15 Feminism Examples

Feminism broadly refers to the theories and movements for women’s rights and liberation. Feminists argue that the modern society favors men’s perspectives and interests, therefore treating women and girls unfairly.

The feminist movement can be divided into four waves, starting with the first wave in the nineteenth century and evolving into the forth wave in our current society (Rampton, 2015).

Similarly, the modern feminist theory is divided into multiple branches, each with their own area of focus. Feminist theories include socialist feminism, liberal feminism, and radical feminism.

Each of these theories have a different view about the causes of gender inequality and the agenda for obtaining women’s rights and liberation (Epure, 2014).

Despite its different waves, branches, and variations within, feminism continues to be an influential social force in social theory and politics today.

The following examples demonstrate key ongoing causes of feminist movements.

- The Right to Vote – In the earlier forms of democracy , only male citizens had the right to vote. As a result, demands for women’s right to vote, also known as the suffragette movement, was the origin of the modern feminism in the West. While property-owner women and those from colonized territories started to gain the right to vote in the 1800’s, New Zealand was the first independent country where all adult women started to vote (Daley & Nolan, 1994).

- Equal Access to Education – Women and girls face multiple barriers in access to education across the globe. In several Western countries, women are underrepresented in STEM fields due to discrimination and gender bias . In some other countries, women and girls face barriers in access to secondary education due to socioeconomic and political reasons. For example, in Afghanistan, secondary education for girls has been banned since the Taliban came to power in August 2021 ( Unterhalter , 2022).

- The Right to Choose What to Wear – Women and girls have been facing legal, social, and religious restrictions on what to wear. Until the 1930s women in the United states were not allowed to wear tight and short swimsuits, and bikinis were unacceptable in parts of Europe until the 1960s (“Women being arrested,” 2021). Since 1979, women in Iran have been forced to comply with the mandatory Islamic dress code, including wearing headscarves and long coats (Zahedi, 2007). At the same time, many Muslim feminists argue for the right to wear headscarves in places like France and Quebec where those rights are curtailed.

- The Right to Own Property – Until the nineteenth century, married women were not allowed to be property owners. These restrictions included obtaining inheritance and owning land (Geddes & Tennyson, 2013).

- The Right to be Employed – Women have been facing legal and socio economic barriers against being employed and choosing their occupations. In Iran, women are banned from choosing occupations where they would perform as legal authorities (Moghadam, 2004).

- The Right to Run for Public Office – Until 1910, women were not allowed to run for public office in Portugal (Bonvin, 2016). In Iran the ban against women running for presidency still continues in practice, since 1979 (Moghadam, 2004).

- The Right to Parental Leave – Parental leave, which is also known as maternity leave, is an important right for women and gender equality. Currently in almost every country, women have the right to have a parental leave and return to their work after a period of time. However, the fact that a majority of countries give parental leave only to mothers raises criticism from the feminist movement as it shows the lack of gender equality in undertaking parental responsibilities (Lewis & Giullari, 2005).

- Breaking the Glass Ceiling – The glass ceiling refers to invisible barriers against upward mobility of women in workplaces. While women are a significant portion of the workforce, managerial positions tend to be dominated by men. Feminists challenge systemic discrimination and bias which create and sustain the glass ceiling (Williams, 2013).

- Equal Pay for Equal Work – Despite being a part of the workforce, women tend to be paid less than their male coworkers for the same work that they do. This global phenomenon is often referred to as the gender wage gap (Weichselbaumer & Winter‐Ebmer, 2005).

- The Right to Drive – Bertha Benz, the business partner and spouse of Karl Benz, was the first woman who drove an automobile for long distances in 1988 (Volti, 2006). However, by the 1910s, women drivers were still seen as unique or strange. Women started to be seen as possible buyers and owners of automobiles in the United States only in the 1930s (Parlin & Bremier, 2017). In Saudi Arabia, women obtained the right to drive their own cars in 2018, after decades of feminist protests (Khalil & Storie, 2021).

- The Right to Divorce – Women suffer from unequal divorce laws and their implications. In many countries across different continents, women face legal and social restrictions that prohibit them from having a divorce, or to keep full property rights or children’s custody after being divorced. For example, in the Philippines and Saudi Arabia women are not allowed to initiate a divorce, while in Iran and China the rights of divorced women are restricted (World Justice Project, 2020).

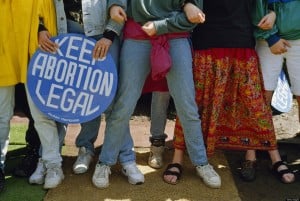

- The right to reproduction – Having legal access to safe reproductive surgery is one of the main demands of the feminist movements across the globe. Restrictions on reproductive rights depends on a range of factors such as duration of pregnancy and cause of pregnancy. By 2022, 24 countries in the World and 15 states in the United States severely restrict reproductive rights, including those in instances posing health risks (Davis, 2022).

- Accessing Feminine Hygiene Products – Despite their necessity, feminine hygiene products add a significant cost to the budget of women and girls. Similarly, other products that are specifically tailored for women are subject to pink tax, which refer to the unfairly higher costs of these items (Lafferty, 2019).

- Being Safe from Gender-based Violence – Women and girls across the globe experience harrasment and abuse at rates unmatched by other demographic groups. Sexual abuse has numerous physical, social and psychological effects on survivors which can be long-lasting. In 2010s, women started to use social media through #MeToo campaign to expose those who have abused them (Strauss Swanson & Szymanski, 2020).

- The Right to Live – Femicide, or murders against girls and women, is a global problem. Women across the world experience intimate partner violence, including being murdered by men that they know. Femicide is a significant issue particularly in Latin America and Turkey, where feminists fight for more efficient legal protection (Atuk, 2020).

The Four Waves of Feminism

1. first wave.

First Wave Feminism started in the late nineteenth century and continued until the early twentieth century.

First wave feminists were focused on increasing women’s rights and opportunities, especially through obtaining the right to vote (Rampton, 2015).

This wave of feminism was powerful in industrialised Western countries, among middle and upper class white women (Rampton, 2015).

2. Second Wave

Second Wave Feminism was dominant between 1960s and mid-1990s, in a time period where other social movement such as Vietnam War Protests were also powerful (Rampton, 2015).

This wave mainly focused on sexuality and reproductive rights, in addition to developing the feminist theory more (Rampton, 2015).

Unlike the first wave, second wave feminists went beyond white middle class women, and included international solidarity.

3. Third Wave

Third wave feminism was dominant between mid-90’s until early 2010s.

Third wave feminists were influenced both by post-modernism and the emergence of the internet.

Unlike the first two waves that saw sexualization of women as a sign of oppression , third wave feminists embraced feminine sexual symbols (Rampton, 2015).

4. Fourth Wave

Fourth wave feminism is the most recent wave of the feminist movement that started in early 2010s (Rampton, 2015).

Fourth wave feminists are influenced by intersectionality, which draws attention to the intersections of race, sexual orientation, class and other identities with gender (Rampton, 2015).

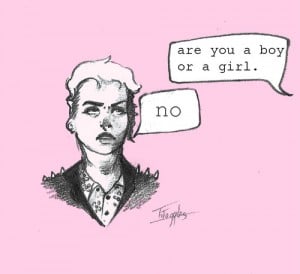

Fourth wave feminists challenge homophobia and transphobia as a part of their intersectional perspective.

This movement also uses the power of social media, through movements such as #MeToo to target sexual harrasment and assaults.

More in our series on Gender Studies

- Understanding Gender Norms

- Understanding Dominant Masculinity

- Understanding Dominant Femininity

- Hegemonic Masculinity

- Gender Socialization: How Genders are Reproduced

- Gender Stereotypes for Men and Women

- Are there really 81 Types of Genders?

Theories and movements that fight for women’s rights and liberation are broadly referred to as feminism.

Feminism is diverse both in terms of its theory and movements, including four different waves starting from nineteenth century and continuing up to today.

Throughout the world, feminists have been flighting for a variety of causes in different times of the history.

Feminist causes range from the right to vote or divorce to the right to be safe from sexual harrasment and abuse.

Atuk, S. (2020). Femicide and the speaking state: Woman killing and woman (re) making in Turkey. Journal of Middle East Women’s Studies , 16 (3), 283-306.

Bonvin, J. M. (2016). Transforming gendered well-being in Europe: the impact of social movements . Routledge.

Chavatzia, T. (2017). Cracking the code: Girls’ and women’s education in science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) . Paris, France: Unesco.

Daley, C., & Nolan, M. (Eds.). (1994). Suffrage and beyond: International feminist perspectives . NYU Press.

Davis, M. F. (2022). The state of abortion rights in the US. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics , 159 (1), 324-329.

Epure, M. (2014). Critically assess: The relative merits of liberal, socialist and radical feminism. J. Res. Gender Stud. , 4 , 514.

Geddes, R. R., & Tennyson, S. (2013). Passage of the married women’s property acts and earnings acts in the United States: 1850 to 1920. In Research in Economic History . Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

Khalil, A., & Storie, L. K. (2021). Social media and connective action: The case of the Saudi women’s movement for the right to drive. new media & society , 23 (10), 3038-3061.

Lafferty, M. (2019). The pink tax: the persistence of gender price disparity. Midwest Journal of Undergraduate Research , 11 (2019), 56-72.

Lewis, J., & Giullari, S. (2005). The adult worker model family, gender equality and care: the search for new policy principles and the possibilities and problems of a capabilities approach. Economy and society , 34 (1), 76-104.

Moghadam, V. M. (2004). Women in the Islamic Republic of Iran: Legal status, social positions, and collective action. Iran after , 25 , 1-16.

Parlin, C. C., & Bremier, F. (2017, March 13). Selling Cars to Women in the 1930s . The Saturday Evening Post. Retrieved November 18, 2022, from https://www.saturdayeveningpost.com/2017/03/selling-cars-women-1930s/

Strauss Swanson, C., & Szymanski, D. M. (2020). From pain to power: An exploration of activism, the# Metoo movement, and healing from sexual assault trauma. Journal of counseling psychology , 67 (6), 653-668.

Unterhalter, E. (2022, August 23). The history of secret education for girls in Afghanistan – and its use as a political symbol . The Conversation. Retrieved November 13, 2022, from https://theconversation.com/the-history-of-secret-education-for-girls-in-afghanistan-and-its-use-as-a-political-symbol-188622

UN Women. (2022). Timeline: Women of the world, unite! UN Women. Retrieved November 11, 2022, from https://interactive.unwomen.org/multimedia/timeline/womenunite/en/index.html

Volti, R. (2006). Cars and culture: The life story of a technology. JHU Press.

Weichselbaumer, D., & Winter‐Ebmer, R. (2005). A meta‐analysis of the international gender wage gap. Journal of economic surveys, 19(3), 479-511.

Williams, C. L. (2013). The glass escalator, revisited: Gender inequality in neoliberal times, SWS feminist lecturer . Gender & Society, 27 (5), 609-629.

Women being arrested for wearing one piece bathing suits, 1920s . (2021, November 26). Rare Historical Photos. Retrieved November 18, 2022, from https://rarehistoricalphotos.com/women-arrested-bathing-suits-1920s

World Justice Project. (2020, April 21). Divorce for All: A Women’s Access to Justice Issue . World Justice Project. Retrieved November 18, 2022, from https://worldjusticeproject.org/news/divorce-all-womens-access-justice-issue

Zahedi, A. (2007). Contested meaning of the veil and political ideologies of Iranian regimes. Journal of Middle East Women’s Studies , 3 (3), 75-98.

Sanam Vaghefi (PhD Candidate)

Sanam Vaghefi (BSc, MA) is a Sociologist, educator and PhD Candidate. She has several years of experience at the University of Victoria as a teaching assistant and instructor. Her research on sociology of migration and mental health has won essay awards from the Canadian Sociological Association and the IRCC. Currently, she is am focused on supporting students online under her academic coaching and tutoring business Lingua Academic Coaching OU.

- Sanam Vaghefi (PhD Candidate) #molongui-disabled-link Informal Social Control: 16 Examples and Definition

- Sanam Vaghefi (PhD Candidate) #molongui-disabled-link Culture vs Society: Similarities, Differences, Examples

- Sanam Vaghefi (PhD Candidate) #molongui-disabled-link 19 Urbanization Examples

- Sanam Vaghefi (PhD Candidate) #molongui-disabled-link 10 Indoctrination Examples

Chris Drew (PhD)

Dr. Chris Drew is the founder of the Helpful Professor. He holds a PhD in education and has published over 20 articles in scholarly journals. He is the former editor of the Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education. [Image Descriptor: Photo of Chris]

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 15 Animism Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 10 Magical Thinking Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ Social-Emotional Learning (Definition, Examples, Pros & Cons)

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ What is Educational Psychology?

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Feminist Theory in Sociology

An Overview of Key Ideas and Issues

Illustration by Hugo Lin. ThoughtCo.

- Key Concepts

- Major Sociologists

- News & Issues

- Research, Samples, and Statistics

- Recommended Reading

- Archaeology

Feminist theory is a major branch within sociology that shifts its assumptions, analytic lens, and topical focus away from the male viewpoint and experience toward that of women.

In doing so, feminist theory shines a light on social problems, trends, and issues that are otherwise overlooked or misidentified by the historically dominant male perspective within social theory .

Key Takeaways

Key areas of focus within feminist theory include:

- discrimination and exclusion on the basis of sex and gender

- objectification

- structural and economic inequality

- power and oppression

- gender roles and stereotypes

Many people incorrectly believe that feminist theory focuses exclusively on girls and women and that it has an inherent goal of promoting the superiority of women over men.

In reality, feminist theory has always been about viewing the social world in a way that illuminates the forces that create and support inequality, oppression, and injustice, and in doing so, promotes the pursuit of equality and justice.

That said, since the experiences and perspectives of women and girls were historically excluded for years from social theory and social science, much feminist theory has focused on their interactions and experiences within society to ensure that half the world's population is not left out of how we see and understand social forces, relations, and problems.

While most feminist theorists throughout history have been women, people of all genders can be found working in the discipline today. By shifting the focus of social theory away from the perspectives and experiences of men, feminist theorists have created social theories that are more inclusive and creative than those that assume the social actor to always be a man.

Part of what makes feminist theory creative and inclusive is that it often considers how systems of power and oppression interact , which is to say it does not just focus on gendered power and oppression, but on how this might intersect with systemic racism, a hierarchical class system, sexuality, nationality, and (dis)ability, among other things.

Gender Differences

Some feminist theory provides an analytic framework for understanding how women's location in and experience of social situations differ from men's.

For example, cultural feminists look at the different values associated with womanhood and femininity as a reason for why men and women experience the social world differently. Other feminist theorists believe that the different roles assigned to women and men within institutions better explain gender differences, including the sexual division of labor in the household .

Existential and phenomenological feminists focus on how women have been marginalized and defined as “other” in patriarchal societies . Some feminist theorists focus specifically on how masculinity is developed through socialization, and how its development interacts with the process of developing femininity in girls.

Gender Inequality

Feminist theories that focus on gender inequality recognize that women's location in and experience of social situations are not only different but also unequal to men's.

Liberal feminists argue that women have the same capacity as men for moral reasoning and agency, but that patriarchy , particularly the sexist division of labor, has historically denied women the opportunity to express and practice this reasoning.

These dynamics serve to shove women into the private sphere of the household and to exclude them from full participation in public life. Liberal feminists point out that gender inequality exists for women in a heterosexual marriage and that women do not benefit from being married.

Indeed, these feminist theorists claim, married women have higher levels of stress than unmarried women and married men. Therefore, the sexual division of labor in both the public and private spheres needs to be altered for women to achieve equality in marriage.

Gender Oppression

Theories of gender oppression go further than theories of gender difference and gender inequality by arguing that not only are women different from or unequal to men, but that they are actively oppressed, subordinated, and even abused by men .

Power is the key variable in the two main theories of gender oppression: psychoanalytic feminism and radical feminism .

Psychoanalytic feminists attempt to explain power relations between men and women by reformulating Sigmund Freud's theories of human emotions, childhood development, and the workings of the subconscious and unconscious. They believe that conscious calculation cannot fully explain the production and reproduction of patriarchy.

Radical feminists argue that being a woman is a positive thing in and of itself, but that this is not acknowledged in patriarchal societies where women are oppressed. They identify physical violence as being at the base of patriarchy, but they think that patriarchy can be defeated if women recognize their own value and strength, establish a sisterhood of trust with other women, confront oppression critically, and form female-based separatist networks in the private and public spheres.

Structural Oppression

Structural oppression theories posit that women's oppression and inequality are a result of capitalism , patriarchy, and racism .

Socialist feminists agree with Karl Marx and Freidrich Engels that the working class is exploited as a consequence of capitalism, but they seek to extend this exploitation not just to class but also to gender.

Intersectionality theorists seek to explain oppression and inequality across a variety of variables, including class, gender, race, ethnicity, and age. They offer the important insight that not all women experience oppression in the same way, and that the same forces that work to oppress women and girls also oppress people of color and other marginalized groups.

One way structural oppression of women, specifically the economic kind, manifests in society is in the gender wage gap , which shows that men routinely earn more for the same work than women.

An intersectional view of this situation shows that women of color, and men of color, too, are even further penalized relative to the earnings of white men.

In the late 20th century, this strain of feminist theory was extended to account for the globalization of capitalism and how its methods of production and of accumulating wealth center on the exploitation of women workers around the world.

Kachel, Sven, et al. "Traditional Masculinity and Femininity: Validation of a New Scale Assessing Gender Roles." Frontiers in Psychology , vol. 7, 5 July 2016, doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00956

Zosuls, Kristina M., et al. "Gender Development Research in Sex Roles : Historical Trends and Future Directions." Sex Roles , vol. 64, no. 11-12, June 2011, pp. 826-842., doi:10.1007/s11199-010-9902-3

Norlock, Kathryn. "Feminist Ethics." Standford Encyclopedia of Philosophy . 27 May 2019.

Liu, Huijun, et al. "Gender in Marriage and Life Satisfaction Under Gender Imbalance in China: The Role of Intergenerational Support and SES." Social Indicators Research , vol. 114, no. 3, Dec. 2013, pp. 915-933., doi:10.1007/s11205-012-0180-z

"Gender and Stress." American Psychological Association .

Stamarski, Cailin S., and Leanne S. Son Hing. "Gender Inequalities in the Workplace: The Effects of Organizational Structures, Processes, Practices, and Decision Makers’ Sexism." Frontiers in Psychology , 16 Sep. 2015, doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01400

Barone-Chapman, Maryann . " Gender Legacies of Jung and Freud as Epistemology in Emergent Feminist Research on Late Motherhood." Behavioral Sciences , vol. 4, no. 1, 8 Jan. 2014, pp. 14-30., doi:10.3390/bs4010014

Srivastava, Kalpana, et al. "Misogyny, Feminism, and Sexual Harassment." Industrial Psychiatry Journal , vol. 26, no. 2, July-Dec. 2017, pp. 111-113., doi:10.4103/ipj.ipj_32_18

Armstrong, Elisabeth. "Marxist and Socialist Feminism." Study of Women and Gender: Faculty Publications . Smith College, 2020.

Pittman, Chavella T. "Race and Gender Oppression in the Classroom: The Experiences of Women Faculty of Color with White Male Students." Teaching Sociology , vol. 38, no. 3, 20 July 2010, pp. 183-196., doi:10.1177/0092055X10370120

Blau, Francine D., and Lawrence M. Kahn. "The Gender Wage Gap: Extent, Trends, and Explanations." Journal of Economic Literature , vol. 55, no. 3, 2017, pp. 789-865., doi:10.1257/jel.20160995

- Socialist Feminism vs. Other Types of Feminism

- Patriarchal Society According to Feminism

- The Sociology of Gender

- Definition of Intersectionality

- What Is Sexism? Defining a Key Feminist Term

- 6 Quotes from ‘Female Liberation as the Basis for Social Revolution’

- Cultural Feminism

- Socialist Feminism Definition and Comparisons

- The Core Ideas and Beliefs of Feminism

- What Is Radical Feminism?

- Top 20 Influential Modern Feminist Theorists

- What Is Feminism Really All About?

- 10 Important Feminist Beliefs

- Liberal Feminism

- Feminist Literary Criticism

- Biography of Patricia Hill Collins, Esteemed Sociologist

subtitle: UK action. Stronger UN. Better world.

breadcrumb navigation:

- The 'F' Word /

- current page 10 examples of feminism in…

See magazine issue, 2017-2: The 'F' Word

Magazine edition: 2017-2

10 examples of feminism in action

Published on 13 December 2017

Updated: 15 January 2022

This autumn, a Women, Peace and Security Index was launched at the UN. Compiled by the Georgetown Institute for Women, Peace and Security and the Peace Research Institute of Oslo, it ranks 153 countries on: education, financial inclusion, mobile phone use, parliamentary seats, employment, discriminatory laws and norms, son bias, battlefield deaths, intimate partner violence and perception of community safety. Together, these factors provide a snapshot of women’s lives inside their homes and communities, and in public life.

Iceland tops the list. The UK is 12th and the US 22nd. Jamaica (41st) and the UAE (42nd) are above Hungary and Romania (joint 46th); Namibia (48th) and Lao (54th) are above Russia (55th) and Mexico (76th). Afghanistan and Syria are tied at the bottom. But just as all countries need to do more, they all have women who are fighting for progress. Here are 10 examples from across the Index.

1. Columbia

Colombia (96th) is recovering from over five decades of civil war, which left around 220,000 people dead. Rates of sexual and domestic violence are high. But Colombian women have insisted on being a part of the peace process. The accords that bought an end to the war include a requirement for women to participate in transitional justice, and promote formalised rural property rights for women.

2. South Africa

When South Africa (51st) embraced democracy in 1994, women set up the Soul City Programme. Using drama, entertainment and multimedia presentations Soul City has reached more than 80 per cent of South Africa’s population with their message that improv-ing health outcomes, and preventing the spread of AIDS, is best achieved by community action around consent and sexual health education.

Women in Iran (116th) face legal barriers that affect their domestic and professional lives, from restrictions on their ability to travel to exclusion from certain jobs. Speaking out on gender discrimination can lead to imprisonment. Despite these hurdles, Iran’s women lead the region in areas including education and financial inclusion, and activists have launched campaigns, such as ‘One Million Signatures’, to call for changes to the law.

Women played a vital role in bringing peace to Mali (146th). The Platform for Women Leaders of Mali worked – through the media and community engagement – to raise understanding of the peace agreement. After it was signed, they continued to lobby government on threats to their security. A new land-reform policy set aside 15 per cent of government-managed land for women’s associations and other groups in need.

5. Central African Republic

In the Central African Republic (149th) there are many instances of women’s groups working across ethnic and religious lines to reduce tensions and facilitate peace. In the town of Boda, Muslim women have escorted Christian women entering Muslim areas, and Christian women have done the same for Muslim women in Christian areas. Projects have been set up for different communities to farm jointly and participate in sport and drama activities.

6. Mongolia

Female United Nations peacekeepers from Mongolia (39th) have been protecting civilians in Sudan and South Sudan. In Darfur, more than half of the Mongolian troops are women. In South Sudan, they won a medal for actions including rescuing approximately 50 internally displaced people from attempted abduction. The Head of the UN Mission said, “Mongolian peacekeepers have led the way in terms of robustness”, praising the role of women in helping to empower local communities.

In Zambia (111th) women are more likely to own a business than men. Female entrepreneurs are coming to the fore in all sectors of the economy, inducing previously male-dominated industries such as mining. Progress has been led by Zambian women, with support from UN bodies including the International Labour Organization and World Food Programme, which have played a role in providing advice and support for women looking to start a business.

8. Malaysia

In Malaysia (91st) a network of Muslim women set up an organisation called Sisters in Islam to make the case that Islam is a feminist religion and that patriarchal behaviour within Muslim communities and countries comes from men deliberately misreading Islamic texts. Sisters in Islam works with Islamic scholars to to oppose gender-based injustice, and to produce materials that make clear the links between Islam and global human rights standards and norms.

9. Democratic Republic of Congo

In the Democratic Republic of Congo (148th) women in the media have worked with the UN to support victims of sexual exploitation and abuse, and to inform communities as to how to report abuses. These community-based reporting networks have used theatre, songs, quizzes, radio dramas and cartoons in order to expand and spread awareness. This year over 2,000 people were reached, and seven new networks set up.

10. Afghanistan

Afghanistan (152nd) is still one of the worst countries in the world to be a woman. But things are changing thanks to the demands of women’s rights activists. At present, there are more women in senior government positions than ever before. They have also secured a review of the cases of more than 400 women imprisoned due to so-called ‘moral crimes’. To date, over half have been released.

To access the Index and find out more, visit: https://giwps.georgetown.edu/the-index/

In this edition

Editorial: Not even close to equal

A feminist approach is self-evident and necessary

A feminist approach to international engagement

The smart thing to do

Can a feminist foreign policy really make a difference?

A feminist vision for the United Nations: How far has the Secretary-General come?

"Without the UN, there would have been genocide"

Racing to catch up: Gender parity at the UN

Does 'Zero Tolerance' work?

Keeping Britain global

We risk our lives for peace

Online exclusives

The Centre for Feminist Foreign Policy

Life in Ghouta

Transfeminism

Syrian Women Unite for Political Change

From Mosul to Cox’s Bazar

UN women and the emergence of feminist foreign policy

UNFPA: fighting back

“Not in my name”: challenging violent masculinity in South Africa

Human trafficking: forced labour and slavery

How Britain is failing women seeking asylum

Sweden and Saudi Arabia: Lessons for the UK

Sharing the "responsibility to protect"

The feminist movement has changed drastically. Here’s what the movement looks like today

ABC News spoke to feminists across the generations to define modern feminism.

Feminism, the first wave of which began with the suffrage movement in the mid-1800s, looks vastly different today than it did generations ago.

Thanks to the use of technology in activism, the adoption of alternative feminist philosophies into the mainstream, and more, feminists say the modern movement is defined by its intersectionality.

Feminists told ABC News that their fight is for the benefit of everyone – of all genders, races and more – led by a diverse set of voices to pave the way for gender equality worldwide in this fourth wave of feminism.

What is modern feminism defined by?

Feminism is the belief in the equality of people of all genders, a set of values aimed at dismantling gender inequality and the structures that uphold it.

These inequalities could be pay inequality, gender-based health care inaccessibility, rigid social expectations, or gender-based violence which still impact people everywhere to this day, feminists say.

In recent decades, the movement has begun to proactively include and uplift the voices of people who have typically been left out of past mainstream feminist movements. This includes women of color, as well as gender diverse people.

“Our gender, our race, disability, class, sexuality, and more – all of these pieces of ourselves generate different lived experiences and also help us understand that no one of us is just one thing,” said Diana Duarte, feminist group MADRE's Director of Policy and Strategic Engagement. “This inclusive vision is a powerful and integral part of feminism.”

Duarte said that “the personal is political” in feminism, “which is a way of understanding that our personal experiences are shaped by political realities that may be situated far from us or close to us.”

Our own experiences, she said, can inform and lead to political solutions.

Modern feminism co-opts the ideals of Black and queer feminist theories, activists say, in that it understands how the issues of gender, race and sexuality are all connected.

Uplifting the most marginalized groups of society will lead to wins for the overall advancement of gender equality worldwide, activists argue.

"[Author] Audre Lorde tells us that we do not live single issue lives, meaning that we do not have the luxury just to say, 'I'm only going to fight on this one issue,' because that's actually not possible," said Paris Hatcher, founder of the activist group Black Feminist Future.

How far has feminism come?

Mainstream feminism has not always been inclusive. For example, the suffrage movement and the teaching of it focuses on white women and their right to vote. National Organization for Women President Christian Nunes told ABC News that Black suffragists who helped win the passage of the 19th Amendment were erased by the white suffragist movement and in history books.

After the amendment’s passage, Black women continued to face barriers to voting.

“Even though there are women of color who were very instrumental in these movements and shifting it, and making sure that these rights were won, they just were not talked about,” Nunes told ABC News. “They were not mentioned, they were unsung heroes.”

She continued, “The fourth wave release focuses on: How do we be inclusive? How do we have allies? How do we really focus on true equality for all women? Because we know other waves of feminism have left women out.”

In becoming more inclusive, feminists around the globe have been able to make major strides in calling attention to and addressing multifaceted issues affecting women and girls across the globe.

In the U.S., the Women’s March and the racial reckoning of 2020 are two movements in which feminists played a major role.

“We're seeing women represented in … in so many different places, hold so many different levels of power that we haven't seen ever,” Nunes said, pointing to the achievements of Vice President Kamala Harris and Supreme Court Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson.

“We're seeing more women leaders, we're seeing more women scholars, we're seeing more activists, we're just seeing women really go out in their own authenticity in their own identities and live more truly and authentically.”

How much further does feminism have to go?

In recent years, though, the U.S. has faced a wave of laws restricting reproductive health care, transgender health care, certain curriculum in education, laws restricting voting rights, and more.

These have been seen as setbacks among feminist activists who argue that these laws create a “patriarchal world.”

Hatcher believes these laws support “a world where white men are in control, where the history that's told is upholding the history and the legacies of white men, and also where white men are able to control who was elected and who is not.”

Feminists say social media and technology will allow feminist movements across the globe to continue to connect, grow and spread their message.

Zikora Akanegbu, the creator of youth-led female empowerment group GenZHer, got her start in feminism on social media. She used it as a tool to be in conversations with and learn from other feminists.

“In middle school, in 2017, when [the MeToo Movement] was coming out on social media, I just joined Instagram,” Akanegbu told ABC News.

“When I think of feminism, I think it's women being able to share their voice … which we're seeing with the women speaking out in Iran the past few months,” Akanegbu said, referring to women protesting the Iranian government over the suspicious death of Mahsa Amini, a woman who was arrested by the country's "morality police" for not wearing a headscarf, as is required by Iranian law, and who died three days later in a hospital.

“Social media is a big part of moving the feminist movement forward,” Akanegbu said.

As for feminism and its reputation, there are still strides to be made, feminists say.

A Pew Research Center survey found that about 6 in 10 American women say “feminist” describes them very or somewhat well.

A majority of Americans – 64% – say feminism is empowering and 42% say it’s inclusive. However, 45% say it is polarizing and 30% say it’s outdated.

While women are more likely to associate feminism with positive attributes like empowering and inclusive, Pew found that men are more likely to see feminism as polarizing and outdated.

However, activists argue that negative perceptions of feminism are perpetuated by those who benefit from the patriarchy.

“[We should] not let our opponents define the identity of feminism for us,” Duarte said.

She continued, “It's important … not to lose sight of the community, the political grounding that feminism has offered to so many, where feminism actually has a great reputation that comes from the positive and meaningful reality of it that people have experienced all around the world.”

Module 9: Gender, Sex, and Sexuality

Feminist movements and feminist theory, learning outcomes.

- Evaluate feminist movements in the U.S. and the strengths and weaknesses of each

- Describe feminist theory

The Feminist Movement

One of the underlying issues that continues to plague women in the United States is misogyny . This is the hatred of or, aversion to, or prejudice against women. Over the years misogyny has evolved as an ideology that men are superior to women in all aspects of life. There have been multiple movements to try and fight this prejudice.

The feminist movement (also known as the women’s liberation movement, the women’s movement, or simply feminism) refers to a series of political campaigns for reform on a variety of issues that affect women’s quality of life. Although there have been feminist movements all over the world, this section will focus on the four eras of the feminist movement in the U.S.

First Wave Feminism (1848-1920)

The first women’s rights convention was held in Seneca Falls, New York (now known as the Seneca Falls Convention) from July 19-20, 1848, and advertised itself as “a convention to discuss the social, civil, and religious condition and rights of woman.” While ther e, 68 women and 32 men–100 out of some 300 attendees–signed the Declaration of Sentiments, also known as the Declaration of Rights and Sentiments, which was principally authored by Elizabeth Cady Stanton.

There was a notable connection between the movement to abolish slavery and the women’s rights movement. Frederick Douglass was heavily involved in both projects and believed it was essential for both groups to work together. As a fellow activistic the pursuit of equality and freedom from arbitrary discrimination, he was asked to speak at the Convention and to sign the Declaration of Sentiments. Despite this instance of movement kinship and intersectionality, it is important to note that no women of color attended the Seneca Convention.

In 1851, Lucy Gage led a women’s convention in Ohio where Sojourner Truth, who was born a slave and gave birth to five children in slavery, gave her famous “Ain’t I a Woman?” speech. Truth was born Isabella Bomfree in 1797 in New York, and was bought and sold four times during her lifetime. Her five-year-old son Peter was illegally sold into slavery in Alabama, though in 1827, with the help of an abolitionist family, she was able to buy her freedom and to successfully sue for the return of her son. [1] . She moved to New York City in 1828 and became part of the religious revivals then underway. Becoming an activist and speaker, in 1843 she renamed herself Sojourner Truth and dedicated her life to working toward the end of slavery and for women’s rights and temperance.

The 15th Amendment, ratified in 1870, was unpopular with suffragists because it did not include women in its guarantee of the right to vote irrespective of “race, color, or previous condition of servitude.” Suffragette Susan B. Anthony (in)famously said, “I will cut off this right arm of mine before I will ever work or demand the ballot for the Negro and not the woman,” but abolitionists and early Republicans were intent on prioritizing Black men’s suffrage over that of women [2] . This further complicated the suffragist movement, as many prominent participants opposed the 15th amendment, which earned them unhelpful support from Reconstruction-era racists who opposed suffrage for Black men.

Figure 1. Woman’s suffrage around the world in 1908.

The 1920 ratification of the 19th Amendment is the biggest success of the first wave, and it took 72 years to get it passed. As you can see from the map above, the United States was far behind other countries in terms of suffrage. Charlotte Woodward, one of 100 signers of the 1848 Declaration of Sentiments, was the only signatory still alive when the Nineteenth Amendment passed; however, Woodward was not well enough to vote. Another leading feminist from this early period was Margaret Sanger, who advocated for free and available birth control.

The limitations of this wave were related to its lack of inclusion of women of color and poor women. The movement was led by educated white women and often willfully ignored pressing issues for the rest of the women in the United States.

Second Wave Feminism (1960s-1980s)

Whereas the first wave of feminism was generally propelled by middle class, western, cisgender, white women, the second phase drew in women of color and women from developing nations, seeking sisterhood and solidarity, and claiming “Women’s struggle is class struggle.” [3] Feminists spoke of women as a social class and coined phrases such as “the personal is political” and “identity politics” in an effort to demonstrate that race, class, and gender oppression are all related. They initiated a concentrated effort to rid society top-to-bottom of sexism, from children’s cartoons to the highest levels of government (Rampton 2015).

Margaret Sanger, birth control advocate from the first wave, lived to see the Food and Drug Administration approve the combined oral contraceptive pill in 1960, which was made available in 1961 (she died in 1966). President Kennedy made women’s rights a key issue of the New Frontier (a slate of ambitious domestic and foreign policy initiatives), and named women (such as Esther Peterson) to many high-ranking posts in his administration (1961-1963).

Like first wave feminists, second wave feminists were influenced by other contemporaneous social movements. During the 1960s, these included the civil rights movement, anti-war movement, environmental movement, student movement, gay rights movement, and the farm workers movement.

The Equal Rights Amendment (ERA) was proposed by first wave feminists in 1923, and was premised on legal equality of the sexes. It was ratified by Congress in 1972 but failed to achieve the three-fourths majority in the states required to make it the 23rd Amendment to the Constitution. [4] . Although this effort was not successful, other gains were made, including increased attention to domestic violence and marital rape issues, the establishment of rape crisis and battered women’s shelters, and changes in child custody and divorce law.

In 1963 Betty Friedan, influenced by Simone De Beauvoir’ s 1947 book The Second Sex , wrote the bestselling The Feminine Mystique , in which she objected to the m ainstream media depiction of women and argued that narrowly reducing women to the status of homemakers limited their potential and wasted their talent. The idealized nuclear family that was prominently marketed at the time, she wrote, did not reflect authentic happiness and was in fact often unsatisfying and degrading for women. Friedan’s book is considered one of the most important founding texts of second wave feminism. In 1966, the National Organization for Women (NOW) formed and proceeded to set an agenda for the feminist movement . Framed by a statement of purpose written by Friedan, the agenda began by proclaiming NOW’s goal to make possible women’s participation in all aspects of American life and to gain for them all the rights enjoyed by men.

Link to Learning

Watch this video clip to learn more about the success and impact of Friedan’s book .

Feminists engaged in protests and actions designed to bring awareness and change. For example, the New York Radical Women demonstrated at the 1968 Miss America Pageant in Atlantic City to bring attention to the contest’s—and society’s—exploitation of women. The protestors tossed instruments of women’s oppression, including high-heeled shoes, curlers, girdles, and bras, into a “freedom trash can.” News accounts incorrectly described the protest as a “bra burning,” which at the time was a way to demean and trivialize the issue of women’s rights (Gay 2018).

Other protests gave women a more significant voice in a male-dominated social, political, and entertainment climate. For decades, Ladies Home Journal had been a highly influential women’s magazine, managed and edited almost entirely by men. Men even wrote the advice columns and beauty articles. In 1970, protesters held a sit-in at the magazine’s offices, demanding that the company hire a woman editor-in-chief, add women and non-White writers at fair pay, and expand the publication’s focus.

Feminists were concerned with far more than protests, however. In the 1970s, they opened battered women’s shelters and successfully fought for protection from employment discrimination for pregnant women, reform of rape laws (such as the abolition of laws requiring a witness to corroborate a woman’s report of rape), criminalization of domestic violence, and funding for schools that sought to counter sexist stereotypes of women. In 1973, the U.S. Supreme Court in Roe v. Wade invalidated a number of state laws under which abortions obtained during the first three months of pregnancy were illegal. This made a nontherapeutic abortion a legal medical procedure nationwide.

Thus, the successes of the second wave included a more individualistic approach to feminism, a broadening of issues beyond voting and property rights, and greater awareness of timely feminist objectives through books and television. However, there were some impactful political disappointments, as the ERA was not ratified by the states, and second wave feminists were not able to create lasting coalitions with other social movements.

Many advances in women’s rights were the result of women’s greater engagement in politics. For example, Patsy Mink, the first Asian American woman elected to Congress, was the co-author of the Education Amendments Act of 1972, Title IX of which prohibits sex discrimination in education. Mink had been interested in fighting discrimination in education since her youth, when she opposed racial segregation in campus housing while a student at the University of Nebraska. She went to law school after being denied admission to medical school because of her gender. Like Mink, many other women sought and won political office, many with the help of the National Women’s Political Caucus (NWPC). In 1971, the NWPC was formed by Bella Abzug, Gloria Steinem, Shirley Chisholm, and other leading feminists to encourage women’s participation in political parties, elect women to office, and raise money for their campaign.

Figure 2 . “Unbought and Unbossed”: Shirley Chisholm was the first Black United States Congresswoman, the co-founder of the Congressional Black Caucus, and a candidate for a major-party Presidential nomination.

Shirley Chisholm personally took up the mantle of women’s involvement in politics. Born of immigrant parents, she earned degrees from Brooklyn College and Columbia University, and began a career in early childhood education and advocacy. In the 1950’s she joined various political action groups, worked on election campaigns, and pushed for housing and economic reforms. After leaving one organization over its refusal to involve women in the decision-making process, she sought to increase gender and racial diversity within political and activist organizations throughout New York City. In 1968, she became the first Black woman elected to Congress. Refusing to take the quiet role expected of new Representatives, she immediately began sponsoring bills and initiatives. She spoke out against the Vietnam War, and fought for programs such as Head Start and the national school lunch program, which was eventually signed into law after Chisholm led an effort to override a presidential veto. Chisholm would eventually undertake a groundbreaking presidential run in 1972, and is viewed as paving the way for other women, and especially women of color, achieving political and social prominence (Emmrich 2019).

Third Wave Feminism (1990s-2008)

Figure 3. The “We Can Do It!” poster from 1943 was re-appropriated as a symbol of the feminist movement in the 1980s.

Third-wave feminism refers to several diverse strains of feminist activity and study, whose exact boundaries in the history of feminism are a subject of debate. The movement arose partially as a response to the perceived failures of and backlash against initiatives and movements created by second-wave feminism. Post-colonial and postmodern theory, which work, among other goals, toward the destabilization of social constructions of gender and sexuality, including the notion of “universal womanhood,” have also been important influences (Rampton 2015). This wave broadened the parameters of feminism to include a more diverse group of women and a more fluid range of sexual and gender identities.

Popular television shows like Sex in the City (1998-2004) elevated a type of third wave feminism that merged feminine imagery (i.e., lipstick, high heels, cleavage), which were previously associated with male oppression, with high powered careers and robust sex lives. The “grrls” of the third wave stepped onto the stage as strong and empowered, eschewing victimization and defining feminine beauty for themselves as subjects, not as objects of a sexist patriarchy; they developed a rhetoric of mimicry, which appropriated derogatory terms like “slut” and “bitch” in order to subvert sexist culture and deprive it of verbal weapons (Rampton 2015).

Third wave feminists effectively used mass media, particularly the web (“cybergrrls” and “netgrrls”), to create a feminism that is global, multicultural, and boundary-crossing. One important third wave sub-group was the Riot Grrrl movement, whose DIY (do it yourself) ethos produced a number of influential, independent feminist musicians, such as Bikini Kill and Sleater-Kinney.

Third wave feminism’s focus on identity and the blurring of boundaries, however, did not effectively address many persistent macrosociological issues such as sexual harassment and sexual assault.

Fourth Wave Feminism (2008-present)

Fourth wave feminism is shaped by technology and characterized by the #metoo and the #timesup movements. Considering that these hashtags were first introduced on Twitter in 2007, this movement has grown rapidly, as social media activism has spread interest in and awareness of feminism.

Waves of accusations against men in powerful positions—from Hollywood directors, to Supreme Court justices, to the President of the United States, have catalyzed feminists in a way that appears to be fundamentally different compared to previous iterations.

As Rampton (2015) states, “The emerging fourth wavers are not just reincarnations of their second wave grandmothers; they bring to the discussion important perspectives taught by third wave feminism; they speak in terms of intersectionality whereby women’s suppression can only fully be understood in a context of the marginalization of other groups and genders—feminism is part of a larger consciousness of oppression along with racism, ageism, classism, ableism, and sexual orientation (no “ism” to go with that).”

Successes of fourth wave feminists include the proliferation of social media tags that promote inclusion and more effectively dismantle the gender and sexual binaries that have fragmented the movement. Female farm workers are demanding to have sexual harassment in the fields addressed alongside Hollywood actors.

The unprecedented number of women who were elected to Congress in the 2018 midterm elections is another sign of success for fourth wave feminists. Specifically, we can see that women of color, whose intersectional commitments also extend to environmental issues and income inequality, are represented in substantial numbers in both chambers.

Watch this video for an overview of gender in sociology. The video begins with an explanation of Harriet Martineau and her important contributions to sociology, then examines gender-conflict theory and three of the four waves of feminism.

Feminist Theory

Feminist theory is a type of conflict theory that examines inequalities in gender-related issues. It uses the conflict approach to examine the maintenance of gender roles and uneven power relations. Radical feminism, in particular, considers the role of the family in perpetuating male dominance (note that “radical” means “at the root”). In patriarchal societies, men’s contributions are seen as more valuable than those of women. Patriarchal perspectives and arrangements are widespread and taken for granted. As a result, women’s viewpoints tend to be silenced or marginalized to the point of being discredited or considered invalid. Peggy Reeves Sanday’s study of the Indonesian Minangkabau (2004) revealed that in societies considered to be matriarchies (where women comprise the dominant group), women and men tend to work cooperatively rather than competitively, regardless of whether a job would be gendered as feminine by U.S. standards. The men, however, do not experience the sense of bifurcated (i.e., divided into two parts) consciousness under this social structure that modern U.S. females encounter (Sanday 2004).

Patriarchy refers to a set of institutional structures (like property rights, access to positions of power, relationship to sources of income) that are based on the belief that men and women are dichotomous and unequal categories of being. The key to patriarchy is what might be called the dominant gender ideology toward sexual differences: the assumption that physiological sex differences between males and females are related to differences in their character, behavior, and ability (i.e., their gender). These differences are used to justify a gendered division of social roles and inequality in access to rewards, positions of power, and privilege. The question that feminists ask therefore is: How does this distinction between male and female, and the attribution of different qualities to each, serve to organize our institutions (e.g., the family, law, the occupational structure, religious institutions, the division between public and private) and to perpetuate inequality between the sexes?

One of the influential sociological insights that emerged within second wave feminism is that “the personal is political.” This is a way of acknowledging that the challenges and personal crises that emerge in one’s day-to-day lived experience are symptomatic of larger systemic political issues, and that the solutions to such problems must be collectively pursued. As Friedan and others showed, these personal dissatisfactions often originated in previously unquestioned, stubbornly gendered discrepancies.

Standpoint Theory

Many of the most immediate and fundamental experiences of social life—from childbirth to who washes the dishes to the experience of sexual violence—had simply been invisible or regarded as unimportant politically or socially. Dorothy Smith’s development of standpoint theory was a key innovation in sociology that enabled these issues to be seen and addressed in a systematic way by examining one’s position in life (Smith 1977). She recognized from the consciousness-raising exercises and encounter groups initiated by feminists in the 1960s and 1970s that many of the immediate concerns expressed by women about their personal lives had a commonality of themes.

Smith argued that instead of beginning sociological analysis from the abstract point of view of institutions or systems, women’s lives could be more effectively examined if one began from the “actualities” of their lived experience in the immediate local settings of “everyday/ everynight” life. She asked, “What are the common features of women’s everyday lives?” From this standpoint, Smith observed that women’s position in modern society is acutely divided by the experience of dual consciousness (recall W.E.B. DuBois’ double consciousness ). Every day women crossed a tangible dividing line when they went from the “particularizing work in relation to children, spouse, and household” to the institutional world of text-mediated, abstract concerns at work, or in their dealings with schools, medical systems, or government bureaucracies. In the abstract world of institutional life, the actualities of local consciousness and lived life are “obliterated” (Smith 1977). Note again that Smith’s argument is in keeping with the second wave feminist idea that “the personal” (child-rearing, housekeeping) complicates and illuminates one’s relationship to “the political” (work life, government bureaucracies).

Intersectional Theory

Recall that intersectional theory examines multiple, overlapping identities and social contexts (Black, Latina, Asian, gay, trans, working class, poor, single parent, working, stay-at-home, immigrant, undocumented, etc.) and the unique, various lived experiences within these spaces. Intersectional theory combines critical race theory, gender conflict theory, and critical components of Marx’s class theory. Kimberlé Crenshaw describes it as a “prism for understanding certain kinds of problems.”

How does the convergence or racial or gender stereotypes play out in classrooms? How does this influence the opportunity for equal education? Consider these issues as you watch this short clip from Kimberlé Crenshaw.

- Michals, D. "Soujourner Truth." National Women's History Museum. https://www.womenshistory.org/education-resources/biographies/sojourner-truth . ↵

- Ford, S. 2017. "How racism split the suffrage movement. Bust Magazine. https://bust.com/feminism/19147-equal-means-equal.html . ↵

- Rampton, M. (2015). "Four waves of feminism." Pacific University Oregon. https://www.pacificu.edu/about/media/four-waves-feminism . ↵

- "Equal Rights Amendment." This Day in History. https://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/equal-rights-amendment-passed-by-congress . ↵

- Revision, Modification, and Original Content. Provided by : Lumen Learning. License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Feminist Movement. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Feminist_movement . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- First-wave feminism. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/First-wave_feminism#United_States . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Second-wave feminism. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Second-wave_feminism . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Third-wave feminism. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Third-wave_feminism . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Seneca Falls Convention. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Seneca_Falls_Convention#Remembrances . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- The Women's Rights Movement. Authored by : Boundless. Located at : https://courses.lumenlearning.com/boundless-politicalscience/ . Project : Political Science. License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Gender and Gender Inequality. Provided by : OpenStax. Located at : https://openstax.org/books/introduction-sociology-3e/pages/12-2-gender-and-gender-inequality . Project : Sociology 3e. License : CC BY: Attribution . License Terms : Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/introduction-sociology-3e/pages/1-introduction

- Women's Movement USA - 1950s-60s. Authored by : International School History. Located at : https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=amZD8XxTsjQ . License : Other . License Terms : Standard YouTube License

- Kimberlee Crenshaw: What is Intersectionality?. Authored by : National Association of Independent Schools (NAIS). Located at : https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ViDtnfQ9FHc . License : Other . License Terms : Standard YouTube License

- We Can Do It! Poster. Authored by : J. Howard Miller from Westinghouse. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Feminist_movement#/media/File:We_Can_Do_It!.jpg . License : CC0: No Rights Reserved

- Woman's Suffrage 1908. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Women%27s_Suffrage_1908.jpg . License : Public Domain: No Known Copyright

Dear Beloved Reader , we're going to be real with you.

We're asking you to join our membership program so we can become fully financially sustainable (and you'll get cool perks too!) and avoid shutting down.

Every year, we reach over 6.5 million people around the world with our intersectional feminist articles and webinars. But we now depend 100% on reader support to keep going.

If everyone reading this only gave $12, we could raise enough money for the entire year in just one day.

For the price of a single lunch out, you can help save us. We're an independent feminist media site led entirely by people of color. If Everyday Feminism has been useful to you, please take one minute to keep us alive. Thank you!

How to Apply Feminism to Your Everyday Life

Click for the Transcript

So, I’m a pretty hardcore feminist. I’m a Women and Gender Studies major in college; I write for feminist websites like RH Reality Check, Everyday Feminism, Adios Barbie; and I’ve done a lot of internships working for nonprofits.

I’m pretty much dedicating my life to being a professional feminist. But that doesn’t mean that you have to.

I think one of the biggest misconceptions about feminism is that you have to be super hardcore, you have to dedicate your life to it, and unless you go full-force, you’re not doing it right. And I’m here to tell you that that is not true.

Feminism is an ideology, so it’s all about the way that you approach the world and live your life. There are so many ways that you can take feminism into your everyday life and not really change anything about your life, but make it more feminist and come from a feminist approach.

So I’m going to give you six ways today that you can do that.

The first thing is to check your privilege. We all have privilege. I guess maybe there’s someone in the world without any, but you can pretty much assume you have privilege. Privilege means that you have some type of automatic entitlement in society.

For example, I’m white. That means I have white privilege. That means that in society, I get preferential treatment just because I’m white. And that means I have access to more resources, it means that I don’t face the same discrimination or prejudice that people of color do, it means I can see people of my race represented in the media, etc.

And with that comes learning about oppression, learning about people’s experiences that are marginalized. Really learning about your privilege and the privileges that you have, and then learning to check those privileges: that’s probably one of the most feminist things you can do.

The next way you can be more feminist in your everyday life is to read some feminist books! I personally love, love, love reading. That’s actually how I sort of discovered feminism: I read Jessica Valenti’s Full Frontal Feminism , which I would highly recommend.

There are so many great women’s studies and gender studies and feminist books out there that you read and really learn all about feminism. It’s cool because there’s so many different topics. So if you’re into history, you can learn about some of the history behind different movements and different waves. Or you could read a book about sexuality if you’re into sexuality. There’s so many different subjects and there’s so many different topics that you can choose from coming from a feminist lens.

If you want a place to start, I would actually recommend Jessica Valenti’s Full Frontal Feminism as a place to start, or even just going into Amazon and typing in “feminism;” there’s a lot of great books that will come up.

The third thing is to talk to people. One of the best ways that we can make feminism part of our lives is to make it a part of our interactions with other people. So that can be talking to your friends and family about things that come up–maybe a recent ban on abortion, or talking about gay marriage being legalized in Oregon (which just happened today). Some kind of news story that has feminism or sexism somehow weaved into it, and asking people’s opinions.

Or you can seek out people who are into feminism and have conversations with them over social media, email some of your favorite authors, and start learning from their experience. And with that, I would also say to start talking to people that may have marginalized perspectives and learning from them. I can’t tell you the amount of people I know, growing up in a white suburb, who don’t have a single friend who’s a person of color, or knows anyone who identifies as LGBT.

So I think talking to people and starting conversations, and also learning from their experience is a really great way to apply feminism in your everyday life.

The fourth thing on my list is to take a class. If you are in college, you could take a Women and Gender Studies class, or you could even take something like Women in History, you could take a class about women in politics. There’s a lot of different classes you could take, it doesn’t necessarily have to be under the umbrella of Women and Gender Studies, but that’s definitely a good place to start.

Especially if you’re getting an education, you should be learning about things you want to learn about! So make sure to fit that in somewhere. Even though, like, no schools have anything decent as far as diversity requirements, maybe challenge yourself to take classes on diversity!

The fifth thing I have on this list is to start a project or blog. Blogging on Tumblr is really one of the first ways I got really involved in feminist activism and I can’t even tell you how much all of my projects and writing have helped me to grow immensely in my feminism.

Taking on something like this not only forces you to gain a new perspective, but it also allows you to tap into a network of feminist bloggers and activists and it can really be a great way to meet other feminists and likeminded people who are maybe in your community, or maybe just people that you can connect with and learn from.

There are opportunities to learn and grow all around you and I think using your skills and your talents and doing something feminist with it is a great way to make it a part of your life!

The last thing I have on this list is to do an internship! Especially if you’re in school, you can get credit from an internship. Or if you’re a recent college graduate, internships can be a great way to get A) professional experience, and B) to learn and gain knowledge in something that you’re interested in.

I have done quite a bit of interning and it’s really helped me to learn how to apply feminism to areas and skill sets that aren’t necessarily associated with it because really any job can turn into a feminist job. You’re using your skill sets and what you’ve studied and taking a feminist approach into applying that.

For example, a lot of my work has been in social media, which isn’t in and of itself something that’s feminist, but it can really easily be applied to feminist work.

One thing I would suggest, if you’re looking for a feminist internship is don’t limit yourself to purely “feminist” positions, but look for positions that might have a feminist philosophy. For example, a lot of youth-based work is defined in this way. Or something, like I said, that you can take your skill sets in and apply it to feminism.

Sites like idealist.org and TheFeministJobsBoard are really great places to start looking.

So I hope this was helpful! Applying feminism to your everyday life really isn’t as hard as it seems. But I can tell you that it’s definitely worth it, and it can change your life for the better.

Have a great week everyone, and I will see you soon!

[do_widget id=”text-101″]

Want to discuss this further? Visit our online forum and start a post!

Erin McKelle is a Contributing Writer for Everyday Feminism. She’s an e-activist, video blogger, student, and non-profit advocate and has launched several projects including Fearless Feminism and Consent is Sexy . In her spare time, Erin enjoys reading, writing bad poetry, drawing, politics and reality TV. You can visit her site here find her blogging at Fearless Feminism , Facts About Feminism , and Period Positive. Follow her on Twitter @ErinMckelle and read her articles here.

Search our 3000+ articles!

Read our articles about:.

Feminism 101 Racial Justice Trans & GNC LGBTQIA

Webinars & Online Trainings

Our online racial justice training

Used by hundreds of universities, non-profits, and businesses. Click to learn more

Most Read Articles

3 Reasons It’s Harmful to Use Mental Illnesses as Adjectives and Metaphors

6 Ways Asian Americans Can Tackle Anti-Black Racism in Their Families

Mental Illness and Sexism: What Calling Women ‘Crazy’ Actually Does

4 Reasons Anti-Feminist Women Hate Feminism (And What They’re Missing)

Does Your Daughter Know It’s Okay to Be Angry?

Here Are 20 Examples of Cissexism That We’ve Probably All Committed at Some Point

Why Exclusionary Racial Preferences Are Racist

Why saying “men are slaves to their sex drive” is insulting to men.

Too Queer for Your Binary: Everything You Need to Know and More About Non-Binary Identities

4 Reasons Why We Should Stop Stigmatizing Women’s Body Hair

I Am Queer, I Am Non-Binary, and I Don’t Know What It Means to Feel Safe in Public

Why We Really Need to Stop Rejecting Religious Feminists from the Movement

5 Amazing Love Scenes Where Pop Culture Got Consent Exactly Right

Why It’s Not Racist When People of Color Point Out White Supremacy in White People’s Actions

4 Ways to Be Gender Inclusive When Discussing Abortion

- Next »

Feminist Theory

Jo Ann Arinder

Feminist theory falls under the umbrella of critical theory, which in general have the purpose of destabilizing systems of power and oppression. Feminist theory will be discussed here as a theory with a lower case ‘t’, however this is not meant to imply that it is not a Theory or cannot be used as one, only to acknowledge that for some it may be a sub-genre of Critical Theory, while for others it stands alone. According to Egbert and Sanden (2020), some scholars see critical paradigms as extensions of the interpretivist, but there is also an emphasis on oppression and lived experience grounded in subjectivist epistemology.

The purpose of using a feminist lens is to enable the discovery of how people interact within systems and possibly offer solutions to confront and eradicate oppressive systems and structures. Feminist theory considers the lived experience of any person/people, not just women, with an emphasis on oppression. While there may not be a consensus on where feminist theory fits as a theory or paradigm, disruption of oppression is a core tenant of feminist work. As hooks (2000) states, “Simply put, feminism is a movement to end sexism, sexist exploitation and oppression. I liked this definition because it does not imply that men were the enemy” (p. viii).

Previous Studies

Marxism and socialism are key components in the heritage.of feminist theory. The origins of feminist theory can be found in the 18th century with growth in the 1970s’ and 1980s’ equality movements. According to Burton (2014), feminist theory has its roots in Marxism but specifically looks to Engles’ (1884) work as one possible starting point. Burton (2014) notes that, “Origin of the Family and commentaries on it were central texts to the feminist movement in its early years because of the felt need to understand the origins and subsequent development of the subordination of the female sex” (p. 2). Work in feminist theory, including research regarding gender equality, is ongoing.

Gender equality continues to be an issue today, and research into gender equality in education is still moving feminist theory forward. For example, Pincock’s (2017) study discusses the impact of repressive norms on the education of girls in Tanzania. The author states that, “…considerations of what empowerment looks like in relation to one’s sexuality are particularly important in relation to schooling for teenage girls as a route to expanding their agency” (p. 909). This consideration can be extended to any oppressed group within an educational setting and is not an area of inquiry relegated to the oppression of only female students. For example, non-binary students face oppression within educational systems and even male students can face barriers, and students are often still led towards what are considered “gender appropriate” studies. This creates a system of oppression that requires active work to disrupt.

Looking at representation in the literature used in education is another area of inquiry in feminist research. For example, Earles (2017) focused on physical educational settings to explore relationships “between gendered literary characters and stories and the normative and marginal responses produced by children” (p. 369). In this research, Earles found evidence to support that a contradiction between the literature and children’s lived experiences exists. The author suggests that educators can help to continue the reduction of oppressive gender norms through careful selection of literature and spaces to allow learners opportunities for appropriate discussions about these inconsistencies.

In another study, Mackie (1999) explored incorporating feminist theory into evaluation research. Mackie was evaluating curriculum created for English language learners that recognized the dual realities of some students, also known as the intersectionality of identity, and concluded that this recognition empowered students. Mackie noted that valuing experience and identity created a potential for change on an individual and community level and “Feminist and other types of critical teaching and research provide needed balance to TESL and applied linguistics” (p. 571).Further, Bierema and Cseh (2003) used a feminist research framework to examine previously ignored structural inequalities that affect the lives of women working in the field of human resources.

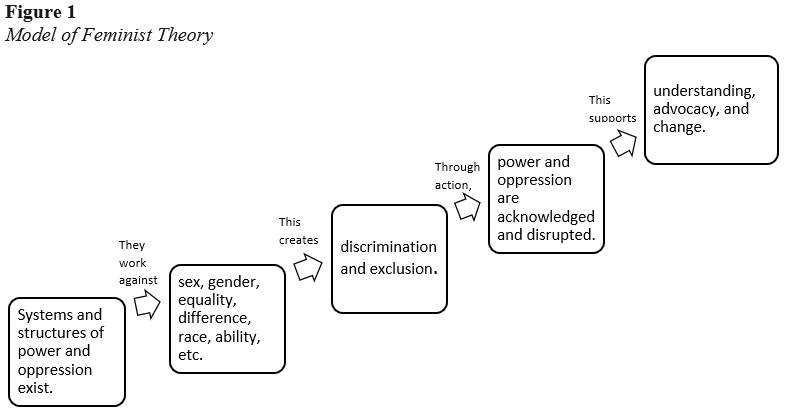

Model of Feminist Theory

Figure 1 presents a model of feminist theory that begins with the belief that systems exist that oppress and work against individuals. The model then shows that oppression is based on intersecting identities that can create discrimination and exclusion. The model indicates the idea that, through knowledge and action, oppressive systems can be disrupted to support change and understanding.

The core concepts in feminist theory are sex, gender, race, discrimination, equality, difference, and choice. There are systems and structures in place that work against individuals based on these qualities and against equality and equity. Research in critical paradigms requires the belief that, through the exploration of these existing conditions in the current social order, truths can be revealed. More important, however, this exploration can simultaneously build awareness of oppressive systems and create spaces for diverse voices to speak for themselves (Egbert & Sanden, 2019).

Constructs

Feminism is concerned with the constructs of intersectionality, dimensions of social life, social inequality, and social transformation. Through feminist research, lasting contributions have been made to understanding the complexities and changes in the gendered division of labor. Men and women should be politically, economically, and socially equal and this theory does not subscribe to differences or similarities between men, nor does it refer to excluding men or only furthering women’s causes. Feminist theory works to support change and understanding through acknowledging and disrupting power and oppression.

Proposition

Feminist theory proposes that when power and oppression are acknowledged and disrupted, understanding, advocacy, and change can occur.

Using the Model