Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Academic writing

- A step-by-step guide to the writing process

The Writing Process | 5 Steps with Examples & Tips

Published on April 24, 2020 by Jack Caulfield . Revised on December 8, 2023.

Good academic writing requires effective planning, drafting, and revision.

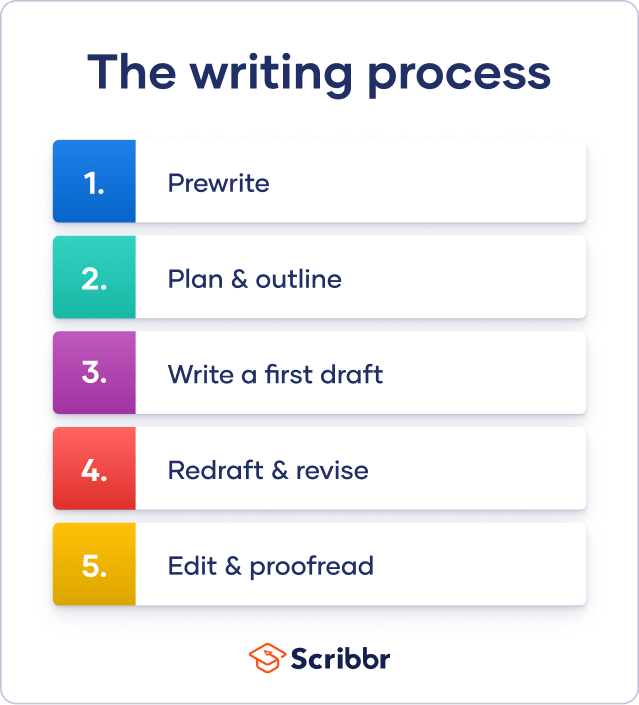

The writing process looks different for everyone, but there are five basic steps that will help you structure your time when writing any kind of text.

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

Table of contents

Step 1: prewriting, step 2: planning and outlining, step 3: writing a first draft, step 4: redrafting and revising, step 5: editing and proofreading, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about the writing process.

Before you start writing, you need to decide exactly what you’ll write about and do the necessary research.

Coming up with a topic

If you have to come up with your own topic for an assignment, think of what you’ve covered in class— is there a particular area that intrigued, interested, or even confused you? Topics that left you with additional questions are perfect, as these are questions you can explore in your writing.

The scope depends on what type of text you’re writing—for example, an essay or a research paper will be less in-depth than a dissertation topic . Don’t pick anything too ambitious to cover within the word count, or too limited for you to find much to say.

Narrow down your idea to a specific argument or question. For example, an appropriate topic for an essay might be narrowed down like this:

Doing the research

Once you know your topic, it’s time to search for relevant sources and gather the information you need. This process varies according to your field of study and the scope of the assignment. It might involve:

- Searching for primary and secondary sources .

- Reading the relevant texts closely (e.g. for literary analysis ).

- Collecting data using relevant research methods (e.g. experiments , interviews or surveys )

From a writing perspective, the important thing is to take plenty of notes while you do the research. Keep track of the titles, authors, publication dates, and relevant quotations from your sources; the data you gathered; and your initial analysis or interpretation of the questions you’re addressing.

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

Especially in academic writing , it’s important to use a logical structure to convey information effectively. It’s far better to plan this out in advance than to try to work out your structure once you’ve already begun writing.

Creating an essay outline is a useful way to plan out your structure before you start writing. This should help you work out the main ideas you want to focus on and how you’ll organize them. The outline doesn’t have to be final—it’s okay if your structure changes throughout the writing process.

Use bullet points or numbering to make your structure clear at a glance. Even for a short text that won’t use headings, it’s useful to summarize what you’ll discuss in each paragraph.

An outline for a literary analysis essay might look something like this:

- Describe the theatricality of Austen’s works

- Outline the role theater plays in Mansfield Park

- Introduce the research question: How does Austen use theater to express the characters’ morality in Mansfield Park ?

- Discuss Austen’s depiction of the performance at the end of the first volume

- Discuss how Sir Bertram reacts to the acting scheme

- Introduce Austen’s use of stage direction–like details during dialogue

- Explore how these are deployed to show the characters’ self-absorption

- Discuss Austen’s description of Maria and Julia’s relationship as polite but affectionless

- Compare Mrs. Norris’s self-conceit as charitable despite her idleness

- Summarize the three themes: The acting scheme, stage directions, and the performance of morals

- Answer the research question

- Indicate areas for further study

Once you have a clear idea of your structure, it’s time to produce a full first draft.

This process can be quite non-linear. For example, it’s reasonable to begin writing with the main body of the text, saving the introduction for later once you have a clearer idea of the text you’re introducing.

To give structure to your writing, use your outline as a framework. Make sure that each paragraph has a clear central focus that relates to your overall argument.

Hover over the parts of the example, from a literary analysis essay on Mansfield Park , to see how a paragraph is constructed.

The character of Mrs. Norris provides another example of the performance of morals in Mansfield Park . Early in the novel, she is described in scathing terms as one who knows “how to dictate liberality to others: but her love of money was equal to her love of directing” (p. 7). This hypocrisy does not interfere with her self-conceit as “the most liberal-minded sister and aunt in the world” (p. 7). Mrs. Norris is strongly concerned with appearing charitable, but unwilling to make any personal sacrifices to accomplish this. Instead, she stage-manages the charitable actions of others, never acknowledging that her schemes do not put her own time or money on the line. In this way, Austen again shows us a character whose morally upright behavior is fundamentally a performance—for whom the goal of doing good is less important than the goal of seeming good.

When you move onto a different topic, start a new paragraph. Use appropriate transition words and phrases to show the connections between your ideas.

The goal at this stage is to get a draft completed, not to make everything perfect as you go along. Once you have a full draft in front of you, you’ll have a clearer idea of where improvement is needed.

Give yourself a first draft deadline that leaves you a reasonable length of time to revise, edit, and proofread before the final deadline. For a longer text like a dissertation, you and your supervisor might agree on deadlines for individual chapters.

Now it’s time to look critically at your first draft and find potential areas for improvement. Redrafting means substantially adding or removing content, while revising involves making changes to structure and reformulating arguments.

Evaluating the first draft

It can be difficult to look objectively at your own writing. Your perspective might be positively or negatively biased—especially if you try to assess your work shortly after finishing it.

It’s best to leave your work alone for at least a day or two after completing the first draft. Come back after a break to evaluate it with fresh eyes; you’ll spot things you wouldn’t have otherwise.

When evaluating your writing at this stage, you’re mainly looking for larger issues such as changes to your arguments or structure. Starting with bigger concerns saves you time—there’s no point perfecting the grammar of something you end up cutting out anyway.

Right now, you’re looking for:

- Arguments that are unclear or illogical.

- Areas where information would be better presented in a different order.

- Passages where additional information or explanation is needed.

- Passages that are irrelevant to your overall argument.

For example, in our paper on Mansfield Park , we might realize the argument would be stronger with more direct consideration of the protagonist Fanny Price, and decide to try to find space for this in paragraph IV.

For some assignments, you’ll receive feedback on your first draft from a supervisor or peer. Be sure to pay close attention to what they tell you, as their advice will usually give you a clearer sense of which aspects of your text need improvement.

Redrafting and revising

Once you’ve decided where changes are needed, make the big changes first, as these are likely to have knock-on effects on the rest. Depending on what your text needs, this step might involve:

- Making changes to your overall argument.

- Reordering the text.

- Cutting parts of the text.

- Adding new text.

You can go back and forth between writing, redrafting and revising several times until you have a final draft that you’re happy with.

Think about what changes you can realistically accomplish in the time you have. If you are running low on time, you don’t want to leave your text in a messy state halfway through redrafting, so make sure to prioritize the most important changes.

Editing focuses on local concerns like clarity and sentence structure. Proofreading involves reading the text closely to remove typos and ensure stylistic consistency. You can check all your drafts and texts in minutes with an AI proofreader .

Editing for grammar and clarity

When editing, you want to ensure your text is clear, concise, and grammatically correct. You’re looking out for:

- Grammatical errors.

- Ambiguous phrasings.

- Redundancy and repetition .

In your initial draft, it’s common to end up with a lot of sentences that are poorly formulated. Look critically at where your meaning could be conveyed in a more effective way or in fewer words, and watch out for common sentence structure mistakes like run-on sentences and sentence fragments:

- Austen’s style is frequently humorous, her characters are often described as “witty.” Although this is less true of Mansfield Park .

- Austen’s style is frequently humorous. Her characters are often described as “witty,” although this is less true of Mansfield Park .

To make your sentences run smoothly, you can always use a paraphrasing tool to rewrite them in a clearer way.

Proofreading for small mistakes and typos

When proofreading, first look out for typos in your text:

- Spelling errors.

- Missing words.

- Confused word choices .

- Punctuation errors .

- Missing or excess spaces.

Use a grammar checker , but be sure to do another manual check after. Read through your text line by line, watching out for problem areas highlighted by the software but also for any other issues it might have missed.

For example, in the following phrase we notice several errors:

- Mary Crawfords character is a complicate one and her relationships with Fanny and Edmund undergoes several transformations through out the novel.

- Mary Crawford’s character is a complicated one, and her relationships with both Fanny and Edmund undergo several transformations throughout the novel.

Proofreading for stylistic consistency

There are several issues in academic writing where you can choose between multiple different standards. For example:

- Whether you use the serial comma .

- Whether you use American or British spellings and punctuation (you can use a punctuation checker for this).

- Where you use numerals vs. words for numbers.

- How you capitalize your titles and headings.

Unless you’re given specific guidance on these issues, it’s your choice which standards you follow. The important thing is to consistently follow one standard for each issue. For example, don’t use a mixture of American and British spellings in your paper.

Additionally, you will probably be provided with specific guidelines for issues related to format (how your text is presented on the page) and citations (how you acknowledge your sources). Always follow these instructions carefully.

If you want to know more about AI for academic writing, AI tools, or fallacies make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples or go directly to our tools!

- Ad hominem fallacy

- Post hoc fallacy

- Appeal to authority fallacy

- False cause fallacy

- Sunk cost fallacy

- Deep learning

- Generative AI

- Machine learning

- Reinforcement learning

- Supervised vs. unsupervised learning

(AI) Tools

- Grammar Checker

- Paraphrasing Tool

- Text Summarizer

- AI Detector

- Plagiarism Checker

- Citation Generator

Revising, proofreading, and editing are different stages of the writing process .

- Revising is making structural and logical changes to your text—reformulating arguments and reordering information.

- Editing refers to making more local changes to things like sentence structure and phrasing to make sure your meaning is conveyed clearly and concisely.

- Proofreading involves looking at the text closely, line by line, to spot any typos and issues with consistency and correct them.

Whether you’re publishing a blog, submitting a research paper , or even just writing an important email, there are a few techniques you can use to make sure it’s error-free:

- Take a break : Set your work aside for at least a few hours so that you can look at it with fresh eyes.

- Proofread a printout : Staring at a screen for too long can cause fatigue – sit down with a pen and paper to check the final version.

- Use digital shortcuts : Take note of any recurring mistakes (for example, misspelling a particular word, switching between US and UK English , or inconsistently capitalizing a term), and use Find and Replace to fix it throughout the document.

If you want to be confident that an important text is error-free, it might be worth choosing a professional proofreading service instead.

If you’ve gone over the word limit set for your assignment, shorten your sentences and cut repetition and redundancy during the editing process. If you use a lot of long quotes , consider shortening them to just the essentials.

If you need to remove a lot of words, you may have to cut certain passages. Remember that everything in the text should be there to support your argument; look for any information that’s not essential to your point and remove it.

To make this process easier and faster, you can use a paraphrasing tool . With this tool, you can rewrite your text to make it simpler and shorter. If that’s not enough, you can copy-paste your paraphrased text into the summarizer . This tool will distill your text to its core message.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Caulfield, J. (2023, December 08). The Writing Process | 5 Steps with Examples & Tips. Scribbr. Retrieved June 26, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/academic-writing/writing-process/

Is this article helpful?

Jack Caulfield

Other students also liked, how to create a structured research paper outline | example, quick guide to proofreading | what, why and how to proofread, academic paragraph structure | step-by-step guide & examples, get unlimited documents corrected.

✔ Free APA citation check included ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

Do You Know The 7 Steps Of The Writing Process?

How much do you know about the different stages of the writing process? Even if you’ve been writing for years, your understanding of the processes of writing may be limited to writing, editing, and publishing.

It’s not your fault. Much of the writing instruction in school and online focus most heavily on those three critical steps.

Important as they are, though, there’s more to creating a successful book than those three. And as a writer, you need to know.

The 7 Steps of the Writing Process

Read on to familiarize yourself with the seven writing process steps most writers go through — at least to some extent. The more you know each step and its importance, the more you can do it justice before moving on to the next.

1. Planning or Prewriting

This is probably the most fun part of the writing process. Here’s where an idea leads to a brainstorm, which leads to an outline (or something like it).

Whether you’re a plotter, a pantser, or something in between, every writer has some idea of what they want to accomplish with their writing. This is the goal you want the final draft to meet.

With both fiction and nonfiction , every author needs to identify two things for each writing project:

- Intended audience = “For whom am I writing this?”

- Chosen purpose = “What do I want this piece of writing to accomplish?”

In other words, you start with the endpoint in mind. You look at your writing project the way your audience would. And you keep its purpose foremost at every step.

From planning, we move to the next fun stage.

2. Drafting (or Writing the First Draft)

There’s a reason we don’t just call this the “rough draft,” anymore. Every first draft is rough. And you’ll probably have more than one rough draft before you’re ready to publish.

For your first draft, you’ll be freewriting your way from beginning to end, drawing from your outline, or a list of main plot points, depending on your particular process.

To get to the finish line for this first draft, it helps to set word count goals for each day or each week and to set a deadline based on those word counts and an approximate idea of how long this writing project should be.

Seeing that deadline on your calendar can help keep you motivated to meet your daily and weekly targets. It also helps to reserve a specific time of day for writing.

Another useful tool is a Pomodoro timer, which you can set for 20-25 minute bursts with short breaks between them — until you reach your word count for the day.

3. Sharing Your First Draft

Once you’ve finished your first draft, it’s time to take a break from it. The next time you sit down to read through it, you’ll be more objective than you would be right after typing “The End” or logging the final word count.

It’s also time to let others see your baby, so they can provide feedback on what they like and what isn’t working for them.

You can find willing readers in a variety of places:

- Social media groups for writers

- Social media groups for readers of a particular genre

- Your email list (if you have one)

- Local and online writing groups and forums

This is where you’ll get a sense of whether your first draft is fulfilling its original purpose and whether it’s likely to appeal to its intended audience.

You’ll also get some feedback on whether you use certain words too often, as well as whether your writing is clear and enjoyable to read.

4. Evaluating Your Draft

Here’s where you do a full evaluation of your first draft, taking into account the feedback you’ve received, as well as what you’re noticing as you read through it. You’ll mark any mistakes with grammar or mechanics.

And you’ll look for the answer to important questions:

- Is this piece of writing effective/ Does it fulfill its purpose?

- Do my readers like my main character? (Fiction)

- Does the story make sense and satisfy the reader? (Fiction)

- Does it answer the questions presented at the beginning? ( Nonfiction )

- Is it written in a way the intended audience can understand and enjoy?

Once you’ve thoroughly evaluated your work, you can move on to the revision stage and create the next draft.

More Related Articles

How To Create An Em Dash Or Hyphen

Are You Ready To Test Your Proofreading Skills?

How To Write A Book For Kindle About Your Expertise Or Passion

5. Revising Your Content

Revising and editing get mixed up a lot, but they’re not the same thing.

With revising, you’re making changes to the content based on the feedback you’ve received and on your own evaluation of the previous draft.

- To correct structural problems in your book or story

- To find loose ends and tie them up (Fiction)

- To correct unhelpful deviations from genre norms (Fiction)

- To add or remove content to improve flow and/or usefulness

You revise your draft to create a new one that comes closer to achieving your original goals for it. Your newest revision is your newest draft.

If you’re hiring a professional editor for the next step, you’ll likely be doing more revision after they’ve provided their own feedback on the draft you send them.

Editing is about eliminating errors in your (revised) content that can affect its accuracy, clarity, and readability.

By the time editing is done, your writing should be free of the following:

- Grammatical errors

- Punctuation/mechanical and spelling errors

- Misquoted content

- Missing (necessary) citations and source info

- Factual errors

- Awkward phrasing

- Unnecessary repetition

Good editing makes your work easier and more enjoyable to read. A well-edited book is less likely to get negative reviews titled, “Needs editing.” And when it comes to books, it’s best to go beyond self-editing and find a skilled professional.

A competent editor will be more objective about your work and is more likely to catch mistakes you don’t see because your eyes have learned to compensate for them.

7. Publishing Your Final Product

Here’s where you take your final draft — the final product of all the previous steps — and prepare it for publication.

Not only will it need to be formatted (for ebook, print, and audiobook), but you’ll also need a cover that will appeal to your intended audience as much as your content will.

Whether you budget for these things or not depends on the path you choose to publish your book:

- Traditional Publishing — where the publishing house provides editing, formatting, and cover design, as well as some marketing

- Self-Publishing — where you contract with professionals and pay for editing, formatting, and cover design.

- Self-Publishing with a Publishing Company — where you pay the company to provide editing, formatting, and cover design using their in-house professionals.

And once your book is live and ready to buy, it’s time to make it more visible to your intended audience. Otherwise, it would fail in its purpose, too.

Are you ready to begin 7 steps of the writing process?

Now that you’re familiar with the writing process examples in this post, how do you envision your own process?

While it should include the seven steps described here, it’ll also include personal preferences of your own — like the following:

- Writing music and other ambient details

- Writing schedule

- Word count targets and time frames

The more you learn about the finer details of the writing process, the more likely you are to create content your readers will love. And the more likely they are to find it.

Wherever you are in the process, our goal here is to provide content that will help you make the most of it.

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

- Mailing List

- Search Search

Username or Email Address

Remember Me

Resources for Writers: The Writing Process

Writing is a process that involves at least four distinct steps: prewriting, drafting, revising, and editing. It is known as a recursive process. While you are revising, you might have to return to the prewriting step to develop and expand your ideas.

- Prewriting is anything you do before you write a draft of your document. It includes thinking, taking notes, talking to others, brainstorming, outlining, and gathering information (e.g., interviewing people, researching in the library, assessing data).

- Although prewriting is the first activity you engage in, generating ideas is an activity that occurs throughout the writing process.

- Drafting occurs when you put your ideas into sentences and paragraphs. Here you concentrate upon explaining and supporting your ideas fully. Here you also begin to connect your ideas. Regardless of how much thinking and planning you do, the process of putting your ideas in words changes them; often the very words you select evoke additional ideas or implications.

- Don’t pay attention to such things as spelling at this stage.

- This draft tends to be writer-centered: it is you telling yourself what you know and think about the topic.

- Revision is the key to effective documents. Here you think more deeply about your readers’ needs and expectations. The document becomes reader-centered. How much support will each idea need to convince your readers? Which terms should be defined for these particular readers? Is your organization effective? Do readers need to know X before they can understand Y?

- At this stage you also refine your prose, making each sentence as concise and accurate as possible. Make connections between ideas explicit and clear.

- Check for such things as grammar, mechanics, and spelling. The last thing you should do before printing your document is to spell check it.

- Don’t edit your writing until the other steps in the writing process are complete.

The Writing Process

Making expository writing less stressful, more efficient, and more enlightening, search form, you are here, what is a writing process.

“Writing is easy. You just open your veins and bleed.” — Red Smith, Sportswriter

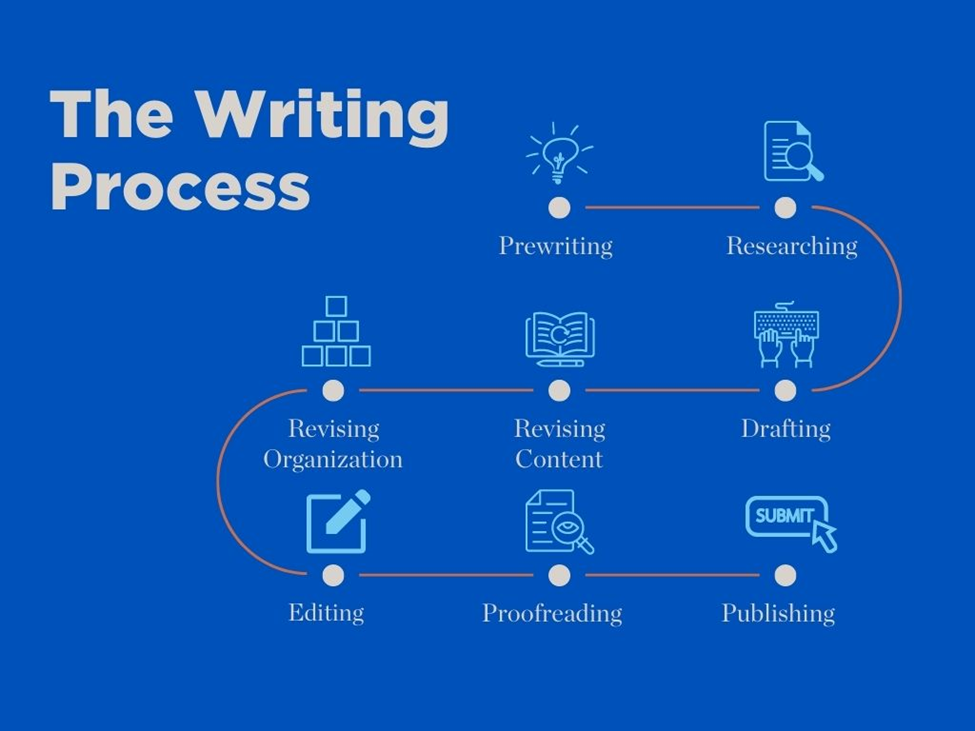

As you might expect, process writing means approaching a writing task according to a formalized series of concrete, discrete steps. Although different versions of the writing process can be found—some with as few as three steps or phases, others with as many as eight—they generally move from a writer-oriented phase of pre-writing through drafting to reader-oriented revising and editing. I generally find that the one I will present below, comprising five steps, is specific enough to make the important steps separate and yet not so complex as to be daunting.

Why even use a formal writing process, though? What can it offer you that the kind of informal processes people typically use don't? Continue.

- Enroll & Pay

- Prospective Students

- Current Students

- Degree Programs

The Writing Process

The writing process is something that no two people do the same way. There is no "right way" or "wrong way" to write. It can be a very messy and fluid process, and the following is only a representation of commonly used steps. Remember you can come to the Writing Center for assistance at any stage in this process.

Steps of the Writing Process

Step 1: Prewriting

Think and Decide

- Make sure you understand your assignment. See Research Papers or Essays

- Decide on a topic to write about. See Prewriting Strategies and Narrow your Topic

- Consider who will read your work. See Audience and Voice

- Brainstorm ideas about the subject and how those ideas can be organized. Make an outline. See Outlines

Step 2: Research (if needed)

- List places where you can find information.

- Do your research. See the many KU Libraries resources and helpful guides

- Evaluate your sources. See Evaluating Sources and Primary vs. Secondary Sources

- Make an outline to help organize your research. See Outlines

Step 3: Drafting

- Write sentences and paragraphs even if they are not perfect.

- Create a thesis statement with your main idea. See Thesis Statements

- Put the information you researched into your essay accurately without plagiarizing. Remember to include both in-text citations and a bibliographic page. See Incorporating References and Paraphrase and Summary

- Read what you have written and judge if it says what you mean. Write some more.

- Read it again.

- Write some more.

- Write until you have said everything you want to say about the topic.

Step 4: Revising

Make it Better

- Read what you have written again. See Revising Content and Revising Organization

- Rearrange words, sentences, or paragraphs into a clear and logical order.

- Take out or add parts.

- Do more research if you think you should.

- Replace overused or unclear words.

- Read your writing aloud to be sure it flows smoothly. Add transitions.

Step 5: Editing and Proofreading

Make it Correct

- Be sure all sentences are complete. See Editing and Proofreading

- Correct spelling, capitalization, and punctuation.

- Change words that are not used correctly or are unclear.

- APA Formatting

- Chicago Style Formatting

- MLA Formatting

- Have someone else check your work.

The Writing Process: A Seven-Step Approach for Every Writer

Aaron Burden / Unsplash.com

Main Writing Process Takeaways:

- Writing process refers to a series of steps that a writer must follow to complete a piece of writing.

- Having a writing process is essential to produce a wide range of content.

- Breaking down your text into different stages could ultimately improve content quality.

- A writing process or method includes the following stages: planning, drafting, sharing, evaluating, revising, editing, and publishing.

- The prewriting stage is the most critical stage of the writing process .

We all follow a writing process when creating an article or any written content. In most cases, this process becomes a routine that comes naturally rather than a step-by-step guide.

However, following a step-by-step writing process can come in handy, especially when dealing with challenging pieces. In this post, we will discuss the seven-stage writing method that you can use for writing high quality content.

What is the Writing Process?

Writing process refers to a series of steps that you must follow in order for you to complete a piece of writing . Writers may have different writing methods , but the writing stages are essentially the same. These stages break writing into manageable pieces from planning, drafting, and sharing to revising, editing, and publishing. That way, the task seems less laborious.

The primary strength of the writing process is its usefulness in producing a wide range of content. Whether you’re an academic writer, blogger , or screenwriter , it helps you write better, easier, and faster.

Read More: The Best Copywriting Courses For Beginners

Why is the writing process important.

Having a writing process will help you break your writing tasks into manageable parts, making the work less intimidating. As a result, you’re less likely to experience writer’s block. It could also aid in reducing the anxiety and stress that comes with writing. Also, breaking down your writing work into different stages could ultimately improve content quality.

It will allow you to focus on your piece. That way, you can tailor your content to address the specific needs of your target audience.

We could think of writing in terms of merely producing materials for readers to enjoy. But there’s more to the story.

With the right approach, writers usually undergo three stages — thinking, learning, and discovery — to produce excellent pieces. And such authentic writing usually makes lifelong learners and versatile writers.

Writers must always follow a writing process to be efficient and more productive.

It does not matter whether you are writing a thesis, academic report , research paper , essay, or blog content. The more organize your ideas are when you present them in text, the more you will be able to connect with your readers.

What are the 7 Steps of the Writing Process?

The EEF’s “ Improving Literacy in Key Stage 2 ” guidance report broke down the writing process into seven stages. This includes the planning , drafting, sharing, evaluating, revising, editing, and publishing stages. As writers become adept in these stages, they can quickly move back and forth, revising their text along the way. In other words, writing is not a linear process.

1. Planning or Prewriting

The planning or prewriting stage involves brainstorming, which takes into account your writing purpose and goal. It’s also the stage to connect your ideas using graphic organizers. The prewriting stage is when you ask the following questions:

- What will I write?

- What is the intended purpose of the writing?

- Who is the audience for your writing?

You need to do intent research to better understand what your target readers need. For instance, if you are writing for the web, you can take advantage of Google-Related Questions to know what the people are searching for online in relation to your topic.

Answering these questions ensures that you start your writing with the end in mind. Furthermore, you’ll be able to see your writing project through your audience’s eyes.

2. Create Your First Draft

Before your content is ready for publishing, you must have created a couple of drafts.

Thanks to the drafting process, you can write freely from the beginning to the end. What’s more, it provides a way to quickly draw from your outline or list of main plot points — depending on your writing process.

You could also use these stages to establish word count goals to get a rough idea of the project duration. This is especially important for creative writers such as novelists.

3. Share Your First Draft

After completing the first draft, it’s time to take a break and share the text with others.

While it may sound a bit scary at first, the feedback will help you evaluate elements of your writing. These include the composition, structure, and overall effectiveness.

Consider sharing your first draft in the following places:

- Your email list — if you have one

- Online writing groups and forums

- Social media groups for writers

- Social media group for a specific genre

In the end, you’ll know whether your first draft fulfills the intended purpose and appeal to your audience. The feedback also tells you if your writing is clear, enjoyable, and easy to read.

4. Evaluate Your Draft

This writing process involves doing a full evaluation of your first draft.

At this stage, you have to take the feedback that you’ve received into account. It’s also an excellent opportunity to address possible mistakes with grammar or mechanics.

For fiction writers, this writing stage allows you to ask whether the readers like your main character. Likewise, non-fiction writers have to ask if their content addresses their audience’s questions.

After evaluating your work, you can move to the revision stage of writing.

5. Revising Your Draft

Revision involves making changes to your work based on the feedback you received and thorough evaluation. This writing process is especially useful for fiction writers.

Along with correcting structural problems in your story, it also allows you to find loose ends and tie them up. You can also add or remove content to improve your write-up’s flow and usefulness.

When you’re done revising, you’ll have a new draft that takes you closer to your writing goal .

At this point, your newest revision becomes your latest draft. After that, you may opt to edit your own work using a content writing and editing tool like INK or hire a professional editor.

6. Editing your Content

The editing aspect of the writing process is about eliminating possible errors in your revised content. These include elements that can affect your text’s accuracy, clarity, and readability.

The editing process also addresses misquoted content, factual errors, awkward phrasing, and unnecessary repetition. Not only does good editing make your work easier, but it also makes the text more enjoyable.

Specialized writing tools such as INK could prove useful for editing web content. But it’s best to avoid self-editing for books. Consider hiring a professional editor for novels and non-fiction books.

7. Publishing your Content

The last stage of the writing process involves sharing your text with your audience.

There are various ways to publish your content, depending on the content type. For example, you can share your book using self-publishing platforms such as Kindle Direct Publishing (KDP) and CreateSpace .

Whatever the writing may be, the writing processes outlined above will help you create an excellent piece.

What is the Most Important Step in the Writing Process?

Educators have not reached a consensus on the most important writing process . Some would argue that the prewriting stage is the most critical for completing a piece of writing.

After all, brainstorming is required to create an idea that’ll eventually become the content. Besides, writers can use the prewriting stage to avoid or overcome writer’s block.

Meanwhile, educators at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill believe that the revision stage is the most critical. It’s when a piece of writing undergoes the most changes.

It could entail increasing the word count to supply as much information as possible. You could also rearrange some aspect of the manuscript to improve the content’s flow, pacing, and sequence.

Read More: 10 Effective Content Writing Techniques for Beginners

Found this article interesting?

Let Sumbo Bello know how much you appreciate this article by clicking the heart icon and by sharing this article on social media.

Sumbo Bello

Sumbo Bello is a creative writer who enjoys creating data-driven content for news sites. In his spare time, he plays basketball and listens to Coldplay.

Google Docs Machine Translation Grammar Suggestions now Live

4 Content Marketing Pitfalls and how to Avoid Them

Tag Manager Verification Issue on Search Console Fixed

10 Best Content Writing Courses for Beginners

Here's how to Write Better Listicles

Why the Dutch are Investing Heavily in Bangladesh Water Infrastru...

How Many Pages is 1000 Words?

How Fighter's Blocks! Uses a Video Game to Solve Writer's Block

4 Techniques to Make Your Content More Persuasive

How to Become a Successful Content Manager

How to Come up With Writing Topics for Your Website

How Facebook Instant Articles Improves Your UX

10 Social Media Marketing Tips to Help You Succeed

How and why you Should Only Create Authentic Content

Comments (2).

One has to be careful with the brokers on the internet now. Last year I was scammed in the binary trade option by a broker I met on Instagram. I invested $14000 which I lost, I couldn’t make a withdrawal and I slowly lost access to my trade account for 3 months I was frustrated and depressed. After a few months, I met Mrs Lisa who is A recovery expert that works in affiliation with the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) and other law firm. she worked me through the process of getting my money back and all the extra bonus which I got during my trading. he can be of help to anyone who has a similar situation. You can contact him via her mail: Email Lisa.Eric @ proton.me WhatsApp +84 94 767 1524

Hello guys I wan to say this to whom it may concern. Investing in crypto was my husband ideal. I trade with sim ceypto platform not knowing they where sc!m and this made me lose almost all I had. Am only happy because I found help after reporting to Mrs Lisa Eric and she helped me recover all I lost to these fake crypto platform. My advice is that everyone need to be careful of the platform you deal with. If you have falling victim of these fake platform do not hesitate to file a complaint to Lisa via he mail ( Lisa.Eric @ proton.me ) she helped me and I believe she can help you too. Stay safe guys. You can visit WhatsApp +84 94 767 1524.

Link Copied Successfully

Sign in to access your personalized homepage, follow authors and topics you love, and clap for stories that matter to you.

By using our site you agree to our privacy policy.

Literacy Lines

Home » Literacy Lines » Stages of the Writing Process

Stages of the Writing Process

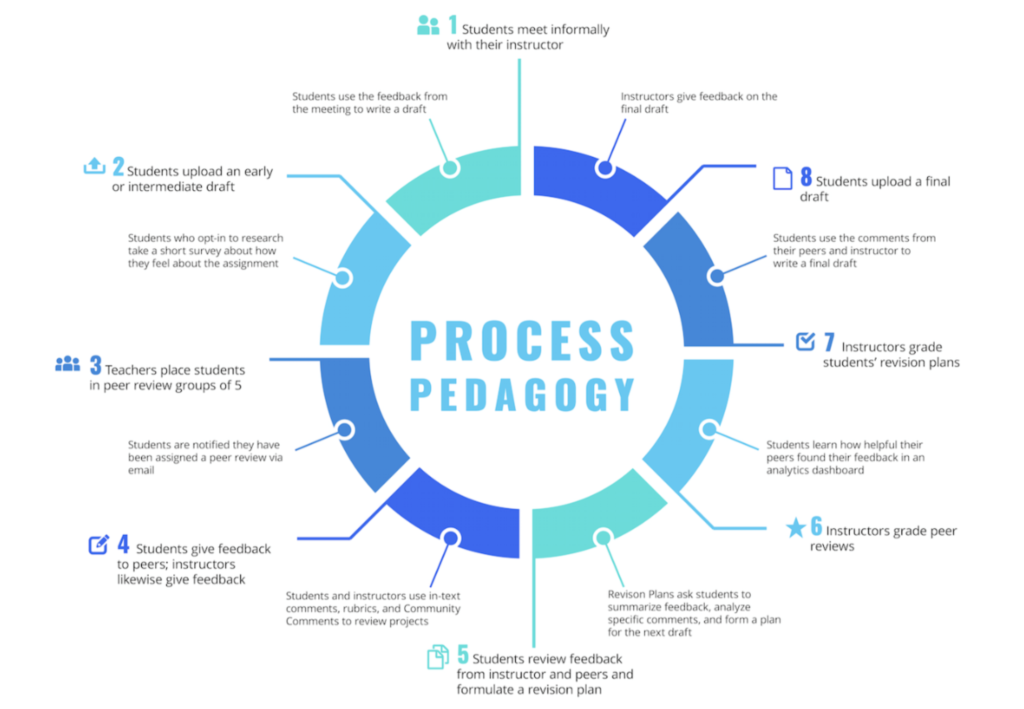

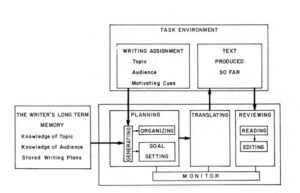

Beginning in the 1960’s, Hayes and Flower (1980) researched the steps that proficient writers take in order to better understand how to teach writing. They initially developed a model of the writing process with three stages: planning , translating , and reviewing . Over the years, the model was informed by new research and modified to include four stages (Hayes, 1996, 2004): Pre-Writing, Text Production, Revising, Editing. Today, it is accepted practice that students be taught to follow the stages of the writing process when they write.

One of the Common Core anchor writing standards focuses on the writing process : Develop and strengthen writing as needed by planning, revising, editing, rewriting, or trying a new approach. The Institute of Education Sciences research guide Teaching Elementary School Students to Be Effective Writers (Graham et al., 2012) recommends teaching students to use the writing process for a variety of purposes, noting, “It is a process that requires that the writer think carefully about the purpose for writing, plan what to say, plan how to say it, and understand what the reader needs to know.” The report goes on to explain, “Writing is not a linear process, like following a recipe to bake a cake. It is flexible; writers should learn to move easily back and forth between components of the writing process, often altering their plans and revising their text along the way. Components of the writing process include planning, drafting, sharing, evaluating, revising, and editing.” (pp 12, 14)

Teaching the Stages of the Writing Process

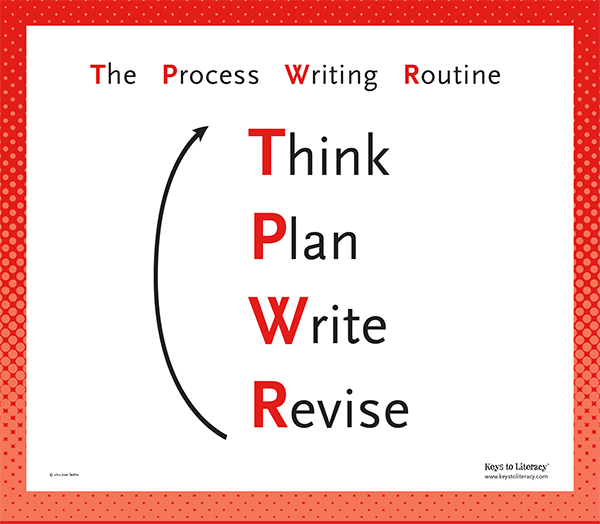

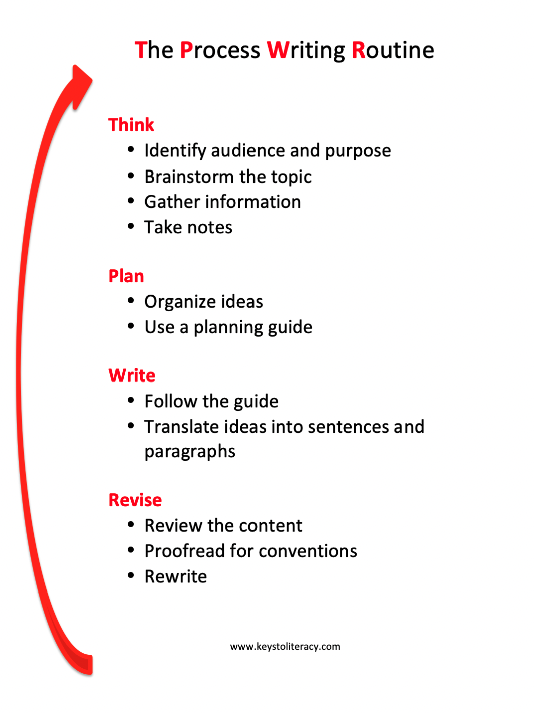

Ten years ago I proposed a model for teaching the writing process that includes four stages: THINK , PLAN , WRITE , REVISE . The title of this model, T he P rocess W riting R outine , is designed to help students recall the stages of the writing process by linking the four stages to the first letters of the words in the title. The graphic below shows the four stages with details about the tasks associated with each stage. One of the modules in the Keys to Content Writing professional development course is focused on the stages of the writing process Click here to access a copy of this handout from the free resources section of the Keys to Literacy website.

As the IES guide notes, writers repeat and revisit the stages several times as they develop a piece of writing. For example, students may realize while they are writing a first draft of an informational piece that they need to go back to the THINK stage to gather more information about the topic. While revising the draft, they may determine that they need to go back to the PLAN stage to reorganize the content. The arrow serves as a reminder that writing stages are overlapping parts of a process that may be repeated multiple times as writing unfolds.

It is helpful to provide a visual reminder of the writing process to students such as displaying The Process Writing Routine in a classroom anchor chart, as a handout for students to keep in their notebooks, or as a digital resource file. The poster shown below is available from Keys to Literacy .

Too often, students assume the focus of their attention should be on writing. They do not spend sufficient time at the THINK and PLAN stages, or they skip them altogether. The amount of time spent on each stage will vary depending on the writing task, but a common recommendation is to spend 40% of the time reading, gathering ideas and information, and taking notes (THINK and PLAN); 20% of the time draft writing (WRITE); and 40% of the time rewriting and revising, including editing for conventions (REVISE). Students need to learn that in most cases, spending more time at the THINK and PLAN stages will produce a better writing draft and save time at the REVISE stage.

Introducing the Stages to Young Students

I have simplified the stages for young students in the primary grades, as shown below and addressed in one of the modules in the Keys to Early Writing professional development course. The more basic model combines the first two stages and includes visual cues. A copy of this graphic is available at the free resources section of the Keys to Literacy website.

Students in kindergarten and grade 1 may not be developmentally ready to formally revise their work and instead may focus their editing on adding more to their drawings, labels, phrases, or sentences. View the suggestions below for introducing young students to the stages of the writing process.

- Generating Ideas and Organizing: What do I want to say? How will I present what I want to say?

- Using Drawing and Words: How can I use drawings, words, and sentences to communicate what I want to say?

- Improving: Can I add more detail to my drawing or words?

Teaching Students Strategies for Each Stage of the Writing Process

Research consistently confirms that teaching strategies to students for planning, revising, and editing their writing pieces can have a dramatic effect on the quality of their writing (Graham & Perin, 2007; Graham et al., 2012; Graham et al., 2017). Strategy instruction involves explicitly teaching generic processes such as peer collaboration or note taking, or strategies for accomplishing specific types of writing tasks such as writing a summary or a story. Some strategies incorporate a scaffold such as a graphic organizer or a writing template. The following earlier blog posts provide instructional suggestions for writing strategies:

- Teaching Text Structure to Support Writing and Comprehension

- The Might Paragraph

- Teaching Handwriting

- The Power of Transition Words

- Syntactic Awareness: Teaching Sentence Structure Part 1

- Syntactic Awareness: Teaching Sentence Structure Part 2

- Explicit Instruction of Note Taking Skills

- Patterns of Organization

RELATED RESOURCES

- Vide o: Teach Students to Use the Writing Process for a Variety of Purposes (Institute of Education Sciences)

- The Writing Process (University of Kansas Writing Center)

- Stages of the Writing Process (Purdue Online Writing Lab)

- Graham, S., Bollinger, A., Booth Olson, C., D’Aoust, C., MacArthur, C., McCutchen, D., & Olinghouse, N. (2012). Teaching elementary school students to be effective writers: A practice guide (NCEE 2012- 4058). Washington, DC: National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance, Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education.

- Graham, S., Bruch, J., Fitzgerald, J., Friedrich, L., Furgeson, J., Greene, K., Kim, J., Lyskawa, J., Olson, C.B., & Smither Wulsin, C. (2016). Teaching secondary students to write effectively (NCEE 2017-4002). Washington, DC: National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance (NCEE), Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education.

- Graham, S., & Perin, D. (2007). Writing next: Effective strategies to improve the writing of adolescents in middle and high schools – A report to Carnegie Corporation of New York. Washington, DC: Alliance for Excellent Education.

- Sedita, J. (2020). Keys to Early Writin g. Rowley, MA: Keys to Literacy.

- Sedita, J. (2020). Keys to Content Writing. Rowley, MA: Keys to Literacy.

- Joan Sedita

Leave a Reply

Cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Subscribe by Email

- Adolescent Literacy

- Brain and Literacy

- Close Reading

- College and Career Ready

- Common Core

- Complex Text

- Comprehension Instruction

- Content Literacy

- Decoding and Fluency

- Differentiated Fluency

- Differentiated Instruction

- Digital Literacies

- Disciplinary Literacy

- Elementary Literacy

- English Language Learners

- Grammar and Syntax

- High School Literacy

- Interventions

- Learning Disabilities – Dyslexia

- Middle School Literacy

- MTSS (Multi-Tiered Systems of Support)

- PK – Grade 3 Literacy

- Professional Development

- RTI (Response to Intervention)

- Special Education

- Teacher Education

- Teacher Evaluation

- Text Structures

- Uncategorized

- Vocabulary Instruction

- Writing Instruction

Posts by Author

- Becky DeSmith

- Donna Mastrovito

- Brad Neuenhaus

- Shauna Cotte

- Sue Nichols

- Amy Samelian

- Colleen Yasenchock

- melissa powers

- Sande Dawes

- Maureen Murgo

- Stephanie Stollar

ACCESSING KEYS TO LITERACY PD DURING SCHOOL CLOSURES

We are closely monitoring the covid-19 situation and the impact on our employees and the schools where we provide professional development., during this time period when onsite, face-to-face training and coaching is not possible, we offer multiple options for accessing our literacy pd content and instructional practices., if you are a current or new partner, explore our website or contact us to learn more about:.

- Live virtual training, coaching

- Facilitated and asynchronous online courses

- Free webinars and resources

[email protected] 978-948-8511

In order to continue enjoying our site, we ask that you confirm your identity as a human. Thank you very much for your cooperation.

The 6 stages of the writing process: A helpful guide for authors

Posted on June 11, 2020 at 1:23 PM by Guest Author

As an author, you should be familiar with the six basic stages of the writing process. Discover more about why this process is important and what each stage entails.

Table of Contents

Why You Should Know the Stages of the Writing Process

Stage 1 – Prewriting

Stage 2 – Planning

Stage 3 – Drafting

Stage 4 – Revising

Stage 5 – Editing

Stage 6 – Publishing

Why you should know the stages of the writing process .

Like most authors, you likely have your own unique approach to writing books.

When you sit down to tell a story or provide in-depth coverage of a topic, you follow certain steps to bring your idea to life.

Although there’s nothing wrong with tackling each new project according to your personal preferences, it’s still worth revisiting the six basic stages of the writing process from time to time.

First , it’s simply a good practice to develop, especially if writing professionally is something you’ve only started doing recently.

Running through the various stages of the writing process ensures you’ve covered your bases. It keeps you organized and helps you work more efficiently. As a result, you can look forward to a better finished product every time.

Second , consciously going through each stage of the writing process can be a great way of getting unstuck when you’re struggling to take an idea to the finish line.

Although writing is a creative endeavor, sometimes it helps to have a little more structure. Just knowing how to begin can break down those mental barriers that keep you from moving forward.

Third , though you may have your own routine when it comes to writing, chances are you’re following the basic steps anyway — even if you don’t realize it.

In that case, it wouldn’t hurt to familiarize yourself with the terminology. That way, you can keep a mental (or physical) checklist, adjusting it to fit your creative workflow .

With all of that in mind, we wanted to take this opportunity to give you a refresher on (or possibly an introduction to) the six stages of the writing process.

Ready? Let’s dive in…

Stage 1 – Prewriting

As the name suggests, the prewriting stage consists of the work you do before you actually start writing your book.

This stage tends to vary the most from one author to the next, as everyone generates ideas differently. Ultimately, it comes down to how you brainstorm and flesh out concepts that pop into your head.

Some of the tasks you may perform during this stage include…

Jotting down notes about a real-life scene

Drawing inspiration from a childhood event

Gathering information about a topic that interests you

Thinking about how a character should look, sound, and act

Pulling out part of a writing prompt

When one of your ideas begins to take shape, that’s when you move on to the next stage.

Stage 2 – Planning

It’s fair to say that planning is one of the most important stages of the writing process.

Without at least a general sketch of your characters or path for your plot, you’re more likely to hit a roadblock halfway through writing.

By planning ahead of time, however, you can typically avoid such an issue and have a much easier time crafting your book.

This stage may look very different depending on whether you’re a pantser (someone who prefers letting their story develop naturally) or a plotter (someone who likes to plan out every aspect of their book).

And it’s worth noting there are pros and cons to each.

No matter how you operate, you should put time and effort into your initial outline, allowing yourself some flexibility in terms of story structure, character development, and more.

Once you’ve finished planning, it’s time to start writing!

Stage 3 – Drafting

The drafting stage is all about getting your words down on paper (or screen). It’s not about trying to create the perfect book right off the bat, as you’ll work on revising and editing the initial draft later on.

If you’re a first-time writer, you may struggle with this. However, you just need to keep a couple of things in mind…

The first draft is for your eyes only.

You can always go back and make changes.

There really aren’t any set rules about how to draft your book. It’s just a matter of completing the initial draft from start to finish.

If you find yourself faltering midway through the first chapter, try skipping to the end — whatever pushes you to move forward.

After you’ve completed your first draft, it’s best to wait at least a few days before proceeding to the next stage.

Stage 4 – Revising

Many authors consider revising to be one of the most challenging stages of the writing process.

Because it requires you to scrutinize your first draft , which can be downright painful. Essentially, you need to be your own critic and try to remain as objective as possible.

During this stage, the goal is to start cleaning up and shaping your story.

Some of the ways to do this include…

Adding details your readers need to understand what’s going on

Rearranging passages to improve the flow or pacing of the story

Removing sections that don’t fit or add little value

Eliminating awkward sentences or language

Ensuring your character’s actions make sense

Balancing exposition and dialogue

Making each scene as compelling as possible

When you’ve made all the necessary revisions and are generally happy with the draft you have, set it aside for a couple of weeks before moving on to editing.

Stage 5 – Editing

In the editing stage, your primary objective is to fine-tune your book. You want to ensure your writing is as smooth as possible, your story makes sense, and your text is free from errors.

Even if you edit as you go, you can still end up making mistakes and leaving things out. That’s why it’s crucial to read your manuscript in its entirety so you can fix those trouble areas.

Although there are plenty of resources out there to help you develop your writing skills so you can self-edit more effectively, it may be worth bringing on a professional to edit your book as well.

Doing so not only puts another pair of eyes on your manuscript but also allows you to take advantage of another’s expertise.

It may take a few drafts before you deem your book “ready,” but once you reach that point, it’s time to advance to the last stage.

Once you’ve put the finishing touches on your book, you need to figure out how to make it available to readers.

There are a few ways to get your book published , including…

Taking the traditional publishing route

Hiring a company to publish your book

Submitting your book to a publisher independently

Opting to self-publish your book

Each option has its benefits and drawbacks. The one you choose depends on your budget and needs.

If you decide to self-publish, bring in others to ensure your book is truly ready and avoid publishing too early.

There you have it — the six stages of the writing process. If you followed along with us, you should now have a deeper understanding of what’s involved in taking a book from idea to finished product.

Remember that the approach you take to creating a book may not look exactly like this, and that’s okay! However, familiarizing yourself with these basic stages and revisiting them every so often can make things go a lot smoother.

(If you’ve completed the last stage of the writing process, it’s time to get your published work out to readers! Click HERE to learn more about promoting your free ebook in our newsletter to reach thousands of potential fans.)

Categories: Behind the scenes

Tagged As: Writing advice

* Indicates a required field

Writing process: From discovery to done (complete guide)

The writing process has many stages, from discovery and investigation to publication. Read authors’ insights on finding ideas, revision and more, and tips and methods to find the process that works for you.

- Post author By Jordan

- 5 Comments on Writing process: From discovery to done (complete guide)

The writing process is a complex, not always linear creative process. From ‘plotters’ vs ‘pantsers’ (to ‘bashers’ vs ‘swoopers’), this guide unpacks stages of the writing process, what authors have said about the practices and habits of writing, and more. Use the links above to jump to the section that interests you now.

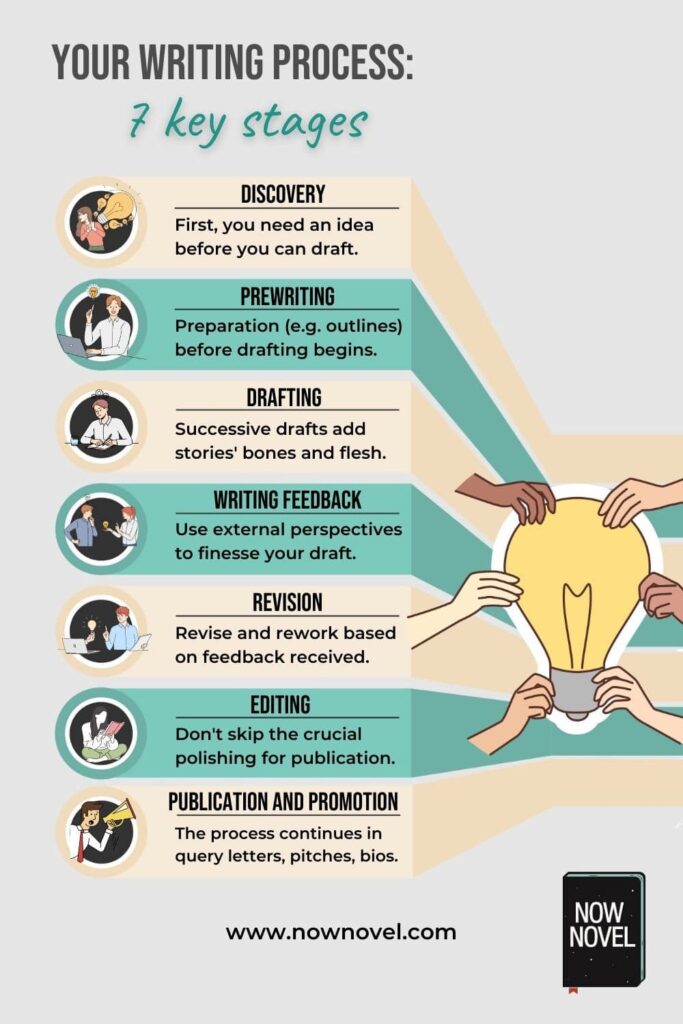

Writing process stages: 7 areas of practice

Some writing schools and authors divide writing into four stages, some five. Yet these seven see a story from first idea to publication:

- Discovery. Before you can draft, you need an idea, a premise. This is the investigative stage of finding the seed for a story with the most potential.

- Prewriting . The preparation to write before drafting begins. Depending on whether you’re a ‘plotter’ or ‘pantser’ (more on this below), this may include outlining, brainstorming, freewriting, or other common prewriting techniques.

- Drafting. You write narration, exposition, scenes, chapters (depending on your story’s format). Drafting may be fast or slow, depending on your preferred methods. Try different approaches and techniques to shake up your usual writing habits.

- Writing feedback and story development. Once you are comfortable to share your work-in-progress (WIP), you may share early drafts with a trusted friend, writing coach or critique circle for perspective and insight.

- Revision . The process of reviewing what you’ve written, deciding what to keep (and which ‘darlings’ to ‘kill’).

- Editing. While revision entails making decisions about the content of your story, editing involves making decisions about the presentation of that content – how best to make the story more impactful and polished.

- Publication (and promotion). Isn’t the writing process over at this stage? Not at all – your query letters, story pitches, blurbs, review requests and other matter will be some of the most important material of the entire writing process. This is the writing that puts the story you’ve labored over in the right hands.

Keep reading for tips, methods and ideas about each of these stages, supplemented by reading from the Now Novel blog.

Recommended reading

- The writing process: 7 steps to structure and success

To the top ↑

Sometimes we fail for a week, a month, a year, a decade. And then we come back, circle the fire. Our lives are not linear. We get lost, then we get found. Patience is important, and a large tolerance for our mistakes. We don’t become anything overnight. Natalie Goldberg, The True Secret of Writing (2013), p. 58.

Discovery: Finding and investigating writing ideas

The writing process may start from an idea that arrives like a soothsayer. A flash of inspiration, insight, wisdom – a dream, unexpected connection, some kind of beguiling chance encounter or happenstance that makes you say, ‘I’ve got an idea’.

Yet the idea-finding process may equally be deliberate, even robotic. Consistently trying your hand at writing prompts until an idea niggles away at your waking mind, for example, persistently saying, ‘pick me’.

Finding and developing writing ideas is a skill you develop like any part of the writing process. That way you can make an idea come, not just for a first book, but a second, third (if with a little coaxing).

Essayist and cultural theorist Walter Benjamin said of the writing process:

Work on a good piece of writing proceeds on three levels: a musical one, where it is composed; an architectural one, where it is constructed; and finally, a textile one, where it is woven. Walter Benjamin, quote via Goodreads .

Before you make a picture with those threads, you need the wool you spin into finer thread: The fluffy stuff of an idea.

Writing process methods: Ways to find ideas

There are many ways to find ideas and find joy in the discovery stage of writing process.

Discovery and investigation may include a little or a lot of research, depending on what you need to know. The seed of an idea may come from multiple sources at once, as Toni Morrison says of her Pulitzer-winning novel Beloved :

Beloved originated as a general question, and was launched by a newspaper clipping. The general question (remember, this was the early eighties) centered on how – other than equal rights, access, pay, etc. – does the women’s movement define the freedom being sought? Toni Morrison, ‘On Beloved ‘ in Mouth Full of Blood: Essays, Speeches, Meditations, p. 281.

Here are fifteen ways to find ideas:

15 ways to find writing ideas and begin the writing process

- Try writing prompts such as the step-by-step prompts to find a central story idea in the Now Novel dashboard.

- Ask ‘What if…?’ For example, ‘What if a mysterious satellite held captivating mysteries about an alien race?’

- Draw from life. What experience could you use/alter for non-fiction or fiction?

- Use visual prompts. Use a photo or artwork as your starting point. Free-write a paragraph describing what you see, then continue and keep or turf the opening material.

- Play/combine. William S. Burroughs’ famous ‘cut up’ technique reassembles random cuttings from print into new ideas, for example.

- Trawl headlines. Google intriguing subjects in the ‘news’ tab. E.g. ‘travel disasters’ brought up ‘How ‘dark tourism’ can pass on the lessons of past tragedies’. Mine your headline for ideas.

- Explore myths and legends. Reads stories from world mythologies. You could update an ancient tale with modern touches.

- Argue with other stories. Maybe a story’s annoyed you, or you want to explore a secondary character’s viewpoint (from a work now in the public domain). Write back.

- Test out ideas in short fiction. Famous novels (such as Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man by James Joyce) began as short story test runs.

- Draw inspiration from music. Listen to a song. What ideas, characters, premises do the lyrics evoke?

- Try creative constraints. The collective OuLiPo used devices such as writing stories omitting a chosen vowel entirely to find the unexpected.

- Browse famous quotes. Take something like ‘Happy families are all alike…’ from Anna Karenina . Where else could it lead?

- Join writing groups. Prompts set by members for each other may inspire new ideas.

- Research historical figures or eras. You may unearth a riveting idea from the past.

- Tap into your subconscious and keep a dream journal or meditate, silence and going inward often brings clarity.

FAQs about the discovery stage of writing

Share your idea with trusted people for external perspective. Test it out in a writing group or class. Ask questions about ‘who’, ‘what’, ‘why’ ‘where’ and ‘when’ to finesse a hazy or partial idea into something deeper, fuller.

The varied ways myths and legends are recycled (Thor in Norse mythology becoming Marvel’s popular character) reminds us there are no new ideas. Originality lies in the specifics of voice and execution. Be specific, be yourself and find your voice through practice and intentional execution.

This is where it helps to remember the writing process is not linear. The discovery stage is also a good time for research, finding out what is being done (and overdone) in your genre. What agents are looking for (or tired of seeing). Resources listing recent publishing deals give insights into what’s sold recently and book market appetites. To start though, focus on telling a good story. Great stories find their audience.

🗣️ How did you find your last story idea? Let us know in the comments, and keep reading for tips and methods for prewriting, drafting, and more.

- 38 plot ideas (plus 7 ways to find more)

- How to find book ideas: 15 easy methods

- Book ideas: 12 fun ways to find them

- Finding story topics when stuck: 5 simple methods

GET YOUR FREE GUIDE TO SCENE STRUCTURE

Read a guide to writing scenes with purpose that move your story forward.

Ideas are like fireflies; go hunting for them and they elude you. Sit and enjoy the night, and they appear from out of nowhere. You have to let the ideas come to you. Expand your world, read outside your comfort zone, take walks. The fireflies will come. Just give them the chance. Sabrina Jeffries in 101 Habits of Highly Successful Novelists: Insider Secrets from Top Writers by Andrew McAleer (2008), p. 69.

Prewriting: Useful preparatory writing processes

Prewriting is the processes before you start drafting a story which help you prepare.

There are many kinds of prewriting. Because the writing process is not linear, you might come back to one or more of these methods at some stage of drafting:

Common prewriting steps and methods

- Picking a premise. If you have multiple ideas, go with the idea that pulls you most and (if you want a marketable book) the one you know has the better market potential.

- Choosing a genre or subgenre. This goes hand in hand with picking a premise, since if you set your book in outer space and explore future technology, chances are you’ll be shelved with sci-fi.

- Brainstorming. A process of generating ideas, whether you use mind maps, answer prompts and questionnaires, or churn out every idea you can think of in scenario- or topic-driven lists.

- Creating a story outline. This may be a meticulous, detailed outline, or a cursory collection of notes. The more complete your outline, the more handrails you’ll have. This prevents wandering off into irrelevancies, plot holes and impossible paradoxes, and so on.

- Creating initial summary material. Summary material includes things like character profiles or IDs, scene summaries , or a one-page synopsis of what your story is about (also a useful exercise in the Publication and promotion stage of process).

- Freewriting. Before more structured drafting, you might explore a topic or scenario with freewriting. Set a timer for 15 to 20 minutes and just write whatever comes into your head about a topic you think will be important to your book. It might spawn scene, chapter, or character ideas.

- Research. This may overlap with the discovery/investigation stage, as your idea may also need a little research to solidify what you want to write about. It might include fiction set in a similar era or place, making a bibliography of potentially helpful non-fiction, speaking to subject exploring films and documentaries, or visiting physical or digital archives. For some tips on how to research place when you can’t visit those places, read our tips.

- Interviewing. This is especially pertinent for types of writing such as historical fiction, non-fiction, memoir. Interviews with subject experts, people who lived through specific events or an era, could provide helpful nuance, context, and ideas for relevant story details.

You don’t necessarily need to do every kind of prewriting. Some authors favor ‘just-in-time’ research (an idea Bujold spoke about in relation to fantasy worldbuilding ).

Authors on prewriting and whether or not to plan stories

The prewriting perspectives below show there are many way to skin (or rather save) a cat. Try different methods and find what works for you .

Loose story outlining

Author Scott King gives this reminder that prewriting (planning, creating structure, organizing) should serve the needs of your story, and stay adaptable to its unique needs:

An outline is a map of your story. It’s not set in stone. Even when you work from an outline, you will discover new twists and turns as you progress. The outline is there to remind you of where you are going so you can’t ever get too far from where you need to be. Since I was working under pressure, I didn’t want to get crazy with how I structured Ameriguns . I defaulted to a three act structure, the kind you’d use in a screenplay, but altered it to fit the needs of the story. Scott King, ‘Outline’ in The 5 Day Novel , 2016, p. 58.

Pullman on how establishing rules is part of play

More broadly, Philip Pullman, in ‘The Practice of Writing’, talks about how having some rules at the start of creative process gives paradoxical freedom to play. He compares guidelines such as rules (or outlines) to choosing where touchdown lies for a football game:

And as we know about all games, it’s much more satisfying to play with rules than without them. If we’re going to enjoy a game of football in the playground, we need to know where the touchline is, and agree on what we’re going to regard as the goalposts. Then we can get on with playing, because the complete freedom of our play is held together and protected by this armature of rules. The first and last and only discovery that the victims of anarchy can make is: no rules, no freedom. Philip Pullman, ‘The Practice of Writing’ in Daemon Voices , pp. 18-19

‘Plotting’ vs ‘Pantsing’: Find your balance between prewriting and drafting

So much has been written and said about whether you should plan stories in detail in advance (‘plotting’), or go where imagination takes you (‘pantsing’, after the expression ‘to fly by the seat of your pants’ or work with instinct and gut more than organized knowledge).

Your writing process may change to suit your project

Author K.M. Weiland raises the useful reminder that your writing process doesn’t need to ape a famous writer’s approach, or be the same across every story you tell:

Each author must discover for himself what methods work best for him. Just because Margaret Atwood does X and Stephen King does Y is no reason to blindly follow suit. Read widely, learn all you can about what works for other authors, and experiment to discover which methods will offer you the best results. K.M. Weiland, ‘Chapter One: Should You Outline?’ in Outlining your Novel: Map your way to success , p. 11.

Planning stories helps character development

Edith Wharton, the first woman to win the Pulitzer Prize for writing, said of the space and planning deeper characterization requires:

Type, general character, may be set forth in a few strokes, but the progression, the unfolding of personality […] if the actors in the tale are to retain their individuality for [the reader] through a succession of changing circumstances—this slow but continuous growth requires space, and therefore belongs by definition to a larger, a symphonic plan. Edith Wharton, The Writing of Fiction: The classic guide to the art of the short story and the novel (1925), p. 33.

Not planning, creative freedom and excitement

Author Lee Child, on the other hand, extolls the benefits of not planning (and not being as pedantic about the marks you hit as an editor or publisher might be):

I write without a plan or an outline. The way I picture my process is this: The novel is a movie stuntman, about to get pushed off a sixty-story building. The prop guys have a square fire-department airbag ready on the sidewalk below. One corner is marked Mystery, one Thriller, one Crime Fiction, and one Suspense. The stuntman is going to land on the bag. (I hope.) But probably not dead-on. Probably somewhat off center. But biased toward which corner? I don’t know yet. And I really don’t mind. I’m excited to find out. Lee Child, ‘Introduction’ in How to Write a Mystery: A handbook from Mystery Writers of America

🗣️ What is your preferred prewriting method? Or do you pants it all the way, or pants a little then switch to planning? Tell us in the comments.

- What is prewriting? Preparing to write with purpose

- Story plotting and structure: Complete guide

- Story planning and outlining: Complete guide

- Story planner success: How to organize your novel

GET HELP PLANNING YOUR BOOK

Join Now Novel for a helpful crit community and live webinars and plotting tools when you upgrade.

Writing process challenges you may encounter

Before we discuss drafting and the writing process, let’s explore common process challenges (and tips to overcome them):

Common hurdles in creative process

There are challenges in creative process that beginning authors and veterans alike face. You’re not alone if you’ve ever gone rounds in the ring with:

- Fear of failure (or success). What happens if a publisher or agent says no? What if reviews or crits are harsh? Or how will you handle sudden public recognition and scrutiny in the event of success?

- Procrastination (avoidance behaviors). When writing a story feels hard, it’s easy to put it off (or use not having time or something else as an excuse not to write).

- Distractibility. Whether you have a condition such as ADHD that adds further focus challenges or are a social media addict, we live in a highly distracting, ‘always on’ world.

- ‘Time Burglars’ . There are many thieves of time that take away from the writing process if you don’t make regular writing a top priority.

- A harsh inner critic. Many aspiring creative people have harsh inner critics who destroy their work before anyone else can.

- Laziness. This is a common reason not to write, too.

- Unpreparedness. Many writers find projects spool out and become much harder and more complex than originally anticipated. That can be discouraging.

Overcoming writing process challenges

How can you work with and overcome some of the above procedural challenges in writing?

- Keep SMART goals: Specific, measurable, attainable, realistic and time-based goals are much easier to track and attain than hazy aims

- Work on tolerance for your mistakes: Everyone makes mistakes starting out, and seasoned pros do, too

- Chunk up complex tasks: Struggling to write a chapter a week to schedule? Try write 300 words per day and set a bigger ‘stretch goal’ (an extra target if you make your first easily)

- Turn off the net if you need to: Put your phone in airplane mode and pause all notifications

- Remember the difference between procrastination and waiting: It’s fine to wait for maturity, fuller knowledge of your subject, to be in the right frame of mind. It’s not putting off but letting process take its necessary time for this story

- Get up and move often: The writing process is (for the most part) a sedentary one. It’s easy to forget to move. Stone-like posture may lead to petrified process, even if your mind’s going a hundred miles a minute

The accountability of working with a writing coach or joining a crit circle that meets regularly helps (in Now Novel’s experience), too.

Natalie Goldberg writes, on procrastination vs waiting:

Waiting is something full-bodied. Perhaps waiting isn’t even a good word for it. Pregnant is better. You’ve worked on something for a while. You are excited by it, even happy, but you are wise and step back. You take a walk, but this walk isn’t to avoid the writing on your desk. It is a walk full of your writing. It is also full of the trees you pass, the river, the sky. You are letting writing work on you. Natalie Goldberg, ‘Procrastination and Waiting’, in Wild Mind: Living the writer’s life , p. 210.

How to nurture your writing process and avoid common pitfalls

We asked Now Novel’s writing coaches their best advice on the writing process, and about patterns they see in beginning writers (and ways to overcome destructive habits).

Romance author and writing coach Romy Sommer on remembering why you’re telling your story:

Writing is hard work. Probably harder than you thought it would be when inspiration first struck and you decided to write a novel. So find the joy in what you are writing. Remind yourself daily of WHY you are writing this story. Remember that spark that first inspired you to sit down and write, because that is what will keep you going when the going gets tough.

SFF and YA author, editor and writing coach Nerine Dorman on allowing yourself to make ‘happy accidents’:

Many writers I’ve worked with lack confidence in their ability, and tend to focus on those first chapters to the point where they lose the momentum to push forward with the rest of the plot. I give them Bob Ross’s advice of making plenty of ‘happy little accidents’ as we can’t actually work on writing if there’s nothing there to revise. Your first draft can be as messy as you need it to be. The most important thing is to get into the habit of writing as regularly as your schedule allows, and to see your writing as a very personal way to express yourself. Granted, there are the basic building blocks of writing and style, which I aim to teach, but I like to think that we also look at what it means to be a writer – a constantly evolving, growing creative person.

Recommended Reading