I Got Published In The New Yorker: Tips And Insights From A Successful Submitter

Getting your writing published in the prestigious pages of The New Yorker is a career-defining accomplishment for any writer or journalist. The magazine’s legendary selectivity and rigorous editing process means that just landing an article, short story or poem in The New Yorker is a major success worthy of celebrating. But how does one actually go about getting published there? In this comprehensive guide, we share insider tips and hard-won lessons from someone who successfully made it into the hallowed pages of The New Yorker.

If you’re short on time, here’s a quick answer to your question: The keys to getting published in The New Yorker are 1) Target your submissions carefully by deeply understanding the magazine’s voice and sections, 2) Perfect and polish your best work before submitting, and 3) Persist through rejection after rejection until an acceptance finally comes through .

In the sections below, we’ll share everything I learned and did along my journey to New Yorker publication, from how I identified what to pitch and submit, to handling those inevitable rejection slips, to working with editors once a piece was accepted. I’ll also pass along wisdom from New Yorker staff and other successful contributors. Whether you’re a writer who dreams of seeing your name under those distinctive cartoons and columns, or simply curious about the submission process, use this guide to gain real-world insights into achieving the writing milestone of getting into The New Yorker.

Understanding The New Yorker’s Editorial Needs

Getting published in The New Yorker is a dream for many writers. With its prestigious reputation and high editorial standards, it’s no wonder that aspiring authors aim to see their work in its pages. To increase your chances of success, it’s important to understand The New Yorker’s editorial needs.

Here are some tips and insights to help you navigate the submission process.

Studying the different sections of the magazine

The New Yorker is known for its diverse range of content, covering topics such as fiction, poetry, essays, cartoons, and more. To better understand what the magazine is looking for, it’s essential to study the different sections and get a sense of their style and themes.

Spend time reading through past issues and familiarize yourself with the types of pieces that are typically published in each section.

For example, if you are interested in submitting fiction, read stories from previous issues to get a feel for the kind of narratives that resonate with The New Yorker’s readership. Pay attention to the tone, language, and themes explored in these stories.

This will give you valuable insights into what the editors are looking for and help you tailor your submission accordingly.

Reading issues like an editor

When reading The New Yorker, approach it with an editor’s mindset. Take note of the articles, essays, or poems that stand out to you and analyze what makes them compelling. Consider the structure, writing style, and unique perspectives that make these pieces successful.

By doing this, you’ll start to develop an understanding of the editorial preferences and tendencies of The New Yorker.

Additionally, pay attention to the topics and subject matters covered in the magazine. Are there any recurring themes or areas of interest? Understanding the magazine’s editorial direction will help you align your work with their needs and increase your chances of catching the attention of the editors.

Remember, The New Yorker receives an overwhelming number of submissions, so it’s crucial to stand out from the crowd. By studying the different sections of the magazine and reading issues like an editor, you’ll be better equipped to tailor your submission to meet The New Yorker’s editorial needs.

Crafting Your Best New Yorker-Worthy Submissions

Submitting your work to The New Yorker can be a daunting task, but with the right approach and a little bit of luck, you too can see your writing published in this prestigious magazine. Here are some tips and insights to help you craft your best New Yorker-worthy submissions:

Matching your writing style to The New Yorker’s voice

One of the most important aspects of getting published in The New Yorker is understanding and matching their distinctive voice and style. The magazine is known for its sophisticated and witty writing, so it’s essential to familiarize yourself with their articles and essays.

Pay attention to the tone, language, and overall vibe of the pieces they publish. This will give you a better understanding of what they are looking for in submissions.

Additionally, don’t be afraid to inject your own personality and unique perspective into your writing. The New Yorker appreciates fresh and original voices, so find a way to stand out while still staying true to their style.

Experiment with different writing techniques and incorporate elements of humor or satire if it aligns with your work.

Creating multiple targeted drafts

When submitting to The New Yorker, it’s crucial to tailor your drafts specifically for the magazine. Avoid sending the same piece to multiple publications without making any modifications. Instead, create different versions of your work, each targeted towards a specific theme or section of the magazine.

Research the different sections of The New Yorker and identify the ones that best align with your writing. Whether it’s fiction, poetry, essays, or cultural commentary, each section has its own unique requirements.

Take the time to understand what they are looking for in each category and adapt your writing accordingly.

Remember, quality is key. Take the time to polish your drafts and make sure they are the best representation of your work. Proofread for grammar and spelling errors, and consider seeking feedback from writing groups or trusted friends.

The more effort you put into crafting targeted and well-written submissions, the better your chances of catching the attention of The New Yorker’s editors.

For more information and inspiration, you can visit The New Yorker’s official website at www.newyorker.com . Their website provides valuable resources, including writing guidelines and examples of previously published work, which can further guide you in crafting your best New Yorker-worthy submissions.

Submitting Your Work and Handling Rejections

Submitting your work to The New Yorker or any other prestigious publication can be an exciting but nerve-wracking experience. However, with the right approach and mindset, you can increase your chances of success.

Here are some valuable tips and insights to help you navigate the submission process and handle rejections with grace.

Following submission guidelines closely

One of the most important aspects of submitting your work to The New Yorker is to follow their submission guidelines closely. The guidelines are there for a reason, and not adhering to them could result in your work being rejected without even being considered.

Take the time to carefully read and understand the guidelines, and make sure your submission meets all the specified requirements. This includes formatting, word count, and any other specific instructions given by the publication.

Furthermore, it’s worth noting that The New Yorker is known for having a unique style and voice. Familiarize yourself with the publication by reading previous issues and understanding their editorial preferences.

This will help you tailor your submission to align with their aesthetic and increase your chances of acceptance.

Persisting through inevitable rejections

Receiving a rejection letter can be disheartening, but it’s important not to let it discourage you from continuing to submit your work. Even the most successful writers have faced numerous rejections throughout their careers.

Remember, rejection is not a reflection of your talent or worth as a writer; it’s simply a part of the publishing process.

Instead of dwelling on rejections, use them as an opportunity to learn and improve. Take the feedback provided, if any, and consider it constructively. Reflect on your work, make revisions if necessary, and keep submitting. The more you persist, the higher your chances of eventually getting published.

It’s all about perseverance and resilience.

Additionally, it can be helpful to join writing communities or seek support from fellow writers who have experienced rejection themselves. Sharing your experiences and discussing strategies can provide valuable insights and encouragement.

Remember, every successful writer has faced rejection at some point in their journey. It’s how you handle those rejections and continue to refine your craft that will ultimately lead to success. So, don’t give up, keep submitting, and one day you may see your work in the pages of The New Yorker or any other publication you aspire to be a part of.

Working Successfully with New Yorker Editors

Expecting rigorous editing of accepted pieces.

One of the key aspects of working with New Yorker editors is understanding and embracing the rigorous editing process that your accepted piece will go through. The New Yorker has a longstanding reputation for its high editorial standards, and they take great care in refining and polishing every piece of work that gets published.

This means that as a writer, you should be prepared for multiple rounds of revisions and feedback from the editors. Don’t be discouraged or take it personally if your piece undergoes significant changes during the editing process .

It’s all part of the collaborative effort to ensure that the final product meets the publication’s standards.

Collaborating professionally during the refinement process

When working with New Yorker editors, it’s crucial to maintain a professional and collaborative attitude throughout the refinement process. Listen to and consider their feedback carefully , as they have a wealth of experience and insight into what works best for their publication.

Be open to suggestions and be willing to make revisions that align with the overall vision of the piece. Remember, the goal is to create the best possible version of your work that resonates with The New Yorker’s audience.

During the collaboration, it’s important to communicate effectively and promptly . Respond to emails or requests for revisions in a timely manner, and make sure to ask for clarification if there’s something you don’t understand.

Be respectful of the editors’ time and workload and show your appreciation for their expertise and guidance.

While working with New Yorker editors can be an intense and demanding process, it is also an incredibly rewarding one. The collaboration and refinement of your work with experienced professionals can help elevate your writing to new heights and increase your chances of getting published in one of the most prestigious literary magazines in the world.

Maximizing the Benefits of Being a New Yorker Contributor

Getting published in The New Yorker is a dream come true for many writers. It not only gives you the satisfaction of seeing your work in one of the most prestigious literary magazines in the world, but it also opens up a world of opportunities for your writing career.

Here are some tips and insights on how to maximize the benefits of being a New Yorker contributor.

Adding a New Yorker credit to your writing portfolio

Having a New Yorker credit in your writing portfolio is like having a golden stamp of approval. It instantly elevates your credibility as a writer and catches the attention of literary agents, publishers, and other industry professionals.

When showcasing your New Yorker publication, be sure to highlight it prominently in your portfolio, whether it’s a physical or online version.

Include a brief description of the piece you had published, and if possible, provide a direct link to the article or a PDF version. This allows potential clients or employers to read your work easily and see the quality of your writing firsthand.

Remember to update your portfolio regularly with any new New Yorker publications to keep it fresh and relevant.

Leveraging the prestige of New Yorker publication

The prestige of being a New Yorker contributor goes beyond just having a credit in your portfolio. It can open doors to various writing opportunities and collaborations. Use your New Yorker publication as a springboard to pitch ideas or submit your work to other prestigious publications, literary magazines, or even book publishers.

When reaching out to other publications, mention your New Yorker credit in your pitch or query letter to grab the editor’s attention. Highlight how your writing has been recognized by one of the most respected publications in the industry and emphasize the unique perspective or style that got you published in The New Yorker.

This can increase your chances of being accepted by other publications and boost your overall writing career.

Furthermore, being a New Yorker contributor can also attract speaking engagements, panel discussions, or even teaching opportunities. Organizations and institutions often seek out writers with a strong publication record, especially if they have been published in prestigious outlets like The New Yorker.

Leverage your New Yorker credit to showcase your expertise and secure these types of opportunities.

As a writer, seeing your name printed in The New Yorker is an incredible feeling hard to replicate. While getting published there requires immense skill as a writer, persistence through rejection, and professionalism when working with demanding editors, it is an accomplishment well worth striving for over a writing career. Use the tips and learnings from my journey outlined here to tilt the odds of a New Yorker acceptance in your favor, no matter how long it takes. The destination is worth the journey many times over when you can finally call yourself a New Yorker contributor.

Hi there, I'm Jessica, the solo traveler behind the travel blog Eye & Pen. I launched my site in 2020 to share over a decade of adventurous stories and vivid photography from my expeditions across 30+ countries. When I'm not wandering, you can find me freelance writing from my home base in Denver, hiking Colorado's peaks with my rescue pup Belle, or enjoying local craft beers with friends.

I specialize in budget tips, unique lodging spotlights, road trip routes, travel hacking guides, and female solo travel for publications like Travel+Leisure and Matador Network. Through my photography and writing, I hope to immerse readers in new cultures and compelling destinations not found in most guidebooks. I'd love for you to join me on my lifelong journey of visual storytelling!

Similar Posts

Toronto Vs New York City: How Do The Cities Compare?

Toronto and New York City are two of the largest and most vibrant cities in North America. As global hubs of finance, culture, and entertainment, they share some similarities but also have distinct identities and advantages. If you’re short on time, here’s a quick answer: While New York City is significantly larger and more globally…

Lake Tahoe California Or Nevada Side: Which Is Better?

Straddling the border between California and Nevada, Lake Tahoe offers stunning alpine scenery and outdoor recreation on both shores. But which side is better: California or Nevada? If you’re short on time, here’s a quick answer: The California side tends to be more developed with busier towns and beaches, while the Nevada side is quieter…

Does Costco Sell Liquor In Florida?

With over 200 warehouse club locations in Florida, Costco is a popular shopping destination for many residents. But does the retail giant sell liquor at its Florida stores? In this comprehensive guide, we’ll provide a definitive answer on Costco’s liquor policies in the Sunshine State. If you’re short on time, here’s a quick answer to…

The Majestic Mountains Surrounding Las Vegas

Las Vegas may be known for its glitzy casinos and neon-lit Strip, but just beyond the city lies a rugged landscape of breathtaking mountain ranges and peaks. If you’re short on time, here’s a quick answer: The Spring Mountains, Sheep Range, Mormon Mountains, McCullough Range and Arrow Canyon Mountains surround Las Vegas. This article explores…

Can I Travel Through Colorado With High-Capacity Magazines?

As a gun owner, staying up-to-date on state laws regarding magazine capacity is crucial to staying legal when traveling across state lines. Colorado has restrictions on the possession, sale, and transfer of magazines holding over 15 rounds of ammunition. So what are the laws regarding transporting high-capacity magazines through the state of Colorado? If you’re…

Can A Husky Live In Florida?

With their thick, plush coats and affinity for cold weather, huskies are often associated with snowy climates. So could this breed really thrive in sunny, tropical Florida? Many prospective husky owners wonder if the hot, humid environment would be suitable for these dogs. If you’re short on time, here’s a quick answer to your question:…

What are your chances of acceptance?

Calculate for all schools, your chance of acceptance.

Your chancing factors

Extracurriculars.

How to Write a Strong Thesis Statement: 4 Steps + Examples

What’s Covered:

What is the purpose of a thesis statement, writing a good thesis statement: 4 steps, common pitfalls to avoid, where to get your essay edited for free.

When you set out to write an essay, there has to be some kind of point to it, right? Otherwise, your essay would just be a big jumble of word salad that makes absolutely no sense. An essay needs a central point that ties into everything else. That main point is called a thesis statement, and it’s the core of any essay or research paper.

You may hear about Master degree candidates writing a thesis, and that is an entire paper–not to be confused with the thesis statement, which is typically one sentence that contains your paper’s focus.

Read on to learn more about thesis statements and how to write them. We’ve also included some solid examples for you to reference.

Typically the last sentence of your introductory paragraph, the thesis statement serves as the roadmap for your essay. When your reader gets to the thesis statement, they should have a clear outline of your main point, as well as the information you’ll be presenting in order to either prove or support your point.

The thesis statement should not be confused for a topic sentence , which is the first sentence of every paragraph in your essay. If you need help writing topic sentences, numerous resources are available. Topic sentences should go along with your thesis statement, though.

Since the thesis statement is the most important sentence of your entire essay or paper, it’s imperative that you get this part right. Otherwise, your paper will not have a good flow and will seem disjointed. That’s why it’s vital not to rush through developing one. It’s a methodical process with steps that you need to follow in order to create the best thesis statement possible.

Step 1: Decide what kind of paper you’re writing

When you’re assigned an essay, there are several different types you may get. Argumentative essays are designed to get the reader to agree with you on a topic. Informative or expository essays present information to the reader. Analytical essays offer up a point and then expand on it by analyzing relevant information. Thesis statements can look and sound different based on the type of paper you’re writing. For example:

- Argumentative: The United States needs a viable third political party to decrease bipartisanship, increase options, and help reduce corruption in government.

- Informative: The Libertarian party has thrown off elections before by gaining enough support in states to get on the ballot and by taking away crucial votes from candidates.

- Analytical: An analysis of past presidential elections shows that while third party votes may have been the minority, they did affect the outcome of the elections in 2020, 2016, and beyond.

Step 2: Figure out what point you want to make

Once you know what type of paper you’re writing, you then need to figure out the point you want to make with your thesis statement, and subsequently, your paper. In other words, you need to decide to answer a question about something, such as:

- What impact did reality TV have on American society?

- How has the musical Hamilton affected perception of American history?

- Why do I want to major in [chosen major here]?

If you have an argumentative essay, then you will be writing about an opinion. To make it easier, you may want to choose an opinion that you feel passionate about so that you’re writing about something that interests you. For example, if you have an interest in preserving the environment, you may want to choose a topic that relates to that.

If you’re writing your college essay and they ask why you want to attend that school, you may want to have a main point and back it up with information, something along the lines of:

“Attending Harvard University would benefit me both academically and professionally, as it would give me a strong knowledge base upon which to build my career, develop my network, and hopefully give me an advantage in my chosen field.”

Step 3: Determine what information you’ll use to back up your point

Once you have the point you want to make, you need to figure out how you plan to back it up throughout the rest of your essay. Without this information, it will be hard to either prove or argue the main point of your thesis statement. If you decide to write about the Hamilton example, you may decide to address any falsehoods that the writer put into the musical, such as:

“The musical Hamilton, while accurate in many ways, leaves out key parts of American history, presents a nationalist view of founding fathers, and downplays the racism of the times.”

Once you’ve written your initial working thesis statement, you’ll then need to get information to back that up. For example, the musical completely leaves out Benjamin Franklin, portrays the founding fathers in a nationalist way that is too complimentary, and shows Hamilton as a staunch abolitionist despite the fact that his family likely did own slaves.

Step 4: Revise and refine your thesis statement before you start writing

Read through your thesis statement several times before you begin to compose your full essay. You need to make sure the statement is ironclad, since it is the foundation of the entire paper. Edit it or have a peer review it for you to make sure everything makes sense and that you feel like you can truly write a paper on the topic. Once you’ve done that, you can then begin writing your paper.

When writing a thesis statement, there are some common pitfalls you should avoid so that your paper can be as solid as possible. Make sure you always edit the thesis statement before you do anything else. You also want to ensure that the thesis statement is clear and concise. Don’t make your reader hunt for your point. Finally, put your thesis statement at the end of the first paragraph and have your introduction flow toward that statement. Your reader will expect to find your statement in its traditional spot.

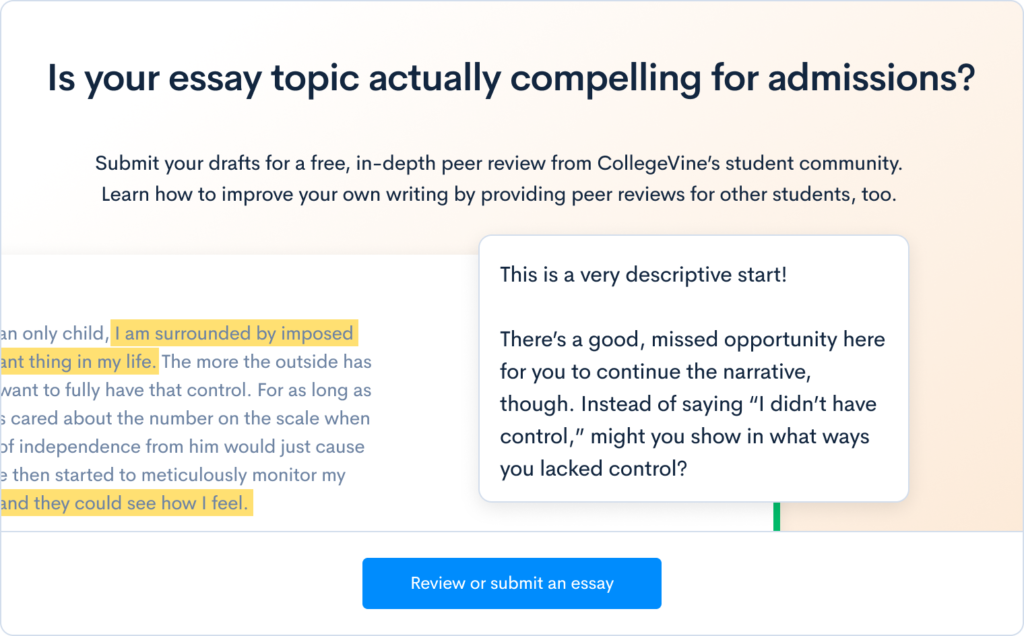

If you’re having trouble getting started, or need some guidance on your essay, there are tools available that can help you. CollegeVine offers a free peer essay review tool where one of your peers can read through your essay and provide you with valuable feedback. Getting essay feedback from a peer can help you wow your instructor or college admissions officer with an impactful essay that effectively illustrates your point.

Related CollegeVine Blog Posts

Grad Student How-To: Mastering the Thesis

For many graduate students, spring semester means it’s time to dig into writing your thesis. I’m sure that we can all agree that doing so is a bit, well, stressful, to say the least. That’s okay though! Here are some ways to make a daunting process a little less so:

Best of luck finishing up those theses!

/images/cornell/logo35pt_cornell_white.svg" alt="how to write a thesis new yorker"> Cornell University --> Graduate School

Guide to writing your thesis/dissertation, definition of dissertation and thesis.

The dissertation or thesis is a scholarly treatise that substantiates a specific point of view as a result of original research that is conducted by students during their graduate study. At Cornell, the thesis is a requirement for the receipt of the M.A. and M.S. degrees and some professional master’s degrees. The dissertation is a requirement of the Ph.D. degree.

Formatting Requirement and Standards

The Graduate School sets the minimum format for your thesis or dissertation, while you, your special committee, and your advisor/chair decide upon the content and length. Grammar, punctuation, spelling, and other mechanical issues are your sole responsibility. Generally, the thesis and dissertation should conform to the standards of leading academic journals in your field. The Graduate School does not monitor the thesis or dissertation for mechanics, content, or style.

“Papers Option” Dissertation or Thesis

A “papers option” is available only to students in certain fields, which are listed on the Fields Permitting the Use of Papers Option page , or by approved petition. If you choose the papers option, your dissertation or thesis is organized as a series of relatively independent chapters or papers that you have submitted or will be submitting to journals in the field. You must be the only author or the first author of the papers to be used in the dissertation. The papers-option dissertation or thesis must meet all format and submission requirements, and a singular referencing convention must be used throughout.

ProQuest Electronic Submissions

The dissertation and thesis become permanent records of your original research, and in the case of doctoral research, the Graduate School requires publication of the dissertation and abstract in its original form. All Cornell master’s theses and doctoral dissertations require an electronic submission through ProQuest, which fills orders for paper or digital copies of the thesis and dissertation and makes a digital version available online via their subscription database, ProQuest Dissertations & Theses . For master’s theses, only the abstract is available. ProQuest provides worldwide distribution of your work from the master copy. You retain control over your dissertation and are free to grant publishing rights as you see fit. The formatting requirements contained in this guide meet all ProQuest specifications.

Copies of Dissertation and Thesis

Copies of Ph.D. dissertations and master’s theses are also uploaded in PDF format to the Cornell Library Repository, eCommons . A print copy of each master’s thesis and doctoral dissertation is submitted to Cornell University Library by ProQuest.

- Freelancing

- Internet Writing Journal

- Submissions Gudelines

- Writing Contests

Karlie Kloss to Relaunch Life Magazine at Bedford Media

NBF Expands National Book Awards Eligibility Criteria

Striking Writers and Actors March Together on Hollywood Streets

Vice Media Files for Chapter 11 Bankruptcy

- Freelance Writing

- Grammar & Style

- Self-publishing

- Writing Prompts

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

How to Write a ‘How-To’: A Step-by-Step Guide to Our Contest

We walk you through how to brainstorm a topic, interview an expert and write your own original “How to ….”

By Natalie Proulx and Katherine Schulten

“If you want to know how to do something, don’t just search the internet,” advises Malia Wollan , the longtime writer of Tip , a how-to column that ran weekly in The New York Times Magazine for seven years. “Instead, find a person who already knows how and ask them.”

That’s the challenge we are posing to students in “How to … ,” our new informational writing contest for teenagers : Interview an expert about (almost) any skill and then write an engaging and informative essay explaining it to readers.

In this guide, we’ll show you how to do that, with advice from the how-to expert herself, Ms. Wollan. You’ll start by getting familiar with the Tip format. Then you’ll brainstorm a topic for your own piece, find and interview an expert and, finally, put it all together.

When you’re ready, you can submit your completed how-to essay to our contest , which is accepting submissions through Feb. 14.

A step-by-step guide:

1. read some “tip” articles to understand the form., 2. look more closely at one piece., 3. brainstorm your topic., 4. find an expert., 5. conduct the interview., 6. put it all together..

What does a how-to essay look like? There are, of course, many ways to write one. For instance, you may have consulted wikiHow in the past, whether to learn how to make a realistic New Year’s resolution , fold a fitted sheet , reheat rice or do one of the many, many other things the site can teach you.

But since the inspiration for our contest comes from the Tip column in The Times, spending some time examining how it works is the logical first step in constructing your own.

Start by reading any three Tip articles of your choice.

If you don’t have a Times subscription, this guide can help. If you click on any of the 40-plus Tip topics we link here, you can access them for free, as long as you open them directly from this page. (Note to teachers: If your class does have a Times subscription and you are working from the column itself , be aware that some articles may not be appropriate. Please preview before sharing.)

Here are some options to help you choose:

Maybe you’re interested in learning a physical skill, such as how to build a sand castle , skip a stone , do the splits , tackle someone , spot a shooting star , crack a safe or find a four-leaf clover .

Or maybe you would rather up your emotional intelligence by, say, learning how to laugh at yourself , let your mind wander , recover from being ghosted , build an intentional community , be less fearful of the dark or forgive .

Perhaps you want to know how to do something practical, like break in boots , fix a brake light , mend a pair of jeans , use emojis , put out a grease fire , read faster , survive an avalanche , ask for an extension or find a lost hamster .

Or maybe you’d rather choose something offbeat, like how to start a family band , talk to dogs , communicate through facial expressions , make a love potion , build a fort , enjoy snowflakes , wash your hair in space or race pigeons .

After you’ve read three, answer these questions:

What do you notice about the structure, organization and language of a Tip column?

What predictable elements can readers expect to find in every edition?

If you did the activity above, you might have noticed some of these elements:

Tip articles are short: Each column is about 400 words and around four paragraphs long. Our challenge asks you to write something of about the same length.

The topics are usually ultra-specific: The skills described might be physical ( how to skip a stone ) or emotional ( how to forgive ), serious ( how to suture a wound ) or offbeat ( how to befriend an eagle ), but they are always small enough that they can be fully explained within the limited word count.

Each article features a single expert source: You probably noticed that each column begins and ends with a quote from an expert on the topic and that the same expert gives background and advice throughout the piece. For this contest, we are not requiring you to follow that same format, but we are asking you to find and interview an expert to inform your essay. And if you’d like to follow that format, you may.

The advice is practical, but the pieces are engaging to read. Each includes concrete tips for how to accomplish a task, but it’s never just a boring list of steps. The writer also provides context for the skill so that readers understand how and why they might use it in their own lives. And the quotes Ms. Wollan chooses from her interviews are often colorful or full of voice, as you can see in this piece about how to appreciate spiders .

They are written to the reader: The writer addresses the reader as “you,” and often uses the imperative to craft sentences that tell the reader what (or what not) to do.

Now let’s break it down even further. Choose one Tip article to read — either one you already read in Step 1 or a new one — and then respond to the following questions:

Whom does the writer quote in the piece? Why do you think the author chose this person? What makes him or her an expert in this skill? Do you think this person was a good source of information?

Look closely at when the author chooses to quote the expert and when she paraphrases the information that person gave. What is the difference? Why do you think she chose to quote the lines she did? Give some examples from the piece to explain your reasoning.

You may have been taught in school to cite your sources by using footnotes or by putting them in parentheses after you’ve referenced the information. That’s not how journalists do it, yet they still make their sources clear. Where do you see this in the piece you read? What punctuation or wording does the author use to tell us where certain facts and details come from?

Now let’s look at how the author balances explaining how to acquire a skill and showing why it’s needed: Underline or highlight in one color the lines in the piece that tell readers how to accomplish the task, and use another color to highlight lines that give context. What do you notice about the difference in language? What do you notice about the way these pieces of information are woven together throughout?

After reading this, do you feel confident that you could accomplish the task on your own? What tips, if any, did the expert share that surprised you?

When, where and for what purpose might you use this skill in your own life? What lines help readers see how this skill might be relevant to their lives?

What else do you admire about this piece, whether it’s the topic covered, the way it’s written or anything else?

Now that you better understand how to write a how-to, it’s your turn to write one!

First, of course, you must find a topic. For a Times Insider article about how the Tip column is made , Ms. Wollan and her editor, Dean Robinson, describe how they found their ideas:

She often gets suggestions. Many people ask her to write about navigating interpersonal relationships; Ms. Wollan acquiesced in the case of a highly-requested Tip on how to break up with a therapist. She thinks people come to her because “that stuff is hard to navigate and it’s also hard to Google.” Some of the more recognizable scenarios featured in Tip columns come from Ms. Wollan’s own life. She credits being a mother as the inspiration for columns on delivering babies , singing lullabies and apologizing to children . Mr. Robinson occasionally comes across ideas in his life, too. He suggested a piece on how to find a hamster in your house, he said, “because we’ve lost some hamsters.”

Brainstorm as many possible topics as you can for your how-to piece. Here are some ways to start:

Respond to our related Student Opinion forum . We pose 10 questions designed to help you brainstorm about what you’d like to learn to do, and what you already do well. We hope you’ll not only provide your own answers, but also scroll through the answers of others.

Ask for suggestions. What skills have your friends, family and neighbors always wanted to learn? What do they already consider themselves experts on? Keep a running list.

Get inspiration from the Tip column . As you scroll through the column, which headlines stand out to you? Could you take on a similar topic in a different way? Do any of them inspire other ideas for you?

Work with your class to compile as long a list as you can. After you’ve tried the three ideas above, come to class with your list, then share. Your ideas might spark those of others — and when it’s time to find experts, your classmates may have contacts they can share.

Once you’ve come up with as many ideas as you can, choose one for your piece and refine it until it is the right size for a 400-word piece.

These questions can help:

Which of the topics that you listed gets you most excited? Why?

For which do you think you could realistically find an expert to interview? (More on that in the next step.)

Which are already specific enough that you could thoroughly explain them in 400 words or fewer?

Which are big, but could be broken down? For instance, if you chose “learn to cook,” make a list of specific skills within that larger goal. Maybe you’d like to learn how to chop an onion, bake chocolate chip cookies, or build a healthy meal from the noodles in a ramen packet.

Which topics do you think might be most interesting to a general audience? Which feel especially unique, helpful or unexpected?

Maybe you chose your topic because you know someone who is already an expert at that task or skill. But even if you have, read through this step, because it might help you find someone even more suitable or interesting.

Here is how Ms. Wollan says she found experts for her column:

Ms. Wollan finds interview subjects by “just poking around” online and on the phone. Sometimes she has to talk to a few people before reaching the source she will feature in the column. She interviews most of her subjects by phone for about 45 minutes, sometimes longer. “I love talking to people who just maybe don’t care so much about being an expert,” Ms. Wollan said. Some of her favorite interviews have been with children and people in their 80s, who are often “looser and more generous with their advice.”

Who could be an expert on your topic? At minimum, it should be someone who is knowledgeable enough about your subject that your readers will trust his or her advice.

Some choices might be easy. For example, for her column on how to choose a karaoke song , Ms. Wollan interviewed a world karaoke champion; for her piece on how to recommend a book , she interviewed a librarian; and for her article on how to suture a wound , she interviewed a doctor.

Other choices, however, may be less obvious. For a column on how to breathe , Ms. Wollan interviewed a clarinet player; for one on how to slice a pie , she interviewed a restaurant owner; and for one on how to say goodbye , she interviewed a child-care worker who had bid farewell to many children during her career.

Brainstorm as many potential experts for your piece as you can and then choose one as the subject of your piece.

Your expert doesn’t have to be a world champion or the national head of an organization to have expertise. This person can be anyone with specialized knowledge of a field or topic. For example, if you were writing a piece on how to start bird-watching, you could interview someone who works at a local park or zoo, someone from a birding group in your town or a bird-watcher you know personally, such as a neighbor or teacher.

Like Ms. Wollan, you might start by “poking around online” for potential subjects. And you may have to talk to a few people before you decide on the person you want to feature in your piece.

If you are doing this assignment with classmates, now might be a good time to pool resources. Share your topics, and find out who might know someone with expertise in those areas. Remember that you are not allowed to interview your relatives — but you can suggest your woodworker grandma or your skateboarder cousin to someone who is writing about those topics.

When you reach out to people, keep in mind this advice from Corey Kilgannon, a New York Times reporter who has interviewed people for profiles and who was a guest on a Learning Network webinar about profile writing :

Tell the person what your goal is and where you’re coming from — that you’re writing a profile for a school assignment or a contest or a newspaper or whatever. Be straight with the person you’re interviewing. Some people might be a little nervous or shy about how this is going to turn out, or how they’re going to look. So tell them what it’s for, how long it’s going to be, that there will be photos, or whatever you can.

Once you’ve found the expert for your piece, it’s time to conduct your interview.

In “ The Art of Learning to Do Things ,” Ms. Wollan offers excellent advice that everyone participating in our challenge should take to heart:

If you want to know how to do something, don’t just search the internet. Instead, find a person who already knows how and ask them. At first, they’ll give you a hurried, broad-strokes kind of answer, assuming that you’re uninterested in all the procedural details. But of course that’s precisely what you’re after! Ask for a slowed-down, step-by-step guide through the minutiae of the thing. For seven years, I did exactly that — I called a stranger and asked that person to describe how to do a specific task or skill.

That might sound like a straightforward task, but you should come up with some questions — on your own or with your class — before you talk to your expert.

These might include questions like:

If you were to explain how to do this skill or task to someone who had never done it before, what advice would you give?

What are some common errors that those first learning this skill or trying this task often make? How can they be avoided?

What is your background in this skill? How did you get started with it? How did you learn how to do it?

When or why might a person have to use this skill? What are the benefits of knowing it?

You might also return to some of the Tip articles you read at the beginning of this lesson. Read them closely and see if you can guess what questions the writer may have asked to get the specific quotes and information the expert shared in the piece. Which of these questions might be helpful for your own interview?

Remember that interviewing is an art — and Times journalists can offer you advice.

In addition to asking good questions, it’s also your job as a journalist to make the interviewee feel comfortable, to listen carefully, to ask follow-up questions and to clarify that you have accurate information.

We have written our own extensive how-to on interviewing, filled with tips from Times journalists. Steps 3, 4 and 5 in this lesson will be especially helpful. Created for a contest we ran in 2022, the guide can walk you through preparing and practicing for an interview; keeping the conversation going while conducting it; and shaping the material into a useful piece when you’re done.

Finally, it’s time to write your piece. If you are submitting to our how-to writing contest, keep in mind that your essay must be 400 words or fewer.

Remember, too, that we are inviting you to take inspiration from the Tip column, but that you don’t have to copy its form and structure exactly — unless you’d like to. Most important, though, is to find a way to write what you want in a way that sounds and feels like you.

That said, there are a few key elements that are important to include, which can be found in our contest rubric . Below, we share some examples from the Tip column to illustrate these elements.

Introduce your expert source.

The person you interviewed will be the main source of information for your piece. Ask yourself: How will my readers know this person is an expert in the skill or task? What information should I include about this person to make my readers feel that they can trust the person’s knowledge and advice?

Here is how Ms. Wollan introduces her expert in “ How to Skip a Stone ”:

“Throw at a 20-degree angle,” says Lydéric Bocquet, a physics professor at École Normale Supérieure in Paris.

Later, she further explains Mr. Bocquet’s expertise:

Bocquet’s quest to understand how this happens — how a solid object can skim along water without immediately sinking — began more than a decade ago, while he was skipping stones on the Tarn River in southern France with his young son. “He turns to me,” Bocquet says, “and asks, ‘Why does the stone bounce on the water?’” To answer that question satisfactorily, Bocquet and his colleagues built a mechanical stone skipper and analyzed the angle of each toss using high-speed video. They also created a set of mathematical equations to predict the number of skips.

How do you know Bocquet is an expert in skipping stones? Do you, as the reader, trust him as an expert on this topic? Why or why not?

Explain how to do the task or skill.

The heart of your piece is, of course, your explanation. You might start by making a list of steps that your expert source shared and then paring it down to the most essential information.

Ask yourself:

What instructions are crucial to the reader’s understanding of how to accomplish this skill or task?

What did the expert share that I found surprising or may not have thought of?

What details can I leave out, either because they are not very interesting or because they are less important?

What sequence for the steps make the most sense for my readers?

Consider the first paragraph from “ How to Build a Sand Castle ”:

“Use your architect mind,” says Sudarsan Pattnaik, an award-winning sand sculptor from Puri, a seaside city in India. If you’re building from memory, first envision your castle. For Pattnaik, who is 42, that means well-known Hindu or Muslim sites. “I have made so many Taj Mahals,” he says. Build with fine-grained sand already wetted by an outgoing tide. “Dry sand is too, too difficult,” Pattnaik says. Bring tools: hand shovels, buckets with the bottoms cut off and squirt bottles. Tamp wet sand into your bucket molds, setting one layer and then the next, like bricks. Sculpt architectural details from the top of the mound down. Bring reference photographs if you’re aiming for realism.

See if you can identify all the steps to making a sand castle that the writer shares in this paragraph. What do you notice about the order? What, if anything, do you think the writer might have left out, and why do you think she made that choice? What tips did you find most surprising? What do these lines add to the piece?

Notice also the grammatical structure Ms. Wollan uses: “Build with fine-grained sand”; “bring tools”; “tamp wet sand into your bucket molds”; and so on. This is called the imperative mood and is often used when telling others how to do something.

Include at least one quote.

If you are submitting to our contest, you need to include a minimum of one direct quote from the expert. Ask yourself: What quotes from my interview are so interesting, important, surprising, informative or colorful that I need to find a way to fit them in?

Look at “ How to Do the Splits ,” in which Ms. Wollan interviewed Kendrick Young, a professional sumo wrestler:

Start by stretching every day after you get out of the shower (heat increases muscle and ligament flexibility). Wear comfortable, stretchy attire. “Definitely don’t try to do this in jeans,” Young says. Sit with your legs spread as wide as you can. Once you can do that without hunching, begin to lean toward the ground, exhaling as you go. “You don’t want to be bending over a big pocket of air in your lungs,” Young says. It might help to have someone push down on your midback (historically, sumo wrestlers often stood on one another’s backs to force the body to the floor).

Why do you think the writer chose to include these two specific quotes in the piece, while paraphrasing (or writing in her own words) the rest of what Young said? What additional context did the writer provide to help us understand the purpose and relevance of these quotations?

Provide a purpose for reading.

Remember that a how-to essay is not just a list of steps; your readers should also understand how this topic might be relevant to their lives. Ask yourself: Why should a reader care about this skill or task? Where, when or for what reasons might someone want or need to do it?

Consider the last paragraph in “ How to Start a Family Band ”:

To be in a family band, you have to be prepared to spend a lot of time together, actively working on cohesion. Music can act as a kind of binding agent. When they’re not in quarantine, the Haim sisters see, or at least talk to, each other every day. “Instead of camping as kids, or going hiking, it was like, ‘OK, we’re going to practice a few songs,’” Danielle says. “It was definitely my parents’ ploy to spend more time with us.”

What reason does the writer provide for why a reader might want to try this activity? What additional background does she share from the expert, Danielle Haim, to help explain why a family — even one that might not be musical — may want to start a band together?

Submit your final piece.

Once you’ve written and edited your essay, give it a title (“How to…”) and submit it to our contest by Feb. 14. We can’t wait to learn the skills you’ll teach us!

Natalie Proulx joined The Learning Network as a staff editor in 2017 after working as an English language arts teacher and curriculum writer. More about Natalie Proulx

Katherine Schulten has been a Learning Network editor since 2006. Before that, she spent 19 years in New York City public schools as an English teacher, school-newspaper adviser and literacy coach. More about Katherine Schulten

Global Studies

- Humanities Perspectives

- Social Sciences Perspectives

- General Library Information

- Term Papers and Senior Theses

- Study Abroad

The Research Process

- General Research Tips

- How do I choose a Topic?

- How do I focus my Topic?

- Language and Usage Guides

- Citation Style Guide

- Start your research early.

- Make sure your professor approves your topic!

- Read actively and critically.

- Write as you go.

- Think about your sources and evaluate them thoroughly. Peer-reviewed sources are generally more reliable.

Resources to Help

- Ask a librarian will connect you with a library to help you navigate collections

- NYU's Writing Center will help any NYU student can get help with writing

Document your sources carefully.

- RefWorks , a citation management software program, can save you time and effort! It is available for free for NYU students.

- The Library also provides the premium version of EasyBib.

The time has come. You can’t avoid it any longer. You are going to have to write a paper. How do you get from this realization to the finished product?

First, unless your instructor assigns a specific topic, you’ll need to think of one. This is often the toughest—and the most crucial—part of the process. Fortunately, the library can help! By following this series of steps, you can figure out your topic and be handing in that paper before you know it.

Click the links for details on each step:

- Right from the start of any class, you should always be asking yourself: What's starting to be really interesting to me? What do I find myself caring about? For example, you're taking an American history course, and when the class gets to the section on the 1960s Civil Rights Movement, something clicks. You're suddenly paying extra attention, thinking of lots of questions, and wanting to read and know more. This is the kind of topic you should choose for your research.

- The Civil Rights Movement is an enormous subject, and your topic will be impossible to research if it is either too broad or too narrow. Once you’ve decided on a broad topic like the Civil Rights Movement, ask yourself: What it is it about this broad topic that interests me? Maybe you’re interested in the Civil Rights Movement’s music, in which case you might ask: How did music help to shape the actions of the 1960s Civil Rights Movement?

- Now that you’ve asked the question, it’s time to think of some keywords that might relate to it. This will help you seek information sources about your topic. Initially, the keywords will probably be obvious. Just from the question itself, we can come up with:

- Civil Rights Movement; music; 1960s

- We can also think of some possibly related terms. For instance, many of the songs were likely to have African American influences, with Christian or gospel roots. So we could say that some more keywords might be:

- Christian (or Christianity); gospel music; African American

- Reference materials—that is, encyclopedias, dictionaries & handbooks —can be a big help at this point. These sources can quickly summarize the research in a given area and direct you to further reading. There are reference works on hundreds, even thousands, of highly specified topics. See what reference works have been written in the subjects you’ve identified as your keywords, and pretty soon you’ll have started to refine your research topic—gaining insights about some finer points, finding some new keywords, learning specific questions to ask.

- Now that you have some basic knowledge about the topic under your belt, you can start to look for even more information, such as books and scholarly articles. Now, you need to ask: What scholars might have produced material on this topic? In our case, this might be: • historians of the 1960s, or of the Civil Rights Movement • musicologists • Africana Studies or American Studies scholars. Now you know where to look for information—you look in the places where the above scholars’ works might be found. Use the keywords you’ve generated to create searches in catalogs and databases.

- Explore ideas for potential topics.

- Ask a specific question about the topic you've chosen.

- Make lists of keywords relating to your topic.

- Use reference sources to help you refine your topic.

- Determine what kinds of scholars and experts would be interested in your topic .

- Based on the evidence you've collected, answer your research question with a clear statement.

- Try to think of other ways of saying your keywords. You probably already know more than you think!

- Talk to people – friends, family, professors, and librarians. What words do they use?

- Use general internet searches academically – Google and Wikipedia can help you figure out the keywords and concepts for your topic. These are where you start your research, not where you want to end up!

- Be creative – Imagine the perfect article for your topic. What might it be called?

- Use the tools within databases to help you. Most databases offer “suggested searches,” links for “subject headings,” and other tools that help you think about your topic in new ways.

- Think like a journalist. Ask yourself: Who? What? Where? When? and Why? The answers can help you figure out what aspects of a topic are most interesting to you.

When you are writing a paper or doing research on a topic, you must cite your sources. This guide will show you how.

- << Previous: General Library Information

- Next: Study Abroad >>

- Last Updated: Apr 13, 2024 9:10 PM

- URL: https://guides.nyu.edu/globalstudies

- U.S. Locations

- UMGC Europe

- Learn Online

- Find Answers

- 855-655-8682

- Current Students

UMGC Effective Writing Center Designing an Effective Thesis

Explore more of umgc.

- Writing Resources

Key Concepts

- A thesis is a simple sentence that combines your topic and your position on the topic.

- A thesis provides a roadmap to what follows in the paper.

- A thesis is like a wheel's hub--everything revolves around it and is attached to it.

After your prewriting activities-- such as assignment analysis and outlining--you should be ready to take the next step: writing a thesis statement. Although some of your assignments will provide a focus for you, it is still important for your college career and especially for your professional career to be able to state a satisfactory controlling idea or thesis that unifies your thoughts and materials for the reader.

Characteristics of an Effective Thesis

A thesis consists of two main parts: your overall topic and your position on that topic. Here are some example thesis statements that combine topic and position:

Sample Thesis Statements

Importance of tone.

Tone is established in the wording of your thesis, which should match the characteristics of your audience. For example, if you are a concerned citizen proposing a new law to your city's board of supervisors about drunk driving, you would not want to write this:

“It’s time to get the filthy drunks off the street and from behind the wheel: I demand that you pass a mandatory five-year license suspension for every drunk who gets caught driving. Do unto them before they do unto us!”

However, if you’re speaking at a concerned citizen’s meeting and you’re trying to rally voter support, such emotional language could help motivate your audience.

Using Your Thesis to Map Your Paper for the Reader

In academic writing, the thesis statement is often used to signal the paper's overall structure to the reader. An effective thesis allows the reader to predict what will be encountered in the support paragraphs. Here are some examples:

Use the Thesis to Map

Three potential problems to avoid.

Because your thesis is the hub of your essay, it has to be strong and effective. Here are three common pitfalls to avoid:

1. Don’t confuse an announcement with a thesis.

In an announcement, the writer declares personal intentions about the paper instead stating a thesis with clear point of view or position:

Write a Thesis, Not an Announcement

2. a statement of fact does not provide a point of view and is not a thesis..

An introduction needs a strong, clear position statement. Without one, it will be hard for you to develop your paper with relevant arguments and evidence.

Don't Confuse a Fact with a Thesis

3. avoid overly broad thesis statements.

Broad statements contain vague, general terms that do not provide a clear focus for the essay.

Use the Thesis to Provide Focus

Practice writing an effective thesis.

OK. Time to write a thesis for your paper. What is your topic? What is your position on that topic? State both clearly in a thesis sentence that helps to map your response for the reader.

Our helpful admissions advisors can help you choose an academic program to fit your career goals, estimate your transfer credits, and develop a plan for your education costs that fits your budget. If you’re a current UMGC student, please visit the Help Center .

Personal Information

Contact information, additional information.

By submitting this form, you acknowledge that you intend to sign this form electronically and that your electronic signature is the equivalent of a handwritten signature, with all the same legal and binding effect. You are giving your express written consent without obligation for UMGC to contact you regarding our educational programs and services using e-mail, phone, or text, including automated technology for calls and/or texts to the mobile number(s) provided. For more details, including how to opt out, read our privacy policy or contact an admissions advisor .

Please wait, your form is being submitted.

By using our website you agree to our use of cookies. Learn more about how we use cookies by reading our Privacy Policy .

Find anything you save across the site in your account

The Philosopher Chef

By Jane Kramer

In 1997, in Amsterdam, Yotam Ottolenghi finished writing the last chapter of his master’s thesis on the ontological status of the photographic image in aesthetic and analytic philosophy, rode his bicycle to the post office, and sent copies of the manuscript home to Israel. It was his second year away. He was twenty-nine, and nearing the end of an adventure in indecision that began a few months after he had completed the coursework for a fast-track, interdisciplinary bachelor’s and graduate degree at Tel Aviv University—known among students as “the genius program,” because only fifteen freshmen a year were admitted—and decamped with his boyfriend to sample the famously accessible offerings of the city of marijuana cafés, Ecstasy raves, and breakfast hams. When he wasn’t celebrating his release from school, he worked. He edited the Hebrew pages of a Dutch-Jewish weekly known by the acronym NIW , plowed through the essays of Ernst Gombrich, passed the qualifying exams for a doctorate in the United States—he was thinking comparative literature, at Yale—sat through long nights as a desk clerk at the kind of hotel he wouldn’t recommend, and wrote his thesis. “I’m incredibly self-disciplined,” he says. “I never would have not written it.”

One copy went to his thesis adviser in Tel Aviv, and another to Yehuda Elkana, the philosopher who created the genius program. A third copy—“the one I dreaded sending”—went to his parents in Jerusalem, where his father was a chemistry professor at Hebrew University and his mother, a former teacher and herself the daughter of a professor, was at the Education Ministry, running the country’s high schools. It was a moment of truth, Ottolenghi says. He slipped a note into the envelope—“actually, buried it in the manuscript”—which read, “Here is my dissertation. I’ve decided to take a break from academia and go to cooking school.” A few months later, he was in London, rolling puff pastry at the Cordon Bleu.

The moral is that smart people can be masters of many trades, though Ottolenghi claims that it took him a lot longer to “really experience pastry with my hands” (six months) than to make his way through Hegel (an excruciating few weeks). At forty-three, he is not much changed from the recovering geek of his Amsterdam years—lanky, loping, and quite tall, with the same short, sticking-up dark hair and fashionably stubbled chin, and even a version of the same black-rimmed student glasses. The difference is that today he wears the happy smile of a man who has left behind “The Phenomenology of Mind” for baked eggplants with lemon thyme, za’atar, pomegranate seeds, and buttermilk-yogurt sauce—and, in the process, become the pen, prime mover, and public face of a partnership of four close colleagues who have quietly changed the way people in Britain shop and cook and eat.

At last count, his eponymous reach extended to two hugely popular London restaurants, the flagship Ottolenghi, in Islington, and, in Soho, NOPI (for North of Piccadilly, but known to foodies as “Ottolenghi’s new place”), as well as three packed gourmet delis, in Notting Hill, Kensington, and Belgravia, which are never without his favorite pastries and his signature platters of butternut-squash salad, roasted aubergine with yogurt topping, grilled broccoli with chili and fried garlic, and fresh green beans. The delis, along with the Islington restaurant, also provide a catering service that will deliver a dinner party to your door or, if you happen to be the Queen, put together a groaning board of snacks (as in “golden and candy beetroot, orange, and olive salad with goat’s cheese, red onion, mint, pumpkin seeds, and orange blossom dressing”) for the eight hundred and fifty people sipping champagne at your jubilee party at the Royal Academy of Arts.

Ottolenghi himself is the author of a weekly food-and-recipe column in the Guardian and a visually irresistible vegetable cookbook called “Plenty”—proof that an education in aesthetics is never wasted—and, with Sami Tamimi, his Palestinian executive chef and one of the early Ottolenghi partners, the co-author of two other cookbooks, the latest of which, “Jerusalem,” is about the food of their home town and the rich symbiosis of Arab and Jewish culinary traditions that survives in the markets and kitchens of an otherwise fractured city. (The book came out in Britain and America this fall, but the British got a preview late last year, when Ottolenghi became the peripatetic guide and narrator of a BBC documentary about his research, “Jerusalem on a Plate.”)

No one who has grown up in the Mediterranean Middle East can really live without the colors and textures and tastes of home. The food that Ottolenghi serves and writes about often includes them all, but it isn’t ethnic cooking, grounded in one tradition, and it certainly isn’t fusion cooking, or its muddled suburban hybrids. He uses the fish and meat and produce that everyone in Britain eats, and then, he says, “borrows from here and there” the tastes that will produce a recipe he likes. His instincts are collaborative and practical. When he started the Guardian column, six years ago, he wanted to create recipes that a home cook could pretty much put together from the shelves of a decent supermarket. (At first, he sent them to friends to test. His bottom line: a harried child-minder in Hackney, with two children of her own to feed.) He was wrong about supermarkets. But his column was so successful that the chain Waitrose began to stock his favorite condiments and spices. And he eventually launched an extensive online catalogue, in the hope of restoring domestic calm to readers like the woman who wanted to make his whitefish-grapefruit-and-fennel seviche. She ignored his advice about the quarter teaspoon of dried fennel pollen—“Don’t worry if you can’t get it, though. This cured fish dish will still taste great”—and wrote to the paper, “I’m a bit of a Yotam fan, but his mere mention fills my husband (who does most of the shopping) with dread. This week’s ‘dried fennel pollen’ might send him over the edge.”

Ottolenghi’s first word was ma . He didn’t mean “mama,” and he didn’t mean marak , which is “soup” in Hebrew. He meant the croutons that his mother scattered on the tray of his high chair while the soup was simmering. (“Store-bought croutons,” he maintains.) He can still name everything his parents cooked, from his mother’s beef curry, stuffed red peppers, and gazpacho to his father’s polpettone and polenta. His older sister, Tirza Florentin—a businesswoman who lives in Tel Aviv with her family—says that, as a boy in Jerusalem, he was “very passionate about food,” but much more interested in talking about what he ate and where it came from than in actually cooking any. It was a household of cosmopolitan tastes and backgrounds. Ottolenghi’s mother, who comes from a Berlin Jewish academic family (her uncle was the modernist architect and critic Julius Posener), had arrived in Palestine via Sweden, where she was born, in 1938, the same year that his father’s Florentine merchant family arrived from Italy. Two prominent, secular, Zionist clans had pulled up stakes in the wake of the Hitler-Mussolini military pact and, with it, the certainty of disaster.

Ottolenghi calls them a “strong-minded” and resilient people—smart (one grandfather started the mathematics department at Tel Aviv University) and, like him, masters of many trades (one grandmother worked for Mossad, forging documents for the agents who, most famously, captured Adolf Eichmann in Buenos Aires and delivered him to an Israeli prison). His sister calls it a family of high unstated expectations “that were simply something we grew into.” The burden of them fell on Yotam when he was twenty-three, and his younger brother, Yiftach, was killed by friendly fire during field exercises toward the end of his military service. “For Yotam, I think it was a tragedy on top of a tragedy,” Florentin says. “Yiftach had been the star; he was outspoken, charming, always in trouble—making us laugh—and very bright. Yotam was the reserved one then. And, like me, he was in a kind of under-the-surface competition with our brother. He wanted to find his niche. When Yiftach died, we were very concerned about how my father would get through the loss. He was a conservative person, which made it terrible for Yotam. Not talking to him about being gay—that was the price he had to pay for a long time.”

Link copied

Every Israeli boy spends three years immediately after high school in the Israel Defense Force. (Girls spend two.) Ottolenghi had studied Arabic in school—in part, in the hope of avoiding assignment to a fighting unit. He succeeded, and went to Army-intelligence headquarters instead. “Otherwise, I was a conformist boy,” he says. “I studied physics and math because my best friend was good at that, but I was really much more interested in literature. I read a lot in the Army, I had a good time, and made lots of friends, and went home at night for dinner.” A few months before his discharge, he fell in love with a twenty-five-year-old Tel Aviv psychology student named Noam Bar, and that fall—after a summer in Berlin, learning German—he moved to Tel Aviv, started college, and began experimenting with his father’s Florentine pasta sauces. (Bar did the dishes.) He also managed to land a part-time job on the news desk at Haaretz . “I’d arrive at four-thirty in the afternoon, when the news was coming in fast,” he says. “It was very exhilarating—everybody was young, everybody smoked. I was going to become a journalist if not a chef.” His parents were still thinking “a professor.” Four years later, with a thesis to write, he left for Amsterdam with Bar. “We arrived the month of the Rabin assassination, and joined the demonstration,” he says. “That death was the end of a moment of high optimism at home. Israel became a very closed culture again, living according to its own rules. There was a desire growing in me to live somewhere else.”

In Amsterdam, he began to cook in earnest. He prowled the fishmongers for mackerel and herring. He stopped at the butchers he passed for bones, and made his own stocks. He roasted, sautéed, and baked his way through Julia Child, started ordering from Books for Cooks, and “cooked for everyone who asked.” So many people did ask that, at dinnertime, his walkup, on Herengracht, turned into an open house. “We were his guinea pigs,” a Tel Aviv friend named Ilan Safit, who was studying in Amsterdam at the time, told me. “I had a Dutch girlfriend. We were living practically hand to mouth, but even after we got married we must have eaten at Yotam’s every other night. He loved the kitchen. He was obviously an intellectual—a first-class intellectual—but he wasn’t happy writing philosophy in his study. He was happy feeding people. He said, ‘Ilan, I don’t want to go back to academia, I don’t want to live with books.’ ’’

His father was shocked. “This is not a very good idea” was his reply to the note buried in Ottolenghi’s thesis. His adviser, Ruth Ronen, puts it this way: “Cooking? It was like a metamorphosis, it was so extreme. His thesis was excellent, very thoughtful and intriguing. He had a natural inclination to philosophy—you could feel the urge—and the world of cooking was so far from that; I couldn’t even see the connection. Was I disappointed? In a way, yes.” But his sister told him, “This is the coolest thing.” His mother wanted to see him happy. And his old mentor, Yehuda Elkana (who died in Jerusalem this fall), even claimed some credit for the change. “We had hundreds of candidates for the program,” he told me. “We were looking for the few who had an original attitude to something in life. It could be anything. How you made love, how you made bread, how you ‘made’ philosophy. Yotam had that curiosity and enthusiasm. He would come to my home, and I’d cook for him. I’m a very good cook, so I may have had an influence. Even then, he was proof that the division academics make between ‘cognitive’ and ‘emotional’ is bullshit.”

Ottolenghi still makes the puff pastry that he learned at the Cordon Bleu. He loved the pastry part of his cooking course; he found “the physicality of pastry” soothing. But he found the savory part—which, in the hierarchy of professional kitchens, is called “cuisine”—so pressured and unnerving that it nearly ended his new career. “I thought, This will only get worse,” he says, and it did. His first cooking job was a trial run at a London restaurant called the Capital. He spent three mind-numbing months whipping egg whites for the pastry chef to fold, and then was promoted to full time in the cold-starter section. “On my first day, the sous-chef said, ‘O.K., now make me a lobster bisque and an amuse-bouche.’ It was terrifying. I couldn’t sleep all night, and by the middle of the next day I was so exhausted that I took my scooter and went home and never went back. I said to Noam, ‘This is not a normal job.’ ”

He was rescued by the well-known London chef Rowley Leigh—an experience on the order of starting out in New York with, say, Daniel Boulud. (“Not charitable, but sweet,” Ottolenghi describes him. “I doubt if he likes my food.”) Leigh placed him at a small restaurant that he had opened in Kensington called Launceston Place, where he quickly became the pastry chef. “I could do what I did best, and I was really teaching myself, because the menu was basically French-English, and French pastry wasn’t my thing. I wanted the vibrancy and freshness of California pastry”—the Ottolenghis had spent a sabbatical year in Mill Valley, when Yotam was ten—“so I bought Alice Waters, and Emily Luchetti’s ‘Stars Desserts.’ I made fresh-fruit galettes and meringue pies. I stayed a year and got a lot of confidence. You can do that with pastry; you learn a certain range of processes, and it’s very contained. I began to think that maybe I had a pastry talent and should get a pâtisserie job—see how it all worked, napoleons, pâte à choux, crème pâtisserie.”

He went to work for a chain of bakeries—a franchise spinoff of the entrepreneurial restaurateur Raymond Blanc. The bakery turned out to be a factory, where the crème pâtisserie came out of a machine. Plus, it was freezing. “Fifteen degrees,” Ottolenghi says. “The guy next to me said we’d be warmer driving a minicab. I did twenty-five shifts, and, on the one where I worked a machine that poured chocolate mousse into sponge cake, I decided that this was not what I needed to know to further my career.” A few days later, he got on his scooter and rode up and down the streets of central London, “searching for bakeries that looked exciting.” On a quiet street in Knightsbridge, he spotted a small traiteur called Baker & Spice, peered through the window, and ran in. “It was completely magical,” he says. “I saw all these walls and counters covered with a marvellous mix of food. There were Middle Eastern salads, Italian Caprese salads, rotisserie chickens, even char-grilled broccoli, and you could see into a small kitchen open to a mews garden, full of light. You could even see Ringo Starr’s house.” A young chef, about his own age, came out of the kitchen and said, “I’m Sami. I’m from Tel Aviv.” Ottolenghi said, “Me, too.”

Sami Tamimi was seventeen when he moved out of his father’s house, in the Old City of East Jerusalem. It wasn’t entirely his decision. “My family was a very traditional Muslim house,” he told me one day in Acton, in West London, where he lives with an English property-research analyst named Jeremy Kelly, his partner of eight years. We were in the kitchen. I had found him making a cheesecake for us to have with coffee; the cake was from a television recipe he had just downloaded, but the gesture of hospitality was timeless, tacit, and very Arab. “I had six siblings and five step-siblings; every time I came home, there was another baby born. And when the whole sexual thing came up—well, in Palestine you can’t tell anyone how you really feel. I was fifteen when I left school; I always knew there was something else in life.” At the time, Tamimi was working at the Mount Zion, a West Jerusalem hotel whose German chef, seeing the makings of a cook, had promoted him from kitchen porter to “head breakfast chef,” a job Tamimi describes as an education in scrambled eggs. Three years later, he said goodbye to his friends, and left for Tel Aviv.

He says that he could “breathe” in Tel Aviv, a city as open then as Jerusalem was staid. He acquired an Anglo-Israeli boyfriend and a decent restaurant job, discovered his talent for catering home-cooked food (“After all those years of dreaming about European food, I realized that the food I grew up with was the food I did best”), and settled into the kind of “good” neighborhood that he describes dryly as “quite unusual for an Arab living in Tel Aviv.” He stayed for the next twelve years. He liked the city—the freedom he’d felt at first, the European cafés and restaurants, and, above all, the chef’s job that he eventually found at Lilith, a fashionable new brasserie whose owner, a transplanted American, served an eclectic “California-Mediterranean” mix of grilled meats and vegetables that was, in many ways, a version of the kind of food Tamimi cooks now. One night, a woman visiting from England ate at Lilith and asked to meet him. She said that she loved his food, and that there would always be a job waiting for him, with her, in London. In 1997, he called the woman, got on a plane, and started working at Baker & Spice—“creating the concept” that made Ottolenghi stop his scooter, on a spring day two years later, and run in, asking for a job.