- About the Hub

- Announcements

- Faculty Experts Guide

- Subscribe to the newsletter

Explore by Topic

- Arts+Culture

- Politics+Society

- Science+Technology

- Student Life

- University News

- Voices+Opinion

- About Hub at Work

- Gazette Archive

- Benefits+Perks

- Health+Well-Being

- Current Issue

- About the Magazine

- Past Issues

- Support Johns Hopkins Magazine

- Subscribe to the Magazine

You are using an outdated browser. Please upgrade your browser to improve your experience.

Credit: Getty Images

What does the end of the COVID-19 pandemic look like?

Johns hopkins university public health experts offer insights into what will signal that sars-cov-2 is moving from pandemic to endemic, and how we might change our approach to the virus going forward.

By Amy Lunday

As the United States approaches the second anniversary of its initial COVID-19 shutdowns, we're daring to dream about what the end of the pandemic might look like. With omicron cases plummeting, indoor mask mandates in every state but Hawaii are set to expire —a change that would have seemed unthinkable just weeks ago.

Some are having an easier time than others embracing this shift in mindset. The idea of setting aside a bulk order of newly purchased, highly protective N95 masks might cause whiplash for some, while others gleefully head to their local pub to celebrate sans mask, NIOSH-approved or otherwise. Just because the rules are changing, does that mean the pandemic is really ending? Here, Johns Hopkins University public health experts offer insights into what signs their research tells them will signal that SARS-CoV-2 is moving from pandemic to endemic.

When it's less worrisome than the flu

David Dowdy , associate professor of epidemiology at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health

I t's difficult to know exactly how the pandemic will "end," but I think there's at least a reasonable chance that COVID-19 ends up being less of a public health concern than the flu. Even now, for someone who is vaccinated and boosted, the risk of hospitalization is higher if they were to get the flu than if they were to get COVID-19. I think it's too early to say whether COVID-19 waves will happen every winter, more frequently, or less frequently. But to my mind, if COVID-19 is not causing more people to get seriously ill than another "non-pandemic" infectious disease (seasonal flu, for example), it makes sense to declare the COVID-19 pandemic over.

As states drop COVID-19 restrictions, some experts warn it's premature to declare victory

Post-omicron life can be downright maddening, we’re entering the control phase of the pandemic, estimated 73% of u.s. now immune to omicron: is that enough, a return to mostly normal life while rebuilding trust in public health.

Tara Kirk Sell , senior scholar at the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security and an assistant professor at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health

T here won't be a clean end to the pandemic but it will stop being so front-and-center. As cases go down, protective measures will wane. At certain points, there will be surges in cases and some efforts to reduce spread of disease, like masking, may come back into our lives temporarily. Additional booster shots might be needed, and some people will get them, but like influenza vaccines, many in the U.S. won't or will never have gotten vaccinated in the first place and so there will also be occasional surges in hospitals. But while we return to mostly normal life, some things won't go back to normal—trust in public health has taken a hit. Health-related misinformation is more powerful than ever. This will be the work of the next generation of leaders in public health.

Greater consideration for mental health

Elizabeth Stuart , professor in the departments of Mental Health, Biostatistics, and Health Policy and Management in the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health

A s we consider the next stage of the pandemic, with hopefully fewer severe infections and perhaps less worry about physical health implications, the mental health consequences of the pandemic—for adults and kids—will continue. This includes need to support individuals who may experience mental health challenges after being infected with COVID, children and adults who lost a loved one to COVID, and those who experienced financial or other stresses during the pandemic. The mental health system was overburdened before the pandemic, with limited supply of providers. As articulated in my blog post with colleagues from Johns Hopkins and Columbia , moving forward we need a population mental health approach, including public health media campaigns, expanded screening, targeted interventions, increased capacity, and more surveillance and research. Setting up such a system will improve health and help move the country and world toward recovery in a way that will benefit all in the short and long term.

Image credit : Getty Images

Less transmission, more normalcy

Crystal Watson , a senior scholar at the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security and assistant professor in Environmental Health and Engineering at the Bloomberg School of Public Health

W hat I'm looking for is sustained reduced transmission. Also, if we do have new variants and new surges of cases, we want to see that immunity, through vaccination and prior infection, buffers against the large surges in hospitalizations and deaths that we've seen even with omicron. I think once we start to see infections and mild/moderate cases even more decoupled from hospitalizations and deaths, that's when we can start to take a deep breath and really think about how we treat this virus as a more routine infectious disease hazard rather than an acute pandemic threat.

A shift from pandemic to endemic, thanks to vaccines

Andrew Pekosz , professor of molecular microbiology and immunology at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health

W e're really in a situation where vaccination has laid the groundwork for strong immune responses. And now, even if you do get infected, the end result is a milder disease and a stronger immune response to protect you from the next variant. While I've learned not to try and predict what SARS-CoV-2 will do, it is a safe bet that more immunity in the population will limit disease and eventually reduce virus infections as well. SARS-CoV-2 eventually will put itself in a pigeonhole where it won't have much ability to change drastically and get around immune responses, and that will be the time when we can really start talking about this as something more like seasonal flu, as opposed to the pandemic virus that it is still to this day.

Rethinking our approach to respiratory illnesses beyond COVID-19

Brian Garibaldi , medical director of the Johns Hopkins Biocontainment Unit and associate professor of medicine at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine

M y hope is that as we move beyond the last stages of the omicron surge, we start to rethink our approach to respiratory viral illnesses in general. We have the ability to use data about community transmission of viruses such as SARS-CoV-2, RSV, and influenza to drive common sense local recommendations about how we can protect the most vulnerable among us from the risk of severe disease or death from these preventable infections. I would have no problem wearing a mask indoors when there are high levels of transmission of these viruses in my community in order to protect myself, my family, and others from getting sick.

I do think that we are approaching a point at which individuals can start to decide for themselves what level of risk they are willing to tolerate when it comes to wearing masks to prevent COVID-19. But I am not sure we are quite there yet. While cases are decreasing rapidly in the U.S., there remains a high level of community transmission in many places, and there are still millions of Americans who are either unvaccinated, or unable to mount an effective response to vaccines. And we are in the middle of winter which means that in many parts of the country people are gathering indoors more often and in greater numbers. I am also concerned about what might happen in terms of community transmission as mask requirements are rescinded in schools, where the majority of 5- to 12-year-olds are not yet vaccinated. Personally I plan to wear a mask indoors for the foreseeable future, mostly so that I don't get sick and have to miss clinical shifts in the hospital at a time when everyone is tired from working extraordinarily hard over the last two years. Vaccines work and I am fully vaccinated and boosted, so my risk of a severe disease or death from COVID-19 is very low. I hope that as people weigh decisions about their own behavior (for COVID and beyond), they take into account the circumstances of those around them.

Posted in Health , Voices+Opinion

Tagged public health , coronavirus , covid-19

You might also like

News network.

- Johns Hopkins Magazine

- Get Email Updates

- Submit an Announcement

- Submit an Event

- Privacy Statement

- Accessibility

Discover JHU

- About the University

- Schools & Divisions

- Academic Programs

- Plan a Visit

- my.JohnsHopkins.edu

- © 2024 Johns Hopkins University . All rights reserved.

- University Communications

- 3910 Keswick Rd., Suite N2600, Baltimore, MD

- X Facebook LinkedIn YouTube Instagram

Official websites use .gov

A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS

A lock ( ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

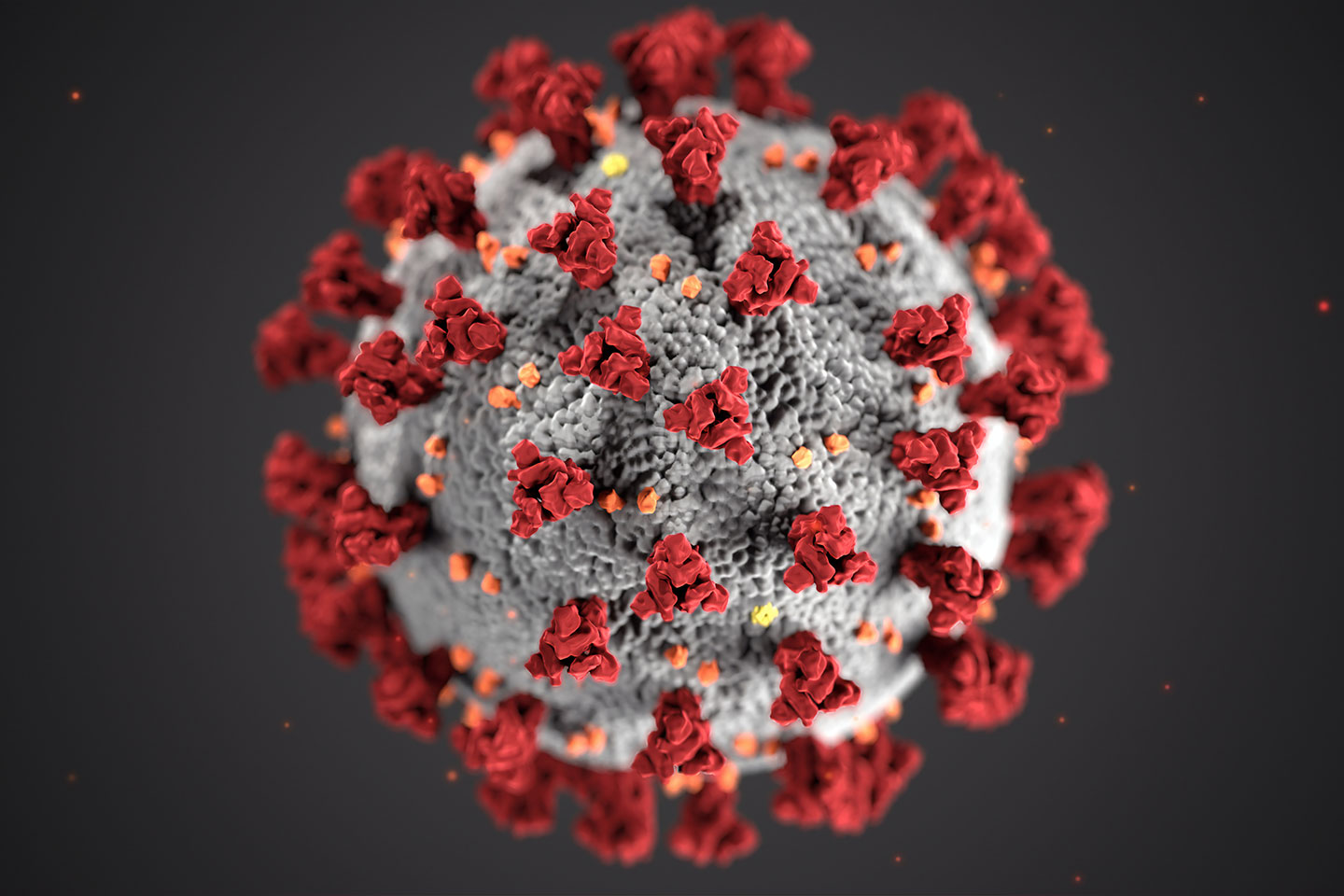

About COVID-19

What is covid-19.

COVID-19 (coronavirus disease 2019) is a disease caused by a virus named SARS-CoV-2. It can be very contagious and spreads quickly. Over one million people have died from COVID-19 in the United States.

COVID-19 most often causes respiratory symptoms that can feel much like a cold, the flu, or pneumonia. COVID-19 may attack more than your lungs and respiratory system. Other parts of your body may also be affected by the disease. Most people with COVID-19 have mild symptoms, but some people become severely ill.

Some people including those with minor or no symptoms will develop Post-COVID Conditions – also called “Long COVID.”

How does COVID-19 spread?

COVID-19 spreads when an infected person breathes out droplets and very small particles that contain the virus. Other people can breathe in these droplets and particles, or these droplets and particles can land on their eyes, nose, or mouth. In some circumstances, these droplets may contaminate surfaces they touch.

Anyone infected with COVID-19 can spread it, even if they do NOT have symptoms.

The risk of animals spreading the virus that causes COVID-19 to people is low. The virus can spread from people to animals during close contact. People with suspected or confirmed COVID-19 should avoid contact with animals.

What are antibodies and how do they help protect me?

Antibodies are proteins your immune system makes to help fight infection and protect you from getting sick in the future. A positive antibody test result can help identify someone who has had COVID-19 in the past or has been vaccinated against COVID-19. Studies show that people who have antibodies from an infection with the virus that causes COVID-19 can improve their level of protection by getting vaccinated.

Who is at risk of severe illness from COVID-19?

Some people are more likely than others to get very sick if they get COVID-19. This includes people who are older , are immunocompromised (have a weakened immune system), have certain disabilities , or have underlying health conditions . Understanding your COVID-19 risk and the risks that might affect others can help you make decisions to protect yourself and others .

What are ways to prevent COVID-19?

There are many actions you can take to help protect you, your household, and your community from COVID-19. CDC’s Respiratory Virus Guidance provides actions you can take to help protect yourself and others from health risks caused by respiratory viruses, including COVID-19. These actions include steps you can take to lower the risk of COVID-19 transmission (catching and spreading COVID-19) and lower the risk of severe illness if you get sick.

CDC recommends that you

- Stay up to date with COVID-19 vaccines

- Practice good hygiene (practices that improve cleanliness)

- Take steps for cleaner air

- Stay home when sick

- Seek health care promptly for testing and treatment when you are sick if you have risk factors for severe illness . Treatment may help lower your risk of severe illness.

Masks , physical distancing , and tests can provide additional layers of protection.

What are variants of COVID-19?

Viruses are constantly changing, including the virus that causes COVID-19. These changes occur over time and can lead to new strains of the virus or variants of COVID-19 . Slowing the spread of the virus, by protecting yourself and others , can help slow new variants from developing. CDC is working with state and local public health officials to monitor the spread of all variants, including Omicron.

- COVID-19 Testing

- COVID-19 Vaccines

- Preventing Respiratory Viruses

- Reinfection

- Difference Between Flu and COVID-19

- COVID Data Tracker

Search for and find historical COVID-19 pages and files. Please note the content on these pages and files is no longer being updated and may be out of date.

- Visit archive.cdc.gov for a historical snapshot of the COVID-19 website, capturing the end of the Federal Public Health Emergency on June 28, 2023.

- Visit the dynamic COVID-19 collection to search the COVID-19 website as far back as July 30, 2021.

To receive email updates about COVID-19, enter your email address:

Exit Notification / Disclaimer Policy

- The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) cannot attest to the accuracy of a non-federal website.

- Linking to a non-federal website does not constitute an endorsement by CDC or any of its employees of the sponsors or the information and products presented on the website.

- You will be subject to the destination website's privacy policy when you follow the link.

- CDC is not responsible for Section 508 compliance (accessibility) on other federal or private website.

When will the COVID-19 pandemic end? Experts explain

McKinsey experts have analyzed what the 'end' of COVID-19 could look like. Image: REUTERS/Ritzau Scanpix Denmark

.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo{-webkit-transition:all 0.15s ease-out;transition:all 0.15s ease-out;cursor:pointer;-webkit-text-decoration:none;text-decoration:none;outline:none;color:inherit;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:hover,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-hover]{-webkit-text-decoration:underline;text-decoration:underline;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:focus,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-focus]{box-shadow:0 0 0 3px rgba(168,203,251,0.5);} Sarun Charumilind

Matt craven, jessica lamb, shubham singhal, matt wilson.

.chakra .wef-9dduvl{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-9dduvl{font-size:1.125rem;}} Explore and monitor how .chakra .wef-15eoq1r{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-size:1.25rem;color:#F7DB5E;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-15eoq1r{font-size:1.125rem;}} COVID-19 is affecting economies, industries and global issues

.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;color:#2846F8;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{font-size:1.125rem;}} Get involved with our crowdsourced digital platform to deliver impact at scale

Stay up to date:.

- This article includes updated perspectives of McKinsey experts on when the coronavirus pandemic will end based on the latest data.

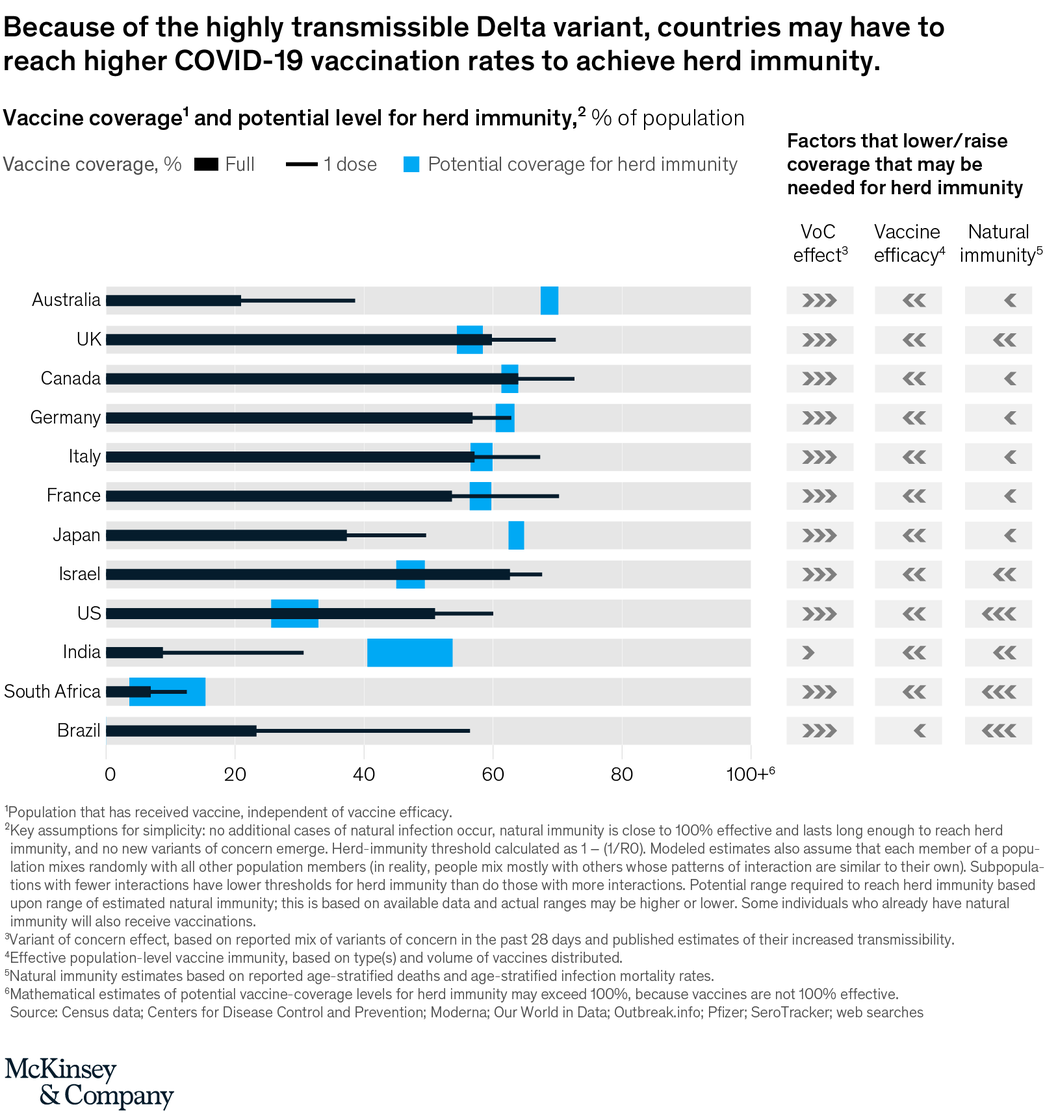

- Among high-income countries, cases caused by the Delta variant reversed the transition toward normalcy first in the UK and then across the world.

- Analysis suggests that the Delta variant has effectively moved overall herd immunity out of reach in most countries for the time being.

- However, as the UK has weathered a wave of Delta-driven cases, it may be able to resume the transition toward normalcy.

- The 'end' of COVID-19 might mean the point at which is can be managed as an endemic disease; however, the emergence of a significant new variant is the greatest risk which could hinder this.

- The data shown in the piece was correct as of 23/08/21.

Since the March installment in this series, many countries, including the United States, Canada, and those in Western Europe, experienced a measure of relief from the COVID-19 pandemic when some locales embarked on the second-quarter transition toward normalcy that we previously discussed. This progress was enabled by rapid vaccine rollout, with most Western European countries and Canada overcoming their slower starts during the first quarter of 2021 and passing the United States in the share of the population that is fully immunized. However, even that share has been too small for them to achieve herd immunity, because of the emergence of the more transmissible and more lethal Delta variant and the persistence of vaccine hesitancy.

Among high-income countries, cases caused by the Delta variant reversed the transition toward normalcy first in the United Kingdom, where a summertime surge of cases led authorities to delay lifting public-health restrictions, and more recently in the United States and elsewhere. The Delta variant increases the short-term burden of disease, causing more cases, hospitalizations, and deaths. Delta’s high transmissibility also makes herd immunity harder to achieve: a larger fraction of a given population must be immune to keep Delta from spreading within that population (see sidebar, “Understanding the Delta variant”). Our own analysis supports the view of others that the Delta variant has effectively moved herd immunity out of reach in most countries for now, although some regions may come close to it.

While the vaccines used in Western countries remain highly effective at preventing severe disease due to COVID-19, recent data from Israel, the United Kingdom, and the United States have raised new questions about the ability of these vaccines to prevent infection from the Delta variant. Serial blood tests suggest that immunity may wane relatively quickly. This has prompted some high-income countries to start offering booster doses to high-risk populations or planning for their rollout. Data from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention also suggest that vaccinated people who become infected with the Delta variant may transmit it efficiently.

These events and findings have raised new questions about when the pandemic will end. The United Kingdom’s experience nevertheless suggests that once a country has weathered a Delta-driven wave of cases, it may be able to relax public-health measures and resume the transition toward normalcy. Beyond that, a more realistic epidemiological endpoint might arrive not when herd immunity is achieved but when countries are able to control the burden of COVID-19 enough that it can be managed as an endemic disease. The biggest risk to a country’s ability to do this would likely then be the emergence of a new variant that is more transmissible, more liable to cause hospitalizations and deaths, or more capable of infecting people who have been vaccinated.

Raising vaccination rates will be essential to achieving a transition toward normalcy. Vaccine hesitancy, however, has proven to be a persistent challenge, both to preventing the spread of the Delta variant and to reaching herd immunity. The US Food and Drug Administration has now fully approved Pfizer’s COVID-19 vaccine, and other full approvals may follow soon, which could help increase vaccination rates. Vaccines are also likely to be made available to children in the coming months, making it possible to protect a group that comprises a significant share of the population in some countries.

In this article, we review developments since our March update, offer a perspective on the situation and evidence as of this writing, and present our scenario-based analysis of when a transition toward normalcy could occur.

Even without herd immunity, a transition toward normalcy is possible

We have written previously about two endpoints for the COVID-19 pandemic: a transition toward normalcy, and herd immunity. The transition would gradually normalize aspects of social and economic life, with some public-health measures remaining in effect as people gradually resume prepandemic activities. Many high-income countries did begin such a transition toward normalcy during the second quarter of this year, only to be hit with a new wave of cases caused by the Delta variant and exacerbated by vaccine hesitancy.

Indeed, our scenario analysis suggests that the United States, Canada, and many European countries would likely have reached herd immunity by now if they had faced only the ancestral SARS-CoV-2 virus and if a high percentage of those eligible to receive the vaccine had chosen to take it. But as the more infectious Delta variant becomes more prevalent within a population, more people within that population must be vaccinated before herd immunity can be achieved (Exhibit 1).

Vaccine hesitancy makes it all the more difficult to reach the population-wide vaccination level rates that confer herd immunity. Researchers are learning more about differences among individuals’ attitudes, which include both “cautious” and “unlikely to be vaccinated.” Meanwhile, social tolerance for vaccination incentives and mandates appears to be growing, with more European locations adopting vaccination passes and more large employers in the United States implementing vaccine mandates.

While it now appears unlikely that large countries will reach overall herd immunity (though some areas might), developments in the United Kingdom during the past few months may help illustrate the prospects for Western countries to transition back toward normalcy. Having suffered a wave of cases caused by the Delta variant during June and the first few weeks of July, the country delayed plans to ease many public-health restrictions and eventually did so on July 19, though expansive testing and genomic surveillance remain in place. UK case counts may fluctuate and targeted public-health measures may be reinstated, but our scenario analysis suggests that the country’s renewed transition toward normalcy is likely to continue unless a significant new variant emerges.

The United States, Canada, and much of the European Union are now in the throes of a Delta-driven wave of cases. While each country’s situation is different, most have again enacted public-health restrictions, thus reversing their transitions toward normalcy. The trajectory of the epidemic remains uncertain, but the United Kingdom’s experience and estimates of total immunity suggest that many of these countries are likely to see new cases peak late in the third quarter or early in the fourth quarter of 2021. As cases decline, our analysis suggests that the United States, Canada, and the European Union could restart the transition toward normalcy as early as the fourth quarter of 2021, provided that the vaccines used in these countries continue to be effective at preventing severe cases of COVID-19. Allowing for the risk of another new variant and the compound societal risk of a high burden of influenza, respiratory syncytial virus, and other winter respiratory diseases, the question for these countries will be whether they manage to arrive at a different epidemiological endpoint, as we discuss next.

Endemic COVID-19 may be a more realistic endpoint than herd immunity

We have previously written about herd immunity as a likely epidemiological endpoint for some countries, but the Delta variant has put this out of reach in the short term. Instead, it is most likely as of now that countries will reach an alternative epidemiological endpoint, where COVID-19 becomes endemic and societies decide—much as they have with respect to influenza and other diseases—that the ongoing burden of disease is low enough that COVID-19 can be managed as a constant threat rather than an exceptional one requiring society-defining interventions. One step toward this endpoint could be shifting the focus of public-health efforts from managing case counts to managing severe illnesses and deaths. Singapore’s government has announced that it will make this shift, and more countries may follow its lead.

Have you read?

Could covid-19 become endemic an expert explains what that means, 6 ways to ensure a fair and inclusive economic recovery from covid-19, covid-19 vaccine success can enable universal healthcare – here's how.

Other authors have compared the burden of COVID-19 with that of other diseases, such as influenza, as a way to understand when endemicity might occur. In the United States, COVID-19 hospitalization and mortality rates in June and July were nearing the ten-year average rates for influenza but have since risen. Today, the burden of disease caused by COVID-19 in vaccinated people in the United States is similar to or lower than the average burden of influenza over the last decade, while the risks from COVID-19 to unvaccinated people are significantly higher (Exhibit 2). This comparison should be qualified, insofar as the burden of COVID-19 is dynamic, currently increasing, and uneven geographically. It nevertheless helps illustrate the relative threat posed by the two diseases.

Countries experiencing a Delta-driven wave of cases may be more likely to begin managing COVID-19 as an endemic disease after cases go into decline. The United Kingdom appears to be making this shift now (though cases there were increasing as of this writing). For the United States and the European Union, scenario analysis suggests that the shift may begin in the fourth quarter of 2021 and continue into early 2022 (Exhibit 3). As it progresses, countries would likely achieve high levels of protection against hospitalization and death as a result of further vaccination efforts (which may be accelerated by fear of the Delta variant) and natural immunity from prior infection. In addition, boosters, full approval of vaccines (rather than emergency-use authorization), authorization of vaccines for children, and a continuation of the trend toward employer and government mandates and incentives for vaccination are all likely to increase immunity.

In 2000, Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance was launched at the World Economic Forum's Annual Meeting in Davos, with an initial pledge of $750 million from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation.

The aim of Gavi is to make vaccines more accessible and affordable for all - wherever people live in the world.

Along with saving an estimated 10 million lives worldwide in less than 20 years,through the vaccination of nearly 700 million children, - Gavi has most recently ensured a life-saving vaccine for Ebola.

At Davos 2016, we announced Gavi's partnership with Merck to make the life-saving Ebola vaccine a reality.

The Ebola vaccine is the result of years of energy and commitment from Merck; the generosity of Canada’s federal government; leadership by WHO; strong support to test the vaccine from both NGOs such as MSF and the countries affected by the West Africa outbreak; and the rapid response and dedication of the DRC Minister of Health. Without these efforts, it is unlikely this vaccine would be available for several years, if at all.

Read more about the Vaccine Alliance, and how you can contribute to the improvement of access to vaccines globally - in our Impact Story .

The authors wish to thank Xavier Azcue, Marie-Renée B-Lajoie, Andrew Doy, Bruce Jia, and Roxana Pamfil for their contributions to this article. This article was edited by Josh Rosenfield, an executive editor in the New York office.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Related topics:

The agenda .chakra .wef-n7bacu{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-weight:400;} weekly.

A weekly update of the most important issues driving the global agenda

.chakra .wef-1dtnjt5{display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;-webkit-flex-wrap:wrap;-ms-flex-wrap:wrap;flex-wrap:wrap;} More on Health and Healthcare Systems .chakra .wef-17xejub{-webkit-flex:1;-ms-flex:1;flex:1;justify-self:stretch;-webkit-align-self:stretch;-ms-flex-item-align:stretch;align-self:stretch;} .chakra .wef-nr1rr4{display:-webkit-inline-box;display:-webkit-inline-flex;display:-ms-inline-flexbox;display:inline-flex;white-space:normal;vertical-align:middle;text-transform:uppercase;font-size:0.75rem;border-radius:0.25rem;font-weight:700;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;line-height:1.2;-webkit-letter-spacing:1.25px;-moz-letter-spacing:1.25px;-ms-letter-spacing:1.25px;letter-spacing:1.25px;background:none;padding:0px;color:#B3B3B3;-webkit-box-decoration-break:clone;box-decoration-break:clone;-webkit-box-decoration-break:clone;}@media screen and (min-width:37.5rem){.chakra .wef-nr1rr4{font-size:0.875rem;}}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-nr1rr4{font-size:1rem;}} See all

Antimicrobial resistance is a leading cause of global deaths. Now is the time to act

Dame Sally Davies, Hemant Ahlawat and Shyam Bishen

May 16, 2024

Inequality is driving antimicrobial resistance. Here's how to curb it

Michael Anderson, Gunnar Ljungqvist and Victoria Saint

May 15, 2024

From our brains to our bowels – 5 ways the climate crisis is affecting our health

Charlotte Edmond

May 14, 2024

Health funders unite to support climate and disease research, plus other top health stories

Shyam Bishen

May 13, 2024

How midwife mentors are making it safer for women to give birth in remote, fragile areas

Anna Cecilia Frellsen

May 9, 2024

From Athens to Dhaka: how chief heat officers are battling the heat

Angeli Mehta

May 8, 2024

The end of the COVID-19 pandemic is in sight: WHO

Facebook Twitter Print Email

As the number of weekly reported deaths from COVID-19 plunged to its lowest since March 2020, the head of the World Health Organization (WHO) said on Wednesday that the end of the pandemic is now in sight.

“We have never been in a better position to end the pandemic”, Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus told journalists during his regular weekly press conference.

The UN health agency’s Director-General explained however, that the world is “not there yet”.

Finish line in sight

“A marathon runner does not stop when the finish line comes into view. She runs harder, with all the energy she has left. So must we. We can see the finish line. We’re in a winning position. But now is the worst time to stop running ”, he underscored.

He also warned that if the world does not take the opportunity now, there is still a risk of more variants, deaths, disruption, and uncertainty.

“So, let’s seize this opportunity”, he urged, announcing that WHO is releasing six short policy briefs that outline the key actions that all governments must take now to “finish the race”.

Urgent call

The policy briefs are a summary, based on the evidence and experience of the last 32 months, outlining what works best to save lives, protect health systems, and avoid social and economic disruption.

“[They] are an urgent call for governments to take a hard look at their policies and strengthen them for COVID-19 and future pathogens with pandemic potential”, Tedros explained.

The documents, which are available online , include recommendations regarding vaccination of most at-risk groups, continued testing and sequencing of the SARS-CoV-2 virus, and integrating effective treatment for COVID-19 into primary healthcare systems.

They also urge authorities to have plans for future surges, including the securing of supplies, equipment, and extra health workers.

The briefs also contain communications advice, including training health workers to identify and address misinformation, as well as creating high-quality informative materials.

Committed to the future

Tedros underscored that WHO has been working since New Year’s Eve 2019 to fight against the spread of COVID and will continue to do so until the pandemic is “truly over”.

“We can end this pandemic together, but only if all countries, manufacturers, communities and individuals step up and seize this opportunity”, he said.

Possible scenarios

Dr. Maria Van Kerkhove, WHO’s technical lead on COVID-19, highlighted that the virus is still “ intensely circulating” around the world and that the agency believes that case numbers being reported are an underestimate.

“We expect that there are going to be future waves of infection, potentially at different time points throughout the world caused by different subvariants of Omicron or even different variants of concern”, she said, reiterating her previous warning that the more the virus circulates, the more opportunities it has to mutate.

However, she said, these future waves do not need to translate into “waves or death” because there are now effective tools such as vaccines and antivirals specifically for COVID-19.

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

COVID-19 Pandemic

By: History.com Editors

Updated: March 11, 2024 | Original: April 25, 2023

The outbreak of the infectious respiratory disease known as COVID-19 triggered one of the deadliest pandemics in modern history. COVID-19 claimed nearly 7 million lives worldwide. In the United States, deaths from COVID-19 exceeded 1.1 million, nearly twice the American death toll from the 1918 flu pandemic . The COVID-19 pandemic also took a heavy toll economically, politically and psychologically, revealing deep divisions in the way that Americans viewed the role of government in a public health crisis, particularly vaccine mandates. While the United States downgraded its “national emergency” status over the pandemic on May 11, 2023, the full effects of the COVID-19 pandemic will reverberate for decades.

A New Virus Breaks Out in Wuhan, China

In December 2019, the China office of the World Health Organization (WHO) received news of an isolated outbreak of a pneumonia-like virus in the city of Wuhan. The virus caused high fevers and shortness of breath, and the cases seemed connected to the Huanan Seafood Wholesale Market in Wuhan, which was closed by an emergency order on January 1, 2020.

After testing samples of the unknown virus, the WHO identified it as a novel type of coronavirus similar to the deadly SARS virus that swept through Asia from 2002-2004. The WHO named this new strain SARS-CoV-2 (Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2). The first Chinese victim of SARS-CoV-2 died on January 11, 2020.

Where, exactly, the novel virus originated has been hotly debated. There are two leading theories. One is that the virus jumped from animals to humans, possibly carried by infected animals sold at the Wuhan market in late 2019. A second theory claims the virus escaped from the Wuhan Institute of Virology, a research lab that was studying coronaviruses. U.S. intelligence agencies maintain that both origin stories are “plausible.”

The First COVID-19 Cases in America

The WHO hoped that the virus outbreak would be contained to Wuhan, but by mid-January 2020, infections were reported in Thailand, Japan and Korea, all from people who had traveled to China.

On January 18, 2020, a 35-year-old man checked into an urgent care center near Seattle, Washington. He had just returned from Wuhan and was experiencing a fever, nausea and vomiting. On January 21, he was identified as the first American infected with SARS-CoV-2.

In reality, dozens of Americans had contracted SARS-CoV-2 weeks earlier, but doctors didn’t think to test for a new type of virus. One of those unknowingly infected patients died on February 6, 2020, but her death wasn’t confirmed as the first American casualty until April 21.

On February 11, 2020, the WHO released a new name for the disease causing the deadly outbreak: Coronavirus Disease 2019 or COVID-19. By mid-March 2020, all 50 U.S. states had reported at least one positive case of COVID-19, and nearly all of the new infections were caused by “community spread,” not by people who contracted the disease while traveling abroad.

At the same time, COVID-19 had spread to 114 countries worldwide, killing more than 4,000 people and infecting hundreds of thousands more. On March 11, the WHO made it official and declared COVID-19 a pandemic.

The World Shuts Down

Pandemics are expected in a globally interconnected world, so emergency plans were in place. In the United States, health officials at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the National Institutes of Health (NIH) set in motion a national response plan developed for flu pandemics.

State by state and city by city, government officials took emergency measures to encourage “ social distancing ,” one of the many new terms that became part of the COVID-19 vocabulary. Travel was restricted. Schools and churches were closed. With the exception of “essential workers,” all offices and businesses were shuttered. By early April 2020, more than 316 million Americans were under a shelter-in-place or stay-at-home order.

With more than 1,000 deaths and nearly 100,000 cases, it was clear by April 2020 that COVID-19 was highly contagious and virulent. What wasn’t clear, even to public health officials, was how individuals could best protect themselves from COVID-19. In the early weeks of the outbreak, the CDC discouraged people from buying face masks, because officials feared a shortage of masks for doctors and hospital workers.

By April 2020, the CDC revised its recommendations, encouraging people to wear masks in public, to socially distance and to wash hands frequently. President Donald Trump undercut the CDC recommendations by emphasizing that masking was voluntary and vowing not to wear a mask himself. This was just the beginning of the political divisions that hobbled the COVID-19 response in America.

Global Financial Markets Collapse

In the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic, with billions of people worldwide out of work, stuck at home, and fretting over shortages of essential items like toilet paper , global financial markets went into a tailspin.

In the United States, share prices on the New York Stock Exchange plummeted so quickly that the exchange had to shut down trading three separate times. The Dow Jones Industrial Average eventually lost 37 percent of its value, and the S&P 500 was down 34 percent.

Business closures and stay-at-home orders gutted the U.S. economy. The unemployment rate skyrocketed, particularly in the service sector (restaurant and other retail workers). By May 2020, the U.S. unemployment rate reached 14.7 percent, the highest jobless rate since the Great Depression .

All across America, households felt the pinch of lost jobs and lower wages. Food insecurity reached a peak by December 2020 with 30 million American adults—a full 14 percent—reporting that their families didn’t get enough to eat in the past week.

The economic effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, like its health effects, weren’t experienced equally. Black, Hispanic and Native Americans suffered from unemployment and food insecurity at significantly higher rates than white Americans.

Congress tried to avoid a complete economic collapse by authorizing a series of COVID-19 relief packages in 2020 and 2021, which included direct stimulus checks for all American families.

The Race for a Vaccine

A new vaccine typically takes 10 to 15 years to develop and test, but the world couldn’t wait that long for a COVID-19 vaccine. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) under the Trump administration launched “ Operation Warp Speed ,” a public-private partnership which provided billions of dollars in upfront funding to pharmaceutical companies to rapidly develop vaccines and conduct clinical trials.

The first clinical trial for a COVID-19 vaccine was announced on March 16, 2020, only days after the WHO officially classified COVID-19 as a pandemic. The vaccines developed by Moderna and Pfizer were the first ever to employ messenger RNA, a breakthrough technology. After large-scale clinical trials, both vaccines were found to be greater than 95 percent effective against infection with COVID-19.

A nurse from New York officially became the first American to receive a COVID-19 vaccine on December 14, 2020. Ten days later, more than 1 million vaccines had been administered, starting with healthcare workers and elderly residents of nursing homes. As the months rolled on, vaccine availability was expanded to all American adults, and then to teenagers and all school-age children.

By the end of the pandemic in early 2023, more than 670 million doses of COVID-19 vaccines had been administered in the United States at a rate of 203 doses per 100 people. Approximately 80 percent of the U.S. population received at least one COVID-19 shot, but vaccination rates were markedly lower among Black, Hispanic and Native Americans.

COVID-19 Deaths Heaviest Among Elderly and People of Color

In America, the COVID-19 pandemic impacted everyone’s lives, but those who died from the disease were far more likely to be older and people of color.

Of the more than 1.1 million COVID deaths in the United States, 75 percent were individuals who were 65 or older. A full 93 percent of American COVID-19 victims were 50 or older. Throughout the emergence of COVID-19 variants and the vaccine rollouts, older Americans remained the most at-risk for being hospitalized and ultimately dying from the disease.

Black, Hispanic and Native Americans were also at a statistically higher risk of developing life-threatening COVID-19 systems and succumbing to the disease. For example, Black and Hispanic Americans were twice as likely to be hospitalized from COVID-19 than white Americans. The COVID-19 pandemic shined light on the health disparities between racial and ethnic groups driven by systemic racism and lower access to healthcare.

Mental health also worsened during the COVID-19 pandemic. The anxiety of contracting the disease, and the stresses of being unemployed or confined at home, led to unprecedented numbers of Americans reporting feelings of depression and suicidal ideation.

A Time of Social & Political Upheaval

In the United States, the three long years of the COVID-19 pandemic paralleled a time of heightened political contention and social upheaval.

When George Floyd was killed by Minneapolis police on May 25, 2020, it sparked nationwide protests against police brutality and energized the Black Lives Matter movement. Because so many Americans were out of work or home from school due to COVID-19 shutdowns, unprecedented numbers of people from all walks of life took to the streets to demand reforms.

Instead of banding together to slow the spread of the disease, Americans became sharply divided along political lines in their opinions of masking requirements, vaccines and social distancing.

By March 2024, in signs that the pandemic was waning, the CDC issued new guidelines for people who were recovering from COVID-19. The agency said those infected with the virus no longer needed to remain isolated for five days after symptoms. And on March 10, 2024, the Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center stopped collecting data for its highly referenced COVID-19 dashboard.

Still, an estimated 17 percent of U.S. adults reported having experienced symptoms of long COVID, according to the Household Pulse Survey. The medical community is still working to understand the causes behind long COVID, which can afflict a patient for weeks, months or even years.

HISTORY Vault

Stream thousands of hours of acclaimed series, probing documentaries and captivating specials commercial-free in HISTORY Vault

“CDC Museum COVID Timeline.” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . “Coronavirus: Timeline.” U.S. Department of Defense . “COVID-19 and Related Vaccine Development and Research.” Mayo Clinic . “COVID-19 Cases and Deaths by Race/Ethnicity: Current Data and Changes Over Time.” Kaiser Family Foundation . “Number of COVID-19 Deaths in the U.S. by Age.” Statista . “The Pandemic Deepened Fault Lines in American Society.” Scientific American . “Tracking the COVID-19 Economy’s Effects on Food, Housing, and Employment Hardships.” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities . “U.S. Confirmed Country’s First Case of COVID-19 3 Years Ago.” CNN .

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

- Skip to main content

- Accessibility help

Information

We use cookies to collect anonymous data to help us improve your site browsing experience.

Click 'Accept all cookies' to agree to all cookies that collect anonymous data. To only allow the cookies that make the site work, click 'Use essential cookies only.' Visit 'Set cookie preferences' to control specific cookies.

Your cookie preferences have been saved. You can change your cookie settings at any time.

Coronavirus (COVID-19) and society: what matters to people in Scotland?

Findings from an open free text survey taken to understand in greater detail how the pandemic has changed Scotland.

- This research has captured the diversity and complexity of people’s experiences.

- People’s experiences of the pandemic and their ability to stay safe has been impacted by a range of factors, including: their geographical environment, their financial situation, profession, their living situation and if they have any physical or mental health conditions.

- Even though the direct level of threat from COVID-19 has reduced (for some people), there is still concern about the longer term harm and disruption that COVID-19 has caused to people and communities, and worry about the threat of future waves of infection.

- This report captures a number of specific suggestions for support. For example, support for key workers, creating safer public environments, wide-scale financial support, greater awareness around the experiences of those who are at higher risk to COVID-19 and putting in place robust processes for learning and reflection on the impact of the pandemic.

- Public engagement in this open and unfiltered format is an essential part of making sense of people’s attitudes and behaviours within the context of their life.

Email: [email protected]

There is a problem

Thanks for your feedback

Your feedback helps us to improve this website. Do not give any personal information because we cannot reply to you directly.

What is COVID-19 and how is it spread?

With nearly 550,000 people infected, almost 25,000 dead, and hundreds of millions in lockdown across the globe, the coronavirus pandemic has brought the world to a standstill. But what do we know about COVID-19 and what can we do to fight this pandemic?

- 27 March 2020

- by Priya Joi

Republish this article

If you would like to republish this article, please follow these steps: use the HTML below; do not edit the text; include the author’s byline; credit VaccinesWork as the original source; and include the page view counter script.

COVID-19 is a serious global infectious disease outbreak with nearly 550,000 cases and around 25,000 deaths worldwide. It is part of a family of viruses called coronaviruses that infect both animals and people. This particular one originated in China at the end of 2019, in the city of Wuhan, which has 11 million residents. In the past two decades coronavirus outbreaks have caused global concern, including one in 2003 with the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) and more recently in 2012 with the Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS).

COVID-19 can cause symptoms very similar to the flu – fever and a dry cough (the two most common symptoms) , fatigue, aches and pains, and nasal congestion. As the pandemic spread around the world, other symptoms such as a loss of sense of smell or taste have emerged – these are not yet conclusive evidence of infection with the new coronavirus, and the World Health Organization is investigating this.

Severe cases can lead to serious respiratory disease, and even pneumonia. Those most at risk are the elderly, or people with underlying medical issues, such as heart problems or diabetes. According to the most recent global numbers (27 March 2020), 14.8% of people over 80 years old, infected with the virus, have died from it, compared with 0.4% in people aged 40-49% and none in children under 9 years. The situation across countries is rapidly changing and these numbers will continue to change as the pandemic shifts.

Despite most deaths still being in older people, it is clear that many young people with the virus can still develop serious infection that requires hospitalisation.

The evidence so far indicates that the virus is spread from person to person through small respiratory droplets. When a person coughs or sneezes, these droplets can also land on nearby surfaces. There is also evidence that the COVID-19 virus can last on surfaces – especially plastic or metal – for up to 3 days. This is why advice to avoid catching COVID-19 has focused on handwashing with soap, the use of alcohol-based hand sanitising gels and keeping a distance from people who are symptomatic.

While many people can be seen to wear masks, especially on public transport, the World Health Organization (WHO) says that you only need to wear a mask if you are unwell or looking after someone who is sick and is in addition to the important measures above

IS THERE A TREATMENT OR VACCINE?

Right now, there are no antivirals or vaccines to treat or prevent COVID-19, although there are at least 44 potential coronavirus vaccines in development. Several antivirals, including those against flu and HIV are being tested to see if they could be used against the new coronavirus, as is chloroquine, a common antimalarial.

Even in an emergency, vaccines can take a long time to develop – no matter how quickly researchers race through the initial phase of identifying candidate vaccines and getting their vaccines into clinical testing. This is because taking the vaccine through the rigorous stages of testing for safety and efficacy can normally take several years. And it is still unclear whether the COVID-19 outbreak will have peaked before a vaccine can be rolled-out.

HOW BAD IS THIS PANDEMIC?

COVID-19 is a new coronavirus, which means that it is likely no-one has natural immunity to it. Coronaviruses such as MERS-CoV and SARS are on watchlists of infections with pandemic potential, along with Ebola and influenza . Since it began, COVID-19 has spread worldwide, leading the WHO to label it a pandemic and a “public health emergency of international concern.”

Based on available evidence, COVID-19 appears to have a fatality rate of 4.4%, much lower than 10% for SARS and around 30% for MERS-CoV. Yet this is not a reason to relax containment and control measures.

COVID-19 is more contagious than either SARS or MERS-CoV, and crucially, can be spread undetected. This is because many people with COVID-19 are either asymptomatic or have very mild symptoms, so they may not be adequately isolating themselves, and spreading the infection. Most countries around the world are now on lockdown to avoid spreading the virus any further, and allowing “a flattening of the curve” meaning avoiding cases from spiking and overwhelming health systems.

More from Priya Joi

How Africa is moving towards a homegrown response to health emergencies

Nanotechnology vaccines could protect against unknown coronaviruses

Malaria experts call for action on growing drug resistance in Africa

Nearly 7% of Americans struggle with Long COVID as infections surge

Recommended for you.

Could ‘Science Courts’ help build public trust?

Climate change is linked to worsening brain diseases – new study

The Viral Most Wanted: The Retroviruses

Cameroon hits back at yellow fever

From our brains to our bowels – 5 ways the climate crisis is affecting our health

In Sri Lanka, health workers go the extra mile to keep sex workers safe

Get the latest vaccineswork news, direct to your inbox.

Sign up to receive our top stories and key topics related to vaccination, including those related to the COVID-19 pandemic.

By clicking the "Subscribe" button, you are agreeing to receive the digital newsletter from Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance, agreeing to our terms of use and have read our privacy policy .

Website User Experience Survey

Thank you for visiting our website. Your input and time is valuable in helping us improve your experience. Please take less than a minute to provide feedback on your visit.

Thank you for visiting our website. Your input is important in helping us improve your experience. Please take a moment to answer a few questions about your visit.

- CORONAVIRUS COVERAGE

Here’s what the WHO report found on the origins of COVID-19

The long-awaited report answers some questions. But experts warn that discovering the virus’ true origins will take more digging.

A World Health Organization report released today says that SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, most likely leapt from animals to humans through an emissary animal.

The dispatch marks the culmination of a month-long mission by a team of Chinese and international experts to uncover COVID-19’s true origins. According to the report, it’s probable the virus originated in a bat or pangolin before making the leap to people. The report also says that it’s “extremely unlikely” the highly transmissible virus escaped from a laboratory in China.

“All hypotheses remain on the table,” Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, the WHO’s director general, said in a statement released today , indicating the organization’s research is ongoing.

While the 120-page report resolves some queries, it leaves others unanswered, including the geographic origin of the virus and exactly how it infected the first human. The methods used to gather physical evidence, as well as the way the report was written and compiled, have also raised alarm bells, causing some experts to question its credibility and to urge for more transparency in future studies.

“This report is a very important beginning, but it is not the end,” Ghebreyesus said, adding that until the source of the virus is found, “we must continue to follow the science and leave no stone unturned as we do.”

Path to infection

Most scientists are not surprised by the report’s conclusion that SARS-CoV-2 most likely jumped from an infected bat or pangolin to another animal and then to a human .

For Hungry Minds

“This is what many of us thought all along,” says Ian Lipkin , director of the Center for Infection and Immunity at Columbia University’s Mailman School of Public Health. But Lipkin adds that it’s “still speculative, because they haven’t identified an intermediary animal.” The report authors suggest examining supply chains from both livestock and wildlife farms to public markets to try and find out exactly which animals were involved.

If an intermediate host is part of the virus’ transmission chain, then it will be important to identify it so that mitigation measures can be put in place to prevent future outbreaks, says Theodora Hatziioannou , an associate professor of virology at Rockefeller University in New York City.

The report outlines another likely transmission scenario: that the virus leapt directly from a bat to a human. Robert Garry , a virologist at Tulane University School of Medicine who has studied the virus’s origin based on its genome, says such an event “is not too big a stretch.”

You May Also Like

Bird flu is spreading from pole to pole. Here’s why it matters.

What is white lung syndrome? Here's what to know about pneumonia

Multiple COVID infections can lead to chronic health issues. Here’s what to know.

However, the report questions whether the Huanan market was the location where the first animal-to-human transmission occurred, as some believed. The earliest reported case of COVID-19 did not have any link to the market. That suggests no firm conclusion can be drawn yet about the role of the Huanan market in the origin of the outbreak, or how the infection might have been introduced there, according to the report.

The hypothesis that frozen foods packaged and sold in markets might have played a role in SARS-CoV-2 transmission was also addressed. The report authors determined this so-called cold-chain route was possible and called for further case-control studies of outbreaks involving frozen products. They also recommended examining cold-chain products sold in the Huanan market from December 2019—if any are still available.

The report concludes that it was “extremely unlikely” the virus leaked from a Wuhan laboratory, a hypothesis propagated by former president Donald Trump but not often entertained by scientists. Robert Redfield, the former director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, continued to spread the idea as recently as last week during a CNN interview .

“There is no record of viruses closely related to SARS-CoV-2 in any laboratory” before the first cases of COVID-19 were recorded in December 2019, the WHO report says, with the authors adding that the risk of accidentally introducing the novel coronavirus in a laboratory setting by infecting a human “is extremely low.” The report does not call for additional research into the possibility of a leak from one of Wuhan’s laboratories.

“The preliminary conclusions are not outrageous, and they make perfect sense,” Hatziioannou says. “I know a lot of people would like to think it escaped from the lab, but I find conspiracy theories like that extremely hard to believe.”

Setbacks and scrutiny

However, the report is already facing scrutiny. Although it’s a joint effort between Chinese and WHO officials, investigators representing the WHO were denied permission to visit the Wuhan market and collect other data in the initial phases of the research, leading some pundits to say that the WHO was ceding responsibility to China, its second biggest funder behind the United States.

China also held back information about the initial outbreak in Wuhan, which delayed the WHO’s investigation.

Today, a joint statement issued by the governments of 14 countries, including the U.S., raised concerns about the transparency of future research into the origins of the novel virus.

“It is critical for independent experts to have full access to all pertinent human, animal, and environmental data, research, and personnel involved in the early stages of the outbreak relevant to determining how this pandemic emerge,” the statement reads.

Despite the study’s setbacks, Tulane University’s Garry believes the WHO report is credible. “It’s a very detailed report—it’s not the type of data you can make up,” he says.

Lipkin agrees: “It’s thorough, it’s exhaustive, it’s well written,” he says. “It’s what we predicted. That’s not to say that it wasn’t important to do this, but there’s nothing here to say, Ah-ha, I never thought this would be the case.”

Related Topics

- CORONAVIRUS

- PUBLIC HEALTH

- ANIMAL DISEASES

Do bats take flight during a solar eclipse? Here’s what we learned.

COVID-19 is more widespread in animals than we thought

A deer may have passed COVID-19 to a person, study suggests

A mysterious new respiratory illness is spreading in dogs. Here’s what we know.

$1,500 for 'naturally refined' coffee? Here's what that phrase really means.

- Environment

- Perpetual Planet

History & Culture

- History & Culture

- History Magazine

- Mind, Body, Wonder

- Paid Content

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Your US State Privacy Rights

- Children's Online Privacy Policy

- Interest-Based Ads

- About Nielsen Measurement

- Do Not Sell or Share My Personal Information

- Nat Geo Home

- Attend a Live Event

- Book a Trip

- Inspire Your Kids

- Shop Nat Geo

- Visit the D.C. Museum

- Learn About Our Impact

- Support Our Mission

- Advertise With Us

- Customer Service

- Renew Subscription

- Manage Your Subscription

- Work at Nat Geo

- Sign Up for Our Newsletters

- Contribute to Protect the Planet

Copyright © 1996-2015 National Geographic Society Copyright © 2015-2024 National Geographic Partners, LLC. All rights reserved

- Open access

- Published: 04 February 2022

Analysis of the COVID-19 pandemic: lessons towards a more effective response to public health emergencies

- Yibeltal Assefa ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-2393-1492 1 ,

- Charles F. Gilks 1 ,

- Simon Reid 1 ,

- Remco van de Pas 2 ,

- Dereje Gedle Gete 1 &

- Wim Van Damme 2

Globalization and Health volume 18 , Article number: 10 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

39k Accesses

35 Citations

10 Altmetric

Metrics details

The pandemic of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) is a timely reminder of the nature and impact of Public Health Emergencies of International Concern. As of 12 January 2022, there were over 314 million cases and over 5.5 million deaths notified since the start of the pandemic. The COVID-19 pandemic takes variable shapes and forms, in terms of cases and deaths, in different regions and countries of the world. The objective of this study is to analyse the variable expression of COVID-19 pandemic so that lessons can be learned towards an effective public health emergency response.

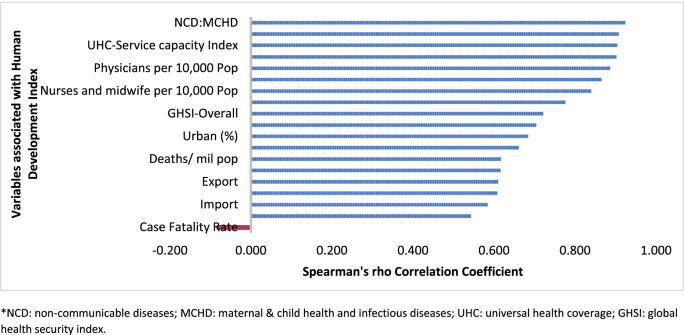

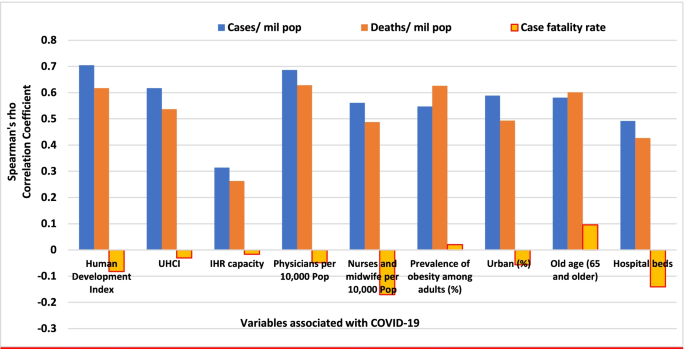

We conducted a mixed-methods study to understand the heterogeneity of cases and deaths due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Correlation analysis and scatter plot were employed for the quantitative data. We used Spearman’s correlation analysis to determine relationship strength between cases and deaths and socio-economic and health systems. We organized qualitative information from the literature and conducted a thematic analysis to recognize patterns of cases and deaths and explain the findings from the quantitative data.

We have found that regions and countries with high human development index have higher cases and deaths per million population due to COVID-19. This is due to international connectedness and mobility of their population related to trade and tourism, and their vulnerability related to older populations and higher rates of non-communicable diseases. We have also identified that the burden of the pandemic is also variable among high- and middle-income countries due to differences in the governance of the pandemic, fragmentation of health systems, and socio-economic inequities.

The COVID-19 pandemic demonstrates that every country remains vulnerable to public health emergencies. The aspiration towards a healthier and safer society requires that countries develop and implement a coherent and context-specific national strategy, improve governance of public health emergencies, build the capacity of their (public) health systems, minimize fragmentation, and tackle upstream structural issues, including socio-economic inequities. This is possible through a primary health care approach, which ensures provision of universal and equitable promotive, preventive and curative services, through whole-of-government and whole-of-society approaches.

The pandemic of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) is a timely reminder of the nature and impact of emerging infectious diseases that become Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC) [ 1 ]. The COVID-19 pandemic takes variable shapes and forms in how it affects communities in different regions and countries [ 2 , 3 ]. As of 12 January, 2022, there were over 314 million cases and over 5.5 million deaths notified around the globe since the start of the pandemic. The number of cases per million population ranged from 7410 in Africa to 131,730 in Europe while the number of deaths per million population ranged from 110 in Oceania to 2740 in South America. Case-fatality rates (CFRs) ranged from 0.3% in Oceania to 2.9% in South America [ 4 , 5 ]. Regions and countries with high human development index (HDI), which is a composite index of life expectancy, education, and per capita income indicators [ 6 ], are affected by COVID-19 more than regions with low HDI. North America and Europe together account for 55 and 51% of cases and deaths, respectively. Regions with high HDI are affected by COVID-19 despite their high universal health coverage index (UHCI) and Global Health Security index (GHSI) [ 7 ].

This seems to be a paradox (against the established knowledge that countries with weak (public) health systems capacity will have worse health outcomes) in that the countries with higher UHCI and GHSI have experienced higher burdens of COVID-19 [ 7 ]. The paradox can partially be explained by variations in testing algorithms, capacity for testing, and reporting across different countries. Countries with high HDI have health systems with a high testing capacity; the average testing rate per million population is less than 32, 000 in Africa and 160,000 in Asia while it is more than 800, 000 in HICs (Europe and North America). This enables HICs to identify more confirmed cases that will ostensibly increase the number of reported cases [ 3 ]. Nevertheless, these are insufficient to explain the stark differences between countries with high HDI and those with low HDI. Many countries with high HDI have a high testing rate and a higher proportion of symptomatic and severe cases, which are also associated with higher deaths and CFRs [ 7 ]. On the other hand, there are countries with high HDI that sustain a lower level of the epidemic than others with a similar high HDI. It is, therefore, vital to analyse the heterogeneity of the COVID-19 pandemic and explain why some countries with high HDI, UHCI and GHSI have the highest burden of COVID-19 while others are able to suppress their epidemics and mitigate its impacts.

The objective of this study was to analyse the COVID-19 pandemic and understand its variable expression with the intention to learn lessons for an effective and sustainable response to public health emergencies. We hypothesised that high levels of HDI, UHCI and GHSI are essential but not sufficient to prevent and control COVID-19.

We conducted an explanatory mixed-methods study to understand and explain the heterogeneity of the pandemic around the world. The study integrated quantitative and qualitative secondary data. The following steps were included in the research process: (i) collecting and analysing quantitative epidemiological data, (ii) conducting literature review of qualitative secondary data and (iii) evaluating countries’ pandemic responses to explain the variability in the COVID-19 epidemiological outcomes. The study then illuminated specific factors that were vital towards an effective and sustainable epidemic response.

We used the publicly available secondary data sources from Johns Hopkins University ( https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/data/new-cases ) for COVID-19 and UNDP 2020 HDI report ( http://hdr.undp.org/en/2019-report ) for HDI, demographic and epidemiologic variables. These are open data sources which are regularly updated and utilized by researchers, policy makers and funders. We performed a correlation analysis of the COVID-19 pandemic. We determined the association between COVID-19 cases, severity, deaths and CFRs at the 0.01 and 0.05 levels (2-tailed). We used Spearman’s correlation analysis, as there is no normal distribution of the variables [ 8 ].

The UHCI is calculated as the geometric mean of the coverage of essential services based on 17 tracer indicators from: (1) reproductive, maternal, newborn and child health; (2) infectious diseases; (3) non-communicable diseases; and, (4) service capacity and access and health security [ 9 ]. The GHSI is a composite measure to assess a country’s capability to prevent, detect, and respond to epidemics and pandemics [ 10 ].

We then conducted a document review to explain the epidemic patterns in different countries. Secondary data was obtained from peer-reviewed journals, reputable online news outlets, government reports and publications by public health-related associations, such as the WHO. To explain the variability of COVID-19 across countries, a list of 14 indicators was established to systematically assess country’s preparedness, actual pandemic response, and overall socioeconomic and demographic profile in the context of COVID-19. The indicators used in this study include: 1) Universal Health Coverage Index, 2) public health capacity, 3) Global Health Security Index, 4) International Health Regulation, 5) leadership, governance and coordination of response, 6) community mobilization and engagement, 7) communication, 8) testing, quarantines and social distancing, 9) medical services at primary health care facilities and hospitals, 10) multisectoral actions, 11) social protection services, 12) absolute and relative poverty status, 13) demography, and 14) burden of communicable and non-communicable diseases. These indicators are based on our previous studies and recommendation from the World Health Organization [ 3 , 4 ]. We conducted thematic analysis and synthesis to identify the factors that may explain the heterogeneity of the pandemic.

Heterogeneity of COVID-19 cases and deaths around the world: what can explain it?

Table 1 indicates that the pandemic of COVID-19 is heterogeneous around regions of the world. Figure 1 also shows that there is a strong and significant correlation between HDI and globalisation (with an increase in trade and tourism as proxy indicators) and a corresponding strong and significant correlation with COVID-19 burden.

Human development index and its correlates associated with COVID-19 in 189 countries*

Globalisation and pandemics interact in various ways, including through international trade and mobility, which can lead to multiple waves of infections [ 11 ]. In at least the first waves of the pandemic, countries with high import and export of consumer goods, food products and tourism have high number of cases, severe cases, deaths and CFRs. Countries with high HDI are at a higher risk of importing (and exporting) COVID-19 due to high mobility linked to trade and tourism, which are drivers of the economy. These may have led to multiple introductions of COVID-19 into these countries before border closures.

The COVID-19 pandemic was first identified in China, which is central to the global network of trade, from where it spread to all parts of the world, especially those countries with strong links with China [ 12 ]. The epidemic then spread to Europe. There is very strong regional dimension to manufacturing and trading, which could be facilitate the spread of the virus. China is the heart of ‘Factory Asia’; Italy is in the heart of ‘Factory Europe’; the United States is the heart of ‘Factory North America’; and Brazil is the heart of ‘Factory Latin America’ [ 13 ]. These are the countries most affected by COVID-19 during the first wave of the pandemic [ 2 , 3 , 14 ].

It is also important to note that two-third of the countries currently reporting more than a million cases are middle-income countries (MICs), which are not only major emerging market economies but also regional political powers, including the BRICS countries (Brazil, Russia, India and South Africa) [ 3 , 15 ]. These countries participate in the global economy, with business travellers and tourists. They also have good domestic transportation networks that facilitate the internal spread of the virus. The strategies that helped these countries to become emerging markets also put them at greater risk for importing and spreading COVID-19 due to their connectivity to the rest of the world.

In addition, countries with high HDI may be more significantly impacted by COVID-19 due to the higher proportion of the elderly and higher rates of non-communicable diseases. Figure 1 shows that there is a strong and significant correlation between HDI and demographic transition (high proportion of old-age population) and epidemiologic transition (high proportion of the population with non-communicable diseases). Countries with a higher proportion of people older than 65 years and NCDs (compared to communicable diseases) have higher burden of COVID-19 [ 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 ]. Evidence has consistently shown a higher risk of severe COVID-19 in older individuals and those with underlying health conditions [ 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 ]. CFR is age-dependent; it is highest in persons aged ≥85 years (10 to 27%), followed by those among persons aged 65–84 years (3 to 11%), and those among persons aged 55-64 years (1 to 3%) [ 26 ].

On the other hand, regions and countries with low HDI have, to date, experienced less severe epidemics. For instance, as of January 12, 2022, the African region has recorded about 10.3 million cases and 233,000 deaths– far lower than other regions of the world (Table 1 ) [ 27 ]. These might be due to lower testing rates in Africa, where only 6.5% of the population has been tested for the virus [ 14 , 28 ], and a greater proportion of infections may remain asymptomatic [ 29 ]. Indeed, the results from sero-surveys in Africa show that more than 80% of people infected with the virus were asymptomatic compared to an estimated 40-50% asymptomatic infections in HICs [ 30 , 31 ]. Moreover, there is a weak vital registration system in the region indicating that reports might be underestimating and underreporting the disease burden [ 32 ]. However, does this fully explain the differences observed between Africa and Europe or the Americas?

Other possible factors that may explain the lower rates of cases and deaths in Africa include: (1) Africa is less internationally connected than other regions; (2) the imposition of early strict lockdowns in many African countries, at a time when case numbers were relatively small, limited the number of imported cases further [ 2 , 33 , 34 ]; (3) relatively poor road network has also limited the transmission of the virus to and in rural areas [ 35 ]; (4) a significant proportion of the population resides in rural areas while those in urban areas spend a lot of their time mostly outdoors; (5) only about 3% of Africans are over the age of 65 (so only a small proportion are at risk of severe COVID-19) [ 36 ]; (6) lower prevalence of NCDs, as disease burden in Africa comes from infectious causes, including coronaviruses, which may also have cross-immunity that may reduce the risk of developing symptomatic cases [ 37 ]; and (7) relative high temperature (a major source of vitamin D which influences COVID-19 infection and mortality) in the region may limit the spread of the virus [ 38 , 39 ]. We argue that a combination of all these factors might explain the lower COVID-19 burden in Africa.

The early and timely efforts by African leaders should not be underestimated. The African Union, African CDC, and WHO convened an emergency meeting of all African ministers of health to establish an African taskforce to develop and implement a coordinated continent-wide strategy focusing on: laboratory; surveillance; infection prevention and control; clinical treatment of people with severe COVID-19; risk communication; and supply chain management [ 40 ]. In April 2021, African Union and Africa CDC launched the Partnerships for African Vaccine Manufacturing (PAVM), framework to expanding Africa’s vaccine manufacturing capacity for health security [ 41 ].

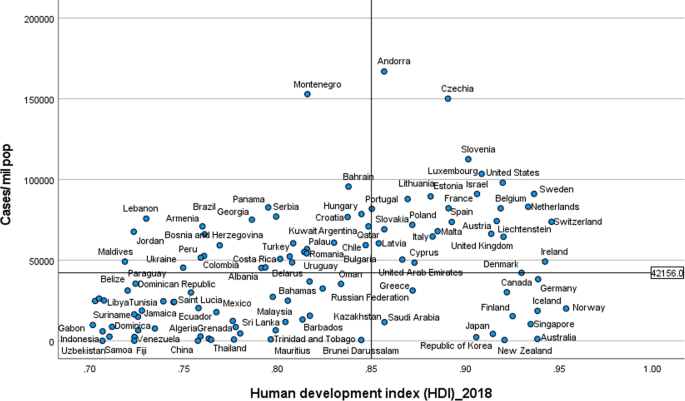

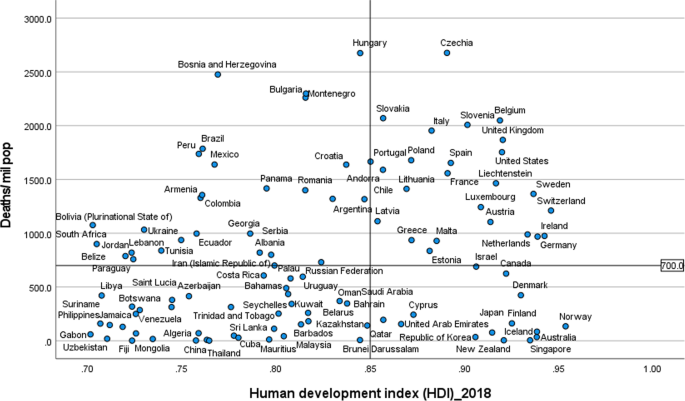

Heterogeneity of the pandemic among countries with high HDI: what can explain it?

Figures 2 and 3 illustrate the variability of cases and deaths due to the COVID-19 pandemic across high-income countries (HICs). Contrary to the overall positive correlation between high HDI and cases, deaths and fatality rates due to COVID-19, there are outlier HICs, which have been able to control the epidemic. Several HICs, such as New Zealand, Australia, South Korea, Japan, Denmark, Iceland, and Norway, managed to contain their epidemics (Figs. 2 and 3 ) [ 15 , 42 , 43 ]. It is important to note that most of these countries (especially the island states) have far less cross-border mobility than other HICs.

Scatter plot of COVID-19 cases per million population in countries with high human development index (> 0.70)

Scatter plot of COVID-19 deaths per million population in countries with high human development index (> 0.70)