Social and scientific relevance of your thesis

Explanations & examples, starting your thesis.

- Start writing your thesis

View our services

Language check

Have your thesis or report reviewed for language, structure, coherence, and layout.

Plagiarism check

Check for free if your document contains plagiarism.

APA-generator

Create your reference list in APA style effortlessly. Completely free of charge.

What does the relevance of your thesis mean?

Social relevance thesis, scientific relevance thesis, practical relevance thesis, sample relevance thesis, we are happy to review your thesis.

It is important that your thesis topic is relevant. That means it is useful for society, for science and/or for practice. Therefore, when choosing a thesis topic, also look at the relevance of your subject. Also, dedicate a paragraph in your introduction to the relevance of your thesis. Read below what to look out for.

The outcomes of your thesis should be interesting and useful to others in one or more ways. People should be able to do something with it: in practice, in science and/or in society.

You explain the relevance of your thesis in the introduction and address this in your plan of action.

A thesis topic can be relevant in several ways. For instance, your chosen topic should be relevant to your study field and your possible client. In addition, there are three types of relevance:

- social relevance of your thesis;

- scientific relevance of your thesis;

- practical relevance of your thesis.

For practical theses, practical and social relevance are usually the most important. For university theses, scientific relevance can also be very important and practical relevance is not always as important. Your thesis supervisor can tell you what to pay more attention to in your thesis.

Besides choosing a relevant topic, your thesis topic must meet certain requirements . Furthermore, make sure you demarcate the topic properly.

A socially relevant thesis topic is useful to society. You help find a solution to a social problem or provide insight into a current issue with your thesis research.

For example, we speak of social relevance when...

- ... your research leads to recommendations for a problem solution.

- ... when your research explores a current social issue.

- ... if your research shows whether or not a particular method contributes to an important social solution.

- ... when you figure out what underlies a particular problem.

- ... when you gauge people's opinions on a topic to learn more about it.

In addition, your thesis may be academically relevant. This applies especially to theses written for a university course. The scientific relevance of your thesis means that your research complements existing scientific literature. You supplement the literature with new knowledge on a particular topic.

To choose a scientifically relevant topic, first, delve into available literature. What has already been researched? What are possible gaps in the literature?

We may speak of the scientific relevance of your thesis if e.g.

- ... you highlight a specific aspect of a topic that has not yet been researched.

- ... if you build on the suggestions for follow-up research in previous studies.

- ... if you use a new research method to investigate a particular topic.

Are you writing your thesis for a client? In that case, the practical relevance of your thesis is important. Even if you are writing your thesis for your study programme, practical relevance is sometimes important.

There is practical relevance if your thesis leads to recommendations or insights that are useful to practitioners (a profession, industry, organisation, etc.).

Suppose you are writing a thesis for a GP practice on more effective education on diabetes for overweight patients. In this case, the results of your research will be relevant for the staff of this GP practice. Other GP practices may also benefit.

In the introduction of your thesis, you briefly note what makes your thesis topic relevant. This example shows how to describe the relevance of your thesis.

This study is practically relevant because the results will help GP practice Jansen to improve their education on diabetes. This will make it more appealing for the target group to attend this information evening and allow the practice to motivate more patients to start losing weight and thus prevent diabetes.

The recommendations arising from the study are also relevant for other GPs in the Netherlands and diabetes prevention in general. Obesity is a major contributor to type 2 diabetes, a disease currently affecting over X Dutch people. The more people are aware of the link between obesity and type 2 diabetes, the more we can prevent it from reaching that point in obese people.

Furthermore, this study is scientifically relevant because little research has been done on diabetes education in the form of presentations by GPs. Previously, leaflets and brochures on this disease have been studied, but little is known about presentations. This study contributes to the knowledge on this topic, providing a more complete picture of effective education about type 2 diabetes.

The relevance of your thesis is one of the many things you need to formulate correctly in your thesis. Do you doubt whether your thesis is well put together in terms of structure, argumentation, language and spelling? Have our experienced editors review your thesis and give you personal feedback.

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Research process

- Relevance of Your Dissertation Topic | Criteria & Tips

Relevance of Your Dissertation Topic | Criteria & Tips

Published on 16 November 2022 by Sarah Vinz .

A relevant dissertation topic means that your research will contribute something worthwhile to your field in a scientific, social, or practical way.

As you plan out your dissertation process , make sure that you’re writing something that is important and interesting to you personally, as well as appropriate within your field.

If you’re a bit stuck on where to begin, consider framing your questions in terms of their relevance: scientifically to your discipline, socially to the world at large, or practically to an industry or organisation.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Be assured that you'll submit flawless writing. Upload your document to correct all your mistakes.

Table of contents

Scientific relevance, social and practical relevance, frequently asked questions about relevance.

If you are studying hard or social sciences, the scientific relevance of your dissertation is crucial. Your research should fill a gap in existing scientific knowledge, something that hasn’t been extensively studied before.

One way to find a relevant topic is to look at the recommendations for follow-up studies that are made in existing scientific articles and the works they cite. From there, you can pursue quantitative research , statistical analyses , or the relevant methodology for the type of research you choose to undertake.

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

Most theses are required to have social relevance, which basically means that they help us to better understand society. These can use ethnographies , interviews , or other types of field work to collect data

However, in some disciplines it may be more important that a dissertation have practical relevance. Research that has practical relevance adds value. For instance, it could make a recommendation for a particular industry or suggest ways to improve certain processes within an organisation.

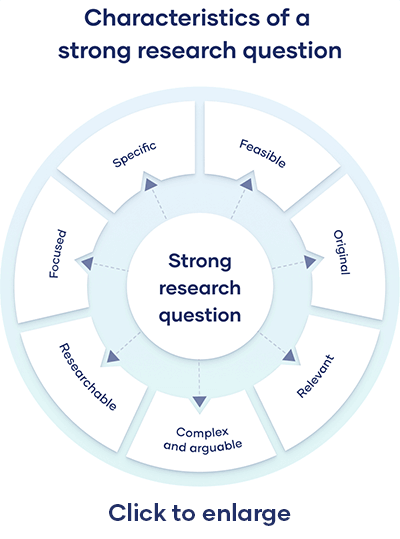

Formulating a main research question can be a difficult task. Overall, your question should contribute to solving the problem that you have defined in your problem statement .

However, it should also fulfill criteria in three main areas:

- Researchability

- Feasibility and specificity

- Relevance and originality

All research questions should be:

- Focused on a single problem or issue

- Researchable using primary and/or secondary sources

- Feasible to answer within the timeframe and practical constraints

- Specific enough to answer thoroughly

- Complex enough to develop the answer over the space of a paper or thesis

- Relevant to your field of study and/or society more broadly

You can assess information and arguments critically by asking certain questions about the source. You can use the CRAAP test , focusing on the currency , relevance , authority , accuracy , and purpose of a source of information.

Ask questions such as:

- Who is the author? Are they an expert?

- Why did the author publish it? What is their motivation?

- How do they make their argument? Is it backed up by evidence?

A dissertation prospectus or proposal describes what or who you plan to research for your dissertation. It delves into why, when, where, and how you will do your research, as well as helps you choose a type of research to pursue. You should also determine whether you plan to pursue qualitative or quantitative methods and what your research design will look like.

It should outline all of the decisions you have taken about your project, from your dissertation topic to your hypotheses and research objectives , ready to be approved by your supervisor or committee.

Note that some departments require a defense component, where you present your prospectus to your committee orally.

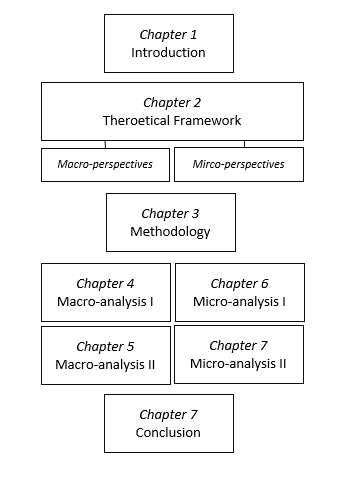

A thesis or dissertation outline is one of the most critical first steps in your writing process. It helps you to lay out and organise your ideas and can provide you with a roadmap for deciding what kind of research you’d like to undertake.

Generally, an outline contains information on the different sections included in your thesis or dissertation, such as:

- Your anticipated title

- Your abstract

- Your chapters (sometimes subdivided into further topics like literature review, research methods, avenues for future research, etc.)

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

Vinz, S. (2022, November 16). Relevance of Your Dissertation Topic | Criteria & Tips. Scribbr. Retrieved 21 May 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/the-research-process/dissertation-relevance/

Is this article helpful?

Sarah's academic background includes a Master of Arts in English, a Master of International Affairs degree, and a Bachelor of Arts in Political Science. She loves the challenge of finding the perfect formulation or wording and derives much satisfaction from helping students take their academic writing up a notch.

Other students also liked

Dissertation & thesis outline | example & free templates, how to choose a dissertation topic | 8 steps to follow, checklist: writing a dissertation.

How to write a fantastic thesis introduction (+15 examples)

The thesis introduction, usually chapter 1, is one of the most important chapters of a thesis. It sets the scene. It previews key arguments and findings. And it helps the reader to understand the structure of the thesis. In short, a lot is riding on this first chapter. With the following tips, you can write a powerful thesis introduction.

Disclosure: This post may contain affiliate links, which means I may earn a small commission if you make a purchase using the links below at no additional cost to you . I only recommend products or services that I truly believe can benefit my audience. As always, my opinions are my own.

Elements of a fantastic thesis introduction

Open with a (personal) story, begin with a problem, define a clear research gap, describe the scientific relevance of the thesis, describe the societal relevance of the thesis, write down the thesis’ core claim in 1-2 sentences, support your argument with sufficient evidence, consider possible objections, address the empirical research context, give a taste of the thesis’ empirical analysis, hint at the practical implications of the research, provide a reading guide, briefly summarise all chapters to come, design a figure illustrating the thesis structure.

An introductory chapter plays an integral part in every thesis. The first chapter has to include quite a lot of information to contextualise the research. At the same time, a good thesis introduction is not too long, but clear and to the point.

A powerful thesis introduction does the following:

- It captures the reader’s attention.

- It presents a clear research gap and emphasises the thesis’ relevance.

- It provides a compelling argument.

- It previews the research findings.

- It explains the structure of the thesis.

In addition, a powerful thesis introduction is well-written, logically structured, and free of grammar and spelling errors. Reputable thesis editors can elevate the quality of your introduction to the next level. If you are in search of a trustworthy thesis or dissertation editor who upholds high-quality standards and offers efficient turnaround times, I recommend the professional thesis and dissertation editing service provided by Editage .

This list can feel quite overwhelming. However, with some easy tips and tricks, you can accomplish all these goals in your thesis introduction. (And if you struggle with finding the right wording, have a look at academic key phrases for introductions .)

Ways to capture the reader’s attention

A powerful thesis introduction should spark the reader’s interest on the first pages. A reader should be enticed to continue reading! There are three common ways to capture the reader’s attention.

An established way to capture the reader’s attention in a thesis introduction is by starting with a story. Regardless of how abstract and ‘scientific’ the actual thesis content is, it can be useful to ease the reader into the topic with a short story.

This story can be, for instance, based on one of your study participants. It can also be a very personal account of one of your own experiences, which drew you to study the thesis topic in the first place.

Start by providing data or statistics

Data and statistics are another established way to immediately draw in your reader. Especially surprising or shocking numbers can highlight the importance of a thesis topic in the first few sentences!

So if your thesis topic lends itself to being kick-started with data or statistics, you are in for a quick and easy way to write a memorable thesis introduction.

The third established way to capture the reader’s attention is by starting with the problem that underlies your thesis. It is advisable to keep the problem simple. A few sentences at the start of the chapter should suffice.

Usually, at a later stage in the introductory chapter, it is common to go more in-depth, describing the research problem (and its scientific and societal relevance) in more detail.

You may also like: Minimalist writing for a better thesis

Emphasising the thesis’ relevance

A good thesis is a relevant thesis. No one wants to read about a concept that has already been explored hundreds of times, or that no one cares about.

Of course, a thesis heavily relies on the work of other scholars. However, each thesis is – and should be – unique. If you want to write a fantastic thesis introduction, your job is to point out this uniqueness!

In academic research, a research gap signifies a research area or research question that has not been explored yet, that has been insufficiently explored, or whose insights and findings are outdated.

Every thesis needs a crystal-clear research gap. Spell it out instead of letting your reader figure out why your thesis is relevant.

* This example has been taken from an actual academic paper on toxic behaviour in online games: Liu, J. and Agur, C. (2022). “After All, They Don’t Know Me” Exploring the Psychological Mechanisms of Toxic Behavior in Online Games. Games and Culture 1–24, DOI: 10.1177/15554120221115397

The scientific relevance of a thesis highlights the importance of your work in terms of advancing theoretical insights on a topic. You can think of this part as your contribution to the (international) academic literature.

Scientific relevance comes in different forms. For instance, you can critically assess a prominent theory explaining a specific phenomenon. Maybe something is missing? Or you can develop a novel framework that combines different frameworks used by other scholars. Or you can draw attention to the context-specific nature of a phenomenon that is discussed in the international literature.

The societal relevance of a thesis highlights the importance of your research in more practical terms. You can think of this part as your contribution beyond theoretical insights and academic publications.

Why are your insights useful? Who can benefit from your insights? How can your insights improve existing practices?

Formulating a compelling argument

Arguments are sets of reasons supporting an idea, which – in academia – often integrate theoretical and empirical insights. Think of an argument as an umbrella statement, or core claim. It should be no longer than one or two sentences.

Including an argument in the introduction of your thesis may seem counterintuitive. After all, the reader will be introduced to your core claim before reading all the chapters of your thesis that led you to this claim in the first place.

But rest assured: A clear argument at the start of your thesis introduction is a sign of a good thesis. It works like a movie teaser to generate interest. And it helps the reader to follow your subsequent line of argumentation.

The core claim of your thesis should be accompanied by sufficient evidence. This does not mean that you have to write 10 pages about your results at this point.

However, you do need to show the reader that your claim is credible and legitimate because of the work you have done.

A good argument already anticipates possible objections. Not everyone will agree with your core claim. Therefore, it is smart to think ahead. What criticism can you expect?

Think about reasons or opposing positions that people can come up with to disagree with your claim. Then, try to address them head-on.

Providing a captivating preview of findings

Similar to presenting a compelling argument, a fantastic thesis introduction also previews some of the findings. When reading an introduction, the reader wants to learn a bit more about the research context. Furthermore, a reader should get a taste of the type of analysis that will be conducted. And lastly, a hint at the practical implications of the findings encourages the reader to read until the end.

If you focus on a specific empirical context, make sure to provide some information about it. The empirical context could be, for instance, a country, an island, a school or city. Make sure the reader understands why you chose this context for your research, and why it fits to your research objective.

If you did all your research in a lab, this section is obviously irrelevant. However, in that case you should explain the setup of your experiment, etcetera.

The empirical part of your thesis centers around the collection and analysis of information. What information, and what evidence, did you generate? And what are some of the key findings?

For instance, you can provide a short summary of the different research methods that you used to collect data. Followed by a short overview of how you analysed this data, and some of the key findings. The reader needs to understand why your empirical analysis is worth reading.

You already highlighted the practical relevance of your thesis in the introductory chapter. However, you should also provide a preview of some of the practical implications that you will develop in your thesis based on your findings.

Presenting a crystal clear thesis structure

A fantastic thesis introduction helps the reader to understand the structure and logic of your whole thesis. This is probably the easiest part to write in a thesis introduction. However, this part can be best written at the very end, once everything else is ready.

A reading guide is an essential part in a thesis introduction! Usually, the reading guide can be found toward the end of the introductory chapter.

The reading guide basically tells the reader what to expect in the chapters to come.

In a longer thesis, such as a PhD thesis, it can be smart to provide a summary of each chapter to come. Think of a paragraph for each chapter, almost in the form of an abstract.

For shorter theses, which also have a shorter introduction, this step is not necessary.

Especially for longer theses, it tends to be a good idea to design a simple figure that illustrates the structure of your thesis. It helps the reader to better grasp the logic of your thesis.

Master Academia

Get new content delivered directly to your inbox.

Subscribe and receive Master Academia's quarterly newsletter.

The most useful academic social networking sites for PhD students

10 reasons not to do a master's degree, related articles.

Dealing with conflicting feedback from different supervisors

How to deal with procrastination productively during thesis writing

The importance of sleep for efficient thesis writing

Theoretical vs. conceptual frameworks: Simple definitions and an overview of key differences

- Privacy Policy

Home » Significance of the Study – Examples and Writing Guide

Significance of the Study – Examples and Writing Guide

Table of Contents

Significance of the Study

Definition:

Significance of the study in research refers to the potential importance, relevance, or impact of the research findings. It outlines how the research contributes to the existing body of knowledge, what gaps it fills, or what new understanding it brings to a particular field of study.

In general, the significance of a study can be assessed based on several factors, including:

- Originality : The extent to which the study advances existing knowledge or introduces new ideas and perspectives.

- Practical relevance: The potential implications of the study for real-world situations, such as improving policy or practice.

- Theoretical contribution: The extent to which the study provides new insights or perspectives on theoretical concepts or frameworks.

- Methodological rigor : The extent to which the study employs appropriate and robust methods and techniques to generate reliable and valid data.

- Social or cultural impact : The potential impact of the study on society, culture, or public perception of a particular issue.

Types of Significance of the Study

The significance of the Study can be divided into the following types:

Theoretical Significance

Theoretical significance refers to the contribution that a study makes to the existing body of theories in a specific field. This could be by confirming, refuting, or adding nuance to a currently accepted theory, or by proposing an entirely new theory.

Practical Significance

Practical significance refers to the direct applicability and usefulness of the research findings in real-world contexts. Studies with practical significance often address real-life problems and offer potential solutions or strategies. For example, a study in the field of public health might identify a new intervention that significantly reduces the spread of a certain disease.

Significance for Future Research

This pertains to the potential of a study to inspire further research. A study might open up new areas of investigation, provide new research methodologies, or propose new hypotheses that need to be tested.

How to Write Significance of the Study

Here’s a guide to writing an effective “Significance of the Study” section in research paper, thesis, or dissertation:

- Background : Begin by giving some context about your study. This could include a brief introduction to your subject area, the current state of research in the field, and the specific problem or question your study addresses.

- Identify the Gap : Demonstrate that there’s a gap in the existing literature or knowledge that needs to be filled, which is where your study comes in. The gap could be a lack of research on a particular topic, differing results in existing studies, or a new problem that has arisen and hasn’t yet been studied.

- State the Purpose of Your Study : Clearly state the main objective of your research. You may want to state the purpose as a solution to the problem or gap you’ve previously identified.

- Contributes to the existing body of knowledge.

- Addresses a significant research gap.

- Offers a new or better solution to a problem.

- Impacts policy or practice.

- Leads to improvements in a particular field or sector.

- Identify Beneficiaries : Identify who will benefit from your study. This could include other researchers, practitioners in your field, policy-makers, communities, businesses, or others. Explain how your findings could be used and by whom.

- Future Implications : Discuss the implications of your study for future research. This could involve questions that are left open, new questions that have been raised, or potential future methodologies suggested by your study.

Significance of the Study in Research Paper

The Significance of the Study in a research paper refers to the importance or relevance of the research topic being investigated. It answers the question “Why is this research important?” and highlights the potential contributions and impacts of the study.

The significance of the study can be presented in the introduction or background section of a research paper. It typically includes the following components:

- Importance of the research problem: This describes why the research problem is worth investigating and how it relates to existing knowledge and theories.

- Potential benefits and implications: This explains the potential contributions and impacts of the research on theory, practice, policy, or society.

- Originality and novelty: This highlights how the research adds new insights, approaches, or methods to the existing body of knowledge.

- Scope and limitations: This outlines the boundaries and constraints of the research and clarifies what the study will and will not address.

Suppose a researcher is conducting a study on the “Effects of social media use on the mental health of adolescents”.

The significance of the study may be:

“The present study is significant because it addresses a pressing public health issue of the negative impact of social media use on adolescent mental health. Given the widespread use of social media among this age group, understanding the effects of social media on mental health is critical for developing effective prevention and intervention strategies. This study will contribute to the existing literature by examining the moderating factors that may affect the relationship between social media use and mental health outcomes. It will also shed light on the potential benefits and risks of social media use for adolescents and inform the development of evidence-based guidelines for promoting healthy social media use among this population. The limitations of this study include the use of self-reported measures and the cross-sectional design, which precludes causal inference.”

Significance of the Study In Thesis

The significance of the study in a thesis refers to the importance or relevance of the research topic and the potential impact of the study on the field of study or society as a whole. It explains why the research is worth doing and what contribution it will make to existing knowledge.

For example, the significance of a thesis on “Artificial Intelligence in Healthcare” could be:

- With the increasing availability of healthcare data and the development of advanced machine learning algorithms, AI has the potential to revolutionize the healthcare industry by improving diagnosis, treatment, and patient outcomes. Therefore, this thesis can contribute to the understanding of how AI can be applied in healthcare and how it can benefit patients and healthcare providers.

- AI in healthcare also raises ethical and social issues, such as privacy concerns, bias in algorithms, and the impact on healthcare jobs. By exploring these issues in the thesis, it can provide insights into the potential risks and benefits of AI in healthcare and inform policy decisions.

- Finally, the thesis can also advance the field of computer science by developing new AI algorithms or techniques that can be applied to healthcare data, which can have broader applications in other industries or fields of research.

Significance of the Study in Research Proposal

The significance of a study in a research proposal refers to the importance or relevance of the research question, problem, or objective that the study aims to address. It explains why the research is valuable, relevant, and important to the academic or scientific community, policymakers, or society at large. A strong statement of significance can help to persuade the reviewers or funders of the research proposal that the study is worth funding and conducting.

Here is an example of a significance statement in a research proposal:

Title : The Effects of Gamification on Learning Programming: A Comparative Study

Significance Statement:

This proposed study aims to investigate the effects of gamification on learning programming. With the increasing demand for computer science professionals, programming has become a fundamental skill in the computer field. However, learning programming can be challenging, and students may struggle with motivation and engagement. Gamification has emerged as a promising approach to improve students’ engagement and motivation in learning, but its effects on programming education are not yet fully understood. This study is significant because it can provide valuable insights into the potential benefits of gamification in programming education and inform the development of effective teaching strategies to enhance students’ learning outcomes and interest in programming.

Examples of Significance of the Study

Here are some examples of the significance of a study that indicates how you can write this into your research paper according to your research topic:

Research on an Improved Water Filtration System : This study has the potential to impact millions of people living in water-scarce regions or those with limited access to clean water. A more efficient and affordable water filtration system can reduce water-borne diseases and improve the overall health of communities, enabling them to lead healthier, more productive lives.

Study on the Impact of Remote Work on Employee Productivity : Given the shift towards remote work due to recent events such as the COVID-19 pandemic, this study is of considerable significance. Findings could help organizations better structure their remote work policies and offer insights on how to maximize employee productivity, wellbeing, and job satisfaction.

Investigation into the Use of Solar Power in Developing Countries : With the world increasingly moving towards renewable energy, this study could provide important data on the feasibility and benefits of implementing solar power solutions in developing countries. This could potentially stimulate economic growth, reduce reliance on non-renewable resources, and contribute to global efforts to combat climate change.

Research on New Learning Strategies in Special Education : This study has the potential to greatly impact the field of special education. By understanding the effectiveness of new learning strategies, educators can improve their curriculum to provide better support for students with learning disabilities, fostering their academic growth and social development.

Examination of Mental Health Support in the Workplace : This study could highlight the impact of mental health initiatives on employee wellbeing and productivity. It could influence organizational policies across industries, promoting the implementation of mental health programs in the workplace, ultimately leading to healthier work environments.

Evaluation of a New Cancer Treatment Method : The significance of this study could be lifesaving. The research could lead to the development of more effective cancer treatments, increasing the survival rate and quality of life for patients worldwide.

When to Write Significance of the Study

The Significance of the Study section is an integral part of a research proposal or a thesis. This section is typically written after the introduction and the literature review. In the research process, the structure typically follows this order:

- Title – The name of your research.

- Abstract – A brief summary of the entire research.

- Introduction – A presentation of the problem your research aims to solve.

- Literature Review – A review of existing research on the topic to establish what is already known and where gaps exist.

- Significance of the Study – An explanation of why the research matters and its potential impact.

In the Significance of the Study section, you will discuss why your study is important, who it benefits, and how it adds to existing knowledge or practice in your field. This section is your opportunity to convince readers, and potentially funders or supervisors, that your research is valuable and worth undertaking.

Advantages of Significance of the Study

The Significance of the Study section in a research paper has multiple advantages:

- Establishes Relevance: This section helps to articulate the importance of your research to your field of study, as well as the wider society, by explicitly stating its relevance. This makes it easier for other researchers, funders, and policymakers to understand why your work is necessary and worth supporting.

- Guides the Research: Writing the significance can help you refine your research questions and objectives. This happens as you critically think about why your research is important and how it contributes to your field.

- Attracts Funding: If you are seeking funding or support for your research, having a well-written significance of the study section can be key. It helps to convince potential funders of the value of your work.

- Opens up Further Research: By stating the significance of the study, you’re also indicating what further research could be carried out in the future, based on your work. This helps to pave the way for future studies and demonstrates that your research is a valuable addition to the field.

- Provides Practical Applications: The significance of the study section often outlines how the research can be applied in real-world situations. This can be particularly important in applied sciences, where the practical implications of research are crucial.

- Enhances Understanding: This section can help readers understand how your study fits into the broader context of your field, adding value to the existing literature and contributing new knowledge or insights.

Limitations of Significance of the Study

The Significance of the Study section plays an essential role in any research. However, it is not without potential limitations. Here are some that you should be aware of:

- Subjectivity: The importance and implications of a study can be subjective and may vary from person to person. What one researcher considers significant might be seen as less critical by others. The assessment of significance often depends on personal judgement, biases, and perspectives.

- Predictability of Impact: While you can outline the potential implications of your research in the Significance of the Study section, the actual impact can be unpredictable. Research doesn’t always yield the expected results or have the predicted impact on the field or society.

- Difficulty in Measuring: The significance of a study is often qualitative and can be challenging to measure or quantify. You can explain how you think your research will contribute to your field or society, but measuring these outcomes can be complex.

- Possibility of Overstatement: Researchers may feel pressured to amplify the potential significance of their study to attract funding or interest. This can lead to overstating the potential benefits or implications, which can harm the credibility of the study if these results are not achieved.

- Overshadowing of Limitations: Sometimes, the significance of the study may overshadow the limitations of the research. It is important to balance the potential significance with a thorough discussion of the study’s limitations.

- Dependence on Successful Implementation: The significance of the study relies on the successful implementation of the research. If the research process has flaws or unexpected issues arise, the anticipated significance might not be realized.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

How to Cite Research Paper – All Formats and...

Data Collection – Methods Types and Examples

Delimitations in Research – Types, Examples and...

Research Paper Format – Types, Examples and...

Research Process – Steps, Examples and Tips

Research Design – Types, Methods and Examples

How to Write a Science Thesis/Dissertation

A thesis/dissertation is a long, high-level research paper written as the culmination of your academic course. Most university programs require that graduate and postgraduate students demonstrate their ability to perform original research at the thesis/dissertation level as a graduation requirement.

Not all theses/dissertations are structured the same way. In this article, we’ll specifically look at how to structure a thesis/dissertation in the sciences and examine what belongs in each section. Before you begin writing, it is essential to have a good understanding of how to structure your science thesis/dissertation and what elements you must include in it.

How are science theses/dissertations structured?

There isn’t a universal format for a science thesis/dissertation. Each university/institution has its own rules, and these rules can vary further by department and advisor. For this reason, you must start writing/drafting your thesis/dissertation by checking the rules and requirements of your university/institution.

Some universities mandate a minimum word count for a thesis/dissertation, while others provide a maximum. The number of words you are expected to write will also vary depending on the program/course you are a part of. A Master’s level thesis/dissertation can range, for example, from 15,000 to 45,000 words, while a PhD thesis/dissertation can be around 80,000 words.

While your university/institution may have its own specific requirements or guidelines, this article provides a general overview of how a typical thesis/dissertation in the sciences should be structured. For easier understanding, let’s break it up into two parts:

- Thesis body

- Supplemental information

The thesis body of your thesis/dissertation includes:

- Acknowledgements

Table of contents

Introduction/literature review, materials/methodology, discussion/conclusion, figure and tables, list of abbreviations.

Your thesis will conclude with the supplemental information section, which comprises:

Reference list

Your thesis may or may not include each and every one of these sections. Now, let’s examine the parts of a thesis/dissertation in greater detail.

The parts of a science thesis/dissertation: Getting started

Let’s begin by reviewing the sections of the thesis body, from the title page to the glossary. This part of your thesis/dissertation should ideally be written last, even though it comes at the beginning. That is because it is the easiest to put it togethe r once you have written the rest of your thesis/dissertation.

Your thesis/dissertation should have a clear title that sums up the content. In addition, the title page should include your name, the degree of your thesis/dissertation, your department, your advisor, and the month/year of submission. Your university/institution likely has its own format for what should be included in the title page, so make sure to check the relevant guidelines.

Acknowledgments

This section gives you the opportunity to say thanks to anyone who gave you support while you worked on your thesis/dissertation. Many people use this section to give credit to their advisor, editor, or even their parents. If you received any funding for your research or technical assistance, make sure to mention it here.

Your abstract should be a brief summary (generally around 300 words) of your thesis/dissertation. You can think of your abstract as a distillation of your thesis/dissertation as a whole. You need to summarize the scope and objectives, methods, and findings in this section.

The table of contents is a directory of the various parts of your thesis/dissertation. It should include the headings and subheadings of each section along with the page numbers where those sections can be found.

Think of this section as the table of contents for figures and tables in your thesis/dissertation. The titles of each figure/table and the page number where it can be found should be in this list.

This list is intended to identify specialized abbreviations used throughout your thesis/dissertation. This can include the names of organizations (WHO, CDC), acronyms (PFC), and so on. For a science thesis/dissertation, it is preferable also to include a note regarding any abbreviations for units of measurement and standard notations for chemical elements, formulae, and chemical abbreviations used.

In this section, you would define any terminology that your target audience may be unfamiliar with.

The parts of a science thesis/dissertation: Presenting your data

Following the glossary, the thesis body of a science thesis/dissertation begins with the introduction. The introduction section of a science thesis/dissertation often also includes the literature review. This is unlike most social science or humanities theses/dissertations, where the literature review commonly forms a separate chapter. The introduction section should begin by clearly stating the background and context for your research study, followed by your thesis question, objectives, hypothesis , and thesis statement . An example might be:

“The connection between nicotine consumption and insulin resistance has long been established. However, there is no substantial body of research on how long insulin resistance is maintained after people quit smoking. In this study, we aim to measure levels of insulin resistance in otherwise healthy subjects following a total cessation of nicotine consumption. We hypothesize that insulin resistance will begin to decline rapidly within six months.”

The introduction should be immediately followed by a review of earlier literature written on the thesis topic. In this section, you should also clearly identify where the literature connects to your study and how your research study fills a gap or bolsters previous studies. Fit your study within the puzzle of previous work and demonstrate the importance of your research.

In the methodology section of your thesis/dissertation, you must explain what you did and how you did it. If you used materials (for example, bacteria), make sure you clearly list each one. Live materials should be listed, including the specific strain and genus. You must explain your techniques, materials, and methods such that another researcher can replicate exactly what you have done.

In the results section, you will explain what happened. What were your findings? This section should be heavy on data and light on analysis. Usually, in-depth analysis and interpretation of your results will be covered in the discussion section of your thesis/dissertation. While you should present your results in full, any supplementary data that you don’t have room for can be included in an appendix. As a note, this section is often written in the past tense. While other portions of your thesis/dissertation may use past and present interchangeably depending on the topic at hand, the results section of a scientific paper focuses on what has already happened (in an experiment), which is why it is written this way.

In this part of your thesis/dissertation, you will discuss what your findings mean. Did they align with your hypothesis? If so, how? If not, what was different? If there were any exceptions, errors, or total lack of correlation found, do not try to hide it. Clearly discuss what it might mean, or if you aren’t sure, don’t be afraid to say so. In this section, you can also highlight potential practical applications for your research study, limitations of your study, directions for future studies, and once again highlight the importance of your study in the field. This section usually concludes with an overall summarization of whether your results support your hypothesis or not. For example:

“Our study found that 500 of our 600 subjects continued to exhibit high levels of insulin resistance three years or more after stopping nicotine use. This does not support our hypothesis that insulin resistance would begin to drop around six months after subjects stopped nicotine use. Further research is warranted into the mechanisms by which past nicotine use alters insulin resistance levels in former smokers.”

The reference list is an alphabetical or numerical list of sources you’ve used while researching and writing your thesis. The formatting of your reference list will be dependent on your university guidelines. Useful tools like citation generators can help you correctly format your references. Reference managers like EndNote or Mendeley are also helpful for compiling this list. Furthermore, a professional editor or proofreading service can ensure that each reference is correctly formatted.

This section can be very useful if you want to include materials that are relevant to the topic of your thesis/dissertation but that you were unable to include in the main text. Tables, large bodies of text, illustrations, forms used to collect data or perform studies, and other such materials can all be included in an appendix.

Critical steps for planning, drafting, and structuring a science thesis/dissertation

Writing your thesis/dissertation is a daunting and lengthy task. Here are some helpful tips to keep in mind when drafting your science thesis/dissertation:

- Choose a thesis topic that is of professional interest to you. You are going to spend a lot of time thinking, reading, and writing about your thesis topic. Many aspiring young researchers end up working in a field related to their thesis/dissertation . If you start researching or writing a proposal and then decide you aren’t into the topic, don’t be afraid to change directions!

- Plan your thesis timelines carefully. Is your topic realistic given the time and material constraints you have? Do you need to apply for external funding for your research study? Will that take additional time? Write a schedule and revisit/revise it often throughout your thesis/dissertation process.

- Don’t wait until the last minute to start writing! A thesis/dissertation isn’t like an undergraduate paper where you spend some time researching and then some time writing it. You will need to write your thesis/dissertation as you continue your research study. Write as you work in the lab. Write as you learn things and then revise. Ideally, by the time you have finished your actual research study, you will already have a substantive draft.

- Start writing the methodology section first. This is often the easiest because it is straightforward and you have already done quite a lot of the work while preparing your research study. The order in which you write your thesis/dissertation doesn’t matter too much—if you find yourself jumping between sections, that is perfectly normal.

- Keep a detailed list of your references using a reference manager or similar system, with tags so that you can easily identify the source of your information.

Final tips for writing and structuring a science thesis/dissertation

Writing a thesis/dissertation is a rewarding process. As a final tip for getting through this process successfully, don’t forget to leave sufficient time for editing and proofreading. Your thesis/dissertation will go through many drafts and revisions before it reaches its final form.

Engaging the services of a professional can go a long way in helping you produce a professional and high-quality document worthy of your research. In addition, there are many helpful tools like AI grammar checker tools available online for students and young researchers.

Check out our site for more tips on how to write a good thesis/dissertation , where to find the best thesis editing services , and more about thesis editing and proofreading services .

Editor’s pick

Get free updates.

Subscribe to our newsletter for regular insights from the research and publishing industry!

Review Checklist

Use this checklist to ensure that your science thesis/dissertation isn’t missing any important structural components.

Title page: Does your thesis/dissertation have a title page with your title, name, department, advisor’s name, and other important information?

Acknowledgements: Did you give credit to your funders, research colleagues, and anyone else who helped you?

Abstract: Does your thesis/dissertation include a brief summary?

Table of contents: Does your table of contents include headings, subheadings, and page numbers?

Figure and tables: Is there a complete list of figures and tables that are in your thesis/dissertation?

List of abbreviations: Are all of the abbreviations used in your thesis/dissertation listed here?

Glossary: Did you clearly define any specialized terminology used in your thesis/dissertation?

Introduction/Literature review: Did you justify your research study, state your objectives, and your hypothesis? Did you review the previous relevant literature in your field and explain how your thesis/dissertation fits in?

Materials/Methodology: Could another scientist replicate what you did by reading this section?

Results: Did you include all of the data from your experiments/research study?

Discussion/Conclusion: Did you clearly explain what your results mean and whether your hypothesis was correct or not?

Reference list: Are your references properly formatted and listed alphabetically or numerically?

Bibliography and Appendices: Did you include any additional relevant data, figures, or text that didn’t fit into the main section of your thesis/dissertation?

How long is a typical science thesis/dissertation? +

A typical Master’s thesis/dissertation ranges from 15,000-45,000 words, while a Ph.D. thesis/dissertation can be as much as 80,000 words.

How do I start my thesis/dissertation? +

You don’t have to start with the introduction when you begin writing. You can start with the methodology section or any other section you prefer and revise it later.

How do I structure a science thesis/dissertation? +

The main section of a science thesis/dissertation includes an introduction/literature review, materials/methodology section, results, discussion/conclusion section, and a references list.

What Is A Research (Scientific) Hypothesis? A plain-language explainer + examples

By: Derek Jansen (MBA) | Reviewed By: Dr Eunice Rautenbach | June 2020

If you’re new to the world of research, or it’s your first time writing a dissertation or thesis, you’re probably noticing that the words “research hypothesis” and “scientific hypothesis” are used quite a bit, and you’re wondering what they mean in a research context .

“Hypothesis” is one of those words that people use loosely, thinking they understand what it means. However, it has a very specific meaning within academic research. So, it’s important to understand the exact meaning before you start hypothesizing.

Research Hypothesis 101

- What is a hypothesis ?

- What is a research hypothesis (scientific hypothesis)?

- Requirements for a research hypothesis

- Definition of a research hypothesis

- The null hypothesis

What is a hypothesis?

Let’s start with the general definition of a hypothesis (not a research hypothesis or scientific hypothesis), according to the Cambridge Dictionary:

Hypothesis: an idea or explanation for something that is based on known facts but has not yet been proved.

In other words, it’s a statement that provides an explanation for why or how something works, based on facts (or some reasonable assumptions), but that has not yet been specifically tested . For example, a hypothesis might look something like this:

Hypothesis: sleep impacts academic performance.

This statement predicts that academic performance will be influenced by the amount and/or quality of sleep a student engages in – sounds reasonable, right? It’s based on reasonable assumptions , underpinned by what we currently know about sleep and health (from the existing literature). So, loosely speaking, we could call it a hypothesis, at least by the dictionary definition.

But that’s not good enough…

Unfortunately, that’s not quite sophisticated enough to describe a research hypothesis (also sometimes called a scientific hypothesis), and it wouldn’t be acceptable in a dissertation, thesis or research paper . In the world of academic research, a statement needs a few more criteria to constitute a true research hypothesis .

What is a research hypothesis?

A research hypothesis (also called a scientific hypothesis) is a statement about the expected outcome of a study (for example, a dissertation or thesis). To constitute a quality hypothesis, the statement needs to have three attributes – specificity , clarity and testability .

Let’s take a look at these more closely.

Need a helping hand?

Hypothesis Essential #1: Specificity & Clarity

A good research hypothesis needs to be extremely clear and articulate about both what’ s being assessed (who or what variables are involved ) and the expected outcome (for example, a difference between groups, a relationship between variables, etc.).

Let’s stick with our sleepy students example and look at how this statement could be more specific and clear.

Hypothesis: Students who sleep at least 8 hours per night will, on average, achieve higher grades in standardised tests than students who sleep less than 8 hours a night.

As you can see, the statement is very specific as it identifies the variables involved (sleep hours and test grades), the parties involved (two groups of students), as well as the predicted relationship type (a positive relationship). There’s no ambiguity or uncertainty about who or what is involved in the statement, and the expected outcome is clear.

Contrast that to the original hypothesis we looked at – “Sleep impacts academic performance” – and you can see the difference. “Sleep” and “academic performance” are both comparatively vague , and there’s no indication of what the expected relationship direction is (more sleep or less sleep). As you can see, specificity and clarity are key.

Hypothesis Essential #2: Testability (Provability)

A statement must be testable to qualify as a research hypothesis. In other words, there needs to be a way to prove (or disprove) the statement. If it’s not testable, it’s not a hypothesis – simple as that.

For example, consider the hypothesis we mentioned earlier:

Hypothesis: Students who sleep at least 8 hours per night will, on average, achieve higher grades in standardised tests than students who sleep less than 8 hours a night.

We could test this statement by undertaking a quantitative study involving two groups of students, one that gets 8 or more hours of sleep per night for a fixed period, and one that gets less. We could then compare the standardised test results for both groups to see if there’s a statistically significant difference.

Again, if you compare this to the original hypothesis we looked at – “Sleep impacts academic performance” – you can see that it would be quite difficult to test that statement, primarily because it isn’t specific enough. How much sleep? By who? What type of academic performance?

So, remember the mantra – if you can’t test it, it’s not a hypothesis 🙂

Defining A Research Hypothesis

You’re still with us? Great! Let’s recap and pin down a clear definition of a hypothesis.

A research hypothesis (or scientific hypothesis) is a statement about an expected relationship between variables, or explanation of an occurrence, that is clear, specific and testable.

So, when you write up hypotheses for your dissertation or thesis, make sure that they meet all these criteria. If you do, you’ll not only have rock-solid hypotheses but you’ll also ensure a clear focus for your entire research project.

What about the null hypothesis?

You may have also heard the terms null hypothesis , alternative hypothesis, or H-zero thrown around. At a simple level, the null hypothesis is the counter-proposal to the original hypothesis.

For example, if the hypothesis predicts that there is a relationship between two variables (for example, sleep and academic performance), the null hypothesis would predict that there is no relationship between those variables.

At a more technical level, the null hypothesis proposes that no statistical significance exists in a set of given observations and that any differences are due to chance alone.

And there you have it – hypotheses in a nutshell.

If you have any questions, be sure to leave a comment below and we’ll do our best to help you. If you need hands-on help developing and testing your hypotheses, consider our private coaching service , where we hold your hand through the research journey.

Psst... there’s more!

This post was based on one of our popular Research Bootcamps . If you're working on a research project, you'll definitely want to check this out ...

You Might Also Like:

16 Comments

Very useful information. I benefit more from getting more information in this regard.

Very great insight,educative and informative. Please give meet deep critics on many research data of public international Law like human rights, environment, natural resources, law of the sea etc

In a book I read a distinction is made between null, research, and alternative hypothesis. As far as I understand, alternative and research hypotheses are the same. Can you please elaborate? Best Afshin

This is a self explanatory, easy going site. I will recommend this to my friends and colleagues.

Very good definition. How can I cite your definition in my thesis? Thank you. Is nul hypothesis compulsory in a research?

It’s a counter-proposal to be proven as a rejection

Please what is the difference between alternate hypothesis and research hypothesis?

It is a very good explanation. However, it limits hypotheses to statistically tasteable ideas. What about for qualitative researches or other researches that involve quantitative data that don’t need statistical tests?

In qualitative research, one typically uses propositions, not hypotheses.

could you please elaborate it more

I’ve benefited greatly from these notes, thank you.

This is very helpful

well articulated ideas are presented here, thank you for being reliable sources of information

Excellent. Thanks for being clear and sound about the research methodology and hypothesis (quantitative research)

I have only a simple question regarding the null hypothesis. – Is the null hypothesis (Ho) known as the reversible hypothesis of the alternative hypothesis (H1? – How to test it in academic research?

this is very important note help me much more

Trackbacks/Pingbacks

- What Is Research Methodology? Simple Definition (With Examples) - Grad Coach - […] Contrasted to this, a quantitative methodology is typically used when the research aims and objectives are confirmatory in nature. For example,…

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

Societal impact or scientific relevance?

The relevance of title, abstract, and keywords for scientific paper quality and potential impact

- Open access

- Published: 27 February 2023

- Volume 82 , pages 23075–23090, ( 2023 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Jorge Chamorro-Padial ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-6334-3786 1 &

- Rosa Rodríguez-Sánchez ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-7886-9329 2

1730 Accesses

2 Citations

Explore all metrics

Authors, editors, and reviewers need to have a good perception regarding the quality of a manuscript in order to improve their skills, save effort, and prevent errors that can affect the submission procedure. In this paper, we compared the author’s perception of a manuscript’s quality with the manuscript’s actual impact. In addition, we analyzed the uncertainty of the author’s perception of the manuscript’s quality. From there, we defined ‘partition’ as the author’s ability to perceive the actual quality. We did this by launching a website for the use of the scientific community. This webpage provided a tool to help improve an investigator’s skill in understanding and recognizing the quality of a manuscript so as to help researchers improve and maximize their works’ potential impact. We carried out the experiment with 106 experienced users who tested our webpage. We found that the Abstract, the Title, and the Keywords were enough to perform a substantially decent evaluation of a manuscript. Most of the researchers were able to determine the quality of a paper in less than a minute from this small amount of information.

Similar content being viewed by others

Literature reviews as independent studies: guidelines for academic practice

Statistical tests, P values, confidence intervals, and power: a guide to misinterpretations

How to Write and Publish a Research Paper for a Peer-Reviewed Journal

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

In the academic field, authors need to publish their results in order to make them available to the public, and manuscripts are one of the most important ways to achieve those needs. We can simplify the manuscript publishing process into the following steps: 1) Authors write a manuscript and send it to a journal, 2) The journal reviews the manuscript to check if their quality standards are met, and 3) After the review process, the manuscript is either published or rejected. We can consider manuscripts as potential papers once they pass a review process and various corrections or modifications are made (if required).

Usually, there are plenty of candidate journals where a manuscript could suitably fit according to the topic(s) and the manuscript’s field of knowledge. This situation forces authors to select a journal where they would prefer to have their work published. Typically, every candidate journal has a different level of impact. The impact is defined by [ 1 ] as one of academia’s strongest currencies . For a journal, impact is an important asset which ensures that the scientific community, libraries, and academic researchers all continue to pay attention to its publications. Low impact journals face the risk of being removed from scientific indexes and losing interest from the community. For authors, the impact directly affects their visibility and prestige, which can, in turn, directly affect their research career.

Articles published in high-impact journals will presumably have a more significant impact than articles published in low-impact journals. Quality is another critical asset along with impact. We consider a manuscript’s quality in terms of originality, importance, soundness of theory, and verified conclusions. From the point of view of a journal, high-quality articles have a greater probability of attracting the scientific community’s interest. Thus, journals tend to define measures in order to select articles of the highest possible quality [ 7 ]. When a journal receives an article, the manuscript is often initially checked to determine if a minimum quality is met. If not, the article would be promptly rejected as a desk decision. If the article fits the journal’s minimum quality standards then it is usually sent to the next step, a peer-review [ 11 ].

In this paper, we want to offer support to the peer-review process by providing a tool that can be useful for training and improving the skills of authors, reviewers, and editors while imparting valuable knowledge:

For authors: We propose that our tool can help authors recognize their ability when distinguishing the quality of a manuscript. This knowledge can be useful when choosing a journal for their manuscripts. Also, authors tend to suffer from confirmation bias, which leads to overconfidence as authors believe their manuscripts are of a higher quality regardless of what the actual, objective quality is [ 18 ]. The proposed tool can help authors correct this bias by comparing their choices about the manuscript’s quality (Low, Medium, High quality) with its actual quality.

For reviewers: We want to give them feedback about their ability to identify an article’s quality. For example, a reviewer who incorrectly matches the quality of a manuscript and the quality standard of a journal would incur a cost to the journal [ 6 ].

For editors: For editors, knowing their skill-level when properly identifying the quality of a manuscript can be also useful. For example, a desk decision can save effort and time for reviewers and authors if the editor believes that the manuscript’s quality does not match the journal’s quality standards [ 8 , 17 ].

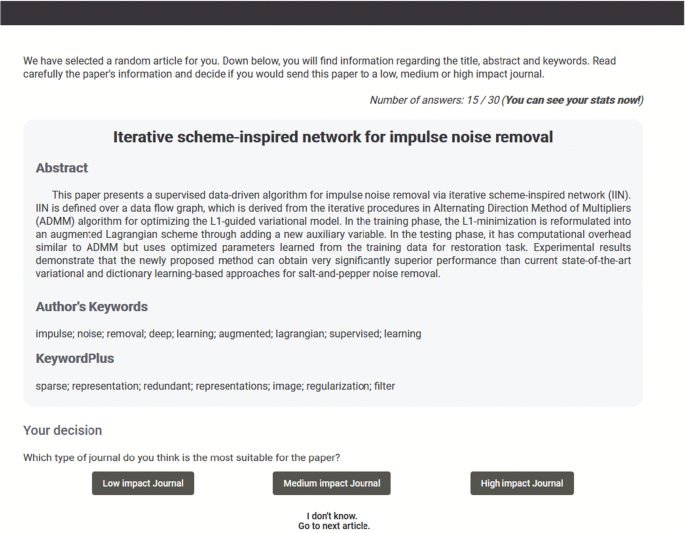

In order to do all of this we built a web training system Footnote 1 where users can review information about different real papers and decide what their quality is while receiving direct feedback about their decisions. On our website, authors are presented with only the key elements of an article (abstract, title, and keywords). During the training process, their time per response is measured. From this we wanted to answer the following questions:

What is the level of uncertainty that authors have about the quality of a manuscript with respect to its actual quality?

Do the Title, the Abstract, and the Keywords contain enough information to determine the quality of a manuscript?

What is the average time that an author spends reviewing the key information of a manuscript?

We assumed that an article’s actual quality matched the impact category (Low, Medium, or High) of the journal where the manuscript was published.

Our work is structured in the following manner:

State of the Art and related works : Explores the current state of the art information and research in this field in terms of scientific literature.

Model: Describes our model.

Methodology: Explains the methodology of our experiment, the website, and the dataset used.

Results: Reports the results obtained from users who used our website.

Discussion : In this section, we perform a more detailed analysis of the results achieved.

Conclusions: The last section of our work presents the critical information from our paper.

2 State of the art and related works

Peer review is a standard quality control procedure that is part of a consensus-seeking scientific discussion on quality assurance [ 13 ]. During the peer review stage, an editor selects reviewers who are expected to read the candidate manuscript and give a critical assessment regarding the work’s quality. Peer review acts as an editor’s source of knowledge to help them decide if a manuscript should be accepted, rejected, or returned to the author(s) with corrections [ 3 ]. Manuscripts relevant to the journal’s scope, which are innovative and well written, have a higher probability of being accepted [ 6 ].

In this context, authors will want to send their manuscript to as high an impact journal as possible, while journals will want to publish articles of the highest quality possible. From the perspective of an author, if he or she sends a high-quality manuscript to a low-impact journal there will be a substantial cost in terms of lack of visibility. It is important to mention that journal impact factor is a strong predictor of the number of citations [ 2 ]. Nevertheless, sending a low-quality manuscript to a high-impact journal increases the risk of rejection, which would affect the time and effort spent trying to publish, as well as the author’s motivation. Writing a manuscript for a high-impact peer-reviewed journal can be a challenging and frustrating experience. For example, [ 22 ] concludes that “the authors do few manuscript submissions prior to journal acceptance, most commonly by lower impact factor journals”.

In [ 18 ] the authors analyzed the evolutionary game derived from journal quality controls. An author produces low or high-quality manuscripts which are then submitted to journals who accept manuscripts of different qualities with a certain probability. The authors also identified different strategies and their survival chances according to evolutionary games. These strategies are based on the concept of authors’ and editors’ quality profiles. An author’s profile is based on the probability of an author submitting articles of a certain quality (low or high). In contrast, an editor’s profile is based on the frequency with which an editor accepts articles with a specific quality (low or high).

A vast majority of authors still feel the need to enhance their skills in popular science writing [ 16 ]. Nowadays, the author can use different tools that can help in the process of writing a manuscript. Among these tools, we can distinguish Jasper Footnote 2 and Hemingway Editor. Footnote 3 Jasper uses AI to help write different parts of the manuscript. For its part, Hemingway helps the author highlight problems with their writing. Its goal is to make complex sentences easier. However, while those tools help to write a manuscript, the author must have the ability to recognize the quality of the manuscript.

Different works focus on the author’s perception of the manuscript’s quality. This topic is important to analyze since according to [ 15 ] absolute impact factor of the journal, match between perceived “quality” of their study, and journal impact factor were considered to be the three most important factors by the authors when they have to submit a manuscript.

In [ 19 ] concrete suggestions for improving the perception of a paper in the reader’s minds is presented. Also, [ 23 ] proposed a pilot study to evaluate a method of teaching neurology residents the basic concepts of biostatistics, research methodology, and review of scholarly literature by employing a program of peer-reviewed scientific manuscripts.

Selecting a journal is not always without problems, as authors can suffer from having a flawed perception about their article’s quality. Additionally, reviewers can have imperfect knowledge or bias when determining the quality of a reviewed work. If authors can distinguish the actual quality or impact of a manuscript, they have a fine partition. Conversely, if they cannot distinguish the actual quality of an article, they have a coarse partition. Here, a partition is defined as a map between the author’s perception of the manuscript’s quality and the actual impact of the manuscript. If the author’s perception coincides with reality, we can say that they have a fine partition. The actual impact of a manuscript can be measured by the impact of the journal where it was published. We also used the author’s profile as one of the possible indicators of the quality of a manuscript given the author’s partition. For example, suppose an author cannot distinguish between a low, medium, and high impact manuscript (they have a coarse partition) when the author has to evaluate a manuscript’s impact. In that case, he or she would have three profiles: low, medium, or high impact. On the contrary, if an author has a fine partition, they could have 27 possible profiles. The perception of the quality of a manuscript depends on the author’s partition and the distribution of articles over three different categories (High impact, Medium impact, and Low impact).

The same concept is applied to reviewers [ 5 ]. The quasi-species model inspires our work to determine the evolution of an authors’ profiles after the peer-review process. This model was intended to represent the Darwinian evolution of self-replicating entities when a high mutation rate occurs [ 12 , 20 ]. According to this model, a quasi-species is a big group, or cloud , of genotypes in an environment where their descendants will have a high probability of mutation. The evolutionary success of a quasi-species strongly depends on the replication rates of clouds. In [ 5 ] the authors adapted the quasi-species model from biology to the author-editor game’s evolutionary environment. Self-replicating entities are submission profiles under a given partition of manuscript categories. Errors produce profile mutations, and only submission profiles with high replication rates survive.

Peer review is not exempt from criticism and deficiencies [ 10 , 11 ], but nowadays it is one of the scientific community’s essential tools to validate and improve the quality of science. Every year, about 13.7 million reviews are done in the academic ecosystem for a total of 3 million scientific articles [ 9 , 21 ]. Additionally, peer-review is an indicator of prestige and confidence for journals and authors [ 2 , 14 ]. Ultimately, we can say that peer-review is a crucial element of the science of today, and it is necessary to continue to improve it by raising the skill of all actors involved in the process.

As described in the introduction, an author submits a manuscript that can have different levels of quality. In this paper, we define three different manuscript categories: S = { s 1 , s 2 , s 3 }, with s 1 being a low-quality manuscript, s 2 a medium-quality manuscript, and s 3 a high-quality manuscript. Likewise, we define three different journal impacts, I = { Low − impact , Medium − impact , High − impact }. The action of sending an article to a journal can be seen as optimal or non-optimal. For example, if an author sends a low-quality article to a high-impact journal, it is very likely to get a rejection. In that case, the author has lost time and effort, so it is considered a non-optimal action. Additionally, if an author sends a high-quality article to a low-impact journal, the author is paying the price in terms of visibility, prestige, and impact, which is also a non-optimal action. For s j ∈ S we can define an optimal action as follows:

With i ∗ ( s 1 ) being the optimal action of sending a low-quality article to a low-impact journal.

With i ∗ ( s 2 ) being the optimal action of sending a medium-quality article to a medium-impact journal.

With i ∗ ( s 3 ) being the optimal action of sending a high-quality article to a high-impact journal.

Every action gives a score to the author. In our model, the result for non-optimal actions is 0, while the optimal action score is 1. We define the reward function, π i ( s j ) for i ∈ I and j ∈ S , as follows:

Every author has a different ability to identify the quality of an article. We formally represent the distinctive capabilities of authors as partitions . Every author uses a particular partition. If an author can distinguish between low, medium, and high-quality articles, then the author has a fine partition, K F = {{ s 1 }, { s 2 }, { s 3 }}. If an author does not distinguish between any type of quality, then the author uses a coarse partition K C = { s 1 , s 2 , s 3 }. Among these polarized partitions, we can also identify other ones:

\({K}_{F_1}=\left\{\left\{{s}_1\right\},\left\{{s}_2,{s}_3\right\}\right\}\) : The author can identify low-quality articles but cannot identify medium and high-quality articles.

\({K}_{F_2}=\left\{\left\{{s}_2\right\},\left\{{s}_1,{s}_3\right\}\right\}\) : The author can identify medium-quality articles but cannot identify between low and high-quality articles.

\({K}_{F_3}=\left\{\left\{{s}_3\right\},\left\{{s}_1,{s}_2\right\}\right\}\) : The author can identify high-quality articles but cannot identify low and medium-quality articles.