VIDEO COURSE

Finish your draft in our 3-month master class. Sign up now to watch a free lesson!

Learn How to Write a Novel

Finish your draft in our 3-month master class. Enroll now for daily lessons, weekly critique, and live events. Your first lesson is free!

Blog • Perfecting your Craft

Last updated on Jun 23, 2023

How to Write a Novel: 13-Steps From a Bestselling Writer [+Templates]

This post is written by author, editor, and ghostwriter Tom Bromley. He is the instructor of Reedsy's 101-day course, How to Write a Novel .

Writing a novel is an exhilarating and daunting process. How do you go about transforming a simple idea into a powerful narrative that grips readers from start to finish? Crafting a long-form narrative can be challenging, and it requires skillfully weaving together various story elements.

In this article, we will break down the major steps of novel writing into manageable pieces, organized into three categories — before, during, and after you write your manuscript.

How to write a novel in 13 steps:

1. Pick a story idea with novel potential

2. develop your main characters, 3. establish a central conflict and stakes, 4. write a logline or synopsis, 5. structure your plot, 6. pick a point of view, 7. choose a setting that benefits your story , 8. establish a writing routine, 9. shut out your inner editor, 10. revise and rewrite your first draft, 11. share it with your first readers, 12. professionally edit your manuscript, 13. publish your novel.

Every story starts with an idea.

You might be lucky, like JRR Tolkien, who was marking exam papers when a thought popped into his head: ‘In a hole in the ground there lived a hobbit.’ You might be like Jennifer Egan, who saw a wallet left in a public bathroom and imagined the repercussions of a character stealing it, which set the Pulitzer prize-winner A Visit From the Goon Squad in process. Or you might follow Khaled Hosseini, whose The Kite Runner was sparked by watching a news report on TV.

Many novelists I know keep a notebook of ideas both large and small 一 sometimes the idea they pick up on they’ll have had much earlier, but whatever reason, now feels the time to write it. Certainly, the more ideas you have, the more options you’ll have to write.

✍️ Need a little inspiration? Check our list of 30+ story ideas for fiction writing , our list of 300+ writing prompts , or even our plot generator .

Is your idea novel-worthy?

How do you know if what you’ve got is the inspiration for a novel, rather than a short story or a novella ? There’s no definitive answer here, but there are two things to look out for

Firstly, a novel allows you the space to show how a character changes over time, whereas a short story is often more about a vignette or an individual moment. Secondly, if an idea is fit for a novel, it’ll nag away at you: a thread asking to be pulled to see where it goes. If you find yourself coming back to an idea, then that’s probably one to explore.

I expand on how to cultivate and nurture your ‘idea seeds’ in my free 10-day course on novel writing.

FREE COURSE

How to Write a Novel

Author and ghostwriter Tom Bromley will guide you from page 1 to the finish line.

Another starting point (or essential element) for writing a novel will come in the form of the people who will populate your stories: the protagonists.

My rule of thumb in writing is that a reader will read on for one of two reasons: either they care about the characters , or they want to know what happens next (or, in an ideal world, both). Now different people will tell you that character or plot are the most important element when writing.

In truth, it’s a bit more complicated than that: in a good novel, the main character or protagonist should shape the plot, and the plot should shape the protagonist. So you need both core elements in there, and those two core elements are entwined rather than being separate entities.

Characters matter because when written well, readers become invested in what happens to them. You can develop the most brilliant, twisty narrative, but if the reader doesn’t care how the protagonist ends up, you’re in trouble as a writer.

As we said above, one of the strengths of the novel is that it gives you the space to show how characters change over time. How do characters change?

Firstly, they do so by being put in a position where they have to make decisions, difficult decisions, and difficult decisions with consequences . That’s how we find out who they really are.

Secondly, they need to start from somewhere where they need to change: give them flaws, vulnerabilities, and foibles for them to overcome. This is what makes them human — and the reason why readers respond to and care about them.

FREE RESOURCE

Reedsy’s Character Profile Template

A story is only as strong as its characters. Fill this out to develop yours.

🗿 Need more guidance? Look into your character’s past using these character development exercises , or give your character the perfect name using this character name generator .

As said earlier, it’s important to have both a great character and an interesting plot, which you can develop by making your character face some adversities.

That drama in the novel is usually built around some sort of central conflict . This conflict creates a dramatic tension that compels the reader to read on. They want to see the outcome of that conflict resolved: the ultimate resolution of the conflict (hopefully) creates a satisfying ending to the narrative.

A character changes, as we said above, when they are put in a position of making decisions with consequences. Those consequences are important. It isn’t enough for a character to have a goal or a dream or something they need to achieve (to slay the dragon): there also needs to be consequences if they don’t get what they’re after (the dragon burns their house down). Upping the stakes heightens the drama all round.

Now you have enough ingredients to start writing your novel, but before you do that, it can be useful to tighten them all up into a synopsis.

GET ACCOUNTABILITY

Meet writing coaches on Reedsy

Industry insiders can help you hone your craft, finish your draft, and get published.

So far you’ve got your story idea, your central characters and your sense of conflict and stakes. Now is the time to distill this down into a narrative. Different writers approach this planning stage in different ways, as we’ll come to in a moment, but for anyone starting a novel, having a clear sense of what is at the heart of your story is crucial.

There are a lot of different terms used here 一 pitch, elevator pitch , logline, shoutline, or the hook of your synopsis 一 but whatever the terminology the idea remains the same. This is to summarize your story in as few words as possible: a couple of dozen words, say, or perhaps a single sentence.

This exercise will force you to think about what your novel is fundamentally about. What is the conflict at the core of the story? What are the challenges facing your main protagonist? What do they have at stake?

📚 Check out these 48 irresistible book hook examples and get inspired to craft your own.

If you need some help, as you go through the steps in this guide, you can fill in this template:

My story is a [genre] novel. It’s told from [perspective] and is set in [place and time period] . It follows [protagonist] , who wants [goal] because [motivation] . But [conflict] doesn’t make that easy, putting [stake] at risk.

It's not an easy thing to do, to write this summarising sentence or two. In fact, they might be the most difficult sentences to get down in the whole writing process. But it is really useful in helping you to clarify what your book is about before you begin. When you’re stuck in the middle of the writing, it will be there for you to refer back to. And further down the line, when you’ve finished the novel, it will prove invaluable in pitching to agents , publishers, and readers.

📼 Learn more about the process of writing a logline from professional editor Jeff Lyons.

Another particularly important step to prepare for the writing part, is to outline your plot into different key story points.

There’s no right answer here as to how much planning you should do before you write: it very much depends on the sort of writer you are. Some writers find planning out their novel before start gives them confidence and reassurance knowing where their book is going to go. But others find this level of detail restrictive: they’re driven more by the freedom of discovering where the writing might take them.

This is sometimes described as a debate between ‘planners’ and ‘pantsers’ (those who fly by the seat of their pants). In reality, most writers sit somewhere on a sliding scale between the two extremes. Find your sweet spot and go from there!

If you’re a planning type, there’s plenty of established story structures out there to build your story around. Popular theories include the Save the Cat model and Christopher Vogler’s Hero’s Journey . Then there are books such as Christopher Booker’s The Seven Basic Plots , which suggests that all stories are one of, well, you can probably work that out.

Whatever the structure, most stories follow the underlying principle of having a beginning, middle and end (and one that usually results in a process of change). So even if you’re ‘pantsing’ rather than planning, it’s helpful to know your direction of travel, though you might not yet know how your story is going to get there.

How to Plot a Novel in Three Acts

In 10 days, learn how to plot a novel that keeps readers hooked

Finally, remember what we said earlier about plot and character being entwined: your character’s journey shouldn’t be separate to what happens in the story. Indeed, sometimes it can be helpful to work out the character’s journey of change first, and shape the plot around that, rather than the other way round.

Now, let’s consider which perspective you’re going to write your story from.

However much plotting you decide to do before you start writing, there are two further elements to think about before you start putting pen to paper (or finger to keyboard). The first one is to think about which point of view you’re going to tell your story from. It is worth thinking about this before you start writing because deciding to change midway through your story is a horribly thankless task (I speak from bitter personal experience!)

Understanding Point of View

Learn to master different POVs and choose the best for your story.

Although there might seem a large number of viewpoints you could tell your story from, in reality, most fiction is told from two points of view 一 first person (the ‘I’ form) and third person ‘close’ (he/she/they). ‘Close’ third person is when the story is witnessed from one character’s view at a time (as opposed to third person ‘omniscient’ where the story can drop into lots of people’s thoughts).

Both of these viewpoints have advantages and disadvantages. First person is usually better for intimacy and getting into character’s thoughts: the flip side is that its voice can feel a bit claustrophobic and restrictive in the storytelling. Third person close offers you more options and more space to tell your story: but can feel less intimate as a result.

There’s no right and wrong here in terms of which is the ‘best’ viewpoint. It depends on the particular demands of the story that you are wanting to write. And it also depends on what you most feel comfortable writing in. It can be a useful exercise to write a short section in both viewpoints to see which feels the best fit for you before starting to write.

Which POV is right for your book?

Take our quiz to find out! Takes only 1 minute.

Besides choosing a point of view, consider the setting you’re going to place your story in.

The final element to consider before beginning your story is to think about where your story is going to be located . Settings play a surprisingly important part in bringing a story to life. When done well, they add in mood and atmosphere, and can act almost like an additional character in your novel.

There are many questions to consider here. And again, it depends a bit on the demands of the story that you are writing.

Is your setting going to a real place, a fictional one, or a real place with fictional elements? Is it going to be set in the present day, the past, or at an unspecified time? Are you going to set your story in somewhere you know, or need to research to capture properly? Finally, is your setting suited to the story you are telling, and serve to accentuate it, rather than just acting as a backdrop?

If you’re writing a novel in genres such as fantasy or science fiction , then you may well need to go into some additional world-building as well before you start writing. Here, you may have to consider everything from the rules and mores of society to the existence of magical powers, fantastic beasts, extraterrestrials, and futuristic technology. All of these can have a bearing on the story, so it is better to have a clear setup in your head before you start to write.

The Ultimate Worldbuilding Template

130 questions to help create a world readers want to visit again and again.

Whether your story is set in central London or the outer rings of the solar system, some elements of the descriptive detail remain the same. Think about the use of all the different senses — the sights, sounds, smells, tastes, and textures of where you’re writing about. Those sorts of small details can help to bring any setting to life, from the familiar to the imaginary.

Alright, enough brainstorming and planning. It’s time to let the words flow on the page.

Having done your prep — or as much prep and planning as you feel you need — it’s time to get down to business and write the thing. Getting a full draft of a novel is no easy task, but you can help yourself by setting out some goals before you start writing.

Firstly, think about how you write best. Are you a morning person or an evening person? Would you write better at home or out and about, in a café or a library, say? Do you need silence to write, or musical encouragement to get the juices flowing? Are you a regular writer, chipping away at the novel day by day, or more of a weekend splurger?

How to Build a Solid Writing Routine

In 10 days, learn to change your habits to support your writing.

I’d always be wary of anyone who tells you how you should be writing. Find a routine and a setup that works for you . That might not always be the obvious one: the crime writer Jo Nesbø spent a while creating the perfect writing room but discovered he couldn’t write there and ended up in the café around the corner.

You might not keep the same way of writing throughout the novel: routines can help, but they can also become monotonous. You may need to find a way to shake things up to keep going.

Deadlines help here. If you’re writing a 75,000-word novel, then working at a pace of 5,000 words a week will take you 15 weeks (Monday to Friday, that’s 1000 words a day). Half the pace will take twice as long. Set yourself a realistic deadline to finish the book (and key points along the way). Without a deadline, the writing can end up drifting, but it needs to be realistic to avoid giving yourself a hard time.

In my experience, writing speeds vary. I tend to start quite slowly on a book, and speed up towards the end. There are times when the tap is open, and the words are pouring out: make the most of those moments. There are times, too, when each extra sentence feels like torture: don’t beat yourself up here. Be kind to yourself: it’s a big, demanding project you’re undertaking.

Speaking of self-compassion, a word on that harsh editor inside your mind…

The other important piece of advice is to continue writing forward. It is very easy, and very tempting, to go back over what you’ve written and give it a quick edit. Once you start down that slippery slope, you end up rewriting and reworking the same scene and never get any further forwards in the text. I know of writers who spent months perfecting their first chapter before writing on, only to delete that beginning as the demands of the story changed.

The first draft of your novel isn’t about perfection; it’s about getting the words down. One writer I work with calls it the ‘vomit draft’ — getting everything out and onto the page. It’s only once you’ve got a full manuscript down that you can see your ideas in context and have the capacity to edit everything properly. So as much as your inner editor might be calling you, resist! They’ll have their moment in the sun later on. For now, it’s about getting a complete version down, that you can go on to work with and shape.

By now, you’ve reached the end of your first draft (we might be glossing over the hard writing part just a little here: if you want more detail and help on how to get through to the end of your draft, our How to Write A Novel course is warmly recommended).

NEW REEDSY COURSE

Enroll in our course and become an author in three months.

Reaching the end of your first draft is an important milestone in the journey of a book. Sadly for those who feel that this is the end of the story, it’s actually more of a stepping stone than the finish line.

In some ways, now the hard work begins. The difference between wannabe writers and those who get published can often be found in the amount of rewriting done. Professional writers will go back and back over what they’ve written, honing what they’ve created until the text is as tight and taut as it is possible to be.

How do you go about achieving this? The first thing to do upon finishing is to put the manuscript in a drawer. Leave it for a month or six weeks before you come back to it. That way, you’ll return the script with a fresh pair of eyes. Read it back through and be honest about what works and what doesn’t. As you read the script, think in particular about pace: are there sections in the novel that are too fast or too slow? Avoid the trap of the saggy middle . Then consider: is your character arc complete and coherent? Look at the big-picture stuff first before you tackle the smaller details.

Edit your novel closely

On that note, here are a few things you might want to keep an eye out for:

Show, don’t tell. Sometimes, you just need to state something matter-of-factly in your novel, that’s fine. But, as much as you can, try to illustrate a point instead of just stating it . Keep in mind the words of Anton Chekhov: “Don’t tell me the moon is shining. Show me the glint of light on broken glass."

“Said” is your friend. When it comes to dialogue, there can be the temptation to spice things up a bit by using tags like “exclaimed,” “asserted,” or “remarked.” And while there might be a time and place for these, 90% of the time, “said” is the best tag to use. Anything else can feel distracting or forced.

Stay away from purple prose. Purple prose is overly embellished language that doesn’t add much to the story. It convolutes the intended message and can be a real turn-off for readers.

Get our Book Editing Checklist

Resolve every error, from plot holes to misplaced punctuation.

Once you feel it’s good enough for other people to lay their eyes on it, it’s time to ask for feedback.

Writing a novel is a two-way process: there’s you, the writer, and there’s the intended audience, the reader. The only way that you can find out if what you’ve written is successful is to ask people to read and get feedback.

Think about when to ask for feedback and who to ask it from. There are moments in the writing when feedback is useful and others where it gets in the way. To save time, I often ask for feedback in those six weeks when the script is in the drawer (though I don’t look at those comments until I’ve read back myself first). The best people to ask for feedback are fellow writers and beta readers : they know what you’re going through and will also be most likely to offer you constructive feedback.

Also, consider working with sensitivity readers if you are writing about a place or culture outside your own. Friends and family can also be useful but are a riskier proposition: they might be really helpful, but equally, they might just tell you it’s great or terrible, neither of which is overly useful.

Feedbacking works best when you can find at least a few people to read, and you can pool their comments. My rule is that if more than one person is saying the same thing, they are probably right. If only one person is saying something, then you have a judgment call to make as to whether to take those comments further (though usually, you’ll know in your gut whether they are right or not.)

Overall, the best feedback you can receive is that of a professional editor…

Once you’ve completed your rewrites and taken in comments from your chosen feedbackers, it’s time to take a deep breath and seek outside opinions. What happens next here depends on which route you want to take to market:

If you want to go down the traditional publishing route , you’ll probably need to get a literary agent, which we’ll discuss in a moment.

If you’re going down the self-publishing route , you’ll need to do what would be done in a traditional publishing house and take your book through the editing process. This normally happens in three stages.

Developmental editing. The first of these is to work with a development editor , who will read and critique your work primarily from a structural point of view.

Copy-editing. Secondly, the book must be copy-edited , where an editor works more closely, line-by-line, on the script.

Proofreading. Finally, usually once the script has been typeset, then the material should be professionally proofread , to spot any final mistakes or orrors. Sorry, errors!

Finding such people can sound like a daunting task. But fear not! Here at Reedsy, we have a fantastic fleet of editors of all shapes, sizes, and experiences. So whatever your needs or requirements, we should be able to pair you with an editor to suit.

MEET EDITORS

Polish your book with expert help

Sign up, meet 1500+ experienced editors, and find your perfect match.

Now that you’ve ironed out all the wrinkles of your manuscript, it’s time to release it into the wild.

For those thinking about going the traditional publishing route , now’s the time for you to get to work. Most trade publishers will only accept work from a literary agent, so you’ll need to find a suitable literary agent to represent your work.

The querying process is not always straightforward: it involves research, waiting and often a lot of rejections until you find the right person (I was rejected by 24 agents before I found my first agent). Usually, an agent will ask to see a synopsis and the first three chapters (check their websites for submission details). If they like what they read, they’ll ask to see the whole thing.

If you’re self-publishing, you’ll need to think about getting your finished manuscript to market. You’ll need to get it typeset (laid out in book form) and find a cover designer . Do you want to sell printed copies or just ebooks? You’ll need to work out how to work Amazon , where a lot of your sales will come from, and also how you’ll market your book .

For those picked up by a traditional publisher, all the editing steps discussed will take place in-house. That might sound like a smoother process, but the flip side can be less control over the process: a publisher may have the final say in the cover or the title, and lead times (when the book is published) are usually much longer. So it’s worth thinking about which route to market works best for you.

Finally, you’re a published author! Congratulations. Now all you have to do is think about writing the next one…

As an editor and publisher, Tom has worked on several hundred titles, again including many prize-winners and international bestsellers.

8 responses

Sasha Winslow says:

14/05/2019 – 02:56

I started writing in February 2019. It was random, but there was an urge to the story I wanted to write. At first, I was all over the place. I knew the genre I wanted to write was Fantasy ( YA or Adult). That has been my only solid starting point the genre. From February to now, I've changed my story so many times, but I am happy to say by giving my characters names I kept them. I write this all to say is thank you for this comprehensive step by step. Definitely see where my issues are and ways to fix it. Thank you, thank you, thank you!

Evelyn P. Norris says:

30/10/2019 – 14:18

My number one tip is to write in order. If you have a good idea for a future scene, write down the idea for the scene, but do NOT write it ahead of time. That's a major cause of writer's block that I discovered. Write sequentially. :) If you can't help yourself, make sure you at least write it in a different document, and just ignore that scene until you actually get to that part of the novel

Allen P. Wilkinson says:

28/01/2020 – 04:51

How can we take your advice seriously when you don’t even know the difference between stationary and stationery? Makes me wonder how competent your copy editors are.

↪️ Martin Cavannagh replied:

29/01/2020 – 15:37

Thanks for spotting the typo!

↪️ Chris Waite replied:

14/02/2020 – 13:17

IF you're referring to their use of 'stationery' under the section '1. Nail down the story idea' (it's the only reference on this page) then the fact that YOU don't know the difference between stationery and stationary and then bother to tell the author of this brilliant blog how useless they must be when it's YOU that is the thicko tells me everything I need to know about you and your use of a middle initial. Bellend springs to mind.

Sapei shimrah says:

18/03/2020 – 13:59

Thanks i will start writing now

Jeremy says:

25/03/2020 – 22:41

I’ve run the gamut between plotter and pantser, but lately I’ve settled on in-depth plotting before my novels. It’s hard for me to do focus wise, but I’m finding I’m spending less time in writer’s block. What trips me up more is finding the right voice for my characters. I’m currently working on a sci-fi YA novel and using the Save the Cat beat sheet for structure for the first time. Thank you for the article!

Nick Girdwood says:

29/04/2020 – 10:32

Can you not write a story without some huge theme?

Comments are currently closed.

Continue reading

Recommended posts from the Reedsy Blog

What is Tone in Literature? Definition & Examples

We show you, with supporting examples, how tone in literature influences readers' emotions and perceptions of a text.

Writing Cozy Mysteries: 7 Essential Tips & Tropes

We show you how to write a compelling cozy mystery with advice from published authors and supporting examples from literature.

Man vs Nature: The Most Compelling Conflict in Writing

What is man vs nature? Learn all about this timeless conflict with examples of man vs nature in books, television, and film.

The Redemption Arc: Definition, Examples, and Writing Tips

Learn what it takes to redeem a character with these examples and writing tips.

How Many Sentences Are in a Paragraph?

From fiction to nonfiction works, the length of a paragraph varies depending on its purpose. Here's everything you need to know.

Narrative Structure: Definition, Examples, and Writing Tips

What's the difference between story structure and narrative structure? And how do you choose the right narrative structure for you novel?

Join a community of over 1 million authors

Reedsy is more than just a blog. Become a member today to discover how we can help you publish a beautiful book.

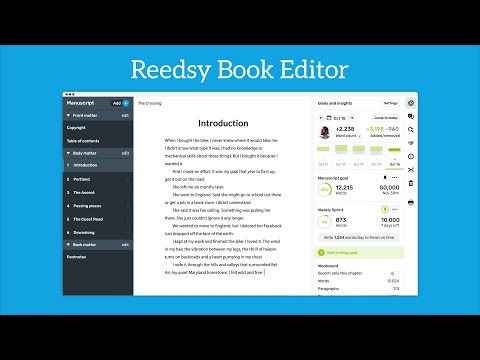

We made a writing app for you

Yes, you! Write. Format. Export for ebook and print. 100% free, always.

1 million authors trust the professionals on Reedsy. Come meet them.

Enter your email or get started with a social account:

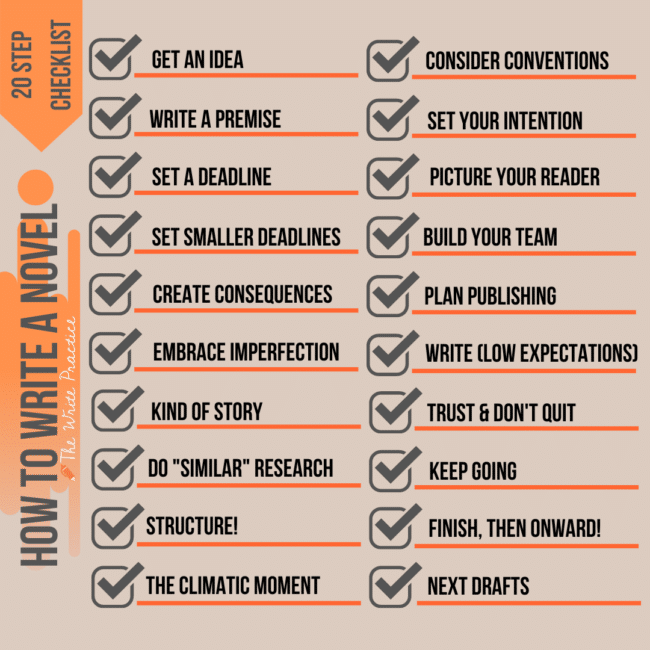

How to Write a Novel (Without Fail): The Ultimate 20-Step Guide

by Joe Bunting | 0 comments

Want to Become a Published Author? In 100 Day Book, you’ll finish your book guaranteed. Learn more and sign up here.

What if you could learn how to write a novel without fail? What if you had a process so foolproof, you knew you would finish no matter what writer's block throws at you? The zombie apocalypse could finally strike and you’d still face the blank page to finish your novel.

Every day I talk to writers who don’t know how to write a novel. They worry they don’t have what it takes, and honestly, they’re right to worry.

Writing a novel, especially for the first time, is hard work, and the desk drawers and hard drives of many a great writer are filled with the skeletons of incomplete and failed books.

The good news is you don't have to be one of those failed writers.

You can be a writer that writes to the end.

You can be the kind of writer who masters how to write a novel.

Table of Contents

Looking for something specific? Jump straight to it here:

1. Get a great idea 2. Write your idea as a premise 3. Set a deadline 4. Set smaller deadlines building to the final deadline 5. Create a consequence 6. Strive for “good enough” and embrace imperfection 7. Figure out what kind of story you’re trying to tell 8. Read novels and watch films that are similar to yours 9. Structure, structure, structure! 10. Find the climactic moment in your novel 11. Consider the conventions 12. Set your intention 13. Picture your reader 14. Build your team 15. Plan the publishing process 16. Write (with low expectations) 17. Trust the process and don’t quit 118. Keep going, even when it hurts 19. Finish Draft One . . . then onward to the next 20. Draft 2, 3, 4, 5 Writers’ Best Tips on How to Write a Novel FAQ

My Journey to Learn How to Write a Novel

My name is Joe Bunting .

I used to worry I would never write a novel. Growing up, I dreamed about becoming a great novelist, writing books like the ones I loved to read. I had even tried writing novels, but I failed again and again.

So I decided to study creative writing in college. I wrote poems and short stories. I read books on writing. I earned an expensive degree.

But still, I didn’t know how to write a novel.

After college I started blogging, which led to a few gigs at a local newspaper and then a national magazine. I got a chance to ghostwrite a nonfiction book (and get paid for it!). I became a full-time, professional writer.

But even after writing a few books, I worried I didn’t have what it takes to write a novel. Novels just seemed different, harder somehow. No writing advice seemed to make it less daunting.

Maybe it was because they were so precious to me, but while writing a nonfiction book no longer intimidated me—writing a novel terrified me.

Write a novel? I didn’t know how to do it.

Until, one year later, I decided it was time. I needed to stop stalling and finally take on the process.

I crafted a plan to finish a novel using everything I’d ever learned about the book writing process. Every trick, hack, and technique I knew.

And the process worked.

I finished my novel in 100 days.

Today, I’m a Wall Street Journal bestselling author of thirteen books, and I'm passionate about teaching writers how to write and finish their books. (FINISH being the key word here.)

I’ve taught this process to hundreds of other writers who have used it to draft and complete their novels.

And today, I'm going to teach my “how to write a novel” process to you, too. In twenty manageable steps !

As I do this, I’ll share the single best novel writing tips from thirty-seven other fiction writers that you can use in your novel writing journey—

All of which is now compiled and constructed into The Write Planner : our tangible planning guide for writers that gives you this entire process in a clear, actionable, and manageable way.

If you’ve ever felt discouraged about not finishing your novel, like I did, or afraid that you don’t have what it takes to build a writing career, I’m here to tell you that you can.

There's a way to make your writing easier.

Smarter, even.

You just need to have the “write” process.

How to Write a Novel: The Foolproof, 20-Step Plan

Below, I’m going to share a foolproof process that anyone can use to write a novel, the same process I used to write my novels and books, and that hundreds of other writers have used to finish their novels too.

1. Get a Great Idea

Maybe you have a novel idea already. Maybe you have twenty ideas.

If you do, that’s awesome. Now, do this for me: Pat yourself on the back, and then forget any feeling of joy or accomplishment you have.

Here’s the thing: an idea alone, even a great idea, is just the first baby step in writing your book. There are nineteen more steps, and almost all of them are more difficult than coming up with your initial idea.

I love what George R.R. Martin said:

“Ideas are useless. Execution is everything.”

You have an idea. Now learn how to execute, starting with step two.

(And if you don’t have a novel idea yet, here’s a list of 100 story ideas that will help, or you can view our genre specific lists here: sci-fi ideas , thriller ideas , mystery ideas , romance ideas , and fantasy ideas . You can also look at the Ten Best Novel Ideas here . Check those out, then choose an idea or make up one of your own, When you're ready, come back for step two.)

2. Write Your Idea As a Premise

Now that you have a novel idea , write it out as a single-sentence premise.

What is a premise, and why do you need one?

A premise distills your novel idea down to a single sentence. This sentence will guide your entire writing and publishing process from beginning to end. It hooks the reader and captures the high stakes (and other major details) that advance and challenge the protagonist and plot.

It can also be a bit like an elevator pitch for your book. If someone asks you what your novel is about, you can share your premise to explain your story—you don't need a lengthy description.

Also, a premise is the most important part of a query letter or book proposal, so a good premise can actually help you get published.

What’s an example of a novel premise ?

Here’s an example from The Wizard of Oz by L. Frank Baum:

A young girl is swept away to a magical land by a tornado and must embark on a quest to see the wizard who can help her return home.

Do you see the hooks? Young girl, magical land, embark on a quest (to see the wizard)—and don't forget her goal to return home.

This premise example very clearly contains the three elements every premise needs in order to stand out:

- A protagonist described in two words, e.g. a young girl or a world-weary witch.

- A goal. What the protagonist wants or needs.

- A situation or crisis the protagonist must face.

Ready to write your premise? We have a free worksheet that will guide you through writing a publishable premise: Download the worksheet here.

3. Set a Deadline

Before you do anything else, you need to set a deadline for when you’re going to finish the first draft of your novel.

Stephen King said a first draft should be written in no more than a season, so ninety days. National Novel Writing Month, or NaNoWriMo, exists to encourage people to write a book in just thirty days.

In our 100 Day Book Program, we give people a little longer than that, 100 days, which seems like a good length of time for most people (me included!).

I recommend setting your deadline no longer than four months. If it’s longer than that, you’ll procrastinate. A good length of time to write a book is something that makes you a little nervous, but not outright terrified.

Mark the deadline date in your calendar, kneel on the floor, close your eyes, and make a vow to yourself and your book idea that you will write the first draft novel by then, no matter what.

4. Set Smaller Deadlines Building to the Final Deadline

A novel can’t be written in a day. There’s no way to “cram” for a novel. The key to writing (and finishing) a novel is to make a little progress every day.

If you write a thousand words a day, something most people are capable of doing in an hour or two, for 100 days , by the end you’ll have a 100,000 word novel—which is a pretty long novel!

So set smaller, weekly deadlines that break up your book into pieces. I recommend trying to write 5,000 to 6,000 words per week by each Friday or Sunday, whichever works best for you. Your writing routine can be as flexible as you like, as long as you are hitting those smaller deadlines.

If you can hit all of your weekly deadlines, you know you’ll make your final deadline at the end.

As long as you hold yourself accountable to your smaller, feasible, and prioritized writing benchmarks.

5. Create a Consequence

You might think, “Setting a deadline is fine, but how do I actually hit my deadline?” Here’s a secret I learned from my friend Tim Grahl :

You need to create a consequence.

Try by taking these steps:

- Set your deadline.

- Write a check to an organization or nonprofit you hate (I did this during the 2016 U.S. presidential election by writing a check to the campaign of the candidate I liked least, whom shall remain nameless).

- Think of two other, minor consequences (like giving up your favorite TV show for a month or having to buy ice cream for everyone at work).

- Give your check, plus your list of two minor consequences, to a friend you trust with firm instructions to hold you to your consequences if you don’t meet your deadlines.

- If you miss one of your weekly deadlines, suffer one of your minor consequences (e.g. give up your favorite TV show).

- If you miss THREE weekly deadlines OR if you miss the final deadline, send your check to that organization you hate.

- Finally, write! I promise that if you complete steps one through six, you'll be incredibly focused.

When I took these steps while writing my seventh book, I finished it in sixty-three days. Sixty-three days!

It was the most focused I’ve ever been in my life.

Writing a book is hard work. Setting reasonable consequences make it harder to NOT finish than to finish.

Watch me walk a Wattpad famous writer through this process:

![methods of novel writing Wattpad Famous Author Wanted Coaching. Here's What I Told Him [How to Write a Book Coaching]](https://thewritepractice.com/wp-content/cache/flying-press/mae2iPsg-4k-hqdefault.jpg)

6. Strive for “Good Enough” and Embrace Imperfection

The next few points are all about how to write a good story.

The reason we set a deadline before we consider how to write a story that stands out is because we could spend our entire lives learning how write a great story, but never actually write the actual story (and it’s in the writing process that you learn how to make your story great).

So learn how to make it great between writing sessions, but only good enough for the draft you’re currently writing. If you focus too much on this, it will ruin everything and you’ll never finish.

Writing a perfect novel, a novel like the one you have in your imagination, is an exercise in futility.

First drafts are inevitably horrible. Second drafts are a little better. Third drafts are better still.

But I'd bet none of these drafts approach the perfection that you built up in your head when you first considered your novel idea.

And yet, even if you know that, you’ll still try to write a perfect novel.

So remind yourself constantly, “This first draft doesn’t have to be perfect. It just has to be good enough for now.”

And good enough for now, when you’re starting your first draft, just means you have words on a page that faintly resemble a story.

Writing is an iterative process. The purpose of your first draft is to have something you can improve in your second draft. Don’t overthink. Just do. (I’ll remind you of this later, in case you forget, and if you’re like me, you probably will.)

Ready to look at what makes a good story? Let’s jump into the next few points—but don’t forget your goal: to get your whole book, the complete story, on the page, no matter how messy your first draft reads.

7. Figure Out What Kind of Story You’re Trying to Tell

Now that you have a deadline, you can start to think more deeply about what your protagonist really wants.

A good story focuses primarily on just one core thing that the protagonist wants or needs, and the place where your protagonist’s want or need meets the reader’s expectations dictates your story's genre.

Plot type is a big subject, and for the purposes of this post, we don’t have time to fully explore it (check out my book The Write Structure here ).

But story type is about more than what shelf your book sits on at the bookstore.

The book type gets to the heart, the foundational values, of what your story is about. In my book The Write Structure , I define ten plot types, which correspond to six value scales. I’ll give an abbreviated version below:

External Values (What Your Protagonist Wants)

- Life vs. Death: Action, Adventure

- Life vs. a Fate Worse Than Death: Horror, Thriller, Mystery

- Love vs. Hate: Love, Romance

- Esteem: Performance, Sports

Internal Values (What Your Protagonist Needs)

Internal plot types work slightly different than external plot types. These are essential for your character's transformation from page one to the end and deal with either a character's shift in their black-and-white view, a character's moral compass, or a character's rise or fall in social status.

For more, check out The Write Structure .

The most common internal plot types are bulleted quickly below.

- Maturity/Sophistication vs. Immaturity/Naiveté: Coming of Age

- Good/Sacrifice vs. Evil/Selfishness: Morality, Temptation/Testing

Choosing Your External and Internal Plot Types Will Set You Up for Success

You can mix and match these genres to some extent. For your book to be commercially successful, you must have an external genre.

For your book to be considered more “character driven”—or a story that connects with the reader on a universal level—you should have an internal genre, too. (I highly recommend having both.)

You can also have a subplot. So that’s three genres that you can potentially incorporate into your novel.

For example, you might have an action plot with a love story subplot and a worldview education internal genre. Or a horror plot with a love story subplot and a morality internal genre. There’s a lot of room to maneuver.

Regardless of what you choose, the balance of the three will give your protagonist plenty of obstacles to face as they strive to achieve their goal from beginning to end. (For best results when you go to publish, though, make sure you have an external genre.)

If you want to have solid preparation to write you book, I highly recommend grabbing a copy of The Write Structure .

What two or three values are foundational to your story? Spend some time brainstorming what your book is really about. Even better, use our Write Structure worksheet to get to the heart of your story type.

8. Read Novels and Watch Films That Are Similar to Yours

“The hard truth is that books are made from books.”

I like to remember this quote from Cormac McCarthy when considering what my next novel is really about.

Now that you’ve thought about your novel's plot, it’s time to see how other great writers have pulled off the impossible and crafted a great story from the glimmer of an idea.

You might think, “My story is completely unique. There are no other stories similar to mine.”

If that’s you, then one small word of warning. If there are no books that are similar to yours, maybe there’s a reason for that.

Personally, I’ve read a lot of great books that were a lot of fun to read and were similar to other books. I’ve also read a lot of bad books that were completely unique.

Even precious, unique snowflakes look more or less like other snowflakes.

If you found your content genre in step three, select three to five novels and films that are in the same genre as yours and study them.

Don’t read/watch for pleasure. Instead, try to figure out the conventions, key scenes, and the way the author/filmmaker moves you through the story.

There's great strength in understanding how your story is the same but different.

9. STRUCTURE, STRUCTURE, STRUCTURE!

Those were the three words my college screenwriting professor, a successful Hollywood TV producer, wrote across the blackboard nearly every class. Your creative process doesn't matter without structure.

You can be a pantser , someone who writes by the seat of their pants.

You can be a plotter , someone who needs to have a detailed outline for each of the plot points in their novel.

You can even be a plantser , somewhere in between the two (like most writers, including me).

It doesn’t matter. You still have to know your story structure .

Here are a few important structural elements you’ll want to figure out for your novel before moving forward:

6 Key Moments of Story Structure

There are six required moments in every story, scene, and act. They are:

- Exposition : Introducing the world and the characters.

- Inciting incident : There’s a problem.

- Rising Action/Progressive complications : The problem gets worse, usually due to external conflict.

- Dilemma : The problem gets so bad that the character has no choice but to deal with it. Usually this happens off screen.

- Climax : The character makes their choice and the climax is the action that follows.

- Denouement : The problem is resolved (for now at least).

If you're unfamiliar with these terms, I recommend studying each of them, especially dilemma, which we'll talk about more in a moment. Mastering these will be a huge aid to your writing process.

For your first few scenes, try plotting out each of these six moments, focusing especially on the dilemma.

Better yet, download our story structure worksheet to guide you through the story structure process, from crafting your initial idea through to writing the synopsis.

I've included some more detailed thoughts (and must-knows) about structure briefly below:

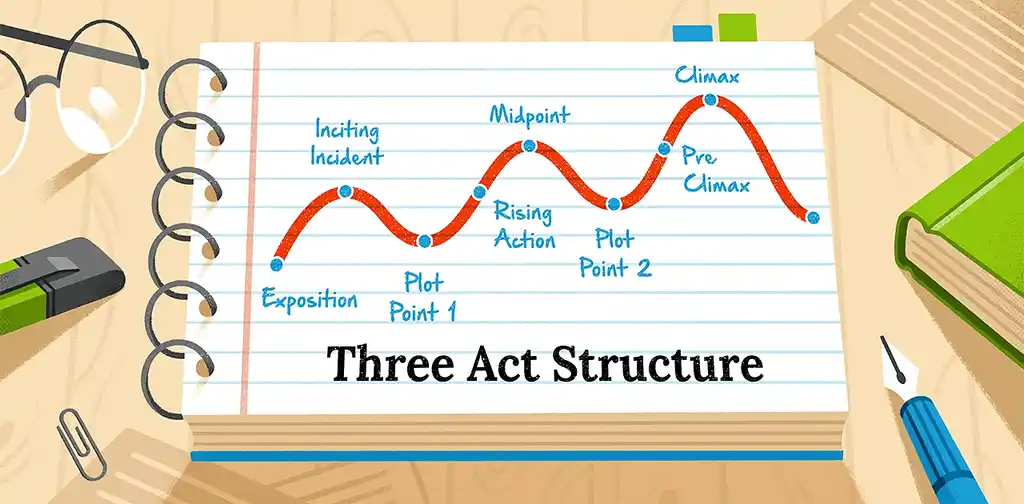

Three Act Structure

The classic writing advice describes the three act structure well:

In the first act, put your character up a tree. In the second act, throw rocks at them. In the third act, bring them down.

Do you wonder whether you should use three act structure or five act structure? (Hint: you probably don't want to use the five act structure. Learn more about this type with our full guide on the five act structure here .)

Note that each of these acts should have the six key moments listed above.

The Dilemma

I mentioned the importance of a character undergoing a crisis, but it bears repeating since, for me, it completely transformed my writing process.

In every act, your protagonist must face an impossible choice. It is THIS choice that creates drama in your story. THIS is how your plot moves forward. If you don’t have a dilemma, if your character doesn’t choose, your scenes won’t work, nor will your acts or story.

In my writing, when I’m working on a first draft, I don’t focus on figuring out all five key moments every time (since I’ve internalized them by now), but I do try to figure out the crisis before I start writing .

I begin with that end in mind, and figure out how I can put the protagonist into a situation where they must make a difficult choice.

One that will have consequences even if they decide to do nothing.

When you do that, your scene works. When you don’t, it falls flat. The protagonist looks like a weak-willed observer of their own life, and ultimately your story will feel boring. Effective character development requires difficult choices.

Find the dilemma every time.

Write out a brief three-act outline with each of the six key moments for each act. It’s okay to leave those moments blank if you don’t know them right now. Fill in what you do know, and come back to it.

Point of View

Point of view, or POV, in a story refers to the narrator’s position in the description of events. There are four types of point of view, but there are only two main options used by most writers:

- Third-person limited point of view is the most common and easiest to use, especially for new writers. In this POV, the characters are referred to in third person (he/she/they) and the narrator has access to the thoughts and feelings to a maximum of one character at a time (and likely one character for the duration of the narrative). You can read more about how to use third-person limited here .

- First-person point of view is also very common and only slightly more difficult. In this POV, the narrator is a character in the story and uses first person pronouns (I/me/mine/we/ours) and has access only to their own thoughts and feelings. This point of view requires an especially strong style, one that shows the narrator's distinct attitude and voice as they tell the story.

The third option is used much less common, though is still found occasionally, especially in older works:

- Third-person omniscient point of view is much more difficult to pull off well and isn't recommended for first time authors. In this POV, the characters are referred to in third-person (he/she/him/her/they/them), but the narrator has access to the thoughts and feelings of any and all characters at the same time. This is a difficult narrative to pull off because of how disorienting it can be for the reader. Readers are placed “in the heads” of so many characters, which can easily destroy the drama of a story because of the lack of mystery.

One final option:

- Second-person point of view is the most difficult to pull off and isn't recommended for most authors. In this POV, the characters are referred to in second person (you/your). This choice is rarely (although not never) found in novels.

Get The Write Structure here »

10. Find the Climactic Moment in Your Novel

Every great novel has a climactic moment that the whole story builds up to—it's the whole reason a reader purchases a book and reads it to the end.

In Moby Dick , it’s the final showdown with the white whale.

In Pride and Prejudice , it’s Lizzie accepting Mr. Darcy’s proposal after discovering the lengths he went to in order to save her family.

In the final Harry Potter novel (spoiler alert!), it’s Harry offering himself up as a sacrifice to Voldemort to destroy the final Horcrux.

To be clear, you don’t have to have your climactic moment all planned out before you start writing your book . (Although knowing this might make writing and finishing your novel easier and more focused.)

But it IS a good idea to know what novels and films similar to yours have done.

For example, if you’re writing a performance story about a violinist, as I am, you need to have some kind of big violin competition at the end of your book.

If you’re writing a police procedural crime novel, you need to have a scene where the detective unmasks the murderer and explains the rationale behind the murder.

Think about the climactic moment your novel builds up before the final showdown at the end. This climactic moment will usually occur in the climax of the second or third act.

If you know this, fill in your outline with the climactic moment, then write out the five key moments of the scene for that moment.

If you don’t know them, just leave them blank. You can always come back to it.

11. Consider the Conventions

Readers are sophisticated. They’ve been taking in stories for years, since they were children, and they have deep expectations for what should be in your story.

That means if you want readers to like your story, you need to meet and even exceed some of those expectations.

Stories do this constantly. We call them conventions, or tropes, and they’re patterns that storytellers throughout history have found make for a good story.

In the romantic comedy (love) genre, for example, there is almost always the sidekick best friend, some kind of love triangle, and a meet cute moment where the two potential lovers meet.

In the mystery genre, the story always begins with a murder, there are one or more red herrings , and there’s a final unveiling of the murder at the end.

Think through the three to five novels and films you read/watched. What conventions and tropes did they have in common?

12. Set Your Intention

You’re almost ready to start writing. Before you do, set your intention.

Researchers have found that when you’re trying to create a new habit, if you imagine where and when you will participate in that habit, you’re far more likely to follow through.

For your writing, imagine where, when, and how much you will write each day. For example, you might imagine that you will write 1,000 words at your favorite coffee shop each afternoon during your lunch break.

As you imagine, picture your location and the writing space clearly in your mind. Watch yourself sitting down to work, typing on your laptop. Imagine your word count tracker going from 999 to 1,002 words.

When it’s time to write , you’ll be ready to go do it.

13. Picture Your Reader

The definition of a story is a narrative meant to entertain, amuse, or instruct. That implies there is someone being entertained, amused, or instructed!

I think it’s helpful to picture one person in your mind as you write (instead of an entire target audience). Then, as you write, you can better understand what would interest, amuse, or instruct them.

By picturing them, you will end up writing better stories.

Create a reader avatar.

Choose someone you know, or make up someone who would love your story. Describe them in terms of demographics and interests. Consider the question, “Why would this reader love my novel?”

When you write, write for them.

14. Build Your Team

Most people think they can write a novel on their own, that they need to stick themselves in some cabin in upstate New York or an attic apartment in Paris and just focus on writing their novel for a few months or decades.

And that’s why most people fail to finish writing a book .

As I’ve studied the lives of great writers, I’ve found that they all had a team. None of them did it all on their own. They all had people who supported and encouraged them as they wrote.

A team can look like:

- An editor with a publishing house

- A writing group

- An author mentor or coach

- An online writing course or community

Whatever you find, if you want to finish your novel, don’t make the mistake of believing you can do it all on your own (or that you have to do it on your own).

Find a writing group. Take an online writing class . Or hire a developmental editor .

Whatever you do, don’t keep trying to do everything by yourself.

15. Plan the Publishing Process

One thing I’ve found is that when successful people take on a task, they think through every part of the process from beginning to end. They create a plan. Their plan might change, but starting with a plan gives them clear focus for what they’re setting out to accomplish.

Most of the steps we’ve been talking about in this post involve planning (writing is coming up next, don’t worry), but in your plan, it’s important to think through things all the way to the end—the publishing and marketing process.

So spend ten or twenty minutes dreaming about how you’ll publish your novel (self-publishing vs. traditional publishing) and how you’ll promote it (to your email list, on social media, via Amazon ads, etc.).

By brainstorming about the publishing and marketing process, you’ll make it much more likely to actually finish your novel because you're eager for (and know what you want to do when you're at) the end.

Have no idea how to get published? Check out our 10-step book publishing and launch guide here .

16. Write (With Low Expectations)

You’ve created a plan. You know what you’re going to write, when you’re going to write it, and how you’re going to write.

Now it’s time to actually write it.

Sit down at the blank page. Take a deep breath. Write your very first chapter.

Don’t forget, your first draft is supposed to be bad.

Write anyway.

17. Trust the Process and Don’t Quit

As I’ve trained writers through the novel writing process in our 100 Day Book Program, inevitably around day sixty, they tell me how hard the process is, how tired they are of their story, how they have a new idea for a novel, and they want to work on that instead.

“Don’t quit,” I tell them. Trust the process. You’re so much closer than you think.

Then, miraculously, two or three weeks later, they’re emailing me to say they’re about to finish their books. They’re so grateful they didn’t quit.

This is the process. This is how it always goes.

Just when you think you’re not going to make it, you’re almost there.

Just when you most want to quit, that’s when you’re closest to a breakthrough.

Trust the process. Don’t quit. You’re going to make it.

Just keep showing up and doing the work (and remember, doing the work means writing imperfectly).

18. Keep Going, Even When It Hurts

Appliances always break when you’re writing a book.

Someone always gets sick making writing nearly impossible (either you or your spouse or all your kids or all of the above).

One writer told us recently a high-speed car chase ended with the car crashing into a building close to her house.

I’m not superstitious, but stuff like this always happens when you’re writing a book.

Expect it. Things will not go according to plan. Major real life problems will occur.

It will be really hard to stay focused for weeks on end.

This is where it’s so important to have a team (step fourteen). When life happens, you’ll need someone to vent to, to encourage you, and to support you.

No matter what, write anyway. This is what separates you from all the aspiring writers out there. You do the work even when it’s hard.

Keep going.

19. Finish Draft One… Then Onward to the Next

I followed this process, and then one day, I realized I’d written the second to last scene. And then the next day, my novel was finished.

It felt kind of anticlimactic.

I had wanted to write a novel for years, more than a decade. I had done it. And it wasn’t as big of a deal as I thought.

Amazing, without question.

But also just normal.

After all, I had been doing this, writing every day for ninety-nine days. Finishing was just another day.

But the journey itself? 100 days for writing a novel? That was amazing.

That was worth it.

And it will be worth it again and again.

Maybe it will be like that for you. You might finish your book and feel amazing and proud and relieved. You might also feel normal. It’s the difference between being an aspiring writer and being a real writer.

Real writers realize the joy is in the work, not in having a finished book .

When you get to this point, I just want to say, “Congratulations!”

You did it.

You finished a book. I’m so excited for you!

But also, as you will know when you get to this point, this is really just the beginning of your journey.

Your book isn’t nearly ready to publish yet.

So celebrate. Throw a party for yourself. Say thank you to all your team members. You finished. You should be proud!

After this celebratory breather, move on to your last step.

20. Next Drafts: Draft Two…Three…Four…Five

This is a novel writing guide, not a novel revising guide (that is coming soon!). But I’ll give you a few pointers on what to do after you write your novel:

- Rest. Take a break. You earned it. Resting also lets you get distance on your book, which you need right now.

- Read without revising. Most people jump right into the proofreading and line editing process. This is the worst thing you could do. Instead, read your novel from beginning to end without making revisions. You can take notes, but the goal for this is to create a plan for your next draft, not fix all your typos and misplaced commas . This step will usually reveal plot holes, character inconsistencies, and other high-level problems.

- Get feedback. Then, share your book with your team: editors and fellow writers (not friends and family yet). Ask for constructive feedback, especially structural feedback, not on typos for now.

- Next, rewrite for structure. Your second draft is all about fixing the structure of your novel. Revisit steps seven through eleven for help.

- Last, polish your prose. Your third (and additional) draft(s) is for fixing typos, line editing, and making your sentences sound nice. Save this for the end, because if you polish too soon, you might have to delete a whole scene that you spent hours rewriting.

Want to know more about what to do next? Check out our guide on what to do AFTER you finish your book here .

Writers’ Best Tips on How to Write a Novel

I’ve also asked the writers I’ve coached for their single tips on how to write a novel. These are from writers in our community who have followed this process and finished novels of their own. Here are their best novel writing tips:

“Get it out of your head and onto the page, because you can’t improve what’s not been written.” Imogen Mann

“What gets scheduled, gets done. Block time in your day to write. Set a time of day, place and duration that you will write 4-7 days/week until it becomes habit. It’s most effective if it’s the same time of day, in the same place. Then set your duration to a number of minutes or a number of words: 60 minutes, 500 words, whatever. Slowly but surely, those words string together into a piece of work!” Stacey Watkins

“Honestly? And nobody paid me for this one—enroll in the 100 Day Book challenge at The Write Practice. I had been writing around in my novel for years and it wasn’t until I took the challenge did I actually write it chapter by chapter from beginning to end in 80,000 words. Of course I now have to revise, revise, revise.” Madeline Slovenz

“I try to write for at least an hour every day. Some days I feel like the creativity flows out of me and others it’s awkward and slow. But yes, my advice is to write for at least one hour every day. It really helps.” Kurt Paulsen

“Be patient, be humble, be forgiving. Patient, because writing a novel well will take longer than you ever imagined. Humble, because being awake to your strengths and your weaknesses is the only way to grow as a writer. And forgiveness, for the days when nothing seems to work. Stay the course, and the reward at the end — whenever that comes — will be priceless. Because it will be all yours.” Erin Halden

“Single best tip I can recommend is the development of a plan. My early writing, historical stories for my world, was done as a pantser. But, when I took the 100 Day Book challenge , one of the steps was to produce an outline. Mine started as the briefest list of chapters. But, as I thought about it, the outline expanded to cover what was happening and who was in it. That lead to a pattern for the chapters, a timeline, and greater detail in the outline. I had always hated outlines, but like Patrick Rothfuss said in one of his interviews, that hatred may have been because of the way it was taught when I was in school (long ago.) I know I will use one for the second book (if I decide to go forward with it.) Just remember the plan is there for your needs. It doesn’t need to be a formal I. A. 1. a. format. It can simply be a set of notecards with general ideas you want to include in your story.” Patrick Macy

“Everybody who writes does so on faith and guts and determination. Just write one line. Just write one scene. Just write one page. And if you write more that day consider yourself fortunate. The more you do, the stronger the writing muscle gets. But don’t do a project; just break things down into small manageable bits.” Joe Hanzlik

“When you’re sending your novel out to beta readers , keep in mind some people‘s feedback may not resonate or be true for your vision of the work. Also, just because you’ve handed off a copy for beta reading doesn’t mean you don’t have control over how people give you feedback. For instance, if you don’t want line editing, ask them not to give paragraph and sentence corrections. Instead, ask for more general feedback on the character arcs, particular scenes in the story, the genre, ideal reader , etc. Be proactive about getting the kind of response you want and need.” B.E. Jackson

“Become your main character. Begin to think and act the way they would.” Valda Dracopoulos

“I write for minimum 3 hours starting 4 a.m. Mind is uncluttered and fresh with ideas. Daily issues and commitment can wait. Make a plan and stick to the basic plan.” R.B. Smith

“Stick to the plan (which includes writing an outline, puttin your butt in the chair and shipping). I’m trying to keep it simple!” Carole Wolf

“Have a spot where you write, get some bum glue, sit and write. I usually have a starting point, a flexible endpoint and the middle works itself out.” Vuyo Ngcakani

“Before I begin, I write down the ten key scenes that must be in the novel. What is the thing that must happen, who is there when it happens, where does it take place. Once I have those key scenes, I begin.” Cathy Ryan

“In my English classes, I was told to ‘show, don’t tell,' which is the most vague rule I’ve ever heard when it comes to writing. Until I saw a post that expanded upon this concept saying to ‘ show emotion, tell feelings …’. Showing emotion will bring the reader closer to the characters, to understand their actions better. But I don’t need to read about how slow she was moving due to tiredness.” Bryan Coulter

“For me, it’s the interaction between all of the characters. It drives almost all of my novels no matter how good or bad the plot may be .” Jonathan Srock

“Rules don’t apply in the first draft; they only apply when you begin to play with it in the second draft.” Victor Paul Scerri

“My best advice to you is: Just Write. No matter if you are not inspired, maybe you are writing how you can’t think of something to write or wrote something that sucks. But just having words written down gets you going and soon you’ll find yourself inspired. You just have to write.” Mony Martinez

“As Joseph Campbell said, “find your bliss.” Tap into a vein of whatever it is that “fills your glass” and take a ride on a stream of happy, joyful verbiage.” Jarrett Wilson

“Show don’t tell is the most cited rule in the history of fiction writing, but if you only show, you won’t get past ch. 1. Learn to master the other forms of narration as well.” Rebecka Jäger

“We’ve all been trained jump when the phone rings, or worse, to continually check in with social media. Good work requires focus, but I’ve had to adopt some hacks to achieve it. 1) Get up an hour before the rest of the household and start writing. Don’t check email, Facebook, Instagram, anything – just start working. 2) Use a timer app, to help keep you honest. I set it for 30 minutes, then it gives me a 5-minute break (when things are really humming, I ignore the breaks altogether). During that time, I don’t allow anything to interrupt me if I can help it. 3) Finally, set a 3-tiered word count goal: Good, Great, Amazing. Good is the number of words you need to generate in order to feel like you’ve accomplished something (1000 words, for example). Great would be a higher number, (say, 2000 words). 3000 words could be Amazing. What I love about this strategy is that it’s forgiving and inspiring at the same time.” Dave Strand

“My advice comes in two parts. First, I think it’s important to breathe life into characters, to give them emotions and personalities and quirks. Make them flawed so that they have plenty of room to grow. Make them feel real to the reader, so when they overcome the obstacles you throw in their way, or they don’t overcome them, the reader feels all the more connected and invested in their journey. Second, I think there’s just something so magical about a scene that transports me, as a reader, to the characters’ world; that allows me to see, feel, smell, and touch what the characters are experiencing. So, the second part of my advice is to describe the character’s experience of their surroundings keeping all of their senses in mind. Don’t stop simply with what they see.” Jennifer Baker

“Start with an outline (it can always be changed), set writing goals and stick to them, write every day, know that your first draft is going to suck and embrace that knowledge, and seek honest feedback. Oh, and celebrate milestones, especially when you type ‘The End’. Take a break from your novel (but don’t stop writing something — short stories, blog posts, articles, etc.) and then dive head-first into draft 2!” Jen Horgan O’Rourke

“I write in fits and spurts of inspiration and insights. Much of my ‘writing’ occurs when I am trying to fall asleep at night or weeding in the garden. I carry my stories and essays in my head, and when I sit down to start writing, I don’t like to ‘turn off the tap.’ My most important principle is that when I write a draft, I put it out of my mind for a few days before coming back to see what it sounds like when I read it aloud.” Gayle Woodson

“My stories almost always start from a single image… someone in a situation, a setting, with or without other people… there is a problem to be solved, a decision to make, some action being taken. Often that first image becomes the central point of the story but sometimes it is simply the kick-off point for something else. Once I’ve ‘seen’ my image clearly I sit down at the computer and start writing. More images appear as I write and the story evolves. Once the rough sketch has developed through a few chapters I may go back and fill in holes and round things out. Sometimes I even sketch a rough map of my setting or the ‘world’ I’m building. With first drafts I never worry about the grammatical and other writing ‘rules.’ Those things get ironed out in the second round.” Karin Weiss

“What it took to get my first novel drafted: the outline of a story idea, sitting in chair, DEADLINES, helpful feedback from the beginning so I could learn along the way.” Joan Cory

“I write a chapter in longhand and then later that day or the next morning type it and revise. The ideas seem to flow from mind to finger to pen to paper.” Al Rutgers

“Getting up early and write for a couple of hours from 6 am is my preferred choice as my mind is uncluttered with daily issues. Stick to the basic plan and learning to ‘show’ and ‘not tell’ has been hard but very beneficial.” Abe Tse

If you're ready to get serious about finishing your novel, I love for you to join us!

And if you want help getting organized and going, I greatly recommend purchasing The Write Planner and/or our 100 Day Book Program .

Frequently Asked Questions

If you're working on your first-ever novel, congratulations! Here are answers to frequently asked questions new (and even experienced) writers often ask me about what it takes to write a book.

How long should a novel be?

First, novel manuscripts are measured in words, not pages. A standard length for a novel is 85,000 words. The sweet number for literary agents is 90,000 words. Science fiction and fantasy tend to be around the 100,000 word range. And mystery and YA tend to be shorter, likely 65,000 words.

Over 120,000 words is usually too long, especially for traditional publishing. Under 60,000 words is a bit short, and might feel incomplete to the reader.

Of course, these are guidelines, not rules.

They exist for a reason, but that doesn’t mean you have to follow them if you have a good reason. For a more complete guide to best word count for novels, check out my guide here .

How long does it take to write a novel?

Each draft can take about the same amount of time as the first draft, or about 100 days. I recommend writing at least three drafts with a few breaks between drafts, which means you can have a finished, published novel in a little less than a year using this process.

Many people have finished novels faster. My friend and bestseller Carlos Cooper finishes four novels a year, and another bestselling author friend Stacy Claflin is working on her sixty-second book (and she’s not close to being sixty-two years old).

If you'd like, you can write faster.

If you take longer breaks between drafts or write more drafts, it might take longer.

Whatever you decide, I don’t recommend taking much longer than 100 days to finish your first draft. After that, you can lose your momentum and it becomes much harder to finish.

That’s It! The Foolproof Template for How to Write a Novel

Writing a novel isn’t easy. But it is possible with the write process (sorry, I had to do it). If you follow each step above, you will finish a novel.

Your novel may not be perfect, but it will be what you need on your road to making it great.

Good luck and happy writing!

Discover The Write Plan Planner »

Which steps of this process do you follow? Which steps are new or challenging for you? Let us know in the comments !

Writing your novel idea in the form of a single-sentence premise is the first step to finishing your novel . So let’s do that today!

Download our premise worksheet. Follow it to construct your single sentence premise.

Then post your premise in the Pro Practice Workshop (and if you’re not a member yet, you can join here ). If you post, please be sure to leave feedback on premises by at least three other writers.

Maybe you'll start finding your writing team right here!

Happy writing!

Join 100 Day Book

Enrollment closes May 14 at midnight!

Joe Bunting

Joe Bunting is an author and the leader of The Write Practice community. He is also the author of the new book Crowdsourcing Paris , a real life adventure story set in France. It was a #1 New Release on Amazon. Follow him on Instagram (@jhbunting).

Want best-seller coaching? Book Joe here.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks

- How to Write a Novel: 20 Tips from a #1 Bestselling Author - […] how to write a novel? If so, you’re not alone. More than 10,000 people search “how to write a…

- Chic Inspiration: What I’m Loving for Spring – ChicZephyr - […] inspiration for outlining and getting the creative juices flowing again on my […]

- 7 Keys To Write the Perfect First Line of a Novel - The Write Practice - […] Ready to write the rest of your novel? Check out our definitive guide, How to Write a Novel: The Complete…

- Word Count: How Many Words In a Novel? - […] Ready to write your novel? Check out our definitive guide, How To Write Write a Novel: The Complete Guide,…

- How a Scene List Can Change Your Novel-Writing Life - […] Ready to write your novel? Check out our definitive guide, How To Write Write a Novel: The Complete Guide,…

- 3 Ways to Start a Novel - […] Ready to write your novel? Check out our definitive guide, How To Write Write a Novel: The Complete Guide,…

- Henry Miller on How to Finish Your Novel - The Write Practice - […] Ready to write your novel? Check out our definitive guide, How To Write Write a Novel: The Complete Guide,…

- How to Transform Raw Inspiration into a Solid Novel Plan - […] Ready to write your novel? Check out our definitive guide, How To Write Write a Novel: The Complete Guide,…

- How To Write A Thriller Novel - […] and suspense.Tweet thisTweetWant to learn how to write a book from start to finish? Check out How to Write…

- 100 Writing Practice Lessons & Exercises - […] writing prompts, doing writing exercises, or finishing writing pieces, like essays, short stories, novels, or books. The best writing…

- Word Count: How Many Words In a Novel? – Books, Literature & Writing - […] Ready to write your novel? Check out our definitive guide, How To Write Write a Novel: The Complete Guide,…

- Will This Help You Master Screenwriting? – Lederto.com Blog - […] of these topics should translate pretty well for authors of novels in all the genres of […]

- 10 Best Creative Writing Prompts - […] prompts in your writing today? Who knows, you might even begin something that becomes your next novel to write…

- Aaron Sorkin MasterClass Review: Will This Help You Master Screenwriting? - HAPPSHOPPERS - […] of these topics should translate pretty well for authors of novels in all the genres of […]

- Aaron Sorkin MasterClass Review: Will This Help You Master Screenwriting? – Top News Rocket - […] of these topics should translate pretty well for authors of novels in all the genres of […]

- Aaron Sorkin MasterClass Review: Will This Help You Master Screenwriting? – RVA News Sites - […] of these topics should translate pretty well for authors of novels in all the genres of […]

- What to Do After Writing a Book: The Do's and Dont's - […] So what is next? This article teaches you what to do after writing a book. […]

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Submit Comment

Join over 450,000 readers who are saying YES to practice. You’ll also get a free copy of our eBook 14 Prompts :

Popular Resources

Book Writing Tips & Guides Creativity & Inspiration Tips Writing Prompts Grammar & Vocab Resources Best Book Writing Software ProWritingAid Review Writing Teacher Resources Publisher Rocket Review Scrivener Review Gifts for Writers

Books By Our Writers