The 95 Theses: A reader’s guide

![95 Theses Luther's 95 Theses. c. 1557 [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://blogs.lcms.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/95_Thesen_Erste_Seite_banner-1.jpg)

by Kevin Armbrust

October 2017 marks the 500th anniversary of the Lutheran Reformation. Yet it is not the anniversary of any great statement Luther made as a reformer or in front of any court. There was no fiery and resounding speech given or dramatic showdown with the pope. On October 31, 1517, Martin Luther posted the “Disputation on the Power and Efficacy of Indulgences” to the church door in a small city called Wittenberg, Germany. This rather mundane academic document contained 95 theses for debate. Luther was a professor of theology at the University of Wittenberg, and he was permitted to call for public theological debate to discuss ideas and interpretations as he desired.

Yet this debate was not merely academic for Luther. According to a letter he wrote to the Archbishop of Mainz explaining the posting of the 95 Theses, Luther also desired to debate the concerns in the Theses for the sake of conscience.

Luther’s short preface explains:

“Out of love and zeal for truth and the desire to bring it to light, the following theses will be publicly discussed at Wittenberg under the chairmanship of the reverend father Martin Luther, Master of Arts and Sacred Theology and regularly appointed Lecturer on these subjects at that place. He requests that those who cannot be present to debate orally with us will do so by letter.”

The original text of the 95 Theses was written in Latin, since that was the academic language of Luther’s day. Luther’s theses were quickly translated into German, published in pamphlet form and spread throughout Germany.

Though English translations are readily available , many have found the 95 Theses difficult to read and comprehend. The short primer that follows may assist to highlight some of the theses and concepts Luther wished to explore.

Repentance and forgiveness dominate the content of the Theses. Since the question for Luther was the effectiveness of indulgences, he drove the discussion to the consideration of repentance and forgiveness in Christ. The first three theses address this:

1. When our Lord and Master Jesus Christ said, “Repent” [MATT. 4:17], he willed the entire life of believers to be one of repentance.

2. This word cannot be understood as referring to the sacrament of penance, that is, confession and satisfaction, as administered by the clergy.

3. Yet it does not mean solely inner repentance; such inner repentance is worthless unless it produces various outward mortifications of the flesh.

The pope and the Church cannot cause true repentance in a Christian and cannot forgive the sins of one who is guilty before Christ. The pope can only forgive that which Christ forgives. True repentance and eternal forgiveness come from Christ alone.

Luther identifies indulgences as a doctrine invented by man, since there is no scriptural promise or command for indulgences. Although Luther stops short of entirely condemning indulgences in the Theses, he nonetheless argues that the sale of indulgences and the trust in indulgences for salvation condemns both those who teach such notions and those who trust in them.

27. They preach only human doctrines who say that as soon as the money clinks into the money chest, the soul flies out of purgatory.

28. Those who believe that they can be certain of their salvation because they have indulgence letters will be eternally damned, together with their teachers.

God’s grace comes not through indulgences but through Christ. All Christians receive the blessings of God apart from indulgence letters.

36. Any truly repentant Christian has a right to full remission of penalty and guilt, even without indulgence letters.

37. Any true Christian, whether living or dead, participates in all the blessings of Christ and the church; and this is granted him by God, even without indulgence letters.

If Christians are going to spend money on something other than supporting their families, they should take care of the poor instead of buying indulgences.

43. Christians are to be taught that he who gives to the poor or lends to the needy does a better deed than he who buys indulgences.

The second half of the 95 Theses concentrates on the preaching of the true Word of the Gospel. Luther states that the teaching of indulgences should be lessened so that there might be more time for the proclamation of the true Gospel.

62. The true treasure of the church is the most holy gospel of the glory and grace of God.

63. But this treasure is naturally most odious, for it makes the first to be last [MATT. 20:16].

The Gospel of Christ is the true power for salvation (ROM. 1:16), not indulgences or even the power of the papal office.

76. We say on the contrary that papal indulgences cannot remove the very least of venial sins as far as guilt is concerned.

77. To say that even St. Peter, if he were now pope, could not grant greater graces is blasphemy against St. Peter and the pope.

78. We say on the contrary that even the present pope, or any pope whatsoever, has greater graces at his disposal, that is, the gospel, spiritual powers, gifts of healing, etc., as it is written in I Cor. 12[:28].

Preaching a false hope is really no hope at all. As a matter of fact, a false hope destroys and kills because it moves people away from Christ, where true salvation is found. The Gospel is found in Christ alone, which includes a cross and tribulations both large and small.

92. Away then with all those prophets who say to the people of Christ, “Peace, peace,” and there is no peace! [JER. 6:14].

93. Blessed be all those prophets who say to the people of Christ, “Cross, cross,” and there is no cross!

94. Christians should be exhorted to be diligent in following Christ, their head, through penalties, death, and hell;

95. And thus be confident of entering into heaven through many tribulations rather than through the false security of peace [ACTS 14:22].

Throughout the 95 Theses, Luther seeks to balance the role of the Church with the truth of the Gospel. Even as he desired to support the pope and his role in the Church, the false teaching of indulgences and the pope’s unwillingness to freely forgive the sins of all repentant Christians compelled him to speak up against these abuses.

Luther’s pastoral desire for all to trust in Christ alone for salvation drove him to post the 95 Theses. This same faith and hope sparked the Reformation that followed.

Dr. Kevin Armbrust is manager of editorial services for LCMS Communications.

Related Posts

How did Luther become a Lutheran?

Laughing with Luther

Luther alone?

About the author.

Kevin Armbrust

11 thoughts on “the 95 theses: a reader’s guide”.

Thx. This article does clear up a number of difficulties in interpreting the drift & theme of the 95 thesis. The fact that he supports the pope’s office at this juncture is new to me.

Very useful as I prepare a Sunday School lesson. Thanks

As important as the 95 Theses were for the beginning of the Reformation, and since they are not specifically part of the Lutheran Confessions, are there any of the Theses that we Lutherans consider unimportant or would rather avoid, theologically speaking?

I wish Luther was here, maybe things would change in our country and bring more folks to Jesus .

“When our Lord and master Jesus Christ says, ‘Repent,’ he wills that the entire life of the Christian be one of repentance.”

This seemingly joyless statement is often quoted, less often explained, and easily misunderstood. Is Jesus calling for the main theme of Christian life to be, “I’m ashamed of my sin”?

The full sentence from Matthew 4:17 is, “Repent, for the kingdom of heaven is at hand,” spoken when Jesus was beginning His ministry. This layman might paraphrase those words as, “Change your mindset, for divine authority is coming among you.” Indeed, when a very important person is coming to visit, we depart from business as usual, adjust our priorities, focus on careful preparation, and behave as befits the status of the visitor.

The word “repent” is recorded in Greek as “metanoeite”, which I understand to be not about remorse — not primarily about feelings at all — but about changing one’s mind or purpose.

The Christian life has a variety of themes, of which repentance is one. But repentance is not an end in itself. It is pivoting and changing course to pursue a direction that better fulfills God’s purposes as He gives the grace. For Jesus also willed “that you bear much fruit” (John 15:8) and “that your joy may be full” (John 15:11).

Could you explain number 93? I need this one explained. Jackie

Agreed. 93 is confusing.

In contrast to the false security of indulgences referenced in 92, number 93 references the preaching of true repentance. With true contrition and repentance over our sins, we Christians humble ourselves to the truth that we have earned our place on the cross as punishment and condemnation. But then we find the eternal surprise and wellspring of joy that our cross has been taken away from us and made Christ’s own. In exchange He gives us forgiveness, life and salvation!

Thank you, James Athey.

I myself did not fully understand this thesis yesterday, when I searched the Internet for an explanation of it. I found that I was not the only person who was confused by it. I also found that Luther explained it in a letter that he wrote to an Augustinian prior in 1516. Here is his explanation:

You are seeking and craving for peace, but in the wrong order. For you are seeking it as the world giveth, not as Christ giveth. Know you not that God is “wonderful among His saints,” for this reason, that He establishes His peace in the midst of no peace, that is, of all temptations and afflictions. It is said “Thou shalt dwell in the midst of thine enemies.” The man who possesses peace is not the man whom no one disturbs—that is the peace of the world; he is the man whom all men and all things disturb, but who bears all patiently, and with joy. You are saying with Israel, “Peace, peace,” and there is no peace. Learn to say rather with Christ: “The Cross, the Cross,” and there is no Cross. For the Cross at once ceases to be the Cross as soon as you have joyfully exclaimed, in the language of the hymn,

Blessed Cross, above all other, One and only noble tree.

It is posted here: http://www.ccel.org/ccel/luther/first_prin.iii.i.html

Magnificent!

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

The Protestant Reformation, explained

Five hundred years ago, Martin Luther changed Christianity — and the world.

by Tara Isabella Burton

This week, people across the world are celebrating Halloween. But Tuesday, many people of faith marked another, far less spooky, celebration. October 31 was the 500-year anniversary of the day Martin Luther allegedly nailed his 95 theses — objections to various practices of the Catholic Church — to the door of a German church. This event is widely considered the beginning of the Protestant Reformation.

The event was celebrated across Germany , including in Luther’s native Wittenberg (T-shirts for sale there proudly proclaim, “Protestant since 1517!”), as well as by Protestants of all denominations worldwide. As the inciting incident for the entire Reformation, Luther’s actions came to define the subsequent five centuries of Christian history in Western Europe and, later, America: a story of constant intra-Christian challenge, debate, and conflict that has transformed Christianity into the diffuse, fragmented, and diverse entity it is today.

This week, Twitter has been full of users discussing Reformation Day. Some have used the opportunity to post jokes or funny memes about their chosen Christian denomination. Others are debating Luther’s legacy, including discussing the degree to which he either created modern Christianity as we know it or heralded centuries of division within Christian communities.

While Reformation Day is celebrated annually among some Protestants, especially in Germany, the nature of this anniversary has brought debate over Luther and the Protestant Reformation more generally into the public sphere.

So what exactly happened in 1517, and why does it matter?

What started as an objection to particular corruptions morphed into a global revolution

While the Catholic Church was not the only church on the European religious landscape (the Eastern Orthodox Churches still dominated in Eastern Europe and parts of Asia), by the 16th century, it was certainly the most dominant. The church had a great deal of political as well as spiritual power; it had close alliances, for example, with many royal houses, as well as the emperor of the Holy Roman Empire, which at that time encompassed much of Central Europe, including present-day Germany.

The church’s great power brought with it a fair degree of corruption. Among the most notable and controversial practices of that time was the selling of “indulgences.” For Catholics of that time, sin could be divided into two broad categories. “Mortal sin” was enough to send you to hell after death, while “venal sin” got you some years of purifying punishment in purgatory, an interim state between life on earth and the heavenly hereafter.

By the 16th century, the idea that you could purchase an indulgence to reduce your purgatorial debt had become increasingly widespread. Religious leaders who wanted to fund projects would send out “professional pardoners,” or quaestores, to collect funds from the general public. Often, the sale of indulgences exceeded the official parameters of church doctrine; unscrupulous quaestores might promise eternal salvation (rather than just a remission of time in purgatory) in exchange for funds, or threaten damnation to those who refused. Indulgences could be sold on behalf of departed friends or loved ones, and many indulgence salesmen used that pressure to great effect.

Enter Martin Luther. A Catholic monk in Wittenberg, Luther found himself disillusioned by the practices of the church he loved. For Luther, indulgences — and the church’s approach to sin and penance more generally — seemed to go against what he saw as the most important part of his Christian faith. If God really did send his only son, Jesus, to die on the cross for the sins of mankind, then why were indulgences even necessary? If the salvation of mankind had come through Jesus’s sacrifice, then surely faith in Jesus alone should be enough for salvation.

In autumn 1517 (whether the actual date of October 31 is accurate is debatable), Luther nailed his 95 theses — most of the 95 points in the document, which was framed in the then-common style of academic debate, objections to the practice of indulgences — to a Wittenberg church door.

His intent was to spark a debate within his church over a reformation of Catholicism. Instead, Luther and those who followed him found themselves at the forefront of a new religious movement known as Lutheranism. By 1520, Luther had been excommunicated by the Catholic Church. Soon after, he found himself at the Diet (council) of the city of Worms, on trial for heresy under the authority of the (very Catholic) Holy Roman Emperor Charles V. At that council, the emperor declared Luther to be an outlaw and demanded his arrest.

Political, economic, and technological factors contributed to the spread of Luther’s ideas

So why wasn’t Luther arrested and executed, as plenty of other would-be reformers and “heretics” had been? The answer has as much to do with politics as with religion. In the region now known as Germany, the holy Roman emperor had authority over many regional princes, not all of whom were too happy about submitting to their emperor’s authority.

One such prince, Frederick III, Elector of Saxony, “kidnapped” Luther after his trial to keep him safe from his would-be arrestors. In the years following the trial, and the spread of Luther’s dissent as the basis for a Lutheranism, Protestantism often became a means by which individual princes would signal their opposition to imperial power. And when a prince converted, his entire principality was seen to have converted too. This led, for example, to the catastrophic Thirty Years’ War from 1618 to 1648, in which conflict between pro-Catholic and pro-Lutheran German princes morphed into a pan-European war that killed up to 20 percent of Europe’s population.

As it happens, the term “Protestant” began as a political rather than theological category. It originally referred to a number of German princes who formally protested an imperial ban on Martin Luther, before becoming a more general term for reformers who founded movements outside the Catholic Church.

Meanwhile, Luther was able to spread his ideas more quickly than ever before due to one vital new piece of technology: the printing press. For the first time in human history, vast amounts of information could be transmitted and shared easily with a great number of people. Luther’s anti-clerical pamphlets and essays — which were written in German, the language of the people, rather than the more obscure and “formal” academic language of Latin — could be swiftly and easily disseminated to convince others of his cause. (The relationship between Luther and the printing press was actually a symbiotic one : The more popular Luther became, the more print shops spread up across Europe to meet demand.)

Luther’s newfound popularity and “celebrity” status, in turn, made him a much more difficult force for his Catholic opponents to contend with. While earlier would-be reformers, such as John Hus, had been burned at the stake for heresy, getting rid of someone as widely known as Luther was far more politically risky.

Luther’s success, and the success of those who followed him, is a vital reminder of the ways politics, propaganda, and religion intersect. Something that began as a relatively narrow and academic debate over the church selling indulgences significantly changed Western culture. Luther opened the floodgates for other reformers.

Although Luther can be said to have started the Reformation, he was one of many reformers whose legacy lives on in different Protestant traditions. Switzerland saw the rise of John Calvin (whose own Protestant denomination, Calvinism, bears his name). John Knox founded the Presbyterian Church of Scotland. Each denomination of Protestantism had its own specific theology and approach. But not all Protestant reformations were entirely idealistic in nature: King Henry VIII famously established the Church of England, still the state church in that country today, in order to annul his marriage to Catherine of Aragon and marry Anne Boleyn.

Nearly all Protestant groups, however, shared Luther’s original objections to the Catholic Church — theological ideals that still define the Protestant umbrella today.

The most important of these is the idea that salvation happens through faith alone. In other words, nothing — not indulgences, not confession or penance, not even good works — can alter the course of a person’s salvation. For Protestants, salvation happens through divine grace received through faith in Jesus Christ. The second of these is the idea that biblical Scripture, and a person’s individual relationship with the Bible, is the most important source of information about God and Christian life. (This is in stark contrast with the Catholic Church, in which a wider body of church teaching and church authority play a major role.)

While it would be too simplistic to say that Protestants as a whole favor individualism and autonomy over established tradition, it’s fair to say that most Protestant traditions place a greater premium on individuals’ personal religious experiences, on the act of “being saved” through prayer, and on individual readings of Scripture, than do Catholics or members of orthodox churches.

Other differences between Catholic and Protestant theology and practice involve the clergy and church. Protestants by and large see the “sacraments,” such as communion, as less important than their Catholic counterparts (the intensity of this varies by tradition, although only Catholics see the communion wafer as the literal body of Christ). Protestant priests, likewise, are not bound by priestly celibacy, and can marry.

That said, for many Christians today, differences are cultural, not theological. Earlier this fall, a study carried out by the Pew Research Center found that average Protestants more often than not assert traditionally Catholic teachings about, among other things, the nature of salvation or the role of church teaching.

Protestantism today still bears the stamp of Luther

Today, about 900 million people — 40 percent of Christians — identify as Protestant around the world. Of these, 72 million people — just 8 percent — are Lutherans. But Lutheranism has still come to define much of the Protestant ethos.

Over the centuries, more forms of Protestantism have taken shape. Several of them have had cataclysmic effects on world history. Puritanism, another reform movement within the Church of England, inspired its members to seek a new life in the New World and helped shape America as we know it today. Many of these movements classified themselves as “revivalist” movements, each one in turn trying to reawaken a church that critics saw as having become staid and complacent (just as Luther saw the Catholic Church).

Of these reform and revivalist movements, perhaps none is so visible today in America as the loose umbrella known as evangelical Christianity. Many of the historic Protestant churches — Lutheranism, Calvinism, Presbyterianism, the Church of England — are now classified as mainline Protestant churches, which tend to be more socially and politically liberal. Evangelical Christianity, though, arose out of similar revivalist tendencies within those churches, in various waves dating back to the 18th century.

Even more decentralized than their mainline counterparts, evangelical Christian groups tend to stress scriptural authority (including scriptural inerrancy) and the centrality of being “saved” to an even greater extent than, say, modern Lutheranism. Because of the fragmented and decentralized way many of these churches operate, anybody can conceivably set up a church or church community in any building. This, in turn, gives rise to the trend of “storefront churches,” something particularly popular in Pentecostal communities, and “house churches,” in which members meet for Bible study at one another’s homes.

The history of Christianity worldwide has, largely, followed the Luther cycle. As each church or church community becomes set in its ways, a group of idealistic reformers seeks to revitalize its spiritual life. They found new movements, only for reformers to splinter off from them in turn.

In America, where mainline Protestantism has been in decline for decades, various forms of evangelical Protestantism seemed to flourish for many years. Now evangelicals — particularly white evangelicals — are finding themselves in decline for a variety of reasons, including demographic change and increasingly socially liberal attitudes on the part of younger Christians. Meanwhile, social media — the printing press of our own age — is changing the way some Christians worship: Some Christians are more likely to worship and study the Bible online or attend virtual discussion groups, while in other churches, attendees are encouraged to “live-tweet” sermons to heighten engagement.

What happens next is anyone’s guess.

But if the history of Lutheranism is anything to go by, we may be due for another wave of reformation before too long.

Most Popular

Trump wants the supreme court to toss out his conviction. will they, 10 big things we think will happen in the next 10 years, the secret to modern friendship, according to real friends, take a mental break with the newest vox crossword, india’s election shows the world’s largest democracy is still a democracy, today, explained.

Understand the world with a daily explainer plus the most compelling stories of the day.

More in Religion

What the Methodist split tells us about America

UFOs, God, and the edge of understanding

The Vatican’s new statement on trans rights undercuts its attempts at inclusion

Trump may sound moderate on abortion. The groups setting his agenda definitely aren’t.

The chaplain who doesn’t believe in God

9 questions about Ramadan you were too embarrassed to ask

Is TikTok breaking young voters’ brains?

Can artists use their own deepfakes for good?

What happens if Gaza ceasefire talks fail

The US tests Putin’s nuclear threats in Ukraine

It’s not Islamophobia, it’s anti-Palestinian racism

Biden’s sweeping new asylum restrictions, explained

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

This Day In History : October 31

Changing the day will navigate the page to that given day in history. You can navigate days by using left and right arrows

Martin Luther posts 95 theses

On October 31, 1517, legend has it that the priest and scholar Martin Luther approaches the door of the Castle Church in Wittenberg, Germany, and nails a piece of paper to it containing the 95 revolutionary opinions that would begin the Protestant Reformation .

In his theses, Luther condemned the excesses and corruption of the Roman Catholic Church, especially the papal practice of asking payment—called “indulgences”—for the forgiveness of sins. At the time, a Dominican priest named Johann Tetzel, commissioned by the Archbishop of Mainz and Pope Leo X, was in the midst of a major fundraising campaign in Germany to finance the renovation of St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome. Though Prince Frederick III the Wise had banned the sale of indulgences in Wittenberg, many church members traveled to purchase them. When they returned, they showed the pardons they had bought to Luther, claiming they no longer had to repent for their sins.

Luther’s frustration with this practice led him to write the 95 Theses, which were quickly snapped up, translated from Latin into German and distributed widely. A copy made its way to Rome, and efforts began to convince Luther to change his tune. He refused to keep silent, however, and in 1521 Pope Leo X formally excommunicated Luther from the Catholic Church. That same year, Luther again refused to recant his writings before the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V of Germany, who issued the famous Edict of Worms declaring Luther an outlaw and a heretic and giving permission for anyone to kill him without consequence. Protected by Prince Frederick, Luther began working on a German translation of the Bible, a task that took 10 years to complete.

The term “Protestant” first appeared in 1529, when Charles V revoked a provision that allowed the ruler of each German state to choose whether they would enforce the Edict of Worms. A number of princes and other supporters of Luther issued a protest, declaring that their allegiance to God trumped their allegiance to the emperor. They became known to their opponents as Protestants; gradually this name came to apply to all who believed the Church should be reformed, even those outside Germany. By the time Luther died, of natural causes, in 1546, his revolutionary beliefs had formed the basis for the Protestant Reformation, which would over the next three centuries revolutionize Western civilization.

Also on This Day in History October | 31

Freak explosion at Indiana State Fairgrounds Coliseum kills nearly 100

Violet palmer becomes first woman to officiate an nba game, this day in history video: what happened on october 31, stalin’s body removed from lenin’s tomb, celebrated magician harry houdini dies, earl lloyd becomes first black player in the nba.

Wake Up to This Day in History

Sign up now to learn about This Day in History straight from your inbox. Get all of today's events in just one email featuring a range of topics.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

The U.S. Congress admits Nevada as the 36th state

Ed sullivan witnesses beatlemania firsthand, paving the way for the british invasion, actor river phoenix dies, indian prime minister indira gandhi is assassinated, king george iii speaks for first time since american independence declared.

- Featured Essay The Love of God An essay by Sam Storms Read Now

- Faithfulness of God

- Saving Grace

- Adoption by God

Most Popular

- Gender Identity

- Trusting God

- The Holiness of God

- See All Essays

- Conference Media

- Featured Essay Resurrection of Jesus An essay by Benjamin Shaw Read Now

- Death of Christ

- Resurrection of Jesus

- Church and State

- Sovereignty of God

- Faith and Works

- The Carson Center

- The Keller Center

- New City Catechism

- Publications

- Read the Bible

U.S. Edition

- Arts & Culture

- Bible & Theology

- Christian Living

- Current Events

- Faith & Work

- As In Heaven

- Gospelbound

- Post-Christianity?

- TGC Podcast

- You're Not Crazy

- Churches Planting Churches

- Help Me Teach The Bible

- Word Of The Week

- Upcoming Events

- Past Conference Media

- Foundation Documents

- Church Directory

- Global Resourcing

- Donate to TGC

To All The World

The world is a confusing place right now. We believe that faithful proclamation of the gospel is what our hostile and disoriented world needs. Do you believe that too? Help TGC bring biblical wisdom to the confusing issues across the world by making a gift to our international work.

Luther’s Ninety-five Theses: What You May Not Know and Why They Matter Today

More By Justin Holcomb

For more accessible overviews of key moments in church history, purchase Justin Holcomb’s new book, Know the Creeds and Councils (Zondervan, 2014) [ interview ]. Additionally, Holcomb has made available to TGC readers an exclusive bonus chapter, which can be accessed here . This article is a shortened version of the chapter.

If people know only one thing about the Protestant Reformation, it is the famous event on October 31, 1517, when the Ninety-five Theses of Martin Luther (1483–1586) were nailed on the door of the Castle Church of Wittenberg in protest against the Roman Catholic Church. Within a few years of this event, the church had splintered into not just the “church’s camp” or “Luther’s camp” but also the camps of churches led by theologians of all different stripes.

Luther is known mostly for his teachings about Scripture and justification. Regarding Scripture, he argued the Bible alone ( sola scriptura ) is our ultimate authority for faith and practice. Regarding justification, he taught we are saved solely through faith in Jesus Christ because of God’s grace and Christ’s merit. We are neither saved by our merits nor declared righteous by our good works. Additionally, we need to fully trust in God to save us from our sins, rather than relying partly on our own self-improvement.

Forgiveness with a Price Tag

These teachings were radical departures from the Catholic orthodoxy of Luther’s day. But you might be surprised to learn that the Ninety-five Theses, even though this document that sparked the Reformation, was not about these issues. Instead, Luther objected to the fact that the Roman Catholic Church was offering to sell certificates of forgiveness, and that by doing so it was substituting a false hope (that forgiveness can be earned or purchased) for the true hope of the gospel (that we receive forgiveness solely via the riches of God’s grace).

The Roman Catholic Church claimed it had been placed in charge of a “treasury of merits” of all of the good deeds that saints had done (not to mention the deeds of Christ, who made the treasury infinitely deep). For those trapped by their own sinfulness, the church could write a certificate transferring to the sinner some of the merits of the saints. The catch? These “indulgences” had a price tag.

This much needs to be understood to make sense of Luther’s Ninety-five Theses: the selling of indulgences for full remission of sins intersected perfectly with the long, intense struggle Luther himself had experienced over the issues of salvation and assurance. At this point of collision between one man’s gospel hope and the church’s denial of that hope the Ninety-five Theses can be properly understood.

Theses Themselves

Luther’s Ninety-five Theses focuses on three main issues: selling forgiveness (via indulgences) to build a cathedral, the pope’s claimed power to distribute forgiveness, and the damage indulgences caused to grieving sinners. That his concern was pastoral (rather than trying to push a private agenda) is apparent from the document. He didn’t believe (at this point) that indulgences were altogether a bad idea; he just believed they were misleading Christians regarding their spiritual state:

41. Papal indulgences must be preached with caution, lest people erroneously think that they are preferable to other good works of love.

As well as their duty to others:

43. Christians are to be taught that he who gives to the poor or lends to the needy does a better deed than he who buys indulgences.

44. Because love grows by works of love, man thereby becomes better. Man does not, however, become better by means of indulgences but is merely freed from penalties. [Notice that Luther is not yet wholly against the theology of indulgences.]

And even financial well-being:

46. Christians are to be taught that, unless they have more than they need, they must reserve enough for their family needs and by no means squander it on indulgences.

Luther’s attitude toward the pope is also surprisingly ambivalent. In later years he called the pope “the Antichrist” and burned his writings, but here his tone is merely cautionary, hoping the pope will come to his senses. For instance, in this passage he appears to be defending the pope against detractors, albeit in a backhanded way:

51. Christians are to be taught that the pope would and should wish to give of his own money, even though he had to sell the basilica of St. Peter, to many of those from whom certain hawkers of indulgences cajole money.

Obviously, since Leo X had begun the indulgences campaign in order to build the basilica, he did not “wish to give of his own money” to victims. However, Luther phrased his criticism to suggest that the pope might be ignorant of the abuses and at any rate should be given the benefit of the doubt. It provided Leo a graceful exit from the indulgences campaign if he wished to take it.

So what made this document so controversial? Luther’s Ninety-five Theses hit a nerve in the depths of the authority structure of the medieval church. Luther was calling the pope and those in power to repent—on no authority but the convictions he’d gained from Scripture—and urged the leaders of the indulgences movement to direct their gaze to Christ, the only one able to pay the penalty due for sin.

Of all the portions of the document, Luther’s closing is perhaps the most memorable for its exhortation to look to Christ rather than to the church’s power:

92. Away, then, with those prophets who say to Christ’s people, “Peace, peace,” where in there is no peace.

93. Hail, hail to all those prophets who say to Christ’s people, “The cross, the cross,” where there is no cross.

94. Christians should be exhorted to be zealous to follow Christ, their Head, through penalties, deaths, and hells.

95. And let them thus be more confident of entering heaven through many tribulations rather than through a false assurance of peace.

In the years following his initial posting of the theses, Luther became emboldened in his resolve and strengthened his arguments with Scripture. At the same time, the church became more and more uncomfortable with the radical Luther and, in the following decades, the spark that he made grew into a flame of reformation that spread across Europe. Luther was ordered by the church to recant in 1520 and was eventually exiled in 1521.

Ongoing Relevance

Although the Ninety-five Theses doesn’t explicitly lay out a Protestant theology or agenda, it contains the seeds of the most important beliefs of the movement, especially the priority of grasping and applying the gospel. Luther developed his critique of the Roman Catholic Church out of his struggle with doubt and guilt as well as his pastoral concern for his parishioners. He longed for the hope and security that only the good news can bring, and he was frustrated with the structures that were using Christ to take advantage of people and prevent them from saving union with God. Further, Luther’s focus on the teaching of Scripture is significant, since it provided the foundation on which the great doctrines of the Reformation found their origin.

Indeed, Luther developed a robust notion of justification by faith and rejected the notion of purgatory as unbiblical; he argued that indulgences and even hierarchical penance cannot lead to salvation; and, perhaps most notably, he rebelled against the authority of the pope. All of these critiques were driven by Luther’s commitment, above all else, to Christ and the Scriptures that testify about him. The outspoken courage Luther demonstrated in writing and publishing the Ninety-five Theses also spread to other influential leaders of the young Protestant Reformation.

Today, the Ninety-five Theses may stand as the most well-known document from the Reformation era. Luther’s courage and his willingness to confront what he deemed to be clear error is just as important today as it was then. One of the greatest ways in which Luther’s theses affect us today—in addition to the wonderful inheritance of the five Reformation solas (Scripture alone, grace alone, faith alone, Christ alone, glory to God alone)—is that it calls us to thoroughly examine the inherited practices of the church against the standard set forth in the Scriptures. Luther saw an abuse, was not afraid to address it, and was exiled as a result of his faithfulness to the Bible in the midst of harsh opposition.

Is there enough evidence for us to believe the Gospels?

Justin Holcomb is an Episcopal priest and a theology professor at Reformed Theological Seminary and Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary. He is author with his wife, Lindsey, of God Made All of Me , Is It My Fault? , and Rid of My Disgrace: Hope and Healing for Victims of Sexual Assault . Justin also has written or edited numerous other books on historical theology and biblical studies. You can find him on Facebook , Twitter , and at JustinHolcomb.com .

Now Trending

1 can i tell an unbeliever ‘jesus died for you’, 2 the faqs: southern baptists debate designation of women in ministry, 3 7 recommendations from my book stack, 4 artemis can’t undermine complementarianism, 5 ‘girls state’ highlights abortion’s role in growing gender divide.

The 11 Beliefs You Should Know about Jehovah’s Witnesses When They Knock at the Door

Here are the key beliefs of Jehovah’s Witnesses—and what the Bible really teaches instead.

8 Edifying Films to Watch This Spring

Easter Week in Real Time

Resurrected Saints and Matthew’s Weirdest Passage

I Believe in the Death of Julius Caesar and the Resurrection of Jesus Christ

Does 1 Peter 3:19 Teach That Jesus Preached in Hell?

The Plays C. S. Lewis Read Every Year for Holy Week

Latest Episodes

Lessons on evangelism from an unlikely evangelist.

Welcome and Witness: How to Reach Out in a Secular Age

How to Build Gospel Culture: A Q&A Conversation

Examining the Current and Future State of the Global Church

Trevin Wax on Reconstructing Faith

Gaming Alone: Helping the Generation of Young Men Captivated and Isolated by Video Games

Raise Your Kids to Know Their True Identity

Faith & Work: How Do I Glorify God Even When My Work Seems Meaningless?

Let’s Talk (Live): Growing in Gratitude

Getting Rid of Your Fear of the Book of Revelation

Looking for Love in All the Wrong Places: A Sermon from Julius Kim

Introducing The Acts 29 Podcast

University of Notre Dame

Notre Dame News

- Home ›

- News ›

The lasting impact of Martin Luther and the Reformation

Published: October 26, 2017

Author: Brandi Klingerman

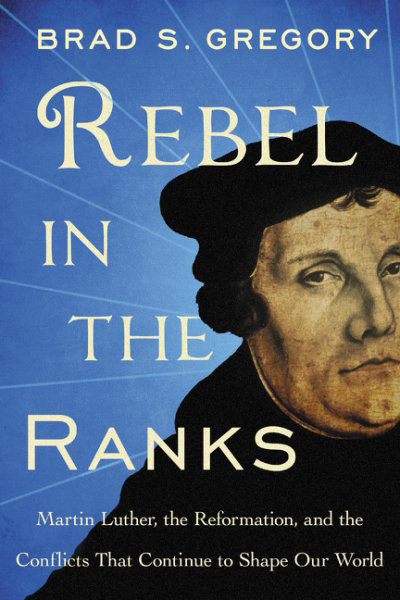

In October 1517, Martin Luther famously published his 95 Theses, unleashing criticisms that resulted in a rejection of the pope’s authority and fractured Christianity as he knew it. Exactly 500 years later, Brad S. Gregory , the Dorothy G. Griffin Professor of Early Modern European History at the University of Notre Dame, explains how this eventually, but unintentionally, led to a world of modern capitalism, polarizing politics and more.

In Gregory’s latest book, “Rebel in the Ranks” (HarperOne) , he explains that in the early 1500s religion was more than just one component of a person’s lifestyle in Western Europe and that Christianity, as the dominant religion, influenced all areas of Christians’ lives. However, after Luther’s initial concerns inadvertently created a movement — the Reformation — the result was a division between Catholicism and the varied Protestant traditions, conflicts among those traditions and, eventually, changes in how religion influenced people’s lives.

“The Reformation gave rise to constructive forms of several different Christian traditions, such as Lutheranism and Calvinism,” said Gregory. “But this also meant that people of differing faiths had to work out how they could coexist when religion had always been the key influence on politics, family and education. Although in the 17th and 18th centuries some political leaders continued to use the idea of religious uniformity to manage their territories, beginning with the 17th-century Dutch they realized that religious toleration was good for business.”

This effort to coexist and the desire for economic prosperity, Gregory argues, resulted in a “centuries-long process of secularization.” Religion was redefined and its scope restricted to a modern sense of religion as individual internal beliefs, forms of worship and devotional preferences. This made religion separable from politics, economics and other areas of life. With this, Western society has increasingly struggled to come to a consensus on politics, education and other social issues without the direction of an overarching faith or any shared substantive set of values to replace it.

“One result of the Reformation has been the political protection of individuals to believe or worship how they want,” said Gregory. “However, this freedom has also delivered — contrary to what Luther would have wanted — the right for people to practice no religion at all, and more, in recent decades, the seeming inability of citizens to agree on even the most basic norms important for shared political and social life.”

The Reformation’s unintended consequence of modern individual freedom has positives and negatives, he explained. Although people benefit from individual freedoms that were not available 500 years ago, these freedoms have also led, for instance, to the right for someone to purchase whatever they want without regard for the needs of anyone else.

“To match demand and thrive financially, factories produce the goods people want. In doing so, factories pollute the environment in ways that contribute to global warming. When religion was a pervasive and shared reality, individual freedom restrained the consumerist behaviors we see today,” said Gregory. “This is just one of many ways in which the long-term, unintended consequences of the Reformation are still influencing our lives today.”

Gregory is the director of the Notre Dame Institute for Advanced Study and author of “The Unintended Reformation . ” To learn more about him as well as his latest book, “Rebel in the Ranks,” visit https://ndias.nd.edu/books/rebel-in-the-ranks/ .

Contact : Brittany Kaufman, assistant director, Office of Media Relations, 574-631-6335, [email protected]

- Print Edition

- Medieval History

- Early Modern History

- Modern History

- Book Reviews

- Film Reviews

- Museum Reviews

- History at York

- Article Guidelines

The York Historian

What was the significance of the 95 theses.

What were the 95 Theses?

According to historic legend, Martin Luther posted a document on the door of the Wittenberg Church on the 31 st October 1517; a document later referred to as the 95 Theses. This document was questioning rather than accusatory, seeking to inform the Archbishop of Mainz that the selling of indulgences had become corrupt, with the sellers seeking solely to line their own pockets. It questioned the idea that the indulgences trade perpetuated – that buying a trinket could shave time off the stay of one’s loved ones in purgatory, sending them to a glorious Heaven.

It is important, however, to recognise that this was not the action of a man wanting to break away from the Catholic Church. When writing the 95 Theses, Luther simply intended to bring reform to the centre of the agenda for the Church Council once again; it cannot be stressed enough that he wanted to reform, rather than abandon, the Church.

Nonetheless, the 95 Theses were undoubtedly provocative, leading to debates across the German Lands about what it meant to be a true Christian, with some historians considering the document to be the start of the lengthy process of the Reformation. But why did Luther write them?

Why did Luther write the 95 Theses?

In particular, Luther was horrified by the fact that a large portion of the profits from this trade were being used to renovate St Peter’s Basilica in Rome. His outrage at this is evident from the 86 th thesis: ‘Why does the pope, whose wealth today is greater than the wealth of the richest Crassus, build the basilica of St Peter with the money of the poor rather than with his own money?’ Perhaps this is indicative of Luther’s opinion as opposing the financial extortion indulgences pressed upon the poor, rather than the theology which lay behind the process of freeing one’s loved ones from purgatory.

It is interesting to note that Luther also sent a copy of his 95 Theses directly to Archbishop Albrecht von Brandenburg. It appears that he legitimately believed that the Archbishop was not aware of the corruption inherent in the indulgence trade led by Tetzel. This is something which can be considered important later on, for it indicates that Luther did not consider the Church hierarchy redundant at this point.

Why were the 95 Theses significant?

Though the document itself has a debateable significance, the events which occurred because of its publication were paramount in Luther’s ideological and religious development. Almost immediately there was outrage at the ‘heresy’ which the Church viewed as implicit within the document. Despite the pressure upon Luther to immediately recant his position, he did not. This in part led to the Leipzig debate in summer 1519 with Johann Eck.

This debate forced Luther to clarify some of his theories and doctrinal stances against the representative of the Catholic Church. The debate focused largely on doctrine; in fact, the debate regarding indulgences was only briefly mentioned in the discussions between the two men. This seems surprising; Luther’s primary purpose in writing the 95 Theses was to protest the selling of indulgences. Why was this therefore not the primary purpose of the debate?

Ultimately the debate served to further Luther’s development of doctrine which opposed the traditional view of the Catholic Church. In the debate he was forced to conclude that Church Councils had the potential to be erroneous in their judgements. This therefore threw into dispute the papal hierarchy’s authority, and set him on his path towards evangelicalism and the formulation of the doctrine of justification by faith alone. Yet it is important to bear in mind that, had the pope offered a reconciliation, Luther would have returned to the doctrine of the established Church.

An interesting point to consider about the aftermath of the 95 Theses is the attitude of the Catholic Church. It immediately sought to identify Luther as someone who had strayed from the true way and was therefore a heretic; it refused to recognise that Luther had valid complaints which were shared by many across Western Christendom. The 95 Theses could have been taken at face value and used as an avenue to reform, as Luther intended. Instead, the papal hierarchy sought to discredit Luther, and keep to the status quo.

What made the 95 Theses significant?

A document written in Latin and posted on a door like most other academic debates, it does not seem obvious when considering the 95 Theses alone to see just how they became as significant as they did.

The translation of the Latin text into German also helped make the document significant. Translated in early 1518 by reformist friends of Luther, this widened the debate’s appeal simply because it made the subject matter accessible to a greater number of people. ‘Common’ folk who could read would have been able to read in German, rather than Latin. This therefore meant that they would be able to read the article for themselves and realise just how many of the arguments they identified with (or did not identify with, for that matter). The translation also meant that these literate folk could read the Theses aloud to a large audience; Bob Scribner argued that we should not forget the oral nature of the Reformation, beginning with one of the most divisive documents in history.

Finally, the 95 Theses can be considered significant because they were expressing sentiments that many ordinary folk felt themselves at the time. There had been a disillusionment with the Church and corruption within it for a great deal of time; the Reformatio Sigismundi of 1439 is a prime early example of a series of lists detailing the concerns of the people about the state of the Church. By the time of the Imperial Diet of Worms in 1521, there were 102 grievances with the Church, something overshadowed due to Martin Luther’s presence at this Diet. Many of the issues Luther highlighted were shared among the populace; it was due to the contextual factors of the printing press and the use of the German language that made this expression so significant.

It would not be surprising if, when posting his 95 Theses on the door of the chapel on the 31 st October 1517, Luther did not expect a great deal to change. At the time, he did not know what such an act would lead to. The events which occurred due to the Theses led to Luther clarifying his doctrinal position in a manner which led to his eventual repudiation of the decadence and corruption within the Catholic Church and his excommunication.

Yet we must remember that whilst the 95 Theses can be considered to constitute an extraordinary shift in the mentality of a disillusioned Christian, they are very unlikely to have achieved the same significance without the printing press. If the 95 Theses had been posted on the 31 st October 1417 , would the result have been the same?

Written by Victoria Bettney

Bibliography

Dixon, Scott C. The Reformation in Germany . Oxford : Blackwell, 2002.

Dixon, Scott C ed. The German Reformation: The Essential Readings . Oxford: Blackwell, 1999.

Lau, Franz and Bizer, Ernst. A History of the Reformation in Germany To 1555 . Translated by Brian Hardy. London: Adam and Charles Black, 1969.

Lindberg, Carter. The European Reformations . Oxford: Blackwell, 1996.

McGrath, Alister. Christian Theology: An Introduction . Oxford: Blackwell, 2007.

McGrath, Alister. Reformation Thought: An Introduction. Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1998.

Scribner, Robert. ‘Oral Culture and the Diffusion of Reformation Ideas,’ History of European Ideas 5, no. 3 (1984): 237-256.

“The 95 Theses,” http://www.luther.de/en/95thesen.html , accessed 29.10.15

Share this:

Post navigation, 3 thoughts on “ what was the significance of the 95 theses ”.

Interesting article! You rightly argue that the Theses were not the finished product but just a step in Luther’s theological development. That makes you think; should we really be celebrating 31 October 2017 as the 500th anniversary of the Reformation, or should we be remembering a different date?

Like Liked by 1 person

hit the griddy

Leave a comment Cancel reply

- Search for:

YAYAS’ York Historian

Subscribe to the york historian.

Enter your email address to follow The York Historian and receive notifications of new posts by email.

Email Address:

- View TheYorkHistorian’s profile on Facebook

- View TYorkHistorian’s profile on Twitter

- Entries feed

- Comments feed

- WordPress.com

- Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.

- Subscribe Subscribed

- Copy shortlink

- Report this content

- View post in Reader

- Manage subscriptions

- Collapse this bar

- Search Menu

- Sign in through your institution

- Advance articles

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access

- Why Publish with EHR?

- About The English Historical Review

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Books for Review

- Terms and Conditions

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

- < Previous

Luther’s Ninety-Five Theses and the Origins of the Reformation Narrative

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

C Scott Dixon, Luther’s Ninety-Five Theses and the Origins of the Reformation Narrative, The English Historical Review , Volume 132, Issue 556, June 2017, Pages 533–569, https://doi.org/10.1093/ehr/cex224

- Permissions Icon Permissions

With the quincentenary of the German Reformation now upon us, it is worth revisiting how, and why, the posting of the 95 theses emerged as such a defining moment in the Reformation story. It is easy to understand why it has assumed pride of place in modern histories. What is less easy to understand, however, is why the theses-posting emerged as the critical moment in the early modern accounts, for there were many other moments with even more drama and proximate significance for the Reformation. Moreover, the posting of theses had little shock-value at the time. Many professors posted academic theses, many reform-minded Christians had questioned indulgences, and many high-profile German intellectuals had written at least one critical piece against Rome. The following article begins with a survey of the origins of Reformation history and traces the incorporation of the theses-posting into the narrative stream. The second section examines the reasons why this act remained so prominent in the Lutheran memory during the two centuries after the Reformation by relating it to a broader analytical framework and sense of self-perception. The final section examines the process of reinterpretation that occurred during the period of late Lutheran Orthodoxy and the early Enlightenment, when scholars started to revisit the episode and sketch out the features of the modern view. The broader aim is to demonstrate how historical conditions can shape historical facts, even when those facts were bound to something as seemingly idealistic as the origins of a new Church.

On 13 October 1760, as a consequence of the ongoing hostilities between Prussian and Imperial troops in the Seven Years War, a relentless hail of bombs, grenades, and ‘fire balls’ rained down on the Saxon town of Wittenberg. According to the theology professor Christian Siegmund Georgi (1702–71), who was in Wittenberg at the time, most of the buildings in and near the centre of the town suffered direct hits and subsequently burned for a number of days. Away from the centre, however, and closer to the walls, some areas of the town had been spared and some buildings had survived the onslaught, including the Augusteum, the former monastery that had once served as a home to Martin Luther and still housed the famous Lutherstube ( Figure 1 ). But even the Augusteum was severely damaged and was only preserved because the intervals between strikes were long enough to allow for suppression of the fires. One building that did not survive the attack was the Castle Church, termed by Georgi the ‘mother church of all evangelical Lutheranism’, which had been reduced to a smouldering pile of stone and ash. 1 Numerous treasures went up in flames, including paintings by Lucas Cranach and Albrecht Dürer, late medieval imperial tombs, marble statues of the electors, epitaphs of renowned theologians, the church organ and Luther’s stone pulpit. But perhaps the most revered of all these casualties was the church door, the very door on which Luther had first posted the Ninety-Five Theses . No doubt there had been some repairs in the intervening centuries, but it was still thought to be authentic at the time of the bicentenary of the Reformation in 1717, and indeed some people held that Luther’s nails were still in the wood. 2 In October 1760, however, the Imperial ordnance set the church alight and the ‘beautiful temple’, to use Georgi’s words, ‘whence the teaching of the Gospel had first rung out and spread to the rest of the world’, was destroyed. 3

The bombardment. Georgi, Wittenbergische Klage-Geschichte (1760). Image by permission of SLUB Dresden, http://digital.slub-dresden.de/id334313465/10 ( CC-BY-SA 4.0 ).

By the time the Imperial battery had reduced the Castle Church (also known as All Saints Church) to pulverised stone and ash, the church door had already secured its place in Reformation history. Although the famous scene of Luther nailing the Ninety-Five Theses against indulgences on 31 October 1517 was based on very modest historical foundations, with a single recollection by Philipp Melanchthon (1497–1560) being the first and only public testimony to the event, Melanchthon’s reference proved authoritative enough for later generations of Lutherans to look back on this act as the starting point of the Reformation. At the time, however, the posting of the theses was just one scene among others, and in truth it does not appear to have had an immediate visual appeal. It was not until the gothic revival of the nineteenth century that artists such as Gustav König, Ferdinand Pauwels and Hugo Vogel began to pose Luther in front of the church door with hammer in hand. The elevation of the theses-posting to its current place in the public imagination as the Reformation’s dramatic scene nonpareil is a legacy of the nineteenth century. 4 Nevertheless, the theses-posting became a staple of the Reformation narrative soon after Melanchthon first published his recollection. No one doubted that it occurred on All Saints’ Day 1517; and, more to the point, all were in agreement that this act marked the origins of the Reformation and thus that 31 October 1517 was the moment when the Reformation began. In Georgi’s interior view of the Castle Church ( Figure 2 ), for instance, the door is clearly marked out (no. 59) and described as ‘the great door on which Doctor Luther of hallowed memory posted his 95 theses against Tetzel and thus brought about the blessed Reformation’. 5

The interior. Georgi, Wittenbergische Klage-Geschichte (1760). Image by permission of SLUB Dresden, http://digital.slub-dresden.de/id334313465/67 ( CC-BY-SA 4.0 ).

With the quincentenary of the German Reformation now upon us, it is worth revisiting how, and why, the theses-posting emerged as such a defining moment in the Reformation story. From the modern perspective it seems straightforward enough: this was the moment when Luther openly challenged the practice of indulgence-peddling, and with it the teaching and authority of the late medieval Catholic church. As a result of this act of defiance, Catholicism ultimately lost its monopoly of Christian salvation in the West. Furthermore, according to a long tradition of scholarship, this was the moment when the individual believer took his stand against the dead hand of tradition and the modern religious conscience was born. In the words of the church historian Ernst Wilhelm Benz, this act marks the instant when ‘western Christianity had reached a new stage of the religious conscience, one in which, for the individual, personal experience and personal witness becomes decisive in his relationship to God and to the community’. 6 The theologian Ulrich Barth has recently confirmed this view, claiming that the range and depth of social, moral and theological criticisms (both implicit and explicit) in the Ninety-Five Theses , compounded with Luther’s clearly stated doubts about the practice of indulgences and the power of the papacy, warrant the claim that this episode marked ‘the birth of religious autonomy’. 7

Freighted with this much importance, it is easy to understand why the posting of the theses has assumed pride of place in modern histories. What is less easy to understand, however, is why it emerged as the critical moment in early modern accounts, before the modern cult of individualism and its celebration of religious conscience; for not only were reports of the episode based on very shaky foundations but there were many other moments with even more drama and similar significance for the Reformation, from the debate with Johannes Eck in Leipzig and the burning of the papal Bull of excommunication to Luther’s appearance before Charles V in Worms (by which time the critical concern had shifted from the issue of indulgences to papal plenitude). Moreover, as a historical gesture with the symbolic weight identified by Benz, the posting of theses had little shock value at the time. Many professors posted academic theses, many reform-minded Christians had questioned indulgences, and many high-profile German intellectuals had written at least one critical piece against Rome.

The following article addresses this problem in three parts. It begins with a survey of the origins of Reformation history and traces the incorporation of the theses-posting into the narrative stream. The second section examines the reasons why this act remained so prominent in Lutheran memory during the two centuries after the Reformation by relating it to a broader theological framework, a providential interpretation of history and an evolving sense of self-perception. The final section examines the process of reinterpretation that occurred during the period of late Lutheran Orthodoxy and the early Enlightenment, when scholars started to revisit the episode and sketch the outlines of the modern view. A survey of the theses-posting is nothing new, of course, and indeed German historians have regularly re-examined the episode since the debate first became a national issue in the 1960s. Where this study departs from its predecessors is in its focus on the place and the meaning of the theses-posting within the evolving understanding of the German Reformation. It does not treat the episode as a fixed event in an unchanging narrative. Perceptions of Luther and the Reformation at the tail-end of the early modern period were different from perceptions at the beginning, so too the philosophies of history that ordered the past. And yet the theses-posting retained its prominence as the point of origin, the crucial moment in the story. Why was this? Why did this episode remain a fixed point in the history of the Reformation during a period when that entire history was reconsidered and reconceived? The main purpose of this study is to explain the reasons behind the durability of the theses-posting as the Reformation’s perceived moment of creation despite more than two centuries of historiographical change. The broader aim is to demonstrate how historical conditions can shape historical facts, even when those facts are bound to something as seemingly idealised as the origins of a new Church.

There is very little evidence to support the claim that Martin Luther (1483–1546) personally nailed a set of ninety-five theses against indulgences to the door of the Castle Church in Wittenberg on 31 October 1517. I do not intend to revisit all of the arguments for and against the theses-posting here, but some mention must be made of the weaknesses of the historical record, for this will have a bearing on the later discussion. 8 To begin with, as mentioned above, there is only one witness to this event, namely Melanchthon, who made reference to the theses-posting in the second volume of the Wittenberg Latin edition of Luther’s works (1546). 9 But the authority of Melanchthon’s testimony is solely based on his status and his role in the Reformation. In truth he was not even in Wittenberg at the time and was inconsistent in his recollections of the event. He mentioned it in a Sunday sermon in 1557, for example, but there was no reference to it in the short historical account of the Reformation that he placed in a time-capsule left in the church bell-tower the following year. 10 Even more significant is the fact that Luther himself never mentioned the posting of the theses. The indulgence debate clearly had priority in his recollections of the origins of the Reformation, and he did consider 31 October 1517 a day of special significance, but he made no reference to the theses and the door. At times the door fell within his frame of reference, as it did when the Swiss neo-Latin poet Simon Lemnius (1511–50) was caught peddling libellous anti-Wittenberg epigrams in front of the Castle Church entrance in 1538. Luther spoke from the pulpit against the dishonour brought upon the professors, the university, and the town; but he made no mention of the dishonour brought upon the very site where the Reformation was thought to have begun, even though he had become sentimental about other sites by this time. 11

There are other problems with established accounts, though some of the counter-arguments are based on circumstantial reasoning. For instance, although it was common to post theses for disputation on church doors, in Wittenberg, as in most other German universities, this was done by beadles rather than professors. Moreover, in Wittenberg, as the university statutes make clear, the disputation placards were to be posted on the doors of all the churches ( in valvis templorum ), not just the Castle Church. (And if Cranach’s image of the entrance to the Castle Church in 1509 is anywhere near the historical reality of 1517 [ Figure 3 ], multiple postings would have been advisable.) Equally troubling is the fact that historians have yet to find an extant copy of a Wittenberg print of the Ninety-Five Theses , though a summons to a public disputation of this kind was usually given in the form of a printed broadside. The few prints that do exist were published elsewhere (Nuremberg, Leipzig and Basel), and when Luther actually dispatched copies of the theses he seems to have sent them in handwritten form. 12 Even more perplexing is the issue of timing. In Melanchthon’s original account, Luther posted the theses ‘on the day before the feast of All Saints’ (‘pridie festi omnium Sanctorum’), that is, on 31 October 1517. He also dispatched letters to the archbishop of Mainz and the bishop of Brandenburg, both with a copy of the theses enclosed. The letter to Mainz still exists and is dated 31 October 1517. Context, content and later testimony would suggest that this letter to the archbishop was the first time that Luther made contact with him; however, in correspondence and recollections stretching from 1518 to 1545, Luther claimed that he had written to the bishops (sometimes suggesting more than two) before the posting of the theses. Only after waiting in vain for a response of some kind, he claimed, did he decide to make the theses public. If this was true, then Luther cannot have posted the theses on 31 October, for this was the day that he sent his appeal to the bishops. 13 Scholars were confronted with this discrepancy as soon as they began to piece together the Reformation narrative, for the letter to the archbishop was published in the Wittenberg (1539–59) and Jena (1554–8) editions of Luther’s works with the date at the bottom.

The church in 1509. Lucas Cranach, Dye zaigung des hochlobwirdigen hailigthums der stifftkirchen aller hailigen zu Wittenburg (Wittenberg, 1509). © The Trustees of the British Museum.

In the mid-sixteenth century, however, when German Protestants began to write the first histories of the Reformation, there was no need to call Melanchthon’s testimony into question. Admittedly, some of the earliest accounts make no reference to the event, including important foundational histories by contemporaries such as Johann Carion, Friedrich Myconius, Georg Spalatin and Johannes Sleidan. Nor did sharp-eyed Catholic controversialists such as Kilian Leib, Johannes Cochlaeus or Hieronymus Emser recall the scene. 14 They spoke of the publication or the dissemination of the theses rather than the posting on the church door. But once a shared stream of Reformation history began to emerge in the 1570s, the theses-posting became a staple of the core narrative. The church historian Volker Leppin has recently retraced this reception process during the first century of memorialisation. Drawing on the recollection of Melanchthon, the earliest authors to mention the act repeated the basic information provided by Melanchthon and occasionally added small details, such as that Luther was surrounded by pilgrims at the time. After these first attempts, the most influential account was given by Johannes Mathesius (1504–65) in his cycle of sermons on Luther’s life (1562–4). Mathesius included Melanchthon’s version of the theses-posting, yet he also related the dispatching of the letters to the bishops as described in the recollections of Luther. He did not try to reconcile the two accounts, nor did he depict Luther as a heroic figure who actively sought to challenge the teachings of the Church. According to Mathesius, Luther had been forced into issuing the theses by the actions of Johannes Tetzel, the Dominican friar who had been commissioned by Pope Leo X to preach the Jubilee indulgence in Germany. Only later, in the Luther biographies of the 1570s and 1580s, and beginning in particular with the works of Orthodox Lutheran historians such as Nikolaus Selnecker and Georg Glocker, do we meet Luther as the resolute reformer of the Church who was driven to take a stand against a corrupt medieval Catholic Church. We also start to see the theses-posting, rather than the dispatch of the letters to the bishops, emerge as the critical act of 1517. 15

A few crucial texts should be added to this survey. One is the reworking of Melanchthon’s version of Carion’s Chronicle by his son-in-law Caspar Peucer (1525–1602), who extended the narrative from the age of Charlemagne to the reign of the emperor Charles V. Though rather vague in the first Latin edition, the subsequent German translation clearly referred to the theses-posting as the ‘occasion and origin’ of the Reformation. 16 The other important vehicles for the spread and reception of the episode were the Wittenberg and Jena editions of Luther’s works. Given that Melanchthon’s preface first appeared in the Wittenberg version, this is a rather obvious point to make; and yet it is worth noting that the editors also added a marginal comment beside the Ninety-Five Theses in both editions, thereby reminding all subsequent scholars of the theses-posting every time they consulted the German translations. 17 Moreover, because the first editions of Luther’s works opened with the theses and the indulgence debate, they tended to sharpen the sense that Reformation itself began with the theses-posting. Both the Jena and the later Altenburg versions of Luther’s works were influential in this regard, as the Lutheran Pietist Gottfried Arnold (1666–1714) observed, for their chronological ordering provided ‘a much more exact notion of the entire sequence of events one after the other’. 18 Thus by the time Lutheran clergymen such as Selnecker and Glocker came to write their biographies, the theses-posting was already a central support of the broader narrative. It marked the terminus ante quem for the build-up to reform and the catalyst for the Reformation itself. To cite the words of one early biographer, 31 October 1517 was the date when Martin Luther

posted a set of public propositions and articles on the Castle Church, wherein, drawing on the Word of God and with a bountiful spirit, rigorously, just, and meet, he argued at length against the indulgence trade. This dispute was the beginning and the original cause of the Reformation and why the pure teaching of the Holy Gospel has been brought back to light. 19

The importance of 1517 was confirmed by the centenary celebrations of 1617, when Lutherans had the opportunity to celebrate the origins of the Reformation on a universal scale. Up to that point different regional churches had honoured different episodes, from Luther’s birth- and death-dates or the submission of the Augsburg Confession to events of local significance, such as the first evangelical communion in a particular place. 20 The 1617 centenary thus provided a common point of origin for public memorialisation across all these churches; but when the date arrived, because of the tense political situation and the need for Protestant unity, the main emphasis was placed on the celebration of the Reformation in general, or Protestant tropes such as the fall of the papal Antichrist or the spreading of the Word, rather than Luther’s theses-posting as the singular moment of origin. Indeed, in the initial plans for a general Protestant commemoration—which were largely put in motion by Friedrich V, the Reformed elector of the Palatinate—the main day of observation was set for 2 November. In most Lutheran territories, however, as in Electoral Saxony, the celebrations extended from 31 October to 2 November and were marked out by sermon cycles, special prayers of thanks, anniversary publications and the suspension of secular activities. 21 The theses-posting was not yet considered such a critical moment in the Reformation story that all celebrations had to be exclusively centred on this day (Hartmut Lehmann’s survey of ninety-four dated sermons, for instance, places just twenty-one on 31 October), and none of the anniversary pamphlets included an image of Luther in front of the church door; but the anniversary did confirm the widespread conceit that the Reformation originated with the posting of the theses and it did canonise this act in the public memory. Representative in this respect is the cycle of sermons preached in the Castle Church by the Wittenberg professors Friedrich Balduin, Nicolas Hunnius and Wolfgang Franz, all of whom stressed the significance of the theses as the starting-point of the Reformation. 22

For the lasting memorialisation of the theses-posting, however, perhaps the most important act of commemoration was the publication of the so-called Dream of Friedrich the Wise , a broadsheet engraving that appeared in 1617, which is thought to be the first visual representation of Luther in front of the church door ( Figure 4 ). References to the dream sequence experienced by Friedrich, who was the prince of Saxony at the time of the theses-posting, pre-date the broadsheet, but the appearance of this image, rich in detail and symbolism, marked an important juncture. As Robert Scribner observed, the image was significant because it invested the event with two forms of legitimacy. First, it provided a historical provenance for the idea of Luther and the church door. According to the pamphlet, Friedrich first related the dream to his chaplain Georg Spalatin, one of Luther’s Wittenberg contemporaries. Spalatin told Antonius Musa, the pastor of Rochlitz, who recorded it in a manuscript. While visiting the subsequent pastor of Rochlitz in 1591, the editor of the pamphlet claimed, he actually saw the manuscript and the description of the dream. With this, the historical foundations of the theses-posting were secured: all of these men were contemporary figures and their words and acts were joined by written testimony. The second form of legitimation was prophetic. In the dream related by Friedrich, which came to him as he contemplated the fate of souls in purgatory, God sent him a monk who seemed to be the natural son of Paul. Assured by God through the saints that he would not regret it if he let the monk write something on his Castle Church, Friedrich, having agreed to the request, next saw the vision of the monk scrawling oversized text on a door with a huge quill that reached all the way to Rome, where it went through the ears of a lion (representing Pope Leo X) and started to tip over the papal crown. Some of these symbols were the common stock of visual culture. Some could be deciphered with a modicum of historical knowledge. Others, such as the burning of a goose, which was an allusion to the prediction uttered by the heretic Jan Hus about the coming of Luther, were specific to the emerging prophecies of the Reformation. Harmonised in this image, they joined up the theses-posting with the emerging mytho-historical accounts of the Reformation. 23

The Dream of Frederick the Wise. Der Traum des Churfürsten Friedrich III. oder des Weisen (1617). ©The Trustees of the British Museum.