Find anything you save across the site in your account

How the Right to Legal Abortion Changed the Arc of All Women’s Lives

By Katha Pollitt

I’ve never had an abortion. In this, I am like most American women. A frequently quoted statistic from a recent study by the Guttmacher Institute, which reports that one in four women will have an abortion before the age of forty-five, may strike you as high, but it means that a large majority of women never need to end a pregnancy. (Indeed, the abortion rate has been declining for decades, although it’s disputed how much of that decrease is due to better birth control, and wider use of it, and how much to restrictions that have made abortions much harder to get.) Now that the Supreme Court seems likely to overturn Roe v. Wade sometime in the next few years—Alabama has passed a near-total ban on abortion, and Ohio, Georgia, Kentucky, Mississippi, and Missouri have passed “heartbeat” bills that, in effect, ban abortion later than six weeks of pregnancy, and any of these laws, or similar ones, could prove the catalyst—I wonder if women who have never needed to undergo the procedure, and perhaps believe that they never will, realize the many ways that the legal right to abortion has undergirded their lives.

Legal abortion means that the law recognizes a woman as a person. It says that she belongs to herself. Most obviously, it means that a woman has a safe recourse if she becomes pregnant as a result of being raped. (Believe it or not, in some states, the law allows a rapist to sue for custody or visitation rights.) It means that doctors no longer need to deny treatment to pregnant women with certain serious conditions—cancer, heart disease, kidney disease—until after they’ve given birth, by which time their health may have deteriorated irretrievably. And it means that non-Catholic hospitals can treat a woman promptly if she is having a miscarriage. (If she goes to a Catholic hospital, she may have to wait until the embryo or fetus dies. In one hospital, in Ireland, such a delay led to the death of a woman named Savita Halappanavar, who contracted septicemia. Her case spurred a movement to repeal that country’s constitutional amendment banning abortion.)

The legalization of abortion, though, has had broader and more subtle effects than limiting damage in these grave but relatively uncommon scenarios. The revolutionary advances made in the social status of American women during the nineteen-seventies are generally attributed to the availability of oral contraception, which came on the market in 1960. But, according to a 2017 study by the economist Caitlin Knowles Myers, “The Power of Abortion Policy: Re-Examining the Effects of Young Women’s Access to Reproductive Control,” published in the Journal of Political Economy , the effects of the Pill were offset by the fact that more teens and women were having sex, and so birth-control failure affected more people. Complicating the conventional wisdom that oral contraception made sex risk-free for all, the Pill was also not easy for many women to get. Restrictive laws in some states barred it for unmarried women and for women under the age of twenty-one. The Roe decision, in 1973, afforded thousands upon thousands of teen-agers a chance to avoid early marriage and motherhood. Myers writes, “Policies governing access to the pill had little if any effect on the average probabilities of marrying and giving birth at a young age. In contrast, policy environments in which abortion was legal and readily accessible by young women are estimated to have caused a 34 percent reduction in first births, a 19 percent reduction in first marriages, and a 63 percent reduction in ‘shotgun marriages’ prior to age 19.”

Access to legal abortion, whether as a backup to birth control or not, meant that women, like men, could have a sexual life without risking their future. A woman could plan her life without having to consider that it could be derailed by a single sperm. She could dream bigger dreams. Under the old rules, inculcated from girlhood, if a woman got pregnant at a young age, she married her boyfriend; and, expecting early marriage and kids, she wouldn’t have invested too heavily in her education in any case, and she would have chosen work that she could drop in and out of as family demands required.

In 1970, the average age of first-time American mothers was younger than twenty-two. Today, more women postpone marriage until they are ready for it. (Early marriages are notoriously unstable, so, if you’re glad that the divorce rate is down, you can, in part, thank Roe.) Women can also postpone childbearing until they are prepared for it, which takes some serious doing in a country that lacks paid parental leave and affordable childcare, and where discrimination against pregnant women and mothers is still widespread. For all the hand-wringing about lower birth rates, most women— eighty-six per cent of them —still become mothers. They just do it later, and have fewer children.

Most women don’t enter fields that require years of graduate-school education, but all women have benefitted from having larger numbers of women in those fields. It was female lawyers, for example, who brought cases that opened up good blue-collar jobs to women. Without more women obtaining law degrees, would men still be shaping all our legislation? Without the large numbers of women who have entered the medical professions, would psychiatrists still be telling women that they suffered from penis envy and were masochistic by nature? Would women still routinely undergo unnecessary hysterectomies? Without increased numbers of women in academia, and without the new field of women’s studies, would children still be taught, as I was, that, a hundred years ago this month, Woodrow Wilson “gave” women the vote? There has been a revolution in every field, and the women in those fields have led it.

It is frequently pointed out that the states passing abortion restrictions and bans are states where women’s status remains particularly low. Take Alabama. According to one study , by almost every index—pay, workforce participation, percentage of single mothers living in poverty, mortality due to conditions such as heart disease and stroke—the state scores among the worst for women. Children don’t fare much better: according to U.S. News rankings , Alabama is the worst state for education. It also has one of the nation’s highest rates of infant mortality (only half the counties have even one ob-gyn), and it has refused to expand Medicaid, either through the Affordable Care Act or on its own. Only four women sit in Alabama’s thirty-five-member State Senate, and none of them voted for the ban. Maybe that’s why an amendment to the bill proposed by State Senator Linda Coleman-Madison was voted down. It would have provided prenatal care and medical care for a woman and child in cases where the new law prevents the woman from obtaining an abortion. Interestingly, the law allows in-vitro fertilization, a procedure that often results in the discarding of fertilized eggs. As Clyde Chambliss, the bill’s chief sponsor in the state senate, put it, “The egg in the lab doesn’t apply. It’s not in a woman. She’s not pregnant.” In other words, life only begins at conception if there’s a woman’s body to control.

Indifference to women and children isn’t an oversight. This is why calls for better sex education and wider access to birth control are non-starters, even though they have helped lower the rate of unwanted pregnancies, which is the cause of abortion. The point isn’t to prevent unwanted pregnancy. (States with strong anti-abortion laws have some of the highest rates of teen pregnancy in the country; Alabama is among them.) The point is to roll back modernity for women.

So, if women who have never had an abortion, and don’t expect to, think that the new restrictions and bans won’t affect them, they are wrong. The new laws will fall most heavily on poor women, disproportionately on women of color, who have the highest abortion rates and will be hard-pressed to travel to distant clinics.

But without legal, accessible abortion, the assumptions that have shaped all women’s lives in the past few decades—including that they, not a torn condom or a missed pill or a rapist, will decide what happens to their bodies and their futures—will change. Women and their daughters will have a harder time, and there will be plenty of people who will say that they were foolish to think that it could be otherwise.

By signing up, you agree to our User Agreement and Privacy Policy & Cookie Statement . This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

By Jia Tolentino

By Isaac Chotiner

By Margaret Talbot

Reflections on Abortion, Values, and the Family

Cite this chapter.

- Jean Bethke Elshtain 3

Part of the book series: The Hastings Center Series in Ethics ((HCSE))

231 Accesses

1 Citations

We live in a society marked by moral conflict. This conflict has deep historical roots and is reflected in our institutions, practices, laws, norms, and values. The abortion debate taps strongly held, powerfully experienced moral and political imperatives. These imperatives, in turn, are linked internally to a cluster of complex concerns and images evoking what sort of people we are anyway and what we aspire to be. The abortion debate won’t “go away, ” nor should it. For we are, after all, talking about matters of life and death, freedom and obligation, rights and duties: None of us can dispute that, and none of us can be nonplussed when we face the dilemmas that the abortion question poses.

My position has emerged complicatedly, first through familial and religious influence. As a child, I was taught the importance and integrity of life and the need to protect it. I remember my sisters and me doing our best to rescue fallen birds and nurse them back to health. We laboriously mixed an earthworm paste to feed to the birds through eye droppers. We mourned the deaths of baby chicks, ducks, and calves. Life was valuable, we were taught, not for instrumental reasons but in itself. The part of “me” that remains importantly the child that I was reasons thus: If a baby chick deserves respectful “tending to, ” does not a vulnerable, wholly dependent human life? Is that not what we are talking about if we talk ordinary language and refuse to retreat behind a screen of distancing, “medicalized” abstractions (“products of conception, ” “fetal matter, ” and so on)?

There are ways in which this direct and beautifully simple moral response has been both challenged and affirmed in my adult life. It has been challenged by my recognition of the desperate circumstances and situations in which many women find and have found themselves, for it is women who bear the most direct and inescapable brunt of human procreation. I do not call to mind here the desperate teenager alone but, say, the menopausal woman in her 50s who has every reason to believe that she is past reproductive age but finds, to her astonishment, that she is not. If one is a merciful and compassionate being, then one’s mercy and compassion must go out to these women and must not limit itself to the unborn. So I cannot accept an absolute prohibition on abortion. But I do not—and cannot—see that “right” as absolute. Here, I can draw on political and theoretical imperatives that are confirmatory of a respect-for-life position.

I am also influenced in my present position by a particular sort of social theory and philosophy—interpretive, reflective, and critical—together with my political concern that the white, middle-class or upper-middle-class majority has, all too often, presumed to legislate in behalf of, or undercover of, others, claiming that these others the poor or the minorities) require reforms that they might not be in a position to “see” for themselves. I believe that people must speak for themselves, in their own language, to their most urgent concerns. This belief introduces immediate ambiguity into the abortion debate—and deepens the ambiguity of my own position. For I am in fact part of a large majority that opposes both abortion on demand and an absolute restriction on abortion. This position suggests to me that my au-tobiographical history—though confirmed by a later commitment to a certain mode of social theorizing—is not mine alone but is shared by many Americans who are irrepressibly pragmatic yet stubbornly ethical and moral in their concerns. We should acknowledge, not quash, these moral sensibilities. The abortion debate is vital, for it means that we are still concerned about the sort of people we are and the kind of lives we are living.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Unable to display preview. Download preview PDF.

Philip Abbott, The Family on Trial ( University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1981 ), p. 138.

Google Scholar

Michael Tooley, “Abortion and Infanticide,” in Marshall Cohen, Thomas Nagel, and Thomas Scanlon, eds., The Rights and Wrongs of Abortion ( Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1974 ), pp. 54 – 55.

Elizabeth Rapaport and Paul Sagal, “One Step Forward, Two Steps Backward: Abortion and Ethical Theory,” in Marty Vetterling-Braggin, Frederick A. Elliston and Jane English, eds., Feminism and Philosophy ( Totowa, N.J.: Littlefield Adams, 1977 ), p. 410.

Quoted in Daniel Callahan, Abortion: Law, Choice and Morality ( New York: Macmillan, 1970 ), p. 462.

Cited in Lawrence Lader, Abortion (Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill, 1966), p. 156. (Italics added.)

Carol McMillen, Women, Reason and Nature ( Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1982 ), p. 127.

Alasdair Maclntyre, After Virtue ( South Bend, Ind.: Notre Dame University Press, 1981 ), p. 205.

Peter Brown, The Cult of the Saints: Its Rise and Function in Latin ( Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1981 ), p. 30.

Harry Boyte, The Backyard Revolution ( Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1980 ).

Stanley Hauerwas, “The Moral Value of the Family,” in A Community of Character (South Bend, Ind.: University of Notre Dame Press, 1981 ), p. 165.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Political Science, University of Massachusetts, Amherst, Massachusetts, 01003, USA

Jean Bethke Elshtain

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Mercy College, Dobbs Ferry, New York, USA

Sidney Callahan ( Associate Professor of Psychology ) ( Associate Professor of Psychology )

The Hastings Center Institute of Society, Ethics and the Life Sciences, Hastings-on-Hudson, New York, USA

Daniel Callahan ( Director of The Hastings Center ) ( Director of The Hastings Center )

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 1984 The Hastings Center

About this chapter

Elshtain, J.B. (1984). Reflections on Abortion, Values, and the Family. In: Callahan, S., Callahan, D. (eds) Abortion. The Hastings Center Series in Ethics. Springer, Boston, MA. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4613-2753-0_3

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4613-2753-0_3

Publisher Name : Springer, Boston, MA

Print ISBN : 978-1-4612-9703-1

Online ISBN : 978-1-4613-2753-0

eBook Packages : Springer Book Archive

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

There Are More Than Two Sides to the Abortion Debate

Readers share their perspectives.

Sign up for Conor’s newsletter here.

Earlier this week I curated some nuanced commentary on abortion and solicited your thoughts on the same subject. What follows includes perspectives from several different sides of the debate. I hope each one informs your thinking, even if only about how some other people think.

We begin with a personal reflection.

Cheryl was 16 when New York State passed a statute legalizing abortion and 19 when Roe v. Wade was decided in 1973. At the time she was opposed to the change, because “it just felt wrong.” Less than a year later, her mother got pregnant and announced she was getting an abortion.

She recalled:

My parents were still married to each other, and we were financially stable. Nonetheless, my mother’s announcement immediately made me a supporter of the legal right to abortion. My mother never loved me. My father was physically abusive and both parents were emotionally and psychologically abusive on a virtually daily basis. My home life was hellish. When my mother told me about the intended abortion, my first thought was, “Thank God that they won’t be given another life to destroy.” I don’t deny that there are reasons to oppose abortion. As a feminist and a lawyer, I can now articulate several reasons for my support of legal abortion: a woman’s right to privacy and autonomy and to the equal protection of the laws are near the top of the list. (I agree with Ruth Bader Ginsburg that equal protection is a better legal rationale for the right to abortion than privacy.) But my emotional reaction from 1971 still resonates with me. Most people who comment on the issue, on both sides, do not understand what it is to go through childhood unloved. It is horrific beyond my powers of description. To me, there is nothing more immoral than forcing that kind of life on any child. Anti-abortion activists often like to ask supporters of abortion rights: “Well, what if your mother had decided to abort you?” All I can say is that I have spent a great portion of my life wishing that my mother had done exactly that.

Steven had related thoughts:

I have respect for the idea that there should be some restrictions on abortion. But the most fundamental, and I believe flawed, unstated assumptions of the anti-choice are that A) they are acting on behalf of the fetus, and more importantly B) they know what the fetus would want. I would rather not have been born than to have been born to a mother who did not want me. All children should be wanted children—for the sake of all concerned. You can say that different fetuses would “want” different things—though it’s hard to say a clump of cells “wants” anything. How would we know? The argument lands, as it does generally, with the question of who should be making that decision. Who best speaks in the fetus’s interests? Who is better positioned morally or practically than the expectant mother?

Geoff self-describes as “pro-life” and guilty of some hypocrisy. He writes:

I’m pro-life because I have a hard time with the dehumanization that comes with the extremes of abortion on demand … Should it be okay to get an abortion when you find your child has Down syndrome? What of another abnormality? Or just that you didn’t want a girl? Any argument that these are legitimate reasons is disturbing. But so many of the pro-life just don’t seem to care about life unless it’s a fetus they can force a woman to carry. The hypocrisy is real. While you can argue that someone on death row made a choice that got them to that point, whereas a fetus had no say, I find it still hard to swallow that you can claim one life must be protected and the other must be taken. Life should be life. At least in the Catholic Church this is more consistent. I myself am guilty of a degree of hypocrisy. My wife and I used IVF to have our twins. There were other embryos created and not inserted. They were eventually destroyed. So did I support killing a life? Maybe? I didn’t want to donate them for someone else to give birth to—it felt wrong to think my twins may have brothers or sisters in the world they would never know about. Yet does that mean I was more willing to kill my embryos than to have them adopted? Sure seems like it. So I made a morality deal with myself and moved the goal post—the embryos were not yet in a womb and were so early in development that they couldn’t be considered fully human life. They were still potential life.

Colleen, a mother of three, describes why she ended her fourth pregnancy:

I was young when I first engaged this debate. Raised Catholic, anti-choice, and so committed to my position that I broke my parents’ hearts by giving birth during my junior year of college. At that time, my sense of my own rights in the matter was almost irrelevant. I was enslaved by my body. One husband and two babies later I heard a remarkable Jesuit theologian (I wish I could remember his name) speak on the matter and he, a Catholic priest, framed it most directly. We prioritize one life over another all the time. Most obviously, we justify the taking of life in war with all kinds of arguments that often turn out to be untrue. We also do so as we decide who merits access to health care or income support or other life-sustaining things. So the question of abortion then boils down to: Who gets to decide? Who gets to decide that the life of a human in gestation is actually more valuable than the life of the woman who serves as host—or vice versa? Who gets to decide when the load a woman is being asked to carry is more than she can bear? The state? Looking back over history, he argued that he certainly had more faith in the person most involved to make the best decision than in any formalized structure—church or state—created by men. Every form of birth control available failed me at one point or another, so when yet a 4th pregnancy threatened to interrupt the education I had finally been able to resume, I said “Enough.” And as I cried and struggled to come to that position, the question that haunted me was “Doesn’t MY life count?” And I decided it did.

Florence articulates what it would take to make her anti-abortion:

What people seem to miss is that depriving a woman of bodily autonomy is slavery. A person who does not control his/her own body is—what? A slave. At its simplest, this is the issue. I will be anti-abortion when men and women are equal in all facets of life—wages, chores, child-rearing responsibilities, registering for the draft, to name a few obvious ones. When there is birth control that is effective, where women do not bear most of the responsibility. We need to raise boys who are respectful to girls, who do not think that they are entitled to coerce a girl into having sex that she doesn’t really want or is unprepared for. We need for sex education to be provided in schools so young couples know what they are getting into when they have sex. Especially the repercussions of pregnancy. We need to raise girls who are confident and secure, who don’t believe they need a male to “complete” them. Who have enough agency to say “no” and to know why. We have to make abortion unnecessary … We have so far to go. If abortion is ruled illegal, or otherwise curtailed, we will never know if the solutions to women’s second-class status will work. We will be set back to the 50s or worse. I don’t want to go back. Women have fought from the beginning of time to own their bodies and their lives. To deprive us of all of the amazing strides forward will affect all future generations.

Similarly, Ben agrees that in our current environment, abortion is often the only way women can retain equal citizenship and participation in society, but also agrees with pro-lifers who critique the status quo, writing that he doesn’t want a world where a daughter’s equality depends on her right “to perform an act of violence on their potential descendents.” Here’s how he resolves his conflictedness:

Conservatives arguing for a more family-centered society, in which abortion is unnecessary to protect the equal rights of women, are like liberals who argue for defunding the police and relying on addiction, counselling, and other services, in that they argue for removing what offends them without clear, credible plans to replace the functions it serves. I sincerely hope we can move towards a world in which armed police are less necessary. But before we can remove the guardrails of the police, we need to make the rest of the changes so that the world works without them. Once liberal cities that have shown interest in defunding the police can prove that they can fund alternatives, and that those alternatives work, then I will throw my support behind defunding the police. Similarly, once conservative politicians demonstrate a credible commitment to an alternative vision of society in which women are supported, families are not taken for granted, and careers and short-term productivity are not the golden calves they are today, I will be willing to support further restrictions on abortion. But until I trust that they are interested in solving the underlying problem (not merely eliminating an aspect they find offensive), I will defend abortion, as terrible as it is, within reasonable legal limits.

Two readers objected to foregrounding gender equality. One emailed anonymously, writing in part:

A fetus either is or isn’t a person. The reason I’m pro-life is that I’ve never heard a coherent defense of the proposition that a fetus is not a person, and I’m not sure one can be made. I’ve read plenty of progressive commentary, and when it bothers to make an argument for abortion “rights” at all, it talks about “the importance of women’s healthcare” or something as if that were the issue.

Christopher expanded on that last argument:

Of the many competing ethical concerns, the one that trumps them all is the status of the fetus. It is the only organism that gets destroyed by the procedure. Whether that is permissible trumps all other concerns. Otherwise important ethical claims related to a woman’s bodily autonomy, less relevant social disparities caused by the differences in men’s and women’s reproductive functions, and even less relevant differences in partisan commitments to welfare that would make abortion less appealing––all of that is secondary. The relentless strategy by the pro-choice to sidestep this question and pretend that a woman’s right to bodily autonomy is the primary ethical concern is, to me, somewhere between shibboleth and mass delusion. We should spend more time, even if it’s unproductive, arguing about the status of the fetus, because that is the question, and we should spend less time indulging this assault-on-women’s-rights narrative pushed by the Left.

Jean is critical of the pro-life movement:

Long-acting reversible contraceptives, robust, science-based sex education for teens, and a stronger social safety net would all go a remarkable way toward decreasing the number of abortions sought. Yet all the emphasis seems to be on simply making abortion illegal. For many, overturning Roe v. Wade is not about reducing abortions so much as signalling that abortion is wrong. If so-called pro-lifers were as concerned about abortion as they seem to be, they would spend more time, effort, and money supporting efforts to reduce the need for abortion—not simply trying to make it illegal without addressing why women seek it out. Imagine, in other words, a world where women hardly needed to rely on abortion for their well-being and ability to thrive. Imagine a world where almost any woman who got pregnant had planned to do so, or was capable of caring for that child. What is the anti-abortion movement doing to promote that world?

Destiny has one relevant answer. She writes:

I run a pro-life feminist group and we often say that our goal is not to make abortion illegal, but rather unnecessary and unthinkable by supporting women and humanizing the unborn child so well.

Robert suggests a different focus:

Any well-reasoned discussion of abortion policy must include contraception because abortion is about unwanted children brought on by poorly reasoned choices about sex. Such choices will always be more emotional than rational. Leaving out contraception makes it an unrealistic, airy discussion of moral philosophy. In particular, we need to consider government-funded programs of long-acting reversible contraception which enable reasoned choices outside the emotional circumstances of having sexual intercourse.

Last but not least, if anyone can unite the pro-life and pro-choice movements, it’s Errol, whose thoughts would rankle majorities in both factions as well as a majority of Americans. He writes:

The decision to keep the child should not be left up solely to the woman. Yes, it is her body that the child grows in, however once that child is birthed it is now two people’s responsibility. That’s entirely unfair to the father when he desired the abortion but the mother couldn’t find it in her heart to do it. If a woman wants to abort and the man wants to keep it, she should abort. However I feel the same way if a man wants to abort. The next 18+ years of your life are on the line. I view that as a trade-off that warrants the male’s input. Abortion is a conversation that needs to be had by two people, because those two will be directly tied to the result for a majority of their life. No one else should be involved with that decision, but it should not be solely hers, either.

Thanks to all who contributed answers to this week’s question, whether or not they were among the ones published. What subjects would you like to see fellow readers address in future installments? Email [email protected].

By submitting an email, you’ve agreed to let us use it—in part or in full—in this newsletter and on our website. Published feedback includes a writer’s full name, city, and state, unless otherwise requested in your initial note.

Psychiatric and Personal Reflections on Abortion

What do we know about the psychiatric implications of having an abortion and not having access to such services? And what are the medical ethics involved?

fizkes/Adobestock

PSYCHIATRIC VIEWS ON THE DAILY NEWS

Of course, I could never have had an abortion . I am a man (he/him), so I have had to try to learn—both as a psychiatrist and as a man—what that might mean entail and, now, how to comment. After all, this is a psychiatry and society column, so how could it then ignore one of our major current societal issues that seems to have so many social psychiatric considerations?

My direct personal and professional involvement with abortion, limited as it is, goes back more than 50 years ago. While I was in medical school, my wife became pregnant, a pregnancy not planned. Abortion never entered my mind and was never brought up by my wife, nor anyone else. I then had the good fortune to be the primary caregiver of our darling daughter during the day of her first year of life while I was home doing my research project.

A couple of years later, I was in my second year of psychiatric residency training, which was a year before Roe v. Wade. I saw a number of women seeking an abortion, which could be obtained if it was psychiatrically risky to continue the pregnancy, or something like that, as I cannot recall the detailed criteria. With supervision, I approved them all, although I never knew the outcome of any of these decisions. I felt helpful and believed that this was the right decision all around, but with some guilt about the potential child.

I have tried to keep up with the recent media discussions about our abortion laws and the possibility of change in some states. However, by far the most informative and moving article that I read was by Merritt Tierce in yesterday’s Sunday New York Times Magazine , “The Abortion I Didn’t Have”. In the article, Tierce discusses the reasons that she, 19 years old at the time, did not seek an abortion with her first unplanned child, as well as the ensuing repercussions for her life and that of her son. She then had a second child out of more overt choice, and then 2 abortions. Clearly, this was not a simple process for her, nor probably other women, based on her discussions of what she considered the complicated, ambivalent, and often contradictory benefits and drawbacks of her first decision.

That article led me to double-check what our professional American Psychiatric Association organizations have said about abortion. The last action that I found for the APA was in May 2018 and was titled a “ Position Statement on Abortion .” It clarified that careful research has indicated that having an abortion is generally not associated with any increase in psychiatric symptoms in the woman. However, that is a generality and there can be a range of abortion aftermath responses. The statement then goes on to its primary position that “abortion is a medical procedure, and a decision about an abortion should be between a woman and her physician.”

The longer American Psychological Association commentary on “Abortion and Mental Health” was from around the same time, June of 2018. Theirs also reviews the science, including on the child’s future, and that “Unwanted pregnancy has been associated with deficits to the subsequent child’s cognitive, emotional and social processes.”

Both of these research findings regarding the woman and the child helped assuage my earlier residency guilt. The American Psychological Association policy comes out similar to that of psychiatry, and includes their subsequent and ongoing advocacy and legal action on abortion.

Out of many controversial Supreme Court decisions over the past 50 years, this one seems distinct in its viability. Why might that be? It is literally a life and death issue. However, any changes in Roe v. Wade can be a precedent to reconsider other decisions.

For some, this abortion decision is simply a yes or no. However, for me as a psychiatrist and as a man, it is not. All of these experiences and considerations leaves me with 8 tentative—indeed very tentative—conclusions as to what I currently think may be the major mental health implications for mother and child:

- Do what is practically and psychological possible to not develop an unwanted pregnancy.

- There are invariably complex psychological reasons to have or not have an abortion, and at times of unresolved ambivalence, therapeutic discussion may be indicated.

- It is virtually impossible to compare the outcome of the abortion choice with the path not taken, so it is important to try to come to peace with the final personal decision.

- Having inadequate and difficult-to-access abortion services seems to be a sign of misogyny, and poor women will be the most affected.

- If our abortion laws are changed, they should be done very gradually and in a manner that allows some comparison with outcomes related to the prior law.

- As the Preamble and Section 7 of The Principles of Medical Ethics states about our responsibility to society, abortion is an ethical matter for us.

- Given the cracks occurring in Roe v. Wade, it seems that our professional societies’ views on abortion need updating.

- Our professional societies and ourselves need to educate the public about the mental health implications of abortion, especially in regards to children of unwanted pregnancies.

On Friday, the Supreme Court is supposed to meet to hold a preliminary vote on their decision. What will they—and we—say?

Dr Moffic is an award-winning psychiatrist who has specialized in the cultural and ethical aspects of psychiatry. A prolific writer and speaker, he received the one-time designation of Hero of Public Psychiatry from the Assembly of the American Psychiatric Association in 2002. He is an advocate for mental health issues relate to climate instability, burnout, Islamophobia, and anti-Semitism for a better world. He serves on the Editorial Board of Psychiatric Times TM .

What do you think? Share your thoughts, comments, and feedback with [email protected].

The Psychoexemplary of Compassionating as Mexico Elects Its First Woman and Jewish President

A Forensic Psychiatrist Takes the Stand

A Voice Lab Gives Voice to the Psychoexemplary of Support

What Makes Men’s Depression Different?

Peacemaking as a Primary Psychoexemplary

The Week in Review: May 20-24

2 Commerce Drive Cranbury, NJ 08512

609-716-7777

Numbers, Facts and Trends Shaping Your World

Read our research on:

Full Topic List

Regions & Countries

- Publications

- Our Methods

- Short Reads

- Tools & Resources

Read Our Research On:

Key facts about the abortion debate in America

The U.S. Supreme Court’s June 2022 ruling to overturn Roe v. Wade – the decision that had guaranteed a constitutional right to an abortion for nearly 50 years – has shifted the legal battle over abortion to the states, with some prohibiting the procedure and others moving to safeguard it.

As the nation’s post-Roe chapter begins, here are key facts about Americans’ views on abortion, based on two Pew Research Center polls: one conducted from June 25-July 4 , just after this year’s high court ruling, and one conducted in March , before an earlier leaked draft of the opinion became public.

This analysis primarily draws from two Pew Research Center surveys, one surveying 10,441 U.S. adults conducted March 7-13, 2022, and another surveying 6,174 U.S. adults conducted June 27-July 4, 2022. Here are the questions used for the March survey , along with responses, and the questions used for the survey from June and July , along with responses.

Everyone who took part in these surveys is a member of the Center’s American Trends Panel (ATP), an online survey panel that is recruited through national, random sampling of residential addresses. This way nearly all U.S. adults have a chance of selection. The survey is weighted to be representative of the U.S. adult population by gender, race, ethnicity, partisan affiliation, education and other categories. Read more about the ATP’s methodology .

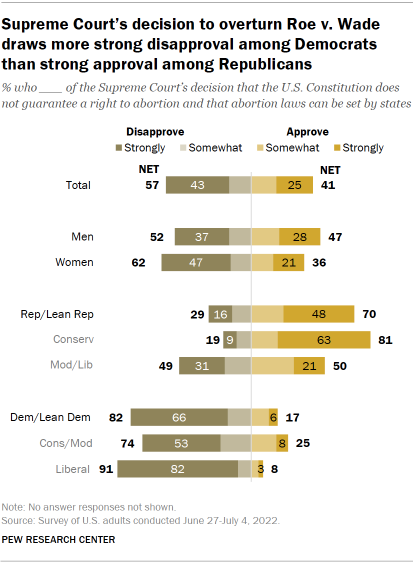

A majority of the U.S. public disapproves of the Supreme Court’s decision to overturn Roe. About six-in-ten adults (57%) disapprove of the court’s decision that the U.S. Constitution does not guarantee a right to abortion and that abortion laws can be set by states, including 43% who strongly disapprove, according to the summer survey. About four-in-ten (41%) approve, including 25% who strongly approve.

About eight-in-ten Democrats and Democratic-leaning independents (82%) disapprove of the court’s decision, including nearly two-thirds (66%) who strongly disapprove. Most Republicans and GOP leaners (70%) approve , including 48% who strongly approve.

Most women (62%) disapprove of the decision to end the federal right to an abortion. More than twice as many women strongly disapprove of the court’s decision (47%) as strongly approve of it (21%). Opinion among men is more divided: 52% disapprove (37% strongly), while 47% approve (28% strongly).

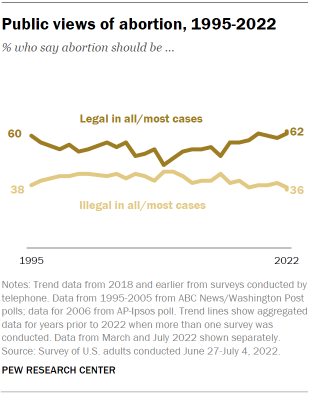

About six-in-ten Americans (62%) say abortion should be legal in all or most cases, according to the summer survey – little changed since the March survey conducted just before the ruling. That includes 29% of Americans who say it should be legal in all cases and 33% who say it should be legal in most cases. About a third of U.S. adults (36%) say abortion should be illegal in all (8%) or most (28%) cases.

Generally, Americans’ views of whether abortion should be legal remained relatively unchanged in the past few years , though support fluctuated somewhat in previous decades.

Relatively few Americans take an absolutist view on the legality of abortion – either supporting or opposing it at all times, regardless of circumstances. The March survey found that support or opposition to abortion varies substantially depending on such circumstances as when an abortion takes place during a pregnancy, whether the pregnancy is life-threatening or whether a baby would have severe health problems.

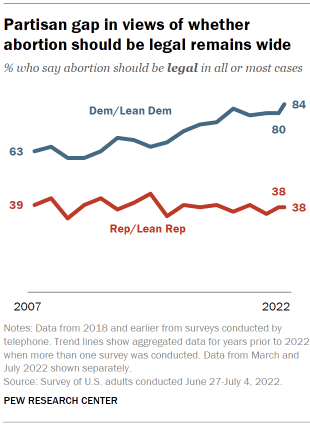

While Republicans’ and Democrats’ views on the legality of abortion have long differed, the 46 percentage point partisan gap today is considerably larger than it was in the recent past, according to the survey conducted after the court’s ruling. The wider gap has been largely driven by Democrats: Today, 84% of Democrats say abortion should be legal in all or most cases, up from 72% in 2016 and 63% in 2007. Republicans’ views have shown far less change over time: Currently, 38% of Republicans say abortion should be legal in all or most cases, nearly identical to the 39% who said this in 2007.

However, the partisan divisions over whether abortion should generally be legal tell only part of the story. According to the March survey, sizable shares of Democrats favor restrictions on abortion under certain circumstances, while majorities of Republicans favor abortion being legal in some situations , such as in cases of rape or when the pregnancy is life-threatening.

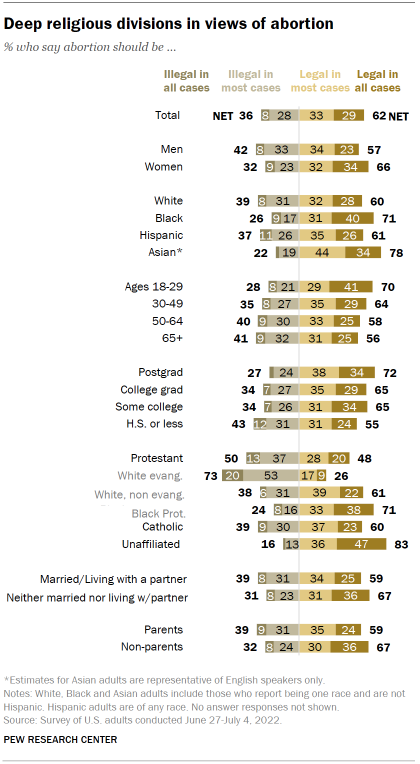

There are wide religious divides in views of whether abortion should be legal , the summer survey found. An overwhelming share of religiously unaffiliated adults (83%) say abortion should be legal in all or most cases, as do six-in-ten Catholics. Protestants are divided in their views: 48% say it should be legal in all or most cases, while 50% say it should be illegal in all or most cases. Majorities of Black Protestants (71%) and White non-evangelical Protestants (61%) take the position that abortion should be legal in all or most cases, while about three-quarters of White evangelicals (73%) say it should be illegal in all (20%) or most cases (53%).

In the March survey, 72% of White evangelicals said that the statement “human life begins at conception, so a fetus is a person with rights” reflected their views extremely or very well . That’s much greater than the share of White non-evangelical Protestants (32%), Black Protestants (38%) and Catholics (44%) who said the same. Overall, 38% of Americans said that statement matched their views extremely or very well.

Catholics, meanwhile, are divided along religious and political lines in their attitudes about abortion, according to the same survey. Catholics who attend Mass regularly are among the country’s strongest opponents of abortion being legal, and they are also more likely than those who attend less frequently to believe that life begins at conception and that a fetus has rights. Catholic Republicans, meanwhile, are far more conservative on a range of abortion questions than are Catholic Democrats.

Women (66%) are more likely than men (57%) to say abortion should be legal in most or all cases, according to the survey conducted after the court’s ruling.

More than half of U.S. adults – including 60% of women and 51% of men – said in March that women should have a greater say than men in setting abortion policy . Just 3% of U.S. adults said men should have more influence over abortion policy than women, with the remainder (39%) saying women and men should have equal say.

The March survey also found that by some measures, women report being closer to the abortion issue than men . For example, women were more likely than men to say they had given “a lot” of thought to issues around abortion prior to taking the survey (40% vs. 30%). They were also considerably more likely than men to say they personally knew someone (such as a close friend, family member or themselves) who had had an abortion (66% vs. 51%) – a gender gap that was evident across age groups, political parties and religious groups.

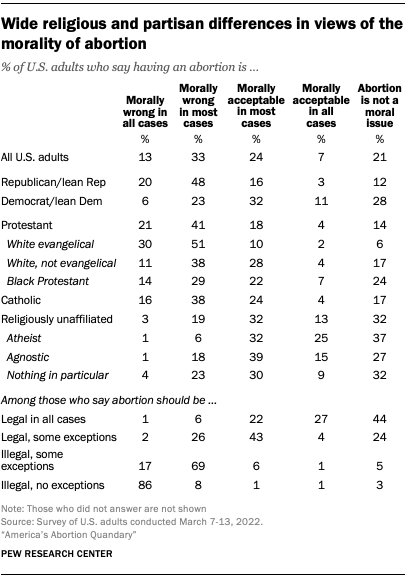

Relatively few Americans view the morality of abortion in stark terms , the March survey found. Overall, just 7% of all U.S. adults say having an abortion is morally acceptable in all cases, and 13% say it is morally wrong in all cases. A third say that having an abortion is morally wrong in most cases, while about a quarter (24%) say it is morally acceptable in most cases. An additional 21% do not consider having an abortion a moral issue.

Among Republicans, most (68%) say that having an abortion is morally wrong either in most (48%) or all cases (20%). Only about three-in-ten Democrats (29%) hold a similar view. Instead, about four-in-ten Democrats say having an abortion is morally acceptable in most (32%) or all (11%) cases, while an additional 28% say it is not a moral issue.

White evangelical Protestants overwhelmingly say having an abortion is morally wrong in most (51%) or all cases (30%). A slim majority of Catholics (53%) also view having an abortion as morally wrong, but many also say it is morally acceptable in most (24%) or all cases (4%), or that it is not a moral issue (17%). Among religiously unaffiliated Americans, about three-quarters see having an abortion as morally acceptable (45%) or not a moral issue (32%).

- Religion & Abortion

Carrie Blazina is a former digital producer at Pew Research Center .

Support for legal abortion is widespread in many places, especially in Europe

Public opinion on abortion, americans overwhelmingly say access to ivf is a good thing, broad public support for legal abortion persists 2 years after dobbs, what the data says about abortion in the u.s., most popular.

1615 L St. NW, Suite 800 Washington, DC 20036 USA (+1) 202-419-4300 | Main (+1) 202-857-8562 | Fax (+1) 202-419-4372 | Media Inquiries

Research Topics

- Email Newsletters

ABOUT PEW RESEARCH CENTER Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping the world. It conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, media content analysis and other empirical social science research. Pew Research Center does not take policy positions. It is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts .

© 2024 Pew Research Center

Click through the PLOS taxonomy to find articles in your field.

For more information about PLOS Subject Areas, click here .

Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

Abortion attitudes, religious and moral beliefs, and pastoral care among Protestant religious leaders in Georgia

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

Affiliations Department of Population, Family and Reproductive Health, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, Maryland, United States of America, The Center for Reproductive Health Research in the Southeast, Rollins School of Public Health, Emory University, Atlanta, Georgia, United States of America

Roles Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Methodology, Supervision, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Hubert Department of Global Health, Rollins School of Public Health, Emory University, Atlanta, Georgia, United States of America

Roles Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – review & editing

Affiliations The Center for Reproductive Health Research in the Southeast, Rollins School of Public Health, Emory University, Atlanta, Georgia, United States of America, Department of Behavioral, Social and Health Education Sciences, Rollins School of Public Health, Emory University, Atlanta, Georgia, United States of America

Roles Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Methodology, Project administration, Writing – review & editing

Affiliations The Center for Reproductive Health Research in the Southeast, Rollins School of Public Health, Emory University, Atlanta, Georgia, United States of America, Department of Epidemiology, Rollins School of Public Health, Emory University, Atlanta, Georgia, United States of America

Affiliations The Center for Reproductive Health Research in the Southeast, Rollins School of Public Health, Emory University, Atlanta, Georgia, United States of America, Hubert Department of Global Health, Rollins School of Public Health, Emory University, Atlanta, Georgia, United States of America, Graduate Division of Religion, Laney Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, Emory University, Atlanta, Georgia, United States of America

Roles Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Resources, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Reproductive Justice Activist and Movement Chaplain, Atlanta, Georgia, United States of America

Affiliation All Souls Church Unitarian, Washington, D.C., United States of America

Roles Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Writing – review & editing

Affiliations The Center for Reproductive Health Research in the Southeast, Rollins School of Public Health, Emory University, Atlanta, Georgia, United States of America, Department of Behavioral, Social and Health Education Sciences, Rollins School of Public Health, Emory University, Atlanta, Georgia, United States of America, Heilbrunn Department of Population & Family Health, Mailman School of Public Health, Columbia University, New York, NY, United States of America

Roles Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

* E-mail: [email protected]

- Jessica L. Dozier,

- Monique Hennink,

- Elizabeth Mosley,

- Subasri Narasimhan,

- Johanna Pringle,

- Lasha Clarke,

- John Blevins,

- Latishia James-Portis,

- Rob Keithan,

- Published: July 17, 2020

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0235971

- Reader Comments

The purpose of this study is to explore Protestant religious leaders’ attitudes towards abortion and their strategies for pastoral care in Georgia, USA. Religious leaders may play an important role in providing sexual and reproductive health pastoral care given a long history of supporting healing and health promotion.

We conducted 20 in-depth interviews with Mainline and Black Protestant religious leaders on their attitudes toward abortion and how they provide pastoral care for abortion. The study was conducted in a county with relatively higher rates of abortion, lower access to sexual and reproductive health services, higher religiosity, and greater denominational diversity compared to other counties in the state. Interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed verbatim, and analyzed by thematic analysis.

Religious leaders’ attitudes towards abortion fell on a spectrum from “pro-life” to “pro-choice”. However, most participants expressed attitudes in the middle of this spectrum and described more nuanced, complex, and sometimes contradictory views. Differences in abortion attitudes stemmed from varying beliefs on when life begins and circumstances in which abortion may be morally acceptable. Religious leaders described their pastoral care on abortion as “journeying with” congregants by advising them to make well-informed decisions irrespective of the religious leader’s own attitudes. However, many religious leaders described a lack of preparation and training to have these conversations. Leaders emphasized not condoning abortion, yet being willing to emotionally support women because spiritual leaders are compelled to love and provide pastoral care. Paradoxically, all leaders emphasized the importance of empathy and compassion for people who have unplanned pregnancies, yet only leaders whose attitudes were “pro-choice” or in the middle of the spectrum expressed an obligation to confront stigmatizing attitudes and behaviors towards people who experience abortion. Additionally, many leaders offer misinformation about abortion when offering pastoral care.

These findings contribute to limited empirical evidence on pastoral care for abortion. We found religious leaders hold diverse attitudes and beliefs about abortion, rooted in Christian scripture and doctrine that inform advice and recommendations to congregants. While religious leaders may have formal training on pastoral care in general or theological education on the ethical issues related to abortion, they struggle to integrate their knowledge and training across these two areas. Still, leaders could be potentially important resources for empathy, compassion, and affirmation of agency in abortion decision-making, particularly in the Southern United States.

Citation: Dozier JL, Hennink M, Mosley E, Narasimhan S, Pringle J, Clarke L, et al. (2020) Abortion attitudes, religious and moral beliefs, and pastoral care among Protestant religious leaders in Georgia. PLoS ONE 15(7): e0235971. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0235971

Editor: Jonathan Jong, Coventry University, UNITED KINGDOM

Received: January 7, 2020; Accepted: June 26, 2020; Published: July 17, 2020

Copyright: © 2020 Dozier et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Data Availability: Our data are comprised of transcripts from qualitative interviews with Protestant religious leaders in Georgia surrounding abortion attitudes and pastoral care. These data cannot be shared publicly, as the qualitative data presents potential risks and harms beyond those agreed to by study participants in the consent process and approved by the Emory University Institutional Review Board. However, data access requests may be sent to [email protected] . In order to facilitate research transparency, we provide the study interview guide and codebook as Supporting Information files.

Funding: This study was funded by the Center for Reproductive Health Research in the SouthEast ( https://rise.emory.edu ) with support from an anonymous foundation (to KSH). The funder had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Competing interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Introduction

Abortion is a common experience for U.S. women of reproductive age—approximately 1 in 4 will have an abortion by age 45 [ 1 ]. In the United States, 13.5 abortions per 1,000 women of reproductive age were reported in 2017. While national and regional abortion rates have been declining, rates in the state of Georgia have increased in recent years [ 2 ]. The rate of abortion in Georgia was 16.9 abortions/1,000 women aged 15–44 in 2017 [ 2 ].

Despite abortion being common, most people in Georgia face systemic and socio-cultural barriers limiting access to abortion services. Attitudes that condemn abortion emerge in policy, systems, and at the community-level [ 3 ]. Manifestations of abortion stigma [ 3 – 6 ] may influence people’s ability to exercise reproductive autonomy [ 7 , 8 ]. Researchers suggest “abortion stigma confounds a woman’s decision to terminate a pregnancy due to worries about judgment, isolation, self-judgment, and community condemnation” [ 9 ]. In 2014, only 4% of counties had clinics that provided abortion, leaving 58% of women in Georgia without a clinic in their county. Restrictive state legislation threatens to impose additional barriers to abortion access. For example, in 2019, Georgia legislators introduced HB 481, a bill that sought to outlaw abortion once a fetal heartbeat is detected [ 10 ]. This bill aimed to restrict abortion as early as 6 weeks gestation, before many people know they are pregnant [ 11 ]—one of the strictest abortion bans in the nation [ 12 ]. A federal judge granted an injunction in early October 2019, which blocked the law while it is argued in court [ 13 ].

More restrictive policies leave the most vulnerable, economically disadvantaged, and socially isolated people with few choices but to carry pregnancies they feel they are unable to support to term; however, those who carry pregnancies also face systemic barriers including limited access to perinatal care. Georgia has one of the highest maternal mortality rates in the United States [ 14 ], yet access to obstetric services is limited by a declining obstetrician/gynecologist workforce, especially in rural areas [ 15 ]. Moreover, half of all counties in Georgia are without a single obstetrician/gynecologist or hospital where women can give birth or access basic services [ 16 ].

Religious leaders are pivotal in their faith communities [ 17 ] and may be influential in shaping attitudes towards sexual and reproductive health (SRH), norms, and behaviors at the individual, family and community levels [ 8 , 17 , 18 ]; however, religious doctrine and beliefs may come in direct conflict with public health recommendations regarding abortion and contraception [ 19 ]. Previous research [ 4 ] has found links between religiosity and experiences of abortion stigma and it is “often the religious voices that oppose sexual and reproductive rights that have been the most visible in the media and most influential in policy debates” [ 17 ]. In a landmark 2014 case, Burwell v Hobby Lobby Stores , Inc ., the Supreme Court ruled that the Religious Freedom Restoration Act (RFRA) of 1993 allows a for-profit company to deny its employees coverage for contraception through the employer-based health plan because of the religious objections of the Hobby Lobby owners [ 20 ]. Conversely, Mainline Protestant religious leaders have historically played a role in shaping SRH policy, specifically with advocacy efforts for increased access to contraception and abortion during the twentieth century [ 17 ].

While many religions are perceived to condemn abortion [ 21 ], religiously affiliated women do have abortions—the majority (62%) of women who obtained an abortion in 2008 and 2014 claimed a religious affiliation [ 22 ]. Of these women, 17% identified an affiliation with a Mainline Protestant denomination [ 22 ]. This percentage is higher than that found in the American population as a whole; in 2010, Mainline Protestants only represented 7.2% of the United States population [ 23 ].

Religious leaders may play an important role in providing SRH-related pastoral care and resources given that “religions have a venerable tradition supporting healing, health care, disease prevention, and health promotion [and a] commitment to the most marginalized, the most vulnerable, and the most likely to be excluded” [ 17 ]. Still, little is known about the pastoral care practices of religious leaders as they relate to abortion, especially in the southern states of the United States and there are few resources in pastoral theology that address abortion. In fact, a review of publications from Mainline Protestant publishing houses over the last two decades identified only two books published on pastoral care and abortion [ 24 , 25 ]. A keyword review of the American Theological Library Association (ATLA) database identified no peer-reviewed articles exploring abortion published in pastoral theology journals over the last twenty years. Given their potential reach and influence, there is a need to understand the religious and moral views that shape religious leaders’ attitudes toward abortion, and their pastoral care practices, particularly in Georgia, a state with high religious influence [ 26 ] and gaps in reproductive healthcare [ 15 , 16 , 27 ]. This study aims to explore Mainline and Black Protestant religious leaders’ attitudes towards abortion and how they provide pastoral care regarding abortion.

Materials and methods

Participant recruitment.

Participants were recruited from two religious traditions based on categorization developed by Steensland and colleagues [ 28 ]. Mainline Protestantism is a branch of Protestantism that consists of denominations that are generally considered theologically liberal and moderate (e.g. Presbyterian Church (USA), the United Methodist Church, Episcopal Church, and the United Church of Christ). Black Protestantism (also known as “the Black Church”) is theologically and structurally similar to white evangelical denominations, “but also emphasizes social justice and community activism” [ 29 ]. According to the Association of Religious Data Archives, Black Protestant denominations are generally economically liberal and socially conservative [ 29 ]. The tradition consists of seven major denominations, such as the African Methodist Episcopal Church, the Church of God in Christ, and the Progressive National Baptist Church [ 29 ].

For this study, 20 semi-structured, in-depth interviews were conducted with religious leaders serving in Mainline and Black Protestant churches in a county with urban and rural areas outside of Atlanta, Georgia. The study site was selected due to its higher abortion rates, lower SRH service access, a higher religious adherence, greater denominational diversity, and an abundance of Mainline Protestant and Black Protestant churches as compared to other similar counties in Georgia. Religious leaders were eligible to participate if they were currently serving in a Mainline Protestant or Black Protestant church as a clergy member or lay leader (i.e. a non-ordained member of a Christian church [ 29 ]) for at least 6 months prior to the interview, were over 18 years old, and spoke English.

Purposive sampling was used to recruit a sample of religious leaders diverse in denomination and sociodemographic characteristics. Churches were identified using a publicly available list of churches by county published by The Association of Religious Data Archives. Names and contact information for the primary religious leader of these churches were obtained from church websites and social media. Lay leaders were recruited by social media messages and snowball sampling because their contact information was often not publicly available on church websites. Religious leaders were contacted up to five times by email, phone, and social media message using standard Institutional Review Board (IRB)-approved scripts. Leaders were also approached in person and recruited at centers of commerce (e.g. local strip malls) in the county using a standard recruitment script, screened for eligibility, and interviewed at a later date in a private location.

Participant characteristics

Socio-demographic characteristics of study participants are presented in Table 1 . The majority of participants recruited were men (80%) serving in senior pastoral roles (60%). Other religious titles reported included: pastor, associate pastor, first lady, minister, regional minister, youth minister, and lay leader. The average length of time served in the participant’s current role was 8.3 years (6 months to 40+ years). Age ranged from 28 to 72 years, with a mean age of 48. Sixty-five percent of participants had a graduate degree—most commonly a Masters of Divinity. Church membership size ranged from less than 50 to over 1000 people.

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0235971.t001

Data collection

In-depth interviews were conducted between October 2018 and September 2019 using a semi-structured interview guide (See S1 Appendix ). The interview guide included questions on participants’ views about unplanned pregnancy and abortion, pastoral care on these topics, and suggestions for discussions and programming around unintended pregnancy and abortion in faith settings. Some of the questions included, “ What are your personal views on abortion ? ” and “ What advice would you give someone in your congregation considering abortion ?” Researchers probed for barriers and facilitators to providing pastoral care on these topics and specific resources and scripture religious leaders would rely on during these conversations. The interview guide was pilot-tested in four interviews with clergy members serving in Mainline and Black Protestant churches in metro-Atlanta and then refined for clarity. Iterative changes were made to the interview guide and to participant recruitment throughout the data collection period to explore new topics raised and to include participants with differing perspectives, as is usual in qualitative data collection.

Participants were consented verbally. They were read an IRB-approved consent script, invited to ask follow-up questions, and asked if they agreed to take part in the study. A short demographic survey was administered after the informed consent process. Interviews were conducted in private offices at the participant’s church, at Emory University, or another location (e.g. a private room in a coffee shop) and digitally audio-recorded. Interviews lasted between 45 and 90 minutes, and participants received a $50 gift card. The study was approved by the IRB at Emory University (IRB 00106069).

Five researchers collected the data. They were trained on qualitative research methods, the study protocol, and research ethics. All researchers were cisgender women of reproductive age: four multi-ethnic women and one white woman. They had varying religious backgrounds and level of experience within Christian churches. Throughout data collection, the researchers practiced reflexivity by journaling their own thoughts and impressions about the research topic or participant’s experiences. They also noted potential biases that may have influenced data collected. Researchers shared these reflexive notes in team debriefing sessions and discussed ways to minimize researcher influence on the data collection process. Debriefing sessions included discussions on how researcher’s social identities and preconceptions about the study issues may have influenced the data as well as strategies to minimize these influences. For example, reflexivity revealed emerging data on race and religion, whereby the team felt that matching the race of researchers and participants may provide a more enabling environment for a deeper, more nuanced data on participants views on race and abortion.

Data analysis

Thematic analysis was used to describe Mainline and Black Protestant religious leaders’ attitudes towards abortion and how they provide pastoral care regarding abortion. Interviews were transcribed verbatim by a professional transcription company and de-identified by the research team. Data were managed and organized using Dedoose version 8.0.35, a software package for qualitative data analysis [ 30 ]. Data collection, coding, and analysis occurred simultaneously to assess meaning saturation, or a “richly textured understanding” of abortion attitudes and pastoral care practices [ 31 ]. Saturation was reached at 20 interviews when a diversity of views and denominations was achieved and no new themes were observed.

Data were read in detail and memoed in order to develop a codebook (See S2 Appendix ). Codes were developed through inductive (emerging from the data) and deductive (pre-determined topics from the interview guide) strategies. An inter-coder agreement exercise was conducted prior to coding all data to ensure consistency in the coding process. Weekly team meetings were held to refine code definitions, resolve discrepancies in coding, and discuss reflexivity in data interpretation during the coding process. For example, researchers discussed how our underlying epistemologies, public health training, and differing views on scripture and doctrine, might influence interpretation of data during analysis.

Researchers explored data by codes (e.g., abortion , attitudes & beliefs , and pastoral care) , conducted structured comparisons of codes by sub-groups of participants (e.g., by sociopolitical attitudes, denomination, and gender). Patterns in the data were examined and sub-themes within codes were identified. Illustrative quotes were then selected for each sub-theme.

Results were organized around 1) abortion attitudes; 2) moral and religious beliefs; and 3) pastoral care.

Abortion attitudes

When asked about their views on abortion, most participants noted affiliation with sociopolitical attitudes regarding abortion (e.g. “pro-life” and “pro-choice”). Differences among attitudes were observed in the participant’s understanding of when life begins, an affirmation of a women’s autonomy, and expression of the circumstances in which abortion may be morally acceptable. All participants identified at least one circumstance in which abortion may be the best decision for a pregnant person. Participants who identified their views as “pro-life” offered fewer moral exceptions for abortion, explaining that the circumstances of most unplanned pregnancies are surmountable, and therefore do not need to be resolved by abortion.

Nonetheless, the majority of participants expressed statements not readily fitting into a dichotomy of attitudes, but rather intermediate between “pro-life” and “pro-choice” in the so-called “gray area.” Attitudes in the “gray area” were nuanced, complex, and fell along a spectrum between “pro-life” and “pro-choice” attitudes. “Gray Area” attitudes were distinguished by an understanding that people have to make decisions on their own, yet “all life is sacred” and should be protected. In addition, participants with these “gray area” attitudes expressed tentativeness about taking a strong stance of “pro-life” or “pro-choice,” noting tensions between beliefs held in both categories and a desire to hold onto religious beliefs while acknowledging legal right to abortion. Illustrative quotes of the range of common attitudes are presented in Table 2 .

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0235971.t002

“Pro-life”.

There was no pattern among participants with “pro-life” attitudes by gender, tradition, denomination, or leadership role; participants included both men and women, senior pastors and a first lady and other lay leaders, and came from multiple denominations, including United Methodist Church, Congregational Methodist, National Missionary Baptist Convention, Inc., and a Non-denominational congregation. Those with “pro-life” attitudes felt abortion is “too common” and “ought to be a last resort” that is not rushed into or taken lightly given the gravity of its implications. They expressed perceptions that abortion is too often thought of as a first option and explained that they would encourage congregants to make well-informed, carefully considered decisions when faced with an unplanned pregnancy. Moreover, participants with “pro-life” attitudes explained that abortion is too often discussed in a “cold and sterile” medical manner. They explained that this perspective is limited because it presents abortion only as a solution to a medical problem, but detaches moral implications of ending the “potential for life.” Participants with “pro-life” attitudes explained it is impossible to honestly discuss abortion in only medical terms; morality must also be considered and negotiated. These participants emphasized the importance of sharing religious beliefs of life and scared worth when providing pastoral care for someone considering abortion.

Participants with “pro-life” attitudes acknowledged abortion as a legal option but explained they would only counsel women to consider this recourse in cases of risk to maternal life or in some cases of sexual assault. Some participants were less decided about the moral acceptability of abortion in cases of rape, stating tensions between the belief that something good might come out of the pregnancy and concerns for the mental health of the mother. One Mainline Protestant pastor raised concerns about abortion in cases of rape and expressed that it may be morally acceptable only when the woman has no shared “responsibility for [the pregnancy],” such as a woman being under the influence of alcohol versus being “attacked by an evil person.” The same participant explained that abortion is not a morally acceptable option for fetal anomaly because such anomalies are the result of “the sinful nature that we’re born into (due to original sin of Adam and Eve)”, and because God does not make mistakes, therefore all pregnancies should be carried to term.

Attitudes in the intermediate, “Gray Area”.

Participants from several denominations such as United Methodist Church, Evangelical Lutheran Church in America, African Methodist Episcopal expressed attitudes intermediate between “pro-life” and “pro-choice.” These participants were tentative about making strong statements about what the ideal resolution of unplanned pregnancies should be and explained that they were not “qualified” to make such determinations for others. Several participants expressed the importance of individual autonomy to make abortion decisions and careful consideration of the context of an unplanned pregnancy in deciding on the ideal resolution of the pregnancy; however, most of the participants with attitudes in the “gray area” expressed that they would prefer abortions are less common. Participants cited tension between belief in the sanctity of life and respect for individual autonomy. One participant described this tension:

“'So I don't believe that it's my right as a human being to tell a woman what they're going to do with their body because a woman and a child are literally inexorably linked as far as being in utero and in womb . And so I have no right to say to someone who's carrying a child that you can or cannot do this or that or the other because that child is your body and you have the right to see your body . But at the same time , there is also the potential for a life being carried inside of that body . And the part of me that values the sacredness of all life says , ‘Oh , but look at the potential there . Look what good that future human being could do in the world . ’ So I sort of stand at a very strange gray area and crossroads with abortion . ” (Senior Pastor, Mainline Protestant)

Some participants in the “Gray Area” cited that abortion may be the best decision for some people if having an abortion would alleviate potential suffering or in cases in which a mother is not able to care for herself or for a child. Another senior pastor explained his view on abortion,

“My personal views on abortion is that I believe that in some cases , abortion could be the best option for that individual , if they come to that conclusion , such as poorly–development of a fetus that does not have , medically speaking , the chance for–productive or normal life outside of the womb . Okay ? People make those decisions on their own . One of the more sensitive issues is having a healthy child , but if that child is the result of rape or incest , I don't believe that God cannot forgive anyone for any decision that possibly could be against his will . His will , of course , is that we have life , but I also hold to this belief that every , every , every–conceivable sin is forgivable by God , except for blasphemy …” (Senior Pastor, Black Protestant)

“Pro-choice”.

There was no identifiable pattern by gender, tradition, denomination, or leadership role among participants who identified themselves as “pro-choice.” These participants discussed tensions between the need for abortion and the need for women to exercise bodily autonomy. They felt pregnancy-related decision making should rest with a pregnant person and God, but they would try to guide people considering abortion to the best outcome for the mother and the baby. They emphasized that their pastoral care would consist of much listening and understanding. A senior pastor at an Episcopal church who identified as “pro-choice” explained that he could not make decisions about abortion for people because to do so would be “treading on a violation of the relationship between [them] and God.”

Most participants with “pro-choice” attitudes expressed that abortion is a psychologically difficult decision that they wished people did not have to go through but underscored that it may be the best option for some people. These participants explained that abortion might be the best decision if there is a risk to the life of the mother, in cases of rape or incest, and in cases of fetal anomaly. Conversely, some participants expressed that abortion should not be used as a primary means of birth control or contraception. A senior pastor at an Episcopal church expressed that abortion should not be allowed for sex-selection, although he did not believe this was a common occurrence. Several other participants acknowledged abortion as a legal option but emphasized the importance of supporting women and providing children the care they need so there are better alternatives to abortion.

Religious and moral beliefs across the abortion attitude spectrum

All life has sacred worth..

All participants expressed that their abortion attitudes are influenced by the understanding and interpretation of Christian scripture and doctrine (See Table 3 ). The majority of participants identified beliefs about sanctity and sacredness of all life as central to their views on abortion. They explained that people are created in God’s image, therefore human life has sacred worth which should be protected. The majority of participants stated views that public and pastoral care conversations about abortion should include recognition of the sacredness of life because Christian believers walk that experience (i.e. it is fundamental to Christian beliefs).

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0235971.t003