- Our Ministry

- The Gap We See

- Partner with Us

- Newsletters

- Partner With Us

Christian History

Time Periods

- Early Church • 1 - 500 AD

- Middle Ages • 500 - 1500 AD

- Reformation • 1500 - 1650 AD

- Early Modern • 1500 - 1800 AD

- Modern • 1800 - Present

- Full Timeline

- Story Behind

- Denominations & Traditions

- Literature & the Arts

- Missions & World Christianity

- Preachers & Evangelists

- The American Experience

- Theologians

- 100 Events in Church History

Key Figures by Category

- Today in Christian History

- Subscribe to CT magazine for full access to the Christian History Archives

- Give a Gift

Featured Holidays

- All Holidays

Featured People

- Denominational Founders

- Pastors and Preachers

- All Categories

1517 Luther Posts the 95 Theses

- Early Church

- Middle Ages

- Reformation

- Early Modern

- Current Issue

- How to Pray with ADHD

- The Struggle to Hold It Together When a Church Falls Apart

- The Secret Sin of ‘Mommy Juice’

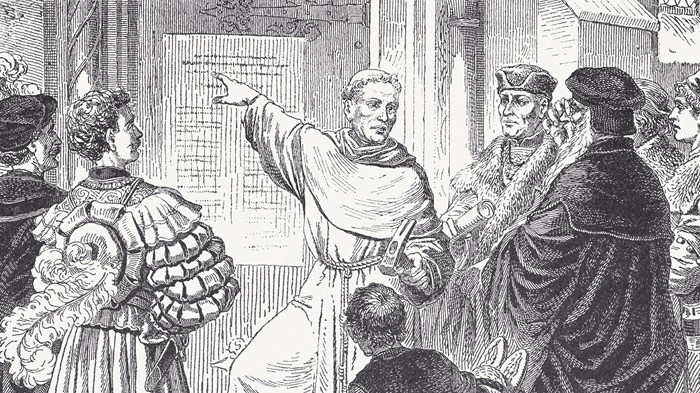

S ometime during October 31, 1517, the day before the Feast of All Saints, the 33-year-old Martin Luther posted theses on the door of the Castle Church in Wittenberg. The door functioned as a bulletin board for various announcements related to academic and church affairs. The theses were written in Latin and printed on a folio sheet by the printer John Gruenenberg, one of the many entrepreneurs in the new print medium first used in Germany about 1450. Luther was calling for a "disputation on the power and efficacy of indulgences out of love and zeal for truth and the desire to bring it to light." He did so as a faithful monk and priest who had been appointed professor of biblical theology at the University of Wittenberg, a small, virtually unknown institution in a small town.

Some copies of the theses were sent to friends and church officials, but the disputation never took place. Albert of Brandenburg, archbishop of Mainz, sent the theses to some theologians whose judgment moved him to send a copy to Rome and demand action against Luther. By the early months of 1518, the theses had been reprinted in many cities, and Luther's name had become associated with demands for radical change in the church. He had become front-page news.

The Issue of Indulgences

Why? Luther was calling for a debate on the most neuralgic issue of his time: the relationship between money and religion. "Indulgences" (from the Latin indulgentia —permit) had become the complex instruments for granting forgiveness of sins. The granting of forgiveness in the sacrament of penance was based on the "power of the keys" given to the apostles according to Matthew 16:18, and was used to discipline sinners. Penitent sinners were asked to show regret for their sins (contrition), confess them to a priest (confession), and do penitential work to atone for them (satisfaction).

Indulgences were issued by executive papal order and by written permission in various bishoprics, and they were meant to relax or commute the penitent sinner's work of satisfaction. By the late eleventh century it had become customary to issue indulgences to volunteers taking part in crusades to the Holy Land against the Muslims; all sins would be forgiven anyone participating in such a dangerous but holy enterprise. After 1300 a complete commutation of satisfaction ("plenary indulgence") was granted to all pilgrims visiting holy shrines in Rome during "jubilee years" (at first every hundred years, and, eventually, every twenty-five years).

Abuses soon abounded: "permits" were issued offering release from all temporal punishment—indeed, from punishment in purgatory—for a specific payment as determined by the church. Some popes pursued their "edifice complex" by collecting large sums through the sale of indulgences. Pope Julius II, for example, granted a "jubilee indulgence" in 1510, the proceeds of which were used to build the new basilica of St. Peter in Rome.

In 1515, Pope Leo X commissioned Albert of Brandenburg to use the Dominican order to sell St. Peter indulgences in his lands. Albert owed a large sum to Rome for having granted him a special dispensation to become the ecclesiastical prince ruling three territories (Mainz, Magdeburg, and Halberstadt). He borrowed the money from the Fugger bank in Augsburg, which engaged an experienced indulgences salesman, the Dominican John Tetzel, to run the indulgences traffic; one half of the proceeds went to Albert and the Fuggers, the other half to Rome. Tetzel's campaign gave rise to the famous jingle, "As soon as the coin in the coffer rings, a soul from purgatory springs."

The issue of indulgences had now become linked to the prevalent anxiety regarding death and the final judgment. This anxiety was fueled by a runaway credit system based on printed money and the new banking system.

The Message of Martin Luther

Luther attacked the abuse of indulgence sales in sermons, in counseling sessions, and, finally, in the Ninety-Five Theses, which rang out the revolutionary theme of the Reformation: "When our Lord and Master Jesus Christ said, 'Repent,' He willed the entire life of believers to be one of repentance" (Thesis 1).

By 1520, Luther announced that baptism is the only indulgence necessary for salvation. All of life is a "return to baptism" in the sense that one clings to the divine promise of salvation through faith in Jesus Christ alone, who by his life, death, and resurrection liberated humankind from all punishment for sin. One lives by trusting in Christ alone and thus becoming a Christ to the neighbor in need rather than by trying to pacify God.

It is this simple reaffirmation of the ancient Christian "good news," the gospel, that created in the church catholic the reform movement that attracted legions in Germany and other European territories. The movement was propelled by slogans stressing the essentials of Christianity: faith alone ( soia fides ), grace alone ( sola gratia ), Christ alone ( solus Christus ). Many joined because Luther criticized the papacy, which had claimed to have power over every soul. "Why does not the pope whose wealth today is greater than the wealth of the richest Crassus (a wealthy Roman nicknamed "Fats," who died in 53 B.C.) build this one basilica of St. Peter with his own money rather than with the money of poor believers?" (Thesis 87).

The Ninety-Five Theses were the straw that broke the Catholic camel's back. When Luther was asked later why he had done what he did, he answered, "I never wanted to do it, but was forced into it when I had to become a Doctor of Holy Scripture against my will." Though condemned by church and state, Luther survived the attempts to burn him as a heretic.

Hindsight suggests that Luther's theses planted the seeds of an ecumenical dialogue on what is essential for Christian unity, indeed for survival, in the interim between Christ's first and second coming. That dialogue will bear fruit as long as it wrestles, as Luther did, with the proper distinction between the power of the Word of God and the power of human sin.

Dr. Eric W. Gritsch is Maryland Synod Professor of Church History and director of the Institute for Luther Studies at Gettysburg Lutheran Seminary, Gettysburg, Pennsylvania.

Copyright © 1990 by the author or Christianity Today/Christian History magazine. Click here for reprint information on Christian History.

Support Our Work

Subscribe to CT for less than $4.25/month

Read These Next

The Magazine

- Issue Archives

- Member Benefits

Special Sections

- News & Reporting

- Español | All Languages

Topics & People

- Theology & Spirituality

- Church Life & Ministry

- Politics & Current Affairs

- Higher Education

- Global Church

- All Topics & People

Help & Info

- Contact Us | FAQ

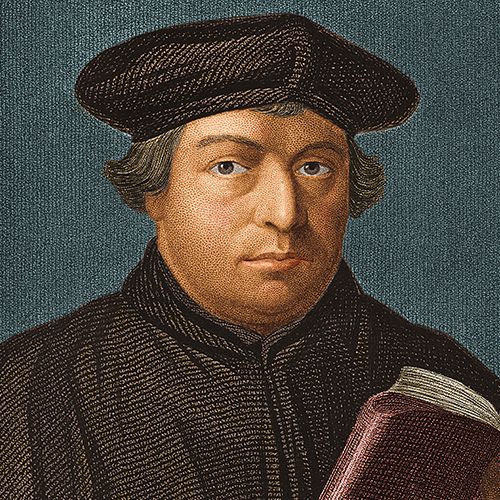

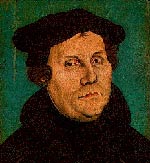

Martin Luther

(1483-1546)

Who Was Martin Luther?

Luther called into question some of the basic tenets of Roman Catholicism, and his followers soon split from the Roman Catholic Church to begin the Protestant tradition. His actions set in motion tremendous reform within the Church.

A prominent theologian, Luther’s desire for people to feel closer to God led him to translate the Bible into the language of the people, radically changing the relationship between church leaders and their followers.

Luther was born on November 10, 1483, in Eisleben, Saxony, located in modern-day Germany.

His parents, Hans and Margarette Luther, were of peasant lineage. However, Hans had some success as a miner and ore smelter, and in 1484 the family moved from Eisleben to nearby Mansfeld, where Hans held ore deposits.

Hans Luther knew that mining was a tough business and wanted his promising son to have a better career as a lawyer. At age seven, Luther entered school in Mansfeld.

At 14, Luther went north to Magdeburg, where he continued his studies. In 1498, he returned to Eisleben and enrolled in a school, studying grammar, rhetoric and logic. He later compared this experience to purgatory and hell.

In 1501, Luther entered the University of Erfurt , where he received a degree in grammar, logic, rhetoric and metaphysics. At this time, it seemed he was on his way to becoming a lawyer.

Becoming a Monk

In July 1505, Luther had a life-changing experience that set him on a new course to becoming a monk.

Caught in a horrific thunderstorm where he feared for his life, Luther cried out to St. Anne, the patron saint of miners, “Save me, St. Anne, and I’ll become a monk!” The storm subsided and he was saved.

Most historians believe this was not a spontaneous act, but an idea already formulated in Luther’s mind. The decision to become a monk was difficult and greatly disappointed his father, but he felt he must keep a promise.

Luther was also driven by fears of hell and God’s wrath, and felt that life in a monastery would help him find salvation.

The first few years of monastic life were difficult for Luther, as he did not find the religious enlightenment he was seeking. A mentor told him to focus his life exclusively on Jesus Christ and this would later provide him with the guidance he sought.

Disillusionment with Rome

At age 27, Luther was given the opportunity to be a delegate to a Catholic church conference in Rome. He came away more disillusioned, and very discouraged by the immorality and corruption he witnessed there among the Catholic priests.

Upon his return to Germany, he enrolled in the University of Wittenberg in an attempt to suppress his spiritual turmoil. He excelled in his studies and received a doctorate, becoming a professor of theology at the university (known today as Martin Luther University Halle-Wittenberg ).

Through his studies of scripture, Luther finally gained religious enlightenment. Beginning in 1513, while preparing lectures, Luther read the first line of Psalm 22, which Christ wailed in his cry for mercy on the cross, a cry similar to Luther’s own disillusionment with God and religion.

Two years later, while preparing a lecture on Paul’s Epistle to the Romans, he read, “The just will live by faith.” He dwelled on this statement for some time.

Finally, he realized the key to spiritual salvation was not to fear God or be enslaved by religious dogma but to believe that faith alone would bring salvation. This period marked a major change in his life and set in motion the Reformation.

DOWNLOAD BIOGRAPHY'S MARTIN LUTHER FACT CARD

'95 Theses'

On October 31, 1517, Luther, angry with Pope Leo X’s new round of indulgences to help build St. Peter’s Basilica , nailed a sheet of paper with his 95 Theses on the University of Wittenberg’s chapel door.

Though Luther intended these to be discussion points, the 95 Theses laid out a devastating critique of the indulgences - good works, which often involved monetary donations, that popes could grant to the people to cancel out penance for sins - as corrupting people’s faith.

Luther also sent a copy to Archbishop Albert Albrecht of Mainz, calling on him to end the sale of indulgences. Aided by the printing press , copies of the 95 Theses spread throughout Germany within two weeks and throughout Europe within two months.

The Church eventually moved to stop the act of defiance. In October 1518, at a meeting with Cardinal Thomas Cajetan in Augsburg, Luther was ordered to recant his 95 Theses by the authority of the pope.

Luther said he would not recant unless scripture proved him wrong. He went further, stating he didn’t consider that the papacy had the authority to interpret scripture. The meeting ended in a shouting match and initiated his ultimate excommunication from the Church.

Excommunication

Following the publication of his 95 Theses , Luther continued to lecture and write in Wittenberg. In June and July of 1519 Luther publicly declared that the Bible did not give the pope the exclusive right to interpret scripture, which was a direct attack on the authority of the papacy.

Finally, in 1520, the pope had had enough and on June 15 issued an ultimatum threatening Luther with excommunication.

On December 10, 1520, Luther publicly burned the letter. In January 1521, Luther was officially excommunicated from the Roman Catholic Church.

Diet of Worms

In March 1521, Luther was summoned before the Diet of Worms , a general assembly of secular authorities. Again, Luther refused to recant his statements, demanding he be shown any scripture that would refute his position. There was none.

On May 8, 1521, the council released the Edict of Worms, banning Luther’s writings and declaring him a “convicted heretic.” This made him a condemned and wanted man. Friends helped him hide out at the Wartburg Castle.

While in seclusion, he translated the New Testament into the German language, to give ordinary people the opportunity to read God’s word.

Lutheran Church

Though still under threat of arrest, Luther returned to Wittenberg Castle Church, in Eisenach, in May 1522 to organize a new church, Lutheranism.

He gained many followers, and the Lutheran Church also received considerable support from German princes.

When a peasant revolt began in 1524, Luther denounced the peasants and sided with the rulers, whom he depended on to keep his church growing. Thousands of peasants were killed, but the Lutheran Church grew over the years.

Katharina von Bora

In 1525, Luther married Katharina von Bora, a former nun who had abandoned the convent and taken refuge in Wittenberg.

Born into a noble family that had fallen on hard times, at the age of five Katharina was sent to a convent. She and several other reform-minded nuns decided to escape the rigors of the cloistered life, and after smuggling out a letter pleading for help from the Lutherans, Luther organized a daring plot.

With the help of a fishmonger, Luther had the rebellious nuns hide in herring barrels that were secreted out of the convent after dark - an offense punishable by death. Luther ensured that all the women found employment or marriage prospects, except for the strong-willed Katharina, who refused all suitors except Luther himself.

The scandalous marriage of a disgraced monk to a disgraced nun may have somewhat tarnished the reform movement, but over the next several years, the couple prospered and had six children.

Katharina proved herself a more than a capable wife and ally, as she greatly increased their family's wealth by shrewdly investing in farms, orchards and a brewery. She also converted a former monastery into a dormitory and meeting center for Reformation activists.

Luther later said of his marriage, "I have made the angels laugh and the devils weep." Unusual for its time, Luther in his will entrusted Katharina as his sole inheritor and guardian of their children.

Anti-Semitism

From 1533 to his death in 1546, Luther served as the dean of theology at University of Wittenberg. During this time he suffered from many illnesses, including arthritis, heart problems and digestive disorders.

The physical pain and emotional strain of being a fugitive might have been reflected in his writings.

Some works contained strident and offensive language against several segments of society, particularly Jews and, to a lesser degree, Muslims. Luther's anti-Semitism is on full display in his treatise, The Jews and Their Lies .

Luther died following a stroke on February 18, 1546, at the age of 62 during a trip to his hometown of Eisleben. He was buried in All Saints' Church in Wittenberg, the city he had helped turn into an intellectual center.

Luther's teachings and translations radically changed Christian theology. Thanks in large part to the Gutenberg press, his influence continued to grow after his death, as his message spread across Europe and around the world.

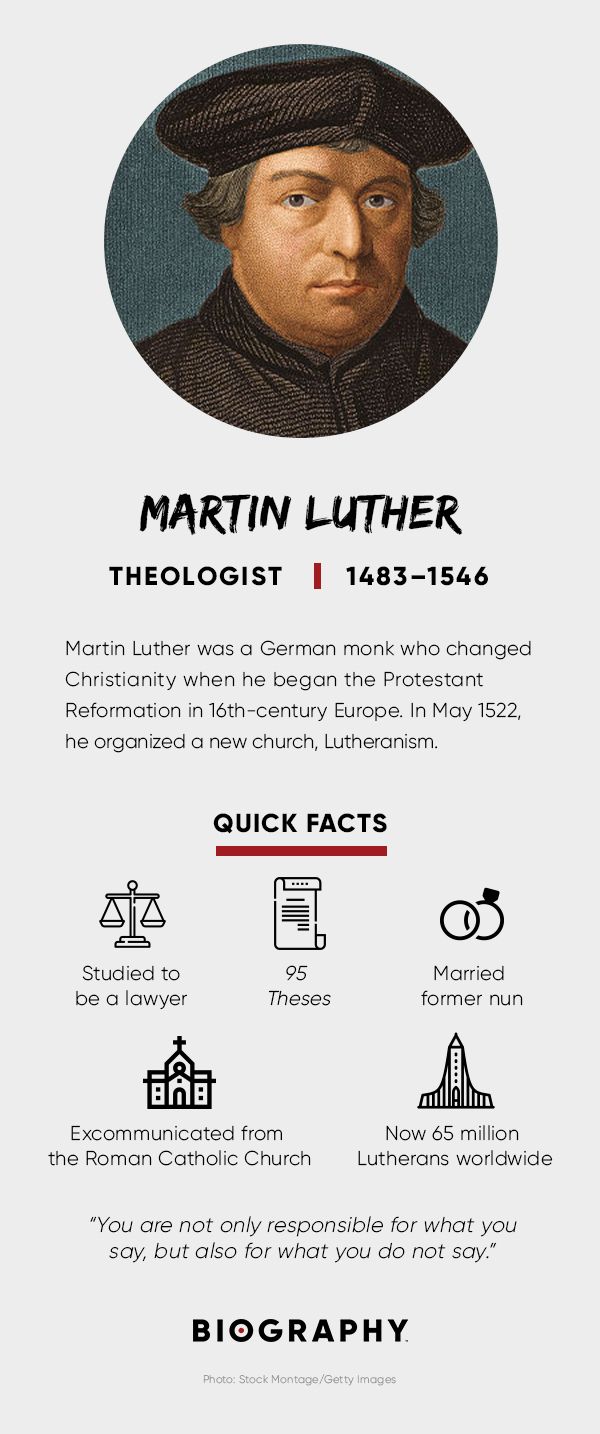

QUICK FACTS

- Name: Luther Martin

- Birth Year: 1483

- Birth date: November 10, 1483

- Birth City: Eisleben

- Birth Country: Germany

- Gender: Male

- Best Known For: Martin Luther was a German monk who forever changed Christianity when he nailed his '95 Theses' to a church door in 1517, sparking the Protestant Reformation.

- Christianity

- Astrological Sign: Scorpio

- Nacionalities

- Interesting Facts

- Martin Luther studied to be a lawyer before deciding to become a monk.

- Luther refused to recant his '95 Theses' and was excommunicated from the Catholic Church.

- Luther married a former nun and they went on to have six children.

- Death Year: 1546

- Death date: February 18, 1546

- Death City: Eisleben

- Death Country: Germany

We strive for accuracy and fairness.If you see something that doesn't look right, contact us !

CITATION INFORMATION

- Article Title: Martin Luther Biography

- Author: Biography.com Editors

- Website Name: The Biography.com website

- Url: https://www.biography.com/religious-figures/martin-luther

- Access Date:

- Publisher: A&E; Television Networks

- Last Updated: September 20, 2019

- Original Published Date: April 2, 2014

- To be a Christian without prayer is no more possible than to be alive without breathing.

- God writes the Gospel not in the Bible alone, but also on trees, and in the flowers and clouds and stars.

- Let the wife make the husband glad to come home, and let him make her sorry to see him leave.

- You are not only responsible for what you say, but also for what you do not say.

Famous Religious Figures

7 Little-Known Facts About Saint Patrick

Saint Nicholas

Jerry Falwell

Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh

Saint Thomas Aquinas

History of the Dalai Lama's Biggest Controversies

Saint Patrick

Pope Benedict XVI

John Calvin

Pontius Pilate

Check-out the new Famous Trials website at www.famous-trials.com :

The new website has a cleaner look, additional video and audio clips, revised trial accounts, and new features that should improve the navigation., redirecting to: www.famous-trials.com/luther in ( 10 ) seconds., (close this pop-up window to remain on this page).

Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy

Martin luther (1483—1546).

Given Luther’s critique of philosophy and his famous phrase that philosophy is the “devil’s whore,” it would be easy to assume that Luther had only contempt for philosophy and reason. Nothing could be further from the truth. Luther believed, rather, that philosophy and reason had important roles to play in our lives and in the life of the community. However, he also felt that it was important to remember what those roles were and not to confuse the proper use of philosophy with an improper one.

Properly understood and used, philosophy and reason are a great aid to individuals and society. Improperly used, they become a great threat to both. Likewise, revelation and the gospel when used properly are an aid to society, but when misused also have sad and profound implications.

Table of Contents

- Theological Background: William of Occam

- Theology of the Cross

- The Law and the Gospel

- Deus Absconditus – The Hidden God

- Relationship to Philosophy

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

1. Biography

Martin Luther was born to peasant stock on November 10, 1483 in Eisleben in the Holy Roman Empire – in what is today eastern Germany. Soon after Luther’s birth, his family moved from Eisleben to Mansfeld. His father was a relatively successful miner and smelter and Mansfeld was a larger mining town. Martin was the second son born to Hans and Magarete (Lindemann) Luther. Two of his brothers died during outbreaks of the plague. One other brother, James, lived to adulthood.

Luther’s father knew that mining was a cyclical occupation, and he wanted more security for his promising young son. Hans Luther decided that he would do whatever was necessary to see that Martin could become a lawyer. Hans saw to it that Martin started school in Mansfeld probably around seven. The school stressed Latin and a bit of logic and rhetoric. When Martin was 14 he was sent to Magdeburg to continue his studies. He stayed only one year in Magdeburg and then enrolled in Latin school in Eisenach until 1501. In 1501 he enrolled in the University of Erfurt where he studied the basic course for a Master of Arts (grammar, logic, rhetoric, metaphysics, etc.). Significant to his spiritual and theological development was the principal role of William of Occam’s theology and metaphysics in Erfurt’s curriculum. In 1505, it seemed that Han’s Luther’s plans were about to finally be realized. His son was on the verge of becoming a lawyer. Han’s Luther’s plans were interrupted by a thunderstorm and vow.

In July of 1505, Martin was caught in a horrific thunderstorm. Afraid that he was going to die, he screamed out a vow, “Save me, St. Anna, and I shall become a monk.” St. Anna was the mother of the Virgin Mary and the patron saint of miners. Most argue that this commitment to become a monk could not have come out of thin air and instead represents an intensification experience in which an already formulated thought is expanded and deepened. On July 17 th Luther entered the Augustinian Monastery at Erfurt.

The decision to enter the monastery was a difficult one. Martin knew that he would greatly disappoint his parents (which he did), but he also knew that one must keep a promise made to God. Beyond that, however, he also had strong internal reasons to join the monastery. Luther was haunted by insecurity about his salvation (he describes these insecurities in striking tones and calls them Anfectungen or Afflictions.) A monastery was the perfect place to find assurance.

Assurance evaded him however. He threw himself into the life of a monk with verve. It did not seem to help. Finally, his mentor told him to focus on Christ and him alone in his quest for assurance. Though his anxieties would plague him for still years to come, the seeds for his later assurance were laid in that conversation.

In 1510, Luther traveled as part of delegation from his monastery to Rome (he was not very impressed with what he saw.) In 1511, he transferred from the monastery in Erfurt to one in Wittenberg where, after receiving his doctor of theology degree, he became a professor of biblical theology at the newly founded University of Wittenberg.

In 1513, he began his first lectures on the Psalms. In these lectures, Luther’s critique of the theological world around him begins to take shape. Later, in lectures on Paul’s Epistle to the Romans (in 1515/16) this critique becomes more noticeable. It was during these lectures that Luther finally found the assurance that had evaded him for years. The discovery that changed Luther’s life ultimately changed the course of church history and the history of Europe. In Romans, Paul writes of the “righteousness of God.” Luther had always understood that term to mean that God was a righteous judge that demanded human righteousness. Now, Luther understood righteousness as a gift of God’s grace. He had discovered (or recovered) the doctrine of justification by grace alone. This discovery set him afire.

In 1517, he posted a sheet of theses for discussion on the University’s chapel door. These Ninety-Five Theses set out a devastating critique of the church’s sale of indulgences and explained the fundamentals of justification by grace alone. Luther also sent a copy of the theses to Archbishop Albrecht of Mainz calling on him to end the sale of indulgences. Albrecht was not amused. In Rome, cardinals saw Luther’s theses as an attack on papal authority. In 1518 at a meeting of the Augustinian Order in Heidelberg, Luther set out his positions with even more precision. In the Heidelberg Disputation , we see the signs of a maturing in Luther’s thought and new clarity surrounding his theological perspective – the Theology of the Cross.

After the Heidelberg meeting in October 1518, Luther was told to recant his positions by the Papal Legate, Thomas Cardinal Cajetan. Luther stated that he could not recant unless his mistakes were pointed out to him by appeals to “scripture and right reason” he would not, in fact, could not recant. Luther’s refusal to recant set in motion his ultimate excommunication.

Throughout 1519, Luther continued to lecture and write in Wittenberg. In June and July of that year, he participated in another debate on Indulgences and the papacy in Leipzig. Finally, in 1520, the pope had had enough. On June 15 th the pope issued a bull ( Exsurge Domini – Arise O’Lord) threatening Luther with excommunication. Luther received the bull on October 10 th . He publicly burned it on December 10 th .

In January 1521, the pope excommunicated Luther. In March, he was summonsed by Emperor Charles V to Worms to defend himself. During the Diet of Worms, Luther refused to recant his position. Whether he actually said, “Here I stand, I can do no other” is uncertain. What is known is that he did refuse to recant and on May 8 th was placed under Imperial Ban.

This placed Luther and his duke in a difficult position. Luther was now a condemned and wanted man. Luther hid out at the Wartburg Castle until May of 1522 when he returned to Wittenberg. He continued teaching. In 1524, Luther left the monastery. In 1525, he married Katharina von Bora.

From 1533 to his death in 1546 he served as the Dean of the theology faculty at Wittenberg. He died in Eisleben on 18 February 1546.

2. Theology

A. theological background: william of occam.

The medieval worldview was rational, ordered, and synthetic. Thomas Aquinas embodied it. It survived until the acids of war, plague, poverty, and social discord began to eat away its underlying presupposition – that the world rested on the being of God.

All of life was grounded in the mind of God. In the hierarchy of Being that establishes justice, the church was understood as the connection between the secular and divine. However, as the crises of the late middle ages increased, this reassurance no longer assuaged.

William of Occam recognized the shortcomings of Thomas’s system and cut away most of the ontological grounding of existence. In its place, Occam posited revelation and covenant. The world does not need to be grounded in some artificial, unknowable, ladder of Being. Instead, one must rely on God’s faithfulness. We are contingent upon God alone.

This contingency would be terrible and unbearable without the assurance of God’s covenant. In terms of God’s absolute power ( potentia absoluta ), God can do anything. He can make a lie the truth, he can make adultery a virtue and monogamy a vice. The only limit to this power is consistency—God cannot contradict his own essence. To live in a world ordered by whim would be terrible; one would never know if one was acting justly or unjustly. However, God has decided on a particular way of acting ( potentia ordinata ). God has covenanted with creation, and committed himself to a particular way of acting.

While rejecting some of Thomas, Occam did not reject the entire scholastic project. He, too, synthesized and depended heavily upon Aristotle. This dependence becomes significant in the covenantal piety of justification. The fundamental question of justification is where does one find fellowship with God, i.e., how does one know one is accepted by God? The logic of Aristotle taught Thomas and Occam that “like is known by like.” Thus, union or fellowship with God must take place on God’s level. How does this happen? Practice.

All people are born, it was argued, with potential. Even though all creation suffers under the condemnation of the Fall of Adam and Eve, there remains a divine spark of potentiality, a syntersis . This potential must be actualized. It must be habituated. Habituation was important for both Thomas and Occam; however, Occam slightly modifies Thomas and that modification has important implications in Luther’s search for a gracious God.

From Thomas’s perspective the divine spark is infused with God’s grace, giving one the power to be contrite ( contritio ) and co-operate with God. This co-operation with God’s grace merits God’s reward ( meritum de condign ). However, Occam asked an important question: if the process begins with God’s infusion of grace, can it truly merit anything? He answered, no! Therefore you should do the best you can. By doing your best, even as minimal as it is, this will merit ( meritum de congruo ) an infusion of grace: facienti quod in se est Deus non denegat gratiam (God will not deny his grace to anyone who does what lies within him.) Doing one’s best meant rejecting evil and doing good.

Within this context of covenant Luther struggled to prove that he was good enough to merit God’s grace. However, he failed to convince himself. He might have been contrite, but was he contrite enough? This uncertainty afflicted ( Anfectungen ) him for years.

b. Theology of the Cross

Luther’s attempts to prove his worthiness failed. He continued to be plagued by uncertainty and doubt concerning his salvation. Finally, during his Lectures on Paul’s Epistle to the Romans he found solace. Instead of storehouses of merit, indulgences, habituation, and “doing what is within one,” God accepts the sinner in spite of the sin. Acceptance is based on who one is rather than what one does. Justification is bestowed rather than achieved. Justification is not based on human righteousness, but on God’s righteousness—revealed and confirmed in Christ.

In St. Paul, Luther finally found a word of hope. He finally found a word of assurance and discovered the graciousness of God. The discovery of God’s graciousness pro me (for me) revolutionizes all aspects of Luther’s life and thought. From now on, Luther’s response to the trials of his life and the crises of the late medieval period was to be certain of God, but never to be secure in human society.

A tautology of Luther’s theology becomes: one must always “Let God be God.” This frees human beings to be human. We do not have to achieve salvation; rather, it is a gift to be received. Salvation thus is the presupposition of the life of the Christian and not its goal. This belief engendered his rejection of indulgences and his movement to a theologia crucis (Theology of the Cross).

Why were indulgences rejected? Simply put, they epitomize everything that from Luther’s perspective was wrong with the church. Instead of dependence upon God, they placed salvation in the hands of traveling salesmen hocking indulgences. They embody his rejection of all types of theology that are based in models of covenant.

The import of the Theology of the Cross was the discovery of God’s passive righteousness and theological models based in Testament. From the author of Hebrews, Luther takes an understanding of Jesus Christ as the last will and testament of God. God has written humanity in the will as heirs of God and co-heirs with Christ (See Romans 8).

The rejection of covenant model theologies and the movement to testament is a fundamental aspect of Luther’s theologia crucis . It is a rejection of any type of a theology of glory ( theologia gloriae ). The rejection of the theology of glory has a profound impact on Luther’s anthropology of a Christian.

This rejection is illustrated by Luther’s small but significant alteration of Augustinian anthropology. In that system, human beings are partim bonnum, partim malum or partim iustus, partim peccare (partly good/just, partly bad/sinner). The goal of a Christian’s life is to grow in righteousness. In other words, one must work to decrease the side of the equation that is bad and sinful. As one decreases the sin in oneself, the good and just aspects of one’s being increase.

Luther’s anthropology, however, is an outright and total rejection of progress; because no matter how one understands it, it is a work and thus must be rejected. Luther’s alternative characterization of Christian anthropology was simul iustus et peccator (at once righteous and sinful.) Now, he begins to speak of righteousness in two ways: coram deo (righteousness before God) and coram hominibus (before man). Instead of a development in righteousness based in the person, or an infusion of merit from the saints, a person is judged righteous before God because of the works of Christ. But, absent the perspective of God and the righteousness of Christ, based on one’s own merit—a Christian still looks like a sinner.

c. The Law and the Gospel

The distinction between the Law and the Gospel is a fundamental dialectic in Luther’s thought. He argues that God interacts with humanity in two fundamental ways – the law and the gospel. The law comes to humanity as the commands of God – such as the Ten Commandments. The law allows the human community to exist and survive because it limits chaos and evil and convicts us of our sinfulness. All humanity has some grasp of the law through the conscience. The law convicts us our sin and drives us to the gospel, but it is not God’s avenue for salvation.

Salvation comes to humanity through the Good News (Gospel) of Jesus Christ. The Good News is that righteousness is not a demand upon the sinner but a gift to the sinner. The sinner simply accepts the gift through faith. For Luther the folly of indulgences was that they confused the law with the gospel. By stating that humanity must do something to merit forgiveness they promulgated the notion that salvation is achieved rather than received. Much of Luther’s career focused on deconstructing the idea of the law as an avenue for salvation.

d. Deus Absconditus – The Hidden God

Another fundamental aspect of Luther’s theology is his understanding of God. In rejecting much of scholastic thought Luther rejected the scholastic belief in continuity between revelation and perception. Luther notes that revelation must be indirect and concealed. Luther’s theology is based in the Word of God (thus his phrase sola scriptura – scripture alone). It is based not in speculation or philosophical principles, but in revelation.

Because of humanity’s fallen condition, one can neither understand the redemptive word nor can one see God face to face. Here Luther’s exposition on number twenty of his Heidelberg Disputation is important. It is an allusion to Exodus 33, where Moses seeks to see the Glory of the Lord but instead sees only the backside. No one can see God face to face and live, so God reveals himself on the backside, that is to say, where it seems he should not be. For Luther this meant in the human nature of Christ, in his weakness, his suffering, and his foolishness.

Thus revelation is seen in the suffering of Christ rather than in moral activity or created order and is addressed to faith. The Deus Absconditus is actually quite simple. It is a rejection of philosophy as the starting point for theology. Why? Because if one begins with philosophical categories for God one begins with the attributes of God: i.e., omniscient, omnipresent, omnipotent, impassible, etc. For Luther, it was impossible to begin there and by using syllogisms or other logical means to end up with a God who suffers on the cross on behalf of humanity. It simply does not work. The God revealed in and through the cross is not the God of philosophy but the God of revelation. Only faith can understand and appreciate this, logic and reason – to quote St. Paul become a stumbling block to belief instead of a helpmate.

3. Relationship to Philosophy

The proper role of philosophy is organizational and as an aid in governance. When Cardinal Cajetan first demanded Luther’s recantation of the Ninety-Five Theses , Luther appealed to scripture and right reason. Reason can be an aid to faith in that it helps to clarify and organize, but it is always second-order discourse. It is, following St. Anselm, fides quarenes intellectum (faith seeking understanding) and never the reverse. Philosophy tells us that God is omnipotent and impassible; revelation tells us that Jesus Christ died for humanity’s sin. The two cannot be reconciled. Reason is the devil’s whore precisely because it asks the wrong questions and looks in the wrong direction for answers. Revelation is the only proper place for theology to begin. Reason must always take a back-seat.

Reason does play a primary role in governance and in most human interaction. Reason, Luther argued, is necessary for a good and just society. In fact, unlike most of his contemporaries, Luther did not believe that a ruler had to be Christian, only reasonable. Here, opposite to his discussion of theology, it is revelation that is improper. Trying to govern using the gospel as one’s model would either corrupt the government or corrupt the gospel. The gospel’s fundamental message is forgiveness, government must maintain justice. To confuse the two here is just as troubling as confusing them when discussing theology. If forgiveness becomes the dominant model in government, people being sinful, chaos will increase. If however, the government claims the gospel but acts on the basis of justice, then people will be misled as to the proper nature of the gospel.

Luther was self-consciously trying to carve out proper realms for revelation and philosophy or reason. Each had a proper role that enables humanity to thrive. Chaos only became a problem when the two got confused.One cannot understand Luther’s relationship to philosophy and his discussions of philosophy without understanding that key concept.

4. References and Further Reading

A. primary sources.

Key Primary Sources in English:

- Of all the major works of Luther, this is the best edition in English. It will soon be out on CD-Rom.

- Luther’s earliest lectures. These are important because we begin to see themes that will eventually become the Theology of the Cross.

- The patterns of the Theology of the Cross become a bit more evident. Many scholars believe that Luther made his final discovery of the doctrine of Justification by Faith while giving these lectures.

- The seminal document of the Reformation in Germany. These theses led to the eventual break with Rome over indulgences and grace.

- The best example of Luther’s emerging Theology of the Cross.He contrasts human works to God’s works in and through the Cross and shows the emptiness of human achievement and the importance of grace.

- Summary of his position that righteousness is received rather than achieved.

- Luther’s ethics, in which he explains that “A Christian is a perfectly free lord of all, subject to none. A Christian is perfectly dutiful servant of all, subject to all.”

- A call for reform in Germany, it highlights some of the complexity of Luther’s thought on church and state relations.

- A summary of the Law and Gospel.

- A summary of Luther’s understanding of Justification by Faith.

- Sets out Luther’s doctrine of the Two Kingdom’s most clearly.

- In a debate with Erasmus about human freedom and bondage to sin. Luther argues that humanity is bound to sin completely and only freed from that bondage by God’s Grace.

- Written before the Peasant’s War, it was published afterward.

- A summary of Christian doctrine, to be used in instruction.

- Luther’s first expression of a right to resist tyranny.

- A mature presentation of Luther’s doctrine on Justification.

- His anthropology, but also gives a glimpse of his understanding of the proper role of philosophy and reason.

b. Secondary Sources

Key Secondary Sources in English on the Life and Thought of Luther:

- The most popular biography of Luther, it is readeable and very thorough.

- The authoritative biography of Luther.

- An excellent introduction to the Reformation era.

- The best work on Luther’s political theology.

- One of the few books to focus on the older Luther. It is an excellent study in Luther after the Diet of Augsburg.

- The Theology of the Cross is a fundamental doctrine in Luther. Forde takes an new look at the doctrine in light of Luther’s role as pastor.

- This is an excellent introduction to Luther and puts his thought in dialogue with other major reformers, i.e., Zwingli and Calvin.

- The best introduction to the Reformation era, it covers not only the reformers but the context and culture of the era as well.

- The classic work on the Theology of the Cross.

- In a handbook format, this is an essential ready-reference to Luther and his works.

- This book covers the scholastic and nominalist background of the reformation.

- A classic that places the reformation era within the wider context of the late medieval era and the early modern era.

- An excellent biography of Luther that examines Luther in light of his quest for a gracious God and his fight against the Devil.

- Ozment places the reformation in a wider context and sees the impetus for reform stretching back into what is normally considered the High Medieval Era.

- Part of a five volume history of doctrine, Pelikan looks at the doctrinal issues at work in the reformation. He is not as concerned with history as he is with theological development.

- A thorough study of the wider issues raised by the reformation.

- A classic study stressing the theocentric nature of Luther’s thought.

Author Information

David M. Whitford Claflin University U. S. A.

An encyclopedia of philosophy articles written by professional philosophers.

Why Did Martin Luther Post the 95 Theses?

In the little town of Wittenberg, Germany, on this day, October 31, 1517 , a priest nailed a challenge to debate on the church door. No one may have noticed then, but within the week, copies of his theses would be discussed throughout the surrounding regions; and within a decade, Europe itself was shaken by his simple act. Later generations would mark Martin Luther's nailing of the 95 theses on the church door as the beginning of the Protestant Reformation, but what did Luther think he was doing at the time? To answer this question, we need to understand a little about Luther's own spiritual journey.

Martin Luther

As a young man in Germany at the beginning of the sixteenth century, Luther was studying law at the university. One day he was caught in a storm and was almost killed by lightning. He cried out to St. Anne and promised God he would become a monk. In 1505, Luther entered the Augustinian monastery and in 1507 became a priest. His monastic leaders sent him to Rome in 1510, but Luther was disenchanted with the ritualism and dead faith he found in the papal city. There was nothing in Rome to mend his despairing spirit or settle his restless soul. He seemed so cut off from God, and nowhere could he find a cure for his malady.

Martin Luther was bright, and his superiors soon had him teaching theology at the university. In 1515, he began teaching Paul's epistle to the Romans. Slowly, Paul's words in Romans began to break through the gloom of Luther's soul. Luther wrote

My situation was that, although an impeccable monk, I stood before God as a sinner troubled in conscience, and I had no confidence that my merit would assuage him. Night and day I pondered until I saw the connection between the justice of God and the statement 'the just shall live by faith.' Then I grasped that the justice of God is that righteousness by which through grace and sheer mercy God justifies us through faith. Thereupon I felt myself to be reborn and to have gone through open doors into paradise. The whole of Scripture took on a new meaning...This passage of Paul became to me a gate to heaven.

The more Luther's eyes were opened by his study of Romans, the more he saw the church's corruption in his day. The glorious truth of justification by faith alone had become buried under a mound of greed, corruption, and false teaching. Most galling was the practice of indulgences -- the certificates the church provided for a fee, supposedly to shorten one's stay in Purgatory. The pope was encouraging the sale of indulgences. He planned to use the money to help pay for the building of St. Peter's Basilica in Rome.

Johann Tetzel was one of the indulgence sellers in Luther's vicinity. He used little advertising jingles to encourage people to buy his wares: "As soon as the coin in the coffer rings, the soul from purgatory springs." Once Luther realized the sufficiency of Christ's sacrifice alone for our sins, he found such practices revolting. The more he studied the Scriptures, the more he saw the need to show the church how it had strayed from the truth.

Reason for the 95 Theses

So, on this day, October 31, 1517 , he posted a list of 95 propositions on the church door in Wittenberg. In his day, this was the means of inviting scholars to debate important issues. No one took up Luther's challenge to debate at that time, but once news of his proposals became known, many began to discuss the issue Luther raised that salvation was by faith in Christ's work alone. Luther initially expected the Pope to agree with his position since it was based on Scripture, but in 1520, the Pope issued a decree condemning Luther's views. Luther publicly burned the papal decree. With that act, he also burned his bridges behind him.

7 Postures for a Happy Marriage — Especially When Opposites Attract

Read the Full List of Luther's 95 Theses .

Photo Credit: WikimediaCommons

Bibliography:

- Adapted from an earlier Christian History Institute story.

- Bainton, Roland. Here I Stand. New York: Mentor, 1950.

- Durant, Will. The Reformation. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1957.

- Köstlin, Julius. Life of Luther. New York, C. Scribner's sons, 1884.

- Wells, Amos R. A Treasure of Hymns; Brief biographies of 120 leading hymn- writers and Their best hymns. Boston: W. A. Wilde company, 1945.

- Various encyclopedia articles.

Last updated July 2017.

2 Times Anger Is Acceptable in Marriage and 3 Times It’s Not

What Does it Really Mean to Love God with Your Whole Heart?

12 Beautiful Prayers for Mother's Day

6 Smart Moves and 8 Key Prayers to Improve Mental Health

Is Masturbation a Sin?

The Best Birthday Prayers to Celebrate Friends and Family

Morning Prayers to Start Your Day with God

Here are 5 marriage builders you don’t want to ignore.

Bible Baseball

Play now...

Saintly Millionaire

Bible Jeopardy

Bible Trivia By Category

Bible Trivia Challenge

About Church History

Read {2} by {3} and more articles about {1} and {0} on Christianity.com

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Martin Luther Might Not Have Nailed His 95 Theses to the Church Door

By: Becky Little

Updated: September 1, 2018 | Original: October 31, 2017

October 31 isn’t just Halloween , it’s also Reformation Day —the anniversary of Martin Luther nailing his 95 Theses to the door of the Wittenberg Castle church in Germany in 1517. His theses challenged the authority of the Catholic Church, and sparked the historic split in Christianity known as the Protestant Reformation . But 500 years later, scholars aren’t sure that the most dramatic part of the tale is true.

The new consensus is that he mailed his theses to an archbishop on October 31, but he probably didn’t nail them to the door to drive the point home.

The reason this is such a big deal is because the image of Luther nailing his 95 Theses to a church door is one of the main historical events people associate with the Reformation. Yet in a recently published book, 1517: Martin Luther and the Invention of the Reformation , Reformation historian Peter Marshall argues that Luther probably didn’t deliver his theses so theatrically. And according to Joan Acocella’s New Yorker article on Martin Luther’s influence, much of the latest scholarship agrees that the event likely didn’t happen.

“Not only were there no eyewitnesses; Luther himself, ordinarily an enthusiastic self-dramatizer, was vague on what had happened,” Acocella writes . “He remembered drawing up a list of ninety-five theses around the date in question, but, as for what he did with it, all he was sure of was that he sent it to the local archbishop.”

The fact that he might’ve mailed his theses rather than nailing them to the church door, while perhaps a bit disappointing, doesn’t change their impact. In the theses, Luther condemned the church’s selling of “indulgences,” which was based on the the idea that people could buy forgiveness for their sins. Instead, he argued that humans could only reach salvation through faith, and that the Bible, not the clergy, was the foremost religious authority.

These ideas shaped a new branch of Christianity, called Protestantism. Broadly defined, Protestants make up 37 percent of the world’s 2.18 billion Christians, according to the Pew Research Center.

True or not, the iconic image of Luther defiantly nailing his theses to a church door continues to reverberate as a symbol of religious freedom. In 1966, Martin Luther King, Jr. , echoed its symbolic power by placing a list of his demands on the door of the Chicago City Hall. It’s even become something of a meme: The Simpsons once aired a Halloween episode in which Lisa accidentally creates a functioning society in a petri dish, and excitedly observes that “one of them is nailing something to the door of the cathedral.”

The delivery method of the 95 Theses is not the only aspect of Luther’s life that scholars are reexamining. Historians have also been delving into his brutal anti-Semitism. In addition to the theses, Luther wrote a book called On the Jews and Their Lies , in which he posited that Jews were a menace to Germany. Scholar Dietz Bering , whose new book explores Luther’s anti-Semitism, told Public Radio International that Luther advocated burning Jewish synagogues and homes, confiscating Jewish money, forcing Jewish people into servitude, and expelling Jewish people from Germany.

Many of his fellow Protestants rejected these ideas at the time, but in the early 20th century, the Nazi Party would use them to demonstrate that anti-Semitism had a long history in Germany. Speaking on the 500th anniversary of the Reformation, German Chancellor Angela Merkel argued that Luther’s anti-Semitism is part of his theological legacy, and should never be glossed over, reports the Times of Israel .

“That is, for me,” Merkel said, “the comprehensive historical reckoning that we need.”

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

Martin Luther’s 95 Theses Are 500 Years Old. Here’s Why They’re Still Causing Controversy

Five hundred years ago , on Oct. 31, 1517, the small-town monk Martin Luther marched up to the castle church in Wittenberg and nailed his 95 Theses to the door, thus lighting the flame of the Reformation — the split between the Catholic and Protestant churches. Luther’s act is taught as one of the cornerstones of world history, and remains a lasting symbol of resistance five centuries later.

But that’s not actually what happened — or at least that’s the argument of some historians, even as the Protestant world celebrates the anniversary.

“The drama of Luther walking through Wittenberg with his hammer and his nails is very, very unlikely to have happened,” says Professor Andrew Pettegree, an expert on the Reformation from the University of St. Andrews, Scotland. “The castle church door was the normal noticeboard of the university. This was not an act of defiance on Luther’s part, it was simply what you did to make a formal publication. It would probably have been pasted to the door rather than nailed up.”

Peter Marshall would go even further. A historian of the Reformation at Warwick University, England, he believes there’s a strong case to be made that the Theses were never posted at all, and that the story was invented to suit the political needs of people who came later. “The incident was first recorded nearly 30 years after,” he says. “Luther himself never mentioned it. There was very little discussion of the nailing of the Theses before the first Reformation anniversary of 1617.”

In 1617, with the Thirty Years’ War on the horizon, a local ruler in the Rhineland area had the idea of organizing a centenary celebration to drum up Protestant solidarity, to increase his chances in the forthcoming fight with the Catholic Habsburgs. “It’s a very good example of history being made because of a current need to create a historical event,” says Pettegree, with an air of admiration.

But even if 2017’s big quincentenary isn’t quite what it seems, the legend that has grown up around the story of Luther nailing his Theses to the church door follows a precedent of historical events that have been remembered differently from the way they actually happened.

Memorials, whether state-led, socially constructed or personal, often do more than simply commemorate an anniversary.

Over the centuries, that 1517 date has been seen in a number of different ways. During the 400th anniversary in 1917, for example, the First World War was raging. At that time, Marshall says, Germans saw Luther’s posting of the Theses “as a quintessentially German and nationalist action — he was ‘ unser Luther ‘, our Luther.” That idea, in turn, was used to bolster German nationalism and morale during the war.

Over the following decades, the image was co-opted for different political ends. “The Nazis also appropriated the imagery of the posting of the Theses for their own purposes,” Marshall adds. “They saw themselves overthrowing a corrupt old order.”

Ironically, Luther would have hated to be seen as the calculating revolutionary who overthrew the old order, and most historians agree he wasn’t looking to start a “Reformation” in 1517. “Luther always thought of himself as a good Catholic,” Pettegree insists.

Today it’s the Catholic and Lutheran churches, more so than nation states, that are taking the memory of 1517 in their hands. This time last year, on the 499th anniversary, Pope Francis joined leaders of the Lutheran World Federation in Sweden to hold a joint service in a spirit of unity after 500 years of division. “We have the opportunity to mend a critical moment of our history by moving beyond the controversies and disagreements that have often prevented us from understanding one another,” he told the congregation.

Both churches are keen to use the anniversary to signal a definitive break with the past — another example of the way a memorial can be used for any number of ends.

“I suppose the danger with anniversaries is that they can serve to reinforce myths and entrenched narratives of the past, rather than encourage us to look afresh at historical events and processes,” Marshall says. “And there’s been a fair amount, especially in Germany, of uncritical celebration of the ‘achievements’ or ‘legacies’ of the Reformation — tolerance, liberal democracy, freedom of expression, scientific rationalism. All things Luther would have hated!”

More Must-Reads From TIME

- Putin’s Enemies Are Struggling to Unite

- Women Say They Were Pressured Into Long-Term Birth Control

- What Student Photojournalists Saw at the Campus Protests

- Scientists Are Finding Out Just How Toxic Your Stuff Is

- Boredom Makes Us Human

- John Mulaney Has What Late Night Needs

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Billy Perrigo at [email protected]

Martin Luther’s Birth and the Dawn of the Reformation

This essay about the profound impact of Martin Luther on the religious landscape of Europe, particularly through his role in the Protestant Reformation. It explores Luther’s upbringing, his theological evolution, and the revolutionary nature of his “95 Theses.” Luther’s bold challenge to Catholic doctrine and his advocacy for reform reshaped Christianity, catalyzing social, political, and cultural transformations across Europe. His legacy endures as a symbol of religious autonomy, challenging institutional authority and fostering individual conviction.

How it works

Martin Luther, an indispensable luminary in global annals, entered the world on November 10, 1483, in the modest hamlet of Eisleben within the Holy Roman Empire (now Germany). His existence and endeavors wrought a profound metamorphosis upon the religious terrain of Europe, laying the groundwork for the Protestant Reformation, an upheaval that fractured age-old conventions and permanently altered Christianity. To comprehend the import of his advent and the enduring resonance of his legacy, it is imperative to contextualize Luther’s milieu and how his notions kindled a religious, political, and cultural upheaval.

In 1483, Europe languished under the dominion of the Catholic Church, with the papacy exerting formidable authority over both spiritual and temporal realms. The populace adhered fervently to the Church’s tenets and rites, with the commerce of indulgences, purportedly granting absolution from purgatorial afflictions, being rife, and dissent against ecclesiastical practices largely quashed. Against this backdrop emerged Martin Luther, a harbinger of reform poised to challenge the Church’s hegemony.

Luther matured amidst a milieu steeped in religious orthodoxy, nurtured within the confines of a moderately affluent household, courtesy of his father, Hans Luther, a prosperous mining magnate. Hans aspired to a legal vocation for his progeny, thus steering Martin toward legal studies at the University of Erfurt. However, a profound existential crisis during a tempestuous tempest, construed by Luther as divine retribution, prompted his forsaking of legal pursuits to assume monastic vows in 1505, enlisting in the ranks of the Augustinian order.

His cloistered existence and theological scholarship exposed Luther to prevailing religious dogma while fomenting a profound disquietude within him. Perturbed by the Church’s doctrines concerning salvation and the commerce of indulgences, Luther underwent a spiritual odyssey culminating in the revolutionary assertion that salvation stemmed solely from faith, eschewing indulgence purchase or virtuous deeds. This tenet would underpin his theological credo, propelling him into the vortex of ecclesiastical tumult.

In 1517, Luther affixed his “95 Theses” to the portal of Wittenberg’s Castle Church, impugning ecclesiastical practices and advocating reform. This audacious gesture precipitated a cascade of events as Luther’s tenets disseminated expeditiously across Europe, buoyed by the advent of the printing press. His nativity thus denoted not merely the emergence of a sagacious theologian but heralded a seismic paradigm shift in religious cogitation. Luther’s insistence upon vernacular Bible translation, enabling direct access and interpretation by the laity, engendered novel modes of religious expression and autonomy.

The Reformation catalyzed by Luther engendered repercussions transcending religious precincts. It laid the foundation for nation-state ascension by contesting papal supranational dominion and galvanized educational reforms fostering widespread literacy. Moreover, it instigated the Counter-Reformation, wherein the Catholic Church endeavored to reaffirm doctrines while purging corruption.

Martin Luther’s advent thus inaugurated a trajectory redefining individual-institutional religious dynamics. His doctrines endure as an indelible influence upon Christian theology and praxis, epitomizing modern paradigms of religious liberty and personal conviction. From humble origins in Eisleben to a world-altering movement, Luther’s saga serves as a poignant testament to the transformative potential of ideas in reshaping historical trajectories.

Cite this page

Martin Luther's Birth and the Dawn of the Reformation. (2024, May 12). Retrieved from https://papersowl.com/examples/martin-luthers-birth-and-the-dawn-of-the-reformation/

"Martin Luther's Birth and the Dawn of the Reformation." PapersOwl.com , 12 May 2024, https://papersowl.com/examples/martin-luthers-birth-and-the-dawn-of-the-reformation/

PapersOwl.com. (2024). Martin Luther's Birth and the Dawn of the Reformation . [Online]. Available at: https://papersowl.com/examples/martin-luthers-birth-and-the-dawn-of-the-reformation/ [Accessed: 15 May. 2024]

"Martin Luther's Birth and the Dawn of the Reformation." PapersOwl.com, May 12, 2024. Accessed May 15, 2024. https://papersowl.com/examples/martin-luthers-birth-and-the-dawn-of-the-reformation/

"Martin Luther's Birth and the Dawn of the Reformation," PapersOwl.com , 12-May-2024. [Online]. Available: https://papersowl.com/examples/martin-luthers-birth-and-the-dawn-of-the-reformation/. [Accessed: 15-May-2024]

PapersOwl.com. (2024). Martin Luther's Birth and the Dawn of the Reformation . [Online]. Available at: https://papersowl.com/examples/martin-luthers-birth-and-the-dawn-of-the-reformation/ [Accessed: 15-May-2024]

Don't let plagiarism ruin your grade

Hire a writer to get a unique paper crafted to your needs.

Our writers will help you fix any mistakes and get an A+!

Please check your inbox.

You can order an original essay written according to your instructions.

Trusted by over 1 million students worldwide

1. Tell Us Your Requirements

2. Pick your perfect writer

3. Get Your Paper and Pay

Hi! I'm Amy, your personal assistant!

Don't know where to start? Give me your paper requirements and I connect you to an academic expert.

short deadlines

100% Plagiarism-Free

Certified writers

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

The Ninety-five Theses or Disputation on the Power and Efficacy of Indulgences is a list of propositions for an academic disputation written in 1517 by Martin Luther, then a professor of moral theology at the University of Wittenberg, Germany. The Theses is retrospectively considered to have launched the Protestant Reformation and the birth of Protestantism, despite various proto-Protestant ...

Martin Luther was a German theologian who challenged a number of teachings of the Roman Catholic Church. His 1517 document, "95 Theses," sparked the Protestant Reformation.

Ninety-five Theses, propositions for debate concerned with the question of indulgences, written in Latin and possibly posted by Martin Luther on the door of the Castle Church in Wittenberg on October 31, 1517. The event came to be considered the beginning of the Protestant Reformation.

This Day in History: 10/31/1517 - Martin Luther Posts Theses. On October 31, 1517, legend has it that the priest and scholar Martin Luther approaches the door of the Castle Church in Wittenberg ...

Luther's 97 theses on the topic of scholastic theology had been posted only a month before his 95 theses focusing on the sale of indulgences. Both writs were only intended to invite discussion of the topic. Martin Luther (l. 1483-1546) objected to scholastic theology on the grounds that it could not reveal the truth of God and denounced indulgences - writs sold by the Church to shorten one's ...

The 95 Theses. Out of love for the truth and from desire to elucidate it, the Reverend Father Martin Luther, Master of Arts and Sacred Theology, and ordinary lecturer therein at Wittenberg, intends to defend the following statements and to dispute on them in that place. Therefore he asks that those who cannot be present and dispute with him ...

Sometime during October 31, 1517, the day before the Feast of All Saints, the 33-year-old Martin Luther posted theses on the door of the Castle Church in Wittenberg. The door functioned as a ...

Ninety-five Theses, Propositions for debate on the question of indulgences, written by Martin Luther and, according to legend, posted on the door of the castle church in Wittenberg, Ger., on Oct. 31, 1517. This event is now seen as the beginning of the Protestant Reformation. The theses were written in response to the selling of indulgences to pay for the rebuilding of St. Peter's Basilica ...

Protestantism - Reformation, Luther, 95 Theses: Against the actions of Albert and Tetzel and with no intention to divide the church, Luther launched his Ninety-five Theses on October 31, 1517. In the theses he presented three main points. The first concerned financial abuses; for example, if the pope realized the poverty of the German people, he would rather that St. Peter's lay in ashes ...

Martin Luther was a German monk who forever changed Christianity when he nailed his '95 Theses' to a church door in 1517, sparking the Protestant Reformation.

The Ninety-five Theses by Martin Luther October 31, 1517, Wittenberg, Germany 2 Theses #15 - 82 are the core arguments by Martin Luther against indulgences and the tactics of the preachers who are selling letters of indulgence in Germany. 15. This fear of horror is sufficient in itself, to say nothing of other things, to constitute the

The date was Oct. 31, 1517, and Luther had just lit the fuse of what would become the Protestant Reformation. His list of criticisms, known as the 95 theses, would reverberate across world history ...

The letter comes to be known as The 95 Theses. Although there is some doubt as to the matter, the 95 Theses were probably also posted on the door of All Saint's Church ("Castle Church") in Wittenberg. Within a few months, the 95 Theses were translated from Latin into German and widely distributed throughout Europe. ... Martin Luther dies at age ...

Martin Luther (1483—1546) German theologian, professor, pastor, and church reformer. Luther began the Protestant Reformation with the publication of his Ninety-Five Theses on October 31, 1517. In this publication, he attacked the Church's sale of indulgences. He advocated a theology that rested on God's gracious activity in Jesus Christ ...

Reason for the 95 Theses. So, on this day, October 31, 1517, he posted a list of 95 propositions on the church door in Wittenberg. In his day, this was the means of inviting scholars to debate important issues. No one took up Luther's challenge to debate at that time, but once news of his proposals became known, many began to discuss the issue ...

Luther never intended, initially, to challenge the church hierarchy or the pope. Martin Luther's 95 Theses of 1517 were an invitation to discuss policies and practices of the Church he found troublesome and unbiblical. The original document, written in Latin, was intended for an ecclesiastical audience, but it was translated into German by his friends and supporters, and thanks to the advent ...

Martin Luther's Disputatio pro declaratione virtutis indulgentiarum of 1517, commonly known as the Ninety-Five Theses, is considered the central document of the Protestant Reformation. Its complete title reads: "Out of love and zeal for clarifying the truth, these items written below will be debated at Wittenberg. Reverend Father Martin Luther, Master of Arts and of Sacred Theology and an ...

Prisma/UIG/Getty Images. Martin Luther nailing his 95 theses to the door of the Wittenberg Castle Church. The fact that he might've mailed his theses rather than nailing them to the church door ...

October 31, 2017 9:00 AM EDT. Five hundred years ago, on Oct. 31, 1517, the small-town monk Martin Luther marched up to the castle church in Wittenberg and nailed his 95 Theses to the door, thus ...

Luther's Conflict with the Church. Martin Luther (l. 1483-1546) had posted his 95 Theses, in Latin, at Wittenberg on 31 October 1517 as a simple call for scholarly debate among clergy on the matter of indulgences.A copy sent to his archbishop, Albrecht von Brandenburg, was passed on to the pope - elevating the theses to an official matter of the Church - while Luther's followers translated ...

Martin Luther. Born: November 10, 1483, Eisleben, Saxony [now in -Anhalt, Germany] Died: February 18, 1546, Eisleben (aged 62) Notable Works: "Ninety-five Theses". "Admonition to Peace Concerning the Twelve Articles of the Peasants". "Against the Execrable Bull of the AntiChrist".

Martin Luther OSA (/ ˈ l uː θ ər /; German: [ˈmaʁtiːn ˈlʊtɐ] ⓘ; 10 November 1483 - 18 February 1546) was a German priest, theologian, author, hymnwriter, professor, and Augustinian friar. Luther was the seminal figure of the Protestant Reformation, and his theological beliefs form the basis of Lutheranism.He is regarded as one of the most influential figures in Western and ...

Martin Luther, an indispensable luminary in global annals, entered the world on November 10, 1483, in the modest hamlet of Eisleben within the Holy Roman Empire (now Germany). His existence and endeavors wrought a profound metamorphosis upon the religious terrain of Europe, laying the groundwork for the Protestant Reformation, an upheaval that ...

Here I Stand: A Life of Martin Luther. Abingdon Press, 2013. Martin Luther's 95 Theses from Reasonable Theology Accessed 29 Nov 2021. Roper, L. Martin Luther: Renegade and Prophet. Random House Trade Paperbacks, 2018. Rublack, U. The Oxford Handbook of the Protestant Reformations . Oxford University Press, 2017.