by Dr. Martin Luther, 1517

Disputation of Doctor Martin Luther on the Power and Efficacy of Indulgences by Dr. Martin Luther (1517)

Out of love for the truth and the desire to bring it to light, the following propositions will be discussed at Wittenberg, under the presidency of the Reverend Father Martin Luther, Master of Arts and of Sacred Theology, and Lecturer in Ordinary on the same at that place. Wherefore he requests that those who are unable to be present and debate orally with us, may do so by letter. In the Name our Lord Jesus Christ. Amen. 1. Our Lord and Master Jesus Christ, when He said Poenitentiam agite, willed that the whole life of believers should be repentance. 2. This word cannot be understood to mean sacramental penance, i.e., confession and satisfaction, which is administered by the priests. 3. Yet it means not inward repentance only; nay, there is no inward repentance which does not outwardly work divers mortifications of the flesh. 4. The penalty [of sin], therefore, continues so long as hatred of self continues; for this is the true inward repentance, and continues until our entrance into the kingdom of heaven. 5. The pope does not intend to remit, and cannot remit any penalties other than those which he has imposed either by his own authority or by that of the Canons. 6. The pope cannot remit any guilt, except by declaring that it has been remitted by God and by assenting to God's remission; though, to be sure, he may grant remission in cases reserved to his judgment. If his right to grant remission in such cases were despised, the guilt would remain entirely unforgiven. 7. God remits guilt to no one whom He does not, at the same time, humble in all things and bring into subjection to His vicar, the priest. 8. The penitential canons are imposed only on the living, and, according to them, nothing should be imposed on the dying. 9. Therefore the Holy Spirit in the pope is kind to us, because in his decrees he always makes exception of the article of death and of necessity. 10. Ignorant and wicked are the doings of those priests who, in the case of the dying, reserve canonical penances for purgatory. 11. This changing of the canonical penalty to the penalty of purgatory is quite evidently one of the tares that were sown while the bishops slept. 12. In former times the canonical penalties were imposed not after, but before absolution, as tests of true contrition. 13. The dying are freed by death from all penalties; they are already dead to canonical rules, and have a right to be released from them. 14. The imperfect health [of soul], that is to say, the imperfect love, of the dying brings with it, of necessity, great fear; and the smaller the love, the greater is the fear. 15. This fear and horror is sufficient of itself alone (to say nothing of other things) to constitute the penalty of purgatory, since it is very near to the horror of despair. 16. Hell, purgatory, and heaven seem to differ as do despair, almost-despair, and the assurance of safety. 17. With souls in purgatory it seems necessary that horror should grow less and love increase. 18. It seems unproved, either by reason or Scripture, that they are outside the state of merit, that is to say, of increasing love. 19. Again, it seems unproved that they, or at least that all of them, are certain or assured of their own blessedness, though we may be quite certain of it. 20. Therefore by "full remission of all penalties" the pope means not actually "of all," but only of those imposed by himself. 21. Therefore those preachers of indulgences are in error, who say that by the pope's indulgences a man is freed from every penalty, and saved; 22. Whereas he remits to souls in purgatory no penalty which, according to the canons, they would have had to pay in this life. 23. If it is at all possible to grant to any one the remission of all penalties whatsoever, it is certain that this remission can be granted only to the most perfect, that is, to the very fewest. 24. It must needs be, therefore, that the greater part of the people are deceived by that indiscriminate and highsounding promise of release from penalty. 25. The power which the pope has, in a general way, over purgatory, is just like the power which any bishop or curate has, in a special way, within his own diocese or parish. 26. The pope does well when he grants remission to souls [in purgatory], not by the power of the keys (which he does not possess), but by way of intercession. 27. They preach man who say that so soon as the penny jingles into the money-box, the soul flies out [of purgatory]. 28. It is certain that when the penny jingles into the money-box, gain and avarice can be increased, but the result of the intercession of the Church is in the power of God alone. 29. Who knows whether all the souls in purgatory wish to be bought out of it, as in the legend of Sts. Severinus and Paschal. 30. No one is sure that his own contrition is sincere; much less that he has attained full remission. 31. Rare as is the man that is truly penitent, so rare is also the man who truly buys indulgences, i.e., such men are most rare. 32. They will be condemned eternally, together with their teachers, who believe themselves sure of their salvation because they have letters of pardon. 33. Men must be on their guard against those who say that the pope's pardons are that inestimable gift of God by which man is reconciled to Him; 34. For these "graces of pardon" concern only the penalties of sacramental satisfaction, and these are appointed by man. 35. They preach no Christian doctrine who teach that contrition is not necessary in those who intend to buy souls out of purgatory or to buy confessionalia. 36. Every truly repentant Christian has a right to full remission of penalty and guilt, even without letters of pardon. 37. Every true Christian, whether living or dead, has part in all the blessings of Christ and the Church; and this is granted him by God, even without letters of pardon. 38. Nevertheless, the remission and participation [in the blessings of the Church] which are granted by the pope are in no way to be despised, for they are, as I have said, the declaration of divine remission. 39. It is most difficult, even for the very keenest theologians, at one and the same time to commend to the people the abundance of pardons and [the need of] true contrition. 40. True contrition seeks and loves penalties, but liberal pardons only relax penalties and cause them to be hated, or at least, furnish an occasion [for hating them]. 41. Apostolic pardons are to be preached with caution, lest the people may falsely think them preferable to other good works of love. 42. Christians are to be taught that the pope does not intend the buying of pardons to be compared in any way to works of mercy. 43. Christians are to be taught that he who gives to the poor or lends to the needy does a better work than buying pardons; 44. Because love grows by works of love, and man becomes better; but by pardons man does not grow better, only more free from penalty. 45. 45. Christians are to be taught that he who sees a man in need, and passes him by, and gives [his money] for pardons, purchases not the indulgences of the pope, but the indignation of God. 46. Christians are to be taught that unless they have more than they need, they are bound to keep back what is necessary for their own families, and by no means to squander it on pardons. 47. Christians are to be taught that the buying of pardons is a matter of free will, and not of commandment. 48. Christians are to be taught that the pope, in granting pardons, needs, and therefore desires, their devout prayer for him more than the money they bring. 49. Christians are to be taught that the pope's pardons are useful, if they do not put their trust in them; but altogether harmful, if through them they lose their fear of God. 50. Christians are to be taught that if the pope knew the exactions of the pardon-preachers, he would rather that St. Peter's church should go to ashes, than that it should be built up with the skin, flesh and bones of his sheep. 51. Christians are to be taught that it would be the pope's wish, as it is his duty, to give of his own money to very many of those from whom certain hawkers of pardons cajole money, even though the church of St. Peter might have to be sold. 52. The assurance of salvation by letters of pardon is vain, even though the commissary, nay, even though the pope himself, were to stake his soul upon it. 53. They are enemies of Christ and of the pope, who bid the Word of God be altogether silent in some Churches, in order that pardons may be preached in others. 54. Injury is done the Word of God when, in the same sermon, an equal or a longer time is spent on pardons than on this Word. 55. It must be the intention of the pope that if pardons, which are a very small thing, are celebrated with one bell, with single processions and ceremonies, then the Gospel, which is the very greatest thing, should be preached with a hundred bells, a hundred processions, a hundred ceremonies. 56. The "treasures of the Church," out of which the pope. grants indulgences, are not sufficiently named or known among the people of Christ. 57. That they are not temporal treasures is certainly evident, for many of the vendors do not pour out such treasures so easily, but only gather them. 58. Nor are they the merits of Christ and the Saints, for even without the pope, these always work grace for the inner man, and the cross, death, and hell for the outward man. 59. St. Lawrence said that the treasures of the Church were the Church's poor, but he spoke according to the usage of the word in his own time. 60. Without rashness we say that the keys of the Church, given by Christ's merit, are that treasure; 61. For it is clear that for the remission of penalties and of reserved cases, the power of the pope is of itself sufficient. 62. The true treasure of the Church is the Most Holy Gospel of the glory and the grace of God. 63. But this treasure is naturally most odious, for it makes the first to be last. 64. On the other hand, the treasure of indulgences is naturally most acceptable, for it makes the last to be first. 65. Therefore the treasures of the Gospel are nets with which they formerly were wont to fish for men of riches. 66. The treasures of the indulgences are nets with which they now fish for the riches of men. 67. The indulgences which the preachers cry as the "greatest graces" are known to be truly such, in so far as they promote gain. 68. Yet they are in truth the very smallest graces compared with the grace of God and the piety of the Cross. 69. Bishops and curates are bound to admit the commissaries of apostolic pardons, with all reverence. 70. But still more are they bound to strain all their eyes and attend with all their ears, lest these men preach their own dreams instead of the commission of the pope. 71. He who speaks against the truth of apostolic pardons, let him be anathema and accursed! 72. But he who guards against the lust and license of the pardon-preachers, let him be blessed! 73. The pope justly thunders against those who, by any art, contrive the injury of the traffic in pardons. 74. But much more does he intend to thunder against those who use the pretext of pardons to contrive the injury of holy love and truth. 75. To think the papal pardons so great that they could absolve a man even if he had committed an impossible sin and violated the Mother of God -- this is madness. 76. We say, on the contrary, that the papal pardons are not able to remove the very least of venial sins, so far as its guilt is concerned. 77. It is said that even St. Peter, if he were now Pope, could not bestow greater graces; this is blasphemy against St. Peter and against the pope. 78. We say, on the contrary, that even the present pope, and any pope at all, has greater graces at his disposal; to wit, the Gospel, powers, gifts of healing, etc., as it is written in I. Corinthians xii. 79. To say that the cross, emblazoned with the papal arms, which is set up [by the preachers of indulgences], is of equal worth with the Cross of Christ, is blasphemy. 80. The bishops, curates and theologians who allow such talk to be spread among the people, will have an account to render. 81. This unbridled preaching of pardons makes it no easy matter, even for learned men, to rescue the reverence due to the pope from slander, or even from the shrewd questionings of the laity. 82. To wit: -- "Why does not the pope empty purgatory, for the sake of holy love and of the dire need of the souls that are there, if he redeems an infinite number of souls for the sake of miserable money with which to build a Church? The former reasons would be most just; the latter is most trivial." 83. Again: -- "Why are mortuary and anniversary masses for the dead continued, and why does he not return or permit the withdrawal of the endowments founded on their behalf, since it is wrong to pray for the redeemed?" 84. Again: -- "What is this new piety of God and the pope, that for money they allow a man who is impious and their enemy to buy out of purgatory the pious soul of a friend of God, and do not rather, because of that pious and beloved soul's own need, free it for pure love's sake?" 85. Again: -- "Why are the penitential canons long since in actual fact and through disuse abrogated and dead, now satisfied by the granting of indulgences, as though they were still alive and in force?" 86. Again: -- "Why does not the pope, whose wealth is to-day greater than the riches of the richest, build just this one church of St. Peter with his own money, rather than with the money of poor believers?" 87. Again: -- "What is it that the pope remits, and what participation does he grant to those who, by perfect contrition, have a right to full remission and participation?" 88. Again: -- "What greater blessing could come to the Church than if the pope were to do a hundred times a day what he now does once, and bestow on every believer these remissions and participations?" 89. "Since the pope, by his pardons, seeks the salvation of souls rather than money, why does he suspend the indulgences and pardons granted heretofore, since these have equal efficacy?" 90. To repress these arguments and scruples of the laity by force alone, and not to resolve them by giving reasons, is to expose the Church and the pope to the ridicule of their enemies, and to make Christians unhappy. 91. If, therefore, pardons were preached according to the spirit and mind of the pope, all these doubts would be readily resolved; nay, they would not exist. 92. Away, then, with all those prophets who say to the people of Christ, "Peace, peace," and there is no peace! 93. Blessed be all those prophets who say to the people of Christ, "Cross, cross," and there is no cross! 94. Christians are to be exhorted that they be diligent in following Christ, their Head, through penalties, deaths, and hell; 95. And thus be confident of entering into heaven rather through many tribulations, than through the assurance of peace.

This text was converted to ASCII text for Project Wittenberg by Allen Mulvey, and is in the public domain. You may freely distribute, copy or print this text. Please direct any comments or suggestions to:

Rev. Robert E. Smith Walther Library Concordia Theological Seminary.

E-mail: [email protected] Surface Mail: 6600 N. Clinton St., Ft. Wayne, IN 46825 USA Phone: (260) 452-3149 - Fax: (260) 452-2126

- Games & Quizzes

- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

Ninety-five Theses summary

Ninety-five Theses , Propositions for debate on the question of indulgence s, written by Martin Luther and, according to legend, posted on the door of the castle church in Wittenberg, Ger., on Oct. 31, 1517. This event is now seen as the beginning of the Protestant Reformation. The theses were written in response to the selling of indulgences to pay for the rebuilding of St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome. They represented an implicit criticism of papal policy and stressed the spiritual, inward character of the Christian faith. Widely circulated, they aroused much controversy. In 1518 Luther published a Latin manuscript with explanations of the theses.

Search a pre-defined list

The Whole Bible The Old Testament The New Testament ────────────── Pentateuch Historical Books Poetical Books Wisdom Literature Prophets Major Prophets Minor Prophets ────────────── The Gospels Luke-Acts Pauline Epistles General Epistles Johannine Writings ────────────── Genesis Exodus Leviticus Numbers Deuteronomy Joshua Judges Ruth 1 Samuel 2 Samuel 1 Kings 2 Kings 1 Chronicles 2 Chronicles Ezra Nehemiah Esther Job Psalms Proverbs Ecclesiastes Song of Songs Isaiah Jeremiah Lamentations Ezekiel Daniel Hosea Joel Amos Obadiah Jonah Micah Nahum Habakkuk Zephaniah Haggai Zechariah Malachi Matthew Mark Luke John Acts Romans 1 Corinthians 2 Corinthians Galatians Ephesians Philippians Colossians 1 Thessalonians 2 Thessalonians 1 Timothy 2 Timothy Titus Philemon Hebrews James 1 Peter 2 Peter 1 John 2 John 3 John Jude Revelation

OR Select a range of biblical books

Select a Beginning Point Genesis Exodus Leviticus Numbers Deuteronomy Joshua Judges Ruth 1 Samuel 2 Samuel 1 Kings 2 Kings 1 Chronicles 2 Chronicles Ezra Nehemiah Esther Job Psalms Proverbs Ecclesiastes Song of Songs Isaiah Jeremiah Lamentations Ezekiel Daniel Hosea Joel Amos Obadiah Jonah Micah Nahum Habakkuk Zephaniah Haggai Zechariah Malachi Matthew Mark Luke John Acts Romans 1 Corinthians 2 Corinthians Galatians Ephesians Philippians Colossians 1 Thessalonians 2 Thessalonians 1 Timothy 2 Timothy Titus Philemon Hebrews James 1 Peter 2 Peter 1 John 2 John 3 John Jude Revelation

Select an Ending Point Genesis Exodus Leviticus Numbers Deuteronomy Joshua Judges Ruth 1 Samuel 2 Samuel 1 Kings 2 Kings 1 Chronicles 2 Chronicles Ezra Nehemiah Esther Job Psalms Proverbs Ecclesiastes Song of Songs Isaiah Jeremiah Lamentations Ezekiel Daniel Hosea Joel Amos Obadiah Jonah Micah Nahum Habakkuk Zephaniah Haggai Zechariah Malachi Matthew Mark Luke John Acts Romans 1 Corinthians 2 Corinthians Galatians Ephesians Philippians Colossians 1 Thessalonians 2 Thessalonians 1 Timothy 2 Timothy Titus Philemon Hebrews James 1 Peter 2 Peter 1 John 2 John 3 John Jude Revelation

OR Custom Selection:

Use semicolons to separate groups: 'Gen;Jdg;Psa-Mal' or 'Rom 3-12;Mat 1:15;Mat 5:12-22'

Click to Change

Return to Top

Martin Luther :: Ninety-Five Theses on the Power of Indulgences

Disputation on the Power and Efficacy of Indulgences

In 1517, Martin Luther, an Augustinian monk posted upon the door of the Castle Church in Wittenberg (in the manner common to those issuing bulletin of an upcoming event or debate) the Ninety-Five Theses on the Power of Indulgences , what has commonly become known as The Ninety-Five Theses . The contents of his posting challenged the current teaching of the Church on penance and indulgences, questioning as well the authority of the pope. Reaction to Luther's Theses was immediate and strong, leading to his excommunication from the Roman Church and the eventual birth of the Protestant Reformation. Luther's historically important defense of the gospel is noted and celebrated annually on 31 October, Reformation Day. The following is the translated text of the Ninety-Five Theses .

Out of love and concern for the truth, and with the object of eliciting it, the following heads will be the subject of a public discussion at Wittenberg under the presidency of the reverend father, Martin Luther, Augustinian, Master of Arts and Sacred Theology, and duly appointed Lecturer on these subjects in that place. He requests that whoever cannot be present personally to debate the matter orally will do so in absence in writing.

- When our Lord and Master, Jesus Christ, said "Repent", He called for the entire life of believers to be one of repentance.

- The word cannot be properly understood as referring to the sacrament of penance, i.e. confession and satisfaction, as administered by the clergy.

- Yet its meaning is not restricted to repentance in one's heart; for such repentance is null unless it produces outward signs in various mortifications of the flesh.

- As long as hatred of self abides (i.e. true inward repentance) the penalty of sin abides, viz., until we enter the kingdom of heaven.

- The pope has neither the will nor the power to remit any penalties beyond those imposed either at his own discretion or by canon law.

- The pope himself cannot remit guilt, but only declare and confirm that it has been remitted by God; or, at most, he can remit it in cases reserved to his discretion. Except for these cases, the guilt remains untouched.

- God never remits guilt to anyone without, at the same time, making him humbly submissive to the priest, His representative.

- The penitential canons apply only to men who are still alive, and, according to the canons themselves, none applies to the dead.

- Accordingly, the Holy Spirit, acting in the person of the pope, manifests grace to us, by the fact that the papal regulations always cease to apply at death, or in any hard case.

- It is a wrongful act, due to ignorance, when priests retain the canonical penalties on the dead in purgatory.

- When canonical penalties were changed and made to apply to purgatory, surely it would seem that tares were sown while the bishops were asleep.

- In former days, the canonical penalties were imposed, not after, but before absolution was pronounced; and were intended to be tests of true contrition.

- Death puts an end to all the claims of the Church; even the dying are already dead to the canon laws, and are no longer bound by them.

- Defective piety or love in a dying person is necessarily accompanied by great fear, which is greatest where the piety or love is least.

- This fear or horror is sufficient in itself, whatever else might be said, to constitute the pain of purgatory, since it approaches very closely to the horror of despair.

- There seems to be the same difference between hell, purgatory, and heaven as between despair, uncertainty, and assurance.

- Of a truth, the pains of souls in purgatory ought to be abated, and charity ought to be proportionately increased.

- Moreover, it does not seem proved, on any grounds of reason or Scripture, that these souls are outside the state of merit, or unable to grow in grace.

- Nor does it seem proved to be always the case that they are certain and assured of salvation, even if we are very certain ourselves.

- Therefore the pope, in speaking of the plenary remission of all penalties, does not mean "all" in the strict sense, but only those imposed by himself.

- Hence those who preach indulgences are in error when they say that a man is absolved and saved from every penalty by the pope's indulgences.

- Indeed, he cannot remit to souls in purgatory any penalty which canon law declares should be suffered in the present life.

- If plenary remission could be granted to anyone at all, it would be only in the cases of the most perfect, i.e. to very few.

- It must therefore be the case that the major part of the people are deceived by that indiscriminate and high-sounding promise of relief from penalty.

- The same power as the pope exercises in general over purgatory is exercised in particular by every single bishop in his bishopric and priest in his parish.

- The pope does excellently when he grants remission to the souls in purgatory on account of intercessions made on their behalf, and not by the power of the keys (which he cannot exercise for them).

- There is no divine authority for preaching that the soul flies out of the purgatory immediately the money clinks in the bottom of the chest.

- It is certainly possible that when the money clinks in the bottom of the chest avarice and greed increase; but when the church offers intercession, all depends in the will of God.

- Who knows whether all souls in purgatory wish to be redeemed in view of what is said of St. Severinus and St. Pascal? (Note: Paschal I, pope 817-24. The legend is that he and Severinus were willing to endure the pains of purgatory for the benefit of the faithful).

- No one is sure of the reality of his own contrition, much less of receiving plenary forgiveness.

- Rare as is the man that is truly penitent, so rare is also the man who truly buys indulgences, i.e., such men are most rare.

- All those who believe themselves certain of their own salvation by means of letters of indulgence, will be eternally damned, together with their teachers.

- We should be most carefully on our guard against those who say that the papal indulgences are an inestimable divine gift, and that a man is reconciled to God by them.

- For the grace conveyed by these indulgences relates simply to the penalties of the sacramental "satisfactions" decreed merely by man.

- It is not in accordance with Christian doctrines to preach and teach that those who buy off souls, or purchase confessional licenses, have no need to repent of their own sins.

- Any Christian whatsoever, who is truly repentant, enjoys plenary remission from penalty and guilt, and this is given him without letters of indulgence.

- Any true Christian whatsoever, living or dead, participates in all the benefits of Christ and the Church; and this participation is granted to him by God without letters of indulgence.

- Yet the pope's remission and dispensation are in no way to be despised, for, as already said, they proclaim the divine remission.

- It is very difficult, even for the most learned theologians, to extol to the people the great bounty contained in the indulgences, while, at the same time, praising contrition as a virtue.

- A truly contrite sinner seeks out, and loves to pay, the penalties of his sins; whereas the very multitude of indulgences dulls men's consciences, and tends to make them hate the penalties.

- Papal indulgences should only be preached with caution, lest people gain a wrong understanding, and think that they are preferable to other good works: those of love.

- Christians should be taught that the pope does not at all intend that the purchase of indulgences should be understood as at all comparable with the works of mercy.

- Christians should be taught that one who gives to the poor, or lends to the needy, does a better action than if he purchases indulgences.

- Because, by works of love, love grows and a man becomes a better man; whereas, by indulgences, he does not become a better man, but only escapes certain penalties.

- Christians should be taught that he who sees a needy person, but passes him by although he gives money for indulgences, gains no benefit from the pope's pardon, but only incurs the wrath of God.

- Christians should be taught that, unless they have more than they need, they are bound to retain what is only necessary for the upkeep of their home, and should in no way squander it on indulgences.

- Christians should be taught that they purchase indulgences voluntarily, and are not under obligation to do so.

- Christians should be taught that, in granting indulgences, the pope has more need, and more desire, for devout prayer on his own behalf than for ready money.

- Christians should be taught that the pope's indulgences are useful only if one does not rely on them, but most harmful if one loses the fear of God through them.

- Christians should be taught that, if the pope knew the exactions of the indulgence-preachers, he would rather the church of St. Peter were reduced to ashes than be built with the skin, flesh, and bones of the sheep.

- Christians should be taught that the pope would be willing, as he ought if necessity should arise, to sell the church of St. Peter, and give, too, his own money to many of those from whom the pardon-merchants conjure money.

- It is vain to rely on salvation by letters of indulgence, even if the commissary, or indeed the pope himself, were to pledge his own soul for their validity.

- Those are enemies of Christ and the pope who forbid the word of God to be preached at all in some churches, in order that indulgences may be preached in others.

- The word of God suffers injury if, in the same sermon, an equal or longer time is devoted to indulgences than to that word.

- The pope cannot help taking the view that if indulgences (very small matters) are celebrated by one bell, one pageant, or one ceremony, the gospel (a very great matter) should be preached to the accompaniment of a hundred bells, a hundred processions, a hundred ceremonies.

- The treasures of the church, out of which the pope dispenses indulgences, are not sufficiently spoken of or known among the people of Christ.

- That these treasures are not temporal are clear from the fact that many of the merchants do not grant them freely, but only collect them.

- Nor are they the merits of Christ and the saints, because, even apart from the pope, these merits are always working grace in the inner man, and working the cross, death, and hell in the outer man.

- St. Laurence said that the poor were the treasures of the church, but he used the term in accordance with the custom of his own time.

- We do not speak rashly in saying that the treasures of the church are the keys of the church, and are bestowed by the merits of Christ.

- For it is clear that the power of the pope suffices, by itself, for the remission of penalties and reserved cases.

- The true treasure of the church is the Holy gospel of the glory and the grace of God.

- It is right to regard this treasure as most odious, for it makes the first to be the last.

- On the other hand, the treasure of indulgences is most acceptable, for it makes the last to be the first.

- Therefore the treasures of the gospel are nets which, in former times, they used to fish for men of wealth.

- The treasures of the indulgences are the nets to-day which they use to fish for men of wealth.

- The indulgences, which the merchants extol as the greatest of favours, are seen to be, in fact, a favourite means for money-getting.

- Nevertheless, they are not to be compared with the grace of God and the compassion shown in the Cross.

- Bishops and curates, in duty bound, must receive the commissaries of the papal indulgences with all reverence.

- But they are under a much greater obligation to watch closely and attend carefully lest these men preach their own fancies instead of what the pope commissioned.

- Let him be anathema and accursed who denies the apostolic character of the indulgences.

- On the other hand, let him be blessed who is on his guard against the wantonness and license of the pardon-merchant's words.

- In the same way, the pope rightly excommunicates those who make any plans to the detriment of the trade in indulgences.

- It is much more in keeping with his views to excommunicate those who use the pretext of indulgences to plot anything to the detriment of holy love and truth.

- It is foolish to think that papal indulgences have so much power that they can absolve a man even if he has done the impossible and violated the mother of God.

- We assert the contrary, and say that the pope's pardons are not able to remove the least venial of sins as far as their guilt is concerned.

- When it is said that not even St. Peter, if he were now pope, could grant a greater grace, it is blasphemy against St. Peter and the pope.

- We assert the contrary, and say that he, and any pope whatever, possesses greater graces, viz., the gospel, spiritual powers, gifts of healing, etc., as is declared in I Corinthians 12 [:28] .

- It is blasphemy to say that the insignia of the cross with the papal arms are of equal value to the cross on which Christ died.

- The bishops, curates, and theologians, who permit assertions of that kind to be made to the people without let or hindrance, will have to answer for it.

- This unbridled preaching of indulgences makes it difficult for learned men to guard the respect due to the pope against false accusations, or at least from the keen criticisms of the laity.

- They ask, e.g.: Why does not the pope liberate everyone from purgatory for the sake of love (a most holy thing) and because of the supreme necessity of their souls? This would be morally the best of all reasons. Meanwhile he redeems innumerable souls for money, a most perishable thing, with which to build St. Peter's church, a very minor purpose.

- Again: Why should funeral and anniversary masses for the dead continue to be said? And why does not the pope repay, or permit to be repaid, the benefactions instituted for these purposes, since it is wrong to pray for those souls who are now redeemed?

- Again: Surely this is a new sort of compassion, on the part of God and the pope, when an impious man, an enemy of God, is allowed to pay money to redeem a devout soul, a friend of God; while yet that devout and beloved soul is not allowed to be redeemed without payment, for love's sake, and just because of its need of redemption.

- Again: Why are the penitential canon laws, which in fact, if not in practice, have long been obsolete and dead in themselves-why are they, to-day, still used in imposing fines in money, through the granting of indulgences, as if all the penitential canons were fully operative?

- Again: since the pope's income to-day is larger than that of the wealthiest of wealthy men, why does he not build this one church of St. Peter with his own money, rather than with the money of indigent believers?

- Again: What does the pope remit or dispense to people who, by their perfect repentance, have a right to plenary remission or dispensation?

- Again: Surely a greater good could be done to the church if the pope were to bestow these remissions and dispensations, not once, as now, but a hundred times a day, for the benefit of any believer whatever.

- What the pope seeks by indulgences is not money, but rather the salvation of souls; why then does he suspend the letters and indulgences formerly conceded, and still as efficacious as ever?

- These questions are serious matters of conscience to the laity. To suppress them by force alone, and not to refute them by giving reasons, is to expose the church and the pope to the ridicule of their enemies, and to make Christian people unhappy.

- If therefore, indulgences were preached in accordance with the spirit and mind of the pope, all these difficulties would be easily overcome, and indeed, cease to exist.

- Away, then, with those prophets who say to Christ's people, "Peace, peace," where in there is no peace.

- Hail, hail to all those prophets who say to Christ's people, "The cross, the cross," where there is no cross.

- Christians should be exhorted to be zealous to follow Christ, their Head, through penalties, deaths, and hells.

- And let them thus be more confident of entering heaven through many tribulations rather than through a false assurance of peace.

Search Results in Other Versions

Search results by book, blb searches, search the bible.

Advanced Options

There are options set in 'Advanced Options'

Theological FAQs

Other Searches

Multi-Verse Retrieval

| |

* 'Number Delimiters' only apply to 'Paragraph Order'

Let's Connect

Daily devotionals.

Blue Letter Bible offers several daily devotional readings in order to help you refocus on Christ and the Gospel of His peace and righteousness.

- BLB Daily Promises

- Day by Day by Grace

- Morning and Evening

- Faith's Checkbook

- Daily Bible Reading

Daily Bible Reading Plans

Recognizing the value of consistent reflection upon the Word of God in order to refocus one's mind and heart upon Christ and His Gospel of peace, we provide several reading plans designed to cover the entire Bible in a year.

One-Year Plans

- Chronological

- Old Testament and New Testament Together

Two-Year Plan

- Canonical Five Day Plan

Recently Popular Pages

- H3068 - Yᵊhōvâ - Strong's Hebrew Lexicon (kjv)

- O.T. Names of God - Study Resources

- Hoekstra's Day by Day by Grace

- Invitation to Pray by C. H. Spurgeon

- David Guzik :: Hechos 9 – La Conversión de Saulo de Tarso

- Therein, Thereinto, Thereof, Thereon, Thereout, Thereto, Thereunto, Thereupon, Therewith - Vine's Expository Dictionary of New Testament Words

- Matthew Henry :: Commentary on Acts 26

- David Guzik :: 1 Samuel 22 – David en la Cueva de Adulam, Saúl Asesina a los Sacerdotes

Recently Popular Media

- Jehovah's Witnesses, Jesus and the Holy Trinity (Walter Martin)

- Revelation 2:18-29 [1990s] (Chuck Missler)

- Who Is Jesus Christ? (Tony Clark)

- Acts 26 (All) (Dr. J. Vernon McGee)

- Matthew 6:28-34 (Dr. J. Vernon McGee)

- Matthew 6:16-27 (Dr. J. Vernon McGee)

- Daniel 11-12 (1979-82 Audio) (Chuck Smith)

- Deuteronomy 30-34 (1979-82 Audio) (Chuck Smith)

- Psalms 20-30 (1979-82 Audio) (Chuck Smith)

- Acts 26:1 (Dr. J. Vernon McGee)

CONTENT DISCLAIMER:

The Blue Letter Bible ministry and the BLB Institute hold to the historical, conservative Christian faith, which includes a firm belief in the inerrancy of Scripture. Since the text and audio content provided by BLB represent a range of evangelical traditions, all of the ideas and principles conveyed in the resource materials are not necessarily affirmed, in total, by this ministry.

View Desktop Site

Bible Commentaries

Bible reference, biblical language resources, theological resources, topical indexes, help & support, devotionals.

Blue Letter Bible study tools make reading, searching and studying the Bible easy and rewarding.

Blue Letter Bible is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization

©2024 Blue Letter Bible | Privacy Policy

Copy Translation Order [?]

Translation selection order copied to bibles tab order, bibles tab order copied to translation selection order, translation selection order and bibles tab order have been reset.

You can copy the order of your preferred Bible translations from the Bibles Tab to the Version Picker (this popup) or vice versa. The Bibles Tab is found in the Tools feature on Bible pages:

Cite This Page

Note: MLA no longer requires the URL as part of their citation standard. Individual instructors or editors may still require the use of URLs.

Chicago Format

Share this page, email this page.

You must be logged in to send email.

Follow Blue Letter Bible

Subscribe to the newsletter.

| Interlinear |

| Bibles |

| Cross-Refs |

| Commentaries |

| Dictionaries |

| Miscellaneous |

Blue Letter Bible

Login to your account.

Email / username or password was incorrect!

Check your email for password retrieval

Keep me logged in!

Did you forget your password?

Register a new BLB account

Complete the form below to register [?]

Error: That Email is already registered

Error: Please provide a valid Email

Error: Passwords should have at least 6 characters

Error: Passwords do not match

Error: Please provide a valid first name

Error: That username is already taken

Error: Usernames should only contain letters, numbers, dots, dashes, or underscores

← Login to Your Account

Passwords should have at least 6 characters. Usernames should only contain letters, numbers, dots, dashes, or underscores.

Thank you for registering. A verification email has been sent to the address you provided.

Did You Know BLB Is User Supported?

Your partnership makes all we do possible. Would you prayerfully consider a gift of support today?

Cookie Notice: Our website uses cookies to store user preferences. By proceeding, you consent to our cookie usage. Please see Blue Letter Bible's Privacy Policy for cookie usage details.

Old Testament

New testament.

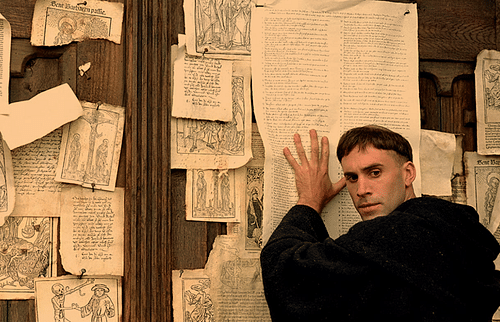

The 95 Theses: A reader’s guide

![95 Theses Luther's 95 Theses. c. 1557 [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://blogs.lcms.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/95_Thesen_Erste_Seite_banner-1.jpg)

by Kevin Armbrust

October 2017 marks the 500th anniversary of the Lutheran Reformation. Yet it is not the anniversary of any great statement Luther made as a reformer or in front of any court. There was no fiery and resounding speech given or dramatic showdown with the pope. On October 31, 1517, Martin Luther posted the “Disputation on the Power and Efficacy of Indulgences” to the church door in a small city called Wittenberg, Germany. This rather mundane academic document contained 95 theses for debate. Luther was a professor of theology at the University of Wittenberg, and he was permitted to call for public theological debate to discuss ideas and interpretations as he desired.

Yet this debate was not merely academic for Luther. According to a letter he wrote to the Archbishop of Mainz explaining the posting of the 95 Theses, Luther also desired to debate the concerns in the Theses for the sake of conscience.

Luther’s short preface explains:

“Out of love and zeal for truth and the desire to bring it to light, the following theses will be publicly discussed at Wittenberg under the chairmanship of the reverend father Martin Luther, Master of Arts and Sacred Theology and regularly appointed Lecturer on these subjects at that place. He requests that those who cannot be present to debate orally with us will do so by letter.”

The original text of the 95 Theses was written in Latin, since that was the academic language of Luther’s day. Luther’s theses were quickly translated into German, published in pamphlet form and spread throughout Germany.

Though English translations are readily available , many have found the 95 Theses difficult to read and comprehend. The short primer that follows may assist to highlight some of the theses and concepts Luther wished to explore.

Repentance and forgiveness dominate the content of the Theses. Since the question for Luther was the effectiveness of indulgences, he drove the discussion to the consideration of repentance and forgiveness in Christ. The first three theses address this:

1. When our Lord and Master Jesus Christ said, “Repent” [MATT. 4:17], he willed the entire life of believers to be one of repentance.

2. This word cannot be understood as referring to the sacrament of penance, that is, confession and satisfaction, as administered by the clergy.

3. Yet it does not mean solely inner repentance; such inner repentance is worthless unless it produces various outward mortifications of the flesh.

The pope and the Church cannot cause true repentance in a Christian and cannot forgive the sins of one who is guilty before Christ. The pope can only forgive that which Christ forgives. True repentance and eternal forgiveness come from Christ alone.

Luther identifies indulgences as a doctrine invented by man, since there is no scriptural promise or command for indulgences. Although Luther stops short of entirely condemning indulgences in the Theses, he nonetheless argues that the sale of indulgences and the trust in indulgences for salvation condemns both those who teach such notions and those who trust in them.

27. They preach only human doctrines who say that as soon as the money clinks into the money chest, the soul flies out of purgatory.

28. Those who believe that they can be certain of their salvation because they have indulgence letters will be eternally damned, together with their teachers.

God’s grace comes not through indulgences but through Christ. All Christians receive the blessings of God apart from indulgence letters.

36. Any truly repentant Christian has a right to full remission of penalty and guilt, even without indulgence letters.

37. Any true Christian, whether living or dead, participates in all the blessings of Christ and the church; and this is granted him by God, even without indulgence letters.

If Christians are going to spend money on something other than supporting their families, they should take care of the poor instead of buying indulgences.

43. Christians are to be taught that he who gives to the poor or lends to the needy does a better deed than he who buys indulgences.

The second half of the 95 Theses concentrates on the preaching of the true Word of the Gospel. Luther states that the teaching of indulgences should be lessened so that there might be more time for the proclamation of the true Gospel.

62. The true treasure of the church is the most holy gospel of the glory and grace of God.

63. But this treasure is naturally most odious, for it makes the first to be last [MATT. 20:16].

The Gospel of Christ is the true power for salvation (ROM. 1:16), not indulgences or even the power of the papal office.

76. We say on the contrary that papal indulgences cannot remove the very least of venial sins as far as guilt is concerned.

77. To say that even St. Peter, if he were now pope, could not grant greater graces is blasphemy against St. Peter and the pope.

78. We say on the contrary that even the present pope, or any pope whatsoever, has greater graces at his disposal, that is, the gospel, spiritual powers, gifts of healing, etc., as it is written in I Cor. 12[:28].

Preaching a false hope is really no hope at all. As a matter of fact, a false hope destroys and kills because it moves people away from Christ, where true salvation is found. The Gospel is found in Christ alone, which includes a cross and tribulations both large and small.

92. Away then with all those prophets who say to the people of Christ, “Peace, peace,” and there is no peace! [JER. 6:14].

93. Blessed be all those prophets who say to the people of Christ, “Cross, cross,” and there is no cross!

94. Christians should be exhorted to be diligent in following Christ, their head, through penalties, death, and hell;

95. And thus be confident of entering into heaven through many tribulations rather than through the false security of peace [ACTS 14:22].

Throughout the 95 Theses, Luther seeks to balance the role of the Church with the truth of the Gospel. Even as he desired to support the pope and his role in the Church, the false teaching of indulgences and the pope’s unwillingness to freely forgive the sins of all repentant Christians compelled him to speak up against these abuses.

Luther’s pastoral desire for all to trust in Christ alone for salvation drove him to post the 95 Theses. This same faith and hope sparked the Reformation that followed.

Dr. Kevin Armbrust is manager of editorial services for LCMS Communications.

Related Posts

How did Luther become a Lutheran?

Laughing with Luther

Luther alone?

About the author.

Kevin Armbrust

11 thoughts on “the 95 theses: a reader’s guide”.

Thx. This article does clear up a number of difficulties in interpreting the drift & theme of the 95 thesis. The fact that he supports the pope’s office at this juncture is new to me.

Very useful as I prepare a Sunday School lesson. Thanks

As important as the 95 Theses were for the beginning of the Reformation, and since they are not specifically part of the Lutheran Confessions, are there any of the Theses that we Lutherans consider unimportant or would rather avoid, theologically speaking?

I wish Luther was here, maybe things would change in our country and bring more folks to Jesus .

“When our Lord and master Jesus Christ says, ‘Repent,’ he wills that the entire life of the Christian be one of repentance.”

This seemingly joyless statement is often quoted, less often explained, and easily misunderstood. Is Jesus calling for the main theme of Christian life to be, “I’m ashamed of my sin”?

The full sentence from Matthew 4:17 is, “Repent, for the kingdom of heaven is at hand,” spoken when Jesus was beginning His ministry. This layman might paraphrase those words as, “Change your mindset, for divine authority is coming among you.” Indeed, when a very important person is coming to visit, we depart from business as usual, adjust our priorities, focus on careful preparation, and behave as befits the status of the visitor.

The word “repent” is recorded in Greek as “metanoeite”, which I understand to be not about remorse — not primarily about feelings at all — but about changing one’s mind or purpose.

The Christian life has a variety of themes, of which repentance is one. But repentance is not an end in itself. It is pivoting and changing course to pursue a direction that better fulfills God’s purposes as He gives the grace. For Jesus also willed “that you bear much fruit” (John 15:8) and “that your joy may be full” (John 15:11).

Could you explain number 93? I need this one explained. Jackie

Agreed. 93 is confusing.

In contrast to the false security of indulgences referenced in 92, number 93 references the preaching of true repentance. With true contrition and repentance over our sins, we Christians humble ourselves to the truth that we have earned our place on the cross as punishment and condemnation. But then we find the eternal surprise and wellspring of joy that our cross has been taken away from us and made Christ’s own. In exchange He gives us forgiveness, life and salvation!

Thank you, James Athey.

I myself did not fully understand this thesis yesterday, when I searched the Internet for an explanation of it. I found that I was not the only person who was confused by it. I also found that Luther explained it in a letter that he wrote to an Augustinian prior in 1516. Here is his explanation:

You are seeking and craving for peace, but in the wrong order. For you are seeking it as the world giveth, not as Christ giveth. Know you not that God is “wonderful among His saints,” for this reason, that He establishes His peace in the midst of no peace, that is, of all temptations and afflictions. It is said “Thou shalt dwell in the midst of thine enemies.” The man who possesses peace is not the man whom no one disturbs—that is the peace of the world; he is the man whom all men and all things disturb, but who bears all patiently, and with joy. You are saying with Israel, “Peace, peace,” and there is no peace. Learn to say rather with Christ: “The Cross, the Cross,” and there is no Cross. For the Cross at once ceases to be the Cross as soon as you have joyfully exclaimed, in the language of the hymn,

Blessed Cross, above all other, One and only noble tree.

It is posted here: http://www.ccel.org/ccel/luther/first_prin.iii.i.html

Magnificent!

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

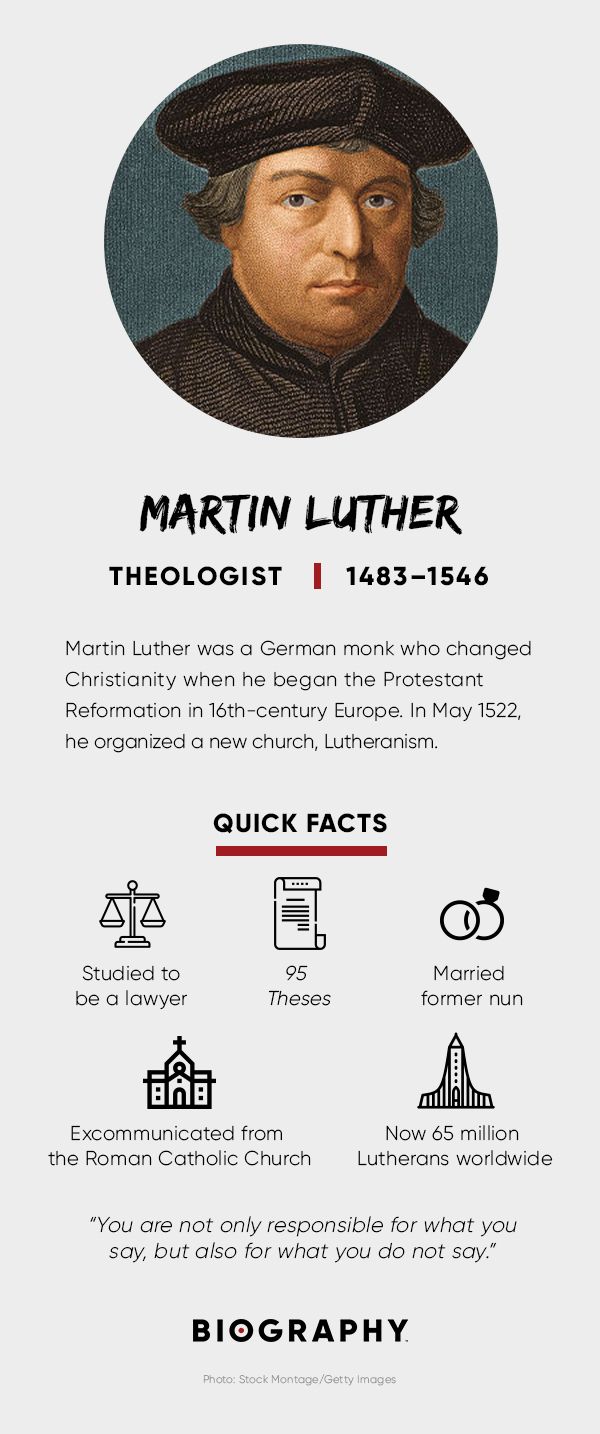

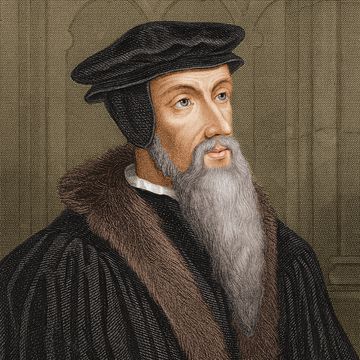

Martin Luther

(1483-1546)

Who Was Martin Luther?

Luther called into question some of the basic tenets of Roman Catholicism, and his followers soon split from the Roman Catholic Church to begin the Protestant tradition. His actions set in motion tremendous reform within the Church.

A prominent theologian, Luther’s desire for people to feel closer to God led him to translate the Bible into the language of the people, radically changing the relationship between church leaders and their followers.

Luther was born on November 10, 1483, in Eisleben, Saxony, located in modern-day Germany.

His parents, Hans and Margarette Luther, were of peasant lineage. However, Hans had some success as a miner and ore smelter, and in 1484 the family moved from Eisleben to nearby Mansfeld, where Hans held ore deposits.

Hans Luther knew that mining was a tough business and wanted his promising son to have a better career as a lawyer. At age seven, Luther entered school in Mansfeld.

At 14, Luther went north to Magdeburg, where he continued his studies. In 1498, he returned to Eisleben and enrolled in a school, studying grammar, rhetoric and logic. He later compared this experience to purgatory and hell.

In 1501, Luther entered the University of Erfurt , where he received a degree in grammar, logic, rhetoric and metaphysics. At this time, it seemed he was on his way to becoming a lawyer.

Becoming a Monk

In July 1505, Luther had a life-changing experience that set him on a new course to becoming a monk.

Caught in a horrific thunderstorm where he feared for his life, Luther cried out to St. Anne, the patron saint of miners, “Save me, St. Anne, and I’ll become a monk!” The storm subsided and he was saved.

Most historians believe this was not a spontaneous act, but an idea already formulated in Luther’s mind. The decision to become a monk was difficult and greatly disappointed his father, but he felt he must keep a promise.

Luther was also driven by fears of hell and God’s wrath, and felt that life in a monastery would help him find salvation.

The first few years of monastic life were difficult for Luther, as he did not find the religious enlightenment he was seeking. A mentor told him to focus his life exclusively on Jesus Christ and this would later provide him with the guidance he sought.

Disillusionment with Rome

At age 27, Luther was given the opportunity to be a delegate to a Catholic church conference in Rome. He came away more disillusioned, and very discouraged by the immorality and corruption he witnessed there among the Catholic priests.

Upon his return to Germany, he enrolled in the University of Wittenberg in an attempt to suppress his spiritual turmoil. He excelled in his studies and received a doctorate, becoming a professor of theology at the university (known today as Martin Luther University Halle-Wittenberg ).

Through his studies of scripture, Luther finally gained religious enlightenment. Beginning in 1513, while preparing lectures, Luther read the first line of Psalm 22, which Christ wailed in his cry for mercy on the cross, a cry similar to Luther’s own disillusionment with God and religion.

Two years later, while preparing a lecture on Paul’s Epistle to the Romans, he read, “The just will live by faith.” He dwelled on this statement for some time.

Finally, he realized the key to spiritual salvation was not to fear God or be enslaved by religious dogma but to believe that faith alone would bring salvation. This period marked a major change in his life and set in motion the Reformation.

DOWNLOAD BIOGRAPHY'S MARTIN LUTHER FACT CARD

'95 Theses'

On October 31, 1517, Luther, angry with Pope Leo X’s new round of indulgences to help build St. Peter’s Basilica , nailed a sheet of paper with his 95 Theses on the University of Wittenberg’s chapel door.

Though Luther intended these to be discussion points, the 95 Theses laid out a devastating critique of the indulgences - good works, which often involved monetary donations, that popes could grant to the people to cancel out penance for sins - as corrupting people’s faith.

Luther also sent a copy to Archbishop Albert Albrecht of Mainz, calling on him to end the sale of indulgences. Aided by the printing press , copies of the 95 Theses spread throughout Germany within two weeks and throughout Europe within two months.

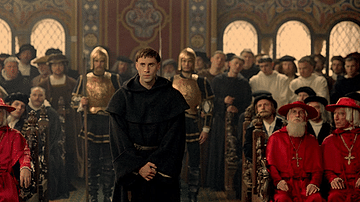

The Church eventually moved to stop the act of defiance. In October 1518, at a meeting with Cardinal Thomas Cajetan in Augsburg, Luther was ordered to recant his 95 Theses by the authority of the pope.

Luther said he would not recant unless scripture proved him wrong. He went further, stating he didn’t consider that the papacy had the authority to interpret scripture. The meeting ended in a shouting match and initiated his ultimate excommunication from the Church.

Excommunication

Following the publication of his 95 Theses , Luther continued to lecture and write in Wittenberg. In June and July of 1519 Luther publicly declared that the Bible did not give the pope the exclusive right to interpret scripture, which was a direct attack on the authority of the papacy.

Finally, in 1520, the pope had had enough and on June 15 issued an ultimatum threatening Luther with excommunication.

On December 10, 1520, Luther publicly burned the letter. In January 1521, Luther was officially excommunicated from the Roman Catholic Church.

Diet of Worms

In March 1521, Luther was summoned before the Diet of Worms , a general assembly of secular authorities. Again, Luther refused to recant his statements, demanding he be shown any scripture that would refute his position. There was none.

On May 8, 1521, the council released the Edict of Worms, banning Luther’s writings and declaring him a “convicted heretic.” This made him a condemned and wanted man. Friends helped him hide out at the Wartburg Castle.

While in seclusion, he translated the New Testament into the German language, to give ordinary people the opportunity to read God’s word.

Lutheran Church

Though still under threat of arrest, Luther returned to Wittenberg Castle Church, in Eisenach, in May 1522 to organize a new church, Lutheranism.

He gained many followers, and the Lutheran Church also received considerable support from German princes.

When a peasant revolt began in 1524, Luther denounced the peasants and sided with the rulers, whom he depended on to keep his church growing. Thousands of peasants were killed, but the Lutheran Church grew over the years.

Katharina von Bora

In 1525, Luther married Katharina von Bora, a former nun who had abandoned the convent and taken refuge in Wittenberg.

Born into a noble family that had fallen on hard times, at the age of five Katharina was sent to a convent. She and several other reform-minded nuns decided to escape the rigors of the cloistered life, and after smuggling out a letter pleading for help from the Lutherans, Luther organized a daring plot.

With the help of a fishmonger, Luther had the rebellious nuns hide in herring barrels that were secreted out of the convent after dark - an offense punishable by death. Luther ensured that all the women found employment or marriage prospects, except for the strong-willed Katharina, who refused all suitors except Luther himself.

The scandalous marriage of a disgraced monk to a disgraced nun may have somewhat tarnished the reform movement, but over the next several years, the couple prospered and had six children.

Katharina proved herself a more than a capable wife and ally, as she greatly increased their family's wealth by shrewdly investing in farms, orchards and a brewery. She also converted a former monastery into a dormitory and meeting center for Reformation activists.

Luther later said of his marriage, "I have made the angels laugh and the devils weep." Unusual for its time, Luther in his will entrusted Katharina as his sole inheritor and guardian of their children.

Anti-Semitism

From 1533 to his death in 1546, Luther served as the dean of theology at University of Wittenberg. During this time he suffered from many illnesses, including arthritis, heart problems and digestive disorders.

The physical pain and emotional strain of being a fugitive might have been reflected in his writings.

Some works contained strident and offensive language against several segments of society, particularly Jews and, to a lesser degree, Muslims. Luther's anti-Semitism is on full display in his treatise, The Jews and Their Lies .

Luther died following a stroke on February 18, 1546, at the age of 62 during a trip to his hometown of Eisleben. He was buried in All Saints' Church in Wittenberg, the city he had helped turn into an intellectual center.

Luther's teachings and translations radically changed Christian theology. Thanks in large part to the Gutenberg press, his influence continued to grow after his death, as his message spread across Europe and around the world.

QUICK FACTS

- Name: Luther Martin

- Birth Year: 1483

- Birth date: November 10, 1483

- Birth City: Eisleben

- Birth Country: Germany

- Gender: Male

- Best Known For: Martin Luther was a German monk who forever changed Christianity when he nailed his '95 Theses' to a church door in 1517, sparking the Protestant Reformation.

- Christianity

- Astrological Sign: Scorpio

- Nacionalities

- Interesting Facts

- Martin Luther studied to be a lawyer before deciding to become a monk.

- Luther refused to recant his '95 Theses' and was excommunicated from the Catholic Church.

- Luther married a former nun and they went on to have six children.

- Death Year: 1546

- Death date: February 18, 1546

- Death City: Eisleben

- Death Country: Germany

We strive for accuracy and fairness.If you see something that doesn't look right, contact us !

CITATION INFORMATION

- Article Title: Martin Luther Biography

- Author: Biography.com Editors

- Website Name: The Biography.com website

- Url: https://www.biography.com/religious-figures/martin-luther

- Access Date:

- Publisher: A&E; Television Networks

- Last Updated: September 20, 2019

- Original Published Date: April 2, 2014

- To be a Christian without prayer is no more possible than to be alive without breathing.

- God writes the Gospel not in the Bible alone, but also on trees, and in the flowers and clouds and stars.

- Let the wife make the husband glad to come home, and let him make her sorry to see him leave.

- You are not only responsible for what you say, but also for what you do not say.

Famous Religious Figures

7 Little-Known Facts About Saint Patrick

Saint Nicholas

Jerry Falwell

Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh

Saint Thomas Aquinas

History of the Dalai Lama's Biggest Controversies

Saint Patrick

Pope Benedict XVI

John Calvin

Pontius Pilate

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

This Day In History : October 31

Changing the day will navigate the page to that given day in history. You can navigate days by using left and right arrows

Martin Luther posts 95 theses

On October 31, 1517, legend has it that the priest and scholar Martin Luther approaches the door of the Castle Church in Wittenberg, Germany, and nails a piece of paper to it containing the 95 revolutionary opinions that would begin the Protestant Reformation .

In his theses, Luther condemned the excesses and corruption of the Roman Catholic Church, especially the papal practice of asking payment—called “indulgences”—for the forgiveness of sins. At the time, a Dominican priest named Johann Tetzel, commissioned by the Archbishop of Mainz and Pope Leo X, was in the midst of a major fundraising campaign in Germany to finance the renovation of St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome. Though Prince Frederick III the Wise had banned the sale of indulgences in Wittenberg, many church members traveled to purchase them. When they returned, they showed the pardons they had bought to Luther, claiming they no longer had to repent for their sins.

Luther’s frustration with this practice led him to write the 95 Theses, which were quickly snapped up, translated from Latin into German and distributed widely. A copy made its way to Rome, and efforts began to convince Luther to change his tune. He refused to keep silent, however, and in 1521 Pope Leo X formally excommunicated Luther from the Catholic Church. That same year, Luther again refused to recant his writings before the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V of Germany, who issued the famous Edict of Worms declaring Luther an outlaw and a heretic and giving permission for anyone to kill him without consequence. Protected by Prince Frederick, Luther began working on a German translation of the Bible, a task that took 10 years to complete.

The term “Protestant” first appeared in 1529, when Charles V revoked a provision that allowed the ruler of each German state to choose whether they would enforce the Edict of Worms. A number of princes and other supporters of Luther issued a protest, declaring that their allegiance to God trumped their allegiance to the emperor. They became known to their opponents as Protestants; gradually this name came to apply to all who believed the Church should be reformed, even those outside Germany. By the time Luther died, of natural causes, in 1546, his revolutionary beliefs had formed the basis for the Protestant Reformation, which would over the next three centuries revolutionize Western civilization.

Also on This Day in History October | 31

Freak explosion at Indiana State Fairgrounds Coliseum kills nearly 100

Violet palmer becomes first woman to officiate an nba game, this day in history video: what happened on october 31, stalin’s body removed from lenin’s tomb, celebrated magician harry houdini dies, earl lloyd becomes first black player in the nba.

Wake Up to This Day in History

Sign up now to learn about This Day in History straight from your inbox. Get all of today's events in just one email featuring a range of topics.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

The U.S. Congress admits Nevada as the 36th state

Ed sullivan witnesses beatlemania firsthand, paving the way for the british invasion, actor river phoenix dies, indian prime minister indira gandhi is assassinated, king george iii speaks for first time since american independence declared.

Find anything you save across the site in your account

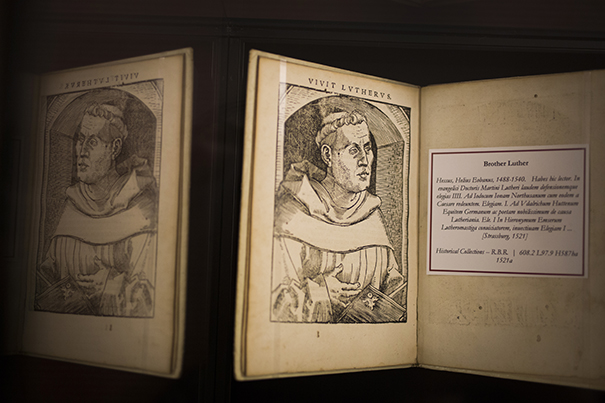

How Martin Luther Changed the World

By Joan Acocella

Clang! Clang! Down the corridors of religious history we hear this sound: Martin Luther, an energetic thirty-three-year-old Augustinian friar, hammering his Ninety-five Theses to the doors of the Castle Church of Wittenberg, in Saxony, and thus, eventually, splitting the thousand-year-old Roman Catholic Church into two churches—one loyal to the Pope in Rome, the other protesting against the Pope’s rule and soon, in fact, calling itself Protestant. This month marks the five-hundredth anniversary of Luther’s famous action. Accordingly, a number of books have come out, reconsidering the man and his influence. They differ on many points, but something that most of them agree on is that the hammering episode, so satisfying symbolically—loud, metallic, violent—never occurred. Not only were there no eyewitnesses; Luther himself, ordinarily an enthusiastic self-dramatizer, was vague on what had happened. He remembered drawing up a list of ninety-five theses around the date in question, but, as for what he did with it, all he was sure of was that he sent it to the local archbishop. Furthermore, the theses were not, as is often imagined, a set of non-negotiable demands about how the Church should reform itself in accordance with Brother Martin’s standards. Rather, like all “theses” in those days, they were points to be thrashed out in public disputations, in the manner of the ecclesiastical scholars of the twelfth century or, for that matter, the debate clubs of tradition-minded universities in our own time.

If the Ninety-five Theses sprouted a myth, that is no surprise. Luther was one of those figures who touched off something much larger than himself; namely, the Reformation—the sundering of the Church and a fundamental revision of its theology. Once he had divided the Church, it could not be healed. His reforms survived to breed other reforms, many of which he disapproved of. His church splintered and splintered. To tote up the Protestant denominations discussed in Alec Ryrie’s new book, “ Protestants ” (Viking), is almost comical, there are so many of them. That means a lot of people, though. An eighth of the human race is now Protestant.

The Reformation, in turn, reshaped Europe. As German-speaking lands asserted their independence from Rome, other forces were unleashed. In the Knights’ Revolt of 1522, and the Peasants’ War, a couple of years later, minor gentry and impoverished agricultural workers saw Protestantism as a way of redressing social grievances. (More than eighty thousand poorly armed peasants were slaughtered when the latter rebellion failed.) Indeed, the horrific Thirty Years’ War, in which, basically, Europe’s Roman Catholics killed all the Protestants they could, and vice versa, can in some measure be laid at Luther’s door. Although it did not begin until decades after his death, it arose in part because he had created no institutional structure to replace the one he walked away from.

Almost as soon as Luther started the Reformation, alternative Reformations arose in other localities. From town to town, preachers told the citizenry what it should no longer put up with, whereupon they stood a good chance of being shoved aside—indeed, strung up—by other preachers. Religious houses began to close down. Luther led the movement mostly by his writings. Meanwhile, he did what he thought was his main job in life, teaching the Bible at the University of Wittenberg. The Reformation wasn’t led, exactly; it just spread, metastasized.

And that was because Europe was so ready for it. The relationship between the people and the rulers could hardly have been worse. Maximilian I, the Holy Roman Emperor, was dying—he brought his coffin with him wherever he travelled—but he was taking his time about it. The presumptive heir, King Charles I of Spain, was looked upon with grave suspicion. He already had Spain and the Netherlands. Why did he need the Holy Roman Empire as well? Furthermore, he was young—only seventeen when Luther wrote the Ninety-five Theses. The biggest trouble, though, was money. The Church had incurred enormous expenses. It was warring with the Turks at the walls of Vienna. It had also started an ambitious building campaign, including the reconstruction of St. Peter’s Basilica, in Rome. To pay for these ventures, it had borrowed huge sums from Europe’s banks, and to repay the banks it was strangling the people with taxes.

It has often been said that, fundamentally, Luther gave us “modernity.” Among the recent studies, Eric Metaxas’s “ Martin Luther: The Man Who Rediscovered God and Changed the World ” (Viking) makes this claim in grandiose terms. “The quintessentially modern idea of the individual was as unthinkable before Luther as is color in a world of black and white,” he writes. “And the more recent ideas of pluralism, religious liberty, self-government, and liberty all entered history through the door that Luther opened.” The other books are more reserved. As they point out, Luther wanted no part of pluralism—even for the time, he was vehemently anti-Semitic—and not much part of individualism. People were to believe and act as their churches dictated.

The fact that Luther’s protest, rather than others that preceded it, brought about the Reformation is probably due in large measure to his outsized personality. He was a charismatic man, and maniacally energetic. Above all, he was intransigent. To oppose was his joy. And though at times he showed that hankering for martyrdom that we detect, with distaste, in the stories of certain religious figures, it seems that, most of the time, he just got out of bed in the morning and got on with his work. Among other things, he translated the New Testament from Greek into German in eleven weeks.

Luther was born in 1483 and grew up in Mansfeld, a small mining town in Saxony. His father started out as a miner but soon rose to become a master smelter, a specialist in separating valuable metal (in this case, copper) from ore. The family was not poor. Archeologists have been at work in their basement. The Luthers ate suckling pig and owned drinking glasses. They had either seven or eight children, of whom five survived. The father wanted Martin, the eldest, to study law, in order to help him in his business, but Martin disliked law school and promptly had one of those experiences often undergone in the old days by young people who did not wish to take their parents’ career advice. Caught in a violent thunderstorm one day in 1505—he was twenty-one—he vowed to St. Anne, the mother of the Virgin Mary, that if he survived he would become a monk. He kept his promise, and was ordained two years later. In the heavily psychoanalytic nineteen-fifties, much was made of the idea that this flouting of his father’s wishes set the stage for his rebellion against the Holy Father in Rome. Such is the main point of Erik Erikson’s 1958 book, “ Young Man Luther ,” which became the basis of a famous play by John Osborne (filmed, in 1974, with Stacy Keach in the title role).

Today, psychoanalytic interpretations tend to be tittered at by Luther biographers. But the desire to find some great psychological source, or even a middle-sized one, for Luther’s great story is understandable, because, for many years, nothing much happened to him. This man who changed the world left his German-speaking lands only once in his life. (In 1510, he was part of a mission sent to Rome to heal a rent in the Augustinian order. It failed.) Most of his youth was spent in dirty little towns where men worked long hours each day and then, at night, went to the tavern and got into fights. He described his university town, Erfurt, as consisting of “a whorehouse and a beerhouse.” Wittenberg, where he lived for the remainder of his life, was bigger—with two thousand inhabitants when he settled there—but not much better. As Lyndal Roper, one of the best of the new biographers, writes, in “ Martin Luther: Renegade and Prophet ” (Random House), it was a mess of “muddy houses, unclean lanes.” At that time, however, the new ruler of Saxony, Frederick the Wise, was trying to make a real city of it. He built a castle and a church—the one on whose door the famous theses were supposedly nailed—and he hired an important artist, Lucas Cranach the Elder, as his court painter. Most important, he founded a university, and staffed it with able scholars, including Johann von Staupitz, the vicar-general of the Augustinian friars of the German-speaking territories. Staupitz had been Luther’s confessor at Erfurt, and when he found himself overworked at Wittenberg he summoned Luther, persuaded him to take a doctorate, and handed over many of his duties to him. Luther supervised everything from monasteries (eleven of them) to fish ponds, but most crucial was his succeeding Staupitz as the university’s professor of the Bible, a job that he took on at the age of twenty-eight and retained until his death. In this capacity, he lectured on Scripture, held disputations, and preached to the staff of the university.

He was apparently a galvanizing speaker, but during his first twelve years as a monk he published almost nothing. This was no doubt due in part to the responsibilities heaped on him at Wittenberg, but at this time, and for a long time, he also suffered what seems to have been a severe psychospiritual crisis. He called his problem his Anfechtungen —trials, tribulations—but this feels too slight a word to cover the afflictions he describes: cold sweats, nausea, constipation, crushing headaches, ringing in his ears, together with depression, anxiety, and a general feeling that, as he put it, the angel of Satan was beating him with his fists. Most painful, it seems, for this passionately religious young man was to discover his anger against God. Years later, commenting on his reading of Scripture as a young friar, Luther spoke of his rage at the description of God’s righteousness, and of his grief that, as he was certain, he would not be judged worthy: “I did not love, yes, I hated the righteous God who punishes sinners.”

There were good reasons for an intense young priest to feel disillusioned. One of the most bitterly resented abuses of the Church at that time was the so-called indulgences, a kind of late-medieval get-out-of-jail-free card used by the Church to make money. When a Christian purchased an indulgence from the Church, he obtained—for himself or whomever else he was trying to benefit—a reduction in the amount of time the person’s soul had to spend in Purgatory, atoning for his sins, before ascending to Heaven. You might pay to have a special Mass said for the sinner or, less expensively, you could buy candles or new altar cloths for the church. But, in the most common transaction, the purchaser simply paid an agreed-upon amount of money and, in return, was given a document saying that the beneficiary—the name was written in on a printed form—was forgiven x amount of time in Purgatory. The more time off, the more it cost, but the indulgence-sellers promised that whatever you paid for you got.