. Differences in print and broadcast media, for example, mean the former can cover more topics than the later, to which the availability of good visual images is also of greater importance. Other factors such as regional salience , and the need to appeal to different target audiences that advertisers wish to reach, may act against the formation of a single media agenda.

How to measure the tenor of media coverage on a particular issue — pinpointing consistent features that appear across news outlets — is a difficult task. One common technique used by university scholars and popular columnists alike is to employ keywords to search for a representative sample of articles in a database and then present the trends in the sample as representing the general media agenda. A 2014 study published in Political Communication , “ Measuring the Media Agenda ,” examines the conditions under which a single national media agenda emerges and those under which it does not. To do this, Mary Layton Atkinson of the University of North Carolina at Charlotte and John Lovett and Frank R. Baumgartner of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill conducted 90 different keyword searches covering a wide range of policy topics, on 12 national and regional media sources going back as far as the 1980s. Policy topics ranged from domestic issues such as Social Security, education and crime to international issues such as war and trade negotiations. The searches also included non-policy topics such as sports and natural disasters. The study is “empirically the most extensive study to date,” the researchers write.

The study’s findings include:

- Across the 90 different search topics, the presence of a single national news agenda could explain between 12 percent and 93 percent of the variance in the news coverage of that issue. In other words, on any given topic a consistent national media agenda can be obvious — or barely discernible.

- For each topic, across all sources, the average number of articles per month ranged from 1.7 to 687, with a median of around 60 stories a month.

- Topics with low levels of coverage, a maximum of around 23 articles per month, were not necessarily trivial or unimportant. They included subjects such as such as water pollution, farm subsidies, the unemployment rate, and racial discrimination.

- Issue salience is a key determinant of whether a national news agenda emerges on that topic. This can be understood in two ways: the amount of coverage a topic receives, on average over time, and when a subject receives an “attention spike” of high coverage for a short time.

- These two factors — average levels of coverage, and whether there is a spike in coverage — account for around 90% of the factors that predict whether a national media agenda exists for a particular subject or not.

- “Researchers studying low-salience issues, such as school prayer or food safety, for instance, should be wary of creating time series measures of media attention.”

If an issue is of high salience and receives consistently high levels of coverage or attention spikes, almost any major news source will show similar patterns in coverage. In such circumstances, using one or two news sources as a proxy for the wider media agenda would be appropriate, conclude authors Atkinson, Lovett and Baumgartner. For topics where there is low coverage and no spikes in attention, it is much less likely that there is a cohesive news agenda. In such cases not only would the use of a small sample of media as a proxy for a wider agenda be inappropriate, the construction of a wider news index would be unlikely to work either. Such an index may smooth differences across publications, but would be unlikely to represent an accurate picture of how any single person would consume such media, the study’s authors note.

One suggestion for further research relates to the construction of the keyword searches themselves, which can have a significant effect on results. Low hit rates produce data sets that are too small to be reliable. The study’s authors found surprisingly low numbers of results for issues that they would expect to be more prominent. Experimenting with the search terms may do more for the reliability of researchers’ results than the selection of media to use as a source: “Greater error likely creeps into any analysis based on poorly thought out or verified keyword searches than from the inclusion of any individual media source. For robust searches based on many hits, our analysis shows that a single media agenda is the rule.”

Keywords: news

About The Author

Joanna Penn

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 08 May 2024

Exploring the dynamics of consumer engagement in social media influencer marketing: from the self-determination theory perspective

- Chenyu Gu ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-6059-0573 1 &

- Qiuting Duan 2

Humanities and Social Sciences Communications volume 11 , Article number: 587 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

289 Accesses

2 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Business and management

- Cultural and media studies

Influencer advertising has emerged as an integral part of social media marketing. Within this realm, consumer engagement is a critical indicator for gauging the impact of influencer advertisements, as it encompasses the proactive involvement of consumers in spreading advertisements and creating value. Therefore, investigating the mechanisms behind consumer engagement holds significant relevance for formulating effective influencer advertising strategies. The current study, grounded in self-determination theory and employing a stimulus-organism-response framework, constructs a general model to assess the impact of influencer factors, advertisement information, and social factors on consumer engagement. Analyzing data from 522 samples using structural equation modeling, the findings reveal: (1) Social media influencers are effective at generating initial online traffic but have limited influence on deeper levels of consumer engagement, cautioning advertisers against overestimating their impact; (2) The essence of higher-level engagement lies in the ad information factor, affirming that in the new media era, content remains ‘king’; (3) Interpersonal factors should also be given importance, as influencing the surrounding social groups of consumers is one of the effective ways to enhance the impact of advertising. Theoretically, current research broadens the scope of both social media and advertising effectiveness studies, forming a bridge between influencer marketing and consumer engagement. Practically, the findings offer macro-level strategic insights for influencer marketing.

Similar content being viewed by others

Exploring the effects of audience and strategies used by beauty vloggers on behavioural intention towards endorsed brands

COBRAs and virality: viral campaign values on consumer behaviour

Exploring the impact of beauty vloggers’ credible attributes, parasocial interaction, and trust on consumer purchase intention in influencer marketing

Introduction.

Recent studies have highlighted an escalating aversion among audiences towards traditional online ads, leading to a diminishing effectiveness of traditional online advertising methods (Lou et al., 2019 ). In an effort to overcome these challenges, an increasing number of brands are turning to influencers as their spokespersons for advertising. Utilizing influencers not only capitalizes on their significant influence over their fan base but also allows for the dissemination of advertising messages in a more native and organic manner. Consequently, influencer-endorsed advertising has become a pivotal component and a growing trend in social media advertising (Gräve & Bartsch, 2022 ). Although the topic of influencer-endorsed advertising has garnered increasing attention from scholars, the field is still in its infancy, offering ample opportunities for in-depth research and exploration (Barta et al., 2023 ).

Presently, social media influencers—individuals with substantial follower bases—have emerged as the new vanguard in advertising (Hudders & Lou, 2023 ). Their tweets and videos possess the remarkable potential to sway the purchasing decisions of thousands if not millions. This influence largely hinges on consumer engagement behaviors, implying that the impact of advertising can proliferate throughout a consumer’s entire social network (Abbasi et al., 2023 ). Consequently, exploring ways to enhance consumer engagement is of paramount theoretical and practical significance for advertising effectiveness research (Xiao et al., 2023 ). This necessitates researchers to delve deeper into the exploration of the stimulating factors and psychological mechanisms influencing consumer engagement behaviors (Vander Schee et al., 2020 ), which is the gap this study seeks to address.

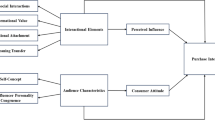

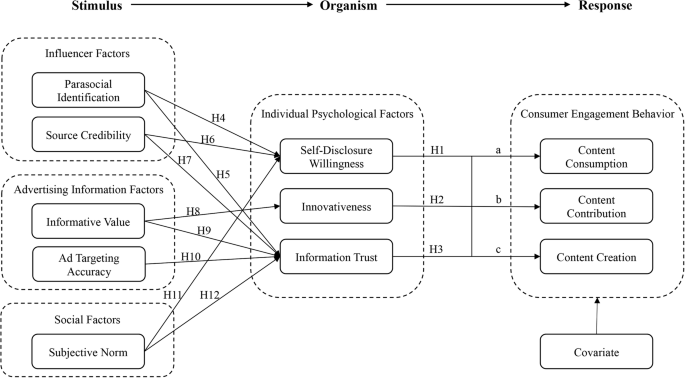

The Stimulus-Organism-Response (S-O-R) framework has been extensively applied in the study of consumer engagement behaviors (Tak & Gupta, 2021 ) and has been shown to integrate effectively with self-determination theory (Yang et al., 2019 ). Therefore, employing the S-O-R framework to investigate consumer engagement behaviors in the context of influencer advertising is considered a rational approach. The current study embarks on an in-depth analysis of the transformation process from three distinct dimensions. In the Stimulus (S) phase, we focus on how influencer factors, advertising message factors, and social influence factors act as external stimuli. This phase scrutinizes the external environment’s role in triggering consumer reactions. During the Organism (O) phase, the research explores the intrinsic psychological motivations affecting individual behavior as posited in self-determination theory. This includes the willingness for self-disclosure, the desire for innovation, and trust in advertising messages. The investigation in this phase aims to understand how these internal motivations shape consumer attitudes and perceptions in the context of influencer marketing. Finally, in the Response (R) phase, the study examines how these psychological factors influence consumer engagement behavior. This part of the research seeks to understand the transition from internal psychological states to actual consumer behavior, particularly how these states drive the consumers’ deep integration and interaction with the influencer content.

Despite the inherent limitations of cross-sectional analysis in capturing the full temporal dynamics of consumer engagement, this study seeks to unveil the dynamic interplay between consumers’ psychological needs—autonomy, competence, and relatedness—and their varying engagement levels in social media influencer marketing, grounded in self-determination theory. Through this lens, by analyzing factors related to influencers, content, and social context, we aim to infer potential dynamic shifts in engagement behaviors as psychological needs evolve. This approach allows us to offer a snapshot of the complex, multi-dimensional nature of consumer engagement dynamics, providing valuable insights for both theoretical exploration and practical application in the constantly evolving domain of social media marketing. Moreover, the current study underscores the significance of adapting to the dynamic digital environment and highlights the evolving nature of consumer engagement in the realm of digital marketing.

Literature review

Stimulus-organism-response (s-o-r) model.

The Stimulus-Response (S-R) model, originating from behaviorist psychology and introduced by psychologist Watson ( 1917 ), posits that individual behaviors are directly induced by external environmental stimuli. However, this model overlooks internal personal factors, complicating the explanation of psychological states. Mehrabian and Russell ( 1974 ) expanded this by incorporating the individual’s cognitive component (organism) into the model, creating the Stimulus-Organism-Response (S-O-R) framework. This model has become a crucial theoretical framework in consumer psychology as it interprets internal psychological cognitions as mediators between stimuli and responses. Integrating with psychological theories, the S-O-R model effectively analyzes and explains the significant impact of internal psychological factors on behavior (Koay et al., 2020 ; Zhang et al., 2021 ), and is extensively applied in investigating user behavior on social media platforms (Hewei & Youngsook, 2022 ). This study combines the S-O-R framework with self-determination theory to examine consumer engagement behaviors in the context of social media influencer advertising, a logic also supported by some studies (Yang et al., 2021 ).

Self-determination theory

Self-determination theory, proposed by Richard and Edward (2000), is a theoretical framework exploring human behavioral motivation and personality. The theory emphasizes motivational processes, positing that individual behaviors are developed based on factors satisfying their psychological needs. It suggests that individual behavioral tendencies are influenced by the needs for competence, relatedness, and autonomy. Furthermore, self-determination theory, along with organic integration theory, indicates that individual behavioral tendencies are also affected by internal psychological motivations and external situational factors.

Self-determination theory has been validated by scholars in the study of online user behaviors. For example, Sweet applied the theory to the investigation of community building in online networks, analyzing knowledge-sharing behaviors among online community members (Sweet et al., 2020 ). Further literature review reveals the applicability of self-determination theory to consumer engagement behaviors, particularly in the context of influencer marketing advertisements. Firstly, self-determination theory is widely applied in studying the psychological motivations behind online behaviors, suggesting that the internal and external motivations outlined within the theory might also apply to exploring consumer behaviors in influencer marketing scenarios (Itani et al., 2022 ). Secondly, although research on consumer engagement in the social media influencer advertising context is still in its early stages, some studies have utilized SDT to explore behaviors such as information sharing and electronic word-of-mouth dissemination (Astuti & Hariyawan, 2021 ). These behaviors, which are part of the content contribution and creation dimensions of consumer engagement, may share similarities in the underlying psychological motivational mechanisms. Thus, this study will build upon these foundations to construct the Organism (O) component of the S-O-R model, integrating insights from SDT to further understand consumer engagement in influencer marketing.

Consumer engagement

Although scholars generally agree at a macro level to define consumer engagement as the creation of additional value by consumers or customers beyond purchasing products, the specific categorization of consumer engagement varies in different studies. For instance, Simon and Tossan interpret consumer engagement as a psychological willingness to interact with influencers (Simon & Tossan, 2018 ). However, such a broad definition lacks precision in describing various levels of engagement. Other scholars directly use tangible metrics on social media platforms, such as likes, saves, comments, and shares, to represent consumer engagement (Lee et al., 2018 ). While this quantitative approach is not flawed and can be highly effective in practical applications, it overlooks the content aspect of engagement, contradicting the “content is king” principle of advertising and marketing. We advocate for combining consumer engagement with the content aspect, as content engagement not only generates more traces of consumer online behavior (Oestreicher-Singer & Zalmanson, 2013 ) but, more importantly, content contribution and creation are central to social media advertising and marketing, going beyond mere content consumption (Qiu & Kumar, 2017 ). Meanwhile, we also need to emphasize that engagement is not a fixed state but a fluctuating process influenced by ongoing interactions between consumers and influencers, mediated by the evolving nature of social media platforms and the shifting sands of consumer preferences (Pradhan et al., 2023 ). Consumer engagement in digital environments undergoes continuous change, reflecting a journey rather than a destination (Viswanathan et al., 2017 ).

The current study adopts a widely accepted definition of consumer engagement from existing research, offering operational feasibility and aligning well with the research objectives of this paper. Consumer engagement behaviors in the context of this study encompass three dimensions: content consumption, content contribution, and content creation (Muntinga et al., 2011 ). These dimensions reflect a spectrum of digital engagement behaviors ranging from low to high levels (Schivinski et al., 2016 ). Specifically, content consumption on social media platforms represents a lower level of engagement, where consumers merely click and read the information but do not actively contribute or create user-generated content. Some studies consider this level of engagement as less significant for in-depth exploration because content consumption, compared to other forms, generates fewer visible traces of consumer behavior (Brodie et al., 2013 ). Even in a study by Qiu and Kumar, it was noted that the conversion rate of content consumption is low, contributing minimally to the success of social media marketing (Qiu & Kumar, 2017 ).

On the other hand, content contribution, especially content creation, is central to social media marketing. When consumers comment on influencer content or share information with their network nodes, it is termed content contribution, representing a medium level of online consumer engagement (Piehler et al., 2019 ). Furthermore, when consumers actively upload and post brand-related content on social media, this higher level of behavior is referred to as content creation. Content creation represents the highest level of consumer engagement (Cheung et al., 2021 ). Although medium and high levels of consumer engagement are more valuable for social media advertising and marketing, this exploratory study still retains the content consumption dimension of consumer engagement behaviors.

Theoretical framework

Internal organism factors: self-disclosure willingness, innovativeness, and information trust.

In existing research based on self-determination theory that focuses on online behavior, competence, relatedness, and autonomy are commonly considered as internal factors influencing users’ online behaviors. However, this approach sometimes strays from the context of online consumption. Therefore, in studies related to online consumption, scholars often use self-disclosure willingness as an overt representation of autonomy, innovativeness as a representation of competence, and trust as a representation of relatedness (Mahmood et al., 2019 ).

The use of these overt variables can be logically explained as follows: According to self-determination theory, individuals with a higher level of self-determination are more likely to adopt compensatory mechanisms to facilitate behavior compared to those with lower self-determination (Wehmeyer, 1999 ). Self-disclosure, a voluntary act of sharing personal information with others, is considered a key behavior in the development of interpersonal relationships. In social environments, self-disclosure can effectively alleviate stress and build social connections, while also seeking societal validation of personal ideas (Altman & Taylor, 1973 ). Social networks, as para-social entities, possess the interactive attributes of real societies and are likely to exhibit similar mechanisms. In consumer contexts, personal disclosures can include voluntary sharing of product interests, consumption experiences, and future purchase intentions (Robertshaw & Marr, 2006 ). While material incentives can prompt personal information disclosure, many consumers disclose personal information online voluntarily, which can be traced back to an intrinsic need for autonomy (Stutzman et al., 2011 ). Thus, in this study, we consider the self-disclosure willingness as a representation of high autonomy.

Innovativeness refers to an individual’s internal level of seeking novelty and represents their personality and tendency for novelty (Okazaki, 2009 ). Often used in consumer research, innovative consumers are inclined to try new technologies and possess an intrinsic motivation to use new products. Previous studies have shown that consumers with high innovativeness are more likely to search for information on new products and share their experiences and expertise with others, reflecting a recognition of their own competence (Kaushik & Rahman, 2014 ). Therefore, in consumer contexts, innovativeness is often regarded as the competence dimension within the intrinsic factors of self-determination (Wang et al., 2016 ), with external motivations like information novelty enhancing this intrinsic motivation (Lee et al., 2015 ).

Trust refers to an individual’s willingness to rely on the opinions of others they believe in. From a social psychological perspective, trust indicates the willingness to assume the risk of being harmed by another party (McAllister, 1995 ). Widely applied in social media contexts for relational marketing, information trust has been proven to positively influence the exchange and dissemination of consumer information, representing a close and advanced relationship between consumers and businesses, brands, or advertising endorsers (Steinhoff et al., 2019 ). Consumers who trust brands or social media influencers are more willing to share information without fear of exploitation (Pop et al., 2022 ), making trust a commonly used representation of the relatedness dimension in self-determination within consumer contexts.

Construction of the path from organism to response: self-determination internal factors and consumer engagement behavior

Following the logic outlined above, the current study represents the internal factors of self-determination theory through three variables: self-disclosure willingness, innovativeness, and information trust. Next, the study explores the association between these self-determination internal factors and consumer engagement behavior, thereby constructing the link between Organism (O) and Response (R).

Self-disclosure willingness and consumer engagement behavior

In the realm of social sciences, the concept of self-disclosure willingness has been thoroughly examined from diverse disciplinary perspectives, encompassing communication studies, sociology, and psychology. Viewing from the lens of social interaction dynamics, self-disclosure is acknowledged as a fundamental precondition for the initiation and development of online social relationships and interactive engagements (Luo & Hancock, 2020 ). It constitutes an indispensable component within the spectrum of interactive behaviors and the evolution of interpersonal connections. Voluntary self-disclosure is characterized by individuals divulging information about themselves, which typically remains unknown to others and is inaccessible through alternative sources. This concept aligns with the tenets of uncertainty reduction theory, which argues that during interpersonal engagements, individuals seek information about their counterparts as a means to mitigate uncertainties inherent in social interactions (Lee et al., 2008 ). Self-disclosure allows others to gain more personal information, thereby helping to reduce the uncertainty in interpersonal relationships. Such disclosure is voluntary rather than coerced, and this sharing of information can facilitate the development of relationships between individuals (Towner et al., 2022 ). Furthermore, individuals who actively engage in social media interactions (such as liking, sharing, and commenting on others’ content) often exhibit higher levels of self-disclosure (Chu et al., 2023 ); additional research indicates a positive correlation between self-disclosure and online engagement behaviors (Lee et al., 2023 ). Taking the context of the current study, the autonomous self-disclosure willingness can incline social media users to read advertising content more attentively and share information with others, and even create evaluative content. Therefore, this paper proposes the following research hypothesis:

H1a: The self-disclosure willingness is positively correlated with content consumption in consumer engagement behavior.

H1b: The self-disclosure willingness is positively correlated with content contribution in consumer engagement behavior.

H1c: The self-disclosure willingness is positively correlated with content creation in consumer engagement behavior.

Innovativeness and consumer engagement behavior

Innovativeness represents an individual’s propensity to favor new technologies and the motivation to use new products, associated with the cognitive perception of one’s self-competence. Individuals with a need for self-competence recognition often exhibit higher innovativeness (Kelley & Alden, 2016 ). Existing research indicates that users with higher levels of innovativeness are more inclined to accept new product information and share their experiences and discoveries with others in their social networks (Yusuf & Busalim, 2018 ). Similarly, in the context of this study, individuals, as followers of influencers, signify an endorsement of the influencer. Driven by innovativeness, they may be more eager to actively receive information from influencers. If they find the information valuable, they are likely to share it and even engage in active content re-creation to meet their expectations of self-image. Therefore, this paper proposes the following research hypotheses:

H2a: The innovativeness of social media users is positively correlated with content consumption in consumer engagement behavior.

H2b: The innovativeness of social media users is positively correlated with content contribution in consumer engagement behavior.

H2c: The innovativeness of social media users is positively correlated with content creation in consumer engagement behavior.

Information trust and consumer engagement

Trust refers to an individual’s willingness to rely on the statements and opinions of a target object (Moorman et al., 1993 ). Extensive research indicates that trust positively impacts information dissemination and content sharing in interpersonal communication environments (Majerczak & Strzelecki, 2022 ); when trust is established, individuals are more willing to share their resources and less suspicious of being exploited. Trust has also been shown to influence consumers’ participation in community building and content sharing on social media, demonstrating cross-cultural universality (Anaya-Sánchez et al., 2020 ).

Trust in influencer advertising information is also a key predictor of consumers’ information exchange online. With many social media users now operating under real-name policies, there is an increased inclination to trust information shared on social media over that posted by corporate accounts or anonymously. Additionally, as users’ social networks partially overlap with their real-life interpersonal networks, extensive research shows that more consumers increasingly rely on information posted and shared on social networks when making purchase decisions (Wang et al., 2016 ). This aligns with the effectiveness goals of influencer marketing advertisements and the characteristics of consumer engagement. Trust in the content posted by influencers is considered a manifestation of a strong relationship between fans and influencers, central to relationship marketing (Kim & Kim, 2021 ). Based on trust in the influencer, which then extends to trust in their content, people are more inclined to browse information posted by influencers, share this information with others, and even create their own content without fear of exploitation or negative consequences. Therefore, this paper proposes the following research hypotheses:

H3a: Information trust is positively correlated with content consumption in consumer engagement behavior.

H3b: Information trust is positively correlated with content contribution in consumer engagement behavior.

H3c: Information trust is positively correlated with content creation in consumer engagement behavior.

Construction of the path from stimulus to organism: influencer factors, advertising information factors, social factors, and self-determination internal factors

Having established the logical connection from Organism (O) to Response (R), we further construct the influence path from Stimulus (S) to Organism (O). Revisiting the definition of influencer advertising in social media, companies, and brands leverage influencers on social media platforms to disseminate advertising content, utilizing the influencers’ relationships and influence over consumers for marketing purposes. In addition to consumer’s internal factors, elements such as companies, brands, influencers, and the advertisements themselves also impact consumer behavior. Although factors like the brand image perception of companies may influence consumer behavior, considering that in influencer marketing, companies and brands do not directly interact with consumers, this study prioritizes the dimensions of influencers and advertisements. Furthermore, the impact of social factors on individual cognition and behavior is significant, thus, the current study integrates influencers, advertisements, and social dimensions as the Stimulus (S) component.

Influencer factors: parasocial identification

Self-determination theory posits that relationships are one of the key motivators influencing individual behavior. In the context of social media research, users anticipate establishing a parasocial relationship with influencers, resembling real-life relationships. Hence, we consider the parasocial identification arising from users’ parasocial interactions with influencers as the relational motivator. Parasocial interaction refers to the one-sided personal relationship that individuals develop with media characters (Donald & Richard, 1956 ). During this process, individuals believe that the media character is directly communicating with them, creating a sense of positive intimacy (Giles, 2002 ). Over time, through repeated unilateral interactions with media characters, individuals develop a parasocial relationship, leading to parasocial identification. However, parasocial identification should not be directly equated with the concept of social identification in social identity theory. Social identification occurs when individuals psychologically de-individualize themselves, perceiving the characteristics of their social group as their own, upon identifying themselves as part of that group. In contrast, parasocial identification refers to the one-sided interactional identification with media characters (such as celebrities or influencers) over time (Chen et al., 2021 ). Particularly when individuals’ needs for interpersonal interaction are not met in their daily lives, they turn to parasocial interactions to fulfill these needs (Shan et al., 2020 ). Especially on social media, which is characterized by its high visibility and interactivity, users can easily develop a strong parasocial identification with the influencers they follow (Wei et al., 2022 ).

Parasocial identification and self-disclosure willingness

Theories like uncertainty reduction, personal construct, and social exchange are often applied to explain the emergence of parasocial identification. Social media, with its convenient and interactive modes of information dissemination, enables consumers to easily follow influencers on media platforms. They can perceive the personality of influencers through their online content, viewing them as familiar individuals or even friends. Once parasocial identification develops, this pleasurable experience can significantly influence consumers’ cognitions and thus their behavioral responses. Research has explored the impact of parasocial identification on consumer behavior. For instance, Bond et al. found that on Twitter, the intensity of users’ parasocial identification with influencers positively correlates with their continuous monitoring of these influencers’ activities (Bond, 2016 ). Analogous to real life, where we tend to pay more attention to our friends in our social networks, a similar phenomenon occurs in the relationship between consumers and brands. This type of parasocial identification not only makes consumers willing to follow brand pages but also more inclined to voluntarily provide personal information (Chen et al., 2021 ). Based on this logic, we speculate that a similar relationship may exist between social media influencers and their fans. Fans develop parasocial identification with influencers through social media interactions, making them more willing to disclose their information, opinions, and views in the comment sections of the influencers they follow, engaging in more frequent social interactions (Chung & Cho, 2017 ), even if the content at times may be brand or company-embedded marketing advertisements. In other words, in the presence of influencers with whom they have established parasocial relationships, they are more inclined to disclose personal information, thereby promoting consumer engagement behavior. Therefore, we propose the following research hypotheses:

H4: Parasocial identification is positively correlated with consumer self-disclosure willingness.

H4a: Self-disclosure willingness mediates the impact of parasocial identification on content consumption in consumer engagement behavior.

H4b: Self-disclosure willingness mediates the impact of parasocial identification on content contribution in consumer engagement behavior.

H4c: Self-disclosure willingness mediates the impact of parasocial identification on content creation in consumer engagement behavior.

Parasocial identification and information trust

Information Trust refers to consumers’ willingness to trust the information contained in advertisements and to place themselves at risk. These risks include purchasing products inconsistent with the advertised information and the negative social consequences of erroneously spreading this information to others, leading to unpleasant consumption experiences (Minton, 2015 ). In advertising marketing, gaining consumers’ trust in advertising information is crucial. In the context of influencer marketing on social media, companies, and brands leverage the social connection between influencers and their fans. According to cognitive empathy theory, consumers project their trust in influencers onto the products endorsed, explaining the phenomenon of ‘loving the house for the crow on its roof.’ Research indicates that parasocial identification with influencers is a necessary condition for trust development. Consumers engage in parasocial interactions with influencers on social media, leading to parasocial identification (Jin et al., 2021 ). Consumers tend to reduce their cognitive load and simplify their decision-making processes, thus naturally adopting a positive attitude and trust towards advertising information disseminated by influencers with whom they have established parasocial identification. This forms the core logic behind the success of influencer marketing advertisements (Breves et al., 2021 ); furthermore, as mentioned earlier, because consumers trust these advertisements, they are also willing to share this information with friends and family and even engage in content re-creation. Therefore, we propose the following research hypotheses:

H5: Parasocial identification is positively correlated with information trust.

H5a: Information trust mediates the impact of parasocial identification on content consumption in consumer engagement behavior.

H5b: Information trust mediates the impact of parasocial identification on content contribution in consumer engagement behavior.

H5c: Information trust mediates the impact of parasocial identification on content creation in consumer engagement behavior.

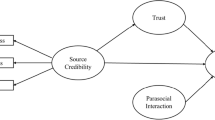

Influencer factors: source credibility

Source credibility refers to the degree of trust consumers place in the influencer as a source, based on the influencer’s reliability and expertise. Numerous studies have validated the effectiveness of the endorsement effect in advertising (Schouten et al., 2021 ). The Source Credibility Model, proposed by the renowned American communication scholar Hovland and the “Yale School,” posits that in the process of information dissemination, the credibility of the source can influence the audience’s decision to accept the information. The credibility of the information is determined by two aspects of the source: reliability and expertise. Reliability refers to the audience’s trust in the “communicator’s objective and honest approach to providing information,” while expertise refers to the audience’s trust in the “communicator being perceived as an effective source of information” (Hovland et al., 1953 ). Hovland’s definitions reveal that the interpretation of source credibility is not about the inherent traits of the source itself but rather the audience’s perception of the source (Jang et al., 2021 ). This differs from trust and serves as a precursor to the development of trust. Specifically, reliability and expertise are based on the audience’s perception; thus, this aligns closely with the audience’s perception of influencers (Kim & Kim, 2021 ). This credibility is a cognitive statement about the source of information.

Source credibility and self-disclosure willingness

Some studies have confirmed the positive impact of an influencer’s self-disclosure on their credibility as a source (Leite & Baptista, 2022 ). However, few have explored the impact of an influencer’s credibility, as a source, on consumers’ self-disclosure willingness. Undoubtedly, an impact exists; self-disclosure is considered a method to attempt to increase intimacy with others (Leite et al., 2022 ). According to social exchange theory, people promote relationships through the exchange of information in interpersonal communication to gain benefits (Cropanzano & Mitchell, 2005 ). Credibility, deriving from an influencer’s expertise and reliability, means that a highly credible influencer may provide more valuable information to consumers. Therefore, based on the social exchange theory’s logic of reciprocal benefits, consumers might be more willing to disclose their information to trustworthy influencers, potentially even expanding social interactions through further consumer engagement behaviors. Thus, we propose the following research hypotheses:

H6: Source credibility is positively correlated with self-disclosure willingness.

H6a: Self-disclosure willingness mediates the impact of Source credibility on content consumption in consumer engagement behavior.

H6b: Self-disclosure willingness mediates the impact of Source credibility on content contribution in consumer engagement behavior.

H6c: Self-disclosure willingness mediates the impact of Source credibility on content creation in consumer engagement behavior.

Source credibility and information trust

Based on the Source Credibility Model, the credibility of an endorser as an information source can significantly influence consumers’ acceptance of the information (Shan et al., 2020 ). Existing research has demonstrated the positive impact of source credibility on consumers. Djafarova, in a study based on Instagram, noted through in-depth interviews with 18 users that an influencer’s credibility significantly affects respondents’ trust in the information they post. This credibility is composed of expertise and relevance to consumers, and influencers on social media are considered more trustworthy than traditional celebrities (Djafarova & Rushworth, 2017 ). Subsequently, Bao and colleagues validated in the Chinese consumer context, based on the ELM model and commitment-trust theory, that the credibility of brand pages on Weibo effectively fosters consumer trust in the brand, encouraging participation in marketing activities (Bao & Wang, 2021 ). Moreover, Hsieh et al. found that in e-commerce contexts, the credibility of the source is a significant factor influencing consumers’ trust in advertising information (Hsieh & Li, 2020 ). In summary, existing research has proven that the credibility of the source can promote consumer trust. Influencer credibility is a significant antecedent affecting consumers’ trust in the advertised content they publish. In brand communities, trust can foster consumer engagement behaviors (Habibi et al., 2014 ). Specifically, consumers are more likely to trust the advertising content published by influencers with higher credibility (more expertise and reliability), and as previously mentioned, consumer engagement behavior is more likely to occur. Based on this, the study proposes the following research hypotheses:

H7: Source credibility is positively correlated with information trust.

H7a: Information trust mediates the impact of source credibility on content consumption in consumer engagement behavior.

H7b: Information trust mediates the impact of source credibility on content contribution in consumer engagement behavior.

H7c: Information trust mediates the impact of source credibility on content creation in consumer engagement behavior.

Advertising information factors: informative value

Advertising value refers to “the relative utility value of advertising information to consumers and is a subjective evaluation by consumers.” In his research, Ducoffe pointed out that in the context of online advertising, the informative value of advertising is a significant component of advertising value (Ducoffe, 1995 ). Subsequent studies have proven that consumers’ perception of advertising value can effectively promote their behavioral response to advertisements (Van-Tien Dao et al., 2014 ). Informative value of advertising refers to “the information about products needed by consumers provided by the advertisement and its ability to enhance consumer purchase satisfaction.” From the perspective of information dissemination, valuable advertising information should help consumers make better purchasing decisions and reduce the effort spent searching for product information. The informational aspect of advertising has been proven to effectively influence consumers’ cognition and, in turn, their behavior (Haida & Rahim, 2015 ).

Informative value and innovativeness

As previously discussed, consumers’ innovativeness refers to their psychological trait of favoring new things. Studies have shown that consumers with high innovativeness prefer novel and valuable product information, as it satisfies their need for newness and information about new products, making it an important factor in social media advertising engagement (Shi, 2018 ). This paper also hypothesizes that advertisements with high informative value can activate consumers’ innovativeness, as the novelty of information is one of the measures of informative value (León et al., 2009 ). Acquiring valuable information can make individuals feel good about themselves and fulfill their perception of a “novel image.” According to social exchange theory, consumers can gain social capital in interpersonal interactions (such as social recognition) by sharing information about these new products they perceive as valuable. Therefore, the current study proposes the following research hypothesis:

H8: Informative value is positively correlated with innovativeness.

H8a: Innovativeness mediates the impact of informative value on content consumption in consumer engagement behavior.

H8b: Innovativeness mediates the impact of informative value on content contribution in consumer engagement behavior.

H8c: Innovativeness mediates the impact of informative value on content creation in consumer engagement behavior.

Informative value and information trust

Trust is a multi-layered concept explored across various disciplines, including communication, marketing, sociology, and psychology. For the purposes of this paper, a deep analysis of different levels of trust is not undertaken. Here, trust specifically refers to the trust in influencer advertising information within the context of social media marketing, denoting consumers’ belief in and reliance on the advertising information endorsed by influencers. Racherla et al. investigated the factors influencing consumers’ trust in online reviews, suggesting that information quality and value contribute to increasing trust (Racherla et al., 2012 ). Similarly, Luo and Yuan, in a study based on social media marketing, also confirmed that the value of advertising information posted on brand pages can foster consumer trust in the content (Lou & Yuan, 2019 ). Therefore, by analogy, this paper posits that the informative value of influencer-endorsed advertising can also promote consumer trust in that advertising information. The relationship between trust in advertising information and consumer engagement behavior has been discussed earlier. Thus, the current study proposes the following research hypotheses:

H9: Informative value is positively correlated with information trust.

H9a: Information trust mediates the impact of informative value on content consumption in consumer engagement behavior.

H9b: Information trust mediates the impact of informative value on content contribution in consumer engagement behavior.

H9c: Information trust mediates the impact of informative value on content creation in consumer engagement behavior.

Advertising information factors: ad targeting accuracy

Ad targeting accuracy refers to the degree of match between the substantive information contained in advertising content and consumer needs. Advertisements containing precise information often yield good advertising outcomes. In marketing practice, advertisers frequently use information technology to analyze the characteristics of different consumer groups in the target market and then target their advertisements accordingly to achieve precise dissemination and, consequently, effective advertising results. The utility of ad targeting accuracy has been confirmed by many studies. For instance, in the research by Qiu and Chen, using a modified UTAUT model, it was demonstrated that the accuracy of advertising effectively promotes consumer acceptance of advertisements in WeChat Moments (Qiu & Chen, 2018 ). Although some studies on targeted advertising also indicate that overly precise ads may raise concerns about personal privacy (Zhang et al., 2019 ), overall, the accuracy of advertising information is effective in enhancing advertising outcomes and is a key element in the success of targeted advertising.

Ad targeting accuracy and information trust

In influencer marketing advertisements, due to the special relationship recognition between consumers and influencers, the privacy concerns associated with ad targeting accuracy are alleviated (Vrontis et al., 2021 ). Meanwhile, the informative value brought by targeting accuracy is highlighted. More precise advertising content implies higher informative value and also signifies that the advertising content is more worthy of consumer trust (Della Vigna, Gentzkow, 2010 ). As previously discussed, people are more inclined to read and engage with advertising content they trust and recognize. Therefore, the current study proposes the following research hypotheses:

H10: Ad targeting accuracy is positively correlated with information trust.

H10a: Information trust mediates the impact of ad targeting accuracy on content consumption in consumer engagement behavior.

H10b: Information trust mediates the impact of ad targeting accuracy on content contribution in consumer engagement behavior.

H10c: Information trust mediates the impact of ad targeting accuracy on content creation in consumer engagement behavior.

Social factors: subjective norm

The Theory of Planned Behavior, proposed by Ajzen ( 1991 ), suggests that individuals’ actions are preceded by conscious choices and are underlain by plans. TPB has been widely used by scholars in studying personal online behaviors, these studies collectively validate the applicability of TPB in the context of social media for researching online behaviors (Huang, 2023 ). Additionally, the self-determination theory, which underpins this chapter’s research, also supports the notion that individuals’ behavioral decisions are based on internal cognitions, aligning with TPB’s assertions. Therefore, this paper intends to select subjective norms from TPB as a factor of social influence. Subjective norm refers to an individual’s perception of the expectations of significant others in their social relationships regarding their behavior. Empirical research in the consumption field has demonstrated the significant impact of subjective norms on individual psychological cognition (Yang & Jolly, 2009 ). A meta-analysis by Hagger, Chatzisarantis ( 2009 ) even highlighted the statistically significant association between subjective norms and self-determination factors. Consequently, this study further explores its application in the context of influencer marketing advertisements on social media.

Subjective norm and self-disclosure willingness

In numerous studies on social media privacy, subjective norms significantly influence an individual’s self-disclosure willingness. Wirth et al. ( 2019 ) based on the privacy calculus theory, surveyed 1,466 participants and found that personal self-disclosure on social media is influenced by the behavioral expectations of other significant reference groups around them. Their research confirmed that subjective norms positively influence self-disclosure of information and highlighted that individuals’ cognitions and behaviors cannot ignore social and environmental factors. Heirman et al. ( 2013 ) in an experiment with Instagram users, also noted that subjective norms could promote positive consumer behavioral responses. Specifically, when important family members and friends highly regard social media influencers as trustworthy, we may also be more inclined to disclose our information to influencers and share this information with our surrounding family and friends without fear of disapproval. In our subjective norms, this is considered a positive and valuable interactive behavior, leading us to exhibit engagement behaviors. Based on this logic, we propose the following research hypotheses:

H11: Subjective norms are positively correlated with self-disclosure willingness.

H11a: Self-disclosure willingness mediates the impact of subjective norms on content consumption in consumer engagement behavior.

H11b: Self-disclosure willingness mediates the impact of subjective norms on content contribution in consumer engagement behavior.

H11c: Self-disclosure willingness mediates the impact of subjective norms on content creation in consumer engagement behavior.

Subjective norm and information trust

Numerous studies have indicated that subjective norms significantly influence trust (Roh et al., 2022 ). This can be explained by reference group theory, suggesting people tend to minimize the effort expended in decision-making processes, often looking to the behaviors or attitudes of others as a point of reference; for instance, subjective norms can foster acceptance of technology by enhancing trust (Gupta et al., 2021 ). Analogously, if a consumer’s social network generally holds positive attitudes toward influencer advertising, they are also more likely to trust the endorsed advertisement information, as it conserves the extensive effort required in gathering product information (Chetioui et al., 2020 ). Therefore, this paper proposes the following research hypotheses:

H12: Subjective norms are positively correlated with information trust.

H12a: Information trust mediates the impact of subjective norms on content consumption in consumer engagement behavior.

H12b: Information trust mediates the impact of subjective norms on content contribution in consumer engagement behavior.

H12c: Information trust mediates the impact of subjective norms on content creation in consumer engagement behavior.

Conceptual model

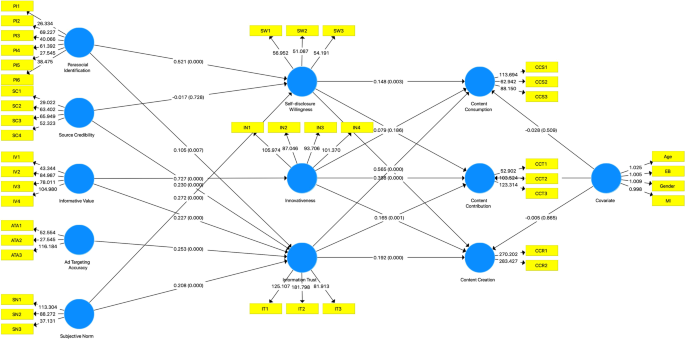

In summary, based on the Stimulus (S)-Organism (O)-Response (R) framework, this study constructs the external stimulus factors (S) from three dimensions: influencer factors (parasocial identification, source credibility), advertising information factors (informative value, Ad targeting accuracy), and social influence factors (subjective norms). This is grounded in social capital theory and the theory of planned behavior. drawing on self-determination theory, the current study constructs the individual psychological factors (O) using self-disclosure willingness, innovativeness, and information trust. Finally, the behavioral response (R) is constructed using consumer engagement, which includes content consumption, content contribution, and content creation, as illustrated in Fig. 1 .

Consumer engagement behavior impact model based on SOR framework.

Materials and methods

Participants and procedures.

The current study conducted a survey through the Wenjuanxing platform to collect data. Participants were recruited through social media platforms such as WeChat, Douyin, Weibo et al., as samples drawn from social media users better align with the research purpose of our research and ensure the validity of the sample. Before the survey commenced, all participants were explicitly informed about the purpose of this study, and it was made clear that volunteers could withdraw from the survey at any time. Initially, 600 questionnaires were collected, with 78 invalid responses excluded. The criteria for valid questionnaires were as follows: (1) Respondents must have answered “Yes” to the question, “Do you follow any influencers (internet celebrities) on social media platforms?” as samples not using social media or not following influencers do not meet the study’s objective, making this question a prerequisite for continuing the survey; (2) Respondents had to correctly answer two hidden screening questions within the questionnaire to ensure that they did not randomly select scores; (3) The total time taken to complete the questionnaire had to exceed one minute, ensuring that respondents had sufficient time to understand and thoughtfully answer each question; (4) Respondents were not allowed to choose the same score for eight consecutive questions. Ultimately, 522 valid questionnaires were obtained, with an effective rate of 87.00%, meeting the basic sample size requirements for research models (Gefen et al., 2011 ). Detailed demographic information of the study participants is presented in Table 1 .

Measurements

To ensure the validity and reliability of the data analysis results in this study, the measurement tools and scales used in this chapter were designed with reference to existing established research. The main variables in the survey questionnaire include parasocial identification, source credibility, informative value, ad targeting accuracy, subjective norms, self-disclosure willingness, innovativeness, information trust, content consumption, content contribution, and content creation. The measurement scale for parasocial identification was adapted from the research of Schramm and Hartmann, comprising 6 items (Schramm & Hartmann, 2008 ). The source credibility scale was combined from the studies of Cheung et al. and Luo & Yuan’s research in the context of social media influencer marketing, including 4 items (Cheung et al., 2009 ; Lou & Yuan, 2019 ). The scale for informative value was modified based on Voss et al.‘s research, consisting of 4 items (Voss et al., 2003 ). The ad targeting accuracy scale was derived from the research by Qiu Aimei et al., 2018 ) including 3 items. The subjective norm scale was adapted from Ajzen’s original scale, comprising 3 items (Ajzen, 2002 ). The self-disclosure willingness scale was developed based on Chu and Kim’s research, including 3 items (Chu & Kim, 2011 ). The innovativeness scale was formulated following the study by Sun et al., comprising 4 items (Sun et al., 2006 ). The information trust scale was created in reference to Chu and Choi’s research, including 3 items (Chu & Choi, 2011 ). The scales for the three components of social media consumer engagement—content consumption, content contribution, and content creation—were sourced from the research by Buzeta et al., encompassing 8 items in total (Buzeta et al., 2020 ).

All scales were appropriately revised for the context of social media influencer marketing. To avoid issues with scoring neutral attitudes, a uniform Likert seven-point scale was used for each measurement item (ranging from 1 to 7, representing a spectrum from ‘strongly disagree’ to ‘strongly agree’). After the overall design of the questionnaire was completed, a pre-test was conducted with 30 social media users to ensure that potential respondents could clearly understand the meaning of each question and that there were no obstacles to answering. This pre-test aimed to prevent any difficulties or misunderstandings in the questionnaire items. The final version of the questionnaire is presented in Table 2 .

Data analysis

Since the model framework of the current study is derived from theoretical deductions of existing research and, while logically constructed, does not originate from an existing research model, this study still falls under the category of exploratory research. According to the analysis suggestions of Hair and other scholars, in cases of exploratory research model frameworks, it is more appropriate to choose Smart PLS for Partial Least Squares Path Analysis (PLS) to conduct data analysis and testing of the research model (Hair et al., 2012 ).

Measurement of model

In this study, careful data collection and management resulted in no missing values in the dataset. This ensured the integrity and reliability of the subsequent data analysis. As shown in Table 3 , after deleting measurement items with factor loadings below 0.5, the final factor loadings of the measurement items in this study range from 0.730 to 0.964. This indicates that all measurement items meet the retention criteria. Additionally, the Cronbach’s α values of the latent variables range from 0.805 to 0.924, and all latent variables have Composite Reliability (CR) values greater than the acceptable value of 0.7, demonstrating that the scales of this study have passed the reliability test requirements (Hair et al., 2019 ). All latent variables in this study have Average Variance Extracted (AVE) values greater than the standard acceptance value of 0.5, indicating that the convergent validity of the variables also meets the standard (Fornell & Larcker, 1981 ). Furthermore, the results show that the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) values for each factor are below 10, indicating that there are no multicollinearity issues with the scales in this study (Hair, 2009 ).

The current study then further verified the discriminant validity of the variables, with specific results shown in Table 4 . The square roots of the average variance extracted (AVE) values for all variables (bolded on the diagonal) are greater than the Pearson correlation coefficients between the variables, indicating that the discriminant validity of the scales in this study meets the required standards (Fornell & Larcker, 1981 ). Additionally, a single-factor test method was employed to examine common method bias in the data. The first unrotated factor accounted for 29.71% of the variance, which is less than the critical threshold of 40%. Therefore, the study passed the test and did not exhibit serious common method bias (Podsakoff et al., 2003 ).

To ensure the robustness and appropriateness of our structural equation model, we also conducted a thorough evaluation of the model fit. Initially, through PLS Algorithm calculations, the R 2 values of each variable were greater than the standard acceptance value of 0.1, indicating good predictive accuracy of the model. Subsequently, Blindfolding calculations were performed, and the results showed that the Stone-Geisser Q 2 values of each variable were greater than 0, demonstrating that the model of this study effectively predicts the relationships between variables (Dijkstra & Henseler, 2015 ). In addition, through CFA, we also obtained some indicator values, specifically, χ 2 /df = 2.528 < 0.3, RMSEA = 0.059 < 0.06, SRMR = 0.055 < 0.08. Given its sensitivity to sample size, we primarily focused on the CFI, TLI, and NFI values, CFI = 0.953 > 0.9, TLI = 0.942 > 0.9, and NFI = 0.923 > 0.9 indicating a good fit. Additionally, RMSEA values below 0.06 and SRMR values below 0.08 were considered indicative of a good model fit. These indices collectively suggested that our model demonstrates a satisfactory fit with the data, thereby reinforcing the validity of our findings.

Research hypothesis testing