Open Access is an initiative that aims to make scientific research freely available to all. To date our community has made over 100 million downloads. It’s based on principles of collaboration, unobstructed discovery, and, most importantly, scientific progression. As PhD students, we found it difficult to access the research we needed, so we decided to create a new Open Access publisher that levels the playing field for scientists across the world. How? By making research easy to access, and puts the academic needs of the researchers before the business interests of publishers.

We are a community of more than 103,000 authors and editors from 3,291 institutions spanning 160 countries, including Nobel Prize winners and some of the world’s most-cited researchers. Publishing on IntechOpen allows authors to earn citations and find new collaborators, meaning more people see your work not only from your own field of study, but from other related fields too.

Brief introduction to this section that descibes Open Access especially from an IntechOpen perspective

Want to get in touch? Contact our London head office or media team here

Our team is growing all the time, so we’re always on the lookout for smart people who want to help us reshape the world of scientific publishing.

Home > Books > Parenting in Modern Societies

The Impact of Dysfunctional Families on the Mental Health of Children

Submitted: 24 January 2023 Reviewed: 15 February 2023 Published: 21 June 2023

DOI: 10.5772/intechopen.110565

Cite this chapter

There are two ways to cite this chapter:

From the Edited Volume

Parenting in Modern Societies

Edited by Teresa Silva

To purchase hard copies of this book, please contact the representative in India: CBS Publishers & Distributors Pvt. Ltd. www.cbspd.com | [email protected]

Chapter metrics overview

578 Chapter Downloads

Impact of this chapter

Total Chapter Downloads on intechopen.com

Total Chapter Views on intechopen.com

Overall attention for this chapters

A healthy and nurturing family environment is necessary for the development of mental health in children. A positive atmosphere within the family, such as open communication, strong interpersonal relationships between parents and children, harmony and cohesion, contributes to a conducive and a safe space for children to develop healthy habits. Children who grow up in dysfunctional families are at risk of developing mental illness, which, if not treated, can result in long-term mental health problems such as depression and anxiety. Children who are exposed to constant conflict, aggression, abuse, neglect, domestic violence and separation because of divorce or parents who work long hours away from home are likely to present with behavioural and emotional problems. Parents, whether single, married or divorced, have got the responsibility to protect their children’s mental health.

- dysfunctional families

- mental health

- mental illness

- parent-child relationship

- parental practices

Author Information

Lucy kganyago mphaphuli *.

- The National Prosecuting Authority, Witness Protection Programme, Pretoria, South Africa

*Address all correspondence to: [email protected]

1. Introduction

Mental health of children is a global and persistent concern. It is a multifaceted problem with some of the leading courses being depression, anxiety and behavioural disorders. According to the World Health Organisation [ 1 ], one in six people are of ages 10–19, and within this age group, one in seven experience mental health challenges. Children of this age group are at a critical period of developing healthy habits that are necessary for their mental wellness. Being exposed to difficult circumstances at this tender age can compromise their ability to develop healthy mental wellness.

The first year of life is pivotal in the neurological development of children [ 2 ]. The childhood experiences during this period can have a positive or negative impact in the development of the brain. Children who are raised in nurturing environments of love, care and support can develop healthy attachments, relationships of trust, security and a good self-esteem. Infants who grow up in unconducive environments characterised by abuse and neglect tend to feel unloved, unappreciated and unwanted. Such children may avoid building intimate and social relationships later in life as they find it difficult to trust other people. They develop fear of their environment and view the world as a dangerous place [ 2 ].

Domestic violence is one of the environmental factors that may not be physically directed at children within the family but have a direct impact on them. Children who witness violence at home experience mental, emotional and social challenges that predispose them to mental illness. They are likely to be victims of child abuse and or perpetrators of violence later in their adulthood. The impact of domestic violence on children is likely to manifest in behavioural challenges, low school grades, criminal behaviour and antisocial behaviour [ 3 ]. The World Health Organisation [ 4 ] estimates that 1 billion children of ages 2–17 have experienced violence of one kind or another, most of which is perpetrated within the home environment. It is in this sense that children are often referred to as silent victims of violence and abuse.

Another environmental factor that affects not only the married couple but children as well is marital breakdown. Divorce brings a lot of devastation, grief and traumatic loss for the children of divorced parents. Logistically and practically, divorce results in single parenting. This is still the case even when in cases of shared custody. The parent who lives with the child carries more responsibility in terms of the day-to-day care and support for the child. More often, parents who bear custody of the children are overburdened financially and logistically, while the other parent might resist and contest reasonable financial contribution towards the needs of the children [ 5 ]. The stress of separation between parents can easily be transferred to children, leading to mental health challenges as parents go about creating a new life for themselves, paying less attention to the emotional needs of children. Divorce is, thus, one of the major sources of stress and anxiety in children that can result in mental illness.

Parents have got the responsibility to ensure financial security for their children such as provision of medical care, being able to cater for educational costs, housing, and day-to-day provision for the needs of the family. In most cases, this can be achieved through employment. Parental employment can have both positive and negative effects on parent-child relationships. On the one hand, employment can provide financial stability and a sense of accomplishment that can have a positive impact on the well-being of the family. On the other hand, employment can create stress and time pressures for parents, leading to a strain on parent-child relationships. Parents are likely to bring home the stress of work, which may destabilise the homely environment and further transfer stressful vibes to children.

Growing up in a dysfunctional family has harmful effects that extend to adulthood in children. Children have got no control of the unconducive living conditions created by their parents, caregivers and guardians. Often parents who engage in toxic relationships of violence and abuse are less considerate of the impact of their behaviour on children. They are not aware of the extent of the impact of their actions on children because their aggression is not directed at children, and therefore, they do not think that they are causing emotional harm to children. This unfortunately could not be far from the truth. Negative parenting patterns, such as emotional abuse and neglect, punishment and rejection, create trauma that can result in mental health issue for children.

Some parents come from toxic families themselves where they were exposed to violence, aggression, abuse, neglect, rejection and other negative parenting as children. It becomes difficult for such parents to divorce themselves from their childhood experiences and learn new and positive ways of parenting their own children. Many families are reluctant to accept that they fall in the category of dysfunctional families and thus resist or delay to seek help [ 6 ]. Parents are convinced that they are doing well because they are able to provide financially for their children, by so doing, overlooking the negative effects of the toxic environment in which they are raising children. This circle, if not broken, can be transferred from generation to generation, hurting children up to the edge of mental illness and creating dysfunctional families and communities.

The aim of this chapter is, therefore, to provide information about the relationship between parenting, family dynamics and mental health of children targeting children, parents, families, caregivers and officials who are responsible for proving services to children and families such as social workers, psychologists, and teachers.

2. The impact of growing up in a dysfunctional family

Dysfunctional families have become a huge problem in modern society. While there are no perfect families and people do not choose which family to belong to, the level of dysfunction and lack of coherence in some families are a course for concern. Dysfunctional families are characterised by multiple conflicts, tense relationships, chaos, neglect, abuse, poor communication, lack of empathy and secrecy to an extent that the emotional and physical needs of the family members are not met, especially children. Conflicts are often between parents, parent-child conflict or sibling rivalries. Life in a dysfunctional family is a turbulence of uncertainty and instability as well as an unsafe space for family members. Instead of expressing their concerns and resolving issues in a positive manner, members in some dysfunctional families normalise their situation and get accustomed to condoning unacceptable behaviour such as abuse, victimisation and conflict, and they sweep issue under the carpet. Conflict is an inevitable part of human relationships; however, dysfunctional families model negative ways of managing conflict to children with the biggest problem being lack of effective communication. In dysfunctional families, communication is replaced with shouting, screaming, arguing and silence.

Healthy functioning families, on the other hand, exhibit harmony, love, care and support for each other; the home is the safest environment where they are able to express themselves, and members have a sense of emotional, mental and physical wellness. In healthy functioning families, conflict, disagreements and differences are resolved in a healthy manner that is beneficial to all concerned.

The negative dynamics that are found in dysfunctional families have adverse effects on the growing personality of children and creates a negative viewpoint on life in general; it inflicts pain and leave emotional wounds that are not reversible. This is because the family has got influence on the development of the child and provides a foundation for the growth of the child such as one’s identity, values, norms and morals that are acceptable in society by proving the child with a safe space, love, affection as well as instilling social awareness and confidence [ 7 ]. This means the family can influence the growth and development of the child in a positive or negative way depending on the lifestyle, parenting, and the level of functionality of that family. Children are likely to carry what they have observed and learned during their childhood into adulthood.

In dysfunctional families, mostly both or one parent exhibits unharmonious, parenting style and behaves in an unpredictable manner resulting in the home environment being unstable [ 8 ]. Children as a result are forever on guard because they never know what to expect and when conflict is going to take place. Some parents are emotionally distant towards children, making it hard to create normal family bonds. The impact on children is low self-esteem and the inability to express their feelings in a healthy way and ultimately childhood trauma. Children as a result experience repeated trauma and pain from their parents’ actions, words and attitudes, while parents are generally in denial that they lead a dysfunctional family [ 4 ]. Children grow up with multiple traumas that leave them with permanent emotional and mental scars, sadness and distress. Trauma if not treated may lead to physical and psychological illness [ 9 ].

Children from dysfunctional families may experience stigma by their peers for the situation at home. This increases the risk of becoming withdrawn and isolated within the family and around their friends. Growing up in a dysfunctional family indeed exposes children to emotional trauma that can lead to mental illness.

3. Mental illness of children

Child mental health is the ability to grow psychologically, socially, intellectually and spiritually, reaching emotional and developmental milestones without a struggle [ 10 ]. Children with mental health challenges are at risk of experiencing a delay in age-appropriate development that can affect their normal functioning and the quality of life. Mental health in children is important for their present and future quality of life because childhood experiences have a profound effect on adulthood.

Mental illness in children can be caused by a variety of issues such as stresses relating to domestic violence, being bullied, losing a loved one to death, separation from friends because of moving homes or schools. It can also be caused by separation from parents because of divorce or parents who work long hours away from home as well as child abuse and suffering from a long illness. Mental illness can also be hereditary meaning there is a likelihood that parents can pass the illness to their children. Some of the symptoms in children are, but not limited to, persistent unhappiness and sadness, emotional outbursts and extreme mood swings, difficulties in academic achievement, loss of appetite or overeating, difficulty falling asleep and fear and sudden loss of interest in previously loved activities such as sport [ 11 ].

People exist within the family environment from childhood to adulthood meaning the family plays an essential role in the physical and mental well-being of its members especially during the formative development of children. Children need care that promotes resilience, ability to thrive, modelling appropriate behaviour and coping resources. It is, however, difficult to achieve this when children experience inadequate parental care [ 12 ]. Parents can minimise the risk of child mental illness by improving the conditions of living at home, the environment in which the child functions and general childhood relationships and experiences.

The family, specifically parents, have got the responsibility to raise their children in the manner that encourages positive emotional health and overall mental health and minimises the risk and exposure to anxiety, depression, fear and helplessness both at home and outside the home environment by providing love and positive affirmations. While some families try to raise children by ensuring healthy development towards a bright future, some instill and model unhealthy and unhelpful practices that will negatively impact the child’s life permanently; an example of this is the high percentage of children who are born with foetal alcohol spectrum disorder (FASD). FASD happens when a pregnant woman consumes alcohol, and the baby is exposed to the harsh impact of alcohol before birth. This condition manifests itself in physical learning and behavioural challenges later when the child is born. According to Tomlinson et al. [ 13 ], South Africa has got the highest rate of FASD in the world. Children with FASD are at risk of developing mental illness. FASD unfortunately creates a circle that requires resilience and courage to break.

Modelling negative behaviour to children results in children adopting unhealthy life habits. This can be seen in the prevalence of the adolescent who experience with alcohol in South Africa’s province of Western Cape [ 13 ]. Such children are affected by the behaviour of their parents, the same parents who are supposed to protect them. This is an indication of unstable and unhealthy parenting practices that may ultimately lead to mental health problems in children.

Mentally healthy children, on the other hand, have a positive outlook on life, and they can function optimally emotionally, socially and academically.

4. The impact of divorce on children

Divorce is prevalent in today society across the world. According to the United Nations Organisation [ 14 ], 4.08 per 1000 married persons end in divorce worldwide. In 2020, for example, Maldives recorded the highest divorce rate in the world with 2984 divorces out of a population of 540,544, which translates to 5.52 divorce rate per 1000 married persons. In South Africa alone, 23,710 divorces out of the 129,597 marriages were recorded in 2019, according to Statistics South Africa [ 15 ]. Divorce, like other environmental factors that affect families, has a dire effect on children, and it undermines the parent-child relationship because of the decline in the quality of relationships, especially with the parent who does not bear custody. Children from divorced families often experience a range of emotions and challenges, including feelings of loss, confusion and insecurity. They lose the family structure that they are accustomed to, and they have to adjust to living in two separate homes and spending time away from one parent at a time.

Divorce creates emotional distance between the child and the parent who does not live with the child on a full-time basis especially in instances where divorce is preceded by conflict, tension and domestic violence between parents [ 16 ]. Protracted divorce processes that are characterised by conflict also create emotional distance between children and parents. According to Fagan and Churchill [ 17 ] domestic violence weakens and undermines the parent-child relationship. Children of divorced parents may also feel caught in between because of feelings of conflicting loyalty as though they have to choose between their parents. The distance between parents and children causes emotional strain and irreversible harm, which, if not treated, can result in long-term mental health problems. Children of divorced parents are likely to present with weakened health, psychological trauma and behavioural problems because of insufficient emotional support, affection, care and love from both parents. Children as a result struggle to trust and rely on their parents as they develop a sense of fear for the environment around them. Lack of trust hampers family relations.

On the other hand, parents who bear custody of children are faced with difficulties relating to raising children on their own. Juggling work and single parenting may result in lack of sufficient supervision of children. Single parenting because of divorce makes stress inherent as the parent tries to raise children alone. It reduces household income and makes it difficult for the one parent to maintain the standard of living that the children are accustomed to as well as ensuring the maintenance of the home. These challenges can translate into exposure to risk behaviour for children such as embarking on the use of drugs, criminal behaviour and ultimately falling behind academically. Children in broken families may not receive enough encouragement, support and stimulation, and this can affect their ability to focus on school. Active parental involvement of both parents in the child’s life is important to prevent the overload on one parent. Wajim and Shimfe [ 18 ] opined that children from divorced families have an increased likelihood of presenting with anti-social behaviour because of the lack of presence of both parents to bring the child up in the norms and values of society, a task that is the responsibility of both parents, playing complimentary roles in their children’s lives. Behere et al. [ 19 ] elucidate that divorce is a risk factor for mental health problems especially for children.

Divorce paves a way for negative perceptions against marriage and stable relationships. According to Fagan and Churchill [ 17 ], boy children from divorced families, for example, are likely to engage in countless and short-term sexual relationships with multiple partners, and they also have a high turnover of failed intimate relationships compared to adults who were raised in intact families. Fagan and Churchill further revealed that children who experience strained relations between parents prefer to leave home earlier to get married, cohabit or live on their own because of the lack of peace and harmony in their homes, instead of continuing to witness the commotion between their parents.

5. The impact of domestic violence on children

Domestic violence is recognised globally as a public health problem and a violation of human rights by organisations such as the United Nations [ 20 ] and the World Health Organisation [ 21 ] as well as national and international studies such as [ 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 ]. It is a destructive act of violence and aggression that causes harm physically and mentally as well as neglect and isolation to the family members who are victims. The intention of violence in the family is mostly to wound, intimidate, manipulate, humiliate and gain power over the victim. It affects people globally across the spectrum of race and class, and it is rooted in gender inequality [ 27 , 28 ]. While violence in the family affect both men and women, its prevalence is higher in violence against women and children, perpetrated within the family or by intimate partners [ 29 ]. According to the World Health Organisation [ 30 ], exposure to domestic violence, especially intimate partner violence, increases the risk of mental health problems.

Despite a change in the trend in some countries, violence in the family is often still concealed and not reported because it is regarded as a private matter that does not require external intervention [ 31 ]. This assumption that family violence is a private matter normalises violence behind closed doors, leading to many families suffering in silence. Children who are raised in homes with family violence may not report it as they see it as a norm, meaning they may not receive help for the emotional trauma suffered. Children who are exposed to violence and aggression of one form or another may suffer psychologically and emotionally with the likelihood of using violence to resolve conflict with their peers and siblings. This is because of the lack of role models on positive conflict management. As teenagers, they may be victimised and stigmatised if they press criminal charges against their own family members; as a result, they continue to suffer in silence. This may lead to the use of unhealthy methods of coping such as self-harm, substances abuse and suicide. In adulthood, they are inclined to argue with their peers, shouting and using physical violence instead of communicating effectively, and they may exhibit signs of anxiety and depression [ 32 ].

Domestic violence is detrimental to the children’s mental health as it introduces a stressful home environment with a sense of fear, anger, anxiety, nervousness and depression. The home is supposed to be the safest place for children; however, when violence takes place, children find themselves lost emotionally because they no longer regard their homes as safe environments. Often violence in the family is directed at adults such as wives and girlfriends; however, the emotional impact goes to children who are helpless. Perpetrators of domestic violence fail to appreciate the impact of their actions on children as they believe that they are physically doing nothing wrong to them. A parent cannot claim to love a child whom they continually subject to witnessing violence against the other parent, mostly mothers. When children see their mothers battered, they feel pain, anger and resentment [ 28 ]. This means when violence is perpetrated against one member of the family, the entire family system gets affected, with children being the most affected. Parents who were abused as children may not be able to pay attention to nurturing their children as they may still be battling with their own childhood issues, and this can lead to isolation and neglect of their children.

Children need stable environments with responsive parents who are nurturing and protective to grow and explore without fear of failure or harm. Domestic violence is toxic, and it slowly hurts children emotionally.

6. The impact of working parents on parent: Child relationship

Some parents are not directly involved in conflict, but they are simply too busy chasing careers, business or personal activities such as sport and personal entertainment. Working long hours, taking work home and spending a lot of time on their digital devices lead to physical and emotional absence in the home. As a result, providing inadequate parenting neglects the emotional needs of children and creates emotional distance between themselves and children. Parental employment is an essential tool to obtain economic means and fulfilment of material benefits for the family. Lack of income, on the other hand, can hamper the quality of parenting in terms of providing the day-to-day needs of the child, educational needs and provision of stimulating activities and entertainment.

By spending quality time with children, parents can provide a sense of security and stability, which is essential for their mental health, growth and development. The combination of parental employment and parent-child bond creates the foundation for a healthy functioning environment for the well-being of the child. Lau [ 33 ] emphasises that there is a need for parents to maintain a healthy family-work balance to ensure financial, material provision and quality family bonds and relationships.

Working parents might find it difficult to fulfil the parental role and participate in building family bonds. Juggling work and family responsibilities can also result in emotional distress for a parent, which can lead to parents not being able to spend quality time with children, participate in their schoolwork and provide support for their emotional growth concurrently. Lack of parental support may result in compromised parent-child relationship.

Working long hours away from home renders parents vulnerable to stress because of competing demands of work and family roles. Work overload can result in parents feeling overwhelmed, and this can lead to the deterioration in the mental health of parents. It is easy for parents to bring home stress from work that can affect the parent’s ability to provide emotional support for children; if not managed, it can undermine the atmosphere in the home and transfer to children [ 34 ]. This is because the mental health of a parent has got an impact on the mental health of children. Lengthy hours of work also mean children might have to be placed in alternative care such as aftercare programmes resulting in children spending more time with schoolteachers and aftercare staff members than with their parents. Bishnoi et al. [ 34 ] are of the view that the communication and interaction between parents and children is negatively affected when children spend more time with other people such as caregivers and relatives than with parents. On the other hand, poor-quality day-care services can expose children to physical and emotional harm. A good balance between family and work roles and responsibilities is important for the healthy functioning of the family and development of mental health in children.

7. Conclusions

This chapter provides information about the role families play in the mental health of children and the difficulties faced by children who grow up in dysfunctional families. The family provides an environment for children to grow, develop, observe and learn behavioural traits that will enable them to function in society such as norms, values, morals and socially acceptable behaviour. What children learn and experience have a potential to influence their character and mental health. Children with negative experiences such as divorce, domestic violence, parent-child separation and dysfunctional families are prone to develop mental health challenges.

Divorce exposes children to the difficulties of being raised by a single parent as well as emotional distance. Children from broken families tend to experience trust problems with the perception that marriages and relationships are not safe and intimate partners should not be trusted. Divorce separate children from parents and undermines the parent-child bond, which is important for building and sustaining relationships in the family, as well as social and intimate relationships.

Children are affected by the violence and aggression displayed in families that are riddled by domestic violence. Violence in families is often perpetuated in secret, and as a result, children suffer in silence. Witnessing violence by one parent against the other affects children emotionally and psychologically. When they grow up, such children tend to use violence to resolve conflict and use arguments instead of communication.

The inability of parents to spend quality time with children because of work-related commitments impact the parent-child relationship and cause emotional distance as well. The stress of parents from work if not managed can infiltrate the home environment and lead to tensions in the family. Parental employment is necessary to provide financially for children; however, it is necessary for parents to strike a healthy balance between the two.

The challenges discussed above renders the family system dysfunctional. Dysfunctional families are not able to effectively provide for the emotional, psychological, social and academic needs of their children. Children as such are exposed to neglect, abuse, conflicts and poor communication. This can lead to mental health, behavioural and social challenges in children.

The environment in which children grow up has got an impact on their developing mental health. Families should ensure that factors that contribute to a dysfunctional family are avoided so that children can grow up in nurturing and enabling environments for the development of a healthy mental well-being.

Conflict of interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

- 1. World Health Organisation. Adolescent Mental Health. Switzerland: World Health Organization Library Cataloguing-in Publication; 2021. Available from: Adolescent mental health (who.int )

- 2. Ejaikait VI. Effects of Gender-Based Violence among Students in Masinde Muliro University [Theses]. Kakamega: University of Masinde Muliro; 2014. DOI: 10.13140/RG.2.2.22234.08645

- 3. Holt S, Buckley H, Whelan S. The impact of exposure to domestic violence on children and young people: A review of the literature. Child Abuse and Neglect. 2008; 32 (8):797-810. DOI: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2008.02.004S

- 4. Word Health Organisation. Violence against Women. Geneva: World Health Organization Press; 2021. Available from: Violence against women (who.int )

- 5. Stephen EN, Udisi L. Single parent families and their impact on children: A study of AMASSOMA community in Bayelsa State. European Journal of Research in Social Sciences. 2016; 4 (9):1-24. Available from: full-paper-single-parent-families-and-their-impact-on-children-a-study-of-amassoma-community.pdf (idpublications.org )

- 6. Ubaidi BA. Cost of growing up in dysfunctional family. Journal of Family Medicine and Disease Prevention. 2017; 3 (3):1-6. DOI: 10.23937/2469-5793/1510059

- 7. Heinrich CJ. Parents’ employment and children’s wellbeing. Future of Children. 2014; 24 (1):121-146. Available from: www.futurechildren.org

- 8. Minullina AF. Psychological trauma of children of dysfunctional families. Future Academy. 2018; 45 (1):65-74. DOI: 10.15405/epbs.2018.09.8

- 9. Rodrigues VP, Rodrigues AS, Lira MD, Couto M, Diniz NM. Family relationships in the context of gender-based violence. Text and Context Nursing Journal (Brazil). 2016; 25 (3):2-9. DOI: 10.1590/0104-07072016002530015

- 10. Edwards D, Burnard P. A systematic review of stress and stress management interventions for mental health nurses. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2003; 42 (1):169-200. DOI: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2003.02600.x

- 11. Zubrick SR, Silburn SR, Burton P, Blair E. Mental health disorders in children and young people: Scope, cause and prevention. Journal of Psychiatry. 2000; 34 (1):570-578. DOI: 10.1080/J.1140-1614.2000.00703.X

- 12. Breiner H, Ford M, Gadsden VS. Supporting Parents of Children Ages 0-8. Washington DC: National Academics Press; 2016. DOI: 10.17226/21868

- 13. Tomlinson M, Kleinjies S, Lake L. Child and Adolescent Mental Health. South African Child Gauge. Children’s Institute, University of Cape Town; 2022. Available from: Child Gauge 2021_110822.pdf (uct.ac.za )

- 14. United Nations Organisation. Demographic and Social Statistics on Marriage and Divorce. New York: UNSD-Demographic and Social Statistics; 2022

- 15. Statistics South Africa. Marriages and Divorce in South Africa. Pretoria: South African Government Printing Works; 2021. Available from: www.statssa.gov.za

- 16. Strohschein L. Parenting, divorce and child mental health: Accounting for pre-disruption differences. Journal of Divorce and Remarriage. 2012; 53 (6):489-502. DOI: 10.1080/10502556.2012.682903

- 17. Fagan PF, Churchill A. The Effects of Divorce on Children. Washington DC: Harni Research; 2022. Available from: Marri.frc.org/effects-divorce-children

- 18. Wajim J, Shimfe HG. Single parenting and its effects on the development of children in Nigeria. The International Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities Invention. 2020; 7 (3):5891-5902. DOI: 10.18535/ijsshi/v7i04.02

- 19. Behere AP, Basnet P, Campbell P. Effects of family structure on mental health of children: A preliminary study. Indian Journal of Psycho Medicine. 2017; 39 (4):457-463. DOI: 10.4103/0253-7176.211767

- 20. United Nations Organisation. Handbook for Legislation on Violence Against Women. New York: United Nations Publication; 2009

- 21. World Health Organisation. World Report on Violence and Health. Geneva: World Health Organization Cataloguing-in Publication; 2002. Available from: 9241545615_eng.pdf (who.int )

- 22. Gregory S, Holt S, Barter C, Christofides N, Maremela O, Motjuwadi NM, et al. Public health directives in a pandemic: Paradoxical messages for domestic abuse victims in four countries. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2002; 19 (1):2-15

- 23. Krantz G. Violence against women: Global public health issue. Journal of Epidemic Community Health. 2002; 56 (1):242-243. Available from: v056p00242.pdf (nih.gov )

- 24. Chibber K, Krishnan S. Confronting intimate partner violence: A global health care priority. Mt Sinai Journal of Medicine. 2011; 78 (3):449-457. DOI: 10.1002/msj.20259

- 25. De Wet-Billings N, Godongwana M. Exposure to intimate partner violence and hypertension outcomes among young women in South Africa. International Journal of Hypertension. 2021; 2021 :1-8. Article ID 5519356. DOI: 10.1155/2021/5519356

- 26. McCloskey LA, Boonzair F, Steinbrenner SY, Hunter T. Determinants of intimate partner violence in sub-Saharan Africa: A review of prevention and intervention programs. Partner Abuse. 2016; 7 (3):277-315. DOI: 10.1891/1946-6560.7.3.277

- 27. Kertesz M, Fogden L, Humphreys C. Domestic Violence and the Impact on Children. London: Routledge is Part of the Taylor & Francis Group Publishers; 2021. DOI: 10.4324/9780429331053

- 28. Khemthong O, Chutiphongdech T. Domestic violence, and its impacts on children: A concise review of past literature. Walailak Journal of Social Science. 2021; 14 (6):1-12. Available from: https://so06.tci-thaijo.org/index.php/wjss

- 29. Rada C. Violence against women by male partners and against children within the family: Prevalence, associated factors and intergenerational transmission in Romania: A cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2014; 14 (129):1-15. DOI: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-129

- 30. World Health Organisation. Preventing Intimate Partner Violence Improves Mental Health. Geneva: World Health Organization Cataloguing-in Publication; 2022. Available from: Preventing intimate partner violence improves mental health (who.int )

- 31. Chuemchit M, Chernkwanma S, Rugkua R, Daengthern L, Abdullakaim P, Wieringa S. Prevalence of intimate partner violence in Thailand. Journal of Family Violence. 2018; 33 (5):315-323. DOI: 10.1007/s10896-018-9960-9

- 32. Lloyd M. Domestic violence and education: Examining the impact of domestic violence on young children, children and young people and the potential role of schools. Frontiers in Psychology. 2018; 9 (11):1-11. DOI: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02094

- 33. Lau YK. The impact of fathers’ work and family conflicts on children’s self esteem: The Hong Kong case. Springer. 2010; 95 (1):363-376. DOI: 10.1007/s11205-009-9535-5

- 34. Bishnoi S, Malik P, Yadav P. A review of effects of working mothers on Children’s development. Akinik Publications. 2020; 4 (1):41-55. DOI: 10.22271/ed.book.960

© 2023 The Author(s). Licensee IntechOpen. This chapter is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Continue reading from the same book

Published: 02 November 2023

By Ethelbert P. Dapiton, Enrique G. Baking and Ranie ...

138 downloads

By Mónica De Martino and Maia Krudo

55 downloads

By Hetty Rooth

63 downloads

Shameless Family: Destructive and Dysfunctional Family

This essay about the concept of a “shameless family tree” explores how families known for their defiance of societal norms can reflect broader societal changes and values over time. It discusses the significance of individuals within these families who engaged in behaviors considered scandalous or bold by their contemporaries, such as adventurers or activists. These figures often challenged societal expectations and contributed to social and political movements. The essay also examines the subjective nature of shame and how it varies across different cultures and historical periods. Additionally, it considers the impact of legacy and how the reputations of ancestors can influence the lives and perceptions of descendants. Ultimately, the essay celebrates the indomitable spirit of those who lived unapologetically and the enduring influence of their actions on society.

How it works

In exploring the intriguing concept of a “shameless family tree,” we venture into an examination not just of genealogy but also of the audacious behaviors and bold personalities that can characterize familial lineages. This narrative delves into the rich tapestry of a family’s history, where the lack of shame—often perceived as a negative trait—may instead be viewed as a marker of resilience and individuality.

The term “shameless” typically carries a connotation of impropriety or boldness, yet when applied to the lineage of a family, it takes on a deeper significance.

It suggests a lineage marked not only by conventional achievements but also by unconventional choices and actions that defy societal norms. Families known for their “shamelessness” might be those whose members have consistently broken barriers, challenged societal expectations, or lived lives steeped in controversy and fascination.

One might consider, for example, a family where each generation has harbored artists, activists, or adventurers—individuals who, in their respective eras, pushed against the confines of societal norms. These are the families whose stories are often not whispered about but spoken aloud, with a mixture of both disdain and admiration. Their narratives are populated with actions deemed scandalous at the time—perhaps due to unconventional lifestyles, bold professional choices, or controversial contributions to social and political debates.

Take, for instance, a family tree that includes a 19th-century adventuress who traveled the world alone, a rarity and a scandal at the time; or a mid-20th-century activist who played a pivotal role in civil rights movements, challenging the status quo and altering societal structures. These figures might have been labeled “shameless” in their times for stepping outside expected roles and behaviors. Yet, with the passage of time, society often comes to view such individuals through a lens of respect and admiration for their courage and foresight.

The “shameless” label also prompts a discussion on the subjective nature of shame itself. Shame is culturally dependent—a behavior considered shameless in one culture or era might be deemed brave or revolutionary in another. Thus, the shameless family tree does not just chronicle a history of nonconformity; it also reflects the evolving morals and norms of society. It holds a mirror to the ways in which cultural perceptions of right and wrong change over time, influenced by shifts in politics, societal values, and collective consciousness.

Moreover, the study of a shameless family tree serves as a poignant reminder of the power of legacy. It shows how the deeds and reputations of ancestors can influence perceptions of their descendants, often setting expectations or casting long shadows over future generations. It raises questions about the extent to which individuals are shaped by their familial pasts and how they navigate the legacy of being part of a lineage that is marked by shamelessness.

In conclusion, examining a shameless family tree offers more than just a recounting of provocative stories from the past. It invites reflection on the nature of legacy, the shifting sands of societal judgment, and the enduring impact of those who dared to live boldly. This exploration not only enriches our understanding of human behavior and societal evolution but also celebrates the indomitable spirit of those who, by choice or by nature, lived unapologetically and without shame. Through their stories, we are prompted to reconsider our own ideas of conformity, courage, and legacy.

Remember, this essay is a starting point for inspiration and further research. For more personalized assistance and to ensure your essay meets all academic standards, consider reaching out to professionals at [EduBirdie](https://edubirdie.com/?utm_source=chatgpt&utm_medium=answer&utm_campaign=essayhelper).

Cite this page

Shameless Family: Destructive And Dysfunctional Family. (2024, Apr 29). Retrieved from https://papersowl.com/examples/shameless-family-destructive-and-dysfunctional-family/

"Shameless Family: Destructive And Dysfunctional Family." PapersOwl.com , 29 Apr 2024, https://papersowl.com/examples/shameless-family-destructive-and-dysfunctional-family/

PapersOwl.com. (2024). Shameless Family: Destructive And Dysfunctional Family . [Online]. Available at: https://papersowl.com/examples/shameless-family-destructive-and-dysfunctional-family/ [Accessed: 20 May. 2024]

"Shameless Family: Destructive And Dysfunctional Family." PapersOwl.com, Apr 29, 2024. Accessed May 20, 2024. https://papersowl.com/examples/shameless-family-destructive-and-dysfunctional-family/

"Shameless Family: Destructive And Dysfunctional Family," PapersOwl.com , 29-Apr-2024. [Online]. Available: https://papersowl.com/examples/shameless-family-destructive-and-dysfunctional-family/. [Accessed: 20-May-2024]

PapersOwl.com. (2024). Shameless Family: Destructive And Dysfunctional Family . [Online]. Available at: https://papersowl.com/examples/shameless-family-destructive-and-dysfunctional-family/ [Accessed: 20-May-2024]

Don't let plagiarism ruin your grade

Hire a writer to get a unique paper crafted to your needs.

Our writers will help you fix any mistakes and get an A+!

Please check your inbox.

You can order an original essay written according to your instructions.

Trusted by over 1 million students worldwide

1. Tell Us Your Requirements

2. Pick your perfect writer

3. Get Your Paper and Pay

Hi! I'm Amy, your personal assistant!

Don't know where to start? Give me your paper requirements and I connect you to an academic expert.

short deadlines

100% Plagiarism-Free

Certified writers

Advertisement

Exploring the family origins of adolescent dysfunctional separation–individuation

- Original Paper

- Published: 28 October 2019

- Volume 29 , pages 382–391, ( 2020 )

Cite this article

- Shiyuan Xiang 1 ,

- Yan Liu ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-3188-8287 1 ,

- Yitian Lu 1 ,

- Lu Bai 1 &

- Shenghan Xu 1

1111 Accesses

3 Citations

Explore all metrics

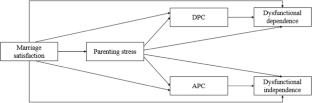

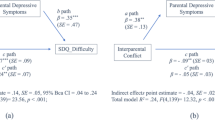

This study aimed to explore family origins of adolescent dysfunctional separation-individuation. We tested the fit of a theoretical model in which mothers’ parenting stress and adolescents’ perceived maternal psychological control were specified as mediators between mothers’ marital satisfaction and adolescent dysfunctional separation–individuation.

Participants were 276 adolescents (aged 12–15 years old) and their mothers. Adolescents completed measures of perceived maternal psychological control and dysfunctional separation–individuation, and mothers completed measures of marital satisfaction and parenting stress.

The association between mothers’ marital satisfaction and adolescents’ dysfunctional dependence was both direct and serially mediated through mothers’ parenting stress and adolescents’ perceived maternal dependency-oriented psychological control ( β = −0.02, p < 0.05, 95% CI = [−0.04, −0.002]). Parenting stress was associated with dysfunctional dependence through perceived dependency-oriented psychological control ( β = 0.06, p < 0.05, 95% CI = [0.01, 0.10]) while being associated with dysfunctional independence through perceived achievement-oriented psychological control ( β = 0.05, p < 0.05, 95% CI = [0.01, 0.10]). Parenting stress also served as the mediator in the association between marital satisfaction and perceived dependency-oriented psychological control ( β = −0.06, p < 0.05, 95% CI = [−0.11, −0.01]), and in the association between marital satisfaction and perceived achievement-oriented psychological control ( β = −0.06, p < 0.05, 95% CI = [−0.11, −0.001]).

Conclusions

The current study extended past findings by identifying mothers’ marital satisfaction as a contributor to adolescent dysfunctional separation–individuation, and parenting stress and adolescents’ perceived maternal psychological control as mediating mechanisms.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Exploring the Link between Interparental Conflict and Adolescents’ Adjustment in Divorced and Intact Iranian Families

Exploring psychosocial adjustment profiles in Chinese adolescents from divorced families: The interplay of parental attachment and adolescent’s gender

Paternal Incarceration, Family Relationships, and Adolescents’ Internalizing and Externalizing Problem Behaviors

Data availability.

We have joined the Peer Reviewers’ Openness Initiative and made our study data open and transparent. Please see https://doi.org/10.17632/dp4gjf4rht.1 .

Abidin, R. (1992). The determinants of parenting behavior. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology , 21 , 407–412.

Article Google Scholar

Bao, X. H., & Lam, S. F. (2008). Who makes the choice? Rethinking the role of autonomy and relatedness in Chinese children’s motivation. Child Development , 79 , 269–283.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Barber, B. K. (1996). Parental psychological control: revisiting a neglected construct. Child Development , 67 , 3296–3319.

Belsky, J. (1984). The determinants of parenting: a process model. Child development , 55 , 83–96.

Berry, J. O., & Jones, W. H. (1995). The parental stress scale: initial psychometric evidence. Journal of Social & Personal Relationships , 12 , 463–472.

Blos, P. (1967). The second individuation process of adolescence. Psychoanalytic Study of the Child , 22 , 162–186.

Chen, L., Wu, X., & Liu, C. (2014). The relationship between marital satisfaction and father involvement: the mediation effect of coparenting. Psychological Development & Education , 3 , 268–276.

Google Scholar

Cheung, C. S., & Pomerantz, E. M. (2011). Parents’ involvement in children’s learning in the United States and China: implications for children’s academic and emotional adjustment. Child Development , 82 , 932–950.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Coln, K. L., Jordan, S. S., & Mercer, S. H. (2013). A unified model exploring parenting practices as mediators of marital conflict and children’s adjustment. Child Psychiatry & Human Development , 44 , 419–29.

Cox, M. J., & Paley, B. (1997). Families as systems. Annual Review of Psychology , 48 , 243–267.

Deater-Deckard, K. (2004). Parenting stress . New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). The” what” and” why” of goal pursuits: human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry , 11 , 227–268.

Delhaye, M., Kempenaers, C., Burton, J., Linkowski, P., Stroobants, R., & Goossens, L. (2012). Attachment, parenting, and separation–individuation in adolescence: a comparison of hospitalized adolescents, institutionalized delinquents, and controls. Journal of Genetic Psychology , 173 , 119–141.

Downing, H. M., & Nauta, M. M. (2010). Separation-individuation, exploration, and identity diffusion as mediators of the relationship between attachment and career indecision. Journal of Career Development , 36 , 207–227.

Flowers, B. J., & Olson, D. H. (1993). ENRICH marital satisfaction scale. Journal of Family Psychology , 7 , 176–185.

Grolnick, W. S., Price, C. E., Beiswenger, K. L., & Sauck, C. C. (2007). Evaluative pressure in mothers: effects of situation, maternal, and child characteristics on autonomy supportive versus controlling behavior. Developmental Psychology , 43 , 991–1002.

Guisinger, S., & Blatt, S. J. (1994). Individuality and relatedness: evolution of a fundamental dialectic. American Psychologist , 49 , 104–111.

Haws, W. A., & Mallinckrodt, B. (1998). Separation-individuation from family of origin and marital adjustment of recently married couples. American Journal of Family Therapy , 26 , 293–306.

Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling , 6 , 1–55.

Huth-Bocks, A. C., & Hughes, H. M. (2008). Parenting stress, parenting behavior, and children’s adjustment in families experiencing intimate partner violence. Journal of Family Violence , 23 , 243–251.

Jeong, Y., & Chun, Y. (2010). The pathways from parents’ marital quality to adolescents’ school adjustment in South Korea. Journal of Family Issues , 31 , 1604–1621.

Jiang, L. C., Yang, I. M., & Wang, C. J. (2016). Self-disclosure to parents in emerging adulthood: examining the roles of perceived parental responsiveness and separation-individuation. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships , 34 , 425–445.

Kins, E., Beyers, W., & Soenens, B. (2013). When the separation-individuation process goes awry: distinguishing between dysfunctional dependence and dysfunctional independence. International Journal of Behavioral Development , 37 , 1–12.

Kins, E., Soenens, B., & Beyers, W. (2012). Parental psychological control and dysfunctional separation–individuation: a tale of two different dynamics. Journal of Adolescence , 35 , 1099–1109.

Kruse, J., & Walper, S. (2008). Types of individuation in relation to parents: predictors and outcomes. International Journal of Behavioral Development , 32 , 390–400.

Levine, J. B., Green, C. J., & Millon, T. (1986). The separation–individuation test of adolescence. Journal of Personality Assessment , 50 , 123–137.

Lin, X., Zhang, Y., Chi, P., Ding, W., Heath, M. A., Fang, X., & Xu, S. (2017). The mutual effect of marital quality and parenting stress on child and parent depressive symptoms in families of children with oppositional defiant disorder. Frontiers in Psychology , 8 , 1810–1821.

Liu, Y., Deng, H., Zhang, G., Liang, Z., & Lu, Z. (2015). Association between parenting stress and child behavioral problems: the mediation effect of parenting styles. Psychological Development & Education , 31 , 219–326.

Louie, A. D., Cromer, L. D., & Berry, J. O. (2017). Assessing parenting stress: review of the use and interpretation of the Parental Stress Scale. Family Journal , 25 , 359–367.

Lynch, M., & Cicchetti, D. (2002). Links between community violence and the family system: evidence from children’s feelings of relatedness and perceptions of parent behavior. Family Process , 41 , 519–532.

Mabbe, E., Soenens, B., Vansteenkiste, M., van der Kaap-Deeder, J., & Mouratidis, A. (2018). Day-to-day variation in autonomy-supportive and psychologically controlling parenting: the role of parents’ daily experiences of need satisfaction and need frustration. Parenting-Science and Practice , 18 , 86–109.

Mahler, M. S., Pine, F., & Bergman, A. (1975). The psychological birth of the human infant . New York: Basic Books.

Mattanah, J. F., Hancock, G. R., & Brand, B. L. (2004). Parental attachment, separation-individuation, and college student adjustment: a structural equation analysis of mediational effects. Journal of Counseling Psychology , 51 , 213–225.

Mayseless, O., & Scharf, M. (2009). Too close for comfort: Inadequate boundaries with parents and individuation in late adolescent girls. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry , 79 , 191–202.

Osborne, L. A., & Reed, P. (2010). Stress and self-perceived parenting behaviors of parents of children with autistic spectrum conditions. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders , 4 , 405–414.

Oudekerk, B. A., Allen, J. P., Hessel, E. T., & Molloy, L. E. (2014). The cascading development of autonomy and relatedness from adolescence to adulthood. Child Development , 86 , 472–485.

Preacher, K. J., Rucker, D. D., & Hayes, A. F. (2007). Addressing moderated mediation hypotheses: theory, methods, and prescriptions. Multivariate Behavioral Research , 42 , 185–227.

Qin, L., Pomerantz, E. M., & Wang, Q. (2009). Are gains in decision-making autonomy during early adolescence beneficial for emotional functioning? The case of the United States and China. Child Development , 80 , 1705–1721.

Robinson, M., & Neece, C. L. (2015). Marital satisfaction, parental stress, and child behavior problems among parents of young children with developmental delays. Journal of Mental Health Research in Intellectual Disabilities , 8 , 23–46.

Rolan, E. P., Schmitt, S. A., Purpura, D. J., & Nichols, D. L. (2018). Sibling presence, executive function, and the role of parenting. Infant & Child Development , 27 , 2091.

Scharf, M., & Goldner, L. (2018). “If you really love me, you will do/be…”: Parental psychological control and its implications for children’s adjustment. Developmental Review , 49 , 16–30.

Schoppe-Sullivan, S., Schermerhorn, A., & Cummings, E. M. (2007). Marital conflict and children’s adjustment: evaluation of the parenting process model. Journal of Marriage & Family , 69 , 1118–1134.

Schramm, D. G., & Adler-Baeder, F. (2012). Marital quality for men and women in stepfamilies: examining the role of economic pressure, common stressors, and stepfamily-specific stressors. Journal of Family Issues , 33 , 1373–1397.

Sheldon, K. M., & Gunz, A. (2009). Psychological needs as basic motives, not just experiential requirements. Journal of Personality , 77 , 1467–1492.

Shu, Z., Qiong, H., Li, X., Zhang, J., Zhang, Y., & Fang, X. (2016). Effect of maternal stress on preschoolers’ creative personality: the mediating role of mothers’ parenting styles. Psychological Development & Education , 32 , 276–284.

Soenens, B., Vansteenkiste, M., & Luyten, P. (2010). Toward a domain-specific approach to the study of parental psychological control: distinguishing between dependency-oriented and achievement-oriented psychological control. Journal of Personality , 78 , 217–256.

Steeger, C. M., & Gondoli, D. M. (2013). Mother–adolescent conflict as a mediator between adolescent problem behaviors and maternal psychological control. Developmental Psychology , 49 , 804–814.

Stey, P. C., Hill, P. L., & Lapsley, D. (2014). Factor structure and psychometric properties of a brief measure of dysfunctional individuation. Assessment , 21 , 452–462.

van der Kaap-Deeder, J., Vansteenkiste, M., Soenens, B., Loeys, T., Mabbe, E., & Gargurevich, R. (2015). Autonomy-supportive parenting and autonomy-supportive sibling interactions: the role of mothers’ and siblings’ psychological need satisfaction. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin , 41 , 1590–1604.

Wong, W. C. W., Chen, W. Q., Goggins, W. B., Tang, C. S., & Leung, P. W. (2009). Individual, familial and community determinants of child physical abuse among high-school students in China. Social Science and Medicine , 68 , 1819–1825.

Xiang, S., & Liu, Y. (2018). Understanding the joint effects of perceived parental psychological control and insecure attachment styles: a differentiated approach to adolescent autonomy. Personality and Individual Differences , 126 , 12–18.

Xing, S., Gao, X., Song, X., Archer, M., Zhao, D., Zhang, M., Ding, B., & Liu, X. (2017). Chinese preschool children’s socioemotional development: the effects of maternal and paternal psychological control. Frontiers in Psychology , 8 , 1818.

Download references

Author Contributions

SXi: designed and carried out experiments, analyzed experimental results, created database, conducted data analyses, wrote the paper. YLi: collaborated with the design, writing and data analysis of the study. YLu: collaborated with the design, carried out experiments, assisted with the creation of the database. LB and SXu: assisted with literature review, carried out experiments, assisted with the creation of the database.

This work was supported by the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (2012WYB16) and the MOE Project of Key Research Institutes of Humanities and Social Science at Universities (16JJD880007).

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Institute of Developmental Psychology, School of Psychology, Beijing Normal University, Beijing, China

Shiyuan Xiang, Yan Liu, Yitian Lu, Lu Bai & Shenghan Xu

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Yan Liu .

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethics Approval

All participants were treated according to APA ethical standards, and this study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the School of Psychology, Beijing Normal University.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was received from every adolescent’s mother included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Xiang, S., Liu, Y., Lu, Y. et al. Exploring the family origins of adolescent dysfunctional separation–individuation. J Child Fam Stud 29 , 382–391 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-019-01644-w

Download citation

Published : 28 October 2019

Issue Date : February 2020

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-019-01644-w

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Dysfunctional separation–individuation

- Marital satisfaction

- Parenting stress

- Achievement-oriented psychological control

- Dependency-oriented psychological control

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Innov Aging

Family Relationships and Well-Being

Patricia a thomas.

1 Department of Sociology and Center on Aging and the Life Course, Purdue University, West Lafayette, Indiana

2 Department of Sociology, Michigan State University, East Lansing

Debra Umberson

3 Department of Sociology and Population Research Center, University of Texas at Austin

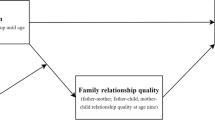

Family relationships are enduring and consequential for well-being across the life course. We discuss several types of family relationships—marital, intergenerational, and sibling ties—that have an important influence on well-being. We highlight the quality of family relationships as well as diversity of family relationships in explaining their impact on well-being across the adult life course. We discuss directions for future research, such as better understanding the complexities of these relationships with greater attention to diverse family structures, unexpected benefits of relationship strain, and unique intersections of social statuses.

Translational Significance

It is important for future research and health promotion policies to take into account complexities in family relationships, paying attention to family context, diversity of family structures, relationship quality, and intersections of social statuses in an aging society to provide resources to families to reduce caregiving burdens and benefit health and well-being.

For better and for worse, family relationships play a central role in shaping an individual’s well-being across the life course ( Merz, Consedine, Schulze, & Schuengel, 2009 ). An aging population and concomitant age-related disease underlies an emergent need to better understand factors that contribute to health and well-being among the increasing numbers of older adults in the United States. Family relationships may become even more important to well-being as individuals age, needs for caregiving increase, and social ties in other domains such as the workplace become less central in their lives ( Milkie, Bierman, & Schieman, 2008 ). In this review, we consider key family relationships in adulthood—marital, parent–child, grandparent, and sibling relationships—and their impact on well-being across the adult life course.

We begin with an overview of theoretical explanations that point to the primary pathways and mechanisms through which family relationships influence well-being, and then we describe how each type of family relationship is associated with well-being, and how these patterns unfold over the adult life course. In this article, we use a broad definition of well-being, including multiple dimensions such as general happiness, life satisfaction, and good mental and physical health, to reflect the breadth of this concept’s use in the literature. We explore important directions for future research, emphasizing the need for research that takes into account the complexity of relationships, diverse family structures, and intersections of structural locations.

Pathways Linking Family Relationships to Well-Being

A life course perspective draws attention to the importance of linked lives, or interdependence within relationships, across the life course ( Elder, Johnson, & Crosnoe, 2003 ). Family members are linked in important ways through each stage of life, and these relationships are an important source of social connection and social influence for individuals throughout their lives ( Umberson, Crosnoe, & Reczek, 2010 ). Substantial evidence consistently shows that social relationships can profoundly influence well-being across the life course ( Umberson & Montez, 2010 ). Family connections can provide a greater sense of meaning and purpose as well as social and tangible resources that benefit well-being ( Hartwell & Benson, 2007 ; Kawachi & Berkman, 2001 ).

The quality of family relationships, including social support (e.g., providing love, advice, and care) and strain (e.g., arguments, being critical, making too many demands), can influence well-being through psychosocial, behavioral, and physiological pathways. Stressors and social support are core components of stress process theory ( Pearlin, 1999 ), which argues that stress can undermine mental health while social support may serve as a protective resource. Prior studies clearly show that stress undermines health and well-being ( Thoits, 2010 ), and strains in relationships with family members are an especially salient type of stress. Social support may provide a resource for coping that dulls the detrimental impact of stressors on well-being ( Thoits, 2010 ), and support may also promote well-being through increased self-esteem, which involves more positive views of oneself ( Fukukawa et al., 2000 ). Those receiving support from their family members may feel a greater sense of self-worth, and this enhanced self-esteem may be a psychological resource, encouraging optimism, positive affect, and better mental health ( Symister & Friend, 2003 ). Family members may also regulate each other’s behaviors (i.e., social control) and provide information and encouragement to behave in healthier ways and to more effectively utilize health care services ( Cohen, 2004 ; Reczek, Thomeer, Lodge, Umberson, & Underhill, 2014 ), but stress in relationships may also lead to health-compromising behaviors as coping mechanisms to deal with stress ( Ng & Jeffery, 2003 ). The stress of relationship strain can result in physiological processes that impair immune function, affect the cardiovascular system, and increase risk for depression ( Graham, Christian, & Kiecolt-Glaser, 2006 ; Kiecolt-Glaser & Newton, 2001 ), whereas positive relationships are associated with lower allostatic load (i.e., “wear and tear” on the body accumulating from stress) ( Seeman, Singer, Ryff, Love, & Levy-Storms, 2002 ). Clearly, the quality of family relationships can have considerable consequences for well-being.

Marital Relationships

A life course perspective has posited marital relationships as one of the most important relationships that define life context and in turn affect individuals’ well-being throughout adulthood ( Umberson & Montez, 2010 ). Being married, especially happily married, is associated with better mental and physical health ( Carr & Springer, 2010 ; Umberson, Williams, & Thomeer, 2013 ), and the strength of the marital effect on health is comparable to that of other traditional risk factors such as smoking and obesity ( Sbarra, 2009 ). Although some studies emphasize the possibility of selection effects, suggesting that individuals in better health are more likely to be married ( Lipowicz, 2014 ), most researchers emphasize two theoretical models to explain why marital relationships shape well-being: the marital resource model and the stress model ( Waite & Gallager, 2000 ; Williams & Umberson, 2004 ). The marital resource model suggests that marriage promotes well-being through increased access to economic, social, and health-promoting resources ( Rendall, Weden, Favreault, & Waldron, 2011 ; Umberson et al., 2013 ). The stress model suggests that negative aspects of marital relationships such as marital strain and marital dissolutions create stress and undermine well-being ( Williams & Umberson, 2004 ), whereas positive aspects of marital relationships may prompt social support, enhance self-esteem, and promote healthier behaviors in general and in coping with stress ( Reczek, Thomeer, et al., 2014 ; Symister & Friend, 2003 ; Waite & Gallager, 2000 ). Marital relationships also tend to become more salient with advancing age, as other social relationships such as those with family members, friends, and neighbors are often lost due to geographic relocation and death in the later part of the life course ( Liu & Waite, 2014 ).

Married people, on average, enjoy better mental health, physical health, and longer life expectancy than divorced/separated, widowed, and never-married people ( Hughes & Waite, 2009 ; Simon, 2002 ), although the health gap between the married and never married has decreased in the past few decades ( Liu & Umberson, 2008 ). Moreover, marital links to well-being depend on the quality of the relationship; those in distressed marriages are more likely to report depressive symptoms and poorer health than those in happy marriages ( Donoho, Crimmins, & Seeman, 2013 ; Liu & Waite, 2014 ; Umberson, Williams, Powers, Liu, & Needham, 2006 ), whereas a happy marriage may buffer the effects of stress via greater access to emotional support ( Williams, 2003 ). A number of studies suggest that the negative aspects of close relationships have a stronger impact on well-being than the positive aspects of relationships (e.g., Rook, 2014 ), and past research shows that the impact of marital strain on health increases with advancing age ( Liu & Waite, 2014 ; Umberson et al., 2006 ).

Prior studies suggest that marital transitions, either into or out of marriage, shape life context and affect well-being ( Williams & Umberson, 2004 ). National longitudinal studies provide evidence that past experiences of divorce and widowhood are associated with increased risk of heart disease in later life especially among women, irrespective of current marital status ( Zhang & Hayward, 2006 ), and longer duration of divorce or widowhood is associated with a greater number of chronic conditions and mobility limitations ( Hughes & Waite, 2009 ; Lorenz, Wickrama, Conger, & Elder, 2006 ) but only short-term declines in mental health ( Lee & Demaris, 2007 ). On the other hand, entry into marriages, especially first marriages, improves psychological well-being and decreases depression ( Frech & Williams, 2007 ; Musick & Bumpass, 2012 ), although the benefits of remarriage may not be as large as those that accompany a first marriage ( Hughes & Waite, 2009 ). Taken together, these studies show the importance of understanding the lifelong cumulative impact of marital status and marital transitions.

Gender Differences

Gender is a central focus of research on marital relationships and well-being and an important determinant of life course experiences ( Bernard, 1972 ; Liu & Waite, 2014 ; Zhang & Hayward, 2006 ). A long-observed pattern is that men receive more physical health benefits from marriage than women, and women are more psychologically and physiologically vulnerable to marital stress than men ( Kiecolt-Glaser & Newton, 2001 ; Revenson et al., 2016 ; Simon, 2002 ; Williams, 2004 ). Women tend to receive more financial benefits from their typically higher-earning male spouse than do men, but men generally receive more health promotion benefits such as emotional support and regulation of health behaviors from marriage than do women ( Liu & Umberson, 2008 ; Liu & Waite, 2014 ). This is because within a traditional marriage, women tend to take more responsibility for maintaining social connections to family and friends, and are more likely to provide emotional support to their husband, whereas men are more likely to receive emotional support and enjoy the benefit of expanded social networks—all factors that may promote husbands’ health and well-being ( Revenson et al., 2016 ).

However, there is mixed evidence regarding whether men’s or women’s well-being is more affected by marriage. On the one hand, a number of studies have documented that marital status differences in both mental and physical health are greater for men than women ( Liu & Umberson, 2008 ; Sbarra, 2009 ). For example, Williams and Umberson (2004) found that men’s health improves more than women’s from entering marriage. On the other hand, a number of studies reveal stronger effects of marital strain on women’s health than men’s including more depressive symptoms, increases in cardiovascular health risk, and changes in hormones ( Kiecolt-Glaser & Newton, 2001 ; Liu & Waite, 2014 ; Liu, Waite, & Shen, 2016 ). Yet, other studies found no gender differences in marriage and health links (e.g., Umberson et al., 2006 ). The mixed evidence regarding gender differences in the impact of marital relationships on well-being may be attributed to different study samples (e.g., with different age groups) and variations in measurements and methodologies. More research based on representative longitudinal samples is clearly warranted to contribute to this line of investigation.

Race-Ethnicity and SES Heterogeneity

Family scholars argue that marriage has different meanings and dynamics across socioeconomic status (SES) and racial-ethnic groups due to varying social, economic, historical, and cultural contexts. Therefore, marriage may be associated with well-being in different ways across these groups. For example, women who are black or lower SES may be less likely than their white, higher SES counterparts to increase their financial capital from relationship unions because eligible men in their social networks are more socioeconomically challenged ( Edin & Kefalas, 2005 ). Some studies also find that marital quality is lower among low SES and black couples than white couples with higher SES ( Broman, 2005 ). This may occur because the former groups face more stress in their daily lives throughout the life course and these higher levels of stress undermine marital quality ( Umberson, Williams, Thomas, Liu, & Thomeer, 2014 ). Other studies, however, suggest stronger effects of marriage on the well-being of black adults than white adults. For example, black older adults seem to benefit more from marriage than older whites in terms of chronic conditions and disability ( Pienta, Hayward, & Jenkins, 2000 ).

Directions for Future Research

The rapid aging of the U.S. population along with significant changes in marriage and families indicate that a growing number of older adults enter late life with both complex marital histories and great heterogeneity in their relationships. While most research to date focuses on different-sex marriages, a growing body of research has started to examine whether the marital advantage in health and well-being is extended to same-sex couples, which represents a growing segment of relationship types among older couples ( Denney, Gorman, & Barrera, 2013 ; Goldsen et al., 2017 ; Liu, Reczek, & Brown, 2013 ; Reczek, Liu, & Spiker, 2014 ). Evidence shows that same-sex cohabiting couples report worse health than different-sex married couples ( Denney et al., 2013 ; Liu et al., 2013 ), but same-sex married couples are often not significantly different from or are even better off than different-sex married couples in other outcomes such as alcohol use ( Reczek, Liu, et al., 2014 ) and care from their partner during periods of illness ( Umberson, Thomeer, Reczek, & Donnelly, 2016 ). These results suggest that marriage may promote the well-being of same-sex couples, perhaps even more so than for different-sex couples ( Umberson et al., 2016 ). Including same-sex couples in future work on marriage and well-being will garner unique insights into gender differences in marital dynamics that have long been taken for granted based on studies of different-sex couples ( Umberson, Thomeer, Kroeger, Lodge, & Xu, 2015 ). Moreover, future work on same-sex and different-sex couples should take into account the intersection of other statuses such as race-ethnicity and SES to better understand the impact of marital relationships on well-being.

Another avenue for future research involves investigating complexities of marital strain effects on well-being. Some recent studies among older adults suggest that relationship strain may actually benefit certain dimensions of well-being. These studies suggest that strain with a spouse may be protective for certain health outcomes including cognitive decline ( Xu, Thomas, & Umberson, 2016 ) and diabetes control ( Liu et al., 2016 ), while support may not be, especially for men ( Carr, Cornman, & Freedman, 2016 ). Explanations for these unexpected findings among older adults are not fully understood. Family and health scholars suggest that spouses may prod their significant others to engage in more health-promoting behaviors ( Umberson, Crosnoe, et al., 2010 ). These attempts may be a source of friction, creating strain in the relationship; however, this dynamic may still contribute to better health outcomes for older adults. Future research should explore the processes by which strain may have a positive influence on health and well-being, perhaps differently by gender.

Intergenerational Relationships