How to Write Limitations of the Study (with examples)

This blog emphasizes the importance of recognizing and effectively writing about limitations in research. It discusses the types of limitations, their significance, and provides guidelines for writing about them, highlighting their role in advancing scholarly research.

Updated on August 24, 2023

No matter how well thought out, every research endeavor encounters challenges. There is simply no way to predict all possible variances throughout the process.

These uncharted boundaries and abrupt constraints are known as limitations in research . Identifying and acknowledging limitations is crucial for conducting rigorous studies. Limitations provide context and shed light on gaps in the prevailing inquiry and literature.

This article explores the importance of recognizing limitations and discusses how to write them effectively. By interpreting limitations in research and considering prevalent examples, we aim to reframe the perception from shameful mistakes to respectable revelations.

What are limitations in research?

In the clearest terms, research limitations are the practical or theoretical shortcomings of a study that are often outside of the researcher’s control . While these weaknesses limit the generalizability of a study’s conclusions, they also present a foundation for future research.

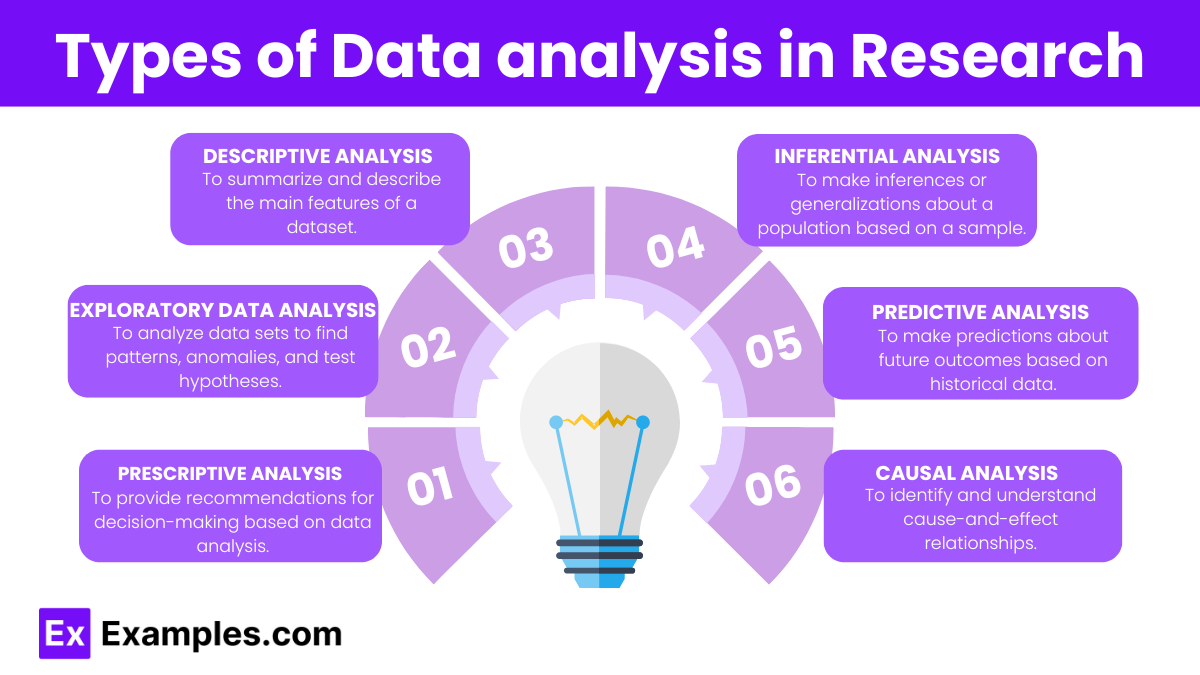

Sometimes limitations arise from tangible circumstances like time and funding constraints, or equipment and participant availability. Other times the rationale is more obscure and buried within the research design. Common types of limitations and their ramifications include:

- Theoretical: limits the scope, depth, or applicability of a study.

- Methodological: limits the quality, quantity, or diversity of the data.

- Empirical: limits the representativeness, validity, or reliability of the data.

- Analytical: limits the accuracy, completeness, or significance of the findings.

- Ethical: limits the access, consent, or confidentiality of the data.

Regardless of how, when, or why they arise, limitations are a natural part of the research process and should never be ignored . Like all other aspects, they are vital in their own purpose.

Why is identifying limitations important?

Whether to seek acceptance or avoid struggle, humans often instinctively hide flaws and mistakes. Merging this thought process into research by attempting to hide limitations, however, is a bad idea. It has the potential to negate the validity of outcomes and damage the reputation of scholars.

By identifying and addressing limitations throughout a project, researchers strengthen their arguments and curtail the chance of peer censure based on overlooked mistakes. Pointing out these flaws shows an understanding of variable limits and a scrupulous research process.

Showing awareness of and taking responsibility for a project’s boundaries and challenges validates the integrity and transparency of a researcher. It further demonstrates the researchers understand the applicable literature and have thoroughly evaluated their chosen research methods.

Presenting limitations also benefits the readers by providing context for research findings. It guides them to interpret the project’s conclusions only within the scope of very specific conditions. By allowing for an appropriate generalization of the findings that is accurately confined by research boundaries and is not too broad, limitations boost a study’s credibility .

Limitations are true assets to the research process. They highlight opportunities for future research. When researchers identify the limitations of their particular approach to a study question, they enable precise transferability and improve chances for reproducibility.

Simply stating a project’s limitations is not adequate for spurring further research, though. To spark the interest of other researchers, these acknowledgements must come with thorough explanations regarding how the limitations affected the current study and how they can potentially be overcome with amended methods.

How to write limitations

Typically, the information about a study’s limitations is situated either at the beginning of the discussion section to provide context for readers or at the conclusion of the discussion section to acknowledge the need for further research. However, it varies depending upon the target journal or publication guidelines.

Don’t hide your limitations

It is also important to not bury a limitation in the body of the paper unless it has a unique connection to a topic in that section. If so, it needs to be reiterated with the other limitations or at the conclusion of the discussion section. Wherever it is included in the manuscript, ensure that the limitations section is prominently positioned and clearly introduced.

While maintaining transparency by disclosing limitations means taking a comprehensive approach, it is not necessary to discuss everything that could have potentially gone wrong during the research study. If there is no commitment to investigation in the introduction, it is unnecessary to consider the issue a limitation to the research. Wholly consider the term ‘limitations’ and ask, “Did it significantly change or limit the possible outcomes?” Then, qualify the occurrence as either a limitation to include in the current manuscript or as an idea to note for other projects.

Writing limitations

Once the limitations are concretely identified and it is decided where they will be included in the paper, researchers are ready for the writing task. Including only what is pertinent, keeping explanations detailed but concise, and employing the following guidelines is key for crafting valuable limitations:

1) Identify and describe the limitations : Clearly introduce the limitation by classifying its form and specifying its origin. For example:

- An unintentional bias encountered during data collection

- An intentional use of unplanned post-hoc data analysis

2) Explain the implications : Describe how the limitation potentially influences the study’s findings and how the validity and generalizability are subsequently impacted. Provide examples and evidence to support claims of the limitations’ effects without making excuses or exaggerating their impact. Overall, be transparent and objective in presenting the limitations, without undermining the significance of the research.

3) Provide alternative approaches for future studies : Offer specific suggestions for potential improvements or avenues for further investigation. Demonstrate a proactive approach by encouraging future research that addresses the identified gaps and, therefore, expands the knowledge base.

Whether presenting limitations as an individual section within the manuscript or as a subtopic in the discussion area, authors should use clear headings and straightforward language to facilitate readability. There is no need to complicate limitations with jargon, computations, or complex datasets.

Examples of common limitations

Limitations are generally grouped into two categories , methodology and research process .

Methodology limitations

Methodology may include limitations due to:

- Sample size

- Lack of available or reliable data

- Lack of prior research studies on the topic

- Measure used to collect the data

- Self-reported data

The researcher is addressing how the large sample size requires a reassessment of the measures used to collect and analyze the data.

Research process limitations

Limitations during the research process may arise from:

- Access to information

- Longitudinal effects

- Cultural and other biases

- Language fluency

- Time constraints

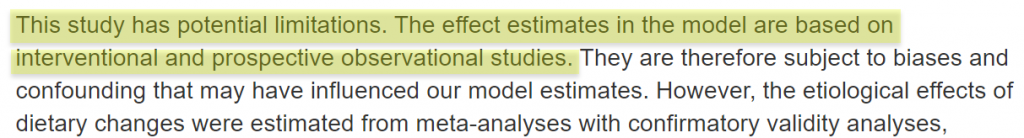

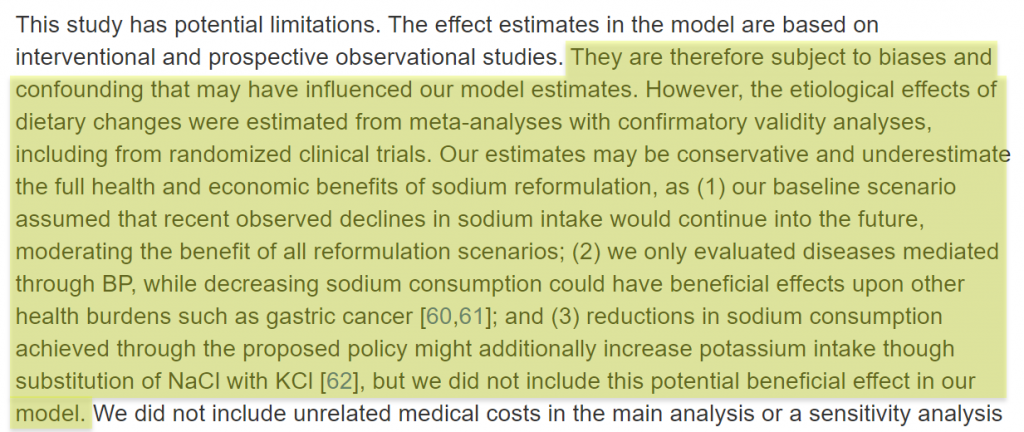

The author is pointing out that the model’s estimates are based on potentially biased observational studies.

Final thoughts

Successfully proving theories and touting great achievements are only two very narrow goals of scholarly research. The true passion and greatest efforts of researchers comes more in the form of confronting assumptions and exploring the obscure.

In many ways, recognizing and sharing the limitations of a research study both allows for and encourages this type of discovery that continuously pushes research forward. By using limitations to provide a transparent account of the project's boundaries and to contextualize the findings, researchers pave the way for even more robust and impactful research in the future.

Charla Viera, MS

See our "Privacy Policy"

Ensure your structure and ideas are consistent and clearly communicated

Pair your Premium Editing with our add-on service Presubmission Review for an overall assessment of your manuscript.

21 Research Limitations Examples

Chris Drew (PhD)

Dr. Chris Drew is the founder of the Helpful Professor. He holds a PhD in education and has published over 20 articles in scholarly journals. He is the former editor of the Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education. [Image Descriptor: Photo of Chris]

Learn about our Editorial Process

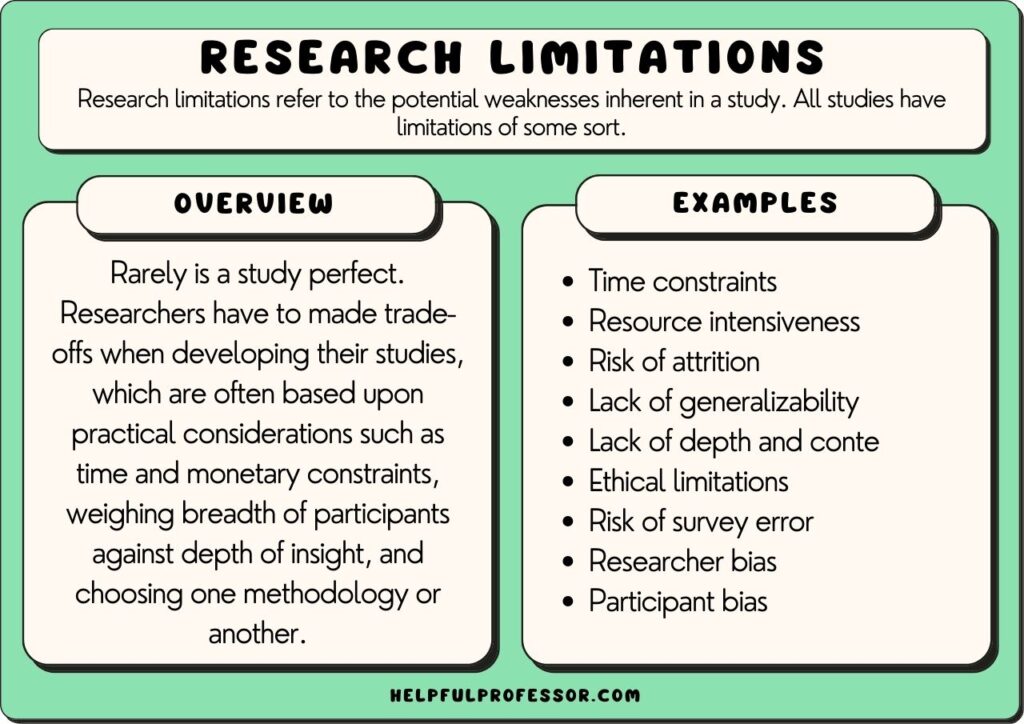

Research limitations refer to the potential weaknesses inherent in a study. All studies have limitations of some sort, meaning declaring limitations doesn’t necessarily need to be a bad thing, so long as your declaration of limitations is well thought-out and explained.

Rarely is a study perfect. Researchers have to make trade-offs when developing their studies, which are often based upon practical considerations such as time and monetary constraints, weighing the breadth of participants against the depth of insight, and choosing one methodology or another.

In research, studies can have limitations such as limited scope, researcher subjectivity, and lack of available research tools.

Acknowledging the limitations of your study should be seen as a strength. It demonstrates your willingness for transparency, humility, and submission to the scientific method and can bolster the integrity of the study. It can also inform future research direction.

Typically, scholars will explore the limitations of their study in either their methodology section, their conclusion section, or both.

Research Limitations Examples

Qualitative and quantitative research offer different perspectives and methods in exploring phenomena, each with its own strengths and limitations. So, I’ve split the limitations examples sections into qualitative and quantitative below.

Qualitative Research Limitations

Qualitative research seeks to understand phenomena in-depth and in context. It focuses on the ‘why’ and ‘how’ questions.

It’s often used to explore new or complex issues, and it provides rich, detailed insights into participants’ experiences, behaviors, and attitudes. However, these strengths also create certain limitations, as explained below.

1. Subjectivity

Qualitative research often requires the researcher to interpret subjective data. One researcher may examine a text and identify different themes or concepts as more dominant than others.

Close qualitative readings of texts are necessarily subjective – and while this may be a limitation, qualitative researchers argue this is the best way to deeply understand everything in context.

Suggested Solution and Response: To minimize subjectivity bias, you could consider cross-checking your own readings of themes and data against other scholars’ readings and interpretations. This may involve giving the raw data to a supervisor or colleague and asking them to code the data separately, then coming together to compare and contrast results.

2. Researcher Bias

The concept of researcher bias is related to, but slightly different from, subjectivity.

Researcher bias refers to the perspectives and opinions you bring with you when doing your research.

For example, a researcher who is explicitly of a certain philosophical or political persuasion may bring that persuasion to bear when interpreting data.

In many scholarly traditions, we will attempt to minimize researcher bias through the utilization of clear procedures that are set out in advance or through the use of statistical analysis tools.

However, in other traditions, such as in postmodern feminist research , declaration of bias is expected, and acknowledgment of bias is seen as a positive because, in those traditions, it is believed that bias cannot be eliminated from research, so instead, it is a matter of integrity to present it upfront.

Suggested Solution and Response: Acknowledge the potential for researcher bias and, depending on your theoretical framework , accept this, or identify procedures you have taken to seek a closer approximation to objectivity in your coding and analysis.

3. Generalizability

If you’re struggling to find a limitation to discuss in your own qualitative research study, then this one is for you: all qualitative research, of all persuasions and perspectives, cannot be generalized.

This is a core feature that sets qualitative data and quantitative data apart.

The point of qualitative data is to select case studies and similarly small corpora and dig deep through in-depth analysis and thick description of data.

Often, this will also mean that you have a non-randomized sample size.

While this is a positive – you’re going to get some really deep, contextualized, interesting insights – it also means that the findings may not be generalizable to a larger population that may not be representative of the small group of people in your study.

Suggested Solution and Response: Suggest future studies that take a quantitative approach to the question.

4. The Hawthorne Effect

The Hawthorne effect refers to the phenomenon where research participants change their ‘observed behavior’ when they’re aware that they are being observed.

This effect was first identified by Elton Mayo who conducted studies of the effects of various factors ton workers’ productivity. He noticed that no matter what he did – turning up the lights, turning down the lights, etc. – there was an increase in worker outputs compared to prior to the study taking place.

Mayo realized that the mere act of observing the workers made them work harder – his observation was what was changing behavior.

So, if you’re looking for a potential limitation to name for your observational research study , highlight the possible impact of the Hawthorne effect (and how you could reduce your footprint or visibility in order to decrease its likelihood).

Suggested Solution and Response: Highlight ways you have attempted to reduce your footprint while in the field, and guarantee anonymity to your research participants.

5. Replicability

Quantitative research has a great benefit in that the studies are replicable – a researcher can get a similar sample size, duplicate the variables, and re-test a study. But you can’t do that in qualitative research.

Qualitative research relies heavily on context – a specific case study or specific variables that make a certain instance worthy of analysis. As a result, it’s often difficult to re-enter the same setting with the same variables and repeat the study.

Furthermore, the individual researcher’s interpretation is more influential in qualitative research, meaning even if a new researcher enters an environment and makes observations, their observations may be different because subjectivity comes into play much more. This doesn’t make the research bad necessarily (great insights can be made in qualitative research), but it certainly does demonstrate a weakness of qualitative research.

6. Limited Scope

“Limited scope” is perhaps one of the most common limitations listed by researchers – and while this is often a catch-all way of saying, “well, I’m not studying that in this study”, it’s also a valid point.

No study can explore everything related to a topic. At some point, we have to make decisions about what’s included in the study and what is excluded from the study.

So, you could say that a limitation of your study is that it doesn’t look at an extra variable or concept that’s certainly worthy of study but will have to be explored in your next project because this project has a clearly and narrowly defined goal.

Suggested Solution and Response: Be clear about what’s in and out of the study when writing your research question.

7. Time Constraints

This is also a catch-all claim you can make about your research project: that you would have included more people in the study, looked at more variables, and so on. But you’ve got to submit this thing by the end of next semester! You’ve got time constraints.

And time constraints are a recognized reality in all research.

But this means you’ll need to explain how time has limited your decisions. As with “limited scope”, this may mean that you had to study a smaller group of subjects, limit the amount of time you spent in the field, and so forth.

Suggested Solution and Response: Suggest future studies that will build on your current work, possibly as a PhD project.

8. Resource Intensiveness

Qualitative research can be expensive due to the cost of transcription, the involvement of trained researchers, and potential travel for interviews or observations.

So, resource intensiveness is similar to the time constraints concept. If you don’t have the funds, you have to make decisions about which tools to use, which statistical software to employ, and how many research assistants you can dedicate to the study.

Suggested Solution and Response: Suggest future studies that will gain more funding on the back of this ‘ exploratory study ‘.

9. Coding Difficulties

Data analysis in qualitative research often involves coding, which can be subjective and complex, especially when dealing with ambiguous or contradicting data.

After naming this as a limitation in your research, it’s important to explain how you’ve attempted to address this. Some ways to ‘limit the limitation’ include:

- Triangulation: Have 2 other researchers code the data as well and cross-check your results with theirs to identify outliers that may need to be re-examined, debated with the other researchers, or removed altogether.

- Procedure: Use a clear coding procedure to demonstrate reliability in your coding process. I personally use the thematic network analysis method outlined in this academic article by Attride-Stirling (2001).

Suggested Solution and Response: Triangulate your coding findings with colleagues, and follow a thematic network analysis procedure.

10. Risk of Non-Responsiveness

There is always a risk in research that research participants will be unwilling or uncomfortable sharing their genuine thoughts and feelings in the study.

This is particularly true when you’re conducting research on sensitive topics, politicized topics, or topics where the participant is expressing vulnerability .

This is similar to the Hawthorne effect (aka participant bias), where participants change their behaviors in your presence; but it goes a step further, where participants actively hide their true thoughts and feelings from you.

Suggested Solution and Response: One way to manage this is to try to include a wider group of people with the expectation that there will be non-responsiveness from some participants.

11. Risk of Attrition

Attrition refers to the process of losing research participants throughout the study.

This occurs most commonly in longitudinal studies , where a researcher must return to conduct their analysis over spaced periods of time, often over a period of years.

Things happen to people over time – they move overseas, their life experiences change, they get sick, change their minds, and even die. The more time that passes, the greater the risk of attrition.

Suggested Solution and Response: One way to manage this is to try to include a wider group of people with the expectation that there will be attrition over time.

12. Difficulty in Maintaining Confidentiality and Anonymity

Given the detailed nature of qualitative data , ensuring participant anonymity can be challenging.

If you have a sensitive topic in a specific case study, even anonymizing research participants sometimes isn’t enough. People might be able to induce who you’re talking about.

Sometimes, this will mean you have to exclude some interesting data that you collected from your final report. Confidentiality and anonymity come before your findings in research ethics – and this is a necessary limiting factor.

Suggested Solution and Response: Highlight the efforts you have taken to anonymize data, and accept that confidentiality and accountability place extremely important constraints on academic research.

13. Difficulty in Finding Research Participants

A study that looks at a very specific phenomenon or even a specific set of cases within a phenomenon means that the pool of potential research participants can be very low.

Compile on top of this the fact that many people you approach may choose not to participate, and you could end up with a very small corpus of subjects to explore. This may limit your ability to make complete findings, even in a quantitative sense.

You may need to therefore limit your research question and objectives to something more realistic.

Suggested Solution and Response: Highlight that this is going to limit the study’s generalizability significantly.

14. Ethical Limitations

Ethical limitations refer to the things you cannot do based on ethical concerns identified either by yourself or your institution’s ethics review board.

This might include threats to the physical or psychological well-being of your research subjects, the potential of releasing data that could harm a person’s reputation, and so on.

Furthermore, even if your study follows all expected standards of ethics, you still, as an ethical researcher, need to allow a research participant to pull out at any point in time, after which you cannot use their data, which demonstrates an overlap between ethical constraints and participant attrition.

Suggested Solution and Response: Highlight that these ethical limitations are inevitable but important to sustain the integrity of the research.

For more on Qualitative Research, Explore my Qualitative Research Guide

Quantitative Research Limitations

Quantitative research focuses on quantifiable data and statistical, mathematical, or computational techniques. It’s often used to test hypotheses, assess relationships and causality, and generalize findings across larger populations.

Quantitative research is widely respected for its ability to provide reliable, measurable, and generalizable data (if done well!). Its structured methodology has strengths over qualitative research, such as the fact it allows for replication of the study, which underpins the validity of the research.

However, this approach is not without it limitations, explained below.

1. Over-Simplification

Quantitative research is powerful because it allows you to measure and analyze data in a systematic and standardized way. However, one of its limitations is that it can sometimes simplify complex phenomena or situations.

In other words, it might miss the subtleties or nuances of the research subject.

For example, if you’re studying why people choose a particular diet, a quantitative study might identify factors like age, income, or health status. But it might miss other aspects, such as cultural influences or personal beliefs, that can also significantly impact dietary choices.

When writing about this limitation, you can say that your quantitative approach, while providing precise measurements and comparisons, may not capture the full complexity of your subjects of study.

Suggested Solution and Response: Suggest a follow-up case study using the same research participants in order to gain additional context and depth.

2. Lack of Context

Another potential issue with quantitative research is that it often focuses on numbers and statistics at the expense of context or qualitative information.

Let’s say you’re studying the effect of classroom size on student performance. You might find that students in smaller classes generally perform better. However, this doesn’t take into account other variables, like teaching style , student motivation, or family support.

When describing this limitation, you might say, “Although our research provides important insights into the relationship between class size and student performance, it does not incorporate the impact of other potentially influential variables. Future research could benefit from a mixed-methods approach that combines quantitative analysis with qualitative insights.”

3. Applicability to Real-World Settings

Oftentimes, experimental research takes place in controlled environments to limit the influence of outside factors.

This control is great for isolation and understanding the specific phenomenon but can limit the applicability or “external validity” of the research to real-world settings.

For example, if you conduct a lab experiment to see how sleep deprivation impacts cognitive performance, the sterile, controlled lab environment might not reflect real-world conditions where people are dealing with multiple stressors.

Therefore, when explaining the limitations of your quantitative study in your methodology section, you could state:

“While our findings provide valuable information about [topic], the controlled conditions of the experiment may not accurately represent real-world scenarios where extraneous variables will exist. As such, the direct applicability of our results to broader contexts may be limited.”

Suggested Solution and Response: Suggest future studies that will engage in real-world observational research, such as ethnographic research.

4. Limited Flexibility

Once a quantitative study is underway, it can be challenging to make changes to it. This is because, unlike in grounded research, you’re putting in place your study in advance, and you can’t make changes part-way through.

Your study design, data collection methods, and analysis techniques need to be decided upon before you start collecting data.

For example, if you are conducting a survey on the impact of social media on teenage mental health, and halfway through, you realize that you should have included a question about their screen time, it’s generally too late to add it.

When discussing this limitation, you could write something like, “The structured nature of our quantitative approach allows for consistent data collection and analysis but also limits our flexibility to adapt and modify the research process in response to emerging insights and ideas.”

Suggested Solution and Response: Suggest future studies that will use mixed-methods or qualitative research methods to gain additional depth of insight.

5. Risk of Survey Error

Surveys are a common tool in quantitative research, but they carry risks of error.

There can be measurement errors (if a question is misunderstood), coverage errors (if some groups aren’t adequately represented), non-response errors (if certain people don’t respond), and sampling errors (if your sample isn’t representative of the population).

For instance, if you’re surveying college students about their study habits , but only daytime students respond because you conduct the survey during the day, your results will be skewed.

In discussing this limitation, you might say, “Despite our best efforts to develop a comprehensive survey, there remains a risk of survey error, including measurement, coverage, non-response, and sampling errors. These could potentially impact the reliability and generalizability of our findings.”

Suggested Solution and Response: Suggest future studies that will use other survey tools to compare and contrast results.

6. Limited Ability to Probe Answers

With quantitative research, you typically can’t ask follow-up questions or delve deeper into participants’ responses like you could in a qualitative interview.

For instance, imagine you are surveying 500 students about study habits in a questionnaire. A respondent might indicate that they study for two hours each night. You might want to follow up by asking them to elaborate on what those study sessions involve or how effective they feel their habits are.

However, quantitative research generally disallows this in the way a qualitative semi-structured interview could.

When discussing this limitation, you might write, “Given the structured nature of our survey, our ability to probe deeper into individual responses is limited. This means we may not fully understand the context or reasoning behind the responses, potentially limiting the depth of our findings.”

Suggested Solution and Response: Suggest future studies that engage in mixed-method or qualitative methodologies to address the issue from another angle.

7. Reliance on Instruments for Data Collection

In quantitative research, the collection of data heavily relies on instruments like questionnaires, surveys, or machines.

The limitation here is that the data you get is only as good as the instrument you’re using. If the instrument isn’t designed or calibrated well, your data can be flawed.

For instance, if you’re using a questionnaire to study customer satisfaction and the questions are vague, confusing, or biased, the responses may not accurately reflect the customers’ true feelings.

When discussing this limitation, you could say, “Our study depends on the use of questionnaires for data collection. Although we have put significant effort into designing and testing the instrument, it’s possible that inaccuracies or misunderstandings could potentially affect the validity of the data collected.”

Suggested Solution and Response: Suggest future studies that will use different instruments but examine the same variables to triangulate results.

8. Time and Resource Constraints (Specific to Quantitative Research)

Quantitative research can be time-consuming and resource-intensive, especially when dealing with large samples.

It often involves systematic sampling, rigorous design, and sometimes complex statistical analysis.

If resources and time are limited, it can restrict the scale of your research, the techniques you can employ, or the extent of your data analysis.

For example, you may want to conduct a nationwide survey on public opinion about a certain policy. However, due to limited resources, you might only be able to survey people in one city.

When writing about this limitation, you could say, “Given the scope of our research and the resources available, we are limited to conducting our survey within one city, which may not fully represent the nationwide public opinion. Hence, the generalizability of the results may be limited.”

Suggested Solution and Response: Suggest future studies that will have more funding or longer timeframes.

How to Discuss Your Research Limitations

1. in your research proposal and methodology section.

In the research proposal, which will become the methodology section of your dissertation, I would recommend taking the four following steps, in order:

- Be Explicit about your Scope – If you limit the scope of your study in your research question, aims, and objectives, then you can set yourself up well later in the methodology to say that certain questions are “outside the scope of the study.” For example, you may identify the fact that the study doesn’t address a certain variable, but you can follow up by stating that the research question is specifically focused on the variable that you are examining, so this limitation would need to be looked at in future studies.

- Acknowledge the Limitation – Acknowledging the limitations of your study demonstrates reflexivity and humility and can make your research more reliable and valid. It also pre-empts questions the people grading your paper may have, so instead of them down-grading you for your limitations; they will congratulate you on explaining the limitations and how you have addressed them!

- Explain your Decisions – You may have chosen your approach (despite its limitations) for a very specific reason. This might be because your approach remains, on balance, the best one to answer your research question. Or, it might be because of time and monetary constraints that are outside of your control.

- Highlight the Strengths of your Approach – Conclude your limitations section by strongly demonstrating that, despite limitations, you’ve worked hard to minimize the effects of the limitations and that you have chosen your specific approach and methodology because it’s also got some terrific strengths. Name the strengths.

Overall, you’ll want to acknowledge your own limitations but also explain that the limitations don’t detract from the value of your study as it stands.

2. In the Conclusion Section or Chapter

In the conclusion of your study, it is generally expected that you return to a discussion of the study’s limitations. Here, I recommend the following steps:

- Acknowledge issues faced – After completing your study, you will be increasingly aware of issues you may have faced that, if you re-did the study, you may have addressed earlier in order to avoid those issues. Acknowledge these issues as limitations, and frame them as recommendations for subsequent studies.

- Suggest further research – Scholarly research aims to fill gaps in the current literature and knowledge. Having established your expertise through your study, suggest lines of inquiry for future researchers. You could state that your study had certain limitations, and “future studies” can address those limitations.

- Suggest a mixed methods approach – Qualitative and quantitative research each have pros and cons. So, note those ‘cons’ of your approach, then say the next study should approach the topic using the opposite methodology or could approach it using a mixed-methods approach that could achieve the benefits of quantitative studies with the nuanced insights of associated qualitative insights as part of an in-study case-study.

Overall, be clear about both your limitations and how those limitations can inform future studies.

In sum, each type of research method has its own strengths and limitations. Qualitative research excels in exploring depth, context, and complexity, while quantitative research excels in examining breadth, generalizability, and quantifiable measures. Despite their individual limitations, each method contributes unique and valuable insights, and researchers often use them together to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the phenomenon being studied.

Attride-Stirling, J. (2001). Thematic networks: an analytic tool for qualitative research. Qualitative research , 1 (3), 385-405. ( Source )

Atkinson, P., Delamont, S., Cernat, A., Sakshaug, J., & Williams, R. A. (2021). SAGE research methods foundations . London: Sage Publications.

Clark, T., Foster, L., Bryman, A., & Sloan, L. (2021). Bryman’s social research methods . Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Köhler, T., Smith, A., & Bhakoo, V. (2022). Templates in qualitative research methods: Origins, limitations, and new directions. Organizational Research Methods , 25 (2), 183-210. ( Source )

Lenger, A. (2019). The rejection of qualitative research methods in economics. Journal of Economic Issues , 53 (4), 946-965. ( Source )

Taherdoost, H. (2022). What are different research approaches? Comprehensive review of qualitative, quantitative, and mixed method research, their applications, types, and limitations. Journal of Management Science & Engineering Research , 5 (1), 53-63. ( Source )

Walliman, N. (2021). Research methods: The basics . New York: Routledge.

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 101 Class Group Name Ideas (for School Students)

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 19 Top Cognitive Psychology Theories (Explained)

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 119 Bloom’s Taxonomy Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ All 6 Levels of Understanding (on Bloom’s Taxonomy)

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

- USC Libraries

- Research Guides

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper

- Limitations of the Study

- Purpose of Guide

- Design Flaws to Avoid

- Independent and Dependent Variables

- Glossary of Research Terms

- Reading Research Effectively

- Narrowing a Topic Idea

- Broadening a Topic Idea

- Extending the Timeliness of a Topic Idea

- Academic Writing Style

- Applying Critical Thinking

- Choosing a Title

- Making an Outline

- Paragraph Development

- Research Process Video Series

- Executive Summary

- The C.A.R.S. Model

- Background Information

- The Research Problem/Question

- Theoretical Framework

- Citation Tracking

- Content Alert Services

- Evaluating Sources

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

- Tiertiary Sources

- Scholarly vs. Popular Publications

- Qualitative Methods

- Quantitative Methods

- Insiderness

- Using Non-Textual Elements

- Common Grammar Mistakes

- Writing Concisely

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Footnotes or Endnotes?

- Further Readings

- Generative AI and Writing

- USC Libraries Tutorials and Other Guides

- Bibliography

The limitations of the study are those characteristics of design or methodology that impacted or influenced the interpretation of the findings from your research. Study limitations are the constraints placed on the ability to generalize from the results, to further describe applications to practice, and/or related to the utility of findings that are the result of the ways in which you initially chose to design the study or the method used to establish internal and external validity or the result of unanticipated challenges that emerged during the study.

Price, James H. and Judy Murnan. “Research Limitations and the Necessity of Reporting Them.” American Journal of Health Education 35 (2004): 66-67; Theofanidis, Dimitrios and Antigoni Fountouki. "Limitations and Delimitations in the Research Process." Perioperative Nursing 7 (September-December 2018): 155-163. .

Importance of...

Always acknowledge a study's limitations. It is far better that you identify and acknowledge your study’s limitations than to have them pointed out by your professor and have your grade lowered because you appeared to have ignored them or didn't realize they existed.

Keep in mind that acknowledgment of a study's limitations is an opportunity to make suggestions for further research. If you do connect your study's limitations to suggestions for further research, be sure to explain the ways in which these unanswered questions may become more focused because of your study.

Acknowledgment of a study's limitations also provides you with opportunities to demonstrate that you have thought critically about the research problem, understood the relevant literature published about it, and correctly assessed the methods chosen for studying the problem. A key objective of the research process is not only discovering new knowledge but also to confront assumptions and explore what we don't know.

Claiming limitations is a subjective process because you must evaluate the impact of those limitations . Don't just list key weaknesses and the magnitude of a study's limitations. To do so diminishes the validity of your research because it leaves the reader wondering whether, or in what ways, limitation(s) in your study may have impacted the results and conclusions. Limitations require a critical, overall appraisal and interpretation of their impact. You should answer the question: do these problems with errors, methods, validity, etc. eventually matter and, if so, to what extent?

Price, James H. and Judy Murnan. “Research Limitations and the Necessity of Reporting Them.” American Journal of Health Education 35 (2004): 66-67; Structure: How to Structure the Research Limitations Section of Your Dissertation. Dissertations and Theses: An Online Textbook. Laerd.com.

Descriptions of Possible Limitations

All studies have limitations . However, it is important that you restrict your discussion to limitations related to the research problem under investigation. For example, if a meta-analysis of existing literature is not a stated purpose of your research, it should not be discussed as a limitation. Do not apologize for not addressing issues that you did not promise to investigate in the introduction of your paper.

Here are examples of limitations related to methodology and the research process you may need to describe and discuss how they possibly impacted your results. Note that descriptions of limitations should be stated in the past tense because they were discovered after you completed your research.

Possible Methodological Limitations

- Sample size -- the number of the units of analysis you use in your study is dictated by the type of research problem you are investigating. Note that, if your sample size is too small, it will be difficult to find significant relationships from the data, as statistical tests normally require a larger sample size to ensure a representative distribution of the population and to be considered representative of groups of people to whom results will be generalized or transferred. Note that sample size is generally less relevant in qualitative research if explained in the context of the research problem.

- Lack of available and/or reliable data -- a lack of data or of reliable data will likely require you to limit the scope of your analysis, the size of your sample, or it can be a significant obstacle in finding a trend and a meaningful relationship. You need to not only describe these limitations but provide cogent reasons why you believe data is missing or is unreliable. However, don’t just throw up your hands in frustration; use this as an opportunity to describe a need for future research based on designing a different method for gathering data.

- Lack of prior research studies on the topic -- citing prior research studies forms the basis of your literature review and helps lay a foundation for understanding the research problem you are investigating. Depending on the currency or scope of your research topic, there may be little, if any, prior research on your topic. Before assuming this to be true, though, consult with a librarian! In cases when a librarian has confirmed that there is little or no prior research, you may be required to develop an entirely new research typology [for example, using an exploratory rather than an explanatory research design ]. Note again that discovering a limitation can serve as an important opportunity to identify new gaps in the literature and to describe the need for further research.

- Measure used to collect the data -- sometimes it is the case that, after completing your interpretation of the findings, you discover that the way in which you gathered data inhibited your ability to conduct a thorough analysis of the results. For example, you regret not including a specific question in a survey that, in retrospect, could have helped address a particular issue that emerged later in the study. Acknowledge the deficiency by stating a need for future researchers to revise the specific method for gathering data.

- Self-reported data -- whether you are relying on pre-existing data or you are conducting a qualitative research study and gathering the data yourself, self-reported data is limited by the fact that it rarely can be independently verified. In other words, you have to the accuracy of what people say, whether in interviews, focus groups, or on questionnaires, at face value. However, self-reported data can contain several potential sources of bias that you should be alert to and note as limitations. These biases become apparent if they are incongruent with data from other sources. These are: (1) selective memory [remembering or not remembering experiences or events that occurred at some point in the past]; (2) telescoping [recalling events that occurred at one time as if they occurred at another time]; (3) attribution [the act of attributing positive events and outcomes to one's own agency, but attributing negative events and outcomes to external forces]; and, (4) exaggeration [the act of representing outcomes or embellishing events as more significant than is actually suggested from other data].

Possible Limitations of the Researcher

- Access -- if your study depends on having access to people, organizations, data, or documents and, for whatever reason, access is denied or limited in some way, the reasons for this needs to be described. Also, include an explanation why being denied or limited access did not prevent you from following through on your study.

- Longitudinal effects -- unlike your professor, who can literally devote years [even a lifetime] to studying a single topic, the time available to investigate a research problem and to measure change or stability over time is constrained by the due date of your assignment. Be sure to choose a research problem that does not require an excessive amount of time to complete the literature review, apply the methodology, and gather and interpret the results. If you're unsure whether you can complete your research within the confines of the assignment's due date, talk to your professor.

- Cultural and other type of bias -- we all have biases, whether we are conscience of them or not. Bias is when a person, place, event, or thing is viewed or shown in a consistently inaccurate way. Bias is usually negative, though one can have a positive bias as well, especially if that bias reflects your reliance on research that only support your hypothesis. When proof-reading your paper, be especially critical in reviewing how you have stated a problem, selected the data to be studied, what may have been omitted, the manner in which you have ordered events, people, or places, how you have chosen to represent a person, place, or thing, to name a phenomenon, or to use possible words with a positive or negative connotation. NOTE : If you detect bias in prior research, it must be acknowledged and you should explain what measures were taken to avoid perpetuating that bias. For example, if a previous study only used boys to examine how music education supports effective math skills, describe how your research expands the study to include girls.

- Fluency in a language -- if your research focuses , for example, on measuring the perceived value of after-school tutoring among Mexican-American ESL [English as a Second Language] students and you are not fluent in Spanish, you are limited in being able to read and interpret Spanish language research studies on the topic or to speak with these students in their primary language. This deficiency should be acknowledged.

Aguinis, Hermam and Jeffrey R. Edwards. “Methodological Wishes for the Next Decade and How to Make Wishes Come True.” Journal of Management Studies 51 (January 2014): 143-174; Brutus, Stéphane et al. "Self-Reported Limitations and Future Directions in Scholarly Reports: Analysis and Recommendations." Journal of Management 39 (January 2013): 48-75; Senunyeme, Emmanuel K. Business Research Methods. Powerpoint Presentation. Regent University of Science and Technology; ter Riet, Gerben et al. “All That Glitters Isn't Gold: A Survey on Acknowledgment of Limitations in Biomedical Studies.” PLOS One 8 (November 2013): 1-6.

Structure and Writing Style

Information about the limitations of your study are generally placed either at the beginning of the discussion section of your paper so the reader knows and understands the limitations before reading the rest of your analysis of the findings, or, the limitations are outlined at the conclusion of the discussion section as an acknowledgement of the need for further study. Statements about a study's limitations should not be buried in the body [middle] of the discussion section unless a limitation is specific to something covered in that part of the paper. If this is the case, though, the limitation should be reiterated at the conclusion of the section.

If you determine that your study is seriously flawed due to important limitations , such as, an inability to acquire critical data, consider reframing it as an exploratory study intended to lay the groundwork for a more complete research study in the future. Be sure, though, to specifically explain the ways that these flaws can be successfully overcome in a new study.

But, do not use this as an excuse for not developing a thorough research paper! Review the tab in this guide for developing a research topic . If serious limitations exist, it generally indicates a likelihood that your research problem is too narrowly defined or that the issue or event under study is too recent and, thus, very little research has been written about it. If serious limitations do emerge, consult with your professor about possible ways to overcome them or how to revise your study.

When discussing the limitations of your research, be sure to:

- Describe each limitation in detailed but concise terms;

- Explain why each limitation exists;

- Provide the reasons why each limitation could not be overcome using the method(s) chosen to acquire or gather the data [cite to other studies that had similar problems when possible];

- Assess the impact of each limitation in relation to the overall findings and conclusions of your study; and,

- If appropriate, describe how these limitations could point to the need for further research.

Remember that the method you chose may be the source of a significant limitation that has emerged during your interpretation of the results [for example, you didn't interview a group of people that you later wish you had]. If this is the case, don't panic. Acknowledge it, and explain how applying a different or more robust methodology might address the research problem more effectively in a future study. A underlying goal of scholarly research is not only to show what works, but to demonstrate what doesn't work or what needs further clarification.

Aguinis, Hermam and Jeffrey R. Edwards. “Methodological Wishes for the Next Decade and How to Make Wishes Come True.” Journal of Management Studies 51 (January 2014): 143-174; Brutus, Stéphane et al. "Self-Reported Limitations and Future Directions in Scholarly Reports: Analysis and Recommendations." Journal of Management 39 (January 2013): 48-75; Ioannidis, John P.A. "Limitations are not Properly Acknowledged in the Scientific Literature." Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 60 (2007): 324-329; Pasek, Josh. Writing the Empirical Social Science Research Paper: A Guide for the Perplexed. January 24, 2012. Academia.edu; Structure: How to Structure the Research Limitations Section of Your Dissertation. Dissertations and Theses: An Online Textbook. Laerd.com; What Is an Academic Paper? Institute for Writing Rhetoric. Dartmouth College; Writing the Experimental Report: Methods, Results, and Discussion. The Writing Lab and The OWL. Purdue University.

Writing Tip

Don't Inflate the Importance of Your Findings!

After all the hard work and long hours devoted to writing your research paper, it is easy to get carried away with attributing unwarranted importance to what you’ve done. We all want our academic work to be viewed as excellent and worthy of a good grade, but it is important that you understand and openly acknowledge the limitations of your study. Inflating the importance of your study's findings could be perceived by your readers as an attempt hide its flaws or encourage a biased interpretation of the results. A small measure of humility goes a long way!

Another Writing Tip

Negative Results are Not a Limitation!

Negative evidence refers to findings that unexpectedly challenge rather than support your hypothesis. If you didn't get the results you anticipated, it may mean your hypothesis was incorrect and needs to be reformulated. Or, perhaps you have stumbled onto something unexpected that warrants further study. Moreover, the absence of an effect may be very telling in many situations, particularly in experimental research designs. In any case, your results may very well be of importance to others even though they did not support your hypothesis. Do not fall into the trap of thinking that results contrary to what you expected is a limitation to your study. If you carried out the research well, they are simply your results and only require additional interpretation.

Lewis, George H. and Jonathan F. Lewis. “The Dog in the Night-Time: Negative Evidence in Social Research.” The British Journal of Sociology 31 (December 1980): 544-558.

Yet Another Writing Tip

Sample Size Limitations in Qualitative Research

Sample sizes are typically smaller in qualitative research because, as the study goes on, acquiring more data does not necessarily lead to more information. This is because one occurrence of a piece of data, or a code, is all that is necessary to ensure that it becomes part of the analysis framework. However, it remains true that sample sizes that are too small cannot adequately support claims of having achieved valid conclusions and sample sizes that are too large do not permit the deep, naturalistic, and inductive analysis that defines qualitative inquiry. Determining adequate sample size in qualitative research is ultimately a matter of judgment and experience in evaluating the quality of the information collected against the uses to which it will be applied and the particular research method and purposeful sampling strategy employed. If the sample size is found to be a limitation, it may reflect your judgment about the methodological technique chosen [e.g., single life history study versus focus group interviews] rather than the number of respondents used.

Boddy, Clive Roland. "Sample Size for Qualitative Research." Qualitative Market Research: An International Journal 19 (2016): 426-432; Huberman, A. Michael and Matthew B. Miles. "Data Management and Analysis Methods." In Handbook of Qualitative Research . Norman K. Denzin and Yvonna S. Lincoln, eds. (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 1994), pp. 428-444; Blaikie, Norman. "Confounding Issues Related to Determining Sample Size in Qualitative Research." International Journal of Social Research Methodology 21 (2018): 635-641; Oppong, Steward Harrison. "The Problem of Sampling in qualitative Research." Asian Journal of Management Sciences and Education 2 (2013): 202-210.

- << Previous: 8. The Discussion

- Next: 9. The Conclusion >>

- Last Updated: Jun 18, 2024 10:45 AM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide

- Affiliate Program

- UNITED STATES

- 台灣 (TAIWAN)

- TÜRKIYE (TURKEY)

- Academic Editing Services

- - Research Paper

- - Journal Manuscript

- - Dissertation

- - College & University Assignments

- Admissions Editing Services

- - Application Essay

- - Personal Statement

- - Recommendation Letter

- - Cover Letter

- - CV/Resume

- Business Editing Services

- - Business Documents

- - Report & Brochure

- - Website & Blog

- Writer Editing Services

- - Script & Screenplay

- Our Editors

- Client Reviews

- Editing & Proofreading Prices

- Wordvice Points

- Partner Discount

- Plagiarism Checker

APA Citation Generator

MLA Citation Generator

Chicago Citation Generator

Vancouver Citation Generator

- - APA Style

- - MLA Style

- - Chicago Style

- - Vancouver Style

- Writing & Editing Guide

- Academic Resources

- Admissions Resources

How to Present the Limitations of the Study Examples

What are the limitations of a study?

The limitations of a study are the elements of methodology or study design that impact the interpretation of your research results. The limitations essentially detail any flaws or shortcomings in your study. Study limitations can exist due to constraints on research design, methodology, materials, etc., and these factors may impact the findings of your study. However, researchers are often reluctant to discuss the limitations of their study in their papers, feeling that bringing up limitations may undermine its research value in the eyes of readers and reviewers.

In spite of the impact it might have (and perhaps because of it) you should clearly acknowledge any limitations in your research paper in order to show readers—whether journal editors, other researchers, or the general public—that you are aware of these limitations and to explain how they affect the conclusions that can be drawn from the research.

In this article, we provide some guidelines for writing about research limitations, show examples of some frequently seen study limitations, and recommend techniques for presenting this information. And after you have finished drafting and have received manuscript editing for your work, you still might want to follow this up with academic editing before submitting your work to your target journal.

Why do I need to include limitations of research in my paper?

Although limitations address the potential weaknesses of a study, writing about them toward the end of your paper actually strengthens your study by identifying any problems before other researchers or reviewers find them.

Furthermore, pointing out study limitations shows that you’ve considered the impact of research weakness thoroughly and have an in-depth understanding of your research topic. Since all studies face limitations, being honest and detailing these limitations will impress researchers and reviewers more than ignoring them.

Where should I put the limitations of the study in my paper?

Some limitations might be evident to researchers before the start of the study, while others might become clear while you are conducting the research. Whether these limitations are anticipated or not, and whether they are due to research design or to methodology, they should be clearly identified and discussed in the discussion section —the final section of your paper. Most journals now require you to include a discussion of potential limitations of your work, and many journals now ask you to place this “limitations section” at the very end of your article.

Some journals ask you to also discuss the strengths of your work in this section, and some allow you to freely choose where to include that information in your discussion section—make sure to always check the author instructions of your target journal before you finalize a manuscript and submit it for peer review .

Limitations of the Study Examples

There are several reasons why limitations of research might exist. The two main categories of limitations are those that result from the methodology and those that result from issues with the researcher(s).

Common Methodological Limitations of Studies

Limitations of research due to methodological problems can be addressed by clearly and directly identifying the potential problem and suggesting ways in which this could have been addressed—and SHOULD be addressed in future studies. The following are some major potential methodological issues that can impact the conclusions researchers can draw from the research.

Issues with research samples and selection

Sampling errors occur when a probability sampling method is used to select a sample, but that sample does not reflect the general population or appropriate population concerned. This results in limitations of your study known as “sample bias” or “selection bias.”

For example, if you conducted a survey to obtain your research results, your samples (participants) were asked to respond to the survey questions. However, you might have had limited ability to gain access to the appropriate type or geographic scope of participants. In this case, the people who responded to your survey questions may not truly be a random sample.

Insufficient sample size for statistical measurements

When conducting a study, it is important to have a sufficient sample size in order to draw valid conclusions. The larger the sample, the more precise your results will be. If your sample size is too small, it will be difficult to identify significant relationships in the data.

Normally, statistical tests require a larger sample size to ensure that the sample is considered representative of a population and that the statistical result can be generalized to a larger population. It is a good idea to understand how to choose an appropriate sample size before you conduct your research by using scientific calculation tools—in fact, many journals now require such estimation to be included in every manuscript that is sent out for review.

Lack of previous research studies on the topic

Citing and referencing prior research studies constitutes the basis of the literature review for your thesis or study, and these prior studies provide the theoretical foundations for the research question you are investigating. However, depending on the scope of your research topic, prior research studies that are relevant to your thesis might be limited.

When there is very little or no prior research on a specific topic, you may need to develop an entirely new research typology. In this case, discovering a limitation can be considered an important opportunity to identify literature gaps and to present the need for further development in the area of study.

Methods/instruments/techniques used to collect the data

After you complete your analysis of the research findings (in the discussion section), you might realize that the manner in which you have collected the data or the ways in which you have measured variables has limited your ability to conduct a thorough analysis of the results.

For example, you might realize that you should have addressed your survey questions from another viable perspective, or that you were not able to include an important question in the survey. In these cases, you should acknowledge the deficiency or deficiencies by stating a need for future researchers to revise their specific methods for collecting data that includes these missing elements.

Common Limitations of the Researcher(s)

Study limitations that arise from situations relating to the researcher or researchers (whether the direct fault of the individuals or not) should also be addressed and dealt with, and remedies to decrease these limitations—both hypothetically in your study, and practically in future studies—should be proposed.

Limited access to data

If your research involved surveying certain people or organizations, you might have faced the problem of having limited access to these respondents. Due to this limited access, you might need to redesign or restructure your research in a different way. In this case, explain the reasons for limited access and be sure that your finding is still reliable and valid despite this limitation.

Time constraints

Just as students have deadlines to turn in their class papers, academic researchers might also have to meet deadlines for submitting a manuscript to a journal or face other time constraints related to their research (e.g., participants are only available during a certain period; funding runs out; collaborators move to a new institution). The time available to study a research problem and to measure change over time might be constrained by such practical issues. If time constraints negatively impacted your study in any way, acknowledge this impact by mentioning a need for a future study (e.g., a longitudinal study) to answer this research problem.

Conflicts arising from cultural bias and other personal issues

Researchers might hold biased views due to their cultural backgrounds or perspectives of certain phenomena, and this can affect a study’s legitimacy. Also, it is possible that researchers will have biases toward data and results that only support their hypotheses or arguments. In order to avoid these problems, the author(s) of a study should examine whether the way the research problem was stated and the data-gathering process was carried out appropriately.

Steps for Organizing Your Study Limitations Section

When you discuss the limitations of your study, don’t simply list and describe your limitations—explain how these limitations have influenced your research findings. There might be multiple limitations in your study, but you only need to point out and explain those that directly relate to and impact how you address your research questions.

We suggest that you divide your limitations section into three steps: (1) identify the study limitations; (2) explain how they impact your study in detail; and (3) propose a direction for future studies and present alternatives. By following this sequence when discussing your study’s limitations, you will be able to clearly demonstrate your study’s weakness without undermining the quality and integrity of your research.

Step 1. Identify the limitation(s) of the study

- This part should comprise around 10%-20% of your discussion of study limitations.

The first step is to identify the particular limitation(s) that affected your study. There are many possible limitations of research that can affect your study, but you don’t need to write a long review of all possible study limitations. A 200-500 word critique is an appropriate length for a research limitations section. In the beginning of this section, identify what limitations your study has faced and how important these limitations are.

You only need to identify limitations that had the greatest potential impact on: (1) the quality of your findings, and (2) your ability to answer your research question.

Step 2. Explain these study limitations in detail

- This part should comprise around 60-70% of your discussion of limitations.

After identifying your research limitations, it’s time to explain the nature of the limitations and how they potentially impacted your study. For example, when you conduct quantitative research, a lack of probability sampling is an important issue that you should mention. On the other hand, when you conduct qualitative research, the inability to generalize the research findings could be an issue that deserves mention.

Explain the role these limitations played on the results and implications of the research and justify the choice you made in using this “limiting” methodology or other action in your research. Also, make sure that these limitations didn’t undermine the quality of your dissertation .

Step 3. Propose a direction for future studies and present alternatives (optional)

- This part should comprise around 10-20% of your discussion of limitations.

After acknowledging the limitations of the research, you need to discuss some possible ways to overcome these limitations in future studies. One way to do this is to present alternative methodologies and ways to avoid issues with, or “fill in the gaps of” the limitations of this study you have presented. Discuss both the pros and cons of these alternatives and clearly explain why researchers should choose these approaches.

Make sure you are current on approaches used by prior studies and the impacts they have had on their findings. Cite review articles or scientific bodies that have recommended these approaches and why. This might be evidence in support of the approach you chose, or it might be the reason you consider your choices to be included as limitations. This process can act as a justification for your approach and a defense of your decision to take it while acknowledging the feasibility of other approaches.

P hrases and Tips for Introducing Your Study Limitations in the Discussion Section

The following phrases are frequently used to introduce the limitations of the study:

- “There may be some possible limitations in this study.”

- “The findings of this study have to be seen in light of some limitations.”

- “The first is the…The second limitation concerns the…”

- “The empirical results reported herein should be considered in the light of some limitations.”

- “This research, however, is subject to several limitations.”

- “The primary limitation to the generalization of these results is…”

- “Nonetheless, these results must be interpreted with caution and a number of limitations should be borne in mind.”

- “As with the majority of studies, the design of the current study is subject to limitations.”

- “There are two major limitations in this study that could be addressed in future research. First, the study focused on …. Second ….”

For more articles on research writing and the journal submissions and publication process, visit Wordvice’s Academic Resources page.

And be sure to receive professional English editing and proofreading services , including paper editing services , for your journal manuscript before submitting it to journal editors.

Wordvice Resources

Proofreading & Editing Guide

Writing the Results Section for a Research Paper

How to Write a Literature Review

Research Writing Tips: How to Draft a Powerful Discussion Section

How to Captivate Journal Readers with a Strong Introduction

Tips That Will Make Your Abstract a Success!

APA In-Text Citation Guide for Research Writing

Additional Resources

- Diving Deeper into Limitations and Delimitations (PhD student)

- Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper: Limitations of the Study (USC Library)

- Research Limitations (Research Methodology)

- How to Present Limitations and Alternatives (UMASS)

Article References

Pearson-Stuttard, J., Kypridemos, C., Collins, B., Mozaffarian, D., Huang, Y., Bandosz, P.,…Micha, R. (2018). Estimating the health and economic effects of the proposed US Food and Drug Administration voluntary sodium reformulation: Microsimulation cost-effectiveness analysis. PLOS. https://journals.plos.org/plosmedicine/article?id=10.1371/journal.pmed.1002551

Xu, W.L, Pedersen, N.L., Keller, L., Kalpouzos, G., Wang, H.X., Graff, C,. Fratiglioni, L. (2015). HHEX_23 AA Genotype Exacerbates Effect of Diabetes on Dementia and Alzheimer Disease: A Population-Based Longitudinal Study. PLOS. Retrieved from https://journals.plos.org/plosmedicine/article?id=10.1371/journal.pmed.1001853

What are the limitations in research and how to write them?

Learn about the potential limitations in research and how to appropriately address them in order to deliver honest and ethical research.

It is fairly uncommon for researchers to stumble into the term research limitations when working on their research paper. Limitations in research can arise owing to constraints on design, methods, materials, and so on, and these aspects, unfortunately, may have an influence on your subject’s findings.

In this Mind The Graph’s article, we’ll discuss some recommendations for writing limitations in research , provide examples of various common types of limitations, and suggest how to properly present this information.

What are the limitations in research?

The limitations in research are the constraints in design, methods or even researchers’ limitations that affect and influence the interpretation of your research’s ultimate findings. These are limitations on the generalization and usability of findings that emerge from the design of the research and/or the method employed to ensure validity both internally and externally.

Researchers are usually cautious to acknowledge the limitations of their research in their publications for fear of undermining the research’s scientific validity. No research is faultless or covers every possible angle. As a result, addressing the constraints of your research exhibits honesty and integrity .

Why should include limitations of research in my paper?

Though limitations tackle potential flaws in research, commenting on them at the conclusion of your paper, by demonstrating that you are aware of these limitations and explaining how they impact the conclusions that may be taken from the research, improves your research by disclosing any issues before other researchers or reviewers do .

Additionally, emphasizing research constraints implies that you have thoroughly investigated the ramifications of research shortcomings and have a thorough understanding of your research problem.

Limits exist in any research; being honest about them and explaining them would impress researchers and reviewers more than disregarding them.

Remember that acknowledging a research’s shortcomings offers a chance to provide ideas for future research, but be careful to describe how your study may help to concentrate on these outstanding problems.

Possible limitations examples

Here are some limitations connected to methodology and the research procedure that you may need to explain and discuss in connection to your findings.

Methodological limitations

Sample size.

The number of units of analysis used in your study is determined by the sort of research issue being investigated. It is important to note that if your sample is too small, finding significant connections in the data will be challenging, as statistical tests typically require a larger sample size to ensure a fair representation and this can be limiting.

Lack of available or reliable data

A lack of data or trustworthy data will almost certainly necessitate limiting the scope of your research or the size of your sample, or it can be a substantial impediment to identifying a pattern and a relevant connection.

Lack of prior research on the subject

Citing previous research papers forms the basis of your literature review and aids in comprehending the research subject you are researching. Yet there may be little if any, past research on your issue.

The measure used to collect data

After finishing your analysis of the findings, you realize that the method you used to collect data limited your capacity to undertake a comprehensive evaluation of the findings. Recognize the flaw by mentioning that future researchers should change the specific approach for data collection.

Issues with research samples and selection

Sampling inaccuracies arise when a probability sampling method is employed to choose a sample, but that sample does not accurately represent the overall population or the relevant group. As a result, your study suffers from “sampling bias” or “selection bias.”

Limitations of the research

When your research requires polling certain persons or a specific group, you may have encountered the issue of limited access to these interviewees. Because of the limited access, you may need to reorganize or rearrange your research. In this scenario, explain why access is restricted and ensure that your findings are still trustworthy and valid despite the constraint.

Time constraints

Practical difficulties may limit the amount of time available to explore a research issue and monitor changes as they occur. If time restrictions have any detrimental influence on your research, recognize this impact by expressing the necessity for a future investigation.

Due to their cultural origins or opinions on observed events, researchers may carry biased opinions, which can influence the credibility of a research. Furthermore, researchers may exhibit biases toward data and conclusions that only support their hypotheses or arguments.

The structure of the limitations section

The limitations of your research are usually stated at the beginning of the discussion section of your paper so that the reader is aware of and comprehends the limitations prior to actually reading the rest of your findings, or they are stated at the end of the discussion section as an acknowledgment of the need for further research.

The ideal way is to divide your limitations section into three steps:

1. Identify the research constraints;

2. Describe in great detail how they affect your research;

3. Mention the opportunity for future investigations and give possibilities.

By following this method while addressing the constraints of your research, you will be able to effectively highlight your research’s shortcomings without jeopardizing the quality and integrity of your research.

Present your research or paper in an innovative way

If you want your readers to be engaged and participate in your research, try Mind The Graph tool to add visual assets to your content. Infographics may improve comprehension and are easy to read, just as the Mind The Graph tool is simple to use and offers a variety of templates from which you can select the one that best suits your information.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Exclusive high quality content about effective visual communication in science.

About Jessica Abbadia

Jessica Abbadia is a lawyer that has been working in Digital Marketing since 2020, improving organic performance for apps and websites in various regions through ASO and SEO. Currently developing scientific and intellectual knowledge for the community's benefit. Jessica is an animal rights activist who enjoys reading and drinking strong coffee.

Content tags

How to present limitations in research

Last updated

30 January 2024

Reviewed by

Short on time? Get an AI generated summary of this article instead

Limitations don’t invalidate or diminish your results, but it’s best to acknowledge them. This will enable you to address any questions your study failed to answer because of them.

In this guide, learn how to recognize, present, and overcome limitations in research.

- What is a research limitation?