95 Theses Against Indulgences (English text)

Dublin Core

Description, contributor.

- ← Previous Item

- Next Item →

The 95 Theses: A reader’s guide

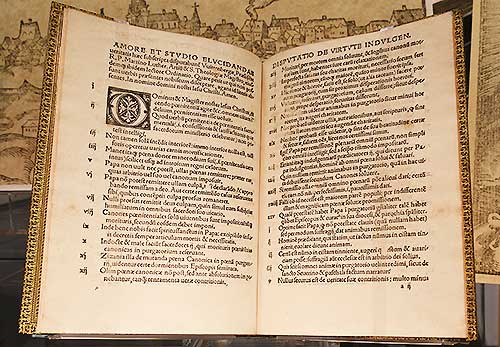

![95 Theses Luther's 95 Theses. c. 1557 [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://blogs.lcms.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/95_Thesen_Erste_Seite_banner-1.jpg)

by Kevin Armbrust

October 2017 marks the 500th anniversary of the Lutheran Reformation. Yet it is not the anniversary of any great statement Luther made as a reformer or in front of any court. There was no fiery and resounding speech given or dramatic showdown with the pope. On October 31, 1517, Martin Luther posted the “Disputation on the Power and Efficacy of Indulgences” to the church door in a small city called Wittenberg, Germany. This rather mundane academic document contained 95 theses for debate. Luther was a professor of theology at the University of Wittenberg, and he was permitted to call for public theological debate to discuss ideas and interpretations as he desired.

Yet this debate was not merely academic for Luther. According to a letter he wrote to the Archbishop of Mainz explaining the posting of the 95 Theses, Luther also desired to debate the concerns in the Theses for the sake of conscience.

Luther’s short preface explains:

“Out of love and zeal for truth and the desire to bring it to light, the following theses will be publicly discussed at Wittenberg under the chairmanship of the reverend father Martin Luther, Master of Arts and Sacred Theology and regularly appointed Lecturer on these subjects at that place. He requests that those who cannot be present to debate orally with us will do so by letter.”

The original text of the 95 Theses was written in Latin, since that was the academic language of Luther’s day. Luther’s theses were quickly translated into German, published in pamphlet form and spread throughout Germany.

Though English translations are readily available , many have found the 95 Theses difficult to read and comprehend. The short primer that follows may assist to highlight some of the theses and concepts Luther wished to explore.

Repentance and forgiveness dominate the content of the Theses. Since the question for Luther was the effectiveness of indulgences, he drove the discussion to the consideration of repentance and forgiveness in Christ. The first three theses address this:

1. When our Lord and Master Jesus Christ said, “Repent” [MATT. 4:17], he willed the entire life of believers to be one of repentance.

2. This word cannot be understood as referring to the sacrament of penance, that is, confession and satisfaction, as administered by the clergy.

3. Yet it does not mean solely inner repentance; such inner repentance is worthless unless it produces various outward mortifications of the flesh.

The pope and the Church cannot cause true repentance in a Christian and cannot forgive the sins of one who is guilty before Christ. The pope can only forgive that which Christ forgives. True repentance and eternal forgiveness come from Christ alone.

Luther identifies indulgences as a doctrine invented by man, since there is no scriptural promise or command for indulgences. Although Luther stops short of entirely condemning indulgences in the Theses, he nonetheless argues that the sale of indulgences and the trust in indulgences for salvation condemns both those who teach such notions and those who trust in them.

27. They preach only human doctrines who say that as soon as the money clinks into the money chest, the soul flies out of purgatory.

28. Those who believe that they can be certain of their salvation because they have indulgence letters will be eternally damned, together with their teachers.

God’s grace comes not through indulgences but through Christ. All Christians receive the blessings of God apart from indulgence letters.

36. Any truly repentant Christian has a right to full remission of penalty and guilt, even without indulgence letters.

37. Any true Christian, whether living or dead, participates in all the blessings of Christ and the church; and this is granted him by God, even without indulgence letters.

If Christians are going to spend money on something other than supporting their families, they should take care of the poor instead of buying indulgences.

43. Christians are to be taught that he who gives to the poor or lends to the needy does a better deed than he who buys indulgences.

The second half of the 95 Theses concentrates on the preaching of the true Word of the Gospel. Luther states that the teaching of indulgences should be lessened so that there might be more time for the proclamation of the true Gospel.

62. The true treasure of the church is the most holy gospel of the glory and grace of God.

63. But this treasure is naturally most odious, for it makes the first to be last [MATT. 20:16].

The Gospel of Christ is the true power for salvation (ROM. 1:16), not indulgences or even the power of the papal office.

76. We say on the contrary that papal indulgences cannot remove the very least of venial sins as far as guilt is concerned.

77. To say that even St. Peter, if he were now pope, could not grant greater graces is blasphemy against St. Peter and the pope.

78. We say on the contrary that even the present pope, or any pope whatsoever, has greater graces at his disposal, that is, the gospel, spiritual powers, gifts of healing, etc., as it is written in I Cor. 12[:28].

Preaching a false hope is really no hope at all. As a matter of fact, a false hope destroys and kills because it moves people away from Christ, where true salvation is found. The Gospel is found in Christ alone, which includes a cross and tribulations both large and small.

92. Away then with all those prophets who say to the people of Christ, “Peace, peace,” and there is no peace! [JER. 6:14].

93. Blessed be all those prophets who say to the people of Christ, “Cross, cross,” and there is no cross!

94. Christians should be exhorted to be diligent in following Christ, their head, through penalties, death, and hell;

95. And thus be confident of entering into heaven through many tribulations rather than through the false security of peace [ACTS 14:22].

Throughout the 95 Theses, Luther seeks to balance the role of the Church with the truth of the Gospel. Even as he desired to support the pope and his role in the Church, the false teaching of indulgences and the pope’s unwillingness to freely forgive the sins of all repentant Christians compelled him to speak up against these abuses.

Luther’s pastoral desire for all to trust in Christ alone for salvation drove him to post the 95 Theses. This same faith and hope sparked the Reformation that followed.

Dr. Kevin Armbrust is manager of editorial services for LCMS Communications.

Related Posts

How did Luther become a Lutheran?

Laughing with Luther

Luther alone?

About the author.

Kevin Armbrust

11 thoughts on “the 95 theses: a reader’s guide”.

Thx. This article does clear up a number of difficulties in interpreting the drift & theme of the 95 thesis. The fact that he supports the pope’s office at this juncture is new to me.

Very useful as I prepare a Sunday School lesson. Thanks

As important as the 95 Theses were for the beginning of the Reformation, and since they are not specifically part of the Lutheran Confessions, are there any of the Theses that we Lutherans consider unimportant or would rather avoid, theologically speaking?

I wish Luther was here, maybe things would change in our country and bring more folks to Jesus .

“When our Lord and master Jesus Christ says, ‘Repent,’ he wills that the entire life of the Christian be one of repentance.”

This seemingly joyless statement is often quoted, less often explained, and easily misunderstood. Is Jesus calling for the main theme of Christian life to be, “I’m ashamed of my sin”?

The full sentence from Matthew 4:17 is, “Repent, for the kingdom of heaven is at hand,” spoken when Jesus was beginning His ministry. This layman might paraphrase those words as, “Change your mindset, for divine authority is coming among you.” Indeed, when a very important person is coming to visit, we depart from business as usual, adjust our priorities, focus on careful preparation, and behave as befits the status of the visitor.

The word “repent” is recorded in Greek as “metanoeite”, which I understand to be not about remorse — not primarily about feelings at all — but about changing one’s mind or purpose.

The Christian life has a variety of themes, of which repentance is one. But repentance is not an end in itself. It is pivoting and changing course to pursue a direction that better fulfills God’s purposes as He gives the grace. For Jesus also willed “that you bear much fruit” (John 15:8) and “that your joy may be full” (John 15:11).

Could you explain number 93? I need this one explained. Jackie

Agreed. 93 is confusing.

In contrast to the false security of indulgences referenced in 92, number 93 references the preaching of true repentance. With true contrition and repentance over our sins, we Christians humble ourselves to the truth that we have earned our place on the cross as punishment and condemnation. But then we find the eternal surprise and wellspring of joy that our cross has been taken away from us and made Christ’s own. In exchange He gives us forgiveness, life and salvation!

Thank you, James Athey.

I myself did not fully understand this thesis yesterday, when I searched the Internet for an explanation of it. I found that I was not the only person who was confused by it. I also found that Luther explained it in a letter that he wrote to an Augustinian prior in 1516. Here is his explanation:

You are seeking and craving for peace, but in the wrong order. For you are seeking it as the world giveth, not as Christ giveth. Know you not that God is “wonderful among His saints,” for this reason, that He establishes His peace in the midst of no peace, that is, of all temptations and afflictions. It is said “Thou shalt dwell in the midst of thine enemies.” The man who possesses peace is not the man whom no one disturbs—that is the peace of the world; he is the man whom all men and all things disturb, but who bears all patiently, and with joy. You are saying with Israel, “Peace, peace,” and there is no peace. Learn to say rather with Christ: “The Cross, the Cross,” and there is no Cross. For the Cross at once ceases to be the Cross as soon as you have joyfully exclaimed, in the language of the hymn,

Blessed Cross, above all other, One and only noble tree.

It is posted here: http://www.ccel.org/ccel/luther/first_prin.iii.i.html

Magnificent!

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

More results...

The 95 Theses – a modern translation

1. When Jesus said “repent” he meant that believers should live a whole life repenting

2. Only God can give salvation – not a priest.

3. Inwards penitence must be accompanied with a suitable change in lifestyle.

4. Sin will always remain until we enter Heaven.

5. The pope must act according to canon law.

6. Only God can forgive -the pope can only reassure people that God will do this.

7. A sinner must be humbled in front of his priest before God can forgive him.

8. Canon law applies only to the living not to the dead.

9. However, the Holy Spirit will make exceptions to this when required to do so.

10. The priest must not threaten those dying with the penalty of purgatory.

11. The church through church penalties is producing a ‘human crop of weeds’.

12. In days gone by, church penalties were imposed before release from guilt to show true repentance.

13. When you die all your debts to the church are wiped out and those debts are free from being judged.

14. When someone is dying they might have bad/incorrect thoughts against the church and they will be scared. This fear is enough penalty.

15. This fear is so bad that it is enough to cleanse the soul.

16. Purgatory = Hell. Heaven = Assurance.

17. Souls in Purgatory need to find love – the more love the less their sin.

18. A sinful soul does not have to be always sinful. It can be cleansed.

19. There is no proof that a person is free from sin.

20. Even the pope – who can offer forgiveness – cannot totally forgive sins held within.

21. An indulgence will not save a man.

22. A dead soul cannot be saved by an indulgence.

23. Only a very few sinners can be pardoned. These people would have to be perfect.

24. Therefore most people are being deceived by indulgences.

25. The pope’s power over Purgatory is the same as a priest’s.

26. When the pope intervenes to save an individual, he does so by the will of God.

27. It is nonsense to teach that a dead soul in Purgatory can be saved by money.

28. Money causes greed – only God can save souls.

29. Do we know if the souls in Purgatory want to be saved ?

30. No-one is sure of the reality of his own penitence – no-one can be sure of receiving complete forgiveness.

31. A man who truly buys an indulgence (ie believes it is to be what it is) is as rare as someone who truly repents all sin ie very rare.

32. People who believe that indulgences will let them live in salvation will always be damned – along with those who teach it.

33. Do not believe those who say that a papal indulgence is a wonderful gift which allows salvation.

34. Indulgences only offer Man something which has been agreed to by Man.

35. We should not teach that those who aim to buy salvation do not need to be contrite.

36. A man can be free of sin if he sincerely repents – an indulgence is not needed.

37. Any Christian – dead or alive – can gain the benefit and love of Christ without an indulgence.

38. Do not despise the pope’s forgiveness but his forgiveness is not the most important.

39. The most educated theologians cannot preach about indulgences and real repentance at the same time.

40. A true repenter will be sorry for his sins and happily pay for them. Indulgences trivialise this issue.

41. If a pardon is given it should be given cautiously in case people think it’s more important than doing good works.

42. Christians should be taught that the buying of indulgences does not compare with being forgiven by Christ.

43. A Christian who gives to the poor or lends to those in need is doing better in God’s eyes than one who buys ‘forgiveness’.

44. This is because of loving others, love grows and you become a better person. A person buying an indulgence does not become a better person.

45. A person who passes by a beggar but buys an indulgence will gain the anger and disappointment of God.

46. A Christian should buy what is necessary for life not waste money on an indulgence.

47. Christians should be taught that they do not need an indulgence.

48. The pope should have more desire for devout prayer than for ready money.

49. Christians should be taught not to rely on an indulgence. They should never lose their fear of God through them.

50. If a pope knew how much people were being charged for an indulgence – he would prefer to demolish St. Peter’s.

51. The pope should give his own money to replace that which is taken from pardoners.

52. It is vain to rely on an indulgence to forgive your sins.

53. Those who forbid the word of God to be preached and who preach pardons as a norm are enemies of both the pope and Christ.

54. It is blasphemy that the word of God is preached less than that of indulgences.

55. The pope should enforce that the gospel – a very great matter – must be celebrated more than indulgences.

56. The treasure of the church is not sufficiently known about among the followers of Christ.

57. The treasure of the Church are temporal (of this life).

58. Relics are not the relics of Christ, although they may seem to be. They are, in fact, evil in concept.

59. St. Laurence misinterpreted this as the poor gave money to the church for relics and forgiveness.

60. Salvation can be sought for through the church as it has been granted this by Christ.

61. It is clear that the power of the church is adequate, by itself, for the forgiveness of sins.

62. The main treasure of the church should be the Gospels and the grace of God.

63. Indulgences make the most evil seem unjustly good.

64. Therefore evil seems good without penance or forgiveness.

65. The treasured items in the Gospels are the nets used by the workers.

66. Indulgences are used to net an income for the wealthy.

67. It is wrong that merchants praise indulgences.

68. They are the furthest from the grace of God and the piety and love of the cross.

69. Bishops are duty bound to sell indulgences and support them as part of their job.

70. But bishops are under a much greater obligation to prevent men preaching their own dreams.

71. People who deny the pardons of the Apostles will be cursed.

72. Blessed are they who think about being forgiven.

73. The pope is angered at those who claim that pardons are meaningless.

74. He will be even more angry with those who use indulgences to criticise holy love.

75. It is wrong to think that papal pardons have the power to absolve all sin.

76. You should feel guilt after being pardoned. A papal pardon cannot remove guilt.

77. Not even St. Peter could remove guilt.

78. Even so, St. Peter and the pope possess great gifts of grace.

79. It is blasphemy to say that the insignia of the cross is of equal value with the cross of Christ.

80. Bishops who authorise such preaching will have to answer for it.

81. Pardoners make the intelligent appear disrespectful because of the pope’s position.

82. Why doesn’t the pope clean feet for holy love not for money ?

83. Indulgences bought for the dead should be re-paid by the pope.

84. Evil men must not buy their salvation when a poor man, who is a friend of God, cannot.

85. Why are indulgences still bought from the church ?

86. The pope should re-build St. Peter’s with his own money.

87. Why does the pope forgive those who serve against him ?

88. What good would be done to the church if the pope was to forgive hundreds of people each day ?

89. Why are indulgences only issued when the pope sees fit to issue them ?

90. To suppress the above is to expose the church for what it is and to make true Christians unhappy.

91. If the pope had worked as he should (and by example) all the problems stated above would not have existed.

92. All those who say there is no problem must go. Problems must be tackled.

93. Those in the church who claim there is no problem must go.

94. Christians must follow Christ at all cost.

95. Let Christians experience problems if they must – and overcome them – rather than live a false life based on present Catholic teaching.

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Martin Luther and the 95 Theses

By: History.com Editors

Updated: June 6, 2019 | Original: October 29, 2009

Born in Eisleben, Germany, in 1483, Martin Luther went on to become one of Western history’s most significant figures. Luther spent his early years in relative anonymity as a monk and scholar. But in 1517 Luther penned a document attacking the Catholic Church’s corrupt practice of selling “indulgences” to absolve sin. His “95 Theses,” which propounded two central beliefs—that the Bible is the central religious authority and that humans may reach salvation only by their faith and not by their deeds—was to spark the Protestant Reformation. Although these ideas had been advanced before, Martin Luther codified them at a moment in history ripe for religious reformation. The Catholic Church was ever after divided, and the Protestantism that soon emerged was shaped by Luther’s ideas. His writings changed the course of religious and cultural history in the West.

Martin Luther (1483–1546) was born in Eisleben, Saxony (now Germany), part of the Holy Roman Empire, to parents Hans and Margaretta. Luther’s father was a prosperous businessman, and when Luther was young, his father moved the family of 10 to Mansfeld. At age five, Luther began his education at a local school where he learned reading, writing and Latin. At 13, Luther began to attend a school run by the Brethren of the Common Life in Magdeburg. The Brethren’s teachings focused on personal piety, and while there Luther developed an early interest in monastic life.

Did you know? Legend says Martin Luther was inspired to launch the Protestant Reformation while seated comfortably on the chamber pot. That cannot be confirmed, but in 2004 archeologists discovered Luther's lavatory, which was remarkably modern for its day, featuring a heated-floor system and a primitive drain.

Martin Luther Enters the Monastery

But Hans Luther had other plans for young Martin—he wanted him to become a lawyer—so he withdrew him from the school in Magdeburg and sent him to new school in Eisenach. Then, in 1501, Luther enrolled at the University of Erfurt, the premiere university in Germany at the time. There, he studied the typical curriculum of the day: arithmetic, astronomy, geometry and philosophy and he attained a Master’s degree from the school in 1505. In July of that year, Luther got caught in a violent thunderstorm, in which a bolt of lightning nearly struck him down. He considered the incident a sign from God and vowed to become a monk if he survived the storm. The storm subsided, Luther emerged unscathed and, true to his promise, Luther turned his back on his study of the law days later on July 17, 1505. Instead, he entered an Augustinian monastery.

Luther began to live the spartan and rigorous life of a monk but did not abandon his studies. Between 1507 and 1510, Luther studied at the University of Erfurt and at a university in Wittenberg. In 1510–1511, he took a break from his education to serve as a representative in Rome for the German Augustinian monasteries. In 1512, Luther received his doctorate and became a professor of biblical studies. Over the next five years Luther’s continuing theological studies would lead him to insights that would have implications for Christian thought for centuries to come.

Martin Luther Questions the Catholic Church

In early 16th-century Europe, some theologians and scholars were beginning to question the teachings of the Roman Catholic Church. It was also around this time that translations of original texts—namely, the Bible and the writings of the early church philosopher Augustine—became more widely available.

Augustine (340–430) had emphasized the primacy of the Bible rather than Church officials as the ultimate religious authority. He also believed that humans could not reach salvation by their own acts, but that only God could bestow salvation by his divine grace. In the Middle Ages the Catholic Church taught that salvation was possible through “good works,” or works of righteousness, that pleased God. Luther came to share Augustine’s two central beliefs, which would later form the basis of Protestantism.

Meanwhile, the Catholic Church’s practice of granting “indulgences” to provide absolution to sinners became increasingly corrupt. Indulgence-selling had been banned in Germany, but the practice continued unabated. In 1517, a friar named Johann Tetzel began to sell indulgences in Germany to raise funds to renovate St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome.

The 95 Theses

Committed to the idea that salvation could be reached through faith and by divine grace only, Luther vigorously objected to the corrupt practice of selling indulgences. Acting on this belief, he wrote the “Disputation on the Power and Efficacy of Indulgences,” also known as “The 95 Theses,” a list of questions and propositions for debate. Popular legend has it that on October 31, 1517 Luther defiantly nailed a copy of his 95 Theses to the door of the Wittenberg Castle church. The reality was probably not so dramatic; Luther more likely hung the document on the door of the church matter-of-factly to announce the ensuing academic discussion around it that he was organizing.

The 95 Theses, which would later become the foundation of the Protestant Reformation, were written in a remarkably humble and academic tone, questioning rather than accusing. The overall thrust of the document was nonetheless quite provocative. The first two of the theses contained Luther’s central idea, that God intended believers to seek repentance and that faith alone, and not deeds, would lead to salvation. The other 93 theses, a number of them directly criticizing the practice of indulgences, supported these first two.

In addition to his criticisms of indulgences, Luther also reflected popular sentiment about the “St. Peter’s scandal” in the 95 Theses:

Why does not the pope, whose wealth today is greater than the wealth of the richest Crassus, build the basilica of St. Peter with his own money rather than with the money of poor believers?

The 95 Theses were quickly distributed throughout Germany and then made their way to Rome. In 1518, Luther was summoned to Augsburg, a city in southern Germany, to defend his opinions before an imperial diet (assembly). A debate lasting three days between Luther and Cardinal Thomas Cajetan produced no agreement. Cajetan defended the church’s use of indulgences, but Luther refused to recant and returned to Wittenberg.

Luther the Heretic

On November 9, 1518 the pope condemned Luther’s writings as conflicting with the teachings of the Church. One year later a series of commissions were convened to examine Luther’s teachings. The first papal commission found them to be heretical, but the second merely stated that Luther’s writings were “scandalous and offensive to pious ears.” Finally, in July 1520 Pope Leo X issued a papal bull (public decree) that concluded that Luther’s propositions were heretical and gave Luther 120 days to recant in Rome. Luther refused to recant, and on January 3, 1521 Pope Leo excommunicated Martin Luther from the Catholic Church.

On April 17, 1521 Luther appeared before the Diet of Worms in Germany. Refusing again to recant, Luther concluded his testimony with the defiant statement: “Here I stand. God help me. I can do no other.” On May 25, the Holy Roman emperor Charles V signed an edict against Luther, ordering his writings to be burned. Luther hid in the town of Eisenach for the next year, where he began work on one of his major life projects, the translation of the New Testament into German, which took him 10 months to complete.

Martin Luther's Later Years

Luther returned to Wittenberg in 1521, where the reform movement initiated by his writings had grown beyond his influence. It was no longer a purely theological cause; it had become political. Other leaders stepped up to lead the reform, and concurrently, the rebellion known as the Peasants’ War was making its way across Germany.

Luther had previously written against the Church’s adherence to clerical celibacy, and in 1525 he married Katherine of Bora, a former nun. They had five children. At the end of his life, Luther turned strident in his views, and pronounced the pope the Antichrist, advocated for the expulsion of Jews from the empire and condoned polygamy based on the practice of the patriarchs in the Old Testament.

Luther died on February 18, 1546.

Significance of Martin Luther’s Work

Martin Luther is one of the most influential figures in Western history. His writings were responsible for fractionalizing the Catholic Church and sparking the Protestant Reformation. His central teachings, that the Bible is the central source of religious authority and that salvation is reached through faith and not deeds, shaped the core of Protestantism. Although Luther was critical of the Catholic Church, he distanced himself from the radical successors who took up his mantle. Luther is remembered as a controversial figure, not only because his writings led to significant religious reform and division, but also because in later life he took on radical positions on other questions, including his pronouncements against Jews, which some have said may have portended German anti-Semitism; others dismiss them as just one man’s vitriol that did not gain a following. Some of Luther’s most significant contributions to theological history, however, such as his insistence that as the sole source of religious authority the Bible be translated and made available to everyone, were truly revolutionary in his day.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

Luther's 95 theses

An extremely rare document, this is a copy of the first printing of Martin Luther’s 95 theses as a pamphlet. 'Disputatio … pro declaratione virtutis indugentiarum', by Martin Luther (Basel, 1517).

Martin Luther 's attention in his 95 theses of 1517 focused on the Church's sale of indulgences.

Selling full or partial remission of the punishment for sin was a lucrative source of income for the Pope and his administration by the 16th century.

While criticism of the practice was not unusual, the tumultuous impact of Luther's 95 theses was unexpected.

He had written and made them public to start off an academic debate. Once he translated them into German, however, the theses gained widespread popularity.

Distributed across Europe

As posters and pamphlets, the theses were printed and distributed across the Holy Roman Empire's territories in northern and central Europe.

Of the few hundred copies printed, those produced in Nuremberg and Leipzig were issued as posters, those in Basel as pamphlets.

Luther's introduction

The 95 theses are introduced with the following words:

'Out of love for the truth and from desire to elucidate it, the Reverend Father Martin Luther, Master of Arts and Sacred Theology, and ordinary lecturer therein at Wittenberg, intends to defend the following statements and to dispute on them in that place.

The academic disputation never took place, but Luther's theses sparked the Reformation.

A copy of the first edition of Luther's 95 theses is one of the highlights of the display 'The Reformation: What was it all about?' at the National Library from 19 October to 10 December 2017.

'The Reformation'

Our site uses cookies to help give you the best online experience. Please let us know if you happy for us to use these cookies or if you wish minimum functionality only.

- Featured Essay The Love of God An essay by Sam Storms Read Now

- Faithfulness of God

- Saving Grace

- Adoption by God

Most Popular

- Gender Identity

- Trusting God

- The Holiness of God

- See All Essays

- Conference Media

- Featured Essay Resurrection of Jesus An essay by Benjamin Shaw Read Now

- Death of Christ

- Resurrection of Jesus

- Church and State

- Sovereignty of God

- Faith and Works

- The Carson Center

- The Keller Center

- New City Catechism

- Publications

- Read the Bible

U.S. Edition

- Arts & Culture

- Bible & Theology

- Christian Living

- Current Events

- Faith & Work

- As In Heaven

- Gospelbound

- Post-Christianity?

- TGC Podcast

- You're Not Crazy

- Churches Planting Churches

- Help Me Teach The Bible

- Word Of The Week

- Upcoming Events

- Past Conference Media

- Foundation Documents

- Church Directory

- Global Resourcing

- Donate to TGC

To All The World

The world is a confusing place right now. We believe that faithful proclamation of the gospel is what our hostile and disoriented world needs. Do you believe that too? Help TGC bring biblical wisdom to the confusing issues across the world by making a gift to our international work.

Luther’s Ninety-five Theses: What You May Not Know and Why They Matter Today

More By Justin Holcomb

For more accessible overviews of key moments in church history, purchase Justin Holcomb’s new book, Know the Creeds and Councils (Zondervan, 2014) [ interview ]. Additionally, Holcomb has made available to TGC readers an exclusive bonus chapter, which can be accessed here . This article is a shortened version of the chapter.

If people know only one thing about the Protestant Reformation, it is the famous event on October 31, 1517, when the Ninety-five Theses of Martin Luther (1483–1586) were nailed on the door of the Castle Church of Wittenberg in protest against the Roman Catholic Church. Within a few years of this event, the church had splintered into not just the “church’s camp” or “Luther’s camp” but also the camps of churches led by theologians of all different stripes.

Luther is known mostly for his teachings about Scripture and justification. Regarding Scripture, he argued the Bible alone ( sola scriptura ) is our ultimate authority for faith and practice. Regarding justification, he taught we are saved solely through faith in Jesus Christ because of God’s grace and Christ’s merit. We are neither saved by our merits nor declared righteous by our good works. Additionally, we need to fully trust in God to save us from our sins, rather than relying partly on our own self-improvement.

Forgiveness with a Price Tag

These teachings were radical departures from the Catholic orthodoxy of Luther’s day. But you might be surprised to learn that the Ninety-five Theses, even though this document that sparked the Reformation, was not about these issues. Instead, Luther objected to the fact that the Roman Catholic Church was offering to sell certificates of forgiveness, and that by doing so it was substituting a false hope (that forgiveness can be earned or purchased) for the true hope of the gospel (that we receive forgiveness solely via the riches of God’s grace).

The Roman Catholic Church claimed it had been placed in charge of a “treasury of merits” of all of the good deeds that saints had done (not to mention the deeds of Christ, who made the treasury infinitely deep). For those trapped by their own sinfulness, the church could write a certificate transferring to the sinner some of the merits of the saints. The catch? These “indulgences” had a price tag.

This much needs to be understood to make sense of Luther’s Ninety-five Theses: the selling of indulgences for full remission of sins intersected perfectly with the long, intense struggle Luther himself had experienced over the issues of salvation and assurance. At this point of collision between one man’s gospel hope and the church’s denial of that hope the Ninety-five Theses can be properly understood.

Theses Themselves

Luther’s Ninety-five Theses focuses on three main issues: selling forgiveness (via indulgences) to build a cathedral, the pope’s claimed power to distribute forgiveness, and the damage indulgences caused to grieving sinners. That his concern was pastoral (rather than trying to push a private agenda) is apparent from the document. He didn’t believe (at this point) that indulgences were altogether a bad idea; he just believed they were misleading Christians regarding their spiritual state:

41. Papal indulgences must be preached with caution, lest people erroneously think that they are preferable to other good works of love.

As well as their duty to others:

43. Christians are to be taught that he who gives to the poor or lends to the needy does a better deed than he who buys indulgences.

44. Because love grows by works of love, man thereby becomes better. Man does not, however, become better by means of indulgences but is merely freed from penalties. [Notice that Luther is not yet wholly against the theology of indulgences.]

And even financial well-being:

46. Christians are to be taught that, unless they have more than they need, they must reserve enough for their family needs and by no means squander it on indulgences.

Luther’s attitude toward the pope is also surprisingly ambivalent. In later years he called the pope “the Antichrist” and burned his writings, but here his tone is merely cautionary, hoping the pope will come to his senses. For instance, in this passage he appears to be defending the pope against detractors, albeit in a backhanded way:

51. Christians are to be taught that the pope would and should wish to give of his own money, even though he had to sell the basilica of St. Peter, to many of those from whom certain hawkers of indulgences cajole money.

Obviously, since Leo X had begun the indulgences campaign in order to build the basilica, he did not “wish to give of his own money” to victims. However, Luther phrased his criticism to suggest that the pope might be ignorant of the abuses and at any rate should be given the benefit of the doubt. It provided Leo a graceful exit from the indulgences campaign if he wished to take it.

So what made this document so controversial? Luther’s Ninety-five Theses hit a nerve in the depths of the authority structure of the medieval church. Luther was calling the pope and those in power to repent—on no authority but the convictions he’d gained from Scripture—and urged the leaders of the indulgences movement to direct their gaze to Christ, the only one able to pay the penalty due for sin.

Of all the portions of the document, Luther’s closing is perhaps the most memorable for its exhortation to look to Christ rather than to the church’s power:

92. Away, then, with those prophets who say to Christ’s people, “Peace, peace,” where in there is no peace.

93. Hail, hail to all those prophets who say to Christ’s people, “The cross, the cross,” where there is no cross.

94. Christians should be exhorted to be zealous to follow Christ, their Head, through penalties, deaths, and hells.

95. And let them thus be more confident of entering heaven through many tribulations rather than through a false assurance of peace.

In the years following his initial posting of the theses, Luther became emboldened in his resolve and strengthened his arguments with Scripture. At the same time, the church became more and more uncomfortable with the radical Luther and, in the following decades, the spark that he made grew into a flame of reformation that spread across Europe. Luther was ordered by the church to recant in 1520 and was eventually exiled in 1521.

Ongoing Relevance

Although the Ninety-five Theses doesn’t explicitly lay out a Protestant theology or agenda, it contains the seeds of the most important beliefs of the movement, especially the priority of grasping and applying the gospel. Luther developed his critique of the Roman Catholic Church out of his struggle with doubt and guilt as well as his pastoral concern for his parishioners. He longed for the hope and security that only the good news can bring, and he was frustrated with the structures that were using Christ to take advantage of people and prevent them from saving union with God. Further, Luther’s focus on the teaching of Scripture is significant, since it provided the foundation on which the great doctrines of the Reformation found their origin.

Indeed, Luther developed a robust notion of justification by faith and rejected the notion of purgatory as unbiblical; he argued that indulgences and even hierarchical penance cannot lead to salvation; and, perhaps most notably, he rebelled against the authority of the pope. All of these critiques were driven by Luther’s commitment, above all else, to Christ and the Scriptures that testify about him. The outspoken courage Luther demonstrated in writing and publishing the Ninety-five Theses also spread to other influential leaders of the young Protestant Reformation.

Today, the Ninety-five Theses may stand as the most well-known document from the Reformation era. Luther’s courage and his willingness to confront what he deemed to be clear error is just as important today as it was then. One of the greatest ways in which Luther’s theses affect us today—in addition to the wonderful inheritance of the five Reformation solas (Scripture alone, grace alone, faith alone, Christ alone, glory to God alone)—is that it calls us to thoroughly examine the inherited practices of the church against the standard set forth in the Scriptures. Luther saw an abuse, was not afraid to address it, and was exiled as a result of his faithfulness to the Bible in the midst of harsh opposition.

Is there enough evidence for us to believe the Gospels?

Justin Holcomb is an Episcopal priest and a theology professor at Reformed Theological Seminary and Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary. He is author with his wife, Lindsey, of God Made All of Me , Is It My Fault? , and Rid of My Disgrace: Hope and Healing for Victims of Sexual Assault . Justin also has written or edited numerous other books on historical theology and biblical studies. You can find him on Facebook , Twitter , and at JustinHolcomb.com .

Now Trending

1 can i tell an unbeliever ‘jesus died for you’, 2 the faqs: southern baptists debate designation of women in ministry, 3 7 recommendations from my book stack, 4 artemis can’t undermine complementarianism, 5 ‘girls state’ highlights abortion’s role in growing gender divide.

The 11 Beliefs You Should Know about Jehovah’s Witnesses When They Knock at the Door

Here are the key beliefs of Jehovah’s Witnesses—and what the Bible really teaches instead.

8 Edifying Films to Watch This Spring

Easter Week in Real Time

Resurrected Saints and Matthew’s Weirdest Passage

I Believe in the Death of Julius Caesar and the Resurrection of Jesus Christ

Does 1 Peter 3:19 Teach That Jesus Preached in Hell?

The Plays C. S. Lewis Read Every Year for Holy Week

Latest Episodes

Lessons on evangelism from an unlikely evangelist.

Welcome and Witness: How to Reach Out in a Secular Age

How to Build Gospel Culture: A Q&A Conversation

Examining the Current and Future State of the Global Church

Trevin Wax on Reconstructing Faith

Gaming Alone: Helping the Generation of Young Men Captivated and Isolated by Video Games

Raise Your Kids to Know Their True Identity

Faith & Work: How Do I Glorify God Even When My Work Seems Meaningless?

Let’s Talk (Live): Growing in Gratitude

Getting Rid of Your Fear of the Book of Revelation

Looking for Love in All the Wrong Places: A Sermon from Julius Kim

Introducing The Acts 29 Podcast

EWTN News, Inc. is the world’s largest Catholic news organization, comprised of television, radio, print and digital media outlets, dedicated to reporting the truth in light of the Gospel and the Catholic Church.

- National Catholic Register

- News Agencies

- Catholic News Agency

- CNA Deutsch

- ACI Afrique

- ACI Digital

- Digital Media

- ChurchPOP Español

- ChurchPOP Italiano

- ChurchPOP Português

- EWTN News Indepth

- EWTN News Nightly

- EWTN Noticias

- EWTN Pro-life Weekly

- Register Radio

Get HALF OFF the Register!

National Catholic Register News https://www.ncregister.com/blog/the-95-theses-8-things-to-know-and-share

- Synod on Synodality

- Most Popular

- Publisher’s Note

- College Guide

- Commentaries

- Culture of Life

- Arts & Entertainment

- Publisher's Note

- Letters to the Editor

- Support the Register

- Print subscriptions

- E-Newsletter Sign-up

- EWTN Religious Catalogue

The 95 Theses: 8 Things to Know and Share

The 95 Theses deal principally with indulgences, purgatory, and the pope’s role with respect to the two.

In 1517, Martin Luther drafted a document known as The 95 Theses , and its publication is used to date the beginning of the Protestant Reformation.

The recent 500th anniversary of that event focused a good bit of attention on the 95 Theses.

Here are 8 things to know and share . . .

1) What are The 95 Theses ?

The 95 Theses are a set of propositions that Martin Luther proposed for academic debate. As the name indicates, there are 95 of them.

Despite the fact they played a key role in starting the Protestant Reformation, they do not deal with either of the main Protestant distinctives. They do not mention either justification by faith alone or doing theology by Scripture alone.

Instead, they deal principally with indulgences, purgatory, and the pope’s role with respect to the two.

2) Did Luther nail them to a church door?

Despite constant statements to the contrary, the answer appears to be no, he didn’t .

3) Are they all bad?

No, they’re not. It can come as a surprise to both Protestants and Catholics, but some of them agree with Catholic teaching.

Here are the first three of Luther’s theses, along with parallel statements from the Catechism of the Catholic Church :

Thesis 1: When our Lord and Master Jesus Christ said, “Repent” (Mt 4:17), he willed the entire life of believers to be one of repentance.

- CCC 1431: Interior repentance is a radical reorientation of our whole life, a return, a conversion to God with all our heart, an end of sin, a turning away from evil, with repugnance toward the evil actions we have committed.

Thesis 2: This word [i.e., Christ’s call to repent in Mark 4:17] cannot be understood as referring to the sacrament of penance, that is, confession and satisfaction, as administered by the clergy.

- CCC 1427: Jesus calls to conversion. This call is an essential part of the proclamation of the kingdom: “The time is fulfilled, and the kingdom of God is at hand; repent , and believe in the gospel” [Mark 4:17]. In the Church's preaching this call is addressed first to those who do not yet know Christ and his Gospel . Also, Baptism is the principal place for the first and) fundamental conversion.

Thesis 3: Yet it [i.e., the call to repent in Mark 4:17] does not mean solely inner repentance; such inner repentance is worthless unless it produces various outward mortification of the flesh.

- CCC 1430: Jesus' call to conversion and penance, like that of the prophets before him, does not aim first at outward works, “sackcloth and ashes,” fasting and mortification, but at the conversion of the heart, interior conversion. Without this, such penances remain sterile and false; however, interior conversion urges expression in visible signs, gestures, and works of penance .

4) How did the Church respond to The 95 Theses ?

In 1520, Pope Leo X published a bull known as Exsurge Domine (Latin, “Arise, Lord”) in which he rejected 41 propositions taken from the writings of Martin Luther up to that time.

However, only a few of the rejected propositions came from The 95 Theses . Most were based on things Luther said in other writings.

5) Which of The 95 Theses did Exsurge Domine reject?

The rejected propositions in Exsurge Domine are formulated from things Luther said, but they are not verbatim quotations.

Three of the rejected propositions—numbers 4, 17, and 38—are drawn from The 95 Theses . In each case, the rejected proposition is based on two of Luther’s original theses.

Here are the rejected propositions along with the corresponding theses:

Proposition 4. To one on the point of death, imperfect charity necessarily brings with it great fear, which in itself alone is enough to produce the punishment of purgatory and impedes entrance into the kingdom.

Thesis 14. Imperfect piety or love on the part of the dying person necessarily brings with it great fear; and the smaller the love, the greater the fear.

Thesis 15. This fear or horror is sufficient in itself, to say nothing of other things, to constitute the penalty of purgatory, since it is very near the horror of despair.

Proposition 17. The treasures of the Church from which the pope gives indulgences are not the merits of Christ and of the saints.

Thesis 56. The treasures of the church, out of which the pope distributes indulgences, are not sufficiently discussed or known among the people of Christ.

Thesis 58. Nor are they the merits of Christ and the saints, for, even without the pope, the latter always work grace for the inner man, and the cross, death, and hell for the outer man.

Proposition 38. The souls in purgatory are not sure of their salvation, at least (not) all; nor is it proved by any arguments or by the Scriptures that they are beyond the state of meriting or of increasing in charity.

Thesis 19. Nor does it seem proved that souls in purgatory, at least not all of them, are certain and assured of their own salvation, even if we ourselves may be entirely certain of it.

Thesis 18. Furthermore, it does not seem proved, either by reason or Scripture, that souls in purgatory are outside the state of merit, that is, unable to grow in love.

Exsurge Domine thus rejected things it saw expressed in theses 14, 15, 18, 19, 56, and 58.

6) What did Exsurge Domine say about the rejected propositions?

The bull closes with the following censure:

All and each of the above-mentioned articles or errors [i.e., all 41 of them], as set before you, we condemn, disapprove, and entirely reject as respectively heretical or ( aut ) scandalous or ( aut ) false or ( aut ) offensive to pious ears or ( vel ) seductive of simple minds and ( et ) in opposition to Catholic truth.

This kind of condemnation is sometimes referred to as an condemnation in globo (Latin, “as a whole”). They are rejected as a batch, but without indicating which censure applies to which proposition.

The condemnation has to be read with care because in Latin, aut indicates an exclusive “or” (i.e., this or that, but not both) while vel indicates an inclusive “or” (i.e., this or that, but possibly both).

Thus Exsurge Domine indicates that some of the 41 rejected propositions are heretical, some are scandalous, some are false, some are offensive to pious ears—but they are not all four.

The use of aut between these censures tells you that a given proposition may fall into one of these four categories.

The only time an inclusive “or” is used is before the fifth and sixth categories: Some propositions may be “seductive of simple minds and ( et ) in opposition to Catholic truth.” Here vel is used because things that are heretical (etc.) can also be seductive of simple minds (the fifth category) and obviously would be opposed to Catholic truth (the sixth category).

7) What does that mean for The 95 Theses ?

It means that Exsurge Domine rejected things expressed in Theses 14, 15, 18, 19, 56, and 58, and it thus warned Catholics away from these theses. However, it does not tell us what the problem was in particular cases. It could have been any of the following:

- The thesis is heretical

- The thesis is scandalous

- The thesis is false

- The thesis is offensive to pious ears

- The thesis is seductive of simple minds

- The thesis is opposed to Catholic truth

The difference between these is significant:

- If something is heretical then it is both false and contrary to a divinely revealed dogma

- If it is scandalous then it can lead people into sin

- If it is false then it is not true, though it may not be opposed to a dogma

- If it is offensive to pious ears then it is badly and offensively phrased

- If it is seductive of simple minds then it can mislead ordinary people

- If it is opposed to Catholic truth then it could be opposed in one of the five ways named above.

It is important to note that if the problem is (1) or (3) then the Thesis is necessarily false.

However, if the problem is (2), (4), or (5) then the Thesis is not necessarily false—it could be technically true but phrased offensively, phrased in a misleading way, or phrased in a way that could lead people to sin.

Because Exsurge Domine doesn’t assign particular censures to particular propositions, it doesn’t tell us what the status of the theses in question are. It warns us away from them but leaves it up to theologians to classify the particular problem with a thesis.

8) Does the fact that Exsurge Domine only rejects things said in six of the theses mean that the other 89 are okay?

No. This does not give the rest of The 95 Theses a clean bill of health. They can also be problematic, they just weren’t among those dealt with in Exsurge Domine .

It would be interesting to go through The 95 Theses and analyze of the degree to which each of them fits or doesn’t fit with Catholic thought, but that would be a lengthy effort that would go far beyond what can be accomplished in a blog post.

Jimmy Akin Jimmy was born in Texas and grew up nominally Protestant, but at age 20 experienced a profound conversion to Christ. Planning on becoming a Protestant pastor or seminary professor, he started an intensive study of the Bible. But the more he immersed himself in Scripture the more he found to support the Catholic faith. Eventually, he entered the Catholic Church. His conversion story, “A Triumph and a Tragedy,” is published in Surprised by Truth . Besides being an author, Jimmy is the Senior Apologist at Catholic Answers, a contributing editor to Catholic Answers Magazine , and a weekly guest on “Catholic Answers Live.”

- Related Stories

- Latest News

The Remarkable Case of Sister Wilhelmina, One Year Later

Would our mainstream media have given Sister Wilhelmina Lancaster even less coverage had it not been pushed by social media buzz?

Want to Learn More About the Blessed Sacrament? Sign Up for ‘Eucharistic Devotion,’ New EWTN Online Learning Series

The insights of Mother Angelica and the saints are included in this free offering.

How Martin Luther Invented Sola Scriptura

Luther rejected papal, conciliar and ecclesiastical infallibility and said that popes and ecumenical councils could err.

Philippine Cardinal Condemns Chapel Bombing as ‘Horrendous Sacrilegious Act’

The grenade attack happened on Pentecost Sunday at Santo Niño Chapel in Cotabato City.

Harrison Butker: In Hot Water or Too Hot to Handle?

So much is being said about a speech that wasn’t even for us.

Pope Francis: ‘It’s a Manner of Communicating My Ministry’

From skeptic to promoter: dominican friar explains the power of the rosary, ‘60 minutes’ interview with pope francis: 12 quotes on a range of topics, photos: jesus crosses the golden gate bridge at start of national eucharistic pilgrimage, vatican’s new apparitions document may lead to quicker pronouncements on purported marian apparitions, experts say, peoria diocese to reduce the number of parishes in the diocese by half, among a cloud of witnesses at the national eucharistic pilgrimage, pope francis on female deacons: ‘no’, cardinal hollerich urges caution, dialogue on women’s ordination, subscription options.

Subscriber Service Center Already a subscriber? Renew or manage your subscription here .

Subscribe and Save HALF OFF! Start your Register subscription today.

Give a Gift Subscription Bless friends, family or clergy with a gift of the Register.

Order Bulk Subscriptions Get a discount on 6 or more copies sent to your parish, organization or school.

Sign-up for E-Newsletter Get Register Updates sent daily or weeklyto your inbox.

by Dr. Martin Luther, 1517

Disputation of Doctor Martin Luther on the Power and Efficacy of Indulgences by Dr. Martin Luther (1517)

Out of love for the truth and the desire to bring it to light, the following propositions will be discussed at Wittenberg, under the presidency of the Reverend Father Martin Luther, Master of Arts and of Sacred Theology, and Lecturer in Ordinary on the same at that place. Wherefore he requests that those who are unable to be present and debate orally with us, may do so by letter. In the Name our Lord Jesus Christ. Amen. 1. Our Lord and Master Jesus Christ, when He said Poenitentiam agite, willed that the whole life of believers should be repentance. 2. This word cannot be understood to mean sacramental penance, i.e., confession and satisfaction, which is administered by the priests. 3. Yet it means not inward repentance only; nay, there is no inward repentance which does not outwardly work divers mortifications of the flesh. 4. The penalty [of sin], therefore, continues so long as hatred of self continues; for this is the true inward repentance, and continues until our entrance into the kingdom of heaven. 5. The pope does not intend to remit, and cannot remit any penalties other than those which he has imposed either by his own authority or by that of the Canons. 6. The pope cannot remit any guilt, except by declaring that it has been remitted by God and by assenting to God's remission; though, to be sure, he may grant remission in cases reserved to his judgment. If his right to grant remission in such cases were despised, the guilt would remain entirely unforgiven. 7. God remits guilt to no one whom He does not, at the same time, humble in all things and bring into subjection to His vicar, the priest. 8. The penitential canons are imposed only on the living, and, according to them, nothing should be imposed on the dying. 9. Therefore the Holy Spirit in the pope is kind to us, because in his decrees he always makes exception of the article of death and of necessity. 10. Ignorant and wicked are the doings of those priests who, in the case of the dying, reserve canonical penances for purgatory. 11. This changing of the canonical penalty to the penalty of purgatory is quite evidently one of the tares that were sown while the bishops slept. 12. In former times the canonical penalties were imposed not after, but before absolution, as tests of true contrition. 13. The dying are freed by death from all penalties; they are already dead to canonical rules, and have a right to be released from them. 14. The imperfect health [of soul], that is to say, the imperfect love, of the dying brings with it, of necessity, great fear; and the smaller the love, the greater is the fear. 15. This fear and horror is sufficient of itself alone (to say nothing of other things) to constitute the penalty of purgatory, since it is very near to the horror of despair. 16. Hell, purgatory, and heaven seem to differ as do despair, almost-despair, and the assurance of safety. 17. With souls in purgatory it seems necessary that horror should grow less and love increase. 18. It seems unproved, either by reason or Scripture, that they are outside the state of merit, that is to say, of increasing love. 19. Again, it seems unproved that they, or at least that all of them, are certain or assured of their own blessedness, though we may be quite certain of it. 20. Therefore by "full remission of all penalties" the pope means not actually "of all," but only of those imposed by himself. 21. Therefore those preachers of indulgences are in error, who say that by the pope's indulgences a man is freed from every penalty, and saved; 22. Whereas he remits to souls in purgatory no penalty which, according to the canons, they would have had to pay in this life. 23. If it is at all possible to grant to any one the remission of all penalties whatsoever, it is certain that this remission can be granted only to the most perfect, that is, to the very fewest. 24. It must needs be, therefore, that the greater part of the people are deceived by that indiscriminate and highsounding promise of release from penalty. 25. The power which the pope has, in a general way, over purgatory, is just like the power which any bishop or curate has, in a special way, within his own diocese or parish. 26. The pope does well when he grants remission to souls [in purgatory], not by the power of the keys (which he does not possess), but by way of intercession. 27. They preach man who say that so soon as the penny jingles into the money-box, the soul flies out [of purgatory]. 28. It is certain that when the penny jingles into the money-box, gain and avarice can be increased, but the result of the intercession of the Church is in the power of God alone. 29. Who knows whether all the souls in purgatory wish to be bought out of it, as in the legend of Sts. Severinus and Paschal. 30. No one is sure that his own contrition is sincere; much less that he has attained full remission. 31. Rare as is the man that is truly penitent, so rare is also the man who truly buys indulgences, i.e., such men are most rare. 32. They will be condemned eternally, together with their teachers, who believe themselves sure of their salvation because they have letters of pardon. 33. Men must be on their guard against those who say that the pope's pardons are that inestimable gift of God by which man is reconciled to Him; 34. For these "graces of pardon" concern only the penalties of sacramental satisfaction, and these are appointed by man. 35. They preach no Christian doctrine who teach that contrition is not necessary in those who intend to buy souls out of purgatory or to buy confessionalia. 36. Every truly repentant Christian has a right to full remission of penalty and guilt, even without letters of pardon. 37. Every true Christian, whether living or dead, has part in all the blessings of Christ and the Church; and this is granted him by God, even without letters of pardon. 38. Nevertheless, the remission and participation [in the blessings of the Church] which are granted by the pope are in no way to be despised, for they are, as I have said, the declaration of divine remission. 39. It is most difficult, even for the very keenest theologians, at one and the same time to commend to the people the abundance of pardons and [the need of] true contrition. 40. True contrition seeks and loves penalties, but liberal pardons only relax penalties and cause them to be hated, or at least, furnish an occasion [for hating them]. 41. Apostolic pardons are to be preached with caution, lest the people may falsely think them preferable to other good works of love. 42. Christians are to be taught that the pope does not intend the buying of pardons to be compared in any way to works of mercy. 43. Christians are to be taught that he who gives to the poor or lends to the needy does a better work than buying pardons; 44. Because love grows by works of love, and man becomes better; but by pardons man does not grow better, only more free from penalty. 45. 45. Christians are to be taught that he who sees a man in need, and passes him by, and gives [his money] for pardons, purchases not the indulgences of the pope, but the indignation of God. 46. Christians are to be taught that unless they have more than they need, they are bound to keep back what is necessary for their own families, and by no means to squander it on pardons. 47. Christians are to be taught that the buying of pardons is a matter of free will, and not of commandment. 48. Christians are to be taught that the pope, in granting pardons, needs, and therefore desires, their devout prayer for him more than the money they bring. 49. Christians are to be taught that the pope's pardons are useful, if they do not put their trust in them; but altogether harmful, if through them they lose their fear of God. 50. Christians are to be taught that if the pope knew the exactions of the pardon-preachers, he would rather that St. Peter's church should go to ashes, than that it should be built up with the skin, flesh and bones of his sheep. 51. Christians are to be taught that it would be the pope's wish, as it is his duty, to give of his own money to very many of those from whom certain hawkers of pardons cajole money, even though the church of St. Peter might have to be sold. 52. The assurance of salvation by letters of pardon is vain, even though the commissary, nay, even though the pope himself, were to stake his soul upon it. 53. They are enemies of Christ and of the pope, who bid the Word of God be altogether silent in some Churches, in order that pardons may be preached in others. 54. Injury is done the Word of God when, in the same sermon, an equal or a longer time is spent on pardons than on this Word. 55. It must be the intention of the pope that if pardons, which are a very small thing, are celebrated with one bell, with single processions and ceremonies, then the Gospel, which is the very greatest thing, should be preached with a hundred bells, a hundred processions, a hundred ceremonies. 56. The "treasures of the Church," out of which the pope. grants indulgences, are not sufficiently named or known among the people of Christ. 57. That they are not temporal treasures is certainly evident, for many of the vendors do not pour out such treasures so easily, but only gather them. 58. Nor are they the merits of Christ and the Saints, for even without the pope, these always work grace for the inner man, and the cross, death, and hell for the outward man. 59. St. Lawrence said that the treasures of the Church were the Church's poor, but he spoke according to the usage of the word in his own time. 60. Without rashness we say that the keys of the Church, given by Christ's merit, are that treasure; 61. For it is clear that for the remission of penalties and of reserved cases, the power of the pope is of itself sufficient. 62. The true treasure of the Church is the Most Holy Gospel of the glory and the grace of God. 63. But this treasure is naturally most odious, for it makes the first to be last. 64. On the other hand, the treasure of indulgences is naturally most acceptable, for it makes the last to be first. 65. Therefore the treasures of the Gospel are nets with which they formerly were wont to fish for men of riches. 66. The treasures of the indulgences are nets with which they now fish for the riches of men. 67. The indulgences which the preachers cry as the "greatest graces" are known to be truly such, in so far as they promote gain. 68. Yet they are in truth the very smallest graces compared with the grace of God and the piety of the Cross. 69. Bishops and curates are bound to admit the commissaries of apostolic pardons, with all reverence. 70. But still more are they bound to strain all their eyes and attend with all their ears, lest these men preach their own dreams instead of the commission of the pope. 71. He who speaks against the truth of apostolic pardons, let him be anathema and accursed! 72. But he who guards against the lust and license of the pardon-preachers, let him be blessed! 73. The pope justly thunders against those who, by any art, contrive the injury of the traffic in pardons. 74. But much more does he intend to thunder against those who use the pretext of pardons to contrive the injury of holy love and truth. 75. To think the papal pardons so great that they could absolve a man even if he had committed an impossible sin and violated the Mother of God -- this is madness. 76. We say, on the contrary, that the papal pardons are not able to remove the very least of venial sins, so far as its guilt is concerned. 77. It is said that even St. Peter, if he were now Pope, could not bestow greater graces; this is blasphemy against St. Peter and against the pope. 78. We say, on the contrary, that even the present pope, and any pope at all, has greater graces at his disposal; to wit, the Gospel, powers, gifts of healing, etc., as it is written in I. Corinthians xii. 79. To say that the cross, emblazoned with the papal arms, which is set up [by the preachers of indulgences], is of equal worth with the Cross of Christ, is blasphemy. 80. The bishops, curates and theologians who allow such talk to be spread among the people, will have an account to render. 81. This unbridled preaching of pardons makes it no easy matter, even for learned men, to rescue the reverence due to the pope from slander, or even from the shrewd questionings of the laity. 82. To wit: -- "Why does not the pope empty purgatory, for the sake of holy love and of the dire need of the souls that are there, if he redeems an infinite number of souls for the sake of miserable money with which to build a Church? The former reasons would be most just; the latter is most trivial." 83. Again: -- "Why are mortuary and anniversary masses for the dead continued, and why does he not return or permit the withdrawal of the endowments founded on their behalf, since it is wrong to pray for the redeemed?" 84. Again: -- "What is this new piety of God and the pope, that for money they allow a man who is impious and their enemy to buy out of purgatory the pious soul of a friend of God, and do not rather, because of that pious and beloved soul's own need, free it for pure love's sake?" 85. Again: -- "Why are the penitential canons long since in actual fact and through disuse abrogated and dead, now satisfied by the granting of indulgences, as though they were still alive and in force?" 86. Again: -- "Why does not the pope, whose wealth is to-day greater than the riches of the richest, build just this one church of St. Peter with his own money, rather than with the money of poor believers?" 87. Again: -- "What is it that the pope remits, and what participation does he grant to those who, by perfect contrition, have a right to full remission and participation?" 88. Again: -- "What greater blessing could come to the Church than if the pope were to do a hundred times a day what he now does once, and bestow on every believer these remissions and participations?" 89. "Since the pope, by his pardons, seeks the salvation of souls rather than money, why does he suspend the indulgences and pardons granted heretofore, since these have equal efficacy?" 90. To repress these arguments and scruples of the laity by force alone, and not to resolve them by giving reasons, is to expose the Church and the pope to the ridicule of their enemies, and to make Christians unhappy. 91. If, therefore, pardons were preached according to the spirit and mind of the pope, all these doubts would be readily resolved; nay, they would not exist. 92. Away, then, with all those prophets who say to the people of Christ, "Peace, peace," and there is no peace! 93. Blessed be all those prophets who say to the people of Christ, "Cross, cross," and there is no cross! 94. Christians are to be exhorted that they be diligent in following Christ, their Head, through penalties, deaths, and hell; 95. And thus be confident of entering into heaven rather through many tribulations, than through the assurance of peace.

This text was converted to ASCII text for Project Wittenberg by Allen Mulvey, and is in the public domain. You may freely distribute, copy or print this text. Please direct any comments or suggestions to:

Rev. Robert E. Smith Walther Library Concordia Theological Seminary.

E-mail: [email protected] Surface Mail: 6600 N. Clinton St., Ft. Wayne, IN 46825 USA Phone: (260) 452-3149 - Fax: (260) 452-2126

- Otis College of Art and Design

- Otis College LibGuides

- Millard Sheets Library

Citation Guide (MLA 9th Edition) UNDER CONSTRUCTION

- Theses and Dissertations

- Title of source

- Title of container

- Contributor

- Publication date

- Supplemental Elements

- Advertisements

- Books, eBooks & Pamphlets

- Class Notes & Presentations

- Encyclopedias & Dictionaries

- Government Documents

- Images, Charts, Graphs, Maps & Tables

- Interviews and Emails (Personal Communications)

- Journal Articles

- Magazine Articles

- Newspaper Articles

- Religious Texts

- Social Media

Citation Templates

Print versions, electronic versions.

- Videos & DVDs

- When Information Is Missing

- Works Quoted in Another Source

- In-Text Citations

- Sample Works Cited List

- Sample Annotations This link opens in a new window

- Plagiarism This link opens in a new window

Dissertations and theses

Dissertations and theses are written to fulfil an academic degree requirement, usually at the Masters or PhD level. They usually have only 1 author.

For the most part, treat them like books with supplemenal elements.

- Since dissertations and theses are often re-worked into articles and books, it is important to note when your source was written to fulfill an academic degree requirement

- The publisher is the degree-granting instution

- Do not include the program, department, school, division, or similar information

- Usually placed before the container of the online repository which houses the publication

- Automatic citation generators often treat online theses and dissertations as websites or journal articles, so will be missing the key information

Author's Last Name, First Name. Title of Book: Subtitle. Publication Date. University name, Degree conferred .

Author's Last Name, First Name. Title of Book: Subtitle. Publication Date. University name, Degree conferred . Online Repository , URL.

In-Text Citation

(Author's Last Name ##)

Replace ## with page number(s) for quotes or where the idea is discussed.

Smith, Kate Elizabeth. The Influence of Audrey Hepburn and Hubert de Givenchy on American Fashion, 1952-1965 . 2001. Michigan State University, MA Thesis.

Austin, Katherine. Rasquache Baroque in the Chicana/o Borderlands . 2012. McGill U, PhD thesis. eScholarship , https://escholarship.mcgill.ca/concern/theses/8p58ph61j. Accessed 6 Jan. 2023.

- eScholarship is McGill University's online repository of dissertations and theses

- Followed McGill's lead and used "thesis" instead of "dissertation"

Grullon, Jaymi Leah. Campy Musical Black Queer Forms: Finding Utopia in Lil Nas X's World of "Montero ". St. John's University, MA Thesis. St. John's Scholar , https://scholar.stjohns.edu/theses_dissertations/477

- St. John's Scholar is the university's online repository of dissertations and theses

Hutchinson, Jennifer. Emotional Response to Climate Change Learning: An Existential Inquiry . 2021. Antioch University, Antioch University, Doctoral dissertation. EBSCOhost , search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=ip,sso&db=ddu&AN=29DBEAFBF585BC45&site=eds-live&scope=site.

- Found record in OwlCat, so used EBSCOhost as the repository

- Could be more specific and replace the EBSCOhost info with: OhioLINK Electronic Theses and Dissertations Center , http://rave.ohiolink.edu/etdc/view?acc_num=antioch1602019356792951.

- << Previous: Social Media

- Next: Videos & DVDs >>

- Last Updated: Feb 23, 2024 4:22 PM

- URL: https://otis.libguides.com/mla_citations

Otis College of Art and Design | 9045 Lincoln Blvd. Los Angeles, CA 90045 | MyOtis

Millard Sheets Library | MyOtis | 310-665-6930 | Ask a Librarian

- Roman Empire

- Roman Republic

- Influential People

- American History

- Historical Inventions

- Medieval Europe

- Important Events

- Ancient Greece

- The Top Lists of History

- About The Site, Author, and Contact

© 2024 The History Ace

3 Ways Martin Luther’s 95 Theses Changed The World

In 1517 Martin Luther published a thesis attacking the process of selling indulgences by the Catholic Church. This publication sent shockwaves around Europe and sparked what is now known as the Protestant Reformation.

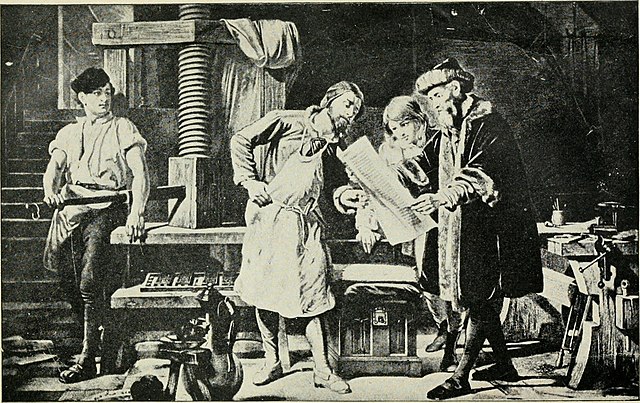

There are 3 major ways that Luther’s theses changed the world forever. First, Martin Luther’s theses attacked the very core of European medieval society. Second, Luther’s 95 Thesis demonstrated the power of the newly invented printing press. Third, Martin Luther’s work led to the creation of the modern nation-state.

Here at The History Ace, I strive to publish the best history articles on the internet. If at the end of this article you enjoyed it then consider subscribing to the free newsletter and sharing it around the web.

Further, you can check out some of the other articles below.

Martin Luther’s 95 Theses Challenged the Very Core of European Medieval Society

One of the major ways in which Martin Luther’s 95 theses changed the world was due to its direct attack against the very core of European Medieval Society.

For nearly 1,000 years the society of Europe revolved around the dominance of the Roman Catholic church. This religious institution managed to spread across Europe from eastern Germany to Spain and up to England. This Catholic church would be the ultimate power in the land and had the authority to install kings and lords into power.

The problem however was the cost to continue to run this massive bureaucratic institution. Along with large donations, the European church would also start to sell indulgences for money. A plenary indulgence is given out by a member of the clergy to absolve one of sins.

The problem was however up until this point most indulgences were forgiven by the clergy through small actions such as prayer or reading scripture. Sometime around the early 15th century the European church began to flat out sell these indulgences.

If you had committed a crime or sin you could pay your way out of the punishment. As you might imagine this started to cause a problem across segments of the European population who could not afford to pay for such indulgences.

Martin Luther published his 95 theses directly attacking this practice. He argued that there was no need to pay for these indulgences and that the very act of doing so was against the established doctrine of Christianity.