- Thesis Action Plan New

- Academic Project Planner

- Literature Navigator

- Thesis Dialogue Blueprint

- Writing Wizard's Template

- Research Proposal Compass

- Why students love us

- Why professors love us

- Why we are different

- All Products

- Coming Soon

Exploring Innovative BBA Final Year Project Topics in Management

Effective BBA Final Year Project Strategies for Marketing Success

Exploring New Dimensions in Anxiety: A PhD Thesis Overview

Navigating Test Anxiety: Insights from Thesis Research in PDF Format

Friends and Thesis Writing: Striking the Right Balance for Your Thesis

Mastering the Art of Communication: Effective Strategies for Voice Your Research in Interviews

Navigating ethical dilemmas: the morality of conducting interviews.

Data Anomalies: Strategies for Analyzing and Interpreting Outlier Data

Navigating the essay structure: where does the thesis statement belong.

In the quest to master essay writing, understanding where to place the thesis statement is crucial. The thesis statement serves as the compass of your essay, guiding readers through your arguments and claims. This article delves into the strategic placement of the thesis statement within an essay's structure, exploring its role, ideal positioning, and the nuances that can affect its effectiveness. Whether you're a seasoned writer or a student learning the ropes, grasping the concept of thesis statement placement will significantly enhance the clarity and impact of your essays.

Key Takeaways

- The thesis statement is a critical component of an essay, encapsulating its main argument or claim.

- Typically, the thesis statement is positioned at the end of the introductory paragraph, setting the stage for the essay.

- Different essay genres and disciplines may require variations in thesis statement placement for optimal reader engagement.

- A well-crafted thesis statement is concise, clear, and specific, guiding the reader through the essay's content.

- Integrating the thesis statement seamlessly with the essay structure ensures coherence and reinforces the argument.

The Role of the Thesis Statement in Essay Composition

Defining the thesis statement.

A thesis statement serves as the guiding beacon of your essay, succinctly presenting your central argument or claim. It is the core assertion that you intend to prove or explain throughout your writing. Think of it as the compass for your essay , directing the reader's attention to the main point you will explore and support with evidence.

The thesis statement typically appears at the end of the introductory paragraph, setting the stage for the body of the essay. It should be clear, concise, and specific, providing a preview of the structure and direction of your argument. Here are some key characteristics of an effective thesis statement:

- It clearly states the topic of your essay and your position on it.

- It is specific enough to be covered in the scope of your essay.

- It is debatable, meaning someone could potentially disagree with it.

- It provides a roadmap for the essay, hinting at how the argument will be constructed.

Remember, the thesis statement is not just a topic—it is your interpretation or perspective on that topic, which you will defend with logic and evidence throughout your essay.

Functions of the Thesis Statement

The thesis statement serves as the compass of your essay, guiding both you and your readers through the terrain of your arguments and ideas. It articulates the purpose and main point of your essay , ensuring that you stay on course and that your readers understand the direction of your argumentation from the outset.

In crafting your thesis statement, you are doing more than simply stating what you will discuss; you are setting the stage for how you will present your evidence, analysis, and insights. The thesis statement acts as a promise to your readers about the scope, direction, and essence of your paper. Here are some key functions of a thesis statement:

- It establishes the focus of your essay and narrows down the topic to a manageable scope.

- It provides a clear and concise summary of the main points or arguments that you will explore.

- It sets expectations for the reader, offering a preview of what is to come in the body of the essay.

Remember, a well-positioned and effectively communicated thesis statement is pivotal to the success of your essay. It is the foundation upon which all other elements are built, and it should be both specific enough to be meaningful and broad enough to allow for a comprehensive discussion within the confines of your essay.

Positioning the Thesis Statement

Understanding where to position your thesis statement within your essay is crucial for setting the stage for your argument. Typically, the thesis statement is placed at the end of the introductory paragraph, serving as a gateway to the body of the essay. This strategic placement allows you to clearly present your main argument or claim before delving into the supporting evidence. It acts as a roadmap for your readers , guiding them through the subsequent discussion and analysis.

In crafting your essay, consider the flow of ideas leading up to the thesis statement. Start with a hook to grab attention, provide some background information, and then introduce your thesis. This progression ensures that by the time your readers encounter the thesis, they have sufficient context to understand its significance. For instance, a website that offers tools like the Thesis Action Plan , Worksheets, and resources can be instrumental in honing your thesis crafting and research strategies.

Remember, the exact position of the thesis statement can vary depending on the length and style of the essay. In longer essays, it may appear after a more extended introduction, while in shorter pieces, it might be more direct. Regardless of its position, the thesis statement should be clear, concise, and well-articulated to effectively anchor your essay's structure.

Strategic Placement of the Thesis Statement

Thesis placement in different essay genres.

The placement of your thesis statement can vary significantly across different essay genres. In a five-paragraph essay , for instance, the thesis typically appears at the end of the introductory paragraph, setting the stage for the arguments to follow. Conversely, in a narrative essay, the thesis may be woven subtly throughout the narrative rather than presented upfront.

Understanding the conventions of each genre is crucial for effective communication. For example, an argumentative essay demands a clear and assertive thesis early on to guide the reader through your points of contention. Below is a list of common essay genres and the typical placement of the thesis statement within them:

- Analytical Essay : Usually at the end of the introduction

- Expository Essay : Often at the end of the first paragraph

- Compare and Contrast Essay : End of the introduction, highlighting the main comparison points

- Persuasive Essay : Close to the beginning, to clearly establish your position

Each genre has its own rhythm and purpose, and the thesis placement should align with the overall structure and intent of the essay. As you write, consider how the placement of your thesis will impact the flow and coherence of your argument.

Cultural and Disciplinary Variations

The thesis statement's placement can be influenced by cultural and disciplinary norms that dictate how an argument should be presented. In some cultures, it is common to state the thesis explicitly at the beginning of an essay to guide the reader. In contrast, other traditions may prefer a more subtle approach, weaving the thesis throughout the discourse. Disciplines also play a role; for example, a literature paper might integrate the thesis more fluidly than a scientific report, which typically states the thesis upfront.

Understanding these variations is crucial for you as a writer. It allows you to tailor your essay to the expectations of your audience, whether they are academics, professionals, or a general readership. To navigate these nuances, it is helpful to engage in how to find literature that exemplifies the conventions of your field or culture. This research can provide insights into the most effective placement of your thesis statement, ensuring that your argument resonates with your intended audience.

Here are some steps to consider when determining the placement of your thesis statement:

- Identify the cultural and disciplinary expectations for thesis placement.

- Analyze exemplar essays and papers within your field to discern patterns.

- Reflect on the purpose of your essay and the impact you wish to achieve.

- Experiment with different placements in drafts to gauge the effectiveness.

By being mindful of these factors, you can enhance the clarity and persuasiveness of your essay, making your thesis statement not just a claim, but a bridge connecting your ideas to the reader's understanding.

Impact of Thesis Placement on Reader Comprehension

The placement of your thesis statement can significantly influence how readers understand and engage with your essay. A strategically positioned thesis statement sets the stage for what is to come and prepares the reader for the arguments and evidence that will follow. Typically, the thesis is located at the end of the introductory paragraph, serving as a bridge to the body of the essay. However, variations exist, and the optimal position may differ based on the essay's purpose and audience.

Consider the following factors when determining the best placement for your thesis statement:

- The genre of the essay and its conventional structure.

- The expectations of your academic discipline or cultural context.

- The complexity of your argument and the need for background information.

By thoughtfully positioning your thesis statement, you enhance the reader's ability to follow your line of reasoning, thereby improving the overall coherence and persuasiveness of your essay. It's essential to weigh these considerations carefully to ensure that your thesis statement fulfills its role as the essay's guiding force.

Crafting an Effective Thesis Statement

Characteristics of a strong thesis.

A strong thesis statement is the backbone of a well-constructed essay. It serves as a beacon, guiding your readers through the arguments and supporting evidence you present. It must be clear and concise , encapsulating your main argument in a way that is easy for readers to grasp. The thesis should be specific enough to give a clear direction to your essay, yet flexible enough to allow for a comprehensive exploration of the topic.

An effective thesis statement also reflects a certain level of complexity, indicating a deep understanding of the subject matter. It should not be a mere statement of fact, but rather an assertion that requires evidence and elaboration. Here are some key characteristics to aim for:

- Arguable: It should invite debate by presenting a viewpoint that can be challenged.

- Supportive: It must be able to be backed up with evidence .

- Focused: It should define the scope of your essay and focus on a specific area of inquiry.

- Insightful: It should provide a unique perspective or imply a new way of understanding the topic.

Common Pitfalls in Thesis Development

As you delve into the intricacies of writing your thesis, it's crucial to be aware of common pitfalls that can undermine the strength of your thesis statement. A thesis may be a single, declarative sentence, yet it can falter if it lacks clarity or specificity. Avoid broad or vague statements that fail to convey the central argument of your essay. Instead, strive for a thesis that is both assertive and focused, providing a clear direction for your essay.

When crafting your thesis, it's essential to how to find research question that is both relevant and compelling. This will serve as the foundation for your argument and guide your research. Here are some steps to ensure your thesis remains robust and effective:

- Begin with a broad exploration of your topic to identify potential angles.

- Narrow down your focus to a specific question that your thesis will address.

- Ensure that your thesis statement directly answers the research question.

- Refine your thesis through multiple drafts, seeking feedback from peers or mentors.

Remember, a well-developed thesis is the cornerstone of a successful essay. It should not only present your argument but also engage your readers, compelling them to read further.

Revising for Clarity and Precision

After drafting your thesis statement, it's crucial to revise for clarity and precision . This process involves stripping away superfluous details and ensuring that your thesis conveys your argument succinctly. Pay particular attention to transition words ; they are the signposts that guide readers through the logic of your argument.

Consider employing the zoom-in-zoom-out technique to balance the big picture with necessary details. Start by zooming out to ensure your thesis addresses the overall argument, then zoom in to refine and articulate the specifics. This technique helps in maintaining the focus and avoiding half-zoomed, abstract statements that lack vividness.

Here are some steps to enhance your thesis statement:

- Organize your thesis to present your ideas logically.

- Revise thoroughly to remove ambiguities.

- Cite sources properly to bolster credibility.

- Seek feedback to polish your thesis journey.

Remember, a well-crafted thesis statement is the cornerstone of an impactful essay. It's worth investing the time to revise and perfect it.

Integrating the Thesis Statement with Essay Structure

Thesis-centric paragraph development.

When constructing your essay, each paragraph should serve as a building block, contributing to the overall argument presented by your thesis statement . Develop paragraphs that revolve around your thesis , ensuring that each one introduces a distinct idea or piece of evidence that supports your central argument. This approach not only strengthens the coherence of your essay but also reinforces the reader's understanding of your thesis as they progress through your writing.

Consider the following structure for each paragraph:

- A topic sentence that clearly relates to the thesis.

- Supporting sentences with evidence, examples, or arguments.

- A concluding sentence that ties the paragraph back to the thesis and transitions smoothly to the next point.

By adhering to this format, you create a logical flow that guides the reader through your essay, making your argument more persuasive and easier to follow. The strategic use of transitions is crucial; they act as signposts that help navigate the reader from one idea to the next, maintaining the momentum of your thesis-driven narrative.

Transitions and Signposting

As you weave your ideas together in your essay, transitions play a pivotal role in maintaining the flow and coherence of your writing. These linguistic signposts guide the reader through your argument, ensuring that each point seamlessly connects to the next. Consider the following list of transition words and phrases to enhance the readability of your essay:

In addition to single words, phrases such as "in light of the foregoing" or "given these points" can also serve as effective transitions. It's important to use these elements judiciously; overuse can lead to a cluttered and repetitive text, while underuse may leave your reader lost in a maze of disjointed thoughts. Striking the right balance is key to a well-structured essay. Remember, transitions are not just decorative; they are essential in articulating the logical structure of your argument and in reinforcing the cohesion of your thesis statement throughout the essay.

Ensuring Coherence and Unity

To ensure that your essay resonates with coherence and unity, it is essential to weave your thesis statement seamlessly throughout your work. Transition words play a pivotal role in this process, as they help to signal connections between ideas, guiding the reader through your argument with ease. Consider using words like however , therefore , and thus to articulate the logical flow of your essay.

In addition to transition words, it is crucial to maintain a consistent voice and tone throughout your essay. Avoid introducing new themes or diverging from your central thesis, as this can disrupt the unity of your composition. Instead, focus on reinforcing your thesis by aligning each paragraph's topic sentence with the overarching argument. This alignment ensures that every section of your essay contributes to the development of your thesis, reinforcing the essay's overall coherence.

Lastly, remember to review your essay for any redundant or off-topic information that may detract from its unity. By removing minor details that do not support your thesis, you can sharpen the focus and strengthen the impact of your argument. The goal is to present a unified piece of writing where each element, from individual words to entire paragraphs, serves the purpose of advancing your thesis.

Advanced Considerations for Thesis Statements

Thesis statements in complex arguments.

In the realm of complex arguments, the thesis statement serves as the compass that guides the reader through the intricacies of your reasoning. It must be robust enough to unify the various strands of argumentation while remaining clear and concise. When crafting a thesis for a complex argument, consider the following steps:

- Begin by identifying the central question or problem your essay addresses.

- Synthesize the main points that will form the pillars of your argument.

- Ensure that your thesis encapsulates the essence of these points in a single, coherent statement.

Remember, the cohesion of your argument relies heavily on the strength of your thesis. As you delve into detailed evidence and examples, your thesis should remain the steadfast anchor, keeping your essay's purpose in sharp focus. In complex essays, where multiple perspectives and nuances are explored, revisiting and refining your thesis becomes an iterative process. This ensures that as your argument evolves, your thesis accurately reflects the depth and breadth of your analysis.

Balancing Specificity and Scope

In crafting your thesis statement, you must strike a delicate balance between specificity and scope. A thesis that is too broad may lack focus, while one that is too narrow might not allow for a comprehensive exploration of the topic. To achieve this equilibrium, consider the following points:

- Identify the core idea you wish to convey and ensure it is neither too general nor excessively detailed.

- Reflect on the relevance of your thesis to the broader field of study, and whether it contributes new insights or perspectives.

- Adjust the scope of your thesis to align with the length and depth of your essay; a shorter essay will require a more focused thesis, whereas a longer piece can explore a wider range of issues.

Remember, the specificity of your thesis should illuminate the path of your argument, guiding the reader through your essay with clarity and purpose. Conversely, the scope of your thesis determines the breadth of discussion, allowing you to engage with the topic comprehensively without becoming overwhelmed by its complexities.

The Evolving Thesis in the Writing Process

As you embark on the journey of essay composition, it's essential to understand that your thesis statement is not set in stone. The process of writing is dynamic, and your thesis will likely undergo transformation as you gain deeper insights into your topic. This evolution is a natural and beneficial aspect of scholarly work, reflecting your growing expertise and nuanced understanding of the subject matter.

Recognize that your thesis may evolve as you delve deeper into research and analysis, adjusting to new insights. This iterative process can be both exhilarating and daunting, potentially leading to thesis anxiety . However, embracing the fluidity of your thesis can result in a more robust and compelling argument. To manage this evolution effectively, consider the following steps:

- Begin with a provisional thesis that guides your initial research.

- Stay open to new perspectives and evidence that may challenge your assumptions.

- Revise your thesis as necessary, ensuring it remains aligned with your developing argument.

By acknowledging and anticipating changes to your thesis, you can mitigate anxiety and channel your efforts into producing a refined and persuasive essay.

Delving into 'Advanced Considerations for Thesis Statements' can elevate your academic writing to new heights. Our comprehensive guide on the subject is a must-read for any serious scholar. However, if you're encountering access issues, we're here to help. Visit our website for troubleshooting tips and expert advice. Don't let technical difficulties hinder your progress—take the next step in perfecting your thesis statement today!

In conclusion, the thesis statement is a pivotal element of essay structure, serving as the compass that guides the reader through the intellectual journey of the essay. It is typically positioned at the end of the introduction, where it succinctly presents the central argument or claim, setting the stage for the ensuing discussion. The placement of the thesis statement is not merely a matter of formality but a strategic choice that enhances the clarity and coherence of the essay. As we have explored throughout this article, understanding where the thesis statement belongs is crucial for students and scholars alike, as it underpins the effectiveness of their academic writing. By mastering the art of thesis placement, writers can ensure that their essays are well-organized and persuasive, reflecting a clear and logical progression of ideas.

Frequently Asked Questions

Where does the thesis statement typically belong in an essay.

The thesis statement usually belongs at the end of the introduction paragraph, providing a clear and concise statement of the main argument or claim of the essay.

Can the thesis statement be more than one sentence?

Yes, while often a single sentence, the thesis statement can be extended into two sentences if it improves clarity or allows for a more detailed presentation of the argument.

Is the placement of the thesis statement the same across all disciplines?

No, the placement can vary depending on cultural and disciplinary conventions. It's important to understand the expectations of your specific academic field.

How does the placement of the thesis statement affect reader comprehension?

Strategic placement of the thesis statement at the beginning of the essay sets the tone and provides a roadmap for the reader, enhancing comprehension and engagement.

What are some common pitfalls in thesis statement development?

Common pitfalls include being too vague, too broad, lacking specificity, or not being arguable. A good thesis statement should be clear, focused, and contestable.

Can the thesis statement evolve during the writing process?

Yes, the thesis statement can and often should evolve as you refine your ideas and develop your arguments throughout the writing process.

- Rebels Blog

- Blog Articles

- Terms and Conditions

- Payment and Shipping Terms

- Privacy Policy

- Return Policy

© 2024 Research Rebels, All rights reserved.

Your cart is currently empty.

What are your chances of acceptance?

Calculate for all schools, your chance of acceptance.

Your chancing factors

Extracurriculars.

How to Write a Strong Thesis Statement: 4 Steps + Examples

What’s Covered:

What is the purpose of a thesis statement, writing a good thesis statement: 4 steps, common pitfalls to avoid, where to get your essay edited for free.

When you set out to write an essay, there has to be some kind of point to it, right? Otherwise, your essay would just be a big jumble of word salad that makes absolutely no sense. An essay needs a central point that ties into everything else. That main point is called a thesis statement, and it’s the core of any essay or research paper.

You may hear about Master degree candidates writing a thesis, and that is an entire paper–not to be confused with the thesis statement, which is typically one sentence that contains your paper’s focus.

Read on to learn more about thesis statements and how to write them. We’ve also included some solid examples for you to reference.

Typically the last sentence of your introductory paragraph, the thesis statement serves as the roadmap for your essay. When your reader gets to the thesis statement, they should have a clear outline of your main point, as well as the information you’ll be presenting in order to either prove or support your point.

The thesis statement should not be confused for a topic sentence , which is the first sentence of every paragraph in your essay. If you need help writing topic sentences, numerous resources are available. Topic sentences should go along with your thesis statement, though.

Since the thesis statement is the most important sentence of your entire essay or paper, it’s imperative that you get this part right. Otherwise, your paper will not have a good flow and will seem disjointed. That’s why it’s vital not to rush through developing one. It’s a methodical process with steps that you need to follow in order to create the best thesis statement possible.

Step 1: Decide what kind of paper you’re writing

When you’re assigned an essay, there are several different types you may get. Argumentative essays are designed to get the reader to agree with you on a topic. Informative or expository essays present information to the reader. Analytical essays offer up a point and then expand on it by analyzing relevant information. Thesis statements can look and sound different based on the type of paper you’re writing. For example:

- Argumentative: The United States needs a viable third political party to decrease bipartisanship, increase options, and help reduce corruption in government.

- Informative: The Libertarian party has thrown off elections before by gaining enough support in states to get on the ballot and by taking away crucial votes from candidates.

- Analytical: An analysis of past presidential elections shows that while third party votes may have been the minority, they did affect the outcome of the elections in 2020, 2016, and beyond.

Step 2: Figure out what point you want to make

Once you know what type of paper you’re writing, you then need to figure out the point you want to make with your thesis statement, and subsequently, your paper. In other words, you need to decide to answer a question about something, such as:

- What impact did reality TV have on American society?

- How has the musical Hamilton affected perception of American history?

- Why do I want to major in [chosen major here]?

If you have an argumentative essay, then you will be writing about an opinion. To make it easier, you may want to choose an opinion that you feel passionate about so that you’re writing about something that interests you. For example, if you have an interest in preserving the environment, you may want to choose a topic that relates to that.

If you’re writing your college essay and they ask why you want to attend that school, you may want to have a main point and back it up with information, something along the lines of:

“Attending Harvard University would benefit me both academically and professionally, as it would give me a strong knowledge base upon which to build my career, develop my network, and hopefully give me an advantage in my chosen field.”

Step 3: Determine what information you’ll use to back up your point

Once you have the point you want to make, you need to figure out how you plan to back it up throughout the rest of your essay. Without this information, it will be hard to either prove or argue the main point of your thesis statement. If you decide to write about the Hamilton example, you may decide to address any falsehoods that the writer put into the musical, such as:

“The musical Hamilton, while accurate in many ways, leaves out key parts of American history, presents a nationalist view of founding fathers, and downplays the racism of the times.”

Once you’ve written your initial working thesis statement, you’ll then need to get information to back that up. For example, the musical completely leaves out Benjamin Franklin, portrays the founding fathers in a nationalist way that is too complimentary, and shows Hamilton as a staunch abolitionist despite the fact that his family likely did own slaves.

Step 4: Revise and refine your thesis statement before you start writing

Read through your thesis statement several times before you begin to compose your full essay. You need to make sure the statement is ironclad, since it is the foundation of the entire paper. Edit it or have a peer review it for you to make sure everything makes sense and that you feel like you can truly write a paper on the topic. Once you’ve done that, you can then begin writing your paper.

When writing a thesis statement, there are some common pitfalls you should avoid so that your paper can be as solid as possible. Make sure you always edit the thesis statement before you do anything else. You also want to ensure that the thesis statement is clear and concise. Don’t make your reader hunt for your point. Finally, put your thesis statement at the end of the first paragraph and have your introduction flow toward that statement. Your reader will expect to find your statement in its traditional spot.

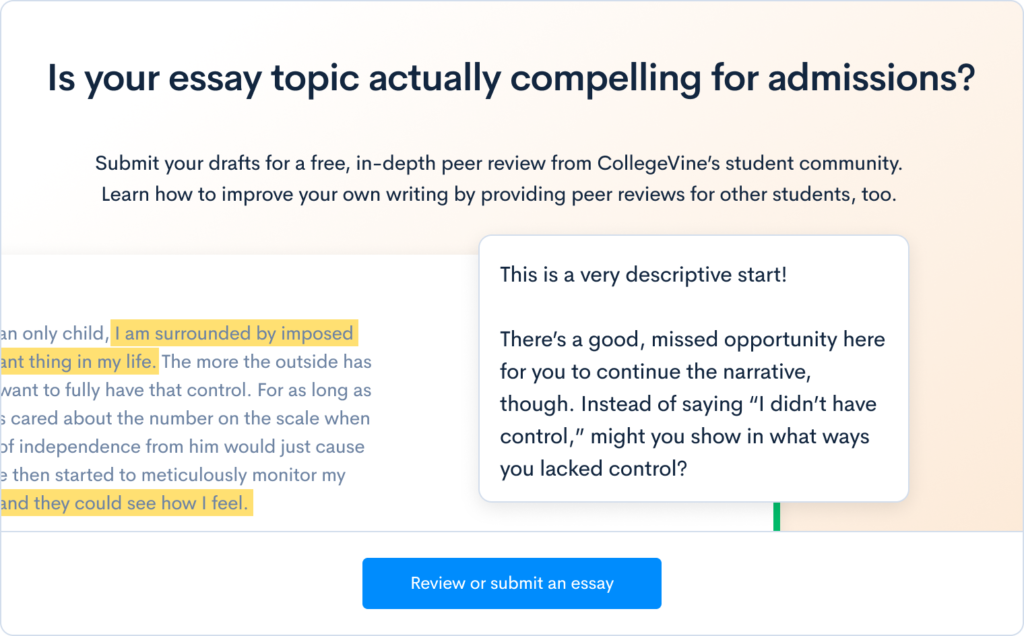

If you’re having trouble getting started, or need some guidance on your essay, there are tools available that can help you. CollegeVine offers a free peer essay review tool where one of your peers can read through your essay and provide you with valuable feedback. Getting essay feedback from a peer can help you wow your instructor or college admissions officer with an impactful essay that effectively illustrates your point.

Related CollegeVine Blog Posts

Reference management. Clean and simple.

How to write a thesis statement + examples

What is a thesis statement?

Is a thesis statement a question, how do you write a good thesis statement, how do i know if my thesis statement is good, examples of thesis statements, helpful resources on how to write a thesis statement, frequently asked questions about writing a thesis statement, related articles.

A thesis statement is the main argument of your paper or thesis.

The thesis statement is one of the most important elements of any piece of academic writing . It is a brief statement of your paper’s main argument. Essentially, you are stating what you will be writing about.

You can see your thesis statement as an answer to a question. While it also contains the question, it should really give an answer to the question with new information and not just restate or reiterate it.

Your thesis statement is part of your introduction. Learn more about how to write a good thesis introduction in our introduction guide .

A thesis statement is not a question. A statement must be arguable and provable through evidence and analysis. While your thesis might stem from a research question, it should be in the form of a statement.

Tip: A thesis statement is typically 1-2 sentences. For a longer project like a thesis, the statement may be several sentences or a paragraph.

A good thesis statement needs to do the following:

- Condense the main idea of your thesis into one or two sentences.

- Answer your project’s main research question.

- Clearly state your position in relation to the topic .

- Make an argument that requires support or evidence.

Once you have written down a thesis statement, check if it fulfills the following criteria:

- Your statement needs to be provable by evidence. As an argument, a thesis statement needs to be debatable.

- Your statement needs to be precise. Do not give away too much information in the thesis statement and do not load it with unnecessary information.

- Your statement cannot say that one solution is simply right or simply wrong as a matter of fact. You should draw upon verified facts to persuade the reader of your solution, but you cannot just declare something as right or wrong.

As previously mentioned, your thesis statement should answer a question.

If the question is:

What do you think the City of New York should do to reduce traffic congestion?

A good thesis statement restates the question and answers it:

In this paper, I will argue that the City of New York should focus on providing exclusive lanes for public transport and adaptive traffic signals to reduce traffic congestion by the year 2035.

Here is another example. If the question is:

How can we end poverty?

A good thesis statement should give more than one solution to the problem in question:

In this paper, I will argue that introducing universal basic income can help reduce poverty and positively impact the way we work.

- The Writing Center of the University of North Carolina has a list of questions to ask to see if your thesis is strong .

A thesis statement is part of the introduction of your paper. It is usually found in the first or second paragraph to let the reader know your research purpose from the beginning.

In general, a thesis statement should have one or two sentences. But the length really depends on the overall length of your project. Take a look at our guide about the length of thesis statements for more insight on this topic.

Here is a list of Thesis Statement Examples that will help you understand better how to write them.

Every good essay should include a thesis statement as part of its introduction, no matter the academic level. Of course, if you are a high school student you are not expected to have the same type of thesis as a PhD student.

Here is a great YouTube tutorial showing How To Write An Essay: Thesis Statements .

Think of yourself as a member of a jury, listening to a lawyer who is presenting an opening argument. You'll want to know very soon whether the lawyer believes the accused to be guilty or not guilty, and how the lawyer plans to convince you. Readers of academic essays are like jury members: before they have read too far, they want to know what the essay argues as well as how the writer plans to make the argument. After reading your thesis statement, the reader should think, "This essay is going to try to convince me of something. I'm not convinced yet, but I'm interested to see how I might be."

An effective thesis cannot be answered with a simple "yes" or "no." A thesis is not a topic; nor is it a fact; nor is it an opinion. "Reasons for the fall of communism" is a topic. "Communism collapsed in Eastern Europe" is a fact known by educated people. "The fall of communism is the best thing that ever happened in Europe" is an opinion. (Superlatives like "the best" almost always lead to trouble. It's impossible to weigh every "thing" that ever happened in Europe. And what about the fall of Hitler? Couldn't that be "the best thing"?)

A good thesis has two parts. It should tell what you plan to argue, and it should "telegraph" how you plan to argue—that is, what particular support for your claim is going where in your essay.

Steps in Constructing a Thesis

First, analyze your primary sources. Look for tension, interest, ambiguity, controversy, and/or complication. Does the author contradict himself or herself? Is a point made and later reversed? What are the deeper implications of the author's argument? Figuring out the why to one or more of these questions, or to related questions, will put you on the path to developing a working thesis. (Without the why, you probably have only come up with an observation—that there are, for instance, many different metaphors in such-and-such a poem—which is not a thesis.)

Once you have a working thesis, write it down. There is nothing as frustrating as hitting on a great idea for a thesis, then forgetting it when you lose concentration. And by writing down your thesis you will be forced to think of it clearly, logically, and concisely. You probably will not be able to write out a final-draft version of your thesis the first time you try, but you'll get yourself on the right track by writing down what you have.

Keep your thesis prominent in your introduction. A good, standard place for your thesis statement is at the end of an introductory paragraph, especially in shorter (5-15 page) essays. Readers are used to finding theses there, so they automatically pay more attention when they read the last sentence of your introduction. Although this is not required in all academic essays, it is a good rule of thumb.

Anticipate the counterarguments. Once you have a working thesis, you should think about what might be said against it. This will help you to refine your thesis, and it will also make you think of the arguments that you'll need to refute later on in your essay. (Every argument has a counterargument. If yours doesn't, then it's not an argument—it may be a fact, or an opinion, but it is not an argument.)

This statement is on its way to being a thesis. However, it is too easy to imagine possible counterarguments. For example, a political observer might believe that Dukakis lost because he suffered from a "soft-on-crime" image. If you complicate your thesis by anticipating the counterargument, you'll strengthen your argument, as shown in the sentence below.

Some Caveats and Some Examples

A thesis is never a question. Readers of academic essays expect to have questions discussed, explored, or even answered. A question ("Why did communism collapse in Eastern Europe?") is not an argument, and without an argument, a thesis is dead in the water.

A thesis is never a list. "For political, economic, social and cultural reasons, communism collapsed in Eastern Europe" does a good job of "telegraphing" the reader what to expect in the essay—a section about political reasons, a section about economic reasons, a section about social reasons, and a section about cultural reasons. However, political, economic, social and cultural reasons are pretty much the only possible reasons why communism could collapse. This sentence lacks tension and doesn't advance an argument. Everyone knows that politics, economics, and culture are important.

A thesis should never be vague, combative or confrontational. An ineffective thesis would be, "Communism collapsed in Eastern Europe because communism is evil." This is hard to argue (evil from whose perspective? what does evil mean?) and it is likely to mark you as moralistic and judgmental rather than rational and thorough. It also may spark a defensive reaction from readers sympathetic to communism. If readers strongly disagree with you right off the bat, they may stop reading.

An effective thesis has a definable, arguable claim. "While cultural forces contributed to the collapse of communism in Eastern Europe, the disintegration of economies played the key role in driving its decline" is an effective thesis sentence that "telegraphs," so that the reader expects the essay to have a section about cultural forces and another about the disintegration of economies. This thesis makes a definite, arguable claim: that the disintegration of economies played a more important role than cultural forces in defeating communism in Eastern Europe. The reader would react to this statement by thinking, "Perhaps what the author says is true, but I am not convinced. I want to read further to see how the author argues this claim."

A thesis should be as clear and specific as possible. Avoid overused, general terms and abstractions. For example, "Communism collapsed in Eastern Europe because of the ruling elite's inability to address the economic concerns of the people" is more powerful than "Communism collapsed due to societal discontent."

Copyright 1999, Maxine Rodburg and The Tutors of the Writing Center at Harvard University

Thesis Statements

What this handout is about.

This handout describes what a thesis statement is, how thesis statements work in your writing, and how you can craft or refine one for your draft.

Introduction

Writing in college often takes the form of persuasion—convincing others that you have an interesting, logical point of view on the subject you are studying. Persuasion is a skill you practice regularly in your daily life. You persuade your roommate to clean up, your parents to let you borrow the car, your friend to vote for your favorite candidate or policy. In college, course assignments often ask you to make a persuasive case in writing. You are asked to convince your reader of your point of view. This form of persuasion, often called academic argument, follows a predictable pattern in writing. After a brief introduction of your topic, you state your point of view on the topic directly and often in one sentence. This sentence is the thesis statement, and it serves as a summary of the argument you’ll make in the rest of your paper.

What is a thesis statement?

A thesis statement:

- tells the reader how you will interpret the significance of the subject matter under discussion.

- is a road map for the paper; in other words, it tells the reader what to expect from the rest of the paper.

- directly answers the question asked of you. A thesis is an interpretation of a question or subject, not the subject itself. The subject, or topic, of an essay might be World War II or Moby Dick; a thesis must then offer a way to understand the war or the novel.

- makes a claim that others might dispute.

- is usually a single sentence near the beginning of your paper (most often, at the end of the first paragraph) that presents your argument to the reader. The rest of the paper, the body of the essay, gathers and organizes evidence that will persuade the reader of the logic of your interpretation.

If your assignment asks you to take a position or develop a claim about a subject, you may need to convey that position or claim in a thesis statement near the beginning of your draft. The assignment may not explicitly state that you need a thesis statement because your instructor may assume you will include one. When in doubt, ask your instructor if the assignment requires a thesis statement. When an assignment asks you to analyze, to interpret, to compare and contrast, to demonstrate cause and effect, or to take a stand on an issue, it is likely that you are being asked to develop a thesis and to support it persuasively. (Check out our handout on understanding assignments for more information.)

How do I create a thesis?

A thesis is the result of a lengthy thinking process. Formulating a thesis is not the first thing you do after reading an essay assignment. Before you develop an argument on any topic, you have to collect and organize evidence, look for possible relationships between known facts (such as surprising contrasts or similarities), and think about the significance of these relationships. Once you do this thinking, you will probably have a “working thesis” that presents a basic or main idea and an argument that you think you can support with evidence. Both the argument and your thesis are likely to need adjustment along the way.

Writers use all kinds of techniques to stimulate their thinking and to help them clarify relationships or comprehend the broader significance of a topic and arrive at a thesis statement. For more ideas on how to get started, see our handout on brainstorming .

How do I know if my thesis is strong?

If there’s time, run it by your instructor or make an appointment at the Writing Center to get some feedback. Even if you do not have time to get advice elsewhere, you can do some thesis evaluation of your own. When reviewing your first draft and its working thesis, ask yourself the following :

- Do I answer the question? Re-reading the question prompt after constructing a working thesis can help you fix an argument that misses the focus of the question. If the prompt isn’t phrased as a question, try to rephrase it. For example, “Discuss the effect of X on Y” can be rephrased as “What is the effect of X on Y?”

- Have I taken a position that others might challenge or oppose? If your thesis simply states facts that no one would, or even could, disagree with, it’s possible that you are simply providing a summary, rather than making an argument.

- Is my thesis statement specific enough? Thesis statements that are too vague often do not have a strong argument. If your thesis contains words like “good” or “successful,” see if you could be more specific: why is something “good”; what specifically makes something “successful”?

- Does my thesis pass the “So what?” test? If a reader’s first response is likely to be “So what?” then you need to clarify, to forge a relationship, or to connect to a larger issue.

- Does my essay support my thesis specifically and without wandering? If your thesis and the body of your essay do not seem to go together, one of them has to change. It’s okay to change your working thesis to reflect things you have figured out in the course of writing your paper. Remember, always reassess and revise your writing as necessary.

- Does my thesis pass the “how and why?” test? If a reader’s first response is “how?” or “why?” your thesis may be too open-ended and lack guidance for the reader. See what you can add to give the reader a better take on your position right from the beginning.

Suppose you are taking a course on contemporary communication, and the instructor hands out the following essay assignment: “Discuss the impact of social media on public awareness.” Looking back at your notes, you might start with this working thesis:

Social media impacts public awareness in both positive and negative ways.

You can use the questions above to help you revise this general statement into a stronger thesis.

- Do I answer the question? You can analyze this if you rephrase “discuss the impact” as “what is the impact?” This way, you can see that you’ve answered the question only very generally with the vague “positive and negative ways.”

- Have I taken a position that others might challenge or oppose? Not likely. Only people who maintain that social media has a solely positive or solely negative impact could disagree.

- Is my thesis statement specific enough? No. What are the positive effects? What are the negative effects?

- Does my thesis pass the “how and why?” test? No. Why are they positive? How are they positive? What are their causes? Why are they negative? How are they negative? What are their causes?

- Does my thesis pass the “So what?” test? No. Why should anyone care about the positive and/or negative impact of social media?

After thinking about your answers to these questions, you decide to focus on the one impact you feel strongly about and have strong evidence for:

Because not every voice on social media is reliable, people have become much more critical consumers of information, and thus, more informed voters.

This version is a much stronger thesis! It answers the question, takes a specific position that others can challenge, and it gives a sense of why it matters.

Let’s try another. Suppose your literature professor hands out the following assignment in a class on the American novel: Write an analysis of some aspect of Mark Twain’s novel Huckleberry Finn. “This will be easy,” you think. “I loved Huckleberry Finn!” You grab a pad of paper and write:

Mark Twain’s Huckleberry Finn is a great American novel.

You begin to analyze your thesis:

- Do I answer the question? No. The prompt asks you to analyze some aspect of the novel. Your working thesis is a statement of general appreciation for the entire novel.

Think about aspects of the novel that are important to its structure or meaning—for example, the role of storytelling, the contrasting scenes between the shore and the river, or the relationships between adults and children. Now you write:

In Huckleberry Finn, Mark Twain develops a contrast between life on the river and life on the shore.

- Do I answer the question? Yes!

- Have I taken a position that others might challenge or oppose? Not really. This contrast is well-known and accepted.

- Is my thesis statement specific enough? It’s getting there–you have highlighted an important aspect of the novel for investigation. However, it’s still not clear what your analysis will reveal.

- Does my thesis pass the “how and why?” test? Not yet. Compare scenes from the book and see what you discover. Free write, make lists, jot down Huck’s actions and reactions and anything else that seems interesting.

- Does my thesis pass the “So what?” test? What’s the point of this contrast? What does it signify?”

After examining the evidence and considering your own insights, you write:

Through its contrasting river and shore scenes, Twain’s Huckleberry Finn suggests that to find the true expression of American democratic ideals, one must leave “civilized” society and go back to nature.

This final thesis statement presents an interpretation of a literary work based on an analysis of its content. Of course, for the essay itself to be successful, you must now present evidence from the novel that will convince the reader of your interpretation.

Works consulted

We consulted these works while writing this handout. This is not a comprehensive list of resources on the handout’s topic, and we encourage you to do your own research to find additional publications. Please do not use this list as a model for the format of your own reference list, as it may not match the citation style you are using. For guidance on formatting citations, please see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial . We revise these tips periodically and welcome feedback.

Anson, Chris M., and Robert A. Schwegler. 2010. The Longman Handbook for Writers and Readers , 6th ed. New York: Longman.

Lunsford, Andrea A. 2015. The St. Martin’s Handbook , 8th ed. Boston: Bedford/St Martin’s.

Ramage, John D., John C. Bean, and June Johnson. 2018. The Allyn & Bacon Guide to Writing , 8th ed. New York: Pearson.

Ruszkiewicz, John J., Christy Friend, Daniel Seward, and Maxine Hairston. 2010. The Scott, Foresman Handbook for Writers , 9th ed. Boston: Pearson Education.

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout and attribute the source: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Make a Gift

How to Write a Good Thesis Statement

Creating the core of your essay

- Ph.D., Rhetoric and English, University of Georgia

- M.A., Modern English and American Literature, University of Leicester

- B.A., English, State University of New York

In composition and academic writing , a thesis statement (or controlling idea) is a sentence in an essay, report, research paper, or speech that identifies the main idea and/or central purpose of the text. In rhetoric, a claim is similar to a thesis.

For students especially, crafting a thesis statement can be a challenge, but it's important to know how to write one because a thesis statement is the heart of any essay you write. Here are some tips and examples to follow.

Purpose of the Thesis Statement

The thesis statement serves as the organizing principle of the text and appears in the introductory paragraph . It is not a mere statement of fact. Rather, it is an idea, a claim, or an interpretation, one that others may dispute. Your job as a writer is to persuade the reader—through the careful use of examples and thoughtful analysis—that your argument is a valid one.

A thesis statement is, essentially, the idea that the rest of your paper will support. Perhaps it is an opinion that you have marshaled logical arguments in favor of. Perhaps it is a synthesis of ideas and research that you have distilled into one point, and the rest of your paper will unpack it and present factual examples to show how you arrived at this idea. The one thing a thesis statement should not be? An obvious or indisputable fact. If your thesis is simple and obvious, there is little for you to argue, since no one will need your assembled evidence to buy into your statement.

Developing Your Argument

Your thesis is the most important part of your writing. Before you begin writing, you'll want to follow these tips for developing a good thesis statement:

- Read and compare your sources : What are the main points they make? Do your sources conflict with one another? Don't just summarize your sources' claims; look for the motivation behind their motives.

- Draft your thesis : Good ideas are rarely born fully formed. They need to be refined. By committing your thesis to paper, you'll be able to refine it as you research and draft your essay.

- Consider the other side : Just like a court case, every argument has two sides. You'll be able to refine your thesis by considering the counterclaims and refuting them in your essay, or even acknowledging them in a clause in your thesis.

Be Clear and Concise

An effective thesis should answer the reader question, "So what?" It should not be more than a sentence or two. Don't be vague, or your reader won't care. Specificity is also important. Rather than make a broad, blanket statement, try a complex sentence that includes a clause giving more context , acknowledging a contrast, or offering examples of the general points you're going to make.

Incorrect : British indifference caused the American Revolution .

Correct : By treating their U.S. colonies as little more than a source of revenue and limiting colonists' political rights, British indifference contributed to the start of the American Revolution .

In the first version, the statement is very general. It offers an argument, but no idea of how the writer is going to get us there or what specific forms that "indifference" took. It's also rather simplistic, arguing that there was a singular cause of the American Revolution. The second version shows us a road map of what to expect in the essay: an argument that will use specific historical examples to prove how British indifference was important to (but not the sole cause of) the American Revolution. Specificity and scope are crucial to forming a strong thesis statement, which in turn helps you write a stronger paper!

Make a Statement

Although you do want to grab your reader's attention, asking a question is not the same as making a thesis statement. Your job is to persuade by presenting a clear, concise concept that explains both how and why.

Incorrect : Have you ever wondered why Thomas Edison gets all the credit for the light bulb?

Correct : His savvy self-promotion and ruthless business tactics cemented Thomas Edison's legacy, not the invention of the lightbulb itself.

Asking a question is not a total no-go, but it doesn't belong in the thesis statement. Remember, in most formal essay, a thesis statement will be the last sentence of the introductory paragraph. You might use a question as the attention-grabbing first or second sentence instead.

Don't Be Confrontational

Although you are trying to prove a point, you are not trying to force your will on the reader.

Incorrect : The stock market crash of 1929 wiped out many small investors who were financially inept and deserved to lose their money.

Correct : While a number of economic factors caused the stock market crash of 1929, the losses were made worse by uninformed first-time investors who made poor financial decisions.

It's really an extension of correct academic writing voice . While you might informally argue that some of the investors of the 1920s "deserved" to lose their money, that's not the kind of argument that belongs in formal essay writing. Instead, a well-written essay will make a similar point, but focus more on cause and effect, rather that impolite or blunt emotions.

- 100 Persuasive Essay Topics

- An Introduction to Academic Writing

- How to Write a Solid Thesis Statement

- The Introductory Paragraph: Start Your Paper Off Right

- How To Write an Essay

- Tips for Writing an Art History Paper

- The Ultimate Guide to the 5-Paragraph Essay

- Tips on How to Write an Argumentative Essay

- What Is Expository Writing?

- Thesis: Definition and Examples in Composition

- How to Write a Persuasive Essay

- Definition and Examples of Analysis in Composition

- Write an Attention-Grabbing Opening Sentence for an Essay

- How to Start a Book Report

- How to Write a Response Paper

- The Five Steps of Writing an Essay

- The Student Experience

- Financial Aid

- Degree Finder

- Undergraduate Arts & Sciences

- Departments and Programs

- Research, Scholarship & Creativity

- Centers & Institutes

- Geisel School of Medicine

- Guarini School of Graduate & Advanced Studies

- Thayer School of Engineering

- Tuck School of Business

Campus Life

- Diversity & Inclusion

- Athletics & Recreation

- Student Groups & Activities

- Residential Life

- [email protected] Contact & Department Info Mail

- About the Writing Center

- Hours & Location

- Appointments

- Undergraduate Sessions

- Graduate Sessions

- What To Expect at a Session

- Student Guides

- Guide for Students with Disabilities

- Sources and Citations Guide

- For Faculty

- Class Support

- Faculty Guidelines

- Work With Us

- Apply To Tutor

- Advice for Tutors

- Advice to Writing Assistants

- Diagnosing Problems: Ways of Reading Student Papers

- Responding to Problems: A Facilitative Approach

- Teaching Writing as a Process

Search form

- About Tutoring

The Thesis Sentence

The thesis sentence is arguably the most important sentence in an academic paper. Without a good, clear thesis that presents an intriguing arguable point, a paper risks becoming unfocused, aimless, not worth the reader's time.

The Challenge of the Thesis Sentence

Because the thesis sentence is the most important sentence of a paper, it is also the most difficult to write. Readers expect a great deal of a thesis sentence: they want it to powerfully and clearly indicate what the writer is going to say, why she is going to say it, and even how it is that she is going to go about getting it said. In other words, the job of the thesis sentence is to organize, predict, control, and define the paper's argument.

In many cases, a thesis sentence will not only present the paper's argument, it will also point to and direct the course that the argument is going to take. In other words, it may also include an "essay map" - i.e., phrases or clauses that map out for the reader (and the writer) the argument that is to come. In some cases, then, the thesis sentence not only promises an argument, it promises the structure of that argument as well.

The promises that a thesis sentence makes to a reader are important ones and must be kept. It's helpful sometimes to explain the thesis as a kind of contract between reader and writer: if this contract is broken, the reader will feel frustrated and betrayed. Accordingly, the writer must be very careful in the development of the thesis.

Working on the Thesis Sentence

Chances are if you've had trouble following or deciphering the argument of a paper, there's a problem with the thesis. If a tutor's first response to a paper is that he doesn't know what the paper is about, then the thesis sentence is either absent from the paper, or it's hiding. The first thing you might wish to do is to ask the writer what his thesis is. He may point to a particular sentence that he thinks is his thesis, giving you a very good place to start.

Let's say that you've read a paper in which you've encountered this thesis:

Although heterosexuality has long been regarded as the only natural expression of sexuality, this view has been recently and strongly challenged by the gay rights movement.

What's wrong with this sentence? Many things, the most troublesome of which is that it argues nothing. Who is going to deny that the heteronormative view has been challenged by the gay rights movement? At this point, you need to ask the writer some questions. In what specific ways has the gay rights movement challenged heterosexuality? Do these ways seem reasonable to the writer? Why or why not? What argument does he intend to make about this topic? Why does he want to make it? To whom does he want to make it?

After giving the writer some time to think about and talk about these questions, you'll probably want to bring up another problem that is certain to arise out of a thesis like this one: the matter of structure. Any paper that follows a thesis like this one is likely to ramble. How can the reader figure out what all the supporting paragraphs are doing when the argument itself is so ill-defined? You'll want to show the writer that a strong thesis suggests - even helps to create - strong topic sentences. (More on this when we consider matters of structure, below).

But before we move on to other matters, let's consider the problem of this thesis from another angle: its style. We can see without difficulty that the sentence presents us with at least two stylistic problems: 1) this thesis, which should be the most powerful sentence of the paper, employs the passive voice, and 2) the introductory clause functions as a dangling modifier (who regards heterosexuality as the only natural way to express sexuality?).

Both stylistic problems point to something at work in the sentence: the writer obliterates the actors - heterosexuals and homosexuals alike - by using the dangling modifier and the passive voice. Why does he do that? Is he avoiding naming the actors in these sentences because he's not comfortable with the positions they take? Is he unable to declare himself because he feels paralyzed by the sense that he must write a paper that is politically correct? Or does he obliterate the actors with the passive voice because he himself wishes to remain passive on this topic?

These are questions to pose to the writer, though they must be posed gently. In fact, you might gently pose these questions via a discussion of style. For instance, you might also suggest that the writer rewrite the sentence in the active voice:

Although our society has long regarded heterosexuality as the only natural expression of sexuality, members of the gay rights movement have challenged this view strongly.

This active construction helps us to see clearly what's missing:

Although our society has long regarded heterosexuality as the only natural expression of sexuality, members of the gay rights movement have challenged this view strongly, arguing XYZ.

This more active construction also makes it clear that merely enumerating the points the author wants to make is not the same thing as creating an argument. The writer should now be able to see that he needs to go one step further - he needs to reveal his own position on the gay rights movement. The rest of the paper will develop this position.

In short, there are many ways to begin work on a writer's thesis sentences. Almost all of them will lead you to other matters important to the paper's success: its structure, its language, its style. Try to make any conversation you have about thesis sentences point to other problems with the writing. Not only is this strategy efficient, but it also encourages a writer to see how important a thesis is to the overall success of his essay.

Talking Your Way to a Workable Thesis

For the sake of making (we hope) a somewhat humorous illustration of the matter at hand, we offer the following scenario, which shows how tutor and tutee can talk their way to a workable thesis - and, indeed, to a good essay. So sit back, and enjoy this "break" in your training.

Imagine (though it is indeed quite a stretch) that a freshman composition teacher has the audacity to assign a paper on cats (the animals, not the play). The students may write any kind of paper they like - narration, description, compare/contrast, etc. - as long as their essays contain a thesis (that is, that they argue some point) concerning cats. A writer comes to you for help in developing her thesis. You read the assignment, and then you tell the writer that she first must choose the kind of paper she would like to do. She decides to do a narrative because she thinks she has more freedom in the narrative form. Then you ask her what she has to say about cats. "I don't like them," is her reply.

"OK," you say, "that's a start. Why don't you like them?" The writer has lots of reasons: they smell, they're aloof, they shed, they keep you up nights when they're in heat, they're very middle class, they steal food off of the table, they don't get along with dogs (the writer loves dogs), and on, and on. After brainstorming for a while, you tell the writer to choose a few points on which she'd like to focus - preferably those points that she feels strongly about or those which seem unusual. She picks three: cats smell, they steal food, and they are middle class. She offers her thesis: "I don't like cats because they are smelly, thieving, and middle class."

"O.K.," you say, "It's not a very sophisticated thesis but we can use it for now. After all, it defines your stance, it controls your subject, it organizes your argument, and it predicts your strategy - all the things that a thesis ought to do. Now let's consider how to develop the thesis, point by point."

You begin to ask questions about cats and their smell. "What do they smell like?" you say. The writer thinks awhile, and then says, "They smell like dirty gym shorts, like old hamburgers, like my eighth-grade math teacher's breath." The writer laughs, particularly fond of the final simile. Then she adds, "My boyfriend has a cat. A Tom. When he moved into his first apartment, that cat sprayed all over the place, you know, marking his territory. The place stunk so bad that I couldn't even go there for a week. Can you imagine? Your boyfriend gets his first apartment, and you can't even go in the place for a week?"

The writer has sparked your imagination; you think that she can spark her teacher's imagination as well. "Why don't you do your narrative about your boyfriend's cat? You could tell the story - or you could make up a story - about going over there for dinner, hoping for a romantic evening, and being put off by the cat." The writer likes this idea and goes off to write her draft. She returns with the following story about her boyfriend and his cat.

She was hoping for a romantic dinner; he was making her favorite meal. She could smell the T-bone and the apple pie before she even got to his door. But when she opened the door, her appetite was obliterated: the smell of cat spray smelled worse than her eighth-grade math teacher's breath. Of course, because she remained hopeful for a romantic evening, she put on her best face, tried not to grimace, and gave her boyfriend the flowers she'd picked up on the way. They chat; everything is going fine; he goes to the kitchen to check on dinner; she hears his shriek. The cat has stolen all of the food! Upon searching, they find the cat under the sofa, not only with their dinner, but with the writer's wallet, her favorite picture of her mom torn in half, her new leather jacket now full of cat hairs. This cat not only stinks, he's a thief as well. Still, the evening need not be a total waste. They order pizza, have some wine. She and her man talk; their moods improve, and she decides that it might be a nice time to kiss. She pulls the old yawn trick to get her arm around him, and just as she's ready to kiss him the cat jumps into his lap. "Oh, Pookie, Pookie, Pookie," her boyfriend says, giving himself over to the purring cat. "Damn lap cat," the writer says to herself, and leaves it at that. She has written a paper illustrating that cats are smelly, thieving, and middle class. She has fulfilled her thesis.

Now, you like this paper. It's got a great voice, and it's got humor. You feel, however, that the writer should refine the thesis. It has served the writer well in helping her to organize, control, predict, and define her essay; however, she needs now to consider how to choose words and a tone which will hook the reader and reel him in. You explain to the writer that her thesis can be humorous, that she can feel free to be extreme, because a funny, exaggerated thesis would suit this funny, exaggerated paper.

After some doodling and some dialogue, the writer comes up with the following thesis: "All cats should be exterminated because they are the stinking, kleptomaniacal darlings of the bourgeoisie." You laugh; you like it. Moreover, the thesis has given the writer an ending for her essay: she exterminates the cat in her boyfriend's microwave, convinces him to get a goldfish instead, and the two of them live happily ever after. The writer is happy. The tutor is happy. The paper works.

While you will likely not encounter a "cat" assignment at Dartmouth, this sort of experience with writing a thesis is a common one. Even when papers are more sophisticated than this one - even when the subject is Hitler's rise to power, or Freud's treatment of taboo - writers will often write a working thesis, one that guides them through the writing process. Then they will return to the thesis, sometimes several times before their paper is finished, revising it to better fit their paper's increasingly refined argument and tone.

Polishing the Thesis Sentence

Look at the sentence's structure. Is the main idea of the paper placed appropriately in the main clause? If there are parallel points made in the paper, does the thesis sentence signal this to the reader via some parallel structure? If the paper makes an interesting but necessary aside, is that aside predicted - perhaps in a parenthetical element? Remember: the structure of the thesis sentence also signals much to the reader about the structure of the argument. Be sure that the thesis reflects, reliably, what the paper itself is going to say.

As to the style of the sentence: hold the thesis sentence to the highest stylistic standards. Help a writer to make sure that it is as clear and concise as it can be, and that its language and phrasing reflect confidence, eloquence, and grace.

- Skip to Content

- Skip to Main Navigation

- Skip to Search

Indiana University Bloomington Indiana University Bloomington IU Bloomington

- Mission, Vision, and Inclusive Language Statement

- Locations & Hours

- Undergraduate Employment

- Graduate Employment

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Newsletter Archive

- Support WTS

- Schedule an Appointment

- Online Tutoring

- Before your Appointment

- WTS Policies

- Group Tutoring

- Students Referred by Instructors

- Paid External Editing Services

- Writing Guides

- Scholarly Write-in

- Dissertation Writing Groups

- Journal Article Writing Groups

- Early Career Graduate Student Writing Workshop

- Workshops for Graduate Students

- Teaching Resources

- Syllabus Information

- Course-specific Tutoring

- Nominate a Peer Tutor

- Tutoring Feedback

- Schedule Appointment

- Campus Writing Program

Writing Tutorial Services

How to write a thesis statement, what is a thesis statement.

Almost all of us—even if we don’t do it consciously—look early in an essay for a one- or two-sentence condensation of the argument or analysis that is to follow. We refer to that condensation as a thesis statement.

Why Should Your Essay Contain a Thesis Statement?

- to test your ideas by distilling them into a sentence or two

- to better organize and develop your argument

- to provide your reader with a “guide” to your argument

In general, your thesis statement will accomplish these goals if you think of the thesis as the answer to the question your paper explores.

How Can You Write a Good Thesis Statement?

Here are some helpful hints to get you started. You can either scroll down or select a link to a specific topic.

How to Generate a Thesis Statement if the Topic is Assigned How to Generate a Thesis Statement if the Topic is not Assigned How to Tell a Strong Thesis Statement from a Weak One

How to Generate a Thesis Statement if the Topic is Assigned

Almost all assignments, no matter how complicated, can be reduced to a single question. Your first step, then, is to distill the assignment into a specific question. For example, if your assignment is, “Write a report to the local school board explaining the potential benefits of using computers in a fourth-grade class,” turn the request into a question like, “What are the potential benefits of using computers in a fourth-grade class?” After you’ve chosen the question your essay will answer, compose one or two complete sentences answering that question.

Q: “What are the potential benefits of using computers in a fourth-grade class?” A: “The potential benefits of using computers in a fourth-grade class are . . .”

A: “Using computers in a fourth-grade class promises to improve . . .”

The answer to the question is the thesis statement for the essay.

[ Back to top ]

How to Generate a Thesis Statement if the Topic is not Assigned

Even if your assignment doesn’t ask a specific question, your thesis statement still needs to answer a question about the issue you’d like to explore. In this situation, your job is to figure out what question you’d like to write about.

A good thesis statement will usually include the following four attributes:

- take on a subject upon which reasonable people could disagree

- deal with a subject that can be adequately treated given the nature of the assignment

- express one main idea

- assert your conclusions about a subject

Let’s see how to generate a thesis statement for a social policy paper.

Brainstorm the topic . Let’s say that your class focuses upon the problems posed by changes in the dietary habits of Americans. You find that you are interested in the amount of sugar Americans consume.

You start out with a thesis statement like this:

Sugar consumption.

This fragment isn’t a thesis statement. Instead, it simply indicates a general subject. Furthermore, your reader doesn’t know what you want to say about sugar consumption.

Narrow the topic . Your readings about the topic, however, have led you to the conclusion that elementary school children are consuming far more sugar than is healthy.

You change your thesis to look like this:

Reducing sugar consumption by elementary school children.

This fragment not only announces your subject, but it focuses on one segment of the population: elementary school children. Furthermore, it raises a subject upon which reasonable people could disagree, because while most people might agree that children consume more sugar than they used to, not everyone would agree on what should be done or who should do it. You should note that this fragment is not a thesis statement because your reader doesn’t know your conclusions on the topic.

Take a position on the topic. After reflecting on the topic a little while longer, you decide that what you really want to say about this topic is that something should be done to reduce the amount of sugar these children consume.

You revise your thesis statement to look like this:

More attention should be paid to the food and beverage choices available to elementary school children.

This statement asserts your position, but the terms more attention and food and beverage choices are vague.

Use specific language . You decide to explain what you mean about food and beverage choices , so you write:

Experts estimate that half of elementary school children consume nine times the recommended daily allowance of sugar.

This statement is specific, but it isn’t a thesis. It merely reports a statistic instead of making an assertion.

Make an assertion based on clearly stated support. You finally revise your thesis statement one more time to look like this:

Because half of all American elementary school children consume nine times the recommended daily allowance of sugar, schools should be required to replace the beverages in soda machines with healthy alternatives.

Notice how the thesis answers the question, “What should be done to reduce sugar consumption by children, and who should do it?” When you started thinking about the paper, you may not have had a specific question in mind, but as you became more involved in the topic, your ideas became more specific. Your thesis changed to reflect your new insights.

How to Tell a Strong Thesis Statement from a Weak One

1. a strong thesis statement takes some sort of stand..

Remember that your thesis needs to show your conclusions about a subject. For example, if you are writing a paper for a class on fitness, you might be asked to choose a popular weight-loss product to evaluate. Here are two thesis statements:

There are some negative and positive aspects to the Banana Herb Tea Supplement.

This is a weak thesis statement. First, it fails to take a stand. Second, the phrase negative and positive aspects is vague.

Because Banana Herb Tea Supplement promotes rapid weight loss that results in the loss of muscle and lean body mass, it poses a potential danger to customers.