61 intriguing psychology research topics to explore

Last updated

11 January 2024

Reviewed by

Brittany Ferri, PhD, OTR/L

Psychology is an incredibly diverse, critical, and ever-changing area of study in the medical and health industries. Because of this, it’s a common area of study for students and healthcare professionals.

We’re walking you through picking the perfect topic for your upcoming paper or study. Keep reading for plenty of example topics to pique your interest and curiosity.

- How to choose a psychology research topic

Exploring a psychology-based topic for your research project? You need to pick a specific area of interest to collect compelling data.

Use these tips to help you narrow down which psychology topics to research:

Focus on a particular area of psychology

The most effective psychological research focuses on a smaller, niche concept or disorder within the scope of a study.

Psychology is a broad and fascinating area of science, including everything from diagnosed mental health disorders to sports performance mindset assessments.

This gives you plenty of different avenues to explore. Having a hard time choosing? Check out our list of 61 ideas further down in this article to get started.

Read the latest clinical studies

Once you’ve picked a more niche topic to explore, you need to do your due diligence and explore other research projects on the same topic.

This practice will help you learn more about your chosen topic, ask more specific questions, and avoid covering existing projects.

For the best results, we recommend creating a research folder of associated published papers to reference throughout your project. This makes it much easier to cite direct references and find inspiration down the line.

Find a topic you enjoy and ask questions

Once you’ve spent time researching and collecting references for your study, you finally get to explore.

Whether this research project is for work, school, or just for fun, having a passion for your research will make the project much more enjoyable. (Trust us, there will be times when that is the only thing that keeps you going.)

Now you’ve decided on the topic, ask more nuanced questions you might want to explore.

If you can, pick the direction that interests you the most to make the research process much more enjoyable.

- 61 psychology topics to research in 2024

Need some extra help starting your psychology research project on the right foot? Explore our list of 61 cutting-edge, in-demand psychology research topics to use as a starting point for your research journey.

- Psychology research topics for university students

As a university student, it can be hard to pick a research topic that fits the scope of your classes and is still compelling and unique.

Here are a few exciting topics we recommend exploring for your next assigned research project:

Mental health in post-secondary students

Seeking post-secondary education is a stressful and overwhelming experience for most students, making this topic a great choice to explore for your in-class research paper.

Examples of post-secondary mental health research topics include:

Student mental health status during exam season

Mental health disorder prevalence based on study major

The impact of chronic school stress on overall quality of life

The impacts of cyberbullying

Cyberbullying can occur at all ages, starting as early as elementary school and carrying through into professional workplaces.

Examples of cyberbullying-based research topics you can study include:

The impact of cyberbullying on self-esteem

Common reasons people engage in cyberbullying

Cyberbullying themes and commonly used terms

Cyberbullying habits in children vs. adults

The long-term effects of cyberbullying

- Clinical psychology research topics

If you’re looking to take a more clinical approach to your next project, here are a few topics that involve direct patient assessment for you to consider:

Chronic pain and mental health

Living with chronic pain dramatically impacts every aspect of a person’s life, including their mental and emotional health.

Here are a few examples of in-demand pain-related psychology research topics:

The connection between diabetic neuropathy and depression

Neurological pain and its connection to mental health disorders

Efficacy of meditation and mindfulness for pain management

The long-term effects of insomnia

Insomnia is where you have difficulty falling or staying asleep. It’s a common health concern that impacts millions of people worldwide.

This is an excellent topic because insomnia can have a variety of causes, offering many research possibilities.

Here are a few compelling psychology research topics about insomnia you could investigate:

The prevalence of insomnia based on age, gender, and ethnicity

Insomnia and its impact on workplace productivity

The connection between insomnia and mental health disorders

Efficacy and use of melatonin supplements for insomnia

The risks and benefits of prescription insomnia medications

Lifestyle options for managing insomnia symptoms

The efficacy of mental health treatment options

Management and treatment of mental health conditions is an ever-changing area of study. If you can witness or participate in mental health therapies, this can make a great research project.

Examples of mental health treatment-related psychology research topics include:

The efficacy of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) for patients with severe anxiety

The benefits and drawbacks of group vs. individual therapy sessions

Music therapy for mental health disorders

Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) for patients with depression

- Controversial psychology research paper topics

If you are looking to explore a more cutting-edge or modern psychology topic, you can delve into a variety of controversial and topical options:

The impact of social media and digital platforms

Ever since access to internet forums and video games became more commonplace, there’s been growing concern about the impact these digital platforms have on mental health.

Examples of social media and video game-related psychology research topics include:

The effect of edited images on self-confidence

How social media platforms impact social behavior

Video games and their impact on teenage anger and violence

Digital communication and the rapid spread of misinformation

The development of digital friendships

Psychotropic medications for mental health

In recent years, the interest in using psychoactive medications to treat and manage health conditions has increased despite their inherently controversial nature.

Examples of psychotropic medication-related research topics include:

The risks and benefits of using psilocybin mushrooms for managing anxiety

The impact of marijuana on early-onset psychosis

Childhood marijuana use and related prevalence of mental health conditions

Ketamine and its use for complex PTSD (C-PTSD) symptom management

The effect of long-term psychedelic use and mental health conditions

- Mental health disorder research topics

As one of the most popular subsections of psychology, studying mental health disorders and how they impact quality of life is an essential and impactful area of research.

While studies in these areas are common, there’s always room for additional exploration, including the following hot-button topics:

Anxiety and depression disorders

Anxiety and depression are well-known and heavily researched mental health disorders.

Despite this, we still don’t know many things about these conditions, making them great candidates for psychology research projects:

Social anxiety and its connection to chronic loneliness

C-PTSD symptoms and causes

The development of phobias

Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) behaviors and symptoms

Depression triggers and causes

Self-care tools and resources for depression

The prevalence of anxiety and depression in particular age groups or geographic areas

Bipolar disorder

Bipolar disorder is a complex and multi-faceted area of psychology research.

Use your research skills to learn more about this condition and its impact by choosing any of the following topics:

Early signs of bipolar disorder

The incidence of bipolar disorder in young adults

The efficacy of existing bipolar treatment options

Bipolar medication side effects

Cognitive behavioral therapy for people with bipolar

Schizoaffective disorder

Schizoaffective disorder is often stigmatized, and less common mental health disorders are a hotbed for new and exciting research.

Here are a few examples of interesting research topics related to this mental health disorder:

The prevalence of schizoaffective disorder by certain age groups or geographic locations

Risk factors for developing schizoaffective disorder

The prevalence and content of auditory and visual hallucinations

Alternative therapies for schizoaffective disorder

- Societal and systematic psychology research topics

Modern society’s impact is deeply enmeshed in our mental and emotional health on a personal and community level.

Here are a few examples of societal and systemic psychology research topics to explore in more detail:

Access to mental health services

While mental health awareness has risen over the past few decades, access to quality mental health treatment and resources is still not equitable.

This can significantly impact the severity of a person’s mental health symptoms, which can result in worse health outcomes if left untreated.

Explore this crucial issue and provide information about the need for improved mental health resource access by studying any of the following topics:

Rural vs. urban access to mental health resources

Access to crisis lines by location

Wait times for emergency mental health services

Inequities in mental health access based on income and location

Insurance coverage for mental health services

Systemic racism and mental health

Societal systems and the prevalence of systemic racism heavily impact every aspect of a person’s overall health.

Researching these topics draws attention to existing problems and contributes valuable insights into ways to improve access to care moving forward.

Examples of systemic racism-related psychology research topics include:

Access to mental health resources based on race

The prevalence of BIPOC mental health therapists in a chosen area

The impact of systemic racism on mental health and self-worth

Racism training for mental health workers

The prevalence of mental health disorders in discriminated groups

LGBTQIA+ mental health concerns

Research about LGBTQIA+ people and their mental health needs is a unique area of study to explore for your next research project. It’s a commonly overlooked and underserved community.

Examples of LGBTQIA+ psychology research topics to consider include:

Mental health supports for queer teens and children

The impact of queer safe spaces on mental health

The prevalence of mental health disorders in the LGBTQIA+ community

The benefits of queer mentorship and found family

Substance misuse in LQBTQIA+ youth and adults

- Collect data and identify trends with Dovetail

Psychology research is an exciting and competitive study area, making it the perfect choice for projects or papers.

Take the headache out of analyzing your data and instantly access the insights you need to complete your next psychology research project by teaming up with Dovetail today.

Should you be using a customer insights hub?

Do you want to discover previous research faster?

Do you share your research findings with others?

Do you analyze research data?

Start for free today, add your research, and get to key insights faster

Editor’s picks

Last updated: 11 January 2024

Last updated: 15 January 2024

Last updated: 17 January 2024

Last updated: 12 May 2023

Last updated: 30 April 2024

Last updated: 18 May 2023

Last updated: 25 November 2023

Last updated: 13 May 2024

Latest articles

Related topics, .css-je19u9{-webkit-align-items:flex-end;-webkit-box-align:flex-end;-ms-flex-align:flex-end;align-items:flex-end;display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-flex-direction:row;-ms-flex-direction:row;flex-direction:row;-webkit-box-flex-wrap:wrap;-webkit-flex-wrap:wrap;-ms-flex-wrap:wrap;flex-wrap:wrap;-webkit-box-pack:center;-ms-flex-pack:center;-webkit-justify-content:center;justify-content:center;row-gap:0;text-align:center;max-width:671px;}@media (max-width: 1079px){.css-je19u9{max-width:400px;}.css-je19u9>span{white-space:pre;}}@media (max-width: 799px){.css-je19u9{max-width:400px;}.css-je19u9>span{white-space:pre;}} decide what to .css-1kiodld{max-height:56px;display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;}@media (max-width: 1079px){.css-1kiodld{display:none;}} build next, decide what to build next.

Users report unexpectedly high data usage, especially during streaming sessions.

Users find it hard to navigate from the home page to relevant playlists in the app.

It would be great to have a sleep timer feature, especially for bedtime listening.

I need better filters to find the songs or artists I’m looking for.

Log in or sign up

Get started for free

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

7.2 Correlational Research

Learning objectives.

- Define correlational research and give several examples.

- Explain why a researcher might choose to conduct correlational research rather than experimental research or another type of nonexperimental research.

What Is Correlational Research?

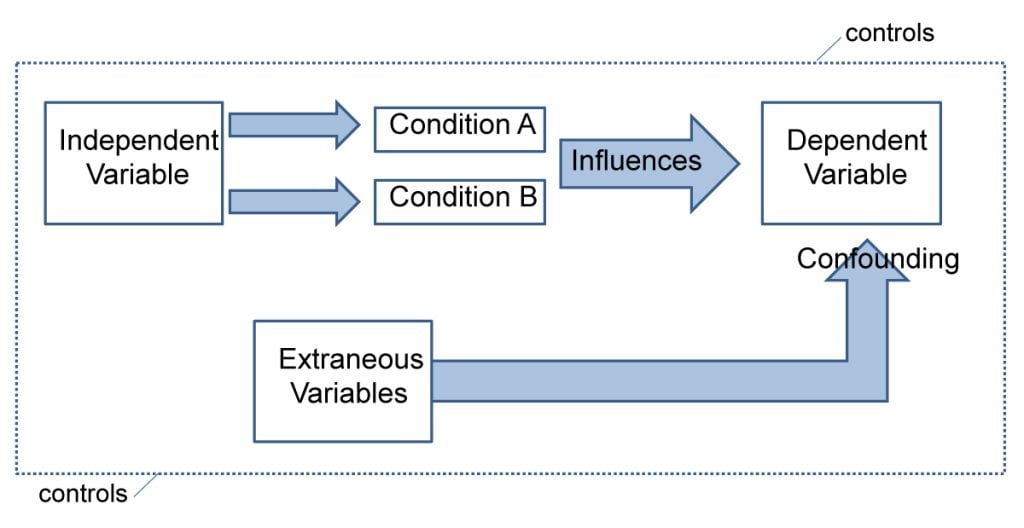

Correlational research is a type of nonexperimental research in which the researcher measures two variables and assesses the statistical relationship (i.e., the correlation) between them with little or no effort to control extraneous variables. There are essentially two reasons that researchers interested in statistical relationships between variables would choose to conduct a correlational study rather than an experiment. The first is that they do not believe that the statistical relationship is a causal one. For example, a researcher might evaluate the validity of a brief extraversion test by administering it to a large group of participants along with a longer extraversion test that has already been shown to be valid. This researcher might then check to see whether participants’ scores on the brief test are strongly correlated with their scores on the longer one. Neither test score is thought to cause the other, so there is no independent variable to manipulate. In fact, the terms independent variable and dependent variable do not apply to this kind of research.

The other reason that researchers would choose to use a correlational study rather than an experiment is that the statistical relationship of interest is thought to be causal, but the researcher cannot manipulate the independent variable because it is impossible, impractical, or unethical. For example, Allen Kanner and his colleagues thought that the number of “daily hassles” (e.g., rude salespeople, heavy traffic) that people experience affects the number of physical and psychological symptoms they have (Kanner, Coyne, Schaefer, & Lazarus, 1981). But because they could not manipulate the number of daily hassles their participants experienced, they had to settle for measuring the number of daily hassles—along with the number of symptoms—using self-report questionnaires. Although the strong positive relationship they found between these two variables is consistent with their idea that hassles cause symptoms, it is also consistent with the idea that symptoms cause hassles or that some third variable (e.g., neuroticism) causes both.

A common misconception among beginning researchers is that correlational research must involve two quantitative variables, such as scores on two extraversion tests or the number of hassles and number of symptoms people have experienced. However, the defining feature of correlational research is that the two variables are measured—neither one is manipulated—and this is true regardless of whether the variables are quantitative or categorical. Imagine, for example, that a researcher administers the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale to 50 American college students and 50 Japanese college students. Although this “feels” like a between-subjects experiment, it is a correlational study because the researcher did not manipulate the students’ nationalities. The same is true of the study by Cacioppo and Petty comparing college faculty and factory workers in terms of their need for cognition. It is a correlational study because the researchers did not manipulate the participants’ occupations.

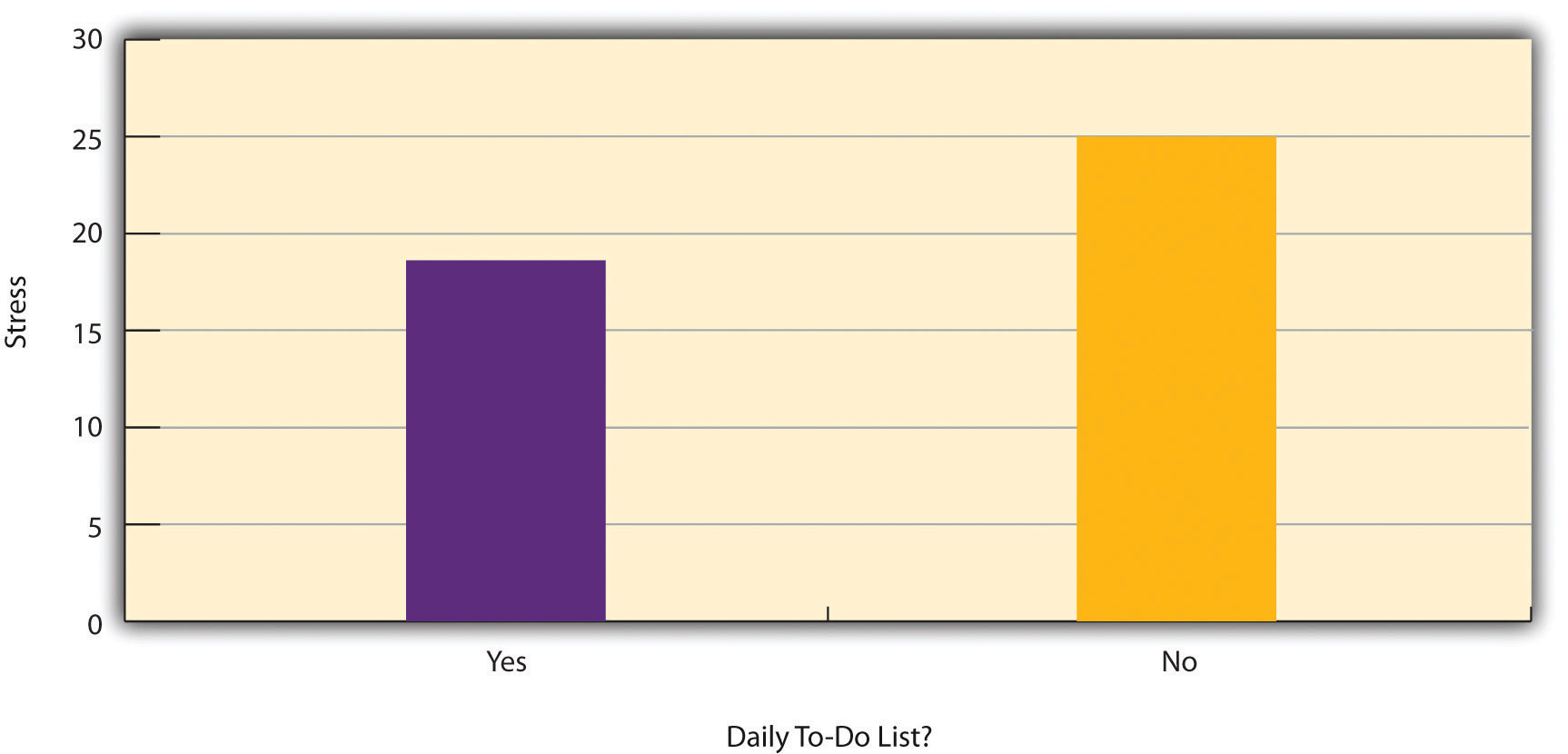

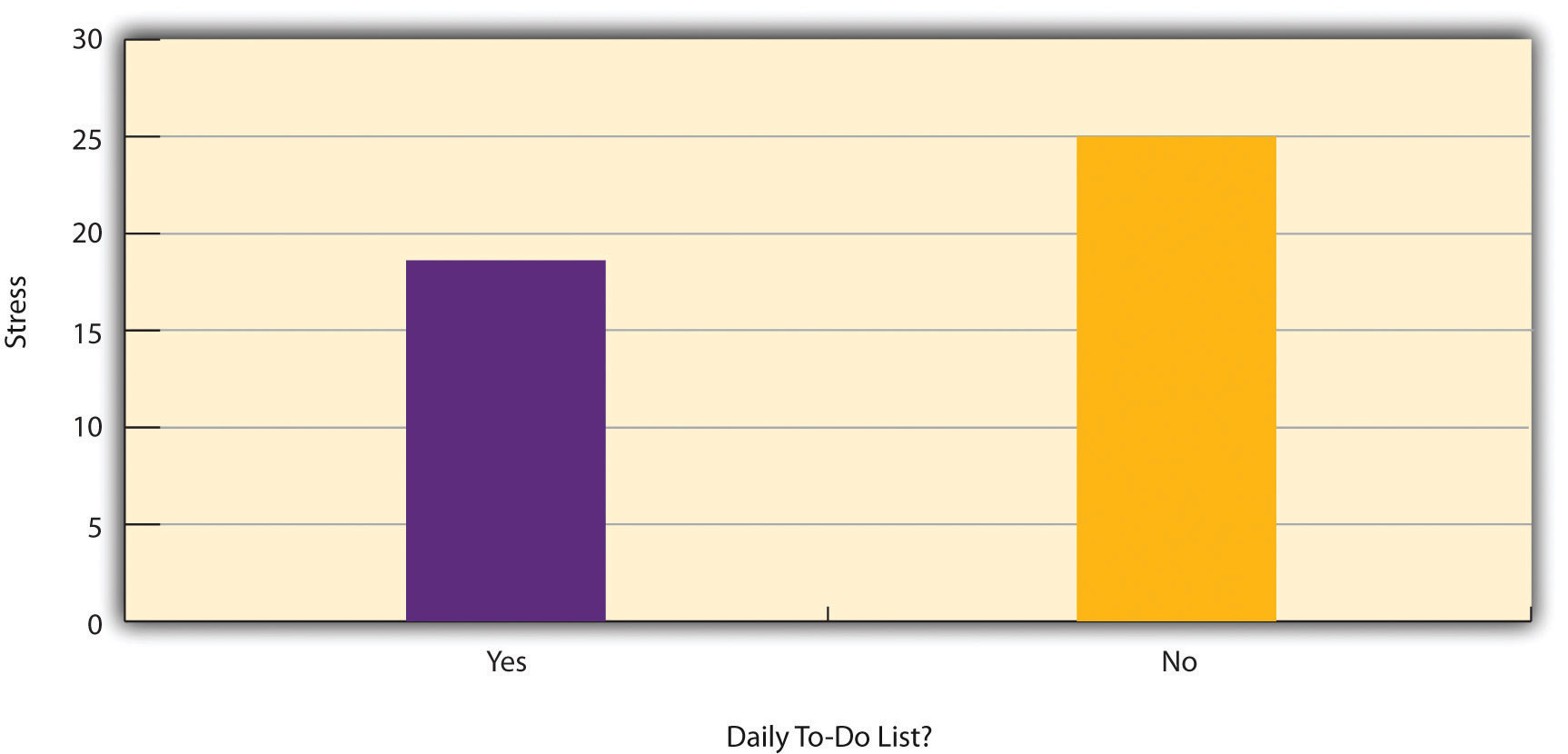

Figure 7.2 “Results of a Hypothetical Study on Whether People Who Make Daily To-Do Lists Experience Less Stress Than People Who Do Not Make Such Lists” shows data from a hypothetical study on the relationship between whether people make a daily list of things to do (a “to-do list”) and stress. Notice that it is unclear whether this is an experiment or a correlational study because it is unclear whether the independent variable was manipulated. If the researcher randomly assigned some participants to make daily to-do lists and others not to, then it is an experiment. If the researcher simply asked participants whether they made daily to-do lists, then it is a correlational study. The distinction is important because if the study was an experiment, then it could be concluded that making the daily to-do lists reduced participants’ stress. But if it was a correlational study, it could only be concluded that these variables are statistically related. Perhaps being stressed has a negative effect on people’s ability to plan ahead (the directionality problem). Or perhaps people who are more conscientious are more likely to make to-do lists and less likely to be stressed (the third-variable problem). The crucial point is that what defines a study as experimental or correlational is not the variables being studied, nor whether the variables are quantitative or categorical, nor the type of graph or statistics used to analyze the data. It is how the study is conducted.

Figure 7.2 Results of a Hypothetical Study on Whether People Who Make Daily To-Do Lists Experience Less Stress Than People Who Do Not Make Such Lists

Data Collection in Correlational Research

Again, the defining feature of correlational research is that neither variable is manipulated. It does not matter how or where the variables are measured. A researcher could have participants come to a laboratory to complete a computerized backward digit span task and a computerized risky decision-making task and then assess the relationship between participants’ scores on the two tasks. Or a researcher could go to a shopping mall to ask people about their attitudes toward the environment and their shopping habits and then assess the relationship between these two variables. Both of these studies would be correlational because no independent variable is manipulated. However, because some approaches to data collection are strongly associated with correlational research, it makes sense to discuss them here. The two we will focus on are naturalistic observation and archival data. A third, survey research, is discussed in its own chapter.

Naturalistic Observation

Naturalistic observation is an approach to data collection that involves observing people’s behavior in the environment in which it typically occurs. Thus naturalistic observation is a type of field research (as opposed to a type of laboratory research). It could involve observing shoppers in a grocery store, children on a school playground, or psychiatric inpatients in their wards. Researchers engaged in naturalistic observation usually make their observations as unobtrusively as possible so that participants are often not aware that they are being studied. Ethically, this is considered to be acceptable if the participants remain anonymous and the behavior occurs in a public setting where people would not normally have an expectation of privacy. Grocery shoppers putting items into their shopping carts, for example, are engaged in public behavior that is easily observable by store employees and other shoppers. For this reason, most researchers would consider it ethically acceptable to observe them for a study. On the other hand, one of the arguments against the ethicality of the naturalistic observation of “bathroom behavior” discussed earlier in the book is that people have a reasonable expectation of privacy even in a public restroom and that this expectation was violated.

Researchers Robert Levine and Ara Norenzayan used naturalistic observation to study differences in the “pace of life” across countries (Levine & Norenzayan, 1999). One of their measures involved observing pedestrians in a large city to see how long it took them to walk 60 feet. They found that people in some countries walked reliably faster than people in other countries. For example, people in the United States and Japan covered 60 feet in about 12 seconds on average, while people in Brazil and Romania took close to 17 seconds.

Because naturalistic observation takes place in the complex and even chaotic “real world,” there are two closely related issues that researchers must deal with before collecting data. The first is sampling. When, where, and under what conditions will the observations be made, and who exactly will be observed? Levine and Norenzayan described their sampling process as follows:

Male and female walking speed over a distance of 60 feet was measured in at least two locations in main downtown areas in each city. Measurements were taken during main business hours on clear summer days. All locations were flat, unobstructed, had broad sidewalks, and were sufficiently uncrowded to allow pedestrians to move at potentially maximum speeds. To control for the effects of socializing, only pedestrians walking alone were used. Children, individuals with obvious physical handicaps, and window-shoppers were not timed. Thirty-five men and 35 women were timed in most cities. (p. 186)

Precise specification of the sampling process in this way makes data collection manageable for the observers, and it also provides some control over important extraneous variables. For example, by making their observations on clear summer days in all countries, Levine and Norenzayan controlled for effects of the weather on people’s walking speeds.

The second issue is measurement. What specific behaviors will be observed? In Levine and Norenzayan’s study, measurement was relatively straightforward. They simply measured out a 60-foot distance along a city sidewalk and then used a stopwatch to time participants as they walked over that distance. Often, however, the behaviors of interest are not so obvious or objective. For example, researchers Robert Kraut and Robert Johnston wanted to study bowlers’ reactions to their shots, both when they were facing the pins and then when they turned toward their companions (Kraut & Johnston, 1979). But what “reactions” should they observe? Based on previous research and their own pilot testing, Kraut and Johnston created a list of reactions that included “closed smile,” “open smile,” “laugh,” “neutral face,” “look down,” “look away,” and “face cover” (covering one’s face with one’s hands). The observers committed this list to memory and then practiced by coding the reactions of bowlers who had been videotaped. During the actual study, the observers spoke into an audio recorder, describing the reactions they observed. Among the most interesting results of this study was that bowlers rarely smiled while they still faced the pins. They were much more likely to smile after they turned toward their companions, suggesting that smiling is not purely an expression of happiness but also a form of social communication.

Naturalistic observation has revealed that bowlers tend to smile when they turn away from the pins and toward their companions, suggesting that smiling is not purely an expression of happiness but also a form of social communication.

sieneke toering – bowling big lebowski style – CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

When the observations require a judgment on the part of the observers—as in Kraut and Johnston’s study—this process is often described as coding . Coding generally requires clearly defining a set of target behaviors. The observers then categorize participants individually in terms of which behavior they have engaged in and the number of times they engaged in each behavior. The observers might even record the duration of each behavior. The target behaviors must be defined in such a way that different observers code them in the same way. This is the issue of interrater reliability. Researchers are expected to demonstrate the interrater reliability of their coding procedure by having multiple raters code the same behaviors independently and then showing that the different observers are in close agreement. Kraut and Johnston, for example, video recorded a subset of their participants’ reactions and had two observers independently code them. The two observers showed that they agreed on the reactions that were exhibited 97% of the time, indicating good interrater reliability.

Archival Data

Another approach to correlational research is the use of archival data , which are data that have already been collected for some other purpose. An example is a study by Brett Pelham and his colleagues on “implicit egotism”—the tendency for people to prefer people, places, and things that are similar to themselves (Pelham, Carvallo, & Jones, 2005). In one study, they examined Social Security records to show that women with the names Virginia, Georgia, Louise, and Florence were especially likely to have moved to the states of Virginia, Georgia, Louisiana, and Florida, respectively.

As with naturalistic observation, measurement can be more or less straightforward when working with archival data. For example, counting the number of people named Virginia who live in various states based on Social Security records is relatively straightforward. But consider a study by Christopher Peterson and his colleagues on the relationship between optimism and health using data that had been collected many years before for a study on adult development (Peterson, Seligman, & Vaillant, 1988). In the 1940s, healthy male college students had completed an open-ended questionnaire about difficult wartime experiences. In the late 1980s, Peterson and his colleagues reviewed the men’s questionnaire responses to obtain a measure of explanatory style—their habitual ways of explaining bad events that happen to them. More pessimistic people tend to blame themselves and expect long-term negative consequences that affect many aspects of their lives, while more optimistic people tend to blame outside forces and expect limited negative consequences. To obtain a measure of explanatory style for each participant, the researchers used a procedure in which all negative events mentioned in the questionnaire responses, and any causal explanations for them, were identified and written on index cards. These were given to a separate group of raters who rated each explanation in terms of three separate dimensions of optimism-pessimism. These ratings were then averaged to produce an explanatory style score for each participant. The researchers then assessed the statistical relationship between the men’s explanatory style as college students and archival measures of their health at approximately 60 years of age. The primary result was that the more optimistic the men were as college students, the healthier they were as older men. Pearson’s r was +.25.

This is an example of content analysis —a family of systematic approaches to measurement using complex archival data. Just as naturalistic observation requires specifying the behaviors of interest and then noting them as they occur, content analysis requires specifying keywords, phrases, or ideas and then finding all occurrences of them in the data. These occurrences can then be counted, timed (e.g., the amount of time devoted to entertainment topics on the nightly news show), or analyzed in a variety of other ways.

Key Takeaways

- Correlational research involves measuring two variables and assessing the relationship between them, with no manipulation of an independent variable.

- Correlational research is not defined by where or how the data are collected. However, some approaches to data collection are strongly associated with correlational research. These include naturalistic observation (in which researchers observe people’s behavior in the context in which it normally occurs) and the use of archival data that were already collected for some other purpose.

Discussion: For each of the following, decide whether it is most likely that the study described is experimental or correlational and explain why.

- An educational researcher compares the academic performance of students from the “rich” side of town with that of students from the “poor” side of town.

- A cognitive psychologist compares the ability of people to recall words that they were instructed to “read” with their ability to recall words that they were instructed to “imagine.”

- A manager studies the correlation between new employees’ college grade point averages and their first-year performance reports.

- An automotive engineer installs different stick shifts in a new car prototype, each time asking several people to rate how comfortable the stick shift feels.

- A food scientist studies the relationship between the temperature inside people’s refrigerators and the amount of bacteria on their food.

- A social psychologist tells some research participants that they need to hurry over to the next building to complete a study. She tells others that they can take their time. Then she observes whether they stop to help a research assistant who is pretending to be hurt.

Kanner, A. D., Coyne, J. C., Schaefer, C., & Lazarus, R. S. (1981). Comparison of two modes of stress measurement: Daily hassles and uplifts versus major life events. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 4 , 1–39.

Kraut, R. E., & Johnston, R. E. (1979). Social and emotional messages of smiling: An ethological approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 37 , 1539–1553.

Levine, R. V., & Norenzayan, A. (1999). The pace of life in 31 countries. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 30 , 178–205.

Pelham, B. W., Carvallo, M., & Jones, J. T. (2005). Implicit egotism. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 14 , 106–110.

Peterson, C., Seligman, M. E. P., & Vaillant, G. E. (1988). Pessimistic explanatory style is a risk factor for physical illness: A thirty-five year longitudinal study. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 55 , 23–27.

Research Methods in Psychology Copyright © 2016 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Correlational Research

Rajiv S. Jhangiani; I-Chant A. Chiang; Carrie Cuttler; and Dana C. Leighton

Learning Objectives

- Define correlational research and give several examples.

- Explain why a researcher might choose to conduct correlational research rather than experimental research or another type of non-experimental research.

- Interpret the strength and direction of different correlation coefficients.

- Explain why correlation does not imply causation.

What Is Correlational Research?

Correlational research is a type of non-experimental research in which the researcher measures two variables (binary or continuous) and assesses the statistical relationship (i.e., the correlation) between them with little or no effort to control extraneous variables. There are many reasons that researchers interested in statistical relationships between variables would choose to conduct a correlational study rather than an experiment. The first is that they do not believe that the statistical relationship is a causal one or are not interested in causal relationships. Recall two goals of science are to describe and to predict and the correlational research strategy allows researchers to achieve both of these goals. Specifically, this strategy can be used to describe the strength and direction of the relationship between two variables and if there is a relationship between the variables then the researchers can use scores on one variable to predict scores on the other (using a statistical technique called regression, which is discussed further in the section on Complex Correlation in this chapter).

Another reason that researchers would choose to use a correlational study rather than an experiment is that the statistical relationship of interest is thought to be causal, but the researcher cannot manipulate the independent variable because it is impossible, impractical, or unethical. For example, while a researcher might be interested in the relationship between the frequency people use cannabis and their memory abilities they cannot ethically manipulate the frequency that people use cannabis. As such, they must rely on the correlational research strategy; they must simply measure the frequency that people use cannabis and measure their memory abilities using a standardized test of memory and then determine whether the frequency people use cannabis is statistically related to memory test performance.

Correlation is also used to establish the reliability and validity of measurements. For example, a researcher might evaluate the validity of a brief extraversion test by administering it to a large group of participants along with a longer extraversion test that has already been shown to be valid. This researcher might then check to see whether participants’ scores on the brief test are strongly correlated with their scores on the longer one. Neither test score is thought to cause the other, so there is no independent variable to manipulate. In fact, the terms independent variable and dependent variabl e do not apply to this kind of research.

Another strength of correlational research is that it is often higher in external validity than experimental research. Recall there is typically a trade-off between internal validity and external validity. As greater controls are added to experiments, internal validity is increased but often at the expense of external validity as artificial conditions are introduced that do not exist in reality. In contrast, correlational studies typically have low internal validity because nothing is manipulated or controlled but they often have high external validity. Since nothing is manipulated or controlled by the experimenter the results are more likely to reflect relationships that exist in the real world.

Finally, extending upon this trade-off between internal and external validity, correlational research can help to provide converging evidence for a theory. If a theory is supported by a true experiment that is high in internal validity as well as by a correlational study that is high in external validity then the researchers can have more confidence in the validity of their theory. As a concrete example, correlational studies establishing that there is a relationship between watching violent television and aggressive behavior have been complemented by experimental studies confirming that the relationship is a causal one (Bushman & Huesmann, 2001) [1] .

Does Correlational Research Always Involve Quantitative Variables?

A common misconception among beginning researchers is that correlational research must involve two quantitative variables, such as scores on two extraversion tests or the number of daily hassles and number of symptoms people have experienced. However, the defining feature of correlational research is that the two variables are measured—neither one is manipulated—and this is true regardless of whether the variables are quantitative or categorical. Imagine, for example, that a researcher administers the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale to 50 American college students and 50 Japanese college students. Although this “feels” like a between-subjects experiment, it is a correlational study because the researcher did not manipulate the students’ nationalities. The same is true of the study by Cacioppo and Petty comparing college faculty and factory workers in terms of their need for cognition. It is a correlational study because the researchers did not manipulate the participants’ occupations.

Figure 6.2 shows data from a hypothetical study on the relationship between whether people make a daily list of things to do (a “to-do list”) and stress. Notice that it is unclear whether this is an experiment or a correlational study because it is unclear whether the independent variable was manipulated. If the researcher randomly assigned some participants to make daily to-do lists and others not to, then it is an experiment. If the researcher simply asked participants whether they made daily to-do lists, then it is a correlational study. The distinction is important because if the study was an experiment, then it could be concluded that making the daily to-do lists reduced participants’ stress. But if it was a correlational study, it could only be concluded that these variables are statistically related. Perhaps being stressed has a negative effect on people’s ability to plan ahead (the directionality problem). Or perhaps people who are more conscientious are more likely to make to-do lists and less likely to be stressed (the third-variable problem). The crucial point is that what defines a study as experimental or correlational is not the variables being studied, nor whether the variables are quantitative or categorical, nor the type of graph or statistics used to analyze the data. What defines a study is how the study is conducted.

Data Collection in Correlational Research

Again, the defining feature of correlational research is that neither variable is manipulated. It does not matter how or where the variables are measured. A researcher could have participants come to a laboratory to complete a computerized backward digit span task and a computerized risky decision-making task and then assess the relationship between participants’ scores on the two tasks. Or a researcher could go to a shopping mall to ask people about their attitudes toward the environment and their shopping habits and then assess the relationship between these two variables. Both of these studies would be correlational because no independent variable is manipulated.

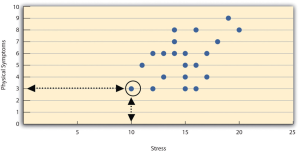

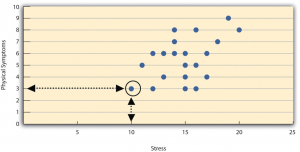

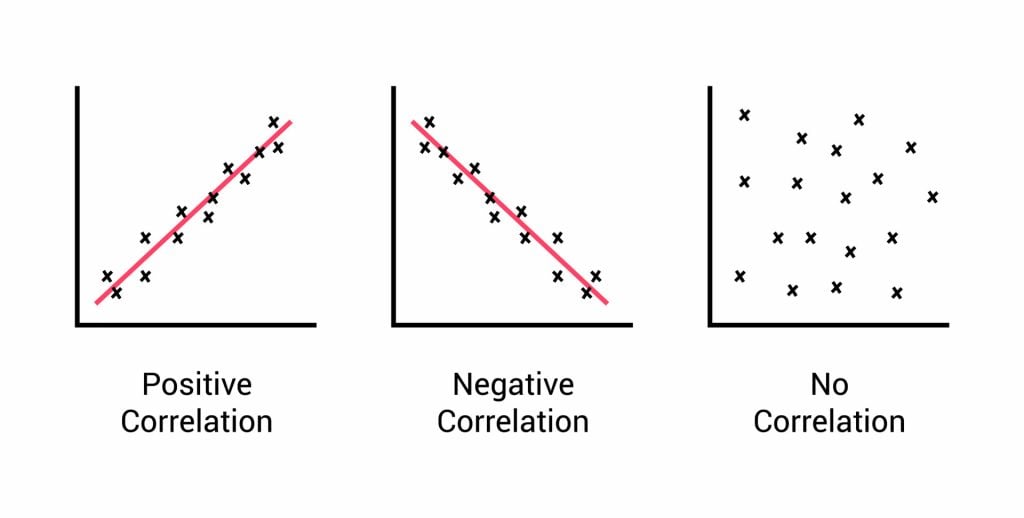

Correlations Between Quantitative Variables

Correlations between quantitative variables are often presented using scatterplots . Figure 6.3 shows some hypothetical data on the relationship between the amount of stress people are under and the number of physical symptoms they have. Each point in the scatterplot represents one person’s score on both variables. For example, the circled point in Figure 6.3 represents a person whose stress score was 10 and who had three physical symptoms. Taking all the points into account, one can see that people under more stress tend to have more physical symptoms. This is a good example of a positive relationship , in which higher scores on one variable tend to be associated with higher scores on the other. In other words, they move in the same direction, either both up or both down. A negative relationship is one in which higher scores on one variable tend to be associated with lower scores on the other. In other words, they move in opposite directions. There is a negative relationship between stress and immune system functioning, for example, because higher stress is associated with lower immune system functioning.

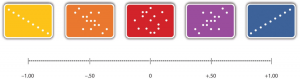

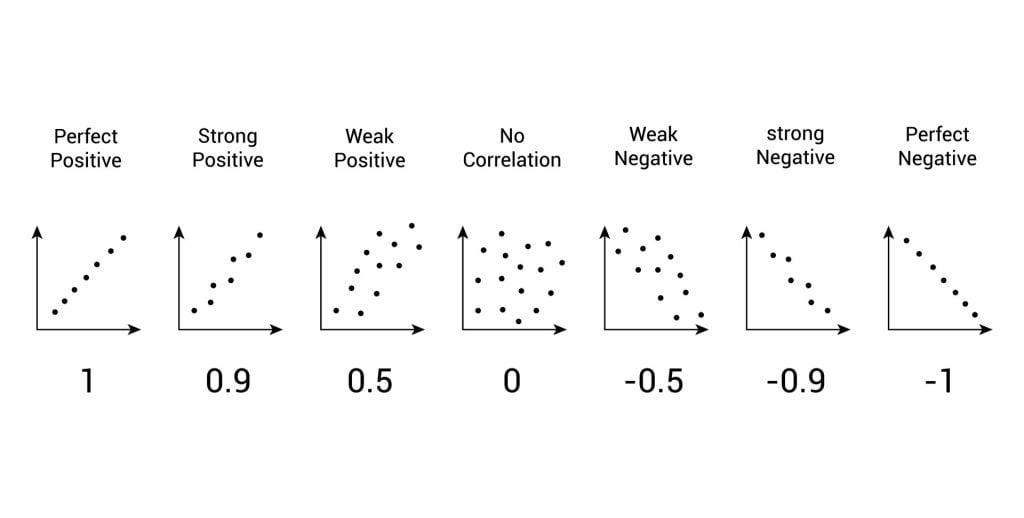

The strength of a correlation between quantitative variables is typically measured using a statistic called Pearson’s Correlation Coefficient (or Pearson's r ) . As Figure 6.4 shows, Pearson’s r ranges from −1.00 (the strongest possible negative relationship) to +1.00 (the strongest possible positive relationship). A value of 0 means there is no relationship between the two variables. When Pearson’s r is 0, the points on a scatterplot form a shapeless “cloud.” As its value moves toward −1.00 or +1.00, the points come closer and closer to falling on a single straight line. Correlation coefficients near ±.10 are considered small, values near ± .30 are considered medium, and values near ±.50 are considered large. Notice that the sign of Pearson’s r is unrelated to its strength. Pearson’s r values of +.30 and −.30, for example, are equally strong; it is just that one represents a moderate positive relationship and the other a moderate negative relationship. With the exception of reliability coefficients, most correlations that we find in Psychology are small or moderate in size. The website http://rpsychologist.com/d3/correlation/ , created by Kristoffer Magnusson, provides an excellent interactive visualization of correlations that permits you to adjust the strength and direction of a correlation while witnessing the corresponding changes to the scatterplot.

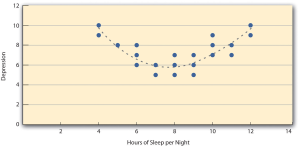

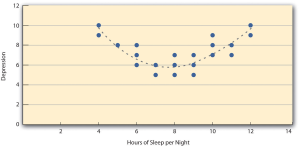

There are two common situations in which the value of Pearson’s r can be misleading. Pearson’s r is a good measure only for linear relationships, in which the points are best approximated by a straight line. It is not a good measure for nonlinear relationships, in which the points are better approximated by a curved line. Figure 6.5, for example, shows a hypothetical relationship between the amount of sleep people get per night and their level of depression. In this example, the line that best approximates the points is a curve—a kind of upside-down “U”—because people who get about eight hours of sleep tend to be the least depressed. Those who get too little sleep and those who get too much sleep tend to be more depressed. Even though Figure 6.5 shows a fairly strong relationship between depression and sleep, Pearson’s r would be close to zero because the points in the scatterplot are not well fit by a single straight line. This means that it is important to make a scatterplot and confirm that a relationship is approximately linear before using Pearson’s r . Nonlinear relationships are fairly common in psychology, but measuring their strength is beyond the scope of this book.

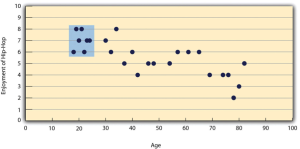

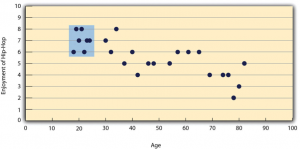

The other common situations in which the value of Pearson’s r can be misleading is when one or both of the variables have a limited range in the sample relative to the population. This problem is referred to as restriction of range . Assume, for example, that there is a strong negative correlation between people’s age and their enjoyment of hip hop music as shown by the scatterplot in Figure 6.6. Pearson’s r here is −.77. However, if we were to collect data only from 18- to 24-year-olds—represented by the shaded area of Figure 6.6—then the relationship would seem to be quite weak. In fact, Pearson’s r for this restricted range of ages is 0. It is a good idea, therefore, to design studies to avoid restriction of range. For example, if age is one of your primary variables, then you can plan to collect data from people of a wide range of ages. Because restriction of range is not always anticipated or easily avoidable, however, it is good practice to examine your data for possible restriction of range and to interpret Pearson’s r in light of it. (There are also statistical methods to correct Pearson’s r for restriction of range, but they are beyond the scope of this book).

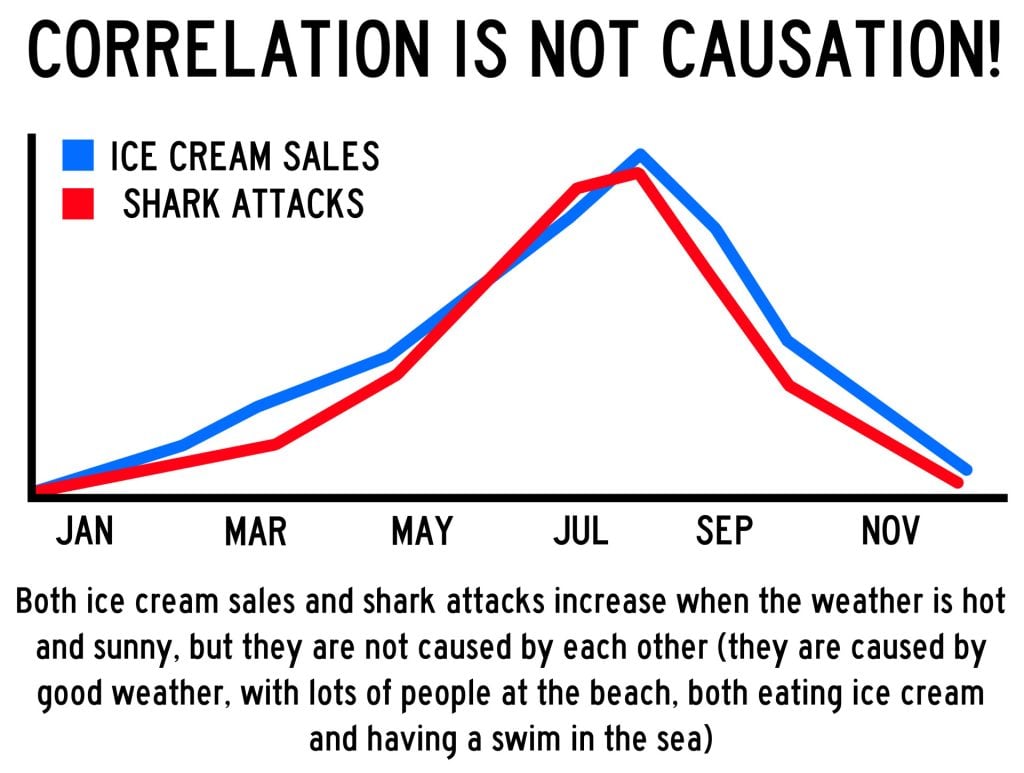

Correlation Does Not Imply Causation

You have probably heard repeatedly that “Correlation does not imply causation.” An amusing example of this comes from a 2012 study that showed a positive correlation (Pearson’s r = 0.79) between the per capita chocolate consumption of a nation and the number of Nobel prizes awarded to citizens of that nation [2] . It seems clear, however, that this does not mean that eating chocolate causes people to win Nobel prizes, and it would not make sense to try to increase the number of Nobel prizes won by recommending that parents feed their children more chocolate.

There are two reasons that correlation does not imply causation. The first is called the directionality problem . Two variables, X and Y , can be statistically related because X causes Y or because Y causes X . Consider, for example, a study showing that whether or not people exercise is statistically related to how happy they are—such that people who exercise are happier on average than people who do not. This statistical relationship is consistent with the idea that exercising causes happiness, but it is also consistent with the idea that happiness causes exercise. Perhaps being happy gives people more energy or leads them to seek opportunities to socialize with others by going to the gym. The second reason that correlation does not imply causation is called the third-variable problem . Two variables, X and Y , can be statistically related not because X causes Y , or because Y causes X , but because some third variable, Z , causes both X and Y . For example, the fact that nations that have won more Nobel prizes tend to have higher chocolate consumption probably reflects geography in that European countries tend to have higher rates of per capita chocolate consumption and invest more in education and technology (once again, per capita) than many other countries in the world. Similarly, the statistical relationship between exercise and happiness could mean that some third variable, such as physical health, causes both of the others. Being physically healthy could cause people to exercise and cause them to be happier. Correlations that are a result of a third-variable are often referred to as spurious correlations .

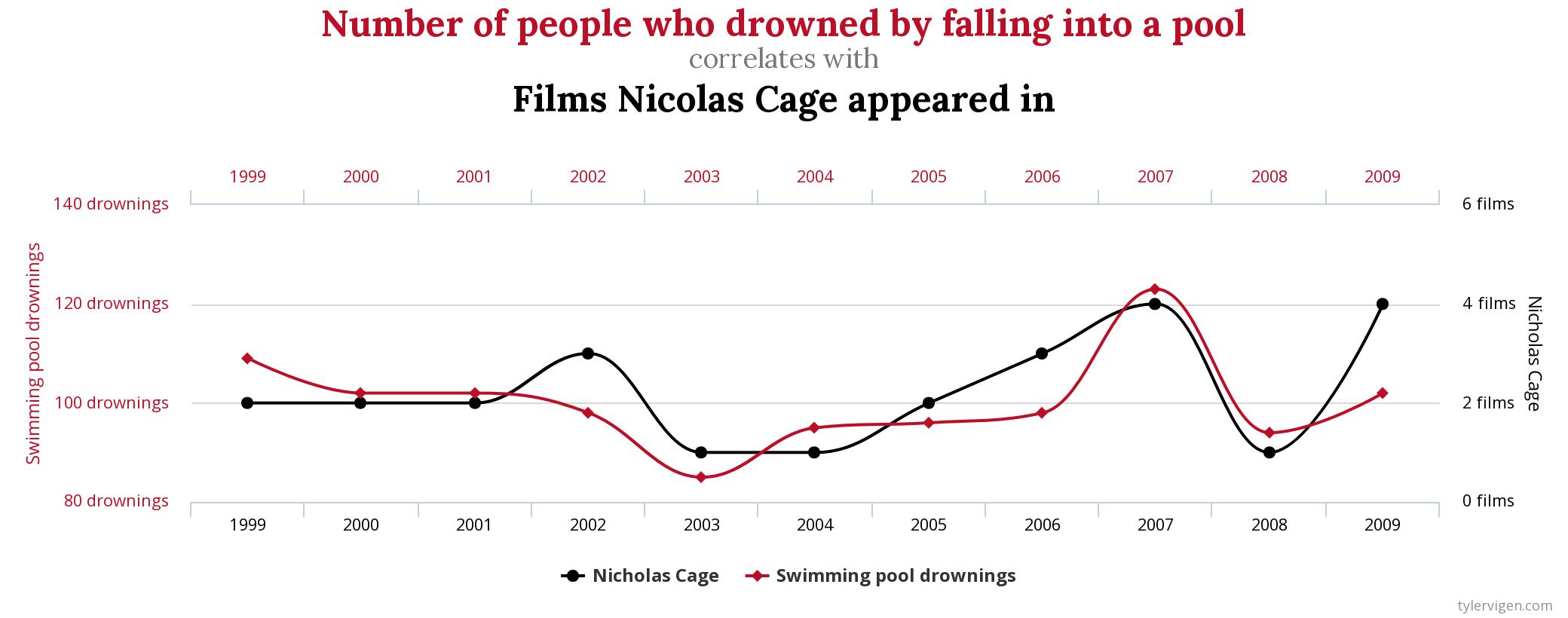

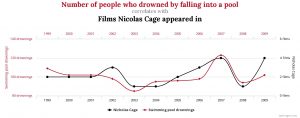

Some excellent and amusing examples of spurious correlations can be found at http://www.tylervigen.com (Figure 6.7 provides one such example).

“Lots of Candy Could Lead to Violence”

Although researchers in psychology know that correlation does not imply causation, many journalists do not. One website about correlation and causation, http://jonathan.mueller.faculty.noctrl.edu/100/correlation_or_causation.htm , links to dozens of media reports about real biomedical and psychological research. Many of the headlines suggest that a causal relationship has been demonstrated when a careful reading of the articles shows that it has not because of the directionality and third-variable problems.

One such article is about a study showing that children who ate candy every day were more likely than other children to be arrested for a violent offense later in life. But could candy really “lead to” violence, as the headline suggests? What alternative explanations can you think of for this statistical relationship? How could the headline be rewritten so that it is not misleading?

As you have learned by reading this book, there are various ways that researchers address the directionality and third-variable problems. The most effective is to conduct an experiment. For example, instead of simply measuring how much people exercise, a researcher could bring people into a laboratory and randomly assign half of them to run on a treadmill for 15 minutes and the rest to sit on a couch for 15 minutes. Although this seems like a minor change to the research design, it is extremely important. Now if the exercisers end up in more positive moods than those who did not exercise, it cannot be because their moods affected how much they exercised (because it was the researcher who used random assignment to determine how much they exercised). Likewise, it cannot be because some third variable (e.g., physical health) affected both how much they exercised and what mood they were in. Thus experiments eliminate the directionality and third-variable problems and allow researchers to draw firm conclusions about causal relationships.

Media Attributions

- Nicholas Cage and Pool Drownings © Tyler Viegen is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Bushman, B. J., & Huesmann, L. R. (2001). Effects of televised violence on aggression. In D. Singer & J. Singer (Eds.), Handbook of children and the media (pp. 223–254). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. ↵

- Messerli, F. H. (2012). Chocolate consumption, cognitive function, and Nobel laureates. New England Journal of Medicine, 367 , 1562-1564. ↵

A graph that presents correlations between two quantitative variables, one on the x-axis and one on the y-axis. Scores are plotted at the intersection of the values on each axis.

A relationship in which higher scores on one variable tend to be associated with higher scores on the other.

A relationship in which higher scores on one variable tend to be associated with lower scores on the other.

A statistic that measures the strength of a correlation between quantitative variables.

When one or both variables have a limited range in the sample relative to the population, making the value of the correlation coefficient misleading.

The problem where two variables, X and Y , are statistically related either because X causes Y, or because Y causes X , and thus the causal direction of the effect cannot be known.

Two variables, X and Y, can be statistically related not because X causes Y, or because Y causes X, but because some third variable, Z, causes both X and Y.

Correlations that are a result not of the two variables being measured, but rather because of a third, unmeasured, variable that affects both of the measured variables.

Correlational Research Copyright © by Rajiv S. Jhangiani; I-Chant A. Chiang; Carrie Cuttler; and Dana C. Leighton is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Research Topics & Ideas: Psychology

100+ Psychology Topic Ideas To Fast-Track Your Research

If you’re starting out on the dissertation or thesis journey for your psychology degree, the very first challenge you’ll face is finding a solid research topic . In this post, we’ll help get the topic ideation process started by providing a meaty list of research ideas, spanning a range of psychology sub-disciplines. We’ll also look at some examples from actual theses and dissertations to give you an idea of what these look like in the real world.

NB – This is just the start…

The topic ideation and evaluation process has multiple steps (which we’ll explain a little later). Therefore, it’s important to recognise that this post is only the first step in finding a high-quality psychology-centred research topic. To develop a research topic, you’ll need to identify a clear and convincing research gap , and a viable plan of action to fill that gap.

If this all sounds a bit intimidating, be sure to check out our free dissertation mini-course , which covers the process of writing a dissertation or thesis from A-Z. You can also sign up for our free webinar that explores how to find a high-quality research topic. Alternatively, if you’d like hands-on help, have a look at our 1-on-1 coaching service .

Overview: Psychology-Related Topics

- How to find a research topic (video)

- Behavioural psychology

- Clinical psychology

- Cognitive psychology

- Developmental psychology

- Educational psychology

- Forensic psychology

- Social psychology

- Sports psychology

- Examples of actual dissertation topics

- Free Webinar : Topic Ideation 101

- Where to get extra help

How To Find A Research Topic

In the video below, we explain how to find suitable research ideas (in psychology or any field), and how to then refine those into well-articulated potential topics for your dissertation or thesis. We also discuss a few important evaluation criteria to help you make the right choice for your project.

Below you’ll find a list of research ideas to get your thinking started. Please note that these research topic ideas are intentionally broad and generic, so you will need to refine them a fair deal using the techniques we discussed in the video above.

We’ve grouped the topic ideas based on a few popular areas of psychology to make it a little easier for you to find something in your particular field of interest. That said, there is naturally some overlap between topics, so keep this in mind.

Research Ideas: Behavioural Psychology

- Cultural variation in behaviour and mental health of adolescents during a disaster: a case study

- The impact of parental drug use and risky behaviour on early child development

- The effects of video game violence on aggressive behaviour among teenage boys in school

- The relationship between adverse childhood experiences and adult risk-seeking behaviour

- The impact of physical exercise on anxiety and health-harming behaviour

- The relationship between personality traits and addiction behaviour

- The effects of reinforcement schedules on decision-making and associative learning

- The effects of daily mindfulness practice on stress and anxiety in middle-aged women

- The use of behavioural interventions in the treatment of eating disorders in poorer communities

- Understanding implicit cognitive processes involved in the over-consumption of fast food

- The use of cognitive behavioural therapy for alcohol addiction treatment

- The impact of extensive technology use in children on long-term attention and focus

- The impact of social media on self-destructive behaviour and poor mental health outcomes

- Exploring the role of sleep and sleep deprivation on healthy behaviours

Research Ideas: Clinical Psychology

- The use of mindfulness-based approaches in the treatment of anxiety disorders among college students

- The use of technology in the delivery of psychological services in war-torn countries

- The effectiveness of dialectical behaviour therapy for borderline personality disorder

- The use of virtual reality technology in the treatment of phobias and PTSD among war veterans

- The role of childhood adversity on adult mental health in immigrant populations in the USA

- The role of genetics and epigenetics in the development of bipolar disorder in Pakistani women: an integrative review

- The effectiveness of pharmacotherapy in the treatment of social anxiety among hikikomori in Japan

- The perception of healthcare workers and patients on the use of teletherapy for the delivery of psychological services

- The impact of social support on mental health outcomes among single parents.

- The effectiveness of integrative therapeutic approaches in the treatment of schizophrenia

- The effectiveness of trauma-focused therapies on post-traumatic growth in domestic abuse survivors

- The role and use of cognitive-behavioural therapy for depression among first-generation students

- The effectiveness of family therapy in addressing childhood trauma and depression

- The impact of cultural mistrust on the diagnosis and treatment of mental health issues in culturally-diverse populations

- The effectiveness of group therapy on post-traumatic stress symptoms among survivors of sexual assault

Research Ideas: Cognitive Psychology

- The impact of lifelong aerobic exercise on cognitive function in old age

- The effects of evening screen use on cognitive development in preschool children

- The impact of sleep deprivation on decision-making among graduate students

- The use of neuroimaging to understand the neural basis of memory retrieval

- The effect of conservative religious homes on social functioning in LGBT+ adolescents

- The role of positive emotions in working memory among high school learners

- The neural basis of decision-making and problem-solving during undergraduate statistic assessments

- The neural basis of language processing among adults learning English as a second language

- The role of technological tools in improving working memory in older adults

- The role of attention in emotional face processing among adult males

- The impact of depression on cognitive function during ageing The impact of daily meditation and mindfulness practice on cognitive function

- The relationship between increased protein intake and improved cognitive function

- The effects of stress on cognitive function among final-year learners

Research Ideas: Developmental Psychology

- The impact of maternal affection on cognitive, social, and emotional development

- The effects of parenting styles on children’s executive function

- The impact of late-night screen use on child development

- The role of digital play on child development outcomes

- Exploring the impact of poverty on early child development in Brazil

- The trauma-informed care as moderating the impact of trauma on child development

- Evaluating the relationship between peer relationship quality and child social development

- The impact of child-targeted media and advertising on child behavioural development

- The role of parental attachment in child resilience

- The moderating impact of culture on bullying and child social development

- The impact of single-parenting on child development in India

- The impact of early educational interventions on child socio-emotional development

- The impact of digital technology use on adolescent development and mental health

- The impact of socioeconomic status on child executive function

- The role of genetics and epigenetics on child neurodevelopmental outcomes linked to depression

Need a helping hand?

Research Ideas: Educational Psychology

- The relationship between self-regulated learning and academic performance in asynchronous versus synchronous learning environments

- Exploring effective parental involvement strategies and their impact on student achievement

- The role of intrinsic motivation in formative assessment in the classroom

- The impact of classroom management and practice on student learning and behaviour

- University students’ preference regarding online learning environments

- The effects of gentrification on student achievement in traditionally poor neighbourhoods

- The impact of teacher expectations and academic self-concept on K12 student mathematics performance

- The use and effectiveness of game-based learning in a high school biology classroom

- The impact of prejudice on the relationship between student motivation and academic performance among Black university students

- The impact of culture on second language English student learning preferences

- The effects of student self-efficacy and engagement on academic performance in secondary school mathematics

- The role of metacognition in learning musicality in hip hop

- The role of small group instruction on teacher efficacy and stress in early childhood education

- The perception and use of multimedia among high school biology teachers in France

- The use of augmented reality applications and its impact on student learning, motivation and attitude

Research Ideas: Forensic Psychology

- The impact of trauma on the psychological functioning of police officers and first responders

- Understanding cultural considerations during forensic psychological assessment and treatment of trauma

- Ethical considerations of the use of AI in forensic psychology in the legal system

- The psychological factors related to recidivism among white collar female offenders in the USA

- The psychological factors related to false confessions among juveniles

- Understanding the use of psychological assessment in the evaluation of eyewitness testimony in criminal courts in England

- The impact of trauma on the reflective functioning of adult female sexual assault victims

- The use and effectiveness of psychological interventions in reducing recidivism among non-violent criminals

- The impact of domestic violence on the mental health and forensic evaluation of men

- Exploring the ethical considerations and use of behavioural analysis in the study of criminal behaviour

- The use and limitations of neuropsychological assessment in forensic evaluations

- The use of social media forensics in evaluating criminal behaviour in violent crimes

- The racialised use of psychological assessment in the evaluation of competency to stand trial in Canada

- Exploring the use and availability of virtual reality technologies in forensic psychology in Spain

- The impact of motivational interviewing-based interventions among criminalized drug users

Research Ideas: Social Psychology

- The impact of prejudice and discrimination on social behaviour among African immigrants in South Africa

- The impact of social networks on behaviour and well-being among young adult females

- The effects of social identity on non-conformity in University students

- The effects of group dynamics on risk-seeking behaviour in adult men

- The impact of social media on the quality of interpersonal relationships among high school learners

- The impact of parental emotional intelligence on pro-social behaviour in children and adolescents

- The effects of conformity and deviance on social attitudes and behaviour during a global recession

- The effects of Tik Tok on social comparison and self-esteem among teenage girls

- Understanding gendered differences in social influence and algorithms on impulsive decision-making

- The effects of social support on mental health among healthcare workers in the UK

- The effects of gender roles on social behaviour among trans teens

- The impact of perceived power and social status on the behaviour of social media influencers

- The impact of social norms on prosocial behaviour among women

- The effects of community participation on aggression and violence in middle-aged men

- The impact of culture and gender on social behaviour during the COVID-19 pandemic

Research Ideas: Sports Psychology

- The moderating role of cultural factors on the relationship between mental health and sports performance in team sports

- The role of mindfulness practice in addressing stress and anxiety in young national athletes

- The relationship between team cohesion and performance in cricket teams

- The effect of transformational leadership on female sports teams in Canada

- The effect of positive self-talk on athletic performance and motivation among Olympic athletes

- The use and perception of hypnosis in New Zealand team sports Understanding stress and burnout in University team athletes

- The efficacy of personalised nutrition and diet on athletic performance among sprinters

- Exploring mental preparation techniques and their effect on athletic motivation and resilience among team-sport athletes

- Exploring the perception and understanding of goal-setting characteristics on athletic performance among team coaches

- The effects of motivational feedback on the performance of female gymnasts

- The perception and use of visualization and imagery among coaches as a means to enhance sport performance

- The impact of sports injuries on mental health and recovery in high school athletes

- The moderating role of sleep on mental toughness and sports performance in Olympic athletes

- The use and perception of technology in sports training and performance in little league softball

Psychology-Related Dissertations & Theses

While the ideas we’ve presented above are a decent starting point for finding a research topic in psychology, they are fairly generic and non-specific. So, it helps to look at actual dissertations and theses to see how this all comes together in practice.

Below, we’ve included a selection of research projects from various psychology degree programs to help refine your thinking. These are actual dissertations and theses, written as part of Master’s and PhD-level programs, so they can provide some useful insight as to what a research topic looks like in practice.

- Effects of a Patient Question Prompt List on Outpatient Palliative Care Appointments (McDarby, 2022)

- The role of affect and exercise goals in physical activity engagement in younger and older adults (Stojanovic, 2022)

- Lay Theories about Whether Emotion Helps or Hinders Reasoning and Well-being (Karnaze, 2022)

- The effects of blast-induced traumatic brain injury on two transgenic models of Alzheimer’s Disease (Gann, 2020)

- Understanding the parental mind: Examining the stability of parental reflective functioning across the birth of a child and associations with maternal mind-mindedness (Pitzen, 2021)

- An investigation of ineffective ally behaviours (Collier, 2019)

- Response Inhibition-Related Beta Power: Distinguishing Cognitively Intact Elders by Risk for Alzheimer’s Disease (Evans, 2021)

- Recognition Memory of Extremely High-Frequency Words (Miller, 2019)

- The Relationship between Dementia Caregiver Burden and Caregiver Communications in a Memory Clinic Setting (Martin, 2021)

- Examination of Maternal Versus Paternal Ratings of Child Pre-Injury Functioning in Predicting Child Post-Traumatic Stress Symptoms (Sayer, 2021)

- Electromyography As A Means of Predicting The Rubber Hand Illusion (Teaford, 2021)

- Linking Diversity Climate and Feedback Seeking Through Interpersonal Processes and Race Effects (Flores, 2021)

Looking at these titles, you can probably pick up that the research topics here are far more specific and narrowly-focused , compared to the generic ones presented earlier. This is an important thing to keep in mind as you develop your own research topic. That is to say, to create a top-notch research topic, you must be precise and target a specific context with specific variables of interest . In other words, you need to identify a clear, well-justified research gap.

Fast-Track Your Topic Ideation

Still unsure about how to find the right topic for your research project? Check out our private coaching services , where we work with psychology students on a 1:1 basis to help them find the perfect topic.

You Might Also Like:

10 Comments

Great insight

A very interesting site that offers a variety of options regarding research topics.

You’re most welcome

A good platform to get information

Amazing and interesting options 👌

Very useful but had not any field of research in health psychology

I feel honored going through this lovely stuff put together. Thank you so much

I need counseling psychology research topics

very empowering and insightful presentations. Can I be assisted in crafting a school psychology-related research topic about African context

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Non-Experimental Research

29 Correlational Research

Learning objectives.

- Define correlational research and give several examples.

- Explain why a researcher might choose to conduct correlational research rather than experimental research or another type of non-experimental research.

- Interpret the strength and direction of different correlation coefficients.

- Explain why correlation does not imply causation.

What Is Correlational Research?

Correlational research is a type of non-experimental research in which the researcher measures two variables (binary or continuous) and assesses the statistical relationship (i.e., the correlation) between them with little or no effort to control extraneous variables. There are many reasons that researchers interested in statistical relationships between variables would choose to conduct a correlational study rather than an experiment. The first is that they do not believe that the statistical relationship is a causal one or are not interested in causal relationships. Recall two goals of science are to describe and to predict and the correlational research strategy allows researchers to achieve both of these goals. Specifically, this strategy can be used to describe the strength and direction of the relationship between two variables and if there is a relationship between the variables then the researchers can use scores on one variable to predict scores on the other (using a statistical technique called regression, which is discussed further in the section on Complex Correlation in this chapter).

Another reason that researchers would choose to use a correlational study rather than an experiment is that the statistical relationship of interest is thought to be causal, but the researcher cannot manipulate the independent variable because it is impossible, impractical, or unethical. For example, while a researcher might be interested in the relationship between the frequency people use cannabis and their memory abilities they cannot ethically manipulate the frequency that people use cannabis. As such, they must rely on the correlational research strategy; they must simply measure the frequency that people use cannabis and measure their memory abilities using a standardized test of memory and then determine whether the frequency people use cannabis is statistically related to memory test performance.

Correlation is also used to establish the reliability and validity of measurements. For example, a researcher might evaluate the validity of a brief extraversion test by administering it to a large group of participants along with a longer extraversion test that has already been shown to be valid. This researcher might then check to see whether participants’ scores on the brief test are strongly correlated with their scores on the longer one. Neither test score is thought to cause the other, so there is no independent variable to manipulate. In fact, the terms independent variable and dependent variabl e do not apply to this kind of research.

Another strength of correlational research is that it is often higher in external validity than experimental research. Recall there is typically a trade-off between internal validity and external validity. As greater controls are added to experiments, internal validity is increased but often at the expense of external validity as artificial conditions are introduced that do not exist in reality. In contrast, correlational studies typically have low internal validity because nothing is manipulated or controlled but they often have high external validity. Since nothing is manipulated or controlled by the experimenter the results are more likely to reflect relationships that exist in the real world.

Finally, extending upon this trade-off between internal and external validity, correlational research can help to provide converging evidence for a theory. If a theory is supported by a true experiment that is high in internal validity as well as by a correlational study that is high in external validity then the researchers can have more confidence in the validity of their theory. As a concrete example, correlational studies establishing that there is a relationship between watching violent television and aggressive behavior have been complemented by experimental studies confirming that the relationship is a causal one (Bushman & Huesmann, 2001) [1] .

Does Correlational Research Always Involve Quantitative Variables?

A common misconception among beginning researchers is that correlational research must involve two quantitative variables, such as scores on two extraversion tests or the number of daily hassles and number of symptoms people have experienced. However, the defining feature of correlational research is that the two variables are measured—neither one is manipulated—and this is true regardless of whether the variables are quantitative or categorical. Imagine, for example, that a researcher administers the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale to 50 American college students and 50 Japanese college students. Although this “feels” like a between-subjects experiment, it is a correlational study because the researcher did not manipulate the students’ nationalities. The same is true of the study by Cacioppo and Petty comparing college faculty and factory workers in terms of their need for cognition. It is a correlational study because the researchers did not manipulate the participants’ occupations.

Figure 6.2 shows data from a hypothetical study on the relationship between whether people make a daily list of things to do (a “to-do list”) and stress. Notice that it is unclear whether this is an experiment or a correlational study because it is unclear whether the independent variable was manipulated. If the researcher randomly assigned some participants to make daily to-do lists and others not to, then it is an experiment. If the researcher simply asked participants whether they made daily to-do lists, then it is a correlational study. The distinction is important because if the study was an experiment, then it could be concluded that making the daily to-do lists reduced participants’ stress. But if it was a correlational study, it could only be concluded that these variables are statistically related. Perhaps being stressed has a negative effect on people’s ability to plan ahead (the directionality problem). Or perhaps people who are more conscientious are more likely to make to-do lists and less likely to be stressed (the third-variable problem). The crucial point is that what defines a study as experimental or correlational is not the variables being studied, nor whether the variables are quantitative or categorical, nor the type of graph or statistics used to analyze the data. What defines a study is how the study is conducted.

Data Collection in Correlational Research

Again, the defining feature of correlational research is that neither variable is manipulated. It does not matter how or where the variables are measured. A researcher could have participants come to a laboratory to complete a computerized backward digit span task and a computerized risky decision-making task and then assess the relationship between participants’ scores on the two tasks. Or a researcher could go to a shopping mall to ask people about their attitudes toward the environment and their shopping habits and then assess the relationship between these two variables. Both of these studies would be correlational because no independent variable is manipulated.

Correlations Between Quantitative Variables

Correlations between quantitative variables are often presented using scatterplots . Figure 6.3 shows some hypothetical data on the relationship between the amount of stress people are under and the number of physical symptoms they have. Each point in the scatterplot represents one person’s score on both variables. For example, the circled point in Figure 6.3 represents a person whose stress score was 10 and who had three physical symptoms. Taking all the points into account, one can see that people under more stress tend to have more physical symptoms. This is a good example of a positive relationship , in which higher scores on one variable tend to be associated with higher scores on the other. In other words, they move in the same direction, either both up or both down. A negative relationship is one in which higher scores on one variable tend to be associated with lower scores on the other. In other words, they move in opposite directions. There is a negative relationship between stress and immune system functioning, for example, because higher stress is associated with lower immune system functioning.

The strength of a correlation between quantitative variables is typically measured using a statistic called Pearson’s Correlation Coefficient (or Pearson's r ) . As Figure 6.4 shows, Pearson’s r ranges from −1.00 (the strongest possible negative relationship) to +1.00 (the strongest possible positive relationship). A value of 0 means there is no relationship between the two variables. When Pearson’s r is 0, the points on a scatterplot form a shapeless “cloud.” As its value moves toward −1.00 or +1.00, the points come closer and closer to falling on a single straight line. Correlation coefficients near ±.10 are considered small, values near ± .30 are considered medium, and values near ±.50 are considered large. Notice that the sign of Pearson’s r is unrelated to its strength. Pearson’s r values of +.30 and −.30, for example, are equally strong; it is just that one represents a moderate positive relationship and the other a moderate negative relationship. With the exception of reliability coefficients, most correlations that we find in Psychology are small or moderate in size. The website http://rpsychologist.com/d3/correlation/ , created by Kristoffer Magnusson, provides an excellent interactive visualization of correlations that permits you to adjust the strength and direction of a correlation while witnessing the corresponding changes to the scatterplot.