An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Wiley - PMC COVID-19 Collection

Teaching participatory action research as engaged pedagogy in the time of pandemic

Jeane c. peracullo.

1 Department of Philosophy, De La Salle University, Manila Philippines

This article reflects on the process, challenges, and opportunities of conducting a graduate‐level class in environmental philosophy for Catholic priests who were seminary formators in the time of pandemic in the Philippines. The final output of the course is a participatory action research project. I developed an engaged pedagogical framework, which draws from the works of Jennifer Ayres that incorporated theological, philosophical, and ecological principles in teaching and facilitating students' research. The development of the tenets, the flourishing of all , right relations , and praxis began from a deep engagement with my students whose influence in the religious and cultural lives of the Filipinos could add to the flourishing of ecological consciousness of the Catholic community in the Philippines.

1. INTRODUCTION

What is it like to teach a course with participatory action research as the final output during a pandemic? In the first part of 2021, at the cusp of the second wave of the Covid‐19 pandemic in the Philippines, I handled a graduate course in environmental philosophy for a class of Ph.D. students composed of Catholic priests. The GRASEF (Graduate Program for Seminary Formators) is a platform designed for Catholic priests to obtain a Ph.D. in Philosophy to be a president of a seminary that can offer an undergraduate program in philosophy. The Ph.D. degree is a requirement of the Philippine Commission on Higher Education (CHED). A top Catholic university and the Catholic Bishops Conference of the Philippines (CBCP) collaborate for the GRASEF program. For the final output of the course, I decided that students adopt participatory action research instead of the standard philosophical research in other graduate courses. My main motivations were the following: The course in environmental philosophy aimed to familiarize the students with Philippine environmental movements, which can help them formulate contextual reflections informed by the Philippine situation; many environmental philosophers are activists whose ideas were profoundly influenced by their involvement in environmental issues and concerns; for students who are Catholic priests to rise to the challenge of Lynn White Jr's article, “The Historical Roots of the Ecologic Crisis,” ( 1967 ) where he claims that Christianity, as a religion, could be blamed for the environmental crisis; and for them to concretize the Catholic bishops' call to action concerning the environmental problems that beset the country. My students and I are formally trained in theological studies at the graduate level. In this connection, the opportunity to interweave philosophy and theology in the subject, environmental philosophy presented itself. The final research output's theme was “Participatory Action Research on the Catholic Engagement with the Environmental Crisis in the Philippines.”

Jennifer Ayres' reflections on our vulnerability during these precarious times of the pandemic and ecological crisis ( 2021 ) inform the paper's view of engaged pedagogy. She draws from Judith Butler's notion of vulnerability as a kind of bodily and emotional fragility that binds us together as human beings (Butler, 2014 ). Ayres extends the connection to include the more‐than‐human world ( 2021 , p. 328). Education, then, for Ayres, “should nurture in our resilience and open‐heartedness, capacities necessary to live honestly, compassionately, and courageously in a precarious and transient world” ( 2021 , p. 330). Ayres' newer work extends and particularizes the work she has been doing recently on environmental theology, significantly changing focus from being primarily anthropocentric to being more deeply ecocentric. Her article “Learning on the ground” ( 2014 ) shows how seminary education can be enriched by the bodily engagement that ranges from a “walk and talk” class activities to actualized commitment to “live life accordingly.” Such life is now awakened, engaged, and summoned ( 2014 , p. 213) by the embodied encounters with the other members of the planetary community. In this study, engaged pedagogy is an education that highlights the possibility of expanded ecological consciousness and nurtures the stakeholders' commitment to environmental justice and care.

The paper is divided into the following sections: the first part presents the framework of participatory action research or PAR. The second part discusses the process adopted in this project. The third part presents the challenges and opportunities that COVID‐19 brought to the participants, including the researchers and communities. The fourth part offers recommendations for doing PAR for theology and religion that draws from a multidisciplinary approach to address local and global environmental problems even in the time of a pandemic.

2. THE ENVIRONMENTAL ACTIVISM OF THE PHILIPPINE CATHOLIC CHURCH

The Catholic Church in the Philippines regards itself as a “Church of the Poor.” The mandate flows into the theological reflections of the faith community that had incorporated ecological concerns since the 80s. According to Paul‐Francoise Tremlett ( 2013 ), the decades‐long ecclesiastical resistance to mining activities in the Philippines has made the local Catholic Church be the only institution Filipinos can trust to speak out against environmental and other abuses (p. 122). Large‐scale mining in the Philippines has devastated entire forests, leveled off mountains, polluted rivers and lakes with their mine tailings and chemical wastes. Moreover, these activities were taking place in communities where indigenous peoples live. In 1988, twenty‐seven years before Laudato Si , the Filipino Catholic bishops released a pastoral letter on the environment. They narrated the environmental disasters happening in the country due to mining that destroyed the “beautiful land” and devastated the land‐centric culture of the Philippine indigenous peoples. Since 1988, the Catholic bishops have released ten more pastoral letters on the environment. The publication of Laudato Si in 2015 influenced the Filipino bishops to be more vocal about the destructive effects of climate change. In January 2022, the Catholic Bishops Conference of the Philippines (CBCP) announced that the Catholic Church will divest from local banks that continue to support fossil fuels in 2025 and will actively promote the use of renewable energy in its parishes and schools (CBCP, 2022 ).

The Philippine Catholic Church has leveraged its massive influence on the cultural lives of the people to be able to conduct an effective ecclesiastical praxis on environmental issues and concerns, especially mining. Some of my students who had their formation studies in seminaries where extensive mining occurred shared that several academic modules would allude to the interlocking issues of mining, loss of biodiversity, and destruction of the indigenous peoples' homes and cultures. Nonetheless, the colonial past of Christianity in the Philippines is a contentious point. Gaston Kibiten interrogates the Catholic Church's complicity in undermining the cultures of indigenous peoples in the Philippines ( 2018 ). He claims that this examination is necessary despite the history of the Catholic bishops' public statements on respecting and protecting ancestral or indigenous lands, and even after Pope Francis' call for a dialogue with the indigenous peoples in Laudato Si . The Philippine Catholic Church has tried to address this problem. Karl Gaspar cites the 2010 Episcopal Commission on Indigenous Peoples' statement that essentially asks for forgiveness from indigenous peoples for the “historical wounds” which were inflicted for the time when “[the Church] entered indigenous communities from a position of power, indifferent to their struggles and pains. We ask forgiveness for moments when we taught Christianity as a religion robed with colonial cultural superiority, instead of sharing it as a religion that calls for a relationship with God and a way of life” (Gaspar, 2010 ).

The above discussion points to the reality that there is still more work to be done by the Catholic clergy to deepen its ecological commitment through sustained actions. In his study on the impact of the 2nd Plenary Council of the Philippines (PCP II) on the Basic Ecclesiastical Communities (BECs), Ferdinand Dagmang ( 2015 ) notes that the successful implementation of the program could be attributed to the laity's committed participation and did not just depend on the initiatives of ecclesiastical leaders. A student shared the same conclusion, observing that “the goal of leading people to the mission of ecological ethics is enormous for a single individual, but with the contributive effort from the community, the goal becomes reachable.”

3. THE PARTICIPATORY ACTION RESEARCH

What is participatory action research (PAR)? For Chevalier and Buckles ( 2013 ), it entails participation by stakeholders in a systematic research process aimed at advancing knowledge that results in action for social change on the part of the stakeholders. In the academic‐community collaboration, the stakeholders include the faculty, staff, and students of a learning institution and the members or organizations outside the academe. As a general philosophy or framework for research, PAR emphasizes the connection of research with action in a real‐world setting that advances knowledge beneficial to the researchers and participants (Fletcher et al., 2015 , p. 1).

A PAR framework typically has four components: participatory, action, research, and social transformation. Participatory refers to the scope of the collaboration between individuals and communities or organizations. The extent of the partnership must begin with the community's involvement in the research design of the proposed project, from conceptualization to the final output, which is often in the form of advocacy or capacity‐building. There is a mutual understanding between the community and the academic institution from the onset. Each understands that everyone is a stakeholder for social change. The participation component includes ethical considerations of ensuring voluntary participation and withdrawal, informed consent, and the health and safety of the stakeholders.

The action component refers to the researchers' task to build the community partners' capacity to analyze issues and concerns in their community, reflect on their possible causes and effects, and act towards change. Reflecting on their long‐term project using PAR, Constantinou and Ainscow ( 2020 ) posit that the active component of the research has led to “the development of a form of collaborative inquiry in which participants were enabled to move from being data‐respondents to becoming co‐researchers and data‐inquirers, to become aware of and, if possible, improve their situations” (p. 9). The key is the meaningful engagement of stakeholders, especially young people whose unique needs, experiences, and insights can provide policymakers with tools to respond to their concerns (Liebenberg et al., 2017 ).

The research component of PAR indicates that the research's goal is social transformation. The researchers ensure that the stakeholders are informed and consulted at every step of the research design, from conceptualization of the project, appropriate methodologies for data collection, and the final output or result. Sharing the research in a way that is useful for the community is part of the research component of PAR. Liebenberg et al. note that the platform to initiate change would not be established without sharing the findings in meaningful and impactful ways ( 2017 , p. 7). The researchers may need to revisit the research design and ensure that the research problems are well‐laid out, objectives are clearly articulated, and the research output is doable and realistic.

The social transformation component may be built from theoretical frameworks to achieve social change. Paulo Freire's critical pedagogy to raise consciousness is one such framework (Freire, 1970 ). It can be inspired by a feminist perspective where women are not regarded as subordinates but active participants of their own lives and self‐determination (Adriany et al., 2021 ). It can be from a liberative theological paradigm wherein the see‐judge‐act mode of analysis enables us to adapt newer theological insights and pastoral actions towards social change (Gutiérrez, 1973 ). Sallie McFague claims that Christianity has preached the Good News for so long that it has forgotten that the Redeemer of human beings is also the Redeemer of everything that is (McFague, 1997 ). It is an “oversight” on the part of Christianity when it fails to include nature as one of the recipients of the “Christian praxis” that opts for the poor, oppressed, and the needy, or when it fails to develop a subject‐subjects model for nature as part of its expression of faith. The natural world is vulnerable, sick, disadvantaged, and deteriorating; thus, Christian nature spirituality means caring for nature as Christian practice concerning the natural world. This “praxis” is an affirmation that the Redeemer God is also the Creator God, that God loves all creation, especially those who are vulnerable, sick, and needy. God's love is inclusive, and therefore, it does not stop with the human species. The word “oppressed” changes over time; nature should be included inside the circle of divine concern, not outside it.

It might be inspired by a deep, ecological paradigm that rejects anthropocentrism, adopts biocentrism, upholds environmental kinship, and fosters respect and care for nature (Naess, 2005 ). According to Thomas Berry ( 1988 ), anthropocentrism has blinded humanity to the position that the human species is a product of the natural evolutionary processes of the universe. It has wound its way in human affairs, especially in Western civilization that emphasizes dualities of mind and body, spirit, and matter, as well as the eternal and the temporal. In the phenomenal order, Berry argues that the universe is the only being in “self‐referent” mode, and all beings within it are “universe‐referent.” All beings constitute a unity of existence coherently and intelligibly, as demonstrated by scientists studying the universe over a long time. The universe is a communion of subjects rather than a collection of objects. Berry ( 1988 ) argues that the traditional biblical creation story has become outmoded. He seeks to replace it with a new story that traces the evolutionary development of life from the first formation of particles in space to the creation of conscious human beings. The task for people is not to choose a better story but to find avenues for the creation stories to enrich one another.

4. TEACHING PARTICIPATORY ACTION RESEARCH

This section presents students' steps to create a good research design following the PAR framework. The preparation for the research started at the beginning of the course. A course typically runs for 14 weeks or 1 Term. To make the workload manageable, a compassionate teacher must distribute the tasks evenly throughout the term.

4.1. The focus of the research

What is the most pressing environmental issue that your parish or community faces? What is the history of the problem? Is the situation better or worse than before? I framed these questions to elicit from students an awareness of environmental issues in the community that they might not have recognized as an issue, a problem, or a concern. Although they were Catholic priests, they were also doing administrative tasks for the diocese or parish and might not be too aware of environmental issues in their communities.

4.2. Stakeholders and actors

In the second week of the term, the students would identify the stakeholders and actors. The guide questions for this part are as follows: Who is working on the ground to address the issue? Who is the most affected by the problem or crisis? Additionally, the students need to identify a community partner, local government unit, non‐governmental organization, a private organization in their parish/community to assist the research. They must find out those who are severely affected by the environmental crisis. Those affected might include nonhuman beings, bodies of water, ecosystems, biodiversity, and others.

I scheduled an individual Zoom meeting for one hour to address my students' concerns regarding this part of the research design. During the personal consultation, we defined the concept of community in the light of restricted mobility due to lockdowns and travel restrictions. All students, except one, opted to work and partner with their seminaries and parishes to minimize the need to travel to a remote community.

4.3. Research objectives

In the third week, the students were ready to write their research objectives. The guide question for this part was simple: What does the research aim to achieve?

4.4. Research methods

In the fourth week, the students identified the research method that would work best for them. Before the pandemic, research methods were classified as qualitative, an analysis of literature that includes personal narratives of stakeholders and actors. They can be quantitative, an analysis using objective measurements and the statistical, mathematical, or numerical analysis of data collected through polls, questionnaires, and surveys. The pandemic upended traditional face‐to‐face research methods. Traditional methodologies that rely on fieldwork, face‐to‐face interviews, surveys, and data‐gathering posed significant risks to researchers and participants. On the second individual consultation with my students, we talked about some creative methods that they could use for data collection that would not put them and their community partners at risk. Some students used photo‐elicitation, online surveys, interviews, and focus group discussions to ensure safe social distancing with a limited number of participants.

4.5. The participatory action research proposal

In the fifth week, the students were ready to submit their research proposals. The proposal is an abstract or overview of the entire action research. It should contain the research question, theoretical framework, method, tentative conclusion, and research outcome. The research outcome was a project that is actionable, realistic, and adaptable by the community, either as a community project or towards a grant proposal to fund a project.

4.6. Progress report

In the eighth week, the students presented their progress reports. This part of the process or steps allowed the students to describe in class some challenges they encountered, if any, and whether they made some changes to their original research proposal. To facilitate the discussions, I prepared guide questions such as:

- Were there changes you made to your research after collecting data?

- Did you make some changes to your research objectives or goals?

- What problems have you encountered so far at this point of your research?

- What research method do you think is applicable right now?

The progress reports were significant because the students could express the difficulties in carrying out participatory action research in the pandemic. At the same time, though, they could draw strength from one another and offer support.

4.7. The final paper

In the fourteenth week, the students submit their final paper. The titles of the projects in Table 1 manifest the place‐based dimension of the research. The students identified the community by name and included their seminary or diocese in the title. Similarly, a student identified Taal Lake as the locale of the research. According to Estey ( 2014 ), place‐based educational methods decenter the traditional classroom as the sole locus of learning, thus focusing on the non‐traditional environment, including the natural environment that might have been overlooked as a possible locale for education (p. 125).

Titles of the participatory action research project

5. CHALLENGES AND OPPORTUNITIES

The Covid‐19 pandemic presented several challenges and opportunities for conducting participatory action research. According to my students, mobility restrictions hampered their visit to more ecologically distressed communities, often in rural areas. In the Philippines, seminaries are found in highly urbanized city centers. As a response to this difficulty, most of the students identified their seminary or diocese, where they were residing, as the community partner. However, one student opted for a more remote community, away from the seminary and the diocese grounds.

Localizing the meaning of community within the confines of their seminaries and dioceses enabled the students to be aware of overlooked environmental issues occurring within their jurisdiction. A student decided to work on water pollution to address a baffling problem that had hounded the seminary for years. A decade ago, the seminary cultivated a lush, vibrant orchid flower farm that was economically viable. Over the years, the orchid plants started dying in droves until the farm became unsuitable for orchid cultivation. The student, through the research, suspected that prolonged and sustained use of chemical fertilizers poisoned the farm, and worse, the toxins might have contaminated the seminary's potable water supply. Some students identified the lack of a waste management system in their seminaries. A couple of students noted the lack of environmental studies in the seminary formation despite Laudato Si and the local Catholic Church's efforts to address environmental issues in the country. The lack of group recreational activities due to the pandemic provided an opportunity for the student who decided to engage a local community. It was during this time that the student took to cycling. Together with his group of recreational cyclists, they usually took the route going to the towns around Taal lake in the southern part of Manila. Immersing into the communities and observing the lake's condition, the student, with the help of the cycling community, decided to raise awareness for the preservation of the lake.

In the individual consultations, the students initially struggled with identifying the stakeholders and actors in their communities. The intervention I used for this problem was to forward a tree model to identify stakeholders. The tree model captured our discussions on identifying those greatly affected by the issue and benefit significantly from the solution.

The tree's roots refer to the stakeholders and actors affected severely but will benefit significantly from solutions offered and adopted. As we move higher to other parts of the tree, the “trunk” refers to those who are less severely affected; the “leaves” pertain to those who are “moderately affected; and the “leaves“ refer to the stakeholders who are less affected. For the seminary communities, the students identified the seminarians as the “roots,“ the staff and non‐clergy faculty as the “trunk,“ the formators and clergy faculty as the “branches,“ and the diocese that runs the seminary as “leaves.” The visual representation was helpful because the students could identify the affected actors who could become active participants in addressing the environmental issues that affect the community. Some students extended the Tree Model by adding more roots and leaves to refer to the broader community outside the seminary or diocese.

The choice of appropriate research methods and data collection proved to be some of the biggest challenges that the students faced. The pandemic hastened the Filipinos' adoption of online platforms for classes, work, and even worship services. The Filipinos are one of the world's most engaged people on social media; however, the Internet also highlights the digital divide in the country (Juya, 2020 ). Many Filipinos cannot access the Internet fully because of poverty and poor infrastructure, especially in rural areas. The students in environmental philosophy would have to use creative research methods to obtain data.

For research involving interviews of key informants, the students used Facebook, Messenger, Zoom, and Google Meet. The social media platforms are accessible, and telecommunication companies bundle the apps freely into the subscription. In research involving many participants like the Ministry of Family Life Apostolate members, the student conducted virtual focus group discussions where he presented his research proposal, gathered the members' feedback and questions, and offered the research results were integrated into the existing programs of the ministry. In the pre‐Cana seminar, “Economic Aspect of Family Life,” the idea of ecological stewardship would be introduced to couples before they start their families.

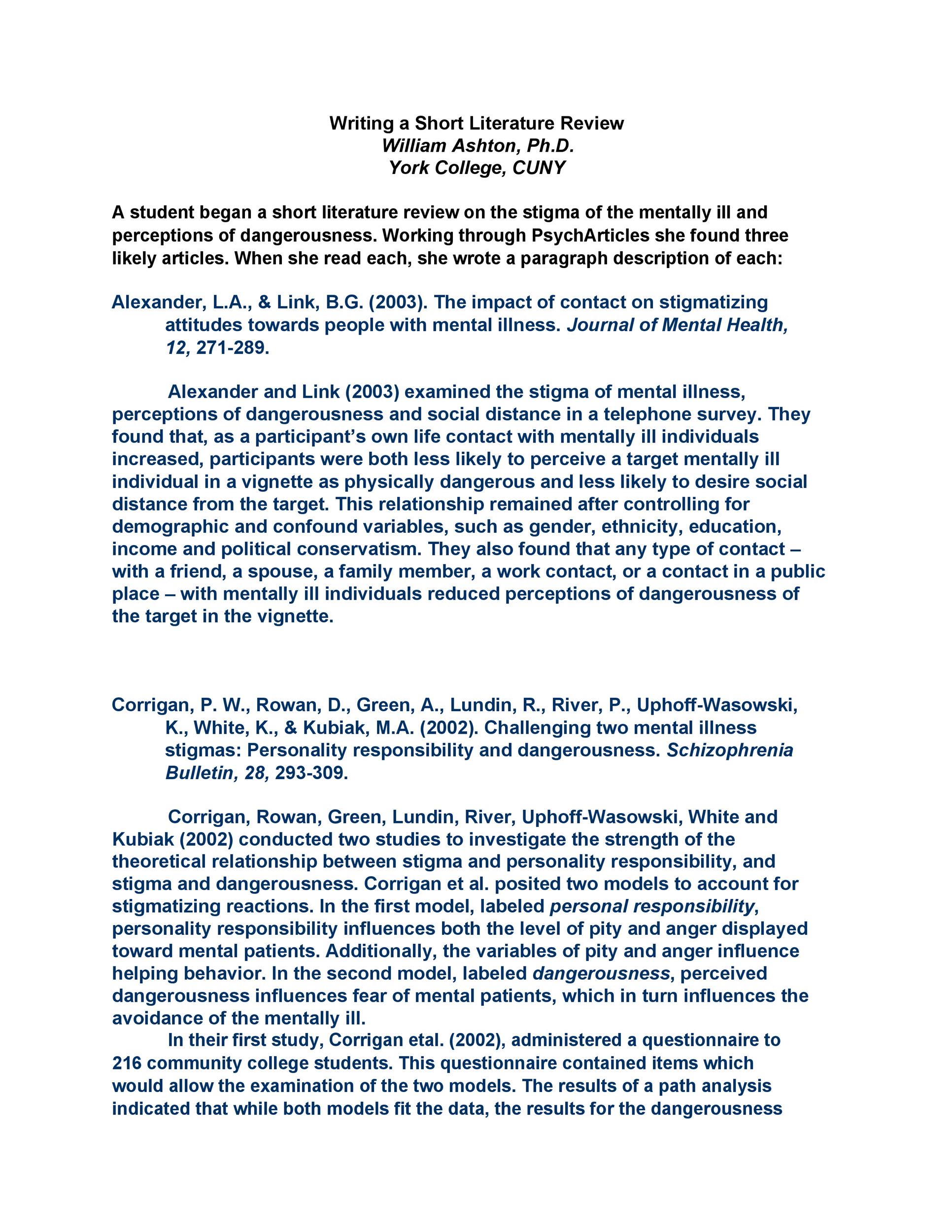

Another creative method that a student used is photo‐elicitation through the participants' photographs. Participant‐generated photo‐elicitation usually involves inviting participants to take pictures, then discuss them during a subsequent interview or in a focus group. This approach can provide participants with the opportunity to bring their content and interests into research (Dunlop & Ward, 2012 ; Gou & Shibata, 2017 ). The student requested the members of his parish in a rural community to gather evidence that the community practiced a sound waste management system. Figure 1 is a participant‐generated photograph of a clean road and neatly organized plastic bags containing waste. The method allowed the student‐researcher to follow the recommended health protocols while remaining engaged with his parishioners.

Parish waste management system. Photograph by a research participant [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com ]

The unique position that my students occupy in the Roman Catholic Church as clergy provided them with the opportunity to implement their projects. As seminary formators, the students whose research projects involved the seminary community found little resistance against their projects, from conceptualization to implementation. Their judgment as priests, educators, and scholars carried weight and gravitas . In two of the research projects, one helped design a sound water management system to address water pollution, and the other created a viable vegetable garden design for every parishioner to adopt and use. Likewise, in research involving members of a Diocesan ministry and parishioners, the faithful would seem to consent to the priests' requests to participate in the study and to agree with their recommendations. However, in research involving a remote community, the student‐researcher found it challenging to engage the people in the community and to find like‐minded cycling enthusiasts who would support his research. Even pre‐pandemic, the opportunity and challenges described above are present.

Nevertheless, in narrating the research process in their final paper, the student‐researchers ensured that participants of their study volunteered willingly, and they took note of the participants' inputs and insights. To do the research ethically, the students gathered the participants' consent through a series of preliminary online meetings where they presented their project proposals. The participants' willingness to join the research projects of their pastors manifested their trust in the latter. Building trust is an essential part of doing participatory action research. Trust does not happen in an instant. Both researchers and participants cultivate it over time. In the Philippines, with a large Catholic population, priests are among the most trusted by Filipinos.

6. ENGAGED PEDAGOGY IN THE TIME OF PANDEMIC

The PAR Framework is a tool in engaged pedagogy. Engaged pedagogy involving environmental philosophy and ecological theology requires that learning institutions undertake collaborative partnerships with communities outside academia. In the pre‐pandemic period, partnerships with marginalized communities could be made. However, the pandemic posed challenges to the conduct of collaborative partnerships. One of my students initially thought of working with the badjao , an impoverished indigenous linguistic group living in Mindanao. Due to the health risks posed by the Covid‐19 virus, he decided to choose a community within the diocese where he lived and worked. Selecting a community where one lives is inspired by an ecological principle, “niche.” “Niche” pertains to the species' ability, determined by the traits, to gather resources, evade enemies, and any other factor that influences its relative birth and death rates (Chase & Myers, 2011 ; Polechová & Storch, 2019 ).

While teaching environmental philosophy to graduate students who were Catholic seminary formators, I developed an engaged pedagogy framework that considered theological, philosophical, and ecological principles.

The first principle, the flourishing of all , refers to the end or purpose of why we use engaged pedagogy in teaching and research. The notion of flourishing is based on Jesus' words in John 10:10: “I came that they may have life and may [a]have it abundantly.” The superabundance of life does not have to be confined to human life. Following McFague ( 1997 ), Jesus is the redeemer of all. The “all” refers to humans and nonhumans alike. To work for human flourishing is not enough; we must contribute to addressing environmental destruction that results in unimaginable loss of life and biodiversity. Leopold ( 1949 ) underscores the importance of knowing and understanding flourishing as members of the biotic community that live and thrive within it. In the context of learning, the ecosystem includes the members of the academic community.

The Covid‐19 pandemic, on the one hand, manifests the interconnectedness of lives worldwide by connecting us through collective suffering and despair. The pandemic highlights that in moments of “illness,” shock waves of pain reverberate worldwide. It reveals the extent of the effects of systemic social inequalities that result in acts of injustice towards groups we render as “Others.” The pandemic brings to our attention the imbalance such as lack of access to quality healthcare and discrimination of racial/ethnic minorities for generations (Ahlers et al., 2020 , p. 25; Ayres, 2021 ).

On the other hand, reflecting on the pandemic offers opportunities to attend to the illness collectively. It reminds us that there are connections between human activities, environmental destruction, and the ill effects of the pandemic. In the context of religious and theological studies, teaching and research can address questions such as: How did spiritual and religious narratives help or assist believers/devotees/adherents in coping with traumas associated with COVID‐19? What lessons can be learned from their experiences that will enrich the use of spirituality and religion in healing therapies in the post‐pandemic future?

Earlier, I mentioned the community's enthusiastic response towards some of my students' project proposals. In projects that required the participation of communities outside the seminary, the students acknowledged the inputs of the laity by listening to their stories during focus group discussions either online or in‐person. A student who was recently appointed chaplain of a new parish in the city's outskirts was pleasantly surprised to learn that the community had high regard and concern for the environment, especially when it came to proper waste segregation and management even before the parish was established. Another student reflected that the vulnerable Taal Lake and its human communities changed his perspective from a distant and disconnected relationship to one that is close and intimate. At the same time, the Catholic priests enjoy power and influence as ministers when it comes to much more to the community through their actions. This observation regarding environmental care is consistent with Dagmang's assessment of the impact of the Second Plenary Council of the Philippines in the life of the Catholic Church. The Basic Ecclesial Communities (BECs) in the rural areas of the country have been instrumental in translating the ideas of being the “Church of the Poor” into concrete actions (Dagmang, 2015 ).

The second principle, right relations , refers to the values that will result in the flourishing of all. In determining the level of institutional engagement with communities or organizations, researchers must constantly observe ethical conduct. This means respecting the existing cultures and traditions of partner communities or organizations. We must also demonstrate empathy and compassion towards our partners, students, and fellow researchers. In the greater community, right relations in the pandemic necessitates that we observe health protocols such as wearing masks, maintaining appropriate social distancing, minimizing social gatherings, and ensuring data privacy at every stage of the research process.

The third principle, praxis , refers to the actions that manifest both tenets of the flourishing of all and right relations by demonstrating our skills and competence as teachers and researchers. Freire ( 1970 ) uses praxis to offer a pedagogy based on reflection and action about the world to transform it for the better. To be skillful, we must be able to communicate the vision of engaged pedagogy to our students so that they, in turn, would manifest the skills to engage the community for the better. Cipollone and Zygmunt ( 2018 ) describe a culturally sensitive teacher whose praxis includes careful preparation of materials during pre‐teaching, a respectful attitude towards the members of the community whose insights into the community are valuable, a competent mentoring of students' research from beginning to end, and the capacity to empower students to communicate the research results to the community for feedback, validation, and adoption.

The pandemic still rages worldwide, making lives difficult for the millions severely affected by the economic and social loss. It also opens chances to work together to address social and environmental problems by working with and through communities. In the feedback session, after the student‐researcher has presented his plan to integrate environmental studies into the seminary formation, he shared that the seminarians appreciated the project for “intellectual formation develops ecological awareness by integrating ecology as part of theology. Biblical studies, particularly in the Pentateuch, develops ecological awareness. Christian anthropology elaborates the role and place of human beings in the complex web of creation. Pastoral formation cultivates ecological awareness through the preferential option for the poor. Our apostolate to the poor is not limited only to the poor but to the Earth. For the Earth is poor. We take so much from the Earth, but we have not given her enough compensation.”

A student who worked on the legacy of Bishop Jose Manguiran, a passionate environmentalist who has campaigned hard against mining in his diocese and has supported the indigenous peoples' right to their ancestral domain, reflected that it would not be difficult for Filipino Catholics to reject anthropocentrism and embrace ecocentrism. He then cited the following passage in Job 12: 7: “Ask the beasts, and they will teach you; the birds of the heavens, and they will tell you, or the bushes of the earth, and they will teach you.”

7. CONCLUSION

What is it like to teach a course in environmental philosophy for Catholic priests and seminary formators? The whole experience was rewarding. I realized early on that there could be a promise and a potential in the opportunity to craft participatory action research for this group of students. As priests, educators, and scholars, they can harness their influence in the religious and cultural lives of the Filipino people towards community‐building, including restoring the biotic communities in their seminary, or diocese, or beyond it. The act of restoring must arise first from the recognition of our shared “woundedness” and “frailty” (Ayres, 2021 , p. 335), living as we do in a world equally wounded by the ecological crisis.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The author declares no conflict of interest.

ETHICS STATEMENT

Written informed consent has been obtained from all subjects involved in this study.

Peracullo, J. C. (2022). Teaching participatory action research as engaged pedagogy in the time of pandemic . Teaching Theology & Religion , 25 ( 1 ), 3–13. 10.1111/teth.12604 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Adriany, V. , Yulindrasari, H. , & Safrina, R. (2021). Doing feminist participatory action research for disrupting traditional gender discourses with Indonesian Muslim kindergarten teachers . Action Research , 1 ( 2 ), 1–17. 10.1177/14767503211044007 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ahlers, K. P. , Ayers, K. B. , Iadarola, S. , Hughes, R. B. , Lee, H. S. , & Williamson, H. J. (2020). Adapting participatory action research to include individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities during the COVID‐19 global pandemic . Developmental Disabilities Network Journal , 1 ( 2 ), art.5. 10.26077/ec55-409c [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ayres, J. (2014). Learning on the ground: Ecology, engagement, and embodiment . Teaching Theology & Religion , 17 ( 3 ), 203–216. https://doi-org.easyaccess1.lib.cuhk.edu.hk/10.1111/teth.12202 [ Google Scholar ]

- Ayres, J. (2021). A pedagogy for precarious times: Religious education and vulnerability . Religious Education , 116 ( 4 ), 327–340. 10.1080/00344087.2021.1933345 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Berry, T. (1988). The dream of the Earth . Sierra Club. [ Google Scholar ]

- Butler, J. (2014). Bodily vulnerability, coalitions, and street politics . Critical Studies , 37 , 99–119. [ Google Scholar ]

- Catholic Bishops Conference of the Philippines (CBCP) . (2022, January 28). A call for unity and action amid a climate emergency and planetary crisis . https://cbcpnews.net/cbcpnews/a-call-for-unity-and-action-amid-a-climate-emergency-and-planetary-crisis/

- Chase, J. M. , & Myers, J. A. (2011). Disentangling the importance of ecological niches from stochastic processes across scales . Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B , 366 , 2351–2363. 10.1098/rstb.2011.0063 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Chevalier, J. , & Buckles, D. (2013). Participatory action research: Theory and methods for engaged inquiry . Routledge. [ Google Scholar ]

- Cipollone, K. , & Zygmunt, E. (2018). A pedagogy of promise: Critical service‐learning as praxis in community‐engaged, culturally responsive teacher preparation. In Handbook of research on service‐learning initiatives in teacher education programs (pp. 333–354). IGI Global. 10.4018/978-1-5225-4041-0.ch018 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Constantinou, E. , & Ainscow, M. (2020). Using collaborative action research to achieve school‐led change within a centralized education system: Perspectives from the inside . Educational Action Research , 28 ( 1 ), 4–21. 10.1080/09650792.2018.1564686 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Dagmang, F. (2015). From Vatican II to PCP II to BEC too: Progressive localization of a new state of mind to the new state of affairs. In Kochuthara S. G. (Ed.), Revisiting 50 years of renewal volume II: Selected papers of the DVK International Conference on Vatican II (pp. 308–326). Dharmaram. [ Google Scholar ]

- Dunlop, S. , & Ward, P. (2012). From obligation to consumption in two‐and‐a‐half hours: A visual exploration of the sacred with young Polish migrants . Journal of Contemporary Religion , 27 ( 3 ), 433–451. 10.1080/13537903.2012.722037 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Estey, K. (2014). Place‐based pedagogy . Teaching Theology & Religion , 17 , 122–137. https://doi-org.easyaccess2.lib.cuhk.edu.hk/10.1111/teth.12180 [ Google Scholar ]

- Fletcher, A. J. , MacPhee, M. , & Dickson, G. (2015). Doing participatory action research in a multicase study: A methodological example . International Journal of Qualitative Methods. , 14 ( 5 ), 1–9. 10.1177/1609406915621405 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Freire, P. (1970). Pedagogy of the oppressed . Herder and Herder. [ Google Scholar ]

- Gaspar, K (2010). The story behind the indigenous peoples' Sunday. https://www.mindanews.com/around-mindanao/2010/10/the-story-behind-the-indigenous-peoples-sunday/

- Gou, S. , & Shibata, S. (2017). Using visitor‐employed photography to study the visitor experience on a pilgrimage route—A case study of the Nakahechi route on the Kumano Kodo pilgrimage network in Japan . Journal of Outdoor Recreation and Tourism , 18 , 22–33. 10.1016/j.jort.2017.01.006 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Gutiérrez, G. (1973). A theology of liberation: History, politics, and salvation . Orbis Books. [ Google Scholar ]

- Juya, G. (2020, July 22). Less likely to return to schools post lockdown, the pandemic has hit girls the hardest . Youth Ki Awaaz . https://www.youthkiawaaz.com/2020/07/less-likely-to-return-to-schools-post-lockdown-the-pandemic-has-hit-girls-the-hardest/

- Kibiten, G. (2018). Laudato Si's call for dialogue with indigenous peoples: A cultural insider's response from the Christianized indigenous communities of the Philippines . Solidarity: The Journal of Catholic Social Thought and Secular Ethics , 8 ( 1 ), 4. [ Google Scholar ]

- Leopold, A. (1949). A sand country almanac: And sketches here and there . Oxford University Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- Liebenberg, L. , Sylliboy, A. , Davis‐Ward, D. , & Vincent, A. (2017). Meaningful engagement of indigenous youth in par: The role of community partnerships . International Journal of Qualitative Methods , 16 ( 1 ), 1–11. 10.1177/1609406917704095 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- McFague, S. (1997). Super, natural Christians: How should we love nature . Fortress Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- Naess, A. (2005). The shallow and the deep, long‐range ecology movement: A summary. In Drengson A. & Glasser H. (Eds.), The selected works of Arne Naess volumes 1–10 (pp. 1–6). Springer. https://link-springer-com.easyaccess1.lib.cuhk.edu.hk/book/10.1007%2F978-1-4020-4519-6 [ Google Scholar ]

- Polechová, J. , & Storch, D. (2019). Ecological niche. In Encyclopedia of ecology (2nd ed.) (pp. 72–80). Elsevier BV. 10.1016/B978-0-12-409548-9.11113-3 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Tremlett, P. F. (2013). The ancestral sensorium and the city: Reflections on religion, environmentalism, and citizenship in the Philippines. In Harvey G. (Ed.), Handbook of contemporary animism (pp. 113–123). AcumUK. [ Google Scholar ]

- White, L. T. (1967). The historical roots of our ecologic crisis . Science , 155 , 1203–1207. 10.1126/science.155.3767.1203 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

Action Research Design

- First Online: 04 January 2024

Cite this chapter

- Stefan Hunziker 3 &

- Michael Blankenagel 3

392 Accesses

This chapter addresses action research design’s peculiarities, characteristics, and significant fallacies. This research design is a change-oriented approach. Its central assumption is that complex social processes can best be studied by introducing change into these processes and observing their effects. The fundamental basis for action research is addressing organizational problems and their associated unsatisfactory conditions. Also, researchers find relevant information on how to write an action research paper and learn about typical methodologies used for this research design. The chapter closes by referring to overlapping and adjacent research designs.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Altrichter, H., Kemmis, S., McTaggart, R., & Zuber-Skerritt, O. (2002). The concept of action research. The Learning Organization, 9 (3), 125–131.

Article Google Scholar

Bamberger, G. G. (2015). Lösungsorientierte Beratung. 5. Aufl. Beltz.

Google Scholar

Baskerville, R. (1999). Investigating Information Systems with Action Research. Communications of AIS, Volume 2, Article 19. https://wise.vub.ac.be/sites/default/files/thesis_info/action_research.pdf .

Baskerville, R. (2001). Conducting action research: High risk and high reward in theory and practice. In E. M. Trauth (Ed.), Qualitative research in is: issues and trends (pp. 192–217). IGI Publishing.

Baskerville, R. & Lee. A. (1999). Distinctions among different types of generalizing in information systems research. In O. Ngwenyama et al., (Ed.), New IT technologies in organizational processes: Field studies and theoretical reflections on the future of work. Kluwer.

Baskerville, R., & Wood-Harper, A. T. (1998). Diversity in information systems action research methods. European Journal of Information Systems, 7 (2), 90–107.

Blichfeldt, B. S., & Andersen, J. R. (2006). Creating a wider audience for action research: Learning from case-study research. Journal of Research Practice, 2 (1), Article D2. http://jrp.icaap.org/index.php/jrp/article/view/23/69 . (Accessed 10 May 2021).

Borrego, M., Douglas, E. P., & Amelink, C. T. (2009). Quantitative, qualitative, and mixed research methods in engineering education. Journal of Engineering Education, 98 (1), 53–66.

Bunning, C. (1995). Placing action learning and action research in context. International Management Centre.

Cauchick, M. (2011). Metodologia de Pesquisa em Engenharia ee Produção e Gestão de Operações. (2nd ed.). Elsevier.

Coghlan, D., & Shani, A. B. (2005). Roles, politics and ethics in action research design. Systemic Practice and Action Research, 18 (6), 533–546.

Cole, R., Purao, S., Rossi, M., & Sein, M. K. (2005). Being proactive: Where action research meets design research. ICIS.

Collatto, D. C., Dresch, A., Lacerda, D. P., & Bentz, I. G. (2018). Is action design research indeed necessary? Analysis and synergies between action research and design science research. Systemic Practice and Action Research, 31 (3), 239–267.

Coughlan, P., & Coghlan, D. (2002). Action research for operations management. International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 22 (2), 220–240.

Cunningham, J. B. (1993). Action research and organizational development. Praeger Publishers.

Davison, R. M., & Martinsons, M. G. (2007). Action research and consulting. In Ned Kock (Ed.), Information systems action research. An applied view of emerging concepts and methods (vol. 13, pp. 377–394). Springer (Integrated Series in Information Systems).

Davison, R., Martinsons, M. G., & Kock, N. (2004). Principles of canonical action research. Information Systems Journal, 14 (1), 65–86.

Dick, B. (2003). Rehabilitating action research: Response to Davydd Greenwood’s and Björn Gustavsen’s papers on action research perspectives. Concepts and Transformation, 7 (2), 2002 and 8 (1), 2003. Concepts and Transformation, 8 (3), 255–263.

Dickens, L., & Watkins, K. (1999). Action Research: Rethinking Lewin. Management Learning, 30 (2), 127–140.

Eden, C., & Huxham, C. (1996). Action research for management research. British Journal of Management, 7 (1), 75–86.

Foster, M. (1972). An introduction to the theory and practice of action research in work organizations. Human Relations, 25 (6), 529–556.

Grønhaug, K., & Olsson, O. (1999). Action research and knowledge creation: Merits and challenges. Qualitative Market Research, 2 (1), 6–14.

Heller, F. (1993). Another look at action research. Human Relations, 46 (10), 1235–1242.

Holmström, J., Ketokivi, M., & Hameri, A-P. (2009). Bridging Practice and Theory: A Design Science Approach. Decision Sciences 40 (1), 65–87.

Hult, M., & Lennung, S. -Å. (1980). Towards a definition of action research: A note and bibliography. Journal of Management Studies, 17 (2), 241–250.

Hüner, K. M., Ofner, M., & Otto, B. (2009). Towards a maturity model for corporate data quality management. 24th Annual ACM Symposium on Applied Computing (ACM SAC 2009).

Järvinen, P. (2007). Action research is similar to design science. Quality & Quantity, 41 (1), 37–54.

Lau, F. (1997). A review on the use of action research in information systems studies. In A.S. Lee, J. Liebenau, & J. I. DeGross (eds.), Information systems and qualitative research. IFIP—the international federation for information processing. Springer.

Loebbecke, C., & Powell, P. (2009). Furthering distributed participative design. Scandinavian Journal of Information Systems, 21, 77–106.

Iivari, J., & Venable, J. (2009). Action research and design science research—Seemingly similar but decisively dissimilar. In 17th European Conference in Information Systems. ECIS, Verona, pp. 1–13.

March, S.T., & Smith, G. F. (1995). Design and natural science research on information technology. Decision Support Systems, 15 (4), 251–266.

McKay, J., & Marshall, P. (2001). The dual imperatives of action research. Information Technology & People, 14 (1), 46–59.

Mohrman, S. A., & Lawler, E. E. (2011). Useful research: Advancing theory and practice. Berrett-Koehler.

Pries-Heje, J., & Baskerville, R. 2008. The Design Theory Nexus. MIS Quarterly, 32 (4), 731–755.

Ractham, P., Kaewkitipong, L., & Firpo, D. (2012). The use of facebook in an introductory MIS course: Social constructivist learning environment. Decision Sciences Journal of Innovative Education, 10 (2), 165–188.

Rapoport, R. N. (1970). Three dilemmas in action research. Human Relations, 23 (6), 499–513.

Rossi, M., & Sein, M. K. (2003). Design Research workshop: A proactive Research Approach. 26th Information Systems Seminar, Haikko, Finland.

Schein, E. H. (2010). Organization development: Science, technology or philosophy?. In D. Coghlan, & A. B. (Rami) Shani (Eds.), Fundamentals of organization development (1) (pp. 91–100). Sage.

Sein, M. K., Henfridsson, O., Purao, S., Rossi, M. & Lindgren, R. (2011). Action Design Research. MIS Quarterly , 35(1), 37–56

Shani, A. B., & Coghlan, D. (2019). Action research in business and management: A reflective review. Action Research, 19 (3), 1–24.

Shani, A. B., & Pasmore W. A. (1985). Organization inquiry: Towards a new model of the action research process. In D. D Warrick (Ed.), Contemporary organization development: Current thinking and applications. (pp. 438–448). Scott Foresman.

Thiollent, M. (2009). Metodologia da Pesquisa-Ação (17th ed.). Cortez.

Von Kroch, G., Ichijo, K., & Nonaka, I. (2000). Enabling knowledge creation. Oxford University Press.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Wirtschaft/IFZ, Campus Zug-Rotkreuz, Hochschule Luzern, Zug-Rotkreuz, Zug, Switzerland

Stefan Hunziker & Michael Blankenagel

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Stefan Hunziker .

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2024 Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden GmbH, part of Springer Nature

About this chapter

Hunziker, S., Blankenagel, M. (2024). Action Research Design. In: Research Design in Business and Management. Springer Gabler, Wiesbaden. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-42739-9_7

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-42739-9_7

Published : 04 January 2024

Publisher Name : Springer Gabler, Wiesbaden

Print ISBN : 978-3-658-42738-2

Online ISBN : 978-3-658-42739-9

eBook Packages : Business and Management Business and Management (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

4 Preparing for Action Research in the Classroom: Practical Issues

ESSENTIAL QUESTIONS

- What sort of considerations are necessary to take action in your educational context?

- How do you facilitate an action plan without disrupting your teaching?

- How do you respond when the unplanned happens during data collection?

An action research project is a practical endeavor that will ultimately be shaped by your educational context and practice. Now that you have developed a literature review, you are ready to revise your initial plans and begin to plan your project. This chapter will provide some advice about your considerations when undertaking an action research project in your classroom.

Maintain Focus

Hopefully, you found a lot a research on your topic. If so, you will now have a better understanding of how it fits into your area and field of educational research. Even though the topic and area you are researching may not be small, your study itself should clearly focus on one aspect of the topic in your classroom. It is important to maintain clarity about what you are investigating because a lot will be going on simultaneously during the research process and you do not want to spend precious time on erroneous aspects that are irrelevant to your research.

Even though you may view your practice as research, and vice versa, you might want to consider your research project as a projection or megaphone for your work that will bring attention to the small decisions that make a difference in your educational context. From experience, our concern is that you will find that researching one aspect of your practice will reveal other interconnected aspects that you may find interesting, and you will disorient yourself researching in a confluence of interests, commitments, and purposes. We simply want to emphasize – don’t try to research everything at once. Stay focused on your topic, and focus on exploring it in depth, instead of its many related aspects. Once you feel you have made progress in one aspect, you can then progress to other related areas, as new research projects that continue the research cycle.

Identify a Clear Research Question

Your literature review should have exposed you to an array of research questions related to your topic. More importantly, your review should have helped identify which research questions we have addressed as a field, and which ones still need to be addressed . More than likely your research questions will resemble ones from your literature review, while also being distinguishable based upon your own educational context and the unexplored areas of research on your topic.

Regardless of how your research question took shape, it is important to be clear about what you are researching in your educational context. Action research questions typically begin in ways related to “How does … ?” or “How do I/we … ?”, for example:

Research Question Examples

- How does a semi-structured morning meeting improve my classroom community?

- How does historical fiction help students think about people’s agency in the past?

- How do I improve student punctuation use through acting out sentences?

- How do we increase student responsibility for their own learning as a team of teachers?

I particularly favor questions with I or we, because they emphasize that you, the actor and researcher, will be clearly taking action to improve your practice. While this may seem rather easy, you need to be aware of asking the right kind of question. One issue is asking a too pointed and closed question that limits the possibility for analysis. These questions tend to rely on quantitative answers, or yes/no answers. For example, “How many students got a 90% or higher on the exam, after reviewing the material three times?

Another issue is asking a question that is too broad, or that considers too many variables. For example, “How does room temperature affect students’ time-on-task?” These are obviously researchable questions, but the aim is a cause-and-effect relationship between variables that has little or no value to your daily practice.

I also want to point out that your research question will potentially change as the research develops. If you consider the question:

As you do an activity, you may find that students are more comfortable and engaged by acting sentences out in small groups, instead of the whole class. Therefore, your question may shift to:

- How do I improve student punctuation use through acting out sentences, in small groups ?

By simply engaging in the research process and asking questions, you will open your thinking to new possibilities and you will develop new understandings about yourself and the problematic aspects of your educational context.

Understand Your Capabilities and Know that Change Happens Slowly

Similar to your research question, it is important to have a clear and realistic understanding of what is possible to research in your specific educational context. For example, would you be able to address unsatisfactory structures (policies and systems) within your educational context? Probably not immediately, but over time you potentially could. It is much more feasible to think of change happening in smaller increments, from within your own classroom or context, with you as one change agent. For example, you might find it particularly problematic that your school or district places a heavy emphasis on traditional grades, believing that these grades are often not reflective of the skills students have or have not mastered. Instead of attempting to research grading practices across your school or district, your research might instead focus on determining how to provide more meaningful feedback to students and parents about progress in your course. While this project identifies and addresses a structural issue that is part of your school and district context, to keep things manageable, your research project would focus the outcomes on your classroom. The more research you do related to the structure of your educational context the more likely modifications will emerge. The more you understand these modifications in relation to the structural issues you identify within your own context, the more you can influence others by sharing your work and enabling others to understand the modification and address structural issues within their contexts. Throughout your project, you might determine that modifying your grades to be standards-based is more effective than traditional grades, and in turn, that sharing your research outcomes with colleagues at an in-service presentation prompts many to adopt a similar model in their own classrooms. It can be defeating to expect the world to change immediately, but you can provide the spark that ignites coordinated changes. In this way, action research is a powerful methodology for enacting social change. Action research enables individuals to change their own lives, while linking communities of like-minded practitioners who work towards action.

Plan Thoughtfully

Planning thoughtfully involves having a path in mind, but not necessarily having specific objectives. Due to your experience with students and your educational context, the research process will often develop in ways as you expected, but at times it may develop a little differently, which may require you to shift the research focus and change your research question. I will suggest a couple methods to help facilitate this potential shift. First, you may want to develop criteria for gauging the effectiveness of your research process. You may need to refine and modify your criteria and your thinking as you go. For example, we often ask ourselves if action research is encouraging depth of analysis beyond my typical daily pedagogical reflection. You can think about this as you are developing data collection methods and even when you are collecting data. The key distinction is whether the data you will be collecting allows for nuance among the participants or variables. This does not mean that you will have nuance, but it should allow for the possibility. Second, criteria are shaped by our values and develop into standards of judgement. If we identify criteria such as teacher empowerment, then we will use that standard to think about the action contained in our research process. Our values inform our work; therefore, our work should be judged in relation to the relevance of our values in our pedagogy and practice.

Does Your Timeline Work?

While action research is situated in the temporal span that is your life, your research project is short-term, bounded, and related to the socially mediated practices within your educational context. The timeline is important for bounding, or setting limits to your research project, while also making sure you provide the right amount of time for the data to emerge from the process.

For example, if you are thinking about examining the use of math diaries in your classroom, you probably do not want to look at a whole semester of entries because that would be a lot of data, with entries related to a wide range of topics. This would create a huge data analysis endeavor. Therefore, you may want to look at entries from one chapter or unit of study. Also, in terms of timelines, you want to make sure participants have enough time to develop the data you collect. Using the same math example, you would probably want students to have plenty of time to write in the journals, and also space out the entries over the span of the chapter or unit.

In relation to the examples, we think it is an important mind shift to not think of research timelines in terms of deadlines. It is vitally important to provide time and space for the data to emerge from the participants. Therefore, it would be potentially counterproductive to rush a 50-minute data collection into 20 minutes – like all good educators, be flexible in the research process.

Involve Others

It is important to not isolate yourself when doing research. Many educators are already isolated when it comes to practice in their classroom. The research process should be an opportunity to engage with colleagues and open up your classroom to discuss issues that are potentially impacting your entire educational context. Think about the following relationships:

Research participants

You may invite a variety of individuals in your educational context, many with whom you are in a shared situation (e.g. colleagues, administrators). These participants may be part of a collaborative study, they may simply help you develop data collection instruments or intervention items, or they may help to analyze and make sense of the data. While the primary research focus will be you and your learning, you will also appreciate how your learning is potentially influencing the quality of others’ learning.

We always tell educators to be public about your research, or anything exciting that is happening in your educational context, for that matter. In terms of research, you do not want it to seem mysterious to any stakeholder in the educational context. Invite others to visit your setting and observe your research process, and then ask for their formal feedback. Inviting others to your classroom will engage and connect you with other stakeholders, while also showing that your research was established in an ethic of respect for multiple perspectives.

Critical friends or validators

Using critical friends is one way to involve colleagues and also validate your findings and conclusions. While your positionality will shape the research process and subsequently your interpretations of the data, it is important to make sure that others see similar logic in your process and conclusions. Critical friends or validators provide some level of certification that the frameworks you use to develop your research project and make sense of your data are appropriate for your educational context. Your critical friends and validators’ suggestions will be useful if you develop a report or share your findings, but most importantly will provide you confidence moving forward.

Potential researchers

As an educational researcher, you are involved in ongoing improvement plans and district or systemic change. The flexibility of action research allows it to be used in a variety of ways, and your initial research can spark others in your context to engage in research either individually for their own purposes, or collaboratively as a grade level, team, or school. Collaborative inquiry with other educators is an emerging form of professional learning and development for schools with school improvement plans. While they call it collaborative inquiry, these schools are often using an action research model. It is good to think of all of your colleagues as potential research collaborators in the future.

Prioritize Ethical Practice

Try to always be cognizant of your own positionality during the action research process, its relation to your educational context, and any associated power relation to your positionality. Furthermore, you want to make sure that you are not coercing or engaging participants into harmful practices. While this may seem obvious, you may not even realize you are harming your participants because you believe the action is necessary for the research process.

For example, commonly teachers want to try out an intervention that will potentially positively impact their students. When the teacher sets up the action research study, they may have a control group and an experimental group. There is potential to impair the learning of one of these groups if the intervention is either highly impactful or exceedingly worse than the typical instruction. Therefore, teachers can sometimes overlook the potential harm to students in pursuing an experimental method of exploring an intervention.

If you are working with a university researcher, ethical concerns will be covered by the Institutional Review Board (IRB). If not, your school or district may have a process or form that you would need to complete, so it would beneficial to check your district policies before starting. Other widely accepted aspects of doing ethically informed research, include:

Confirm Awareness of Study and Negotiate Access – with authorities, participants and parents, guardians, caregivers and supervisors (with IRB this is done with Informed Consent).

- Promise to Uphold Confidentiality – Uphold confidentiality, to your fullest ability, to protect information, identity and data. You can identify people if they indicate they want to be recognized for their contributions.

- Ensure participants’ rights to withdraw from the study at any point .

- Make sure data is secured, either on password protected computer or lock drawer .

Prepare to Problematize your Thinking

Educational researchers who are more philosophically-natured emphasize that research is not about finding solutions, but instead is about creating and asking new and more precise questions. This is represented in the action research process shown in the diagrams in Chapter 1, as Collingwood (1939) notes the aim in human interaction is always to keep the conversation open, while Edward Said (1997) emphasized that there is no end because whatever we consider an end is actually the beginning of something entirely new. These reflections have perspective in evaluating the quality in research and signifying what is “good” in “good pedagogy” and “good research”. If we consider that action research is about studying and reflecting on one’s learning and how that learning influences practice to improve it, there is nothing to stop your line of inquiry as long as you relate it to improving practice. This is why it is necessary to problematize and scrutinize our practices.

Ethical Dilemmas for Educator-Researchers

Classroom teachers are increasingly expected to demonstrate a disposition of reflection and inquiry into their own practice. Many advocate for schools to become research centers, and to produce their own research studies, which is an important advancement in acknowledging and addressing the complexity in today’s schools. When schools conduct their own research studies without outside involvement, they bypass outside controls over their studies. Schools shift power away from the oversight of outside experts and ethical research responsibilities are shifted to those conducting the formal research within their educational context. Ethics firmly grounded and established in school policies and procedures for teaching, becomes multifaceted when teaching practice and research occur simultaneously. When educators conduct research in their classrooms, are they doing so as teachers or as researchers, and if they are researchers, at what point does the teaching role change to research? Although the notion of objectivity is a key element in traditional research paradigms, educator-based research acknowledges a subjective perspective as the educator-researcher is not viewed separately from the research. In action research, unlike traditional research, the educator as researcher gains access to the research site by the nature of the work they are paid and expected to perform. The educator is never detached from the research and remains at the research site both before and after the study. Because studying one’s practice comprises working with other people, ethical deliberations are inevitable. Educator-researchers confront role conflict and ambiguity regarding ethical issues such as informed consent from participants, protecting subjects (students) from harm, and ensuring confidentiality. They must demonstrate a commitment toward fully understanding ethical dilemmas that present themselves within the unique set of circumstances of the educational context. Questions about research ethics can feel exceedingly complex and in specific situations, educator- researchers require guidance from others.

Think about it this way. As a part-time historian and former history teacher I often problematized who we regard as good and bad people in history. I (Clark) grew up minutes from Jesse James’ childhood farm. Jesse James is a well-documented thief, and possibly by today’s standards, a terrorist. He is famous for daylight bank robberies, as well as the sheer number of successful robberies. When Jesse James was assassinated, by a trusted associate none-the-less, his body travelled the country for people to see, while his assailant and assailant’s brother reenacted the assassination over 1,200 times in theaters across the country. Still today in my hometown, they reenact Jesse James’ daylight bank robbery each year at the Fall Festival, immortalizing this thief and terrorist from our past. This demonstrates how some people saw him as somewhat of hero, or champion of some sort of resistance, both historically and in the present. I find this curious and ripe for further inquiry, but primarily it is problematic for how we think about people as good or bad in the past. Whatever we may individually or collectively think about Jesse James as a “good” or “bad” person in history, it is vitally important to problematize our thinking about him. Talking about Jesse James may seem strange, but it is relevant to the field of action research. If we tell people that we are engaging in important and “good” actions, we should be prepared to justify why it is “good” and provide a theoretical, epistemological, or ontological rationale if possible. Experience is never enough, you need to justify why you act in certain ways and not others, and this includes thinking critically about your own thinking.

Educators who view inquiry and research as a facet of their professional identity must think critically about how to design and conduct research in educational settings to address respect, justice, and beneficence to minimize harm to participants. This chapter emphasized the due diligence involved in ethically planning the collection of data, and in considering the challenges faced by educator-researchers in educational contexts.

Planning Action

After the thinking about the considerations above, you are now at the stage of having selected a topic and reflected on different aspects of that topic. You have undertaken a literature review and have done some reading which has enriched your understanding of your topic. As a result of your reading and further thinking, you may have changed or fine-tuned the topic you are exploring. Now it is time for action. In the last section of this chapter, we will address some practical issues of carrying out action research, drawing on both personal experiences of supervising educator-researchers in different settings and from reading and hearing about action research projects carried out by other researchers.

Engaging in an action research can be a rewarding experience, but a beneficial action research project does not happen by accident – it requires careful planning, a flexible approach, and continuous educator-researcher reflection. Although action research does not have to go through a pre-determined set of steps, it is useful here for you to be aware of the progression which we presented in Chapter 2. The sequence of activities we suggested then could be looked on as a checklist for you to consider before planning the practical aspects of your project.

We also want to provide some questions for you to think about as you are about to begin.

- Have you identified a topic for study?

- What is the specific context for the study? (It may be a personal project for you or for a group of researchers of which you are a member.)

- Have you read a sufficient amount of the relevant literature?

- Have you developed your research question(s)?

- Have you assessed the resource needed to complete the research?

As you start your project, it is worth writing down:

- a working title for your project, which you may need to refine later;

- the background of the study , both in terms of your professional context and personal motivation;

- the aims of the project;

- the specific outcomes you are hoping for.

Although most of the models of action research presented in Chapter 1 suggest action taking place in some pre-defined order, they also allow us the possibility of refining our ideas and action in the light of our experiences and reflections. Changes may need to be made in response to your evaluation and your reflections on how the project is progressing. For example, you might have to make adjustments, taking into account the students’ responses, your observations and any observations of your colleagues. All this is very useful and, in fact, it is one of the features that makes action research suitable for educational research.

Action research planning sheet

In the past, we have provided action researchers with the following planning list that incorporates all of these considerations. Again, like we have said many times, this is in no way definitive, or lock-in-step procedure you need to follow, but instead guidance based on our perspective to help you engage in the action research process. The left column is the simplified version, and the right column offers more specific advice if need.

Figure 4.1 Planning Sheet for Action Research

Action Research Copyright © by J. Spencer Clark; Suzanne Porath; Julie Thiele; and Morgan Jobe is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

short literature review example apa

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Action research (AR) is a methodical process of self-inquiry accomplished by practitioners to unravel work-related problems. This paper analyzed the action research reports (ARRs) in terms of ...

For decades, teacher research, as one form of action research, has been a research methodology that combines theory, practice and improvement of practices in classrooms. However, the lack of teacher autonomy and trust in their professionalism reduces teachers' opportunities to conduct teacher research in their classrooms in many countries.

By tracing action research literature across four subject areas—English language arts (ELA), mathematics, science, and the social studies—it reflects contemporary emphasis on these subjects in the public school "core" curriculum and professional development literature (Brady, 2010) and provides a basis for comparative analysis.The results contribute to the scholarship of teaching ...

Action Research . Dissertation Outline . CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION (Statement of the problem and its significance; brief description of your specific study - i.e., research questions and design) What is your study about - i.e., what problem(s) is your study going to address, how, and why?

Action research is a research method that aims to simultaneously investigate and solve an issue. In other words, as its name suggests, action research conducts research and takes action at the same time. It was first coined as a term in 1944 by MIT professor Kurt Lewin.A highly interactive method, action research is often used in the social ...

The final research output's theme was "Participatory Action Research on the Catholic Engagement with the Environmental Crisis in the Philippines.". Jennifer Ayres' reflections on our vulnerability during these precarious times of the pandemic and ecological crisis ( 2021) inform the paper's view of engaged pedagogy.