An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Food Marketing as a Special Ingredient in Consumer Choices: The Main Insights from Existing Literature

The choices and preferences of food consumers are influenced by several factors, from those related to the socioeconomic, cultural, and health dimensions to marketing strategies. In fact, marketing is a determinant ingredient in the choices related to food consumption. Nonetheless, for an effective implementation of any marketing approach, the brands play a crucial role. Creating new brands in the food sector is not always easy, considering the relevant amount of these goods produced within the agricultural sector and in small food industries. The small dimension of the production units in these sectors hinders both brand creation and respective branding. In this context, it would seem important to analyse the relationships between food marketing and consumer choice, highlighting the role of brands in these frameworks. For this purpose, a literature review was carried out considering 147 documents from Scopus database for the topics of search “food marketing” and “choices” (search performed on 16 October 2020). As main insights, it is worth highlighting that the main issues addressed by the literature, concerning food marketing and consumer choices, are the following: economic theory; label and packaging; marketing strategies; agriculture and food industry; market segments; social dimensions; brand and branding. In turn, food marketing heavily conditions consumer choices; however, these related instruments are better manipulated by larger companies. In addition, this review highlights that bigger companies have dominant positions in these markets which are not always beneficial to the consumers’ objectives.

1. Introduction

The food choices by consumers are influenced by several factors, where the prices traditionally have great importance, as highlighted by the economic theory. However, there are new tendencies, and some segments currently privilege healthy [ 1 ] and sustainable characteristics [ 2 ]. Food consumption has several dimensions, including that of a social and cultural magnitude, and this sometimes compromises policies to change unadjusted behaviours [ 3 ] and influence food perceptions [ 4 ]. The sociodemographic and behavioural factors also have their implications [ 5 ] on consumer behaviour. On the other hand, labelling and packaging have a significant impact on consumer choices and preferences [ 6 ].

In these contexts, marketing strategies are useful and powerful approaches in order to create and maintain a market in any economic sector and, specifically, in the food industry [ 7 ]. However, in the food market, it is important to distinguish two production sectors, agriculture and industry. These two distinct sectors with different dynamics have implications on the respective markets. This is important to highlight, because this makes the food sector different from other economic sectors.

Agriculture has several particularities that constrain the design of effective marketing plans. In fact, the structural context of farms, often, in small dimensions, in great numbers and the producing commodities are limited in the ability to create a custom positioning, a crucial ingredient for any marketing approach. The main problem of this atomised structure is associated with the reduced individual level of production, focused on parts of the year that prove difficult to maintain a regular presence in the market and the respective branding. These weaknesses of the sector limit the market choices of farmers [ 8 ]. Of course, the brand and the agricultural sector are only a part of the food marketing framework.

In turn, the food industry is often conditioned to be more competitive and to generate value added through the creation of brands. In fact, this is a sector with the dynamics and the competitiveness predicted by the economic theory for the industry, i.e., as having activities with increasing returns to scale. The performance in terms of productivity and efficiency allows for another presence in the markets and possibilities to further develop marketing plans and strategies for a more sustainable development [ 9 ].

Considering that marketing approaches influence consumer food choices, the literature survey highlights the relevance of a systematic review concerning two dimensions: food marketing and consumer choices, taking into account the specificities of the two sectors related to food production.

From this perspective, the research carried out intends to highlight the main insights from the scientific literature into the relationships between food marketing and the choices of consumption performed by consumers. To achieve this objective, 147 documents (only articles and reviews) from the Scopus database [ 10 ] were obtained, considering as topics for searches carried out on 16 October 2020 “food marketing” and “choices”. These documents were analysed through a literature survey. To better perform the literature analysis, a previous bibliographic analysis and literature survey were considered, and this approach allowed for organisation of the literature review with the following structure: economic theory; label and packaging; marketing strategies; agriculture and food industry; market segments; social dimensions; brand and branding. This approach was complemented using the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) methodology [ 11 ]. For the PRISMA approach, 137 documents (only articles and reviews) were also considered from the Web of Science Core Collection [ 12 ] for the same topics. When the documents from Scopus and Web of Science were considered together, through the Zotero software [ 13 ], a great majority were duplicated (around 100). From this perspective, considering the relevant number of documents duplicated across the two scientific databases and the Scopus platform having more documents, the decision was made to opt only for the documents from this database. The topics of search “food marketing” and “choices” were selected to find documents in the scientific databases related to the interrelationships between food marketing and consumer choices. The search topics “food”, “marketing”, and “choices” could be considered, for instance, but this search option would greatly increase the number of documents found, taking the level to an infeasible amount for a literature review; furthermore, the studies obtained were outside the intended scope (“food marketing”).

2. Bibliographic Sample Characterisation

The information presented in this section is relative to a sample obtained from the Scopus database for a search carried out with the following topics/keywords: “food marketing” and “choices”. In addition, it is important to highlight that the identification of the sample and its analysis considered other scientific contributions concerning systematic reviews [ 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 ].

The number of documents related to the topics considered has increased from 1970 until today, with relevant breaks in 2013 and 2016, with a total of 16 documents in 2020 ( Figure 1 ). This context shows that there are opportunities to increase the number of documents published with regard to these fields, considering the annual average number of studies published and the relevance of the topics.

Distribution of the documents across years.

A large part of the documents focused on subject areas such as the following ( Figure 2 ): medicine; nursing; agricultural and biological sciences; business, management and accounting; psychology; social sciences; economic, econometrics, and finance; and environmental science. This framework reveals the multidisciplinary dimension of the issues related with the topics addressed here.

Distribution of the documents across subject areas.

The majority of the studies were carried out by authors affiliated to institutions from the United States, Australia, the United Kingdom, Canada, Italy, New Zealand, Belgium, China, and Germany ( Figure 3 ). The several dimensions associated with these topics are relevant to several countries around the world. In this way and considering the values presented in Figure 3 , there are opportunities to be further explored regarding these topics by affiliated authors in institutions from important countries, such as, China, India, Brazil, and the European Union member-states.

Distribution of the documents across countries.

Source titles having two or more documents are those presented in Figure 4 . The following journals were noted: Appetite (13); Public Health Nutrition (8); Food Quality and Preference (5); Nutrients (5); British Food Journal (4); Childhood Obesity (3); Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics (3); Obesity Reviews (3).

Source titles with two or more documents.

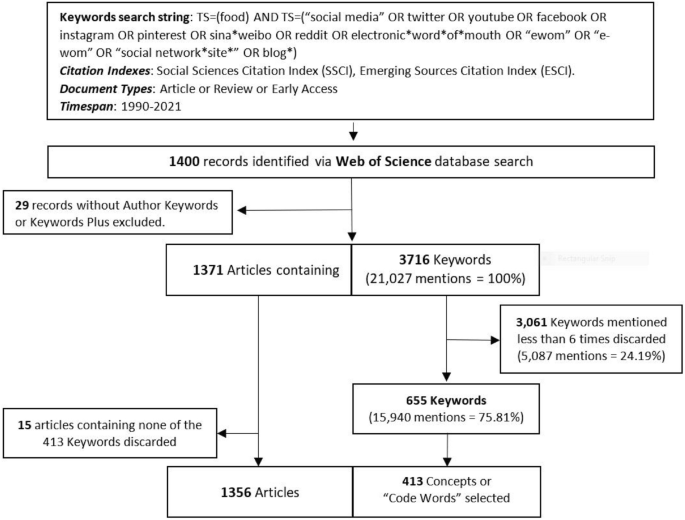

Figure 5 was obtained using VOSviewer software [ 18 , 19 ] with the 147 documents obtained from the Scopus database. This figure was obtained using bibliographic data for co-occurrence links and all keyword items. In this figure, the circle/label size represents the number of keyword occurrences, and relatedness (proximity of circles/labels) is determined on the basis of the number of documents in which the keywords occur together [ 19 ]. Figure 5 highlights the relevance of keywords, for example, obesity, child, advertising, review, interview, adolescents, market, policy, labelling, perception, willingness to pay, health, choice experiment, index method, case study, apps, and television. These keywords reveal some relevant dimensions related to food and marketing and consumer choices (obesity, health, children and youths, labelling, perceptions, taste, willingness to pay, policies, and media) and some methodological approaches (review, interview, choice experiment, index method, and case study). On the other hand, there is a great amount of relatedness (number of documents in which the keywords occur together) between food marketing and human obesity, especially in men and children.

Co-occurrences of all keywords (one as a minimum number of occurrences of a keyword).

3. Literature Survey

Considering the bibliographic analysis and a preliminary literature survey, this section is divided into the following subsections: economic theory; labelling and packaging; marketing strategies; agriculture and food industry; market segments; social dimensions; brand and branding.

3.1. Economic Theory

As predicted by the theory of demand, the consumption of goods and services by consumers to satisfy their daily needs is dependent on market prices. In addition, the theory of utility explains that, when consumers intend to satisfy their needs, they also expect to maximise utility, depending on their income. This is true in every market, including in the food markets from low-income countries [ 20 ]. Consumer demand is dependent on several factors, but the prices (own product, substitute product, and complementary product prices) are amongst the most important variables. Of course, other variables, such as product quality and the economic conjuncture of each country, have their influences on consumption. In these frameworks, consumers combine quantities of goods and services so as to obtain the maximum satisfaction from their consumption. The level of satisfaction achieved is dependent on the available revenue to consume. The economic theory assumes that the economic agents are rational, and this means that consumers want to consume more when prices are lower with the exception of luxury products or goods and services of basic needs [ 21 ]. The marketing plans, in general, bear these contexts in mind, because the consideration of these fields is determinant for a successful strategy in the food sector.

On the other hand, some dimensions are multidisciplinary and networked, such as those, for example, related to welfare [ 22 ]. Welfare is, in fact, the focus of research for several disciplines such as biology, economy, psychology, and sociology. This transversal perspective could prove interesting as a means for cross-approaches, including insights from economic theory, to promote more adjusted patterns of food consumption, mainly those more compatible with health requirements [ 23 ]. The impact on health from food consumption is a concern for several stakeholders; however, it is not an easy challenge to mitigate these implications, due to the market power of certain stronger brands.

Economic options and the respective economic dynamics, with consequences on prices and on consumer incomes, have direct and indirect impacts on food choices and, consequently, on the health of the respective population [ 24 ]. In turn, the economic theory may provide interesting insights for more effective health policies and programmes that incentivise, in a greater way, food choices which are more compatible with a balanced human life environment [ 25 ]. The economic theory may also be a relevant ally towards supporting better knowledge about company frameworks for a more effective market and marketing approaches [ 26 ].

The price elasticities, for example, may provide relevant support in these strategies and enable us to predict future patterns of food consumption [ 27 ]. The prices do indeed have a determinant impact on food markets [ 28 ], despite their particular price and income elasticities. In general, the food markets, specifically, those more linked with the production sector (agriculture), have lower, inelastic price elasticities. This means that the consumers are not sensitive in their consumption to price changes, mainly due to the fact that food products are often essential goods and services of basic needs and where the prices are lower. The same happens for income elasticities, meaning that, when consumers have more revenue, they have a tendency to increase their consumption of products other than food goods. In other words, when consumer income increases, they are willing to increase industrial and service consumption rather than consume more food [ 21 ]. This is a great task for the food industry, where the brand and respective branding are called upon here to play their contribution, whilst sometimes having implications on consumer health.

3.2. Label and Packaging

Food labelling and packaging are used to inform consumers about the product’s characteristics, in accordance with legislation, and for marketing purposes [ 29 ], but they may also provide support for healthier choices [ 30 ]. The legislation regulates the information which may be considered for labelling, and this can sometimes be too bureaucratic and may bring about additional difficulties to market strategies. For example, in some food/beverage sectors, prior to any change in the label, there needs to be previous approval from the competent institutions, and this limits the strategic tasks of the respective companies, mainly when the intention is to provide something more personalised for the consumers.

Despite this regulation, the objectives of labelling to protect human health are, sometimes, compromised. The labelling text and design condition the perceptions of the consumers about food goods and services and influence their choices [ 31 ], especially when questions related to health are implicit [ 32 ]. The influence of the label design also has relevance in the perceptions and choices among children [ 33 ], where cartoon characters and nutritional statements have their importance [ 34 ].

The regional and Mediterranean labels are, in general, designed to promote marketing strategies and highlight product attributes [ 35 ]. The regional brands and respective labels are ways to highlight local food characteristics and to create value added in endogenous resources. In fact, the big challenge in some food sectors is to create value added for stakeholders, and these regional brands support the objectives to bring more value added to several operators. In general, these regional brands are umbrella products that promote other endogenous goods and services.

The type of packaging has an influence on consumer perceptions about the healthfulness of the respective food. For example, milk in glass packaging is perceived as being healthier than milk packaged in a carton [ 36 ]. Packaging influences children and adults in different ways. For example, for adults, the package size and shape are important attributes, more than the information present on the labels [ 37 ]. Different generations have distinct patterns of consumption, and millennials, having a different educational environment, where social media has a great impact, have other preferences and vulnerabilities.

Nonetheless, the labelling and packaging are, in some cases, more useful in aiding consumers to identify healthier food rather than trying to influence them to buy these products [ 38 ]. In addition, the presence of cartoons on packages positively influences children to choose fruit and vegetables, but this is unfortunately used more for choices of energy-dense and poor nutritional foods [ 39 ]. Cartoon characters on packaging do in fact have a great impact on children’s food choices [ 40 ]. The taste perceptions are determinant for children’s choices, and the packaging design influences these assessments. Children identify the product name, prices, and images as being the most relevant packaging characteristics for their choices [ 41 ]. The information that stimulates human sensations, such as images and songs, is powerful in influencing consumers.

Sometimes, some information on the packaging may mislead consumers about the real properties of the food chosen [ 42 ] or does not conveniently inform consumers about the nutritional characteristics [ 43 ]. This is particularly disturbing in some nutritional and health claims [ 44 ]. The messages on the packaging must be clear [ 45 ] and appropriate for what the products really are [ 46 ].

In general, researchers seem to agree on the need for some control by legislation of the information present on packaging [ 47 ], primarily that which promotes unhealthy food choices [ 48 ] in children [ 49 ]. These concerns are transversal around the world, including, for example, studies carried out in Brazil [ 50 ], Australia [ 51 , 52 , 53 ], United States (US) [ 54 , 55 ], since the 1970s [ 56 ], India [ 57 , 58 ], Philippines [ 59 ], Malaysia [ 60 ], and Ireland [ 61 ]. In any case, the decisions related to regulation towards preventing health issues should bear in mind the international commitments and consequent constraints [ 62 ].

From another perspective, health standards are sometimes not uniform across organizations and countries [ 63 ]. This may create additional difficulties for the producers and retailers who operate in international markets. It could be important, for example, in the context of the World Trade Organization or the World Health Organization, to find transversal standards for the domains relative to healthy food attributes.

3.3. Marketing Strategies

Food marketing is an important tool [ 64 ] to build and maintain markets through the creation of ties of confidence and loyalty between the producers/sellers and the consumers. Food marketing is dependent on several different dimensions, especially those related to the particularities of the sectors associated with food goods and services; in this way, the marketing plans are no easy task [ 65 ].

In any circumstance, the marketing of food as an external factor which influences consumer choices [ 66 ] is a powerful instrument that may be used to promote public campaigns, such as those related to healthy eating [ 67 ] across the several points of food sale, including restaurant kids’ menus [ 68 ] and supermarkets [ 69 ]. However, for companies, the trade-off between health and profit is not easy to solve and this is visible in many of the strategies adopted.

For example, supermarket checkout areas are especially strategic for marketing plans and deserve special attention in terms of their impact upon human health [ 70 ]. From another perspective, the tie-in offers in fast food menus for children could be restricted to healthy promotions [ 71 ]. The same concern could be present when sport celebrities are associated with the marketing plans [ 72 ] for children and parents [ 73 ] or in the criteria used to choose sport sponsors [ 74 ]. In turn, in the definition of marketing approaches, the message for healthy food promotions should be clear, well designed, and well oriented [ 75 ] to avoid misunderstandings [ 76 ], principally by children [ 77 ], as well as to obtain the intended objectives [ 78 ].

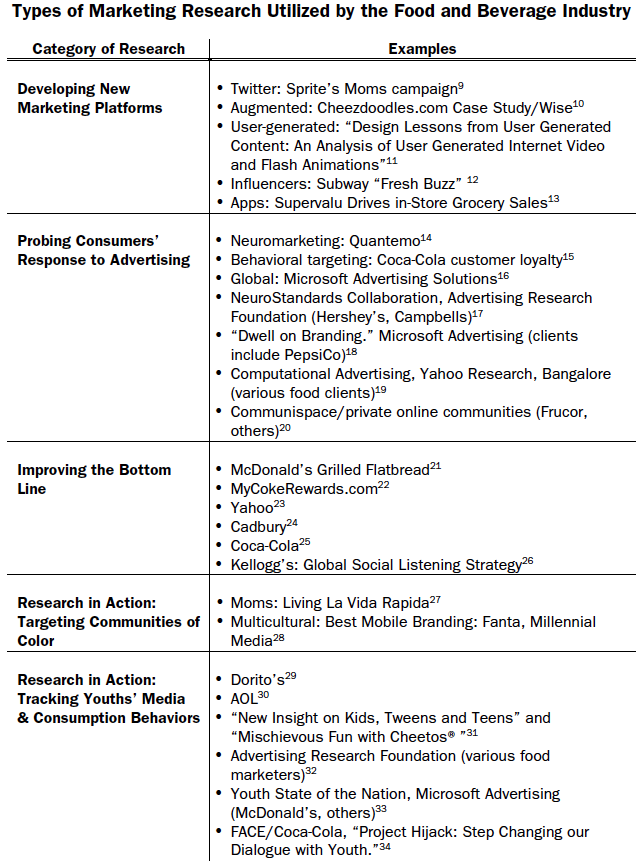

The media is a determinant way to communicate with consumers [ 79 ], which calls for adjusted advertising when it comes to promoting healthy consumption. However, often times, the consumers, especially youths, are not prepared to deal with these aggressive forms of publicity [ 80 ] and are not able to decide on the most important information [ 81 ], explicitly that which is related to nutritional characteristics [ 82 ]. In fact, the youth and children who are more engaged with, for example, social media are more vulnerable to being influenced into buying unhealthy food [ 83 ].

The marketing strategies designed by food operators are very persuasive, and this implies that the consumers who are exposed to food marketing campaigns seem to be more prone to agreeing with their strategies, including those for unhealthy food choices [ 84 ]. The television and internet seem to be the most powerful ways to influence exposed consumers [ 85 ], specifically through neuromarketing approaches which encourage children to favour taste when making food choices [ 86 ]. Television cooking shows are particularly influential on the consumption patterns of children and the youth [ 87 ]. The same happens on children’s websites [ 88 ] and social media [ 89 ]. The taste is, indeed, a decisive ingredient in food marketing strategies [ 90 ] and, usually, food marketing uses contexts related to this attribute to design its plans and influence customers.

Neuromarketing is an emergent technique that applies approaches to measure spontaneous reactions [ 91 ], with relevant impacts on the consumers’ choices [ 92 ], especially on young people [ 93 ]. The songs, image sequence, and colour are tools usually considered to support neuromarketing policies [ 94 ]. The evolution of these approaches allows for current expressions such as “musical flavour” to be normal and accepted by the several stakeholders [ 95 ]. Usually, consumers are influenced in their consumption without any perception of this factor. The stimuli for human senses have a strong impact on the consumers’ perceptions, and these tools are used to intentionally encourage consumers by marketing professionals in a subconscious way.

Magazines, as well as television and the internet, are powerful ways to advertise to consumers [ 96 ], sometimes in a more persuasive way [ 97 ]. This is because, in some cases, the control approaches are more focused on television and the internet, whilst the written forms of advertisement are forgotten about although they do have similar tools to influence consumers.

The several strategies related to food marketing have an impact on dietary choices, consumption preferences, and cultural values [ 98 ]. These changes in the pattern of consumption, as a consequence of food marketing, are particularly visible in countries that became more vulnerable to external advertisements, due to political, social, or a conjuncture of changes. In any event, a familiar environment and parents’ behaviour have a determinant impact on the several food choices [ 99 ].

An emerging area in the marketing of food is the guilt-free approach [ 100 ]; however, this a multidisciplinary field where several disciplines are called upon to add their contributions. It is important to find food marketing strategies that combine the profit aims of the companies with the health of consumers [ 101 ].

3.4. Agriculture and Food Industry

The food industry is interlinked with the agricultural sector, making this sector and its marketing strategy dependent on the options made by the farmers [ 102 ], specifically, in terms of farming practices compatible with the environment and animal welfare [ 103 ], as well as with the safety of the products themselves [ 104 ]. For example, organic farming products may have for the food markets a set of virtues and advantages, relative to conventional agriculture, but may also bring about a set of barriers and difficulties (because of the higher prices, for example) [ 105 ]. In any case, farming practices which are compatible with the environment will be the future in many countries around the world, especially in the European Union member-states. In fact, the several measures of the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP), mainly since 1992, have gone in this very direction. Due to structural and environmental problems, the CAP since 1992 has become more directed towards promoting sustainable development in an integrated rural approach, where the agri-environmental (organic farming, integrated production, etc.) measures have gained more relevance. The recent instruments created in the CAP framework, such as Greening, are examples of an agricultural policy which is more concerned about the environment within the European context [ 106 , 107 ].

Nonetheless, the food industry is an interesting way to bring about value added to agriculture, because, in farms, due to their characteristics, marketing strategies have, in certain circumstances, less importance in the market than other factors [ 108 ]. Agriculture as a sector of food commodities has additional difficulties in order to be presented into the market in a differentiated way, and this compromises marketing strategies.

The Protected Designation of Origin (PDO) products and the associated producers’ organizations are examples that may support some market differentiation and provide more structured and effective marketing strategies [ 109 ]. These PDO and the respective certification brands allow for the protection of local and regional food attributes and are interesting tools to create marketing strategies common to the respective stakeholders. Of course, the PDO brands are not the same as individual trademarks, but may bring interesting contributions, primarily for smaller farmers, for example, with more budgetary difficulties to implement strategies complementary to production techniques, to create value added in the markets, and to increase their income.

The broad diversity of farms, in terms of size, characteristics, and organization, makes the agricultural sector specific, with particular dynamics that influence the strategies adopted for food marketing [ 110 ]. The different programmes and policies designed for the agricultural sector have relevant impacts on the agriculture industry’s dynamics [ 111 ] and implicitly on the respective markets [ 112 ]. This has been a concern for the several policymakers and policy design in the European Union context bearing in mind these agricultural market characteristics, but it continues to require some further adjustments for some local particularities.

Local markets appear, in general, as great opportunities for farmers who have achieved consumer preference or loyalty, principally in terms of quality [ 113 ]. These local markets are relevant ways to shorten the agricultural chain. In certain circumstances, consumers are willing to pay more for local food [ 114 ]. Usually, the greater margin of value added in agricultural markets remains with the intermediaries and the retailers. Local markets and short agri-food chains (farm events, farm tourism, farm shops, etc.) may support farmers to maintain a large part of the total amount of value added generated in the markets. Nonetheless, the channels used in the markets depend, in some cases, on their structural characteristics, mainly those linked with their experience in the sector [ 115 ].

In the agricultural food industry market, questions sometimes appear such as those related to patriotism, where dimensions associated with food safety may contribute to adjusted marketing strategies that provide support to overcome these aspects [ 116 ]. Consumers are concerned with the health impacts of food consumption and, in this way, are sensitive to claims associated with food safety.

For an effective marketing plan in the agricultural sector, considering their specificities, the associations and cooperatives are fundamental, when well managed and organised. However, sometimes, the management structure of these organizations is not the best adjusted, and this has consequences on the sector’s performance [ 117 ]. The associations and cooperatives are crucial for technical support to the farmers and to concentrate the agricultural supply of the farmers who have worse conditions and dimensions in terms of storing production. On the other hand, the output concentration allows further capacity to negotiate contracts and prices with retailers.

The new technologies of information and communication may be useful tools to support marketing strategies in farms, and some farmers are indeed willing to pay for electronic platforms [ 118 ]. Social media is one of the cheaper and easier ways to promote food products, and this may be used without relevant difficulties by the several stakeholders. Some years ago, publicity and advertising were expensive and restricted to the traditional means of communication, such as television, radio, newspapers, and magazines.

3.5. Market Segments

Food markets are characterised by heterogeneous segments of consumers [ 119 ], involving a great diversity of realities [ 120 ], some more sensitized to health statements and others more influenced by nutritional information [ 121 ]. These contexts bring about interesting challenges for the marketing professional and for researchers, due to the great number of brands that operate in these markets. This diversity implies that food markets could be segmented considering food features, sales structure, and consumer characteristics [ 122 ].

Insufficient nutritional information seems to be one of the main factors that, in some segments, hinders the prevention of unhealthy food consumption [ 123 ]. This is particularly alarming in countries with a lower income [ 124 ]. Children and low-income consumers are vulnerable segments to persuasive and targeted marketing campaigns: children because of their lower skills to deal with marketing strategies to sell more and low-income consumers because of their vulnerability to lower-priced products.

As a result of these frameworks, the terms used to describe the nutritional dimensions, targeted at specific segments, need proper regulation, since the personal perceptions of consumers concerning the real definition of these expressions are not consensual [ 125 ] and this, therefore, opens up an element of free will for the marketing designers/strategists.

In some segments, the perceptions about food safety are more important for consumer choices than their socioeconomic characteristics [ 126 ]. In a similar pattern, consumers are, in some cases, prepared to pay more for beneficial health claims than for nutritional claims [ 127 ]. Nonetheless, the consumer’s choices of food with heath claims are, in general, interrelated with several factors, such as those related with the socioeconomic domains [ 128 ]. Depending on the segments considered, the food choices may be influenced by personality, health, sensory attributes, price, and convenience [ 129 ], as well as, by environmental, ethnic, and cultural contexts [ 130 ].

More adjusted regulations may support the promotion of more healthy advertising to more vulnerable segments [ 131 ]. However, there are areas that need to be worked on, across several segments, concerning regulations, recommendations, and policies. Some of these dimensions that deserve special attention are the accuracy [ 132 ] and the perception [ 133 ] of consumers relative to these fields associated with healthier food. The main fields to be considered by regulations to promote a healthier choice by children are the usual persuasive techniques such as promotional offers, nutrition and health claims, and appeals towards taste and fun [ 134 ].

Tourism is an important market segment that may bring significant contributions to food marketing strategies, considering the several interrelationships between the associated sectors in these interlinkages [ 135 ]. The relationships between food and tourism are well known and strong, and they should be considered in joint strategies to promote the two sectors in an integrated way. Nonetheless, the externalities that may be created in this common strategy could also spread positive effects to other sectors (transport, support services, etc.).

3.6. Social Dimensions

The interlinkages between the social responsibility of firms and the market response to the respective consumers are positive [ 136 ]; however, the traditional consumer determinants, such as the price, continue to be relevant [ 137 ]. The strong impacts from the level of prices on consumer choices are particularly problematic in lower-income countries and consumer segments [ 138 ]. Knowledge about price relevance in consumer choice may be further considered so as to promote heathy strategies and be complemented with nutritional education [ 139 ]. Adjusted educational campaigns are fundamental for a healthier food choice [ 140 ] and lifestyles [ 141 ], mainly for young people [ 142 ] to obtain critical skills [ 143 ] in making more informed decisions [ 144 ]. Educational campaigns to inform and create skills in consumers to deal with the abundance in daily advertisements are crucial in preventing health problems related to ill-informed consumption, mostly those related to obesity and diabetes. Another question concerns lifestyles that need to be adjusted in order to be healthier and prevent other diseases associated with an unbalanced diet. Cancers and cardiovascular diseases are examples of civilizational diseases related to population lifestyles and social contexts. The media could better support these healthier campaigns [ 145 ], considering its influence on adolescents [ 146 ], for example, in terms of food choices [ 147 ].

On the other hand, it is important to increase the social conscientiousness of the companies which support self-regulatory approaches. Public health policies may play an important role here to influence companies to voluntarily improve their social responsibility concerning the negative implications of marketing practices that promote the consumption of unhealthy foods [ 148 ]. Sugar and salt are among the main nefarious ingredients in unhealthy products [ 149 ], having several impacts on society’s dynamics, and they are sometimes presented on packaging along with other information in a misleading way [ 150 ]. The design of adjusted healthy food policies needs multidisciplinary approaches [ 151 ] that consider the several human dimensions [ 152 ], in which, of course, health professionals should be included [ 153 ]. Scientific research may also bring about significant insight and support here [ 154 ]. Children’s health, changing industry practices, intervention from public institutions, and consumer support are all consensual dimensions for the several stakeholders to promote healthier food production and choice [ 155 ].

Social condition has a great impact on food choices [ 156 ]. Indeed, the social and economic contexts have direct implications on the amount of income available to consume and on the level of prices afforded. However, in some cases, retailers are not clearly informed about the impacts of the price changes on their sales [ 157 ]. Food may also be used as an expression of social identity and a way to make a difference from the mainstream [ 158 ].

In general, food choice patterns followed by consumers are similar to those considered in other decisions of their lives [ 159 ]. In fact, consumers concerned with sustainability tend to consume foods of a higher quality and are less vulnerable to promotional advertisements [ 160 ]. The consumption patterns of these more sustainable consumers may be considered by, for example, policymakers as benchmarks and practices to be spread over other social segments. It is important to know the several dimensions related to food choices and consumption in order to promote more balanced lifestyles. For example, Chinese teenagers are influenced, in their food choices, by personal, family, peer, and retailer frameworks and the following features were highlighted as influencing their options: nutrition, safety, taste, image, price, convenience, and fun [ 161 ]. The social dimensions around the world are very different, and any adjusted approach needs to consider and be aware of the local particularities.

3.7. Brand and Branding

Brands and branding are fundamental instruments for an effective marketing plan in each step of the food chain [ 162 ]. From production to retailers’ markets, brands are crucial to create value added and to differentiate products from their competition. Only with brands is it possible to carry out a marketing strategy across all dimensions.

Commercial brands are more important for the brand-schematic consumers than for brand-aschematic consumers. The brand-aschematic consumers, in wine markets, for example, give greater importance to the Protected Designation of Origin label and the associated categories [ 163 ]. The wine market is a very complex context, due to its great number of individual and certified brands. Markets with a great diversity of brands may confuse consumers when they want to make a choice. In these cases, the main challenge is to have a brand that may be easily identified, amongst many others, and be positioned in the mind of the customers. Consumers, in general, maintain two brands by category in their minds, and the great task is to be included as one of these two brands. Here, positioning approaches are crucial for an efficient branding [ 164 ].

Credence features are decisive for the marketing of food, and the brand itself is among these characteristics jointly with organic foods, health, and ingredients [ 165 ]. The branding processes usually create ties of confidence and loyalty with consumers to maintain the market and the respective sales. These dimensions distinguish the concerns and objectives of sales technicians from marketing professionals. In addition, the scientific literature highlights that consumer satisfaction is interrelated with their behaviour and loyalty [ 166 ], showing that consumer loyalty is, indeed, a central dimension in marketing strategies and that brands are crucial in creating ties of confidence [ 167 ]. However, loyalty and satisfaction of consumers are, also, influenced by their lifestyle and personality [ 168 ].

Iconic and old brands, such as Coca-Cola, are examples of market drivers [ 169 ] and may bring important contributions for strategic plans to lead consumers towards a more adjusted and healthy consumption, principally among children and youths. On the other hand, the display of brand characters has an important impact on consumer choice, and this deserves special attention from the several stakeholders for healthier food consumption [ 170 ].

4. Discussion and Conclusions

The study presented here aimed to highlight the main contributions from the literature concerning the dimensions related to the interrelationships between food marketing and consumer choice. For this purpose, 147 documents from the Scopus database were considered in a search carried out on 16 October 2020 for the topics “food marketing” and “choices”. These documents were first analysed through bibliographic characterisation and after surveyed by literature review.

The bibliographic data reveals that there are opportunities to explore regarding these topics, considering the annual average number of documents published, the subject areas addressed, and the countries of the authors’ affiliation. On the other hand, there is great relatedness between food marketing and human obesity, especially in young people. In fact, the literature review highlighted that there is a great concern from several stakeholders about the impact of marketing strategies on the health of children and adolescents.

The literature review may be summarised in a SWOT (strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats) analysis approach, to better highlight the main insights, principally considering food marketing and consumer choice when building the matrix (see Figure 6 ).

SWOT (strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats) analysis to summarise the literature review.

Figure 6 shows that adjusted food image and name approaches, interrelated with the label, packaging, and brand, are crucial for a successful marketing strategy [ 6 ]. However, these powerful marketing instruments are often used by companies, through the media, to promote unhealthy food, especially for children and adolescents [ 49 ]. In parallel, new technologies and social media offer new and attractive opportunities for smaller operators, opening up new channels for them to communicate with consumers [ 118 ]. Nonetheless, these smaller stakeholders may be those most affected by restrictive policies to mitigate negative food marketing impacts on consumer health [ 47 ].

Traditionally, prices are amongst the most influential factors that condition consumption, including food choices, and the economic theory confirms this influence. Nonetheless, there are specific segments and new tendencies where quality, healthy attributes, and sustainability aspects are emergent dimensions. The sociodemographic, cultural, and behavioural domains also play their part in food consumption and preferences. This explains, in part, the emerging importance of neurosciences in marketing plans. In the universe of food marketing and consumer choice, it is important to highlight the relevance of the agricultural sector and its particularities, in the production of commodities, which condition the definition of effective marketing plans for the entire sector.

In terms of practical implications, it seems to be consensual that food marketing strategies have relevant implications on human health, and this framework deserves special attention from several stakeholders, particularly in the design of more adjusted policies in a standard way across countries, through World Trade Organization and World Health Organization negotiations. However, these regulations should be designed in order to have the right desired effect and avoid worsening the fragile context of smaller producers.

For future studies, it would be advisable to survey several stakeholders with regard to suggestions for designing new and efficient policies and regulations, so as to obtain a more adjusted regulatory framework and increase the operators’ compliance.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the CERNAS Research Centre and the Polytechnic Institute of Viseu for their support.

This work is funded by National Funds through the FCT—Foundation for Science and Technology, I.P., within the scope of the project Refª UIDB/00681/2020.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

- Open access

- Published: 27 July 2022

A scoping review of outdoor food marketing: exposure, power and impacts on eating behaviour and health

- Amy Finlay 1 ,

- Eric Robinson 1 ,

- Andrew Jones 1 ,

- Michelle Maden 2 ,

- Caroline Cerny 1 , 3 ,

- Magdalena Muc 1 ,

- Rebecca Evans 1 ,

- Harriet Makin 1 &

- Emma Boyland 1

BMC Public Health volume 22 , Article number: 1431 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

5414 Accesses

13 Citations

42 Altmetric

Metrics details

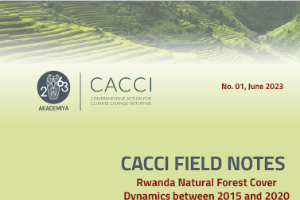

There is convincing evidence that unhealthy food marketing is extensive on television and in digital media, uses powerful persuasive techniques, and impacts dietary choices and consumption, particularly in children. It is less clear whether this is also the case for outdoor food marketing. This review (i) identifies common criteria used to define outdoor food marketing, (ii) summarises research methodologies used, (iii) identifies available evidence on the exposure, power (i.e. persuasive creative strategies within marketing) and impact of outdoor food marketing on behaviour and health and (iv) identifies knowledge gaps and directions for future research.

A systematic search was conducted of Medline (Ovid), Scopus, Science Direct, Proquest, PsycINFO, CINAHL, PubMed, the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials and a number of grey literature sources. Titles and abstracts were screened by one researcher. Relevant full texts were independently checked by two researchers against eligibility criteria.

Fifty-three studies were conducted across twenty-one countries. The majority of studies ( n = 39) were conducted in high-income countries. All measured the extent of exposure to outdoor food marketing, twelve also assessed power and three measured impact on behavioural or health outcomes. Criteria used to define outdoor food marketing and methodologies adopted were highly variable across studies. Almost a quarter of advertisements across all studies were for food (mean of 22.1%) and the majority of advertised foods were unhealthy (mean of 63%). The evidence on differences in exposure by SES is heterogenous, which makes it difficult to draw conclusions, however the research suggests that ethnic minority groups have a higher likelihood of exposure to food marketing outdoors. The most frequent persuasive creative strategies were premium offers and use of characters. There was limited evidence on the relationship between exposure to outdoor food marketing and eating behaviour or health outcomes.

Conclusions

This review highlights the extent of unhealthy outdoor food marketing globally and the powerful methods used within this marketing. There is a need for consistency in defining and measuring outdoor food marketing to enable comparison across time and place. Future research should attempt to measure direct impacts on behaviour and health.

Peer Review reports

Advertising of foods and non-alcoholic beverages, (hereafter food advertising), particularly for items high in fat, salt and/or sugar (HFSS), has been identified as a factor contributing to obesity and associated non-communicable diseases globally [ 1 ]. People from more deprived backgrounds or ethnic minority groups are disproportionately targeted and exposed to greater food marketing across a range of platforms [ 2 ], and this may contribute to social gradients in obesity and associated health inequalities [ 3 ]. Marketing is defined by the American Marketing Association (AMA) as “the activity, set of institutions, and processes for creating, communicating, delivering, and exchanging offerings that have value for customers, clients, partners, and society at large” [ 4 ], and advertising is a key aspect of marketing, which seeks to “inform and/or persuade members of a particular target market or audience regarding their products, services, organizations or ideas” [ 5 ]. The World Health Organization (WHO) assert that the impact that food marketing has on consumer behaviour is dependent on both ‘exposure’ and ‘power’ [ 6 ]. Exposure is the frequency and reach of the marketing messages and power is the creative content and strategies used, both of which determine the effectiveness of marketing [ 6 ]. Hierarchy of effects models of food marketing consider that the pathways for these effects are likely to be complex [ 7 ], with evidence demonstrating that food marketing impacts food purchasing [ 8 ], purchase requests [ 9 ], consumption [ 10 , 11 ] and obesity prevalence [ 12 ].

Evidence suggests that children are likely to be more vulnerable to marketing messages than adults [ 13 , 14 , 15 ]. Furthermore, it has been proposed that the scepticism towards advertising that is developed in adolescence does not equate to protection against its effects [ 16 ], leaving both young children and older adolescents vulnerable to the effects of food marketing [ 17 ]. For this reason, policies enacted generally aim to decrease the exposure or power of food marketing to children, and so this is where much of the research is focused. Despite this, it is apparent that adults are similarly affected by food marketing [ 18 ], and therefore also likely to benefit from restrictions [ 19 ].

In 2010, WHO called on countries to limit the marketing of unhealthy foods, specifically to children [ 6 ]. Various policies have since attempted to enforce restrictions on HFSS advertisements [ 20 ], however, restrictions outdoors remain scarce [ 21 ] and implementation and observation of such restrictions has been found to be inconsistent and problematic [ 22 ].

Previous reviews have collated the evidence on the exposure, power and impact of food advertising on television [ 23 , 24 , 25 ], advergames [ 26 , 27 ], sports sponsorship [ 28 , 29 ] and food packaging [ 30 , 31 ] and in some cases across a range of mediums [ 2 , 32 ]. An existing scoping review [ 33 ] documents the policies in place globally to target outdoor food marketing, and the facilitators and barriers involved in implementing these policies. The lack of effective policies for outdoor food marketing may reflect the comparatively little evidence or synthesis of evidence on outdoor marketing or its potential role in contributing to overweight and obesity, relative to that for other media. Additionally, there are challenges in measuring outdoor marketing exposure compared to television and online [ 34 ]. As countries such as the UK and Chile [ 35 ] move to strengthen restrictions on unhealthy food marketing via television, digital media and packaging, it is plausible that advertisements will be displaced to other media such as outdoor mediums so that brands can maintain or increase their exposure [ 36 , 37 ].

Despite being a longstanding and widely used format [ 38 ] there is no agreed definition for outdoor food marketing. This may have implications for the comparability of data across study designs, which has been reported as a limitation in previous reviews [ 11 , 39 ]. Identifying the common criteria used to define outdoor food marketing, alongside considering best practice methodologies for outdoor marketing monitoring and impact research, are important steps to support the generation of robust, comparable evidence to underpin public health policy development.

Given that 98% of people are exposed to outdoor marketing daily [ 40 ], it is an efficient form of marketing for brands [ 41 ], and is likely successful in influencing purchase decisions through targeting potential shoppers in places the brands are sold [ 42 ]. Food marketing through media such as television and advergames have been shown to impact eating and related behaviours such as purchasing [ 43 , 44 , 45 , 46 ], and the evidence on this marketing and body weight has satisfied the Bradford Hill Criteria [ 47 ], which is used to recognise a causal relationship between two variables. However, the impact that outdoor marketing has on eating related outcomes is less clear.

Therefore, this scoping review aims to (i) identify common criteria used to define outdoor food marketing, (ii) summarise research methodologies used, (iii) identify available evidence on the exposure, power (i.e. persuasive creative strategies within marketing) and impact of outdoor food marketing on behaviour and health with consideration of any observed differences by equity characteristics such as socioeconomic position and (iv) identify knowledge gaps and directions for future research.

Given the broad objectives, a scoping review [ 48 ] was conducted and reported in accordance with the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) methodology for scoping reviews [ 49 ] and the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR) [ 50 ]. The review was pre-registered on the Open Science Framework ( https://osf.io/wezug ).

Search strategy

A detailed search strategy was created by the research team (see supplementary material 1 ), which included an experienced information specialist (M.Ma), to capture both published and unpublished studies and grey literature. Search terms related to food, outdoor and marketing were developed based on titles and abstracts of key studies (identified from preliminary scoping searches) and index terms used to describe articles. For grey literature sources simple terms “outdoor food marketing” and “outdoor food advertising” were used. Searches were conducted between 21st January and 10th February 2021.

Databases searched for academic literature included Medline (Ovid), Scopus, Science Direct, Proquest, PsycINFO, CINAHL, the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials. An additional supplementary PubMed search was conducted to ensure journals and manuscripts in PubMed Central and the NCBI bookshelf were captured. Grey literature searches were conducted of databases Open Access Theses and Dissertations, OpenGrey, UK Health Forum, WHO and Public Health England. Other searches for grey literature included government websites (GOV.uk), regulatory and industry body websites (World Advertising Research Centre Database, Advertising Standards Authority) and NGO sites (Obesity Health Alliance, Sustain).

Eligibility criteria

Primary quantitative studies assessing marketing of food and non-alcoholic beverage brands or products encountered outdoors in terms of exposure, power or impact were considered for inclusion. We defined both marketing and advertising as per the AMA definitions [ 4 , 5 ].

Examples of outdoor marketing included billboards, posters, street furniture and public transport. Exposure was defined as the volume of advertising identified, with consideration of the brands and products promoted. Power of outdoor marketing was defined as the strategies used to promote products (e.g. promotions, characters) [ 51 ]. Eligible behavioural impacts of outdoor marketing were food preference, choice, purchase, intended purchase, purchase requests and consumption. Health-related impacts were body weight and prevalence of obesity or non-communicable diseases. Non-behavioural outcomes were ineligible, e.g., brand recall, awareness, or attitudes.

Studies in which outdoor marketing could not be clearly isolated from other marketing forms [ 46 ], or food could not be isolated from other marketed products (e.g. alcohol and tobacco) were excluded. Studies of health promotion (e.g., public health campaigns) were ineligible. Qualitative studies and reviews were not eligible for inclusion; however, reference lists of relevant reviews were searched.

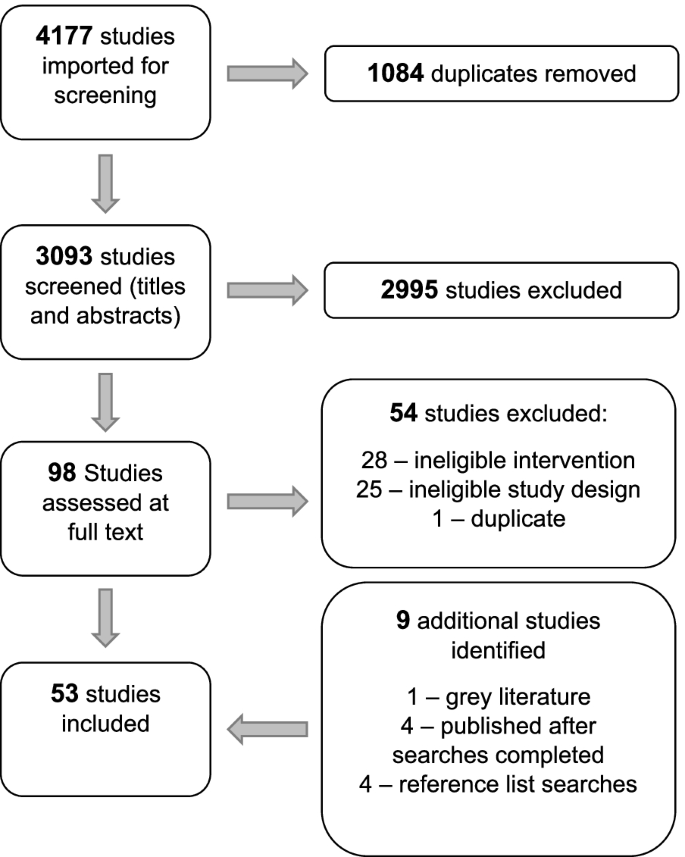

Selection of sources of evidence

The full screening process is shown as a PRISMA flow diagram (Fig. 1 ). Titles and abstracts were screened by one researcher (AF). Full text review was conducted independently by two researchers from a pool of four (AF, M. Mu, RE & HM). Disagreement was resolved by discussion and where necessary ( n = 4 articles) a third reviewer (EB) was consulted. Covidence systematic review software was used to organise the screening of studies. Inter-rater reliability for the full-text screening was high, with estimated agreement of 95.7% and a Kappa score of 0.91.

PRISMA flow diagram

Data charting

The extraction template was developed and piloted prior to data extraction. For more detail on the information extracted from each article see supplementary material 2 . Discrepancies in extraction were resolved by discussion. As the aim was to characterise and map existing literature and not systematically review its quality, as is common in scoping reviews [ 52 ] quality assessment (e.g. risk of bias) was not undertaken.

Synthesis of results

Studies that defined outdoor food marketing were grouped to identify common criteria used in definitions. Methodologies used to measure exposure, power and impact are summarised. Studies were grouped into exposure, power and impact for synthesis, with relevant sub-categories to document findings related to equity characteristics. We deemed foods classed as “non-core”, “discretionary”, “unhealthy”, “less healthy”, “junk”, “HFSS”, “processed”, “ultra-processed”, “occasional”, “do not sell”, “poorest choice for health”, “less healthful”, “ineligible to be advertised”, and “not permitted” as unhealthy.

Study selection

After removal of duplicates from an initial 4177 records, 3093 records were screened. Ninety-eight articles were then full-text reviewed. Fifty-four studies were excluded here (supplementary material 3 ). After grey literature and citation searches, the final number of included studies was 53.

Characteristics of included studies

All studies ( n = 53) measured exposure to outdoor food marketing, n = 12 also measured power of outdoor food marketing, and n = 3 measured impact. N = 15 studies provided at least one criterion through which outdoor food marketing was defined, beyond stating the media explored.

Studies were conducted across twenty-one countries, the majority took place in the USA ( n = 16) [ 53 , 54 , 55 , 56 , 57 , 58 , 59 , 60 , 61 , 62 , 63 , 64 , 65 , 66 , 67 , 68 ], and other high-income countries ( n = 23) as categorised by the world bank [ 69 ] (Tables 1 , 2 and 3 ).

Of studies including participants ( n = 7), three measured exposure of children between the ages of 10 and 14 [ 89 , 93 , 102 ], two surveyed caregivers of children aged 3–5 [ 70 ] (79.2% mothers) and 0–2 years [ 85 ] (100% mothers) and two studies collected data from adults in select census tracts [ 53 , 71 ].

What common criteria are used to define outdoor food marketing?

As shown in Tables 1 , 2 and 3 , the majority of studies ( n = 33) encompassed a combination of outdoor media [ 53 , 54 , 55 , 58 , 60 , 61 , 62 , 65 , 66 , 67 , 68 , 72 , 73 , 75 , 76 , 78 , 79 , 80 , 80 , 81 , 82 , 83 , 84 , 87 , 88 , 89 , 91 , 92 , 94 , 97 , 98 , 102 , 103 , 104 ]. Many ( n = 11) focused on advertising solely on public transport property [ 64 , 70 , 71 , 86 , 90 , 93 , 95 , 99 , 100 , 101 , 106 ], five studies focused exclusively on billboards [ 63 , 74 , 77 , 85 , 96 ] and four measured advertising outside stores or food outlets [ 56 , 57 , 59 , 105 ].

Outdoor food marketing was inconsistently defined across studies. All studies stated the media they were measuring and some defined marketing or advertising generally, but often not how it related to the outdoor environment. Studies that provided specific criteria for outdoor food marketing ( n = 15) or an equivalent term (i.e. outdoor food advertising) beyond simply stating the media recorded are listed in Table 4 . Figure 2 represents the criteria referred to most frequently when defining outdoor food marketing.

Common criteria used to define outdoor food marketing

What methods are used to document outdoor food marketing exposure, power, and impact.

Most included studies ( n = 49) were cross-sectional, although four were longitudinal [ 68 , 90 , 95 , 100 ]. The methods used to classify foods were inconsistent, for example, often local nutrient profiling models were used to classify advertised products as healthy or not healthy (e.g. [ 80 ]), however in some cases the number of advertisements for specific food groups were tallied (e.g. [ 56 ]). Forty-two studies assessed the frequency of food advertising through researcher visits to locations. In four [ 82 , 83 , 86 , 93 ] studies, researchers visited streets virtually, through Google Street view. Real, rather than potential exposure was measured in three studies [ 89 , 93 , 102 ]. In two cases, children wore cameras which documented advertisements encountered in their typical day [ 89 , 102 ], and in a final study, children wore a global positioning system (GPS) device so researchers could track when they encountered previously identified advertisements [ 93 ]. Self-reported retrospective exposure (frequency of encountering outdoor food advertising) was measured in three studies [ 70 , 71 , 85 ].

When measuring advertising around schools/places children gather, researchers typically created buffer zones, ranging from 100 m [ 81 ] to 2 km [ 105 ], with 500 m being the most frequent buffer size ( n = 8) [ 77 , 78 , 86 , 87 , 88 , 95 , 97 , 104 ]. Four studies used multiple buffers [ 82 , 87 , 93 , 97 ], allowing for comparison between the area directly surrounding a school (e.g. < 250 m) with an area further away (e.g. 250-500 m) [ 87 ], one study compared advertising in Mass Transit Railway stations in school and non-school zones [ 90 ], and another used GPS point patterns to determine the extent of advertising around schools [ 92 ].

Content analysis was used to characterise the food types promoted and strategies used in the advertising. Two studies investigated price promotions [ 55 , 56 ], two identified promotional characters and premium offers [ 75 , 78 ], one specifically assessed child-directed marketing [ 57 ]. Others examined a mix of strategies including sports or health references, cultural relevance and emotional, value or taste appeals [ 54 , 73 , 74 , 76 , 79 ].

All three studies measuring the impact of outdoor food advertising used self-reported data. In a study conducted in Indonesia [ 70 ], caregivers reported the frequency of food advertising exposures in the past week, and their children’s frequency of intake of various confectionaries at home in the last week. In a study conducted in the US [ 53 ], individuals reported consumption of 12 oz. sodas in the last 24 hours, and odds of exposure was assessed by the extent of advertising in surrounding areas. In the UK study [ 71 ], participants reported exposure to HFSS advertising in the past week, and body mass index was calculated from participants’ reported height and weight.

What is known about exposure to outdoor food marketing?

Content of food marketing.

Fifty-three studies investigated outdoor marketing exposure (Tables 1 , 2 and 3 ), n = 22 reported specifically on exposure around schools or places children gather, n = 9 documented exposure on public transport and n = 4 outside stores/establishments. The remaining n = 21 measured exposure across multiple settings.

Food products were promoted in between 7.8% [ 64 ] and 57% [ 91 ] of advertisements, the mean across studies was 22.1%. Of food advertisements, a majority (~ 63%: range 39.3% [ 64 ] - 89.2% [ 89 ]) were categorised as unhealthy. Healthier foods were advertised far less, with studies generally reporting between 1.8% [ 97 ] and 18.8% [ 91 ] of food advertisements being for healthier products. Fast food ( n = 17) and sugar-sweetened beverages (SSBs; n = 22) were frequently n amed as some of the most advertised product types.

Coca Cola was frequently stated as the most prominent brand advertised [ 73 , 75 , 88 , 91 , 100 ]. Around 5% of all outdoor food advertisements in New Zealand [ 78 ] and Australia [ 100 ] were promoting a brand (rather than a specific product), however there were no brand only advertisements identified in a UK study [ 80 ].

Marketing to children

Over half of the studies included ( n = 29) sought to examine children’s exposure to food advertising. One UK study [ 93 ] concluded that while it was unlikely that unhealthy products were advertised on bus shelters surrounding schools (100-800 m), children, particularly in urban areas, were likely to encounter advertising on their journeys to and from school. All other studies found food advertising to be prevalent around schools, often promoting unhealthy products, although in three studies, a minority of schools (20.4% [ 78 ], 15.4% [ 79 ], 33.3% [ 103 ]) did not have any food advertising nearby. Four studies found that there was more food advertising closer to schools or facilities used by children and adolescents, compared to areas further away from these facilities [ 87 , 97 ], specifically for unhealthy or processed foods [ 87 , 90 ] and snack foods [ 82 ], however one study found SSB advertisements increased as distance from schools increased [ 92 ].

Differences by socioeconomic position/ethnicity

Eight studies considered differences in exposure by ethnicity. Three of these found that ethnic minority groups were exposed to more food advertising [ 55 , 58 , 62 ], for example, schools in the US with a majority Hispanic population were found to have more total advertisements and establishment advertisements in surrounding areas [ 55 ], whilst in New York City, for every 10% increase in proportion of Black residents there was a 6% increase in food images and 18% increase in non-alcoholic beverage images [ 58 ]. In addition to this, associations were found between sugary drink advertisement density and Percentage of Asian or Pacific Islander residents and percentage of Black, non-Latino residents [ 62 ]. Two studies found that multicultural neighbourhoods had a higher proportion of food advertisements [ 94 ] and higher density of unhealthy beverage advertisements [ 61 ]. Unhealthy food [ 63 ] and beverage [ 61 ] advertising were found to be more prevalent in ethnic minority communities. Low-income communities with majority Black or Latino residents had greater odds of having any food advertising [ 53 ], generally more food and beverage advertising and greater unhealthy food space [ 61 ] compared to white counterparts. A US study [ 56 ] found that differences in exposure to food and beverage, and soda advertisements by ethnicity were no longer significant after controlling for household income.

Twenty-six studies considered differences in exposure by SES, five of these did not find a relationship [ 60 , 71 , 83 , 93 , 99 ]. Two studies showed that food and beverage advertisements were more prevalent in low SES communities [ 56 , 94 ]. Schools characterised by low SES had a higher proportion unhealthy food advertising nearby in two studies [ 78 , 104 ], although in one instance there was no significant difference in the number of unhealthy food advertisements [ 78 ]. One study conducted in Sweden [ 84 ] found no significant difference in the proportion of food advertisements by SES, however there was a significantly greater proportion of advertisements promoting ultra-processed foods in the more deprived region.

Foods more frequently advertised in low SES areas were: SSBs, hamburgers and kebabs, diet soft drinks, vegetable snacks, dairy with no added sugar [ 103 ], staple foods [ 91 ], flavoured milk and fruit juice [ 101 ]. Low income communities in the US had lower odds of fruit and vegetable advertisements at limited service stores [ 56 ] and a higher density of unhealthy beverages [ 61 , 62 ] compared with higher-income communities.

Two studies found no significant difference in the number of core advertisements by SES [ 98 , 100 ], however a study of outdoor food advertising in Uganda found that there were more healthy food advertisements in high income areas [ 75 ]. Advertisements for fast food, takeaways, hot beverages and soft drinks were found to be more frequent in high-income areas [ 91 , 96 , 101 ].

A study comparing four schools of varying deprivation found the school with lowest deprivation had no advertisements but there was no clear trend in extent of advertising by deprivation [ 105 ]. Two studies conducted in Mexico [ 81 ] and New Zealand [ 86 ] found outdoor food advertising to be more frequent around public schools than private schools, however a study in Uganda [ 75 ] found no significant difference in the number of core foods advertised around private and government funded schools, in all three studies private school was considered a proxy of high SES. In this New Zealand study, low decile areas had the greatest number of advertisements for non-core food, core food and non-core food and beverage, however when high decile schools were combined with areas around private schools, the greatest number of all food and beverage advertisements and non-core advertisements were found in high SES areas [ 86 ].

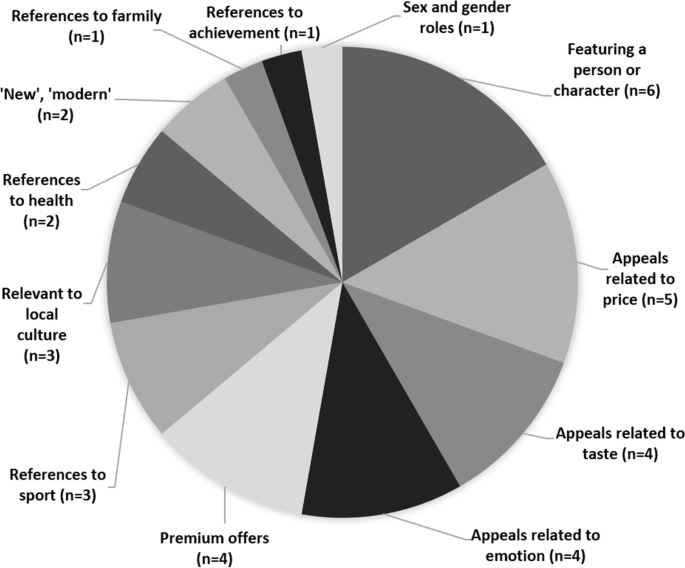

What is known about the power of outdoor food marketing?

Twelve studies documented the power of outdoor food marketing (Table 2 ). This was measured by quantifying the use of a range of persuasive creative strategies and child-directed marketing. The persuasive creative strategies observed across studies are shown in Fig. 3 .

Powerful creative strategies observed in studies

Observed power

There was evidence of variation in the use of persuasive creative strategies in outdoor advertising, with premium offers (e.g. buy one get one free [ 78 ]) utilised in between 7.84% [ 74 ] and 28.1% [ 78 ] of food advertisements, and the proportion of advertisements featuring a person or promotional character ranging from 2.8% [ 79 ] to 46.8% [ 73 ]. Other strategies frequently identified were appeals related to price [ 55 , 56 , 72 , 74 , 76 ], emotion [ 72 , 74 , 76 , 77 ] and taste [ 72 , 74 , 76 , 77 ].

The proportion of advertisements considered to be targeted just at children or young people ranged from less than 1% [ 58 ] to 10.4% [ 73 ]. Studies assessing appeals to children considered the use of cartoon characters, popular figures, child models or characters, colours or images, toys and the placement of the advertisement [ 58 , 64 , 73 , 83 ].

Often, the foods promoted using persuasive creative strategies were soft drinks [ 73 , 76 ], non-core foods [ 77 ] and fast foods [ 57 , 76 ], however one study [ 75 ] observed outdoor food advertising in Uganda and found that 15% of healthy food advertisements used promotional characters.

Differences by socioeconomic status/ethnicity

A US study [ 55 ] found that schools with a majority Hispanic population (vs. low Hispanic population) had significantly more advertisements featuring price promotions within half a mile of the school. Price promotions were also more frequent outside supermarkets in non-Hispanic Black communities in the US [ 56 ], although this was no longer significant after controlling for household income. Supermarkets in low-income communities were significantly more likely to have price promotions [ 56 ] and being located in middle-income (compared to high) and black communities was marginally associated with increased odds of child-directed marketing [ 57 ]. Sometimes, local culture was referenced in food advertising through persuasive creative strategies [ 54 , 76 , 77 ], for example a US study quantifying advertisements in a Chinese-American Neighbourhood [ 54 ] found food advertisements were frequently relevant to Chinese culture (58.9% of food and 59.04% of non-alcoholic beverage advertisements), often featuring Asian models.

What is known about the impact of outdoor food marketing?

Three studies (Table 1 ) [ 53 , 70 , 71 ] explored associations between exposure to outdoor food advertising and behavioural or health outcomes, two of these found a significant positive relationship. Lesser et al. (2013) [ 53 ] found that for every 10% increase in outdoor food advertisements present, residents consumed on average 6% more soda, and had 5% higher odds of living with obesity. In Indonesia [ 70 ] self-reported exposure to food advertising on public transport was associated with consumption of two specific HFSS products. No associations were found between exposure and consumption of the other eight products considered. A UK study [ 71 ] found no significant association between self-reported exposure to HFSS advertising across transport networks and weight status. No studies measured differences in impact in relation to equity characteristics.

Summary of main results

This review is the first to collate the criteria used to define outdoor food marketing, document the methods used to measure this form of marketing, and identify what is known about its exposure, power and impact.

Fifty-three studies were identified which met all eligibility criteria. In brief, of studies with a definition, the criteria referenced most were; on or outside stores/establishments; and stationary signs/objects. The methods used to research outdoor marketing include self-report data, virtual auditing, in-person auditing, and content analysis. There was little consistency in the approach used to classify foods as healthy or unhealthy, although nutrient profiling models were used in some studies.

Food accounted for an average of 22.1% of all advertisements, the majority of foods advertised were classed as unhealthy (63%). Ethnic minority groups were generally shown to have higher exposure to outdoor food advertising, but findings on differential exposure by SES were inconsistent.

Studies showed frequent use of premium offers, promotional characters, health claims, taste appeals and emotional appeals in outdoor food advertisements. There was limited evidence of relationships between exposure to food marketing and behavioural or health outcomes.

Eight out of fifteen studies (Fig. 2 ) stated that outdoor food marketing must be on or outside of stores or establishments, seven studies included stationary signs or objects in their definition and five studies stated that advertisements must be visible from the street or sidewalk. However, the defining criteria was inconsistent across the fifteen studies, and some of the most referenced criteria are problematic. Although stationary signage is an important aspect of outdoor marketing, this excludes forms of marketing on transport e.g. the exterior of buses. Equally, not all outdoor marketing may be “visible from the street or sidewalk”, this could exclude advertising on public transport property, i.e. station platforms. Additionally, the share of digital out-of-home advertising rose from 14% in 2011 to 59% in 2020 [ 107 ]. Three studies did aim to document digital advertising [ 60 , 63 , 90 ] through observing a digital board for a set amount of time. This medium is likely to become more prevalent over time globally, and there are challenges due to its changing and interactive nature [ 108 ]. The literature appears dominated by studies of advertising. This may reflect that most marketing encountered outdoors is advertising, conversely, it may be that the literature is yet to consider some newer forms of marketing, such as increased digital platforms. It will be important for future research to consider the evolving nature of outdoor marketing and how this should be measured.

Only fifteen studies defined outdoor food marketing as a term. This has likely been a factor influencing the heterogeneity observed across studies (e.g. differences in scope), as inconsistencies in defining a factor can negatively impact the development of an evidence base [ 109 ]. Researchers should endeavour to work towards an agreed definition, perhaps through use of the Delphi method of consensus development [ 110 ], in order to improve consistency in the resulting research. However, this method can be open to bias if the researchers are of the same background as the experts involved [ 109 ] therefore it is important that any definition developed aligns with criteria used by industry to reduce likelihood of bias.

Methods used in outdoor food marketing research

Outdoor food marketing exposure and impact were measured using self-reported data, which may lack validity, as advertising can influence brand attitudes whether consciously or unconsciously processed [ 111 ]. While it can be useful to know the extent that individuals process advertising, this may not be a true representation of exposure. Equally, participants may alter their response to appear socially desirable which has previously resulted in misreporting of height and weight data [ 112 ].

Using Google Street View as an auditing tool is beneficial in saving time and resources whilst gathering large samples [ 113 ], however almost one third of advertisements in one study were unable to be identified [ 83 ], therefore systematically searching the streets in sample areas, and taking photographs for later reference is a more reliable method. Buffer areas are a useful tool for measuring advertising, particularly around specific sites such as schools, although stating advertising was present “around schools” has different meanings when comparing 100 m to 500 m, or to 2 km. GPS and wearable camera technology can identify how individuals encounter food marketing in the routes they use to travel through their environment. These methods should be replicated globally as a more objective measure of individual exposure to outdoor food marketing, although care must be taken in regard to privacy and ethical considerations.

There was little consistency in the methods used to identify persuasive creative strategies, which is typical in the field of food marketing [ 23 ]. The heterogeneity observed could be reduced through adherence to protocols for the monitoring of food marketing such as those developed by WHO [ 51 ] and INFORMAS [ 114 ]. This would improve comparability of future outdoor food marketing data across countries and time points which would better support policy action in this area. Nutrient profiling models are a useful tool for food categorisation, as opposed to grouping foods as “everyday” and “discretionary” or “core” and “non-core”, however, profiling models differ due to cultural differences in diet [ 106 , 115 ]. There is a need to balance the data required for country-level policy relevance with international comparability. Watson et al. (2021) [ 106 ] propose an amalgamation of the WHO EURO NPM and WHO Western Pacific models.

Exposure to outdoor food marketing