- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

What Is Attachment Theory?

The Importance of Early Emotional Bonds

Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/IMG_9791-89504ab694d54b66bbd72cb84ffb860e.jpg)

- Attachment Theory

- Stages of Attachment

Attachment Styles

Attachment theory focuses on relationships and bonds (particularly long-term) between people, including those between a parent and child and between romantic partners. It is a psychological explanation for the emotional bonds and relationships between people.

This theory suggests that people are born with a need to forge bonds with caregivers as children. These early bonds may continue to have an influence on attachments throughout life.

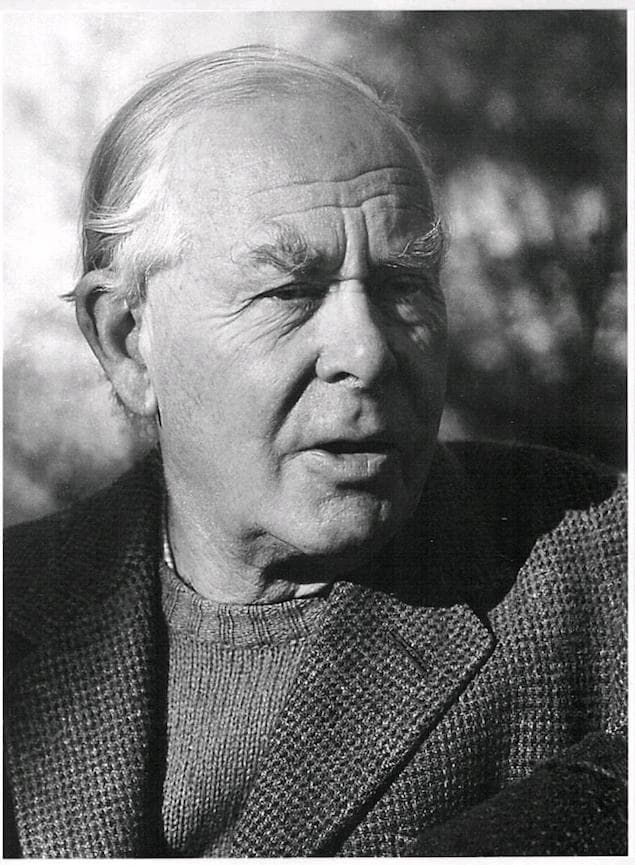

History of the Attachment Theory

British psychologist John Bowlby was the first attachment theorist. He described attachment as a "lasting psychological connectedness between human beings." Bowlby was interested in understanding the anxiety and distress that children experience when separated from their primary caregivers.

Thinkers like Freud suggested that infants become attached to the source of pleasure. Infants, who are in the oral stage of development, become attached to their mothers because she fulfills their oral needs.

Some of the earliest behavioral theories suggested that attachment was simply a learned behavior. These theories proposed that attachment was merely the result of the feeding relationship between the child and the caregiver. Because the caregiver feeds the child and provides nourishment, the child becomes attached.

Bowlby observed that feedings did not diminish separation anxiety. Instead, he found that attachment was characterized by clear behavioral and motivation patterns. When children are frightened, they seek proximity from their primary caregiver in order to receive both comfort and care.

Understanding Attachment

Attachment is an emotional bond with another person. Bowlby believed that the earliest bonds formed by children with their caregivers have a tremendous impact that continues throughout life. He suggested that attachment also serves to keep the infant close to the mother, thus improving the child's chances of survival.

Bowlby viewed attachment as a product of evolutionary processes. While the behavioral theories of attachment suggested that attachment was a learned process, Bowlby and others proposed that children are born with an innate drive to form attachments with caregivers.

Throughout history, children who maintained proximity to an attachment figure were more likely to receive comfort and protection, and therefore more likely to survive to adulthood. Through the process of natural selection, a motivational system designed to regulate attachment emerged.

The central theme of attachment theory is that primary caregivers who are available and responsive to an infant's needs allow the child to develop a sense of security. The infant learns that the caregiver is dependable, which creates a secure base for the child to then explore the world.

So what determines successful attachment? Behaviorists suggest that it was food that led to forming this attachment behavior, but Bowlby and others demonstrated that nurturance and responsiveness were the primary determinants of attachment.

Ainsworth's "Strange Situation"

In her research in the 1970s, psychologist Mary Ainsworth expanded greatly upon Bowlby's original work. Her groundbreaking "strange situation" study revealed the profound effects of attachment on behavior. In the study, researchers observed children between the ages of 12 and 18 months as they responded to a situation in which they were briefly left alone and then reunited with their mothers.

Based on the responses the researchers observed, Ainsworth described three major styles of attachment: secure attachment, ambivalent-insecure attachment, and avoidant-insecure attachment. Later, researchers Main and Solomon (1986) added a fourth attachment style called disorganized-insecure attachment based on their own research.

A number of studies since that time have supported Ainsworth's attachment styles and have indicated that attachment styles also have an impact on behaviors later in life.

Maternal Deprivation Studies

Harry Harlow's infamous studies on maternal deprivation and social isolation during the 1950s and 1960s also explored early bonds. In a series of experiments, Harlow demonstrated how such bonds emerge and the powerful impact they have on behavior and functioning.

In one version of his experiment, newborn rhesus monkeys were separated from their birth mothers and reared by surrogate mothers. The infant monkeys were placed in cages with two wire-monkey mothers. One of the wire monkeys held a bottle from which the infant monkey could obtain nourishment, while the other wire monkey was covered with a soft terry cloth.

While the infant monkeys would go to the wire mother to obtain food, they spent most of their days with the soft cloth mother. When frightened, the baby monkeys would turn to their cloth-covered mother for comfort and security.

Harlow's work also demonstrated that early attachments were the result of receiving comfort and care from a caregiver rather than simply the result of being fed.

The Stages of Attachment

Researchers Rudolph Schaffer and Peggy Emerson analyzed the number of attachment relationships that infants form in a longitudinal study with 60 infants. The infants were observed every four weeks during the first year of life, and then once again at 18 months.

Based on their observations, Schaffer and Emerson outlined four distinct phases of attachment, including:

Pre-Attachment Stage

From birth to 3 months, infants do not show any particular attachment to a specific caregiver. The infant's signals, such as crying and fussing, naturally attract the attention of the caregiver and the baby's positive responses encourage the caregiver to remain close.

Indiscriminate Attachment

Between 6 weeks of age to 7 months, infants begin to show preferences for primary and secondary caregivers. Infants develop trust that the caregiver will respond to their needs. While they still accept care from others, infants start distinguishing between familiar and unfamiliar people, responding more positively to the primary caregiver.

Discriminate Attachment

At this point, from about 7 to 11 months of age, infants show a strong attachment and preference for one specific individual. They will protest when separated from the primary attachment figure (separation anxiety), and begin to display anxiety around strangers (stranger anxiety).

Multiple Attachments

After approximately 9 months of age, children begin to form strong emotional bonds with other caregivers beyond the primary attachment figure. This often includes a second parent, older siblings, and grandparents.

Factors That Influence Attachment

While this process may seem straightforward, there are some factors that can influence how and when attachments develop, including:

- Opportunity for attachment : Children who do not have a primary care figure, such as those raised in orphanages, may fail to develop the sense of trust needed to form an attachment.

- Quality caregiving : When caregivers respond quickly and consistently, children learn that they can depend on the people who are responsible for their care, which is the essential foundation for attachment. This is a vital factor.

There are four patterns of attachment, including:

- Ambivalent attachment : These children become very distressed when a parent leaves. Ambivalent attachment style is considered uncommon, affecting an estimated 7% to 15% of U.S. children. As a result of poor parental availability, these children cannot depend on their primary caregiver to be there when they need them.

- Avoidant attachment : Children with an avoidant attachment tend to avoid parents or caregivers, showing no preference between a caregiver and a complete stranger. This attachment style might be a result of abusive or neglectful caregivers. Children who are punished for relying on a caregiver will learn to avoid seeking help in the future.

- Disorganized attachment : These children display a confusing mix of behavior, seeming disoriented, dazed, or confused. They may avoid or resist the parent. Lack of a clear attachment pattern is likely linked to inconsistent caregiver behavior. In such cases, parents may serve as both a source of comfort and fear, leading to disorganized behavior.

- Secure attachment : Children who can depend on their caregivers show distress when separated and joy when reunited. Although the child may be upset, they feel assured that the caregiver will return. When frightened, securely attached children are comfortable seeking reassurance from caregivers. This is the most common attachment style.

The Lasting Impact of Early Attachment

Children who are securely attached as infants tend to develop stronger self-esteem and better self-reliance as they grow older. These children also tend to be more independent, perform better in school, have successful social relationships, and experience less depression and anxiety.

Research suggests that failure to form secure attachments early in life can have a negative impact on behavior in later childhood and throughout life.

Children diagnosed with oppositional defiant disorder (ODD), conduct disorder (CD), or post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) frequently display attachment problems, possibly due to early abuse, neglect, or trauma. Children adopted after the age of 6 months may have a higher risk of attachment problems.

Attachment Disorders

In some cases, children may also develop attachment disorders. There are two attachment disorders that may occur: reactive attachment disorder (RAD) and disinhibited social engagement disorder (DSED).

- Reactive attachment disorder occurs when children do not form healthy bonds with caregivers. This is often the result of early childhood neglect or abuse and results in problems with emotional management and patterns of withdrawal from caregivers.

- Disinhibited social engagement disorder affects a child's ability to form bonds with others and often results from trauma, abandonment, abuse, or neglect. It is characterized by a lack of inhibition around strangers, often leading to excessively familiar behaviors around people they don't know and a lack of social boundaries.

Adult Attachments

Although attachment styles displayed in adulthood are not necessarily the same as those seen in infancy, early attachments can have a serious impact on later relationships. Adults who were securely attached in childhood tend to have good self-esteem, strong romantic relationships, and the ability to self-disclose to others.

A Word From Verywell

Our understanding of attachment theory is heavily influenced by the early work of researchers such as John Bowlby and Mary Ainsworth. Today, researchers recognize that the early relationships children have with their caregivers play a critical role in healthy development.

Such bonds can also have an influence on romantic relationships in adulthood. Understanding your attachment style may help you look for ways to become more secure in your relationships.

Bowlby J. Attachment and Loss . Basic Books.

Bowlby J. Attachment and loss: Retrospect and prospect . Am J Orthopsychiatry . 1982;52(4):664-678. doi:10.1111/j.1939-0025.1982.tb01456.x

Draper P, Belsky J. Personality development in the evolutionary perspective . J Pers. 1990;58(1):141-61. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6494.1990.tb00911.x

Ainsworth MD, Bell SM. Attachment, exploration, and separation: Illustrated by the behavior of one-year-olds in a strange situation . Child Dev . 1970;41(1):49-67. doi:10.2307/1127388

Main M, Solomon J. Discovery of a new, insecure-disorganized/disoriented attachment pattern. In: Brazelton TB, Yogman M, eds., Affective Development in Infancy. Ablex.

Harlow HF. The nature of love . American Psychologist. 1958;13(12):673-685. doi:10.1037/h0047884

Schaffer HR, Emerson PE. The development of social attachments in infancy . Monogr Soc Res Child Dev. 1964;29:1-77. doi:10.2307/1165727

Lyons-Ruth K. Attachment relationships among children with aggressive behavior problems: The role of disorganized early attachment patterns . J Consult Clin Psychol. 1996;64(1):64-73. doi:https:10.1037/0022-006X.64.1.64

Young ES, Simpson JA, Griskevicius V, Huelsnitz CO, Fleck C. Childhood attachment and adult personality: A life history perspective . Self and Identity . 2019;18:1:22-38. doi:10.1080/15298868.2017.1353540

Ainsworth MDS, Blehar MC, Waters E, Wall S. Patterns of Attachment: A Psychological Study of the Strange Situation . Erlbaum.

Ainsworth MDS. Attachments and other affectional bonds across the life cycle. In: Attachment Across the Life Cycle . Parkes CM, Stevenson-Hinde J, Marris P, eds. Routledge.

Bowlby J. The nature of the child's tie to his mother . Int J Psychoanal . 1958;39:350-371.

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

What is Attachment Theory? Bowlby’s 4 Stages Explained

No matter what the “it” refers to, Sigmund Freud would have probably said yes to that question.

However, we now know a lot more about psychology, parenting, and human relationships than Freud did.

It’s clear now that not every issue can be traced back to one’s mother. After all, there is another person involved in the raising (or at least the creation) of a child.

In addition, there are many other important people in a child’s life who influence him or her. There are siblings, grandparents, aunts and uncles, godparents, close family friends, nannies, daycare workers, teachers, peers, and others who interact with a child on a regular basis.

The question posed above is tongue-in-cheek, but it touches upon an important discussion in psychology—what influences children to turn out the way they do? What affects their ability to form meaningful, satisfying relationships with those around them?

What factors contribute to their experiences of anxiety, avoidance, and fulfillment when it comes to relationships?

Although psychologists can pretty conclusively say that it’s not entirely the mother’s fault or even the fault of both parents, we know that a child’s early experiences with their parents have a profound impact on their relationship skills as adults.

Much of the knowledge we have on this subject today comes from a concept developed in the 1950s called attachment theory . This theory will be the focus of this article: We’ll explore what it is, how it describes and explains behavior, and what its applications are in the real world.

Before you continue, we thought you might like to download our three Positive Relationships Exercises for free . These detailed, science-based exercises will help you or your clients build healthy, life-enriching relationships.

This Article Contains:

What is attachment theory a definition, research and studies, erik erikson, attachment theory in babies, infants, and early childhood development, attachment theory in adults: close relationships, parenting, love, and divorce, attachment theory in grief and trauma, the attachment theory test, using attachment theory in the classroom (worksheet and pdf), attachment theory in social work, criticisms of attachment theory, recommended books, articles, and essays, a take-home message.

The psychological theory of attachment was first described by John Bowlby, a psychoanalyst who researched the effects of separation between infants and their parents (Fraley, 2010).

Bowlby hypothesized that the extreme behaviors infants engage in to avoid separation from a parent or when reconnecting with a physically separated parent—like crying, screaming, and clinging—were evolutionary mechanisms. Bowlby thought these behaviors had possibly been reinforced through natural selection and enhanced the child’s chances of survival.

These attachment behaviors are instinctive responses to the perceived threat of losing the survival advantages that accompany being cared for and attended to by the primary caregiver(s). Since the infants who engaged in these behaviors were more likely to survive, the instincts were naturally selected and reinforced over generations.

These behaviors make up what Bowlby termed an “attachment behavioral system,” the system that guides us in our patterns and habits of forming and maintaining relationships (Fraley, 2010).

Research on Bowlby’s theory of attachment showed that infants placed in an unfamiliar situation and separated from their parents will generally react in one of these ways upon reunion with the parents:

- Secure attachment: These infants showed distress upon separation but sought comfort and were easily comforted when the parents returned;

- Anxious-resistant attachment: A smaller portion of infants experienced greater levels of distress and, upon reuniting with the parents, seemed both to seek comfort and to attempt to “punish” the parents for leaving.

- Avoidant attachment: Infants in the third category showed no stress or minimal stress upon separation from the parents and either ignored the parents upon reuniting or actively avoided the parents (Fraley, 2010).

- In later years, researchers added a fourth attachment style to this list: the disorganized-disoriented attachment style, which refers to children who have no predictable pattern of attachment behaviors (Kennedy & Kennedy, 2004).

It makes intuitive sense that a child’s attachment style is largely a function of the caregiving the child receives in his or her early years. Those who received support and love from their caregivers are likely to be secure, while those who experienced inconsistency or negligence from their caregivers are likely to feel more anxiety surrounding their relationship with their parents.

However, attachment theory takes it one step further, applying what we know about attachment in children to relationships we engage in as adults. These relationships (particularly intimate and/or romantic relationships) are also directly related to our attachment styles as children and the care we received from our primary caregivers (Firestone, 2013).

The development of this theory gives us an interesting look into the study of child development.

Bowlby and Ainsworth: The History and Psychology of Attachment Theory

Bowlby’s interest in child development traces back to his first experiences out of college, in which he volunteered at a school for maladjusted children. According to Bowlby, two children sparked his curiosity and drive that laid the foundations of attachment theory.

There was an isolated and distant teenager who had no stable mother figure in his life and had recently been expelled from his school for stealing, and an anxious 7- or 8-year-old boy who followed Bowlby wherever he went, earning himself a reputation as Bowlby’s “shadow” (Bretherton, 1992).

Through his work with children, Bowlby developed a strong belief in the impact of family experiences on children’s emotional and behavioral wellbeing .

Early on in his career, Bowlby proposed that psychoanalysts working with children should take a holistic perspective, considering children’s living environments, families, and other experiences in addition to any behaviors exhibited by the children themselves.

This idea grew into a strategy of helping children by helping their parents, a generally effective strategy given the importance of the child’s relationships with their parents (or other caregivers).

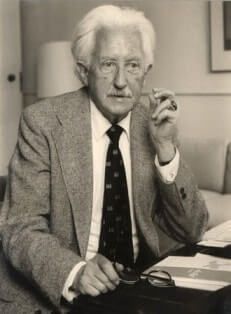

At roughly the same time Bowlby was creating the foundations for his theory on attachment, Mary Ainsworth was finishing her graduate degree and studying security theory, which proposed that children need to develop a secure dependence on their parents before venturing out into unfamiliar situations.

In 1950, the two crossed paths when Ainsworth took a position in Bowlby’s research unit at the Tavistock Clinic in London. Her initial responsibilities included analyzing records of children’s behavior, which inspired her to conduct her own studies on children in their natural settings.

Through several papers, numerous research studies, and theories that were discarded, altered, or combined, Bowlby and Ainsworth developed and provided evidence for attachment theory.

Theirs was a more rigorous explanation and description of attachment behavior than any others on the topic at the time, including those that had grown out of Freud’s work and those that were developed in direct opposition to Freud’s ideas (Bretherton, 1992).

There were several groundbreaking studies that contributed to the development of attachment theory or provided evidence for its validity, including the study described earlier in which infants were separated from their primary caregivers and their behavior was observed to fall into a “style” of attachment.

Further findings on emotional attachment came from a surprising place: rhesus monkeys.

The Harlow Experiments

His work showed that motherly love was emotional rather than physiological, that the capacity for attachment is heavily dependent upon experiences in early childhood, and that this capacity was unlikely to change much after it was “set” (Herman, 2012).

Harlow discovered these interesting findings by conducting two groundbreaking experiments.

In the first experiment, Harlow separated infant monkeys from their mothers a few hours after birth. Each monkey was instead raised by two inanimate surrogate “mothers.” Both provided the infant monkeys with the milk they needed to survive, but one was made out of wire mesh while the other was wire mesh covered with soft terry cloth.

The monkeys who were given the freedom to choose which mother to associate with almost always chose to take milk from the terry cloth “mother.” This finding showed that infant attachment is not simply a matter of where they get their milk—other factors are at play.

For his second experiment, Harlow modified his original setup. The monkeys were given either the bare wire mesh surrogate mother or the terry cloth mother, both of which provided the milk the monkeys needed to grow.

Both groups of monkeys survived and thrived physically, but they displayed extremely different behavioral tendencies. Those with a terry cloth mother returned to the surrogate when presented with strange, loud objects, while those with a wire mesh mother would throw themselves to the floor, clutch themselves, rock back and forth, or even “scream in terror.”

This provided a clear indication that emotional attachment in infancy, gained through cuddling, affected the monkey’s later responses to stress and emotion regulation (Herman, 2012).

These two experiments laid the foundations for further work on attachment in children and the impacts of attachment experiences in later life.

Erikson’s work was based on Freud’s original personality theories and drew from his idea of the ego. However, Erikson placed more importance on context from culture and society than on Freud’s focus on the conflict between the id and the superego.

In addition, his stages of development are based on how children socialize and how it affects their sense of self rather than on sexual development.

The eight stages of psychosocial development according to Erikson are:

- Infancy—Trust vs. Mistrust : In this stage, infants require a great deal of attention and comfort from their parents, leading them to develop their first sense of trust (or, in some cases, mistrust);

- Early Childhood—Autonomy vs. Shame and Doubt : Toddlers and very young children are beginning to assert their independence and develop their unique personality, making tantrums and defiance common;

- Preschool Years—Initiative vs. Guilt : Children at this stage begin learning about social roles and norms. Their imagination will take off at this point, and the defiance and tantrums of the previous stage will likely continue. The way trusted adults interact with the child will encourage him or her to act independently or to develop a sense of guilt about any inappropriate actions;

- School Age—Industry (Competence) vs. Inferiority : At this stage, the child is building important relationships with peers and is likely beginning to feel the pressure of academic performance. Mental health issues may begin at this stage, including depression, anxiety, ADHD, and other problems.

- Adolescence—Identity vs. Role Confusion : The adolescent is reaching new heights of independence and is beginning to experiment and put together his or her identity. Problems with communication and sudden emotional and physical changes are common at this stage (Wells, Sueskind, & Alcamo, 2017).

- Young Adulthood—Intimacy vs. Isolation : At this stage (ages 18-40, approximately), the individual will begin sharing with others more, including people outside o the family. If the individual is successful in this stage of development, he or she will build satisfying relationships that have a sense of commitment, safety, and care; if not, they may fear commitment and experience isolation, loneliness, and depression (McLeod, 2017).

- Middle Adulthood—Generativity vs. Stagnation : In the penultimate stage (ages 40-65, approximately), the individual is likely established in his or her career, relationship, and family. If the individual is not established and contributing to society, he or she may feel stagnant and unproductive.

- Late Adulthood—Ego Integrity vs. Despair : Finally, late adulthood (ages 65 and above) usually brings reduced productivity, which can either be embraced as a reward for one’s contributions or be met with guilt or dissatisfaction. Successfully navigating this stage will protect the individual from feeling depressed or hopeless, and help the individual cultivate wisdom (McLeod, 2017).

Although it does not map completely onto attachment theory, Erikson’s findings are clearly related to the attachment styles and behaviors Bowlby, Ainsworth, and Harlow identified.

John Bowlby – Attachment Theory – Diana Simon Psihoterapeut

According to Bowlby and Ainsworth, attachments with the primary caregiver develop during the first 18 months or so of the child’s life, starting with instinctual behaviors like crying and clinging (Kennedy & Kennedy, 2004). These behaviors are quickly directed at one or a few caregivers in particular, and by 7 or 8 months old, children usually start protesting against the caregiver(s) leaving and grieve for their absence.

Once children reach the toddler stage, they begin forming an internal working model of their attachment relationships. This internal working model provides the framework for the child’s beliefs about their own self-worth and how much they can depend on others to meet their needs.

In Bowlby and Ainsworth’s view, the attachment styles that children form based on their early interactions with caregivers form a continuum of emotion regulation, with anxious-avoidant attachment at one end and anxious-resistant at the other.

Secure attachment falls at the midpoint of this spectrum, between overly organized strategies for controlling and minimizing emotions and the uncontrolled, disorganized, and ineffectively managed emotions.

The most recently added classification, disorganized-disoriented, may display strategies and behaviors from all across the spectrum, but generally, they are not effective in controlling their emotions and may have outbursts of anger or aggression (Kennedy & Kennedy, 2004).

Research has shown that there are many behaviors in addition to emotion regulation that relates to a child’s attachment style. Among other findings, there is evidence of the following connections:

- Secure Attachment: These children are generally more likely to see others as supportive and helpful and themselves as competent and worthy of respect. They relate positively to others and display resilience, engage in complex play and are more successful in the classroom and in interactions with other children. They are better at taking the perspectives of others and have more trust in others;

- Anxious-Avoidant Attachment : Children with an anxious-avoidant attachment style are generally less effective in managing stressful situations. They are likely to withdraw and resist seeking help, which inhibits them from forming satisfying relationships with others . They show more aggression and antisocial behavior, like lying and bullying, and they tend to distance themselves from others to reduce emotional stress;

- Anxious-Resistant Attachment : These children are on the opposite end of the spectrum from anxious-avoidant children. They likely lack self-confidence and stick close to their primary caregivers. They may display exaggerated emotional reactions and keep their distance from their peers, leading to social isolation.

- Disorganized Attachment : Children with a disorganized attachment style usually fail to develop an organized strategy for coping with separation distress, and tend to display aggression, disruptive behaviors, and social isolation. They are more likely to see others as threats than sources of support, and thus may switch between social withdrawal and defensively aggressive behavior (Kennedy & Kennedy, 2004).

It is easy to see from these descriptions of behaviors and emotion regulation how attachment style in childhood can lead to relationship problems in adulthood.

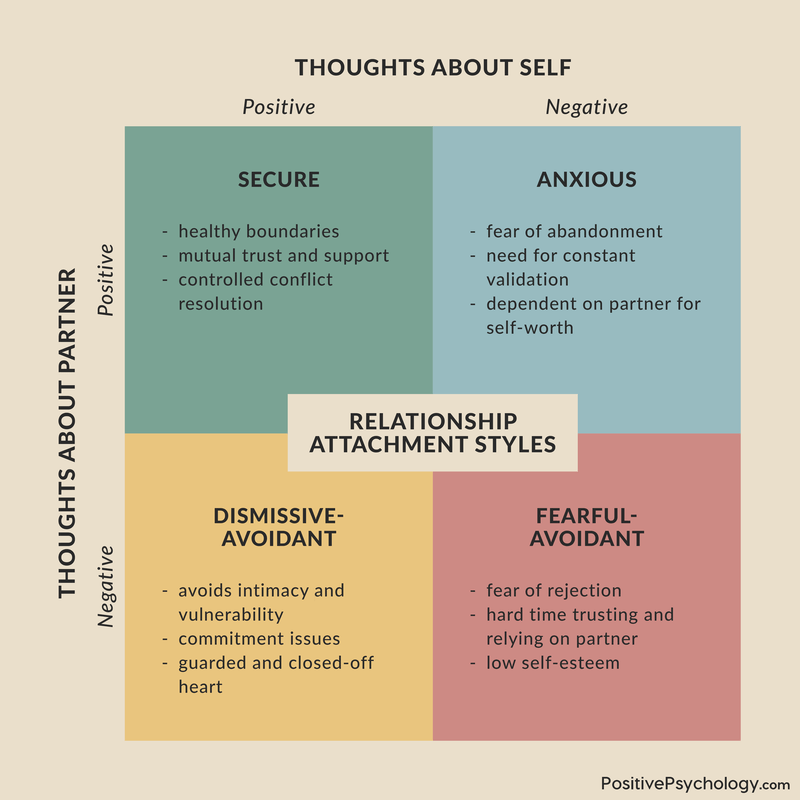

Attachment styles are primarily discussed in the context of our childhood and upbringing.

In the early stages of development, children develop different attachment patterns to their parents or caregiver. These attachment styles can be predictive of how children grow up. For example, anxious or avoidant attachment styles are often powerful predictors for psychopathology or maladjustment development in the later stages of life (Benoit, 2004).

On the contrary, children with secure attachment styles to their parents are also more likely to have secure attachments to their romantic partners. This being said, attachment styles from childhood play a significant role in all the relationships you will encounter.

From this image, you may notice that the secure attachment style is the only one with a “positive” connotation, whereas the other attachment styles seem to have more unfavorable consequences.

If you recognize yourself as displaying one of the more maladaptive attachment styles, don’t fret because this is 1. very common and 2. not set in stone. For example, if you identify with the fearful-avoidant attachment style, you may see that trust seems to be the biggest issue.

The purpose of this image is not to make you feel ashamed about having a particular attachment style, but the opposite. By accepting and embracing your weaknesses, you allow yourself to grow.

Indeed, it is clear how these attachment styles in childhood lead to attachment types in adulthood. Below is an explanation of the four attachment types in adult relationships.

Examples: The Types, Styles, and Stages (Secure, Avoidant, Ambivalent, and Disorganized)

The adult attachment styles follow the same general pattern described above (Firestone, 2013):

Secure Attachment

These adults are more likely to be satisfied with their relationships, feeling secure and connected to their partners without feeling the need to be together all the time. Their relationships are likely to feature honesty , support, independence, and deep emotional connections.

Dismissive-Avoidant (or Anxious-Avoidant) Attachment

One of the two types of adult avoidant attachments, people with this attachment style generally keep their distance from others. They may feel that they don’t need human connection to survive or thrive, and insist on maintaining their independence and isolation from others.

These individuals are often able to “shut down” emotionally when a potentially hurtful scenario arises, such as a serious argument with their partner or a threat to the continuance of their relationship.

Anxious-Preoccupied (or Anxious-Resistant) Attachment

Those who form less secure bonds with their partners may feel desperate for love or affection and feel that their partner must “complete” them or fix their problems.

While they long for safety and security in their romantic relationships, they may also be acting in ways that push their partner away rather than invite them in. The behavioral manifestations of their fears can include being clingy, demanding, jealous, or easily upset by small issues.

Fearful-Avoidant (or Disorganized) Attachment:

The second type of adult avoidant attachment manifests as ambivalence rather than isolation. People with this attachment style generally try to avoid their feelings because it is easy to get overwhelmed by them. They may suffer from unpredictable or abrupt mood swings and fear getting hurt by a romantic partner.

These individuals are simultaneously drawn to a partner or potential partner and fearful of getting to close. Unsurprisingly, this style makes it difficult to form and maintain meaningful, healthy relationships with others.

Each of these styles should be thought of as a continuum of attachment behaviors, rather than a specific “type” of person. Someone with a generally secure attachment style may on occasion display behaviors more suited to the other types, or someone with a dismissive-avoidant style may form a secure bond with a particular person.

Therefore, these “types” should be considered a way to describe and understand an individual’s behavior rather than an exact description of someone’s personality.

Based on a person’s attachment style, the way he or she approaches intimate relationships, marriage, and parenting can vary widely.

The number of ways in which this theory can be applied or used to explain behavior is compounded and expanded by the fact that relationships require two (or more) people; any attachment behaviors that an individual displays will impact and be influenced by the attachment behaviors of other people.

Given the huge variety of individuals, behaviors, and relationships, it is not surprising that there is so much conflict and confusion.

It is also not surprising, although no less unfortunate, that many relationships end up in divorce or dissolution, an event that may continue an unhealthy cycle of attachment in the children of these unions.

Download 3 Free Positive Relationships Exercises (PDF)

These detailed, science-based exercises will equip you or your clients to build healthy, life-enriching relationships.

Download 3 Positive Relationships Pack (PDF)

By filling out your name and email address below.

- Email Address *

- Your Expertise * Your expertise Therapy Coaching Education Counseling Business Healthcare Other

- Name This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

Speaking of unfortunate situations, attachment theory also has applications in the understanding of the grief and trauma associated with loss.

Although you may be most familiar with Kübler-Ross’s Five Stages of Grief, they were preceded by Bowlby’s Four Stages. During Bowlby’s work on attachment, he and his colleague Colin Murray Parkes noticed four stages of grief:

- Shock and Numbness: In this initial phase, the bereaved may feel that the loss is not real, or that it is simply impossible to accept. He or she may experience physical distress and will be unable to understand and communicate his or her emotions.

- Yearning and Searching: In this phase, the bereaved is very aware of the void in his or her life and may try to fill that void with something or someone else. He or she still identifies strongly and may be preoccupied with the deceased.

- Despair and Disorganization: The bereaved now accepts that things have changed and cannot go back to the way they were before. He or she may also experience despair, hopelessness, and anger, as well as questioning and an intense focus on making sense of the situation. He or she might withdraw from others in this phase.

- Reorganization and Recovery: In the final phase, the bereaved person’s faith in life may start to come back. He or she will start to rebuild and establish new goals, new patterns, and new habits in life. The bereaved will begin to trust again, and grief will recede to the back of his or her mind instead of staying front and center (Williams & Haley, 2017).

Of course, one’s attachment style will influence how grief is experienced as well. For example, someone who is secure may move through the stages fairly quickly or skip some altogether, while someone who is anxious or avoidant may get stuck on one of the stages.

We all experience grief differently, but viewing these experiences through the lens of attachment theory can bring new perspective and insight into our unique grieving processes and why some of us get “stuck” after a loss.

If you’re interested in learning about your attachment style, there are many tests, scales, and questionnaires out available for you to take.

Feeny, Noller, and Hanrahan developed the Original Attachment Three-Category Measure in 1987 to test respondents’ adult attachment style. It contains only three items and is very simple, but it can still give you a good idea of which category you fall into: avoidant, anxious/ambivalent, or secure. You can complete the measure yourself or read more about it on page 3 of this PDF .

Bartholomew and Horowitz’s Relationships Questionnaire added to The Three-Category Measure by expanding it to include the dismissive-avoidant category. You can find it on the same PDF as the Three-Category Measure, starting on page 3.

Fraley, Waller, and Brennan’s Experiences in Close Relationships Questionnaire-Revised (ECR-R) is a 32-item questionnaire that gives results measured by two subscales related to attachment: avoidance and anxiety (Fraley, Waller, & Brennan, 2000). Items are rated on a scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). You can find this questionnaire on the final three pages of the PDF mentioned above.

In addition to these scales, there are several less rigorous attachment style tests that can help you learn about your own style of connecting with others. These aren’t instruments often used in empirical research, but they can be helpful tools for learning more about yourself and your attachment style.

Diane Poole Heller developed an Attachment Styles Test, which contains 45 items rated on a three-point scale from “Rarely/Never” to “Usually/Often.” You can find it here , although after completing it you must enter an email to receive your results.

The Relationship Attachment Style Test is a 50-item test hosted on Psychology Today’s website. It covers the four attachment types noted earlier (Secure, Anxious-Ambivalent, Dismissive-Avoidant, Fearful-Avoidant) as well as Dependent and Codependent attachment styles .

If you are interested in taking this test, you can find it at this link . However, be aware that while you receive a free “snapshot report” at the end, you will need to pay to see your full results.

One of the ways in which the principles and concepts of attachment theory have been effectively applied to teaching is the practice of emotion coaching.

Emotion coaching is about helping children to become aware of their emotions and to manage their own feelings particularly during instances of ‘misbehavior.’ It enables practitioners to create an ethos of positive learning behavior and to have the confidence to de-escalate situations when behavior is challenging” (National College for Teaching and Leadership, 2014).

Emotion coaching is more about supporting children in learning about and regulating their own emotions and behavior than it is about “coaching” in the traditional sense. In emotion coaching, teachers are not required—or even encouraged—to promote proper behavior through rewards or punishments.

Instead, emotion coaching involves:

- Teaching students about the world of “in the moment” emotion;

- Showing students strategies for dealing with emotional ups and downs;

- Empathizing with and accepting negative or unpleasant emotions as normal, but not accepting negative behavior;

- Using moments of challenging behavior as opportunities for teaching;

- Building trusting and respectful relationships with the students (National College for Teaching and Leadership, 2014).

According to attachment theory expert Dr. John Gottman, there are five steps to emotion coaching, and they can be practiced by parents, teachers, or any significant adult in a child’s life:

- Tune in: Notice or become aware of your own and the child’s emotions. Make sure you are calm enough to practice emotion coaching, otherwise, you might want to give both of you a quick breather;

- Connect: Use this situation as an opportunity for you to practice and for the child to learn. State objectively (This is important!) what emotions you think the child is experiencing to help them connect their emotions to their behavior;

- Accept and Listen: Practice empathy. Put yourself in the child’s shoes, think about a situation when you felt a similar emotion, and try to remember what it felt like;

- Reflect: Once everyone is calm, go back over what the child said or did, mentioning only what you saw, heard, or understand of the situation. Reflect on what happened and why it happened;

- End with Problem Solving/Choices/Setting Limits: Whenever possible, try to end the situation by guiding or involving the child in problem-solving (Somerset Children & Young People, n.d.).

To learn more about emotion coaching and improve your skills as a parent or teacher, try the following activity.

What Would an Emotion Coach Do?

This short, two-page activity from the Somerset Emotion Coaching Project can help you enhance your understanding of what emotion coaching is—and what it is not.

There are five scenarios presented along with six potential responses. Your task is to read the scenario and decide which response(s) is/are the appropriate emotion coaching response(s).

The first scenario is: “Angry pupil over not wanting to attend a compulsory revision session.”

Your options include:

- Get cross with the pupil for the bad behavior;

- Tell the pupil they will have to complete an extra session due to the bad behavior;

- Help the pupil to think about what they can do about the problem;

- Tell the pupil not to make a big deal about staying after school;

- Validate the pupil’s expression of anger and frustration;

- Soothe the pupil.

This is an excellent activity to do in groups, as you can discuss each option with others and hear different perspectives from your own. In addition to identifying the emotion coaching response(s), you can also discuss which options are dismissive, avoidant, etc.

You can see the rest of the scenarios and try your hand at this activity by clicking here (an automatic download will start when you click on the link).

Emotion Coaching Scripts

Another great resource from the Somerset Emotion Coaching Project, this activity gives you a chance to practice brainstorming emotion coaching-appropriate responses.

As an added bonus, you can use the scripts you develop to guide you the next time you encounter a situation like those described.

There are six scenarios which you are instructed to create a script for:

- A pupil arrives late to class. She refuses to communicate with you and says “Don’t even start, just leave me alone”;

- A young person refuses to sit by her usual friends at a youth center and says that they have been saying unkind comments about her size;

- A boy regularly fails to complete work independently and will often sit passively and contribute little. He rarely presents with disruptive behavior but simply completes very little work. He appears isolated from his peers;

- A nursery child is crying at drop-off time and is clinging to her parent who has to go to work;

- An aggressive, confrontational parent is annoyed because she’s been asked to come in and talk about her son’s behavior. She approaches you and starts the conversation by saying, “You’re always having a go at us”;

- During recess, a group of young boys was fighting and one of them was hurt (not seriously). You approach them and they all look at you with worried expressions.

For each scenario, the instructions encourage you to:

- Recognize the emotion the child is displaying;

- Validate that emotion;

- Label the emotion the child is feeling;

- Empathize with the child;

- Set limits, if appropriate, and problem-solve.

Completing this worksheet provides you with an excellent opportunity to think, plan, and prepare for effective emotion coaching. You can download this activity for your own use here (an automatic download will start when you click on the link).

If you’re interested in learning more about applying attachment theory to teaching, check out Louis Cozolino’s book Attachment-Based Teaching: Creating a Tribal Classroom . He puts forth a simple but potentially game-changing idea: Relationships are the key to better performance rather than rigidly structured curricula.

In addition, our article Attachment Styles in Therapy: Worksheets & Handouts provides useful worksheets pertaining attachment styles.

Emotion coaching can also be used by social workers, to some extent. However, the application of attachment theory to social work is more significant in the three key messages that it espouses:

- It is vital for social workers to offer children and families a safe haven and secure base. This does not mean families should be forever comfortable and come to depend on the social worker, but families should know a social worker can provide a safe place when they are struggling as well as support for moving forward and outward;

- Social workers must be aware of children’s (and their families’) inner experiences and practice mentalization , or “bringing the inside out.” One of the most important factors in finding healing and improving family relations is to ensure that parents have an idea of what is going on in their children’s heads, including how they feel and think about their parents;

- Among the most effective tools in a social worker’s toolbox is the practice of recording parents as they interact with their child and using the videos to coach the parent. Valuable insights can be found in watching oneself parenting, and the social worker can provide in the moment coaching, offering praise for the parents’ strengths alongside suggestions for improvement (Shemmings, 2015).

Of course, there are many ways to apply attachment theory to working with children, especially those who are in the midst of family crises. However, if these three points are attended to, you’ll have the most important bases covered.

For social workers who work with adults, there are some different strategies and key points to keep in mind, specifically:

- Remember that attachment theory applies throughout the entire range of life, and many behaviors and processes are shaped by early attachment, including staying safe, seeking comfort, regulating proximity to the attachment figure, and seeking predictability;

- Keep in mind that attachment patterns are not based on a few key moments, but on thousands of moments throughout early life, and how an attachment figure responds (or does not respond) sets a template for the child’s attachment style in the future. This template affects how the child recognizes and responds to their own emotions and how they interact with attachment figures;

- This early template becomes deeply embedded in the brain and therefore has a significant impact on our ability to regulate our emotions and connect and relate to others in adulthood. This can lead an adult who was abused in childhood to fail to recognize that they are being abused in their intimate relationship, or even cause them to find comfort and stability in the predictability of their situation;

- Remember that attachment behaviors are adaptive to the context in which they were formed. Habits and behaviors that are adaptive in childhood, in an evolutionary sense at least, may become maladaptive and harmful in adulthood;

- Finally, social workers should never think that they are “treating” a set of behaviors and must recognize that the individual’s strategies were formed for a reason and likely helped him or her survive a difficult situation in childhood. The role of a social worker is to help clients avoid overapplying those strategies and to guide them in adding effective, new strategies to their toolboxes (Hardy, 2016).

As with any popular theory in psychology, there are several criticisms that have been raised against it.

Chief among them are the following criticisms:

- Overemphasis on Nurture: This criticism stems from psychologist J. R. Harris, who believes that parents do not have as much of an influence over their child’s personality or character as most people believe. She notes that much of one’s personality is determined by genetics rather than environment (Harris, 1998; Lee, 2003).

- The stressful situation criticism of attachment theory’s limitations notes that the model was based on a child’s reactions in momentary, stressful situations (being separated from one’s parent), and does not provide any insight into how children and parents interact in non-stressful situations;

- Further, the early model did not take into consideration the fact that children can have different kinds of attachments to different people; the attachment with the mother may not represent the attachments formed with others;

- Finally, the mother was viewed as the automatic primary attachment figure in the early model, when the father, stepparent, sibling, grandparent, aunt, or uncle may be the person that the child connects most strongly with (Field, 1996; Lee, 2003).

Although some of these criticisms have faded over time as the theory is injected with new evidence and updated concepts, it is useful to look at any theory with a critical eye.

17 Exercises for Positive, Fulfilling Relationships

Empower others with the skills to cultivate fulfilling, rewarding relationships and enhance their social wellbeing with these 17 Positive Relationships Exercises [PDF].

Created by experts. 100% Science-based.

A few of the most popular books on attachment theory can be found below:

- Attached: The New Science of Adult Attachment and How It Can Help You Find—and Keep—Love by Amir Levine and Rachel Heller ( Amazon );

- Attachment in Psychotherapy by David J. Wallin ( Amazon );

- Handbook of Attachment: Theory, Research, and Clinical Applications (3rd Edition) by Jude Cassidy and Phillip R. Shaver ( Amazon );

- Theories of Attachment: An Introduction to Bowlby, Ainsworth, Gerber, Brazelton, Kennell, & Klaus by Carol Garhart Mooney ( Amazon );

- Insecure in Love: How Anxious Attachment Can Make You Feel Jealous, Needy, and Worried and What You Can Do About It by Leslie Becker-Phelps ( Amazon );

- Wired for Love: How Understanding Your Partner’s Brain and Attachment Style Can Help You Defuse Conflict and Build a Secure Relationship by Dr. Stan Tatkin ( Amazon ).

There are also several great websites that host insightful essays and informative articles about attachment theory and its applications, including:

- www.communitycare.co.uk : The Community Care website calls itself “The heart of your social care career” and offers many interesting pieces on social work, attachment theory, and working with children and families who are struggling.

- “Attachment Theory” by Saul McLeod: This article provides an excellent, brief introduction to attachment theory, as well as information on the Harlow experiments, the stages of attachment, and Lorenz’s imprinting theory.

- “A Brief Overview of Adult Attachment Theory and Research” by R. Chris Fraley: This piece from attachment theory expert R. Chris Fraley also gives readers a thorough and academic introduction to familiarize them with the theory.

- “Attachment Styles at Work: Measurement, Collegial Relationships, and Burnout” by Michael P. Leiter, Arla Day, and Lisa Price: This article , published in the journal Burnout Research in 2015, dives into the applications of attachment theory in the workplace, a subject we didn’t explore in this piece. The authors share some interesting insights about how one’s attachment style affects their relationships and performance in the workplace.

This piece tackled attachment theory, a theory developed by John Bowlby in the 1950s and expanded upon by Mary Ainsworth and countless other researchers in later years. The theory helps explain how our childhood relationships with our caregivers can have a profound impact on our relationships with others as adults.

Although attachment theory may not be able to explain every peculiarity of personality, it lays the foundations for a solid understanding of yourself and those around you when it comes to connecting and interacting with others.

What do you think about attachment theory? Do you think there are attachment styles not covered by the four categories? Are there any other criticisms of attachment theory you think are valid and worthy of discussion? We’d love to hear your thoughts in the comment section.

We hope you enjoyed reading this article. Don’t forget to download our three Positive Relationships Exercises for free .

- Benoit, D. (2004). Infant-parent attachment: Definition, types, antecedents, measurement and outcome. Paediatrics & Child Health, 9(8) , 541-545.

- Bretherton, I. (1992). The origins of Attachment Theory: John Bowlby and Mary Ainsworth. Developmental Psychology, 28, 759-775.

- Cherry, K. (2018). The story of Bowlby, Ainsworth, and Attachment Theory: The importance of early emotional bonds. Retrieved from https://www.verywellmind.com/what-is-attachment-theory-2795337

- Field, T. (1996). Attachment and separation in young children. Annual Review of Psychology, 47 , 541-561.

- Firestone, L. (2013). How your attachment style impacts your relationship. Retrieved from https://www.psychologytoday.com/blog/compassion-matters/201307/how-your-attachment-style-impacts-your-relationship

- Fraley, R. C. (2010). A brief overview of adult attachment theory and research. Retrieved from https://internal.psychology.illinois.edu/~rcfraley/attachment.htm

- Hardy, R. (2016). Tips on applying attachment theory in social work with adults. Retrieved from http://www.communitycare.co.uk/2016/12/06/attachment-theory-social-work-adults/

- Harris, J. R. (1998). The nurture assumption: Why our children turn out the way they do. Free Press.

- Herman, E. (2012). Harry F. Harlow, monkey love experiments. Retrieved from http://pages.uoregon.edu/adoption/studies/HarlowMLE.htm

- Kennedy, J. H., & Kennedy, C. E. (2004). Attachment theory: Implications for school psychology. Psychology in the Schools, 41 , 247-259.

- Lee, E. J. (2003). The attachment system throughout the life course: Review and criticisms of attachment theory . Retrieved from http://www.personalityresearch.org/papers/lee.html

- McLeod, S. (2017). Erik Erikson. Retrieved from https://www.simplypsychology.org/Erik-Erikson.html

- National College for Teaching and Leadership (2014). An introduction to attachment and the implications for learning and behaviour [PDF Slide Presentation] . Retrieved from https://www.bathspa.ac.uk/media/bathspaacuk/education-/research/digital-literacy/education-resource-introduction-to-attatchment.pdf

- Shemmings, D. (2015). How social workers can use attachment theory in direct work. Retrieved from http://www.communitycare.co.uk/2015/09/02/using-attachment-theory-research-help-families-just-assess/

- Somerset Children & Young People Health & Wellbeing. (n.d.). Emotion coaching and self-regulation. Retrieved from http://www.cypsomersethealth.org/?ks=1&page=mhtk_secp_5

- Wells, J., Sueskind, B., & Alcamo, K. (2017). Child and adolescent issues. Retrieved from https://www.goodtherapy.org/learn-about-therapy/issues/child-and-adolescent-issues

- Williams, L., & Haley, E. (2017). Before the five stages were the FOUR stages of grief. Retrieved from https://whatsyourgrief.com/bowlby-four-stages-of-grief/

Share this article:

Article feedback

What our readers think.

muchas gracias por la información

The linked surveys are problematic, when they refer to intimate or close relationships, particularly for persons who’ve only had one close adult relationship. Or none.

Article is defective (‘to’ instead of ‘too’ aside). Cannot – for the life of me – find the four stages of attachment declared at the outset; only four styles. For what’s it’s worth I experienced paternal absence and maternal rejection – prostitute mother and pimp father – which is to say, no parenting or attachment at all – leading to a hotch-potch of all three non-secure ‘styles’.

how does attachment influences personality development in adulthood.

Good question! We answer this question by linking the different attachment styles to adult behaviors traits in this article: https://positivepsychology.com/attachment-style-worksheets/ (see the subsection ‘Attachment Theory in Psychology: 4 Types & Characteristics’)

Hope this helps!

– Nicole | Community Manager

How do I reference this article

You can reference this article in APA 7th as follows: Ackerman, C. A. (2018, April 27). What is Attachment Theory? Bowlby’s 4 stages explained. PositivePsychology.com. https://positivepsychology.com/attachment-theory/

I think that a big limitation when discussing Attachment Theory, that I haven’t seen addressed, is the effect of trauma on a older child past the early defining stage, or an adult. Bullying, accidents and injury, severe illness, family upheaval, or other significant life events can significantly affect a person’s psychological state, and thus alter a Securely Attached style to one of the other types.

Thank you for an informative article! Do you happen to know of any non-profit organizations that focus on stopping the cycle of maladaptive attachment in families? I’m a student with some ideas for a program that I’d like to pitch to some organizations that serve at risk individuals.

Glad you found the article helpful — that sounds like an interesting idea! Your question’s a little tricky. It’s hard to know how explicitly existing services draw on Bowlby’s principles. However, I suspect that the messages of the framework are likely embedded in various parent support groups and educational opportunities. If you’re interested in the U.S. specifically, maybe check out some of the services listed here and inquire about any curriculums.

Thank you, Nicole!

Let us know your thoughts Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Related articles

Can a Disorganized Attachment Style Be Overcome?

No individual needs to be defined by the actions or behavior of their parents. However, the attachment strategies we form early in our lives for [...]

Setting Boundaries: Quotes & Books for Healthy Relationships

Rather than being a “hot topic,” setting boundaries is more of a “boomerang topic” in that we keep coming back to it. This is partly [...]

14 Worksheets for Setting Healthy Boundaries

Setting healthy, unapologetic boundaries offers peace and freedom where life was previously overwhelming and chaotic. When combined with practicing assertiveness and self-discipline, boundary setting can [...]

Read other articles by their category

- Body & Brain (49)

- Coaching & Application (58)

- Compassion (25)

- Counseling (51)

- Emotional Intelligence (23)

- Gratitude (18)

- Grief & Bereavement (21)

- Happiness & SWB (40)

- Meaning & Values (26)

- Meditation (20)

- Mindfulness (44)

- Motivation & Goals (45)

- Optimism & Mindset (34)

- Positive CBT (30)

- Positive Communication (20)

- Positive Education (47)

- Positive Emotions (32)

- Positive Leadership (19)

- Positive Parenting (15)

- Positive Psychology (34)

- Positive Workplace (37)

- Productivity (17)

- Relationships (43)

- Resilience & Coping (37)

- Self Awareness (21)

- Self Esteem (38)

- Strengths & Virtues (32)

- Stress & Burnout Prevention (34)

- Theory & Books (46)

- Therapy Exercises (37)

- Types of Therapy (64)

- Email This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

3 Positive Relationships Exercises Pack

- News stories

- Blog articles

- NSPCC Learning podcast

- Why language matters

- Sign up to newsletters

- Safeguarding in Education Update

- CASPAR email alert

- Key topics home

- Safeguarding and child protection

- Child abuse and neglect

- Child health and development

- Safer recruitment

- Case reviews

- Online safety

- Research and resources home

- NSPCC research

- Safeguarding resources

- How Safe conference

- Self-assessment tool

- Schools and colleges

- Training home

- Basic safeguarding courses

- Advanced training

- Elearning courses

- Designated person training

- Schools and education courses

- Services home

- Direct work: children and families

- Talk Relationships

- Consultancy

- Library and Information Service

- Support for local communities

- NSPCC Helpline

- Speak out Stay safe schools service

- My learning

- Self-assessment

- /g,'').replace(/ /g,'')" v-html="suggestion">

Attachment and child development

What is attachment theory and why is it important.

Attachment is a clinical term used to describe "a lasting psychological connectedness between human beings” (Bowlby, 1997) 1 . In particular, attachment theory highlights the importance of a child’s emotional bond with their primary caregivers. Disruption to or loss of this bond can affect a child emotionally and psychologically into adulthood, and have an impact on their future relationships.

Only specially trained and qualified professionals should assess a child’s attachment style. However, it’s important for all adults working with children to understand what attachment is and know how to help parents and carers become attuned to their child’s needs. You might do this by working with them directly, or by signposting families to other appropriate services. In the long term, this can help improve wellbeing and provide positive outcomes for both the child and their caregivers.

Understanding attachment in the early years

Children can form attachments with more than one caregiver, but the bond with the people who have provided close care from early infancy is the most important and enduring (Bowlby, 1997) 2 .

It’s important that parents and carers are attuned and responsive to their baby’s needs and are able to provide appropriate care. This includes recognising if their baby is hungry, feeling unwell or in need of closeness and affection (Howe, 2011) 3 .

Forming an attachment is something that develops over time for a child, but parents and carers can start to form an emotional bond with their child before they are born. Sometimes a parent or carer may have difficulty forming this bond, for example if they are experiencing mental health issues or don’t have an effective support network.

On this page, you’ll find information on:

- why attachment is important

- how children develop attachment

- attachment issues, insecure and secure attachment and behaviours to look out for

- how trauma can affect attachment

- how you can support parents and carers to develop a bond with their child.

Need specific information?

Our information specialists are here to help you find research, guidance and best practice.

Find out more

Stages of attachment

The first two years of a child’s life are the most critical for forming attachments (Prior and Glaser, 2006) 1 .

During this period, children develop an ‘internal working model’ that shapes the way they view relationships and operate socially. This can affect their sense of trust in others, self-worth and their confidence interacting with others (Bowlby, 1997) 2 .

When are attachments formed?

Attachments are formed in different ways during the phases of a child’s development.

Antenatal (before birth)

During the antenatal period, parents and carers can form a bond with their child. Any bonds formed before birth can have a positive impact on the relationship between babies and their caregivers once the child is born (Condon and Corkindale, 1997) 3 .

Birth until 6 weeks

This is sometimes referred to as the pre-attachment phase because the baby doesn’t appear to show an attachment to any specific caregiver. However, parents and carers who provide a nurturing environment and are responsive to their babies needs can lay the foundation for secure attachments to form (Bowlby, 1997) 4 .

6 weeks until 6-8 months

During this stage of their development, a baby might start to show a preference for their primary and secondary caregivers (often the mother and father).

6-8 months until 18 months-2 years

During this period a child begins to show a strong attachment to their primary caregivers. Babies start to develop separation anxiety during this phase and can become upset when their caregiver leaves, even for short periods (Bowlby, 1997) 5 .

18 months – 2 years onwards

At this point children are likely to become less dependent on their primary caregiver, particularly if they feel secure and confident the caregiver will return and be responsive in times of need (Bowlby, 1997) 6 .

Types of attachment

A child’s need for attachment is part of the process of seeking safety and security from their caregiver.

What does secure attachment look like?

In secure caregiver-child relationships, the caregiver is usually sensitive and tuned in to the child’s needs. They are able to provide care that is predictably loving, responsive and consistent.

Young children who have formed a secure attachment to their caregiver may display the following patterns of behaviour during times of stress or exploration:

- proximity maintenance – wanting to be near their primary caregiver

- safe haven - returning to their primary caregiver for comfort and safety if they feel afraid or threatened

- secure base – treating their primary caregiver as a base of security from which they can explore the surrounding environment. The child feels safe in the knowledge that they can return to their secure base when needed

- separation distress - experiencing anxiety in the absence of their primary caregiver. They are upset when their caregiver leaves, but happy to see them and easily comforted when they return

(Ainsworth et al, 2015) 1 .

Benefits of secure attachment

When caregivers react sensitively to ease their child’s distress and help them regulate their emotions, it has a positive impact on the child’s neurological, physiological and psychosocial development (Howe, 2011) 2 .

Children with secure attachments are more likely to develop emotional intelligence, good social skills and robust mental health (Howe, 2011) 3 .

Effects of insecure attachment

Not receiving comfort and security in the early years can have a negative effect on children’s neurological, psychological, emotional and physical development and functioning (Newman, 2015) 4 .

Babies and young children who have attachment issues may be more likely to develop behavioural problems such as attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) or conduct disorder (Fearon et al, 2010) 5 .

Children who have attachment issues can have difficulty forming healthy relationships when they grow up. This may be because their experiences have taught them to believe that other people are unreliable or untrustworthy (Bowlby, 1997) 6 .

Adults with attachment issues are at a higher risk of entering into volatile relationships and having poor parenting skills, behavioural difficulties and mental health problems (Howe, 2011) 7 .

> Find out more about how trauma affects child brain development

Further reading

Take a look at our reading list on child attachment.

> View the reading list on the NSPCC Library catalogue

Attachment issues

Factors affecting attachment.

Some circumstances can make it more challenging for a child and their caregivers to form a pattern of secure attachment. These may include:

- abuse, maltreatment and trauma experienced by the parent or child

- parental mental health difficulties

- parental substance misuse

- the child having multiple care placements

- parents being separated from their baby just after birth, for example if the baby is receiving neonatal care

- stress such as having a low income, being a single parent, or being a young parent

- bereavement or loss of another caregiver that a child had an attachment with

(Bowlby, 1989) 1 .

Signs that a child may have attachment issues

Children’s behaviour can be influenced by a wide range of circumstances and emotions.

Indicators that a baby or toddler might not have a secure attachment with their caregiver will emerge as a pattern of behaviour over time, particularly during moments of stress or exploration. This pattern might include:

- being fearful or avoidant of a parent or carer

- becoming extremely distressed when their carer leaves them, even for a short amount of time

- rejecting their caregiver’s efforts to calm, soothe, and connect with them

- not seeming to notice or care when their caregiver leaves the room or when they return

- being passive or non-responsive to their carer

- seeming to be depressed or angry

- not being interested in playing with toys or exploring their environment

(Howe, 2011) 2 .

As children with attachment issues get older, these behaviour patterns might evolve. As well as being evident during times of stress, some behaviours may start to become obvious at other times. These may include the child:

- finding it difficult to ask for help

- struggling to form positive relationships with adults and peers

- struggling to concentrate

- struggling to calm themselves down

- both demanding and rejecting attention or support at the same time

- becoming quickly or disproportionately angry or upset, at times with no clear triggers

- appearing withdrawn or disengaged from activities

- daydreaming, being hyperactive or constantly fidgeting or moving

(Mentally Healthy Schools, 2020) 3 .

If you think a child may have attachment issues, you should refer them to a suitably trained health and social care professional for a full assessment. You should follow your organisation’s procedures to make a health and social care referral, or contact your local authority children’s social care services.

Trauma and attachment

The signs of attachment issues can be similar to indicators that a child is experiencing other challenges, such as:

- mental health problems

- additional needs

- abuse and neglect .

This means it’s important to consider everything that’s going on in a child’s life and make sure they and their family are provided with appropriate support.

Think about all your previous experiences with the child and their caregivers, to help you build a clear picture of their relationships and recognise any concerning patterns of behaviour.

The impact of trauma and attachment

Children who have experienced abuse, neglect and trauma might develop coping strategies that can make it more complicated to recognise attachment issues.

For example, one sign of secure attachment is that children see their caregiver as a secure base to explore from. But children who have experienced neglect , for example, might display independent behaviour in order to protect themselves from the emotional pain of not having their needs met (Marvin et al, 2002) 1 .

It is also possible for a child to develop an attachment to someone who is maltreating them (Blizard & Bluhm, 1994) 2 .

As well as affecting attachment, experiencing trauma can have an impact on a child’s brain development. Children might need extra support to help strengthen the architecture of their brain.

What to do if you’re worried that a child is experiencing or at risk of abuse or neglect

If a child is in immediate danger, call the police on 999.

If you’re worried about a child but they are not in immediate danger, you should share your concerns.

- Follow your organisation’s child protection procedures without delay . These should provide clear guidelines on the steps you need to take if a child discloses abuse. They will state who in your organisation has responsibility for safeguarding or child protection and who you should report your concerns to.

- Contact your local child protection services . Their contact details can be found on the website for the local authority the child lives in.

- Contact the police . They will assess the situation and take the appropriate action to protect the child.

- Contact the NSPCC Helpline on 0808 800 5000 or by emailing [email protected] . Our child protection specialists will talk through your concerns with you, give you expert advice and take action to protect the child as appropriate. This may include making a referral to the local authority.

> Find out more about recognising and responding to abuse

If your organisation doesn't have a clear safeguarding procedure or you're concerned about how child protection issues are being handled in your own, or another, organisation, contact the Whistleblowing Advice Line to discuss your concerns.

> Find out about the Whistleblowing Advice Line on the NSPCC website

When you're not sure

The NSPCC Helpline can help when you’re not sure if a situation needs a safeguarding response. Our child protection specialists are here to support you whether you’re seeking advice, sharing concerns about a child, or looking for reassurance.

Whatever the need, reason or feeling, you can contact the NSPCC Helpline on 0808 800 5000 or by emailing [email protected]

Our trained professionals will talk through your concerns with you. Depending on what you share, our experts will talk you through which local services can help, advise you on next steps, or make referrals to children’s services and the police.

> Find out more about how the NSPCC Helpline can support you

Supporting children and families

Building positive relationships.

It’s important for anyone who works with children and families to support parents and carers in building positive relationships with their child. Having positive interaction and play with caregivers can help a child’s brain to develop healthily.

> See our early years resources which you can share with parents and caregivers

Video feedback programmes can also be used by specially trained social care professionals to help caregivers improve their interactions with their child. This involves caregivers being filmed when they are interacting with their child and then watching the recording with a trained practitioner, who gives them feedback and helps them build on their strengths.

Support for parents and carers

If parents are struggling with their own issues, it may make it harder for them to bond with their child and provide consistant and responsive care. They may have:

- experienced abuse of trauma themselves

- drug and/or alcohol dependencies

- mental health issues.

> Find out more about parental mental health

> Learn more about parental substance misuse

Services for children and families

The NSPCC has many services that children and families can be referred to, from supporting parents and carers in taking care of their children to preventing sexual abuse and overcoming abuse.

Our services might be suitable for children and families you are working with:

- Pregnancy in Mind helps parents who are at risk of or experiencing mild to moderate anxiety and depression during pregnancy. The service helps build parents’ capacity to provide sensitive, responsive care to their babies and keep these skills developed postnatally and as their children develop

Browse for more services

Take a look at our reading list about child attachment interventions, support and treatment.

> View the list on the NSPCC Library catalogue

Supporting children’s mental health

Children with attachment issues may have problems expressing or controlling their emotions and forming positive relationships, which might affect their mental health.

It’s important to make sure children and young people have access to mental health support.

> Find out more about child mental health

> See the NSPCC’s advice for parents and carers on how to support their child’s mental health