Feminist Theory

Jo Ann Arinder

Feminist theory falls under the umbrella of critical theory, which in general have the purpose of destabilizing systems of power and oppression. Feminist theory will be discussed here as a theory with a lower case ‘t’, however this is not meant to imply that it is not a Theory or cannot be used as one, only to acknowledge that for some it may be a sub-genre of Critical Theory, while for others it stands alone. According to Egbert and Sanden (2020), some scholars see critical paradigms as extensions of the interpretivist, but there is also an emphasis on oppression and lived experience grounded in subjectivist epistemology.

The purpose of using a feminist lens is to enable the discovery of how people interact within systems and possibly offer solutions to confront and eradicate oppressive systems and structures. Feminist theory considers the lived experience of any person/people, not just women, with an emphasis on oppression. While there may not be a consensus on where feminist theory fits as a theory or paradigm, disruption of oppression is a core tenant of feminist work. As hooks (2000) states, “Simply put, feminism is a movement to end sexism, sexist exploitation and oppression. I liked this definition because it does not imply that men were the enemy” (p. viii).

Previous Studies

Marxism and socialism are key components in the heritage.of feminist theory. The origins of feminist theory can be found in the 18th century with growth in the 1970s’ and 1980s’ equality movements. According to Burton (2014), feminist theory has its roots in Marxism but specifically looks to Engles’ (1884) work as one possible starting point. Burton (2014) notes that, “Origin of the Family and commentaries on it were central texts to the feminist movement in its early years because of the felt need to understand the origins and subsequent development of the subordination of the female sex” (p. 2). Work in feminist theory, including research regarding gender equality, is ongoing.

Gender equality continues to be an issue today, and research into gender equality in education is still moving feminist theory forward. For example, Pincock’s (2017) study discusses the impact of repressive norms on the education of girls in Tanzania. The author states that, “…considerations of what empowerment looks like in relation to one’s sexuality are particularly important in relation to schooling for teenage girls as a route to expanding their agency” (p. 909). This consideration can be extended to any oppressed group within an educational setting and is not an area of inquiry relegated to the oppression of only female students. For example, non-binary students face oppression within educational systems and even male students can face barriers, and students are often still led towards what are considered “gender appropriate” studies. This creates a system of oppression that requires active work to disrupt.

Looking at representation in the literature used in education is another area of inquiry in feminist research. For example, Earles (2017) focused on physical educational settings to explore relationships “between gendered literary characters and stories and the normative and marginal responses produced by children” (p. 369). In this research, Earles found evidence to support that a contradiction between the literature and children’s lived experiences exists. The author suggests that educators can help to continue the reduction of oppressive gender norms through careful selection of literature and spaces to allow learners opportunities for appropriate discussions about these inconsistencies.

In another study, Mackie (1999) explored incorporating feminist theory into evaluation research. Mackie was evaluating curriculum created for English language learners that recognized the dual realities of some students, also known as the intersectionality of identity, and concluded that this recognition empowered students. Mackie noted that valuing experience and identity created a potential for change on an individual and community level and “Feminist and other types of critical teaching and research provide needed balance to TESL and applied linguistics” (p. 571).Further, Bierema and Cseh (2003) used a feminist research framework to examine previously ignored structural inequalities that affect the lives of women working in the field of human resources.

Model of Feminist Theory

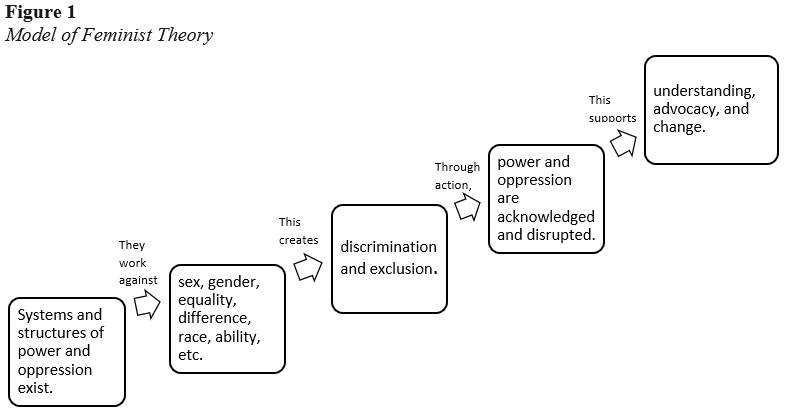

Figure 1 presents a model of feminist theory that begins with the belief that systems exist that oppress and work against individuals. The model then shows that oppression is based on intersecting identities that can create discrimination and exclusion. The model indicates the idea that, through knowledge and action, oppressive systems can be disrupted to support change and understanding.

The core concepts in feminist theory are sex, gender, race, discrimination, equality, difference, and choice. There are systems and structures in place that work against individuals based on these qualities and against equality and equity. Research in critical paradigms requires the belief that, through the exploration of these existing conditions in the current social order, truths can be revealed. More important, however, this exploration can simultaneously build awareness of oppressive systems and create spaces for diverse voices to speak for themselves (Egbert & Sanden, 2019).

Constructs

Feminism is concerned with the constructs of intersectionality, dimensions of social life, social inequality, and social transformation. Through feminist research, lasting contributions have been made to understanding the complexities and changes in the gendered division of labor. Men and women should be politically, economically, and socially equal and this theory does not subscribe to differences or similarities between men, nor does it refer to excluding men or only furthering women’s causes. Feminist theory works to support change and understanding through acknowledging and disrupting power and oppression.

Proposition

Feminist theory proposes that when power and oppression are acknowledged and disrupted, understanding, advocacy, and change can occur.

Using the Model

There are many potential ways to utilize this model in research and practice. First, teachers and students can consider what systems of power exist in their classroom, school, or district. They can question how these systems are working to create discrimination and exclusion. By considering existing social structures, they can acknowledge barriers and issues inherit to the system. Once these issues are acknowledged, they can be disrupted so that change and understanding can begin. This may manifest, for example, as considering how past colonialism has oppressed learners of English as a second or foreign language.

The use of feminist theory in the classroom can ensure that the classroom is created, in advance, to consider barriers to learning faced by learners due to sex, gender, difference, race, or ability. This can help to reduce oppression created by systemic issues. In the case of the English language classroom, learners may be facing oppression based on their native language or country of origin. Facing these barriers in and out of the classroom can affect learners’ access to education. Considering these barriers in planning and including efforts to mitigate the issues and barriers faced by learners is a use of feminist theory.

Feminist research is interested in disrupting systems of oppression or barriers created from these systems with a goal of creating change. All research can include feminist theory when the research adds to efforts to work against and advocate to eliminate the power and oppression that exists within systems or structures that, in particular, oppress women. An examination of education in general could be useful since education is a field typically dominated by women; however, women are not often in leadership roles in the field. In the same way, using feminist theory for an examination into the lack of people of color and male teachers represented in education might also be useful. Action research is another area that can use feminist theory. Action research is often conducted in the pursuit of establishing changes that are discovered during a project. Feminism and action research are both concerned with creating change, which makes them a natural pairing.

Pre-existing beliefs about what feminism means can make including it in classroom practice or research challenging. Understanding that feminism is about reducing oppression for everyone and sharing that definition can reduce this challenge. hooks (2000) said that, “A male who has divested of male privilege, who has embraced feminist politics, is a worthy comrade in struggle, in no way a threat to feminism, whereas a female who remains wedded to sexist thinking and behavior infiltrating feminist movement is a dangerous threat”(p. 12). As Angela Davis noted during a speech at Western Washington University in 2017, “Everything is a feminist issue.” Feminist theory is about questioning existing structures and whether they are creating barriers for anyone. An interest in the reduction of barriers is feminist. Anyone can believe in the need to eliminate oppression and work as teachers or researchers to actively to disrupt systems of oppression.

Bierema, L. L., & Cseh, M. (2003). Evaluating AHRD research using a feminist research framework. Human Resource Development Quarterly , 14 (1), 5–26.

Burton, C. (2014). Subordination: Feminism and social theory . Routledge.

Earles, J. (2017). Reading gender: A feminist, queer approach to children’s literature and children’s discursive agency. Gender and Education, 29 (3), 369–388.

Egbert, J., & Sanden, S. (2019). Foundations of education research: Understanding theoretical components . Taylor & Francis.

Hooks, B. (2000). Feminism is for everybody: Passionate politics . South End Press.

Mackie, A. (1999). Possibilities for feminism in ESL education and research. TESOL Quarterly, 33 (3), 566-573.

Pincock, K. (2018). School, sexuality and problematic girlhoods: Reframing ‘empowerment’ discourse. Third World Quarterly, 39 (5), 906-919.

Share This Book

- Increase Font Size

- Tools and Resources

- Customer Services

- African Literatures

- Asian Literatures

- British and Irish Literatures

- Latin American and Caribbean Literatures

- North American Literatures

- Oceanic Literatures

- Slavic and Eastern European Literatures

- West Asian Literatures, including Middle East

- Western European Literatures

- Ancient Literatures (before 500)

- Middle Ages and Renaissance (500-1600)

- Enlightenment and Early Modern (1600-1800)

- 19th Century (1800-1900)

- 20th and 21st Century (1900-present)

- Children’s Literature

- Cultural Studies

- Film, TV, and Media

- Literary Theory

- Non-Fiction and Life Writing

- Print Culture and Digital Humanities

- Theater and Drama

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Article contents

Feminist theory.

- Pelagia Goulimari Pelagia Goulimari Department of English, University of Oxford

- https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190201098.013.976

- Published online: 19 November 2020

Feminist theory in the 21st century is an enormously diverse field. Mapping its genealogy of multiple intersecting traditions offers a toolkit for 21st-century feminist literary criticism, indeed for literary criticism tout court. Feminist phenomenologists (Simone de Beauvoir, Iris Marion Young, Toril Moi, Miranda Fricker, Pamela Sue Anderson, Sara Ahmed, Alia Al-Saji) have contributed concepts and analyses of situation, lived experience, embodiment, and orientation. African American feminists (Toni Morrison, Audre Lorde, Alice Walker, Hortense J. Spillers, Saidiya V. Hartman) have theorized race, intersectionality, and heterogeneity, particularly differences among women and among black women. Postcolonial feminists (Assia Djebar, Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, Chandra Talpade Mohanty, Florence Stratton, Saba Mahmood, Jasbir K. Puar) have focused on the subaltern, specificity, and agency. Queer and transgender feminists (Judith Butler, Jack Halberstam, Susan Stryker) have theorized performativity, resignification, continuous transition, and self-identification. Questions of representation have been central to all traditions of feminist theory.

- continuous transition

- heterogeneity

- intersectionality

- lived experience

- performativity

- resignification

- self-identification

- the subaltern

Mapping 21st-Century Feminist Theory

Feminist theory is a vast, enormously diverse, interdisciplinary field that cuts across the humanities, sciences, and social sciences. As a result, this article cannot offer a historical overview or even an exhaustive account of 21st-century feminist theory. But it offers a genealogy and a toolkit for 21st-century feminist criticism. 1 The aim of this article is to outline the questions and issues 21st-century feminist theorists have been addressing; the concepts, figures, and narratives they have been honing; and the practices they have been experimenting with—some inherited, others new. This account of feminist theory will include African American, postcolonial, and Islamic feminists as well as queer and transgender theorists and writers who identify as feminists. While these fields are distinct and while they need to reckon with their respective Eurocentrism, racism, misogyny, queerphobia, or transphobia, this article will focus on their mutual allyship, in spite of continuing tensions. Particularly troubling are feminists who define themselves against queer and transgender theory and activism; by way of response, this article will be highlighting feminist queer theory and transfeminism.

On the one hand, literary criticism is not high on the agenda of many 21st-century feminist theorists. This means that literary critics need to imaginatively transpose feminist concepts to literature. On the other hand, a lot of feminist theorists practice literature; they write in an experimental way that combines academic work, creative writing, and life-writing; they combine narrative and figurative language with concepts and arguments. Contemporary feminist theory offers a powerful mix of experimental writing, big issues, quirky personal accounts, and utopian thinking of a new kind.

Feminists have been combining theory, criticism, and literature; Mary Wollstonecraft, Simone de Beauvoir, Toni Morrison, Audre Lorde, Hélène Cixous, and Alice Walker have written across these genres. In African Sexualities: A Reader ( 2011 ), Sylvia Tamale’s decision to place academic scholarship side by side with poems, fiction, life-writing, political declarations, and reports is supported by feminist traditions. 2 Furthermore, the border between feminist theory, literature, and life-writing has been increasingly permeable in the 21st century , hence the centrality of texts in hybrid genres: theory with literary and life-writing elements, literature with meta-literary elements, and so on. Early 21st-century terms such as autofiction and autotheory register the prevalence of the tendency. This is at least partly a question of addressing different audiences—aiming for public engagement and connection with activism outside universities and bypassing the technical jargon of academic feminist theory. Another reason is that feminist theorists, especially those from marginalized groups, have found some of the conventions of academic scholarship objectionable or false—for example, the assumption of a universal, disembodied, or unsituated perspective.

Nevertheless, recent feminist experiments with genre—for example, by Anne Carson, Paul B. Preciado, Maggie Nelson, or Alison Bechdel—nod toward an integral part of women’s writing and feminist writing. 3 Historic experiments in mixed genre, going back to Elizabeth Barrett-Browning’s poem-novel Aurora Leigh , include: Virginia Woolf’s critical-theoretical-fictional A Room of One’s Own ; Julia Kristeva’s poetico-theoretical “Stabat Mater”; Marge Piercy’s Woman on the Edge of Time , oscillating between speculative science fiction and naturalist novel; Audre Lorde’s “biomythography,” Zami ; the mix of theory, fiction, and life-writing in Leslie Feinberg’s Stone Butch Blues and Chris Kraus’ I Love Dick ; or Qurratulain Hyder’s Fireflies in the Mist , hovering between historical fiction and romance. 4

Twenty-first-century feminist theory also tends to be thematically expansive and more than feminist theory narrowly understood, in that it is not only about “women” (those assigned female at birth or socially counted as women or self-identifying as women). It is a mature field that addresses structural injustice, social justice, and the future of the planet. As a result, cross-fertilization with other academic fields abounds. Relatively new academic fields such as feminist theory, postcolonial theory, and critical race theory—emerging since the 1960s, established in the 1980s, and having initially to cement their distinctiveness and place within the academy—have been increasingly coming together and cross-fertilizing in the 21st century . Distinct feminist perspectives (phenomenological, poststructuralist, African American intersectional, postcolonial, Islamic, queer, transgender) have also been coming together and variously informing 21st-century feminist theory. While this article will introduce these perspectives, it will aim to show that feminist theorists are increasingly difficult to put in a box, and this is a good thing.

Feminist Phenomenology (Beauvoir, Young, Moi, Fricker, Anderson, Ahmed, Al-Saji): Situation, Lived Experience, Embodiment, Orientation

Simone de Beauvoir initiates feminist phenomenology, her existentialism emerging within the broader tradition of phenomenology. While the present account of feminist theory begins with Beauvoir, it is important to acknowledge the continuing influence of older feminists and proto-feminists, as “feminism” only acquired its current ( 20th- and 21st-century ) meaning in the late 19th century , according to the Oxford English Dictionary. See, for example, Christine de Pizan, “Jane Anger,” Margaret Cavendish, Aphra Behn, Mary Astell, Anne Finch, Mary Wollstonecraft, Mary Hays, Sojourner Truth, Harriet Jacobs, Emily Davies, Millicent Garrett Fawcett, Rokeya Sakhawat Hossain, and Virginia Woolf.

All contemporary feminist theory has been influenced by Beauvoir, in some respect or other. Her famous claim that “One is not born, but rather becomes, woman,” opening volume 2 of The Second Sex ( 1949 ), points to the asymmetrical socialization of men and women. 5 In her philosophical terms, man is the One, the universal, subject, freedom, transcendence, mind, spirit, culture; woman is the Other, the particular, object, situation, immanence, body, flesh, nature. Patriarchy for Beauvoir is a system of binary oppositions, whose terms are mutually exclusive: the One/the Other, the universal/the particular, subject/object, freedom/situation, transcendence/immanence, mind/body, spirit/flesh, culture/nature. Men have been socialized to aim for—indeed to become—the valued terms in each binary opposition (the One, the universal, subject, freedom, transcendence, mind, spirit, culture); while the undesirable terms (the Other, the particular, object, situation, immanence, body, flesh, nature) are projected onto women, who are socialized to become those terms—to become object, for example. Emerging from this system is the illusion of a transhistorical feminine essence or a norm of femininity that misconstrues, disciplines, and oppresses actual, historical women. Women for Beauvoir are an oppressed group, and her aim is their liberation. 6

Beauvoir critiques the social aims and myths of patriarchy, pointing to the pervasiveness of patriarchal myths in philosophy, literature, and culture. But she also critiques the very forms of patriarchy—binary opposition, dualistic thinking, essentialism, universalism, abstraction—while not completely able to free her own analysis from them. Instead of them, Beauvoir advocates attention to concrete situation and close phenomenological description; indeed The Second Sex abounds in vivid and richly detailed descriptions of early 20th-century French women’s lives. Such close attention and description allow her to demonstrate that all humans are, potentially, both subject and object, free and situated, transcendent and immanent, spirit and flesh, hence the ambiguity of the human condition. 7

The philosophy of existentialism and the broader philosophical movement of phenomenology, within which Beauvoir situates her work, claim to offer radical aims and methods. Phenomenology (Edmund Husserl, Martin Heidegger, Maurice Merleau-Ponty, Jean-Paul Sartre, Beauvoir, Frantz Fanon) is committed to the phenomenological description of the particular in order to avoid the abstractions of scientism. It aims to avoid traditional philosophical dualisms such as mind/body. It re-describes human beings not as disembodied minds but as intentional beings engaged with the world, being-in-the-world (Heidegger’s term), situated in a particular time and place; as lived bodies that are centers of perception, action, and lived experience rather than mere objects; and as being-with and being-for others in inter-subjective relationships rather than just subject/object relationships. Human beings immerse themselves in their projects, using the world and their own bodies—with all their acquired skills, competencies, and sedimented habits—as instruments. While these instruments are indispensable to their projects, they are usually unperceived and remain in the background. They are the background against which objects of perception and action objectives come into view. And yet what is backgrounded can always come to the foreground, suddenly and rudely—when the world resists one, when a blunt knife does not cut the bread, when one’s body is in pain or sick and intrudes, interrupting one’s vision and plans. 8

Without minimizing the novelty of Beauvoir’s theorization of patriarchy, the present quick sketch of phenomenology ought to have highlighted its suitability for feminist appropriations. Nevertheless, Sartre, Beauvoir’s closest collaborator, for example, continues to think that one is distinctively human only to the extent that they transcend their situation. This arguably universalizes Sartre’s particular situation as a member of a privileged group determined to be free, while effectively blaming the situation of oppressed groups on their members, blaming the victims for lacking humanity. 9 By contrast, Beauvoir sheds light on women’s social situation and lived experience: men have “far more concrete opportunities” to be effective; women experience the world not as tools for their projects but as resistance to them; their “energy” is “thrown into the world” but “fails to grasp any object”; a woman’s body is not the “pure instrument of her grasp on the world” but painfully objectified and foregrounded. 10 Beauvoir goes on to distinguish between a variety of unequal social situations with different degrees of freedom inherent in them. Yes, on the whole, French men are freer, less constrained than French women. But Beauvoir discusses the “concrete situation” of other groups “kept in a situation of inferiority”—workers, the colonized, African American slaves, her contemporary African Americans, Jews—while explicitly acknowledging that women themselves are socially divided by class and race. 11

Beauvoir outlines impediments to women’s collective and individual liberation and sketches out paths to collective action and to the “independent woman” of the future, placing literature center stage. She claims that women lack the “concrete means” to organize themselves “in opposition” to patriarchy, in that they lack a shared collective space, such as the factory and the racially segregated community for working-class and black struggles, instead living dispersed private lives. 12 While white middle-class women “are in solidarity” with men of their class and race, rather than with working-class and black women, Beauvoir calls for solidarity among women across class and race boundaries. 13 She addresses white middle-class women like herself, who benefit materially from their connection to white middle-class men, asking them to abandon these benefits for the precarious pursuit of women’s solidarity and freedom. To the extent that women lack freedom by virtue of their social situation qua women, they need to claim their freedom in collective “revolt.” 14 Beauvoir’s 1949 call to organized political action was “the movement before the movement,” according to Michèle Le Doeuff. 15

However, Beauvoir also advocates writing literature as a means of liberation for women and considers all her writing—philosophical, literary, life-writing—a form of activism. Beauvoir devotes considerable space to literary criticism throughout The Second Sex . She shows how writers have reproduced patriarchal myths, often unwittingly. 16 But her future-oriented, crucial chapter “The Independent Woman” centers on a discussion of women writers and even addresses women writers. Having sketched out a history of women’s writing, she turns to young writers to offer advice, based on her analysis of women’s “situation.” 17 To overcome women’s socially imposed apprenticeship in “reasonable modesty,” they need to undertake a counter-practice of “abandonment and transcendence,” “pride” and boldness; they need to become “women insurgents” who feel “responsible for the universe.” 18 Her call, “The free woman is just being born” energizes new women writers to live and write freely—and has been answered by many. 19 But this is not triumphalist empty rhetoric; women writers also need to understand the “ambiguity” of the human condition and of truth itself. 20

Iris Marion Young returns to Beauvoir’s description of women’s social situation and lived experience in “Throwing Like a Girl: A Phenomenology of Feminine Body Comportment, Motility, and Spatiality” ( 1980 ). Young takes Beauvoir’s description as the starting point for her own phenomenology of women’s project-oriented bodily movement in “contemporary advanced industrial, urban, and commercial society,” arguing that their movement is inhibited, ambiguous, discontinuous, and ineffective. 21 Women exhibit a form of socially induced dyspraxia. Young contends that women’s movement “exhibits an ambiguous transcendence, an inhibited intentionality, and a discontinuous unity with its surroundings.” 22 Young turns to women’s bodies in their “orientation toward and action upon and within” their surroundings, particularly the “confrontation of the body’s capacities and possibilities with the resistance and malleability of things” when the body “aims to accomplish a definite purpose or task.” 23 It will be remembered that the phenomenological tradition theorizes the human body as a lived body that is the locus of subjectivity, perception, and action, a capable body extending itself into the world rather than a thing; this is especially the case with Merleau-Ponty. Young’s description of the deviation of women’s bodily experience from this norm is a powerful indictment of women’s social situation.

Firstly, Young identifies that women experience their bodies as ambiguously transcendent: both as a “capacity” and as a “ thing ”; both striving to act upon the world and a “burden.” 24 Secondly, they experience an inhibited intentionality: while acting, they hesitate, their “hesitancy” resulting in “wasted motion . . . from the effort of testing and reorientation.” 25 Thirdly, they experience their bodies as discontinuous with the world: rather than extending themselves and acting upon their surroundings, which is the norm, they live their bodies as objects “ positioned in space.” 26 Or rather, the “space that belongs to her and is available to her grasp and manipulation” is experienced as “constricted,” while “the space beyond is not available to her.” 27 In other words, she experiences her surroundings not as at-hand and within-reach for her projects but as out-of-reach. This discontinuity between “aim and capacity to realize” it is the secret of women’s “tentativeness and uncertainty.” 28 Even more ominously, they live the “ever-present possibility” of becoming the “object of another subject’s . . . manipulations.” 29 In the very exercise of bodily freedom—for example, in opening up the “body in free, active, open extension and bold outward-directedness”—women risk “objectification,” Young argues. 30

Young describes the situation of women as one in which they have to learn “actively to hamper” their “movements.” 31 If this has been the norm of genderization in modern Western urban societies, is it still at work and is it lived differently depending on one’s class, race, sexuality, and so on? 32 Similarly with Beauvoir’s theorization of the situation of women: does it continue to be relevant and useful?

The emergence of “sexual difference” feminism or écriture féminine in France in the mid-1970s, with landmark publications by Luce Irigaray and Hélène Cixous, brought with it a critique of Beauvoir. 33 In view of the present discussion of Beauvoir, one might argue that Beauvoir’s aim is the abolition of gender. Her horizon is the abolition of gender binarism and an end to the oppression of women. However, in “Equal or Different?” ( 1986 ) Irigaray reads this as a pursuit of equality through women’s adoption of male norms, at a great cost, that of “suppress[ing] sexual difference.” 34 In Irigaray’s eyes, Beauvoir’s work is assimilationist, while her own work is radical—it aims to redefine femininity in positive terms. Irigaray insists on the political autonomy of women’s struggles from other liberation movements and, controversially, the priority of feminism over other movements because of the priority of gender over class, race, and so on. Gender is “the primary and irreducible division.” 35

In 1994 feminist literary critic Toril Moi compares Beauvoir to Irigaray and Frantz Fanon, one of the founders of postcolonial theory. Like Fanon who redefined blackness positively and viewed anticolonial struggles as autonomous, Irigaray aims to redefine femininity and mobilize it autonomously, while Beauvoir failed to “grasp the progressive potential of ‘femininity’ as a political discourse” and also “vastly underestimated the potential political impact of an independent woman’s movement.” 36 However, Moi sides with Beauvoir against Irigaray and other “sexual difference” feminists, when comparing their aims. Beauvoir’s ultimate aim is the disappearance of gender, while difference feminists “focus on women’s difference, often without regard for other social movements,” claiming that “women’s interests are best served by the establishment of an enduring regime of sexual difference.” 37

Aiming toward the disappearance of gender does not mean blinding oneself to the situation and lived experience of women. In a 2009 piece on women writers, literature, and feminist theory, Moi turns to Beauvoir to analyze the social situation of women writers. Importantly, Beauvoir focuses on what happens “ once somebody has been taken to be a woman ”—the woman in question might or might not be assigned female at birth and might or might not identify as a woman. 38 While the body of someone taken to be a man is viewed as a “direct and normal connection with the world” that he “apprehends objectively,” the body of someone taken to be a woman is viewed as “weighed down by everything specific to it: an obstacle, a prison.” 39 Concomitantly, male writers and their perspectives and concerns are associated with universality—women writers associated with biased particularity. But if women writers adopt male perspectives and concerns to lay claim to universality, they are alienated from their own lived experience. This is how a “sexist (or racist) society” forces “women and blacks, and other raced minorities, to ‘eliminate’ their gendered (or raced) subjectivity” and “masquerade as some kind of generic universal human being, in ways that devalue their actual experiences as embodied human beings in the world.” 40 All too often women writers have declared “I am not a woman writer,” but this has to be understood as a “ defensive speech act”: a “ response ” to those who have tried to use her gender “against her.” 41

In 2001 feminist philosopher and Beauvoir scholar Michèle Le Doeuff announces a renaissance in Beauvoir studies, in her keynote for the Ninth International Simone de Beauvoir Conference: “It is no longer possible to claim, in the light of a certain New French Feminism, that Beauvoir is obsolete.” 42 She prioritizes the need for scholarship on the conflicts between Sartre and Beauvoir, with a view to making the case for Beauvoir’s originality as a philosopher, in spite of Beauvoir’s self-identification as a writer and reluctance to clash with Sartre philosophically.

Feminist philosopher Miranda Fricker returns more than once to the question of whether Beauvoir is a philosopher or a writer. In 2003 Fricker locates Beauvoir’s originality in her understanding of ambiguity and argues that life-writing has been the medium most suited to her thought, focusing on Beauvoir’s The Prime of Life ( La Force de l’age , 1960 ). 43 Beauvoir found in the institution of philosophy, as she experienced it, a pathological, obsessional attitude—a demand for abstract theorizing that divorces thinkers from their situation to lend their thought universal applicability. This imperious, sovereign role was seriously at odds with Beauvoir’s sense of reality, history, and the self. For Beauvoir, reality is “full of ambiguities, baffling, and impenetrable” and history a violent shock to the self: “History burst over me, and I dissolved into fragments . . . scattered over the four quarters of the globe, linked by every nerve in me to each and every other individual.” 44 Beauvoir uses narrative, particularly life-writing, to connect with her past selves but also to appeal to the reader: “self-knowledge is impossible, and the best one can hope for is self-revelation” to the reader. 45 Fricker claims that Beauvoir primarily addresses female readers; and Beauvoir’s alliance-building with her readers—her “feminist commitment to female solidarity”—promises to bring out, through the reader, “the ‘unity’ to that ‘scattered, broken’ object that is her life.” 46

An example of the role of the reader is Fricker’s 2007 reading of Beauvoir’s under-written account of an early epistemic clash with Sartre. 47 Beauvoir’s first-person narrative voice doesn’t quite say that Sartre undermined her as a knower, but Fricker interprets this incident as an epistemic attack by Sartre that Beauvoir had the resilience to survive, and which contributed to her self-identification as a writer rather than a philosopher. Here the violence of history and the institution of philosophy take very concrete, embodied, intimate form. But the incident also serves as a springboard for Fricker’s concept of epistemic injustice and its two forms: testimonial injustice, and hermeneutical injustice and lacunas. For Fricker, Sartre in this instance does Beauvoir a “testimonial injustice” in that he erodes her confidence and her credibility as a knower. 48 This process might also be “ongoing” and involve “persistent petty intellectual underminings.” 49 Hermeneutical (or interpretive) injustice, on the other hand, has to do with a gap in collective interpretative resources, where a name should be to describe a social experience. 50 For example, the relatively recent term “sexual harassment” has described a social experience where previously there was a hermeneutic lacuna, according to Fricker. Such lacunas are often due to the systemic epistemic marginalization of some groups, and any progress (for example, in adopting a proposed new term) is contingent upon a “virtuous hearer” who will try to listen without prejudice but also requires systemic change. 51 In George Eliot’s Mill on the Floss Maggie Tulliver suffers both testimonial and hermeneutical injustice. 52

This article will now turn to feminist phenomenology within queer theory and critical race theory. Sara Ahmed, in Queer Phenomenology ( 2006 ), offers not a phenomenology of queerness but rather a phenomenological account of heteronormativity as well as a feminist queer critique of phenomenology. In an important reversal of perspective, Ahmed denaturalizes being straight—denaturalizes heteronormativity—by asking: how does one become straight? This is not simply a matter of sexual orientation and choice of love-object. Rather heteronormativity is itself “something that we are oriented around, even if it disappears from view”; “bodies become straight by ‘lining up’” with normative “lines that are already given.” 53 Being straight is “an effect of being ‘in line.’” 54 Unlike earlier phenomenologists such as Heidegger, what is usually being backgrounded and thus invisible is a naturalized system that Ahmed hopes to foreground and bring “into view”: heteronormativity. 55 Ahmed thus extends Beauvoir’s and Young’s analyses of the systematic oppression and incapacitation of women, respectively. 56 Ahmed puts Young’s language to use in order to talk about lesbian lives: heteronormativity “puts some things in reach and others out of reach,” in a manner that incapacitates lesbian lives. Ahmed searches for a different form of sociality, “a space in which the lesbian body can extend itself , as a body that gets near other bodies.” 57 Her critique of even the most promising phenomenologists is that in their work “the straight world is already in place” as an invisible background. 58

Ahmed extends her analysis of the production of heteronormativity to the production of whiteness in “A Phenomenology of Whiteness” ( 2007 ), asking: how does one become white? Ahmed thus furthers her critique of phenomenology from within. Phenomenologists such as Husserl and Merleau-Ponty define the body as “successful,” as “‘able’ to extend itself (through objects) in order to act on and in the world,” as a body that “‘can do’ by flowing into space.” 59 However, far from this being a universal experience, it is the experience of a “bodily form of privilege” from which many groups are excluded. 60 Ahmed does not here acknowledge Young’s analysis of women’s socially induced dyspraxia but turns instead to Fanon’s “phenomenology of ‘being stopped.’” 61 Ahmed calls “discomfort” the social experience of being impeded and goes on to outline its critical potential in “bringing what is in the background, what gets over-looked” back into view. 62 More than a negative feeling, discomfort has the exhilarating potential of opening up a whole world that was previously obscured. 63 Ahmed’s subsequent work has focused on institutional critique, especially of universities in their continuing failure to become inclusive, hospitable spaces for certain groups, in spite of their managerial language of diversity. 64

Where Ahmed calls for critical and transformative “discomfort,” Alia Al-Saji calls for a critical and transformative “hesitation” in “A Phenomenology of Hesitation” ( 2014 ). Al-Saji’s concept of hesitation revises the work of Beauvoir and Young and enlarges their focus on gender to include race. Beauvoir’s analysis of patriarchy as a system that projects and naturalizes fixed, oppositional, hierarchical identities is redeployed toward a “race-critical and feminist” project, though Al-Saji does not acknowledge Beauvoir explicitly but credits Fanon’s work. 65 The systematic and “socially pathological othering” of fluid, relational, contextual, contingent differences into rigid, frozen, naturalized hierarchies remains “hidden from view.” 66 Experience, affect, and vision, in their pathological form, are closed and rigid; in their healthy form, they have a “creative and critical potential . . . to hesitate”—they are ambiguous, open, fluid, responsive, receptive, dynamic, changing, improvisational, self-critical. 67 Al-Saji argues that the “paralyzing hesitation” analyzed by Young can be “mined” to extract a critical hesitation, as Young’s own work exemplifies. 68 By contrast, the “normative ‘I can’ – posited as human but in fact correlated to white, male bodies”—rigidly “excludes other ways of seeing and acting”; it is “objectifying – racializing and sexist[,] . . . reifying and othering .” 69 The alternative to both thoughtless action and paralyzing inaction is: “ acting hesitantly ” and responsively. 70

Feminist philosopher Pamela Sue Anderson’s last writings on “vulnerability” build on Michèle Le Doeuff’s critique of unexamined myths and narratives underlying the Western “imaginary.” One values and strives for invulnerability and equates vulnerability with exposure to violence and suffering. One projects vulnerability onto “the vulnerable” to disavow their own vulnerability: “a dark social imaginary continues to stigmatize those needing to be cared for as a drain on an economy, carefully separating ‘the cared for’ from those who are thought to be ‘in control’ of their lives and of the world.” 71 Furthermore, members of privileged groups often exhibit a “wilful ignorance” of systemic forms of social vulnerability and social injustice. 72 But Anderson also outlines “ethical” vulnerability as a capability for a transformative and life-enhancing openness to others and mutual affection—occasioned by ontological vulnerability. Ethical vulnerability is envisaged as a project where reason, critical self-reflexivity, emotion, intuition and imagination, concepts, arguments, myths and narrative all have a role to play, while also needing to be reimagined and rethought.

African American Feminisms (Morrison, Lorde, Walker, Spillers, Hartman): Race, Intersectionality, Differences among Women and among Black Women

African American and postcolonial feminists have struggled to create space for themselves, caught between a predominantly white women’s movement on the one hand, and male-led civil-rights and anticolonial struggles and postcolonial elites on the other hand. They have fought against assumptions that “All the Women Are White, All the Blacks Are Men” and that white women are “saving brown women from brown men.” 73 African American and postcolonial writers and thinkers (from Toni Morrison to Chandra Talpade Mohanty) have hesitated to self-identify with a primarily white movement that, they argued powerfully, effectively excluded them in unthinkingly prioritizing the concerns of white, middle-class women. Some have avoided self-identifying as a feminist, self-identifying as a “black woman writer” instead. Alice Walker invented the term “womanism” to signal black feminism. “Intersectionality” was coined by Kimberlé Williams Crenshaw, Patricia Hill Collins, and other African American feminists to highlight the intersections of gender and race, feminist and antiracist struggles, creating a space between the white women’s movement and the male-led civil-rights movement. 74 Postcolonial feminists (Assia Djebar, Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, Chandra Talpade Mohanty) similarly created a space between Western feminists and male-led anticolonial struggles and postcolonial elites.

African American feminists have been critical of Beauvoir and of the women’s movements of the 1960s. They have been reconstructing oral, written, and activist traditions of black women such as abolitionists Sojourner Truth and Harriet Jacobs, and modernists Zora Neale Hurston and Nella Larsen—all previously neglected and marginalized. 75 These traditions prioritize: collectivism; the need to critique and resist internalized but unlivable white middle-class norms; waywardness or willfulness rather than individualism; differences among women; difference among black women; and friendship and solidarity among black women across their differences. (By contrast, contemporary white American feminist critics such as Elaine Showalter emphasized self-realization and self-actualization. 76 ) African American women writers—rather than literary critics—have led the way, inspired by orators, musicians, and collective oral forms, as critics have acknowledged. 77

Toni Morrison, as a self-identified black woman writer, announces these strategic priorities in her first novel, The Bluest Eye ( 1970 ). 78 In The Bluest Eye she revises Beauvoir’s analysis of patriarchy as a binary opposition—man/woman—that projects onto “woman” what men disown in themselves. She examines a related binary opposition: white, light-skinned, middle-class, beautiful, proper lady vs. dark-skinned, poor, ugly girl (the racialized opposition between angelic and demonic woman). The first novel to focus on black girls, The Bluest Eye shows the systemic propagation and internalization of white norms of beauty and femininity, leading to hierarchical oppositions between black and white girls as well as between black girls (light-skinned middle-class Maureen, solidly working-class Claudia and Frieda, and precariously poor Pecola). The projection, by everyone, of all ugliness onto poor, dark-skinned Pecola, combined with white norms that are impossible for her, lead to Pecola’s madness. Her attempts at existential affirmation are crushed by the judgment of the world. Pecola’s Bildungsroman turns out naturalist tragedy. However, Claudia, the narrator, develops anagnorisis and shares her increasingly complex critique with the readers.

In “What the Black Woman Thinks about Women’s Lib” ( 1971 ) Morrison uses Beauvoir’s language to bring attention both to the situation of African American women and to their traditions of resistance. Reminding readers of two segregation-era signs—“White Ladies” and “Black Women”—she asserts that many black women rejected ladylike behavior and “frequently kicked back . . . [O]ut of the profound desolation of her reality” the black woman “may very well have invented herself.” 79 Black women have been working and heading single-parent households in a hostile world. If ladies are all “softness, helplessness and modesty,” black women have been “tough, capable, independent and immodest.” 80

Audre Lorde explores similar themes. Her poem, “Who Said It Was Simple” ( 1973 ) illustrates the hierarchy between white “ladies,” in their feminist struggle for self-realization, and black “girls” on whose work they rely. Sister Outsider , Lorde’s essays and speeches from 1976 to 1984 , theorizes intersections of race, sexuality, class, and age that are particularly binding and threatening for black lesbian women. 81 White feminists are ignorant of racism and wrongly assume their concerns to be universally shared by all women, thus replicating the patriarchal elevation of men to the universal analyzed by Beauvoir; they need to drop the “pretense to a homogeneity of experience,” educate themselves about black women, read their work, and listen. 82 In “The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House,” delivered during a Beauvoir conference, Lorde argues that Beauvoir’s call to know “the genuine conditions of our lives” must include racism and homophobia. 83 Black men misdirect their anger for the racism they encounter toward black women, who, paid less and more socially devalued, are easy targets. Falsely equating anti-sexist with anti-Black, black men are hostile to black feminists and especially lesbians; so black men’s sexism is different from the sexism of privileged white men analyzed by Beauvoir. 84 Black women have also been hostile toward each other, due to internalized racism and sexism, projected toward the most marginalized among them; identifying with their oppressors, black women suffer a “misnaming” and “distortion” in their understanding of their situation. 85

But Lorde also exalts traditions of black women’s solidarity across their differences. Once differences among women and among black women are properly understood and named, they can be creative and generative. To achieve this, she extols recording, examining, and naming one’s experience, perceptions, and feelings, as a path to clarity, precision, and illumination, leading to concepts and theories but also to empowerment. Anger, unlike hatred, is potentially both full of information and generative. 86 Affect, more broadly, can be a path to understanding, as affect and rationality are not mutually exclusive: “I don’t see feel/think as a dichotomy.” 87 Particularly innovative is Lorde’s theorization of the “erotic.” In contrast to the pornographic, the erotic is a power intrinsically connected to (and cutting across) love, friendship, self-connection, joy, the spiritual, creativity, work, collaboration, and the political—especially among black women. 88 But relations of interdependence and mutuality among women are only possible in a context of non-hierarchical differences among equals and peers, Lorde stresses repeatedly. 89

Alice Walker attends to many of these themes in Color Purple ( 1982 ). 90 In her collection of essays, In Search of Our Mothers’ Gardens: Womanist Prose ( 1983 ), she pays tribute to black women’s traditions of resistance, due to which “womanish” connotes “outrageous, audacious, courageous or willful behavior.” 91 Her term “womanism” honors these collectivist traditions and their commitment to the “survival and wholeness of entire people, male and female.” 92 But she also calls for the reconstruction of a written tradition of forgotten black women writers, resurrecting Zora Neale Hurston from oblivion in “Looking for Zora,” initially published in Ms . magazine in 1975 . 93

In 1979 Sandra Gilbert and Susan Gubar’s The Madwoman in the Attic: The Woman Writer and the Nineteenth-Century Literary Imagination established the enforced privatization and entrapped idleness of 19th-century white middle-class women. 94 In 1987 Hortense J. Spillers powerfully added that this was made possible by the enforced hard labor of black women, as house or field slaves and later as domestic servants who often headed single-parent households. 95 Furthermore, the gender polarization within the white middle-class family was accompanied by the ungendering of African American slaves, who were not allowed to marry and raise their children, and the structural rape of black women. In the late 1980s Crenshaw and Collins formally introduced the concept of intersectionality, though intersectionality-like ideas—that the black woman is the “mule uh de world”—have been a part of black women’s thought for a long time. 96

“Slavery and gender” has been a core topic since the 1980s, with publications such as Orlando Patterson’s Slavery and Social Death ( 1982 ), Toni Morrison’s Beloved ( 1987 ) and Playing in the Dark ( 1992 ), and Saidiya V. Hartman’s Scenes of Subjection ( 1997 ). 97 Hartman’s abiding topic has been a lost history of black girls and women that can only partially be retrieved and that requires new methodologies. Archives and official records are full of gaps, systematically “dissimulate the extreme violence” of slavery, and “disavow the pain” and “deny the sorrow” of slaves. 98 Even while reading them “against the grain,” Hartman underlines the “ impossibility of fully recovering the experience of the enslaved.” 99 In Lose Your Mother ( 2006 ) Hartman’s concept of the “afterlife of slavery” describes the persistence of “devalued” and “imperiled” black lives, racialized violence, “skewed life chances, limited access to health and education, premature death, incarceration, and impoverishment. I, too, am the afterlife of slavery.” 100 In “Venus in Two Acts” ( 2008 ), Hartman defines her method as “critical fabulation”: mixing critical use of archival research, theorization, and multiple speculative narratives, in an experimental writing that acknowledges its own failure and refuses “to fill in the gaps” to “provide closure.” 101 This writing is:

straining against the limits of the archive . . . and . . . enacting the impossibility of representing the lives of the captives precisely through the process of narration . . . [in order] to displace the . . . authorized account, . . . to imagine what might have happened[,] . . . to listen for the mutters and oaths and cries of the commodity[,] . . . to illuminate the contested character of history, narrative, event, and fact, to topple the hierarchy of discourse, and to engulf authorized speech in the clash of voices. 102

In “The Anarchy of Colored Girls Assembled in a Riotous Manner” ( 2018 ) Hartman returns to “critical fabulation” and offers a “speculative history” of Esther Brown, her friends, and their life in Harlem around 1917 . 103 Their experiments in “free love and free motherhood” were criminalized as “Loitering. Riotous and Disorderly. Solicitation. Violation of the Tenement House Law. . . . Vagrancy.” 104 Questions such as “ Is this man your husband? Where is the father of your child ?”—meant to detect the “likelihood” of their “future criminality” and moral depravity—might render them “three years confined at Bedford and . . . entangled with the criminal justice system and under state surveillance for a decade.” 105 In official records, these measures were narrated as rescuing, reforming, and rehabilitating, therapeutic interventions for the benefit of young black women.

Reading such records against the grain, Hartman tells the story of a “ revolution in a minor key ”: of “ too fast girls and surplus women and whores ” as “social visionaries, radical thinkers, and innovators.” 106 Their “wild and wayward” collective experiments, at the beginning of the 20th century , were building on centuries of black women’s “mutual aid societies” conducted “in stealth.” 107 Their aspiration has been “singularity and freedom”—not the “individuality and sovereignty” coveted by white liberal feminists. 108

Hartman’s work emerges out of African American feminist traditions but also out of postcolonial feminists, whose work pays particular attention to impossibility, failure, aporia, and the limits of representing the subaltern, as well as the heterogeneity and specificity of women’s agency.

Postcolonial Feminisms (Djebar, Spivak, Mohanty, Stratton, Mahmood, Puar): The Subaltern, Specificity, Agency

Colonized women had to contend not only with the “imbalances of their relations with their own men but also the baroque and violent array of hierarchical rules and restrictions that structured their new relations with imperial men and women.” 109 Furthermore, they were central to powerful orientalist fantasies that rendered their actual lives invisible. The relation of colonized land to colonizer was figured as that of a nubile, sexually available woman waiting for her lover, as in H. Rider Haggard’s King Solomon’s Mines where the map of the land centers around “Sheba’s Breasts” and “Mouth of treasure cave.” 110 Algerian writer Assia Djebar exposes this colonial fantasy in Fantasia ( 1985 ). 111 The city of Algiers is seen by the arriving colonizers as a virginal bride waiting for her groom to possess her. She is an “Impregnable City” that “sheds her veils,” as if this was “mutual love at first sight” and “the invaders were coming as lovers!” 112 The Victorian patriarchal, hierarchical nuclear family, ruled by a benign and loving husband and father, was key to the colonial “civilizing mission” because it was the perfect metaphor for the relation between colonizer and colonized in colonial ideology. 113 However, in Women of Algiers in Their Apartment ( 1980 ; mirroring the title of Eugène Delacroix’s orientalist paintings) Djebar reminds her readers that women took part in large numbers in the Algerian anticolonial struggle and suffered torture, rape, and loss of life, but that their contribution was marginalized in post-independence narratives, while they were expected to return to a patriarchal mold ostensibly for the good of the new nation. 114 By contrast, Women of Algiers in Their Apartment foregrounds Algerian women’s heterogeneity but also the intergenerational transmission of their socially repressed, traumatic history, which cannot be fully recovered—hence the self-conscious aporia of Djebar’s project.

Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak’s “Can the Subaltern Speak?” ( 1983 , 1988 , 1999 ) is a subtle theorization of what remains outside colonial, anticolonial, postcolonial, neocolonial, and even “liberal multiculturalist” elites and discourses. 115 Spivak’s starting point is the unpresentability of the “subaltern” (those most marginalized and excluded). The subaltern exceeds any representation treating it as a full identity with a fixed meaning. The subaltern is an inaccessible social unconscious that can only be ethically presented in its unpresentability—fleetingly visible in fragments.

Rather than documenting “subaltern” resistance in its “taxonomic” difference from the elite and rather than assuming that political forces are self-conscious and already constituted identities, Spivak assumes that political identities are being constituted through political action. 116 Many subaltern groups are highly articulate about their aims and their relations to elites and other subaltern groups, but Spivak understands the “subaltern” as singular acts of resistance that are “irretrievably heterogeneous” in relation to constituted identities. 117 Rather than asking for the recognition of “subjugated” and previously “disqualified” forms of knowledge, Spivak is intent on acknowledging her privileged positionality and insists that what she calls the “subaltern” is irretrievably silenced; the “subaltern” is what escapes—or is excluded from—any discourse. 118

Spivak’s heterogeneous subaltern is a (Derridean) singularity that cannot be translated fully or repeated exactly but can only be repeated differently. 119 The singularity in “Can the Subaltern Speak?” is Talu’s suicide, as retold by Spivak. Spivak interprets it as a complex political intervention, by a young middle-class woman activist, that remained illegible as such. Entrusted with a political assassination in the context of the struggle for Indian independence, Spivak claims that Talu’s suicide was a complex refusal to do her mission without betraying the cause. Talu questioned anticolonial nationalism, sati suicide, and female “imprisonment” in heteronormativity, but her “Speech Act was refused” by everyone because it resisted translation into established discourses. 120 Spivak iterates Talu’s singularity differently: as a postcolonial feminist heroine. She does not present her version of Talu’s story as restoring speech to the subaltern. Speech acts are addressed to others and completed by others; they involve “distanced decipherment by another, which is, at best, an interception.” 121 To claim that Talu has finally spoken through Spivak would be a neocolonial “missionary” claim of saving the subaltern. 122 To avoid this, Spivak self-dramatizes her privileged institutional “positionality” and calls for “unlearning” one’s privilege. 123

Postcolonial feminists have been telling the story of the marginalization of women of color within anticolonial movements, postcolonial states, and within Western feminist movements. In “Three Women’sTexts and a Critique of Imperialism” ( 1985 ), Spivak argues that Gilbert and Gubar, in their reading of Jane Eyre in Madwoman in the Attic , unwittingly reproduce the “axioms of imperialism.” 124 For Spivak, in Jane Eyre Bertha, a dark colonial woman, sets the house on fire and kills herself so that Jane Eyre “can become the feminist individualist heroine of British fiction”; she is “sacrificed as an insane animal” for her British “sister’s consolidation” in a manner that is exemplary of the “epistemic violence” of imperialism. 125 Gilbert and Gubar fail to see this and only read Jane and Bertha in individual, “psychological terms.” 126 By contrast, Jean Rhys’s rewriting of Jane Eyre in Wide Sargasso Sea ( 1966 ) makes this visible and enables Spivak’s critique. 127 Rhys allows Bertha to tell her story and keeps Bertha’s “humanity, indeed her sanity as critic of imperialism, intact.” 128 In “Does the Subaltern Speak?” Spivak articulates the value of postcolonial feminism but refuses to defend it as a redemptive breakthrough. Instead she issues a call for self-reflexivity.

Chandra Talpade Mohanty, in “Under Western Eyes” ( 1984 ), calls for studies of local collective struggles and for localized theorizing by investigators. 129 The category of “Third World Woman” is an essentialist fabrication reducing the irreducible “heterogeneity” of women in the Third World. 130 Mohanty’s call for specificity is a rejection of white middle-class feminists’ generalizations on “women” and “Third World women” as neocolonial:

Women are constituted as women through the complex interaction between class, culture, religion and other ideological institutions and frameworks. . . . [R]eductive cross-cultural comparisons result in the colonization of the conflicts and contradictions which characterize women of different social classes and cultures. 131

Mohanty is here remarkably close to African American feminists. What is at stake for Mohanty is for groups of marginalized women to represent themselves and to retrieve forms of agency within their own traditions. As she stresses in Feminism without Borders ( 2003 ): the “application of the notion of women as a homogeneous category to women in the Third World colonizes and appropriates the pluralities” of their complex location and “robs them of their historical and political agency .” 132

Saba Mahmood, in “Feminist Theory, Embodiment, and the Docile Agent: Some Reflections on the Egyptian Islamic Revival” ( 2001 ), argues that rather than reading a specific cultural phenomenon through an established conception of agency, agency should be theorized through the specific phenomenon studied. 133 Her target is the Western feminist equation of feminist agency with secularism, resistance, and transgression, which she finds unhelpful when studying the “urban women’s mosque movement that is part of the larger Islamic revival in Cairo.” 134 While in some contexts feminist agency might take the form of “dramatic transgression and defiance,” for these Egyptian women it took the form of active participation and engagement with a religious movement. 135 It would be a neocolonial gesture to understand their involvement as due to “false consciousness” or internalized patriarchy. 136 Mahmood’s “situated analysis” thus endorses plural, local theories and concepts. 137

Florence Stratton focuses on gender in African postcolonial literature and criticism. She analyses the multiplicity of “ways in which women writers have been written out of the African literary tradition.” 138 They have been ignored by critics, marginalized by definitions of the African canon that universalize the tropes and themes of male writers, and silenced by “gender definitions which . . . maintain the status quo of women’s exclusion from public life.” 139 Particularly pernicious has been the “iteration in African men’s writing of the conventional colonial trope of Africa as female.” 140 Stratton discerns a ubiquitous pattern in African postcolonial men’s writing. Women are cast as symbols of the nation, in sexualized or bodily roles: as nubile virgin to be impregnated or as mother (Stratton calls this the “pot of culture” trope); or, alternatively, as degraded prostitute (the “sweep of history” trope). 141 So women are figured either as embodiments of an ostensibly static traditional culture (trope 1) or as passive victims of historical change (trope 2). This is coupled with a male quest narrative, where the male hero and his vision actively transform prostitute into mother Africa. Underlying this is a patriarchal division of active/passive and subject/object, which denies women as artists and citizens and neglects women’s issues (so actual sex work is totally obscured by its metaphorical role). Stratton goes on to show how African women writers have been “initiators” of “dialogue” with African male writers in order to self-authorize their work and make space for it in the African literary canon. 142 Stratton is also critical of white feminists who read African women writers through their own formal and thematic priorities, oblivious to African feminist traditions. 143

Jasbir K. Puar analyses how the “war on terror” and rising Islamophobia in the West, particularly the United States, have coopted feminist and queer struggles. While colonial orientalist fantasies projected sexual license onto the Middle East, 21st-century orientalist fantasies are “Islamophobic constructions” othering Muslims as “homophobic and perverse,” while constructing the West as “‘tolerant’ but sexually, racially, and gendered normal.” 144 On the one hand, Muslims are presented as “fundamentalist, patriarchal, and, often even homophobic.” 145 On the other hand, a “rhetoric of sexual modernization” turns American queer bodies into “normative patriot bodies.” 146 This involves the loss of an intersectional perspective and the “fissuring of race from sexuality.” 147 Muslims are seen as only marked by race and “presumptively sexually repressed, perverse, or both,” while Western queers are seen as only marked by sexuality and “presumptively white,” male, and “gender normative.” 148

Queer and Transgender Feminisms (Butler, Halberstam, Stryker): Performativity, Resignification, Continuous Transition, Self-Identification

Queer theory emerged in the period from the mid-1980s to the early 1990s, in the midst of the outbreak of HIV/AIDS. 149 Queer theory, as an academic field, can be located at the intersection of poststructuralism (especially the work of Michel Foucault, but also Roland Barthes, Jacques Derrida, and Gilles Deleuze), Francophone feminism from Beauvoir to Irigaray, and African American feminism. Queer theorists have negotiated this genealogy variously; some are predominantly influenced by Foucault, less by feminist thought. The present account will focus on feminist queer theory, especially the work of Judith Butler, and its relation to earlier and subsequent feminist, queer, and transgender thought. As queer theory evolved, postcolonial feminists also became increasingly influential.

In brief, feminist queer theory, while indebted to “sexual difference” feminists such as Irigaray, critiques them through African American feminism. A core theoretical insight of African American feminism is that gender must not be considered on its own or as primary in relation to other social categories and hierarchies. Queer theorists adopt this insight. For queer theorists, sexual orientation is at least as important as gender. Indeed, they contend that what underpins the gender binary (the polarization of two genders) is the institution of “compulsory heterosexuality” or heteronormativity.

Transgender theory emerged in the mid to late 1990s, within the orbit of queer theory but also through its critique. The crux of this critique is that, despite queer theorists’ best intentions, the queer subject is primarily or implicitly white, Western, gender-normative, and cisgender. In attending to sexual orientation, queer theory neglected the spectrum of gender identities and translated issues of gender identification into issues of sexual orientation. Strands of queer activism—for example, figures such as Sylvia Rivera or Stormé DeLarverie in the United States—were marginalized by a politics of respectability led by affluent, white, cisgender queers. 150 This is particularly ironic, given the aspirations invested in the term “queer.”

In queer theory, the term “queer” was intended as an appropriation and resignification of a term of abuse but also as a floating signifier without a fixed meaning or definition and thus open to multiple and changing uses, in keeping with poststructuralist theory. “Queer” has been defined as beyond definition, transgressive, excessive, beyond polar opposites, and exceeding false polarization. So “queer” is both a particular social identity but also exemplary of a potential for openness, fluidity, and transformation in all identities (what poststructuralist theory calls the infinite deferral of the signified). It is important to point out that Spivak defined the “subaltern” and Irigaray the “feminine” in similar terms, also within a poststructuralist frame. A problem with such terms is that, though they are intended to be inclusive, they are exclusive in some of their effects. The chosen term is privileged as the only term that stands for marginality, potential for change, or openness to the past or future. In the process, the privileged term also loses specificity and becomes a metaphor. This is perhaps replicated in some uses of the term “trans” or “trans*,” where once again the term becomes a metaphor for the element of fluidity and openness in all identities.

Retracing one’s steps back to the beginnings of queer theory, while Beauvoir called for equality and the disappearance of gender, “sexual difference” feminists, such as Irigaray and Cixous, called for autonomous women’s struggles and a radical, utopian revisioning of the “feminine” to be performed by their écriture féminine . Judith Butler in Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity ( 1990 ), one of queer theory’s inaugural texts, questions Irigaray’s utopianism and takes as her starting point Beauvoir’s “One is not born, but rather becomes, woman.” 151 Forty years after The Second Sex , Butler contends that societies continue to systematically produce two “discreet and polar genders,” as a prerequisite of heteronormativity; two “[d]iscreet genders are part of what ‘humanizes’ individuals within contemporary society; indeed, we regularly punish those who fail to do their gender right.” 152 One is produced as a recognizably human individual in their very repetition of genderizing practices, performance of gender norms, and iteration of speech acts that bring about gender and its effect of timeless naturalness. But the performativity and iterability of gender show up the “ imitative structure of gender ” and its historical “ contingency .” 153 In spite of the pervasiveness of genderizing practices and the unavailability of a position outside gender, the very performativity and iterability of gender open up the possibility of repeating it slightly differently. Butler hopes for destabilized and constantly resignified genders: “a fluidity of identities,” “an openness to resignification,” and “proliferating gender configurations.” 154 While gender is a normalizing, disciplinary force, it is possible to engage consciously with gender norms and open them to resignification. However, the success or failure of an attempt at resignification also depends on its audience or addressees and the authority they are prepared to attribute to it.

In the context of feminist theory, Butler’s call for continuous resignification takes the form of resignifying “woman” and “feminism” itself. As part of her “radical democratic” feminist politics, she aims to “release” the term “woman” into a “future of multiple significations.” 155 In resignifying feminism, she writes against those feminists who assume that there is an “ontological specificity to women. . . . In the 1980s, the feminist ‘we’ rightly came under attack by women of color who claimed that the ‘we’ was invariably white.” 156 Not only heterogeneity but contentions among feminists ought to be valued: “the rifts among women over the content” of the term “woman” ought to be “safeguarded and prized.” 157 Furthermore, Butler distrusts the utopianism of those feminists who believe they are “beyond the play of power,” asking instead for self-reflexive recognition of feminists’ inevitable embeddedness in power relations. 158

One of the targets of Butler’s critique is Irigaray. Her nuanced reading of Irigaray in Bodies That Matter defends her from accusations of essentialism but rejects the primacy of sexual difference over other forms of difference—race, class, sexual orientation, and so on—in Irigaray’s work. For example, Butler finds that Irigaray’s alternative mythology of two labial lips touching and being touched by each other is a self-conscious textual “rhetorical strategy” intended to counter established understandings of women’s genitals as a lack, a wound, and so on. 159 Rather than describing an essential sexual difference, Irigaray’s reparative, positive figuration of the two lips is a deliberately improper and catachrestic form of mimicry akin to Butler’s resignification; it is “not itself a natural relation, but a symbolic articulation.” 160 Irigaray distinguishes between the false feminine within gender binaries and a true feminine “excluded in and by such a binary opposition” and appearing “only in catachresis .” 161 The true feminine is an “ excessive feminine” in that it “exceeds its figuration”; its essence is to have no essence, to undermine binary oppositions and their essences, and to exceed conceptuality. 162 Irigaray’s textual practice is intended as the “very operation of the feminine in language.” 163 Butler seems to endorse Irigaray’s purely strategic essentialism. However, it is troubling that Irigaray’s true feminine is a name for all that escapes binary oppositions and social hierarchies.

Butler’s critique of Irigaray is that her exclusive focus on the feminine is an implicitly white, middle-class, heterosexual position attending to the marginalization of women qua women but neglecting other forms of social marginalization. Since Irigaray’s true feminine is “exactly what is excluded” from binary oppositions, it “monopolizes the sphere of exclusion,” resulting in Irigaray’s “constitutive exclusions” of other forms of difference. 164 For Irigaray “the outside is ‘always’ the feminine,” breaking its link to race, class, sexual orientation, and so on. 165 By contrast, Butler embraces intersectionality. Whereas for Irigaray sexual difference is “autonomous” and “more fundamental” than other differences, which are viewed as “ derived from” it, for Butler gender is “articulated through or as other vectors of power.” 166

Butler acknowledges her debt to African American literature and feminist thought, in a rare foray into literary criticism, her close reading of Nella Larsen’s 1929 novel, Passing . She also pays tribute to feminists of color, such as Chicana feminist Norma Alarcón, who similarly theorized women of color as multiply rather than singly positioned and marginalized. In Passing and in related African American literary criticism by Barbara Christian, Hazel Carby, Deborah McDowell, and others, Butler finds valuable theoretical insights that “ racializing norms ” and gender norms are “articulated through one another.” 167 But these texts also identify the value of solidarity among black women and the many obstacles to this solidarity. Versions of “racial uplift” adhering to the white middle-class nuclear family have been obstructive; they have been “masculine uplift” whose disproportionate “cost . . . for black women” has been the “impossibility of sexual freedom” for them. 168 Larsen’s critique of “racial uplift”—and its promotion of white middle-class gender norms, marriage, nuclear family, and heteronormativity—grasps the interimplication of race, class, gender, and sexual orientation. By contrast, Larsen’s Passing and Toni Morrison’s Sula uphold the precarious “promise of connection” among black women. 169

If “racial uplift” has been obstructive, Irigaray’s exclusive focus on the feminine is equally obstructive, according to Butler. Irigaray seems to assume that sexual difference is “unmarked by race” and that “whiteness is not a form of racial difference.” 170 By contrast, Larsen highlights historical articulations “of racialized gender, of gendered race, of the sexualization of racial ideals, or the racialization of gender norms.” 171 In Passing Clare passes as white, and Butler’s reading particularly traces the convergence of race and sexuality. Clare’s “risk-taking” takes the dual form of “racial crossing and sexual infidelity” that undermines middle-class norms, questioning both the “sanctity of marriage” and the “clarity of racial demarcations.” 172 Sexual and racial closeting are also interlinked: “the muteness of homosexuality converges in the story with the illegibility of Clare’s blackness.” 173 The word “queering” in Passing is “a term for betraying what ought to remain concealed,” in relation to both race and sexuality. 174

If some early commentators interpreted Butler’s theory of the performativity of gender and her call for gender resignification as a voluntarist, individualist, consumerist lifestyle choice for privileged Westerners, this article has tried to show just how constrained gender resignification is, and how inextricable from other social struggles. In Butler’s more recent work, issues of gender and sexual orientation are situated in interlocking frames of social exclusion and social precarity. Neither gender nor sexual orientation on their own can determine what counts as a human, livable, and grievable life. 175

Susan Stryker, one of the founders of transgender theory, addresses her first publication, “My Words to Victor Frankenstein above the Village of Chamounix” ( 1994 ), to feminist and queer communities and exposes their exclusion and abjection of the “transgendered subject” as a monster. 176 Through a close reading of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein , she expresses her affinity with Frankenstein’s monster. 177 She criticizes the medical discourse that “produced sex reassignment techniques” for its “deeply conservative attempt to stabilize gendered identity in service of the naturalized heterosexual order” and insists on the disjunction between the “naturalistic effect biomedical technology can achieve” and the “subjective experience” of this transformation. 178 She rejects the continuing pathologization of the transgendered subject by psychiatrists, with the effect that “the sounds that come out of my mouth can be summarily dismissed.” 179 Notable here is an emphasis on self-identification and lived experience, which inherits the insights of phenomenological feminists that the body is not an object but a center of perception. To honor this emphasis, Stryker enlists a mixed form that combines criticism, diary entry, poetry, and theory.