- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

This Day In History : October 31

Changing the day will navigate the page to that given day in history. You can navigate days by using left and right arrows

Martin Luther posts 95 theses

On October 31, 1517, legend has it that the priest and scholar Martin Luther approaches the door of the Castle Church in Wittenberg, Germany, and nails a piece of paper to it containing the 95 revolutionary opinions that would begin the Protestant Reformation .

In his theses, Luther condemned the excesses and corruption of the Roman Catholic Church, especially the papal practice of asking payment—called “indulgences”—for the forgiveness of sins. At the time, a Dominican priest named Johann Tetzel, commissioned by the Archbishop of Mainz and Pope Leo X, was in the midst of a major fundraising campaign in Germany to finance the renovation of St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome. Though Prince Frederick III the Wise had banned the sale of indulgences in Wittenberg, many church members traveled to purchase them. When they returned, they showed the pardons they had bought to Luther, claiming they no longer had to repent for their sins.

Luther’s frustration with this practice led him to write the 95 Theses, which were quickly snapped up, translated from Latin into German and distributed widely. A copy made its way to Rome, and efforts began to convince Luther to change his tune. He refused to keep silent, however, and in 1521 Pope Leo X formally excommunicated Luther from the Catholic Church. That same year, Luther again refused to recant his writings before the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V of Germany, who issued the famous Edict of Worms declaring Luther an outlaw and a heretic and giving permission for anyone to kill him without consequence. Protected by Prince Frederick, Luther began working on a German translation of the Bible, a task that took 10 years to complete.

The term “Protestant” first appeared in 1529, when Charles V revoked a provision that allowed the ruler of each German state to choose whether they would enforce the Edict of Worms. A number of princes and other supporters of Luther issued a protest, declaring that their allegiance to God trumped their allegiance to the emperor. They became known to their opponents as Protestants; gradually this name came to apply to all who believed the Church should be reformed, even those outside Germany. By the time Luther died, of natural causes, in 1546, his revolutionary beliefs had formed the basis for the Protestant Reformation, which would over the next three centuries revolutionize Western civilization.

Also on This Day in History October | 31

Freak explosion at Indiana State Fairgrounds Coliseum kills nearly 100

Violet palmer becomes first woman to officiate an nba game, this day in history video: what happened on october 31, stalin’s body removed from lenin’s tomb, celebrated magician harry houdini dies, earl lloyd becomes first black player in the nba.

Wake Up to This Day in History

Sign up now to learn about This Day in History straight from your inbox. Get all of today's events in just one email featuring a range of topics.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

The U.S. Congress admits Nevada as the 36th state

Ed sullivan witnesses beatlemania firsthand, paving the way for the british invasion, actor river phoenix dies, indian prime minister indira gandhi is assassinated, king george iii speaks for first time since american independence declared.

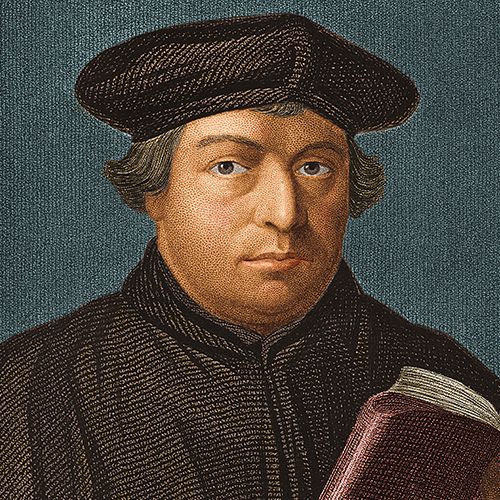

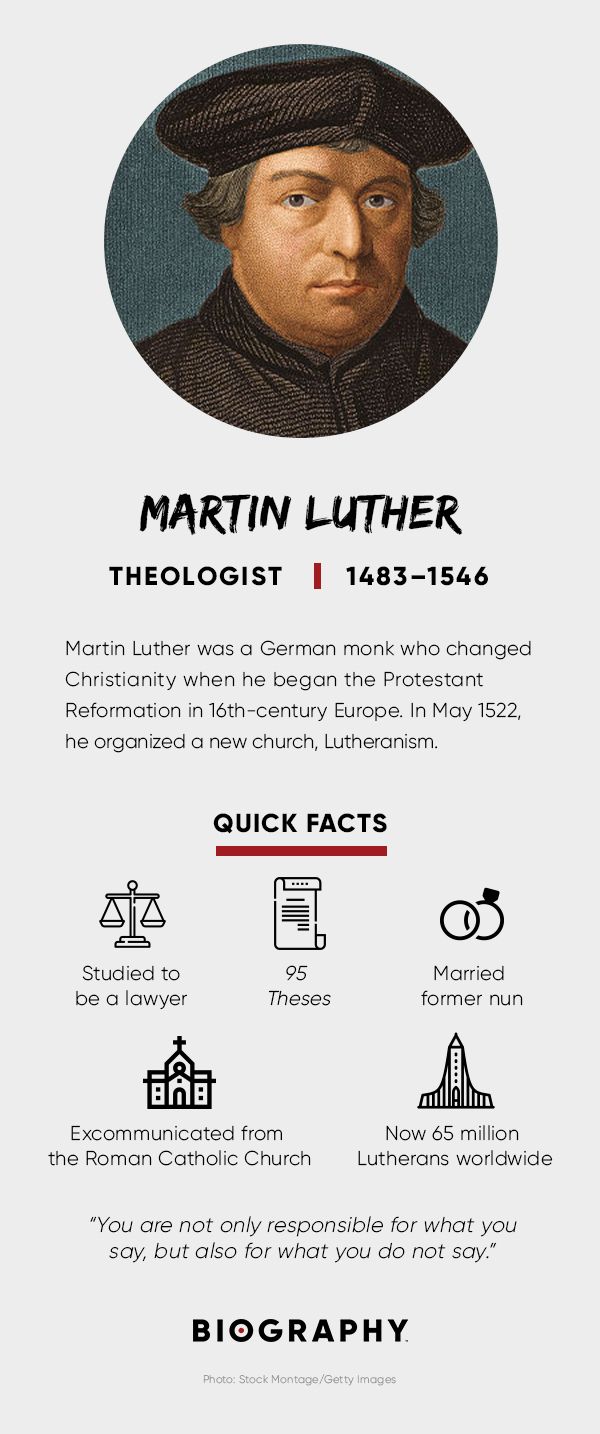

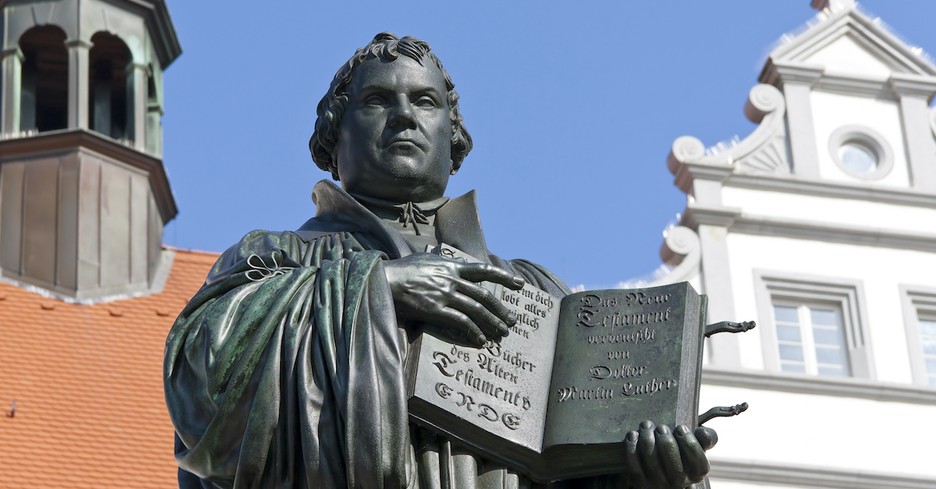

Martin Luther

(1483-1546)

Who Was Martin Luther?

Luther called into question some of the basic tenets of Roman Catholicism, and his followers soon split from the Roman Catholic Church to begin the Protestant tradition. His actions set in motion tremendous reform within the Church.

A prominent theologian, Luther’s desire for people to feel closer to God led him to translate the Bible into the language of the people, radically changing the relationship between church leaders and their followers.

Luther was born on November 10, 1483, in Eisleben, Saxony, located in modern-day Germany.

His parents, Hans and Margarette Luther, were of peasant lineage. However, Hans had some success as a miner and ore smelter, and in 1484 the family moved from Eisleben to nearby Mansfeld, where Hans held ore deposits.

Hans Luther knew that mining was a tough business and wanted his promising son to have a better career as a lawyer. At age seven, Luther entered school in Mansfeld.

At 14, Luther went north to Magdeburg, where he continued his studies. In 1498, he returned to Eisleben and enrolled in a school, studying grammar, rhetoric and logic. He later compared this experience to purgatory and hell.

In 1501, Luther entered the University of Erfurt , where he received a degree in grammar, logic, rhetoric and metaphysics. At this time, it seemed he was on his way to becoming a lawyer.

Becoming a Monk

In July 1505, Luther had a life-changing experience that set him on a new course to becoming a monk.

Caught in a horrific thunderstorm where he feared for his life, Luther cried out to St. Anne, the patron saint of miners, “Save me, St. Anne, and I’ll become a monk!” The storm subsided and he was saved.

Most historians believe this was not a spontaneous act, but an idea already formulated in Luther’s mind. The decision to become a monk was difficult and greatly disappointed his father, but he felt he must keep a promise.

Luther was also driven by fears of hell and God’s wrath, and felt that life in a monastery would help him find salvation.

The first few years of monastic life were difficult for Luther, as he did not find the religious enlightenment he was seeking. A mentor told him to focus his life exclusively on Jesus Christ and this would later provide him with the guidance he sought.

Disillusionment with Rome

At age 27, Luther was given the opportunity to be a delegate to a Catholic church conference in Rome. He came away more disillusioned, and very discouraged by the immorality and corruption he witnessed there among the Catholic priests.

Upon his return to Germany, he enrolled in the University of Wittenberg in an attempt to suppress his spiritual turmoil. He excelled in his studies and received a doctorate, becoming a professor of theology at the university (known today as Martin Luther University Halle-Wittenberg ).

Through his studies of scripture, Luther finally gained religious enlightenment. Beginning in 1513, while preparing lectures, Luther read the first line of Psalm 22, which Christ wailed in his cry for mercy on the cross, a cry similar to Luther’s own disillusionment with God and religion.

Two years later, while preparing a lecture on Paul’s Epistle to the Romans, he read, “The just will live by faith.” He dwelled on this statement for some time.

Finally, he realized the key to spiritual salvation was not to fear God or be enslaved by religious dogma but to believe that faith alone would bring salvation. This period marked a major change in his life and set in motion the Reformation.

DOWNLOAD BIOGRAPHY'S MARTIN LUTHER FACT CARD

'95 Theses'

On October 31, 1517, Luther, angry with Pope Leo X’s new round of indulgences to help build St. Peter’s Basilica , nailed a sheet of paper with his 95 Theses on the University of Wittenberg’s chapel door.

Though Luther intended these to be discussion points, the 95 Theses laid out a devastating critique of the indulgences - good works, which often involved monetary donations, that popes could grant to the people to cancel out penance for sins - as corrupting people’s faith.

Luther also sent a copy to Archbishop Albert Albrecht of Mainz, calling on him to end the sale of indulgences. Aided by the printing press , copies of the 95 Theses spread throughout Germany within two weeks and throughout Europe within two months.

The Church eventually moved to stop the act of defiance. In October 1518, at a meeting with Cardinal Thomas Cajetan in Augsburg, Luther was ordered to recant his 95 Theses by the authority of the pope.

Luther said he would not recant unless scripture proved him wrong. He went further, stating he didn’t consider that the papacy had the authority to interpret scripture. The meeting ended in a shouting match and initiated his ultimate excommunication from the Church.

Excommunication

Following the publication of his 95 Theses , Luther continued to lecture and write in Wittenberg. In June and July of 1519 Luther publicly declared that the Bible did not give the pope the exclusive right to interpret scripture, which was a direct attack on the authority of the papacy.

Finally, in 1520, the pope had had enough and on June 15 issued an ultimatum threatening Luther with excommunication.

On December 10, 1520, Luther publicly burned the letter. In January 1521, Luther was officially excommunicated from the Roman Catholic Church.

Diet of Worms

In March 1521, Luther was summoned before the Diet of Worms , a general assembly of secular authorities. Again, Luther refused to recant his statements, demanding he be shown any scripture that would refute his position. There was none.

On May 8, 1521, the council released the Edict of Worms, banning Luther’s writings and declaring him a “convicted heretic.” This made him a condemned and wanted man. Friends helped him hide out at the Wartburg Castle.

While in seclusion, he translated the New Testament into the German language, to give ordinary people the opportunity to read God’s word.

Lutheran Church

Though still under threat of arrest, Luther returned to Wittenberg Castle Church, in Eisenach, in May 1522 to organize a new church, Lutheranism.

He gained many followers, and the Lutheran Church also received considerable support from German princes.

When a peasant revolt began in 1524, Luther denounced the peasants and sided with the rulers, whom he depended on to keep his church growing. Thousands of peasants were killed, but the Lutheran Church grew over the years.

Katharina von Bora

In 1525, Luther married Katharina von Bora, a former nun who had abandoned the convent and taken refuge in Wittenberg.

Born into a noble family that had fallen on hard times, at the age of five Katharina was sent to a convent. She and several other reform-minded nuns decided to escape the rigors of the cloistered life, and after smuggling out a letter pleading for help from the Lutherans, Luther organized a daring plot.

With the help of a fishmonger, Luther had the rebellious nuns hide in herring barrels that were secreted out of the convent after dark - an offense punishable by death. Luther ensured that all the women found employment or marriage prospects, except for the strong-willed Katharina, who refused all suitors except Luther himself.

The scandalous marriage of a disgraced monk to a disgraced nun may have somewhat tarnished the reform movement, but over the next several years, the couple prospered and had six children.

Katharina proved herself a more than a capable wife and ally, as she greatly increased their family's wealth by shrewdly investing in farms, orchards and a brewery. She also converted a former monastery into a dormitory and meeting center for Reformation activists.

Luther later said of his marriage, "I have made the angels laugh and the devils weep." Unusual for its time, Luther in his will entrusted Katharina as his sole inheritor and guardian of their children.

Anti-Semitism

From 1533 to his death in 1546, Luther served as the dean of theology at University of Wittenberg. During this time he suffered from many illnesses, including arthritis, heart problems and digestive disorders.

The physical pain and emotional strain of being a fugitive might have been reflected in his writings.

Some works contained strident and offensive language against several segments of society, particularly Jews and, to a lesser degree, Muslims. Luther's anti-Semitism is on full display in his treatise, The Jews and Their Lies .

Luther died following a stroke on February 18, 1546, at the age of 62 during a trip to his hometown of Eisleben. He was buried in All Saints' Church in Wittenberg, the city he had helped turn into an intellectual center.

Luther's teachings and translations radically changed Christian theology. Thanks in large part to the Gutenberg press, his influence continued to grow after his death, as his message spread across Europe and around the world.

QUICK FACTS

- Name: Luther Martin

- Birth Year: 1483

- Birth date: November 10, 1483

- Birth City: Eisleben

- Birth Country: Germany

- Gender: Male

- Best Known For: Martin Luther was a German monk who forever changed Christianity when he nailed his '95 Theses' to a church door in 1517, sparking the Protestant Reformation.

- Christianity

- Astrological Sign: Scorpio

- Nacionalities

- Interesting Facts

- Martin Luther studied to be a lawyer before deciding to become a monk.

- Luther refused to recant his '95 Theses' and was excommunicated from the Catholic Church.

- Luther married a former nun and they went on to have six children.

- Death Year: 1546

- Death date: February 18, 1546

- Death City: Eisleben

- Death Country: Germany

We strive for accuracy and fairness.If you see something that doesn't look right, contact us !

CITATION INFORMATION

- Article Title: Martin Luther Biography

- Author: Biography.com Editors

- Website Name: The Biography.com website

- Url: https://www.biography.com/religious-figures/martin-luther

- Access Date:

- Publisher: A&E; Television Networks

- Last Updated: September 20, 2019

- Original Published Date: April 2, 2014

- To be a Christian without prayer is no more possible than to be alive without breathing.

- God writes the Gospel not in the Bible alone, but also on trees, and in the flowers and clouds and stars.

- Let the wife make the husband glad to come home, and let him make her sorry to see him leave.

- You are not only responsible for what you say, but also for what you do not say.

Famous Religious Figures

7 Little-Known Facts About Saint Patrick

Saint Nicholas

Jerry Falwell

Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh

Saint Thomas Aquinas

History of the Dalai Lama's Biggest Controversies

Saint Patrick

Pope Benedict XVI

John Calvin

Pontius Pilate

- Ancient Rome

- Medieval England

- Stuart England

- World War One

- World War Two

- Modern World History

- Philippines

- History Learning >

- The German Reformation >

- The 95 Theses

On 31 October 1517, Martin Luther pinned the 95 Theses next to the sale of indulgences to the door of the main church in Wittenberg. Although Luther could never have foreseen the impact of this act, it served to trigger the German Reformation. The main idea of the 95 Theses was that the Church’s teaching on salvation were incorrect and that the Bible revealed God’s true will.

In his early years, Luther had accepted the teachings of the Church. However, over time they began to trouble him. He feared that he would never gain salvation, as leading a completely sin-free life was almost impossible. His despair worsened when, in 1517, the Dominican friar John Tetzel was empowered by the pope to fund the restoration of buildings in Rome by selling indulgences. Tetzel’s sermons became advertisements for the expensive indulgences, which would ensure the forgiveness of all the purchaser’s sins. It also promised the release of a loved one from purgatory. Churchgoers would sing:

“As soon as the coin in the coffer rings, So the soul from purgatory springs.”

Luther felt that the Church was exploiting its members for its own gain. He saw it as an example of the “rottenness” of the Church.

The Church’s actions inspired Luther to write The 95 Theses. The pamphlet contained 95 points that he felt should be argued at an academic level.

Whether Luther intended for his pamphlet to be read by a wide audience is up for debate. On the one hand, it was written in Latin which was the traditional language of the scholar. Thus, few people in Wittenberg would have been able to read it.

On the other hand, the timing suggests that he was hoping for his arguments to receive wide publicity. The 95 Theses appeared only the day before the Elector of Saxony sold indulgences to visitors of his holy relics.

Even if Luther didn’t intend for it to happen, the 95 Theses were soon translated into German, printed and widely distributed. His ideas had wide appeal - scholars approved of the theory behind Luther’s arguments, and the public were happy to find they could have salvation regardless of their wealth.

Luther’s ideas spread across Germany through the traders that travelled through Wittenberg. Moreover, it helped that his ideas had a populist appeal.

See also: The 95 Theses - A Modern Translation

MLA Citation/Reference

"The 95 Theses". HistoryLearning.com. 2024. Web.

Related Pages

- Quotes from the Nuremberg Trials

- Germany in 1900

- Germany 1939

- General Kurt Student

- General Dietrich von Choltitz

- Heinz Guderian

- Erwin Rommel

- Erhard Milch

- Wilhelm Canaris

The 95 Theses , a document written by Martin Luther in 1517, challenged the teachings of the Catholic Church on the nature of penance, the authority of the pope and the usefulness of indulgences. It sparked a theological debate that fueled the Reformation and subsequently resulted in the birth of Protestantism and the Lutheran , Reformed , and Anabaptist traditions within Christianity.

Luther's action was in great part a response to the selling of indulgences by Johann Tetzel, a Dominican priest, commissioned by the Archbishop of Mainz and Pope Leo X. The purpose of this fundraising campaign was to finance the building of St. Peter's Basilica in Rome. Even though Luther's prince, Frederick the Wise, and the prince of the neighboring territory, George, Duke of Saxony, forbade the sale in their lands, Luther's parishioners traveled to purchase them. When these people came to confession, they presented the plenary indulgence, claiming they no longer had to repent of their sins, since the document promised to forgive all their sins.

Luther is said to have posted the 95 Theses on the door of the Castle Church in Wittenberg, Germany, on October 31, 1517. Church doors functioned very much as bulletin boards function on a twenty-first century college campus. The 95 Theses were quickly translated into German, widely copied and printed. Within two weeks they had spread throughout Germany, and within two months throughout Europe. This was one of the first events in history that was profoundly affected by the printing press, which made the distribution of documents and ideas easier and more wide-spread.

Text of the 95 Theses

**Disputation of Doctor Martin Luther\ on the Power and Efficacy of Indulgences

by Dr. Martin Luther, 1517** Out of love for the truth and the desire to bring it to light, the following propositions will be discussed at Wittenberg, under the presidency of the Reverend Father Martin Luther, Master of Arts and of Sacred Theology, and Lecturer in Ordinary on the same at that place. Wherefore he requests that those who are unable to be present and debate orally with us, may do so by letter.

In the Name our Lord Jesus Christ. Amen.

- Our Lord and Master Jesus Christ, when He said Poenitentiam agite, willed that the whole life of believers should be repentance.

- This word cannot be understood to mean sacramental penance, i.e., confession and satisfaction, which is administered by the priests.

- Yet it means not inward repentance only; nay, there is no inward repentance which does not outwardly work divers mortifications of the flesh.

- The penalty [of sin], therefore, continues so long as hatred of self continues; for this is the true inward repentance, and continues until our entrance into the kingdom of heaven.

- The pope does not intend to remit, and cannot remit any penalties other than those which he has imposed either by his own authority or by that of the Canons.

- The pope cannot remit any guilt, except by declaring that it has been remitted by God and by assenting to God's remission; though, to be sure, he may grant remission in cases reserved to his judgment. If his right to grant remission in such cases were despised, the guilt would remain entirely unforgiven.

- God remits guilt to no one whom He does not, at the same time, humble in all things and bring into subjection to His vicar, the priest.

- The penitential canons are imposed only on the living, and, according to them, nothing should be imposed on the dying.

- Therefore the Holy Spirit in the pope is kind to us, because in his decrees he always makes exception of the article of death and of necessity.

- Ignorant and wicked are the doings of those priests who, in the case of the dying, reserve canonical penances for purgatory.

- This changing of the canonical penalty to the penalty of purgatory is quite evidently one of the tares that were sown while the bishops slept.

- In former times the canonical penalties were imposed not after, but before absolution, as tests of true contrition.

- The dying are freed by death from all penalties; they are already dead to canonical rules, and have a right to be released from them.

- The imperfect health [of soul], that is to say, the imperfect love, of the dying brings with it, of necessity, great fear; and the smaller the love, the greater is the fear.

- This fear and horror is sufficient of itself alone (to say nothing of other things) to constitute the penalty of purgatory, since it is very near to the horror of despair.

- Hell, purgatory, and heaven seem to differ as do despair, almost-despair, and the assurance of safety.

- With souls in purgatory it seems necessary that horror should grow less and love increase.

- It seems unproved, either by reason or Scripture, that they are outside the state of merit, that is to say, of increasing love.

- Again, it seems unproved that they, or at least that all of them, are certain or assured of their own blessedness, though we may be quite certain of it.

- Therefore by "full remission of all penalties" the pope means not actually "of all," but only of those imposed by himself.

- Therefore those preachers of indulgences are in error, who say that by the pope's indulgences a man is freed from every penalty, and saved;

- Whereas he remits to souls in purgatory no penalty which, according to the canons, they would have had to pay in this life.

- If it is at all possible to grant to any one the remission of all penalties whatsoever, it is certain that this remission can be granted only to the most perfect, that is, to the very fewest.

- It must needs be, therefore, that the greater part of the people are deceived by that indiscriminate and highsounding promise of release from penalty.

- The power which the pope has, in a general way, over purgatory, is just like the power which any bishop or curate has, in a special way, within his own diocese or parish.

- The pope does well when he grants remission to souls [in purgatory], not by the power of the keys (which he does not possess), but by way of intercession.

- They preach man who say that so soon as the penny jingles into the money-box, the soul flies out [of purgatory].

- It is certain that when the penny jingles into the money-box, gain and avarice can be increased, but the result of the intercession of the Church is in the power of God alone.

- Who knows whether all the souls in purgatory wish to be bought out of it, as in the legend of Sts. Severinus and Paschal.

- No one is sure that his own contrition is sincere; much less that he has attained full remission.

- Rare as is the man that is truly penitent, so rare is also the man who truly buys indulgences, i.e., such men are most rare.

- They will be condemned eternally, together with their teachers, who believe themselves sure of their salvation because they have letters of pardon.

- Men must be on their guard against those who say that the pope's pardons are that inestimable gift of God by which man is reconciled to Him;

- For these "graces of pardon" concern only the penalties of sacramental satisfaction, and these are appointed by man.

- They preach no Christian doctrine who teach that contrition is not necessary in those who intend to buy souls out of purgatory or to buy confessionalia.

- Every truly repentant Christian has a right to full remission of penalty and guilt, even without letters of pardon.

- Every true Christian, whether living or dead, has part in all the blessings of Christ and the Church; and this is granted him by God, even without letters of pardon.

- Nevertheless, the remission and participation [in the blessings of the Church] which are granted by the pope are in no way to be despised, for they are, as I have said, the declaration of divine remission.

- It is most difficult, even for the very keenest theologians, at one and the same time to commend to the people the abundance of pardons and [the need of] true contrition.

- True contrition seeks and loves penalties, but liberal pardons only relax penalties and cause them to be hated, or at least, furnish an occasion [for hating them].

- Apostolic pardons are to be preached with caution, lest the people may falsely think them preferable to other good works of love.

- Christians are to be taught that the pope does not intend the buying of pardons to be compared in any way to works of mercy.

- Christians are to be taught that he who gives to the poor or lends to the needy does a better work than buying pardons;

- Because love grows by works of love, and man becomes better; but by pardons man does not grow better, only more free from penalty.

- Christians are to be taught that he who sees a man in need, and passes him by, and gives [his money] for pardons, purchases not the indulgences of the pope, but the indignation of God.

- Christians are to be taught that unless they have more than they need, they are bound to keep back what is necessary for their own families, and by no means to squander it on pardons.

- Christians are to be taught that the buying of pardons is a matter of free will, and not of commandment.

- Christians are to be taught that the pope, in granting pardons, needs, and therefore desires, their devout prayer for him more than the money they bring.

- Christians are to be taught that the pope's pardons are useful, if they do not put their trust in them; but altogether harmful, if through them they lose their fear of God.

- Christians are to be taught that if the pope knew the exactions of the pardon-preachers, he would rather that St. Peter's church should go to ashes, than that it should be built up with the skin, flesh and bones of his sheep.

- Christians are to be taught that it would be the pope's wish, as it is his duty, to give of his own money to very many of those from whom certain hawkers of pardons cajole money, even though the church of St. Peter might have to be sold.

- The assurance of salvation by letters of pardon is vain, even though the commissary, nay, even though the pope himself, were to stake his soul upon it.

- They are enemies of Christ and of the pope, who bid the Word of God be altogether silent in some Churches, in order that pardons may be preached in others.

- Injury is done the Word of God when, in the same sermon, an equal or a longer time is spent on pardons than on this Word.

- It must be the intention of the pope that if pardons, which are a very small thing, are celebrated with one bell, with single processions and ceremonies, then the Gospel, which is the very greatest thing, should be preached with a hundred bells, a hundred processions, a hundred ceremonies.

- The "treasures of the Church," out of which the pope grants indulgences, are not sufficiently named or known among the people of Christ.

- That they are not temporal treasures is certainly evident, for many of the vendors do not pour out such treasures so easily, but only gather them.

- Nor are they the merits of Christ and the Saints, for even without the pope, these always work grace for the inner man, and the cross, death, and hell for the outward man.

- St. Lawrence said that the treasures of the Church were the Church's poor, but he spoke according to the usage of the word in his own time.

- Without rashness we say that the keys of the Church, given by Christ's merit, are that treasure;

- For it is clear that for the remission of penalties and of reserved cases, the power of the pope is of itself sufficient.

- The true treasure of the Church is the Most Holy Gospel of the glory and the grace of God.

- But this treasure is naturally most odious, for it makes the first to be last.

- On the other hand, the treasure of indulgences is naturally most acceptable, for it makes the last to be first.

- Therefore the treasures of the Gospel are nets with which they formerly were wont to fish for men of riches.

- The treasures of the indulgences are nets with which they now fish for the riches of men.

- The indulgences which the preachers cry as the "greatest graces" are known to be truly such, in so far as they promote gain.

- Yet they are in truth the very smallest graces compared with the grace of God and the piety of the Cross.

- Bishops and curates are bound to admit the commissaries of apostolic pardons, with all reverence.

- But still more are they bound to strain all their eyes and attend with all their ears, lest these men preach their own dreams instead of the commission of the pope.

- He who speaks against the truth of apostolic pardons, let him be anathema and accursed!

- But he who guards against the lust and license of the pardon-preachers, let him be blessed!

- The pope justly thunders against those who, by any art, contrive the injury of the traffic in pardons.

- But much more does he intend to thunder against those who use the pretext of pardons to contrive the injury of holy love and truth.

- To think the papal pardons so great that they could absolve a man even if he had committed an impossible sin and violated the Mother of God -- this is madness.

- We say, on the contrary, that the papal pardons are not able to remove the very least of venial sins, so far as its guilt is concerned.

- It is said that even St. Peter, if he were now Pope, could not bestow greater graces; this is blasphemy against St. Peter and against the pope.

- We say, on the contrary, that even the present pope, and any pope at all, has greater graces at his disposal; to wit, the Gospel, powers, gifts of healing, etc., as it is written in I. Corinthians xii.

- To say that the cross, emblazoned with the papal arms, which is set up [by the preachers of indulgences], is of equal worth with the Cross of Christ, is blasphemy.

- The bishops, curates and theologians who allow such talk to be spread among the people, will have an account to render.

- This unbridled preaching of pardons makes it no easy matter, even for learned men, to rescue the reverence due to the pope from slander, or even from the shrewd questionings of the laity.

- To wit: -- "Why does not the pope empty purgatory, for the sake of holy love and of the dire need of the souls that are there, if he redeems an infinite number of souls for the sake of miserable money with which to build a Church? The former reasons would be most just; the latter is most trivial."

- Again: -- "Why are mortuary and anniversary masses for the dead continued, and why does he not return or permit the withdrawal of the endowments founded on their behalf, since it is wrong to pray for the redeemed?"

- Again: -- "What is this new piety of God and the pope, that for money they allow a man who is impious and their enemy to buy out of purgatory the pious soul of a friend of God, and do not rather, because of that pious and beloved soul's own need, free it for pure love's sake?"

- Again: -- "Why are the penitential canons long since in actual fact and through disuse abrogated and dead, now satisfied by the granting of indulgences, as though they were still alive and in force?"

- Again: -- "Why does not the pope, whose wealth is to-day greater than the riches of the richest, build just this one church of St. Peter with his own money, rather than with the money of poor believers?"

- Again: -- "What is it that the pope remits, and what participation does he grant to those who, by perfect contrition, have a right to full remission and participation?"

- Again: -- "What greater blessing could come to the Church than if the pope were to do a hundred times a day what he now does once, and bestow on every believer these remissions and participations?"

- "Since the pope, by his pardons, seeks the salvation of souls rather than money, why does he suspend the indulgences and pardons granted heretofore, since these have equal efficacy?"

- To repress these arguments and scruples of the laity by force alone, and not to resolve them by giving reasons, is to expose the Church and the pope to the ridicule of their enemies, and to make Christians unhappy.

- If, therefore, pardons were preached according to the spirit and mind of the pope, all these doubts would be readily resolved; nay, they would not exist.

- Away, then, with all those prophets who say to the people of Christ, "Peace, peace," and there is no peace!

- Blessed be all those prophets who say to the people of Christ, "Cross, cross," and there is no cross!

- Christians are to be exhorted that they be diligent in following Christ, their Head, through penalties, deaths, and hell;

- And thus be confident of entering into heaven rather through many tribulations, than through the assurance of peace.

- Martin Luther

- Reformation

External links

- The 95 Theses in the original Latin

- The 95 Theses in English

10 Things to Know about Martin Luther and His 95 Theses

Reformation Day on October 31 st reminds us of what the German theologian Martin Luther did for the Christian faith years ago, standing firm on his beliefs even when he had to stand before the Roman Catholic Church.

For many, the name Martin Luther would trigger thoughts of the great Martin Luther King Jr., standing in front of the Lincoln Memorial to share his I Have a Dream speech with thousands. However, there is another well-known Martin Luther who also was a leader and writer in his own right, composing the recognized 95 Theses that led to the establishment of the Protestant Reformation. With Reformation Day on October 31 st , let us journey back to the time of the German theologian to discover what led him to take a stand against the Roman Catholic Church and change the way we look at ourselves and our faith in God forever.

Ten Things to Know about Martin Luther and His 95 Theses:

1. Law and Lightning Contributed to Martin Luther’s Beginnings Martin Luther (Nov. 10, 1483 - Feb. 18, 1546) was a German theologian in Eisleben, Germany who attended Latin school as a child, and when he was thirteen years old, attended law school at the University of Erfurt. He was nicknamed “The Philosopher” because he did so well in public debates in school. However, it was one stormy night in 1505 that really changed Luther’s life. As he was walking, lightning struck the ground nearby and caused him to cry out to St. Anne and vow to become a monk if he lived; he did so he honored his vow and became a monk.

2. Questioning of the Roman Catholic Church Increased before Luther’s 95 Theses In the sixteenth century, many scholars and theologians were questioning some of the practices of the Roman Catholic Church. Fueled by the writings of church philosopher Augustine, these individuals believed that salvation came from God only (grace alone through faith alone), while the Catholic Church believed that faith and works were needed in response to God's grace. Today the Catholic Church would say that faith and the sacraments of the faith are needed for salvation (J.D. Crichton, Christian Celebration: The Sacraments). Luther especially followed Augustine’s belief of salvation and that the Bible was the only religious authority, not that of Catholic Church figures. He would later use these beliefs to build the foundation for the Protestant Reformation.

3. The Final Push for Change Began with a Scandal This questioning of the Catholic Church’s beliefs was intensified due to a scandal involving giving indulgences; indulgences (a type of payment for sin) were given to the church so those paying (or those they were paying on behalf of) would be absolved of sins. One could even purchase indulgences for the deceased. Germany had banned indulgence-selling but it was still happening nonetheless; this was especially evident when a friar named Johann Tetzel decided to sell indulgences in 1517 to pay for renovating Rome’s St. Peter’s Basilica. Luther and others had had enough at this point and decided something had to be done.

4. The First Copy of 95 Theses was Nailed to a Church Door Fed up by the behavior of Tetzel, Luther decided a public and academic debate was in order and he wrote the 95 Theses (also known as the “Disputation on the Power and Efficacy of Indulgences”) that listed some propositions and questions for debate. This he posted to the door of the Wittenberg Castle Church on October 31, 1517, in hopes that Archbishop Albert of Mainz, superior to Tetzel, would attend and also stop Tetzel from continuing to sell indulgences. Thanks to the invention of printing, the theses began to circulate around, and more people took notice and wanted answers from the Catholic Church.

5. The 95 Theses Called for Reform and Returning Repentance to God Written in a tone of questioning rather than accusing, the theses centered most on the first two theses Luther had written: that only faith leads to salvation and God desires for believers to seek repentance. The rest of the 93 theses focused on indulgences and why it didn’t line up with the first two theses. Luther even discussed the indulgence scandal involving St. Peter’s Basilica, questioning why the pope wouldn’t consider paying for the church’s renovations himself than taking from the poor (Thesis 86).

6. Luther Called to Defend His Teachings In the summer of 1518, many in Europe had been exposed to the 95 Theses, and Luther was called to Augsberg, Germany to defend his teachings of the theses. He was to present his theses to an assembly called a “diet,” led by the main anti-supporter of Luther, Cardinal Thomas Cajetan. After three days spent with the two men debating one another, a resolution couldn’t be reached, and Luther returned to Wittenberg.

7. The Pope Got Involved and Luther Was Called a Heretic Beginning on November 9, 1518, Pope Leo X stated that Luther’s teachings and position were in conflict with the church’s teachings, which led Luther to step down from public debate. However, others continued on without him and pushed against the church’s authority, strengthening the Protestant Reformation. Proceedings then continued in 1519 to examine more of Luther’s teachings, seeing them as scandalous and possibly heretical. However, it was in July 1520 that the pope considered Luther’s teachings heretical and demanded that he recant his beliefs or be excommunicated. Luther refused to yield.

8. Luther Was Excommunicated from the Roman Catholic Church On January 3, 1521, Luther was officially excommunicated from the Roman Catholic Church by Pope Leo X. Months later, April 17, 1521, Luther went before another assembly, the Diet of Worms, in Germany to see if he would recant his teachings, but he refused and a month later, on May 25, 1521, the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V signed an edict saying that Luther’s writings were to be burned. Luther’s return to Wittenberg in 1521 also showed him that the reforming from his 95 Theses was turning into a political debate and sparked the Peasants’ War in Germany; something he wasn’t for.

9. Luther Withdrew from Public View, Married, and Raised a Family Now apart from the Protestant Reformation, Luther preached, taught classes, and began a project that took him a decade to complete, translating the New Testament of the Bible into German. His translating actually impacted the German language positively, as it allowed more to understand what the Bible was teaching, and many scholars followed the same approach in interpretation. He also decided to get married to a former nun, Katherine of Bora, and they had five or six children together. Previously, Luther had debated against the Roman Catholic Church on clerical celibacy and also felt the Peasants’ War was God signaling the last days before Christ’s return so marriage was returning to God’s order for mankind.

10. Luther Established What Is Now Called Being a Polemical Theologian Luther went back to the town of his birth, Eisleben, Germany, to settle a dispute between friends while dealing with advancing poor health. Before he could return home to his wife and family, he passed away on February 18, 1546. Centuries since his death, many have more books of Luther’s writings in their houses than many other well-known theologians, while his approach to theology, that of polemical theology, is seen by some as hard to argue and reconcile with it being formed through argument and controversy. However, no one can deny that the efforts Martin Luther made toward reforming Christianity are nothing short of inspiring.

Reformation Day on October 31 st reminds us of what the German theologian Martin Luther did for the Christian faith years ago, standing firm on his beliefs even when he had to stand before the Roman Catholic Church. Martin Luther devoted his entire life to believing in a God who forgives and provides the whole way to salvation and freedom from sin through His Son Jesus. We could all take a lesson from Martin Luther nowadays, in a world that is still looking to sell and/or pay for indulgences in order to rectify their sins. It’s about returning to God in faith and seeking Him for the good works we are to do. Reading and believing the Bible, as well as daily prayer and interaction with God, were steps Martin Luther did to strengthen his trust and faith in God, and they are steps we can take too to bring hope in a challenging time.

Full 95 Theses from Martin Luther:

- When our Lord and Master Jesus Christ said, ``Repent'' ( Mt 4:17 ), he willed the entire life of believers to be one of repentance.

- This word cannot be understood as referring to the sacrament of penance, that is, confession and satisfaction, as administered by the clergy.

- Yet it does not mean solely inner repentance; such inner repentance is worthless unless it produces various outward mortification of the flesh.

- The penalty of sin remains as long as the hatred of self (that is, true inner repentance), namely till our entrance into the kingdom of heaven.

- The pope neither desires nor is able to remit any penalties except those imposed by his own authority or that of the canons.

- The pope cannot remit any guilt, except by declaring and showing that it has been remitted by God; or, to be sure, by remitting guilt in cases reserved to his judgment. If his right to grant remission in these cases were disregarded, the guilt would certainly remain unforgiven.

- God remits guilt to no one unless at the same time he humbles him in all things and makes him submissive to the vicar, the priest.

- The penitential canons are imposed only on the living, and, according to the canons themselves, nothing should be imposed on the dying.

- Therefore the Holy Spirit through the pope is kind to us insofar as the pope in his decrees always makes exception of the article of death and of necessity.

- Those priests act ignorantly and wickedly who, in the case of the dying, reserve canonical penalties for purgatory.

- Those tares of changing the canonical penalty to the penalty of purgatory were evidently sown while the bishops slept ( Mt 13:25 ).

- In former times canonical penalties were imposed, not after, but before absolution, as tests of true contrition.

- The dying are freed by death from all penalties, are already dead as far as the canon laws are concerned, and have a right to be released from them.

- Imperfect piety or love on the part of the dying person necessarily brings with it great fear; and the smaller the love, the greater the fear.

- This fear or horror is sufficient in itself, to say nothing of other things, to constitute the penalty of purgatory, since it is very near to the horror of despair.

- Hell, purgatory, and heaven seem to differ the same as despair, fear, and assurance of salvation .

- It seems as though for the souls in purgatory fear should necessarily decrease and love increase.

- Furthermore, it does not seem proved, either by reason or by Scripture, that souls in purgatory are outside the state of merit, that is, unable to grow in love.

- Nor does it seem proved that souls in purgatory, at least not all of them, are certain and assured of their own salvation, even if we ourselves may be entirely certain of it.

- Therefore the pope, when he uses the words ``plenary remission of all penalties,'' does not actually mean ``all penalties,'' but only those imposed by himself.

- Thus those indulgence preachers are in error who say that a man is absolved from every penalty and saved by papal indulgences.

- As a matter of fact, the pope remits to souls in purgatory no penalty which, according to canon law, they should have paid in this life.

- If remission of all penalties whatsoever could be granted to anyone at all, certainly it would be granted only to the most perfect, that is, to very few.

- For this reason most people are necessarily deceived by that indiscriminate and high-sounding promise of release from penalty.

- That power which the pope has in general over purgatory corresponds to the power which any bishop or curate has in a particular way in his own diocese and parish.

- The pope does very well when he grants remission to souls in purgatory, not by the power of the keys, which he does not have, but by way of intercession for them.

- They preach only human doctrines who say that as soon as the money clinks into the money chest, the soul flies out of purgatory.

- It is certain that when money clinks in the money chest, greed and avarice can be increased; but when the church intercedes, the result is in the hands of God alone.

- Who knows whether all souls in purgatory wish to be redeemed, since we have exceptions in St. Severinus and St. Paschal, as related in a legend.

- No one is sure of the integrity of his own contrition, much less of having received plenary remission.

- The man who actually buys indulgences is as rare as he who is really penitent; indeed, he is exceedingly rare.

- Those who believe that they can be certain of their salvation because they have indulgence letters will be eternally damned, together with their teachers.

- Men must especially be on guard against those who say that the pope's pardons are that inestimable gift of God by which man is reconciled to him.

- For the graces of indulgences are concerned only with the penalties of sacramental satisfaction established by man.

- They who teach that contrition is not necessary on the part of those who intend to buy souls out of purgatory or to buy confessional privileges preach unchristian doctrine.

- Any truly repentant Christian has a right to full remission of penalty and guilt, even without indulgence letters.

- Any true Christian, whether living or dead, participates in all the blessings of Christ and the church; and this is granted him by God, even without indulgence letters.

- Nevertheless, papal remission and blessing are by no means to be disregarded, for they are, as I have said (Thesis 6), the proclamation of the divine remission.

- It is very difficult, even for the most learned theologians, at one and the same time to commend to the people the bounty of indulgences and the need of true contrition.

- A Christian who is truly contrite seeks and loves to pay penalties for his sins; the bounty of indulgences, however, relaxes penalties and causes men to hate them -- at least it furnishes occasion for hating them.

- Papal indulgences must be preached with caution, lest people erroneously think that they are preferable to other good works of love.

- Christians are to be taught that the pope does not intend that the buying of indulgences should in any way be compared with works of mercy.

- Christians are to be taught that he who gives to the poor or lends to the needy does a better deed than he who buys indulgences.

- Because love grows by works of love, man thereby becomes better. Man does not, however, become better by means of indulgences but is merely freed from penalties.

- Christians are to be taught that he who sees a needy man and passes him by, yet gives his money for indulgences, does not buy papal indulgences but God's wrath.

- Christians are to be taught that, unless they have more than they need, they must reserve enough for their family needs and by no means squander it on indulgences.

- Christians are to be taught that the buying of indulgences is a matter of free choice, not commanded.

- Christians are to be taught that the pope, in granting indulgences, needs and thus desires their devout prayer more than their money.

- Christians are to be taught that papal indulgences are useful only if they do not put their trust in them, but very harmful if they lose their fear of God because of them.

- Christians are to be taught that if the pope knew the exactions of the indulgence preachers, he would rather that the basilica of St. Peter were burned to ashes than built up with the skin, flesh, and bones of his sheep.

- Christians are to be taught that the pope would and should wish to give of his own money, even though he had to sell the basilica of St. Peter, to many of those from whom certain hawkers of indulgences cajole money.

- It is vain to trust in salvation by indulgence letters, even though the indulgence commissary, or even the pope, were to offer his soul as security.

- They are the enemies of Christ and the pope who forbid altogether the preaching of the Word of God in some churches in order that indulgences may be preached in others.

- Injury is done to the Word of God when, in the same sermon, an equal or larger amount of time is devoted to indulgences than to the Word.

- It is certainly the pope's sentiment that if indulgences, which are a very insignificant thing, are celebrated with one bell, one procession, and one ceremony, then the gospel, which is the very greatest thing, should be preached with a hundred bells, a hundred processions, a hundred ceremonies.

- The true treasures of the church, out of which the pope distributes indulgences, are not sufficiently discussed or known among the people of Christ.

- That indulgences are not temporal treasures is certainly clear, for many indulgence sellers do not distribute them freely but only gather them.

- Nor are they the merits of Christ and the saints, for, even without the pope, the latter always work grace for the inner man, and the cross, death, and hell for the outer man.

- St. Lawrence said that the poor of the church were the treasures of the church, but he spoke according to the usage of the word in his own time.

- Without want of consideration we say that the keys of the church, given by the merits of Christ, are that treasure.

- For it is clear that the pope's power is of itself sufficient for the remission of penalties and cases reserved by himself.

- The true treasure of the church is the most holy gospel of the glory and grace of God.

- But this treasure is naturally most odious, for it makes the first to be last (Mt. 20:16).

- On the other hand, the treasure of indulgences is naturally most acceptable, for it makes the last to be first.

- Therefore the treasures of the gospel are nets with which one formerly fished for men of wealth.

- The treasures of indulgences are nets with which one now fishes for the wealth of men.

- The indulgences which the demagogues acclaim as the greatest graces are actually understood to be such only insofar as they promote gain.

- They are nevertheless in truth the most insignificant graces when compared with the grace of God and the piety of the cross.

- Bishops and curates are bound to admit the commissaries of papal indulgences with all reverence.

- But they are much more bound to strain their eyes and ears lest these men preach their own dreams instead of what the pope has commissioned.

- Let him who speaks against the truth concerning papal indulgences be anathema and accursed.

- But let him who guards against the lust and license of the indulgence preachers be blessed.

- Just as the pope justly thunders against those who by any means whatever contrive harm to the sale of indulgences.

- Much more does he intend to thunder against those who use indulgences as a pretext to contrive harm to holy love and truth.

- To consider papal indulgences so great that they could absolve a man even if he had done the impossible and had violated the mother of God is madness.

- We say on the contrary that papal indulgences cannot remove the very least of venial sins as far as guilt is concerned.

- To say that even St. Peter if he were now pope, could not grant greater graces is blasphemy against St. Peter and the pope.

- We say on the contrary that even the present pope, or any pope whatsoever, has greater graces at his disposal, that is, the gospel, spiritual powers, gifts of healing, etc., as it is written. (1 Co 12[:28])

- To say that the cross emblazoned with the papal coat of arms, and set up by the indulgence preachers is equal in worth to the cross of Christ is blasphemy.

- The bishops, curates, and theologians who permit such talk to be spread among the people will have to answer for this.

- This unbridled preaching of indulgences makes it difficult even for learned men to rescue the reverence which is due the pope from slander or from the shrewd questions of the laity.

- Such as: ``Why does not the pope empty purgatory for the sake of holy love and the dire need of the souls that are there if he redeems an infinite number of souls for the sake of miserable money with which to build a church?'' The former reason would be most just; the latter is most trivial.

- Again, ``Why are funeral and anniversary masses for the dead continued and why does he not return or permit the withdrawal of the endowments founded for them, since it is wrong to pray for the redeemed?''

- Again, ``What is this new piety of God and the pope that for a consideration of money they permit a man who is impious and their enemy to buy out of purgatory the pious soul of a friend of God and do not rather, beca use of the need of that pious and beloved soul, free it for pure love's sake?''

- Again, ``Why are the penitential canons, long since abrogated and dead in actual fact and through disuse, now satisfied by the granting of indulgences as though they were still alive and in force?''

- Again, ``Why does not the pope, whose wealth is today greater than the wealth of the richest Crassus, build this one basilica of St. Peter with his own money rather than with the money of poor believers?''

- Again, ``What does the pope remit or grant to those who by perfect contrition already have a right to full remission and blessings?''

- Again, ``What greater blessing could come to the church than if the pope were to bestow these remissions and blessings on every believer a hundred times a day, as he now does but once?''

- ``Since the pope seeks the salvation of souls rather than money by his indulgences, why does he suspend the indulgences and pardons previously granted when they have equal efficacy?''

- To repress these very sharp arguments of the laity by force alone, and not to resolve them by giving reasons, is to expose the church and the pope to the ridicule of their enemies and to make Christians unhappy.

- If, therefore, indulgences were preached according to the spirit and intention of the pope, all these doubts would be readily resolved. Indeed, they would not exist.

- Away, then, with all those prophets who say to the people of Christ, ``Peace, peace,'' and there is no peace! ( Jer 6:14 )

- Blessed be all those prophets who say to the people of Christ, ``Cross, cross,'' and there is no cross!

- Christians should be exhorted to be diligent in following Christ, their Head, through penalties, death and hell.

- And thus be confident of entering into heaven through many tribulations rather than through the false security of peace ( Acts 14:22 ).

-95 Theses courtesy of BibleStudyTools.com

4 Things the Parable of the Sower Teaches Us about Our Future

"The 16th Century Protestant Reformation was born out of Martin Luther’s 95 Theses. The reforms, particularly in regard to indulgences (payments taken in place of penance), were posted to a cathedral door in Wittenberg, Germany as a proclamation. The 95 Theses were written in Latin and wouldn’t have attracted the attention of the German-speaking people on the way in and out of the church the day he nailed them to the door. His intent was to reform the Catholic Church. “True revivals are provoked by the sovereign work of God through the stirring of His Holy Spirit in the hearts of people,” wrote R.C. Sproul, “They happen when the Holy Spirit comes into the valley of dry bones ( Ezek. 37 ) and exerts His power to bring new life, a revivification of the spiritual life of the people of God.” Though Luther did not intend to start a new denomination, he was accused of being a heretic and was excommunicated in 1520. ... Martin Luther’s personal struggle and revelation continue to remind us of the freedom and peace we have in Christ, despite our constant dysfunction and sin. Should we feel the burden of guilt and shame, we should remember Luther, run to God in Scripture, and embrace the Truth ourselves. Luther said, “Anyone who is to find Christ must first find the church, how could anyone know where Christ is and what faith is in him unless he knew where his believers are?” We are forgiven, once for all, though we all fall short. No penance on earth could erase the effects of our sins. Christ accomplished it once and for all on the cross." -Excerpted from " What Christians Need to Know about Reformation Day " by Meg Bucher

Related Article: What Christians Need to Know About Reformation Day

- Britannica.com , Martin Luther: The Indulgences Controversy , Diet of Worms , Later Years

- ChristianityToday.com , Martin Luther

- History.com , Martin Luther and the 95 Theses: Section 4 , Section 5

Photo credit: ©GettyImages/typo-graphics

Where Does the Bible Draw the Line Between Conflict and Emotional Abuse?

Where Is the Right Place to Share the Gospel?

What Is Pentecost and Where Did It Come From?

Morning Prayers to Start Your Day with God

The Best Birthday Prayers to Celebrate Friends and Family

Is Masturbation a Sin?

35 Prayers for Healing the Sick and Hurting

God’s presence is real, full of love, and completely transformational. It takes what was broken and brings healing. It takes what was lost and guides us to our rightful place in the Father.

Bible Baseball

Play now...

Saintly Millionaire

Bible Jeopardy

Bible Trivia By Category

Bible Trivia Challenge

About Church History

Read {2} by {3} and more articles about {1} and {0} on Christianity.com

The 95 Theses: A reader’s guide

![95 Theses Luther's 95 Theses. c. 1557 [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://blogs.lcms.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/95_Thesen_Erste_Seite_banner-1.jpg)

by Kevin Armbrust

October 2017 marks the 500th anniversary of the Lutheran Reformation. Yet it is not the anniversary of any great statement Luther made as a reformer or in front of any court. There was no fiery and resounding speech given or dramatic showdown with the pope. On October 31, 1517, Martin Luther posted the “Disputation on the Power and Efficacy of Indulgences” to the church door in a small city called Wittenberg, Germany. This rather mundane academic document contained 95 theses for debate. Luther was a professor of theology at the University of Wittenberg, and he was permitted to call for public theological debate to discuss ideas and interpretations as he desired.

Yet this debate was not merely academic for Luther. According to a letter he wrote to the Archbishop of Mainz explaining the posting of the 95 Theses, Luther also desired to debate the concerns in the Theses for the sake of conscience.

Luther’s short preface explains:

“Out of love and zeal for truth and the desire to bring it to light, the following theses will be publicly discussed at Wittenberg under the chairmanship of the reverend father Martin Luther, Master of Arts and Sacred Theology and regularly appointed Lecturer on these subjects at that place. He requests that those who cannot be present to debate orally with us will do so by letter.”

The original text of the 95 Theses was written in Latin, since that was the academic language of Luther’s day. Luther’s theses were quickly translated into German, published in pamphlet form and spread throughout Germany.

Though English translations are readily available , many have found the 95 Theses difficult to read and comprehend. The short primer that follows may assist to highlight some of the theses and concepts Luther wished to explore.

Repentance and forgiveness dominate the content of the Theses. Since the question for Luther was the effectiveness of indulgences, he drove the discussion to the consideration of repentance and forgiveness in Christ. The first three theses address this:

1. When our Lord and Master Jesus Christ said, “Repent” [MATT. 4:17], he willed the entire life of believers to be one of repentance.

2. This word cannot be understood as referring to the sacrament of penance, that is, confession and satisfaction, as administered by the clergy.

3. Yet it does not mean solely inner repentance; such inner repentance is worthless unless it produces various outward mortifications of the flesh.

The pope and the Church cannot cause true repentance in a Christian and cannot forgive the sins of one who is guilty before Christ. The pope can only forgive that which Christ forgives. True repentance and eternal forgiveness come from Christ alone.

Luther identifies indulgences as a doctrine invented by man, since there is no scriptural promise or command for indulgences. Although Luther stops short of entirely condemning indulgences in the Theses, he nonetheless argues that the sale of indulgences and the trust in indulgences for salvation condemns both those who teach such notions and those who trust in them.

27. They preach only human doctrines who say that as soon as the money clinks into the money chest, the soul flies out of purgatory.

28. Those who believe that they can be certain of their salvation because they have indulgence letters will be eternally damned, together with their teachers.

God’s grace comes not through indulgences but through Christ. All Christians receive the blessings of God apart from indulgence letters.

36. Any truly repentant Christian has a right to full remission of penalty and guilt, even without indulgence letters.

37. Any true Christian, whether living or dead, participates in all the blessings of Christ and the church; and this is granted him by God, even without indulgence letters.

If Christians are going to spend money on something other than supporting their families, they should take care of the poor instead of buying indulgences.

43. Christians are to be taught that he who gives to the poor or lends to the needy does a better deed than he who buys indulgences.

The second half of the 95 Theses concentrates on the preaching of the true Word of the Gospel. Luther states that the teaching of indulgences should be lessened so that there might be more time for the proclamation of the true Gospel.

62. The true treasure of the church is the most holy gospel of the glory and grace of God.

63. But this treasure is naturally most odious, for it makes the first to be last [MATT. 20:16].

The Gospel of Christ is the true power for salvation (ROM. 1:16), not indulgences or even the power of the papal office.

76. We say on the contrary that papal indulgences cannot remove the very least of venial sins as far as guilt is concerned.

77. To say that even St. Peter, if he were now pope, could not grant greater graces is blasphemy against St. Peter and the pope.

78. We say on the contrary that even the present pope, or any pope whatsoever, has greater graces at his disposal, that is, the gospel, spiritual powers, gifts of healing, etc., as it is written in I Cor. 12[:28].

Preaching a false hope is really no hope at all. As a matter of fact, a false hope destroys and kills because it moves people away from Christ, where true salvation is found. The Gospel is found in Christ alone, which includes a cross and tribulations both large and small.

92. Away then with all those prophets who say to the people of Christ, “Peace, peace,” and there is no peace! [JER. 6:14].

93. Blessed be all those prophets who say to the people of Christ, “Cross, cross,” and there is no cross!

94. Christians should be exhorted to be diligent in following Christ, their head, through penalties, death, and hell;

95. And thus be confident of entering into heaven through many tribulations rather than through the false security of peace [ACTS 14:22].

Throughout the 95 Theses, Luther seeks to balance the role of the Church with the truth of the Gospel. Even as he desired to support the pope and his role in the Church, the false teaching of indulgences and the pope’s unwillingness to freely forgive the sins of all repentant Christians compelled him to speak up against these abuses.

Luther’s pastoral desire for all to trust in Christ alone for salvation drove him to post the 95 Theses. This same faith and hope sparked the Reformation that followed.

Dr. Kevin Armbrust is manager of editorial services for LCMS Communications.

Related Posts

How did Luther become a Lutheran?

Laughing with Luther

Luther alone?

About the author.

Kevin Armbrust

11 thoughts on “the 95 theses: a reader’s guide”.

Thx. This article does clear up a number of difficulties in interpreting the drift & theme of the 95 thesis. The fact that he supports the pope’s office at this juncture is new to me.

Very useful as I prepare a Sunday School lesson. Thanks

As important as the 95 Theses were for the beginning of the Reformation, and since they are not specifically part of the Lutheran Confessions, are there any of the Theses that we Lutherans consider unimportant or would rather avoid, theologically speaking?

I wish Luther was here, maybe things would change in our country and bring more folks to Jesus .

“When our Lord and master Jesus Christ says, ‘Repent,’ he wills that the entire life of the Christian be one of repentance.”

This seemingly joyless statement is often quoted, less often explained, and easily misunderstood. Is Jesus calling for the main theme of Christian life to be, “I’m ashamed of my sin”?

The full sentence from Matthew 4:17 is, “Repent, for the kingdom of heaven is at hand,” spoken when Jesus was beginning His ministry. This layman might paraphrase those words as, “Change your mindset, for divine authority is coming among you.” Indeed, when a very important person is coming to visit, we depart from business as usual, adjust our priorities, focus on careful preparation, and behave as befits the status of the visitor.

The word “repent” is recorded in Greek as “metanoeite”, which I understand to be not about remorse — not primarily about feelings at all — but about changing one’s mind or purpose.

The Christian life has a variety of themes, of which repentance is one. But repentance is not an end in itself. It is pivoting and changing course to pursue a direction that better fulfills God’s purposes as He gives the grace. For Jesus also willed “that you bear much fruit” (John 15:8) and “that your joy may be full” (John 15:11).

Could you explain number 93? I need this one explained. Jackie

Agreed. 93 is confusing.

In contrast to the false security of indulgences referenced in 92, number 93 references the preaching of true repentance. With true contrition and repentance over our sins, we Christians humble ourselves to the truth that we have earned our place on the cross as punishment and condemnation. But then we find the eternal surprise and wellspring of joy that our cross has been taken away from us and made Christ’s own. In exchange He gives us forgiveness, life and salvation!

Thank you, James Athey.

I myself did not fully understand this thesis yesterday, when I searched the Internet for an explanation of it. I found that I was not the only person who was confused by it. I also found that Luther explained it in a letter that he wrote to an Augustinian prior in 1516. Here is his explanation:

You are seeking and craving for peace, but in the wrong order. For you are seeking it as the world giveth, not as Christ giveth. Know you not that God is “wonderful among His saints,” for this reason, that He establishes His peace in the midst of no peace, that is, of all temptations and afflictions. It is said “Thou shalt dwell in the midst of thine enemies.” The man who possesses peace is not the man whom no one disturbs—that is the peace of the world; he is the man whom all men and all things disturb, but who bears all patiently, and with joy. You are saying with Israel, “Peace, peace,” and there is no peace. Learn to say rather with Christ: “The Cross, the Cross,” and there is no Cross. For the Cross at once ceases to be the Cross as soon as you have joyfully exclaimed, in the language of the hymn,

Blessed Cross, above all other, One and only noble tree.

It is posted here: http://www.ccel.org/ccel/luther/first_prin.iii.i.html

Magnificent!

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

by Dr. Martin Luther, 1517

Disputation of Doctor Martin Luther on the Power and Efficacy of Indulgences by Dr. Martin Luther (1517)