An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- J Community Hosp Intern Med Perspect

- v.7(1); 2017 Jan

The role of medical education in the development of the scientific practice of medicine

Lucien cardinal.

a Department of Internal Medicine , Stony Brook University School of Medicine , New York, NY, USA

b John T. Mather Memorial Hospital , Port Jefferson, NY, USA

The authors describe the important role of medical schools and graduate medical education programs (residencies) in relationship to the advances in Medicine witnessed during the twentieth century; diagnosis, prognosis and treatment were revolutionized. This historical essay details the evolution of the education system and the successful struggle to introduce a uniform, science-based curriculum and bedside education. The result was successive generations of soundly educated physicians prepared with a broad knowledge in science, an understanding of laboratory methods and the ability to practice medicine at the bedside. These changes in medical education created a foundation for the advancement of medicine.

During the last 150 years tremendous advances have taken place in the field of medical education. The product of these changes has been the development of physicians who have become progressively scientific in their mode of thought and practice over time. These physicians have been increasingly at the forefront of medicine, incorporating advances in every scientific field into the delivery of healthcare. A systematic and structured educational curriculum was created; this allowed the medical profession to train, through its educational institutions, physicians with the knowledge, skills and attitudes necessary for the scientific practice of medicine. Physicians were graduated with the capacity to study scientific advances, to interpret these advances relative to medicine and to incorporate pertinent elements into their medical practice. The practice of medicine today, contrasted with a century ago, has undergone a metamorphosis that could not have been predicted by the typical American medical graduate of 1900. Medicine has moved from a field based on dogma to one based on fact derived through scientific investigation and clinical observation.

Prior to the twentieth century there existed a plethora of theories explaining health and disease, each one of which conflicted with the other. After 1900 scientific medicine began to be practiced on the wards of several prestigious institutions, yet sectarianism and dogmatism continued to assert itself in the offices of the general practitioner for at least another 30 years, represented by such teachings as homeopathy, naturopathy, eclecticism and abramsism.[ 1 ] Each dogma proposed foundational principles of practice, closed to modification based on observation. There were 22 US homeopathic medical colleges in 1900; Boston University School of Medicine, Hahnemann School of Medicine in Philadelphia (now Drexel), and the New York Homeopathic Medical College (now the New York Medical College) are three examples of schools that were founded on homeopathic principles, later to continue successfully as scientifically based institutions.[ 2 ]

By the dawn of the twentieth century scientific thought and scientific medicine had taken deep root in Germany. However, in the USA the average physician still practiced medicine based largely on the fallacious dogmatic ipse dixits of the particular theory of human health and disease to which the physician subscribed. Most medical school curricula did not include or support the scientific method or attempt to bolster their teachings with the results of experimentation. The unthinking acceptance of dogma was immortalized in William Cowper’s poem, The Task.

Books are oft times talismans and spells , 1 By which the magic art of shrewder wits Holds an unthinking multitude enthrall’d. [ 3 ]

As early as the middle of the nineteenth century, a group of progressive medical leaders began to emerge in the USA. They recognized the need for advancement and advocated for political initiatives. In 1846 the Medical Society of the State of New York called for a national medical organization to be formed, stating that it ‘would be conducive to the elevation of the standard of medical education in the United States.’(p. 4). [ 4 ] This organization was founded as the American Medical Association (AMA) in the following year. Its constitution stated the following as central to its purpose: ‘cultivating and advancing medical knowledge’ and ‘elevating the standard of medical education.’ (p. 2). [ 5 ] Change did not come quickly over the next 50 years, so that in 1902 Dr John Wyeth, president of the AMA, astutely appointed a Committee on Medical Education. The following year, that committee restated under the ‘First Objective of the AMA’ that the organization was ‘formed for the purpose of elevating the standard of medical education.’[4] Sir William Osler, often referred to as the father of Internal Medicine, heralded the changes to come when he stated ‘A new school of practitioners has arisen … It seeks to study, rationally and scientifically …’ the practice of medicine.[ 6 ]

In the early years (1850–1900) medical schools in America, with a few exceptions, stood independent from universities and were proprietary in nature. These two factors tended to isolate the field of medicine from the other sciences. The most advanced medical schools were abroad and were part of established universities. German universities, with centers of learning in Vienna and Berlin, were held in high regard. American physicians frequently traveled to Germany, France and England to advance their post-graduate medical education. On returning home they emulated the practices of institutions they encountered abroad.[ 7 ] Henry P. Bowditch studied in Leipzig and was influenced by the physiological laboratory of Carl Ludwig. He subsequently developed the Institute for Experimental Medicine at Harvard, the first laboratory of its kind in the USA. Similarly, William Henry Welch studied with Ludwig and later went on to become the dean of the Johns Hopkins Medical School and one of the founding physicians of its hospital. He wrote ‘I hope that the Johns Hopkins … will be able to introduce German methods.’[ 8 ] In the early 1900s US physicians were handicapped because the leading medical journals were overwhelmingly in German and not available in the western hemisphere. Several quality US journals were founded in the 1800s and early 1900s to disseminate the findings of medical research. The American Journal of Medical Sciences, a well-respected journal in the USA and Europe, was established by Dr Isaac Hays in 1827. Hays is also credited with the preparation of the Code of Ethics of the AMA. The Journal of the American Medical Association was founded in 1883,[ 9 ] and in 1908 Heinrich Stern founded the Archives of Diagnosis, a leading medical journal of its time.[ 10 ] After attending a conference of the Royal College of Physicians in London in 1913, Stern returned intent on establishing a similar organization. He subsequently founded the American College of Physicians with the intent that it would foster the exchange of scientific information between physicians.[ 11 ]

Standards for admission to an American medical school were lax; a high school diploma was finally mandated in 1905.[ 4 ] New York, through the Department of Education, was one of the few states to require a high school diploma as a prerequisite for medical school admission. Harvard did not require a baccalaureate as a prerequisite until 1901.[ 12 ] Medical schools by and large were two-year programs devoted to bookwork with little exposure to patients at the bedside. The student had little personal contact with the professor, and education was often restricted to lectures heard in an educational amphitheater. Patients were sometimes wheeled in to demonstrate some aspect of medicine to the student.

In 1910, the Carnegie Foundation released a bulletin on medical education in the USA, authored by Abraham Flexner. It became known as the Flexner Report and was regarded as an accurate description of the low standards in medical education at the time. Advocates for the advancement of medical education used it to encourage change. Flexner detailed, over 346 pages, the lack of a systematic and unified approach to medical education, the absence of suitable premedical education and minimal patient-based learning. He also described the factors responsible for the situation and made suggestions for corrective action. Interestingly, Flexner singled out the specialty of Internal Medicine for praise, describing it as the backbone of clinical teaching. He went on to cite another author, quoting ‘… Internal Medicine is regarded as the mother of all other clinical divisions.’[ 13 ]

Over the subsequent 30 years the educational landscape slowly began to succumb to the forces of change. Medical schools defined required premedical coursework, extended the duration of study to four years and incorporated a science-based curriculum.[ 12 , 14 ] They affiliated with universities and teaching hospitals, creating clinical clerkships during the last two years of medical school, allowing students patient-based experiences at the bedside.[ 15 ] Schools that could not accommodate these changes were closed.

Additionally, and importantly, after medical school physicians began to commit themselves to additional specialized educational training by attending hospital-based residencies. Widespread adoption of half-year or single-year internships came quickly, but longer programs of organized training were uncommon. The Johns Hopkins Hospital was established along the lines of the German medical clinics, incorporating full-time professors (‘full-time system’), bedside teaching, clinical observation and laboratory science.[ 16 ] It also incorporated organized multi-year training. It opened its doors on 6 May 1889 and on 15 May admitted its first patient, a case of aortic aneurysm. This was the first patient to receive hospital-based care directly by graduate trainees who were part of an organized multi-year residency program.[ 17 ] Trainees were encouraged to evaluate the impact of treatment and effectiveness of diagnostic tests directly at the bedside. Such proof of action is one aspect of the scientific method. No longer would treatment and diagnosis be based solely on theory. Thus, graduate medical education (GME) was born. Osler, Professor of Medicine at Johns Hopkins, felt that his role in the development of GME was his most important contribution to medicine.[ 18 ] Despite this early development of a modern residency program at Johns Hopkins, medical educators in the USA did not rapidly establish many other multi-year residencies. This is primarily thought to be due to their focused efforts initially to establish rigorous and reputable medical schools, and later the interruptions of World Wars I and II. In lieu of a residency in a medical specialty a physician could attend a condensed course at a so-called post-graduate medical college. These courses were often only weeks in duration. In 1914 there were 17 post-graduate medical schools in the USA, five each in New York and Illinois.[ 19 ] In 1934 the state of Pennsylvania still had only five residency programs of three years or more in length registered with the AMA’s Council on Graduate Medical Education.[ 14 ] Multi-year residency programs preparing physicians for specialization were widely disseminated during the 10 years following the close of World War II.

The advances in medical education and the establishment of graduate medical education stand out as the most important developments in medicine in the last 150 years. They led to the graduation of successive generations of competent physicians, grounded in the scientific practice of medicine. Their openness to discoveries in all fields of science has allowed, with each passing year, for the expansion of medicine to ever-broader horizons.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

- Search Menu

- Advance articles

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access

- Why Publish with JHMAS?

- About Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Terms and Conditions

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

Organization and outline of essays, remaking the case for history in medical education.

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Jacob Steere-Williams, Justin Barr, Claire D Clark, Raúl Necochea López, Remaking the Case for History in Medical Education, Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences , Volume 78, Issue 1, January 2023, Pages 1–8, https://doi.org/10.1093/jhmas/jrac049

- Permissions Icon Permissions

In a 2015 essay titled “Making the Case for History in Medical Education” in the Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences, David Jones, Jeremy Greene, Jacalyn Duffin, and John Harley Warner issued a challenge for historians of medicine. “In a world where many interests make demands for curriculum time and attention,” they argued, “historians of medicine need a more aggressive strategy.” 1 The article has since been one of the most frequently cited in the history of medicine. It was also a sign of the times. The authors pointed to repeated and ongoing efforts of clinicians and historians to integrate medical history into medical schools. They surveyed the wide range of arguments historians have made over the decades: how history buttresses a sense of professional identity, fosters holistic examinations of disease, and cautions against misguided practice.

But as our colleagues lamented in 2015, these potent rationales for medical history have not been altogether convincing enough to effect meaningful curricular change in medical education. Medical school administrators decry a lack of time in the curriculum for medical history, other disciplines fiercely compete for resources across medical schools, and historians sometimes struggle to translate the field in meaningful ways to medical students.

Many of these concerns, of course, are not new. In the first issue of this journal in 1946, George Rosen wrote the landmark essay, “What Is Past, Is Prologue,” lamenting that for seventy-five years the medical profession had “turned away from the history of medicine.” 2 Rosen identified two reasons: structural changes in medical education resulting from the specialization of American medicine in the early twentieth century; and, the failure of historians of medicine to make “medical history the living, dynamic thing that,” in his words, “we believe it to be.” “We do not want to cultivate medical history as a mere search for antiquities,” he concluded, “but rather as a vital, integral part of medicine.” 3

In their 2015 essay Jones et al. were re-stating a claim made by historians of medicine from the middle decades of the twentieth century, that medical history is an essential part of medical practice. As Rosen, Henry Sigerist, and Erwin Ackerknecht had argued seventy years prior, Jones et al. warned against the idea of a history of medicine that simply studies health and healing in the past for its own sake. Instead, they argued, medical history must be understood, communicated, and taught, as an “essential component of medical knowledge, reasoning, and practice.” Critically couching their case in this way, within the contemporary lexicon of competencies and entrustable professional activities, our colleagues in 2015 argued that medical history might be reframed as contributing to medical education in the same way anatomy, biochemistry, or pathophysiology do. 4 Seeing the striking similarities between Rosen in 1946 and Jones et al. in 2015, despite the vast changes in medical education in that time span, begs for a serious and ongoing reflection about the ways in which we communicate the value of the history of medicine to diverse public and professional audiences.

To the immense benefit of the field, Jones et al. in 2015 went beyond praising the virtues of the history of medicine to offer strategic resources for historians. They listed over a dozen distinct ways that history can directly contribute to medical education, including elucidating the social factors that shape health and illness, unpacking the cultural construction of disease categories, and addressing the imbalances of power, race, and gender in clinical care. Our colleagues implored historians of medicine to face curricular change in medical schools in creative ways that align with dominant approaches in medical education.

Competency-Based Medical Education (CBME) is the most important approach to clinical pedagogy in the US and Canada. Billed by the American Association of Medical Colleges (AAMC) since the late 1990s as a way to address the evolving needs of the health care system, CBME now establishes what observable abilities medical learners must display to be deemed competent clinicians. Given the ubiquity of the language of competencies, Jones et al. offered pragmatic advice to make the case for history of medicine in those terms. Their advice has aged well, though some qualifications are worth mentioning based on experiences of the last few years. CBME, while still the dominant approach to assessment in the US and Canada, has been criticized on empirical and theoretical grounds. 5 As with other educational activities, it is not simple to demonstrate direct causal links between historical learning and better doctoring. It behooves us, therefore, to support research that evaluates our contributions to the education of clinicians, and not only to assert our convictions regarding what we bring to the competencies table. In addition, two decades into the competencies regime, historians are no longer naive about the weight of educational leadership positions within our institutions. Curriculum reform leaders have privileged perches from which to identify insufficient pedagogical content, faculty development lacunae, and assessment needs that historical knowledge and methods can fulfill, particularly when it comes to areas such as systems-based practice and medical knowledge. There is no reason why historians should shy away from seeking these responsibilities. Furthermore, the cyclical nature of reviews by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) suggests that promoting change may be especially welcome in the period leading up to these institutional visits, and necessary in the period immediately following them. Our competency-driven environments, in other words, call for vigorous new engagement with developments such as competency-based evaluations, health curricular reform, and institutional accreditations.

Of all the trends in competency-based education in the last decade or so, perhaps the one that has resonated most powerfully with historians is the movement toward “structural competency.” In an article published in 2014, Jonathan Metzl and Helena Hansen used the language of competencies to “argue that increasing recognition of the ways in which social and economic forces produce symptoms or methylate genes then needs to be better coupled with medical models for structural change.” 6 Since then, historians and social scientists have leveraged the framework of structural competency to make the case that some medical knowledge is structurally racist and that understanding the racist history of the production of medical knowledge is integral to anti-racist curriculum reform efforts. 7 Historians have been among the leading educators in anti-racist curriculum reform efforts by, for example, curating academically rigorous reading lists, embarking on oral history projects, and elucidating the ways in which history can and must be used to make sense of structural violence in medicine. 8

This Special Issue builds upon this critical foundation. Acknowledging Rosen’s charge in 1946, we also recognize the longer historical arc of generative conversations, in this journal and in the broader field, about the value and the struggle of teaching medical history in medical schools. Rather than retelling this complex history or reframing the nature of the debates at hand, this Special Issue has more modest aims. What you will find in the essays that follow is a medical historian’s toolbox, a survey of interesting and innovative practical examples of how a small sampling of colleagues across the world are pushing the boundaries for the integration of the history of medicine within clinical education. This Special Issue provides examples of successful initiatives and the logistical details of how to implement them at organizational and pedagogical levels, thus creating models for others to emulate. Spanning a range of creative ideas, collaborations, and institutions, the breadth of the essays in this issue of JHMAS promises something for historians of medicine in various institutional settings, in the hope of generating ongoing developments of Clio in the Clinic. 9

In providing a set of instructive examples, readers will notice two features in this collection of essays. First, we argue that sustainable change requires thinking about medical education and medical history at both local and global levels. To address the structural and ideological problems of integrating the history of medicine into medical education in fundamental ways, we must acknowledge local contexts as critical, but we also need to push beyond the idea that curricular change or administrator buy-in are uniquely North American phenomena. Our students, many of whom seek out clinical experiences outside the US and Canada, provide us with another reason why understanding global learning conditions and tensions is a worthwhile endeavor. The examples assembled in this Special Issue are thus global in scope. Second, we propose that the boundaries of clinical education must encompass more than just medical schools. Indeed, the essays in this Special Issue demonstrate the ways that an ontologically essential view of medical history can be incorporated for health professionals and aspiring health professionals at all levels. Broadening the spectrum of who we traditionally view as the learners of medical history expands the opportunities to teach the history of medicine and imbed the field into multiple audiences of clinical education and practice.

This Special Issue offers no radical rethinking of the value of medical history in medical education. We are, however, acutely aware of the ongoing evolution of medical education, and of the broader social and political climate of 2022 that marks a stark change from 2015 when the journal last visited this topic. While already a trend a decade ago, in recent years we have seen the dramatic rise of medical and health humanities courses, programs, and centers in undergraduate institutions and medical schools. 10 Many medical schools now feature programs or centers in health or medical humanities, and several prominent scholars have even argued that the medical and health humanities may “save the life” of imperiled humanities disciplines. 11 The 2015 “Making the Case” essay that has been so central to our thinking for this Special Issue suggested that historians of medicine should be cautious in approaching the medical humanities, and to differentiate our theories, methods, and values from the broader trend towards medical and health humanities. Drawing on our own experiences in recent years, perhaps we need to rethink how to distinguish medical history from other humanities and social sciences in medical education.

Those of us who spend most of our teaching careers among budding physicians, nurses, pharmacists, and dentists can attest to the great value students derive from multi-focal analyses of health problems, from historical, ethical, and policy perspectives, among others. Furthermore, a number of departments in medical schools are de jure and de facto homes to a variety of different humanities specialists who enrich each other’s styles and toolboxes. New scholarly resources have emerged that deliberately and effectively cater to these educators since 2015, such as the New England Journal of Medicine ’s “Case Studies in Social Medicine.” 12 Asserting the value of historians’ theories and methods in these ecosystems is less of a priority than sustaining teaching environments in which the humanities can flourish amidst students’ ever-present concern to focus on intense pathophysiology studying in the first years, and on managing clinical rotation schedules in later years. Integrating our scholarly and teaching styles with those of other humanities and social science experts in narrative medicine, anthropology, philosophy, and ethics, for example, 13 and with those of supportive clinicians is not a pragmatic show of public comity but a necessity that flows from the collaborative spirit that animates the practice of modern medicine. 14 Working alongside fellow travelers can and does buttress historians’ influence on clinical curricula. Can we be effective medical educators while asserting our disciplinary independence, and even a privileged spot for history in clinical education? Possibly. But we might gain as much by collaborating with our fellow humanists and cultivating intellectual humility on an everyday basis while turning to our medical history conferences, large and small, for professional nourishment and renewed commitment to the vitality of our field.

In addition to the complexity of positioning history vis-a-vis other humanities disciplines in clinical education, another, more urgent development intervened between 2015 and the present. The devastating and ongoing COVID-19 pandemic has brought problems of health care access, vaccine equity and ethics, structural racism, xenophobia, and the social context of health to the center of public debate in unprecedented ways on a worldwide scale. Because these topics have long been central to the social and cultural history of medicine and public health, historians in our field have been at the forefront of engaging in public scholarship through op-eds, podcasts, public history and oral history projects, essays, and interviews, and also in working with local, regional, and international political groups to inform public policy. 15 We remain inspired by our colleagues across the world who have been engaged in and supported this work during a global emergency. And COVID-19 has not been the only crisis we have responded to of late, with historians of medicine relentlessly offering context to understand the US Supreme Court overturning of the right to abortion and the emerging stigma around monkeypox, for example. 16 All these efforts build on a tradition of prolific public conversations led by historians about the relevance of the past to act on contemporary health predicaments, whether they concern the HIV/AIDS epidemic, sexual and reproductive rights, drug policies, or even medical education itself. 17 In the short term, it will be difficult, and even undesirable, for these conversations to elide elements and concepts the COVID-19 pandemic has made central, including the erosion of biomedical authority and the socially inequitable burden of disease across populations and nations. Closer to our readers in the US and Canada, the centrality of intersectional and antiracist approaches in medical history means that now, perhaps more so than 1946 or 2015, we have a renewed opportunity to address publics who demand to understand whether and why present-day conditions resemble past ones. Yet, the challenge for our field is how to translate this moment into structural change, at our universities, in our communities, and particularly for the purposes of this Special Issue, in medical education? How can we make medical history instrumental in medical education—and, let us not forget, in public policy—without turning the field into an overly simple tool? 18

The essays that follow offer an institutional, intellectual, and geographical breadth of perspectives on innovative ways to integrate the history of medicine into medical education. Readers will find examples from North America, Europe, the Middle East, and East Asia, and authors as diverse as physicians, surgeons, librarians, archivists, and professional historians of medicine. Taken together, these essays offer an exciting range of ways to introduce, re-introduce, and re-re-introduce history into medical curricula. Readers will undoubtedly find struggles in the essays that follow similar to their own: constrained curricular time in medical education, limited interest by students or administrators, and the tendency of some learners to prefer heroic versions of the history of medicine. No single effort documented in these essays seems to have succeeded in hurdling these obstacles, as they remain common across our field in deeply global ways. Collectively, however, the essays offer a set of potentialities, a diverse toolbox, to introduce and integrate history into clinical practice. While we cannot aspire to comprehensively sample the exemplary local efforts of historians of medicine, public health, nursing, and pharmacy, we hope readers will find inspiration and perhaps a blueprint to continue this vital conversation integral to the history of medicine. 19

The Special Issue begins with an important contextual essay by health sciences librarians Kristine Alpi, Jordan Johnson, and Meg Langford. Their paper surveys the non-curricular history of medicine activities at thirty leading medical schools in the US. Alpi et al. identify a wide range of ways that scholars are currently incorporating the history of medicine in medical education outside of required coursework. These examples include medical history clubs and societies, lecture series, book clubs, funded awards, and local or regional publications. Alpi and colleagues rightly note the importance of these societies in fostering and maintaining a vocational interest in the field. The essay provides a current snapshot of broader trends in the history of medicine in medical education. The perspective of the authors as health sciences librarians underscores a point historians of medicine have long made: librarians and archivists play critical roles in fostering the history of medicine.

Essays two and three turn to specific pedagogical examples of innovative teaching in medical schools. Susan Lamb, in “History’s Toolbox,” first introduces a single skill-based classroom exercise that she uses at the University of Ottawa, a three-hour session directed at fourth-year medical students. Lamb demonstrates the value of teaching medical students historical thinking, not simply historical content, in order to inform clinical decision making. Using a metaphor from bacteriology, histological stains, Lamb instructs students to analyze a historical problem (often an epidemic) through a range of cultural, social, economic, political, and other lenses. In so doing, she provides students the skills to understand the complexities of contemporary problems such as the social determinants of health. Building off her twenty years of experience teaching medical students, Carla Keirns in essay three, “History of Health Policy: Explaining Complexity Through Time,” provides a suggested curriculum for teaching the history of health policy. Keirns shows students how the bewildering, bureaucratic morass that is the US health care system flabbergasts patients and providers alike. Keirns provides detailed teaching strategies for how to historicize critical themes in health policy today – medical training and licensing, nursing education, payment plans – as historically contingent problems, thus fostering the idea that historical thinking is fundamental to clinical care and health policy. In an innovative example that crystallizes her teaching philosophy, Keirns proposes that educators have learners explore the local history of medical schools, clinics, and neighborhoods in order to understand the broader patterns and struggles of American health care reform.

Staying in the institutional context of medical school education but shifting our gaze outside of North America, Alan Weber in essay four, “Clinical Applications of the History of Medicine in Muslim-Majority Nations,” starts with a survey how the history of medicine has been taught in Muslim majority countries. Weber then describes the cultural obstacles of teaching in this setting, particularly the way in which Muslim medical students tend to valorize the past, and how Muslim students, doctors, and patients accept a hybrid worldview that incorporates tenets from western medicine blended with traditional Islamic beliefs about disease, health, and the body. Weber demonstrates unique pedagogical strategies for Muslim nations, including exercises in narrative medicine, cross-cultural clinical competency, and notions of professional identity through the examination of historical medical oaths. In reviewing this expansive topic, Weber not only summarizes key events but also authenticates just how relevant historical knowledge is in the modern Middle-East where many patients combine western biomedicine with traditional understandings of disease. He also conveniently provides a syllabus and long list of sources for non-experts to utilize.

Essay five, by Justin Barr, Rachel Ingold, and Jeff Baker, argues that we need to rethink how, when, and to whom we teach medical history in medical schools. Their article “History of Medicine in Clerkships,” makes two significant points: that historical education can be effectively incorporated during clinical clerkships, and that learners best grasp historical thinking through artifacts in collaboration with librarians and archivists. The authors describe specific lesson plans for surgery, obstetrics/gynecology, and pediatrics, and show how to integrate ancient texts, primary sources, and material relics into instruction. The essay also includes an appendix of digital resources for educators if their institutions’ collections are less accessible or robust. Importantly, the flexibility inherent in clerkship schedules negates many of the traditional obstacles to curricular investment in historical training earlier in medical education.

Artifacts are central too in Harry Wu and Sampson Wong’s article “Spatial Relevance,” in essay six, which centers on experiential learning workshops at the Hong Kong Museum of Medical Sciences and associated heritage trail. A formal part of the curriculum for all first-year medical students since 2010, this three-hour session utilizes specially trained physicians as instructors, and historical analysis from medical historians. Wu and Wong argue that the shared medical backgrounds of teacher and pupil increased the acceptability and efficacy of the exercise, and that “who” teaches the history of medicine in clinical settings is an ongoing question that requires more research. Wu and Wong discuss in detail a specific exhibit that compares the Third Plague Pandemic with the outbreak of SARS in 2002 and show how historical training can help nuance the linearity and notions of progress that might constrain incorporating historical thinking into medical education.

Essay seven, by Frank Stahnisch, returns to North America in a wide-ranging historical study of the last fifty years of medical history education, outreach, and programming at the History of Medicine and Health Care Program in Calgary. Titled “Making Medical History Relevant to Medical Students,” it provides an important case study of the pitfalls, the successes, and the future of teaching history in medical schools. Stahnisch argues that central to this project is providing the support and infrastructure to ensure that learners engage in original historical research and present their findings to multiple audiences. In other words, he argues that medical history is not simply a topic students should learn, but that they must actively do. The essay concludes that fostering student interest in medical history requires an active local medical history society and outreach with physician-historians and community members. Embracing an experiential model of learning, Stahnisch shows how getting students invested in medical history will further clinical problem solving in the future, particularly around problems of health care access, the social contingency of disease concepts, and socio-economic dependencies of medical decision-making.

Essays eight and nine turn away from the institutional setting of medical schools to consider a wider range of ways that historical thinking can inform clinical practice. In essay eight, “Clio in the Operating Theatre,” Agnes Arnold-Forster employs theories and techniques from the history of emotions to rethink surgical stereotypes of emotionally detached, dispassionate surgeons. Explaining a series of Wellcome-funded workshops and small-group discussions with historians and practicing surgeons, Arnold-Forster provides a powerful, novel model of cross-disciplinary research. While surgical stereotypes of dispassion still predominate, Arnold-Forster shows that providing surgeons an alternative history where the emotions of doctors and patients takes center stage in the clinical encounter opens up a new way for surgeons today to embrace emotions into their practice. Building off of Arnold-Forster’s rethinking of surgery, Justin Barr, Don Nakayama, Meghan Kennedy, and Theodore Pappas describe in essay nine the broader institutional settings of incorporating historical thinking into the surgical profession. Activities within the American College of Surgeons, they argue, capture historical interest at all levels of the profession from student to senior clinician. The authors articulate a step-by-step guide for implementing various initiatives including poster contests, panel presentations, and an active blog.

The final essay in this collection, by Tequila Manning, Walter Ingram, and Christopher Crenner, concludes with a powerful example that broadens the history of medicine into the community. Drawing on the work of public history and memory studies, the authors explore a project at Kansas University Medical Center to rename one of its colleges after an influential former dean who intentionally propagated racist and segregationist practices against African-American students. The authors show how historical research in uncovering and documenting this history was critical, but so too was a local exhibit and a series of public discussions. The result was the renaming of the college in 2017 after Marjorie Cates, the first African-American female student to graduate from the school. This contribution demonstrates the power of the history of medicine beyond teaching medical students in the classroom, the clerkship, or in local museums. Our colleagues provide a powerful end to the Special Issue, showing how medical history can converge with an activist pursuit, one at the center of racial justice, commemoration, and the public understanding of medical education.

The collection of essays in this Special Issue offers no final words on how to integrate the history of medicine into medical education. They form, however, a series of innovative case studies for historians around the world to use in their own local settings, enacting, in their own way, the “aggressive strategy” Jones et al. invoked in 2015, but also highlighting the pedagogical partnerships the Special Issue contributors have built and their efforts to persuade students to see history as a tool to provide better and fairer care.

David S. Jones, Jeremy A. Greene, Jacalyn Duffin, and John Harley Warner, “Making the Case for History in Medical Education,” Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences 70:4 (2015), 623-652, 625.

George Rosen, “What Is Past, Is Prologue,” Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences, 1:1 (January 1946), 3-5.

Rosen, “What is Past Is Prologue,” 4.

Jones, Greene, Duffin and Warner, “Making the Case for History in Medical Education,” 639.

Ryan Brydges, Victoria A. Boyd, Walter Tavares, Shiphra Ginsburg, Ayelet Kuper, Melanie Anderson, Lynfa Stroud, “Assumptions About Competency-Based Education and the State of the Underlying Evidence: A Critical Narrative Review” Academic Medicine 96, no.2 (2022), 296-306.

Jonathan M. Metzl and Helena Hansen “Structural Competency: Theorizing a New Medical Engagement With Stigma and Inequality” Social Science & Medicine 103 (2014), 126.

Jonathan M. Metzl and Dorothy E. Roberts, “Structural Competency Meets Structural Racism: Race, Politics, and the Structure of Medical Knowledge,” AMA Journal of Ethics, 16: 9 (2014), 674-690. For more information on recent anti-racist curriculum efforts in medicine, see AAMC Statement on Dismantling Racism in Academic Medicine, February 23, 2021: https://www.aamc.org/news-insights/press-releases/aamc-statement-dismantling-racism-academic-medicine

See, for example, Essay Ten in this Special Issue. For broader context, see, Antoine S. Johnson, Elise A. Mitchell, and Ayah Nuriddin, “Syllabus: A History of Anti-Black Racism in Medicine,” Black Perspectives, August 12, 2020, https://www.aaihs.org/syllabus-a-history-of-anti-black-racism-in-medicine/; Raúl Necochea López, Jeffrey Baker, Jason Glenn, Aimee Medeiros, Dominique Tobbell, Ren Capucao, “Race Relations at Academic Health Centers: Historical Scholarship to Enrich Teaching and Community Engagement” Presentation at the 95th annual meeting of the American Association for the History of Medicine, Saratoga Springs, NY, April 22, 2022; Ayah Nuriddin, Graham Mooney, Alexandre IR White, “Reckoning with Histories of Medical Racism and Violence in the USA” The Lancet 396 (10256), 949-951.

Jacalyn Duffin, Clio in the Clinic: History in Medical Education (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2005).

In 2000 there were only 14 medical or health humanities baccalaureate programs in the US and Canada. By 2015 there were approximately 60, and today there are over 120. See, Erin Gentry Lamb, Sarah L. Berry, and Therese Jones, Health Humanities Baccalaureate Programs in the United States and Canada (Case Western Reserve School of Medicine, 2021): https://case.edu/medicine/bioethics/sites/case.edu.bioethics/files/2021-05/Health%20Humanities%20Report%202021.pdf

See, for example, the Health and Humanities Lab at the University of North Carolina, https://hhive.unc.edu ; Craig Klugman, “How Medical Humanities Will Save the Life of the Humanities,” Journal of Medical Humanities, 38: 4 (2017),419-430; Keith Wailoo, “Patients Are Humans Too: The Emergence of Medical Humanities,” Daedalus, 151:3 (2022): 194-20.

Scott D. Stonington, Seth M. Holmes, Helena Hansen, Jeremy A. Greene, Keith A. Wailoo, Debra Malina, Stephen Morrissey, Paul E. Farmer, Michael G. Marmot, “Case Studies in Social Medicine - Attending to Structural Forces in Clinical Practice,” New England Journal of Medicine, 370:20 (2018), 1959-1961.

Madeleine Noelle Olding, et al., “Black, White, and Gray: Student Perspectives on Medical Humanities and Medical Education,” Teaching and Learning in Medicine, Vol.34, Issue 2 (2022), 223-233.

Lisa Howley, Elizabeth Gaufberg, and Brandy King, The Fundamental Role of the Arts and Humanities in Medical Education (Washington DC: AAMC, 2020); American Association of Medical Colleges, Behavioral and Social Science Foundations for Future Physicians (Washington, DC: AAMC, 2011).

See, for example, the American Historical Association’s “Bibliography of Historians’ Responses to COVID-19: https://www.historians.org/news-and-advocacy/everything-has-a-history/a-bibliography-of-historians-responses-to-covid-19 . These efforts are both ongoing and global, see for instance, Jorge Lossio and Mariana Cruz, ¿Qué Hicimos Mal? La Tragedia de la COVID (Lima: IEP, 2022).

Leslie J. Reagan “What Alito Gets Wrong about the History of Abortion in America,” Politico, June 2, 2022, https://www.politico.com/news/magazine/2022/06/02/alitos-anti-roe-argument-wrong-00036174 ; Jim Downs, “Gay Men Need a Specific Warning About Monkeypox,” The Atlantic, May 28, 2022, https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2022/05/monkeypox-outbreak-spread-gay-bisexual-men/643122/

Shane Doyle, Before HIV: Sexuality, Fertility, and Mortality in East Africa, 1900-1980 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013); Dan Royles, To Make the Wounded Whole: The African American Struggle against HIV/AIDS (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2020); Raúl Necochea López, A History of Family Planning in Twentieth Century Peru (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2014); Johanna Schoen, Abortion after Roe (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2015); Claire D. Clark, The Recovery Revolution: The Battle over Addiction Treatment in the United States (New York: Columbia University Press, 2017); David Herzberg, White Market Drugs: Big Pharma and the Hidden History of Addiction in America (University of Chicago Press, 2020); Christopher D.E. Willoughby, Masters of Health: Racial Science and Slavery in U.S. Medical Schools (University of North Carolina Press, 2021).

Simon Szreter, “History, Policy, and the Social History of Medicine,” Social History of Medicine, 22:2 (August 2009), 235-244.

For example, see Macey Flood’s recent call to integrate Indigenous history into medical education, Macey Flood, “Indigenous History in Health Education,” Medical Humanities (2022), 10.1136/medhum-2022-012400.

Email alerts

Citing articles via.

- Recommend to your Library

- Journals Career Network

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1468-4373

- Print ISSN 0022-5045

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

What Is Competency-Based Medical Education?

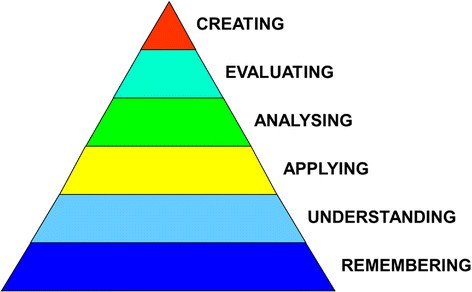

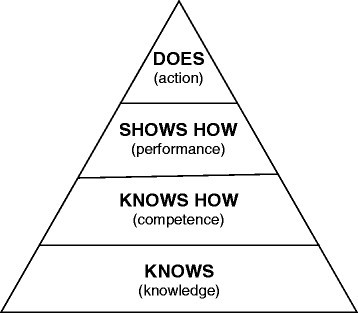

What is Competency-Based Medical Education (CBME)? Think flexible, lifelong learning, with knowledge and/or skills assessed throughout a continuum of learning. In a competency-based educational program, you don’t just acquire knowledge and then spit it back at the time of a final exam. Instead, the method of assessment is formative rather than summative, and you are evaluated on how you apply your knowledge to clinical situations that physicians often face. While summative exams, such as certification exams, play an important role in gauging levels of acquired knowledge, formative assessments are equally important.

Competency-based assessments are used to distinguish between the skills and knowledge that you already have and those for which you need more education and training. In contrast to time-based educational methods, CBME is a learner-centered, active, and lifelong experience that incorporates feedback between the teacher and the learner to fulfill the desired competency outcomes.

Adoption of the Competency-Based Medical Education Construct

The concept of competency-based training began in the 1920s, when U.S. industry and businesses started researching ways of teaching their employees the specific knowledge and skills needed to create a specific product in a standardized manner. However, in the 1960s, a movement to de-emphasize basic skills in education arose. The resulting decline in traditional scores of achievement eventually sparked a demand for the renewal of minimum standards and performance competencies.

The design of a competency-based system of education can be approached using the following steps:

- Identify the desired outcomes

- Define the level of performance for each competency

- Develop a framework for assessing competencies

- Evaluate the program on a continuous basis to be sure that the desired outcomes are being achieved

In 1999, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) and the American Board of Medical Specialties (ABMS) endorsed six domains of core competencies , and the outcome initiative (the Outcome Project) was soon launched.

The six ACGME Core Competencies are:

- Patient Care

- Medical Knowledge

- Professionalism

- Interpersonal and Communication Skills

- Practice-Based Learning and Improvement

- Systems-Based Practice

Even though there was standardized language around the core competencies of medical education, there were still no standardized assessment methods to determine whether or not a learner had achieved all of the core competencies prior to completion of residency training. This deficiency ultimately led to the creation of milestones to operationalize and implement the competencies. These milestones described the performance levels residents and fellows are expected to demonstrate for skills, knowledge, and behaviors in the six clinical competency domains and are significant points in development that are unique to each specialty.

In 2014, the ACGME required the reporting of milestones as part of the Next Accreditation System (NAS) for all ACGME-accredited residency and fellowship programs. In undergraduate medical education, there are two AAMC-defined performance levels: novice performance and performance expected of a graduating MD. In graduate medical education, there are five performance levels for each competency: novice, advanced beginner, competent individual, proficient individual, and expert physician.

The Next Goal

The Core Competencies are now the basic language for defining physician competence and are also the principles used in the training of physicians. The next goal of CBME is to link education in the competencies to improved quality of patient care. This ambitious step will require standardized methods to securely collect patient data and stratify for various clinical variables including disease specificity, overall patient health, and the multitude of health care professionals who care for each patient.

The shift to CBME was an important transition that allowed residents and fellows to be active agents in their own learning by comparing their milestone assessment and feedback data to their personal learning plans. However, the future of CBME is just being realized and offers many exciting opportunities moving forward.

You can read more about CBME here:

- Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) Core Competencies for Entering Medical Students

- Advancing Competency-Based Medical Education: A Charter for Clinician-Educators.

Share This Post!

21 comments.

The CBME is the basic and strong infrastructure of the excellent education . Thank you for your unbelievable inspiration .

The excellent medical education is capable of eliminating CVD/CAD, T2DM, and Cancer today’s growing epidemics. This will be realized when physicians will know CVD/CAD, T2DM and Cancer Inherited Real Risk, bedside diagnosed from birth and removed by unexpensive Quantum Therapy, rather than the CBME.

biology and the medical essay is interesting to read and your blog gives provide the diagnosed point, medical education tips of safety should know to every person.

The CBME is better & excellent education system. Very helpful, thanks for this.

Great information! Thanks for sharing. I would share this article at https://qanda.typicalstudent.org/ a platform for students, teachers and other related people to discuss their thoughts and experiences on learning and other topics.

Thanks a lot for allow me comment here

Over the last two decades, competency‐based frameworks have been internationally adopted as the primary educational approach in medicine. Yet competency‐based medical education (CBME) remains contested in the academic literature. We look broadly at the nature of this debate to explore how it may shape scholars’ understanding of CBME, and its implications for medical education research and practice. In doing so, we deconstruct unarticulated discourses and assumptions embedded in the CBME literature. Its really hard to garb a Government jobs with this competency.

After reading your article, I’m compelling to share your points on this topic. You have done a very good job with your attention to detail you put into this article.

Very helpful, thanks for this.

This will be realized when physicians will know CVD/CAD, T2DM and Cancer Inherited Real Risk, bedside diagnosed from birth and removed by unexpensive Quantum Therapy, rather than the CBME.

Great post, like’d your thoughts, thanks for sharing 🙂

I found this article good, interesting thoughts have been explained. keep it up, thanks for sharing

This is a very informative post for the blog writers and readers. Thanks for the sharing your concerned openly.

Great and Insightful post, Learnt a lot, for medical aspirants it is a must read. Keep posting such content.

have you developed curriculum for competence based learning .,or planning on the lines of Problem based learning.

After reading your article, I’m compelling to share your points on this topic.

The point of imparting medical education is to prepare graduates to effectively deal with the health needs of the general public. The present therapeutic training framework depends on an educational programs that is subject-focused and time based.

Great Article, i am reading your i gain lot of knowledge from this article keep post such content

In competency-based education, students work to ace abilities before they are introduced with new ideas. This gives students the opportunity to move at their own pace and take control of their education.

Some ideas of making this ingrained in knowledge: repetively teach, practice and test.from M1 to M4 the top 20 most urgent/import/deadly topic adding complexity to each year of Med Ed. Get MD input. For example:.

Top 20 most deadly diseases ie MI, Sepsis, Pulm Emboli, early Cancer detection Top 20 missed diagnoses Top 20 interpersonal physician-patient challenging discussions Top 20 ways to increase professionalism and stop being defensive Top 20 required for Boards or AACM/LCME in recognizing sings of uncommon diseases to refer to subspec. Every year do weekly practice and end of year Proficiency that the next higher medical students could teach and test with M4s being taguht and tested by either residents of MDs. Make it very straightforward, competency is goal, not trying to trick anyone. 100% to pass since so very practical and practiced and needed. Then residency and hospitals could continue adding complexity prn. Good luck and thank you!

Comments are closed.

AI in Medical Education: Global situation, effects and challenges

- Published: 10 July 2023

- Volume 29 , pages 4611–4633, ( 2024 )

Cite this article

- Wei Zhang 1 ,

- Mingxuan Cai 1 ,

- Hong Joo Lee 2 ,

- Richard Evans 3 ,

- Chengyan Zhu 4 &

- Chenghan Ming 5

2568 Accesses

5 Citations

Explore all metrics

Artificial Intelligence (AI) is transforming healthcare and shows considerable promise for the delivery of medical education. This systematic review provides a comprehensive analysis of the global situation, effects, and challenges associated with applying AI at the different stages of medical education.

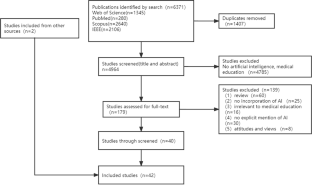

This review followed the PRISMA guidelines, and retrieved studies published on Web of Science, PubMed, Scopus, and IEEE Xplore, from 1990 to 2022. After duplicates were removed (n = 1407) from the 6371 identified records, the full text of 179 records were screened. In total, 42 records were eligible.

It revealed three teaching stages where AI can be applied in medical education (n = 39), including teaching implementation (n = 24), teaching evaluation (n = 10), and teaching feedback (n = 5). Many studies explored the effectiveness of AI adoption with questionnaire survey and control experiment. The challenges are performance improvement, effectiveness verification, AI training data sample and AI algorithms.

Conclusions

AI provides real-time feedback and accurate evaluation, and can be used to monitor teaching quality. A possible reason why AI has not yet been applied widely to practical teaching may be the disciplinary gap between developers and end-user, it is necessary to strengthen the theoretical guidance of medical education that synchronizes with the rapid development of AI. Medical educators are expected to maintain a balance between AI and teacher-led teaching, and medical students need to think independently and critically. It is also highly demanded for research teams with a wide range of disciplines to ensure the applicability of AI in medical education.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

AIM in Medical Education

AI’s Role and Application in Education: Systematic Review

Data availability.

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Aldeman, N. L. S., de SáUrtigaAita, K. M., Machado, V. P., da Mata Sousa, L. C. D., Coelho, A. G. B., da Silva, A. S., Silva Mendes, A. P., de Oliveira Neres, F. J., & do Monte, S. J. H. (2021). Smartpathk: A platform for teaching glomerulopathies using machine learning. BMC Medical Education, 21 (1), 248. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-021-02680-1

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Alonso-Silverio, G. A., Pérez-Escamirosa, F., Bruno-Sanchez, R., Ortiz-Simon, J. L., Muñoz-Guerrero, R., Minor-Martinez, A., & Alarcón-Paredes, A. (2018). Development of a Laparoscopic Box Trainer Based on Open Source Hardware and Artificial Intelligence for Objective Assessment of Surgical Psychomotor Skills. Surgical Innovation, 25 (4), 380–388. https://doi.org/10.1177/1553350618777045

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Baloul, M. S., Yeh, V.J.-H., Mukhtar, F., Ramachandran, D., Traynor, M. D., Shaikh, N., Rivera, M., & Farley, D. R. (2022). Video Commentary & Machine Learning: Tell Me What You See, I Tell You Who You Are. Journal of Surgical Education, 79 (6), e263–e272. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsurg.2020.09.022

Bienstock, J. L., Katz, N. T., Cox, S. M., Hueppchen, N., Erickson, S., & Puscheck, E. E. (2007). To the point: Medical education reviews—providing feedback. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 196 (6), 508–513. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2006.08.021

Bing-You, R., Hayes, V., Varaklis, K., Trowbridge, R., Kemp, H., & McKelvy, D. (2017). Feedback for Learners in Medical Education: What Is Known? A Scoping Review . Wolters Kluwer. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000001578

Bissonnette, V., Mirchi, N., Ledwos, N., Alsidieri, G., Winkler-Schwartz, A., Del Maestro, R. F., Yilmaz, R., Siyar, S., Azarnoush, H., Karlik, B., Sawaya, R., Alotaibi, F. E., Bugdadi, A., Bajunaid, K., Ouellet, J., & Berry, G. (2019). Artificial Intelligence Distinguishes Surgical Training Levels in a Virtual Reality Spinal Task. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery-American, 101 (23), e127. https://doi.org/10.2106/JBJS.18.01197

Article Google Scholar

Borakati, A. (2021). Evaluation of an international medical E-learning course with natural language processing and machine learning. BMC Medical Education, 21 (1), 181. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-021-02609-8

Chan, H.-P., Samala, R. K., Hadjiiski, L. M., & Zhou, C. (2020). Deep Learning in Medical Image Analysis. In G. Lee & H. Fujita ( Ed.), Deep Learning in Medical Image Analysis: Challenges and Applications (pp. 3–21). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-33128-3_1

Chan, K. S., & Zary, N. (2019). Applications and Challenges of Implementing Artificial Intelligence in Medical Education: Integrative Review. JMIR Medical Education, 5 (1), e13930. https://doi.org/10.2196/13930

Chen, C.-K. (2010). Curriculum Assessment Using Artificial Neural Network and Support Vector Machine Modeling Approaches: A Case Study. IR Applications. Volume 29. In Association for Institutional Research (NJ1) . Association for Institutional Research. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED524832

Chen, L., Chen, P., & Lin, Z. (2020). Artificial Intelligence in Education: A Review. Ieee Access, 8 , 75264–75278. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2020.2988510

Cheng, C.-T., Chen, C.-C., Fu, C.-Y., Chaou, C.-H., Wu, Y.-T., Hsu, C.-P., Chang, C.-C., Chung, I.-F., Hsieh, C.-H., Hsieh, M.-J., & Liao, C.-H. (2020). Artificial intelligence-based education assists medical students’ interpretation of hip fracture. Insights into Imaging, 11 (1), 119. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13244-020-00932-0

de Lima, R. M., de Medeiros Santos, A., Mendes Neto, F. M., de Sousa, F., Neto, A., Leão, F. C. P., de Macedo, F. T., & de Paula Canuto, A. M. (2016). A 3D serious game for medical students training in clinical cases. IEEE International Conference on Serious Games and Applications for Health (SeGAH), 2016 , 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1109/SeGAH.2016.7586255

Dharmasaroja, P., & Kingkaew, N. (2016). Application of artificial neural networks for prediction of learning performances. 2016 12th International Conference on Natural Computation, Fuzzy Systems and Knowledge Discovery (ICNC-FSKD) , 745–751. https://doi.org/10.1109/FSKD.2016.7603268

Estai, M., & Bunt, S. (2016). Best teaching practices in anatomy education: A critical review. Annals of Anatomy - Anatomischer Anzeiger, 208 , 151–157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aanat.2016.02.010

Fajrianti, E. D., Sukaridhoto, S., Rasyid, M. U. H. A., Suwito, B. E., Budiarti, R. P. N., Hafidz, I. A. A., Satrio, N. A., & Haz, A. L. (2022). Application of Augmented Intelligence Technology with Human Body Tracking for Human Anatomy Education. IJIET: International Journal of Information and Education Technology , 12 (6), Article 6.

Fang, Z., Xu, Z., He, X., & Han, W. (2022).Artificial intelligence-based pathologic myopia identification system in the ophthalmology residency training program. Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology , 10 . https://doi.org/10.3389/fcell.2022.1053079

Fazlollahi, A. M., Bakhaidar, M., Alsayegh, A., Yilmaz, R., Winkler-Schwartz, A., Mirchi, N., Langleben, I., Ledwos, N., Sabbagh, A. J., Bajunaid, K., Harley, J. M., & Del Maestro, R. F. (2022). Effect of Artificial Intelligence Tutoring vs Expert Instruction on Learning Simulated Surgical Skills Among Medical Students: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Network Open, 5 (2), e2149008. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.49008

Fernández-Alemán, J. L., López-González, L., González-Sequeros, O., Jayne, C., López-Jiménez, J. J., & Toval, A. (2016). The evaluation of i-SIDRA – a tool for intelligent feedback – in a course on the anatomy of the locomotor system. International Journal of Medical Informatics, 94 , 172–181. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2016.07.008

Foss, C. L. (1987). Learning from errors in ALGEBRALAND . Institute for Research on Learning.

Furlan, R., Gatti, M., Menè, R., Shiffer, D., Marchiori, C., Levra, A. G., Saturnino, V., Brunetta, E., & Dipaola, F. (2021). A Natural Language Processing-Based Virtual Patient Simulator and Intelligent Tutoring System for the Clinical Diagnostic Process: Simulator Development and Case Study. JMIR Medical Informatics, 9 (4), e24073. https://doi.org/10.2196/24073

Gendia, A. (2022). Cloud Based AI-Driven Video Analytics (CAVs) in Laparoscopic Surgery: A Step Closer to a Virtual Portfolio. Cureus , 14 (9). https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.29087

Gil, D. H., Heins, M., & Jones, P. B. (1984). Perceptions of medical school faculty members and students on clinical clerkship feedback. Academic Medicine, 59 (11), 856.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Goh, P. S. (2021). The vision of transformation in medical education after the COVID-19 pandemic. Korean Journal of Medical Education, 33 (3), 171–174. https://doi.org/10.3946/kjme.2021.197

Article MathSciNet PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Gorospe-Sarasúa, L., Munoz-Olmedo, J. M., Sendra-Portero, F., & de Luis-García, R. (2022a). Challenges of Radiology education in the era of artificial intelligence . 6.

Gorospe-Sarasúa, L., Muñoz-Olmedo, J. M., Sendra-Portero, F., & de Luis-García, R. (2022b). Challenges of Radiology education in the era of artificial intelligence. Radiología (english Edition), 64 (1), 54–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rxeng.2020.10.012

Han, R., Yu, W., Chen, H., & Chen, Y. (2022). Using artificial intelligence reading label system in diabetic retinopathy grading training of junior ophthalmology residents and medical students. BMC Medical Education , 22 (1), Article 1. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-022-03272-3

Hattie, J., & Timperley, H. (2007). The power of feedback. Review of educational research, 77 (1), 81–112. https://doi.org/10.3102/003465430298487

Hedderich, D. M., Keicher, M., Wiestler, B., Gruber, M. J., Burwinkel, H., Hinterwimmer, F., Czempiel, T., Spiro, J. E., Pinto dos Santos, D., Heim, D., Zimmer, C., Rückert, D., Kirschke, J. S., & Navab, N. (2021). AI for Doctors—A Course to Educate Medical Professionals in Artificial Intelligence for Medical Imaging. Healthcare , 9 (10), Article 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare9101278

Hewson, M. G., & Little, M. L. (1998). Giving Feedback in Medical Education. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 13 (2), 111–116. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1497.1998.00027.x

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Hisan, U. K., & Amri, M. M. (2023). ChatGPT and Medical Education: A Double-Edged Sword. Journal of Pedagogy and Education Science , 2 (01), Article 01. https://doi.org/10.56741/jpes.v2i01.302

Hisey, R., Camire, D., Erb, J., Howes, D., Fichtinger, G., & Ungi, T. (2022). System for Central Venous Catheterization Training Using Computer Vision-Based Workflow Feedback. IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering, 69 (5), 1630–1638. https://doi.org/10.1109/TBME.2021.3124422

Hosny, A., Parmar, C., Quackenbush, J., Schwartz, L. H., & Aerts, H. J. W. L. (2018). Artificial intelligence in radiology. Nature Reviews Cancer , 18 (8), Article 8. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41568-018-0016-5

Hu, H., Li, J., Lei, X., Qin, P., & Chen, Q. (2019). Design of health statistics intelligent education system based on Internet +. Journal of Physics: Conference Series, 1168 (6), 062003. https://doi.org/10.1088/1742-6596/1168/6/062003

Hwang, G.-J., Xie, H., Wah, B. W., & Gašević, D. (2020). Vision, challenges, roles and research issues of Artificial Intelligence in Education. Computers and Education: Artificial Intelligence, 1 , 100001. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.caeai.2020.100001

Islam, G., Kahol, K., Li, B., Smith, M., & Patel, V. L. (2016). Affordable, web-based surgical skill training and evaluation tool. Journal of Biomedical Informatics, 59 , 102–114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbi.2015.11.002

Karambakhsh, A., Kamel, A., Sheng, B., Li, P., Yang, P., & Feng, D. D. (2019). Deep gesture interaction for augmented anatomy learning. International Journal of Information Management, 45 , 328–336. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2018.03.004

Kirubarajan, A., Young, D., Khan, S., Crasto, N., Sobel, M., & Sussman, D. (2022). Artificial Intelligence and Surgical Education: A Systematic Scoping Review of Interventions. Journal of Surgical Education, 79 (2), 500–515. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsurg.2021.09.012

Klar, R., & Bayer, U. (1990). Computer-assisted teaching and learning in medicine. International Journal of Bio-Medical Computing, 26 (1–2), 7–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/0020-7101(90)90016-N

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Kurniawan, M. H., Suharjito, Diana, & Witjaksono, G. (2018). Human Anatomy Learning Systems Using Augmented Reality on Mobile Application . 135 , 80–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procs.2018.08.152

Lam, A., Lam, L., Blacketer, C., Parnis, R., Franke, K., Wagner, M., Wang, D., Tan, Y., Oakden-Rayner, L., Gallagher, S., Perry, S. W., Licinio, J., Symonds, I., Thomas, J., Duggan, P., & Bacchi, S. (2022a). Professionalism and clinical short answer question marking with machine learning. Internal Medicine Journal, 52 (7), 1268–1271. https://doi.org/10.1111/imj.15839

Lam, K., Chen, J., Wang, Z., Iqbal, F. M., Darzi, A., Lo, B., Purkayastha, S., & Kinross, J. M. (2022b). Machine learning for technical skill assessment in surgery: A systematic review. Npj Digital Medicine , 5(1), Article 1. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-022-00566-0

Lazarus, M. D., Truong, M., Douglas, P., & Selwyn, N. (2022). Artificial intelligence and clinical anatomical education: Promises and perils. Anatomical Sciences Education , n/a (n/a). https://doi.org/10.1002/ase.2221

Lee, J., Wu, A. S., Li, D., Kulasegaram, K., & (Mahan). (2021). Artificial Intelligence in Undergraduate Medical Education: A Scoping Review. Academic Medicine, 96 (11S), S62. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000004291

Lee, L. S., Aluwee, S. A. Z. S., Meng, G. C., Palanisamy, P., & Subramaniam, R. (2020). Interactive Tool Using Augmented Reality (AR) for Learning Knee and Foot Anatomy Based on CT Images 3D Reconstruction. 2020 International Conference on Computational Intelligence (ICCI) , 281–286. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICCI51257.2020.9247820

Li, Y., Bai, C., & Reddy, C. K. (2016). A distributed ensemble approach for mining healthcare data under privacy constraints. Information Sciences, 330 , 245–259. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ins.2015.10.011

Li, Y. S., Lam, C. S. N., & See, C. (2021). Using a Machine Learning Architecture to Create an AI-Powered Chatbot for Anatomy Education. Medical Science Educator, 31 (6), 1729–1730. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40670-021-01405-9

Luan, H., Geczy, P., Lai, H., Gobert, J., Yang, S. J. H., Ogata, H., Baltes, J., Guerra, R., Li, P., & Tsai, C.-C. (2020). Challenges and Future Directions of Big Data and Artificial Intelligence in Education. Frontiers in Psychology , 11 . https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.580820

Martin, J. A., Regehr, G., Reznick, R., Macrae, H., Murnaghan, J., Hutchison, C., & Brown, M. (1997). Objective structured assessment of technical skill (OSATS) for surgical residents. BJS (british Journal of Surgery), 84 (2), 273–278. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2168.1997.02502.x

Mirchi, N., Bissonnette, V., Yilmaz, R., Ledwos, N., Winkler-Schwartz, A., & Del Maestro, R. F. (2020). The Virtual Operative Assistant: An explainable artificial intelligence tool for simulation-based training in surgery and medicine. Plos One, 15 (2), e0229596. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0229596

Muller, S. (1984). Physicians for the twenty-first century: Report of the project panel on the general professional education of the physician and college preparation for medicine. Journal of Medical Education, 59 , 1–208.

Google Scholar

Nagaraj, M. B., Namazi, B., Sankaranarayanan, G., & Scott, D. J. (2023). Developing artificial intelligence models for medical student suturing and knot-tying video-based assessment and coaching. Surgical Endoscopy, 37 (1), 402–411. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-022-09509-y

Nakawala, H., Ferrigno, G., & De Momi, E. (2018). Development of an intelligent surgical training system for Thoracentesis. Artificial Intelligence in Medicine, 84 , 50–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.artmed.2017.10.004

Neves, S. E., Chen, M. J., Ku, C. M., Karan, S., DiLorenzo, A. N., Schell, R. M., Lee, D. E., Diachun, C. A. B., Jones, S. B., & Mitchell, J. D. (2021). Using Machine Learning to Evaluate Attending Feedback on Resident Performance. Anesthesia & Analgesia, 132 (2), 545–555. https://doi.org/10.1213/ANE.0000000000005265

Niitsu, H., Hirabayashi, N., Yoshimitsu, M., Mimura, T., Taomoto, J., Sugiyama, Y., Murakami, S., Saeki, S., Mukaida, H., & Takiyama, W. (2013). Using the Objective Structured Assessment of Technical Skills (OSATS) global rating scale to evaluate the skills of surgical trainees in the operating room. Surgery Today, 43 (3), 271–275. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00595-012-0313-7

Ötles, E., Kendrick, D. E., Solano, Q. P., Schuller, M., Ahle, S. L., Eskender, M. H., Carnes, E., & George, B. C. (2021). Using Natural Language Processing to Automatically Assess Feedback Quality: Findings From 3 Surgical Residencies. Academic Medicine, 96 (10), 1457. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000004153

Ouyang, F., Zheng, L., & Jiao, P. (2022). Artificial intelligence in online higher education: A systematic review of empirical research from 2011 to 2020. Education and Information Technologies . https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-022-10925-9

Peter, H., & Goodridge, W. (2004). Integrating Two Artificial Intelligence Theories in a Medical Diagnosis Application. In M. Bramer & V. Devedzic ( Ed.), Artificial Intelligence Applications and Innovations (pp. 11–23). Springer US. https://doi.org/10.1007/1-4020-8151-0_2

Qian, X., Jingying, H., Xian, S., Yuqing, Z., Lili, W., Baorui, C., Wei, G., Yefeng, Z., Qiang, Z., Chunyan, C., Cheng, B., Kai, M., & Yi, Q. (2022). The effectiveness of artificial intelligence-based automated grading and training system in education of manual detection of diabetic retinopathy. Frontiers in Public Health, 10 , 1025271. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2022.1025271

Razzak, M. I., Naz, S., & Zaib, A. (2018). Deep Learning for Medical Image Processing: Overview, Challenges and the Future. In N. Dey, A. S. Ashour, & S. Borra ( Ed.), Classification in BioApps: Automation of Decision Making (pp. 323–350). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-65981-7_12

Sadeghi Esfahlani, S., Izsof, V., Minter, S., Kordzadeh, A., Shirvani, H., & Esfahlani, K. S. (2020). Development of an Interactive Virtual Reality for Medical Skills Training Supervised by Artificial Neural Network. In Y. Bi, R. Bhatia, & S. Kapoor ( Ed.), Intelligent Systems and Applications (pp. 473–482). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-29513-4_34

Shiang, T., Garwood, E., & Debenedectis, C. M. (2022). Artificial intelligence-based decision support system (AI-DSS) implementation in radiology residency: Introducing residents to AI in the clinical setting. Clinical Imaging, 92 , 32–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinimag.2022.09.003

Siyar, S., Azarnoush, H., Rashidi, S., Winkler-Schwartz, A., Bissonnette, V., Ponnudurai, N., & Del Maestro, R. F. (2020). Machine learning distinguishes neurosurgical skill levels in a virtual reality tumor resection task. Medical and Biological Engineering and Computing, 58 (6), 1357–1367. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11517-020-02155-3

Solano, Q. P., Hayward, L., Chopra, Z., Quanstrom, K., Kendrick, D., Abbott, K. L., Kunzmann, M., Ahle, S., Schuller, M., Ötleş, E., & George, B. C. (2021). Natural Language Processing and Assessment of Resident Feedback Quality. Journal of Surgical Education, 78 (6), e72–e77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsurg.2021.05.012

Stephens, G. C., Rees, C. E., & Lazarus, M. D. (2021). Exploring the impact of education on preclinical medical students’ tolerance of uncertainty: A qualitative longitudinal study. Advances in Health Sciences Education, 26 (1), 53–77. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-020-09971-0

Sqalli, M. T., Al-Thani, D., Elshazly, M. B., & Al-Hijji, M. (2022). A Blueprint for an AI & AR-Based Eye Tracking System to Train Cardiology Professionals Better Interpret Electrocardiograms. In N. Baghaei, J. Vassileva, R. Ali, & K. Oyibo ( Ed.), Persuasive Technology (pp. 221–229). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-98438-0_17

Szasz, P., Louridas, M., Harris, K. A., Aggarwal, R., & Grantcharov, T. P. (2015). Assessing Technical Competence in Surgical Trainees: A Systematic Review. Annals of Surgery, 261 (6), 1046. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0000000000000866

Torre, D. M., Sebastian, J. L., & Simpson, D. E. (2003). Learning Activities and High-Quality Teaching: Perceptions of Third-Year IM Clerkship Students. Academic Medicine, 78 (8), 812.

Vayena, E., & Blasimme, A. (2017). Biomedical Big Data: New Models of Control Over Access, Use and Governance. Journal of Bioethical Inquiry, 14 (4), 501–513. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11673-017-9809-6

Voss, G., Bockholt, U., Los Arcos, J. L., Müller, W., Oppelt, P., & Stähler, J. (2000). Lahystotrain. Studies in Health Technology and Informatics, 70 , 359–364. https://doi.org/10.3233/978-1-60750-914-1-359

Wang, M., Sun, Z., Jia, M., Wang, Y., Wang, H., Zhu, X., Chen, L., & Ji, H. (2022). Intelligent virtual case learning system based on real medical records and natural language processing. BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making, 22 (1), 60. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12911-022-01797-7

Willan, P. L. T., & Humpherson, J. R. (1999). Concepts of variation and normality in morphology: Important issues at risk of neglect in modern undergraduate medical courses. Clinical Anatomy, 12 (3), 186–190. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1098-2353(1999)12:3%3c186::AID-CA7%3e3.0.CO;2-6

Wolverton, S. E., & Bosworth, M. F. (1985). A survey of resident perceptions of effective teaching behaviors. Family Medicine, 17 (3), 106–108.

CAS PubMed Google Scholar