Important Addresses

Harvard College

University Hall Cambridge, MA 02138

Harvard College Admissions Office and Griffin Financial Aid Office

86 Brattle Street Cambridge, MA 02138

Social Links

If you are located in the European Union, Iceland, Liechtenstein or Norway (the “European Economic Area”), please click here for additional information about ways that certain Harvard University Schools, Centers, units and controlled entities, including this one, may collect, use, and share information about you.

- Application Tips

- Navigating Campus

- Preparing for College

- How to Complete the FAFSA

- What to Expect After You Apply

- View All Guides

- Parents & Families

- School Counselors

- Información en Español

- Undergraduate Viewbook

- View All Resources

Search and Useful Links

Search the site, search suggestions, alert: important information.

The Visitor’s Center is closed but our main phone lines and email are operative during normal business hours (9 AM to 5 PM EST).

Last Updated: May 23, 9:24am

Open Alert: Important Information

To thesis or not to thesis.

For many students at Harvard, whether or not to write a thesis is a question that comes up at least once during our four years.

For some concentrations, thesising is mandatory – you know when you declare that you will write a senior thesis, and this often factors into the decision-making process when it comes to declaring that field. For other concentrations, thesising is pretty rare – sometimes slightly discouraged by the department, depending on how well the subject lends itself to independent undergraduate research.

In my concentration, Neuroscience on the Neurobiology track, thesising is absolutely optional. If you want to do research and writing a thesis is something that interests you, you can totally go for it, if you like research but just don’t want to write a super long paper detailing it, that’s cool too, and if you decide that neither is for you, there’s no pressure.

Some Thesis Work From My Thesis That Wasn't Meant To Be

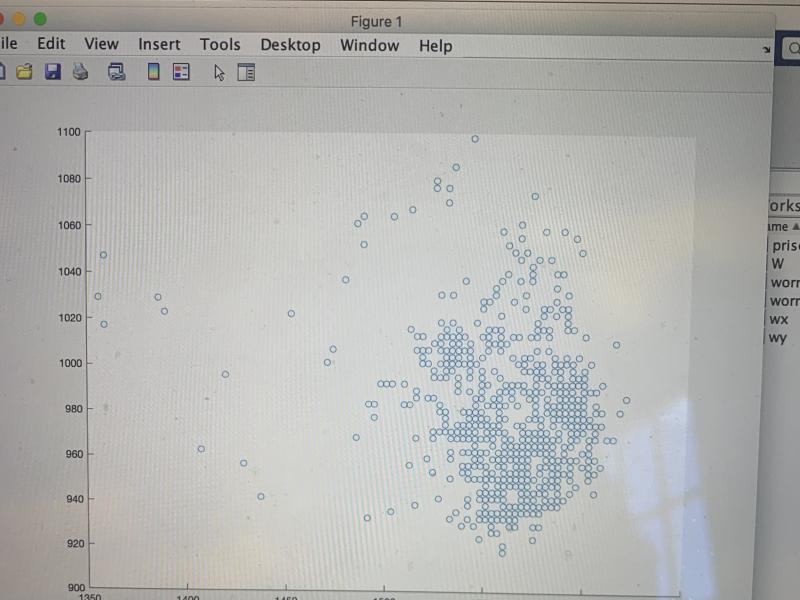

This is from back when I thought I was writing a thesis! Yay data! Claire Hoffman

While this is super nice from the perspective that it allows students to create the undergraduate experiences that work best for them, it can be really confusing if you’re someone like me who can struggle a little with the weight of such a (seemingly) huge decision. So for anyone pondering this question, or thinking they might be in the future, here’s Claire’s patented list of advice:

1. If you really want to thesis, thesis.

If it’s going to be something you’re passionate about, do it! When it comes to spending that much time doing something, if you’re excited about it and feel like it’s something you really want to do, it will be a rewarding experience. Don’t feel discouraged, yes it will be tough, but you can absolutely do this!

2. If you really don’t want to write one, don’t let anyone tell you you should. This is more the camp I fell into myself. I had somehow ended up writing a junior thesis proposal, and suddenly found myself on track to thesis, something I hadn’t fully intended to do. I almost stuck with it, but it mostly would have been because I felt guilty leaving my lab after leading them on- and guilt will not write a thesis for you. I decided to drop at the beginning of senior year, and pandemic or no, it was definitely one of the best decisions I made.

3. This is one of those times where what your friends are doing doesn’t matter. I’m also someone who can (sometimes) be susceptible to peer pressure. Originally, I was worried because so many of my friends were planning to write theses that I would feel left out if I did not also do it. This turned out to be unfounded because one, a bunch of my friends also dropped their theses (senior year in a global pandemic is hard ok?), and two, I realized that even if they were all writing them and loved it, their joy would not mean that I could not be happy NOT writing one. It just wasn’t how I wanted to spend my (limited) time as a senior! On the other hand, if none of your friends are planning to thesis but you really want to, don’t let that stop you. Speaking from experience, they’ll happily hang out with you while you work, and ply you with snacks and fun times during your breaks.

Overall, deciding to write a thesis can be an intensely personal choice. At the end of the day, you just have to do what’s right for you! And as we come up on thesis submission deadlines, good luck to all my amazing senior friends out there who are turning in theses right now.

- Student Life

Claire Class of '21 Alumni

Student Voices

My unusual path to neuroscience, and research.

Raymond Class of '25

How I Organized a Hackathon at Harvard

Kathleen Class of '24

Dear homesick international student at Harvard College

David Class of '25

Yale College Undergraduate Admissions

- A Liberal Arts Education

- Majors & Academic Programs

- Teaching & Advising

- Undergraduate Research

- International Experiences

- Science & Engineering Faculty Features

- Residential Colleges

- Extracurriculars

- Identity, Culture, Faith

- Multicultural Open House

- Virtual Tour

- Bulldogs' Blogs

- First-Year Applicants

- International First-Year Applicants

- QuestBridge First-Year Applicants

- Military Veteran Applicants

- Transfer Applicants

- Eli Whitney: Nontraditional Applicants

- Non-Degree & Alumni Auditing Applicants

- What Yale Looks For

- Putting Together Your Application

- Selecting High School Courses

- Application FAQs

- First-Generation College Students

- Rural and Small Town Students

- Choosing Where to Apply

- Inside the Yale Admissions Office Podcast

- Visit Campus

- Virtual Events

- Connect With Yale Admissions

- The Details

- Estimate Your Cost

- QuestBridge

Search form

Writing a senior thesis: is it worth it.

Before coming to Yale, I thought a thesis was the main argument of a paper. I quickly learned that an undergraduate thesis is about fifty times harder and fifty pages longer than any thesis arguments I wrote in high school. At Yale, every senior has some sort of senior requirement, but thesis projects vary by department. Some departments require students to do a semester-long project, where you write a longer paper (25-35 pages) or expand, through writing, the research you’ve been working on (mostly applies to STEM majors). In some departments you can take two senior seminars and complete a longer project at the end of the semester. And other departments have an option to complete a year-long thesis: you spend your senior year (and in some cases your junior year), intensely researching and writing about a topic you choose or create yourself.

Both my departments––English and Ethnicity, Race, and Migration––offer all three of these options, and each student decides what they think is best for them. As a double major, I had the additional option to write an even longer thesis combining both my majors, but that seemed like way too much work––especially since I would have to take two senior thesis classes at the same time. Instead, I chose a year-long thesis for ER&M that combined my literary interests with various theoretical frameworks and the two senior seminars for English. This spring I’m taking my second seminar. Really, I chose the option to torture myself for a whole year, the end result being a minimum of 50 pages of innovative thinking and writing. I wanted to rise to the challenge, proving to myself I could do it. But there also seemed to be the pressure of “this is what everyone in the major does,” and a “thesis is proof that you actually learned.” Although these sentiments influenced my decision to complete a thesis, I know a long research paper does not validate my education or work as a scholar the last four years. It is not the end all be all.

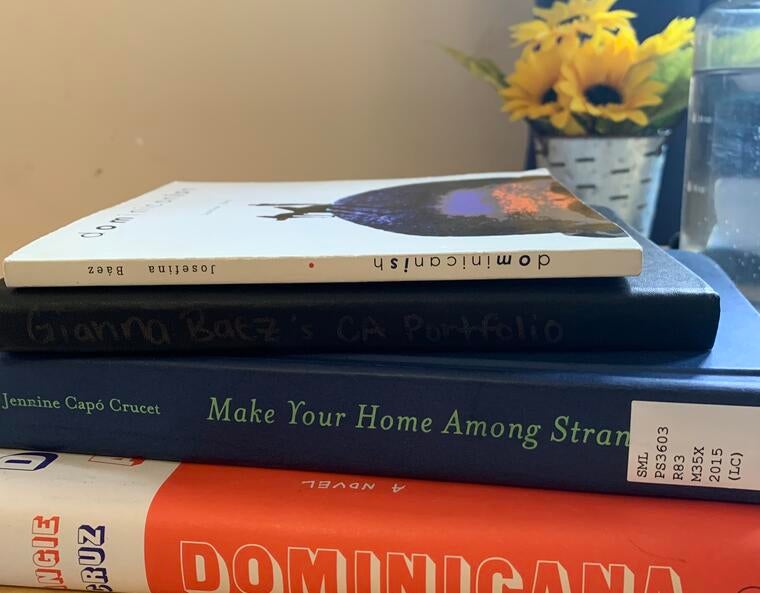

My senior thesis focuses on Caribbean literature - specifically, two novels written by Caribbean women that really look at what it means to come from an immigrant family, to move, and to find yourself in completely new spaces. These experiences are all too relatable to my own life as a second-generation woman of color with immigrant parents enrolled at Yale. In my writing, I focus on how these women make sense of “home” (a very broad and complicated topic, I know), and what their stories tell us about the diasporic experience in general. The project is very personal to me, and I chose it because I wanted to understand my family’s history and their task in making “home” in the U.S., whatever that means. But because it’s so personal, it’s also been really difficult. I’ve experienced a lot of writer’s block or often felt unmotivated and judgmental towards my work. I’ve realized how difficult it is to devote your time and energy to such a long process––not only is it research heavy, but you have to write and rewrite drafts, constantly adjusting to make sure you’re being as clear as possible. Really, writing a thesis is like writing a portion of a book. And that’s crazy! You’re writing two or three whole chapters of academic work as an undergraduate student.

The process is definitely not for everyone, and I’ve certainly thought “Why did I want to do this again?” But what’s really kept me going is the support from my advisors and friends. The ER&M department faculty does an amazing job of providing us mentorship, revisions, and support throughout the process; my advisor has served as my editor but also the person who reminds me most that this work is important, as I often forget that. It also helps to have many friends and people in the major also writing their theses. I’ve found different spaces to just have a thesis study hall or working time, with other people also struggling through. Recently, I submitted my first full draft (note: it was kind of unfinished but it’s okay because it’s a draft!), and it was crazy to think that I wrote 50+ pages, most of which are just my own original thoughts and analysis on two books that have almost no scholarship written about them. It was a relief for sure. This week I will be taking a full break from it, but it reminded me of why I began this journey. It reminded me of all the people who’ve supported me along the way, and how I really couldn’t have done it without them. And now, I’m really looking forward to how good it will feel to turn in my fully written thesis mid-April. I’ve realized that this project shouldn’t be about making it good for Yale’s standard, but for myself, for my family, and for the people who believe in this work as much as I do.

More Posts by Gianna

Senior Bucket List: All the things I had to do before I left Yale/New Haven

Meet Rhythmic Blue!

Medieval Manuscripts and the Beinecke Library

How I Navigated My Double Major

Rating Boba in New Haven

Quarantine Birthdays

Welcome to the Trumbutt!!!!

Yale IMs: Intramural Sports #MOORAH

Reimagining Virtual Relationships

Life @ U of T

My Experience Writing an Undergraduate Thesis

This year, I’ve been working on a really exciting project… my undergraduate thesis! It's my fourth year of university, and I decided to write an undergraduate thesis in Political Science under the supervision of a professor. This week, I wanted to write about why I decided to take a thesis, how I enrolled, and how it’s been going so far!

What is an undergraduate thesis?

An undergraduate thesis is usually a 40-60 page paper written under the supervision of a professor, allowing you to explore a topic of your interest in-depth. I primarily decided to write an undergraduate thesis to prepare me for graduate school - it's allowed me to get started on work I might continue in graduate school, hone my research skills, and test out whether academic research is for me.

How do I write an undergraduate thesis?

To write my undergraduate thesis, I had two options (this may vary depending on what department you're in!). First, I could join the Senior Thesis Seminar offered by department. These seminars group students together who are interested in doing a thesis and teach them research skills and background information. Students then simultaneously complete a thesis under the supervision of a professor. Senior Thesis Seminars often require applications to register in, so if you’re interested in this option, make sure you look into this in your third year of study!

Because I already had a close working relationship with a professor, I opted to instead do the second option, an Independent Study. An Independent Study allows you to work one-on-one with a professor and design whatever course you’re interested in. For either option, you’ll need to know what topic you're interested in writing your thesis on and ask a professor to work with you, so make sure you've figured this out.

How's it going?

So far, I’m about half-way through my thesis and I’m having lots of fun. It’s a great way to get super involved in a topic I care about, and it's preparing me for graduate research much more than any course I’ve taken in my undergraduate degree. I’ve also been enjoying working one-on-one with a professor and learning a lot from them about the field of study I’m interested in, what being an academic researcher is like, and what my position in the field is.

I will say that an undergraduate thesis is a considerable amount of work! It definitely requires more work than all my other classes, and because I’m working so closely with a professor, there’s no way I can slack on it or procrastinate.

Still, if you’re interested in a topic and want to pursue it after your undergraduate studies, I think writing an undergraduate thesis is an incredible opportunity. If you have any questions, feel free to ask in the comments below!

1 comment on “ My Experience Writing an Undergraduate Thesis ”

Is an undergrad thesis mandatory in order to graduate or to get into a Masters program? Also, I’ve heard most Profs only help those with really high grades for their thesis?

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

CAPTCHA Code *

Honors Theses

What this handout is about.

Writing a senior honors thesis, or any major research essay, can seem daunting at first. A thesis requires a reflective, multi-stage writing process. This handout will walk you through those stages. It is targeted at students in the humanities and social sciences, since their theses tend to involve more writing than projects in the hard sciences. Yet all thesis writers may find the organizational strategies helpful.

Introduction

What is an honors thesis.

That depends quite a bit on your field of study. However, all honors theses have at least two things in common:

- They are based on students’ original research.

- They take the form of a written manuscript, which presents the findings of that research. In the humanities, theses average 50-75 pages in length and consist of two or more chapters. In the social sciences, the manuscript may be shorter, depending on whether the project involves more quantitative than qualitative research. In the hard sciences, the manuscript may be shorter still, often taking the form of a sophisticated laboratory report.

Who can write an honors thesis?

In general, students who are at the end of their junior year, have an overall 3.2 GPA, and meet their departmental requirements can write a senior thesis. For information about your eligibility, contact:

- UNC Honors Program

- Your departmental administrators of undergraduate studies/honors

Why write an honors thesis?

Satisfy your intellectual curiosity This is the most compelling reason to write a thesis. Whether it’s the short stories of Flannery O’Connor or the challenges of urban poverty, you’ve studied topics in college that really piqued your interest. Now’s your chance to follow your passions, explore further, and contribute some original ideas and research in your field.

Develop transferable skills Whether you choose to stay in your field of study or not, the process of developing and crafting a feasible research project will hone skills that will serve you well in almost any future job. After all, most jobs require some form of problem solving and oral and written communication. Writing an honors thesis requires that you:

- ask smart questions

- acquire the investigative instincts needed to find answers

- navigate libraries, laboratories, archives, databases, and other research venues

- develop the flexibility to redirect your research if your initial plan flops

- master the art of time management

- hone your argumentation skills

- organize a lengthy piece of writing

- polish your oral communication skills by presenting and defending your project to faculty and peers

Work closely with faculty mentors At large research universities like Carolina, you’ve likely taken classes where you barely got to know your instructor. Writing a thesis offers the opportunity to work one-on-one with a with faculty adviser. Such mentors can enrich your intellectual development and later serve as invaluable references for graduate school and employment.

Open windows into future professions An honors thesis will give you a taste of what it’s like to do research in your field. Even if you’re a sociology major, you may not really know what it’s like to be a sociologist. Writing a sociology thesis would open a window into that world. It also might help you decide whether to pursue that field in graduate school or in your future career.

How do you write an honors thesis?

Get an idea of what’s expected.

It’s a good idea to review some of the honors theses other students have submitted to get a sense of what an honors thesis might look like and what kinds of things might be appropriate topics. Look for examples from the previous year in the Carolina Digital Repository. You may also be able to find past theses collected in your major department or at the North Carolina Collection in Wilson Library. Pay special attention to theses written by students who share your major.

Choose a topic

Ideally, you should start thinking about topics early in your junior year, so you can begin your research and writing quickly during your senior year. (Many departments require that you submit a proposal for an honors thesis project during the spring of your junior year.)

How should you choose a topic?

- Read widely in the fields that interest you. Make a habit of browsing professional journals to survey the “hot” areas of research and to familiarize yourself with your field’s stylistic conventions. (You’ll find the most recent issues of the major professional journals in the periodicals reading room on the first floor of Davis Library).

- Set up appointments to talk with faculty in your field. This is a good idea, since you’ll eventually need to select an advisor and a second reader. Faculty also can help you start narrowing down potential topics.

- Look at honors theses from the past. The North Carolina Collection in Wilson Library holds UNC honors theses. To get a sense of the typical scope of a thesis, take a look at a sampling from your field.

What makes a good topic?

- It’s fascinating. Above all, choose something that grips your imagination. If you don’t, the chances are good that you’ll struggle to finish.

- It’s doable. Even if a topic interests you, it won’t work out unless you have access to the materials you need to research it. Also be sure that your topic is narrow enough. Let’s take an example: Say you’re interested in the efforts to ratify the Equal Rights Amendment in the 1970s and early 1980s. That’s a big topic that probably can’t be adequately covered in a single thesis. You need to find a case study within that larger topic. For example, maybe you’re particularly interested in the states that did not ratify the ERA. Of those states, perhaps you’ll select North Carolina, since you’ll have ready access to local research materials. And maybe you want to focus primarily on the ERA’s opponents. Beyond that, maybe you’re particularly interested in female opponents of the ERA. Now you’ve got a much more manageable topic: Women in North Carolina Who Opposed the ERA in the 1970s and 1980s.

- It contains a question. There’s a big difference between having a topic and having a guiding research question. Taking the above topic, perhaps your main question is: Why did some women in North Carolina oppose the ERA? You will, of course, generate other questions: Who were the most outspoken opponents? White women? Middle-class women? How did they oppose the ERA? Public protests? Legislative petitions? etc. etc. Yet it’s good to start with a guiding question that will focus your research.

Goal-setting and time management

The senior year is an exceptionally busy time for college students. In addition to the usual load of courses and jobs, seniors have the daunting task of applying for jobs and/or graduate school. These demands are angst producing and time consuming If that scenario sounds familiar, don’t panic! Do start strategizing about how to make a time for your thesis. You may need to take a lighter course load or eliminate extracurricular activities. Even if the thesis is the only thing on your plate, you still need to make a systematic schedule for yourself. Most departments require that you take a class that guides you through the honors project, so deadlines likely will be set for you. Still, you should set your own goals for meeting those deadlines. Here are a few suggestions for goal setting and time management:

Start early. Keep in mind that many departments will require that you turn in your thesis sometime in early April, so don’t count on having the entire spring semester to finish your work. Ideally, you’ll start the research process the semester or summer before your senior year so that the writing process can begin early in the fall. Some goal-setting will be done for you if you are taking a required class that guides you through the honors project. But any substantive research project requires a clear timetable.

Set clear goals in making a timetable. Find out the final deadline for turning in your project to your department. Working backwards from that deadline, figure out how much time you can allow for the various stages of production.

Here is a sample timetable. Use it, however, with two caveats in mind:

- The timetable for your thesis might look very different depending on your departmental requirements.

- You may not wish to proceed through these stages in a linear fashion. You may want to revise chapter one before you write chapter two. Or you might want to write your introduction last, not first. This sample is designed simply to help you start thinking about how to customize your own schedule.

Sample timetable

Avoid falling into the trap of procrastination. Once you’ve set goals for yourself, stick to them! For some tips on how to do this, see our handout on procrastination .

Consistent production

It’s a good idea to try to squeeze in a bit of thesis work every day—even if it’s just fifteen minutes of journaling or brainstorming about your topic. Or maybe you’ll spend that fifteen minutes taking notes on a book. The important thing is to accomplish a bit of active production (i.e., putting words on paper) for your thesis every day. That way, you develop good writing habits that will help you keep your project moving forward.

Make yourself accountable to someone other than yourself

Since most of you will be taking a required thesis seminar, you will have deadlines. Yet you might want to form a writing group or enlist a peer reader, some person or people who can help you stick to your goals. Moreover, if your advisor encourages you to work mostly independently, don’t be afraid to ask them to set up periodic meetings at which you’ll turn in installments of your project.

Brainstorming and freewriting

One of the biggest challenges of a lengthy writing project is keeping the creative juices flowing. Here’s where freewriting can help. Try keeping a small notebook handy where you jot down stray ideas that pop into your head. Or schedule time to freewrite. You may find that such exercises “free” you up to articulate your argument and generate new ideas. Here are some questions to stimulate freewriting.

Questions for basic brainstorming at the beginning of your project:

- What do I already know about this topic?

- Why do I care about this topic?

- Why is this topic important to people other than myself

- What more do I want to learn about this topic?

- What is the main question that I am trying to answer?

- Where can I look for additional information?

- Who is my audience and how can I reach them?

- How will my work inform my larger field of study?

- What’s the main goal of my research project?

Questions for reflection throughout your project:

- What’s my main argument? How has it changed since I began the project?

- What’s the most important evidence that I have in support of my “big point”?

- What questions do my sources not answer?

- How does my case study inform or challenge my field writ large?

- Does my project reinforce or contradict noted scholars in my field? How?

- What is the most surprising finding of my research?

- What is the most frustrating part of this project?

- What is the most rewarding part of this project?

- What will be my work’s most important contribution?

Research and note-taking

In conducting research, you will need to find both primary sources (“firsthand” sources that come directly from the period/events/people you are studying) and secondary sources (“secondhand” sources that are filtered through the interpretations of experts in your field.) The nature of your research will vary tremendously, depending on what field you’re in. For some general suggestions on finding sources, consult the UNC Libraries tutorials . Whatever the exact nature of the research you’re conducting, you’ll be taking lots of notes and should reflect critically on how you do that. Too often it’s assumed that the research phase of a project involves very little substantive writing (i.e., writing that involves thinking). We sit down with our research materials and plunder them for basic facts and useful quotations. That mechanical type of information-recording is important. But a more thoughtful type of writing and analytical thinking is also essential at this stage. Some general guidelines for note-taking:

First of all, develop a research system. There are lots of ways to take and organize your notes. Whether you choose to use note cards, computer databases, or notebooks, follow two cardinal rules:

- Make careful distinctions between direct quotations and your paraphrasing! This is critical if you want to be sure to avoid accidentally plagiarizing someone else’s work. For more on this, see our handout on plagiarism .

- Record full citations for each source. Don’t get lazy here! It will be far more difficult to find the proper citation later than to write it down now.

Keeping those rules in mind, here’s a template for the types of information that your note cards/legal pad sheets/computer files should include for each of your sources:

Abbreviated subject heading: Include two or three words to remind you of what this sources is about (this shorthand categorization is essential for the later sorting of your sources).

Complete bibliographic citation:

- author, title, publisher, copyright date, and page numbers for published works

- box and folder numbers and document descriptions for archival sources

- complete web page title, author, address, and date accessed for online sources

Notes on facts, quotations, and arguments: Depending on the type of source you’re using, the content of your notes will vary. If, for example, you’re using US Census data, then you’ll mainly be writing down statistics and numbers. If you’re looking at someone else’s diary, you might jot down a number of quotations that illustrate the subject’s feelings and perspectives. If you’re looking at a secondary source, you’ll want to make note not just of factual information provided by the author but also of their key arguments.

Your interpretation of the source: This is the most important part of note-taking. Don’t just record facts. Go ahead and take a stab at interpreting them. As historians Jacques Barzun and Henry F. Graff insist, “A note is a thought.” So what do these thoughts entail? Ask yourself questions about the context and significance of each source.

Interpreting the context of a source:

- Who wrote/created the source?

- When, and under what circumstances, was it written/created?

- Why was it written/created? What was the agenda behind the source?

- How was it written/created?

- If using a secondary source: How does it speak to other scholarship in the field?

Interpreting the significance of a source:

- How does this source answer (or complicate) my guiding research questions?

- Does it pose new questions for my project? What are they?

- Does it challenge my fundamental argument? If so, how?

- Given the source’s context, how reliable is it?

You don’t need to answer all of these questions for each source, but you should set a goal of engaging in at least one or two sentences of thoughtful, interpretative writing for each source. If you do so, you’ll make much easier the next task that awaits you: drafting.

The dread of drafting

Why do we often dread drafting? We dread drafting because it requires synthesis, one of the more difficult forms of thinking and interpretation. If you’ve been free-writing and taking thoughtful notes during the research phase of your project, then the drafting should be far less painful. Here are some tips on how to get started:

Sort your “evidence” or research into analytical categories:

- Some people file note cards into categories.

- The technologically-oriented among us take notes using computer database programs that have built-in sorting mechanisms.

- Others cut and paste evidence into detailed outlines on their computer.

- Still others stack books, notes, and photocopies into topically-arranged piles.There is not a single right way, but this step—in some form or fashion—is essential!

If you’ve been forcing yourself to put subject headings on your notes as you go along, you’ll have generated a number of important analytical categories. Now, you need to refine those categories and sort your evidence. Everyone has a different “sorting style.”

Formulate working arguments for your entire thesis and individual chapters. Once you’ve sorted your evidence, you need to spend some time thinking about your project’s “big picture.” You need to be able to answer two questions in specific terms:

- What is the overall argument of my thesis?

- What are the sub-arguments of each chapter and how do they relate to my main argument?

Keep in mind that “working arguments” may change after you start writing. But a senior thesis is big and potentially unwieldy. If you leave this business of argument to chance, you may end up with a tangle of ideas. See our handout on arguments and handout on thesis statements for some general advice on formulating arguments.

Divide your thesis into manageable chunks. The surest road to frustration at this stage is getting obsessed with the big picture. What? Didn’t we just say that you needed to focus on the big picture? Yes, by all means, yes. You do need to focus on the big picture in order to get a conceptual handle on your project, but you also need to break your thesis down into manageable chunks of writing. For example, take a small stack of note cards and flesh them out on paper. Or write through one point on a chapter outline. Those small bits of prose will add up quickly.

Just start! Even if it’s not at the beginning. Are you having trouble writing those first few pages of your chapter? Sometimes the introduction is the toughest place to start. You should have a rough idea of your overall argument before you begin writing one of the main chapters, but you might find it easier to start writing in the middle of a chapter of somewhere other than word one. Grab hold where you evidence is strongest and your ideas are clearest.

Keep up the momentum! Assuming the first draft won’t be your last draft, try to get your thoughts on paper without spending too much time fussing over minor stylistic concerns. At the drafting stage, it’s all about getting those ideas on paper. Once that task is done, you can turn your attention to revising.

Peter Elbow, in Writing With Power, suggests that writing is difficult because it requires two conflicting tasks: creating and criticizing. While these two tasks are intimately intertwined, the drafting stage focuses on creating, while revising requires criticizing. If you leave your revising to the last minute, then you’ve left out a crucial stage of the writing process. See our handout for some general tips on revising . The challenges of revising an honors thesis may include:

Juggling feedback from multiple readers

A senior thesis may mark the first time that you have had to juggle feedback from a wide range of readers:

- your adviser

- a second (and sometimes third) faculty reader

- the professor and students in your honors thesis seminar

You may feel overwhelmed by the prospect of incorporating all this advice. Keep in mind that some advice is better than others. You will probably want to take most seriously the advice of your adviser since they carry the most weight in giving your project a stamp of approval. But sometimes your adviser may give you more advice than you can digest. If so, don’t be afraid to approach them—in a polite and cooperative spirit, of course—and ask for some help in prioritizing that advice. See our handout for some tips on getting and receiving feedback .

Refining your argument

It’s especially easy in writing a lengthy work to lose sight of your main ideas. So spend some time after you’ve drafted to go back and clarify your overall argument and the individual chapter arguments and make sure they match the evidence you present.

Organizing and reorganizing

Again, in writing a 50-75 page thesis, things can get jumbled. You may find it particularly helpful to make a “reverse outline” of each of your chapters. That will help you to see the big sections in your work and move things around so there’s a logical flow of ideas. See our handout on organization for more organizational suggestions and tips on making a reverse outline

Plugging in holes in your evidence

It’s unlikely that you anticipated everything you needed to look up before you drafted your thesis. Save some time at the revising stage to plug in the holes in your research. Make sure that you have both primary and secondary evidence to support and contextualize your main ideas.

Saving time for the small stuff

Even though your argument, evidence, and organization are most important, leave plenty of time to polish your prose. At this point, you’ve spent a very long time on your thesis. Don’t let minor blemishes (misspellings and incorrect grammar) distract your readers!

Formatting and final touches

You’re almost done! You’ve researched, drafted, and revised your thesis; now you need to take care of those pesky little formatting matters. An honors thesis should replicate—on a smaller scale—the appearance of a dissertation or master’s thesis. So, you need to include the “trappings” of a formal piece of academic work. For specific questions on formatting matters, check with your department to see if it has a style guide that you should use. For general formatting guidelines, consult the Graduate School’s Guide to Dissertations and Theses . Keeping in mind the caveat that you should always check with your department first about its stylistic guidelines, here’s a brief overview of the final “finishing touches” that you’ll need to put on your honors thesis:

- Honors Thesis

- Name of Department

- University of North Carolina

- These parts of the thesis will vary in format depending on whether your discipline uses MLA, APA, CBE, or Chicago (also known in its shortened version as Turabian) style. Whichever style you’re using, stick to the rules and be consistent. It might be helpful to buy an appropriate style guide. Or consult the UNC LibrariesYear Citations/footnotes and works cited/reference pages citation tutorial

- In addition, in the bottom left corner, you need to leave space for your adviser and faculty readers to sign their names. For example:

Approved by: _____________________

Adviser: Prof. Jane Doe

- This is not a required component of an honors thesis. However, if you want to thank particular librarians, archivists, interviewees, and advisers, here’s the place to do it. You should include an acknowledgments page if you received a grant from the university or an outside agency that supported your research. It’s a good idea to acknowledge folks who helped you with a major project, but do not feel the need to go overboard with copious and flowery expressions of gratitude. You can—and should—always write additional thank-you notes to people who gave you assistance.

- Formatted much like the table of contents.

- You’ll need to save this until the end, because it needs to reflect your final pagination. Once you’ve made all changes to the body of the thesis, then type up your table of contents with the titles of each section aligned on the left and the page numbers on which those sections begin flush right.

- Each page of your thesis needs a number, although not all page numbers are displayed. All pages that precede the first page of the main text (i.e., your introduction or chapter one) are numbered with small roman numerals (i, ii, iii, iv, v, etc.). All pages thereafter use Arabic numerals (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, etc.).

- Your text should be double spaced (except, in some cases, long excerpts of quoted material), in a 12 point font and a standard font style (e.g., Times New Roman). An honors thesis isn’t the place to experiment with funky fonts—they won’t enhance your work, they’ll only distract your readers.

- In general, leave a one-inch inch margin on all sides. However, for the copy of your thesis that will be bound by the library, you need to leave a 1.25-inch margin on the left.

How do I defend my honors thesis?

Graciously, enthusiastically, and confidently. The term defense is scary and misleading—it conjures up images of a military exercise or an athletic maneuver. An academic defense ideally shouldn’t be a combative scene but a congenial conversation about the work’s merits and weaknesses. That said, the defense probably won’t be like the average conversation that you have with your friends. You’ll be the center of attention. And you may get some challenging questions. Thus, it’s a good idea to spend some time preparing yourself. First of all, you’ll want to prepare 5-10 minutes of opening comments. Here’s a good time to preempt some criticisms by frankly acknowledging what you think your work’s greatest strengths and weaknesses are. Then you may be asked some typical questions:

- What is the main argument of your thesis?

- How does it fit in with the work of Ms. Famous Scholar?

- Have you read the work of Mr. Important Author?

NOTE: Don’t get too flustered if you haven’t! Most scholars have their favorite authors and books and may bring one or more of them up, even if the person or book is only tangentially related to the topic at hand. Should you get this question, answer honestly and simply jot down the title or the author’s name for future reference. No one expects you to have read everything that’s out there.

- Why did you choose this particular case study to explore your topic?

- If you were to expand this project in graduate school, how would you do so?

Should you get some biting criticism of your work, try not to get defensive. Yes, this is a defense, but you’ll probably only fan the flames if you lose your cool. Keep in mind that all academic work has flaws or weaknesses, and you can be sure that your professors have received criticisms of their own work. It’s part of the academic enterprise. Accept criticism graciously and learn from it. If you receive criticism that is unfair, stand up for yourself confidently, but in a good spirit. Above all, try to have fun! A defense is a rare opportunity to have eminent scholars in your field focus on YOU and your ideas and work. And the defense marks the end of a long and arduous journey. You have every right to be proud of your accomplishments!

Works consulted

We consulted these works while writing this handout. This is not a comprehensive list of resources on the handout’s topic, and we encourage you to do your own research to find additional publications. Please do not use this list as a model for the format of your own reference list, as it may not match the citation style you are using. For guidance on formatting citations, please see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial . We revise these tips periodically and welcome feedback.

Atchity, Kenneth. 1986. A Writer’s Time: A Guide to the Creative Process from Vision Through Revision . New York: W.W. Norton.

Barzun, Jacques, and Henry F. Graff. 2012. The Modern Researcher , 6th ed. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Cengage Learning.

Elbow, Peter. 1998. Writing With Power: Techniques for Mastering the Writing Process . New York: Oxford University Press.

Graff, Gerald, and Cathy Birkenstein. 2014. “They Say/I Say”: The Moves That Matter in Academic Writing , 3rd ed. New York: W.W. Norton and Company.

Lamott, Anne. 1994. Bird by Bird: Some Instructions on Writing and Life . New York: Pantheon.

Lasch, Christopher. 2002. Plain Style: A Guide to Written English. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Turabian, Kate. 2018. A Manual for Writers of Term Papers, Theses, Dissertations , 9th ed. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout and attribute the source: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Make a Gift

Think of yourself as a member of a jury, listening to a lawyer who is presenting an opening argument. You'll want to know very soon whether the lawyer believes the accused to be guilty or not guilty, and how the lawyer plans to convince you. Readers of academic essays are like jury members: before they have read too far, they want to know what the essay argues as well as how the writer plans to make the argument. After reading your thesis statement, the reader should think, "This essay is going to try to convince me of something. I'm not convinced yet, but I'm interested to see how I might be."

An effective thesis cannot be answered with a simple "yes" or "no." A thesis is not a topic; nor is it a fact; nor is it an opinion. "Reasons for the fall of communism" is a topic. "Communism collapsed in Eastern Europe" is a fact known by educated people. "The fall of communism is the best thing that ever happened in Europe" is an opinion. (Superlatives like "the best" almost always lead to trouble. It's impossible to weigh every "thing" that ever happened in Europe. And what about the fall of Hitler? Couldn't that be "the best thing"?)

A good thesis has two parts. It should tell what you plan to argue, and it should "telegraph" how you plan to argue—that is, what particular support for your claim is going where in your essay.

Steps in Constructing a Thesis

First, analyze your primary sources. Look for tension, interest, ambiguity, controversy, and/or complication. Does the author contradict himself or herself? Is a point made and later reversed? What are the deeper implications of the author's argument? Figuring out the why to one or more of these questions, or to related questions, will put you on the path to developing a working thesis. (Without the why, you probably have only come up with an observation—that there are, for instance, many different metaphors in such-and-such a poem—which is not a thesis.)

Once you have a working thesis, write it down. There is nothing as frustrating as hitting on a great idea for a thesis, then forgetting it when you lose concentration. And by writing down your thesis you will be forced to think of it clearly, logically, and concisely. You probably will not be able to write out a final-draft version of your thesis the first time you try, but you'll get yourself on the right track by writing down what you have.

Keep your thesis prominent in your introduction. A good, standard place for your thesis statement is at the end of an introductory paragraph, especially in shorter (5-15 page) essays. Readers are used to finding theses there, so they automatically pay more attention when they read the last sentence of your introduction. Although this is not required in all academic essays, it is a good rule of thumb.

Anticipate the counterarguments. Once you have a working thesis, you should think about what might be said against it. This will help you to refine your thesis, and it will also make you think of the arguments that you'll need to refute later on in your essay. (Every argument has a counterargument. If yours doesn't, then it's not an argument—it may be a fact, or an opinion, but it is not an argument.)

This statement is on its way to being a thesis. However, it is too easy to imagine possible counterarguments. For example, a political observer might believe that Dukakis lost because he suffered from a "soft-on-crime" image. If you complicate your thesis by anticipating the counterargument, you'll strengthen your argument, as shown in the sentence below.

Some Caveats and Some Examples

A thesis is never a question. Readers of academic essays expect to have questions discussed, explored, or even answered. A question ("Why did communism collapse in Eastern Europe?") is not an argument, and without an argument, a thesis is dead in the water.

A thesis is never a list. "For political, economic, social and cultural reasons, communism collapsed in Eastern Europe" does a good job of "telegraphing" the reader what to expect in the essay—a section about political reasons, a section about economic reasons, a section about social reasons, and a section about cultural reasons. However, political, economic, social and cultural reasons are pretty much the only possible reasons why communism could collapse. This sentence lacks tension and doesn't advance an argument. Everyone knows that politics, economics, and culture are important.

A thesis should never be vague, combative or confrontational. An ineffective thesis would be, "Communism collapsed in Eastern Europe because communism is evil." This is hard to argue (evil from whose perspective? what does evil mean?) and it is likely to mark you as moralistic and judgmental rather than rational and thorough. It also may spark a defensive reaction from readers sympathetic to communism. If readers strongly disagree with you right off the bat, they may stop reading.

An effective thesis has a definable, arguable claim. "While cultural forces contributed to the collapse of communism in Eastern Europe, the disintegration of economies played the key role in driving its decline" is an effective thesis sentence that "telegraphs," so that the reader expects the essay to have a section about cultural forces and another about the disintegration of economies. This thesis makes a definite, arguable claim: that the disintegration of economies played a more important role than cultural forces in defeating communism in Eastern Europe. The reader would react to this statement by thinking, "Perhaps what the author says is true, but I am not convinced. I want to read further to see how the author argues this claim."

A thesis should be as clear and specific as possible. Avoid overused, general terms and abstractions. For example, "Communism collapsed in Eastern Europe because of the ruling elite's inability to address the economic concerns of the people" is more powerful than "Communism collapsed due to societal discontent."

Copyright 1999, Maxine Rodburg and The Tutors of the Writing Center at Harvard University

Search this site

Journalism and communication menu, journalism and communication, five tips for tackling the undergraduate thesis.

By Becky Hoag and Meg Rodgers

Theses aren’t just for graduate students. Many UO School of Journalism and Communication undergrads write theses for the SOJC Honors Program , for Clark’s Honors College or just to gain research experience. Any of them can tell you that thesis-writing takes a lot of work and can be quite daunting.

Wondering how you would even get started on it?

SOJC media studies alum Meg Rodgers ’18 totally understands how you feel. But she made it happen! She spent her senior year writing an undergrad thesis for the Honors College about TV anti-heroines that was selected for the 2018 UO Undergraduate Research Symposium .

Here are a few lessons she learned along the way:

1. Make use of your thesis advisor.

If you don’t have one assigned to you, find one and make that connection as soon as you can.

“They are the experts in their field, and you are learning how to become an expert,” Rodgers said.

She said her advisor, Assistant Professor Erin Hanna, helped her break down her project into doable steps and approach the research process in a smart manner.

2. Dive into the research.

Collect as much knowledge as you can. Even if some of the sources don’t end up in your final reference list, they will all help develop your overall understanding of the topic.

Rodgers found that about one-third of her process was research, one-third was writing and one-third was editing. It might be surprising and a bit nerve-wracking not to write anything down for the first part of the thesis process, but that’s normal. If you start writing too soon, you might find yourself making more assumptions about what you will find, rather than writing about what you actually found.

3. Start citing sources early.

You’ll thank yourself later. Programs like Mendeley or Zotero can help with this. Make sure you know what citation style to use.

4. Break down your thesis into workable sections.

Looking at the whole thing at once can be overwhelming. What are the individual points you want to cover in your paper? Make a list and start checking them off one at a time.

5. Mentally prepare yourself for lots of editing.

Try not to take it personally when your paper gets torn apart. It just means that it’s getting better. Trust the process and be grateful for feedback.

You can do it! And all the work’s definitely worth it. Rodgers found the thesis-writing process helped her learn about her strengths and weaknesses as a researcher and what work environments are best for her. Sometimes the more challenging endeavors can be the most rewarding too.

Becky Hoag is a senior double-majoring in journalism and environmental science (with a marine focus). This is her second year writing for the SOJC Communication Office. This past summer, she worked as an intern at the KQED science desk in San Francisco, producing content for the new program about climate change, “ This Moment on Earth .” She is also a science writer for The Daily Emerald and the student-run environmental magazine Envision Magazine , and a web designer/researcher for marine conservation outreach organization Ocean Everblue . She wants to become an environmental/scientific journalist. You can view her work at beckyhoag.com .

How to write an undergraduate university dissertation

Writing a dissertation is a daunting task, but these tips will help you prepare for all the common challenges students face before deadline day.

Grace McCabe

Writing a dissertation is one of the most challenging aspects of university. However, it is the chance for students to demonstrate what they have learned during their degree and to explore a topic in depth.

In this article, we look at 10 top tips for writing a successful dissertation and break down how to write each section of a dissertation in detail.

10 tips for writing an undergraduate dissertation

1. Select an engaging topic Choose a subject that aligns with your interests and allows you to showcase the skills and knowledge you have acquired through your degree.

2. Research your supervisor Undergraduate students will often be assigned a supervisor based on their research specialisms. Do some research on your supervisor and make sure that they align with your dissertation goals.

3. Understand the dissertation structure Familiarise yourself with the structure (introduction, review of existing research, methodology, findings, results and conclusion). This will vary based on your subject.

4. Write a schedule As soon as you have finalised your topic and looked over the deadline, create a rough plan of how much work you have to do and create mini-deadlines along the way to make sure don’t find yourself having to write your entire dissertation in the final few weeks.

5. Determine requirements Ensure that you know which format your dissertation should be presented in. Check the word count and the referencing style.

6. Organise references from the beginning Maintain an alphabetically arranged reference list or bibliography in the designated style as you do your reading. This will make it a lot easier to finalise your references at the end.

7. Create a detailed plan Once you have done your initial research and have an idea of the shape your dissertation will take, write a detailed essay plan outlining your research questions, SMART objectives and dissertation structure.

8. Keep a dissertation journal Track your progress, record your research and your reading, and document challenges. This will be helpful as you discuss your work with your supervisor and organise your notes.

9. Schedule regular check-ins with your supervisor Make sure you stay in touch with your supervisor throughout the process, scheduling regular meetings and keeping good notes so you can update them on your progress.

10. Employ effective proofreading techniques Ask friends and family to help you proofread your work or use different fonts to help make the text look different. This will help you check for missing sections, grammatical mistakes and typos.

What is a dissertation?

A dissertation is a long piece of academic writing or a research project that you have to write as part of your undergraduate university degree.

It’s usually a long essay in which you explore your chosen topic, present your ideas and show that you understand and can apply what you’ve learned during your studies. Informally, the terms “dissertation” and “thesis” are often used interchangeably.

How do I select a dissertation topic?

First, choose a topic that you find interesting. You will be working on your dissertation for several months, so finding a research topic that you are passionate about and that demonstrates your strength in your subject is best. You want your topic to show all the skills you have developed during your degree. It would be a bonus if you can link your work to your chosen career path, but it’s not necessary.

Second, begin by exploring relevant literature in your field, including academic journals, books and articles. This will help you identify gaps in existing knowledge and areas that may need further exploration. You may not be able to think of a truly original piece of research, but it’s always good to know what has already been written about your chosen topic.

Consider the practical aspects of your chosen topic, ensuring that it is possible within the time frame and available resources. Assess the availability of data, research materials and the overall practicality of conducting the research.

When picking a dissertation topic, you also want to try to choose something that adds new ideas or perspectives to what’s already known in your field. As you narrow your focus, remember that a more targeted approach usually leads to a dissertation that’s easier to manage and has a bigger impact. Be ready to change your plans based on feedback and new information you discover during your research.

How to work with your dissertation supervisor?

Your supervisor is there to provide guidance on your chosen topic, direct your research efforts, and offer assistance and suggestions when you have queries. It’s crucial to establish a comfortable and open line of communication with them throughout the process. Their knowledge can greatly benefit your work. Keep them informed about your progress, seek their advice, and don’t hesitate to ask questions.

1. Keep them updated Regularly tell your supervisor how your work is going and if you’re having any problems. You can do this through emails, meetings or progress reports.

2. Plan meetings Schedule regular meetings with your supervisor. These can be in person or online. These are your time to discuss your progress and ask for help.

3. Share your writing Give your supervisor parts of your writing or an outline. This helps them see what you’re thinking so they can advise you on how to develop it.

5. Ask specific questions When you need help, ask specific questions instead of general ones. This makes it easier for your supervisor to help you.

6. Listen to feedback Be open to what your supervisor says. If they suggest changes, try to make them. It makes your dissertation better and shows you can work together.

7. Talk about problems If something is hard or you’re worried, talk to your supervisor about it. They can give you advice or tell you where to find help.

8. Take charge Be responsible for your work. Let your supervisor know if your plans change, and don’t wait if you need help urgently.

Remember, talking openly with your supervisor helps you both understand each other better, improves your dissertation and ensures that you get the support you need.

How to write a successful research piece at university How to choose a topic for your dissertation Tips for writing a convincing thesis

How do I plan my dissertation?

It’s important to start with a detailed plan that will serve as your road map throughout the entire process of writing your dissertation. As Jumana Labib, a master’s student at the University of Manchester studying digital media, culture and society, suggests: “Pace yourself – definitely don’t leave the entire thing for the last few days or weeks.”

Decide what your research question or questions will be for your chosen topic.

Break that down into smaller SMART (specific, measurable, achievable, relevant and time-bound) objectives.

Speak to your supervisor about any overlooked areas.

Create a breakdown of chapters using the structure listed below (for example, a methodology chapter).

Define objectives, key points and evidence for each chapter.

Define your research approach (qualitative, quantitative or mixed methods).

Outline your research methods and analysis techniques.

Develop a timeline with regular moments for review and feedback.

Allocate time for revision, editing and breaks.

Consider any ethical considerations related to your research.

Stay organised and add to your references and bibliography throughout the process.

Remain flexible to possible reviews or changes as you go along.

A well thought-out plan not only makes the writing process more manageable but also increases the likelihood of producing a high-quality piece of research.

How to structure a dissertation?

The structure can depend on your field of study, but this is a rough outline for science and social science dissertations:

Introduce your topic.

Complete a source or literature review.

Describe your research methodology (including the methods for gathering and filtering information, analysis techniques, materials, tools or resources used, limitations of your method, and any considerations of reliability).

Summarise your findings.

Discuss the results and what they mean.

Conclude your point and explain how your work contributes to your field.

On the other hand, humanities and arts dissertations often take the form of an extended essay. This involves constructing an argument or exploring a particular theory or analysis through the analysis of primary and secondary sources. Your essay will be structured through chapters arranged around themes or case studies.

All dissertations include a title page, an abstract and a reference list. Some may also need a table of contents at the beginning. Always check with your university department for its dissertation guidelines, and check with your supervisor as you begin to plan your structure to ensure that you have the right layout.

How long is an undergraduate dissertation?

The length of an undergraduate dissertation can vary depending on the specific guidelines provided by your university and your subject department. However, in many cases, undergraduate dissertations are typically about 8,000 to 12,000 words in length.

“Eat away at it; try to write for at least 30 minutes every day, even if it feels relatively unproductive to you in the moment,” Jumana advises.

How do I add references to my dissertation?

References are the section of your dissertation where you acknowledge the sources you have quoted or referred to in your writing. It’s a way of supporting your ideas, evidencing what research you have used and avoiding plagiarism (claiming someone else’s work as your own), and giving credit to the original authors.

Referencing typically includes in-text citations and a reference list or bibliography with full source details. Different referencing styles exist, such as Harvard, APA and MLA, each favoured in specific fields. Your university will tell you the preferred style.

Using tools and guides provided by universities can make the referencing process more manageable, but be sure they are approved by your university before using any.

How do I write a bibliography or list my references for my dissertation?

The requirement of a bibliography depends on the style of referencing you need to use. Styles such as OSCOLA or Chicago may not require a separate bibliography. In these styles, full source information is often incorporated into footnotes throughout the piece, doing away with the need for a separate bibliography section.

Typically, reference lists or bibliographies are organised alphabetically based on the author’s last name. They usually include essential details about each source, providing a quick overview for readers who want more information. Some styles ask that you include references that you didn’t use in your final piece as they were still a part of the overall research.

It is important to maintain this list as soon as you start your research. As you complete your research, you can add more sources to your bibliography to ensure that you have a comprehensive list throughout the dissertation process.

How to proofread an undergraduate dissertation?

Throughout your dissertation writing, attention to detail will be your greatest asset. The best way to avoid making mistakes is to continuously proofread and edit your work.

Proofreading is a great way to catch any missing sections, grammatical errors or typos. There are many tips to help you proofread:

Ask someone to read your piece and highlight any mistakes they find.

Change the font so you notice any mistakes.

Format your piece as you go, headings and sections will make it easier to spot any problems.

Separate editing and proofreading. Editing is your chance to rewrite sections, add more detail or change any points. Proofreading should be where you get into the final touches, really polish what you have and make sure it’s ready to be submitted.

Stick to your citation style and make sure every resource listed in your dissertation is cited in the reference list or bibliography.

How to write a conclusion for my dissertation?

Writing a dissertation conclusion is your chance to leave the reader impressed by your work.

Start by summarising your findings, highlighting your key points and the outcome of your research. Refer back to the original research question or hypotheses to provide context to your conclusion.

You can then delve into whether you achieved the goals you set at the beginning and reflect on whether your research addressed the topic as expected. Make sure you link your findings to existing literature or sources you have included throughout your work and how your own research could contribute to your field.

Be honest about any limitations or issues you faced during your research and consider any questions that went unanswered that you would consider in the future. Make sure that your conclusion is clear and concise, and sum up the overall impact and importance of your work.

Remember, keep the tone confident and authoritative, avoiding the introduction of new information. This should simply be a summary of everything you have already said throughout the dissertation.

You may also like

.css-185owts{overflow:hidden;max-height:54px;text-indent:0px;} How to use digital advisers to improve academic writing

How to deal with exam stress

Seeta Bhardwa

5 revision techniques to help you ace exam season (plus 7 more unusual approaches)

Register free and enjoy extra benefits

Understanding and solving intractable resource governance problems.

- In the Press

- Conferences and Talks

- Exploring models of electronic wastes governance in the United States and Mexico: Recycling, risk and environmental justice

- The Collaborative Resource Governance Lab (CoReGovLab)

- Water Conflicts in Mexico: A Multi-Method Approach

- Past projects

- Publications and scholarly output

- Research Interests

- Higher education and academia

- Public administration, public policy and public management research

- Research-oriented blog posts

- Stuff about research methods

- Research trajectory

- Publications

- Developing a Writing Practice

- Outlining Papers

- Publishing strategies

- Writing a book manuscript

- Writing a research paper, book chapter or dissertation/thesis chapter

- Everything Notebook

- Literature Reviews

- Note-Taking Techniques

- Organization and Time Management

- Planning Methods and Approaches

- Qualitative Methods, Qualitative Research, Qualitative Analysis

- Reading Notes of Books

- Reading Strategies

- Teaching Public Policy, Public Administration and Public Management

- My Reading Notes of Books on How to Write a Doctoral Dissertation/How to Conduct PhD Research

- Writing a Thesis (Undergraduate or Masters) or a Dissertation (PhD)

- Reading strategies for undergraduates

- Social Media in Academia

- Resources for Job Seekers in the Academic Market

- Writing Groups and Retreats

- Regional Development (Fall 2015)

- State and Local Government (Fall 2015)

- Public Policy Analysis (Fall 2016)

- Regional Development (Fall 2016)

- Public Policy Analysis (Fall 2018)

- Public Policy Analysis (Fall 2019)

- Public Policy Analysis (Spring 2016)

- POLI 351 Environmental Policy and Politics (Summer Session 2011)

- POLI 352 Comparative Politics of Public Policy (Term 2)

- POLI 375A Global Environmental Politics (Term 2)

- POLI 350A Public Policy (Term 2)

- POLI 351 Environmental Policy and Politics (Term 1)

- POLI 332 Latin American Environmental Politics (Term 2, Spring 2012)

- POLI 350A Public Policy (Term 1, Sep-Dec 2011)

- POLI 375A Global Environmental Politics (Term 1, Sep-Dec 2011)

Identifying what an undergraduate thesis, a Masters’ thesis and a doctoral dissertation entail, and based on that, narrowing the research thesis topic

As I was leaving my office to head to the airport to fly to Mexico City for a workshop on conflicts in extractive industries, I saw the completed printout of Rafael’s dissertation sitting on my desk. Rafael is my soon-to-graduate PhD student. I felt an extreme amount of pride, while also realizing what an enormous amount of work this doctoral dissertation has entailed. Rafa did ethnographic fieldwork for two years analyzing three cases of water conflict, plus a quantitative analysis of a global dataset. I think it’s a testament to his effort that his thesis is already being referenced as a key source for the topic. But reaching the point where we could narrow his topic wasn’t easy. Most of my students have extremely ambitious goals for their undergraduate honors and graduate (Masters and PhD) thesis. Often, I worry if this is because I’m a demanding supervisor and they feel they need to do grandiose, ambitious, all-encompassing projects or because we all face a challenge trying to narrow a topic. I think it’s more the latter than the former. We all tend to want to do research that is broad in scope.

This morning, I mused on Twitter that I found my students to be over-eager and really excited about their research topics, and that they often want to “solve the world’s problems” with their theses/final papers/dissertations. You can read my Twitter thread here and the excellent responses to it.

I need to write a blog post about narrowing topics for a thesis. My experience mentoring and graduating students tells me it’s important. — Dr Raul Pacheco-Vega (@raulpacheco) July 15, 2017

Obviously, there are a few things that I want to highlight about doing a supervised research project that I think are worth remembering, in particular because my students often ask me “so, how narrow is narrow?”. This is a question that necessitates an in-depth discussion between each individual student and their advisors.

Many students come to me wanting to do broad-ranging, ambitious topics. I always tell them to be focused on a narrowly defined project. I find that it’s easier to expand the scope of a project than to narrow it. I also worry when the project is vaguely defined and unclear. There are clear differences between types of research and writing projects.

1. A doctoral dissertation In my view, a doctoral dissertation is a long-term piece of research that demonstrates competency in conducting independent, in-depth scholarly investigations where the domain knowledge is broad, and where the research contribution is original and quite clear. This is challenging for a lot of students because the “what is a contribution” question pops up. I believe you can make theoretical and empirical contributions, and PhD dissertations often have both, but they need at least one of these. One reason why the 3 papers model for a PhD thesis is so popular is because it allows the student to demonstrate competency, depth and originality in a broad range of topics. Depth and breadth of insight are usually tested through doctoral qualifying/comprehensive exams (though I’m well aware of the British model that doesn’t involve comprehensives).

For me, doing a PhD is about showing an ability to conduct competently executed, adequately deep and broad research with a contribution. — Dr Raul Pacheco-Vega (@raulpacheco) July 15, 2017

In my view, two elements are fundamental to the development of a doctoral dissertation: independence and degree of dominion of the knowledge domain. As a doctoral researcher, you should be able to conduct your research independently, even if the advisor is there to guide you. You should also have covered the literature broadly and deeply enough. At the doctoral thesis’ defence, it should be obvious that the student has now become the master at the topic.

2 key elements in PhD-level work are independence & domain knowledge. You *have* to independently become THE expert at topic & teach ME. — Dr Raul Pacheco-Vega (@raulpacheco) July 15, 2017

The SOCK test (specific, original contribution to knowledge) is a good one that should be applied to doctoral theses all around.

Our chair always pushed for a SOCK (specific, original contribution to knowledge). — Arne Wackenhut (@AWackenhut) July 15, 2017

2. A Masters’ thesis In my view, a Masters’ thesis (as its name indicates) is supposed to demonstrate mastery. We may define mastery in different ways, but I do believe you need to show that you’re competent at investigating a particular research topic and at undertaking theoretical or empirical work that moves our understanding of a phenomenon forward. For example, for me, a Masters-level thesis is an empirical examination of patterns of bottled water consumption. Or a collated and analysed set of stories about consuming bottled water and the rationales behind them (both of these are Masters’ theses of two of my students).

I get Masters’ students wanting to do PhD-level research with fewer funds and shorter time frames. You can’t do that. Narrow the topic! — Dr Raul Pacheco-Vega (@raulpacheco) July 15, 2017

The problem with Masters’ students wanting to do PhD-level kind of work (or too broad of a project) is that they are often given a shorter time frame, which often requires them to rush through courses and do their thesis under financial duress and time constraints. Thus the importance of narrowing the research topic.

It’s also important that the Masters’ student supervisor/advisor is realistic in terms of expectations and ability to achieve goals within the shortened time frame, and often within tight budgets or the risk of facing a shortage of funds.

Important conversation for those of us teaching/learning in masters level programs. Alignment of expectations, pedagogy is key. https://t.co/nUs3dC03Zg — pdkh® (@phalcon7) July 15, 2017

While it’s important that the topic is adequately covered and that the contribution is original, it doesn’t need to be a grandiose or far-ranging contribution. As Dr. Prieto indicates in her response to my tweet, an in-depth case study or an application of a theory to a different dataset could be an original contribution.

Master’s theses should make an original scholarly contribution too. Just within a narrower scope, as you say. — Laura R. Prieto (@Laura_R_Prieto) July 15, 2017

A good, narrow thesis topic is often a case study, w rich context. Again original but publishers tend to want wider scope. — Laura R. Prieto (@Laura_R_Prieto) July 15, 2017

Masters student this year… I want to examine why stock prices are volatile — brian lucey (@brianmlucey) July 15, 2017

It IS important that the topic of the Masters thesis is narrow in scope, but competently executed.

3. An undergraduate (honors) thesis.

I teach in the undergraduate program in public policy at CIDE. My undergraduate students tend to be REALLY ambitious and want to change the world, and I am grateful for that. But that’s not the goal with their undergraduate theses. For me, an undergraduate thesis can be a systematic literature review, an application of a research technique to an interesting topic, a test of a theory or an empirically-inclined paper using data that are often not available. An undergraduate thesis doesn’t necessitate an original contribution in the sense of a Masters’ or PhD- level one.

There are various reasons why undergraduate students (or even graduate ones) want to do very broad topics, resulting in thesis that are not narrow enough.

My experience has been that the bigger hurdle is emotional – “narrowing” feels like giving up on ideas that are important. — Corrine McConnaughy (@cmMcConnaughy) July 15, 2017

But as discussed above, you can do a perfectly competent undergraduate honours thesis just by doing a systematic policy analysis, a solid literature review, an interesting exploration of a known quantitative or qualitative research technique, an empirical (or descriptive) case study, etc.

4. A seminar research paper Seminar research papers tend to also be overly ambitious, as Dr. McConnaughy indicates below.

Could add the layer of seminar paper, too. You can’t write a thesis as a seminar paper! I find resistance to “narrowing” as if it is bad. No — Corrine McConnaughy (@cmMcConnaughy) July 15, 2017

What I have done in my seminar courses is create a blueprint, a template for students to do their final papers. That way, I define the scope of the project in very narrow terms, I give them the tools they need to apply and I let them do the empirical testing or the archival or secondary source searches (though some students of mine even collect primary data!)

A few other things to consider and pieces of advice to remember:

Best thesis-writing advice I got when I was in grad school was, “remember this is *not* your life’s work; it’s just your way in.” — Chester Scoville (@ChesterScoville) July 15, 2017

Students need to remember that a thesis is also an administrative exercise. Get it done and then move on to interesting work. — Adam Wellstead (@amwellstead) July 15, 2017

Narrowing the research topic should entail a conversation with your advisor. You can start reading broadly, but you should be able to pare down the topic asking a few questions such as:

- Can this study be undertaken within a reasonable (12 months/24 months) time frame?

- Do I have the necessary funding for the entire period of time that this study will require me to do work/fieldwork/laboratory experiments?

- Am I trying to do more cases than needed to prove the hypotheses I’m testing or answer the research questions I’ve posited?

- Are the research questions posited aligned with time, budgetary and resource constraints?