April Theses

Vladimir lenin, the tasks of the proletariat in the present revolution. april 17, 1917.

Original Source: Pravda, 20 April 1917.

I arrived in Petrograd only on the night of April 16, and could therefore, of course, deliver a report at the meeting on April 17, on the tasks of the revolutionary proletariat only upon my own responsibility, and with the reservations as to insufficient preparation.

The only thing I could do to facilitate matters for myself and for honest opponents was to prepare written theses. I read them, and gave the text to Comrade Tseretelli. I read them very slowly, twice: first at the meeting of Bolsheviks and then at a meeting of Bolsheviks and Mensheviks.

I publish these personal theses with only the briefest explanatory comments, which were developed in far greater detail in the report.

1. In our attitude towards the war, which also under the new government of L’vov and Co. unquestionably remains on Russia’s part a predatory imperialist war owing to the capitalist nature of that government, not the slightest concession must be made to “revolutionary defensism.”

The class conscious proletariat could consent to a revolutionary war, which would really justify revolutionary defensism, only on condition: (a) that the power of government pass to the proletariat and the poor sections of the peasantry bordering on the proletariat; (b) that all annexations be renounced in deed and not only in word; (c) that a complete and real break be made with all capitalist interests.

In view of the undoubted honesty of the broad strata of the mass believers in revolutionary defensism, who accept the war as a necessity only and not as a means of conquest, in view of the fact that they are being deceived by the bourgeoisie, it is necessary very thoroughly, persistently and patiently to explain their error to them, to explain the inseparable connection between capital and the imperialist war, and to prove that it is impossible to end the war by a truly democratic, non-coercive peace without the overthrow of capital.

The widespread propaganda of this view among the army on active service must be organized…

2. The specific feature of the present situation in Russia is that it represents a transition from the first stage of the revolution – which, owing to the insufficient class consciousness and organization of the proletariat, placed power into the hands of the bourgeoisie – to the second stage, which must place power into the hands of the proletariat and the poor strata of the peasantry.

This transition is characterized, on the one hand, by a maximum of freedom (Russia is now the freest of the belligerent countries in the world); on the other, by the absence of violence in relation to the masses, and, finally, by the unreasoning confidence of the masses in the government of capitalists, the worst enemies of peace and socialism.

This specific situation demands of us the ability to adapt ourselves to the specific requirements of Party work among unprecedented large masses of proletarians who have just awakened to political life.

3. No support must be given to the Provisional Government; the utter falsity of all its promises must be explained, particularly those relating to the renunciation of annexations. Exposure, and not the unpardonable, illusion- breeding “demand” that this government, a government of capitalists, should cease to be an imperialist government.

4. The fact must be recognized that in most of the Soviets of Workers’ Deputies our Party is in a minority, and so far in a small minority, as against a bloc of all the petty-bourgeois opportunist elements, who have yielded to the influence of the bourgeoisie and convey its influence to the proletariat …

It must be explained to the masses that the Soviet of Workers’ Deputies is the only possible form of revolutionary government, and that therefore our task is, as long as this government yields to the influence of the bourgeoisie, to present a patient, systematic and persistent explanation of the errors of their (the non-Bolshevik socialists) tactics, an explanation especially adapted to the practical needs of the masses.

As long as we are in the minority we carry on the work of criticizing and explaining errors and at the same time advocate the necessity of transferring the entire power of state to the Soviets of Workers’ Deputies, so that the masses may by experience overcome their mistakes.

5. Not a parliamentary republic — to return to a parliamentary republic from the Soviets of Workers’ Deputies would be a retrograde step — but a republic of Soviets of Workers’, Agricultural Laborers’ and Peasants’ Deputies throughout the country, from top to bottom.

Abolition of the police, the Army and the bureaucracy.

The salaries of all officials, who are to be elected and subject to recall at any time, not to exceed the average wage of a competent worker.

6. in the agrarian program the emphasis must be laid on the Soviets of Agricultural Laborers’ Deputies.

Confiscation of all landed estates.

Nationalization of all lands in the country, the disposal of the land to be put in charge of the local Soviets of Agricultural Laborers’ and Peasants’ Deputies. The organization of separate Soviets of Deputies of Poor Peasants. The creation of model farms on each of the large estates… under the control of the Agricultural Laborers’ Deputies and for the public account.

7. The immediate amalgamation of all banks in the country into a single national bank, control over which shall be exercised by the Soviet of Workers’ Deputies.

8. Our immediate task is not to “introduce” socialism, but only to bring social production and distribution of products at once under the control of the Soviet of Workers’ Deputies.

9. Party tasks:

(a) Immediate summoning of a Party congress. (b) Alteration of the Party program, mainly:

(1) On the question of imperialism and the imperialist war; (2) On the question of our attitude towards the state and our demand for a “commune state”. (3) Amendment of our antiquated minimum program.

(c) A new name for the Party.

10. A new International. Instead of ” Social Democrats”, whose official leaders throughout the world have betrayed socialism … we must call ourselves a Communist Party.

Source: V. I. Lenin, Selected Works in Two Volumes (Moscow: Foreign Language Publishing House, 1952), Vol. 2, pp. 3-17.

Comments are closed.

- February Revolution

- Formation of the Soviets

- April Crisis

- Revolution in the Army

- Kornilov Affair

- Bolsheviks Seize Power

- First Bolshevik Decrees

- Constituent Assembly

- Treaty of Brest Litovsk

- FOUR KINDS OF STATES

- Communist Party Building

- Economic Apparatus

- Building the Soviets

- Red Guard into Army

- State Security

- DISINTEGRATION OF THE OLD SOCIETY

- Depopulation of the Cities

- Food Supply

- Conflict with the Church

- Death of the Old Culture

- Destruction of the Left

- The Empire Falls

- CREATION OF A NEW SOCIETY

- New Letters and Dates

- Culture and Revolution

- The New Woman

- Workers Organization

- Peasant Revolution

- Organs of the Press

- Raising Socialist Youth

We will keep fighting for all libraries - stand with us!

Internet Archive Audio

- This Just In

- Grateful Dead

- Old Time Radio

- 78 RPMs and Cylinder Recordings

- Audio Books & Poetry

- Computers, Technology and Science

- Music, Arts & Culture

- News & Public Affairs

- Spirituality & Religion

- Radio News Archive

- Flickr Commons

- Occupy Wall Street Flickr

- NASA Images

- Solar System Collection

- Ames Research Center

- All Software

- Old School Emulation

- MS-DOS Games

- Historical Software

- Classic PC Games

- Software Library

- Kodi Archive and Support File

- Vintage Software

- CD-ROM Software

- CD-ROM Software Library

- Software Sites

- Tucows Software Library

- Shareware CD-ROMs

- Software Capsules Compilation

- CD-ROM Images

- ZX Spectrum

- DOOM Level CD

- Smithsonian Libraries

- FEDLINK (US)

- Lincoln Collection

- American Libraries

- Canadian Libraries

- Universal Library

- Project Gutenberg

- Children's Library

- Biodiversity Heritage Library

- Books by Language

- Additional Collections

- Prelinger Archives

- Democracy Now!

- Occupy Wall Street

- TV NSA Clip Library

- Animation & Cartoons

- Arts & Music

- Computers & Technology

- Cultural & Academic Films

- Ephemeral Films

- Sports Videos

- Videogame Videos

- Youth Media

Search the history of over 866 billion web pages on the Internet.

Mobile Apps

- Wayback Machine (iOS)

- Wayback Machine (Android)

Browser Extensions

Archive-it subscription.

- Explore the Collections

- Build Collections

Save Page Now

Capture a web page as it appears now for use as a trusted citation in the future.

Please enter a valid web address

- Donate Donate icon An illustration of a heart shape

The April Theses

Bookreader item preview, share or embed this item, flag this item for.

- Graphic Violence

- Explicit Sexual Content

- Hate Speech

- Misinformation/Disinformation

- Marketing/Phishing/Advertising

- Misleading/Inaccurate/Missing Metadata

plus-circle Add Review comment Reviews

Download options, in collections.

Uploaded by Pulsar152 on June 17, 2022

SIMILAR ITEMS (based on metadata)

HIST362: Modern Revolutions (2022.A.01)

Enrollment options.

- Time: 86 hours

- Free Certificate

April 1917: How Lenin Rearmed

“Now one has to engage in excavations, as it were, in order to bring undistorted Marxism to the knowledge of the mass of the people.”

–Vladimir Lenin, State and Revolution

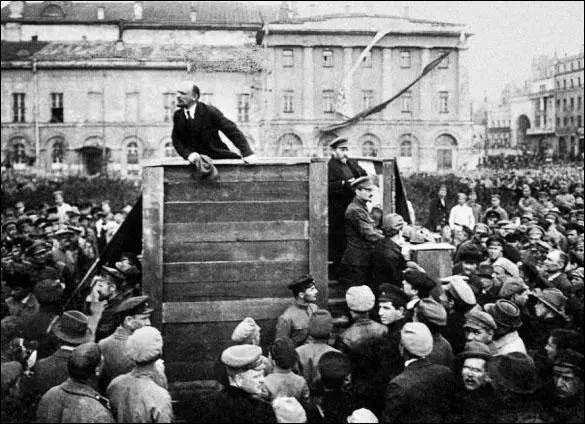

When Bolshevik Party leader Lenin returned from exile to Petrograd on April 3, 1917—scarcely more than a month after the February revolution that overthrew Russia’s autocracy—he delivered a speech to a gathering at Bolshevik headquarters, where, according to an eyewitness, N. N. Sukhanov, he declared: “We don’t need a parliamentary republic, we don’t need bourgeois democracy. We don’t need any government except the Soviet of workers’, soldiers’, and farm-laborers’ deputies!” 1

Lenin’s speech, Sukhanov informs us, shocked not only him—a Menshevik—but also the Bolshevik party members there. “No one had ever dreamt of them [soviets] as organs of state power, and unique and lasting enduring ones besides,” he added. 2 Another eyewitness,

the Bolshevik sailor F. F. Raskolnikov, confirmed Sukhanov’s impressions, writing that among the “most responsible party workers” present at the meeting, Lenin’s speech “laid down a ‘Rubicon’ between the tactics of yesterday and those of today.” 3

Lenin’s speech, and the “Theses” he presented the next day at a party conference and in subsequent speeches and writings over the following few weeks, 4 as we shall see, reflected an entirely new approach not only to the question of state power in the Russian Revolution, but constituted an entirely different conception of state and revolution than that held by almost any other living Marxist at the time. 5

Lenin completely reoriented the Bolshevik Party and set the stage over the coming months for the Bolshevik Party’s spectacular growth in size and influence, as its call for “All Power to the Soviets” became a rallying cry for workers and soldiers throughout Russia, setting stage for a second revolution, October, that brought the working class and poor peasants to power.

That Lenin’s views were, to one degree or another, at odds—and in some cases quite sharply—with the prevailing views of most of his fellow Bolsheviks is well documented by many eyewitnesses, and can be easily traced in the published articles and letters of the time. These differences persisted in different forms throughout the revolutionary process, but the confusion in the party was clearest in the weeks immediately following the February Revolution. The party’s confusion in part derived from the way in which it was disorganized by mass arrests and severe police repression, suddenly facing the test of a revolutionary situation.

The Bolsheviks—the militant wing of the Russian socialist movement—had the deepest roots in the industrial working class of all radical parties. But the war period had decimated the party’s ranks. By the outbreak of February, the party had 24,000 members nationwide—with about 3,000 members in Petrograd, and 500 in the militant working-class Vyborg district. Most leading Bolsheviks were either in prison, Siberia, or exile. For much of the year leading up to February, there were no members of the Russian Bureau of the Central Committee available in Russia. The party’s entire Petersburg Committee was arrested in January 1917, and most of the reconstituted committee was again arrested three days before the outbreak of the February Revolution, forcing the Vyborg committee to assume leadership in Petrograd. 6

But the party’s confusion in this period was also political, a product of the contradictions inherent in the pre-1917 Bolshevik program (a program Lenin had been central to developing), which was preventing party members from fully coming to terms with the unforeseen and entirely new relation of forces created by the February Revolution. 7

Leon Trotsky, writing many years later, considered Lenin’s timely intervention in this period as the key to the October Revolution’s success:

The arrival of Lenin in Petrograd . . . turned the Bolshevik party in time and enabled the party to lead the revolution to victory. Our sages might say that had Lenin died abroad at the beginning of 1917, the October revolution would have taken place “just the same.” But that is not so. Lenin represented one of the living elements of the historical process. He personified the experience and the perspicacity of the most active section of the proletariat. His timely appearance on the arena of the revolution was necessary in order to mobilize the vanguard and provide it with an opportunity to rally the working class and the peasant masses. Political leadership in the crucial moments of historical turns can become just as decisive a factor as is the role of the chief command during the critical moments of war. History is not an automatic process. Otherwise, why leaders? Why parties? Why programs? Why theoretical struggles? 8

The purpose of this article is not to recount the entire history of the revolution, but to focus on one particular question: if Lenin’s role was essential in rearming the Bolshevik Party and making it “fit” to lead the October Revolution, what prepared Lenin to break with what had been the party orthodoxy? What were the contributing factors that allowed Lenin to rearm himself in order to be in a position to rearm the party?

There were several elements to Lenin’s thinking that this article will lay out. First was Lenin’s willingness to compare theory to practice—and to reassess and make tactical, even programmatic, adjustments based on the course of real events. This has often been presented as Lenin’s willingness to blow with the prevailing winds for the purposes of expediency. 9 But in reality Lenin always considered problems from both sides—the theoretical and the practical—always with the aim of using theory as a guide to practical action. As Karl Radek put it, “Lenin’s greatness lies in the fact that he never permits himself to be blinded to a reality when it is in process of transformation, by any preconceived formula, and that he has the courage to throw yesterday’s formula overboard as soon as it disturbs his grasp of this reality.” 10

Second, the imperialist war compelled Lenin to see Russia’s revolution even more clearly than in the past as part of an international struggle for socialism. The war, in his estimation, brought the question of socialist revolution into the realm of immediate policy, rather than far-off possibility. This was for two reasons: first, the imperialist war was proof that world capitalism had reached the stage in which the productive forces had outstripped the ability of national borders to contain them, and that internationally the productive forces had reached the point where socialism could be realized in practice. Second, the imperialist war was the product and producer of deep social contradictions that would lead to an upswing of struggles internationally—of workers, and of oppressed nations and peoples—that would create the subjective basis for the revolutionary transformation of a number of countries.

Given the urgency of the impending revolutionary situation Lenin saw developing in war-torn Europe and Russia, and given the collapse of the main socialist parties into support for their “own” governments in the imperialist war, Lenin now understood the international significance of Bolshevik experience in breaking organizationally from opportunism and reformism, and the necessity of applying this experience to the socialist movement internationally .

And finally, and perhaps most importantly for the purposes of this article, in the weeks immediately prior to the outbreak of the February Revolution, Lenin completely reassessed his own views of the state. As a result of a dispute with fellow Bolshevik Nikolai Bukharin in 1916, Lenin engaged in a deep study of the writings of Marx and Engels on the origins of the state and its role under capitalism, and decided that the entire Marxist movement worldwide had distorted Marx’s teachings. This theoretical reorientation—all of which took place prior to the outbreak of the February Revolution—was essential in preparing Lenin for the leap he was soon to take.

The context

The character of the 1917 Russian Revolution was a product of the peculiarities of Russia’s development. As a latecomer to capitalism, Russia did not repeat the gradual stages of Britain’s industrial development; instead, the most modern capitalist enterprises were grafted—under the direct intervention of the state and western banks—on top of Russia’s predominantly archaic agricultural society. In Russia’s main cities modern factories, employing thousands of workers each in some cases, sprang up quickly in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The result was a relatively small (3–5 million) but heavily concentrated working class in a society still predominately peasant and rural in composition (150 million peasants).

The implications of these developments on the nature of the Russian Revolution were well laid out in Rosa Luxemburg’s 1906 work, The Mass Strike .

It is not the bourgeoisie that is now the leading revolutionary element, as in the earlier revolutions of the West, while the proletarian masses, disorganized among the petty bourgeoisie, furnish material for the army of the bourgeoisie, but on the contrary, it is the class-conscious proletariat that is the active and driving element, while the big bourgeois sections are partly directly counterrevolutionary, partly weakly liberal, and only rural petty bourgeoisie and the urban petty bourgeois intelligentsia are definitively oppositional and even revolutionary minded. 11

In 1917, Russia’s “peculiar mixture of backward elements with the most modern factors,” rendered Russia’s bourgeoisie politically paralyzed and Russia’s working class the only urban force capable of taking the initiative in solving the pressing needs of the peasantry. As a result, argued Trotsky, summing up the character of 1917, “In order to realize the soviet state, there was required a drawing together and mutual penetration of two factors belonging to completely different historic species: a peasant war—that is, a movement characteristic of the dawn of bourgeois development—and a proletarian insurrection, the movement signalizing its decline. That is the essence of 1917.” 12

The outbreak of World War I in 1914 at first retarded the revolutionary movement in Russia, and then—as a result of the devastation and privations of the war, and the tearing of masses of peasants from the land and into soldiers’ uniforms—accelerated it.

In late February 1917, a strike of women workers over bread shortages initiated a wave of strikes and street protests in Petrograd over several days that brought down the autocratic Romanov dynasty that had ruled the country for three centuries.

The February events gave rise to two centers of power: what came to be described as “dual power.” On the one hand, workers—whose efforts had brought the tsar down—quickly moved to establish soviets, councils of workers’ delegates elected directly from the workplaces, and later from soldiers’ units. The central, leading soviet was the Petrograd Soviet of Workers’ and Soldiers’ Deputies, led by an executive committee initially dominated by leaders of the moderate socialist parties, the Mensheviks, and the Socialist Revolutionaries (SR).

Simultaneously, and with the encouragement of moderate socialists, liberal bourgeois leaders from the old Duma (the sham parliament that had existed under Tsar Nicholas’s rule) hastily formed the Provisional Government. This government consisted of capitalists, lawyers, and landowners who looked with horror upon the stormy action of the masses in Petrograd and paid only lip service to the revolution in order to contain it. The Provisional Government was committed to continuing Russia’s involvement in World War I and opposed to the demands of workers and peasants. The moderate socialist parties, in turn, took a position of “revolutionary defensism,” which insisted that the overthrow of the autocracy and the establishment of a democratic Russia justified military defense of Russia against Germany.

It was clear at this stage that the soviet had almost all the power in its hands to dispose of as it pleased. The mass of workers in Petrograd looked to the soviet as an expression of their interests. The Provisional Government’s ability to rule (even its creation) rested on the assistance and acquiescence of the moderate socialists that at that point dominated the soviet. 13 The workers of Petrograd—including a good number of Bolshevik militants—who had led the strikes and street protests that brought the tsar down—were overwhelmed by a much larger mass of newly radicalized soldiers and workers who, for the time being, placed their hopes in the leadership of the moderate socialists, who in turned offered support to the Provisional Government.

The debates among the different wings of the socialist movement in Russia about the future course of the revolution now revolved around these questions: what attitude to take to the war (which still raged), to the Provisional Government (dominated by capitalist interests), and to the workers’ soviets. The answer each arrived at was driven by different estimations of the class character of the revolution, its possibilities, and its limits.

The nature of Lenin’s break

On April 4, the day after his arrival in Petrograd, Lenin wrote what became known as his “April Theses,” elaborating on a point he made in his speeches of the previous day:

The specific feature of the present situation in Russia is that the country is passing from the first stage of the revolution—which, owing to the insufficient class-consciousness and organization of the proletariat, placed power in the hands of the bourgeoisie—to its second stage , which must place power in the hands of the proletariat and the poorest sections of the peasants.

A “return to a parliamentary republic from the Soviets of Workers’ Deputies,” he argued, “would be a retrograde step.” 14

Lenin denounced the Provisional Government for its support for the war, as well as the moderate soviet leaders’ justification of the war as a “defense” of revolutionary Russia, writing that since the war “remains on Russia’s part a predatory imperialist war owing to the capitalist nature of that government, not the slightest concession to ‘revolutionary defensism’ is permissible.” The only way to end the war, he wrote soon after, was through “overthrowing the power of capital,” concentrated in the Provisional Government, and “transferring state power to another class, the proletariat.” 15

In the meantime, it was impermissible for Bolsheviks to demand that the Provisional Government “ cease to be an imperialist government,” because this would breed illusions. 16 As long as the masses continued to have illusions in the Provisional Government and put its faith in the moderate soviet leaders, the immediate task was one of propaganda—to “patiently explain” to the masses the counterrevolutionary nature of the Provisional Government and the need to transfer all power to the soviets; experience would soon teach the masses of the treachery of the Provisional Government and that all power must be transferred to the soviets.

Prior to this, no Bolshevik had ever written or spoken of the coming Russian Revolution transferring class power from the bourgeoisie to the working class and poor peasants. The revolution was conceived as one in which an insurrection bringing down the tsar would be followed by, at the very least, a brief period of bourgeois rule.

Three basic concepts of the Russian Revolution

Prior to 1917, the two main trends in the Russian socialist movement, Menshevik and Bolshevik, agreed on the “bourgeois-democratic” character of the Russian Revolution, but sharply disagreed on its class content. “That our revolution is bourgeois, that it must conclude by destroying the feudal and not the capitalist order, that it can be crowned only by a democratic republic—on this, it seems, all are agreed in our party,” a young Stalin wrote in 1907. 17

The Mensheviks, however, concluded from this that the working class must ally itself with the liberal bourgeoisie. Since the revolution’s aim was the establishment of the conditions for capitalist development in a largely backward peasant economy, the working class should encourage the bourgeoisie, “in no case intimidating it by putting forward the independent demands of the proletariat.” 18 It was thus necessary for socialists to place limits on the working-class struggle so as to ensure that the bourgeoisie take its rightful place at the head of the revolution.

The Bolsheviks argued that the lateness of capitalist development in Russia rendered the bourgeoisie too weak and dependent on the semi-feudal tsarist state, too intertwined with the landowning class, and too frightened of worker and peasant revolt from below, to play a leading role.

Not frightening the bourgeoisie merely meant putting the workers’ and peasants’ faith in a class incapable of, and even opposed to, carrying through “its own” revolution. The revolution could only succeed as an insurrectionary movement led by the working class—organized as a leading and independent detachment—in alliance with the poor peasants.

But given the divergent class interests between the working class and the peasantry—the former seeking socialism, the latter land redistribution—the alliance could only be a temporary one. Hence the revolution would be accomplished through the establishment of a “dictatorship of the proletariat and peasantry”—a provisional dictatorship that would “completely crush all resistance by reaction, ensure complete freedom for election agitation, convene on the basis of universal, equal and direct suffrage by secret ballot a constituent assembly capable of really establishing the sovereignty of the people and putting into effect the minimum social and economic demands of the proletariat.” 19 As Lenin wrote in November 1905, “Purely socialist demands are still a matter of the future.” 20

Socialists, argued Lenin, could not refuse to participate in a revolutionary provisional government in order to push the revolution as far it could go. The Menshevik position, on the other hand, was that only a bourgeois government could emerge from revolution, and from that they drew contradictory conclusions: socialists should remain outside it as an “extreme revolutionary opposition.” Entering such a government might compromise socialists who could not fulfill the party’s socialist program, as well as causing “the bourgeois class to recoil from the revolution and thus diminish its sweep.” 21

Where the Mensheviks subordinated the class interests of workers to those of the liberals, Lenin repeatedly emphasized the necessity for the class independence of the working class as a condition for it being in a position to play the vanguard role in Russia’s revolution. “The Bolsheviks claimed for the proletariat the role of leader in the democratic revolution,” wrote Lenin. “The Mensheviks reduced its role to that of an ‘extreme opposition.’ . . . The Mensheviks always interpreted the bourgeois revolution so incorrectly as to result in their acceptance of a position in which the role of the proletariat would be subordinate to and dependent on the bourgeoisie.” 22

Leon Trotsky held a third position that placed him closer to Lenin and the Bolsheviks (though organizationally in this period he was closer to the Mensheviks), but took Lenin’s analysis a step further. The working class, he agreed, would play the leading role in the revolution; and it would have support of the peasantry. But the latter was incapable of playing an independent role. Having led a successful revolution against tsarism, the working class would assume direct power and be compelled to burst the framework of the bourgeois revolution and proceed to begin implementing socialist measures, whose success could only be guaranteed in the context of international revolution. “Left to its own resources,” he wrote in his 1906 work Results and Prospects, “the working class of Russia will inevitably be crushed by the counter-revolution the moment the peasantry turns its back on it. It will have no alternative but to link the fate of its political rule, and, hence, the fate of the whole Russian revolution, with the fate of the socialist revolution in Europe.” 23 This prognosis, as it turned out, was the closest to predicting the actual course and outcome of the 1917 revolution.

Lenin on soviets in 1905 and 1917

After the emergence of the Petersburg Soviet in October 1905, Lenin tentatively argued in a letter to the party’s newspaper that Bolsheviks must enter and support the soviets, and that “the Soviet of Workers’ Deputies should be regarded as the embryo of a provisional revolutionary government .” 24 After this, Lenin and the Bolsheviks repeatedly pointed to the soviet as a potential form that could be taken by a provisional revolutionary government. 25 This should not, however, be seen as the same position Lenin took in 1917. In November 1905, Lenin makes clear that the party’s participation in what he calls “non-party” organizations (like soviets) is only “temporary,” specifically related to the necessity of joining forces for the purposes of struggle in the “democratic revolution.” 26 This is a far cry from Lenin’s positive view of soviets as the potential vehicle for proletarian rule in 1917.

A few years before the fall of the tsar, in October 1915, Lenin still considered the immediate tasks of the coming Russian revolution to be bourgeois : “The most correct slogans are the ‘three pillars’ (a democratic republic, confiscation of the landed estates and an eight-hour working day).” 27 In keeping with what he had written during and after the 1905 revolution, Lenin noted that “Sovietsof Workers’ Deputies and similar institutions must be regarded as organs of insurrection, of revolutionary rule.” 28 Soviet power, however, was still limited to the 1905 framework. At the same time, the democratic revolution in Russia is presented as the harbinger of world socialist revolution: “Thetask confronting the proletariat of Russia,” he continued, “is the consummation of the bourgeois-democratic revolution in Russia in order to kindle the socialist revolution in Europe.” 29

Before February, the Bolshevik party saw the “immediate task” to be the overthrow of tsarism and the clearing away of all feudal remnants, under a provisional revolutionary government—provisional in the strict sense of being transitory —to give way to the convocation of a constituent assembly and the establishment of a bourgeois democratic republic; only then could a fight for socialism begin. 30 In April, with tsarism already overthrown, Lenin now argued that the immediate task was to establish soviet power—not as a provisional government to clear away feudal remnants, but as a form of workers’ power that would be used to begin the process sweeping away capitalism.

The Bolshevik Party in March 1917

What were the policies pursued by the Bolsheviks before Lenin’s return? The Bolsheviks’ first measure involved attempts to press the old slogans into the new situation, and the results were varied. As outlined by historian D. A. Longley, there were essentially four positions in the Bolshevik party coming out of the February Revolution, held by four different sections of the party. 31 All of them derived, or were essentially based on, the pre-1917 Bolshevik program.

The Vyborg district Bolshevik committee, whose activists played an outsized role in the successful strikes and street actions that overthrew the tsar, called for the creation of soviets out of which should issue a “provisional revolutionary government.” Once this body was set up, they demanded, all support must be withdrawn from the Duma-created Provisional Government. They limited a future soviet-based government, however, to fulfilling the party’s minimum demands—that is, the creation of a bourgeois-democratic republic. Their approach, as Longley notes, was in accordance with party policy developed during the 1905 revolution. 32

A second position—but similar to Vyborg—was taken by the three members of the Russian Bureau of the Central Committee, Alexander Shliapnikov, Vyacheslav Molotov, and Peter Zalutsky, who issued a manifesto against the Provisional Government, denouncing it as a government of the big bourgeoisie and the landowners, and calling for the creation of a provisional revolutionary government established by the “revolutionary insurgent peoples” that would implement the minimum program: democratic rights, confiscation of church and crown lands, the eight-hour day, and the convocation of a constituent assembly elected by universal suffrage. But the Russian Bureau hit a wall when they discovered that the moderates rejected this position and were unwilling to form a government.

The Petersburg Committee, which had been devastated by arrests and had only recently been reconstituted in March—with many who had not participated in the revolution—took a more conservative line, calling for critical support for the Provisional Government, passing a March 3 resolution stating that the party would “not oppose the power of the Provisional Government in so far as its activities correspond to the interests of the proletariat and of the broad democratic masses of the people.” 33

Now that tsarism had been overthrown, some members of the Petersburg committee wanted to drop the Bolsheviks’ opposition to the war and adopt a revolutionary defensist line on the grounds that “our front must be defended against German attack.” 34 The Petersburg Committee also refused to support a Vyborg resolution in support of a strike for the eight-hour day that was now raging in Petrograd and against the Soviet Executive Committee’s call that workers return to work. 35

The situation in the party became more confused with the return from Siberian exile of Bolshevik Central Committee members Joseph Stalin, Lev Kamenev, and the former Duma deputy Matvei Muranov. They promptly took over the editorship of the Bolshevik’s paper Pravda and implemented a right turn on its pages that rendered it “in a flash,” according to Sukhanov, “unrecognizable.” 36 Kamenev’s Pravda articles called for supporting the Provisional Government for the “objectively revolutionary steps that it is compelled to take and to the extent that it actually undertakes them,” 37 and adopted the defensist position of the moderate socialists. Since the “banners” of the workers and peasants have replaced the “banner” of the tsar, and since the German masses have not yet risen up to stop the war, the “free people” of Russia must “stand firmly at their post,” replying “bullet for bullet and shell for shell,” he wrote in a lead March 15 editorial. 38

Stalin too took a stance of critical support for the Provisional Government, calling upon workers and peasants to “bring pressure on the Provisional Government to make it declare its consent to start peace negotiations immediately,” and offering critical support for an appeal “to the peoples of the world” issued by the Petrograd Soviet Executive that stated, “The Russian revolution will not retreat before the bayonets of conquerors.” 39

Shliapnikov’s memoirs report that liberal politicians and the moderate socialists were “buzzed” over the apparent triumph of the “moderate and sensible Bolsheviks” reflected in the new Pravda line, whereas “in outlying districts,” Bolshevik party members demanded that the paper’s new editors be expelled. 40

Prior to 1924, (when the campaign began against “Trotskyism” and the party leadership under the triumvirate of Stalin, Kamenev, and Zinoviev began to rewrite, and later under Stalin’s dictatorship, completely doctor the history of the party) the accounts by party members of this period uniformly tell the same story and are summed up by veteran Bolshevik Michael Olminsky, who in 1921 wrote that “an obligatory premise for every member of the party, the official opinion of the party, its continual and unchanging slogan right up to the February revolution of 1917, and even some time after” was that “the coming revolution must be only a bourgeois revolution.” 41

“All the comrades before the arrival of Lenin were wandering in the dark,” remarked Bolshevik leader Ludmilla Stahl. “We know only the formulas of 1905. Seeing the independent creative work of the people, we could not teach them. . . . Our comrades could only limit themselves to getting ready for the Constituent Assembly by parliamentary means, and took no account of the possibility of going farther.” 42

In late March the Bolsheviks held a party conference whose proceedings clearly indicate the confusion that still existed in the party. Stalin, who delivered the opening report, called for critical support of the Provisional Government, describing it as the “fortifier of the conquests of the revolutionary people” (that in an unspecified time in the future would become “an organ for organizing the counterrevolution”). Throughout the discussion, many delegates spoke of “support insofar as,” exercising “control” over the government, making “demands” on it, and so on.

Only a handful of Bolsheviks argued differently: “The government is not fortifying but checking the course of the revolution,” argued N. Skrypnik. After a speech by a nonparty social democrat M. Steklov on the activities of the Provisional Government (which was not recorded), its counterrevolutionary nature had become so clear to the delegates that Stalin put forward a motion to drop from the resolution on the Provisional Government any talk of support for it. But the resolution still included a call for the “revolutionary democracy” to “exercise vigilant control” over the Provisional Government, “urging it on toward a most energetic struggle for the complete liquidation of the old regime”—just the kind of illusion-breeding demands Lenin would attack when he appeared on the last day of the conference to deliver the contents of his April Theses (April 4). One of the conference sessions entertained a proposal by the Menshevik leader Nikolai Tseretelli, and supported by Stalin, Kamenev, and others, for unity talks between the Bolshevik and Menshevik parties. 43

The first reason for the party’s confusion was simply that events had evolved in an unexpected way. The autocracy was not overthrown in 1905, only threatened. The Bolsheviks viewed participation, indeed leadership, in such a government imperative and the sequence of events in which the tsarist government would fall and be replaced by such a government. In 1917, by contrast, the tsar was overthrown in a matter of days, and revolutionaries were immediately presented with an unforeseen situation: a dual power consisting of soviets and a bourgeois provisional government. 44

But the confusion was also political , in the sense that the Bolsheviks were not, as we have shown, programmatically equipped to see the soviets as a more permanent form of workers’ power.

Now that the tsar was gone, what attitude should Bolsheviks take to the Provisional Government? It clearly was not the “dictatorship of the proletariat and peasantry.” On the contrary, it was a bourgeois government committed to maintaining the landlords’ estates, curtailing the class struggle in the factories, and continuing Russia’s involvement in the war. No Bolshevik could argue to “join” or participate in it (the policy in 1905). Clearly it was necessary to support and build up the soviets. But to what end? Should they “pressure” the Provisional Government, or overthrow it? And if overthrown and replaced by soviet power—do the soviets, as per the 1905 scenario, give way to a constituent assembly, or the hitherto unacceptable , and take steps toward socialism—essentially adopting Trotsky’s position?

The Mensheviks, in keeping with their view that the revolution was bourgeois (and that the working class should not “frighten” the liberals), did an about-face and moved from critical support to actual participation in the Provisional Government.

After Lenin’s arrival the party shifted left in only a matter of weeks and took a more decisive and unified stand. This was due to several factors: one, sections of the party in Vyborg and on the Russian Bureau, as we have seen, were already inclined— based on the old formula—to reject the Provisional Government and support the soviets.

But a second, equally important reason is that events themselves—that is, the increasingly obvious counterrevolutionary intent of the Provisional Government—pushed the party in a more decisive direction.

Lenin argued in his “April Theses” and related articles and speeches that the slogan “All power to the soviets” was not a call for the immediate overthrow of the Provisional Government; to attempt that it was necessary to engage in “patient, systematic, and persistent explanation” in order to win over the masses, “so that the people may overcome their mistakes by experience.” 45 And indeed in April it was not just Lenin’s persuasive analysis of the situation, but also the confirmation of it in experience, that contributed to the speed with which he was able to win the debate in the party.

Trotsky describes the sense of disappointment in the government already developing among the masses, exhibited in the massive May Day demonstration held on April 18, where an “attentive ear might have caught already among the ranks of the workers and soldiers impatient and even threatening notes.” In addition to anger over rising prices and bread ration cuts, workers chafed at the resistance of the bosses and the government to the eight-hour day. Soldiers expressed dismay over the question of the war’s continuation: “When will the revolution bring peace? What are Kerensky and Tseretelli waiting for? 46

On the very day this demonstration took place, the bourgeois Cadet minister of foreign affairs, Paul Miliukov, sent a message to Russia’s war allies that stated Russia’s war intentions as purely defensive, but he attached a note to it assuring the allies that in Russia “the universal desire to carry the world war through to a decisive victory had only been strengthened.” 47 The note was published a few days later and caused a firestorm among the masses that came out into the streets in protest to demand Miliukov’s resignation—which happened on May 2—causing the reshuffling of the cabinet and the inclusion in it of five moderate socialists in addition to Kerensky.

Such was the shift leftward in response to this crisis that by the end of April the Bolsheviks had already achieved a majority in the Vyborg, Vasiliev Island, and Narva district soviets. These developments in the class struggle nudged the Bolsheviks toward Lenin’s position, and explain why Lenin was able to marginalize the party’s right wing (Kamenev, Rykov, Nogin, Ryazanov, and others) so quickly. The latter shifted to supporting Lenin’s slogan “All power to the soviets”; but they interpreted it not as a shift toward workers’ power but as the basis of a coalition government of all left-wing parties that would, in time, hand power over to the Constituent Assembly. 48 What Lenin had to say in April 1917—and we will elaborate further on this below—went well beyond this conception.

How Lenin rearmed

As noted earlier, there were essentially three main reasons why Lenin was more prepared than other Bolshevik leaders to grasp the new situation in Russia (though at this time he was largely reading only the bourgeois foreign press to get his information) and to quickly outline with clarity and depth a way forward. First was Lenin’s attentiveness to real changes in the world and his willingness on this basis to reassess “what is to be done,” a trait he had amply demonstrated in the past. He made this clear in his debate with Kamenev and other Bolsheviks when he returned in April:

“Our theory is not a dogma, but a guide to action,” Marx and Engels always said, rightly ridiculing the mere memorizing and repetition of “formulas,” that at best are capable only of marking out general tasks, which are necessarily modifiable by the concrete economic and political conditions of each particular period of the historical process. 49

As historian E. H. Carr explains, the key issue between Lenin and Kamenev was

narrowed down to the question whether, as Lenin proposed, the party should work for the transfer of power to the Soviets, or whether, as Kamenev desired, it should be content with “the most watchful control” over the Provisional Government by the Soviets, Kamenev being particularly severe on anything that could be construed as incitement to overthrow the government. 50

Kamenev argued that the “bourgeois-democratic revolution” was not yet completed—because there had yet been no agrarian reform under workers’ and peasants’ power—and therefore the “old Bolshevik” program still applied. To this Lenin replied that power had already passed into the hands of the bourgeoisie and in that sense the “bourgeois-democratic revolution” had already been completed. By this Lenin did not mean that the demands of the revolution, in particular for peace and land, had been achieved, but in the strict sense that power had passed from one class to another, while another potential power, the soviets, had acquiesced to it. The only way now to complete these tasks was to break from the moderate defensist parties that were propping up the counterrevolutionary Provisional Government and transfer power to a new class. As Trotsky summarizes in History of the Russian Revolution:

Lenin saw, of course, as clearly as his opponents that the democratic revolution was not finished, that on the contrary without really beginning it had already begun to drop into the past. But from this very fact it resulted that only the rulers of a new class could carry it through to the end, and that this could be achieved no otherwise but by drawing the masses out from under the influence of the Mensheviks and Social Revolutionaries—that is to say, from the indirect influence of the liberal bourgeoisie. 51

It was no use, Lenin insisted in the debate,

reiterating formulas senselessly learned by rote instead of studying the specific features of the new and living reality. . . . The person who now speaks only of a “revolutionary democratic dictatorship of the proletariat and the peasantry” is behind the times, consequently, he has in effect gone over to the petty bourgeoisie against the proletarian class struggle; that person should be consigned to the archive of “Bolshevik” pre-revolutionary antiques (it may be called the archive of “old Bolsheviks”). 52

The question now was not to differentiate the working-class policy of soviet power as a means to bringing an end to war from the “democracy” that was using the mantle of revolution to bring the revolution to a stage “acceptable” to the liberal bourgeoisie. “Old Bolshevism should be discarded,” he said on April 14. “To be revolutionaries, even democrats, with Nicholas removed, is not great merit. Revolutionary Democracy is not good at all; it is a mere phrase” that “covers up rather than lays bare the antagonism of class interests.” 53

It wasn’t simply, though, that Lenin grasped that the old Bolshevik program was outdated—it was also that he had made a theoretical shift based on a reassessment of the Marxist understanding of the role of the state. But before we deal with this question, we must first look at the impact of the imperialist war on Lenin’s thinking.

The prospects for world revolution

For our purposes, we will focus in on a few key points that were made clear to Lenin by the war, and which he hammered on in many articles. Imperialism represented capitalism’s “highest” or “latest” stage, which Lenin defined as the emergence, through the concentration and centralization of capital, of giant, state-backed monopolies; the export of capitalism overseas; and the carving up of the globe into “spheres of interest” between the world’s biggest capitalist powers.

The world war, Lenin argued, was not based on mistaken policy but resulted from the unavoidable clash between the world’s leading capitalist powers vying for world domination, a “struggle for markets and for freedom to loot foreign countries.” 54 Monopoly capitalism had reached a stage in which the struggle for political and military dominance was an inbuilt and inevitable feature of the world system.

Capitalism had reached a stage where decay and stagnation had begun to set in—a process that would persist so long as capitalism continued. Capitalism developed extremely unevenly, producing both dominant imperialist powers and subordinating, weaker nations; nevertheless, material conditions on a world scale were now fully ripe for the creation of socialism:

Imperialismis the highest stage of development of capitalism. Capital in the advanced countries has outgrown the boundaries of national states. It has established monopoly in place of competition, thus creating all the objective prerequisites for the achievement of socialism. Hence, in Western Europe and in the United States of America, the revolutionary struggle of the proletariat for the overthrow of the capitalist governments, for the expropriation of the bourgeoisie, is on the order of the day. 55

The support of German social democrats and other socialist leaders for their “own” government’s war effort was a grave “betrayal” of working-class internationalism, their prewar pledge to oppose the outbreak of war and to use the war, when it came, to hasten capitalism’s downfall. The socialist leaders’ shift to support for their own respective countries signaled the bankruptcy of the Second International. This betrayal was not accidental. It had its roots in the creation of a layer of officialdom (in the trade unions, the party press, and parliamentary wings) within the socialist movement, fattened from the crumbs of imperialism and seeing organizational preservation taking precedence over challenging the system, who used socialist rhetoric to cover up their accommodation to the status quo. This state of affairs required that genuine internationalists prepare to create the left-wing organizational nuclei that could begin the process of forming revolutionary parties untainted by opportunism.

This was an urgent question because the war revealed that capitalism had reached a stage of insuperable contradictions that could only be solved by its overthrow. Lenin was fully aware that the organized forces supporting such a prognosis were at that stage quite small. But the horrors and privations of the war were driving the working class into open resistance and raising the question of socialism to the level of a practical, immediate question, that is, ending the war was inseparably linked to worldwide socialist revolution—hence Lenin’s slogan, “turn the imperialist war into a civil war,” turn the weapons of war against your oppressors.

Lenin was clear that the opportunist trend brought into clear light by the outbreak of war existed from the beginning of the formation of the Second International. “Thestruggle between the two main trends in the labor movement—revolutionary socialism and opportunist socialism—fills the entire period from 1889 to 1914.” 56 Only now did Lenin argue, however, that these two trends must organizationally separate.His ability to quickly draw this conclusion was based on the Russian experience, in which the Bolsheviks had by 1912 decisively broken from the “liquidators”—that is, from the moderate socialists in Russia who wanted a legal labor party and who renounced the underground and, by extension, all talk of overthrowing the tsar. This separation Lenin now saw as an urgent international necessity.

This sense of the immanence of revolution not just in Russia, but internationally, was unique to Lenin and perhaps a handful of other revolutionaries at the time, such as Trotsky and Karl Radek. But none were as clear as Lenin in drawing immediate organizational conclusions from this fact, that revolutionaries in every country must reconstitute the nucleus of new, revolutionary organizations, free from the taint of reformism and opportunism (the common term used by the Left to describe the acceptance of short-term gain at the expense of long-term goals), in preparation for the rapid development of potential revolutionary situations as a result of the war crisis. 57

Lenin put forward a program of international revolution as the only means to put an end the imperialist slaughter:

In every country the Socialists must above all explain to the masses the indisputable truth that a genuinely enduring and genuinely democratic peace (without annexations, etc.) can now be achieved only if it is concluded not by the present bourgeois governments, or by bourgeois governments in general, but by proletarian governments that have overthrown the rule of the bourgeoisie and are proceeding to expropriate it. . . . Allpropaganda for socialism must be refashioned from abstract and general to concrete and directly practical. 58

This prognosis was predicated not only on the material ripeness of the world for the establishment of socialism, but also in terms of the subjective factor of class power and maturing consciousness. If the Paris Commune showed that workers could make a heroic attempt “to overthrow bourgeois rule and capture power for the introduction of socialism,” Lenin argued, “Then a similar attempt is a thousand times more achievable, possible and likely to succeed now, when a much larger number of better organized and more class-conscious workers of several countries are in possession of much better weapons, and when with every passing day the course of the war is enlightening and revolutionizing the masses.” 59

There can be no doubt that Lenin’s heightened internationalist perspective and orientation after the outbreak of war, his understanding of imperialism as the expression of capitalism’s ripeness for socialism, and the crisis of the war producing class and national struggles worldwide had a direct impact on his ability to shift from emphasizing working-class leadership in a bourgeois revolution to proletarian leadership in a socialist revolution . From this it was but a short step to arguing in April that, “if the state power in the two countries, Germany and Russia, were to pass wholly and exclusively into the hands of the Soviets of Workers’ and Soldiers’ Deputies, the whole of humanity would heave a sigh of relief, for then we would really be assured of a speedy termination of the war, of a really lasting, truly democratic peace among all the nations, and, at the same time, the transition of all countries to socialism.” 60

Lenin’s reassessment of the state

The third letter of Lenin’s “Letters from Afar,” written in early March—just weeks after the fall of the tsar—outlined his new position on soviet power. It is worth quoting at length:

We need revolutionary government , we need (for a certain transitional period) a state . This is what distinguishes us from the anarchists. The difference between the revolutionary Marxists and the anarchists . . . on the question of government, of the state, is that we are for , and the anarchists against , utilizing revolutionary forms of the state in a revolutionary way for the struggle for socialism. We need a state. But not the kind of state the bourgeoisie has created everywhere, from constitutional monarchies to the most democratic republics. And in this we differ from the opportunists and Kautskyites of the old, and decaying, socialist parties, who have distorted, or have forgotten, the lessons of the Paris Commune and the analysis of these lessons made by Marx and Engels. We need a state, but not the kind the bourgeoisie needs, with organs of government in the shape of a police force, an army and a bureaucracy (officialdom) separate from and opposed to the people. All bourgeois revolutions merely perfected this state machine, merely transferred it from the hands of one party to those of another. The proletariat, on the other hand, if it wants to uphold the gains of the present revolution and proceed further, to win peace, bread and freedom, must “ smash, ” to use Marx’s expression, this “ready-made” state machine and substitute a new one for it by merging the police force, the army and the bureaucracy with the entire armed people . Followingthe path indicated by the experience of the Paris Commune of 1871 and the Russian Revolution of 1905, the proletariat must organize and arm all the poor, exploited sections of the population in order that they themselves should take the organs of state power directly into their own hands, in order that they themselves should constitute these organs of state power. 61

Neither Lenin, nor any leading Marxist of the Second International held this view, which had first been expressed by Marx and Engels in their writings on the Paris Commune, that the state must be “smashed” and replaced by organs of direct working-class democracy. Soon after this, in April, Lenin linked the question of workers’ power in Russia to “introducing” measures as “a step toward socialism,” 62 based on the expectation that Russia’s revolution would be but a prelude to revolution in Europe. In Lenin’s first speech at the Petrograd City Conference on April 13, he elaborated on what he meant by the transfer of all power to the soviets. “Events have led to the dictatorship of the proletariat and peasantry being interlocked with the dictatorship of the bourgeoisie,” he said. “The next stage is the dictatorship of the proletariat . . . Soviets of Workers’ and other Deputies should be organized all over the country life itself demands it. There is no other way. This is the Paris Commune! . . . This is the type of state under which it is possible to advance towards socialism.” 63

This concept of soviet power as a step toward socialism represented, as we have already pointed out, a departure from the Bolshevik program prior to 1917; but it was also a departure from Lenin’s pre-1917 discussion of the lessons of the Commune, which, according to Lenin in 1905, “confused the tasks of fighting for a republic with the tasks of fighting for Socialism.” 64

But this was also a departure from what had to that point been Marxist orthodoxy on the question of the state, which (from both its reformist and revolutionary wings) had posited the task of socialism to be the “seizure” of state power, not its destruction and replacement by a “Commune state.” Even Trotsky, in his 1906 exposition of his theory of permanent revolution—that in Russia the belated nature of capitalist development could lead to the working class coming to power sooner there than in the more “advanced” West—could write: “Every political party worthy of its name strives to capture political power and thus place the State at the service of the class whose interests it expresses.” 65

Lenin’s reorientation on this question is often presented as if Lenin changed his views on the state after the February Revolution. It is true that Lenin wrote State and Revolution , in which he reexamines Marx and Engels’s views on the state, while he was in hiding after the abortive July demonstrations, and it was not published until 1918. As a result, his book is often presented as Lenin’s conclusions from his observations from afar February 1917. But the truth—and really, the only thing that can explain the speed with which Lenin made such a decisive shift—is that he had already changed his position prior to the outbreak of the February Revolution.

An interesting but rarely cited essay by Marian Sawer in the 1977 Socialist Register , “The Genesis of State and Revolution, ” explains the process of Lenin’s conversion, which happened through the course of 1916. As Sawyer explains:

This theoretical leap by Lenin in January–February 1917 was in no way connected with the reemergence of a soviet movement in Russia. The latter only occurred (and only at first in Petrograd) concurrently with the Revolution of 27 February, rumors of which did not reach Lenin in Zurich until 2 March (both dates given according to the Julian Calendar). Lenin had written to Kollontai on 17 February saying that he had already almost finished preparing the material for the article on the state. 66

Lenin showed no awareness in any of his writings or notes before 1917 of Marx’s argument (repeated by Engels in an 1872 preface to the Communist Manifesto) in which “the working class cannot simply lay hold of the ready-made state machinery, and wield it for its own purposes.” 67 Nor did he seem to have read Engels’s 1891 introduction to Marx’s Civil War in France :

From the outset the Commune was compelled to recognize that the working class, once come to power, could not manage with the old state machine; that in order not to lose again its only just conquered supremacy, this working class must, on the one hand, do away with all the old repressive machinery previously used against it itself, and, on the other, safeguard itself against its own deputies and officials, by declaring them all, without exception, subject to recall at any moment. 68

Lenin’s shift came about as a result of a disagreement over the question of the state with Nikolai Bukharin, with whom Lenin was already having a sharp disagreement over the national question. 69 In 1916, Bukharin wrote an article titled, “Toward a Theory of the Imperialist State,” in which he argued that the development of the capitalist state in the era of imperialism had transformed it from a guardian of capitalist interests into a monstrous bureaucratic behemoth, rendering the relationship of social democracy to the state an acute question of the day. 70 Bukharin quoted Marx and Engels to the effect that the state, a product of class society, was not needed at every stage of human development, and that in a society without classes, the state would disappear. But the real “bombshell” in his essay was the argument that it was wrong to see statism vs. antistatism as the dividing line between Marxists and anarchists:

Despite what many people say, the difference between Marxists and anarchists is not that the Marxists are statists whereas the anarchists are anti-statists. . . . The form of state power is retained only in the transitional moment of the dictatorship of the proletariat, a form of class domination in which the ruling class is the proletariat. With the disappearance of the proletarian dictatorship, the final form of the state’s existence disappears as well.

The working class, argued Bukharin, must replace the capitalist state machine and create its own temporary organs of state power. “Either the workers’ organizations, like all the organizations of the bourgeoisie, grow into the general state organization and become a simple appendage of the state apparatus, or, alternatively, they outgrow the confines of the state and explode it from within, organizing their own state power (or dictatorship).” He concluded:

In the growing revolutionary struggle, the proletariat destroys the state organization of the bourgeoisie, takes over its material framework, and creates its own temporary organization of state power. Having beaten back every counterattack of the reaction and cleared the way for the free development of socialist humanity, the proletariat, in the final analysis, abolishes its own dictatorship as well, once and for all driving an aspen stake. 71

Against this, Lenin wrote an article (where Bukharin is referred to as “Nota-Bene”) in which he reaffirmed what he considered to be the correct position:

Onthe question of the differences between socialists and anarchists in their attitude towards the state, Comrade Nota-Bene in his article…falls into a very serious error. . . . Socialists are in favor of utilizing the present state and its institutions in the struggle for the emancipation of the working class, maintaining also that the state should be used for a specific form of transition from capitalism to socialism. This transitional form is the dictatorship of the proletariat, which is also a state. Theanarchists want to “abolish” the state, “blow it up” ( sprengen ) as Comrade Nota-Bene expresses it in one place, erroneously ascribing this view to the socialists. The socialists—unfortunately the author quotes Engels’s relevantwords rather incompletely—hold that the state will “wither away,” will gradually “fall asleep” after the bourgeoisie has been expropriated. 72

Lenin added parenthetically that he hoped “to return to this very important subject in a separate article.” As Sawer explains, Lenin did return to this subject. He went back and reread everything Marx and Engels wrote on the question of the state, and compiled a series of notes on them in what is now called the “Blue Notebook.” The notebook reveals not only Lenin’s conversion to Marx and Engels’s (and Bukharin’s) arguments about the state, but also his recognition that the soviets of 1905 were akin to the Commune of 1871, and that the former represented a new form of working-class state power similar to the latter. “One could perhaps express the whole thing in a drastically abbreviated fashion as follows,” he writes in his notes: “The replacement of the old (‘ready made’) state machine and of parliaments by soviets of workers’ deputies and their mandated delegates. This is the essence of it!!” 73

Thus it is easy to see why Lenin’s “April Theses” caused such an uproar in the party: it was utilizing a new framework that Lenin had only just developed in the weeks leading up to the overthrow of the tsar in late February. And it also renders untenable the current fashionable argument that Lenin did not “rearm” the party. 74 In reality, Lenin had to theoretically rearm himself before he rearmed the party. It is this that explains why even those who were closest to Lenin’s views in Russia, for example, the workers of the Vyborg Committee, failed to expand their position against the Provisional Government and for soviet power beyond the confines of the 1905 position.

It was precisely the contradictions of the Bolshevik’s “democratic dictatorship” position, and its acceptance of the bourgeois limits of the revolution, combined with its rejection of bourgeois leadership and the necessity of proletarian hegemony to carry it out, that contributed to the confusion in the Bolshevik ranks in the early days of the revolution. That is, Lenin’s own theoretical formulations are a big factor in explaining the confusion. The right wing of the party emphasized the “bourgeois limitations,” leading to equivocation on the Provisional Government, whereas the left wing and the proletarian ranks in Vyborg emphasized the “inner dynamic of independent working-class action,” and the hegemonic role of the working class, and saw immediately the treacherous nature of the Provisional Government and the need to go beyond it.

It is this latter fact that explains why Lenin was able so quickly to win the argument in April—the party was partially prepared by its own previous perspectives, and partially unprepared by it. But those elements closest to the fighting were most inclined toward the Bolshevik’s historic emphasis on working-class leadership in the revolution and an understanding of the bourgeois liberal’s counterrevolutionary role. The Bolsheviks were the most politically prepared party in 1917, to be sure. But its politics were initially not wholly up to the task. Nevertheless, as Tony Cliff points out, “when it came to the test in 1917, Bolshevism, after an internal struggle, overcame its bourgeois democratic crust.” 75

Lenin’s role in the Russian Revolution was crucial. But he could not have played this role had a party not been built prior to 1917 that had sunk deep roots in Russia’s working class and had fought for and bled with that class. For Lenin, the course of the revolution would be determined not by preconceived formulas, but by the state of the organization and consciousness of the working class, and the way in which Russian workers could begin a process of world revolution. How far the struggle could go for him was always determined by “the dynamic of the struggle itself.” 76 At the same time, Lenin’s famed willingness to look at things afresh and in their development was grounded in a strong grasp of Marxism reinforced by bouts of serious study. But even here, he knew how to let practice reshape theory, as he did when he revisited Marx and tossed out everything he had accepted on the theory of the state prior to 1917; and it was this theoretical rearmament, as much as the other factors, that allowed him to rearm the Bolshevik Party.

Here, we must give Trotsky the final word:

The “sudden” arrival of Lenin from abroad after a long absence, the furious cry raised by the press around his name, his clash with all the leaders of his own party and his quick victory over them—in a word, the external envelope of circumstance—make easy in this case a mechanical contrasting of the person, the hero, the genius, against the objective conditions, the mass, the party. In reality, such a contrast is completely one-sided. Lenin was not an accidental element in the historic development, but a product of the whole past of Russian history. He was embedded in it with deepest roots. Along with the vanguard of the workers, he had lived through their struggle in the course of the preceding quarter century. . . . Lenin did not oppose the party from outside, but was himself its most complete expression. In educating it he had educated himself in it. His divergence from the ruling circles of the Bolsheviks meant the struggle of the future of the party against its past. If Lenin had not been artificially separated from the party by the conditions of emigration and war, the external mechanics of the crisis would not have been so dramatic, and would not have overshadowed to such a degree the inner continuity of the party’s development. From the extraordinary significance which Lenin’s arrival received, it should only be, inferred that leaders are not accidentally created, that they are gradually chosen out and trained up in the course of decades, that they cannot be capriciously replaced, that their mechanical exclusion from the struggle gives the party a living wound, and in many cases may paralyze it for a long period. 77

- N. N. Sukhanov, The Russian Revolution: A Personal Record, ed., trans., abr., Joel Carmichael, (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1984), 282.

- Ibid., 283. Sukhanov had previously held an antiwar position (he opposed the idea that a Russia should stay in the war to “defend itself,” even in the event of a “democratic” revolution.) But as he describes in his 1922 memoirs, when the revolution broke out he was convinced that the slogan “down with the war” would alienate the bourgeoisie, whom he believed should be convinced to take power. In his estimation, the working class could create “fighting organizations,” but was not prepared, politically or organizationally, for state power. “It was clear then apriori,” he writes, “that if a bourgeois government and the adherence of the bourgeoisie to the revolution were to be counted on, it was temporarily necessary to shelve the slogans against the war ,” 12.

- F. F. Raskolnikov, Kronstadt and Petrograd (London: New Park, 1982), 76–77.

- They became known famously as the “April Theses.”

- We write “almost” because the Bolshevik leader Nikolai Bukharin was an exception.

- Tony Cliff, All Power to the Soviets: Lenin, 1914–1917 (1976; repr., Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2004), 43–44.

- A detailed enumeration of many of the eyewitness accounts confirming the confusion and disagreements among Bolsheviks in the first two months of the revolution, and what I consider still to be the best political assessment of the reason for it, can be found in Leon Trotsky, “The Year 1917,” chapt. 7 in Stalin: An Appraisal (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1941). http://www.marxistsfr.org/archive/trotsky/1940/xx/stalin/ch07.htm , and in Trotsky, chap. 15 “The Bolsheviks and Lenin,” and chap. 16 “Rearming the Party” in History of the Russian Revolution (Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2017), https://www.marxists.org/archive/trotsky/1930/hrr/ . The other document that incontrovertibly demonstrates the state of the party is the minutes of the March 1917 Bolshevik Party Conference, where Lenin delivered a defense of his April Theses. These minutes were never published in Stalinist Russia, for obvious reasons, but by Trotsky (who had a copy) in his book Stalin School of Falsification (New York: Pioneer Press, 1962), 231–301, https://www.marxists.org/archive/trotsky/1937/ssf/ .

- Leon Trotsky, “The Class, the Party, and the Leadership” (1940), https://www.marxists.org/archive/trotsky... .

- Neil Harding, in his introduction to Lenin’s Political Thought (Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2009), quotes author Edmund Wilson to the effect that Lenin made tactical adjustments without any regard for theory and then “supports it with Marxist texts.”

- Karl Radek, “Lenin,” The Communist Review , May 1923, Vol. 4, No. 1, https://www.marxists.org/history/interna... .

- Rosa Luxemburg, The Mass Strike, the Political Party, and the Trade Unions, in The Essential Rosa Luxemburg , ed. Helen Scott, (Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2008), 162.

- Leon Trotsky, History of the Russian Revolution (Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2008), 39.

- At this stage the Bolsheviks were a small minority in the soviet, which was overwhelmingly dominated by the more moderate Menshevik and Social Revolutionary parties.

- Lenin, “The Tasks of the Proletariat in the Present Revolution” [hereafter April Theses], in Collected Works , Vol. 24 [hereafter CW ] (Moscow: Progress Publishers, 1980), 22, 23.

- Lenin, April Theses, 67.

- April Theses, 22.

- Quoted in Trotsky, Stalin: An Appraisal (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1941), 423.

- Quoted in G. Zinoviev, History of the Bolshevik Party from the Beginnings to February 1917 , (London: New Park, 1973), 108.

- Lenin, “A Tactical Platform for the Unity Congress of the R. S. D. L. P.; Draft Resolutions for the Unity Congress of the R. S. D. L. P.,” in the section titled, “The Provisional Revolutionary Government and Local Organs of Revolutionary Authority,” Lenin, CW Vol. 10 (1978), 147–164.

- Lenin, “The Socialist Party and Non-Party Revolutionism, CW Vol. 10 (1965), 77.

- A statement of Mensheviks in the Caucuses, quoted in Tony Cliff, Building the Party: Lenin 1893–1914 (1975; repr., Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2002), 171.

- Lenin, “Preface to the Collection Twelve Years, ” CW Vol. 13 (1972), 113.

- Leon Trotsky, Results and Prospects, in The Permanent Revolution & Results and Prospects (New York: Pathfinder Press, 1976), 115. Richard B. Day and Daniel Gaido, in their book Witnesses to Permanent Revolution (Chicago: Haymarket, 2009), have published a series of articles that show that Trotsky developed his ideas of permanent revolution in a context in which other Marxists (and not just Parvus, whom Trotsky acknowledges as having a strong impact on his views) were thinking along similar lines. These include Karl Kautsky, Rosa Luxemburg, and N. Riazanov. Luxemburg, for example, wrote that the Russian Revolution “seemed less a final descendant of the old bourgeois revolutions than a forerunner of a new series of proletarian revolutions in the west.”

- Lenin, “Our Tasks and the Soviet of Workers’ Deputies,” CW, Vol. 10, 21. The party initially took a quite sectarian attitude to the soviet, demanding that it adopt the party’s program or dissolve.

- See, for example, Lenin’s 1909 article, “The Aim of the Proletariat in our Revolution,” CW Vol. 15 (1977), 360–379.

- Lenin, “The Socialist Party and Non-Party Revolutionism,” 81.

- Lenin, “Several Theses,” CW Vol. 21 (1980), 401.

- Ibid., 402.

- Ibid., 403.

- In at least one instance, Lenin presented the interval to be so short as to bring him quite close to Trotsky’s theory of permanent revolution: “From the democratic revolution we shall at once, and precisely in accordance with the measure of our strength, the strength of the class-conscious and organized proletariat, begin to pass to the socialist revolution. We stand for uninterrupted revolution. We shall not stop half-way.” Lenin, “Social-Democracy’s Attitude Toward the Peasant Movement,” CW Vol. 9 (1972), 236–37.

- D. A Longley, “The Divisions in the Bolshevik Party in March 1917,” Soviet Studies , Vol. 24, No. 1 (July, 1972), 61–76. The different positions are also well outlined, with additional information, in Tony Cliff, All Power to the Soviets , chap. 7.