India Votes 2024

Lok Sabha election result: BJP-led NDA ahead, but margin narrower than predicted

BJP Tamil Nadu chief K Annamalai trails in Coimbatore Lok Sabha seat

Why the BJP took a hit in Uttar Pradesh

West Bengal: Congress’s Adhir Ranjan Chowdhury trails TMC’s Yusuf Pathan in Baharampur

Lok Sabha elections 2024: The story of the rise and fall of the Election Commission of India

BJP’s Smriti Irani trails in Uttar Pradesh’s Amethi Lok Sabha seat

CEC on Modi’s anti-Muslim speeches: ‘We decided not to touch top two leaders of BJP and Congress’

Suspended JD(S) leader Prajwal Revanna trails in Karnataka’s Hassan seat

Indore: NOTA votes over 2 lakh in constituency where Congress candidate joined BJP days before polls

Brij Bhushan Sharan Singh’s son wins Kaiserganj seat in Uttar Pradesh

BR Ambedkar in London: A thesis completed, a treaty concluded, a ‘bible’ of India promised

An excerpt from ‘indians in london: from the birth of the east indian company to independent india’, by arup k chatterjee..

About two decades ago, when [Subhash Chandra] Bose was still at Cambridge, a letter dated September 23, 1920 arrived at Professor Herbert Foxwell’s office at the London School of Economics. It was written by Edwin R Seligman, an economist from Columbia University, introducing an exceedingly talented scholar – Mr Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar. Two months later, Foxwell wrote to the secretary of the School that there was no more intellect that the Columbia graduate could conquer in London.

The first Dalit to study at Bombay’s Elphinstone College, Ambedkar, was awarded a Baroda State Scholarship that took him to Columbia University in 1913. Three years later, he found his way to London, desirous of becoming a barrister as well as finishing a doctoral dissertation on the history of the rupee. Ambedkar enrolled at Gray’s Inn, and attended courses on geography, political ideas, social evolution and social theory at London School of Economics, at a course fee of £10.10s.

In 1917, Ambedkar was invited to join as Military Secretary in Baroda, earning at the same time a leave of absence of up to four years from the London School of Economics. Back in India, he taught for a while as a professor in Sydenham College in Bombay, while also being one of the key intelligencers on the condition of “untouchables” in India for the government, during the drafting of the Government of India Act of 1919.

In late 1920, Ambedkar was to return to London, determined more than ever before, not to spare a farthing beyond his breathing means on the city’s allurements. Each day, the aspiring barrister woke up at the stroke of six. After a morning’s morsel, he moseyed into the crowd of London to find his way into the British Museum.

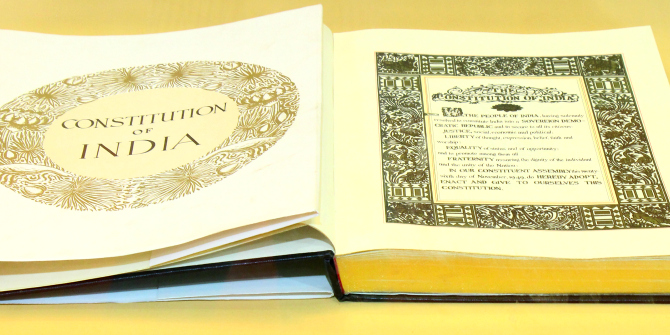

At dusk, he would leave his seat reluctantly – after being made to scurry out by the librarian and the guards – his pockets sagging under the notes that would finally become his thesis, The Problem of the Rupee , some of whose guineas would eventually find their home in the Constitution of India that he was going to author about three decades later. Back at his lodging at King Henry’s Road in Primrose Hill, mostly on foot, Ambedkar would live on sparsely whitened tea and poppadum late into the night.

It was here that the daughter of Ambedkar’s landlady, Fanny Fitzgerald, a war widow, found her affections strangely swayed by the Indian scholar. Fitzgerald was a typist at the House of Commons. She lent him money in difficult circumstances and volunteered to introduce him to people in governance, with whom he could discuss the Dalit question that was raging in India.

An apocryphal story goes that Miss Fitzgerald once gave Ambedkar a copy of the Bible. On receiving it, the future Father of the Indian Constitution promised to dedicate a bible to her of his own authoring. True to his commitment, he would fondly dedicate his book What Congress and Gandhi Have Done to the Untouchables (1945) to “F”. The incident, when that promise was exchanged, occurred after Ambedkar was called to the Bar in 1923.

In March that year, his doctoral thesis ran into trouble possibly because of its radical approach to the history of Indian economy under the British administration. He might have taken the subtle hint that passages in his work needed tempering – a notion that a man of his vision was likely to have quietly pocketed more as a compliment than an insult.

Ambedkar would have been happy to chisel the nose from his David for the show, like Michelangelo had four centuries ago in order to appease the connoisseur-like pretense of Piero Soderini, who had quipped, “Isn’t the nose a little too thick?” That done, Ambedkar resubmitted his thesis in August. It was approved two months later and published almost immediately thereafter. He expressed gratitude to his professor, Edwin Cannan, who, in turn, wrote the preface to his thesis, before Ambedkar travelled to Bonn for further studies.

Babasaheb, as he was now beginning to be called, was to return to London for each of the three Round Table Conferences held between 1930 and 1932. Two months before the Third Round Table Conference – in which both Labour and the Congress were absentees – Ambedkar and Gandhi reached a historic settlement in the Poona Pact. In September 1932, from the Yerwada prison near Bombay, Gandhi began a fast unto death protesting against the Ramsay MacDonald administration that was determined to divide India into provincial electorates on the basis of caste and social stratification.

In the pact signed with Madan Mohan Malviya, Ambedkar settled for 147 seats for the depressed classes. But the pact to which he was forsworn – tacitly made in London with Fanny Fitzgerald – that of writing the bible of modern India, was brewing like a storm that would take the form of an open battle between him and Gandhi, in the years of the Second World War.

Despite the strong network of Indians at the London School of Economics, Ambedkar chose not to hobnob with India League members. What might have been a sort of marriage-made-in-heaven between him and [VK Krishna] Menon was forestalled. If Menon was Nehru’s alter ego, he would also be instrumental in shaping the early career of the man to become an alter ego – principal secretary –to Indira Gandhi.

In the winter of 1935, a twenty-something Parmeshwar Narain Haksar arrived in London, enrolled as a student at the University College. The following year, he made an unsuccessful attempt for the civil services. In 1937, Haksar became a Fellow of the Royal Anthropological Institute, a distinction conferred on him with support from noted anthropologist Bronislaw Malinowski.

Although Haksar also studied at the London School of Economics, it probably never became public knowledge if he had acquired formal degrees from either university. Whether or not he did, as a scholar he commanded great attention from British intellectuals, especially in his arguments on the crisis of education in India, which he reckoned had been tailored to perpetuate British imperial interests and low levels of literacy in the colony.

Haksar was to be called to Bar at the Lincoln’s Inn, but, at the beckoning of Nehru, he would join the Indian Foreign Service in 1948. His red days in London were to yield him lifelong companions. In the 1930s, the Comintern came up with the policy of hatching popular fronts all across Europe with which to counter the growing threat of Nazism and Fascism. It was a phase in European ideologies that strongly affected British politics, and popular movements led by Labour leaders and student communists in London – a cosmopolitan and unswervingly left-leaning outlook that shaped much of the administration and policies of independent India until the years of the Emergency.

A socialist himself, Haksar held an influential position in the Federation of Indian Societies in UK and Ireland besides becoming the editor of its magazine, The Indian Student . His links with the Communist Party of Great Britain, Rajani Palme Dutt and the Soviet undercover agent at Cambridge, James Klugman – indeed with almost anyone of some consequence who supported the cause of Indian liberation – was more than enough for Scotland Yard to keep him closely watched in London.

In September 1941, when the India League organised a commemoration at the Conway Hall in Red Lion Square for the late Rabindranath Tagore a few months after his demise, Scotland Yard obliged by adding a leaf to their surveillance files. Inaugurated by M Maisky, a Russian ambassador, it was just one in a sea of events concerning India that the Yard and other intelligencers of His Majesty’s Government would tolerate during the interwar years. Almost all such gatherings featured subversive pamphlets and books published by the League and similar organisations that were openly lauded by Soviets and Soviet sympathisers.

It was just as well that Nehru also had to tolerate that under the shield of Haksar’s own watch a new romantic plot thickened around Primrose Hill, that of his daughter Indira and future son-in-law, Feroze. Feroze had his flat at Abbey Road and Haksar lived half a mile away, at Abercorn Place. Haksar was befriended by the Gandhis – Indira and Feroze – who introduced him to Sasadhar Sinha of the Bibliophile Bookshop. That, besides the India League and Allahabad connection, not to mention Haksar’s enviable culinary skills, ensured that he was soldered to the future of the Gandhis.

The future of the man who had leant the family his coveted surname would also take a blow on the burning issue of caste. Gandhi was not to be remembered as the sole nemesis of the British Empire. In an interview given to the BBC in 1955, Babasaheb indicated that one of the biggest reasons behind Clement Attlee handing over the reins of the Indian administration so suddenly was the persistent fear of a massive armed uprising in the colony.

He implied that the road to independence had already been paved by the Azad Hind Fauj brigadiered by Netaji. Bose had departed from London during Ambedkar’s days in the London School of Economics. But, he would return in Haksar’s time.

Centenary of Dr. B.R. Ambedkar's enrolment as an advocate

- Certificate

- Application

- Mahad Satyagraha

- Publications

- Photo Gallery

Photo Credit : High Court of Bombay

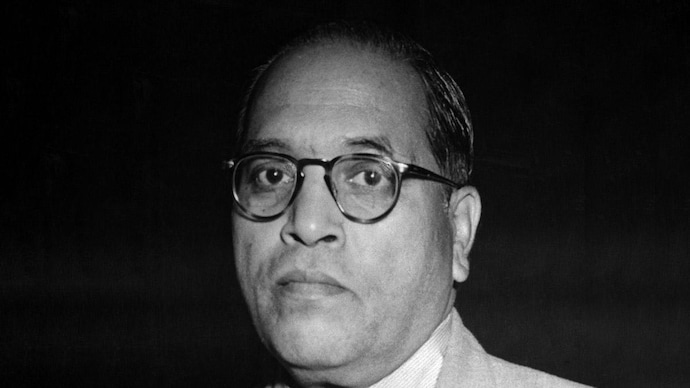

Dr. Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar

Dr. Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar (1891-1956) was born on 14 April 1891 in Mhow Cantonment, Madhya Pradesh. He completed his primary schooling in Satara, Maharashtra and completed his secondary education from Elphinstone High School in Bombay. His education was achieved in the face of significant discrimination, for he belonged to the Scheduled Caste (then considered as ‘untouchables’). In his autobiographical note ‘Waiting for a Visa’, he recalled how he was not allowed to drink water from the common water tap at his school, writing, "no peon, no water".

Dr Ambedkar graduated from Bombay University in 1912 with a B.A. in Economics and Political Science. On account of his excellent performance at college, in 1913 he was awarded a scholarship by Sayajirao Gaikwad, then Maharaja (King) of Baroda state to pursue his M.A. and Ph.D. at Columbia University in New York, USA. His Master's thesis in 1916 was titled “The Administration and Finance of the East India Company”. He submitted his Ph.D. thesis on “The Evolution of Provincial Finance in India: A Study in the Provincial Decentralization of Imperial Finance”.

After Columbia, Dr. Ambedkar moved to London, where he registered at the London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE) to study economics, and enrolled in Grey’s Inn to study law. However, due to lack of funds, he had to return to India in 1917. In 1918, he became a Professor of Political Economy at Sydenham College, Mumbai (erstwhile Bombay). During this time, he submitted a statement to the Southborough Committee demanding universal adult franchise.

In 1920, with the financial assistance from Chatrapati Shahuji Maharaj of Kolhapur, a personal loan from a friend and his savings from his time in India, Dr. Ambedkar returned to London to complete his education. In 1922, he was called to the bar and became a barrister-at-law. He also completed his M.S.c. and D.S.c. from the LSE. His doctoral thesis was later published as “The Problem of the Rupee”.

After his return to India, Dr Ambedkar founded Bahishkrit Hitkarini Sabha (Society for Welfare of the Ostracized) and led social movements such as Mahad Satyagraha in 1927 to demand justice and equal access to public resources for the historically oppressed castes of the Indian society. In the same year, he entered the Bombay Legislative Council as a nominated member.

Subsequently, Dr. Ambedkar made his submissions before the Indian Statutory Commission also known as the ‘Simon Commission’ on constitutional reforms in 1928. The reports of the Simon Commission resulted in the three roundtable conferences between 1930-32, where Dr. Ambedkar was invited to make his submissions.

In 1935, Dr. Ambedkar was appointed as the Principal of Government Law College, Mumbai, where he was teaching as a Professor since 1928. Thereafter, he was appointed as the Labour Member (1942-46) in the Viceroy’s Executive Council.

In 1946, he was elected to the Constituent Assembly of India. On 15 August 1947, he took oath as the first Law Minister of independent India. Subsequently, he was elected Chairperson of the Drafting Committee of the Constituent Assembly, and steered the process of drafting of India’s Constitution. Mahavir Tyagi, a member of the Constituent Assembly, described Dr. Ambedkar as “the main artist” who “laid aside his brush and unveiled the picture for the public to see and comment upon”. Dr. Rajendra Prasad, who presided over the Constituent Assembly and later became the first President of the Indian Republic, said: “Sitting in the Chair and watching the proceedings from day to day, I have realised as nobody else could have, with what zeal and devotion the members of the Drafting Committee and especially its Chairman, Dr. Ambedkar in spite of his indifferent health, have worked. We could never make a decision which was or could be ever so right as when we put him on the Drafting Committee and made him its Chairman. He has not only justified his selection but has added luster to the work which he has done.”

After the first General Election in 1952, he became a member of the Rajya Sabha. He was also awarded an honorary doctorate degree from Columbia University in the same year. In 1953, he was also awarded another honorary doctorate from Osmania University, Hyderabad.

Dr. Ambedkar's health worsened in 1955 due to prolonged illness. He passed away in his sleep on 6 December 1956 in Delhi.

References:

- Vasant Moon (eds.), Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar Writings And Speeches, (Dr. Ambedkar Foundation, Ministry of Social Justice & Empowerment, Govt. of India, 2019) (Re-print)

- Dhananjay Keer, Dr. Ambedkar Life and Mission, (Popular Prakashan, 2019 Re-print)

- Ashok Gopal, A Part Apart: Life and Thought of B.R. Ambedkar, (Navayana Publishing Pvt. Ltd., 2023)

- Narendra Jadhav, Ambedkar: Awakening India's Social Conscience, (Konark Publishers Pvt. Ltd., 2014).

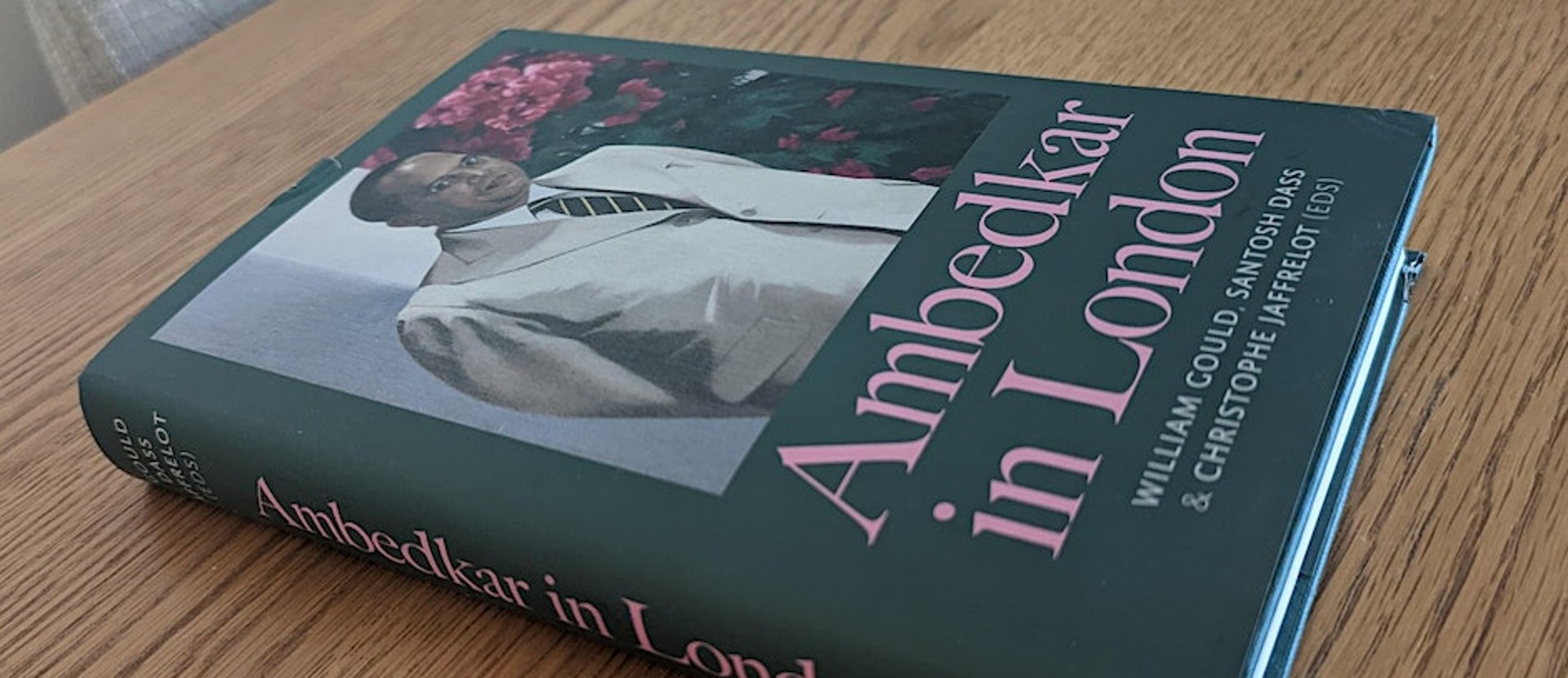

- William Gould, Santosh Dass and Christophe Jaffrelot (eds.), Ambedkar In London, (C. Hurst and Co. Publishers Ltd., 2022).

- Sukhadeo Thorat and Narender Kumar, B.R. Ambedkar: Perspectives on Social Exclusion and Inclusive Policies (Oxford University Press, 2009).

- Constituent Assembly Debates

- India Today

- Business Today

- Reader’s Digest

- Harper's Bazaar

- Brides Today

- Cosmopolitan

- Aaj Tak Campus

- India Today Hindi

Get 72% off on an annual Print +Digital subscription of India Today Magazine

Why publication of b.r. ambedkar’s thesis a century later will be significant, a contemporary relevance of the thesis, written as part of ambedkar’s msc degree at the london school of economics, is that it argues for massive expenditure on heads like defence to be diverted to the social sector.

Listen to Story

Now, over a century after it was written, Ambedkar’s hitherto unpublished thesis on the provincial decentralisation of imperial finance in colonial times will finally see the light of the day. The Dr Babasaheb Ambedkar Source Material Publication Committee of the Maharashtra government plans to publish the thesis that was written by Ambedkar as part of his MSc degree from the London School of Economics (LSE). The thesis, ‘Provincial Decentralisation of Imperial Finance in British India’, will be part of the 23rd volume of Ambedkar’s works to be published by the committee and will give a glimpse into the works of Ambedkar, the economist. Notably, the dissertation argues for expenditure on heads like defence to be diverted for social goods like education and public health.

The source material committee, which was set up in 1978, has published 22 volumes on Ambedkar’s writings since April 1979. “This volume will have two parts. One will contain the MSc thesis and the other will have communication and documents related to his MA, MSc, PhD and bar-at-law degrees,” confirmed Pradeep Aglave, member secretary of the committee. He added that the MSc thesis had been submitted to the LSE in 1921. Veteran Ambedkarite and founder of the Dalit Panthers, J.V. Pawar, who is a member of the committee, said it was significant that the thesis was being published over a century after it was written. Pawar played a pivotal role in ensuring that the committee was set up.

“This work deals with taxation and expenditure. The contemporary relevance of this thesis is that it seeks a progressive taxation based on income levels. Ambedkar argued that expenditure on heads like defence was huge and this needed to be diverted to social needs like education, public health, and water supply,” said Sukhadeo Thorat, economist and former chairman of the University Grants Commission (UGC). Thorat was among those instrumental in the source material committee getting a copy of the thesis from London.

“The sixth volume (1989), published by the source material committee, contains Ambedkar’s writings on economics. This includes his works like ‘Administration and Finance of the East India Company’ (1915) and the ‘Problem of the Rupee: Its Origin and Its Solution’ (1923). However, this MSc thesis on provincial finance could not be included in it because it was not available then,” said Thorat.

J. Krishnamurty, a Geneva-based labour economist located the MSc thesis in the Senate House Library in London and approached Thorat who, in turn, communicated with Gautam Chakravarti of the Ambedkar International Mission in London. Santosh Das, another Ambedkarite from London, paid the fees for permission to reproduce the work in copyright. The soft copy of the thesis was sent to the source material committee on November 18, 2021.

In addition to the MSc thesis, the communication and letters related to his academics, such as the MA, PhD, MSc and DSc and bar-at-law including LLD (an honorary degree that was awarded to Ambedkar by the Columbia University in 1952after he finished drafting the Constitution of India, which remains one of his most significant contributions to modern India), were also arranged and compiled by Krishnamurty, Thorat and Aglave. This also includes the courses done by Ambedkar for his MA and pre-PHD at the Columbia University. These details are being published for the first time.

Ambedkar’s biographer Changdev Bhavanrao Khairmode, writes how Ambedkar worked untiringly in London for his MSc. Ambedkar secured admission for his MSc in the LSE on September 30, 1920 by paying a fee of 11 pounds and 11 shillings. He was given a student pass with the number 11038.

Ambedkar had prepared for his MSc in Mumbai, yet he began studying books and reports from four libraries in London, namely the London University’s general library, Goldsmiths' Library of Economic Literature and the libraries in the British Museum and India Office. In London, Ambedkar would wake up at 6 am, have the breakfast served by his landlady and rush to the library for his studies. Around 1 pm, he would take a short break for a meagre lunch or have just a cup of tea and then return to the library to study till it closed for the day.

“He would sleep for a few hours. He would stand at the doors of the library before it opened and before others came there,” says Khairmode in the first volume of his magisterial work on Ambedkar (Dr Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar, Volume I) that was first published in 1952. The library staff in the British Museum would tell Ambedkar that they had not seen a student like him who was immersed in his books and they also doubted if they would get to see one like him in the future!

The volume also contains a letter written by Ambedkar in German on February 25, 1921 to the University of Bonn seeking admission. Ambedkar wanted to study Sanskrit language and German philosophy in the varsity’s department of Indology. In school, Ambedkar was discriminated against on grounds of caste and not allowed to learn Sanskrit. He had to learn Persian instead. Ambedkar secured admission to Bonn University but had to return to London three months later to revise and complete his DSc thesis.

Ambedkar completed his DSc in 1923 under the guidance of Professor Edwin Cannan of the LSE on the problem of the rupee, which is described as a “remarkable piece of research on Indian currency, and probably the first detailed empirical account of the currency and monetary policy during the period”.

Ambedkar was among the first from India to pursue doctoral studies in economics abroad. He specialised in finance and currency. His ‘The Evolution of Provincial Finance in British India: A Study in the Provincial Decentralisation of Imperial Finance (1925)’, carried a foreword by Edwin R.A. Seligman, Professor of Economics, Columbia University, New York. Ambedkar also played a pivotal role in the conceptualisation and establishment of the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) in 1935.

Subscribe to India Today Magazine

All About Ambedkar

Issn 2582-9785, a journal on theory and praxis, on economics, banking and trades: a critical overview of ambedkar's “the problem of the rupee”.

Janardan Das

The Problem of Rupee is 257-page long paper written by Dr. B. R. Ambedkar that he presented as his Doctoral thesis at the London School of Economics (LSE) in March 1923. In it, Ambedkar tried to explain the troubles that were associated with the national currency of India - the Rupee. He argued against the British ploy to keep the exchange rate too high to facilitate the trade of their factory products.

In this article, I have tried to summarize the aforesaid book by Dr. Ambedkar. I have also tried to focus on how he advances his speech depicting the ups and downs of the Indian economy and currency. He introduces us to the characteristics of trade and business in our country even from the time when it was divided into several monarchical regions. He proclaims that in our country, the trade of any product had been conducted through the exchanges of money and those particular products. So evidently our merchant society is typically crowned as a pecuniary society that only runs on money.

Quoting W. C. Mitchell, Ambedkar reiterates that economists say money is pivotal to every individual in a society. And without the use of money, the distribution of anything can be a matter of disagreement and disturbance. In the next few lines of his speech, in the first chapter, he describes how the standards and currency were in the time of the Mughal empire and he certainly mentioned that the economic condition of the country was far better than that of today's, because it had a world-wide boundary of trade and free use of gold mohur and the silver rupee . Actually, before the administrative and financial invasion of British, Gold and silver were the inevitable parts of the medium of exchange without any fixed ratio. Hindu emperors and the Muslim emperors had some similarity in their trading features- both of them had a permissible use of metal coin in their empire but in the Mughal empire silver coins were at the center of currency, and later gold coins took that place in the Hindi empires. Mohur and rupee were similar in size, weight and composition. But the silver currency was unknown or more precisely unpopular to the southern part of the great Indian sub-continent because of the failure of Mughal administration. Instead of such coins, they normalised pagoda , the ancient gold coin traditioned from the time of Hindu kings. Mughals made allowances to recuperate the problems regarding faulty technology of the mints. Dr. Ambedkar observes that Mughals had initiated a system of provincial mints that had been maintained or ruled by a single unit or division. That made it easy to examine the issues related to monetary funds or mints. But later, these issues continued to be grow larger and made the poor and ignorant people suffer. He also tried to conjugate the great re-coinage of 1996 (?) . In the last half of the chapter, Ambedkar compared the coins as well as the rupee in every possible way.

Our country was divided into three presidencies during the British rule. So the British government set their target to change the parallel standard popular in Mughal times into a double standard by establishing an authorised ratio of exchange between pagoda , rupee , and mohur . But somewhere their effort partially went in vain. He gave a pictorial glimpse of how Bengal took this effort and tried to fix that ratio. Mainly, these types of attempts were taken and recommended by the Court of directors. But these steps were left to carry out by many of the provincial governments of India. In the first chapter of the problem of the rupee, Dr. Ambedkar explained how silver standards had been established through the vanishing of gold currency and how it had been supplemented by the paper currency. He also retorted how the Act XXIII of 1870 actually introduced nothing new - neither the number of the coins authorised by the mints nor its tender-powers. Rather, it helped just to make some improvements in monetary laws. Since the invention of coinage people always thought that the actual value of the coin can be exact with the price of the coin legalised by the mint. So according to him, the exact value of the coin can’t however always be the same as the certified value. That’s why in foreign countries, coins will not be legal tender if they vary from their legal standards beyond a certain limit. So, making coins legal tender without defining a certain limit to its toleration certainly makes way to cheat. Convincingly, the Act set a certain legal limit to the coins of its tolerance. The act also made an improvement that was to recognise the principle of free coinage. But we can not say that this principle of free coinage was perfect in every possible way as Ambedkar himself once said in this chapter that the principle had not been paid that much attention it deserved. Though it was the very basis of well-established currency in that it has an important bearing on the cardinal question of the amount of currency inevitable for the transactions of the people. According to Ambedkar, to solve this problem, two ways can be very useful to regulate such a huge quantity of transactions. One possible way is to close the mints and to leave it to the judgment of the government to handle the currency to suit our needs. The other way is to keep the mint as it is and to leave it to the self-interest of individuals to determine the amount of currency they need. Ambedkar aptly indicated both of the similarities and contradictions of the above-mentioned Act with the other ones where surely, he finds its incapability to regulate such a large quantity of currency.

In the introduction to the third chapter, Ambedkar was concerned about the economic results of the disturbance of the ‘par’ of exchange and he narrates it as the most “far-reaching character”. Our economic world can be sectioned into two neatly defined groups of people. These two categorised community had learned to use gold and silver and their standard money or purchasing standards. By giving a reference to 1873, he said that when a large amount of gold becomes equal to a large amount of silver, it barely matters for international transactions. It doesn’t make so much difference in which of the two currencies its obligations were stipulated and realized. But due to the dislocation of the fixed ratio or par, it becomes hard to indicate particularly how much silver is equal to how much of gold from one year to another, even from month to month. This exactitude of value which is the pivotal potential of monetary exchange, makes space for ambiguities of gambling. So, flatly all countries weren’t drawn to this center of perplexities in the same degree and the same extent; but yet it’s impossible for a nation which is a part of the international commercial world to escape from being dragged into it. This was true of our country as it was of no other country. India was a silver-standard country bound to a gold-standard country, so that her economic and financial picture was at “the mercy of blind forces operating upon the relative values of gold and silver which governed the rupee-sterling exchange.” Later in the discussion, Ambedkar pointed out the burdens of Indian economy and introduced us to an index [Table-XI] chart regarding the rupee cost of gold payments which showed data from year to year. If we give pay attention to the points figured out by Ambedkar, we can see that these burdens never stop, rather it’s been increasing day by day. Gradually, it caused various policies of high taxations and rigidity in Indian finance. Dr. Ambedkar brilliantly analysed Indian budgets between 1872-1882 and he proved that hardly a year passed without making an addition to the everlasting impositions on the country. He also analysed the information found in Malwa Opium Trade and was able to find errors in the economic policies of the Indian government. The taxes that the government standardized in these trades probably help the Indian economy to feel secure around the end of 1882. The government started exercising the virtue of economy along with the increment of resources. They found cheap agency of native Indians instead of employing imported Englishmen. And it was easy to use native intellect because the Educational Reforms of 1853 clearly says about the access of natives in Indian Civil Service. Thus, he finds the British try to set up a strong economy in India under the British Raj.

In the fourth chapter of the book, Ambedkar focuses on how the establishment of a stable economic system was dependent upon the re-establishment of a common standard of value. As it was the purpose just to normalise a common standard of value, its fulfillment was by no means an easy matter. The government found mostly two ways to make an experiment or practice. First thing was to declare any of the common metal as the standard currency and the second was to let gold and silver standard countries keep to these metal currencies and to establish a fixed ratio of exchange as to turn these to metal into a common standard of value. The first idea of normalising metal currency other than gold and silver was to make other countries leave their standards in favour of gold. If we look back at the history of movements for the reform of the Indian currency, we will mainly find two movements. The movement that led to introduce a gold standard first occupies this field. Dragging a reference to a ‘Report of the Indian Currency Committee’ of 1898, Dr. Ambedkar said that the notification of 1868 had bluntly failed and this failure doesn’t affect the history because the movement had already started earlier in the sixties and the movement had still life in it. Clearly, it is shown by the fact that it was revived four years later by Sir R. Temple, when he became the Finance Minister of India, in a memorandum dated May 15, 1872.

In the next few lines, Dr. Ambedkar talks about the second movement for the introduction of the gold standard that was conducted by Colonel J. T. Smith, the able Mint Master of India. Frankly, Dr. Ambedkar mentioned that his plan was a redress for the falling exchange. In this topic, he quoted the actual speech of Smith that was published in 1876 in London. Depicting the whole principle behind the presentation of J. T. Smith, Baba Saheb found it was considerably supported by the fall of silver in British India.

Now in the fifth chapter, we come to know that once somewhere Indian economic system felt that the problem of an erosive rupee was favourably dissolved. The long-lasting concerns and niceties that lingered over a long period even for a quarter of the century could not but have been successfully compensated by the adoption of a redress like the one mentioned in the fourth chapter. But unfortunately, the system originally planned, failed to be designed into reality. In its place, a system of currency in India grew up which was the very reverse or contradictory of it. A few years later when the legislative sanction had been shown the recommendations and suggestions of the Fowler committee, the Chamberlain Commission on Indian Finance and Currency said that the government contemplated to adopt the recommendations made by the committee of 1898, but the contemporary system utterly differs from the plan and had some common feature with the theory and suggestions made by Mr. A. M. Lindsay.

According to Mr. Lindsay’s scheme, he emphasised on how to turn the entire Indian currency to a rupee currency; the government was to give rupees in almost every case in return for gold, whereas gold for rupees only in foreign dispatch of money. The project was to be implicated through the assistance in between of two offices, one was in London and the other located in here, India. The first was to sell drafts on the latter when rupees were wanted and the latter was to sell drafts on the former when gold was wanted. Unbelievably, the same or similar system prevailed in our country. It was rejected in 1898. Then gradually paper currency came up to the Indian economic realm and two reserves one of gold and other of currencies left other than gold. Ambedkar had lengthened his discussion over Indian currencies after these events.

In the sixth chapter of the book, Dr. Ambedkar said about a memorable thing that was to remind the time when all the Indian Mints were shut down to the free coinage of silver. and the economic world in India was surely divided into two parties, one in favour of the step and the other stood in opposition to the closure of the mints. Being placed in an embarrassing and contradictory position by the fall of the rupee, the British Government of the time felt anxiety to close the Mints and increase its value with a conception to sigh in relief from the burden of its gold payments. Whereas it was requested, to produce an increment of interest of the country, that such accretion in the exchange value of the rupee would cause a disaster to the entire Indian trade and industry. One of the reasons, it was argued, why the Indian industry had advanced by such leaps and bounds as it did from 1873 to 1893 was to be found in the bounty given to the Indian export trade by the falling exchange. If the fall of the rupee was discovered by the Mint closure, everyone feared that such an event was certainly bound to cut Indian trade both ways. It would give the silver-using countries a bounty as over against India and would deprive India of the bounty which is obtained from the falling exchange as over against gold-using countries.

However, in the seventh as well as the last chapter of the book, Ambedkar examined the system of the economy that was advancing towards the changes of the exchange standard in the light of the claim made on behalf of it. Though it is very much a matter of uncertainty and hard to explain the history of Indian banking, but sure if being followed, it will be easy to interpret the market, values of products. Unmistakably, the works of Ambedkar led the nation towards the development and advancement of its economics and international banking and trades.

Works Cited

Ambedkar, B. R. History of Indian Currency and Banking. Butler & Tanner Ltd.

______________. The Evolution of Provincial Finance in British India. P. S. King & Son Ltd., 1925.

______________. The Problem of the Rupee. P. S. King & Son Ltd., 1923.

Author Information

Janardan Das studies English literature at Presidency University, Kolkata.

Commentaires

Subscribe Now! Get features like

- Latest News

- Entertainment

- Real Estate

- All Lok Sabha Constituencies Results 2024

- Election Results 2024 Live

- Lok Sabha Results Live

- UP Results Live

- Maharashtra Election Results Live

- Lok Sabha Election Results

- Election Result Live

- My First Vote

- Afghanistan vs Uganda Live Score

- World Cup Schedule 2024

- World Cup Most Wickets

- Afghanistan vs Uganda

- The Interview

- World Cup Points Table

- Web Stories

- Virat Kohli

- Mumbai News

- Bengaluru News

- Daily Digest

- Election Schedule 2024

Archives released by LSE reveal BR Ambedkar’s time as a scholar

Archival documents released by the london school of economics (lse) cast new light on the iconic leader’s student days here..

That BR Ambedkar was a bright student is known, but what did American and British academics say about his credentials? Archival documents released by the London School of Economics (LSE) cast new light on the iconic leader’s student days here.

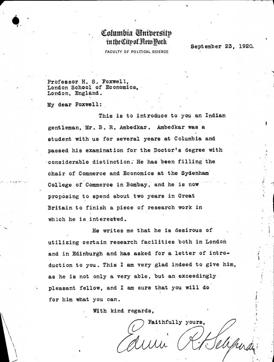

After completing a doctorate at Columbia University, Ambedkar wanted to research and study in Britain. His professor, Edwin R Seligman from Columbia, wrote to economist Herbert Foxwell at LSE on September 23, 1920, recommending his star student.

“He writes me that he is desirous of utilising certain research facilities in both London and in Edinburgh and has asked for a letter of introduction to you. This I am very glad to give him, as he is not only a very able, but an exceedingly pleasant fellow, and I am sure that you will do for him what you can,” Seligman wrote.

Foxwell wrote to LSE’s secretary, Mair, in November 1920, “I find he (Ambedkar) has already taken his doctor’s degree & has only come here to finish a research. I had forgotten this. I am sorry we cannot identify him with the School but there are no more worlds here for him to conquer.”

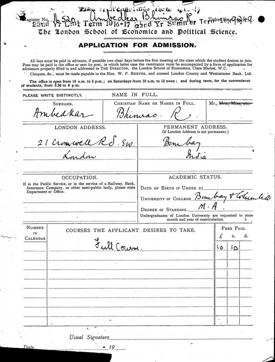

This was Ambedkar’s second attempt to study at LSE after having enrolled for a Masters degree in 1916, when he took courses in geography with Halford Mackinder, political ideas with G Lowes Dickinson, and social evolution and social theory with LT Hobhouse.

The fee for the course was £10 and 10 shillings. At the same time, Ambedkar enrolled for the bar course at Gray’s Inn. His 1916 application form in his handwriting has also been released by LSE, which mentions his permanent address as ‘Bombay, India’.

Ambedkar’s studies at LSE were interrupted as he was recalled to India to serve as a military secretary in Baroda, but in July 1917 the University of London gave him leave of absence of up to four years.

In 1920, Ambedkar returned to LSE after working as a professor of political economy at Sydenham College in Mumbai and giving evidence to the Scarborough Committee preparing the 1919 Government of India Act on the position and representation of “untouchable” communities.

Initially, he applied to complete his masters degree and write a thesis on ‘The Provincial Decentralisation of Imperial Finance in India’. His fees had gone up by a guinea, to £11 pounds and 11 shillings.

College archives show there was a slight glitch in his LSE career in April 1921 when he failed to send in his form for the summer examinations. The school secretary, Mair, had to write to University of London’s Academic Registrar for permission to submit the form late.

In economics, Ambedkar’s tutors included Edwin Cannan and Foxwell. Ambedkar submitted his doctoral thesis, ‘The Problem of the Rupee’, in March 1923 but it was not recommended for acceptance. There were reports the thesis was too revolutionary and anti-British for the examiners. However, there is no indication of this in Ambedkar’s student file. The thesis was resubmitted in August 1923 and accepted in November 1923.

It was published almost immediately and in the preface Ambedkar noted “my deep sense of gratitude to my teacher, Cannan “noting that Cannan’s “severe examination of my theoretical discussions has saved me from many an error”.

Cannan repaid the complement by writing the Foreword to the thesis in which he found “a stimulating freshness” even if he disagreed with some of the arguments.

Get World Cup ready with Crick-it! From live scores to match stats, catch all the action here. Explore now!

Get Current Updates on India News , Elections Result , Lok Sabha Election Results 2024 Live , Weather Today along with Latest News and Top Headlines from India and around the world.

Join Hindustan Times

Create free account and unlock exciting features like.

- Terms of use

- Privacy policy

- Weather Today

- HT Newsletters

- Subscription

- Print Ad Rates

- Code of Ethics

- Lok Sabha Election 2024 Live

- Karnataka Election Result

- MP Lok Sabha Result

- Bihar Lok Sabha Result

- Telangana Election Result

- Hyderabad Election Result

- WI vs PNG Live Score

- India vs Bangladesh Live Score

- Live Cricket Score

- T20 World Cup 2024

- India Squad

- T20 World Cup Schedule

- Cricket Teams

- Cricket Players

- ICC Rankings

- Cricket Schedule

- Points Table

- T20 World Cup Australia Squad

- Pakistan Squad

- T20 World Cup England Squad

- India T20 World Cup Squad Live

- T20 World Cup Most Wickets

- T20 World Cup New Zealand Squad

- Other Cities

- Stock Market Live Updates

- Income Tax Calculator

- Budget 2024

- Petrol Prices

- Diesel Prices

- Silver Rate

- Relationships

- Art and Culture

- Taylor Swift: A Primer

- Telugu Cinema

- Tamil Cinema

- Board Exams

- Exam Results

- Competitive Exams

- BBA Colleges

- Engineering Colleges

- Medical Colleges

- BCA Colleges

- Medical Exams

- Engineering Exams

- Horoscope 2024

- Festive Calendar 2024

- Compatibility Calculator

- The Economist Articles

- Lok Sabha States

- Lok Sabha Parties

- Lok Sabha Candidates

- Explainer Video

- On The Record

- Vikram Chandra Daily Wrap

- EPL 2023-24

- ISL 2023-24

- Asian Games 2023

- Public Health

- Economic Policy

- International Affairs

- Climate Change

- Gender Equality

- future tech

- Daily Sudoku

- Daily Crossword

- Daily Word Jumble

- HT Friday Finance

- Explore Hindustan Times

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Use

- Subscription - Terms of Use

- Latest Posts

- LSE Authors

- Choose a Book for Review

- Submit a Book for Review

- Bookshop Guides

Professor Aakash Singh Rathore

February 15th, 2021, b.r. ambedkar: the quest for justice.

0 comments | 9 shares

Estimated reading time: 10 minutes

Oxford University Press has just published a five-volume box-set entitled B.R Ambedkar: The Quest for Justice . In this post, the collection’s editor Aakash Singh Rathore discusses the origins and rationale of this massive project devoted to the life and legacy of the famous jurist and social reformer and briefly sketches its contents across the five volumes.

Dr B.R. Ambedkar is a celebrated LSE alumnus. You can find out more about his life and his time at LSE on LSE History blog .

B.R. Ambedkar: The Quest for Justice. Aakash Singh Rathore (ed.). Oxford University Press. 2021.

The Quest for Justice

Social activism in India today – from farmers’ and students’ protests to movements for caste, religious or gender equality to advocacy for the economically exploited and culturally marginalised – is much inspired by the profound and lasting legacy of B.R. Ambedkar. Known abroad primarily as the chief architect of the Indian Constitution, Ambedkar’s influence across the social, political, ideological, cultural, religious and legal spheres of the land of his birth cannot be overestimated. It appears that the rest of the world is also slowly beginning to more deeply feel or appreciate his wider impact.

Each 14 April, Dr Ambedkar’s birthday is celebrated on a large scale in India. Beyond being simply a national holiday, Ambedkar Jayanti is a day where local communities come alive with cultural activities, NGOs and other institutions ramp up various campaigns for social awareness, political parties organise massive rallies to extol the statesman and claim him as their own and all of academia is abuzz with special lectures, seminars and conferences of various scales: regional, national and international. This new multivolume collection, B.R. Ambedkar: The Quest for Justice , originated precisely during one such large-scale event, an international conference on Dr Ambedkar called ‘The Quest for Equity, Reclaiming Social Justice’, organised by the Government of Karnataka and held in Bangalore in 2017. There were more than 350 speakers from around the world presenting papers, and several thousand participants.

The conference was a forum for serious scholars, but it was also a social forum. It was launched keeping in view that the values of social, political and economic justice that Dr Ambedkar had relentlessly struggled toward throughout his life and political career, and that he had finally managed to enshrine within the democratic Constitution of the Republic of India, were under attack at numerous levels. Constitutional norms and public institutions created in order to fight against dominance and subservience were proving inadequate or being subverted; norms and policy were often merely paying lip service to Ambedkarite egalitarian considerations; and the rise of social intolerance and exclusion tended to effectively whittle down and even sabotage Ambedkar’s inclusive conception of polity and citizenship.

Ambedkar had understood social inequality and diversity to be layered and multidimensional, and that the state had to reckon with several competing centres of religious, communal and cultural allegiances. Naturally, the complexity of the social, political and economic environment in which the value of social justice must be envisaged had undergone significant changes over the last 70 years of the Indian Republic. Inspired by the clarity of Ambedkar’s vision and the unflinching nature of his commitment, new sites for social and political assertions have been re-emerging to face the new contemporary challenges, each evoking the legacy of Ambedkar, each renewing the call for justice. While working my way through the hundreds of academic papers presented at the Ambedkar International Conference and editing these five volumes of scholarship, it became clear to me that Ambedkar’s sophisticated yet practical and grounded approach to critical intellectual and policy challenges might actually inspire similar interventions elsewhere in the world, particularly in the Global South.

Thus, in the light of the conference, the box-set emerged as an invitation to scholars and perhaps even policymakers to substantially rethink current social, political and economic paradigms, driven by Dr B.R. Ambedkar’s imaginative and insightful work. Since justice was the foremost concern of Ambedkar, and since both Ambedkar and the contributing authors approached the idea of justice in a multidisciplinary way, I decided to organise the five volumes thematically around eight different spheres of justice: that is, in terms of political, social, legal, economic, gender, racial, religious and cultural justice.

These five volumes of papers collectively explore the major themes of research surrounding the rather massive oeuvre of Dr B.R. Ambedkar. They provide a summary evaluation of the state of Ambedkar studies internationally, highlight research trends both about and inspired by Ambedkar and open up lines of future enquiry.

Volume One focuses specifically on the theme of political justice. With a Foreword by Shashi Tharoor and contributions from foremost political theorists, the volume begins with a piece on the intellectual and political legacy of Ambedkar by Bhikhu Parekh. Several chapters then focus on the centrality of democracy and equality to Ambedkar’s political philosophy as a whole, and juxtapose Ambedkar’s political thought to other important thinkers of preceding or succeeding generations, including Antonio Gramsci, John Dewey, M.K. Gandhi and John Rawls.

Volume Two focuses on social justice. With contributions from foremost sociologists, social theorists, social and political philosophers and social activists, the volume begins with a piece on Ambedkar’s theory of the social by Martin Fuchs. This is followed up by an exploration of the centrality of Ambedkar’s social vision to his thought and work as a whole. Several contributors focus on social justice at the local or state level. Others focus at the transnational level: for example, Meena Dhanda on the UK and David Gellner on Nepal. Suraj Yengde then supplements these contributions through an analysis of Ambedkar’s internationalisation of social justice.

Volume Three covers the two themes of legal justice and economic justice. The first part explores literature on the Constitution of India and its institutions, the idea of constitutional morality, rights and the rule of law as well as Ambedkarite jurisprudence. With contributions from leading jurists, the volume begins with a piece on the ‘insurgent’ legal theory of Ambedkar by Upendra Baxi. The second part turns to a variety of issues in economic justice anchored in Ambedkar’s own economic methodology and philosophy.

Volume Four treats of gender justice and of racial justice. The first part explores Ambedkar’s impact on efforts to achieve gender justice in India, and effects various readings of Ambedkar as a feminist. The second part turns to comparisons of race and caste, and explores the ways in which the movements for racial justice and caste equality can learn from one another and seek strategies of synergy. With contributions from feminist theorists and critical race theorists, the volume covers caste, class and gender intersectionality, stigma and humiliation and issues of gender justice both at the theoretical level as well as specific empirical case studies. Other chapters offer comparisons of Ambedkar with American stalwarts of racial justice such as W.E.B. Du Bois and Martin Luther King, and applications of Ambedkarite praxis to diverse landscapes such as post-Apartheid South Africa as well as the United States.

Volume Five covers religious justice and cultural justice. The first part addresses conversion, Navayana Buddhism and liberation theology. The second part explores timely issues in cultural justice inspired by Ambedkar’s own activism and struggles. With contributions from across a wide spectrum of disciplines in the humanities and social sciences, the volume begins with a piece by Laurence Simon on Ambedkar’s prophetic role in liberating an oppressed people through religious leadership. In the second part, issues of cultural justice are presented with a focus on dignity, myth, cultural rights and academic space.

Despite the wide range of themes spread across these five volumes, the collection as a whole is oriented toward articulable specific aims and objectives. These are inspired by and fully consistent with the life and legacy of Dr Ambedkar, a man who was, on the one hand, a scholar of indubitable genius, and on the other hand, a dynamic agent of social and political action.

Firstly, B.R. Ambedkar: The Quest for Justice seeks to explore the multifaceted idea of justice in dialogue with Ambedkar’s opus for a society that encompasses manifold social inequalities, deep diversities, exclusion and marginality. Secondly, in dialogue with Ambedkar’s writings, the contributions to the collection overall aim to suggest constitutional, institutional and policy responses to the concerns of justice, and to reformulate the conceptual and policy linkages between social justice and other related norms and concerns. Thirdly, through high-level scholarship, this collection aims to help identify modes of thought and agency and social and political practices inimical to the pursuit of justice. It seeks to delineate social and political agency and modes of action conducive to the furtherance of justice in line with Dr Ambedkar’s own writings and mission.

Thus, in sum, Dr Ambedkar’s conception of justice and his life’s work shaping the idea of India offer this collection vantage points for sustained reflection on concerns of justice and its relation to other human values. This is particularly relevant, indeed urgent, in our present day, not only in India but also throughout the world.

Note: This review gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics. The LSE RB blog may receive a small commission if you choose to make a purchase through the above Amazon affiliate link. This is entirely independent of the coverage of the book on LSE Review of Books.

Image Credit: Central statue of Dr Ambedkar in Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar Marathwada University, India ( JAIBHIM5 CC BY SA 3.0 ).

About the author

Aakash Singh Rathore is author of Ambedkar's Preamble: A Secret History of the Constitution of India (Penguin, 2020) and the forthcoming B.R. Ambedkar: A Biography (Harper Collins, 2022). Rathore has taught at Jawaharlal Nehru University and the University of Delhi (both in Delhi, India), at Rutgers University and the University of Pennsylvania (both in the USA), as well as at the University of Toronto, Humboldt University in Berlin and LUISS University in Rome.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Related posts.

Book Review: Dalit Studies edited by Ramnarayan S. Rawat and K. Satyanarayana

October 28th, 2016.

Book Review: Emergency Chronicles: Indira Gandhi and Democracy’s Turning Point by Gyan Prakash

October 3rd, 2019.

Book Review: Justice and Reconciliation in World Politics by Catherine Lu

March 6th, 2019.

Book Review: The Constitution of India: A Contextual Analysis by Arun K. Thiruvengadam

March 20th, 2019, subscribe via email.

Enter your email address to subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.

Email Address

Browser does not support script.

- Using the Library

- What's on

- Collection highlights

- Research support

The life and thought of Dr B R Ambedkar in London

Hosted by lse library, the department of anthropology, and international inequalities institute.

Sheikh Zayed Theatre, Cheng Kin Ku Building, United Kingdom

Santosh Dass MBE

Former civil servant. human rights and equality campaigner, sue donnelly, retired lse archivist, professor william gould, professor of indian history at the university of leeds, professor christophe jaffrelot, avantha chair and professor of indian politics and sociology at the king's india institute, professor tarun khaitan, professor (chair) of public law at the lse law school.

Join us for a talk with the editors and authors of the recently published book, Ambedkar in London .

Dr Bhimrao R. Ambedkar (1891-1956) was one of India’s greatest intellectuals and social reformers; his political ideas continue to inspire and mobilise some of the world’s poorest and most socially disadvantaged, in India and the global Indian diaspora. Ambedkar’s thought on labour, legal rights, women’s rights, education, caste, political representation and the economy are international in importance.

This book explores his lesser-known period of London-based study and publication during the early 1920s, presenting that experience as a lens for thinking about Ambedkar’s global intellectual significance. Some of his later canon on caste, and Dalit rights and representation, was rooted in and shaped by his earlier work around the economy, governance, labour and representation during his time as a law student and as a doctoral candidate at the London School of Economics.

There will also be a chance to view the bust of Ambedkar, gifted to LSE by the Federation of Ambedkarite and Buddhist Organisations UK, and items from LSE Library archives, including Ambedkar’s student file.

Purchase the book ahead of the event .

Speakers and Chair

Santosh Dass is a former civil servant, is a human rights and equality campaigner, fighting for caste-based discrimination to be outlawed in the UK. She is Chair of the Anti Caste Discrimination Alliance, and President of the Federation of Ambedkarite and Buddhist Organisations UK.

Sue Donnelly: Prior to her retirement in 2020 Sue Donnelly worked at the LSE with responsibility for the development of LSE’s institutional archive and raising awareness of the School’s unique and fascinating history. Sue studied history at Durham University and trained as an archivist at Aberystwyth University. She began her archive career at the University of Southampton and from 1998-2013 was Head of Archives and Special Collections at LSE.

Professor William Gould is Professor of Indian History at the University of Leeds, where he teaches and publishes on the history and politics of South Asia.

Christophe Jaffrelot is Avantha Chair and Professor of Indian Politics and Sociology at the King’s India Institute, and Research Lead for the Global Institutes, King’s College London. He teaches at Sciences Po CERI, where he was director between 2000 and 2008.

Tarun Khaitan is the Professor (Chair) of Public Law at the LSE Law School and an Honorary Professorial Fellow at Melbourne Law School. Previously, he has been the Head of Research at the Bonavero Institute of Human Rights (Oxford), the Professor of Public Law and Legal Theory (Oxford), Vice Dean (Faculty of Law, Oxford), and a Visiting Professor of Law (Chicago, Harvard, and NYU law schools).

The International Inequalities Institute at LSE brings together experts from many of the School's departments and centres to lead cutting-edge research focused on understanding why inequalities are escalating in numerous arenas across the world, and to develop critical tools to address these challenges @LSEInequalities

The British Library of Political and Economic Science ( @LSELibrary ) was founded in 1896, a year after the London School of Economics and Political Science. It has been based in the Lionel Robbins Building since 1978 and houses many world class collections, including the Women's Library and Hall-Carpenter Archives.

The Department of Anthropology ( @LSEAnthropology ) is world famous and world leading. Our work is based on ethnographic research: detailed studies of societies and communities in which we have immersed ourselves via long term fieldwork. Placing the everyday lives and meanings of ordinary people - whoever and wherever they are - at the heart of the discipline, we take nothing for granted.

Accessibility

Twitter and facebook.

From time to time there are changes to event details so we strongly recommend checking back on this listing on the day of the event if you plan to attend.

Whilst we are hosting this listing, LSE Events does not take responsibility for the running and administration of this event. While we take responsible measures to ensure accurate information is given here this event is ultimately the responsibility of the organisation presenting the event.

Explore LSE Library collections

Sign up for news about events

Advertisement

More from the Review

Subscribe to our Newsletter

Best of The New York Review, plus books, events, and other items of interest

June 20, 2024

Current Issue

A ‘Life of Contradictions’

June 20, 2024 issue

LIFE/Shutterstock

B.R. Ambedkar, Delhi, India, May 1946; photograph by Margaret Bourke-White

Submit a letter:

Email us [email protected]

A Part Apart: The Life and Thought of B.R. Ambedkar

B.R. Ambedkar: The Man Who Gave Hope to India’s Dispossessed

The Evolution of Pragmatism in India: Ambedkar, Dewey, and the Rhetoric of Reconstruction

On January 17, 2016, Rohith Vemula took his own life. A twenty-six-year-old Ph.D. student at the University of Hyderabad, he was a Dalit (the caste formerly called “untouchables”) and a member of the Ambedkar Students’ Association, which combats caste discrimination. The university had suspended his stipend following a complaint by the leader of the student wing of India’s ruling Bharatiya Janata Party ( BJP ) that Rohith had physically assaulted him. The suspension made him despondent and unable to make ends meet, leading to his death. Rohith left a poignant suicide note in which he wrote of his dashed hopes of becoming a science writer like Carl Sagan. But he also called his birth a fatal accident, a reminder that the caste system had determined his status as a Dalit for life.

The word “caste” ( jati in Hindi) is derived from casta , used by the Portuguese centuries ago to describe the divisions in Hindu society according to varna (literally translated as “color” but meaning “quality” or “value”). Ancient Sanskrit texts prescribed a four-varna social order: Brahmins (priests) at the top, followed by Kshatriyas (warriors), Vaishyas (merchants and artisans), and Sudras (agricultural classes) in descending order of ritual purity. Hindu society actually consists of thousands of castes, each with its place in this hierarchy. There is also a fifth group, which is viewed as so impure as to be outside the varna order. These are the “untouchable” castes—Dalits, as we call them now. They perform jobs, such as manual scavenging and the disposal of dead animals, considered so unclean that the very sight of them is deemed polluting. 1

This ordering system is hereditary. Hindus are born into a caste and remain in it until death. Some castes belonging to the varna order have historically achieved mobility and moved to a higher varna by adopting “Sanskritizing” practices, like vegetarianism. But even this limited mobility is closed to “untouchable” castes, which remain stigmatized for generation after generation and find the doors of economic and social mobility shut tight.

Rohith’s suicide note sparked debates across India. How was such social inequality still practiced in the world’s largest democracy seventy years after independence from British rule? Attention turned to B.R. Ambedkar, not just because Rohith belonged to an organization bearing his name but also because Ambedkar, who died in 1956, has been increasingly recognized for his writings about caste as an entrenched instrument of social, economic, and religious domination in India. As he famously said in 1948, “Democracy in India is only a top-dressing on an Indian soil, which is essentially undemocratic.”

Now popularly addressed with the honorific Babasaheb, Ambedkar has long been known as a political leader of Dalits. He popularized the use of “Dalit”—meaning broken or scattered, first used in the nineteenth century by an anticaste reformer—as a term of dignity for “untouchables.” He is lauded as the chief draftsperson of the Indian constitution, which legally abolished untouchability. But few recognized him as a major thinker on the relationship between social and political democracy. This changed with the 1990s anticaste movement and the introduction of reserved slots for “backward castes”—the intermediate castes belonging to the Sudra varna—in public service jobs and universities. Political activists and academics turned to Ambedkar’s work to explain everyday discrimination against the lower castes, such as their relegation to menial jobs, humiliation in workplaces and housing, denial of entry into temples, separate wells in villages, and segregation from upper- and intermediate-caste neighborhoods. 2 His rediscovery as a political philosopher led to the publication in 2014 of a new edition of his book Annihilation of Caste (1936), with an introduction by Arundhati Roy. It dwelled on his clash with Mahatma Gandhi, who opposed his argument that caste was the social bedrock of Hinduism.

Caste remains a contentious subject, and scholars disagree on the institution’s nature and history. British colonialists interpreted it as evidence of Indian society’s basis in religion and its lack of a proper political sphere, which was filled by the colonial state. Marx adopted this view, writing that the subcontinent knew no real history until its conquest by Britain, only a succession of wars and emperors ruling over an unchanging and unresisting society. Colonial writing and practice drew on Brahminical texts to understand and rule India as a society organized by its predominant Hindu religion.

The French anthropologist Louis Dumont’s Homo Hierarchicus (1966) gave this understanding the imprimatur of scholarship by arguing that Homo hierarchicus , rather than the Western Homo aequalis , undergirded Indian society. Following Dumont, anthropologists studied castes and their hierarchical ordering according to the Brahminical principles of purity and pollution. It was not until 2001 that Nicholas Dirks persuasively argued that the British were crucial in institutionalizing caste as the essence of Indian society—though they did not invent it, they shaped caste as we know it today. 3 In place of a range of precolonial social orders based on a variety of factors, including political and economic power, society across India became defined by castes, with Brahmins at the top and Dalits at the bottom. 4

As a system of inequality, caste has met with criticism and protests for centuries. Today activists demanding the dismantling of caste privileges in employment, education, housing, economic mobility, and social respect come up against the Hindu nationalist BJP government led by Narendra Modi, which advocates ignoring caste difference in the interest of Hindu unity. The BJP is the political arm of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh ( RSS ), a paramilitary Hindu cultural organization that since its founding in 1925 has campaigned for an organicist Hindu unity, expressing admiration for the national unity model advanced by fascism and Nazism. 5 The RSS calls for reforming the most extreme aspects of caste, such as the practice of untouchability, but like most reformers, including Gandhi, does not challenge the four-varna order, regarding it as a divine organization of society in accordance with Hindu ideals. For the RSS , focusing on the differences in caste access to wealth and social status fractures the unity of Hindus; it instead calls upon castes to unite for a nation-state that guarantees Hindu supremacy. Accordingly the Modi government has systematically persecuted minority and Dalit activists as antinational elements. Hindu nationalist mobs have also assaulted and lynched Muslims, Christians, and Dalits.

Against this background of threats to democracy, Ambedkar acquires a new significance. The Indian politician Shashi Tharoor’s lucid biography is addressed to a general audience. But to appreciate the depth, complexity, nuances, and changes in the Dalit leader’s thought and politics, one should read A Part Apart by the journalist Ashok Gopal. He has pored over Ambedkar’s writings and speeches in English and Marathi, and the result is a stunning, comprehensive, and thoughtful account of Ambedkar and his times. The title is drawn from a comment Ambedkar made in 1939: “I am not a part of the whole, I am a part apart.”

What emerges in A Part Apart is a portrait of a minoritarian intellectual committed to building a society based on the principles of liberty, equality, and fraternity. This entailed resolving the gap between the political principles set forth in the Indian constitution drafted and introduced in 1950 under his leadership, and the reality of social inequality. In an often-quoted speech before the Constituent Assembly on November 25, 1949, he said:

On the 26th of January 1950, we are going to enter into a life of contradictions. In politics we will have equality and in social and economic life we will have inequality. In politics we will be recognizing the principle of one man one vote and one vote one value. In our social and economic life, we shall, by reason of our social and economic structure, continue to deny the principle of one man one value. How long shall we continue to live this life of contradictions?

Gopal’s account meticulously charts Ambedkar’s attempts to grapple with this “life of contradictions.” First, he confronted anticolonial nationalism and clashed with Gandhi on whether caste inequality was intrinsically connected to Hinduism. Second, he engaged with constitutional democracy and developed his view of politics as an instrument of social change. Third, his concern with establishing the equality of all human beings is observable in his approach to religion and his eventual turn to Buddhism.

Ambedkar was born in 1891 in the British colonial cantonment town of Mhow, now in Madhya Pradesh in central India. He was the fourteenth and last child of a family belonging to the Dalit Mahar caste. The Mahars were not allowed to draw water from public wells; upper-caste Hindus considered even their shadow polluting. The British colonial army in which his father had served recognized military rank but not the practice of untouchability. This perhaps explains why Ambedkar did not have an entirely negative view of British rule. For him self-rule was not intrinsically better than foreign rule; what mattered more than freedom from colonial domination was freedom from upper-caste domination.

The colonial army offered a modern education to soldiers, even training and recruiting them as teachers. Ambedkar recalled that his father developed a zeal for education, ensuring that all his children learned to read and write. In 1904 the family moved to a two-room tenement in a working-class Mumbai neighborhood where Ambedkar continued his education. He graduated from Bombay University in 1912 and left the next year for Columbia University, supported by a scholarship from the ruler of the princely state of Baroda.

At Columbia, he studied economics, sociology, history, philosophy, and anthropology. In 1915 he wrote a thesis for his MA in economics. While still working on his Columbia doctoral dissertation, he enrolled at the London School of Economics in 1916 for another MA in preparation for a second doctoral degree. He also enrolled in Gray’s Inn to become a barrister. He left for Mumbai a year later when his scholarship ran out, returning to London in 1920 to obtain an MS c (in economics) in 1921. He was called to the bar in 1922. A year later he submitted his dissertation and received a doctoral degree from the LSE . In 1927 he obtained his second doctorate in economics from Columbia.

By any standard, Ambedkar’s education was extraordinary, and even more so because of his stringent financial circumstances. In the years between his return to India and his Columbia doctorate, he started journals that launched his career as a public figure while teaching at a Mumbai college to support his family. In Gopal’s book he emerges as an intellectual intent on transforming Indian public discourse. This commitment came out of experiencing caste bigotry while growing up, such as being told to sit at the back of classrooms and being denied access to the water faucet unless a school employee opened it for him. Even his considerable academic achievements did not exempt him later from several humiliations, including being denied accommodations. In this respect, his time in the US and the UK provided a welcome relief.

New York also introduced Ambedkar to pragmatism, the philosophy of his teacher at Columbia, John Dewey. Several scholars have noted Dewey’s influence on his ideas on democracy and equality, 6 as did Ambedkar himself. (He was hoping to meet with his former teacher in 1952 when Columbia invited him to New York to accept an honorary degree, but Dewey died two days before his arrival.) The philosopher Scott R. Stroud’s The Evolution of Pragmatism in India is a magnificent study of Ambedkar’s complex engagement with Dewey’s ideas, which he reworked to address India’s specific political and social conditions. Stroud calls this creative use of Dewey’s philosophy Navayana pragmatism, named after Ambedkar’s Navayana, or “new vehicle” Buddhism.

Pragmatism’s impact on Ambedkar is evident in his 1919 memorandum to the Southborough Committee, appointed by the British government to consider the implementation of constitutional reforms. Ambedkar rejected the claim that Indians formed a community, which was the basis of the nationalist demand for political reforms. He cited a passage from Dewey’s Democracy and Education that the existence of a community required its members to be like-minded, with aims, aspirations, and beliefs in common. But while Dewey suggested that like-mindedness was fostered by communication, Ambedkar argued that in India it came from belonging to a single social group. And India had a multitude of these groups—castes—isolated from one another. With no communication or intermingling, Hindus formed a community only in relation to non-Hindus. Among themselves, caste-mindedness was more important than like-mindedness. Divided between “touchables” and “untouchables,” they could become one community only if they were thrown together into “associated living,” a concept from Dewey.

Above all, Ambedkar’s memorandum demanded an end to caste inequality. In 1924 he established an organization to represent and advocate for all Dalit castes with the slogan “Educate, Agitate and Organise,” which he drew from British socialists. This advocacy took on a sharper tone by 1927, when his organization arranged two conferences that catalyzed what came to be known as the Ambedkari chalval (Ambedkarite movement). The actions it took included Ambedkar and other Dalits drinking water from a public tank and symbolically burning the Manusmriti (the Hindu scripture authorizing caste hierarchy). The reaction of upper-caste Hindus was ferocious. Dalits were assaulted, and rituals to “purify” the “defiled” spaces were performed.

Ambedkar compared the second of these conferences to the French National Assembly in 1789 and their symbolic actions to the fall of the Bastille. For him the deliberate violation of caste taboos was an assertion of civil rights. He still spoke of Dalits as belonging to Hindu society but warned that if savarnas (castes belonging to the four varna s ) opposed change, Dalits would become non-Hindus. What angered him the most was the purification ceremonies, which he saw as an attack on the humanity and sanctity of the Dalit physical body.

Ambedkar’s demand for social justice put him at odds with the nationalist movement and eventually with Gandhi. In a 1920 editorial he acknowledged that Indians were denied self-development under the British Raj, but that the same could be said of Dalits under the “Brahmin raj.” He wrote that they had every right to ask, “What have you done to throw open the path of self-development for six crore [60 million] Untouchables in the country?” He described the Gandhi-led Indian National Congress as “political radicals and social Tories” whose “delicate gentility will neither bear the Englishman as superior nor will it brook the Untouchables as equal.”

Clearly the disagreements were deep. Gandhi, like other nationalists, believed that freedom from British rule was the primary goal and that Hindu society could address untouchability after independence had been achieved. Ambedkar, drawing on Dewey’s ideas on associated life, argued that India was not yet a nation and could not become one without addressing caste injustice. The purpose of politics, in his view, was to enact social change that Hindu society was too caste-ridden to accomplish on its own.

The conflict between the two men came to a head at the Round Table Conferences ( RTC ) in London, organized by the British to discuss political devolution. Several Congress Party leaders had denounced Ambedkar as a government puppet when he was appointed in 1927 as a nonelected representative of Dalits (whom the British called Depressed Classes) in the Bombay Legislative Council. Their criticism escalated at the second RTC when Ambedkar demanded that Dalits be granted separate constituencies to elect their own representatives to provincial legislatures. The Congress saw this as falling for the classic colonial ploy of divide and rule. It was willing to concede separate electorates for Muslims but not for Dalits. Gandhi was especially opposed to Ambedkar’s stand because he saw the Dalits, unlike Muslims, as part of Hindu society. He went on a fast to oppose the 1932 Communal Award, an electoral scheme announced by the British government that accepted separate representation for both Muslims and Dalits.

The standoff was resolved only after Ambedkar, Gandhi, and upper-caste leaders signed the Poona Pact that September. Ambedkar dropped his demand for separate electorates and accepted the principle of reserved seats for Dalits elected by joint electorates. From later writings by Ambedkar, in particular Annihilation of Caste and What Congress and Gandhi Have Done to the Untouchables (1945), the Poona Pact appears to have been a breaking point between the two men, a view that historians have accepted. But Gopal shows that the picture was more complicated in 1932.

Gandhi saw himself as a champion of Dalits, whom he called Harijans (“children of God”). He was loath to concede that they were outside Hinduism, like Muslims, and required separate representation. He wanted savarnas to abandon the practice of untouchability by a change of heart. Though Ambedkar appreciated Gandhi’s efforts, he wanted separate electorates because joint electorates for reserved seats meant that only those candidates acceptable to savarnas would win. But he signed the Poona Pact and accepted the outcome, even if it amounted to a concession.