The Savvy Scientist

Experiences of a London PhD student and beyond

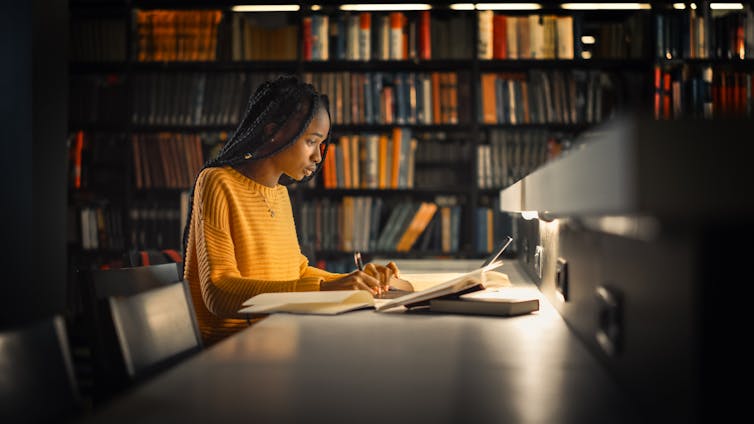

PhD Burnout: Managing Energy, Stress, Anxiety & Your Mental Health

PhDs are renowned for being stressful and when you add a global pandemic into the mix it’s no surprise that many students are struggling with their mental health. Unfortunately this can often lead to PhD fatigue which may eventually lead to burnout.

In this post we’ll explore what academic burnout is and how it comes about, then discuss some tips I picked up for managing mental health during my own PhD.

Please note that I am by no means an expert in this area. I’ve worked in seven different labs before, during and after my PhD so I have a fair idea of research stress but even so, I don’t have all the answers.

If you’re feeling burnt out or depressed and finding the pressure too much, please reach out to friends and family or give the Samaritans a call to talk things through.

Note – This post, and its follow on about maintaining PhD motivation were inspired by a reader who asked for recommendations on dealing with PhD fatigue. I love hearing from all of you, so if you have any ideas for topics which you, or others, could find useful please do let me know either in the comments section below or by getting in contact . Or just pop me a message to say hi. 🙂

This post is part of my PhD mindset series, you can check out the full series below:

- PhD Burnout: Managing Energy, Stress, Anxiety & Your Mental Health (this part!)

- PhD Motivation: How to Stay Driven From Cover Letter to Completion

- How to Stop Procrastinating and Start Studying

What is PhD Burnout?

Whenever I’ve gone anywhere near social media relating to PhDs I see overwhelmed PhD students who are some combination of overwhelmed, de-energised or depressed.

Specifically I often see Americans talking about the importance of talking through their PhD difficulties with a therapist, which I find a little alarming. It’s great to seek help but even better to avoid the need in the first place.

Sadly, none of this is unusual. As this survey shows, depression is common for PhD students and of note: at higher levels than for working professionals.

All of these feelings can be connected to academic burnout.

The World Health Organisation classifies burnout as a syndrome with symptoms of:

– Feelings of energy depletion or exhaustion; – Increased mental distance from one’s job, or feelings of negativism or cynicism related to one’s job; – Reduced professional efficacy. Symptoms of burnout as classified by the WHO. Source .

This often leads to students falling completely out of love with the topic they decided to spend years of their life researching!

The pandemic has added extra pressures and constraints which can make it even more difficult to have a well balanced and positive PhD experience. Therefore it is more important than ever to take care of yourself, so that not only can you continue to make progress in your project but also ensure you stay healthy.

What are the Stages of Burnout?

Psychologists Herbert Freudenberger and Gail North developed a 12 stage model of burnout. The following graphic by The Present Psychologist does a great job at conveying each of these.

I don’t know about you, but I can personally identify with several of the stages and it’s scary to see how they can potentially lead down a path to complete mental and physical burnout. I also think it’s interesting that neglecting needs (stage 3) happens so early on. If you check in with yourself regularly you can hopefully halt your burnout journey at that point.

PhDs can be tough but burnout isn’t an inevitability. Here are a few suggestions for how you can look after your mental health and avoid academic burnout.

Overcoming PhD Burnout

Manage your energy levels, maintaining energy levels day to day.

- Eat well and eat regularly. Try to avoid nutritionless high sugar foods which can play havoc with your energy levels. Instead aim for low GI food . Maybe I’m just getting old but I really do recommend eating some fruit and veg. My favourite book of 2021, How Not to Die: Discover the Foods Scientifically Proven to Prevent and Reduce Disease , is well worth a read. Not a fan of veggies? Either disguise them or at least eat some fruit such as apples and bananas. Sliced apple with some peanut butter is a delicious and nutritious low GI snack. Check out my series of posts on cooking nutritious meals on a budget.

- Get enough sleep. It doesn’t take PhD-level research to realise that you need to rest properly if you want to avoid becoming exhausted! How much sleep someone needs to feel well-rested varies person to person, so I won’t prescribe that you get a specific amount, but 6-9 hours is the range typically recommended. Personally, I take getting enough sleep very seriously and try to get a minimum of 8 hours.

A side note on caffeine consumption: Do PhD students need caffeine to survive?

In a word, no!

Although a culture of caffeine consumption goes hand in hand with intense work, PhD students certainly don’t need caffeine to survive. How do I know? I didn’t have any at all during my own PhD. In fact, I wrote a whole post about it .

By all means consume as much caffeine as you want, just know that it doesn’t have to be a prerequisite for successfully completing a PhD.

Maintaining energy throughout your whole PhD

- Pace yourself. As I mention later in the post I strongly recommend treating your PhD like a normal full-time job. This means only working 40 hours per week, Monday to Friday. Doing so could help realign your stress, anxiety and depression levels with comparatively less-depressed professional workers . There will of course be times when this isn’t possible and you’ll need to work longer hours to make a certain deadline. But working long hours should not be the norm. It’s good to try and balance the workload as best you can across the whole of your PhD. For instance, I often encourage people to start writing papers earlier than they think as these can later become chapters in your thesis. It’s things like this that can help you avoid excess stress in your final year.

- Take time off to recharge. All work and no play makes for an exhausted PhD student! Make the most of opportunities to get involved with extracurricular activities (often at a discount!). I wrote a whole post about making the most of opportunities during your PhD . PhD students should have time for a social life, again I’ve written about that . Also give yourself permission to take time-off day to day for self care, whether that’s to go for a walk in nature, meet friends or binge-watch a show on Netflix. Even within a single working day I often find I’m far more efficient when I break up my work into chunks and allow myself to take time off in-between. This is also a good way to avoid procrastination!

Reduce Stress and Anxiety

During your PhD there will inevitably be times of stress. Your experiments may not be going as planned, deadlines may be coming up fast or you may find yourself pushed too far outside of your comfort zone. But if you manage your response well you’ll hopefully be able to avoid PhD burnout. I’ll say it again: stress does not need to lead to burnout!

Everyone is unique in terms of what works for them so I’d recommend writing down a list of what you find helpful when you feel stressed, anxious or sad and then you can refer to it when you next experience that feeling.

I’ve created a mental health reminders print-out to refer to when times get tough. It’s available now in the resources library (subscribe for free to get the password!).

Below are a few general suggestions to avoid PhD burnout which work for me and you may find helpful.

- Exercise. When you’re feeling down it can be tough to motivate yourself to go and exercise but I always feel much better for it afterwards. When we exercise it helps our body to adapt at dealing with stress, so getting into a good habit can work wonders for both your mental and physical health. Why not see if your uni has any unusual sports or activities you could try? I tried scuba diving and surfing while at Imperial! But remember, exercise doesn’t need to be difficult. It could just involve going for a walk around the block at lunch or taking the stairs rather than the lift.

- Cook / Bake. I appreciate that for many people cooking can be anything but relaxing, so if you don’t enjoy the pressure of cooking an actual meal perhaps give baking a go. Personally I really enjoy putting a podcast on and making food. Pinterest and Youtube can be great visual places to find new recipes.

- Let your mind relax. Switching off is a skill and I’ve found meditation a great way to help clear my mind. It’s amazing how noticeably different I can feel afterwards, having not previously been aware of how many thoughts were buzzing around! Yoga can also be another good way to relax and be present in the moment. My partner and I have been working our way through 30 Days of Yoga with Adriene on Youtube and I’d recommend it as a good way to ease yourself in. As well as being great for your mind, yoga also ticks the box for exercise!

- Read a book. I’ve previously written about the benefits of reading fiction * and I still believe it’s one of the best ways to relax. Reading allows you to immerse yourself in a different world and it’s a great way to entertain yourself during a commute.

* Wondering how I got something published in Science ? Read my guide here .

Talk It Through

- Meet with your supervisor. Don’t suffer in silence, if you’re finding yourself struggling or burned out raise this with your supervisor and they should be able to work with you to find ways to reduce the pressure. This may involve you taking some time off, delegating some of your workload, suggesting an alternative course of action or signposting you to services your university offers.

Also remember that facing PhD-related challenges can be common. I wrote a whole post about mine in case you want to cheer yourself up! We can’t control everything we encounter, but we can control our response.

A free self-care checklist is also now available in the resources library , providing ideas to stay healthy and avoid PhD burnout.

Top Tips for Avoiding PhD Burnout

On top of everything we’ve covered in the sections above, here are a few overarching tips which I think could help you to avoid PhD burnout:

- Work sensible hours . You shouldn’t feel under pressure from your supervisor or anyone else to be pulling crazy hours on a regular basis. Even if you adore your project it isn’t healthy to be forfeiting other aspects of your life such as food, sleep and friends. As a starting point I suggest treating your PhD as a 9-5 job. About a year into my PhD I shared how many hours I was working .

- Reduce your use of social media. If you feel like social media could be having a negative impact on your mental health, why not try having a break from it?

- Do things outside of your PhD . Bonus points if this includes spending time outdoors, getting exercise or spending time with friends. Basically, make sure the PhD isn’t the only thing occupying both your mental and physical ife.

- Regularly check in on how you’re feeling. If you wait until you’re truly burnt out before seeking help, it is likely to take you a long time to recover and you may even feel that dropping out is your only option. While that can be a completely valid choice I would strongly suggest to check in with yourself on a regular basis and speak to someone early on (be that your supervisor, or a friend or family member) if you find yourself struggling.

I really hope that this post has been useful for you. Nothing is more important than your mental health and PhD burnout can really disrupt that. If you’ve got any comments or suggestions which you think other PhD scholars could find useful please feel free to share them in the comments section below.

You can subscribe for more content here:

Share this:

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

Related Posts

How to Master Data Management in Research

25th April 2024 27th April 2024

Thesis Title: Examples and Suggestions from a PhD Grad

23rd February 2024 23rd February 2024

How to Stay Healthy as a Student

25th January 2024 25th January 2024

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Notify me of follow-up comments by email.

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

Privacy Overview

‘You have to suffer for your PhD’: poor mental health among doctoral researchers – new research

Lecturer in Social Sciences, University of Westminster

Disclosure statement

Cassie Hazell has received funding from the Office for Students.

University of Westminster provides funding as a member of The Conversation UK.

View all partners

PhD students are the future of research, innovation and teaching at universities and beyond – but this future is at risk. There are already indications from previous research that there is a mental health crisis brewing among PhD researchers.

My colleagues and I studied the mental health of PhD researchers in the UK and discovered that, compared with working professionals, PhD students were more likely to meet the criteria for clinical levels of depression and anxiety. They were also more likely to have significantly more severe symptoms than the working-professional control group.

We surveyed 3,352 PhD students, as well as 1,256 working professionals who served as a matched comparison group . We used the questionnaires used by NHS mental health services to assess several mental health symptoms.

More than 40% of PhD students met the criteria for moderate to severe depression or anxiety. In contrast, 32% of working professionals met these criteria for depression, and 26% for anxiety.

The groups reported an equally high risk of suicide. Between 33% and 35% of both PhD students and working professionals met the criteria for “suicide risk”. The figures for suicide risk might be so high because of the high rates of depression found in our sample.

We also asked PhD students what they thought about their own and their peers’ mental health. More than 40% of PhD students believed that experiencing a mental health problem during your PhD is the norm. A similar number (41%) told us that most of their PhD colleagues had mental health problems.

Just over a third of PhD students had considered ending their studies altogether for mental health reasons.

There is clearly a high prevalence of mental health problems among PhD students, beyond those rates seen in the general public. Our results indicate a problem with the current system of PhD study – or perhaps with academic more widely. Academia notoriously encourages a culture of overwork and under-appreciation.

This mindset is present among PhD students. In our focus groups and surveys for other research , PhD students reported wearing their suffering as a badge of honour and a marker that they are working hard enough rather than too much. One student told us :

“There is a common belief … you have to suffer for the sake of your PhD, if you aren’t anxious or suffering from impostor syndrome, then you aren’t doing it "properly”.

We explored the potential risk factors that could lead to poor mental health among PhD students and the things that could protect their mental health.

Financial insecurity was one risk factor. Not all researchers receive funding to cover their course and personal expenses, and once their PhD is complete, there is no guarantee of a job. The number of people studying for a PhD is increasing without an equivalent increase in postdoctoral positions .

Another risk factor was conflict in their relationship with their academic supervisor . An analogy offered by one of our PhD student collaborators likened the academic supervisor to a “sword” that you can use to defeat the “PhD monster”. If your weapon is ineffective, then it makes tackling the monster a difficult – if not impossible – task. Supervisor difficulties can take many forms. These can include a supervisor being inaccessible, overly critical or lacking expertise.

A lack of interests or relationships outside PhD study, or the presence of stressors in students’ personal lives were also risk factors.

We have also found an association between poor mental health and high levels of perfectionism, impostor syndrome (feeling like you don’t belong or deserve to be studying for your PhD) and the sense of being isolated .

Better conversations

Doctoral research is not all doom and gloom. There are many students who find studying for a PhD to be both enjoyable and fulfilling , and there are many examples of cooperative and nurturing research environments across academia.

Studying for a PhD is an opportunity for researchers to spend several years learning and exploring a topic they are passionate about. It is a training programme intended to equip students with the skills and expertise to further the world’s knowledge. These examples of good practice provide opportunities for us to learn about what works well and disseminate them more widely.

The wellbeing and mental health of PhD students is a subject that we must continue to talk about and reflect on. However, these conversations need to happen in a way that considers the evidence, offers balance, and avoids perpetuating unhelpful myths.

Indeed, in our own study, we found that the percentage of PhD students who believed their peers had mental health problems and that poor mental health was the norm, exceeded the rates of students who actually met diagnostic criteria for a common mental health problem . That is, PhD students may be overestimating the already high number of their peers who experienced mental health problems.

We therefore need to be careful about the messages we put out on this topic, as we may inadvertently make the situation worse. If messages are too negative, we may add to the myth that all PhD students experience mental health problems and help maintain the toxicity of academic culture.

- Mental health

- Academic life

- PhD research

Research Fellow

Senior Research Fellow - Women's Health Services

Lecturer / Senior Lecturer - Marketing

Assistant Editor - 1 year cadetship

Executive Dean, Faculty of Health

The PhD Experience

- Call for Contributions

How do you cope with PhD stress?

This week for a slightly different kind of post, we asked some of the Pubs and Pubs team ‘what has been the most stressful thing for you lately? How have you coped with this?’ Here is how we get through when things seem to be going against us:

One of the main challenges I find, both in general and over the last few weeks, is staying focused on my core task of working towards the PhD. There’s always another semi-relevant book to read, or conference proposal to write, let alone maintaining contact with friends and loved ones. For various different reasons I’ve also been unable to attend my regular writing group this term, which was usually the time when I refocused my efforts on my thesis. In the last week, I’ve been much stricter about setting aside time for writing, and have done some new plans of my current chapter and the overall thesis. This has helped me to reconnect with my own work, and begin to make more definite progress. I think that I also need to update my diary more regularly again, to maintain a sense of direction and purpose. If I have a message for others here, it’s to be aware of your own working practices, and change them if things don’t seem to be going right.

Don’t take on too much

I recently said yes to a few too many things and as a result have to deliver papers at an average rate of one-per-week in November. While I am grateful for the opportunities, it has also left me with an unwieldy workload. My solution was to liaise with individuals organising the conferences/lectures and, where possible, alter my originally agreed title so that I could deliver a similar paper at most events. This meant I could hone one specific topic thus significantly reducing my stress levels! The general takeaway point, I guess, is to never be afraid of reaching out to people who have the ability to help you.

Look after yourself

I have always been a sickly person – it’s good I did not live before antibiotics or I would never have made it out of childhood. I have never, however, experienced anything like the past few months. In these final months of my PhD I’ve had a wide and alarming variety of health issues, the latest of which is tonsillitis. It has been absolutely remarkable to see just how much of an impact stress can have on my body. Unfortunately, I am still in the process of figuring out how to deal with this. Step one, and something I think every PhD student I know could be better at, is to actually take time off. We all know forcing ourselves to work and stressing about the time we are missing does not help us get better, but it is incredibly difficult to fight the impulse. I even offered to write this post solo – from my bed – before the committee wisely decided on a joint venture. So, I’m turning over a new leaf and taking some time off this week to lie in my bed and watch Netflix. I can’t promise it will be guilt-free, or that I won’t be checking my emails, but it’s a start!

Get a hobby

Recently I have been suffering from the final year blues. The deadline for submitting the PhD is hurtling towards me at an indecent speed and I’ve still got so much to do. Yet my brain seems to have stalled, I struggle to make it think at all. Even recalling memories from family holidays or characters from films/book seems to require a colossal effort, whilst I can’t seem to stop replaying the same worry on loop- how will I ever finish this??? Over the summer, however, I joined the Edinburgh City Brass Band. I come from an area that is famous for brass banding and have always played. When I started the PhD though, as with so many other things my cornet got neglected and my valves began to stick. Playing again has been a Godsend, for two hours a week I physically can’t think about work because there is a man waving a stick in front of me demanding I hit that Top A. Come to think of it that might be part of my problem- maybe I’ve been constricting the airflow to my brain. It has also provided additional structure to my week, a guilt-free break and a new group of people to socialise with who have nothing to do with the office. I can’t get sucked into talking about migration theories or micro-history- nobody cares! After rehearsals I feel refreshed and able to reset. I know there is nothing new in encouraging people to maintain hobbies outside the PhD, but as someone who finds it hard to turn off I think if I didn’t have a hobby that demands my undivided attention I would be really struggling to cope.

Try not to burn out

Being on what feels like the final stretch of the PhD has proven surprisingly stressful. I think pacing yourself is much easier when the task ahead seems very large – you can’t climb that mountain in one day, so why would you even try? But when the end seems close, the temptation to work a bit harder and longer creeps in. All it might take is one final burst to the finish line – or so it seems, because of course finishing is still a pretty long process that can’t be knocked off in the course of an afternoon.

Actually dealing with this realisation is another question. Self-awareness only takes you so far, and to a certain extent you actually need that extra impetus to get you over the line. It’s a race between finishing and burning out at this stage.

Final thoughts

Everyone’s path through the PhD is different, what we’ve offered here are a personal challenges at techniques at particular points we have all reached in our studies. If you’d like to share you experiences and tips, tweet us ! And consider joining our team to help PhD students across the world feel a little less alone, you have one week until the deadline.

You can find out more about Sam, Maurice, Laura, Roseanna and Fraser on our Who We Are page

Image 1: Stress, CC-BY-SA, Nick Youngson

Image 2: Pexels.com, CC0

Image 3: less is more, CC-BY, Floriana

Image 4: Pixababy.com, CC0

Image 5: Australia Alexandra Brass Band, 1906, public domain, wikimedia commons

Image 6: maxpixel, CC0

Share this post:

Samgrinsell.

November 3, 2017

academia , Phd

focus , hobbies , phd , planning , stress

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Notify me of follow-up comments by email.

Notify me of new posts by email.

Search this blog

Recent posts.

- Seeking Counselling During the PhD

- Teaching Tutorials: How To Mark Efficiently

- Prioritizing Self-care

- The Dream of Better Nights. Or: Troubled Sleep in Modern Times.

- Teaching Tutorials – How To Make Discussion Flow

Recent Comments

- sacbu on Summer Quiz: What kind of annoying PhD candidate are you?

- Susan Hayward on 18 Online Resources and Apps for PhD Students with Dyslexia

- Javier on My PhD and My ADHD

- timgalsworthy on What to expect when you’re expected to be an expert

- National Rodeo on 18 Online Resources and Apps for PhD Students with Dyslexia

- Comment policy

- Content on Pubs & Publications is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.5 Scotland

© 2024 Pubs and Publications — Powered by WordPress

Theme by Anders Noren — Up ↑

Community Blog

Keep up-to-date on postgraduate related issues with our quick reads written by students, postdocs, professors and industry leaders.

5 Ways to Combat PhD Stress

- By Nicholas R.

- January 8, 2024

When you’re starting your research career as an academic researcher, there will be many things that overwhelm you when you start out. As someone who has been through this myself, I have put together 5 ways of dealing with overwhelming feelings during your PhD journey.

These strategies may not work every time, but they’ve helped me get through my own struggles so far and hopefully can help you too!

1. Know What’s Going On

Before you dive into trying to solve any problem or figure anything out, take care of yourself mentally by knowing what exactly overwhelms you at the moment. One way to do this is to journal about what stresses you right now. When you feel more able to cope, try exploring solutions for those issues.

For example, if you find yourself struggling with managing workload, then it might be helpful to know that this type of stress often occurs at the very beginning and very end of a PhD, at least for myself and others I’ve spoken to.

Knowing the sources of your stress is the first step to addressing it.

2. Take Care of Yourself

Once you understand why you’re feeling overwhelmed, the next thing to consider is taking care of yourself physically. Stress from work, school, relationships etc., all contribute to poor health decisions such as skipping meals, engaging in unhealthy eating habits, drinking or smoking excessively, reducing sleep and exercise etc. All of which impact negatively on our physical and mental well-being.

In addition, one study showed that people under extreme levels of pressure (such as doctoral candidates) were more prone to developing heart problems compared to other groups. So while taking care of yourself should always be a priority, it’s especially important to prioritise it even further when we’re stressed.

It can seem difficult to balance personal needs and researcher responsibilities, but doing so requires prioritising self-care over everything else. In order to achieve this, set aside dedicated blocks of time each day where you avoid distractions, focus solely on activities related to your wellbeing, and allow yourself to fully engage in whatever activity brings peace to your mind and body.

3. Talk About It With Friends and Family

One thing that you learn early in a PhD is that there’s no such thing as a free lunch. While the rewards of doing your PhD are many, there is a significant cost, and it comes in the form of stress.

You’ve probably heard the expression “ PhD students are walking time bombs ” – which is basically just a polite way of saying that PhD students are walking around with a serious short-fuse, and it’s only a matter of time before that fuse goes off.

Seek support from others before that happens…

Talking to close friends and family members helps us to process emotions better. Research shows that talking to others provides relief by releasing negative thoughts and worries, so we don’t need to carry them around inside ourselves throughout the rest of the day. Having supportive individuals in our lives makes it easier to handle both small tasks and large ones.

If you live alone, however, having someone available to discuss your concerns with can provide valuable insight into whether or not you’re handling stressful events properly. A friend or family member can offer perspective and guidance without judging you for your current situation.

4. Make Time For Fun Activities

We’ve all heard that it takes 10 years to make a really brilliant scientist. You might have trouble proving this, but it is a very long time, and many people struggle with sticking to a research plan that is longer than 3 months.

We also know that there are many distractions available in the ‘real world’, that are not available to researchers. A few months ago, for example, I went to a pub quiz night. While this may sound like a total waste of time, in fact it has become a huge amount of fun for me, and has helped me to get my research into the right place.

I also find that regular, non-research-related social events help keep things fresh and remind me that there are more important things than my research at the moment.

5. Accept That This Is Just Part Of The Process

The hardest part about completing a PhD program is simply surviving it. Many of the lessons learned along the way will come from overcoming obstacles and failures. Learning from setbacks and mistakes prepares us for future success. But sometimes, no matter how hard we try, we just won’t be successful at accomplishing certain milestones or reaching our desired outcome.

That doesn’t mean giving up though. Instead, accept that failure can happen and move onto bigger opportunities. Sometimes we learn more from our successes and achievements rather than focusing on our failures and shortcomings. Also, remember that setbacks aren’t permanent. Often, after a short period of mourning, we bounce back stronger than ever.

We shouldn’t beat ourselves up over failing. Rather, let it inspire us to become wiser and smarter for next time. After all, it takes countless attempts to master the skills required to succeed.

Regardless of how you’re feeling, remember that you are not alone. You are not alone on your PhD journey. You are not alone in your feelings. And you are not alone in your desire to succeed.

The answer is simple: there is no age limit for doing a PhD; in fact, the oldest known person to have gained a PhD in the UK was 95 years old.

There are various types of research that are classified by objective, depth of study, analysed data and the time required to study the phenomenon etc.

An abstract and introduction are the first two sections of your paper or thesis. This guide explains the differences between them and how to write them.

Join thousands of other students and stay up to date with the latest PhD programmes, funding opportunities and advice.

Browse PhDs Now

How should you spend your first week as a PhD student? Here’s are 7 steps to help you get started on your journey.

De-Shaine is 2nd Year Neurotechnology PhD Student at Imperial College London. His research looks at monitoring the brain when it’s severely injured after a traumatic brain injury or stroke and patients are in neurocritical care.

Sara is currently in the 4th year of the Physics Doctoral Program at The Graduate Center of the City University of New York. Her research investigates quantum transport properties of 2D electron systems.

Join Thousands of Students

Advice to myself: Starting the final year of a PhD

- No Comments

Having completed a good ¾ of my PhD remotely, I like to think that I’ve learnt a thing or two about motivation, reflection, and time-management. Here are a few things I’ve realised over the last 18 months that I am going to try and keep reminding myself of as I navigate the next year. Even if I don’t follow my own advice, there’s always hope that it’ll help another student .

Alicia Peel, EDIT Lab PhD student

1. Never start from a blank page

2. Teams is academic Instagram (and you are being catfished)

The versions of ourselves that we present in meetings are always the best, most put together versions. Having remote meetings on Teams has just exacerbated this. What you see of someone from the shoulders up for a few hours each week is rarely an accurate reflection of how they are actually functioning. Similar to a duck appearing to be swimming calmly on the surface of the water but paddling frantically below. Most other PhD students that I have spoken to remark on how everyone is coping better than them, working harder than them, producing more than them. But this only seems true because that’s all we show each other. The reality is that we are all giving ourselves a quick pep talk in the two minutes before our team meeting starts every week and summoning all of our strength to present our happiest and most high-functioning selves. We look like we’re on top of things because yesterday we didn’t leave our desk until we’d worked through the whole of our to-do list. The analysis we’re presenting seems so well thought out and ground-breaking because we’ve been stressing about every tiny part of it for the last three months. And as soon as the meeting is over? We’re going to be back in our dressing gowns crying into our third cup of coffee about the colour scheme of our WCPG poster.

“Most other PhD students that I have spoken to remark on how everyone is coping better than them, working harder than them, producing more than them.”

3. The PhD workload is dynamic

During every PhD, there are times when we will be working flat out, all hours of the day, to meet deadlines. What I’ve learnt is to use the times when things are quieter to balance out those manic periods. If you find yourself with a day or two where you’re on top of your to-do list, make the most of working at a slower pace. Do not make things harder for yourself by panicking about why you’re not insanely busy, feeling guilty that you could be working harder or inventing tasks that will end up being a waste of your time. Take those days as opportunities to dedicate a few hours to reading interesting papers that have been pushed to the bottom of the pile, or catching up on academic admin, like updating your CV, researching post-doc options or getting your thesis notes organised. Or even ending your day early and going for a walk. Being productive doesn’t always mean churning out papers, and those “slower” days go a long way towards helping you feel more prepared to handle the busier times.

“Use the times when things are quieter to balance out those manic periods.”

4. Start things early

Everything is more enjoyable when it’s not a high-stress task. Try keeping a note of ‘further-in-the-future’ tasks somewhere. These could bethings like conference posters, presentations or even writing up a paper. When you get an awkward short gap between meetings, or you’re waiting for feedback on something before you can resume working on it, go to that list of future tasks and make a start on something. You might not get very far, but you’ll thank yourself for any progress when you eventually come back to it two days before the deadline. Plus, it’s a nice change of pace to occasionally work on something that doesn’t have the pressure of an imminent deadline looming over it.

5. Every PhD is different

The paradox of being a research student: everyone’s PhD is better than yours. In reality, it’s almost impossible to compare PhDs and you definitely shouldn’t evaluate the strength of yours based on what others have done (or what you perceive others to have done). Some students collect their own data, some use several different methods, some take on more active roles in other aspects of research life. All these things mean that every single student is balancing their workload differently and will produce a different output. Even other students in the same lab, using the same methods, will have faced a completely different set of challenges because their research questions are different. If they weren’t, your PhD wouldn’t be a unique compilation of research. At a glance, everyone else’s projects look better simply because you are only paying attention to the headlines. The hardest thing to do is to take a step back and imagine how impressive your research and achievements look to other students (and if you can’t picture that on your own, go and talk to a new first year student for a nice ego boost).

“The paradox of being a research student: everyone’s PhD is better than yours.”

How much of my own advice will I follow in the next year? That remains to be seen. By the time I’m approaching handing in my thesis my perspective may have completely changed and these points could go out the window (“start things early” haha nice try). But for now, the aim is to approach my final year with a sense of balance, realism, and intention to complete the best PhD that I can in the boundaries I am working within. I’ll let you know how it goes.

Previous Post Self- reported medication use as an alternative phenotyping method for anxiety and depression in the UK Biobank

Next post comparison of anxiety and depression symptom networks in individuals who do and do not report traumatic life events.

Author Alicia Peel

Comments are closed.

Careers within research

Work-life balance

Working from home

Book & show reviews

Mental health & wellbeing

Genetics & mental health

- Anti-racism

- Learning From Doing

- Life Scientific

- Mythbusters

- Research Matters

- The Wider World

- Authors & contributors

Follow this blog

Social media.

© 2024 The EDIT Blog.

Recent Posts

- Binge-type eating disorders: is ethnicity associated with the rate of diagnosis?

- Mental Health in Millennials

- First International Conference

- PhD applications

- Visiting another lab as a PhD student: part 2

Recent Comments

- A call for diversity in genetics research: Part 2 – The EDIT Blog on A call for diversity in genetics research: Part 1

- Reflecting on resilience: Part 2 – The EDIT Blog on Reflecting on resilience: Part 1

- Collaboration between academic and voluntary organisations: Part 2 – The EDIT Blog on Collaboration between academic and voluntary organisations: Part 1

- Zain-Ul-Abideen Ahmad on Self-Report Measures and the Replication Crisis

- Post Of The Week – Saturday 30th January, 2021 | DHSB/DHSG Psychology Research Digest on Measuring race, ethnicity and ancestry in research: time for new tools

Dr Rachael Lappan

Microbiologist and ARC DECRA Fellow

- Melbourne, Australia

- ResearchGate

- Google Scholar

Surviving the final year

12 minute read

Published: February 22, 2019

I recently survived the final year of a PhD. Yes, it can be done. Look! I’m actually handing it in and moving on with my life! (Sort of).

After 8 years as a student at @uwanews , 5 years of which were spent at @telethonkids , I am finally entering the real world and am now just... unemployed 😅Thanks to everyone whose support got me here. #PhD #phdchat #phdone #phdohgodwhatnow pic.twitter.com/mztxbgCOOk — Rachael Lappan (@RachaelLappan) December 19, 2018

Each individual’s PhD experience is very unique, but I expect most people will experience stress, burnout, misery, guilt, despair, impostor syndrome or a mid-PhD crisis at some point along the way. Spatterings of these things probably serve to build character, but they’re a real problem when they impede your progress and drain your overall life happiness. The final year in particular, where everything suddenly becomes real and urgent, is generally going to suck for a while. Now, no advice you will receive is going to be a replacement for counselling (which is absolutely worth trying even if you consider yourself mentally healthy). But here’s some perspectives, in no particular order, from someone who made it out alive (but not unchanged). 1

Managing time and commitments

Dealing with being overwhelmed, life stuff (that non-phd stuff that wasn’t supposed to disappear), getting the thing done.

At the start of your PhD, it may have been easier to plan your time. With 3-4 years ahead of you, there was plenty of room to be generous in estimating how long things might take. It was forseeable that you may not get all the results you hoped for, the research direction may change, or that you might run into a bunch of technical challenges. This is scientific research. However, now you’re in the final year everything needs to be wrapped up and finished. Going weeks or months over schedule because of other commitments, experiment failures or new avenues of research now means that you’re going to have to either live without money or spend most of your time on a paid job to survive. Delaying your submission makes it harder to finish, especially if the rest of your life moves on. So this is the year to be strict with your time.

Say no to more things. Be very critical of what you spend your time on. You are allowed to say no to things that take up chunks of your time but do not help you finish your thesis. People will understand, especially if they have a PhD. I tried to focus on things that either substantially added to my CV, or paid me some money. The rest of my time was mostly thesis, sleeping, eating and not abandoning my hobbies . Even then, remember that ‘finishing’ your thesis doesn’t mean ‘completing all the things’ - plan out what you need to achieve in order to have a good, examinable thesis. You may need to let go of other experiments/analyses if you simply do not have the time. This ensures you don’t end up doing an endless PhD, but can also be somewhat liberating; it’s nice to say “I simply haven’t got enough time left” and not have to worry about months of optimising, failure, or gaining a deep understanding of the method only to find out it doesn’t help you answer your question anyway.

Don’t worry about hours. Your time is up to you, especially once you’re in the writing up phase. I mean, don’t sleep through meetings with your supervisors, but in general, I found it beneficial to try and let go of the idea that I had to be in at 9am each day. You have a finite number of hours between now and when you submit, so it makes sense to use them whenever you will be most productive. If you need more sleep, get more sleep. If today’s a bad day and you only get a couple of hours work done, that’s okay. Nobody’s counting (and if they are, they shouldn’t be - like I say, we’re aiming for efficiency this year, not total time spent in agony). Weekends and evenings are probably going to be necessary, but I tried to leave easier work (like formatting) for these times when I knew my brain wouldn’t be very happy to be working.

At some point this year you may feel overwhelmed. Sometimes you will be so overwhelmingly overwhelmed that you find yourself unable to work. I found that this usually happened when I was hit by the sheer amount of work I had left to do (unquantifiable) and the short amount of time in which I had left to do it (quantifiable). I think this is where the panic comes from; the uncertainty of exactly how much time you do need, and the certainty of how much time you’ve got left. Something that helped me overcome this was to remember that at no point do you have do all of this work at once. The entire PhD is completed one small task at a time, no matter how good you are.

I would write lists or plan things out on paper when I became overwhelmed. This is where fountain pens and nice quality paper can change your life (that’s what I reckon anyway). Keep planning and replanning. This can keep you clear on what your goals are for each day. Make the tasks small (subsections or paragraphs for example); the smaller they are the more you get to tick off in a day, and the more productive you will feel. What is the most urgent task? What is the first step? Go from there. Sometimes taking a few minutes to clear your head (with a free 5-minute guided meditation for example, like in the Headspace app) can help you refocus and get cracking on something. You don’t need to plan out your whole week, or even your whole day - just what comes next. While you are writing up, you may also be needing to write some job applications. It is hard to do both at once when you are so stressed, but that’s okay - just slot it into your plan. Work on an application when you get sick of your thesis.

Also, in general - don’t compare yourself to others. It’s not a reliable measurement as there’s too many variables that differ and you’re each a sample size of 1. You really are your own worst critic. Be nice to yourself - remember, the poor thing is trying to finish a PhD.

Don’t forget about your family, friends, partner, children or fluffer. They love you. In the final year when you are probably at your busiest, it’s important to remember to make time for them. But you’re so busy, I know. However, remember that periods of rest are as essential as periods of work for long-term functioning. That’s how hearts work , and look at their productivity. Make the commitment to a dinner, some games, an outing, a short holiday - it doesn’t have to be much, but a bit of time without the PhD on your mind can be a great relief. It is challenging to combat the guilt, but I often reminded myself that I will be more efficient tomorrow if I conk out at 1pm, have a break, and come back fresh than if I push through into the evening when I’m just not feeling it. Always prioritise sleep.

The other important part of your life is food. Try to continue to eat well; if you eat poorly, you’ll feel worse in general (though I absolutely understand that a whole bag of chips can get you through a chapter). It really helps to have someone at home who can cook all your dinners for you (thanks Scott). If you don’t, look into those budget one pot meals and a slow cooker and cook up as many servings at once as you can (e.g. Budget Bytes ). This is especially useful when your scholarship funds have run out. Just don’t fill yourself with 2 minute noodles - you may never shit again. At least have some Metamucil with them.

I like producing good pieces of writing, and I’m reasonably good at it. The trouble with producing good writing is the part where you actually have to write the thing. You may experience a strong desire for your vague mental image of a chapter to just happen (you promise not to tell anyone if the universe just messed up and it appeared). How easy it must be for everyone else to say “you’re nearly there!” and then sit back for a couple of months until your complete thesis emerges into existence.

I cannot match the writing advice of countless books and blogs, so here’s my bit. Just put something. Just spill your thoughts onto the page in some way. Then have a look at it another day, and fix it a bit. Then you can fix it some more, and maybe someone else will help you fix it. Then it will look much better. Having access to a whiteboard is useful for organising thoughts. Read it out loud to yourself and see if anything sounds dopey. Writing can be hard and it can suck, but each day you write something , even if it later gets deleted, is progress. Know that you are always moving forwards and never backwards. Additionally, it doesn’t have to be perfect, or even really great. If it’s not good enough , your supervisors and/or your examiners will let you know. Once your PhD is complete, you will not be reading it several times in the years to come thinking “that paragraph’s a bit crap and could have been better.” I mean you might, but you a) should probably never look at it again for your own sanity and b) won’t care, because you’ve got the PhD anyway.

Remember, that’s the ultimate goal here: get a PhD.

Also, keep in mind that you not only need to write your thesis, but to format it too. Don’t overlook the formatting; it can take much longer than you think. If you’re formatting in Word, prepare for it to refuse to save your document, destroy your computer, and shift all of your figures into the void behind the page each time you correct a typo. If you are using something better suited to theses like LaTex or Bookdown (highly recommend if you’re willing to learn), start formatting some completed chapters early if you can; LaTex in particular can be a steep learning curve and you will need to spend a decent amount of time troubleshooting errors and improving appearances on the page. Getting this done earlier in the year will greatly relieve your stress when writing the final discussion.

So. To all of you who are in the final year of your PhD, or have a final year coming up: you are always moving forwards, even if it doesn’t feel like it. You will soon leave the PhD-phase of your life. The bad days will happen, and they will pass. Just move on to the next task. Continue moving on until the task is ‘submit’.

I hope this was a helpful, comforting or relatable read. Keep in mind that all of the advice you receive this year is just advice - only you know what is best for you. Feel free to leave a comment below, find me on Twitter , or email me . Thanks for reading - and you will survive!

1 In a good way! I can deal with stress, deadlines and pressure with greater ease now that I have done a PhD. It helps knowing that I’ve made it through something tough before. It probably also helps to not be in the midst of a PhD anymore, but the point is; I can have faith in my abilities if I just remember that I made it through a PhD. No matter where your career goes after this, that is something to always remain proud of.

Leave a Comment

You may also enjoy, tips for introverts at scientific conferences.

11 minute read

Published: July 19, 2018

Earlier this month I was at ASM 2018 in Brisbane, which contained a lot of great microbiology! I always love spending time in Brisbane, but this time, I was giving a talk at 5:20pm on my birthday… at least it was a productive birthday!

The microbiome in children with recurrent ear infections - new paper

Published: February 26, 2018

This year is the PhD’s final year, so I’m going to become a bit of a hermit and will probably be blogging less.

Text editing from the command line with vim

9 minute read

Published: December 21, 2017

When learning bioinformatics, you will perhaps need to create or edit text files, shell scripts or Python scripts from the command line. Using a Unix-based text editor is also good practice for getting used to the environment if you are new to the command line. I have seen that many people have their preference for nano , emacs or vim . I started with nano, as it is quite straightforward to use - but then I moved to vim (probably because it had lots of colours).

How I teach myself new bioinformatics tools

8 minute read

Published: November 08, 2017

I’m not sure if there’s a name for people who thought they would be doing lab work for the rest of their lives and then find themselves thrust into the deep end of bioinformatics, but I am one of them. This seems to be a common occurrence in research labs, and will probably continue to be until undergraduate programs catch up with the bioinformatics skills required in many fields of research. Fortunately I quite enjoy the stuff, but I am continually learning new things, and I find that with much of it self-taught it can be a long process to learn and then do each analysis.

- Public Lectures

- Faculty & Staff Site >>

Advice Topic: Stress Management

Slowing down, being present.

As the spring quarter begins, we know that many of you will be experiencing anxiety over fulfilling requirements for your very first —or final — year in your grad program, planning your career trajectory beyond the UW, or managing your time to balance work, family, and graduate school. As the weeks go by, the work will seem to just pile up. This is real.

The good thing is, you can approach being a graduate student from a totally different perspective — by being intentional and mindful. We invite you to take a deep breath (really, a full breath in and out), create some space for yourself to slow down, and check out some possible strategies for being mindful that you can consider incorporating into your schedule.

Resist busyness. There’s an unspoken culture in graduate school that perpetuates the idea that over-productivity is a good thing: that performing and talking about how busy we are is key to being successful in a graduate program. Stanford Career Coach Dr. Chris Golde offers a different perspective and states, “Graduate students report more than can be done.” She recommends slowing down “to make peace with [our] limitations,” and says “there will always be those around you — students and faculty — who accomplish far more than you do. Hold yourself to a standard of what is realistic for you.”

Set achievable goals. It can be tempting during this time of the year to be overly ambitious about your goals, and setting an unrealistic standard for yourself can actually lead to you not achieving what’s most important to you — whether you are in career planning mode, completing your capstone, thesis or dissertation, or working on or off campus. Again, we invite you to slow down. We know that when we were in graduate school, goal setting wasn’t something that we suddenly knew how to do. Take some time to map out and visualize your goals. And finally, we encourage you to reward yourself for each task you complete towards your end goals.

Be mindful. Mindfulness can simply be defined as taking time to observe your thoughts, feelings, and bodily sensations from moment to moment, without judgment. Why would this be beneficial to practice while you are in graduate school? Research has shown that over time, mindfulness can help us be more compassionate to ourselves and people in our communities, help us be less reactive and more calm in the face of conflict, and help us increase our focus to what truly matters in our lives.

We hope these strategies are helpful to you as you as you navigate the new quarter!

Your mental health and well-being matter to us,

Core Programs Team #UWGradSuccess

5 tips to boost your productivity

All of us struggle with motivation at different times, and winter can be particularly challenging. That said, it can also be a good time to hunker down and get some work done. Whether you plan to stay in academia or not, you will need written products coming out of your postdoc years to demonstrate what you have accomplished. Perhaps you are also finishing up publications from your doctoral research or laying the groundwork for a new research direction. Recently, the National Center for Faculty Diversity and Development (NCFDD)’s “Monday Motivator ” featured 5 tips for productivity.

- Create a plan. How? Dr. Rockquemore writes: “It’s a simple process: 1) list your writing and wellness goals for the remainder of this calendar year, 2) map out all the steps that are needed to complete your goals, and 3) figure out when that work will get done.” While it may not be in your skill set yet, it is truly simple once you start. During your next work week, put “Planning” in your calendar for a 1-2 hour block and work through it. This is your work . This is a great time to revisit your Individualized Development Plan (IDP).

- Write every day. We also know that your own writing is the task that will consistently get put aside for other demands (e.g. lab meeting, responding to your advisor, looking up one more article, sifting through Facebook, etc.). Research shows that if you dedicate just 30 minutes a day to writing (really writing), you will make consistent progress toward a writing goal and complete a product faster than if you hope for a half-day or protected Saturday that never does emerge.

- Join a group of daily committed writers . You are not alone. We all have to write and produce. Just like a regular exercise or spiritual practice, if you are connected with others who are also committed, it helps you sustain the practice. You can meet face-to-face for your blocks of writing time or just stay connected online and check-in, which gets to the next point:

- Commit to regular accountability. Tell someone your goals and plans, and schedule a check-in meeting (virtually or in-person) to see how it is going. In the short-term, this can be yourself. Apps such as Grid Diary can help you self-assess at the end of the day what 3 things you accomplished, and set personal goals for how tomorrow can be better.

- Find dedicated mentors . All of this takes hard work, and sifting through the noise that comes at you on a daily basis. Find mentors—you should have a full team—who genuinely are invested in your success (see blog posts on mentoring ). They can help hold you accountable, prioritize what needs to happen, strategize where products need to go, and troubleshoot when things fall through the cracks (which they will).

If you are interested in signing up for a weekly email with these Monday Motivator tips from NCFDD, or checking out other writing resources on their website, you can login with the UW membership.

Pushing Through to the End of the Quarter

It’s the home stretch of the quarter and we know you are actively working through your projects, grading, and other milestones, even while looking ahead to the break. We offer a few tips that can help you make the most of these final weeks.

Set Priorities. Look over your schedule for the next two weeks. Block out time slots you know you can’t be flexible on: hard deadlines for school, work, and family time. Hold off on meetings or appointments that can actually wait until after the quarter (and holiday break) is done. You’ll start to see where you have wiggle room for things like self-care. The reality is, there is always time take care of ourselves. This can be a glass of water, a healthy snack, getting up from your desk to stretch, a 10-minute walk outside, or even taking a nap to improve your productivity. Setting priorities allows us to realistically see that we do have control over our schedules, especially when stress makes us feel the complete opposite.

Writing. Carve out 30 minutes of time each day to work on your writing. Set a timer, close your web browsers, and unplug from social media. You’ll find that you’re eventually making progress on that larger writing project. For more support, remember that you can schedule an appointment with a writing tutor at your UW campus. You also have the option of reaching out to a peer or two in your department — or from outside of your program — to hold one another accountable for writing by organizing group writing sessions. If you’re considering something more structured beyond this quarter, here are some tips for organizing a thesis or dissertation writing group.

Connect with your support network. It can be a struggle to stay motivated these last few weeks of the quarter and complete what needs to get done. But as Andrea Zellner from GradHacker states, “Don’t underestimate the power of your cheering section. Maybe all you need to get moving is a pep talk.” Call, Skype, or meet up with a close friend or family member, so they can root you on! Attend a community gathering with like-minded peers, such as the upcoming Holiday Gathering for First-Gen Graduate Students in Seattle, or the Holiday Wine, Beer & Spirits Walk in Bothell, or organize a low-key, small potluck with peers to celebrate one another. If you’re needing mental health support — and there is no shame in this at all — reach out to your campus counseling center for an appointment or for community resource referrals.

Check in with advisors and mentors. Maybe you’re in a 9-month graduate program, about to complete the first quarter of your Master’s degree, or heading into the final months of your doctoral program. Maybe you and your advisor or mentor haven’t checked in with each other in a while (because life happens). Whether you are thinking through your goals for winter quarter or needing guidance on your research or next steps in your graduate program, it might be a good idea to schedule a time to meet with your advisor(s). Check in with them via email to see about scheduling a time to meet during early winter quarter. Just scheduling the meeting can give you piece of mind.

We hope you find these tips useful in helping you push through — and thrive — at the end of the quarter!

Managing stress – a lifelong pursuit!

No question about it, being a postdoc is stressful . Academic life is stressful. Your future is uncertain, you are under pressure to produce, you may have family and life circumstances that add to the joy – and the stress – of your experience. Given the data on mental health among graduate students and postdocs, we at the Graduate School encourage open dialogue about how things are going. Check in with each other. And seek help and support when you need it.

Three practices have been shown to make a difference for resilience and well-being:

- Self-care. Sometimes things get so out of whack you have to remind yourself of the basics: enough sleep, healthy food, exercise. All of these things help you think better and perform better. We know there are times you have to push through, but this is a marathon and you have to sustain yourself for the long haul. Find the daily or weekly practice that keeps you on solid ground.

- Connecting with support networks. Seek out people you can be real with. These may be peers, part of your mentoring team, or friends or family from back home. You need a place to speak openly and honestly about how you are doing, a place where you can just be heard. Sometimes online communities can be strong points of connection too. When you find others that feel like you do, it helps you feel less alone and gain more perspective.

- Remembering your purpose. Why are you here? This could be the bigger picture reason you are here – is it love of science? Passion for problem-solving? A desire to make a contribution in the world? Keeping your driving purpose and passion closer to the front of your mind can help you regain focus and motivation when the details or deadlines are rushing in.

One study of postdocs at UT Austin showed that the difference between those who are flourishing and those who are languishing is more positive emotions. It makes sense, right? Positive emotions don’t just happen by themselves – you have to fuel them. Keep things in your life that bring you joy or passion. Check in about things you are grateful for , even – or especially – when times are dark and hard. It all helps keep your positive fire going!

If you or someone you know is struggling with depression or thoughts of self-harm, please visit Samaritans or MentalHealth.gov . The National Suicide Prevention Lifeline is a free, confidential 24-7 service that can provide people in suicidal crisis or emotional distress, or those around them, with support, information and local resources. 1-800-273-TALK (8255).

References:

- The science of resilience & Tips on developing resilience

- Elisabeth Pain (2016). Trainees and mental health: Let’s talk! . Science Magazine.

- Nick Roll (2017). Calling attention to a postdoc’s struggles and suicide . Inside Higher Education.

- Christian T. Gloria & Mary A. Steinhardt (2013). Flourishing, languishing, and depressed postdoctoral fellows: Differences in stress, anxiety, and depressive symptoms . Journal of Postdoctoral Affairs, 3(1).

Digging Deep for the Final Push

Spring is the time of year where several big projects come to the fore. Your to-do lists may include one—or more—of the following: doing a job search, writing up your thesis or capstone summary, continuing work on that dissertation, defending your dissertation, or making arrangements to move with your family after graduation. And by no means are these small tasks. So it’s no wonder why, for different reasons (a task feels too big, intimidating, or the long-term benefits don’t seem readily apparent because of immediate stress or anxiety), we put off doing these projects.

First things first, you are definitely not alone in these feelings. We at Core Programs hear you and encourage you to dig deep for that final push this quarter. Fortunately, there are strategies that can help you do just that. Below are just a few:

Practice self-compassion. One of the biggest reasons we might procrastinate from doing a task is because we judge ourselves internally before we even begin. We might tell ourselves that we “need to be perfect,” or that we are “incompetent” or “undeserving” of a graduate degree, getting that job after graduation, or even success in general. Sometimes these are feelings we internalize, rather than verbal messages. And all of this can stop us in right our tracks. One way to move through negative self-talk is to practice being mindful. When negative thoughts come up, avoid over-identifying with those thoughts and say to yourself, “That’s interesting that I’m thinking that.” If you do judge yourself for not working on one of your projects, that’s a perfect moment to be self-compassionate. You can ask yourself, “What would a caring friend say to me right now?”

Negotiate with yourself. We all have ways we can avoid getting things done. For some of us, it’s spending a few hours on Netflix. For others, it might be reading a book we enjoy, rather than the required reading for a graduate seminar. Still for others, it might be playing video games. And let’s be real—completely denying yourself of a coping mechanism for stress is neither realistic nor the complete answer. Might you meet yourself halfway? For example, can you set aside time in your schedule to write for 15 min., then watch a 30 min. Netflix show—eventually working your way up to 30 min. writing increments? The goal is not to deprive yourself or even judge yourself for avoiding, but to aim for breaking down your projects into manageable tasks.

Be resourceful. One important skill we know you have as graduate students is being resourceful. You have developed this skill over time, and this has helped you tap into your strengths to navigate the university system, your graduate education program, and life in general. It is also perfectly okay to reach out for support when you need it. Check in with a peer, loved one, or member of your thesis or dissertation committee to hold you accountable to breaking down and completing your projects in a realistic manner—and to remind you to reward yourself for each, no matter big or small. You can also schedule an appointment with at a UW writing center, form a writing group, or meet with advisors at your campus career center.

We hope you found these strategies useful, and we know you can do it!

Core Programs Team

Additional Resources

- 5 Strategies for Self-Compassion , PsychCentral

- Procrastination 101: It’s Not About Feeling Like It – How We Can Get Past Feeling Like It , Psychology Today

- Procrastination , The Writing Center at University of North Carolina – Chapel Hill

- Nothing is Certain Except Procrastination and Taxes , PhD Comics

When Things Don’t Go As Planned… Now What?

As we’ve noted in past newsletters, this is the time of year where it seems everyone around you is hitting milestones, getting summer internships or jobs, being awarded fellowships, or graduating. What happens when you find yourself in the midst of setbacks or what feel like roadblocks to your progress?

Maybe you’ve been applying for jobs and haven’t received calls for interviews. Maybe all those fellowship applications are going unanswered. Perhaps your committee or advisor decided to postpone a major exam until the fall quarter, throwing off the timeline of goals you planned for. What now?

We consulted a few sources for advice, including the UW Resilience Lab . First, it’s important to acknowledge and sit with the emotion you’re experiencing (perhaps shame, disappointment, frustration, anger, or all of the above). Recognizing your feelings is an important step for moving forward, otherwise it can be difficult to see through the emotion and be creative about next steps.

Second, talk with trusted individuals about what you are facing. It can feel like everyone around you is successful, but you may be surprised at just how many setbacks and failures are experienced by all of us (including advisors and mentors). Talking with others can help validate your feelings and also help you see additional perspectives on what’s happening–as well as generate more creative ideas about what you can do to adjust, adapt, and move forward.

Business consultant and author Chris Winfield offers these tips to address what to do in the face of setbacks, highlighting how setbacks can be learning and growth opportunities:

– Give yourself time. Lifehacker recommends 24 hours just to let it out. – Avoid making any big decisions, if you feel panicked or overwhelmed. – Make peace with your failures. – Cut yourself some slack (but don’t let go of the rope). – Regain your control.

For more on these tips, see Winfield’s blog post .

Whether you are sailing through the end of the quarter or not sure what’s next for you, we stand with you.

Best Regards,

- What Was Your Greatest Professional Setback and How Did You Deal With It? Three Psychologists Share What They Learned , gradPsych Magazine

- Accepting Setbacks: Surviving When Your Dissertation Changes , GradHacker

- Getting Past Rejection in Graduate School , GradHacker

Work-Life Balance? For Real?

The aspiration of “work-life balance” is often recommended in our everyday lives, but this approach can be met with a sense of dread rather than a sense of hope. Really though, when the demands of work and life seem to be unending, how can we possibly keep it all in “balance”? This can feel so true, especially if the popular analogy to life balance–that of tipping scales–feels all together inaccurate. In actuality, most of us have more than one set of “scales” in our lives (e.g. graduate school, additional jobs on or off campus, family and community commitments, self-care, etc.), and they can often feel like they are in competition with each another. Below are some possible ways to rethink how we might approach working towards work-life integration rather than “balance.”

Integration. Some have talked about “work-life integration.” The idea is that a life worth living is better served if your passions and life commitments are incorporated or expressed in your daily work. This is not to say that we don’t have obligations that we just plain have to do. But this perspective does however allow us to ask ourselves, “During any given work week, do I have opportunities to feed my passions and core commitments in some way?”

Separation. That said, sometimes what refuels you is practicing setting clear boundaries between work and play or being able to volunteer with community groups or organizations that have nothing to do with graduate school work or a job. These are important projects too and—as David Whyte would say—are still integrated in that you are stoking your own fires in service to your work and your engagement in your life.

Reflection. How do you spend your days? Your weeks? Are you happy with your personal mix of commitments and activities? Is the mix serving you and contributing to your ability to be your best self –whether at work or at home with friends and family? Many of us need to do a mental “check-in” on these questions every few months or so, and when necessary, adjust the mix. The aspiration of “work-life balance” is often recommended in our everyday lives, but this approach can be met with a sense of dread rather than a sense of hope. Really though, when the demands of work and life seem to be unending, how can we possibly keep it all in “balance”? This can feel so true, especially if the popular analogy to life balance–that of tipping scales–feels all together inaccurate. In actuality, most of us have more than one set of “scales” in our lives (e.g. graduate school, additional jobs on or off campus, family and community commitments, self-care, etc.), and they can often feel like they are in competition with each another. Below are some possible ways to rethink how we might approach working towards work-life integration rather than “balance.”

Reflection. How do you spend your days? Your weeks? Are you happy with your personal mix of commitments and activities? Is the mix serving you and contributing to your ability to be your best self –whether at work or at home with friends and family? Many of us need to do a mental “check-in” on these questions every few months or so, and when necessary, adjust the mix.

We hope that these strategies for work-life integration are useful to you. Also, please let us know if you have other tips or strategies, and we’ll share them out!

Kelly, Jaye, and Ziyan Acknowledgements

Thanks to Professor Carolyn Allen’s class of first year doctoral students in English, who inspired this reflection.

- Work-Life Balance Vs. Work-Life Integration, Is There Really a Difference? , Rachel Ritlop

- Work Life Integration: The New Norm , Dan Schawbel

- Work/Life Integration , Haas School of Business at UC Berkeley

From an Overworked TA

The class I am a TA for requires 12 hours of student interaction and about half a day of preparing materials. Every week. This is way more than the 20 hours/week that I am paid to do. The instructor knows this and had originally requested twice as many TAs as we have, but the department, being broke, only assigned two of us for this awful job. This particular class is known to be this way, as I have learned from talking to past sufferers. I have been TA-ing for two years now and have noticed a wild disparity in the workload for different classes. My question is: how is this fair? The department pays everyone the same amount, still how is it that some TAs get away with just 4 hours of work while others have to do upwards of 20? Since this is an issue of the department, I don’t know how to proceed. The officials in the department get very defensive when asked this. I don’t want to risk not being considered for future TA positions and am therefore not going to pursue the topic with them, but isn’t this just exploitation of us students by those in power? If the department has no money, they should figure out a better way to do this than exploit two students every quarter (yes, this class is taught every quarter). I am at a loss here and am losing my sanity not finding time to do anything else that actually matters for my Ph.D. Please help. –Anonymous

This week’s answer is provided after consultation from the Labor Relation’s Office .

Yikes. I’m sorry this TA-ship has been such a negative experience for you. Fortunately, you have resources at your disposal to help you resolve some of these issues.

You’ve said you do not wish to pursue these issues with your department. But you should know all academic staff employees are covered under a collective bargaining agreement by UAW Local Union 4121 . If you do want to file a grievance against your department, the Union will help you do that. A Union representative urges Academic Student Employees to remember that addressing workplace concerns is time-sensitive under the Union contract.

Another resource available to you is the Office of the Ombud , which provides a space for members of the UW community to voice their concerns and develop plans for addressing difficult situations. The Ombud is easily accessible, with offices on all three campuses. Students contact the Ombud to discuss a range of issues including TA appointments. They are your go-to for addressing problems with the department’s culture. They’ll advise you on your situation without starting a formal complaint or grievance, and they won’t contact your department about the matter unless you ask them to do so.

Best of luck!

Ask the Grad School Guide is an advice column for all y’all graduate and professional students. Real questions from real students, answered by real people. If the guide doesn’t know the answer, the guide will seek out experts all across campus to address the issue. (Please note: The guide is not a medical doctor, therapist, lawyer or academic advisor, and all advice offered here is for informational purposes only.) Submit a question for the column →

Strengthening Yourself for the Last Leg of the Quarter

We at Core Programs recognize and respect all the hard work you’ve been doing as graduate students during this winter. We know that Winter quarter can be especially challenging given the weather, the darkness, and the usual stressors of navigating a graduate program. The good news is that the light is returning and the quarter is coming to a close! For this final push, we offer a few strategies. Maybe one or more will serve you: