- The Open University

- Guest user / Sign out

- Study with The Open University

My OpenLearn Profile

Personalise your OpenLearn profile, save your favourite content and get recognition for your learning

The debate on the origins of the First World War

This page was published over 5 years ago. Please be aware that due to the passage of time, the information provided on this page may be out of date or otherwise inaccurate, and any views or opinions expressed may no longer be relevant. Some technical elements such as audio-visual and interactive media may no longer work. For more detail, see how we deal with older content .

Find out more about The Open University's History courses and qualifications

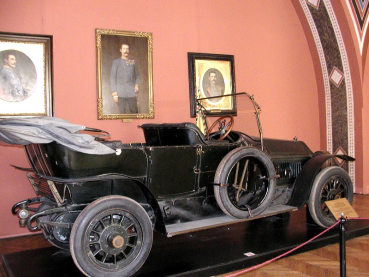

How could the death of one man, Archduke Franz Ferdinand, who was assassinated on 28 June 1914, lead to the deaths of millions in a war of unprecedented scale and ferocity? This is the question at the heart of the debate on the origins of the First World War. Finding the answer to this question has exercised historians for 100 years.

In July 1914, everyone in Europe was convinced they were fighting a defensive war. Governments had worked hard to ensure that they did not appear to be the aggressor in July and August 1914. This was crucial because the vast armies of soldiers that would be needed could not be summoned for a war of aggression.

Socialists, of whom there were many millions by 1914, would not have supported a belligerent foreign policy and could only be relied upon to fight in a defensive war. French and Belgians, Russians, Serbs and Britons were convinced they were indeed involved in a defensive struggle for just aims. Austrians and Hungarians were fighting to avenge the death of Franz Ferdinand.

Germans were convinced that Germany’s neighbours had ‘forced the sword’ into its hands, and they were certain that they had not started the war. But if not they (who had after all invaded Belgium and France in the first few weeks of fighting), then who had caused this war?

The war guilt ruling

For the victors, this was an easy question to answer, and they agreed at the peace conference at Versailles in 1919 that Germany and its allies had been responsible for causing the Great War.

Based on this decision, vast reparation demands were made. This so-called ‘war guilt ruling’ set the tone for the long debate on the causes of the war that followed.

From 1919 onwards, governments and historians engaged with this question as revisionists (who wanted to revise the verdict of Versailles) clashed with anti-revisionists who agreed with the victors’ assessment.

Sponsored by post-war governments and with access to vast amounts of documents, revisionist historians set about proving that the victors at Versailles had been wrong.

Countless publications and documents were made available to prove Germany’s innocence and the responsibility of others.

Arguments were advanced which highlighted Russia’s and France’s responsibility for the outbreak of the war, for example, or which stressed that Britain could have played a more active role in preventing the escalation of the July Crisis.

In the interwar years, such views influenced a new interpretation that no longer highlighted German war guilt, but instead identified a failure in the alliance system before 1914. The war had not been deliberately unleashed, but Europe had somehow ‘slithered into the boiling cauldron of war’, as David Lloyd George famously put it. With such a conciliatory accident theory, Germany was off the hook. A comfortable consensus emerged and lasted all through the Second World War and beyond, by which time the First World War had been overshadowed by an even deadlier conflict.

The Fischer Thesis

The first major challenge to this interpretation was advanced in Germany in the 1960s, where the historian Fritz Fischer published a startling new thesis which threatened to overthrow the existing consensus. Germany, he argued, did have the main share of responsibility for the outbreak of the war. Moreover, its leaders had deliberately unleashed the war in pursuit of aggressive foreign policy aims which were startlingly similar to those pursued by Hitler in 1939.

Backed up by previously unknown primary evidence, this new interpretation exploded the comfortable post-war view of shared responsibility. It made Germany responsible for unleashing not only the Second World War (of this there was no doubt), but also the First - turning Germany’s recent history into one of aggression and conquest.

Many leading German historians and politicians reacted with outrage to Fischer’s claims. They attempted to discredit him and his followers in a public debate of unprecedented ferocity. Some of those arguing about the causes of the war had fought in it, in the conviction they were fighting a defensive war. Little wonder they objected to the suggestion that Germany had deliberately started that conflict.

In time, however, many of Fischer’s ideas became accepted as a new consensus was achieved. Most historians remained unconvinced that war had been decided upon in Germany as early as 1912 (this was one of Fischer’s controversial claims) and then deliberately provoked in 1914.

Many did concede, however, that Germany seemed to have made use of the July Crisis to unleash a war. In the wake of the Fischer controversy, historians also focused more closely on the role of Austria-Hungary in the events that led to war, and concluded that in Vienna, at least as much as in Berlin, the crisis precipitated by the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand was seen as a golden opportunity to try and defeat a ring of enemies that seemed to threaten the central powers.

Recent revisions

In recent years this post-Fischer consensus has in turn been revised. Historians have returned to the arguments of the interwar years, focusing for example on Russia’s and France’s role in the outbreak of war, or asking if Britain’s government really did all it could to try and avert the war in 1914. Germany’s and Austria-Hungary’s roles are again deemphasised.

After 100 years of debate, every conceivable interpretation seems to have been advanced, dismissed and then revisited. In some of the most recent publications, even seeking to attribute responsibility, as had so confidently been done at Versailles, is now eschewed.

Is it really the historian’s role to blame the actors of the past, or merely to understand how the war could have occurred? Such doubts did not trouble those who sought to attribute war guilt in 1919 and during much of this long debate, but this question will need to be asked as the controversy continues past the centenary.

After 100 years of arguing about the war’s causes, this long debate is set to continue.

Next: listen to the viewpoints of two leading historians on the causes of the war with our podcast Expert opinion: A debate on the causes of the First World War

This page is part of our collection about the origins of the First World War .

Discover more about the First World War

The origins of the First World War

Take an in-depth look at how Europe ended up fighting a four-year war (1914-1918) on a global scale with this collection on the First World War.

The Somme: The German perspective

How do Germans view the Battle of The Somme? This article explores reactions to the most famous battle of the First World War.

The assassination of Franz Ferdinand

How did a conspiracy to kill Archduke Franz Ferdinand set off a chain of events ending in the First World War? Explore what sparked the July Crisis.

Study a free course

The First World War: trauma and memory

In this free course, The First World War: trauma and memory, you will study the subject of physical and mental trauma, its treatments and its representation. You will focus not only on the trauma experienced by combatants but also the effects of the First World War on civilian populations.

Become an OU student

Ratings & comments, share this free course, copyright information, publication details.

- Originally published: Thursday, 19 December 2013

- Body text - Creative Commons BY-NC-SA 4.0 : The Open University

- Image 'The First World War: trauma and memory' - Copyright: © wragg (via iStockPhoto.com)

- Image 'The origins of the First World War' - Copyright free: By Underwood & Underwood. (US War Dept.) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

- Image 'The assassination of Franz Ferdinand' - By Alexf (Own work) [ CC-BY-SA-3.0 or GFDL ], via Wikimedia Commons under Creative-Commons license

- Image 'The Somme: The German perspective' - Copyright: BBC

Rate and Review

Rate this article, review this article.

Log into OpenLearn to leave reviews and join in the conversation.

Article reviews

For further information, take a look at our frequently asked questions which may give you the support you need.

- Search Menu

- Conflict, Security, and Defence

- East Asia and Pacific

- Energy and Environment

- Global Health and Development

- International History

- International Governance, Law, and Ethics

- International Relations Theory

- Middle East and North Africa

- Political Economy and Economics

- Russia and Eurasia

- Sub-Saharan Africa

- Advance Articles

- Editor's Choice

- Special Issues

- Virtual Issues

- Reading Lists

- Archive Collections

- Book Reviews

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access

- Self-Archiving Policy

- About International Affairs

- About Chatham House

- Editorial Board

- Advertising & Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

- < Previous

Goodbye to all that (again)? The Fischer thesis, the new revisionism and the meaning of the First World War

This is a revised text of the 39th Martin Wight Lecture, given at the University of Sussex on 6 November 2014.

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

JOHN C. G. RÖHL, Goodbye to all that (again)? The Fischer thesis, the new revisionism and the meaning of the First World War, International Affairs , Volume 91, Issue 1, January 2015, Pages 153–166, https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2346.12191

- Permissions Icon Permissions

What is the truth about the nature of the First World War and why have historians been unable to agree on its origins? The interpretation that no one country was to blame prevailed until the 1960s when a bitter international controversy, sparked by the work of the Hamburg historian Fritz Fischer, arrived at the consensus that the Great War had been a ‘bid for world power’ by imperial Germany and therefore a conflict in which Britain had necessarily and justly engaged. But in this centennial year Fischer's conclusions have in turn been challenged by historians claiming that Europe's leaders all ‘sleepwalked’ into the catastrophe. This article, the text of the Martin Wight Memorial Lecture held at the University of Sussex in November 2014, explores the archival discoveries which underpinned the Fischer thesis of the 1960s and subsequent research, and asks with what justification such evidence is now being set aside by the new revisionism.

Email alerts

Citing articles via.

- Recommend to Your Librarian

- Advertising and Corporate Services

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1468-2346

- Print ISSN 0020-5850

- Copyright © 2024 The Royal Institute of International Affairs

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

Goodbye to all that (again)? The Fischer thesis, the new revisionism and the meaning of the First World War

In Memoriam

Fritz Fischer (1908-99)

Volker R. Berghahn | Mar 1, 2000

Fritz Fischer, professor emeritus at Hamburg University and one of the most influential historians of modern Germany since 1945, died on December 1, 1999 at the age of 91. He was named an Honorary Foreign Member of the AHA in 1984.

Born on March 5, 1908 in Upper Franconia in southern Germany, he embarked upon the long road of a German university career, finally obtaining a full professorship at Hamburg University in 1948. Originally a specialist in 19th-century German Protestantism, he had been briefly associated with Hans Frank's "Reich Institute for the History of the New Germany" under Hitler, but belonged to those German academics and intellectuals who came out of World War II determined to build a different Germany and to wrench the German historical profession away from its nationalist-conservative past.

This opportunity came when Fischer was given access, in the 1950s, to the East German archives at Potsdam, where he came across an explosive set of files relating to war aims and annexationist plans that the Reich government had drawn up in World War I. It was not merely the extent of Germany's territorial ambitions that moved him to develop his provocative hypotheses, but also the suspicion that the German government might have started the war in the first place in order to realize its expansionist program on the European continent. His book on this theme, titled Griff nach der Weltmacht (1961; trans. 1967, rather less grippingly, Germany's War Aims in the First World War ), caused a huge public uproar. His German colleagues had just about accepted that Germany had been squarely responsible for unleashing World War II, but they fiercely resisted Fischer's notion of German responsibility for World War I. Gerhard Ritter, the doyen of West Germany's historians, spoke of the "self-obscuration of German historical consciousness." He continued to hold that all powers were more or less equally guilty of pushing Europe over the brink.

Fischer held his ground against these attacks, repeatedly pulling from his pocket, during televised debates with fellow historians and journalists, yet another official memorandum or telegram proving his point. Meanwhile students from all faculties at Hamburg University flocked to his lectures, easily filling the large Auditorium Maximum, and some of them stayed on to write a doctoral dissertation under his supervision. Several of them made important contributions to the history of the German Empire in their own right and some historians of German historiography have spoken of a "Fischer School," whose members went to bat for their mentor's cause.

The politicization of the Fischer Controversy went so far that at one point some of his colleagues persuaded the Bonn government to withdraw promised financial support for a lecture tour by Fischer in the United States. Angry American historians thereupon found the money themselves to pay for the trip.

As criticism continued, Fischer decided to present his subsequent archival findings concerning Germany's aggressive foreign policy and the origins of World War I in a second 800-page tome, titled Krieg der Illusionen (1969, trans. 1973, this time literally, War of Illusions ). In this volume he also advanced the theory that in December 1912, at an infamous "War Council," Wilhelm II and his military advisors had made a decision to trigger a major war by the summer of 1914 and to use the intervening months to prepare the country for this settling of accounts. In the 1970s Fischer published further, shorter studies and essays elaborating on the myopia and political failures of Germany's elites. He became one of the most explicit advocates of the Sonderweg thesis, i.e., the argument that Germany had taken a special path into the 20th century, and also threw himself into the controversy over the authenticity of diaries that Kurt Riezler, the private secretary of Reich Chancellor Bethmann Hollweg, had kept during the July Crisis of 1914.

Some of Fischer's more radical hypotheses have been challenged and modified by subsequent research published after the heated arguments of the 1960s had subsided. This time American and British historians had a major share in effecting this shift that has resulted in a more complex picture of Wilhelmine society and politics. But if his more specific findings on who was responsible for the outbreak of World War I have been revised, very few people doubt today that, as Fischer had argued, the Kaiser and his advisors played a crucial role in the escalation of the international crisis of July 1914, although they were in the best position to de-escalate. Nor does anyone deny that the exorbitant annexationist plans of the German monarchy in World War I were ominous harbingers of Hitler's ruthless imperialism 25 years later.

The repercussions of Fischer's work upon the political development of postwar Germany have been his first lasting achievement. His books helped to pave the way for West Germany's abandoning the territorial revisionism of the Adenauer era and to facilitate the emergence of Brandt's Ostpolitik . For the first time since the Wilhelmine period, Germany became willing to recognize the existing frontiers in Europe and to pursue a policy of reconciliation toward those countries of eastern Europe that had suffered from German expansionism in two world wars. The lesson had at last been learned from the disastrous course that German foreign policy had taken in the first half of the 20th century.

There is yet another mark that Fischer's work left, this time on the historical profession of the Federal Republic. Methodologically speaking, his books may have been rather traditional, focusing as they did on high politics and decision-making elites. But his challenge to interpretations of German history that had entrenched themselves in early postwar Germany encouraged a younger generation of historians who were not members of the "Fischer School" to move beyond Fischer's kind of political history and toward the analysis of the country's social and economic structures and political-cultural traditions since 1871. The history of the German Empire became a major field of research, attracting also many non-German scholars, and the work they undertook has yielded very fruitful results as well as fresh arguments.

If the imperial period offers rich material also to the teacher of modern European history on both sides of the Atlantic today, it is in no small degree thanks to the breach that Fischer made, and the courageous stand that he took, in rejecting the historiographical orthodoxies of the early postwar period. His achievements as a scholar and as a man of firm convictions and great integrity were recognized by the many honorary doctorates that he received from universities around the world. The president of the Federal Republic awarded him the Bundesverdienstkreuz 1. Klasse.

Fritz Fischer is survived by his wife Margarete, his two children, and five grandchildren.

—Volker Berghahn teaches at Columbia University.

Tags: In Memoriam

The American Historical Association welcomes comments in the discussion area below, at AHA Communities , and in letters to the editor . Please read our commenting and letters policy before submitting.

Please read our commenting and letters policy before submitting.

In This Section

New Journal of Chemistry

Determining the hydrocarbon chain growth pathway in fischer–tropsch synthesis through dft calculations: impact of cobalt cluster size †.

* Corresponding authors

a Department of Chemical Engineering, Faculty of Engineering, Ferdowsi University of Mashhad, Mashhad, Iran E-mail: [email protected] , [email protected]

b Department of Chemistry, Faculty of Science, Ferdowsi University of Mashhad, Mashhad, Iran E-mail: [email protected] , [email protected] , [email protected] Tel: +985138805539

In the present work, the barrier energies ( E b ) of CH 4 formation and C–C coupling and the mechanism of Fischer–Tropsch synthesis (FTS) on different cluster sizes of cobalt were investigated. Three cobalt clusters with 10, 18, and 30 atoms (Co-10, Co-18, and Co-30) were used for comparison of the results. The E b , transition state, and reaction energy (Δ E r ) were analyzed by using density functional theory (DFT) calculations. The results showed that CH 4 was produced more easily on the small cluster (Co-10) than on the other two clusters. The E b values for the Co-10, Co-18, and Co-30 clusters were 1.62, 2.53, and 2.44 eV, respectively. The E b values for dissociation of CO on the three clusters Co-10, Co-18, and Co-30 were 1.64, 0.93, and 1.81 eV, respectively, and the minimum E b was related to the Co-18 cluster. Also, the tendency towards chain growth increased with increasing cobalt cluster size. The results showed that the mechanism of the FTS reaction was dependent on the particle size of the cobalt clusters. It can be concluded that the Co-10 cluster followed the CO insertion mechanism and the Co-18 cluster followed the carbide mechanism in the FTS reaction. Also, the Co-30 cluster followed both mechanisms (CO insertion and carbide mechanisms) in the FTS reaction. DFT results showed that as the cobalt cluster size increased, the olefin/paraffin ratio in the FTS reaction products enhanced.

Supplementary files

- Supplementary information PDF (3116K)

Article information

Download citation, permissions.

Determining the hydrocarbon chain growth pathway in Fischer–Tropsch synthesis through DFT calculations: impact of cobalt cluster size

S. Veiskarami, A. Nakheai Pour, E. Saljoughi and A. Mohammadi, New J. Chem. , 2024, Advance Article , DOI: 10.1039/D4NJ01435A

To request permission to reproduce material from this article, please go to the Copyright Clearance Center request page .

If you are an author contributing to an RSC publication, you do not need to request permission provided correct acknowledgement is given.

If you are the author of this article, you do not need to request permission to reproduce figures and diagrams provided correct acknowledgement is given. If you want to reproduce the whole article in a third-party publication (excluding your thesis/dissertation for which permission is not required) please go to the Copyright Clearance Center request page .

Read more about how to correctly acknowledge RSC content .

Social activity

Search articles by author.

This article has not yet been cited.

Advertisements

COMMENTS

The Fischer Thesis. The first major challenge to this interpretation was advanced in Germany in the 1960s, where the historian Fritz Fischer published a startling new thesis which threatened to overthrow the existing consensus. Germany, he argued, did have the main share of responsibility for the outbreak of the war. ...

The breadth of scholarship produced since the 1970s had not only chipped away at the Fischer thesis; it had also enlarged historians' understandings of foreign policy making before 1914. The clarity of Fischer's thesis had less purchase against the background of the evident complexity of international politics. In historiographical terms ...

Instead, Fischer's thesis was a powerful confirmation of the much-hated decision of the victorious allies in 1919 to make Germany responsible for the war.3 After the Second World War, for the outbreak of which Germany could not deny responsi bility, revisiting the causes of the First seemed unnecessarily soul-searching; as a

Germany's Aims in the First World War (German title: Griff nach der Weltmacht: Die Kriegzielpolitik des kaiserlichen Deutschland 1914-1918) is a book by German historian Fritz Fischer.It is one of the leading contributions to historical analysis of the causes of World War I, and along with this work War of Illusions (Krieg der Illusionen) gave rise to the "Fischer Thesis" on the causes of ...

Opposition to the Fischer thesis. The "Berlin War Party" thesis and variants of it, blaming domestic German political factors, became something of an orthodoxy in the years after publication. Nonetheless many authors have attacked it. German conservative historians such as Gerhard Ritter asserted that the thesis was dishonest and inaccurate.

The Fischer thesis, the new revisionism and the meaning of the First World War Get access. JOHN C. G. RÖHL. JOHN C. G. RÖHL 1 Taught at the University of Sussex from 1964 until his retirement in 1999, serving as Dean of the School of European Studies from 1982 to 1985.

the way primary sources drove Fischer's argument as well as the document-rich quality of his publications defined both the nature of the contemporary responses to his thesis and the way in which historians have conducted their enqui ries into the origins of the war ever since. Here, Fischer's positivist approach to

Fritz Fischer (5 March 1908 - 1 December 1999) was a German historian best known for his analysis of the causes of World War I.In the early 1960s Fischer advanced the controversial thesis at the time that responsibility for the outbreak of the war rested solely on Imperial Germany.Fischer's anti-revisionist claims shocked the West German government and historical establishment, as it made ...

were working closely with Fritz Fischer in Hamburg. Fischer's sensational book Griff nach der Weltmacht had just then revealed the extent of Germany's war aims throughout the First World War, strongly suggesting that it had sought war in 1914 in order to attain those aims. 4 It was through Hartmut Pogge that I met Fritz Fischer in Oxford in ...

But in this centennial year Fischer's conclusions have in turn been challenged by historians claiming that Europe's leaders all 'sleepwalked' into the catastrophe. ... Lecture held at the University of Sussex in November 2014, explores the archival discoveries which underpinned the Fischer thesis of the 1960s and subsequent research, and ...

subtitle, "Professor Fischer's thesis of sole guilt for the First World War will still kindle many discussions."?That the word "Weltmacht" was used to mean the desire to be equal with the three "world powers" ofthe time, the British Empire, the U.S.A., and Russia, was explained on the cover of the book and in the book, passim. 207

The thesis that Germany had pushed more for war in 1914 than any other power electrified the debate in the public. His demolition of politically and historically 'comfortable' views led to a strong defensive reaction among conservative historians. ... He came to Oxford in 1962 on the recommendation of Fritz Fischer, taught also at Sussex ...

Annika Mombauer is Senior Lecturer in Modern History at The Open University, Milton Keynes. Her research focuses on the origins of the First World War and the history of Imperial Germany. Her publications include Helmuth von Moltke and the Origins of the First World War (Cambridge 2001), The Origins of the First World War.Controversies and Consensus (London 2002) and The Origins of the First ...

Twenty-Five Years Later: Looking Back at the "Fischer Controversy" and Its Consequences - Volume 21 Issue 3. ... "Professor Fischer's thesis of sole guilt for the First World War will still kindle many discussions."—That the word "Weltmacht" was used to mean the desire to be equal with the three "world powers" of the time, ...

Fritz Fischer's 1961 Griff nach der Weltmacht enjoys a well-deserved reputation as a landmark in later twentieth-century German historiography. The impact of the so-called 'Fischer controversy' on British scholarship, by contrast, was varied and ambiguous. Even so, the reaction of British historians to Fischer's work as such and the fierce public debate it generated in West Germany is ...

Fritz Fischer (1908-99) Fritz Fischer, professor emeritus at Hamburg University and one of the most influential historians of modern Germany since 1945, died on December 1, 1999 at the age of 91. He was named an Honorary Foreign Member of the AHA in 1984. Born on March 5, 1908 in Upper Franconia in southern Germany, he embarked upon the long ...

This article, the text of the Martin Wight Memorial Lecture held at the University of Sussex in November 2014, explores the archival discoveries which underpinned the Fischer thesis of the 1960s and subsequent research, and asks with what justification such evidence is now being set aside by the new revisionism.

Fischer's thesis sparked bitter debate and a rash of new interpretations of World War I. Leftist historians made connections between Fischer's evidence and that cited 30 years before by Eckhart Kehr, who had traced the social origins of the naval program to the cleavages in German society and the stalemate in the Reichstag.

Fischer's thesis survived the challenges of his countrymen. Historians in the United States, like those in Europe, tended to concede the validity of Fischer's data while disputing his conclusions. Joachim Remak proclaimed the end of "Fritz Fischer's decade" in a celebrated article in 1971,'3 but his analysis gave scant attention to

The immediate impact of Fischer's thesis in West Germany, an insecure and exposed divided country on the front line of the Cold War, is investigated by Hartmut Pogge von Strandmann. He highlights in particular the international and national crises which occurred concurrently with Fischer's controversial pub-lication.

The Fischer controversy of the 1960s was a major landmark in post-war West German historiography. Surprisingly few historians to date have devoted their attention to the East German reception of Fischer's work, however. This article seeks to fill this gap by looking at some of the critical reviews published in East German academic journals and ...

In the present work, the barrier energies (Eb) of CH4 formation and C-C coupling and the mechanism of Fischer-Tropsch synthesis (FTS) on different cluster sizes of cobalt were investigated. Three cobalt clusters with 10, 18, and 30 atoms (Co-10, Co-18, and Co-30) were used for comparison of the results. The Eb, tra

Fritz Fischer. Fritz Fischer may refer to: Fritz Fischer (historian) (1908-1999), German historian. Fritz Fischer (medical doctor) (1912-2003), Waffen-SS doctor. Fritz Fischer (biathlete) (born 1956), German biathlete. Fritz Fischer (physicist) (1898-1947), Swiss physicist. Category: Human name disambiguation pages.

programme' was quickly sidelined as a topic during the early years of the Fischer con troversy. This article explores this absence. It analyses the historiographical place of the revolution programme in the Fischer controversy and argues for a general re-evaluation of Fischer's work in order to raise questions about how Germany's Aims could contrib