Writing an Abstract for Your Research Paper

Definition and Purpose of Abstracts

An abstract is a short summary of your (published or unpublished) research paper, usually about a paragraph (c. 6-7 sentences, 150-250 words) long. A well-written abstract serves multiple purposes:

- an abstract lets readers get the gist or essence of your paper or article quickly, in order to decide whether to read the full paper;

- an abstract prepares readers to follow the detailed information, analyses, and arguments in your full paper;

- and, later, an abstract helps readers remember key points from your paper.

It’s also worth remembering that search engines and bibliographic databases use abstracts, as well as the title, to identify key terms for indexing your published paper. So what you include in your abstract and in your title are crucial for helping other researchers find your paper or article.

If you are writing an abstract for a course paper, your professor may give you specific guidelines for what to include and how to organize your abstract. Similarly, academic journals often have specific requirements for abstracts. So in addition to following the advice on this page, you should be sure to look for and follow any guidelines from the course or journal you’re writing for.

The Contents of an Abstract

Abstracts contain most of the following kinds of information in brief form. The body of your paper will, of course, develop and explain these ideas much more fully. As you will see in the samples below, the proportion of your abstract that you devote to each kind of information—and the sequence of that information—will vary, depending on the nature and genre of the paper that you are summarizing in your abstract. And in some cases, some of this information is implied, rather than stated explicitly. The Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association , which is widely used in the social sciences, gives specific guidelines for what to include in the abstract for different kinds of papers—for empirical studies, literature reviews or meta-analyses, theoretical papers, methodological papers, and case studies.

Here are the typical kinds of information found in most abstracts:

- the context or background information for your research; the general topic under study; the specific topic of your research

- the central questions or statement of the problem your research addresses

- what’s already known about this question, what previous research has done or shown

- the main reason(s) , the exigency, the rationale , the goals for your research—Why is it important to address these questions? Are you, for example, examining a new topic? Why is that topic worth examining? Are you filling a gap in previous research? Applying new methods to take a fresh look at existing ideas or data? Resolving a dispute within the literature in your field? . . .

- your research and/or analytical methods

- your main findings , results , or arguments

- the significance or implications of your findings or arguments.

Your abstract should be intelligible on its own, without a reader’s having to read your entire paper. And in an abstract, you usually do not cite references—most of your abstract will describe what you have studied in your research and what you have found and what you argue in your paper. In the body of your paper, you will cite the specific literature that informs your research.

When to Write Your Abstract

Although you might be tempted to write your abstract first because it will appear as the very first part of your paper, it’s a good idea to wait to write your abstract until after you’ve drafted your full paper, so that you know what you’re summarizing.

What follows are some sample abstracts in published papers or articles, all written by faculty at UW-Madison who come from a variety of disciplines. We have annotated these samples to help you see the work that these authors are doing within their abstracts.

Choosing Verb Tenses within Your Abstract

The social science sample (Sample 1) below uses the present tense to describe general facts and interpretations that have been and are currently true, including the prevailing explanation for the social phenomenon under study. That abstract also uses the present tense to describe the methods, the findings, the arguments, and the implications of the findings from their new research study. The authors use the past tense to describe previous research.

The humanities sample (Sample 2) below uses the past tense to describe completed events in the past (the texts created in the pulp fiction industry in the 1970s and 80s) and uses the present tense to describe what is happening in those texts, to explain the significance or meaning of those texts, and to describe the arguments presented in the article.

The science samples (Samples 3 and 4) below use the past tense to describe what previous research studies have done and the research the authors have conducted, the methods they have followed, and what they have found. In their rationale or justification for their research (what remains to be done), they use the present tense. They also use the present tense to introduce their study (in Sample 3, “Here we report . . .”) and to explain the significance of their study (In Sample 3, This reprogramming . . . “provides a scalable cell source for. . .”).

Sample Abstract 1

From the social sciences.

Reporting new findings about the reasons for increasing economic homogamy among spouses

Gonalons-Pons, Pilar, and Christine R. Schwartz. “Trends in Economic Homogamy: Changes in Assortative Mating or the Division of Labor in Marriage?” Demography , vol. 54, no. 3, 2017, pp. 985-1005.

![abstract paper design “The growing economic resemblance of spouses has contributed to rising inequality by increasing the number of couples in which there are two high- or two low-earning partners. [Annotation for the previous sentence: The first sentence introduces the topic under study (the “economic resemblance of spouses”). This sentence also implies the question underlying this research study: what are the various causes—and the interrelationships among them—for this trend?] The dominant explanation for this trend is increased assortative mating. Previous research has primarily relied on cross-sectional data and thus has been unable to disentangle changes in assortative mating from changes in the division of spouses’ paid labor—a potentially key mechanism given the dramatic rise in wives’ labor supply. [Annotation for the previous two sentences: These next two sentences explain what previous research has demonstrated. By pointing out the limitations in the methods that were used in previous studies, they also provide a rationale for new research.] We use data from the Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID) to decompose the increase in the correlation between spouses’ earnings and its contribution to inequality between 1970 and 2013 into parts due to (a) changes in assortative mating, and (b) changes in the division of paid labor. [Annotation for the previous sentence: The data, research and analytical methods used in this new study.] Contrary to what has often been assumed, the rise of economic homogamy and its contribution to inequality is largely attributable to changes in the division of paid labor rather than changes in sorting on earnings or earnings potential. Our findings indicate that the rise of economic homogamy cannot be explained by hypotheses centered on meeting and matching opportunities, and they show where in this process inequality is generated and where it is not.” (p. 985) [Annotation for the previous two sentences: The major findings from and implications and significance of this study.]](https://writing.wisc.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/535/2019/08/Abstract-1.png)

Sample Abstract 2

From the humanities.

Analyzing underground pulp fiction publications in Tanzania, this article makes an argument about the cultural significance of those publications

Emily Callaci. “Street Textuality: Socialism, Masculinity, and Urban Belonging in Tanzania’s Pulp Fiction Publishing Industry, 1975-1985.” Comparative Studies in Society and History , vol. 59, no. 1, 2017, pp. 183-210.

![abstract paper design “From the mid-1970s through the mid-1980s, a network of young urban migrant men created an underground pulp fiction publishing industry in the city of Dar es Salaam. [Annotation for the previous sentence: The first sentence introduces the context for this research and announces the topic under study.] As texts that were produced in the underground economy of a city whose trajectory was increasingly charted outside of formalized planning and investment, these novellas reveal more than their narrative content alone. These texts were active components in the urban social worlds of the young men who produced them. They reveal a mode of urbanism otherwise obscured by narratives of decolonization, in which urban belonging was constituted less by national citizenship than by the construction of social networks, economic connections, and the crafting of reputations. This article argues that pulp fiction novellas of socialist era Dar es Salaam are artifacts of emergent forms of male sociability and mobility. In printing fictional stories about urban life on pilfered paper and ink, and distributing their texts through informal channels, these writers not only described urban communities, reputations, and networks, but also actually created them.” (p. 210) [Annotation for the previous sentences: The remaining sentences in this abstract interweave other essential information for an abstract for this article. The implied research questions: What do these texts mean? What is their historical and cultural significance, produced at this time, in this location, by these authors? The argument and the significance of this analysis in microcosm: these texts “reveal a mode or urbanism otherwise obscured . . .”; and “This article argues that pulp fiction novellas. . . .” This section also implies what previous historical research has obscured. And through the details in its argumentative claims, this section of the abstract implies the kinds of methods the author has used to interpret the novellas and the concepts under study (e.g., male sociability and mobility, urban communities, reputations, network. . . ).]](https://writing.wisc.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/535/2019/08/Abstract-2.png)

Sample Abstract/Summary 3

From the sciences.

Reporting a new method for reprogramming adult mouse fibroblasts into induced cardiac progenitor cells

Lalit, Pratik A., Max R. Salick, Daryl O. Nelson, Jayne M. Squirrell, Christina M. Shafer, Neel G. Patel, Imaan Saeed, Eric G. Schmuck, Yogananda S. Markandeya, Rachel Wong, Martin R. Lea, Kevin W. Eliceiri, Timothy A. Hacker, Wendy C. Crone, Michael Kyba, Daniel J. Garry, Ron Stewart, James A. Thomson, Karen M. Downs, Gary E. Lyons, and Timothy J. Kamp. “Lineage Reprogramming of Fibroblasts into Proliferative Induced Cardiac Progenitor Cells by Defined Factors.” Cell Stem Cell , vol. 18, 2016, pp. 354-367.

![abstract paper design “Several studies have reported reprogramming of fibroblasts into induced cardiomyocytes; however, reprogramming into proliferative induced cardiac progenitor cells (iCPCs) remains to be accomplished. [Annotation for the previous sentence: The first sentence announces the topic under study, summarizes what’s already known or been accomplished in previous research, and signals the rationale and goals are for the new research and the problem that the new research solves: How can researchers reprogram fibroblasts into iCPCs?] Here we report that a combination of 11 or 5 cardiac factors along with canonical Wnt and JAK/STAT signaling reprogrammed adult mouse cardiac, lung, and tail tip fibroblasts into iCPCs. The iCPCs were cardiac mesoderm-restricted progenitors that could be expanded extensively while maintaining multipo-tency to differentiate into cardiomyocytes, smooth muscle cells, and endothelial cells in vitro. Moreover, iCPCs injected into the cardiac crescent of mouse embryos differentiated into cardiomyocytes. iCPCs transplanted into the post-myocardial infarction mouse heart improved survival and differentiated into cardiomyocytes, smooth muscle cells, and endothelial cells. [Annotation for the previous four sentences: The methods the researchers developed to achieve their goal and a description of the results.] Lineage reprogramming of adult somatic cells into iCPCs provides a scalable cell source for drug discovery, disease modeling, and cardiac regenerative therapy.” (p. 354) [Annotation for the previous sentence: The significance or implications—for drug discovery, disease modeling, and therapy—of this reprogramming of adult somatic cells into iCPCs.]](https://writing.wisc.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/535/2019/08/Abstract-3.png)

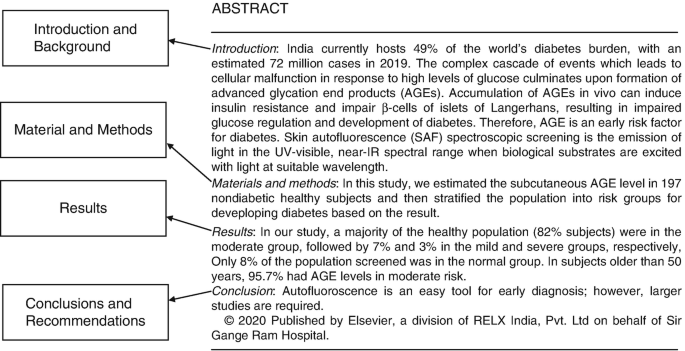

Sample Abstract 4, a Structured Abstract

Reporting results about the effectiveness of antibiotic therapy in managing acute bacterial sinusitis, from a rigorously controlled study

Note: This journal requires authors to organize their abstract into four specific sections, with strict word limits. Because the headings for this structured abstract are self-explanatory, we have chosen not to add annotations to this sample abstract.

Wald, Ellen R., David Nash, and Jens Eickhoff. “Effectiveness of Amoxicillin/Clavulanate Potassium in the Treatment of Acute Bacterial Sinusitis in Children.” Pediatrics , vol. 124, no. 1, 2009, pp. 9-15.

“OBJECTIVE: The role of antibiotic therapy in managing acute bacterial sinusitis (ABS) in children is controversial. The purpose of this study was to determine the effectiveness of high-dose amoxicillin/potassium clavulanate in the treatment of children diagnosed with ABS.

METHODS : This was a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Children 1 to 10 years of age with a clinical presentation compatible with ABS were eligible for participation. Patients were stratified according to age (<6 or ≥6 years) and clinical severity and randomly assigned to receive either amoxicillin (90 mg/kg) with potassium clavulanate (6.4 mg/kg) or placebo. A symptom survey was performed on days 0, 1, 2, 3, 5, 7, 10, 20, and 30. Patients were examined on day 14. Children’s conditions were rated as cured, improved, or failed according to scoring rules.

RESULTS: Two thousand one hundred thirty-five children with respiratory complaints were screened for enrollment; 139 (6.5%) had ABS. Fifty-eight patients were enrolled, and 56 were randomly assigned. The mean age was 6630 months. Fifty (89%) patients presented with persistent symptoms, and 6 (11%) presented with nonpersistent symptoms. In 24 (43%) children, the illness was classified as mild, whereas in the remaining 32 (57%) children it was severe. Of the 28 children who received the antibiotic, 14 (50%) were cured, 4 (14%) were improved, 4(14%) experienced treatment failure, and 6 (21%) withdrew. Of the 28children who received placebo, 4 (14%) were cured, 5 (18%) improved, and 19 (68%) experienced treatment failure. Children receiving the antibiotic were more likely to be cured (50% vs 14%) and less likely to have treatment failure (14% vs 68%) than children receiving the placebo.

CONCLUSIONS : ABS is a common complication of viral upper respiratory infections. Amoxicillin/potassium clavulanate results in significantly more cures and fewer failures than placebo, according to parental report of time to resolution.” (9)

Some Excellent Advice about Writing Abstracts for Basic Science Research Papers, by Professor Adriano Aguzzi from the Institute of Neuropathology at the University of Zurich:

Academic and Professional Writing

This is an accordion element with a series of buttons that open and close related content panels.

Analysis Papers

Reading Poetry

A Short Guide to Close Reading for Literary Analysis

Using Literary Quotations

Play Reviews

Writing a Rhetorical Précis to Analyze Nonfiction Texts

Incorporating Interview Data

Grant Proposals

Planning and Writing a Grant Proposal: The Basics

Additional Resources for Grants and Proposal Writing

Job Materials and Application Essays

Writing Personal Statements for Ph.D. Programs

- Before you begin: useful tips for writing your essay

- Guided brainstorming exercises

- Get more help with your essay

- Frequently Asked Questions

Resume Writing Tips

CV Writing Tips

Cover Letters

Business Letters

Proposals and Dissertations

Resources for Proposal Writers

Resources for Dissertators

Research Papers

Planning and Writing Research Papers

Quoting and Paraphrasing

Writing Annotated Bibliographies

Creating Poster Presentations

Thank-You Notes

Advice for Students Writing Thank-You Notes to Donors

Reading for a Review

Critical Reviews

Writing a Review of Literature

Scientific Reports

Scientific Report Format

Sample Lab Assignment

Writing for the Web

Writing an Effective Blog Post

Writing for Social Media: A Guide for Academics

- USC Libraries

- Research Guides

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper

- 3. The Abstract

- Purpose of Guide

- Design Flaws to Avoid

- Independent and Dependent Variables

- Glossary of Research Terms

- Reading Research Effectively

- Narrowing a Topic Idea

- Broadening a Topic Idea

- Extending the Timeliness of a Topic Idea

- Academic Writing Style

- Applying Critical Thinking

- Choosing a Title

- Making an Outline

- Paragraph Development

- Research Process Video Series

- Executive Summary

- The C.A.R.S. Model

- Background Information

- The Research Problem/Question

- Theoretical Framework

- Citation Tracking

- Content Alert Services

- Evaluating Sources

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

- Tiertiary Sources

- Scholarly vs. Popular Publications

- Qualitative Methods

- Quantitative Methods

- Insiderness

- Using Non-Textual Elements

- Limitations of the Study

- Common Grammar Mistakes

- Writing Concisely

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Footnotes or Endnotes?

- Further Readings

- Generative AI and Writing

- USC Libraries Tutorials and Other Guides

- Bibliography

An abstract summarizes, usually in one paragraph of 300 words or less, the major aspects of the entire paper in a prescribed sequence that includes: 1) the overall purpose of the study and the research problem(s) you investigated; 2) the basic design of the study; 3) major findings or trends found as a result of your analysis; and, 4) a brief summary of your interpretations and conclusions.

Writing an Abstract. The Writing Center. Clarion University, 2009; Writing an Abstract for Your Research Paper. The Writing Center, University of Wisconsin, Madison; Koltay, Tibor. Abstracts and Abstracting: A Genre and Set of Skills for the Twenty-first Century . Oxford, UK: Chandos Publishing, 2010;

Importance of a Good Abstract

Sometimes your professor will ask you to include an abstract, or general summary of your work, with your research paper. The abstract allows you to elaborate upon each major aspect of the paper and helps readers decide whether they want to read the rest of the paper. Therefore, enough key information [e.g., summary results, observations, trends, etc.] must be included to make the abstract useful to someone who may want to examine your work.

How do you know when you have enough information in your abstract? A simple rule-of-thumb is to imagine that you are another researcher doing a similar study. Then ask yourself: if your abstract was the only part of the paper you could access, would you be happy with the amount of information presented there? Does it tell the whole story about your study? If the answer is "no" then the abstract likely needs to be revised.

Farkas, David K. “A Scheme for Understanding and Writing Summaries.” Technical Communication 67 (August 2020): 45-60; How to Write a Research Abstract. Office of Undergraduate Research. University of Kentucky; Staiger, David L. “What Today’s Students Need to Know about Writing Abstracts.” International Journal of Business Communication January 3 (1966): 29-33; Swales, John M. and Christine B. Feak. Abstracts and the Writing of Abstracts . Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 2009.

Structure and Writing Style

I. Types of Abstracts

To begin, you need to determine which type of abstract you should include with your paper. There are four general types.

Critical Abstract A critical abstract provides, in addition to describing main findings and information, a judgment or comment about the study’s validity, reliability, or completeness. The researcher evaluates the paper and often compares it with other works on the same subject. Critical abstracts are generally 400-500 words in length due to the additional interpretive commentary. These types of abstracts are used infrequently.

Descriptive Abstract A descriptive abstract indicates the type of information found in the work. It makes no judgments about the work, nor does it provide results or conclusions of the research. It does incorporate key words found in the text and may include the purpose, methods, and scope of the research. Essentially, the descriptive abstract only describes the work being summarized. Some researchers consider it an outline of the work, rather than a summary. Descriptive abstracts are usually very short, 100 words or less. Informative Abstract The majority of abstracts are informative. While they still do not critique or evaluate a work, they do more than describe it. A good informative abstract acts as a surrogate for the work itself. That is, the researcher presents and explains all the main arguments and the important results and evidence in the paper. An informative abstract includes the information that can be found in a descriptive abstract [purpose, methods, scope] but it also includes the results and conclusions of the research and the recommendations of the author. The length varies according to discipline, but an informative abstract is usually no more than 300 words in length.

Highlight Abstract A highlight abstract is specifically written to attract the reader’s attention to the study. No pretense is made of there being either a balanced or complete picture of the paper and, in fact, incomplete and leading remarks may be used to spark the reader’s interest. In that a highlight abstract cannot stand independent of its associated article, it is not a true abstract and, therefore, rarely used in academic writing.

II. Writing Style

Use the active voice when possible , but note that much of your abstract may require passive sentence constructions. Regardless, write your abstract using concise, but complete, sentences. Get to the point quickly and always use the past tense because you are reporting on a study that has been completed.

Abstracts should be formatted as a single paragraph in a block format and with no paragraph indentations. In most cases, the abstract page immediately follows the title page. Do not number the page. Rules set forth in writing manual vary but, in general, you should center the word "Abstract" at the top of the page with double spacing between the heading and the abstract. The final sentences of an abstract concisely summarize your study’s conclusions, implications, or applications to practice and, if appropriate, can be followed by a statement about the need for additional research revealed from the findings.

Composing Your Abstract

Although it is the first section of your paper, the abstract should be written last since it will summarize the contents of your entire paper. A good strategy to begin composing your abstract is to take whole sentences or key phrases from each section of the paper and put them in a sequence that summarizes the contents. Then revise or add connecting phrases or words to make the narrative flow clearly and smoothly. Note that statistical findings should be reported parenthetically [i.e., written in parentheses].

Before handing in your final paper, check to make sure that the information in the abstract completely agrees with what you have written in the paper. Think of the abstract as a sequential set of complete sentences describing the most crucial information using the fewest necessary words. The abstract SHOULD NOT contain:

- A catchy introductory phrase, provocative quote, or other device to grab the reader's attention,

- Lengthy background or contextual information,

- Redundant phrases, unnecessary adverbs and adjectives, and repetitive information;

- Acronyms or abbreviations,

- References to other literature [say something like, "current research shows that..." or "studies have indicated..."],

- Using ellipticals [i.e., ending with "..."] or incomplete sentences,

- Jargon or terms that may be confusing to the reader,

- Citations to other works, and

- Any sort of image, illustration, figure, or table, or references to them.

Abstract. Writing Center. University of Kansas; Abstract. The Structure, Format, Content, and Style of a Journal-Style Scientific Paper. Department of Biology. Bates College; Abstracts. The Writing Center. University of North Carolina; Borko, Harold and Seymour Chatman. "Criteria for Acceptable Abstracts: A Survey of Abstracters' Instructions." American Documentation 14 (April 1963): 149-160; Abstracts. The Writer’s Handbook. Writing Center. University of Wisconsin, Madison; Hartley, James and Lucy Betts. "Common Weaknesses in Traditional Abstracts in the Social Sciences." Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology 60 (October 2009): 2010-2018; Koltay, Tibor. Abstracts and Abstracting: A Genre and Set of Skills for the Twenty-first Century. Oxford, UK: Chandos Publishing, 2010; Procter, Margaret. The Abstract. University College Writing Centre. University of Toronto; Riordan, Laura. “Mastering the Art of Abstracts.” The Journal of the American Osteopathic Association 115 (January 2015 ): 41-47; Writing Report Abstracts. The Writing Lab and The OWL. Purdue University; Writing Abstracts. Writing Tutorial Services, Center for Innovative Teaching and Learning. Indiana University; Koltay, Tibor. Abstracts and Abstracting: A Genre and Set of Skills for the Twenty-First Century . Oxford, UK: 2010; Writing an Abstract for Your Research Paper. The Writing Center, University of Wisconsin, Madison.

Writing Tip

Never Cite Just the Abstract!

Citing to just a journal article's abstract does not confirm for the reader that you have conducted a thorough or reliable review of the literature. If the full-text is not available, go to the USC Libraries main page and enter the title of the article [NOT the title of the journal]. If the Libraries have a subscription to the journal, the article should appear with a link to the full-text or to the journal publisher page where you can get the article. If the article does not appear, try searching Google Scholar using the link on the USC Libraries main page. If you still can't find the article after doing this, contact a librarian or you can request it from our free i nterlibrary loan and document delivery service .

- << Previous: Research Process Video Series

- Next: Executive Summary >>

- Last Updated: May 25, 2024 4:09 PM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide

What this handout is about

This handout provides definitions and examples of the two main types of abstracts: descriptive and informative. It also provides guidelines for constructing an abstract and general tips for you to keep in mind when drafting. Finally, it includes a few examples of abstracts broken down into their component parts.

What is an abstract?

An abstract is a self-contained, short, and powerful statement that describes a larger work. Components vary according to discipline. An abstract of a social science or scientific work may contain the scope, purpose, results, and contents of the work. An abstract of a humanities work may contain the thesis, background, and conclusion of the larger work. An abstract is not a review, nor does it evaluate the work being abstracted. While it contains key words found in the larger work, the abstract is an original document rather than an excerpted passage.

Why write an abstract?

You may write an abstract for various reasons. The two most important are selection and indexing. Abstracts allow readers who may be interested in a longer work to quickly decide whether it is worth their time to read it. Also, many online databases use abstracts to index larger works. Therefore, abstracts should contain keywords and phrases that allow for easy searching.

Say you are beginning a research project on how Brazilian newspapers helped Brazil’s ultra-liberal president Luiz Ignácio da Silva wrest power from the traditional, conservative power base. A good first place to start your research is to search Dissertation Abstracts International for all dissertations that deal with the interaction between newspapers and politics. “Newspapers and politics” returned 569 hits. A more selective search of “newspapers and Brazil” returned 22 hits. That is still a fair number of dissertations. Titles can sometimes help winnow the field, but many titles are not very descriptive. For example, one dissertation is titled “Rhetoric and Riot in Rio de Janeiro.” It is unclear from the title what this dissertation has to do with newspapers in Brazil. One option would be to download or order the entire dissertation on the chance that it might speak specifically to the topic. A better option is to read the abstract. In this case, the abstract reveals the main focus of the dissertation:

This dissertation examines the role of newspaper editors in the political turmoil and strife that characterized late First Empire Rio de Janeiro (1827-1831). Newspaper editors and their journals helped change the political culture of late First Empire Rio de Janeiro by involving the people in the discussion of state. This change in political culture is apparent in Emperor Pedro I’s gradual loss of control over the mechanisms of power. As the newspapers became more numerous and powerful, the Emperor lost his legitimacy in the eyes of the people. To explore the role of the newspapers in the political events of the late First Empire, this dissertation analyzes all available newspapers published in Rio de Janeiro from 1827 to 1831. Newspapers and their editors were leading forces in the effort to remove power from the hands of the ruling elite and place it under the control of the people. In the process, newspapers helped change how politics operated in the constitutional monarchy of Brazil.

From this abstract you now know that although the dissertation has nothing to do with modern Brazilian politics, it does cover the role of newspapers in changing traditional mechanisms of power. After reading the abstract, you can make an informed judgment about whether the dissertation would be worthwhile to read.

Besides selection, the other main purpose of the abstract is for indexing. Most article databases in the online catalog of the library enable you to search abstracts. This allows for quick retrieval by users and limits the extraneous items recalled by a “full-text” search. However, for an abstract to be useful in an online retrieval system, it must incorporate the key terms that a potential researcher would use to search. For example, if you search Dissertation Abstracts International using the keywords “France” “revolution” and “politics,” the search engine would search through all the abstracts in the database that included those three words. Without an abstract, the search engine would be forced to search titles, which, as we have seen, may not be fruitful, or else search the full text. It’s likely that a lot more than 60 dissertations have been written with those three words somewhere in the body of the entire work. By incorporating keywords into the abstract, the author emphasizes the central topics of the work and gives prospective readers enough information to make an informed judgment about the applicability of the work.

When do people write abstracts?

- when submitting articles to journals, especially online journals

- when applying for research grants

- when writing a book proposal

- when completing the Ph.D. dissertation or M.A. thesis

- when writing a proposal for a conference paper

- when writing a proposal for a book chapter

Most often, the author of the entire work (or prospective work) writes the abstract. However, there are professional abstracting services that hire writers to draft abstracts of other people’s work. In a work with multiple authors, the first author usually writes the abstract. Undergraduates are sometimes asked to draft abstracts of books/articles for classmates who have not read the larger work.

Types of abstracts

There are two types of abstracts: descriptive and informative. They have different aims, so as a consequence they have different components and styles. There is also a third type called critical, but it is rarely used. If you want to find out more about writing a critique or a review of a work, see the UNC Writing Center handout on writing a literature review . If you are unsure which type of abstract you should write, ask your instructor (if the abstract is for a class) or read other abstracts in your field or in the journal where you are submitting your article.

Descriptive abstracts

A descriptive abstract indicates the type of information found in the work. It makes no judgments about the work, nor does it provide results or conclusions of the research. It does incorporate key words found in the text and may include the purpose, methods, and scope of the research. Essentially, the descriptive abstract describes the work being abstracted. Some people consider it an outline of the work, rather than a summary. Descriptive abstracts are usually very short—100 words or less.

Informative abstracts

The majority of abstracts are informative. While they still do not critique or evaluate a work, they do more than describe it. A good informative abstract acts as a surrogate for the work itself. That is, the writer presents and explains all the main arguments and the important results and evidence in the complete article/paper/book. An informative abstract includes the information that can be found in a descriptive abstract (purpose, methods, scope) but also includes the results and conclusions of the research and the recommendations of the author. The length varies according to discipline, but an informative abstract is rarely more than 10% of the length of the entire work. In the case of a longer work, it may be much less.

Here are examples of a descriptive and an informative abstract of this handout on abstracts . Descriptive abstract:

The two most common abstract types—descriptive and informative—are described and examples of each are provided.

Informative abstract:

Abstracts present the essential elements of a longer work in a short and powerful statement. The purpose of an abstract is to provide prospective readers the opportunity to judge the relevance of the longer work to their projects. Abstracts also include the key terms found in the longer work and the purpose and methods of the research. Authors abstract various longer works, including book proposals, dissertations, and online journal articles. There are two main types of abstracts: descriptive and informative. A descriptive abstract briefly describes the longer work, while an informative abstract presents all the main arguments and important results. This handout provides examples of various types of abstracts and instructions on how to construct one.

Which type should I use?

Your best bet in this case is to ask your instructor or refer to the instructions provided by the publisher. You can also make a guess based on the length allowed; i.e., 100-120 words = descriptive; 250+ words = informative.

How do I write an abstract?

The format of your abstract will depend on the work being abstracted. An abstract of a scientific research paper will contain elements not found in an abstract of a literature article, and vice versa. However, all abstracts share several mandatory components, and there are also some optional parts that you can decide to include or not. When preparing to draft your abstract, keep the following key process elements in mind:

- Reason for writing: What is the importance of the research? Why would a reader be interested in the larger work?

- Problem: What problem does this work attempt to solve? What is the scope of the project? What is the main argument/thesis/claim?

- Methodology: An abstract of a scientific work may include specific models or approaches used in the larger study. Other abstracts may describe the types of evidence used in the research.

- Results: Again, an abstract of a scientific work may include specific data that indicates the results of the project. Other abstracts may discuss the findings in a more general way.

- Implications: What changes should be implemented as a result of the findings of the work? How does this work add to the body of knowledge on the topic?

(This list of elements is adapted with permission from Philip Koopman, “How to Write an Abstract.” )

All abstracts include:

- A full citation of the source, preceding the abstract.

- The most important information first.

- The same type and style of language found in the original, including technical language.

- Key words and phrases that quickly identify the content and focus of the work.

- Clear, concise, and powerful language.

Abstracts may include:

- The thesis of the work, usually in the first sentence.

- Background information that places the work in the larger body of literature.

- The same chronological structure as the original work.

How not to write an abstract:

- Do not refer extensively to other works.

- Do not add information not contained in the original work.

- Do not define terms.

If you are abstracting your own writing

When abstracting your own work, it may be difficult to condense a piece of writing that you have agonized over for weeks (or months, or even years) into a 250-word statement. There are some tricks that you could use to make it easier, however.

Reverse outlining:

This technique is commonly used when you are having trouble organizing your own writing. The process involves writing down the main idea of each paragraph on a separate piece of paper– see our short video . For the purposes of writing an abstract, try grouping the main ideas of each section of the paper into a single sentence. Practice grouping ideas using webbing or color coding .

For a scientific paper, you may have sections titled Purpose, Methods, Results, and Discussion. Each one of these sections will be longer than one paragraph, but each is grouped around a central idea. Use reverse outlining to discover the central idea in each section and then distill these ideas into one statement.

Cut and paste:

To create a first draft of an abstract of your own work, you can read through the entire paper and cut and paste sentences that capture key passages. This technique is useful for social science research with findings that cannot be encapsulated by neat numbers or concrete results. A well-written humanities draft will have a clear and direct thesis statement and informative topic sentences for paragraphs or sections. Isolate these sentences in a separate document and work on revising them into a unified paragraph.

If you are abstracting someone else’s writing

When abstracting something you have not written, you cannot summarize key ideas just by cutting and pasting. Instead, you must determine what a prospective reader would want to know about the work. There are a few techniques that will help you in this process:

Identify key terms:

Search through the entire document for key terms that identify the purpose, scope, and methods of the work. Pay close attention to the Introduction (or Purpose) and the Conclusion (or Discussion). These sections should contain all the main ideas and key terms in the paper. When writing the abstract, be sure to incorporate the key terms.

Highlight key phrases and sentences:

Instead of cutting and pasting the actual words, try highlighting sentences or phrases that appear to be central to the work. Then, in a separate document, rewrite the sentences and phrases in your own words.

Don’t look back:

After reading the entire work, put it aside and write a paragraph about the work without referring to it. In the first draft, you may not remember all the key terms or the results, but you will remember what the main point of the work was. Remember not to include any information you did not get from the work being abstracted.

Revise, revise, revise

No matter what type of abstract you are writing, or whether you are abstracting your own work or someone else’s, the most important step in writing an abstract is to revise early and often. When revising, delete all extraneous words and incorporate meaningful and powerful words. The idea is to be as clear and complete as possible in the shortest possible amount of space. The Word Count feature of Microsoft Word can help you keep track of how long your abstract is and help you hit your target length.

Example 1: Humanities abstract

Kenneth Tait Andrews, “‘Freedom is a constant struggle’: The dynamics and consequences of the Mississippi Civil Rights Movement, 1960-1984” Ph.D. State University of New York at Stony Brook, 1997 DAI-A 59/02, p. 620, Aug 1998

This dissertation examines the impacts of social movements through a multi-layered study of the Mississippi Civil Rights Movement from its peak in the early 1960s through the early 1980s. By examining this historically important case, I clarify the process by which movements transform social structures and the constraints movements face when they try to do so. The time period studied includes the expansion of voting rights and gains in black political power, the desegregation of public schools and the emergence of white-flight academies, and the rise and fall of federal anti-poverty programs. I use two major research strategies: (1) a quantitative analysis of county-level data and (2) three case studies. Data have been collected from archives, interviews, newspapers, and published reports. This dissertation challenges the argument that movements are inconsequential. Some view federal agencies, courts, political parties, or economic elites as the agents driving institutional change, but typically these groups acted in response to the leverage brought to bear by the civil rights movement. The Mississippi movement attempted to forge independent structures for sustaining challenges to local inequities and injustices. By propelling change in an array of local institutions, movement infrastructures had an enduring legacy in Mississippi.

Now let’s break down this abstract into its component parts to see how the author has distilled his entire dissertation into a ~200 word abstract.

What the dissertation does This dissertation examines the impacts of social movements through a multi-layered study of the Mississippi Civil Rights Movement from its peak in the early 1960s through the early 1980s. By examining this historically important case, I clarify the process by which movements transform social structures and the constraints movements face when they try to do so.

How the dissertation does it The time period studied in this dissertation includes the expansion of voting rights and gains in black political power, the desegregation of public schools and the emergence of white-flight academies, and the rise and fall of federal anti-poverty programs. I use two major research strategies: (1) a quantitative analysis of county-level data and (2) three case studies.

What materials are used Data have been collected from archives, interviews, newspapers, and published reports.

Conclusion This dissertation challenges the argument that movements are inconsequential. Some view federal agencies, courts, political parties, or economic elites as the agents driving institutional change, but typically these groups acted in response to movement demands and the leverage brought to bear by the civil rights movement. The Mississippi movement attempted to forge independent structures for sustaining challenges to local inequities and injustices. By propelling change in an array of local institutions, movement infrastructures had an enduring legacy in Mississippi.

Keywords social movements Civil Rights Movement Mississippi voting rights desegregation

Example 2: Science Abstract

Luis Lehner, “Gravitational radiation from black hole spacetimes” Ph.D. University of Pittsburgh, 1998 DAI-B 59/06, p. 2797, Dec 1998

The problem of detecting gravitational radiation is receiving considerable attention with the construction of new detectors in the United States, Europe, and Japan. The theoretical modeling of the wave forms that would be produced in particular systems will expedite the search for and analysis of detected signals. The characteristic formulation of GR is implemented to obtain an algorithm capable of evolving black holes in 3D asymptotically flat spacetimes. Using compactification techniques, future null infinity is included in the evolved region, which enables the unambiguous calculation of the radiation produced by some compact source. A module to calculate the waveforms is constructed and included in the evolution algorithm. This code is shown to be second-order convergent and to handle highly non-linear spacetimes. In particular, we have shown that the code can handle spacetimes whose radiation is equivalent to a galaxy converting its whole mass into gravitational radiation in one second. We further use the characteristic formulation to treat the region close to the singularity in black hole spacetimes. The code carefully excises a region surrounding the singularity and accurately evolves generic black hole spacetimes with apparently unlimited stability.

This science abstract covers much of the same ground as the humanities one, but it asks slightly different questions.

Why do this study The problem of detecting gravitational radiation is receiving considerable attention with the construction of new detectors in the United States, Europe, and Japan. The theoretical modeling of the wave forms that would be produced in particular systems will expedite the search and analysis of the detected signals.

What the study does The characteristic formulation of GR is implemented to obtain an algorithm capable of evolving black holes in 3D asymptotically flat spacetimes. Using compactification techniques, future null infinity is included in the evolved region, which enables the unambiguous calculation of the radiation produced by some compact source. A module to calculate the waveforms is constructed and included in the evolution algorithm.

Results This code is shown to be second-order convergent and to handle highly non-linear spacetimes. In particular, we have shown that the code can handle spacetimes whose radiation is equivalent to a galaxy converting its whole mass into gravitational radiation in one second. We further use the characteristic formulation to treat the region close to the singularity in black hole spacetimes. The code carefully excises a region surrounding the singularity and accurately evolves generic black hole spacetimes with apparently unlimited stability.

Keywords gravitational radiation (GR) spacetimes black holes

Works consulted

We consulted these works while writing this handout. This is not a comprehensive list of resources on the handout’s topic, and we encourage you to do your own research to find additional publications. Please do not use this list as a model for the format of your own reference list, as it may not match the citation style you are using. For guidance on formatting citations, please see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial . We revise these tips periodically and welcome feedback.

Belcher, Wendy Laura. 2009. Writing Your Journal Article in Twelve Weeks: A Guide to Academic Publishing Success. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Press.

Koopman, Philip. 1997. “How to Write an Abstract.” Carnegie Mellon University. October 1997. http://users.ece.cmu.edu/~koopman/essays/abstract.html .

Lancaster, F.W. 2003. Indexing And Abstracting in Theory and Practice , 3rd ed. London: Facet Publishing.

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout and attribute the source: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Make a Gift

- Features for Creative Writers

- Features for Work

- Features for Higher Education

- Features for Teachers

- Features for Non-Native Speakers

- Learn Blog Grammar Guide Community Events FAQ

- Grammar Guide

How to Write an Abstract (With Examples)

Sarah Oakley

Table of Contents

What is an abstract in a paper, how long should an abstract be, 5 steps for writing an abstract, examples of an abstract, how prowritingaid can help you write an abstract.

If you are writing a scientific research paper or a book proposal, you need to know how to write an abstract, which summarizes the contents of the paper or book.

When researchers are looking for peer-reviewed papers to use in their studies, the first place they will check is the abstract to see if it applies to their work. Therefore, your abstract is one of the most important parts of your entire paper.

In this article, we’ll explain what an abstract is, what it should include, and how to write one.

An abstract is a concise summary of the details within a report. Some abstracts give more details than others, but the main things you’ll be talking about are why you conducted the research, what you did, and what the results show.

When a reader is deciding whether to read your paper completely, they will first look at the abstract. You need to be concise in your abstract and give the reader the most important information so they can determine if they want to read the whole paper.

Remember that an abstract is the last thing you’ll want to write for the research paper because it directly references parts of the report. If you haven’t written the report, you won’t know what to include in your abstract.

If you are writing a paper for a journal or an assignment, the publication or academic institution might have specific formatting rules for how long your abstract should be. However, if they don’t, most abstracts are between 150 and 300 words long.

A short word count means your writing has to be precise and without filler words or phrases. Once you’ve written a first draft, you can always use an editing tool, such as ProWritingAid, to identify areas where you can reduce words and increase readability.

If your abstract is over the word limit, and you’ve edited it but still can’t figure out how to reduce it further, your abstract might include some things that aren’t needed. Here’s a list of three elements you can remove from your abstract:

Discussion : You don’t need to go into detail about the findings of your research because your reader will find your discussion within the paper.

Definition of terms : Your readers are interested the field you are writing about, so they are likely to understand the terms you are using. If not, they can always look them up. Your readers do not expect you to give a definition of terms in your abstract.

References and citations : You can mention there have been studies that support or have inspired your research, but you do not need to give details as the reader will find them in your bibliography.

Good writing = better grades

ProWritingAid will help you improve the style, strength, and clarity of all your assignments.

If you’ve never written an abstract before, and you’re wondering how to write an abstract, we’ve got some steps for you to follow. It’s best to start with planning your abstract, so we’ve outlined the details you need to include in your plan before you write.

Remember to consider your audience when you’re planning and writing your abstract. They are likely to skim read your abstract, so you want to be sure your abstract delivers all the information they’re expecting to see at key points.

1. What Should an Abstract Include?

Abstracts have a lot of information to cover in a short number of words, so it’s important to know what to include. There are three elements that need to be present in your abstract:

Your context is the background for where your research sits within your field of study. You should briefly mention any previous scientific papers or experiments that have led to your hypothesis and how research develops in those studies.

Your hypothesis is your prediction of what your study will show. As you are writing your abstract after you have conducted your research, you should still include your hypothesis in your abstract because it shows the motivation for your paper.

Throughout your abstract, you also need to include keywords and phrases that will help researchers to find your article in the databases they’re searching. Make sure the keywords are specific to your field of study and the subject you’re reporting on, otherwise your article might not reach the relevant audience.

2. Can You Use First Person in an Abstract?

You might think that first person is too informal for a research paper, but it’s not. Historically, writers of academic reports avoided writing in first person to uphold the formality standards of the time. However, first person is more accepted in research papers in modern times.

If you’re still unsure whether to write in first person for your abstract, refer to any style guide rules imposed by the journal you’re writing for or your teachers if you are writing an assignment.

3. Abstract Structure

Some scientific journals have strict rules on how to structure an abstract, so it’s best to check those first. If you don’t have any style rules to follow, try using the IMRaD structure, which stands for Introduction, Methodology, Results, and Discussion.

Following the IMRaD structure, start with an introduction. The amount of background information you should include depends on your specific research area. Adding a broad overview gives you less room to include other details. Remember to include your hypothesis in this section.

The next part of your abstract should cover your methodology. Try to include the following details if they apply to your study:

What type of research was conducted?

How were the test subjects sampled?

What were the sample sizes?

What was done to each group?

How long was the experiment?

How was data recorded and interpreted?

Following the methodology, include a sentence or two about the results, which is where your reader will determine if your research supports or contradicts their own investigations.

The results are also where most people will want to find out what your outcomes were, even if they are just mildly interested in your research area. You should be specific about all the details but as concise as possible.

The last few sentences are your conclusion. It needs to explain how your findings affect the context and whether your hypothesis was correct. Include the primary take-home message, additional findings of importance, and perspective. Also explain whether there is scope for further research into the subject of your report.

Your conclusion should be honest and give the reader the ultimate message that your research shows. Readers trust the conclusion, so make sure you’re not fabricating the results of your research. Some readers won’t read your entire paper, but this section will tell them if it’s worth them referencing it in their own study.

4. How to Start an Abstract

The first line of your abstract should give your reader the context of your report by providing background information. You can use this sentence to imply the motivation for your research.

You don’t need to use a hook phrase or device in your first sentence to grab the reader’s attention. Your reader will look to establish relevance quickly, so readability and clarity are more important than trying to persuade the reader to read on.

5. How to Format an Abstract

Most abstracts use the same formatting rules, which help the reader identify the abstract so they know where to look for it.

Here’s a list of formatting guidelines for writing an abstract:

Stick to one paragraph

Use block formatting with no indentation at the beginning

Put your abstract straight after the title and acknowledgements pages

Use present or past tense, not future tense

There are two primary types of abstract you could write for your paper—descriptive and informative.

An informative abstract is the most common, and they follow the structure mentioned previously. They are longer than descriptive abstracts because they cover more details.

Descriptive abstracts differ from informative abstracts, as they don’t include as much discussion or detail. The word count for a descriptive abstract is between 50 and 150 words.

Here is an example of an informative abstract:

A growing trend exists for authors to employ a more informal writing style that uses “we” in academic writing to acknowledge one’s stance and engagement. However, few studies have compared the ways in which the first-person pronoun “we” is used in the abstracts and conclusions of empirical papers. To address this lacuna in the literature, this study conducted a systematic corpus analysis of the use of “we” in the abstracts and conclusions of 400 articles collected from eight leading electrical and electronic (EE) engineering journals. The abstracts and conclusions were extracted to form two subcorpora, and an integrated framework was applied to analyze and seek to explain how we-clusters and we-collocations were employed. Results revealed whether authors’ use of first-person pronouns partially depends on a journal policy. The trend of using “we” showed that a yearly increase occurred in the frequency of “we” in EE journal papers, as well as the existence of three “we-use” types in the article conclusions and abstracts: exclusive, inclusive, and ambiguous. Other possible “we-use” alternatives such as “I” and other personal pronouns were used very rarely—if at all—in either section. These findings also suggest that the present tense was used more in article abstracts, but the present perfect tense was the most preferred tense in article conclusions. Both research and pedagogical implications are proffered and critically discussed.

Wang, S., Tseng, W.-T., & Johanson, R. (2021). To We or Not to We: Corpus-Based Research on First-Person Pronoun Use in Abstracts and Conclusions. SAGE Open, 11(2).

Here is an example of a descriptive abstract:

From the 1850s to the present, considerable criminological attention has focused on the development of theoretically-significant systems for classifying crime. This article reviews and attempts to evaluate a number of these efforts, and we conclude that further work on this basic task is needed. The latter part of the article explicates a conceptual foundation for a crime pattern classification system, and offers a preliminary taxonomy of crime.

Farr, K. A., & Gibbons, D. C. (1990). Observations on the Development of Crime Categories. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 34(3), 223–237.

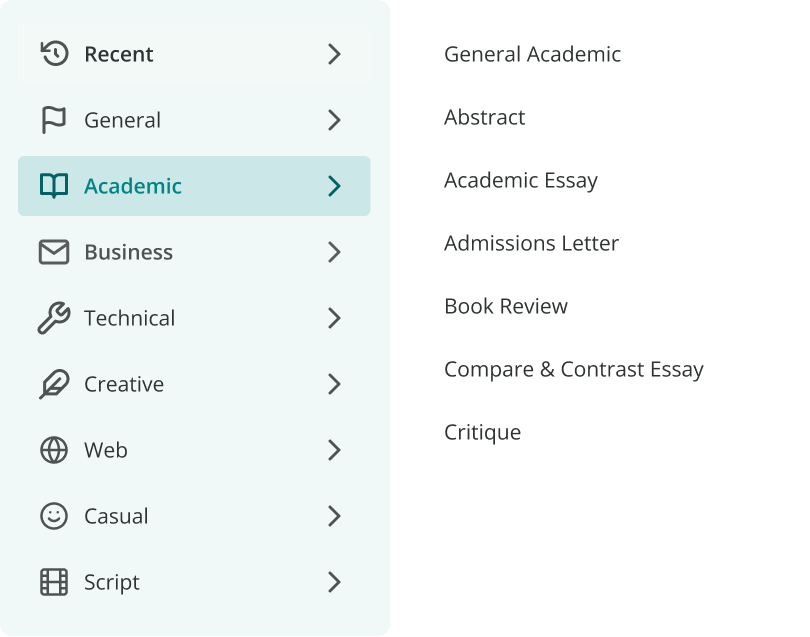

If you want to ensure your abstract is grammatically correct and easy to read, you can use ProWritingAid to edit it. The software integrates with Microsoft Word, Google Docs, and most web browsers, so you can make the most of it wherever you’re writing your paper.

Before you edit with ProWritingAid, make sure the suggestions you are seeing are relevant for your document by changing the document type to “Abstract” within the Academic writing style section.

You can use the Readability report to check your abstract for places to improve the clarity of your writing. Some suggestions might show you where to remove words, which is great if you’re over your word count.

We hope the five steps and examples we’ve provided help you write a great abstract for your research paper.

Get started with ProWritingAid

Drop us a line or let's stay in touch via :

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Dissertation

- How to Write an Abstract | Steps & Examples

How to Write an Abstract | Steps & Examples

Published on 1 March 2019 by Shona McCombes . Revised on 10 October 2022 by Eoghan Ryan.

An abstract is a short summary of a longer work (such as a dissertation or research paper ). The abstract concisely reports the aims and outcomes of your research, so that readers know exactly what your paper is about.

Although the structure may vary slightly depending on your discipline, your abstract should describe the purpose of your work, the methods you’ve used, and the conclusions you’ve drawn.

One common way to structure your abstract is to use the IMRaD structure. This stands for:

- Introduction

Abstracts are usually around 100–300 words, but there’s often a strict word limit, so make sure to check the relevant requirements.

In a dissertation or thesis , include the abstract on a separate page, after the title page and acknowledgements but before the table of contents .

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Be assured that you'll submit flawless writing. Upload your document to correct all your mistakes.

Table of contents

Abstract example, when to write an abstract, step 1: introduction, step 2: methods, step 3: results, step 4: discussion, tips for writing an abstract, frequently asked questions about abstracts.

Hover over the different parts of the abstract to see how it is constructed.

This paper examines the role of silent movies as a mode of shared experience in the UK during the early twentieth century. At this time, high immigration rates resulted in a significant percentage of non-English-speaking citizens. These immigrants faced numerous economic and social obstacles, including exclusion from public entertainment and modes of discourse (newspapers, theater, radio).

Incorporating evidence from reviews, personal correspondence, and diaries, this study demonstrates that silent films were an affordable and inclusive source of entertainment. It argues for the accessible economic and representational nature of early cinema. These concerns are particularly evident in the low price of admission and in the democratic nature of the actors’ exaggerated gestures, which allowed the plots and action to be easily grasped by a diverse audience despite language barriers.

Keywords: silent movies, immigration, public discourse, entertainment, early cinema, language barriers.

The only proofreading tool specialized in correcting academic writing

The academic proofreading tool has been trained on 1000s of academic texts and by native English editors. Making it the most accurate and reliable proofreading tool for students.

Correct my document today

You will almost always have to include an abstract when:

- Completing a thesis or dissertation

- Submitting a research paper to an academic journal

- Writing a book proposal

- Applying for research grants

It’s easiest to write your abstract last, because it’s a summary of the work you’ve already done. Your abstract should:

- Be a self-contained text, not an excerpt from your paper

- Be fully understandable on its own

- Reflect the structure of your larger work

Start by clearly defining the purpose of your research. What practical or theoretical problem does the research respond to, or what research question did you aim to answer?

You can include some brief context on the social or academic relevance of your topic, but don’t go into detailed background information. If your abstract uses specialised terms that would be unfamiliar to the average academic reader or that have various different meanings, give a concise definition.

After identifying the problem, state the objective of your research. Use verbs like “investigate,” “test,” “analyse,” or “evaluate” to describe exactly what you set out to do.

This part of the abstract can be written in the present or past simple tense but should never refer to the future, as the research is already complete.

- This study will investigate the relationship between coffee consumption and productivity.

- This study investigates the relationship between coffee consumption and productivity.

Next, indicate the research methods that you used to answer your question. This part should be a straightforward description of what you did in one or two sentences. It is usually written in the past simple tense, as it refers to completed actions.

- Structured interviews will be conducted with 25 participants.

- Structured interviews were conducted with 25 participants.

Don’t evaluate validity or obstacles here — the goal is not to give an account of the methodology’s strengths and weaknesses, but to give the reader a quick insight into the overall approach and procedures you used.

Next, summarise the main research results . This part of the abstract can be in the present or past simple tense.

- Our analysis has shown a strong correlation between coffee consumption and productivity.

- Our analysis shows a strong correlation between coffee consumption and productivity.

- Our analysis showed a strong correlation between coffee consumption and productivity.

Depending on how long and complex your research is, you may not be able to include all results here. Try to highlight only the most important findings that will allow the reader to understand your conclusions.

Finally, you should discuss the main conclusions of your research : what is your answer to the problem or question? The reader should finish with a clear understanding of the central point that your research has proved or argued. Conclusions are usually written in the present simple tense.

- We concluded that coffee consumption increases productivity.

- We conclude that coffee consumption increases productivity.

If there are important limitations to your research (for example, related to your sample size or methods), you should mention them briefly in the abstract. This allows the reader to accurately assess the credibility and generalisability of your research.

If your aim was to solve a practical problem, your discussion might include recommendations for implementation. If relevant, you can briefly make suggestions for further research.

If your paper will be published, you might have to add a list of keywords at the end of the abstract. These keywords should reference the most important elements of the research to help potential readers find your paper during their own literature searches.

Be aware that some publication manuals, such as APA Style , have specific formatting requirements for these keywords.

It can be a real challenge to condense your whole work into just a couple of hundred words, but the abstract will be the first (and sometimes only) part that people read, so it’s important to get it right. These strategies can help you get started.

Read other abstracts

The best way to learn the conventions of writing an abstract in your discipline is to read other people’s. You probably already read lots of journal article abstracts while conducting your literature review —try using them as a framework for structure and style.

You can also find lots of dissertation abstract examples in thesis and dissertation databases .

Reverse outline

Not all abstracts will contain precisely the same elements. For longer works, you can write your abstract through a process of reverse outlining.

For each chapter or section, list keywords and draft one to two sentences that summarise the central point or argument. This will give you a framework of your abstract’s structure. Next, revise the sentences to make connections and show how the argument develops.

Write clearly and concisely

A good abstract is short but impactful, so make sure every word counts. Each sentence should clearly communicate one main point.

To keep your abstract or summary short and clear:

- Avoid passive sentences: Passive constructions are often unnecessarily long. You can easily make them shorter and clearer by using the active voice.

- Avoid long sentences: Substitute longer expressions for concise expressions or single words (e.g., “In order to” for “To”).

- Avoid obscure jargon: The abstract should be understandable to readers who are not familiar with your topic.

- Avoid repetition and filler words: Replace nouns with pronouns when possible and eliminate unnecessary words.

- Avoid detailed descriptions: An abstract is not expected to provide detailed definitions, background information, or discussions of other scholars’ work. Instead, include this information in the body of your thesis or paper.

If you’re struggling to edit down to the required length, you can get help from expert editors with Scribbr’s professional proofreading services .

Check your formatting

If you are writing a thesis or dissertation or submitting to a journal, there are often specific formatting requirements for the abstract—make sure to check the guidelines and format your work correctly. For APA research papers you can follow the APA abstract format .

Checklist: Abstract

The word count is within the required length, or a maximum of one page.

The abstract appears after the title page and acknowledgements and before the table of contents .

I have clearly stated my research problem and objectives.

I have briefly described my methodology .

I have summarized the most important results .

I have stated my main conclusions .

I have mentioned any important limitations and recommendations.

The abstract can be understood by someone without prior knowledge of the topic.

You've written a great abstract! Use the other checklists to continue improving your thesis or dissertation.

An abstract is a concise summary of an academic text (such as a journal article or dissertation ). It serves two main purposes:

- To help potential readers determine the relevance of your paper for their own research.

- To communicate your key findings to those who don’t have time to read the whole paper.

Abstracts are often indexed along with keywords on academic databases, so they make your work more easily findable. Since the abstract is the first thing any reader sees, it’s important that it clearly and accurately summarises the contents of your paper.

An abstract for a thesis or dissertation is usually around 150–300 words. There’s often a strict word limit, so make sure to check your university’s requirements.

The abstract is the very last thing you write. You should only write it after your research is complete, so that you can accurately summarize the entirety of your thesis or paper.

Avoid citing sources in your abstract . There are two reasons for this:

- The abstract should focus on your original research, not on the work of others.

- The abstract should be self-contained and fully understandable without reference to other sources.

There are some circumstances where you might need to mention other sources in an abstract: for example, if your research responds directly to another study or focuses on the work of a single theorist. In general, though, don’t include citations unless absolutely necessary.

The abstract appears on its own page, after the title page and acknowledgements but before the table of contents .

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

McCombes, S. (2022, October 10). How to Write an Abstract | Steps & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved 21 May 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/thesis-dissertation/abstract/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, how to write a thesis or dissertation introduction, thesis & dissertation acknowledgements | tips & examples, dissertation title page.

We use cookies and similar technologies to improve your website experience and help us understand how you use our website. By continuing to use this website, you consent to the usage of cookies. Learn more about our Privacy Statement and Cookie Policy .

- Our Mission

- Code of Conduct

- The Consultants

- Hours and Locations

- Apply to Become a Consultant

- Make an Appointment

- Face-to-Face Appointments

- Zoom Appointments

- Written Feedback Appointments

- Support for Writers with Disabilities

- Policies and Restrictions

- Upcoming Workshops

- Class Workshops

- Meet the Consultants

- Writing Guides and Tools

- Schedule an appointment! Login or Register

- Graduate Students

- ESOL Students

Writing an Abstract

What is an abstract.

An abstract is a 150- to 250-word paragraph that provides readers with a quick overview of your essay or report and its organization. It should express your thesis (or central idea) and your key points; it should also suggest any implications or applications of the research you discuss in the paper.

According to Carole Slade, an abstract is “a concise summary of the entire paper.”

The function of an abstract is to describe, not to evaluate or defend, the paper.

The abstract should begin with a brief but precise statement of the problem or issue, followed by a description of the research method and design, the major findings, and the conclusions reached.

The abstract should contain the most important key words referring to method and content: these facilitate access to the abstract by computer search and enable a reader to decide whether to read the entire dissertation.

Note: Your abstract should read like an overview of your paper, not a proposal for what you intended to study or accomplish. Avoid beginning your sentences with phrases like, “This essay will examine...” or “In this research paper I will attempt to prove...”

(The examples above are taken from Form and Style (10th ed.), by Carole Slade; The Scott, Foresman Handbook for Writers (5th ed.); and the Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association (5th ed.).)

Note: The following are specifications for an abstract in APA style, used in the social sciences, such as psychology or anthropology. If you are in another discipline, check with your professor about the format for the abstract.

Writing an Abstract for an IMRaD Paper

Many papers in the social sciences, natural sciences, and engineering sciences follow IMRaD structure: their main sections are entitled Introduction, Methods, Results, and Discussion. People use the abstract to decide whether to read the rest of the paper, so the abstract for such a paper is important.

Because the abstract provides the highlights of the paper, you should draft your abstract after you have written a full draft of the paper. Doing so, you can summarize what you’ve already written in the paper as you compose the abstract.

Typically, an abstract for an IMRaD paper or presentation is one or two paragraphs long (120 – 500 words). Abstracts usually spend

25% of their space on the purpose and importance of the research (Introduction)

25% of their space on what you did (Methods)

35% of their space on what you found (Results)

15% of their space on the implications of the research

Try to avoid these common problems in IMRaD abstracts:

1. The abstract provides a statement of what the paper will ask or explore rather than what it found:

X This report examines the causes of oversleeping. (What did it find out about these causes?) √ Individuals oversleep because they go to bed too late, forget to set their alarms, and keep their rooms dark.

2. The abstract provides general categories rather than specific details in the findings:

X The study draws conclusions about which variables are most important in choosing a movie theater. (What, specifically, are these variables?)

√ The study concludes that the most important variables in choosing a movie theater are comfortable seats and high-quality popcorn.

The Writing Center

4400 University Drive, 2G8 Fairfax, VA 22030

- Johnson Center, Room 227E

- +1-703-993-1200

- [email protected]

Quick Links

- Register with us

© Copyright 2024 George Mason University . All Rights Reserved. Privacy Statement | Accessibility

- Privacy Policy

Home » Research Paper Abstract – Writing Guide and Examples

Research Paper Abstract – Writing Guide and Examples

Table of Contents

Research Paper Abstract

Research Paper Abstract is a brief summary of a research pape r that describes the study’s purpose, methods, findings, and conclusions . It is often the first section of the paper that readers encounter, and its purpose is to provide a concise and accurate overview of the paper’s content. The typical length of an abstract is usually around 150-250 words, and it should be written in a concise and clear manner.

Research Paper Abstract Structure

The structure of a research paper abstract usually includes the following elements:

- Background or Introduction: Briefly describe the problem or research question that the study addresses.