Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

11.1 Evaluation research

Learning objectives.

- Describe how to conduct evaluation research

- Define inputs, outputs, and outcomes

- Identify the three goals of process assessment

As you may recall from the definition provided in Chapter 1, evaluation research is research conducted to assess the effects of specific programs or policies. Evaluation research is often used when some form of policy intervention is planned, such as welfare reform or school curriculum change. The focus on interventions and social problems makes it natural fit for social work researchers. It might be used to assess the extent to which intervention is necessary by attempting to define and diagnose social problems in social workers’ service areas, and it might also be used to understand whether their agencies’ interventions have had their intended consequences. Evaluation research is becoming more and more necessary for agencies to secure and maintain funding for their programs. The main types of evaluation research are needs assessments, outcomes assessments, process assessments, and efficiency analyses such as cost-benefits or cost-effectiveness analyses. We will discuss two types in this section: outcomes assessments and process assessments .

Outcomes Assessments

An outcomes assessment is an evaluation designed to discover if a program achieved its intended outcomes. Much like other types of research, it comes with its own peculiar terminology. Inputs are the resources needed for the program to operate. These include physical location, any equipment needed, staff (and experience/knowledge of those staff), monetary funding, and most importantly, the clients. Program administrators pull together the necessary resources to run an intervention or program. The program is the intervention your clients receive—perhaps giving them access to housing vouchers or enrolling them in a smoking cessation class. The outputs of programs are tangible results of the program process. Outputs in a program might include the number of clients served, staff members trained to implement the intervention, mobility assistance devices distributed, nicotine patches distributed, etc. By contrast, outcomes speak to the purpose of the program itself. Outcomes are the observed changes, whether intended or unintended, that occurred due to the program or intervention. By looking at each of these domains, evaluation researchers can obtain a comprehensive view of the program.

Let’s run through an example from the social work practice of the wife of Matt DeCarlo who wrote the source material for much of this textbook. She runs an after-school bicycling club called Pedal Up for children with mental health issues. She has a lot of inputs in her program. First, there are the children who enroll, the volunteer and paid staff members who supervise the kids (and their knowledge about bicycles and children’s mental health), the bicycles and equipment that all clients and staff use, the community center room they use as a home base, the paths of the city where they ride their bikes, and the public and private grants they use to fund the program. Next, the program itself is a twice weekly after-school program in which children learn about bicycle maintenance and bicycle safety for about 30 minutes each day and then spend at least an hour riding around the city on bicycle trails.

In measuring the outputs of this program, she has many options. She would probably include the number of children participating in the program or the number of bike rides or lessons given. Other outputs might include the number of miles logged by the children over the school year, the number of bicycle helmets or spare tires distributed, etc. Finally, the outcomes of the programs might include each child’s mental health symptoms or behavioral issues at school.

Process Assessments

Outcomes assessments are performed at the end of a program or at specific points during the grant reporting process. What if a social worker wants to assess earlier on in the process if the program is on target to achieve its outcomes? In that case a process assessment is recommended, which evaluates a program in its earlier stages. Faulkner and Faulkner (2016) describe three main goals for conducting a process evaluation.

The first is program description , in which the researcher simply tries to understand how the program looks like in everyday life for clients and staff members. In our Pedal Up example, assessing program description might involve measuring in the first few weeks the hours children spent riding their bikes, the number of children and staff in attendance, etc. This data will provide those in charge of the program an idea of how their ideas have translated from the grant proposal to the real world. If, for example, not enough children are showing up or if children are only able to ride their bikes for ten minutes each day, it may indicate that something is wrong.

Another important goal of process assessment is program monitoring . If you have some social work practice experience already, it’s likely you’ve encountered program monitoring. Agency administrators may look at sign-in sheets for groups, hours billed by clinicians, or other metrics to track how services are utilized over time. They may also assess whether clinicians are following the program correctly or if they are deviating from how the program was designed. This can be an issue in program evaluations of specific treatment models, as any differences between what the administrators conceptualized and what the clinicians implemented jeopardize the internal validity of the evaluation. If, in our Pedal Up example, we have a staff member who does not review bike safety each week or does not enforce helmet laws for some students, we could catch that through program monitoring.

The final goal of process assessments is quality assurance. At its most simple level, quality assurance may involve sending out satisfaction questionnaires to clients and staff members. If there are serious issues, it’s better to know them early on in a program so the program can be adapted to meet the needs of clients and staff. It is important to solicit staff feedback in addition to consumer feedback, as they have insight into how the program is working in practice and areas in which they may be falling short of what the program should be. In our example, we could spend some time talking with parents when they pick their children up from the program or hold a staff meeting to provide opportunities for those most involved in the program to provide feedback.

Needs Assessments

A third type of evaluation research is a needs assessment. A needs assessment can be used to demonstrate and document a community or organizational need and should be carried out in a way to better understand the context in which the need arises. Needs assessments focus on gaining a better understanding of a gap within an organization or community and developing a plan to address that gap. They will often precede the development of a program or organization and are often used to justify the necessity of a program or organization to fill a gap. Needs assessments can be general, such as asking members of a community or organization to reflect on the functioning of a community or organization, or they can be specific in which community or organization members are asked to respond to an identified gap within a community or agency.

Needs assessments should respond to the following questions:

- What is the need or gap?

- What data exist about the need or gap?

- What data are needed in order to develop a plan to fill the gap?

- What resources are available to do the needs assessment?

- Who should be involved in the analysis and interpretation of the data?

- How will the information gathered be used and for what purpose?

- How will the results be communicated to community partners?

In order to answer these questions, needs assessments often follow a four-step plan. First, researchers must identify a gap in a community or organization and explore what potential avenues could be pursued to address the gap. This involves deciphering what is known about the needs within the community or organization and determining the scope and direction of the needs assessment. The researcher may partner with key informants within the community to identify the need in order to develop a method of research to conduct the needs assessment.

Second, the researcher will gather data to better understand the need. Data could be collected from key informants within the community, community members themselves, members of an organization, or records from an agency or organization. This involves designing a research study in which a variety of data collection methods could be used, such as surveys, interviews, focus groups, community forums, and secondary analysis of existing data. Once the data are collected, they will be organized and analyzed according to the research questions guiding the needs assessment.

Third, information gathered during data collection will be used to develop a plan of action to fill the needs. This could be the development of a new community agency to address a gap of services within the community or the addition of a new program at an existing agency. This agency or program must be designed according to the results of the needs assessment in order to accurately address the gap.

Finally, the newly developed program or agency must be evaluated to determine if it is filling the gap revealed by the needs assessment. Evaluating the success of the agency or program is essential to the needs assessment process.

Evaluation research is a part of all social workers’ toolkits. It ensures that social work interventions achieve their intended effects. This protects our clients and ensures that money and other resources are not spent on programs that do not work. Evaluation research uses the skills of quantitative and qualitative research to ensure clients receive interventions that have been shown to be successful.

Key Takeaways

- Evaluation research is a common research task for social workers.

- Outcomes assessment evaluate the degree to which programs achieved their intended outcomes.

- Outputs differ from outcomes.

- Process assessments evaluate a program in its early stages, so changes can be made.

- Inputs- resources needed for the program to operate

- Outcomes- the issues the program is trying to change

- Outcomes assessment- an evaluation designed to discover if a program achieved its intended outcomes

- Outputs- tangible results of the program process

- Process assessment- an evaluation conducted during the earlier stages of a program or on an ongoing basis

- Program- the intervention clients receive

Image attributions

assess by Wokandapix CC-0

Foundations of Social Work Research Copyright © 2020 by Rebecca L. Mauldin is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

- Register or Log In

- 0) { document.location='/search/'+document.getElementById('quicksearch').value.trim().toLowerCase(); }">

Grinnell, Social Work Research and Evaluation, 11e

- Social Work

Social Work Research and Evaluation, 11e Instructor Resources

Grinnell, Unrau

The authors have assembled PowerPoint lecture outlines for all chapters to accompany this book. The PowerPoints are broken down by chapter, and each chapter has a PowerPoint except the ninth chapter.

The authors have assembled PowerPoint lecture outlines for all chapters to accompany this book. The PowerPoints are broken down by chapter, and each c...

Select your Country

- Technical Support

- Find My Rep

You are here

Social Work Research and Evaluation Examined Practice for Action

- Elizabeth DePoy - University of Maine, USA

- Stephen Gilson - University of Maine, USA

- Description

See what’s new to this edition by selecting the Features tab on this page. Should you need additional information or have questions regarding the HEOA information provided for this title, including what is new to this edition, please email [email protected] . Please include your name, contact information, and the name of the title for which you would like more information. For information on the HEOA, please go to http://ed.gov/policy/highered/leg/hea08/index.html .

For assistance with your order: Please email us at [email protected] or connect with your SAGE representative.

SAGE 2455 Teller Road Thousand Oaks, CA 91320 www.sagepub.com

“Within my 38 years of teaching, the authors offer the most creative presentation I have ever read for a research methods text.”

“Breaks down research methods into easily digestible pieces for both instructors and students.”

- The Examined Practice Model takes students through the full sequence of social work evaluation research, from problem definition to sharing knowledge outcomes, to help students integrate research and practice.

- A unique cognitive mapping tool links the possible causes and consequences of problems together to identify opportunities for professional activity, collaboration, and evaluation in any domain of social work practice.

- Five easy-to-understand, detailed case examples illustrate how research, thinking, and action are linked to practice.

- Presentation of the “social worker as knowledge creator” demonstrates that systematic capture of the practice of social work provides the knowledge base of the profession.

- The final chapter details each of the text’s case examples from the beginning to the end of the Model to demonstrate examined practice throughout all phases of social work.

For instructors

Select a purchasing option.

Shipped Options:

BUNDLE: York: Statistics for Human Service Evaluation + Depoy: Social Work Research and Evaluation

This title is also available on SAGE Knowledge , the ultimate social sciences online library. If your library doesn’t have access, ask your librarian to start a trial .

- < Previous

Home > WMU Authors > Books > 306

All Books and Monographs by WMU Authors

Social Work Research and Evaluation: Quantitative and Qualitative Approaches

Richard M. Grinnell Jr. , Western Michigan University Follow Yvonne Unrau , Western Michigan University Follow

Social Work

Document Type

Description.

This book is the longest standing and most widely adopted text in the field of social work research and evaluation. Since the first edition in 1981, it has been designed to provide beginning social work students the basic methodological foundation they need in order to successfully complete more advanced research courses that focus on single-system designs or program evaluations. Its content is explained in extraordinarily clear everyday language which is then illustrated with social work examples that social work students not only can understand, but appreciate as well. Many of the examples concern women and minorities, and special emphasis is given to the application of research methods to the study of these groups. Without a doubt, the major strength of this book is that it is written by social workers for social work students. The editors have once again secured an excellent and diverse group of social work research educators. The 31 contributors know firsthand, from their own extensive teaching and practice experiences, what social work students need to know in relation to research. They have subjected themselves to a discipline totally uncommon in compendia-that is, writing in terms of what is most needed for an integrated basic research methods book, rather than writing in line with their own predilections.

Call number in WMU's library

HV11 .S63 2005 (Waldo Library, WMU Authors Collection, First Floor)

Publication Date

Cengage Learning

- Disciplines

Citation for published book

Grinnell, Richard M, and Yvonne A. Unrau. Social Work Research and Evaluation: Quantitative and Qualitative Approaches. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005. Print.

Recommended Citation

Grinnell, Richard M. Jr. and Unrau, Yvonne, "Social Work Research and Evaluation: Quantitative and Qualitative Approaches" (2005). All Books and Monographs by WMU Authors . 306. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/books/306

Find in other libraries

Since January 23, 2015

ScholarWorks

Advanced Search

- Notify me via email or RSS

- Collections

Author Corner

Western Michigan University Libraries, Kalamazoo MI 49008-5353 USA | (269) 387-5611

Home | About | FAQ | My Account | Accessibility Statement

Privacy | Copyright

- Politics & Social Sciences

- Social Sciences

Enjoy fast, free delivery, exclusive deals, and award-winning movies & TV shows with Prime Try Prime and start saving today with fast, free delivery

Amazon Prime includes:

Fast, FREE Delivery is available to Prime members. To join, select "Try Amazon Prime and start saving today with Fast, FREE Delivery" below the Add to Cart button.

- Cardmembers earn 5% Back at Amazon.com with a Prime Credit Card.

- Unlimited Free Two-Day Delivery

- Streaming of thousands of movies and TV shows with limited ads on Prime Video.

- A Kindle book to borrow for free each month - with no due dates

- Listen to over 2 million songs and hundreds of playlists

- Unlimited photo storage with anywhere access

Important: Your credit card will NOT be charged when you start your free trial or if you cancel during the trial period. If you're happy with Amazon Prime, do nothing. At the end of the free trial, your membership will automatically upgrade to a monthly membership.

Buy new: .savingPriceOverride { color:#CC0C39!important; font-weight: 300!important; } .reinventMobileHeaderPrice { font-weight: 400; } #apex_offerDisplay_mobile_feature_div .reinventPriceSavingsPercentageMargin, #apex_offerDisplay_mobile_feature_div .reinventPricePriceToPayMargin { margin-right: 4px; } -29% $106.95 $ 106 . 95 FREE delivery Tuesday, May 28 Ships from: Amazon Sold by: itemspopularsonlineaindemand

Return this item for free.

Free returns are available for the shipping address you chose. You can return the item for any reason in new and unused condition: no shipping charges

- Go to your orders and start the return

- Select the return method

Save with Used - Good .savingPriceOverride { color:#CC0C39!important; font-weight: 300!important; } .reinventMobileHeaderPrice { font-weight: 400; } #apex_offerDisplay_mobile_feature_div .reinventPriceSavingsPercentageMargin, #apex_offerDisplay_mobile_feature_div .reinventPricePriceToPayMargin { margin-right: 4px; } $66.17 $ 66 . 17 FREE delivery Tuesday, May 28 Ships from: Amazon Sold by: Apex_media

Download the free Kindle app and start reading Kindle books instantly on your smartphone, tablet, or computer - no Kindle device required .

Read instantly on your browser with Kindle for Web.

Using your mobile phone camera - scan the code below and download the Kindle app.

Image Unavailable

- To view this video download Flash Player

Social Work Research and Evaluation: Foundations of Evidence-Based Practice 11th Edition

Purchase options and add-ons.

- ISBN-10 0190859024

- ISBN-13 978-0190859022

- Edition 11th

- Publisher Oxford University Press

- Publication date April 11, 2018

- Language English

- Dimensions 1.3 x 9.9 x 7.8 inches

- Print length 728 pages

- See all details

Frequently bought together

Customers who bought this item also bought

Editorial Reviews

Book description, about the author, product details.

- Publisher : Oxford University Press; 11th edition (April 11, 2018)

- Language : English

- Paperback : 728 pages

- ISBN-10 : 0190859024

- ISBN-13 : 978-0190859022

- Item Weight : 3.4 pounds

- Dimensions : 1.3 x 9.9 x 7.8 inches

- #159 in Social Sciences Research

- #330 in Social Work (Books)

- #527 in Social Sciences (Books)

Customer reviews

Customer Reviews, including Product Star Ratings help customers to learn more about the product and decide whether it is the right product for them.

To calculate the overall star rating and percentage breakdown by star, we don’t use a simple average. Instead, our system considers things like how recent a review is and if the reviewer bought the item on Amazon. It also analyzed reviews to verify trustworthiness.

- Sort reviews by Top reviews Most recent Top reviews

Top reviews from the United States

There was a problem filtering reviews right now. please try again later..

- Amazon Newsletter

- About Amazon

- Accessibility

- Sustainability

- Press Center

- Investor Relations

- Amazon Devices

- Amazon Science

- Sell on Amazon

- Sell apps on Amazon

- Supply to Amazon

- Protect & Build Your Brand

- Become an Affiliate

- Become a Delivery Driver

- Start a Package Delivery Business

- Advertise Your Products

- Self-Publish with Us

- Become an Amazon Hub Partner

- › See More Ways to Make Money

- Amazon Visa

- Amazon Store Card

- Amazon Secured Card

- Amazon Business Card

- Shop with Points

- Credit Card Marketplace

- Reload Your Balance

- Amazon Currency Converter

- Your Account

- Your Orders

- Shipping Rates & Policies

- Amazon Prime

- Returns & Replacements

- Manage Your Content and Devices

- Recalls and Product Safety Alerts

- Conditions of Use

- Privacy Notice

- Consumer Health Data Privacy Disclosure

- Your Ads Privacy Choices

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Module 1 Chapter 3: Practice Evaluation as Evidence

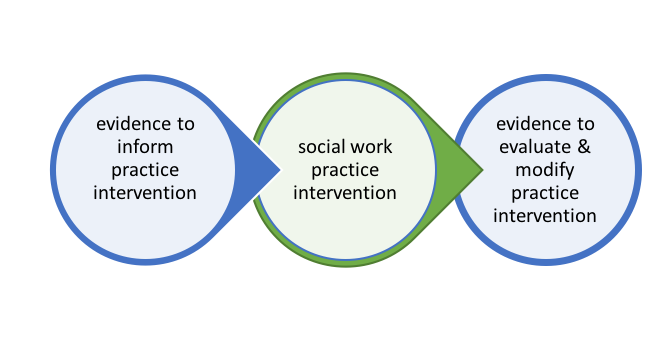

The right-hand side of the evidence-intervention-evidence figure from Chapter 1 (Figure 1-1) is the focus of this chapter.

In Chapter 2 we looked at evidence-informed practice decisions. In this chapter, we introduce information about evaluating practice, what other disciplines call data-based or data-driven decision making: using data and evaluation research methods to make social work practice accountable and to inform practice improvement efforts.

In this chapter you will learn:

- basic principles related to four evaluation formats (needs assessment, outcome, process, cost-effectiveness)

- distinctions between practice, program, and policy evaluation

- how evaluation and intervention research compare.

Why Evaluate?

In short, social work professionals engage in evaluation of practice as an accountability issue. We are accountable to clients, programs, funders, policy decision-makers, and the profession to ensure that we are delivering the best possible services, that the services we deliver achieve the promised benefits, and that the resources dedicated to our services are well-spent. This has previously been covered in our discussions regarding standards presented in the Social Work Code of Ethics. Of particular relevance to this discussion is the Standard 5.02 concerning evaluation and research (p. 27). Social workers are expected to evaluate policies, programs, and practice interventions, as well as facilitate research that contributes to the development of knowledge.

What is Evaluation?

Throughout the remainder of our course Research and Statistics for Understanding Social Work Intervention we examine methods for evaluating intervention efforts. A framework for understanding different approaches to evaluation is helpful, beginning with the nature of the evaluation research questions and exploring how these relate to different forms or approaches to evaluation.

Evaluation Questions. By now you recognize that research designs and methodologies are driven by the nature of the research questions being asked. This is equally true in the evaluation research arena. Here is a sample of the kinds of questions asked in evaluating social work practice at different levels:

- Did client behavior change to a significant degree and in the desired direction?

- Were gains associated with intervention sustained over time?

- Are there unintended negative consequences associated with the intervention?

- To what extent are principles of diversity awareness integrated into practitioner behaviors and practitioner supervision?

- How satisfied are clients with various aspects of the delivered intervention?

- Is the intervention’s cost/benefit ratio favorable compared to other intervention options?

- Are some people deriving more benefit than others from the intervention?

- Is there a more cost-efficient way to achieve similar gains from the intervention?

Evaluation Formats . Because evaluation questions differ, social workers employ varied formats for engaging in evaluation. Here is a description of four major forms of evaluation research: needs assessment, outcome evaluation, process evaluation, and cost-effectiveness evaluation.

Needs assessment. The aim of needs assessment is to answer questions related to the scope of a problem or need and where gaps exist in efforts to address the problem or need. For example, school social workers may want to know about the problem of bullying that occurs in a school district. They might engage in a needs assessment to determine the nature and extent of the problem, what is needed to eradicate the problem, and how the problem is being addressed across the district. Where they detect sizeable gaps between need and services provided, social workers can develop targeted responses. The needs assessment might also indicate that different responses need to be launched in different circumstances, such as: elementary, middle, and high school levels; or, parents, teachers, administrators, peers, and mental health professionals in the district; or, different neighborhood schools across the district. Needs assessment is often concerned with the discrepancy between what is needed and what is accessed in services, not only what is offered. As proponent of social justice, social workers are also concerned with identifying and addressing disparities (differential gaps) based on income, race/ethnicity, gender/gender identity, sexual orientation, age, national origin, symptom severity, geographical location (e.g., urban, suburban, rural disparities), and other aspects of human diversity. This represents an important extension of what you learned in our earlier course, Research and Statistics for Understanding Social Work Problems and Diverse Populations . The gap between two sides or groups is sometimes monumental.

Outcome evaluation. Evaluating practice outcomes happens at multiple levels: individual cases, programs, and policy. Social work professionals work with clients or client systems to achieve specific change goals and objectives. For example, this might be reducing a person’s alcohol consumption or tobacco use, a couple having fewer arguments, improving student attendance throughout a school, reducing violence in a community, or breaking a gender or race based “glass ceiling” in an institution. Regardless of the level of intervention, social work professionals evaluate the impact of their practices and intervention efforts. This type of research activity is called outcome evaluation. When outcome evaluation is directed to understanding the impact of practices on specific clients or client systems, it is called practice evaluation .

Evaluating the outcomes of interventions also happens at the aggregate level of programs. Social workers engaged in program evaluation look at the impact of an intervention program on the group of clients or client systems it serves. Rather than providing feedback about an individual client or client system, the feedback concerns multiple clients engaged in the intervention program. For example, social workers might wish to evaluate the extent to which child health goals (outcomes) were achieved with an intervention program for empowering parents to eliminate their young children’s exposure to third-hand smoke. The background for this work is described in an article explaining that third hand smoke is the residue remaining on skin, clothing, hair, upholstery, carpeting, and other surfaces; it differs from first- or second-hand smoke exposure because the individuals are not exposed by smoking themselves or breathing the smoke someone else produces. Young children come into close contact with contaminated surfaces when being held by caregivers, riding in vehicles, or crawling and toddling around the home where smoking has occurred, leaving residue behind (Begun, Barnhart, Gregoire, & Shepperd, 2014). Outcome oriented program evaluation would be directed toward assessing the impact of an intervention delivered to a group of parents with young children at risk of exposure to third-hand smoke at home, in transportation, from relatives, or in child care settings.

Policy evaluation has a lot in common with program evaluation, because policy is a form of intervention. Policy evaluation data are based on intervention effects experienced by many individuals, neighborhoods, communities, or programs/institutions taken together, not tracking what happens with one client system or a single program at a time. For example, communities may gather a great deal of evaluation data about the impact on drug overdose deaths related to policies supporting first-responders, family members, friends, and bystanders being able to deliver opioid overdose reversal medications (naloxone) when first encountering someone suspected of experiencing opioid overdose. “As an antidote to opioid overdoses, naloxone has proven to be a valuable tool in combating overdose deaths and associated morbidity” (Kerensky & Walley, 2017, p. 6). Policy evaluation can answer the question of how much impact such a policy change can make. Policy evaluation also answers questions such as: who should be provided with naloxone rescue kits; how naloxone rescue kit prescribing education might alter opioid prescribing behavior; whether different naloxone formulations, doses, and delivery methods provide similar results and how do their costs compare; how what happens after overdose rescue might keep people safe and link them to services to prevent future overdose events; and, how local, state, and federal laws affect this policy’s implementation (see Kerensky & Walley, 2017). These factors help determine if the impact of a policy is simply a drop in the bucket or a flood of change.

Process evaluation. Process evaluation is less concerned with questions about outcomes than with questions about how an intervention or program is implemented. Why evaluating process matters is clear if you think about fidelity examples previously discussed (e.g., the Duluth model for community response to domestic violence). Process evaluation matters in determining what practitioners really do when intervening and what clients or client systems experience during an intervention. It also matters in terms of understanding the “means to the end,” beyond simply observing the end results. Process evaluation also examines the way an intervention or program is supported by agency administrators, agency activities, and distribution of resources—the context of the intervention—and possible efficiencies or inefficiencies in how an intervention is delivered.

“Process evaluations involve monitoring and measuring variables such as communication flow, decision-making protocols, staff workload, client record keeping, program supports, staff training, and worker-client activities. Indeed, the entire sequence of activities that a program undertakes to achieve benefits for program clients or consumers is open to the scrutiny of process evaluations” (Grinell & Unrau, 2014, p. 662).

For example, despite child welfare caseworkers’ recognition of the critically important role in child development for early identification of young children’s mental health problems and needs, they also encounter difficulties that present significant barriers to effectively doing so (Hoffman et al., 2016). Through process evaluation, the investigators identified barriers that included differences in how workers and parents perceived the children’s behavioral problems, a lack of age-appropriate mental health services being available, inconsistencies with their caseworker roles and training/preparation to assess and address these problems, and a lack of standardized tools and procedures.

Cost-effectiveness evaluation. Cost-related evaluations address the relationship between resources applied through intervention and the benefits derived from that intervention. You make these kinds of decisions on a regular basis: is the pleasure derived from a certain food or beverage “worth” the cost in dollars or calories, or maybe the degree of effort involved? While costs are often related to dollars spent, relevant costs might also include a host of other resources—staff time and effort, space, training and credential requirements, other activities being curtailed, and so forth. Benefits might be measured in terms of dollars saved, but are also measured in terms of achieving goals and objectives of the intervention. In a cost-effectiveness evaluation study of Mental Health Courts conducted in Pennsylvania, diversion of individuals with serious mental illness and non-violent offenses into community-based treatment posed no increased risk to the public and reduced jail time (two significant outcomes). Overall, the “decrease in jail expenditures mostly offset the cost of the treatment services” (Psychiatric Times, 2007, p. 1)—another significant outcome. The intervention’s cost-effectiveness was greatest when offenses were at the level of a felony and for individuals with severe psychiatric disorders. While cost savings were realized by taxpayers, complicating the picture was the fact that the budget where gains were situated (criminal justice) is separate from the budget where the costs were incurred (mental health system).

How Evaluation and Intervention Research Compare

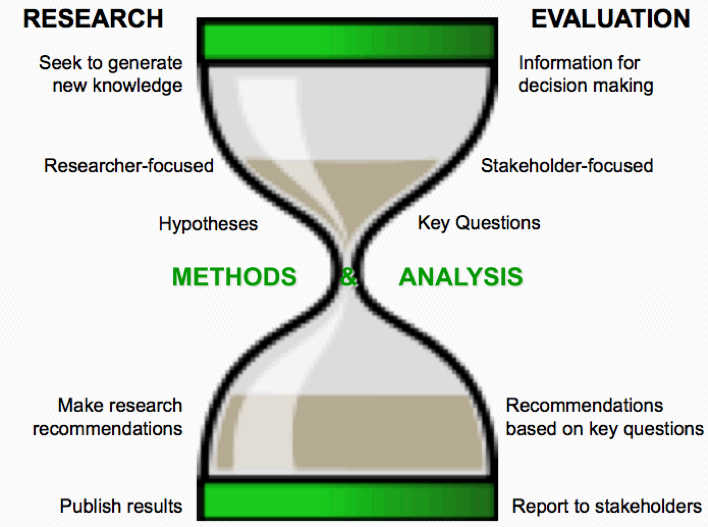

The goals, objectives, and methods of evaluation research and intervention research often appear to be very similar. In both cases, systematic research procedures are applied to answer questions about an intervention. However, there exist important differences between evaluation and research to consider, important because they have implications for how investigators and evaluators approach the pursuit of evidence.

Differences begin with the nature of the research questions being asked. Evaluation researchers pursue specific knowledge, intervention researchers pursue generalizable knowledge. In evaluation, the goal is to inform leader or administrator decisions about a program, or to inform an individual practitioner’s intervention decisions about work with specific clients. The aim of practice or program evaluation is to determine the worth of an intervention to their agency, their clients, and their stakeholders. Intervention researchers, on the other hand, have as their goal the production of knowledge or the advancing of theory for programs and practitioners more generally—not a specific program or practitioner. This difference translates into differences in how the research process is approached in evaluation compared to intervention science. Figure 3-1 depicts the differences in approach, methodology, analysis, and reporting between evaluation and intervention research (LaVelle, 2010).

Figure 3-1. Differences between intervention and evaluation research.

Take a moment to complete the following activity.

Chapter Summary

In this chapter, you were introduced to why evaluation is important in social work, extending what you learned in the prior course about the relationship of empirical evidence to social work practice. You also learned about the nature of evaluation questions and how these relate to evaluation research—an extension of what you learned in the prior course concerning the relationship between research questions and research approaches. In this chapter you were introduced to four different formats for evaluation (needs assessment, outcome evaluation, process evaluation, and cost-effectiveness evaluation), and you learned to distinguish between evaluation and intervention research.

Social Work 3402 Coursebook Copyright © by Dr. Audrey Begun is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

- Search Menu

- Advance articles

- Editor's Choice

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access

- About The British Journal of Social Work

- About the British Association of Social Workers

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

- < Previous

Social Work Research and Evaluation: Quantitative and Qualitative Approaches, Seventh Edition , Edited by Richard M. Grinnell, Jr and Yvonne A. Unrau, New York, Oxford University Press, 2005, pp. xxii + 532, ISBN 0195179498, £42.00

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Malcolm Golightley, Social Work Research and Evaluation: Quantitative and Qualitative Approaches, Seventh Edition , Edited by Richard M. Grinnell, Jr and Yvonne A. Unrau, New York, Oxford University Press, 2005, pp. xxii + 532, ISBN 0195179498, £42.00 , The British Journal of Social Work , Volume 35, Issue 4, June 2005, Pages 550–551, https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bch287

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Article PDF first page preview

Email alerts, citing articles via.

- Recommend to your Library

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1468-263X

- Print ISSN 0045-3102

- Copyright © 2024 British Association of Social Workers

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

We will keep fighting for all libraries - stand with us!

Internet Archive Audio

- This Just In

- Grateful Dead

- Old Time Radio

- 78 RPMs and Cylinder Recordings

- Audio Books & Poetry

- Computers, Technology and Science

- Music, Arts & Culture

- News & Public Affairs

- Spirituality & Religion

- Radio News Archive

- Flickr Commons

- Occupy Wall Street Flickr

- NASA Images

- Solar System Collection

- Ames Research Center

- All Software

- Old School Emulation

- MS-DOS Games

- Historical Software

- Classic PC Games

- Software Library

- Kodi Archive and Support File

- Vintage Software

- CD-ROM Software

- CD-ROM Software Library

- Software Sites

- Tucows Software Library

- Shareware CD-ROMs

- Software Capsules Compilation

- CD-ROM Images

- ZX Spectrum

- DOOM Level CD

- Smithsonian Libraries

- FEDLINK (US)

- Lincoln Collection

- American Libraries

- Canadian Libraries

- Universal Library

- Project Gutenberg

- Children's Library

- Biodiversity Heritage Library

- Books by Language

- Additional Collections

- Prelinger Archives

- Democracy Now!

- Occupy Wall Street

- TV NSA Clip Library

- Animation & Cartoons

- Arts & Music

- Computers & Technology

- Cultural & Academic Films

- Ephemeral Films

- Sports Videos

- Videogame Videos

- Youth Media

Search the history of over 866 billion web pages on the Internet.

Mobile Apps

- Wayback Machine (iOS)

- Wayback Machine (Android)

Browser Extensions

Archive-it subscription.

- Explore the Collections

- Build Collections

Save Page Now

Capture a web page as it appears now for use as a trusted citation in the future.

Please enter a valid web address

- Donate Donate icon An illustration of a heart shape

Social work research and evaluation : foundations of evidence-based practice

Bookreader item preview, share or embed this item, flag this item for.

- Graphic Violence

- Explicit Sexual Content

- Hate Speech

- Misinformation/Disinformation

- Marketing/Phishing/Advertising

- Misleading/Inaccurate/Missing Metadata

![[WorldCat (this item)] [WorldCat (this item)]](https://archive.org/images/worldcat-small.png)

plus-circle Add Review comment Reviews

23 Previews

Better World Books

DOWNLOAD OPTIONS

No suitable files to display here.

PDF access not available for this item.

IN COLLECTIONS

Uploaded by station34.cebu on March 22, 2022

SIMILAR ITEMS (based on metadata)

Social Cognitive and Addiction Neuroscience Lab at the University of Iowa

Research in the scanlab.

Research projects in the UIOWA Social Cognitive and Addiction Neuroscience Lab generally focus on one of the following areas:

The role of cognitive control in social behavior

Effects of alcohol on cognitive control

Individual differences in neurobiologically based risks for addiction, primarily alcohol use disorder

Effects of incidental stimulus exposure on cognition and behavior (i.e., priming effects).

The common theme around which these lines of work are integrated is the interplay between salience (i.e., motivational significance) and cognitive control (see Inzlicht, Bartholow, & Hirsch, 2015 ).

Salience, Cognitive Control, and Social Behavior

The interaction of salience and cognitive control is an enduring area of interest in the SCANlab, going back to Dr. Bartholow’s undergraduate days. In his undergraduate senior honors thesis, Dr. Bartholow found that participants asked to read résumés later recalled more gender-inconsistent information about job candidates. This general theme carried through to Dr. Bartholow’s dissertation research, in which he used event-related brain potentials (ERPs) to examine the neurocognitive consequences of expectancy violations. In that study, expectancy-violating behaviors elicited a larger P3-like positivity in the ERP and were recalled better compared to expectancy-consistent behaviors ( Bartholow et al., 2001 , 2003 ). Back then, we interpreted this effect as evidence for context updating (the dominant P3 theory at the time). As theoretical understanding of the P3 has evolved, we now believe this finding reflects the fact that unexpected information is salient, prompting engagement of controlled processing (see Nieuwenhuis et al., 2005 ).

Our research has been heavily influenced by cognitive neuroscience models of the structure of information processing, especially the continuous flow model ( Coles et al., 1985 ; Eriksen & Schultz, 1979) and various conflict monitoring theories (e.g., Botvinick et al., 2001 ; Shenhav et al., 2016 ). In essence, these models posit (a) that information about a stimulus accumulates gradually as processing unfolds, and (b) as a consequence, various stimulus properties or contextual features can energize multiple, often competing responses simultaneously, leading to a need to engage cognitive control to maintain adequate performance. This set of basic principles has influenced much of our research across numerous domains of interest (see Bartholow, 2010 ).

Applied to social cognition, these models imply that responses often classified as “automatic” (e.g., measures of implicit attitudes) might be influenced by control. We first tested this idea in the context of a racial categorization task in which faces were flanked by stereotype-relevant words ( Bartholow & Dickter, 2008 ). In two experiments, we found that race categorizations were faster when faces appeared with stereotype-congruent versus –incongruent words, especially when stereotype-congruent trials were more probable. Further, the ERP data showed that that this effect was not due to differences in the evaluative categorization of the faces (P3 latency), but instead reflected increased response conflict (N2 amplitude) due to partial activation of competing responses (lateralized readiness potential; LRP) on stereotype-incongruent trials. A more recent, multisite investigation (funded by the National Science Foundation ) extended this work by testing the role of executive cognitive function (EF) in the expression of implicit bias. Participants (N = 485) completed a battery of EF measures and, a week later, a battery of implicit bias measures. As predicted, we found that expression of implicit race bias was heavily influenced by individual differences in EF ability ( Ito et al., 2015 ). Specifically, the extent to which bias expression reflected automatic processes was reduced as a function of increases in general EF ability.

Another study demonstrating the role of conflict and control in “implicit” social cognition was designed to identify the locus of the affective congruency effect ( Bartholow et al., 2009 ), wherein people are faster to categorize the valence of a target if it is preceded by a valence-congruent (vs. incongruent) prime. This finding traditionally has been explained in terms of automatic spreading of activation in working memory (e.g., Fazio et al., 1986 ). By measuring ERPs while participants completed a standard evaluative priming task, we showed (a) that incongruent targets elicit response conflict; (b) that the degree of this conflict varies along with the probability of congruent targets, such that (c) when incongruent targets are highly probable, congruent targets elicit more conflict (also see Bartholow et al., 2005 ); and (d) that this conflict is localized to response generation processes, not stimulus evaluation.

Salience, Cognitive Control, and Alcohol

Drinking alcohol is inherently a social behavior. Alcohol commonly is consumed in social settings, possibly because it facilitates social bonding and group cohesion ( Sayette et al., 2012 ). Many of the most devastating negative consequences of alcohol use and chronic heavy drinking also occur in the social domain. Theorists have long posited that alcohol’s deleterious effects on social behavior stem from impaired cognitive control. Several of our experiments have shown evidence consistent with this idea, in that alcohol increases expression of race bias due to its impairment of control-related processes ( Bartholow et al., 2006 , 2012 ).

But exactly how does this occur? One answer, we believe, is that alcohol reduces the salience of events, such as a control failure (i.e., an error), that normally spur efforts at increased control. Interestingly, we found ( Bartholow et al., 2012 ) that alcohol does not reduce awareness of errors, as others had suggested ( Ridderinkhof et al., 2002 ), but rather reduces the salience or motivational significance of errors. This, in turn, hinders typical efforts at post-error control adjustment. Later work further indicated that alcohol’s control-impairing effects are limited to situations in which control has already failed, and that recovery of control following errors takes much longer when people are drunk ( Bailey et al., 2014 ). Thus, the adverse consequences people often experience when intoxicated might stem from alcohol’s dampening of the typical “affect alarm,” seated in the brain’s salience network (anterior insula and dorsal anterior cingulate cortex), which alerts us when control is failing and needs to be bolstered ( Inzlicht et al., 2015 ).

Incidental Stimulus Exposure Effects

A fundamental tenet of social psychology is that situational factors strongly affect behavior. Despite recent controversies related to some specific effects, we remain interested in the power of priming, or incidental stimulus exposure, to demonstrate this basic premise. We have studied priming effects in numerous domains, including studies showing that exposure to alcohol-related images or words can elicit behaviors often associated with alcohol consumption, such as aggression and general disinhibition.

Based on the idea that exposure to stimuli increases accessibility of relevant mental content ( Higgins, 2011 ), we reasoned that seeing alcohol-related stimuli might not only bring to mind thoughts linked in memory with alcohol, but also might instigate behaviors that often result from alcohol consumption. As an initial test of this idea, in the guise of a study on advertising effectiveness we randomly assigned participants to view magazine ads for alcoholic beverages or for other grocery items and asked them to rate the ads on various dimensions. Next, we asked participants if they would help us pilot test material for a future study on impression formation by reading a paragraph describing a person and rating him on various traits, including hostility. We reasoned that the common association between alcohol and aggression might lead to a sort of hostile perception bias when evaluating this individual. As predicted, participants who had seen ads for alcohol rated the individual as more hostile than did participants who had seen ads for other products, and this effect was larger among people who had endorsed (weeks previously) the notion that alcohol increases aggression ( Bartholow & Heinz, 2006 ). Subsequently, this finding has been extended to participants’ own aggression in verbal ( Friedman et al., 2007 ) and physical domains ( Pedersen et al., 2014 ), and has been replicated in other labs (e.g., Bègue et al., 2009 ; Subra et al., 2010 ).

Of course, aggression is not the only behavior commonly assumed to increase with alcohol. Hence, we have tested whether this basic phenomenon extends into other behavioral domains, and found similar effects with social disinhibition ( Freeman et al., 2010 ), tension-reduction (Friedman et al., 2007), race bias ( Stepanova et al., 2012 , 2018 a, 2018 b), and risky decision-making (Carter et al., in prep.). Additionally, it could be that participants are savvy enough to recognize the hypotheses in studies of this kind when alcohol-related stimuli are presented overtly (i.e., experimental demand). Thus, we have also tested the generality of the effect by varying alcohol cue exposure procedures, including the use of so-called “sub-optimal” exposures (i.e., when prime stimuli are presented too quickly to be consciously recognized). Here again, similar effects have emerged (e.g., Friedman et al., 2007; Loersch & Bartholow, 2011 ; Pedersen et al., 2014).

Taken together, these findings highlight the power of situational cues to affect behavior in theoretically meaningful ways. On a practical level, they point to the conclusion that alcohol can affect social behavior even when it is not consumed, suggesting, ironically, that even nondrinkers can experience its effects.

Aberrant Salience and Control as Risk Factors for Addiction

Salience is central to a prominent theory of addiction known as incentive sensitization theory (IST; e.g., Robinson & Berridge, 1993 ). Briefly, IST posits that, through use of addictive drugs, including alcohol, people learn to pair the rewarding feelings they experience (relaxation, stimulation) with various cues present during drug use. Eventually, repeated pairing of drug-related cues with reward leads those cues to take on the rewarding properties of the drug itself. That is, the cues become infused with incentive salience, triggering craving, approach and consummatory behavior.

Research has shown critical individual differences in vulnerability to attributing incentive salience to drug cues, and that vulnerable individuals are at much higher risk for addiction. Moreover, combining incentive sensitization with poor cognitive control (e.g., during a drinking episode) makes for a “potentially disastrous combination” ( Robinson & Berridge, 2003 , p. 44). To date, IST has been tested primarily in preclinical animal models. Part of our work aims to translate IST to a human model.

In a number of studies over the past decade, we have discovered that a low sensitivity to the effects of alcohol (i.e., needing more drinks to feel alcohol’s effects), known to be a potent risk factor for alcoholism, is associated with heightened incentive salience for alcohol cues. Compared with their higher-sensitivity (HS) peers, among low-sensitivity (LS) drinkers alcohol-related cues (a) elicit much larger neurophysiological responses ( Bartholow et al., 2007 , 2010 ; Fleming & Bartholow, in prep.); (b) capture selective attention ( Shin et al., 2010 ); (c) trigger approach-motivated behavior ( Fleming & Bartholow, 2014 ); (d) produce response conflict when relevant behaviors must be inhibited or overridden by alternative responses ( Bailey & Bartholow, 2016 ; Fleming & Bartholow, 2014), and (e) elicit greater feelings of craving (Fleming & Bartholow, in prep.; Piasecki et al., 2017 ; Trela et al., in press). These findings suggest that LS could be a human phenotype related to sign-tracking , a conditioned response reflecting susceptibility to incentive sensitization and addiction ( Robinson et al., 2014 ).

Recently, our lab has conducted two major projects designed to examine how the incentive salience of alcohol-related cues is associated with underage drinking. One such project, funded by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA; R01-AA020970 ), examined the extent to which pairing beer brands with major U.S. universities enhances the incentive salience of those brands for underage students. Major brewers routinely associate their brands with U.S. universities through direct marketing and by advertising during university-related programming (e.g., college sports). We tested whether affiliating a beer brand with students’ university increases the incentive salience of the brand, and whether individual differences in the magnitude of this effect predict changes in underage students’ alcohol use. We found (a) that P3 amplitude elicited by a beer brand increased when that brand was affiliated with students’ university, either in a contrived laboratory task or by ads presented during university-related sports broadcasts; (b) that stronger personal identification with the university increased this effect; and (c) that variability in this effect predicted changes in alcohol use over one month, controlling for baseline levels of use ( Bartholow et al., 2018 ).

A current project, also funded by the NIAAA ( R01-AA025451 ), aims to connect multiple laboratory-based measures of the incentive salience of alcohol-related cues to underage drinkers’ reports of craving, alcohol use, and alcohol-related consequences as they occur in their natural environments. This project will help us to better understand the extent to which changes in drinking lead to changes in alcohol sensitivity and to corresponding changes in the incentive salience of alcohol-related cues.

Can self-testing be enhanced to hasten safe return of healthcare workers in pandemics? Random order, open label trial using two manufacturers' SARS-CoV-2 lateral flow devices concurrently

- Find this author on Google Scholar

- Find this author on PubMed

- Search for this author on this site

- ORCID record for Xingna Zhang

- ORCID record for Christopher P Cheyne

- ORCID record for Chrisopher Jones

- ORCID record for Michael Humann

- ORCID record for Gary Leeming

- ORCID record for Claire Smith

- ORCID record for David M Hughes

- ORCID record for Girvan Burnside

- ORCID record for Susanna Dodd

- ORCID record for Rebekah Penrice-Randal

- ORCID record for Xiaofeng Dong

- ORCID record for Malcolm G Semple

- ORCID record for Tim Neal

- ORCID record for Sarah Tunkel

- ORCID record for Tom Fowler

- ORCID record for Lance Turtle

- ORCID record for Marta Garcia-Finana

- ORCID record for Iain E Buchan

- For correspondence: [email protected]

- Info/History

- Supplementary material

- Preview PDF

Background Covid-19 healthcare worker testing, isolation and quarantine policies had to balance risks to patients from the virus and from staff absence. The emergence of the Omicron variant led to dangerous levels of key-worker absence globally. We evaluated whether using two manufacturers' lateral flow tests (LFTs) concurrently improved SARS-CoV-2 Omicron detection and was acceptable to hospital staff. In a nested study, to understand risks of return to work after a 5-day isolation/quarantine period, we examined virus culture 5-7 days after positive test or significant exposure. Methods Fully-vaccinated Liverpool (UK) University Hospitals staff participated (February-May 2022) in a random-order, open-label trial testing whether dual LFTs improved SARS-CoV2 detection, and whether dual swabbing was acceptable to users. Participants used nose-throat swab Innova and nose-only swab Orient Gene LFTs in daily randomised order for 10 days. A user-experience questionnaire was administered on exit. Selected participants gave swabs for viral culture on Days 5-7. Cultures were considered positive if cytopathic effect was apparent or SARs-COV2 N gene sub-genomic RNA was detected. Results 226 individuals reported 1466 pairs of LFT results. Tests disagreed in 127 cases (8.7%). Orient Gene was more likely (78 cf. 49, P=0.03) to be positive. Orient Gene positive Innova negative result-pairs became more frequent over time (P<0.001). If Innova was swabbed second, it was less likely to agree with a positive Orient Gene result (P=0.005); swabbing first with Innova made no significant difference (P=0.85). Of 311 individuals completing the exit questionnaire, 90.7% reported dual swabbing was easy, 57.1% said it was no barrier to their daily routine and 65.6% preferred dual testing. Respondents had more confidence in dual c.f. single test results (P<0.001). Viral cultures from Days 5-7 were positive for 6/31 (19.4%, 7.5%-37.5%) and indeterminate for 11/31 (35.5%, 19.2%-54.6%) LFT-positive participants, indicating they were likely still infectious. Conclusions Dual brand testing increased LFT detection of SARS-CoV-2 antigen by a small but meaningful margin and was acceptable to hospital workers. Viral cultures demonstrated that policies recommending safe return to work ~5 days after Omicron infection/exposure were flawed. Key-workers should be prepared for dynamic self-testing protocols in future pandemics.

Competing Interest Statement

All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at https://www.icmje.org/disclosure-of-interest and declare: funding from the Department of Health and Social Care, Economic and Social Research Council, and National Institute for Health and Care Research; no support from any organisation for the submitted work; no financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work. IB, TF and MGS were members of the UK Covid-19 Testing Initiatives Evaluation Board but did not take part in sessions where this study was adjudicated. The City of Liverpool received a donation from Innova Medical Group towards the foundation of the Pandemic Institute but neither Innova Medical Group or any other commercial entity gave any support to this study or had any participation in it. Lateral Flow Test supply and company interactions was handled independently by the UK Health Security Agency. LT has received consulting fees from MHRA; and from AstraZeneca and Synairgen, paid to the University of Liverpool; speakers' fees from Eisai Ltd, and support for conference attendance from AstraZeneca.

Clinical Trial

ISRCTN47058442

Clinical Protocols

https://github.com/iain-buchan/cipha/blob/master/SMART_Release_Return.pdf

Funding Statement

This research was commissioned and funded by the UK Health Security Agency and carried out independently by the University of Liverpool. The work was also supported by the Economic and Social Research Council (grant No ES/L011840/1). IB is supported by the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) as senior investigator award NIHR205131. IB and XZ are also supported by the NIHR Health Protection Research Unit in Gastrointestinal Infections, a partnership between UKHSA, the University of Liverpool, and the University of Warwick (NIHR200910). MGS and LT are supported by the NIHR Health Protection Unit in Emerging and Zoonotic Infections, a partnership between UKHSA, The University of Liverpool and The University of Oxford (NIHR200907). The NIHR had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the article. LT, RPR and XD are supported by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration Medical Countermeasures Initiative contract 75F40120C00085. The funders had no role in considering the study design or in the collection, analysis, or interpretation of data, writing of the report, or decision to submit the article for publication. The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the National Health Service, NIHR, or Department of Health and Social Care.

Author Declarations

I confirm all relevant ethical guidelines have been followed, and any necessary IRB and/or ethics committee approvals have been obtained.

The details of the IRB/oversight body that provided approval or exemption for the research described are given below:

The study protocol was developed with the UK Covid-19 Testing Initiatives Evaluation Board (TIEB) and approved by UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA) Urgent Studies Ethics Committee. TIEB was part of the UK Covid-19 testing initiatives evaluation programme, which included academics and public health professionals independent of this study. The motivation for the study came from a request by Merseyside Resilience Forum to UKHSA and NHS England to vary Covid-19 testing policies in response to dangerous levels of NHS staff absence in December 2021. TIEB signed off the study protocol on 4th January 2022 and UKHSA Research Support and Governance Office approved the study on 25th January 2022 as NR0308. The sponsor code for this study is UoL001685 and trial registration code IRAS ID 311842; https://www.isrctn.com/ ISRCTN47058442 .

I confirm that all necessary patient/participant consent has been obtained and the appropriate institutional forms have been archived, and that any patient/participant/sample identifiers included were not known to anyone (e.g., hospital staff, patients or participants themselves) outside the research group so cannot be used to identify individuals.

I understand that all clinical trials and any other prospective interventional studies must be registered with an ICMJE-approved registry, such as ClinicalTrials.gov. I confirm that any such study reported in the manuscript has been registered and the trial registration ID is provided (note: if posting a prospective study registered retrospectively, please provide a statement in the trial ID field explaining why the study was not registered in advance).

I have followed all appropriate research reporting guidelines, such as any relevant EQUATOR Network research reporting checklist(s) and other pertinent material, if applicable.

Expanded discussion section with a conclusion paragraph. Restructured abstract. Expanded data availability statement to include recent upload of anonymised study data to trials registration site. No differences in results or interpretation from the original version.

Data Availability

The study required person identifiable data and the main analyses were conducted on a de-identified extract. The fully anonymised data for reproducing the results are available from https://www.isrctn.com/ ISRCTN47058442 . The study protocol can be downloaded from https://github.com/iain-buchan/cipha/blob/master/SMART_Release_Return.pdf and statistical analysis plan from https://github.com/iain-buchan/cipha/blob/master/SMART_RR_SAP.pdf.

https://www.isrctn.com/ISRCTN47058442

View the discussion thread.

Supplementary Material

Thank you for your interest in spreading the word about medRxiv.

NOTE: Your email address is requested solely to identify you as the sender of this article.

Citation Manager Formats

- EndNote (tagged)

- EndNote 8 (xml)

- RefWorks Tagged

- Ref Manager

- Tweet Widget

- Facebook Like

- Google Plus One

- Addiction Medicine (324)

- Allergy and Immunology (628)

- Anesthesia (165)

- Cardiovascular Medicine (2383)

- Dentistry and Oral Medicine (289)

- Dermatology (207)

- Emergency Medicine (380)

- Endocrinology (including Diabetes Mellitus and Metabolic Disease) (839)

- Epidemiology (11777)

- Forensic Medicine (10)

- Gastroenterology (703)

- Genetic and Genomic Medicine (3751)

- Geriatric Medicine (350)

- Health Economics (635)

- Health Informatics (2401)

- Health Policy (935)

- Health Systems and Quality Improvement (900)

- Hematology (341)

- HIV/AIDS (782)

- Infectious Diseases (except HIV/AIDS) (13323)

- Intensive Care and Critical Care Medicine (769)

- Medical Education (366)

- Medical Ethics (105)

- Nephrology (398)

- Neurology (3513)

- Nursing (198)

- Nutrition (528)

- Obstetrics and Gynecology (675)

- Occupational and Environmental Health (665)

- Oncology (1825)

- Ophthalmology (538)

- Orthopedics (219)

- Otolaryngology (287)

- Pain Medicine (233)

- Palliative Medicine (66)

- Pathology (446)

- Pediatrics (1035)

- Pharmacology and Therapeutics (426)

- Primary Care Research (422)

- Psychiatry and Clinical Psychology (3181)

- Public and Global Health (6150)

- Radiology and Imaging (1281)

- Rehabilitation Medicine and Physical Therapy (749)

- Respiratory Medicine (828)

- Rheumatology (379)

- Sexual and Reproductive Health (372)

- Sports Medicine (323)

- Surgery (402)

- Toxicology (50)

- Transplantation (172)

- Urology (146)

A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

A lock ( ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- About Violence Prevention

- Resources for Action

- Cardiff Model

Violence Prevention

About The Public Health Approach to Violence Prevention

Violence Topics

About Adverse Childhood Experiences

About Child Abuse and Neglect

About Community Violence

About Firearm Injury and Death

About Intimate Partner Violence

About Sexual Violence

About Youth Violence

About Abuse of Older Persons

About Violence Against Children and Youth Surveys

About The National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey (NISVS)

About The National Violent Death Reporting System (NVDRS)

Featured Resources

Essentials for Parenting Teens

Essentials for Parenting Toddlers and Preschoolers

Cardiff Violence Prevention Model Toolkit

Violence is an urgent public health problem. CDC is committed to preventing violence so that everyone can be safe and healthy.

COMMENTS

Social Work Research and Evaluation: Foundations of Evidence-Based Practice $104.43 Only 11 left in stock - order soon. Over thirty years of input from instructors and students have gone into this popular research methods text, resulting in a refined ninth edition that is easier to read, understand, and apply than ever before.

Evaluation research is a part of all social workers' toolkits. It ensures that social work interventions achieve their intended effects. This protects our clients and ensures that money and other resources are not spent on programs that do not work. Evaluation research uses the skills of quantitative and qualitative research to ensure clients ...

Social Work Research and Evaluation. (1983) Curriculum Policy Statement emphasized the integration of research and practice. In 1988, the CSWE Curriculum Policy Statement was revised to indicate the curriculum should impart knowledge for practice and eval-uation of services (Commission on Accreditation, 1988).

Since the first edition in 1981, Social Work Research and Evaluation has provided graduate-level social work students with basic research and evaluation concepts to help them become successful evidence-based practitioners, evidence-informed practitioners, and practitioners who are implementing evidence-based programs. Students will gain a thorough understanding and appreciation for how the ...

Over thirty years of input from instructors and students have gone into this popular research methods text, resulting in a refined ninth edition that is easier to read, understand, and apply than ever before. Using unintimidating language and real-world examples, it introduces students to the key concepts of evidence-based practice that they will use throughout their professional careers.

Social Work Research and Evaluation applies systematically developed research knowledge to social work practice and emphasizes the "doing" of social work as a reciprocal avenue for generating research evidence and social work knowledge.Using the Examined Practice Model, authors Elizabeth G. DePoy and Stephen F. Gilson present research as the identification of a problem and then proceed to ...

Since the first edition in 1981, Social Work Research and Evaluation has provided graduate-level social work students with basic research and evaluation concepts to help them become successful evidence-based practitioners, evidence-informed practitioners, and practitioners who are implementing evidence-based programs. Students will gain a thorough understanding and appreciation for how the ...

This book is the longest standing and most widely adopted text in the field of social work research and evaluation. Since the first edition in 1981, it has been designed to provide beginning social work students the basic methodological foundation they need in order to successfully complete more advanced research courses that focus on single-system designs or program evaluations.

This book is the longest-standing text in the field of social work research and evaluation. Since the first edition in 1981, it has been designed to provide beginning graduate social work students the basic methodological foundation they need in order to successfully complete more advanced research courses that focus on single-system designs or program evaluations.

Since the first edition in 1981, Social Work Research and Evaluation has provided graduate-level social work students with basic research and evaluation concepts to help them become successful evidence-based practitioners, evidence-informed practitioners and practitioners who are implementing evidence-based programs. Students will gain a thorough understanding and appreciation for how the ...

Source Definition; Suchman (1968, pp. 2-3) [Evaluation applies] the methods of science to action programs in order to obtain objective and valid measures of what such programs are accomplishing.…Evaluation research asks about the kinds of change desired, the means by which this change is to be brought about, and the signs by which such changes can be recognized.

5.02 Evaluation and Research Overview Revisions to section 5 of the NASW Code of Ethics, which focuses on social workers' responsibilities to the social work profession, were limited to standard 5.02, Evaluation and Research.There are now 16 standards in this section with the inclusion of new content that specifically incorporates guidance for social workers using electronic technology in ...

This represents an important extension of what you learned in our earlier course, Research and Statistics for Understanding Social Work Problems and Diverse Populations. The gap between two sides or groups is sometimes monumental. Outcome evaluation. Evaluating practice outcomes happens at multiple levels: individual cases, programs, and policy.

Social work research and evaluation by Grinnell, Richard M. Publication date 1993 Topics Social service -- Research, Service social -- Recherche Publisher ... Openlibrary_work OL3365144W Page_number_confidence 91.21 Pages 514 Ppi 300 Rcs_key 24143 Republisher_date 20200312134357 ...

Social Work Research and Evaluation: Foundations of Evidence-based Practice. Richard M. Grinnell, Yvonne A. Unrau. Oxford University Press, 2008 - Political Science - 610 pages. This book is the longest standing and most widely adopted text in the field of social work research and evaluation. As stated in the book's preface, it is intended for ...

Malcolm Golightley, Social Work Research and Evaluation: Quantitative and Qualitative Approaches, Seventh Edition, Edited by Richard M. Grinnell, Jr and Yvonne A. Unrau, New York, Oxford University Press, 2005, pp. xxii + 532, ISBN 0195179498, £42.00, The British Journal of Social Work, Volume 35, Issue 4, June 2005, Pages 550-551, https ...

Since the first edition in 1981,Social Work Research and Evaluation has provided graduate-level social work students with basic research and evaluation concepts to help them become successful evidence-based practitioners, evidence-informed practitioners and practitioners who are implementing evidence-based programs. Students will gain a thorough understanding and appreciation for how the three ...

Reviews the book, Social Work Research and Evaluation: Quantitative and Qualitative Approaches edited by Richard M. Grinnell Jr. and Yvonne A. Unrau (2005). This book examines the basic tenets of quantitative and qualitative research methods with the aim of preparing practitioners for "becoming beginning critical consumers of the professional research literature." This textbook is broad in ...

Rev. ed. of: Social work research & evaluation. 5th ed. c1997 Includes bibliographical references (p. 553-571) and index Notes. cut text on some pages due tight binding. Access-restricted-item true Addeddate 2022-07-31 07:01:06 Associated-names Grinnell, Richard M. Social work research & evaluation ...

Social service -- Research, Evaluation research (Social action programs), Evidence-based social work Publisher New York : Oxford University Press Collection inlibrary; printdisabled; internetarchivebooks Contributor Internet Archive Language English

Salience, Cognitive Control, and Social Behavior. The interaction of salience and cognitive control is an enduring area of interest in the SCANlab, going back to Dr. Bartholow's undergraduate days.In his undergraduate senior honors thesis, Dr. Bartholow found that participants asked to read résumés later recalled more gender-inconsistent information about job candidates.

Books. Social Work Research and Evaluation: Quantitative and Qualitative Approaches. Richard M. Grinnell, Yvonne A. Unrau. Oxford University Press, 2005 - Political Science - 532 pages. This book is the longest standing and most widely adopted text in the field of social work research and evaluation. Since the first edition in 1981, it has been ...

The work was also supported by the Economic and Social Research Council (grant No ES/L011840/1). ... TIEB was part of the UK Covid-19 testing initiatives evaluation programme, which included academics and public health professionals independent of this study. ... The work was also supported by the Economic and Social Research Council (grant No ...

Strengths and challenges identified through the Evaluation Readiness Assessment, the Evaluation Design and Implementation Assessment, and the cohort content and coaching received; Capstone projects each state team plans to implement (e.g., customized Evaluation Action Plan, research design for a specific project, statement of work for ...

This page features all of CDC's violence prevention-related information.

The role of research and evaluation in the field of social work has changed significantly since the 1970s. Practicing social workers are increasingly expected to be able to evaluate a client's progress and to research established methods for dealing with particular issues. moreover, groundbreaking research is no longer the exclusive preserve of academics or professional researchers.