- Walden University

- Faculty Portal

Writing a Paper: Conclusions

Writing a conclusion.

A conclusion is an important part of the paper; it provides closure for the reader while reminding the reader of the contents and importance of the paper. It accomplishes this by stepping back from the specifics in order to view the bigger picture of the document. In other words, it is reminding the reader of the main argument. For most course papers, it is usually one paragraph that simply and succinctly restates the main ideas and arguments, pulling everything together to help clarify the thesis of the paper. A conclusion does not introduce new ideas; instead, it should clarify the intent and importance of the paper. It can also suggest possible future research on the topic.

An Easy Checklist for Writing a Conclusion

It is important to remind the reader of the thesis of the paper so he is reminded of the argument and solutions you proposed.

Think of the main points as puzzle pieces, and the conclusion is where they all fit together to create a bigger picture. The reader should walk away with the bigger picture in mind.

Make sure that the paper places its findings in the context of real social change.

Make sure the reader has a distinct sense that the paper has come to an end. It is important to not leave the reader hanging. (You don’t want her to have flip-the-page syndrome, where the reader turns the page, expecting the paper to continue. The paper should naturally come to an end.)

No new ideas should be introduced in the conclusion. It is simply a review of the material that is already present in the paper. The only new idea would be the suggesting of a direction for future research.

Conclusion Example

As addressed in my analysis of recent research, the advantages of a later starting time for high school students significantly outweigh the disadvantages. A later starting time would allow teens more time to sleep--something that is important for their physical and mental health--and ultimately improve their academic performance and behavior. The added transportation costs that result from this change can be absorbed through energy savings. The beneficial effects on the students’ academic performance and behavior validate this decision, but its effect on student motivation is still unknown. I would encourage an in-depth look at the reactions of students to such a change. This sort of study would help determine the actual effects of a later start time on the time management and sleep habits of students.

Related Webinar

Didn't find what you need? Email us at [email protected] .

- Previous Page: Thesis Statements

- Next Page: Writer's Block

- Office of Student Disability Services

Walden Resources

Departments.

- Academic Residencies

- Academic Skills

- Career Planning and Development

- Customer Care Team

- Field Experience

- Military Services

- Student Success Advising

- Writing Skills

Centers and Offices

- Center for Social Change

- Office of Academic Support and Instructional Services

- Office of Degree Acceleration

- Office of Research and Doctoral Services

- Office of Student Affairs

Student Resources

- Doctoral Writing Assessment

- Form & Style Review

- Quick Answers

- ScholarWorks

- SKIL Courses and Workshops

- Walden Bookstore

- Walden Catalog & Student Handbook

- Student Safety/Title IX

- Legal & Consumer Information

- Website Terms and Conditions

- Cookie Policy

- Accessibility

- Accreditation

- State Authorization

- Net Price Calculator

- Contact Walden

Walden University is a member of Adtalem Global Education, Inc. www.adtalem.com Walden University is certified to operate by SCHEV © 2024 Walden University LLC. All rights reserved.

In a short paper—even a research paper—you don’t need to provide an exhaustive summary as part of your conclusion. But you do need to make some kind of transition between your final body paragraph and your concluding paragraph. This may come in the form of a few sentences of summary. Or it may come in the form of a sentence that brings your readers back to your thesis or main idea and reminds your readers where you began and how far you have traveled.

So, for example, in a paper about the relationship between ADHD and rejection sensitivity, Vanessa Roser begins by introducing readers to the fact that researchers have studied the relationship between the two conditions and then provides her explanation of that relationship. Here’s her thesis: “While socialization may indeed be an important factor in RS, I argue that individuals with ADHD may also possess a neurological predisposition to RS that is exacerbated by the differing executive and emotional regulation characteristic of ADHD.”

In her final paragraph, Roser reminds us of where she started by echoing her thesis: “This literature demonstrates that, as with many other conditions, ADHD and RS share a delicately intertwined pattern of neurological similarities that is rooted in the innate biology of an individual’s mind, a connection that cannot be explained in full by the behavioral mediation hypothesis.”

Highlight the “so what”

At the beginning of your paper, you explain to your readers what’s at stake—why they should care about the argument you’re making. In your conclusion, you can bring readers back to those stakes by reminding them why your argument is important in the first place. You can also draft a few sentences that put those stakes into a new or broader context.

In the conclusion to her paper about ADHD and RS, Roser echoes the stakes she established in her introduction—that research into connections between ADHD and RS has led to contradictory results, raising questions about the “behavioral mediation hypothesis.”

She writes, “as with many other conditions, ADHD and RS share a delicately intertwined pattern of neurological similarities that is rooted in the innate biology of an individual’s mind, a connection that cannot be explained in full by the behavioral mediation hypothesis.”

Leave your readers with the “now what”

After the “what” and the “so what,” you should leave your reader with some final thoughts. If you have written a strong introduction, your readers will know why you have been arguing what you have been arguing—and why they should care. And if you’ve made a good case for your thesis, then your readers should be in a position to see things in a new way, understand new questions, or be ready for something that they weren’t ready for before they read your paper.

In her conclusion, Roser offers two “now what” statements. First, she explains that it is important to recognize that the flawed behavioral mediation hypothesis “seems to place a degree of fault on the individual. It implies that individuals with ADHD must have elicited such frequent or intense rejection by virtue of their inadequate social skills, erasing the possibility that they may simply possess a natural sensitivity to emotion.” She then highlights the broader implications for treatment of people with ADHD, noting that recognizing the actual connection between rejection sensitivity and ADHD “has profound implications for understanding how individuals with ADHD might best be treated in educational settings, by counselors, family, peers, or even society as a whole.”

To find your own “now what” for your essay’s conclusion, try asking yourself these questions:

- What can my readers now understand, see in a new light, or grapple with that they would not have understood in the same way before reading my paper? Are we a step closer to understanding a larger phenomenon or to understanding why what was at stake is so important?

- What questions can I now raise that would not have made sense at the beginning of my paper? Questions for further research? Other ways that this topic could be approached?

- Are there other applications for my research? Could my questions be asked about different data in a different context? Could I use my methods to answer a different question?

- What action should be taken in light of this argument? What action do I predict will be taken or could lead to a solution?

- What larger context might my argument be a part of?

What to avoid in your conclusion

- a complete restatement of all that you have said in your paper.

- a substantial counterargument that you do not have space to refute; you should introduce counterarguments before your conclusion.

- an apology for what you have not said. If you need to explain the scope of your paper, you should do this sooner—but don’t apologize for what you have not discussed in your paper.

- fake transitions like “in conclusion” that are followed by sentences that aren’t actually conclusions. (“In conclusion, I have now demonstrated that my thesis is correct.”)

- picture_as_pdf Conclusions

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

Margin Size

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

3.9: Conclusion to Writing Process

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 5292

- Lumen Learning

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\)

As this module emphasizes, a LOT happens behind the scenes when it comes to writing. We are used to seeing, and reading, finished works: books, course materials, online content. We aren’t often exposed to all of the preparation and elbow grease that goes into the creation of those finished works.

It helps to recognize that incredibly successful people put just as much time into those behind-the-scenes efforts as the rest of us: maybe even MORE time. Consider this video, where Jerry Seinfeld creates a single joke:

Download a transcript for this video here (.docx file) .

Did you notice that he’s been working on this joke for 2 years? Of course, some works of creative genius take longer than others. Unfortunately, deadlines are generally a lot tighter than that for most college writing.

The writing process is a tool that will help you through many large projects in your college career. You’ll customize it to fit the way you work, and find that the process will change, depending on the project, the timeline, and the needs you have at the time.

Your Best College Essay

Maybe you love to write, or maybe you don’t. Either way, there’s a chance that the thought of writing your college essay is making you sweat. No need for nerves! We’re here to give you the important details on how to make the process as anxiety-free as possible.

What's the College Essay?

When we say “The College Essay” (capitalization for emphasis – say it out loud with the capitals and you’ll know what we mean) we’re talking about the 550-650 word essay required by most colleges and universities. Prompts for this essay can be found on the college’s website, the Common Application, or the Coalition Application. We’re not talking about the many smaller supplemental essays you might need to write in order to apply to college. Not all institutions require the essay, but most colleges and universities that are at least semi-selective do.

How do I get started?

Look for the prompts on whatever application you’re using to apply to schools (almost all of the time – with a few notable exceptions – this is the Common Application). If one of them calls out to you, awesome! You can jump right in and start to brainstorm. If none of them are giving you the right vibes, don’t worry. They’re so broad that almost anything you write can fit into one of the prompts after you’re done. Working backwards like this is totally fine and can be really useful!

What if I have writer's block?

You aren’t alone. Staring at a blank Google Doc and thinking about how this is the one chance to tell an admissions officer your story can make you freeze. Thinking about some of these questions might help you find the right topic:

- What is something about you that people have pointed out as distinctive?

- If you had to pick three words to describe yourself, what would they be? What are things you’ve done that demonstrate these qualities?

- What’s something about you that has changed over your years in high school? How or why did it change?

- What’s something you like most about yourself?

- What’s something you love so much that you lose track of the rest of the world while you do it?

If you’re still stuck on a topic, ask your family members, friends, or other trusted adults: what’s something they always think about when they think about you? What’s something they think you should be proud of? They might help you find something about yourself that you wouldn’t have surfaced on your own.

How do I grab my reader's attention?

It’s no secret that admissions officers are reading dozens – and sometimes hundreds – of essays every day. That can feel like a lot of pressure to stand out. But if you try to write the most unique essay in the world, it might end up seeming forced if it’s not genuinely you. So, what’s there to do? Our advice: start your essay with a story. Tell the reader about something you’ve done, complete with sensory details, and maybe even dialogue. Then, in the second paragraph, back up and tell us why this story is important and what it tells them about you and the theme of the essay.

THE WORD LIMIT IS SO LIMITING. HOW DO I TELL A COLLEGE MY WHOLE LIFE STORY IN 650 WORDS?

Don’t! Don’t try to tell an admissions officer about everything you’ve loved and done since you were a child. Instead, pick one or two things about yourself that you’re hoping to get across and stick to those. They’ll see the rest on the activities section of your application.

I'M STUCK ON THE CONCLUSION. HELP?

If you can’t think of another way to end the essay, talk about how the qualities you’ve discussed in your essays have prepared you for college. Try to wrap up with a sentence that refers back to the story you told in your first paragraph, if you took that route.

SHOULD I PROOFREAD MY ESSAY?

YES, proofread the essay, and have a trusted adult proofread it as well. Know that any suggestions they give you are coming from a good place, but make sure they aren’t writing your essay for you or putting it into their own voice. Admissions officers want to hear the voice of you, the applicant. Before you submit your essay anywhere, our number one advice is to read it out loud to yourself. When you read out loud you’ll catch small errors you may not have noticed before, and hear sentences that aren’t quite right.

ANY OTHER ADVICE?

Be yourself. If you’re not a naturally serious person, don’t force formality. If you’re the comedian in your friend group, go ahead and be funny. But ultimately, write as your authentic (and grammatically correct) self and trust the process.

And remember, thousands of other students your age are faced with this same essay writing task, right now. You can do it!

- Original article

- Open access

- Published: 20 May 2024

The great detectives: humans versus AI detectors in catching large language model-generated medical writing

- Jae Q. J. Liu 1 ,

- Kelvin T. K. Hui 1 ,

- Fadi Al Zoubi 1 ,

- Zing Z. X. Zhou 1 ,

- Dino Samartzis 2 ,

- Curtis C. H. Yu 1 ,

- Jeremy R. Chang 1 &

- Arnold Y. L. Wong ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-5911-5756 1

International Journal for Educational Integrity volume 20 , Article number: 8 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

Metrics details

The application of artificial intelligence (AI) in academic writing has raised concerns regarding accuracy, ethics, and scientific rigour. Some AI content detectors may not accurately identify AI-generated texts, especially those that have undergone paraphrasing. Therefore, there is a pressing need for efficacious approaches or guidelines to govern AI usage in specific disciplines.

Our study aims to compare the accuracy of mainstream AI content detectors and human reviewers in detecting AI-generated rehabilitation-related articles with or without paraphrasing.

Study design

This cross-sectional study purposively chose 50 rehabilitation-related articles from four peer-reviewed journals, and then fabricated another 50 articles using ChatGPT. Specifically, ChatGPT was used to generate the introduction, discussion, and conclusion sections based on the original titles, methods, and results. Wordtune was then used to rephrase the ChatGPT-generated articles. Six common AI content detectors (Originality.ai, Turnitin, ZeroGPT, GPTZero, Content at Scale, and GPT-2 Output Detector) were employed to identify AI content for the original, ChatGPT-generated and AI-rephrased articles. Four human reviewers (two student reviewers and two professorial reviewers) were recruited to differentiate between the original articles and AI-rephrased articles, which were expected to be more difficult to detect. They were instructed to give reasons for their judgements.

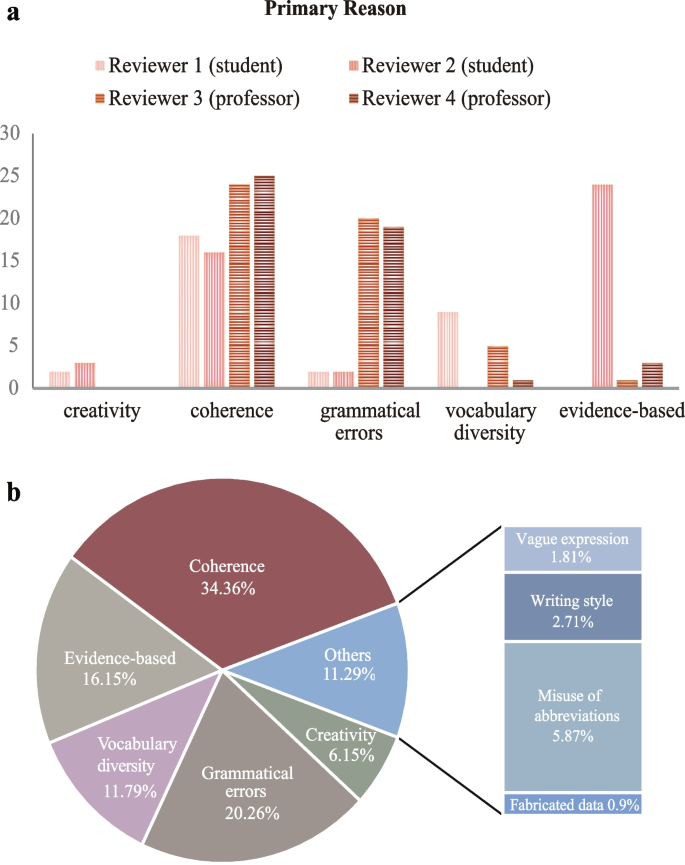

Originality.ai correctly detected 100% of ChatGPT-generated and AI-rephrased texts. ZeroGPT accurately detected 96% of ChatGPT-generated and 88% of AI-rephrased articles. The areas under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUROC) of ZeroGPT were 0.98 for identifying human-written and AI articles. Turnitin showed a 0% misclassification rate for human-written articles, although it only identified 30% of AI-rephrased articles. Professorial reviewers accurately discriminated at least 96% of AI-rephrased articles, but they misclassified 12% of human-written articles as AI-generated. On average, students only identified 76% of AI-rephrased articles. Reviewers identified AI-rephrased articles based on ‘incoherent content’ (34.36%), followed by ‘grammatical errors’ (20.26%), and ‘insufficient evidence’ (16.15%).

Conclusions and relevance

This study directly compared the accuracy of advanced AI detectors and human reviewers in detecting AI-generated medical writing after paraphrasing. Our findings demonstrate that specific detectors and experienced reviewers can accurately identify articles generated by Large Language Models, even after paraphrasing. The rationale employed by our reviewers in their assessments can inform future evaluation strategies for monitoring AI usage in medical education or publications. AI content detectors may be incorporated as an additional screening tool in the peer-review process of academic journals.

Introduction

Chat Generative Pre-trained Transformer (ChatGPT; OpenAI, USA) is a popular and responsive chatbot that has surpassed other Large Language Models (LLMs) in terms of usage (ChatGPT Statistics 2023 ). Being trained with 175 billion parameters, ChatGPT has demonstrated its capabilities in the field of medicine and digital health (OpenAI 2023 ). It has been reported to be able to solve higher-order reasoning questions in pathology (Sinha 2023 ). Currently, ChatGPT has been used in generating discharge summaries (Patel &Lam 2023 ), aiding in diagnosis (Mehnen et al. 2023 ), and providing health information to patients with cancer (Hopkins et al. 2023 ). Currently, ChatGPT has become a valuable writing assistant, especially in medical writing (Imran & Almusharaf 2023 ).

However, scientists did not support granting ChatGPT authorship in academic publishing because it could not be held accountable for the ethics of the content (Stokel-Walker 2023 ). Its tendency to generate plausible but non-rigorous or misleading content has raised doubts about the reliability of its outputs (Sallam 2023 ; Manohar & Prasad 2023 ). This poses a risk of disseminating unsubstantiated information. Therefore, scholars have been exploring ways to detect AI-generated content to uphold academic integrity, although there are conflicting perspectives on the utilization of detectors in academic publishing. Previous research found that 14 existing AI detection tools exhibited an average accuracy of less than 80% (Weber-Wulff et al. 2023 ). However, the availability of paraphrasing tools further complicates the detection of LLM-generated texts. Some AI content detectors were ineffective in identifying paraphrased texts (Anderson et al. 2023 ; Weber-Wulff et al. 2023 ). Moreover, some detectors may misclassify human-written articles, which can undermine the credibility of academic publications (Liang et al. 2023 ; Sadasivan et al. 2023 ).

Nevertheless, there have been advancements in AI content detectors. Turnitin and Originality.ai have shown excellent accuracy in discriminating between AI-generated and human-written essays in various academic disciplines (e.g., social sciences, natural sciences, and humanities) (Walters 2023 ). However, their effectiveness in detecting paraphrased academic articles remains uncertain. Importantly, the accuracy of universal AI detectors has shown inconsistencies across studies in different domains (Gao et al. 2023 ; Anderson et al. 2023 ; Walters 2023 ). Therefore, continuous efforts are necessary to identify detectors that can achieve near-perfect accuracy, especially in the detection of medical texts, which is of particular concern to the academic community.

In addition to using AI detectors to help identify AI-generated articles, it is crucial to assess the ability of human reviewers to detect AI-generated formal academic articles. A study found that four peer reviewers only achieved an average accuracy of 68% in identifying ChatGPT-generated biomedical abstracts (Gao et al. 2023 ). However, this study had limitations because the reviewers only assessed abstracts instead of full-text articles, and their assessments were limited to a binary choice of ‘yes’ or ‘no’ without providing any justifications for their decisions. The reported moderate accuracy is inadequate for informing new editorial policy regarding AI usage. To establish effective regulations for supervising AI usage in journal publishing, it is necessary to continuously explore the accuracy of experienced human reviewers and to understand the patterns and stylistic features of AI-generated content. This can help researchers, educators, and editors develop discipline-specific guidelines to effectively supervise AI usage in academic publishing.

Against this background, the current study aimed to (1) compare the accuracy of several common AI content detectors and human reviewers with different levels of research training in detecting AI-generated academic articles with or without paraphrasing; and (2) understand the rationale by human reviewers for determining AI-generated content.

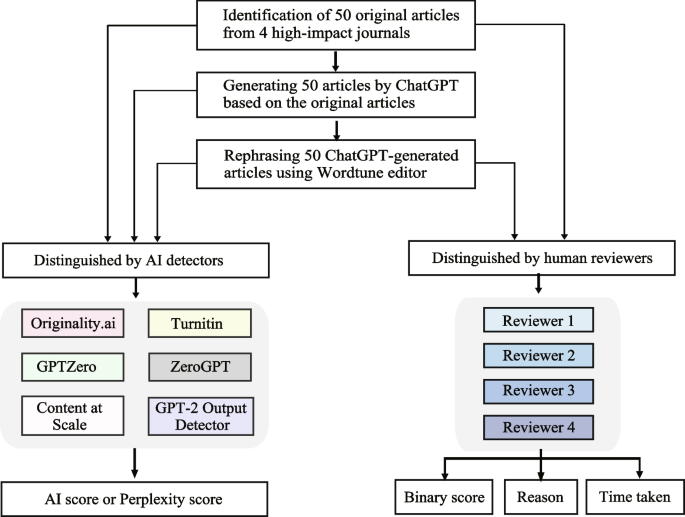

The current study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of a university. This study consisted of four stages: (1) identifying 50 published peer-reviewed papers from four high-impact journals; (2) generating artificial papers using ChatGPT; (3) rephrasing the ChatGPT-generated papers using a paraphrasing tool called Wordtune; and (4) employing six AI content detectors to distinguish between the original papers, ChatGPT-generated papers, and AI-rephrased papers. To determine human reviewers’ ability to discern between the original papers and AI-rephrased papers, four reviewers reviewed and assessed these two types of papers (Fig. 1 ).

An outline of the study

Identifying peer-reviewed papers

As this study was conducted by researchers involved in rehabilitation sciences, only rehabilitation-related publications were considered. A researcher searched on PubMed in June 2023 using a search strategy involving: (“Neurological Rehabilitation”[Mesh]) OR (“Cardiac Rehabilitation”[Mesh]) OR (“Pulmonary Rehabilitation” [Mesh]) OR (“Exercise Therapy”[Mesh]) OR (“Physical Therapy”[Mesh]) OR (“Activities of Daily Living”[Mesh]) OR (“Self Care”[Mesh]) OR (“Self-Management”[Mesh]). English rehabilitation-related articles published between June 2013 and June 2023 in one of four high-impact journals ( Nature, The Lancet, JAMA, and British Medical Journal [BMJ] ) were eligible for inclusion. Fifty articles were included and categorized into four categories (musculoskeletal, cardiopulmonary, neurology, and pediatric) (Appendix 1 ).

Generating academic articles using ChatGPT

ChatGPT (GPT-3.5-Turbo, OpenAI, USA) was used to generate the introduction, discussion, and conclusion sections of fabricated articles in July 2023. Specifically, before starting a conversation with ChatGPT, we gave the instruction “ Considering yourself as an academic writer ” to put it into a specific role. After that, we entered “ Please write a convincing scientific introduction on the topic of [original topic] with some citations in the text” into GPT-3.5-Turbo to generate the ‘Introduction’ section. The ‘Discussion’ section was generated by the request “Please critically discuss the methods and results below: [original method] and [original result], Please include citations in the text” . For the ‘Conclusions’ section, we instructed ChatGPT to create a summary of the generated discussion section with reference to the original title. Collectively, each ChatGPT-generated article comprised fabricated introduction, discussion, and conclusions sections, alongside the original methods and results sections.

Rephrasing ChatGPT-generated articles using a paraphrasing tool

Wordtune (AI21 Labs, Tel Aviv, Israel) (Wordtune 2023 ), a widely used AI-powered writing assistant, was applied to paraphrase 50 ChatGPT-generated articles, specifically targeting the introduction, discussion, and conclusion sections, to enhance their authenticity.

Identification of AI-generated articles

Using ai content detectors.

Six AI content detectors, which have been widely used (Walters 2023 ; Crothers 2023 ; Top 10 AI Detector Tools 2023 ), were applied to identify texts generated by AI language models in August 2023. They classified a given paper as “human-written” or “AI-generated”, with a confidence level reported as an AI score [% ‘confidence in predicting that the content was produced by an AI tool’] or a perplexity score [randomness or particularity of the text]. A lower perplexity score indicates that the text has relatively few random elements and is more likely to be written by generative AI (GPTZero 2023 ). The 50 original articles, 50 ChatGPT-generated articles, and 50 AI-rephrased articles were evaluated for authenticity by two paid (Originality.ai, Originality. AI Inc., Ontario, Canada; and Turnitin’s AI writing detection, Turnitin LLC, CA, USA) and four free AI content detectors (ZeroGPT, Munchberg, Germany; GPTZero, NJ, USA; Content at Scale, AZ, USA; and GPT-2 Output Detector, CA, USA). The authentic methods and results sections were not entered into the AI content detectors. Since the GPT-2 Output Detector has a restriction of 510 tokens per attempt, each article was divided into several parts for input, and the overall AI score of the article was calculated based on the mean score of all parts.

Peer reviews by human reviewers

Four blinded reviewers with backgrounds in physiotherapy and varying levels of research training (two college student reviewers and two professorial reviewers) were recruited to review and discern articles. To minimize the risk of recall bias, a researcher randomly assigned the 50 original articles and 50 AI-rephrased articles (ChatGPT-generated articles after rephrasing) to two electronic folders by a coin toss. If an original article was placed in Folder 1, the corresponding AI-rephrased article was assigned to Folder 2. Reviewers were instructed to review all the papers in Folder 1 first and then wait for at least 7 days before reviewing papers in Folder 2. This approach would reduce the reviewers’ risk of remembering the details of the original papers and AI-rephrased articles on the same topic (Fisher & Radvansky 2018 ).

The four reviewers were instructed to use an online Google form (Appendix 2 ) to make their decision and provide reasons behind their decision. Reviewers were instructed to enter the article number on the Google form before reviewing the article. Once the reviewers had gathered sufficient information/confidence to make the decision, they would give a binary response (“AI-rephrased” or “human-written”). Additionally, they should select their top three reasons for their decision from a list of options (i.e., coherence creativity, evidence-based, grammatical errors, and vocabulary diversity) (Walters 2019; Lee 2022 ). The definitions of these reasons (Appendix 3 ) were explained to the reviewers beforehand. If they could not find the best answers, they could enter additional responses. When the reviewer submitted the form, the total duration was automatically recorded by the system.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive analyses were reported when appropriate. Shapiro-Wilk tests were used to evaluate the normality of the data, while Levene’s tests were employed to assess the homogeneity of variance. Logarithmic transformation was applied to the data related to ‘time taken’ to achieve the normal distribution. Separate two-way repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) with post-hoc comparisons were conducted to evaluate the effect of detectors and AI usage on AI scores, and the effect of reviewers and AI usage on the time taken. Separate paired t-tests with Bonferroni correction were applied for pairwise comparisons. The GPTZero Perplexity scores were compared among groups of articles using one-way repeated ANOVA. Subsequently, separate paired t-tests with Bonferroni correction were used for pairwise comparisons. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were generated to determine cutoff values for the highest sensitivity and specificity in detecting AI articles by AI content detectors. The area under the ROC curve (AUROC) was also calculated. Inter-rater agreement was calculated using Fleiss’s kappa, and Cohen’s kappa with Bonferroni correction was used for multiple comparisons. The significance level was set at p < 0.05. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS (version 26; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

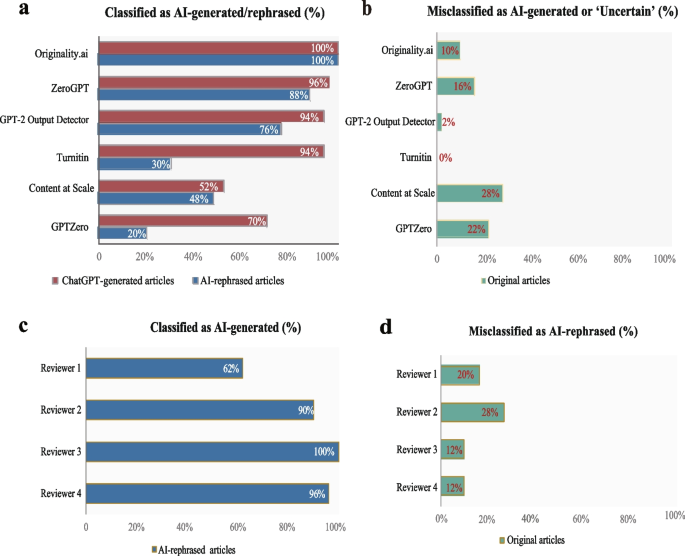

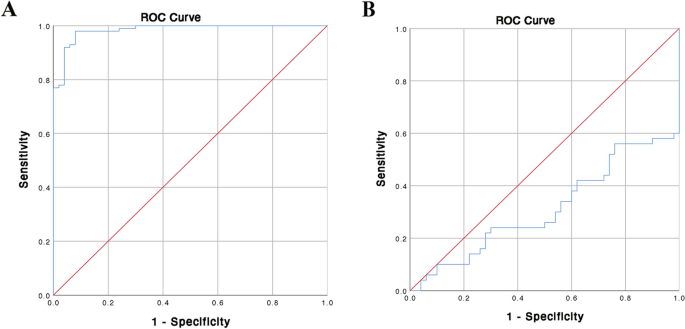

The accuracy of AI detectors in identifying AI articles

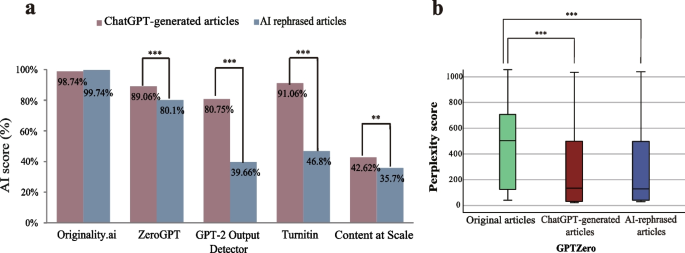

The accuracy of AI content detectors in identifying AI-generated articles is shown in Fig. 2 a and b. Notably, Originality.ai demonstrated perfect accuracy (100%) in detecting both ChatGPT-generated and AI-rephrased articles. ZeroGPT showed near-perfect accuracy (96%) in identifying ChatGPT-generated articles. The optimal ZeroGPT cut-off value for distinguishing between original and AI articles (ChatGPT-generated and AI-rephrased) was 42.45% (Fig. 3 a) , with a sensitivity of 98% and a specificity of 92%. The GPT-2 Output Detector achieved an accuracy of 96% in identifying ChatGPT-generated articles based on an AI score cutoff value of 1.46%, as suggested by previous research (Gao et al. 2023 ). Likewise, Turnitin showed near-perfect accuracy (94%) in discerning ChatGPT-generated articles but only correctly discerned 30% of AI-rephrased articles. GPTZero and Content at Scale only correctly identified 70 and 52% of ChatGPT-generated papers, respectively. While Turnitin did not misclassify any original articles, Content at Scale and GPTZero incorrectly classified 28 and 22% of the original articles, respectively. AI scores, or perplexity scores, in response to the original, ChatGPT-generated, and AI-rephrased articles from each AI content detector are shown in Appendix 4 . The classification of responses from each AI content detector is shown in Appendix 5 .

The accuracy of artificial intelligence (AI) content detectors and human reviewers in identifying large language model (LLM)-generated texts. a The accuracy of six AI content detectors in identifying AI-generated articles; b the percentage of misclassification of human-written articles as AI-generated ones by detectors; c the accuracy of four human reviewers (reviewers 1 and 2 were college students, while reviewers 3 and 4 were professorial reviewers) in identifying AI-rephrased articles; and d the percentage of misclassifying human-written articles as AI-rephrased ones by reviewers

The receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve and the area under the ROC (AUROC) of artificial intelligence (AI) content detectors. a The ROC curve and AUROC of ZeroGPT for discriminating between original and AI articles, with the AUROC of 0.98; b the ROC curve and AUROC of GPTZero for discriminating between original and AI articles, with the AUROC of 0.312

All AI content detectors, except Originality.ai, gave rephrased articles lower scores as compared to the corresponding ChatGPT-generated articles (Fig. 4 a). Likewise, GPTZero demonstrated that the perplexity scores of ChatGPT-generated (p<0.001) and AI-rephrased (p<0.001) texts were significantly lower than those of the original articles (Fig. 4 b) . The ROC curve of GPTZero perplexity scores for identifying original articles and AI articles showed that the respective AUROC were 0.312 (Fig. 3 b).

Artificial intelligence (AI)-generated articles demonstrated reduced AI scores after rephrasing. a The mean AI scores of 50 ChatGPT-generated articles before and after rephrasing; b ChatGPT-generated articles demonstrated lower Perplexity scores computed by GPTZero as compared to original articles although increased after rephrasing; * p < 0·05, ** p < 0·01, *** p < 0·001

The accuracy of reviewers in identifying AI-rephrased articles

The median time spent by the four reviewers to distinguish original and AI-rephrased articles was 5 minutes (min) 45 seconds (s) (interquartile range [IQR] 3 min 42 s, 9 min 7 s). The median time taken by each reviewer to distinguish original and AI-rephrased articles is shown in Appendix 6 . The two professorial reviewers demonstrated extremely high accuracy (96 and 100%) in discerning AI-rephrased articles, although both misclassified 12% of human-written articles as AI-rephrased (Fig. 2 c and d , and Table 1 ). Although three original articles were misclassified as AI-rephrased by both professorial reviewers, they were correctly identified by Originality and ZeroGPT. The common reasons for an article to be classified as AI-rephrased by reviewers included ‘incoherence’ (34.36%), ‘grammatical errors’ (20.26%), ‘insufficient evidence-based claims’ (16.15%), vocabulary diversity (11.79%), creativity (6.15%) , ‘misuse of abbreviations’(5.87%), ‘writing style’ (2.71%), ‘vague expression’ (1.81%), and ‘conflicting data’ (0.9%). Nevertheless, 12 of the 50 original articles were wrongly considered AI-rephrased by two or more reviewers. Most of these misclassified articles were deemed to be incoherent and/or lack vocabulary diversity. The frequency of the primary reason given by each reviewer and the frequency of the reasons given by four reviewers for identifying AI-rephrased articles are shown in Fig. 5 a and b, respectively.

A The frequency of the primary reason for artificial intelligence (AI)-rephrased articles being identified by each reviewer. B The relative frequency of each reason for AI-rephrased articles being identified (based on the top three reasons given by the four reviewers)

Regarding the inter-rater agreement between two professorial reviewers, there was near-perfect agreement in the binary responses, with κ = 0.819 (95% confidence interval [CI] 0.705, 0.933, p <0.05), as well as fair agreements in the primary and second reasons, with κ = 0.211 (95% CI 0.011, 0.411, p <0.05) and κ = 0.216 (95% CI 0.024, 0.408, p <0.05), respectively.

“Plagiarized” scores of ChatGPT-generated or AI-rephrased articles

Turnitin results showed that the content of ChatGPT-generated and AI-rephrased articles had significantly lower ‘plagiarized’ scores (39.22% ± 10.6 and 23.16% ± 8.54%, respectively) than the original articles (99.06% ± 1.27%).

Likelihood of ChatGPT being used in original articles after the launch of GPT-3.5-Turbo

No significant differences were found in the AI scores or perplexity scores calculated by the six AI content detectors (p>0.05), or in the binary responses evaluated by reviewers ( p >0.05), when comparing the included original papers published before and after November 2022 (the release of ChatGPT).

Our study found that Originality.ai and ZeroGPT accurately detected AI-generated texts, regardless of whether they were rephrased or not. Additionally, Turnitin did not misclassify human-written articles. While professorial reviewers were generally able to discern AI-rephrased articles from human-written ones, they might misinterpret some human-written articles as AI-generated due to incoherent content and varied vocabulary. Conversely, AI-rephrased articles are more likely to go unnoticed by student reviewers.

What is the performance of generative AI in academic writing?

Lee et al found that sentences written by GPT-3 tended to generate fewer grammatical or spelling errors than human writers (Lee 2022 ). However, ChatGPT may not necessarily minimize grammatical mistakes. In our study, reviewers identified ‘grammatical errors’ as the second most common reason for classifying an article as AI-rephrased. Our reviewers also noted that generative AI was more likely to inappropriately use medical terminologies or abbreviations, and even generate fabricated data. These might lead to a detrimental impact on academic dissemination. Collectively, generative AI is less likely to successfully create credible academic articles without the development of discipline-specific LLMs.

Can generative AI generate creative and in-depth thoughts?

Prior research reported that ChatGPT correctly answered 42.0 to 67.6% of questions in medical licensing examinations conducted in China, Taiwan, and the USA (Zong 2023 ; Wang 2023 ; Gilson 2023 ). However, our reviewers discovered that AI-generated articles offered only superficial discussion without substantial supporting evidence. Further, redundancy was observed in the content of AI-generated articles. Unless future advancements in generative AI can improve the interpretation of evidence-based content and incorporate in-depth and insightful discussion, its utility may be limited to serving as an information source for academic works.

Who can be deceived by ChatGPT? How can we address it?

ChatGPT is capable of creating realistic and intelligent-sounding text, including convincing data and references (Ariyaratne et al. 2023 ). Yeadon et al , found that ChatGPT-generated physics essays were graded as first-class essays in a writing assessment at Durham University (Yeadon et al. 2023 ). We found that AI-generated content had a relatively low plagiarism rate. These factors may encourage the potential misuse of AI technology for generating written assignments and the dissemination of misinformation among students. In a current survey, Welding ( 2023 ) reported that 50% of 1000 college students admitted to using AI tools to help complete assignments or exams. However, in our study, college student reviewers only correctly identified an average of 76% of AI-rephrased articles. Notably, our professorial reviewers found fabricated data in two AI-generated articles, while the student reviewers were unaware of this issue, which highlights the possibility of AI-generated content deceiving junior researchers and impacting their learning. In short, the inherent limitations of ChatGPT as reported by experienced reviewers may help research students understand some key points in critically appraising academic articles and be more competent in detecting AI-generated articles.

Which detectors are recommended for use?

Our study revealed that Originality.ai emerged as the most sensitive and accurate platform for detecting AI-generated (including paraphrased) content, although it requires a subscription fee. ZeroGPT is an excellent free tool that exhibits a high level of sensitivity and specificity for detecting AI articles when the AI score threshold is set at 42.45%. These findings could help monitor the AI use in academic publishing and education, to promisingly tackle ethical challenges posed by the iteration of AI technologies. Additionally, Turnitin, a widely used platform in educational institutions or scientific journals, displayed perfect accuracy in detecting human-written articles and near-perfect accuracy in detecting ChatGPT-generated content but was proved susceptible to deception when confronted with AI-rephrased articles. This raises concerns among educators regarding the potential for students to evade Turnitin AI detection by using an AI rephrasing editor. As generative AI technologies continue to evolve, educators and researchers should regularly conduct similar studies to identify the most suitable AI content detectors.

AI content detectors employ different predictive algorithms. Some publicly available detectors use perplexity scores and related concepts for identifying AI-generated writing. However, we found that the AUROC curve of GPTZero perplexity scores in identifying AI articles performed worse than chance. As such, the effectiveness of utilizing perplexity-based methods as the machine learning algorithm for developing an AI content detector remains debatable.

As with any novel technology, some merits and demerits require continuous improvement and development. Currently, AI content detectors have been developed as general-purpose tools to analyze text features, primarily based on the randomness of word choice and sentence lengths (Prillaman 2023 ). While technical issues such as algorithms, model turning, and development are beyond the scope of this study, we have provided empirical evidence that offers potential directions for future advancements in AI content detectors. One such area that requires further exploration and investigation is the development of AI content detectors trained using discipline-specific LLMs.

Should authors be concerned about their manuscripts being misinterpreted?

While AI-rephrasing tools may help non-native English writers and less experienced researchers prepare better academic articles, AI technologies may pose challenges to academic publishing and education. Previous research has suggested that AI content detectors may penalize non-native English writers with limited linguistic expressions due to simplified wording (Liang et al. 2023 ). However, scientific writing emphasizes precision and accurate expression of scientific evidence, often favouring succinctness over vocabulary diversity or complex sentence structures (Scholar Hangout 2023 ). This raises concerns about the potential misclassification of human-written academic papers as AI-generated, which could have negative implications for authors’ academic reputations. However, our results indicate that experienced reviewers are unlikely to misclassify human-written manuscripts as AI-generated if the articles present logical arguments, provide sufficient evidence-based support, and offer in-depth discussions. Therefore, authors should consider these factors when preparing their manuscripts to minimize the risk of misinterpretation.

Our study revealed that both AI content detectors and human reviewers occasionally misclassified certain original articles as AI-generated. However, it is noteworthy that no human-written articles were misclassified by both AI-content detectors and the two professorial reviewers simultaneously. Therefore, to minimize the risk of misclassifying human-written articles as AI-generated, editors of peer-reviewed journals may consider implementing a screening process that involves a reliable, albeit imperfect, AI-content detector in conjunction with the traditional peer-review process, which includes at least two reviewers. If both the AI content detectors and the peer reviewers consistently label a manuscript as AI-generated, the authors should be given the opportunity to appeal the decision. The editor-in-chief and one member of the editorial board can then evaluate the appeal and make a final decision.

Limitations

This study had several limitations. Firstly, the ChatGPT-3.5 version was used to fabricate articles given its popularity. Future studies should investigate the performance of upgraded LLMs. Secondly, although our analyses revealed no significant differences in the proportion of original papers classified as AI-written before and after November 2022 (the release of ChatGPT), we cannot guarantee that all original papers were not assisted by generative AI in their writing process. Future studies should consider including papers published before this date to validate our findings. Thirdly, although an excellent inter-rater agreement in the binary score was found between the two professorial reviewers, our results need to be interpreted with caution given the small number of reviewers and the lack of consistency between the two student reviewers. Future studies should address these limitations and expand our methodology to include other disciplines/industries with more reviewers to enhance the generalizability of our findings and facilitate the development of strategies for detecting AI-generated content in various fields.

Conclusions

This is the first study to directly compare the accuracy of advanced AI detectors and human reviewers in detecting AI-generated medical writing after paraphrasing. Our findings substantiate that the established peer-reviewed system can effectively mitigate the risk of publishing AI-generated academic articles. However, certain AI content detectors (i.e., Originality.ai and ZeroGPT) can be used to help editors or reviewers with the initial screening of AI-generated articles, upholding academic integrity in scientific publishing. It is noteworthy that the current version of ChatGPT is inadequate to generate rigorous scientific articles and carries the risk of fabricating data and misusing medical abbreviations. Continuous development of machine-learning strategies to improve AI detection accuracy in the health sciences field is essential. This study provides empirical evidence and valuable insights for future research on the validation and development of effective detection tools. It highlights the importance of implementing proper supervision and regulation of AI usage in medical writing and publishing. This ensures that relevant stakeholders can responsibly harness AI technologies while maintaining scientific rigour.

Availability of data and materials

The data and materials used in the manuscript are available upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Abbreviations

- Artificial intelligence

Large language model

Chat Generative Pre-trained Transformer

Receiver Operating Characteristic

Area under the Receiver Operating Characteristic

Anderson N, Belavy DL, Perle SM, Hendricks S, Hespanhol L, Verhagen E, Memon AR (2023) AI did not write this manuscript, or did it? Can we trick the AI text detector into generating texts? The potential future of ChatGPT and AI in sports & exercise medicine manuscript generation. BMJ Open Sport Exerc Med 9(1):e001568

Article Google Scholar

Ariyaratne S, Iyengar KP, Nischal N, Chitti Babu N, Botchu R (2023) A comparison of ChatGPT-generated articles with human-written articles. Skeletal Radiol 52:1755–1758

ChatGPT Statistics, 2023, Detailed Insights On Users. https://www.demandsage.com/chatgpt-statistics/ Accessed 08 Nov 2023

Crothers E, Japkowicz N, Viktor HL (2023) Machine-generated text: a comprehensive survey of threat models and detection methods. IEEE Access

Google Scholar

Fisher JS, Radvansky GA (2018) Patterns of forgetting. J Mem Lang 102:130–141

Gao CA, Howard FM, Markov NS, Dyer EC, Ramesh S, Luo Y, Pearson AT (2023) Comparing scientific abstracts generated by ChatGPT to real abstracts with detectors and blinded human reviewers. NPJ Digit Med 6:75

Gilson A, Safranek CW, Huang T, Socrates V, Chi L, Taylor RA, Chartash D (2023) How does ChatGPT perform on the United States medical licensing examination? The implications of large language models for medical education and knowledge assessment. JMIR Med Educ 9:e45312

GPTZero, 2023 , How do I interpret burstiness or perplexity? https://support.gptzero.me/hc/en-us/articles/15130070230551-How-do-I-interpret-burstiness-or-perplexity. Accessed August 20 2023

Hopkins AM, Logan JM, Kichenadasse G, Sorich MJ (2023) Artificial intelligence chatbots will revolutionize how cancer patients access information: ChatGPT represents a paradigm-shift. JNCI Cancer Spectr 7:pkad010

Imran M, Almusharraf N (2023) Analyzing the role of ChatGPT as a writing assistant at higher education level: a systematic review of the literature. Contemp Educ Technol 15:ep464

Lee M, Liang P, Yang Q (2022) Coauthor: designing a human-ai collaborative writing dataset for exploring language model capabilities. In: CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 1–19 ACM, April 2022

Liang W, Yuksekgonul M, Mao Y, Wu E, Zou J (2023) GPT detectors are biased against non-native English writers. Patterns (N Y) 4(7):100779

Manohar N, Prasad SS (2023) Use of ChatGPT in academic publishing: a rare case of seronegative systemic lupus erythematosus in a patient with HIV infection. Cureus 15(2):e34616

Mehnen L, Gruarin S, Vasileva M, Knapp B (2023) ChatGPT as a medical doctor? A diagnostic accuracy study on common and rare diseases medRxiv. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.04.20.23288859

OpenAI, 2023, Introducing ChatGPT. https://openai.com/blog/chatgpt .Accessed 30 Dec 2023

Patel SB, Lam K (2023) ChatGPT: the future of discharge summaries? Lancet Digital Health 5:e107–e108

Prillaman M (2023) ChatGPT detector' catches AI-generated papers with unprecedented accuracy. Nature. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-023-03479-4 Accessed 31 Dec 2023

Sadasivan V, Kumar A, Balasubramanian S, Wang W, Feizi S (2023) Can AI-generated text be reliably detected? arXiv e-prints: 2303.11156

Sallam M (2023) ChatGPT utility in healthcare education, research, and practice: systematic review on the promising perspectives and valid concerns. In Healthcare MDPI 887:1

Scholar Hangout, 2023, https://www.manuscriptedit.com/scholar-hangout/maintaining-accuracy-in-academic-writing/ .Accessed September 10 2023

Sinha RK, Deb Roy A, Kumar N, Mondal H (2023) Applicability of ChatGPT in assisting to solve higher order problems in pathology. Cureus 15(2):e35237

Stokel-Walker C (2023) ChatGPT listed as author on research papers: many scientists disapprove. Nature 613(7945):620–621

Top 10 AI Detector Tools, 2023, You Should Use. https://www.eweek.com/artificial-intelligence/ai-detector-software/#chart .Accessed August 2023

Walters WH (2023) The effectiveness of software designed to detect AI-generated writing: a comparison of 16 AI text detectors. Open Information Science 7:20220158

Wang Y-M, Shen H-W, Chen T-J (2023) Performance of ChatGPT on the pharmacist licensing examination in Taiwan. J Chin Med Assoc 10:1097

Weber-Wulff D, Anohina-Naumeca A, Bjelobaba S, Foltýnek T, Guerrero-Dib J, Popoola O, Šigut P, Waddington L (2023) Testing of detection tools for AI-generated text. Int J Educ Integrity 19(1):26

Welding L (2023) Half of college students say using AI on schoolwork is cheating or plagiarism. Best Colleges

Wordtune. 2023, https://app.wordtune.com/ .Accessed 16 July 2023

Yeadon W, Inyang O-O, Mizouri A, Peach A, Testrow CP (2023) The death of the short-form physics essay in the coming AI revolution. Phys Educ 58:035027

Zong H, Li J, Wu E, Wu R, Lu J, Shen B (2023) Performance of ChatGPT on Chinese National Medical Licensing Examinations: a five-year examination evaluation study for physicians, pharmacists and nurses. medRxiv:2023.2007. 2009.23292415

Download references

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

The current study was supported by the GP Batteries Industrial Safety Trust Fund (R-ZDDR).

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Rehabilitation Science, The Hong Kong Polytechnic University, Hong Kong, SAR, China

Jae Q. J. Liu, Kelvin T. K. Hui, Fadi Al Zoubi, Zing Z. X. Zhou, Curtis C. H. Yu, Jeremy R. Chang & Arnold Y. L. Wong

Department of Orthopedic Surgery, Rush University Medical Center, Chicago, IL, USA

Dino Samartzis

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

Jae QJ Liu, Kelvin TK Hui and Arnold YL Wong conceptualized the study; Fadi Al Zoubi, Zing Z.X. Zhou, Curtis CH Yu, and Arnold YL Wong acquired the data; Jae QJ Liu and Kelvin TK Hui curated the data; Jae QJ Liu and Jeremy R Chang analyzed the data; Arnold YL Wong was responsible for funding acquisition and project supervision; Jae QJ Liu drafted the original manuscript; Arnold YL Wong and Dino Samartzis edited the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Arnold Y. L. Wong .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

All authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Supplementary material 1., rights and permissions.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Liu, J.Q.J., Hui, K.T.K., Al Zoubi, F. et al. The great detectives: humans versus AI detectors in catching large language model-generated medical writing. Int J Educ Integr 20 , 8 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40979-024-00155-6

Download citation

Received : 27 December 2023

Accepted : 13 March 2024

Published : 20 May 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s40979-024-00155-6

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Paraphrasing tools

- Generative AI

- Academic integrity

- AI content detectors

- Peer review

- Perplexity scores

- Scientific rigour

International Journal for Educational Integrity

ISSN: 1833-2595

- Submission enquiries: Access here and click Contact Us

- General enquiries: [email protected]

An Overview of the Writing Process

Conclusions, what this handout is about.

This handout will explain the functions of conclusions, offer strategies for writing effective ones, help you evaluate your drafted conclusions, and suggest conclusion strategies to avoid.

About conclusions

Introductions and conclusions can be the most difficult parts of papers to write. While the body is often easier to write, it needs a frame around it. An introduction and conclusion frame your thoughts and bridge your ideas for the reader.

Just as your introduction acts as a bridge that transports your readers from their own lives into the “place” of your analysis, your conclusion can provide a bridge to help your readers make the transition back to their daily lives. Such a conclusion will help them see why all your analysis and information should matter to them after they put the paper down.

Your conclusion is your chance to have the last word on the subject. The conclusion allows you to have the final say on the issues you have raised in your paper, to summarize your thoughts, to demonstrate the importance of your ideas, and to propel your reader to a new view of the subject. It is also your opportunity to make a good final impression and to end on a positive note.

Your conclusion can go beyond the confines of the assignment. The conclusion pushes beyond the boundaries of the prompt and allows you to consider broader issues, make new connections, and elaborate on the significance of your findings.

Your conclusion should make your readers glad they read your paper. Your conclusion gives your reader something to take away that will help them see things differently or appreciate your topic in personally relevant ways. It can suggest broader implications that will not only interest your reader, but also enrich your reader’s life in some way. It is your gift to the reader.

Strategies for writing an effective conclusion

One or more of the following strategies may help you write an effective conclusion.

- Play the “So What” Game. If you’re stuck and feel like your conclusion isn’t saying anything new or interesting, ask a friend to read it with you. Whenever you make a statement from your conclusion, ask the friend to say, “So what?” or “Why should anybody care?” Then ponder that question and answer it. Here’s how it might go:

You: Basically, I’m just saying that education was important to Douglass.

Friend: So what?

You: Well, it was important because it was a key to him feeling like a free and equal citizen.

Friend: Why should anybody care?

You: That’s important because plantation owners tried to keep slaves from being educated so that they could maintain control. When Douglass obtained an education, he undermined that control personally.

You can also use this strategy on your own, asking yourself “So What?” as you develop your ideas or your draft.

- Return to the theme or themes in the introduction. This strategy brings the reader full circle. For example, if you begin by describing a scenario, you can end with the same scenario as proof that your essay is helpful in creating a new understanding. You may also refer to the introductory paragraph by using key words or parallel concepts and images that you also used in the introduction.

- Synthesize, don’t summarize: Include a brief summary of the paper’s main points, but don’t simply repeat things that were in your paper. Instead, show your reader how the points you made and the support and examples you used fit together. Pull it all together.

- Include a provocative insight or quotation from the research or reading you did for your paper.

- Propose a course of action, a solution to an issue, or questions for further study. This can redirect your reader’s thought process and help her to apply your info and ideas to her own life or to see the broader implications.

- Point to broader implications. For example, if your paper examines the Greensboro sit-ins or another event in the Civil Rights Movement, you could point out its impact on the Civil Rights Movement as a whole. A paper about the style of writer Virginia Woolf could point to her influence on other writers or on later feminists.

Strategies to avoid

- Beginning with an unnecessary, overused phrase such as “in conclusion,” “in summary,” or “in closing.” Although these phrases can work in speeches, they come across as wooden and trite in writing.

- Stating the thesis for the very first time in the conclusion.

- Introducing a new idea or subtopic in your conclusion.

- Ending with a rephrased thesis statement without any substantive changes.

- Making sentimental, emotional appeals that are out of character with the rest of an analytical paper.

- Including evidence (quotations, statistics, etc.) that should be in the body of the paper.

Four kinds of ineffective conclusions

- The “That’s My Story and I’m Sticking to It” Conclusion. This conclusion just restates the thesis and is usually painfully short. It does not push the ideas forward. People write this kind of conclusion when they can’t think of anything else to say. Example: In conclusion, Frederick Douglass was, as we have seen, a pioneer in American education, proving that education was a major force for social change with regard to slavery.

- The “Sherlock Holmes” Conclusion. Sometimes writers will state the thesis for the very first time in the conclusion. You might be tempted to use this strategy if you don’t want to give everything away too early in your paper. You may think it would be more dramatic to keep the reader in the dark until the end and then “wow” him with your main idea, as in a Sherlock Holmes mystery. The reader, however, does not expect a mystery, but an analytical discussion of your topic in an academic style, with the main argument (thesis) stated up front. Example: (After a paper that lists numerous incidents from the book but never says what these incidents reveal about Douglass and his views on education): So, as the evidence above demonstrates, Douglass saw education as a way to undermine the slaveholders’ power and also an important step toward freedom.

- The “America the Beautiful”/”I Am Woman”/”We Shall Overcome” Conclusion. This kind of conclusion usually draws on emotion to make its appeal, but while this emotion and even sentimentality may be very heartfelt, it is usually out of character with the rest of an analytical paper. A more sophisticated commentary, rather than emotional praise, would be a more fitting tribute to the topic. Example: Because of the efforts of fine Americans like Frederick Douglass, countless others have seen the shining beacon of light that is education. His example was a torch that lit the way for others. Frederick Douglass was truly an American hero.

- The “Grab Bag” Conclusion. This kind of conclusion includes extra information that the writer found or thought of but couldn’t integrate into the main paper. You may find it hard to leave out details that you discovered after hours of research and thought, but adding random facts and bits of evidence at the end of an otherwise-well-organized essay can just create confusion. Example: In addition to being an educational pioneer, Frederick Douglass provides an interesting case study for masculinity in the American South. He also offers historians an interesting glimpse into slave resistance when he confronts Covey, the overseer. His relationships with female relatives reveal the importance of family in the slave community.

Works consulted

We consulted these works while writing the original version of this handout. This is not a comprehensive list of resources on the handout’s topic, and we encourage you to do your own research to find the latest publications on this topic. Please do not use this list as a model for the format of your own reference list, as it may not match the citation style you are using. For guidance on formatting citations, please see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial .

All quotations are from:

Douglass, Frederick. Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave , edited and with introduction by Houston A. Baker, Jr., New York: Penguin Books, 1986.

Strategies for Writing a Conclusion. Literacy Education Online, St. Cloud State University. 18 May 2005 < http://leo.stcloudstate.edu/acadwrite/conclude.html >.

Conclusions. Nesbitt-Johnston Writing Center, Hamilton College. 17 May 2005 <http://www.hamilton.edu/academic/Resource/WC/SampleConclusions.html>.

- Conclusions. Provided by : The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Located at : http://writingcenter.unc.edu/ . License : CC BY-NC-ND: Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Table of contents. Step 1: Prewriting. Step 2: Planning and outlining. Step 3: Writing a first draft. Step 4: Redrafting and revising. Step 5: Editing and proofreading. Other interesting articles. Frequently asked questions about the writing process.

Writing a Conclusion. A conclusion is an important part of the paper; it provides closure for the reader while reminding the reader of the contents and importance of the paper. It accomplishes this by stepping back from the specifics in order to view the bigger picture of the document. In other words, it is reminding the reader of the main ...

The conclusion pushes beyond the boundaries of the prompt and allows you to consider broader issues, make new connections, and elaborate on the significance of your findings. Your conclusion should make your readers glad they read your paper. Your conclusion gives your reader something to take away that will help them see things differently or ...

Finally, some advice on how not to end an essay: Don't simply summarize your essay. A brief summary of your argument may be useful, especially if your essay is long--more than ten pages or so. But shorter essays tend not to require a restatement of your main ideas. Avoid phrases like "in conclusion," "to conclude," "in summary," and "to sum up ...

Level Up Your Team. See why leading organizations rely on MasterClass for learning & development. Conclusions are at the end of nearly every form of writing. A good conclusion paragraph can change a reader's mind when they reach the end of your work, and knowing how to write a thorough, engaging conclusion can make your writing more impactful.

Highlight the "so what". At the beginning of your paper, you explain to your readers what's at stake—why they should care about the argument you're making. In your conclusion, you can bring readers back to those stakes by reminding them why your argument is important in the first place. You can also draft a few sentences that put ...

1. Return to Your Thesis. Similar to how an introduction should capture your reader's interest and present your argument, a conclusion should show why your argument matters and leave the reader with further curiosity about the topic. To do this, you should begin by reminding the reader of your thesis statement.

Download this Handout PDF In academic writing, a well-crafted conclusion can provide the final word on the value of your analysis, research, or paper. Complete your conclusions with conviction! Conclusions show readers the value of your completely developed argument or thoroughly answered question. Consider the conclusion from the reader's perspective.

These three key elements make up a perfect essay conclusion. Now, to give you an even better idea of how to create a perfect conclusion, let us give you a sample conclusion paragraph outline with examples from an argumentative essay on the topic of "Every Child Should Own a Pet: Sentence 1: Starter.

Writing a compelling conclusion usually relies on the balance between two needs: give enough detail to cover your point, but be brief enough to make it obvious that this is the end of the paper. Remember that reiteration is not restatement. Summarize your paper in one to two sentences (or even three or four, depending on the length of the paper ...

Conclusion. A conclusion is a call to action. It reiterates the main idea of the essay stated in the introduction, summarizes the evidence presented in the body of the essay, draws any conclusions based on that evidence, and brings a written composition to a logical close. An essay, a research paper, or a report can end with any of the following:

It's better to leave it out of the paper than to include it in the conclusion. 5. Proofread and revise your conclusion before turning in your paper. Set aside your paper for at least a few hours. Then, re-read what you've written. Look for typos, misspelled words, incorrectly used words, and other errors.

Conclusions. A satisfying conclusion allows your reader to finish your paper with a clear understanding of the points you made and possibly even a new perspective on the topic. Any one paper might have a number of conclusions, but as the writer you must consider who the reader is and the conclusion you want them to reach.

Also read: How to Write a Thesis Statement. 2. Tying together the main points. Tying together all the main points of your essay does not mean simply summarizing them in an arbitrary manner. The key is to link each of your main essay points in a coherent structure. One point should follow the other in a logical format.

1. Restate the thesis. An effective conclusion brings the reader back to the main point, reminding the reader of the purpose of the essay. However, avoid repeating the thesis verbatim. Paraphrase your argument slightly while still preserving the primary point. 2. Reiterate supporting points.

Process writing is a natural set of steps that writers take to create a finished piece of work. It is a process of organizing ideas and creativity through text. The focus of process writing is on process, not on the end-product. It is useful for all skill levels, from children to published authors, to develop an authentic, creative work.

3.9: Conclusion to Writing Process. Page ID. Figure 3.9.1 3.9. 1. As this module emphasizes, a LOT happens behind the scenes when it comes to writing. We are used to seeing, and reading, finished works: books, course materials, online content. We aren't often exposed to all of the preparation and elbow grease that goes into the creation of ...

Process writing is a natural set of steps that writers take to create a finished piece of work. It is a process of organizing ideas and creativity through text. The focus of process writing is on process, not on the end-product. It is useful for all skill levels, from children to published authors, to develop an authentic, creative work.

Be yourself. If you're not a naturally serious person, don't force formality. If you're the comedian in your friend group, go ahead and be funny. But ultimately, write as your authentic (and grammatically correct) self and trust the process. And remember, thousands of other students your age are faced with this same essay writing task ...

Step 1: Answer your research question. Step 2: Summarize and reflect on your research. Step 3: Make future recommendations. Step 4: Emphasize your contributions to your field. Step 5: Wrap up your thesis or dissertation. Full conclusion example. Conclusion checklist. Other interesting articles.

The application of artificial intelligence (AI) in academic writing has raised concerns regarding accuracy, ethics, and scientific rigour. Some AI content detectors may not accurately identify AI-generated texts, especially those that have undergone paraphrasing. Therefore, there is a pressing need for efficacious approaches or guidelines to govern AI usage in specific disciplines.

Your conclusion is your chance to have the last word on the subject. The conclusion allows you to have the final say on the issues you have raised in your paper, to summarize your thoughts, to demonstrate the importance of your ideas, and to propel your reader to a new view of the subject. It is also your opportunity to make a good final ...

Promptframes unite the classic UX wireframe with prompt writing for generative AI. A promptframe is a design deliverable that documents content goals and requirements for generative-AI prompts based on a wireframe's layout and functionality. Promptframes organize and document prompts locationally within an existing wireframe.

In this article, the authors will describe a creative writing therapeutic group program they developed based on narrative therapy and narrative medicine principles. This was a Social Science and Humanities Research Council—Partnership Engagement Grant funded project, the aim of which was to develop a facilitator's manual for people interested in offering this group, titled "Journey ...