- More from M-W

- To save this word, you'll need to log in. Log In

Definition of thesis

Did you know.

In high school, college, or graduate school, students often have to write a thesis on a topic in their major field of study. In many fields, a final thesis is the biggest challenge involved in getting a master's degree, and the same is true for students studying for a Ph.D. (a Ph.D. thesis is often called a dissertation ). But a thesis may also be an idea; so in the course of the paper the student may put forth several theses (notice the plural form) and attempt to prove them.

Examples of thesis in a Sentence

These examples are programmatically compiled from various online sources to illustrate current usage of the word 'thesis.' Any opinions expressed in the examples do not represent those of Merriam-Webster or its editors. Send us feedback about these examples.

Word History

in sense 3, Middle English, lowering of the voice, from Late Latin & Greek; Late Latin, from Greek, downbeat, more important part of a foot, literally, act of laying down; in other senses, Latin, from Greek, literally, act of laying down, from tithenai to put, lay down — more at do

14th century, in the meaning defined at sense 3a(1)

Dictionary Entries Near thesis

the sins of the fathers are visited upon the children

thesis novel

Cite this Entry

“Thesis.” Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary , Merriam-Webster, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/thesis. Accessed 19 May. 2024.

Kids Definition

Kids definition of thesis, more from merriam-webster on thesis.

Nglish: Translation of thesis for Spanish Speakers

Britannica English: Translation of thesis for Arabic Speakers

Britannica.com: Encyclopedia article about thesis

Subscribe to America's largest dictionary and get thousands more definitions and advanced search—ad free!

Can you solve 4 words at once?

Word of the day.

See Definitions and Examples »

Get Word of the Day daily email!

Popular in Grammar & Usage

More commonly misspelled words, your vs. you're: how to use them correctly, every letter is silent, sometimes: a-z list of examples, more commonly mispronounced words, how to use em dashes (—), en dashes (–) , and hyphens (-), popular in wordplay, the words of the week - may 17, birds say the darndest things, a great big list of bread words, 10 scrabble words without any vowels, 12 more bird names that sound like insults (and sometimes are), games & quizzes.

- Cambridge Dictionary +Plus

Meaning of thesis in English

Your browser doesn't support HTML5 audio

- I wrote my thesis on literacy strategies for boys .

- Her main thesis is that children need a lot of verbal stimulation .

- boilerplate

- composition

- dissertation

- essay question

- peer review

You can also find related words, phrases, and synonyms in the topics:

thesis | Intermediate English

Examples of thesis, collocations with thesis.

These are words often used in combination with thesis .

Click on a collocation to see more examples of it.

Translations of thesis

Get a quick, free translation!

Word of the Day

a computer program designed to have a conversation with a human being, usually over the internet

Searching out and tracking down: talking about finding or discovering things

Learn more with +Plus

- Recent and Recommended {{#preferredDictionaries}} {{name}} {{/preferredDictionaries}}

- Definitions Clear explanations of natural written and spoken English English Learner’s Dictionary Essential British English Essential American English

- Grammar and thesaurus Usage explanations of natural written and spoken English Grammar Thesaurus

- Pronunciation British and American pronunciations with audio English Pronunciation

- English–Chinese (Simplified) Chinese (Simplified)–English

- English–Chinese (Traditional) Chinese (Traditional)–English

- English–Dutch Dutch–English

- English–French French–English

- English–German German–English

- English–Indonesian Indonesian–English

- English–Italian Italian–English

- English–Japanese Japanese–English

- English–Norwegian Norwegian–English

- English–Polish Polish–English

- English–Portuguese Portuguese–English

- English–Spanish Spanish–English

- English–Swedish Swedish–English

- Dictionary +Plus Word Lists

- English Noun

- Intermediate Noun

- Collocations

- Translations

- All translations

To add thesis to a word list please sign up or log in.

Add thesis to one of your lists below, or create a new one.

{{message}}

Something went wrong.

There was a problem sending your report.

- Dictionaries home

- American English

- Collocations

- German-English

- Grammar home

- Practical English Usage

- Learn & Practise Grammar (Beta)

- Word Lists home

- My Word Lists

- Recent additions

- Resources home

- Text Checker

NEW words and meanings added: March 2024

Game on or game over ?

With the Summer Olympics coming up, the main focus for our latest release is on the world of sport.

Worrying about your team’s back four in the relegation six-pointer ? Did one of your team’s blueliners just score an empty-netter ? Or maybe you prefer T20™ , with the drama of one-dayers and super overs , or just like to pay your green fee and get started on the front nine ?

We’ve added over 170 new words and meanings from sport and other topics.

Our word lists are designed to help learners at any level focus on the most important words to learn.

Explore our general English and academic English lists.

Spread the Word

A recent addition to our online dictionary is the term culture war , which is used to describe the conflict between groups of people with different ideals and beliefs.

Topic Dictionaries

Our Topic Dictionaries are lists of topic-related words, like Animals and Health , that can help you expand your vocabulary. Each topic is divided into smaller subtopics and every word has a CEFR level.

Learn & Practise Grammar

Our grammar pages combine clear explanations with interactive exercises to test your understanding.

Learn more with these dictionary and grammar resources

We offer a number of premium products on this website to help you improve your english..

JOIN our community of language learners!

Connect with us TODAY to start receiving the language learning and assessment resources you need directly to your newsfeed and inbox.

Writing a Thesis or Dissertation

A course for students who are either writing, or preparing to write, a dissertation or thesis for their degree course at oxford, intensive course timetable: trinity term 2024.

Enrolment will close at 12 noon on Thursday of Week 8 of term (13 June 2024).

To ensure that we have time to set you up with access to our Virtual Learning Environment (Canvas), please make sure you have enrolled and paid no later than five working days before your course starts.

MT = Michaelmas Term (October - December); HT = Hilary Term (January - March); TT = Trinity Term (April-June)

Course Timetable: Trinity Term 2024

Enrolment will close at 12 noon on Wednesday of Week 1 of term (24 January 2024).

Course overview

This course is designed for students who are either writing, or preparing to write, a dissertation or thesis for their degree course at Oxford. Each lesson focuses on a different part of the thesis/dissertation/articles (Introductions, Literature Reviews, Discussions etc.), as well as the expected structure and linguistic conventions. Building upon the foundational understanding provided by our other Academic English courses (particularly Introduction to Academic Writing and Grammar, and Key Issues), this course prepares students for the challenges of organising, writing and revising a thesis or dissertation.

Learning outcomes

- Gain an understanding of the different organisational structures used within Humanities, Social Sciences and Natural Sciences dissertations and theses

- Consider works of previous Oxford students in order to understand the common structural, linguistic and stylistic issues that arise when drafting a research project

- Increase competence in incorporating citations into texts, including choosing appropriate tenses and reporting verbs

- Learn how to structure the various parts of a dissertation or thesis (Introduction, Literature Review, Discussion, Conclusion and Abstract)

Enrolment information

For Learners with an Oxford University SSO (Single Sign-On) simply click on the enrol button next to the class that you wish to join.

For Learners without an Oxford University SSO, or who are not members of the University, once enrolment opens , please email [email protected] with the following details:

- Email address and phone number

- The name of the course you wish to study

- The start date and time of the course

- Your connection to Oxford University, if any (to determine course fee)

We will then provisionally enrol you onto the course and send you a link to the Oxford University Online Store for payment. Once payment is received we will confirm your place on the course. Please note that we will be unable to assist you until enrolment has opened, so please do not send us your enrolment details in advance.

Course structure

- Taught in Weeks 2-8 of term

- Seminars per week: 1

- Length of seminar: 2 hours

- Academic English tutor will provide all materials

Intensive course structure

- One week intensive course

- Taught in week 9 of term (Monday - Friday)

- Number of classes throughout the week: 5

- Length of class: 2-3 hours

- Total hours of tuition over the week: 14

Course fees

VIEW THE COURSE FEES

Join our mailing lists

ACADEMIC ENGLISH

MODERN LANGUAGES

Other Term-time Courses

Theses and dissertations

Read our guidance for finding and accessing theses and dissertations held by the Bodleian Libraries and other institutions.

- Subscriber Services

- For Authors

- Publications

- Archaeology

- Art & Architecture

- Bilingual dictionaries

- Classical studies

- Encyclopedias

- English Dictionaries and Thesauri

- Language reference

- Linguistics

- Media studies

- Medicine and health

- Names studies

- Performing arts

- Science and technology

- Social sciences

- Society and culture

- Overview Pages

- Subject Reference

- English Dictionaries

- Bilingual Dictionaries

Recently viewed (0)

- Save Search

- Find at OUP.com

- Google Preview

The New Oxford Dictionary for Scientific Writers and Editors (2 ed.)

Elizabeth martin.

This dictionary provides scientists, science writers, and all who work in scientific publishing with a clear style guide for the presentation of scientific information. In over 9,700 entries, it reflects widely accepted usage and follows the recommendations of international scientific bodies such as IUPAC and IUPAP. The dictionary gives clear guidance on such matters as spellings (American English and British English), punctuation, abbreviations, prefixes and suffixes, units and quantities, and symbols.

Revised and fully updated, this new edition of the Oxford Dictionary for Scientific Writers and Editors includes feature entries on key areas, substantially increased coverage of the life sciences, and new entries in physics, astronomy, chemistry, computer science, and mathematics. New and revised appendices also provide useful supplementary tables including SI units, mathematical symbols, the electromagnetic spectrum, and useful online resources.

This comprehensive and authoritative A-Z guide is an invaluable tool for students, professionals, and publishers working with writing in the fields of physics, chemistry, botany, zoology, biochemistry, genetics, immunology, microbiology, astronomy, mathematics, and computer science.

Bibliographic Information

Affiliations are at time of print publication..

Elizabeth Martin, author

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

- All Contents

Access to the complete content on Oxford Reference requires a subscription or purchase. Public users are able to search the site and view the abstracts and keywords for each book and chapter without a subscription.

Please subscribe or login to access full text content.

If you have purchased a print title that contains an access token, please see the token for information about how to register your code.

For questions on access or troubleshooting, please check our FAQs , and if you can''t find the answer there, please contact us .

Front Matter

Publishing information, general links for this work, contributors and advisers, note on proprietary status, the electromagnetic spectrum, graphical symbols used in electronics, letter symbols used in electronics, the geological time scale, mathematical symbols, the periodic table, the greek alphabet, resources for naming genes, british/american spelling differences, chemical elements.

- Oxford University Press

PRINTED FROM OXFORD REFERENCE (www.oxfordreference.com). (c) Copyright Oxford University Press, 2023. All Rights Reserved. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a PDF of a single entry from a reference work in OR for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice ).

date: 19 May 2024

- Cookie Policy

- Privacy Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

- [66.249.64.20|185.66.15.189]

- 185.66.15.189

Character limit 500 /500

Information about what plagiarism is, and how you can avoid it.

The University defines plagiarism as follows:

“Presenting work or ideas from another source as your own, with or without consent of the original author, by incorporating it into your work without full acknowledgement. All published and unpublished material, whether in manuscript, printed or electronic form, is covered under this definition, as is the use of material generated wholly or in part through use of artificial intelligence (save when use of AI for assessment has received prior authorisation e.g. as a reasonable adjustment for a student’s disability). Plagiarism can also include re-using your own work without citation. Under the regulations for examinations, intentional or reckless plagiarism is a disciplinary offence.”

The necessity to acknowledge others’ work or ideas applies not only to text, but also to other media, such as computer code, illustrations, graphs etc. It applies equally to published text and data drawn from books and journals, and to unpublished text and data, whether from lectures, theses or other students’ essays. You must also attribute text, data, or other resources downloaded from websites.

Please note that artificial intelligence (AI) can only be used within assessments where specific prior authorisation has been given, or when technology that uses AI has been agreed as reasonable adjustment for a student’s disability (such as voice recognition software for transcriptions, or spelling and grammar checkers).

The best way of avoiding plagiarism is to learn and employ the principles of good academic practice from the beginning of your university career. Avoiding plagiarism is not simply a matter of making sure your references are all correct, or changing enough words so the examiner will not notice your paraphrase; it is about deploying your academic skills to make your work as good as it can be.

Students will benefit from taking an online course which has been developed to provide a useful overview of the issues surrounding plagiarism and practical ways to avoid it.

Forms of plagiarism

Verbatim (word for word) quotation without clear acknowledgement Quotations must always be identified as such by the use of either quotation marks or indentation, and with full referencing of the sources cited. It must always be apparent to the reader which parts are your own independent work and where you have drawn on ideas and language from another source.

Cutting and pasting from the Internet without clear acknowledgement Information derived from the Internet must be adequately referenced and included in the bibliography. It is important to evaluate carefully all material found on the Internet, as it is less likely to have been through the same process of scholarly peer review as published sources.

Paraphrasing Paraphrasing the work of others by altering a few words and changing their order, or by closely following the structure of their argument, is plagiarism if you do not give due acknowledgement to the author whose work you are using.

A passing reference to the original author in your own text may not be enough; you must ensure that you do not create the misleading impression that the paraphrased wording or the sequence of ideas are entirely your own. It is better to write a brief summary of the author’s overall argument in your own words, indicating that you are doing so, than to paraphrase particular sections of his or her writing. This will ensure you have a genuine grasp of the argument and will avoid the difficulty of paraphrasing without plagiarising. You must also properly attribute all material you derive from lectures.

Collusion This can involve unauthorised collaboration between students, failure to attribute assistance received, or failure to follow precisely regulations on group work projects. It is your responsibility to ensure that you are entirely clear about the extent of collaboration permitted, and which parts of the work must be your own.

Inaccurate citation It is important to cite correctly, according to the conventions of your discipline. As well as listing your sources (i.e. in a bibliography), you must indicate, using a footnote or an in-text reference, where a quoted passage comes from. Additionally, you should not include anything in your references or bibliography that you have not actually consulted. If you cannot gain access to a primary source you must make it clear in your citation that your knowledge of the work has been derived from a secondary text (for example, Bradshaw, D. Title of Book, discussed in Wilson, E., Title of Book (London, 2004), p. 189).

Failure to acknowledge assistance You must clearly acknowledge all assistance which has contributed to the production of your work, such as advice from fellow students, laboratory technicians, and other external sources. This need not apply to the assistance provided by your tutor or supervisor, or to ordinary proofreading, but it is necessary to acknowledge other guidance which leads to substantive changes of content or approach.

Use of material written by professional agencies or other persons You should neither make use of professional agencies in the production of your work nor submit material which has been written for you even with the consent of the person who has written it. It is vital to your intellectual training and development that you should undertake the research process unaided. Under Statute XI on University Discipline, all members of the University are prohibited from providing material that could be submitted in an examination by students at this University or elsewhere.

Auto-plagiarism You must not submit work for assessment that you have already submitted (partially or in full), either for your current course or for another qualification of this, or any other, university, unless this is specifically provided for in the special regulations for your course. Where earlier work by you is citable, ie. it has already been published, you must reference it clearly. Identical pieces of work submitted concurrently will also be considered to be auto-plagiarism.

Why does plagiarism matter?

Plagiarism is a breach of academic integrity. It is a principle of intellectual honesty that all members of the academic community should acknowledge their debt to the originators of the ideas, words, and data which form the basis for their own work. Passing off another’s work as your own is not only poor scholarship, but also means that you have failed to complete the learning process. Plagiarism is unethical and can have serious consequences for your future career; it also undermines the standards of your institution and of the degrees it issues.

Why should you avoid plagiarism?

There are many reasons to avoid plagiarism. You have come to university to learn to know and speak your own mind, not merely to reproduce the opinions of others - at least not without attribution. At first it may seem very difficult to develop your own views, and you will probably find yourself paraphrasing the writings of others as you attempt to understand and assimilate their arguments. However it is important that you learn to develop your own voice. You are not necessarily expected to become an original thinker, but you are expected to be an independent one - by learning to assess critically the work of others, weigh up differing arguments and draw your own conclusions. Students who plagiarise undermine the ethos of academic scholarship while avoiding an essential part of the learning process.

You should avoid plagiarism because you aspire to produce work of the highest quality. Once you have grasped the principles of source use and citation, you should find it relatively straightforward to steer clear of plagiarism. Moreover, you will reap the additional benefits of improvements to both the lucidity and quality of your writing. It is important to appreciate that mastery of the techniques of academic writing is not merely a practical skill, but one that lends both credibility and authority to your work, and demonstrates your commitment to the principle of intellectual honesty in scholarship.

What happens if you are thought to have plagiarised?

The University regards plagiarism in examinations as a serious matter. Cases will be investigated and penalties may range from deduction of marks to expulsion from the University, depending on the seriousness of the occurrence. Even if plagiarism is inadvertent, it can result in a penalty. The forms of plagiarism listed above are all potentially disciplinary offences in the context of formal assessment requirements.

The regulations regarding conduct in examinations apply equally to the ‘submission and assessment of a thesis, dissertation, essay, or other coursework not undertaken in formal examination conditions but which counts towards or constitutes the work for a degree or other academic award’. Additionally, this includes the transfer and confirmation of status exercises undertaken by graduate students. Cases of suspected plagiarism in assessed work are investigated under the disciplinary regulations concerning conduct in examinations. Intentional plagiarism in this context means that you understood that you were breaching the regulations and did so intending to gain advantage in the examination. Reckless, in this context, means that you understood or could be expected to have understood (even if you did not specifically consider it) that your work might breach the regulations, but you took no action to avoid doing so. Intentional or reckless plagiarism may incur severe penalties, including failure of your degree or expulsion from the university.

If plagiarism is suspected in a piece of work submitted for assessment in an examination, the matter will be referred to the Proctors. They will thoroughly investigate the claim and call the student concerned for interview. If at this point there is no evidence of a breach of the regulations, no further disciplinary action will be taken although there may still be an academic penalty. However, if it is concluded that a breach of the regulations may have occurred, the Proctors will refer the case to the Student Disciplinary Panel.

If you are suspected of plagiarism your College Secretary/Academic Administrator and subject tutor will support you through the process and arrange for a member of Congregation to accompany you to all hearings. They will be able to advise you what to expect during the investigation and how best to make your case. The OUSU Student Advice Service can also provide useful information and support.

Does this mean that I shouldn’t use the work of other authors?

On the contrary, it is vital that you situate your writing within the intellectual debates of your discipline. Academic essays almost always involve the use and discussion of material written by others, and, with due acknowledgement and proper referencing, this is clearly distinguishable from plagiarism. The knowledge in your discipline has developed cumulatively as a result of years of research, innovation and debate. You need to give credit to the authors of the ideas and observations you cite. Not only does this accord recognition to their work, it also helps you to strengthen your argument by making clear the basis on which you make it. Moreover, good citation practice gives your reader the opportunity to follow up your references, or check the validity of your interpretation.

Does every statement in my essay have to be backed up with references?

You may feel that including the citation for every point you make will interrupt the flow of your essay and make it look very unoriginal. At least initially, this may sometimes be inevitable. However, by employing good citation practice from the start, you will learn to avoid errors such as close paraphrasing or inadequately referenced quotation. It is important to understand the reasons behind the need for transparency of source use.

All academic texts, even student essays, are multi-voiced, which means they are filled with references to other texts. Rather than attempting to synthesise these voices into one narrative account, you should make it clear whose interpretation or argument you are employing at any one time - whose ‘voice’ is speaking.

If you are substantially indebted to a particular argument in the formulation of your own, you should make this clear both in footnotes and in the body of your text according to the agreed conventions of the discipline, before going on to describe how your own views develop or diverge from this influence.

On the other hand, it is not necessary to give references for facts that are common knowledge in your discipline. If you are unsure as to whether something is considered to be common knowledge or not, it is safer to cite it anyway and seek clarification. You do need to document facts that are not generally known and ideas that are interpretations of facts.

Does this only matter in exams?

Although plagiarism in weekly essays does not constitute a University disciplinary offence, it may well lead to College disciplinary measures. Persistent academic under-performance can even result in your being sent down from the University. Although tutorial essays traditionally do not require the full scholarly apparatus of footnotes and referencing, it is still necessary to acknowledge your sources and demonstrate the development of your argument, usually by an in-text reference. Many tutors will ask that you do employ a formal citation style early on, and you will find that this is good preparation for later project and dissertation work. In any case, your work will benefit considerably if you adopt good scholarly habits from the start, together with the techniques of critical thinking and writing described above.

As junior members of the academic community, students need to learn how to read academic literature and how to write in a style appropriate to their discipline. This does not mean that you must become masters of jargon and obfuscation; however the process is akin to learning a new language. It is necessary not only to learn new terminology, but the practical study skills and other techniques which will help you to learn effectively.

Developing these skills throughout your time at university will not only help you to produce better coursework, dissertations, projects and exam papers, but will lay the intellectual foundations for your future career. Even if you have no intention of becoming an academic, being able to analyse evidence, exercise critical judgement, and write clearly and persuasively are skills that will serve you for life, and which any employer will value.

Borrowing essays from other students to adapt and submit as your own is plagiarism, and will develop none of these necessary skills, holding back your academic development. Students who lend essays for this purpose are doing their peers no favours.

Unintentional plagiarism

Not all cases of plagiarism arise from a deliberate intention to cheat. Sometimes students may omit to take down citation details when taking notes, or they may be genuinely ignorant of referencing conventions. However, these excuses offer no sure protection against a charge of plagiarism. Even in cases where the plagiarism is found to have been neither intentional nor reckless, there may still be an academic penalty for poor practice.

It is your responsibility to find out the prevailing referencing conventions in your discipline, to take adequate notes, and to avoid close paraphrasing. If you are offered induction sessions on plagiarism and study skills, you should attend. Together with the advice contained in your subject handbook, these will help you learn how to avoid common errors. If you are undertaking a project or dissertation you should ensure that you have information on plagiarism and collusion. If ever in doubt about referencing, paraphrasing or plagiarism, you have only to ask your tutor.

Examples of plagiarism

There are some helpful examples of plagiarism-by-paraphrase and you will also find extensive advice on the referencing and library skills pages.

The following examples demonstrate some of the common pitfalls to avoid. These examples use the referencing system prescribed by the History Faculty but should be of use to students of all disciplines.

Source text

From a class perspective this put them [highwaymen] in an ambivalent position. In aspiring to that proud, if temporary, status of ‘Gentleman of the Road’, they did not question the inegalitarian hierarchy of their society. Yet their boldness of act and deed, in putting them outside the law as rebellious fugitives, revivified the ‘animal spirits’ of capitalism and became an essential part of the oppositional culture of working-class London, a serious obstacle to the formation of a tractable, obedient labour force. Therefore, it was not enough to hang them – the values they espoused or represented had to be challenged.

(Linebaugh, P., The London Hanged: Crime and Civil Society in the Eighteenth Century (London, 1991), p. 213. [You should give the reference in full the first time you use it in a footnote; thereafter it is acceptable to use an abbreviated version, e.g. Linebaugh, The London Hanged, p. 213.]

Plagiarised

- Although they did not question the inegalitarian hierarchy of their society, highwaymen became an essential part of the oppositional culture of working-class London, posing a serious threat to the formation of a biddable labour force. (This is a patchwork of phrases copied verbatim from the source, with just a few words changed here and there. There is no reference to the original author and no indication that these words are not the writer’s own.)

- Although they did not question the inegalitarian hierarchy of their society, highwaymen exercised a powerful attraction for the working classes. Some historians believe that this hindered the development of a submissive workforce. (This is a mixture of verbatim copying and acceptable paraphrase. Although only one phrase has been copied from the source, this would still count as plagiarism. The idea expressed in the first sentence has not been attributed at all, and the reference to ‘some historians’ in the second is insufficient. The writer should use clear referencing to acknowledge all ideas taken from other people’s work.)

- Although they did not question the inegalitarian hierarchy of their society, highwaymen ‘became an essential part of the oppositional culture of working-class London [and] a serious obstacle to the formation of a tractable, obedient labour force’.1 (This contains a mixture of attributed and unattributed quotation, which suggests to the reader that the first line is original to this writer. All quoted material must be enclosed in quotation marks and adequately referenced.)

- Highwaymen’s bold deeds ‘revivified the “animal spirits” of capitalism’ and made them an essential part of the oppositional culture of working-class London.1 Peter Linebaugh argues that they posed a major obstacle to the formation of an obedient labour force. (Although the most striking phrase has been placed within quotation marks and correctly referenced, and the original author is referred to in the text, there has been a great deal of unacknowledged borrowing. This should have been put into the writer’s own words instead.)

- By aspiring to the title of ‘Gentleman of the Road’, highwaymen did not challenge the unfair taxonomy of their society. Yet their daring exploits made them into outlaws and inspired the antagonistic culture of labouring London, forming a grave impediment to the development of a submissive workforce. Ultimately, hanging them was insufficient – the ideals they personified had to be discredited.1 (This may seem acceptable on a superficial level, but by imitating exactly the structure of the original passage and using synonyms for almost every word, the writer has paraphrased too closely. The reference to the original author does not make it clear how extensive the borrowing has been. Instead, the writer should try to express the argument in his or her own words, rather than relying on a ‘translation’ of the original.)

Non-plagiarised

- Peter Linebaugh argues that although highwaymen posed no overt challenge to social orthodoxy – they aspired to be known as ‘Gentlemen of the Road’ – they were often seen as anti-hero role models by the unruly working classes. He concludes that they were executed not only for their criminal acts, but in order to stamp out the threat of insubordinacy.1 (This paraphrase of the passage is acceptable as the wording and structure demonstrate the reader’s interpretation of the passage and do not follow the original too closely. The source of the ideas under discussion has been properly attributed in both textual and footnote references.)

- Peter Linebaugh argues that highwaymen represented a powerful challenge to the mores of capitalist society and inspired the rebelliousness of London’s working class.1 (This is a brief summary of the argument with appropriate attribution.) 1 Linebaugh, P., The London Hanged: Crime and Civil Society in the Eighteenth Century (London, 1991), p. 213.

Systems & Services

Access Student Self Service

- Student Self Service

- Self Service guide

- Registration guide

- Libraries search

- OXCORT - see TMS

- GSS - see Student Self Service

- The Careers Service

- Oxford University Sport

- Online store

- Gardens, Libraries and Museums

- Researchers Skills Toolkit

- LinkedIn Learning (formerly Lynda.com)

- Access Guide

- Lecture Lists

- Exam Papers (OXAM)

- Oxford Talks

Latest student news

CAN'T FIND WHAT YOU'RE LOOKING FOR?

Try our extensive database of FAQs or submit your own question...

Ask a question

Covid–19 Library update

Important changes to our services. find out more, q. how do i reference a dictionary definition.

- 5 Access to the Library

- 3 Accessibility

- 319 Databases - more information

- 18 How to find?

- 10 Journals, newspapers and magazines.

- 1 Laptop loans

- 1 Library account

- 26 Library databases

- 11 Library study spaces

- 5 LinkedIn Learning course videos

- 29 Logging in

- 28 MMU Harvard

- 6 Need some help?

- 1 Photocopying

- 1 Reading lists

- 39 Referencing

- 1 Research data management

- 1 Research Gate

- 2 Reservations

- 7 RSC Referencing

- 4 Software IT

- 4 WGSN database

Answered By: Gopal Dutta Last Updated: Sep 23, 2021 Views: 50274

You do not always need to cite and reference a dictionary definition. Whether you need to or not will depend on the type of dictionary and/or how you are using the definition in your work. Language dictionaries As you are not using the words, ideas or theory of an author, you do not usually need to cite and reference a language dictionary (for example the Oxford English dictionary). Instead, introduce the definition in your writing. One way to present this is as follows: According to the Oxford English Dictionary the definition of [XXXXX] is [XXXXXX] If however you have a particular need in your work to cite a language dictionary definition, for example, if comparing varying definitions from language dictionaries by different publishers, follow the format as follows. The example provided is for an online dictionary, therefore 'online' is used in the citation in place of the page number.

Example citation

(Oxford English Dictionary, 2016:online)

If you are going to refer to the Oxford English Dictionary again in your work, introduce the acronym OED in your citation as follows

(Oxford English Dictionary [OED], 2016:online)

Oxford English Dictionary. (2016) reference, v. 3 . Oxford: Oxford University. [Online] [Accessed on 10th February 2017] http://www.oed.com/view/Entry/160845

Subject dictionaries and encyclopedias As subject dictionaries and encyclopedias are usually written by a specific author/s or organisation, and contextual definitions are provided, you will need to cite and reference them in the usual way.

Many subject dictionaries and encyclopedias, are edited books with entries written by different authors. In this instance follow the format for referencing a Chapter in an edited book

Example reference

Muncie, J. (2001) 'Labelling.' In McLaughlin, E. and Muncie, J. (eds.) The SAGE dictionary of criminology . London: SAGE, pp. 159-160.

- Share on Facebook

Was this helpful? Yes 33 No 23

Related Topics

- Referencing

- MMU Harvard

- © 2022 Manchester Metropolitan University

- Library privacy notice

- Freedom of Information

- Accessibility

Home › Study Tips › How To Cite The Oxford English Dictionary: Using MLA And APA

How To Cite The Oxford English Dictionary: Using MLA And APA

- Published June 2, 2022

Table of Contents

Writing academic essays and research papers can be more complex than it already is when you don’t know how to cite the Oxford English Dictionary (OED).

It becomes even more confusing depending on what type of OED you’re using, online or print. Why? Because you cite them in different ways. You can now rest easy since you’ve come to the right place. Read more if you want to learn how to cite the Oxford English Dictionary.

And, if you’re looking to get ahead of your competition in education, then browse our summer programs in Oxford for high school students .

MLA or APA?

The first step to citing any reference is to figure out what style you need to follow: MLA or APA? What’s the difference, you ask?

Good question!

The most significant is that MLA (Modern Language Association) is used for arts and humanities while APA (American Psychology Association) is for social science. Once you determine which style you need to use, you’re on your way to writing an academic essay !

How To Cite The Oxford English Dictionary Using MLA 9th Edition

Library database, known author.

If you’re accessing the Oxford English Dictionary via a library database and you know who the author is, this is how you cite it.

Author’s Last Name, First Name. “Title of Entry.” Title of Encyclopedia or Dictionary , edited by Editor’s First Name Last Name, Edition if given and not first edition, vol. Volume Number if more than one volume, Publisher Name, Date of Publication, pp. First Page-Last Page. Name of Database . https://doi.org/DOI if there is one.

If the word you’re referencing is only found on one page, list it as such—no need to write it as a first page-last page. But if there’s no page number, you can choose to omit it. What if you don’t know who the editors are or what volume it is? You can also leave them out of your citation.

In-Text Citation:

(Author’s Last Name, page number)

If the page number is unavailable:

(Author’s Last Name)

Unknown Author

What if you don’t know who the author is? Here’s how to cite your entry.

“Title of Entry.” Title of Encyclopedia or Dictionary , edited by Editor’s First Name Last Name, Edition if given and not first edition, vol. Volume Number, Publisher Name, Date of Publication, pp. First Page-Last Page. Name of Database . https://doi.org/DOI if there is one.

What if you don’t have specific information such as pages volume numbers and editors? You don’t have to include them.

Since you don’t know the author, you need to input the first one to three words from the entry title. Please remember to enclose the title within quotation marks. Also, don’t forget to capitalise the first letter of each word. Just like this:

(“Diversity”)

Perhaps the easiest way to access the Oxford English Dictionary is through their various websites. If you know the author, here’s how to cite it:

Author’s Last Name, First Name. “Title of Entry.” Title of Encyclopedia or Dictionary , Publication or Update Date, URL. Accessed Day Month Year site was visited.

Did you notice that “Accessed Day Month Year site was visited” is unique to website citations? If you’re wondering, it simply refers to the day you visited the website. Also, don’t forget to abbreviate the month for the publication/update date and the accessed date; it’s necessary to abbreviate the month.

If you don’t know who the author is, you can cite your entry this way:

“Title of Entry.” Title of Encyclopedia or Dictionary , Publisher if known, Copyright Date or Date Updated, URL. Accessed Day Month Year site was visited.

With the lack of author information, all you have to do is place the first one to three words of the entry title within quotation marks. Remember to capitalise the first letter of each term. Here’s how:

(“Victorian”)

Of course, we can’t forget physical Oxford English Dictionaries! If you intend to use one, here’s how you can cite the material:

Author’s Last Name, First Name. “Title of Entry.” Title of Encyclopedia or Dictionary, edited by Editor’s First Name Last Name, Edition if given and not first edition, vol. Volume Number, Publisher Name, Year of Publication, pp. First Page-Last Page.

In case the author’s name is not provided, just the editors’, cite it this way:

“Title of Entry.” Title of Encyclopedia or Dictionary , edited by Editor’s First Name Last Name, Edition if given and not first edition, vol. Volume Number, Publisher Name, Year of Publication, pp. First Page-Last Page.

Since there’s no author information available, you can use the first one to three words of the entry title and enclose it with quotation marks. Capitalise the first letter of each word. Then place the page number after. Take a look at this:

(“Middle Age” 545)

How To Cite Two Authors

How should you cite the material if there are two authors? By listing them how they appear on the page. Not alphabetically!

First Author’s Last Name, First Author’s First Name, and First Name Last Name of Second Author

Here’s what it will look like:

Will, Thomas, and Melissa Jones

How To Cite More Than Two Authors

If there are more than two authors, what you need to do is to focus on the first author in the list.

Last Name, First Name, et al.

In actual practice, it will look like this:

Will, Thomas, et al.

How To Cite The Oxford English Dictionary Using APA 7th Edition

The APA style is more straightforward than the MLA. When citing authors, remember it’s only the last name that’s spelt out. The first name is abbreviated. If the author’s name is Melissa Jones, the citation will look like this:

Jones, M.

If the author’s middle name is given, for instance, Melissa Smith Jones, here’s how to cite it.

Jones, M.S.

When referencing the Oxford English Dictionary you find online, determine if it’s an archived version or not. If not, it means that the dictionary is continuously being updated.

Online Archived Version:

Author A. A. (Date). Title of entry. In E. E. Editor (Ed.), Name of dictionary/encyclopedia . URL.

Online Version With Continuous Updates:

Author A. A. (n.d.). Title of entry. In E. E. Editor (Ed.), Name of dictionary/encyclopedia (edition, if not the first). Publisher. URL.

No Authors, But There Are Editors:

Editor, A., & Editor, B. (Eds.). (Date). Dictionary/Encyclopedia entry. In Name of dictionary/encyclopedia (edition, if not the first). Publisher.

No Authors And No Editors: Use Company As Corporate Author

Corporate Author. (Date). Dictionary/Encyclopedia entry. In Name of dictionary/encyclopedia (edition, if not the first). Publisher.

In-Text Citation

(Author’s last name, date)

Wrapping Up

There you have it! By now you know how to cite the Oxford English Dictionary using both the MLA and APA styles. You’ll be more confident writing your papers from now on.

Related Content

How is san francisco shaping the future of data ai.

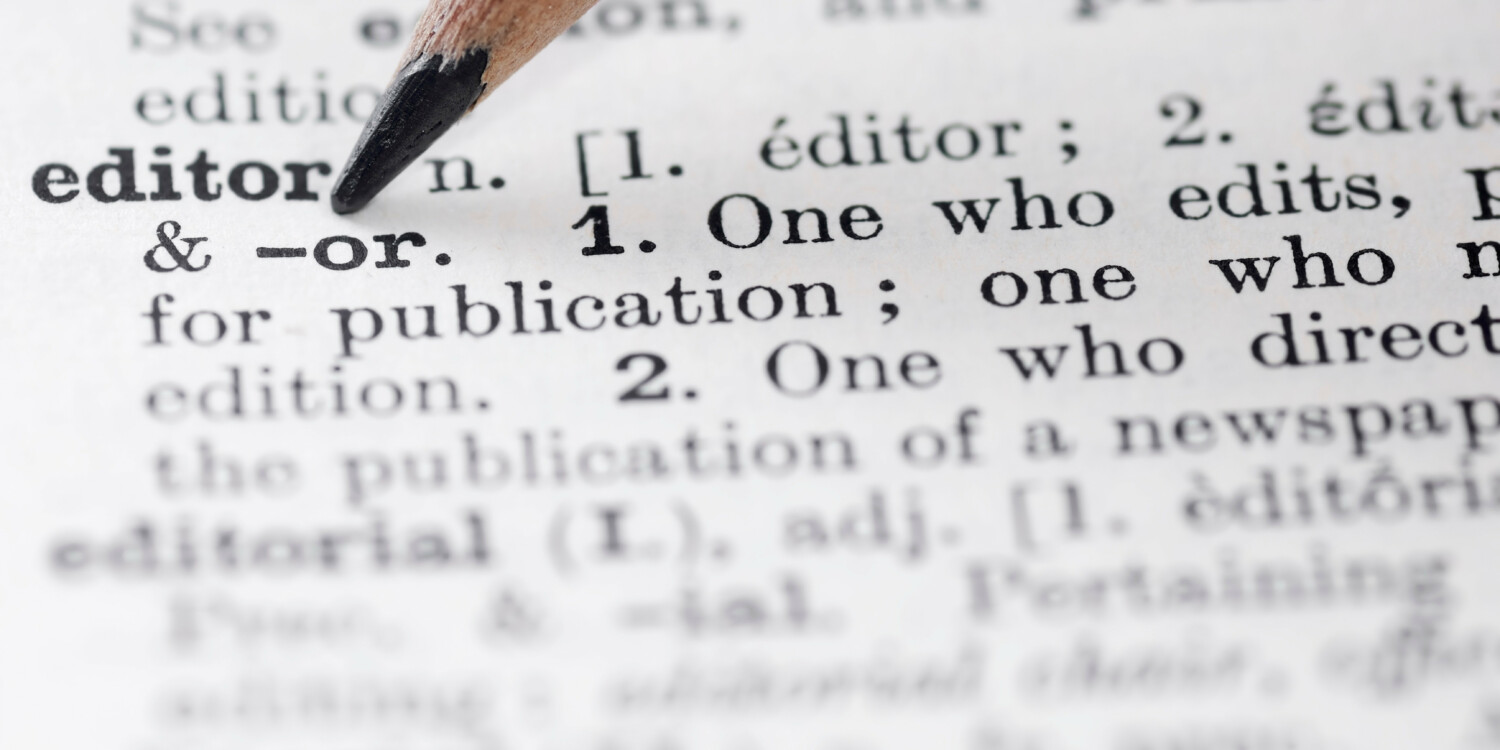

The People Who Created Our Dictionary Have Been Largely Forgotten—Until Now

I t was in a hidden corner of the Oxford University Press basement, where the Dictionary’s archive is stored, that I opened a dusty box and came across a small black book tied with cream ribbon. That basement archive is, strangely perhaps, one of my favourite places in the world: silent, cold, musty-smelling; rows of movable steel shelves on rollers; brown acid-free boxes bulging with letters; millions of slips of paper tied in bundles with twine; and Dictionary proofs covered in small, precise handwriting. It is a place full of friendly, word-nerd, ghosts. Perhaps those ghosts were guiding me because the discovery I made that day would lead me on an extraordinary journey and eventually to the book you are now holding.

I was there out of nostalgia more than anything. I used to work upstairs as an editor on the Oxford English Dictionary (OED) and I was filling in time while waiting for my visa to come through for a new job in America. It was Friday, and I had spent the whole week revisiting my favourite spots before leaving the city that had been my home for fourteen years.

Monday had been a walk around the deer park within the walls of Magdalen College. C. S. Lewis had said that the circular path was the perfect length for any problem. It was true. The fritillaria weren’t in flower, but the trees were yellow and the leaves on the ground were damp and smelled of the earth. Next, noisy Longwall Street and past the dirty windows of where I used to live at number 13. Through a heavy gate and an arch in the old city wall and into the vast gardens of New College with its immaculate lawn and long border still in colour. The bells rang as I paused at the spot under the oak where the college cat, Montgomery, had been buried by the chaplain. Along the gravel path by the purple echinops, crimson dahlias, and red echinacea with their pom-pom centres. Through the grand gates of the old quad, and into the silence of the cloisters where they had filmed Harry Potter . I pushed open the door of the chapel and was immediately hit by the comforting smell of beeswax and the sound of the choirboys rehearsing. I stayed in the antechapel and sat in front of Epstein’s Lazarus rising out of the tomb and spinning free of his bandages. Tuesday was the Upper Reading Room of the Bodleian Library. Wednesday was the secret bench against the President’s wall at Trinity College where I used to worry about my thesis. Thursday was Wolvercote Cemetery and the resting place of my hero James Murray, the longest-serving Editor of the Oxford English Dictionary from 1879 up to his death in 1915.

The Dictionary had started out with three men, Richard Chenevix Trench (1807–86), the Dean of Westminster Abbey, along with Herbert Coleridge (1830–61) and Frederick Fur- nivall (1825–1910), both lawyers turned literary scholars, who suggested the creation of a new dictionary. This would be the first dictionary that described language. Until then, the major English dictionaries such as Dr Samuel Johnson’s in the eighteenth century were prescriptive texts – telling their readers what words should mean and how they should be spelled, pronounced, and used. In 1857, these men proposed to the London Philological Society – one of the scholarly societies that were such a hallmark of their day – the creation of ‘an entirely new Dictionary; no patch upon old garments, but a new garment throughout’. Coleridge became the first Editor of the New English Dictionary (as the OED was first called), but he died two years into the job. Frederick Furnivall took over for twenty years, until he was replaced in 1879 by a schoolmaster in London called James Augustus Henry Murray (1837–1915).

Before moving to Oxford, Murray tried to combine teaching at Mill Hill School with work on the Dictionary. The Dictionary won out. It was at Mill Hill that Murray had started to compile the Dictionary inside his house, but the vast quantities of books and slips threatened to crowd out his growing family (in time, he and his wife Ada would have eleven children). Ada eventually put her foot down, insisting that he build an iron shed in the garden and use that as his office; it was nicknamed the Scriptorium. When Murray moved to Oxford in 1884 to work solely on the Dictionary, his family and the Scriptorium went with him. It was partially dug into the ground, so Murray and his small team of editors laboured on the Dictionary for the next thirty years in dank and cold conditions, often wrapping their legs in newspaper to stay warm. Over the years, he was helped by paid editorial assistants and joined by three key editors who subsequently became Chief Editors in their own right: Henry Bradley, William Craigie, and Charles Onions.

The new Dictionary would trace the meaning of words across time and describe how people were actually using them. The founders, however, were smart enough to recognize that the mammoth task of finding words in their natural habitat and describing them in such a rigorous way could never be done alone by a small group of men in London or Oxford. The OED was the Wikipedia of the nineteenth century – a huge crowdsourcing project in which, over seventy years between 1858 and 1928, members of the public were invited to read the books that they had to hand, and to mail to the Editor of the Dictionary examples of how particular words were used in those books. The volunteer ‘Readers’ were instructed to write out the words and sentences on small 4 x 6-inch pieces of paper, known as ‘slips’. In addition to being Readers, volunteers could help as Subeditors who received bundles of slips for pre-sorting (chronologically and into senses of meaning); and as Specialists who provided advice on the etymologies, meaning, and usage of certain words. Most people worked for free but a few were paid, and the editorial assistants formed two groups – one under the leadership of Murray in the Scriptorium and the other managed by Henry Bradley at the Old Ashmolean building in the centre of Oxford.

In the first twenty years, this system of crowdsourcing enlisted the help of several hundred helpers. It expanded considerably under James Murray, who sent out a global appeal for people to read their local texts and send in their local words. It was important for Murray that everyone adhere strictly to scientific principles of historical lexicography and find the very first use of a word. Readers received a list of twelve instructions on how to select a word, which included, ‘Give the date of your book (if you can), author, title (short). Give an exact reference, such as seems to you to be the best to enable anyone to verify your quotations. Make a quotation for every word that strikes you as rare, obsolete, old-fashioned, new, peculiar, or used in a peculiar way.’ He distributed the appeal to newspapers and journals, schools, universities, and hundreds of clubs and societies throughout Britain, America, and the rest of the world. The response was massive. In order to cope with the volume of post arriving in Oxford, the Royal Mail installed a red pillar box outside Dr Murray’s house at 78 Banbury Road to receive post (it is still there today). This is now one of the most gentrified areas of Oxford, full of large three-storey, redbrick, Victorian houses, but the houses were brand new when Murray lived there and considered quite far out of town. He devised a system of storage for all the slips in shelves of pigeonholes that lined the walls of the Scriptorium.

We know some of the contributors’ names from brief mentions in the prefaces to the Dictionary that accompanied each portion (called a ‘fascicle’) as it was gradually published between 1884 and 1928. Other historical documents, such as Murray’s presidential addresses to the London Philological Society, also mention groups of contributors: some are famous, some ordinary, and some unpredictable – perhaps most notoriously the murderer and prisoner William Chester Minor, so brilliantly depicted by Simon Winchester in The Surgeon of Crowthorne (1998). Through these sources, historians have thought that there were hundreds of contributors, but have not known who they all were.

Today, crowdsourcing happens at extraordinary speed, scale, and scope thanks to the internet. In the mid-nineteenth century, the launch of ‘uniform penny post’ and the birth of steam power (driving printing presses, and leading to railway transport and faster ocean crossings) enabled this system of reading for the Dictionary to be so successful. The growth of the British Empire, the proliferation of clubs and societies, and the professionalization of scholarship throughout the century all conspired to create the conditions for a global, shared, intellectual project that continues to this day.

The OED is now on its third edition, and still makes appeals and invites contributions from the public (via its website), but is chiefly revised by a team of specialized lexicographers. As one of those lexicographers, my job was to edit the words that had originally come from languages out- side Europe – words from Arabic ( sugar , sofa , magazine ) or Hindi ( shampoo , chutney , bungalow ) or Nahuatl ( chocolate , avo cado , chilli ) – in the third edition. Apart from the use of computers, the editing process I followed was exactly the same as that masterminded by Murray: each lexicographer was given a box of slips corresponding to our respective portion of the alphabet and, aided by large digital datasets, we worked through slip by slip, word by word, striving to piece together fragments of an incomplete historical record, until we had crafted an entry and presented a logical chain of semantic development in much the same way that Murray and his editors had. We also worked in a silent zone, just as it was in the nineteenth century. It has relaxed a bit now and editors work in small groups, but when I first started there if you wanted to speak to a colleague you were encouraged to whisper or to go into a meeting room to do so.

It was only natural that on my final day in Oxford I should want to bid farewell to the Dictionary Archives, where I had spent so many happy hours in the past. On that cool autumn Friday in 2014, when I casually popped by to pass some time, I could not have imagined what I was about to discover.

I collected my visitor’s badge from the reception and made my way along multiple corridors, down some stairs, along a tunnel. I had walked this way many times because I had also written my doctorate on the OED using historical materials stored down there. As a previous employee, I have always been granted exceptional access to the stacks. One last swipe and a loud click, and I was inside the inner sanctum of the archives. Bev and Martin greeted me; I passed through another door into the OED section of boxes and paraphernalia. It was the material relating to the first edition of the OED which drew me. It was a treasure trove. You could pick any box and it held something of interest.

I don’t even remember what was written on the one that I pulled off the shelf, but I noticed that it was lighter than the others. I placed it on the floor and lifted the lid. There, right on top, was a black book I had never seen before, bound with cream ribbon.

I carefully picked it up and removed the ribbon that held the stiff black covers together, and looked more closely. It was the size of an average exercise book; the spine had disintegrated to reveal fine cotton binding; the pages were discoloured at the edges, slightly foxed. When I opened it, the first thing that struck me was the immaculate cursive handwriting. I recognized it as the familiar hand of James Murray. He had written the names and addresses of not just hundreds but thousands of people who had volunteered to contribute to the Dictionary.

Finding Dr Murray’s address book was one of those moments when everything goes into slow motion. I immediately appreciated the significance of the find. I realized I held a key to understanding how the greatest English dictionary in the world was made: not only who the volunteers were, where they lived, what they read, but so many other personal details that Murray often included on their deaths, marriages, and friendships.

I was stunned by the sheer numbers of people who had contributed. Murray had not only listed the names and addresses of his contributors but had meticulously recorded every book title they had read, with the number of slips they sent in, and the dates received. Every page was filled with black ink: names, addresses, and titles of books with numbers beside them, small symbols and notes, ticks and checks, stars and scribbles.

I wondered whether I was the first person to open the address book since Murray had last used it. Had it remained closed for almost a century? Not quite: there was an archival classification number written in pencil at the top of one of the pages, and I knew that the dictionary archive had been re-organized and categorized by the Dictionary’s wonderful archivist, Bev. However, I was familiar with the books and articles written about the OED over recent decades, and I knew that it was likely that no one else had seen Murray’s address book or, if they had, they had not deemed it valuable. I was the first person to take this opportunity to track down who the contributors really were, and to build as comprehensive a picture as possible. I had found the Dictionary People.

The box in the archives held two further address books belonging to Murray, and the following summer, in a box in the Bodleian Library, I found another three address books belonging to the Editor who had preceded him, Frederick Furnivall. As I worked my way through them, it became clear that there were thousands of contributors. Some three thousand, to be exact.

The address books provided me with the kind of research project that scholars can only dream of. My excitement was followed by long, hard detective work. My visa came through and with the help of a team of tech-savvy student research assistants at Stanford (where I was by then teaching) I used the information from six address books (Murray’s and Furnivall’s) to create two large datasets of the thousands of Dictionary People and the tens of thousands of books that they read. In tracking contributors across the world, I visited libraries, archives, and personal collections in Oxford, Cambridge, London, New York, California, Scotland, and Australia. I also gathered portraits and digital photographs of the contributors, scanned hundreds of letters and slips showing the handwriting of the contributors, as well as great lists of the words and quotations they collected.

Murray’s address books were clearly the work of an obsessive. Piecing together the stories of the Dictionary People from his brief and often cryptic notes required a similar focus. Some pages held original letters from the addressees, and almost every page contained signs that needed decoding. What did Murray mean by D4, D6, a tilde accent, or a U with a cross through it? It took me a while to work those out, while others I immediately grasped – ‘11/2/85’ clearly meant 11 February 1885. Some people in the address books had cryptic marks and ideographs above their names. Others had not-so-subtle descriptors: ‘dead’, ‘died’, ‘gone away’, ‘gave up’, ‘nothing done’, ‘threw up’, ‘no good’. I sat with the books and studied their pages, and other patterns emerged. Some names were underlined in bright red pencil, and gradually I realized this meant they were Americans, while others were crossed out in blue pencil with the letters ‘I-M-P-O-S-T-O-R’ written over them.

For the past eight years I have pored over these address books, researching the people listed inside them – where they lived, what they did with their lives, who they loved, the books they read, and the words they contributed to the Dictionary. Some people have remained mysteries, despite my trawling through censuses, marriage registers, birth certificates, and official records, but many more have come to life with such force it is as though they have been calling out for attention for years.

The Dictionary was a project that appealed to autodidacts and amateurs rather than professionals – and many of them were women, far more than we previously thought. It attracted people from all around the world as well as Britain: from Australia, Canada, South Africa, and New Zealand, to America, Europe, the Congo, and Japan. Remarkably, they were not generally the educated or upper classes that you might expect.

Over the years that I have been researching them, I have fallen in love with the Dictionary People. Most of them never met each other or the editors to whom they sent their contributions, and most were never paid for their work. But what united them was their startling enthusiasm for the emerging Dictionary, their ardent desire to document their language, and, especially for the hundreds of autodidacts, the chance to be associated with a prestigious project attached to a famous university which symbolized the world of learn- ing from which they were otherwise excluded. The Dictionary People could also be cranky, difficult, and eccentric – as James Murray often found out – but that, paradoxically, also makes them lovable, or at least fascinating.

Tracking the lives of these three thousand people has been a long task and, yes, a labour of love. I have wanted to tell the story of the OED from the ‘bottom up’ through the eyes of the volunteers rather than from the perspective of the editors or the scholars. Murray’s incredible record-keeping in his address books made much of this possible, though some of those three thousand were easier to track through the many archives I consulted than others: the biases within record-keeping meant that there were sometimes frustrating gaps in the evidence and a skew towards certain classes, genders, and ethnicities. And yet the stories of so many were findable – and I often found them on the margins. Even James Murray was unusual in not being part of the Oxford Establishment – he was Nonconformist and Scottish, and had left school at fourteen. He was an expert in the English language but he was also somewhat on the fringes. The OED was a project that attracted those on the edges of academia, those who aspired to be a part of an intellectual world from which they were excluded. While I always wanted to find out more about Miss Janet Coutts Pittrie of Chester who is marked in the address book as ‘Friend of Miss Jackson’; Mr John Donald Campbell, who was possibly a factory inspector in Glasgow; and Miss Mary A. Pearson, who was possibly a cook and servant in Eaton Square, London, the details of their lives eluded me. But there were so many more whose life stories popped out in technicolour as I was doing my research. I was thrilled to discover not one but three murderers, a pornography collector, Karl Marx’s daughter, a President of Yale, the inventor of the tennis-net adjuster, a pair of lesbian writers who wrote under a male pen name, and a cocaine addict found dead in a railway station lavatory. In the process of searching for these people, I have come across many hundreds of fascinating and often unexpected stories – dramatic and quotidian. I became obsessed with shining a light on these unsung heroes who helped compile one of the most extraordinary and uplifting examples of collaborative endeavour in literary history.

The time that the Dictionary was being written was an age of discoveries and science, an explosion of modern knowledge, and we see in so many of the rain collectors, explorers, inventors, and suffragists how much our current world was shaped by this relatively short period. There is a paradox about the very project of the Dictionary, the words collected for it and included in it. The Dictionary enterprise can easily be seen as a mastery of the world for the sake of the English language and the intellectual pas- sions of white people. Murray’s commitment to including all the words that had come into the English language may be seen as colonizing – or it may be seen as inclusive. Murray went out of his way to include all words, often being criticized for it by reviewers of the Dictionary and his su- periors at Oxford University Press. This means that the pages of the Dictionary incorporated words from the languages of Black and indigenous populations, and of people of colour. The Dictionary People who sent in those words were, for the most part, white, because of their privileged access to literacy in the period. The published sources of those words drew originally on the language of members of Black and indigenous communities whose names never made it into the pages of Murray’s address book, and it is important to acknowledge those often unseen and unrecorded interlocutors.

A myth of Murray has persisted as the Editor who devotedly and single-handedly created the world’s largest English dictionary with its half-million entries – only to die during the compiling of the letter T in 1915, not knowing whether his life’s work would ever be finished. While Murray was clearly a master-manager of the whole Dictionary project and had a small number of paid staff in the Scriptorium, this oft-told story ignores all the many people who corresponded with him and sent him words and quotations which made the Dictionary happen. The photograph in the Scriptorium might show only five men, but a careful observer will see the volunteer contributors clearly present, there in the thou- sands of word slips they sent, poking out of the pigeonholes. It is their lives that I unearthed and relate in this book.

The story here is one of amateurs collaborating alongside the academic elite during a period when scholarship was being increasingly professionalized; of women contributing to an intellectual enterprise at a time when they were denied access to universities; of hundreds of Americans contributing to a Dictionary that everyone thinks of as quintessentially ‘British’; of an above-average number of ‘lunatics’ contributing detailed and rigorous work from mental hospitals; and of families reading together by gaslight and sending in quotations. This extraordinary crowdsourced project was powered by faithful and loyal volunteers who took up the invitation to read their favourite books and describe their local words not just so that the bounds of the English language could be recorded for future generations but so they could be part of a project that was much bigger than them.

They are the Dictionary People, largely forgotten and unacknowledged—until now.

From THE DICTIONARY PEOPLE : The Unsung Heroes Who Created the Oxford English Dictionary by Sarah Ogilvie. Reprinted by permission of Alfred A. Knopf, an imprint of the Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. Copyright © 2023 by Sarah Ogilvie.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Definition of thesis noun in Oxford Advanced Learner's Dictionary. Meaning, pronunciation, picture, example sentences, grammar, usage notes, synonyms and more.

There are eight meanings listed in OED's entry for the noun thesis. See 'Meaning & use' for definitions, usage, and quotation evidence. thesis has developed meanings and uses in subjects including. prosody (Middle English) music (Middle English) rhetoric (late 1500s) logic (late 1500s) education (late 1700s) philosophy (1830s)

THESIS definition: 1. a long piece of writing on a particular subject, especially one that is done for a higher…. Learn more.

The thesis of a literary work is its abstract doctrinal content, that is, a proposition for which it argues. For 'thesis novel', see roman à thèse; for 'thesis play', see problem play. ... thesis in The Oxford Dictionary of Literary Terms (3) Length: 59 words Thesis and Antithesis in ...

The meaning of THESIS is a dissertation embodying results of original research and especially substantiating a specific view; especially : one written by a candidate for an academic degree. How to use thesis in a sentence.

THESIS meaning: 1. a long piece of writing on a particular subject, especially one that is done for a higher…. Learn more.

The largest and most trusted free online dictionary for learners of British and American English with definitions, pictures, example sentences, synonyms, antonyms, word origins, audio pronunciation, and more. Look up the meanings of words, abbreviations, phrases, and idioms in our free English Dictionary.

Definition of thesis in English:. cite. thesis

Course overview. This course is designed for students who are either writing, or preparing to write, a dissertation or thesis for their degree course at Oxford. Each lesson focuses on a different part of the thesis/dissertation/articles (Introductions, Literature Reviews, Discussions etc.), as well as the expected structure and linguistic ...

Thesis definition: a proposition stated or put forward for consideration, especially one to be discussed and proved or to be maintained against objections. See examples of THESIS used in a sentence.

thesis for the degrees of M.Litt. and D.Phil. under the aegis of the History Faculty. Candidates who ... (Oxford, 2005), New Oxford Dictionary for Writers and Editors. The Essential A-Z Guide to the Written Word (Oxford, 2005), and New Oxford Style Manual (2nd ed., Oxford, 2012). Together they form a mine of information on such matters as ...

Oxford English Dictionary. The historical English dictionary. An unsurpassed guide for researchers in any discipline to the meaning, history, and usage of over 500,000 words and phrases across the English-speaking world. ... Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence ...

Oxford theses. The Bodleian Libraries' thesis collection holds every DPhil thesis deposited at the University of Oxford since the degree began in its present form in 1917. Our oldest theses date from the early 1920s. We also have substantial holdings of MLitt theses, for which deposit became compulsory in 1953, and MPhil theses.

Oxford theses; UK theses; US theses; Legal deposit; Recommend a purchase; Theses and dissertations. Read our guidance for finding and accessing theses and dissertations held by the Bodleian Libraries and other institutions. Resources.

Thesis Oxford Dictionary - Free download as PDF File (.pdf), Text File (.txt) or read online for free. thesis oxford dictionary

The dictionary gives clear guidance on such matters as spellings (American English and British English), punctuation, abbreviations, prefixes and suffixes, units and quantities, and symbols.Revised and fully updated, this new edition of the Oxford Dictionary for Scientific Writers and Editors includes feature entries on key areas, substantially ...

Revised on January 17, 2024. To cite a dictionary definition in APA Style, start with the author of the dictionary (usually an organization), followed by the publication year, the word you're citing, the dictionary name, the publisher (if not already listed as author), and the URL. Our free APA Citation Generator can help you create accurate ...

Information about what plagiarism is, and how you can avoid it. The University defines plagiarism as follows: "Presenting work or ideas from another source as your own, with or without consent of the original author, by incorporating it into your work without full acknowledgement. All published and unpublished material, whether in manuscript ...

Instead, introduce the definition in your writing. One way to present this is as follows: According to the Oxford English Dictionary the definition of [XXXXX] is [XXXXXX] If however you have a particular need in your work to cite a language dictionary definition, for example, if comparing varying definitions from language dictionaries by ...

Known Author. Perhaps the easiest way to access the Oxford English Dictionary is through their various websites. If you know the author, here's how to cite it: Author's Last Name, First Name. "Title of Entry.". Title of Encyclopedia or Dictionary, Publication or Update Date, URL. Accessed Day Month Year site was visited.

Oxford English Dictionary

The Dictionary had started out with three men, Richard Chenevix Trench (1807-86), the Dean of Westminster Abbey, along with Herbert Coleridge (1830-61) and Frederick Fur- nivall (1825-1910 ...