How to Write an Essay/Parts

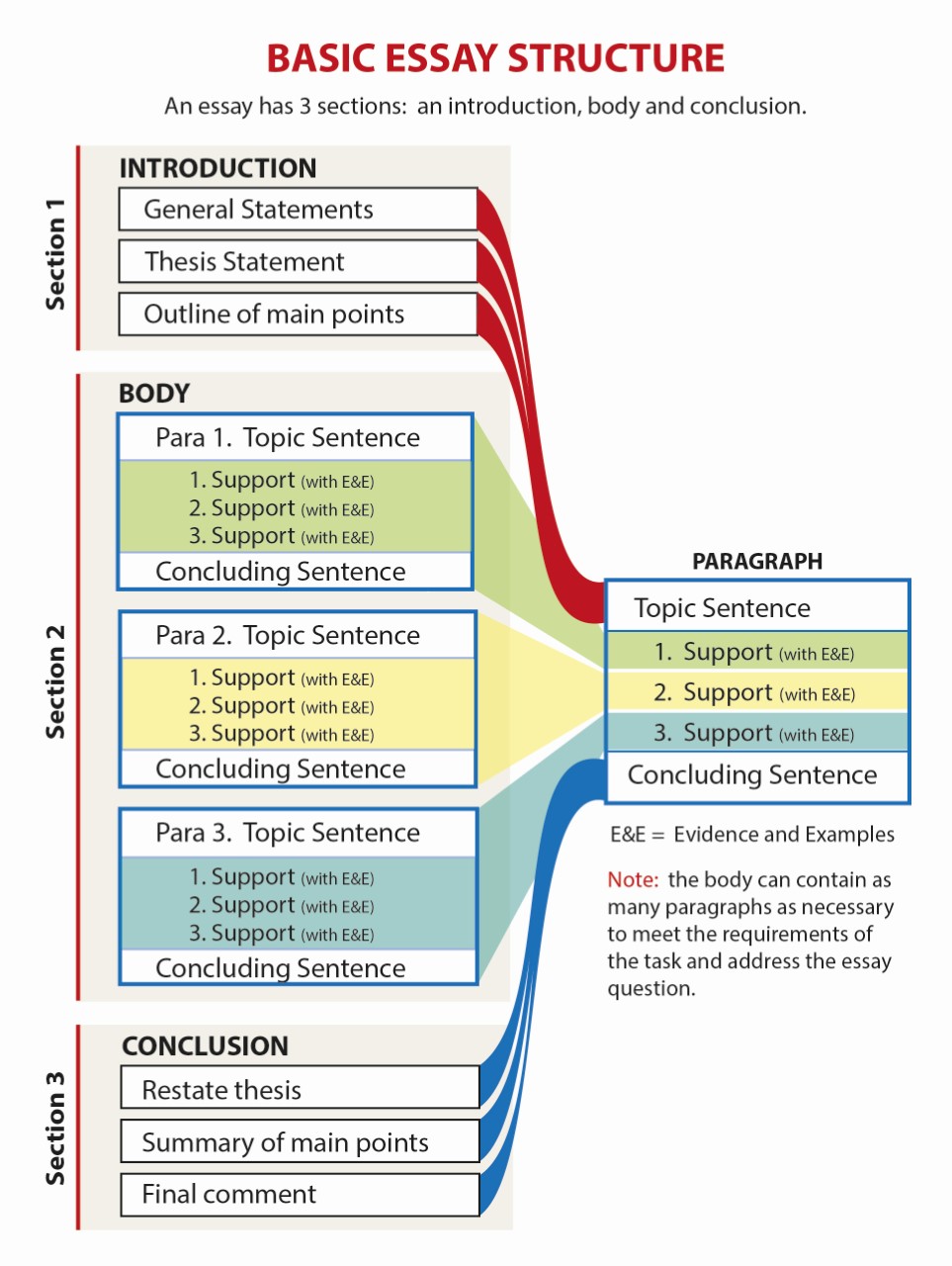

Parts of an Essay — Traditionally, it has been taught that a formal essay consists of three parts: the introductory paragraph or introduction, the body paragraphs, and the concluding paragraph. An essay does not need to be this simple, but it is a good starting point.

Introductory Paragraph [ edit | edit source ]

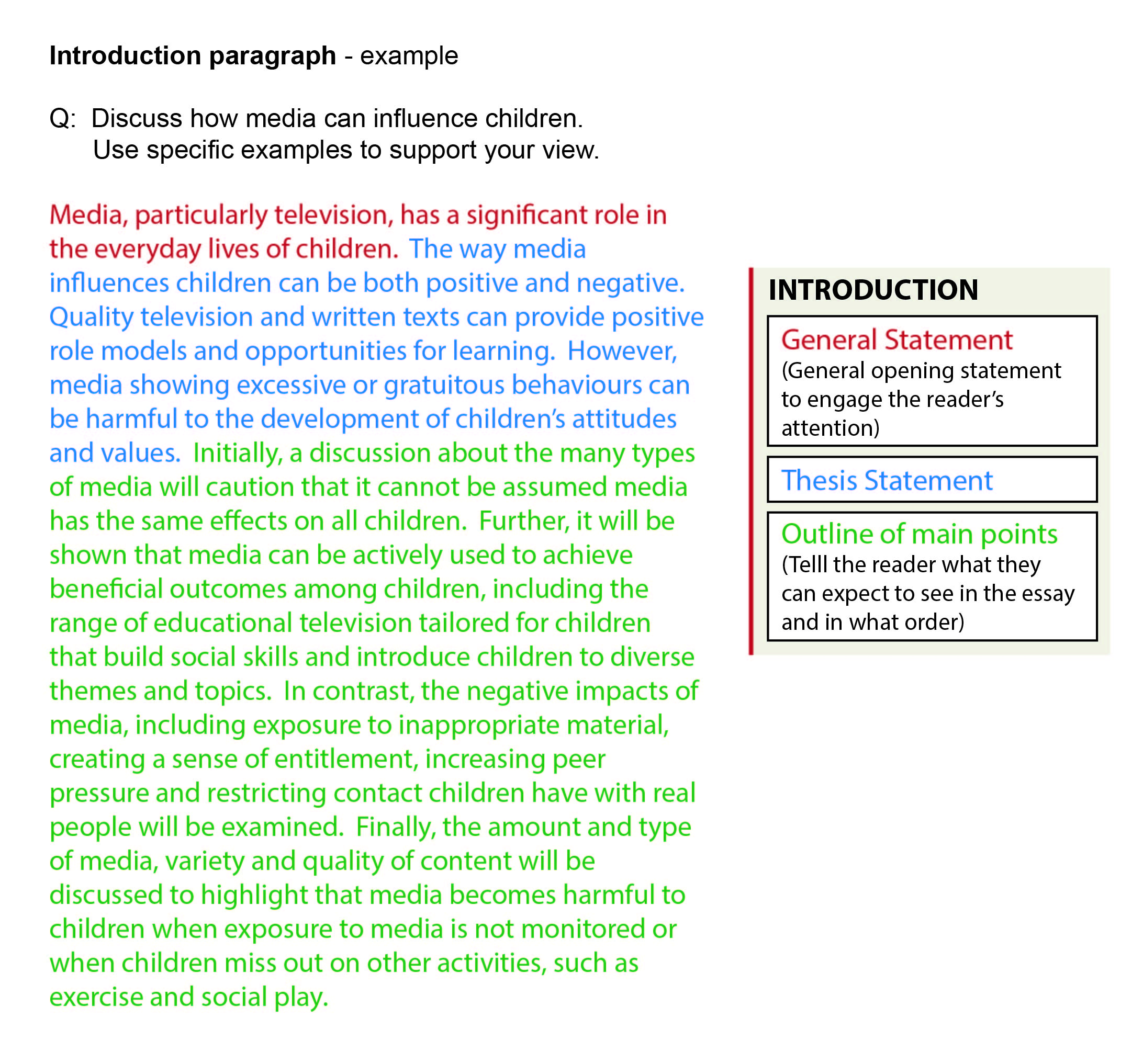

The introductory paragraph accomplishes three purposes: it captures the reader’s interest, it suggests the importance of the essay’s topic, and it ends with a thesis sentence. Often, the thesis sentence states a claim that consists of two or more related points. For example, a thesis might read:

You are telling the reader what you think are the most important points which need to be addressed in your essay. For this reason, you need to relate the introduction directly to the question or topic. A strong thesis is essential to a good essay, as each paragraph of your essay should be related back to your thesis or else deleted. Thus, the thesis establishes the key foundation for your essay. A strong thesis not only states an idea but also uses solid examples to back it up. A weak thesis might be:

As an alternative, a strong thesis for the same topic would be:

Then, you could separate your body paragraphs into three sections: one explaining the open-source nature of the project, one explaining the variety and depth of information, and a final one using studies to confirm that Wikipedia is indeed as accurate as other encyclopedias.

Tips [ edit | edit source ]

Often, writing an introductory paragraph is the most difficult part of writing an essay. Facing a blank page can be daunting. Here are some suggestions for getting started. First, determine the context in which you want to place your topic. In other words, identify an overarching category in which you would place your topic, and then introduce your topic as a case-in-point.

For example, if you are writing about dogs, you may begin by speaking about friends, dogs being an example of a very good friend. Alternatively, you can begin with a sentence on selective breeding, dogs being an example of extensive selective breeding. You can also begin with a sentence on means of protection, dogs being an example of a good way to stay safe. The context is the starting point for your introductory paragraph. The topic or thesis sentence is the ending point. Once the starting point and ending point are determined, it will be much easier to connect these points with the narrative of the opening paragraph.

A good thesis statement, for example, if you are writing about dogs being very good friends, you could put:

Here, X, Y, and Z would be the topics explained in your body paragraphs. In the format of one such instance, X would be the topic of the second paragraph, Y would be the topic of the third paragraph, and Z would be the topic of the fourth paragraph, followed by a conclusion, in which you would summarize the thesis statement.

Example [ edit | edit source ]

Identifying a context can help shape the topic or thesis. Here, the writer decided to write about dogs. Then, the writer selected friends as the context, dogs being good examples of friends. This shaped the topic and narrowed the focus to dogs as friends . This would make writing the remainder of the essay much easier because it allows the writer to focus on aspects of dogs that make them good friends.

Body Paragraphs [ edit | edit source ]

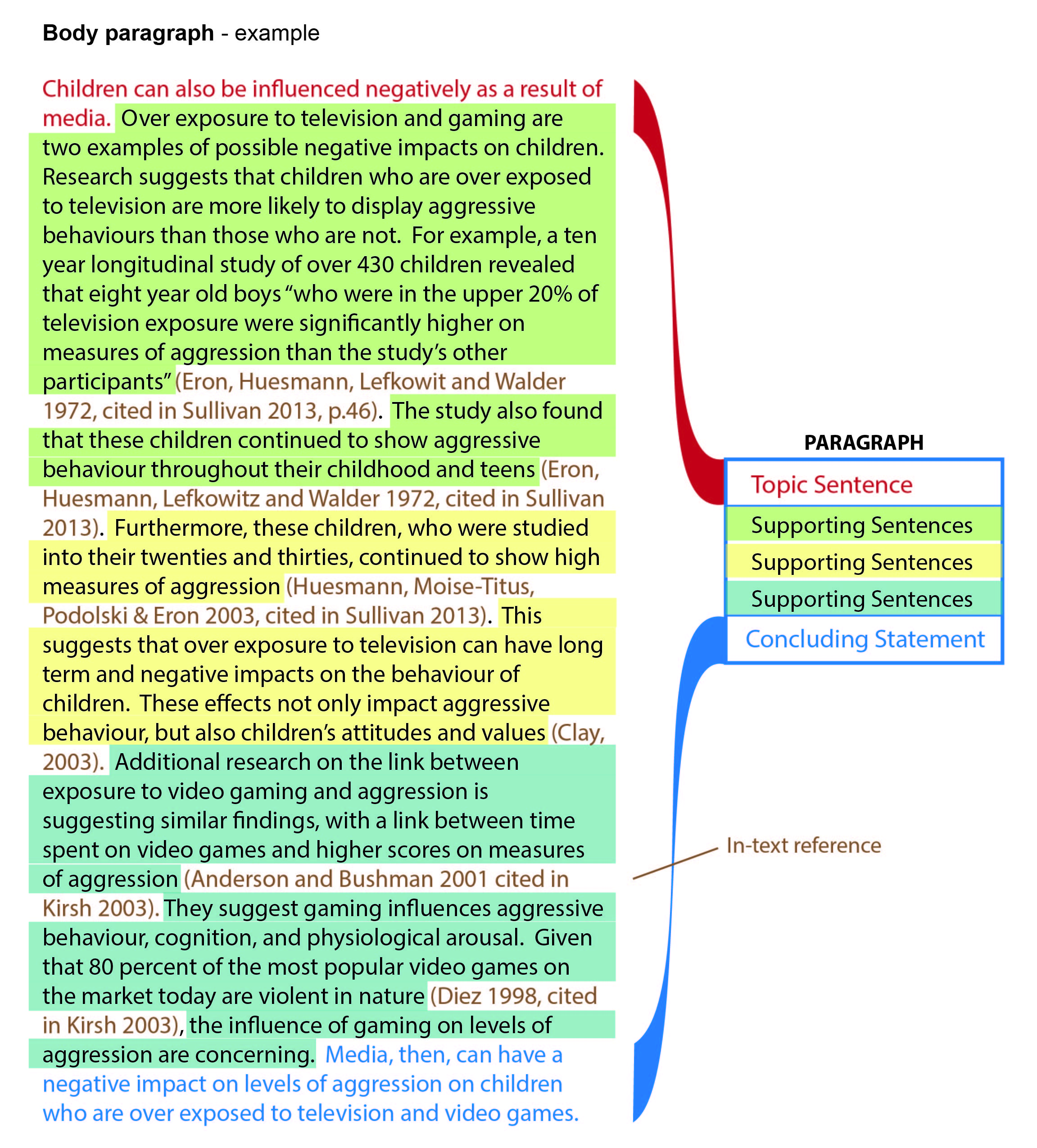

Each body paragraph begins with a topic sentence. If the thesis contains multiple points or assertions, each body paragraph should support or justify them, preferably in the order the assertions originally stated in the thesis. Thus, the topic sentence for the first body paragraph will refer to the first point in the thesis sentence and the topic sentence for the second body paragraph will refer to the second point in the thesis sentence. Generally, if the thesis sentence contains three related points, there should be three body paragraphs, though you should base the number of paragraphs on the number of supporting points needed.

If the core topic of the essay is the format of college essays, the thesis sentence might read:

The topic sentence for the first body paragraph might read:

Sequentially, the topic sentence for the second body paragraph might read:

And the topic sentence for the third body paragraph might read:

Every body paragraph uses specific details, such as anecdotes, comparisons and contrasts, definitions, examples, expert opinions, explanations, facts, and statistics to support and develop the claim that its topic sentence makes.

When writing an essay for a class assignment, make sure to follow your teacher or professor’s suggestions. Most teachers will reward creativity and thoughtful organization over dogmatic adherence to a prescribed structure. Many will not. If you are not sure how your teacher will respond to a specific structure, ask.

Organizing your essay around the thesis sentence should begin with arranging the supporting elements to justify the assertion put forth in the thesis sentence. Not all thesis sentences will, or should, lay out each of the points you will cover in your essay. In the example introductory paragraph on dogs, the thesis sentence reads, “There is no friend truer than a dog.” Here, it is the task of the body paragraphs to justify or prove the truth of this assertion, as the writer did not specify what points they would cover. The writer may next ask what characteristics dogs have that make them true friends. Each characteristic may be the topic of a body paragraph. Loyalty, companionship, protection, and assistance are all terms that the writer could apply to dogs as friends. Note that if the writer puts dogs in a different context, for example, working dogs, the thesis might be different, and they would be focusing on other aspects of dogs.

It is often effective to end a body paragraph with a sentence that rationalizes its presence in the essay. Ending a body paragraph without some sense of closure may cause the thought to sound incomplete.

Each body paragraph is something like a miniature essay in that they each need an introductory sentence that sounds important and interesting, and that they each need a good closing sentence in order to produce a smooth transition between one point and the next. Body paragraphs can be long or short. It depends on the idea you want to develop in your paragraph. Depending on the specific style of the essay, you may be able to use very short paragraphs to signal a change of subject or to explain how the rest of the essay is organized.

Do not spend too long on any one point. Providing extensive background may interest some readers, but others would find it tiresome. Keep in mind that the main importance of an essay is to provide a basic background on a subject and, hopefully, to spark enough interest to induce further reading.

The above example is a bit free-flowing and the writer intended it to be persuasive. The second paragraph combines various attributes of dogs including protection and companionship. Here is when doing a little research can also help. Imagine how much more effective the last statement would be if the writer cited some specific statistics and backed them up with a reliable reference.

Concluding Paragraph [ edit | edit source ]

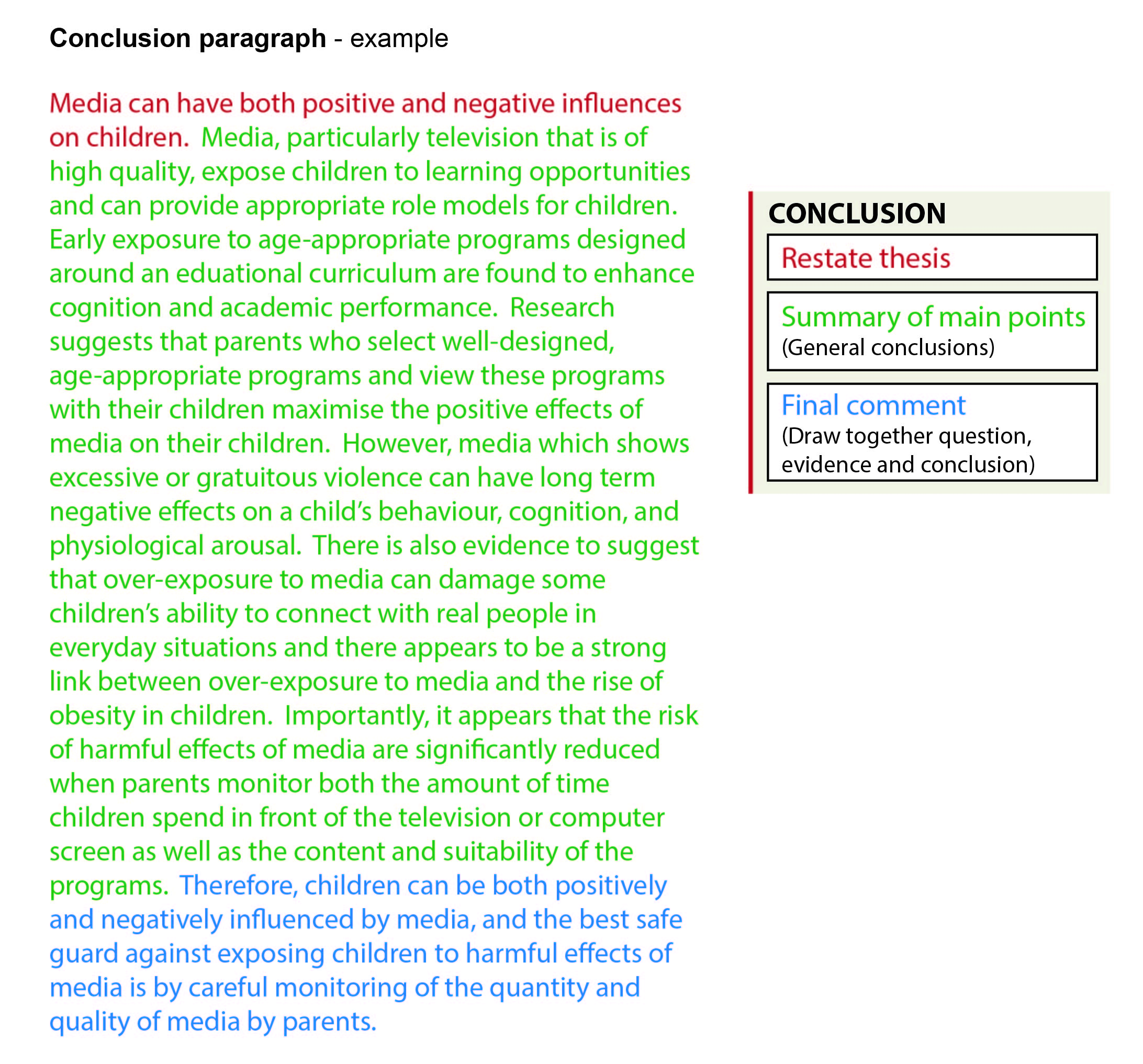

The concluding paragraph usually restates the thesis and leaves the reader something about the topic to think about. If appropriate, it may also issue a call to act, inviting the reader to take a specific course of action with regard to the points that the essay presented.

Aristotle suggested that speakers and, by extension, writers should tell their audience what they are going to say, say it, and then tell them what they have said. The three-part essay model, consisting of an introductory paragraph, several body paragraphs, and a concluding paragraph, follows this strategy.

As with all writing, it is important to know your audience. All writing is persuasive, and if you write with your audience in mind, it will make your argument much more persuasive to that particular audience. When writing for a class assignment, the audience is your teacher. Depending on the assignment, the point of the essay may have nothing to do with the assigned topic. In most class assignments, the purpose is to persuade your teacher that you have a good grasp of grammar and spelling, that you can organize your thoughts in a comprehensive manner, and, perhaps, that you are capable of following instructions and adhering to some dogmatic formula the teacher regards as an essay. It is much easier to persuade your teacher that you have these capabilities if you can make your essay interesting to read at the same time. Place yourself in your teacher’s position and try to imagine reading one formulaic essay after another. If you want yours to stand out, capture your teacher’s attention and make your essay interesting, funny, or compelling.

In the above example, the focus shifted slightly and talked about dogs as members of the family. Many would suggest it departs from the logical organization of the rest of the essay, and some teachers may consider it unrelated and take points away. However, contrary to the common wisdom of “tell them what you are going to say, say it, and then tell them what you have said,” you may find it more interesting and persuasive to shift away from it as the writer did here, and then, in the end, return to the core point of the essay. This gives an additional effect to what an audience would otherwise consider a very boring conclusion.

- Book:How to Write an Essay

Navigation menu

How to Write an Essay

Use the links below to jump directly to any section of this guide:

Essay Writing Fundamentals

How to prepare to write an essay, how to edit an essay, how to share and publish your essays, how to get essay writing help, how to find essay writing inspiration, resources for teaching essay writing.

Essays, short prose compositions on a particular theme or topic, are the bread and butter of academic life. You write them in class, for homework, and on standardized tests to show what you know. Unlike other kinds of academic writing (like the research paper) and creative writing (like short stories and poems), essays allow you to develop your original thoughts on a prompt or question. Essays come in many varieties: they can be expository (fleshing out an idea or claim), descriptive, (explaining a person, place, or thing), narrative (relating a personal experience), or persuasive (attempting to win over a reader). This guide is a collection of dozens of links about academic essay writing that we have researched, categorized, and annotated in order to help you improve your essay writing.

Essays are different from other forms of writing; in turn, there are different kinds of essays. This section contains general resources for getting to know the essay and its variants. These resources introduce and define the essay as a genre, and will teach you what to expect from essay-based assessments.

Purdue OWL Online Writing Lab

One of the most trusted academic writing sites, Purdue OWL provides a concise introduction to the four most common types of academic essays.

"The Essay: History and Definition" (ThoughtCo)

This snappy article from ThoughtCo talks about the origins of the essay and different kinds of essays you might be asked to write.

"What Is An Essay?" Video Lecture (Coursera)

The University of California at Irvine's free video lecture, available on Coursera, tells you everything you need to know about the essay.

Wikipedia Article on the "Essay"

Wikipedia's article on the essay is comprehensive, providing both English-language and global perspectives on the essay form. Learn about the essay's history, forms, and styles.

"Understanding College and Academic Writing" (Aims Online Writing Lab)

This list of common academic writing assignments (including types of essay prompts) will help you know what to expect from essay-based assessments.

Before you start writing your essay, you need to figure out who you're writing for (audience), what you're writing about (topic/theme), and what you're going to say (argument and thesis). This section contains links to handouts, chapters, videos and more to help you prepare to write an essay.

How to Identify Your Audience

"Audience" (Univ. of North Carolina Writing Center)

This handout provides questions you can ask yourself to determine the audience for an academic writing assignment. It also suggests strategies for fitting your paper to your intended audience.

"Purpose, Audience, Tone, and Content" (Univ. of Minnesota Libraries)

This extensive book chapter from Writing for Success , available online through Minnesota Libraries Publishing, is followed by exercises to try out your new pre-writing skills.

"Determining Audience" (Aims Online Writing Lab)

This guide from a community college's writing center shows you how to know your audience, and how to incorporate that knowledge in your thesis statement.

"Know Your Audience" ( Paper Rater Blog)

This short blog post uses examples to show how implied audiences for essays differ. It reminds you to think of your instructor as an observer, who will know only the information you pass along.

How to Choose a Theme or Topic

"Research Tutorial: Developing Your Topic" (YouTube)

Take a look at this short video tutorial from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill to understand the basics of developing a writing topic.

"How to Choose a Paper Topic" (WikiHow)

This simple, step-by-step guide (with pictures!) walks you through choosing a paper topic. It starts with a detailed description of brainstorming and ends with strategies to refine your broad topic.

"How to Read an Assignment: Moving From Assignment to Topic" (Harvard College Writing Center)

Did your teacher give you a prompt or other instructions? This guide helps you understand the relationship between an essay assignment and your essay's topic.

"Guidelines for Choosing a Topic" (CliffsNotes)

This study guide from CliffsNotes both discusses how to choose a topic and makes a useful distinction between "topic" and "thesis."

How to Come Up with an Argument

"Argument" (Univ. of North Carolina Writing Center)

Not sure what "argument" means in the context of academic writing? This page from the University of North Carolina is a good place to start.

"The Essay Guide: Finding an Argument" (Study Hub)

This handout explains why it's important to have an argument when beginning your essay, and provides tools to help you choose a viable argument.

"Writing a Thesis and Making an Argument" (University of Iowa)

This page from the University of Iowa's Writing Center contains exercises through which you can develop and refine your argument and thesis statement.

"Developing a Thesis" (Harvard College Writing Center)

This page from Harvard's Writing Center collates some helpful dos and don'ts of argumentative writing, from steps in constructing a thesis to avoiding vague and confrontational thesis statements.

"Suggestions for Developing Argumentative Essays" (Berkeley Student Learning Center)

This page offers concrete suggestions for each stage of the essay writing process, from topic selection to drafting and editing.

How to Outline your Essay

"Outlines" (Univ. of North Carolina at Chapel Hill via YouTube)

This short video tutorial from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill shows how to group your ideas into paragraphs or sections to begin the outlining process.

"Essay Outline" (Univ. of Washington Tacoma)

This two-page handout by a university professor simply defines the parts of an essay and then organizes them into an example outline.

"Types of Outlines and Samples" (Purdue OWL Online Writing Lab)

Purdue OWL gives examples of diverse outline strategies on this page, including the alphanumeric, full sentence, and decimal styles.

"Outlining" (Harvard College Writing Center)

Once you have an argument, according to this handout, there are only three steps in the outline process: generalizing, ordering, and putting it all together. Then you're ready to write!

"Writing Essays" (Plymouth Univ.)

This packet, part of Plymouth University's Learning Development series, contains descriptions and diagrams relating to the outlining process.

"How to Write A Good Argumentative Essay: Logical Structure" (Criticalthinkingtutorials.com via YouTube)

This longer video tutorial gives an overview of how to structure your essay in order to support your argument or thesis. It is part of a longer course on academic writing hosted on Udemy.

Now that you've chosen and refined your topic and created an outline, use these resources to complete the writing process. Most essays contain introductions (which articulate your thesis statement), body paragraphs, and conclusions. Transitions facilitate the flow from one paragraph to the next so that support for your thesis builds throughout the essay. Sources and citations show where you got the evidence to support your thesis, which ensures that you avoid plagiarism.

How to Write an Introduction

"Introductions" (Univ. of North Carolina Writing Center)

This page identifies the role of the introduction in any successful paper, suggests strategies for writing introductions, and warns against less effective introductions.

"How to Write A Good Introduction" (Michigan State Writing Center)

Beginning with the most common missteps in writing introductions, this guide condenses the essentials of introduction composition into seven points.

"The Introductory Paragraph" (ThoughtCo)

This blog post from academic advisor and college enrollment counselor Grace Fleming focuses on ways to grab your reader's attention at the beginning of your essay.

"Introductions and Conclusions" (Univ. of Toronto)

This guide from the University of Toronto gives advice that applies to writing both introductions and conclusions, including dos and don'ts.

"How to Write Better Essays: No One Does Introductions Properly" ( The Guardian )

This news article interviews UK professors on student essay writing; they point to introductions as the area that needs the most improvement.

How to Write a Thesis Statement

"Writing an Effective Thesis Statement" (YouTube)

This short, simple video tutorial from a college composition instructor at Tulsa Community College explains what a thesis statement is and what it does.

"Thesis Statement: Four Steps to a Great Essay" (YouTube)

This fantastic tutorial walks you through drafting a thesis, using an essay prompt on Nathaniel Hawthorne's The Scarlet Letter as an example.

"How to Write a Thesis Statement" (WikiHow)

This step-by-step guide (with pictures!) walks you through coming up with, writing, and editing a thesis statement. It invites you think of your statement as a "working thesis" that can change.

"How to Write a Thesis Statement" (Univ. of Indiana Bloomington)

Ask yourself the questions on this page, part of Indiana Bloomington's Writing Tutorial Services, when you're writing and refining your thesis statement.

"Writing Tips: Thesis Statements" (Univ. of Illinois Center for Writing Studies)

This page gives plentiful examples of good to great thesis statements, and offers questions to ask yourself when formulating a thesis statement.

How to Write Body Paragraphs

"Body Paragraph" (Brightstorm)

This module of a free online course introduces you to the components of a body paragraph. These include the topic sentence, information, evidence, and analysis.

"Strong Body Paragraphs" (Washington Univ.)

This handout from Washington's Writing and Research Center offers in-depth descriptions of the parts of a successful body paragraph.

"Guide to Paragraph Structure" (Deakin Univ.)

This handout is notable for color-coding example body paragraphs to help you identify the functions various sentences perform.

"Writing Body Paragraphs" (Univ. of Minnesota Libraries)

The exercises in this section of Writing for Success will help you practice writing good body paragraphs. It includes guidance on selecting primary support for your thesis.

"The Writing Process—Body Paragraphs" (Aims Online Writing Lab)

The information and exercises on this page will familiarize you with outlining and writing body paragraphs, and includes links to more information on topic sentences and transitions.

"The Five-Paragraph Essay" (ThoughtCo)

This blog post discusses body paragraphs in the context of one of the most common academic essay types in secondary schools.

How to Use Transitions

"Transitions" (Univ. of North Carolina Writing Center)

This page from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill explains what a transition is, and how to know if you need to improve your transitions.

"Using Transitions Effectively" (Washington Univ.)

This handout defines transitions, offers tips for using them, and contains a useful list of common transitional words and phrases grouped by function.

"Transitions" (Aims Online Writing Lab)

This page compares paragraphs without transitions to paragraphs with transitions, and in doing so shows how important these connective words and phrases are.

"Transitions in Academic Essays" (Scribbr)

This page lists four techniques that will help you make sure your reader follows your train of thought, including grouping similar information and using transition words.

"Transitions" (El Paso Community College)

This handout shows example transitions within paragraphs for context, and explains how transitions improve your essay's flow and voice.

"Make Your Paragraphs Flow to Improve Writing" (ThoughtCo)

This blog post, another from academic advisor and college enrollment counselor Grace Fleming, talks about transitions and other strategies to improve your essay's overall flow.

"Transition Words" (smartwords.org)

This handy word bank will help you find transition words when you're feeling stuck. It's grouped by the transition's function, whether that is to show agreement, opposition, condition, or consequence.

How to Write a Conclusion

"Parts of An Essay: Conclusions" (Brightstorm)

This module of a free online course explains how to conclude an academic essay. It suggests thinking about the "3Rs": return to hook, restate your thesis, and relate to the reader.

"Essay Conclusions" (Univ. of Maryland University College)

This overview of the academic essay conclusion contains helpful examples and links to further resources for writing good conclusions.

"How to End An Essay" (WikiHow)

This step-by-step guide (with pictures!) by an English Ph.D. walks you through writing a conclusion, from brainstorming to ending with a flourish.

"Ending the Essay: Conclusions" (Harvard College Writing Center)

This page collates useful strategies for writing an effective conclusion, and reminds you to "close the discussion without closing it off" to further conversation.

How to Include Sources and Citations

"Research and Citation Resources" (Purdue OWL Online Writing Lab)

Purdue OWL streamlines information about the three most common referencing styles (MLA, Chicago, and APA) and provides examples of how to cite different resources in each system.

EasyBib: Free Bibliography Generator

This online tool allows you to input information about your source and automatically generate citations in any style. Be sure to select your resource type before clicking the "cite it" button.

CitationMachine

Like EasyBib, this online tool allows you to input information about your source and automatically generate citations in any style.

Modern Language Association Handbook (MLA)

Here, you'll find the definitive and up-to-date record of MLA referencing rules. Order through the link above, or check to see if your library has a copy.

Chicago Manual of Style

Here, you'll find the definitive and up-to-date record of Chicago referencing rules. You can take a look at the table of contents, then choose to subscribe or start a free trial.

How to Avoid Plagiarism

"What is Plagiarism?" (plagiarism.org)

This nonprofit website contains numerous resources for identifying and avoiding plagiarism, and reminds you that even common activities like copying images from another website to your own site may constitute plagiarism.

"Plagiarism" (University of Oxford)

This interactive page from the University of Oxford helps you check for plagiarism in your work, making it clear how to avoid citing another person's work without full acknowledgement.

"Avoiding Plagiarism" (MIT Comparative Media Studies)

This quick guide explains what plagiarism is, what its consequences are, and how to avoid it. It starts by defining three words—quotation, paraphrase, and summary—that all constitute citation.

"Harvard Guide to Using Sources" (Harvard Extension School)

This comprehensive website from Harvard brings together articles, videos, and handouts about referencing, citation, and plagiarism.

Grammarly contains tons of helpful grammar and writing resources, including a free tool to automatically scan your essay to check for close affinities to published work.

Noplag is another popular online tool that automatically scans your essay to check for signs of plagiarism. Simply copy and paste your essay into the box and click "start checking."

Once you've written your essay, you'll want to edit (improve content), proofread (check for spelling and grammar mistakes), and finalize your work until you're ready to hand it in. This section brings together tips and resources for navigating the editing process.

"Writing a First Draft" (Academic Help)

This is an introduction to the drafting process from the site Academic Help, with tips for getting your ideas on paper before editing begins.

"Editing and Proofreading" (Univ. of North Carolina Writing Center)

This page provides general strategies for revising your writing. They've intentionally left seven errors in the handout, to give you practice in spotting them.

"How to Proofread Effectively" (ThoughtCo)

This article from ThoughtCo, along with those linked at the bottom, help describe common mistakes to check for when proofreading.

"7 Simple Edits That Make Your Writing 100% More Powerful" (SmartBlogger)

This blog post emphasizes the importance of powerful, concise language, and reminds you that even your personal writing heroes create clunky first drafts.

"Editing Tips for Effective Writing" (Univ. of Pennsylvania)

On this page from Penn's International Relations department, you'll find tips for effective prose, errors to watch out for, and reminders about formatting.

"Editing the Essay" (Harvard College Writing Center)

This article, the first of two parts, gives you applicable strategies for the editing process. It suggests reading your essay aloud, removing any jargon, and being unafraid to remove even "dazzling" sentences that don't belong.

"Guide to Editing and Proofreading" (Oxford Learning Institute)

This handout from Oxford covers the basics of editing and proofreading, and reminds you that neither task should be rushed.

In addition to plagiarism-checkers, Grammarly has a plug-in for your web browser that checks your writing for common mistakes.

After you've prepared, written, and edited your essay, you might want to share it outside the classroom. This section alerts you to print and web opportunities to share your essays with the wider world, from online writing communities and blogs to published journals geared toward young writers.

Sharing Your Essays Online

Go Teen Writers

Go Teen Writers is an online community for writers aged 13 - 19. It was founded by Stephanie Morrill, an author of contemporary young adult novels.

Tumblr is a blogging website where you can share your writing and interact with other writers online. It's easy to add photos, links, audio, and video components.

Writersky provides an online platform for publishing and reading other youth writers' work. Its current content is mostly devoted to fiction.

Publishing Your Essays Online

This teen literary journal publishes in print, on the web, and (more frequently), on a blog. It is committed to ensuring that "teens see their authentic experience reflected on its pages."

The Matador Review

This youth writing platform celebrates "alternative," unconventional writing. The link above will take you directly to the site's "submissions" page.

Teen Ink has a website, monthly newsprint magazine, and quarterly poetry magazine promoting the work of young writers.

The largest online reading platform, Wattpad enables you to publish your work and read others' work. Its inline commenting feature allows you to share thoughts as you read along.

Publishing Your Essays in Print

Canvas Teen Literary Journal

This quarterly literary magazine is published for young writers by young writers. They accept many kinds of writing, including essays.

The Claremont Review

This biannual international magazine, first published in 1992, publishes poetry, essays, and short stories from writers aged 13 - 19.

Skipping Stones

This young writers magazine, founded in 1988, celebrates themes relating to ecological and cultural diversity. It publishes poems, photos, articles, and stories.

The Telling Room

This nonprofit writing center based in Maine publishes children's work on their website and in book form. The link above directs you to the site's submissions page.

Essay Contests

Scholastic Arts and Writing Awards

This prestigious international writing contest for students in grades 7 - 12 has been committed to "supporting the future of creativity since 1923."

Society of Professional Journalists High School Essay Contest

An annual essay contest on the theme of journalism and media, the Society of Professional Journalists High School Essay Contest awards scholarships up to $1,000.

National YoungArts Foundation

Here, you'll find information on a government-sponsored writing competition for writers aged 15 - 18. The foundation welcomes submissions of creative nonfiction, novels, scripts, poetry, short story and spoken word.

Signet Classics Student Scholarship Essay Contest

With prompts on a different literary work each year, this competition from Signet Classics awards college scholarships up to $1,000.

"The Ultimate Guide to High School Essay Contests" (CollegeVine)

See this handy guide from CollegeVine for a list of more competitions you can enter with your academic essay, from the National Council of Teachers of English Achievement Awards to the National High School Essay Contest by the U.S. Institute of Peace.

Whether you're struggling to write academic essays or you think you're a pro, there are workshops and online tools that can help you become an even better writer. Even the most seasoned writers encounter writer's block, so be proactive and look through our curated list of resources to combat this common frustration.

Online Essay-writing Classes and Workshops

"Getting Started with Essay Writing" (Coursera)

Coursera offers lots of free, high-quality online classes taught by college professors. Here's one example, taught by instructors from the University of California Irvine.

"Writing and English" (Brightstorm)

Brightstorm's free video lectures are easy to navigate by topic. This unit on the parts of an essay features content on the essay hook, thesis, supporting evidence, and more.

"How to Write an Essay" (EdX)

EdX is another open online university course website with several two- to five-week courses on the essay. This one is geared toward English language learners.

Writer's Digest University

This renowned writers' website offers online workshops and interactive tutorials. The courses offered cover everything from how to get started through how to get published.

Writing.com

Signing up for this online writer's community gives you access to helpful resources as well as an international community of writers.

How to Overcome Writer's Block

"Symptoms and Cures for Writer's Block" (Purdue OWL)

Purdue OWL offers a list of signs you might have writer's block, along with ways to overcome it. Consider trying out some "invention strategies" or ways to curb writing anxiety.

"Overcoming Writer's Block: Three Tips" ( The Guardian )

These tips, geared toward academic writing specifically, are practical and effective. The authors advocate setting realistic goals, creating dedicated writing time, and participating in social writing.

"Writing Tips: Strategies for Overcoming Writer's Block" (Univ. of Illinois)

This page from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign's Center for Writing Studies acquaints you with strategies that do and do not work to overcome writer's block.

"Writer's Block" (Univ. of Toronto)

Ask yourself the questions on this page; if the answer is "yes," try out some of the article's strategies. Each question is accompanied by at least two possible solutions.

If you have essays to write but are short on ideas, this section's links to prompts, example student essays, and celebrated essays by professional writers might help. You'll find writing prompts from a variety of sources, student essays to inspire you, and a number of essay writing collections.

Essay Writing Prompts

"50 Argumentative Essay Topics" (ThoughtCo)

Take a look at this list and the others ThoughtCo has curated for different kinds of essays. As the author notes, "a number of these topics are controversial and that's the point."

"401 Prompts for Argumentative Writing" ( New York Times )

This list (and the linked lists to persuasive and narrative writing prompts), besides being impressive in length, is put together by actual high school English teachers.

"SAT Sample Essay Prompts" (College Board)

If you're a student in the U.S., your classroom essay prompts are likely modeled on the prompts in U.S. college entrance exams. Take a look at these official examples from the SAT.

"Popular College Application Essay Topics" (Princeton Review)

This page from the Princeton Review dissects recent Common Application essay topics and discusses strategies for answering them.

Example Student Essays

"501 Writing Prompts" (DePaul Univ.)

This nearly 200-page packet, compiled by the LearningExpress Skill Builder in Focus Writing Team, is stuffed with writing prompts, example essays, and commentary.

"Topics in English" (Kibin)

Kibin is a for-pay essay help website, but its example essays (organized by topic) are available for free. You'll find essays on everything from A Christmas Carol to perseverance.

"Student Writing Models" (Thoughtful Learning)

Thoughtful Learning, a website that offers a variety of teaching materials, provides sample student essays on various topics and organizes them by grade level.

"Five-Paragraph Essay" (ThoughtCo)

In this blog post by a former professor of English and rhetoric, ThoughtCo brings together examples of five-paragraph essays and commentary on the form.

The Best Essay Writing Collections

The Best American Essays of the Century by Joyce Carol Oates (Amazon)

This collection of American essays spanning the twentieth century was compiled by award winning author and Princeton professor Joyce Carol Oates.

The Best American Essays 2017 by Leslie Jamison (Amazon)

Leslie Jamison, the celebrated author of essay collection The Empathy Exams , collects recent, high-profile essays into a single volume.

The Art of the Personal Essay by Phillip Lopate (Amazon)

Documentary writer Phillip Lopate curates this historical overview of the personal essay's development, from the classical era to the present.

The White Album by Joan Didion (Amazon)

This seminal essay collection was authored by one of the most acclaimed personal essayists of all time, American journalist Joan Didion.

Consider the Lobster by David Foster Wallace (Amazon)

Read this famous essay collection by David Foster Wallace, who is known for his experimentation with the essay form. He pushed the boundaries of personal essay, reportage, and political polemic.

"50 Successful Harvard Application Essays" (Staff of the The Harvard Crimson )

If you're looking for examples of exceptional college application essays, this volume from Harvard's daily student newspaper is one of the best collections on the market.

Are you an instructor looking for the best resources for teaching essay writing? This section contains resources for developing in-class activities and student homework assignments. You'll find content from both well-known university writing centers and online writing labs.

Essay Writing Classroom Activities for Students

"In-class Writing Exercises" (Univ. of North Carolina Writing Center)

This page lists exercises related to brainstorming, organizing, drafting, and revising. It also contains suggestions for how to implement the suggested exercises.

"Teaching with Writing" (Univ. of Minnesota Center for Writing)

Instructions and encouragement for using "freewriting," one-minute papers, logbooks, and other write-to-learn activities in the classroom can be found here.

"Writing Worksheets" (Berkeley Student Learning Center)

Berkeley offers this bank of writing worksheets to use in class. They are nested under headings for "Prewriting," "Revision," "Research Papers" and more.

"Using Sources and Avoiding Plagiarism" (DePaul University)

Use these activities and worksheets from DePaul's Teaching Commons when instructing students on proper academic citation practices.

Essay Writing Homework Activities for Students

"Grammar and Punctuation Exercises" (Aims Online Writing Lab)

These five interactive online activities allow students to practice editing and proofreading. They'll hone their skills in correcting comma splices and run-ons, identifying fragments, using correct pronoun agreement, and comma usage.

"Student Interactives" (Read Write Think)

Read Write Think hosts interactive tools, games, and videos for developing writing skills. They can practice organizing and summarizing, writing poetry, and developing lines of inquiry and analysis.

This free website offers writing and grammar activities for all grade levels. The lessons are designed to be used both for large classes and smaller groups.

"Writing Activities and Lessons for Every Grade" (Education World)

Education World's page on writing activities and lessons links you to more free, online resources for learning how to "W.R.I.T.E.": write, revise, inform, think, and edit.

- PDFs for all 136 Lit Terms we cover

- Downloads of 1929 LitCharts Lit Guides

- Teacher Editions for every Lit Guide

- Explanations and citation info for 40,694 quotes across 1929 books

- Downloadable (PDF) line-by-line translations of every Shakespeare play

Need something? Request a new guide .

How can we improve? Share feedback .

LitCharts is hiring!

Write a University Essay

What are the parts of an essay, how do i write an introduction, how do i write the body of my essay, how do i write the conclusion, how do i create a reference list, how do i improve my essay.

- Improving your writing

Ask Us: Chat, email, visit or call

More help: Writing

- Book Writing Appointments Get help on your writing assignments.

- Introduction

- Each is made up of one or several paragraphs.

- The purpose of this section is to introduce the topic and why it matters, identify the specific focus of the paper, and indicate how the paper will be organized.

- To keep from being too broad or vague, try to incorporate a keyword from your title in the first sentence.

- For example, you might tell readers that the issue is part of an important debate or provide a statistic explaining how many people are affected.

- Defining your terms is particularly important if there are several possible meanings or interpretations of the term.

- Try to frame this as a statement of your focus. This is also known as a purpose statement, thesis argument, or hypothesis.

- The purpose of this section is to provide information and arguments that follow logically from the main point you identified in your introduction.

- Identify the main ideas that support and develop your paper’s main point.

- For longer essays, you may be required to use subheadings to label your sections.

- Point: Provide a topic sentence that identifies the topic of the paragraph.

- Proof: Give evidence or examples that develop and explain the topic (e.g., these may come from your sources).

- Significance: Conclude the paragraph with sentence that tells the reader how your paragraph supports the main point of your essay.

- The purpose of this section is to summarize the main points of the essay and identify the broader significance of the topic or issue.

- Remind the reader of the main point of your essay (without restating it word-for-word).

- Summarize the key ideas that supported your main point. (Note: No new information or evidence should be introduced in the conclusion.)

- Suggest next steps, future research, or recommendations.

- Answer the question “Why should readers care?” (implications, significance).

- Find out what style guide you are required to follow (e.g., APA, MLA, Chicago) and follow the guidelines to create a reference list (may be called a bibliography or works cited).

- Be sure to include citations in the text when you refer to sources within your essay.

- Cite Your Sources - University of Guelph

- Read assignment instructions carefully and refer to them throughout the writing process.

- e.g., describe, evaluate, analyze, explain, argue, trace, outline, synthesize, compare, contrast, critique.

- For longer essays, you may find it helpful to work on a section at a time, approaching each section as a “mini-essay.”

- Make sure every paragraph, example, and sentence directly supports your main point.

- Aim for 5-8 sentences or ¾ page.

- Visit your instructor or TA during office hours to talk about your approach to the assignment.

- Leave yourself time to revise your essay before submitting.

- << Previous: Start Here

- Next: Improving your writing >>

- Last Updated: Oct 27, 2022 10:28 AM

- URL: https://guides.lib.uoguelph.ca/UniversityEssays

Suggest an edit to this guide

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Advanced notice: this website will be temporarily unavailable on Sunday 26 May between 10am - 12pm and 1pm - 3pm BST whilst maintenance work is being undertaken.

Basic essay structure

Improve your writing

Organise your essays to demonstrate your knowledge, show your research and support your arguments

Essays are usually written in continuous, flowing, paragraphed text and don’t use section headings. This may seem unstructured at first, but good essays are carefully structured.

How your assignment content is structured is your choice. Use the basic pattern below to get started.

Essay structure

An essay consists of three basic parts:, introduction.

The essay itself usually has no section headings. Only the title page, author declaration and reference list are written as headings, along with, for example, appendices. Check any task instructions, and your course or unit handbook, for further details.

Content in assignment introductions can vary widely. In some disciplines you may need to provide a full background and context, whereas other essays may need only a little context, and others may need none.

An introduction to an essay usually has three primary purposes:

- To set the scene

- To tell readers what is important, and why

- To tell the reader what the essay is going to do (signposting)

A standard introduction includes the following five elements:

- A statement that sets out the topic and engages the reader.

- The background and context of the topic.

- Any important definitions, integrated into your text as appropriate.

- An outline of the key points, topic, issues, evidence, ideas, arguments, models, theories, or other information, as appropriate. This may include distinctions or contrasts between different ideas or evidence.

- A final sentence or two which tells the reader your focal points and aims.

You should aim to restrict your introduction to information needed for the topic and only include background and contextual information which helps the reader understand it, or sets the scene for your chosen focal points.

In most essays you will have a considerable range of options for your focus. You will be expected to demonstrate your ability to select the most relevant content to address your focal points.

There are some exceptions. For example, if an assignment brief specifically directs the essay focus or requires you to write broadly about a topic. These are relatively rare or are discipline-specific so you should check your task instructions and discipline and subject area conventions.

Below are examples of an opening statement, a summary of the selected content, and a statement at the end of the introduction which tells the reader what the essay will focus on and how it will be addressed. We've use a fictional essay.

The title of our essay is: 'Cats are better than dogs. Discuss.'

To submit this essay you also would need to add citations as appropriate.

Example of opening statements:

People have shared their lives with cats and dogs for millenia. Which is better depends partly on each animal’s characteristics and partly on the owner’s preferences.

Here is a summary of five specific topics selected for the essay, which would be covered in a little more detail in the introduction:

- In ancient Egypt, cats were treated as sacred and were pampered companions.

- Dogs have for centuries been used for hunting and to guard property. There are many types of working dog, and both dogs and cats are now kept purely as pets.

- They are very different animals, with different care needs, traits and abilities.

- It is a common perception that people are either “cat-lovers” or “dog-lovers”.

- It is a common perception that people tend to have preferences for one, and negative beliefs about and attitudes towards, the other.

Example of closing statements at the end of the introduction:

This essay will examine both cats’ and dogs’ behaviour and abilities, the benefits of keeping them as pets, and whether people’s perceptions of their nature matches current knowledge and understanding.

Main body: paragraphs

The body of the essay should be organised into paragraphs. Each paragraph should deal with a different aspect of the issue, but they should also link in some way to those that precede and follow it. This is not an easy thing to get right, even for experienced writers, partly because there are many ways to successfully structure and use paragraphs. There is no perfect paragraph template.

The theme or topic statement

The first sentence, or sometimes two, tells the reader what the paragraph is going to cover. It may either:

- Begin a new point or topic, or

- Follow on from the previous paragraph, but with a different focus or go into more-specific detail. If this is the case, it should clearly link to the previous paragraph.

The last sentence

It should be clear if the point has come to an end, or if it continues in the next paragraph.

Here is a brief example of flow between two summarised paragraphs which cover the historical perspective:

It is known from hieroglyphs that the Ancient Egyptians believed that cats were sacred. They were also held in high regard, as suggested by their being found mummified and entombed with their owners (Smith, 1969). In addition, cats are portrayed aiding hunters. Therefore, they were both treated as sacred, and were used as intelligent working companions. However, today they are almost entirely owned as pets.

In contrast, dogs have not been regarded as sacred, but they have for centuries been widely used for hunting in Europe. This developed over time and eventually they became domesticated and accepted as pets. Today, they are seen as loyal, loving and protective members of the family, and are widely used as working dogs.

There is never any new information in a conclusion.

The conclusion usually does three things:

- Reminds your readers of what the essay was meant to do.

- Provides an answer, where possible, to the title.

- Reminds your reader how you reached that answer.

The conclusion should usually occupy just one paragraph. It draws together all the key elements of your essay, so you do not need to repeat the fine detail unless you are highlighting something.

A conclusion to our essay about cats and dogs is given below:

Both cats and dogs have been highly-valued for millenia, are affectionate and beneficial to their owners’ wellbeing. However, they are very different animals and each is 'better' than the other regarding care needs and natural traits. Dogs need regular training and exercise but many owners do not train or exercise them enough, resulting in bad behaviour. They also need to be 'boarded' if the owner is away and to have frequent baths to prevent bad odours. In contrast, cats do not need this level of effort and care. Dogs are seen as more intelligent, loyal and attuned to human beings, whereas cats are perceived as aloof and solitary, and as only seeking affection when they want to be fed. However, recent studies have shown that cats are affectionate and loyal and more intelligent than dogs, but it is less obvious and useful. There are, for example, no 'police' or 'assistance' cats, in part because they do not have the kinds of natural instincts which make dogs easy to train. Therefore, which animal is better depends upon personal preference and whether they are required to work. Therefore, although dogs are better as working animals, cats are easier, better pets.

Download our basic essay structure revision sheet

Download this page as a PDF for your essay structure revision notes

Better Essays: Signposting

Paragraphs main body of an assessment

Academic Writing

- Introduction

- Planning an Essay

- Basic Essay Structure

Writing an Essay

- Writing Paragraghs

- Plagiarism This link opens in a new window

Basic academic essays have three main parts:

- introduction

- Video Explanation

Writing an Introduction

- Section One is a neutral sentence that will engage the reader’s interest in your essay.

- Section Two picks up the topic you are writing about by identifying the issues that you are going to explore.

- Section Three is an indication of how the question will be answered. Give a brief outline of how you will deal with each issue, and in which order.

An introduction generally does three things. The first section is usually a general comment that shows the reader why the topic is important, gets their interest, and leads them into the topic. It isn’t actually part of your argument. The next section of the introduction is the thesis statement . This is your response to the question; your final answer. It is probably the most important part of the introduction. Finally, the last section of an introduction tells the reader what they can expect in the essay body. This is where you briefly outline your arguments .

Here is an example of the introduction to the question - Discuss how media can influence children. Use specific examples to support your view.

Writing Body Paragraphs

- The topic sentence introduces the topic of your paragraph.

- The sentences that follow the topic sentence will develop and support the central idea of your topic.

- The concluding sentence of your paragraph restates the idea expressed in the topic sentence.

The essay body itself is organized into paragraphs, according to your plan. Remember that each paragraph focuses on one idea, or aspect of your topic, and should contain at least 4-5 sentences so you can deal with that idea properly.

Each body paragraph has three sections. First is the topic sentence . This lets the reader know what the paragraph is going to be about and the main point it will make. It gives the paragraph’s point straight away. Next, come the supporting sentences , which expand on the central idea, explaining it in more detail, exploring what it means, and of course giving the evidence and argument that back it up. This is where you use your research to support your argument. Then there is a concluding sentence . This restates the idea in the topic sentence, to remind the reader of your main point. It also shows how that point helps answer the question.

Writing a Conclusion

- Re-read your introduction – this information will need to be restated in your conclusion emphasizing what you have proven and how you have proven it.

- Begin by summarizing your main arguments and restating your thesis ; e.g. "This essay has considered….."

- State your general conclusions, explaining why these are important.

- The final sentences should draw together the evidence you have presented in the body of the essay to restate your conclusion in an interesting way (use a transitional word to get you started e.g. Overall, Therefore).

The last section of an academic essay is the conclusion. The conclusion should reaffirm your answer to the question, and briefly summarize key arguments. It does not include any new points or new information.

A conclusion has three sections. First, repeat the thesis statement . It won’t use the exact same words as in your introduction, but it will repeat the point: your overall answer to the question based on your arguments. Then set out your general conclusions , and a short explanation of why they are important. Finally, draw together the question, the evidence in the essay body, and the conclusion. This way the reader knows that you have understood and answered the question. This part needs to be clear and concise.

- << Previous: Planning an Essay

- Next: Writing Paragraghs >>

- Last Updated: Oct 3, 2023 11:15 AM

- URL: https://bcsmn.libguides.com/Academic_Writing

Learn foreign languages

How to Write an Essay: Step by Step Guide With Examples

An essay is a brief writing that explains, analyzes and interprets a topic; it’s a summary of a particular topic in which the author also expresses an opinion.

The essay is a very useful, practical and simple learning and expression tool and it has rules, specifications or details regarding its format and content you must know to be able to do it correctly. Some of the most frequent questions about the essay are:

Does the essay need a title? How many paragraphs does an essay have? Does it have headings and a conclusion? Does the essay have a full stop? Are the introduction, body and conclusion on separate pages? How do you make the cover of an essay?

Those are some of the various questions that come up when you need to do an essay, all of which are addressed here.

Table of Contents

What is an essay.

An essay is a short writing that explains, analyzes, and interprets a topic. It is an explanatory and analytical summary of a specific topic, where the author not only exposes or explains the subject but also, based on solid information, expresses an opinion on it.

The difference between an essay and the informational text you can see everywhere, is that an essay is freer, and its parts are not separated by headings.

The format of an essay and most common doubts

The format of an essay refers to the arrangement or location of each of its parts; it is the order of its components that is visually perceived and that gives the essay better appearance and organization.

This is done according to the APA format and it’s norms are the ones that are below

- Font: Arial or Times New Roman, number 12.

- Leading: Leading is the vertical space between each line and must be 1.5.

- Margins : 2.54 cm lower, upper and right margins.

- The text must always be justified , that a text is justified means that the lines have to be aligned, so they create the shape of a square. However, there can be cases when this can’t be achieved, like when you write a list.

- The headings “Introduction”, “Body” and “Conclusion ” are not written in the essay. They essay is written continuously, and you should avoid placing such headings.

The essay does have each of these parts but they are not identified as in a monographic work, but rather they are written one after another. An example of an essay can be seen at the end of this article.

- Full stop. The essays do have a full stop, after each paragraph.

- Paragraphs : An essay needs to have at least 5 paragraphs, and each paragraph must have a minimum of 3 lines and a maximum of 10 lines.

The parts or structure of an essay

The structural organization of an essay comprises three fundamental parts:

- Introduction.

- Conclusion.

The introduction

The introduction, as its name implies, introduces the reader to the essay with following steps:

- Expression of a general idea. It consists of expressing a broad or macro idea of the topic, for example, if an essay is going to be about a type of personal pronoun , it begins with the definition of pronoun. Or, if it’s about a sport like soccer, it begins with the definition of sport.

- Indication of a less general idea. The topic begins to be reduced and concentrated. For example, after having defined what a sport is, it is mentioned that there are many sports and one of them is soccer and present a definition of soccer.

- Indication of an update . The purpose is to locate the essay in time and space, that is, in the historical moment and / or geographical location where it has context. If you talk about human rights violations , here you write about the violations that are currently taking place and the geographical place of interest where they take place.

- An exemplification . Here you could write cases in which human rights have been violated.

- Presentation of the problem, topic, question, this will depend on the type of essay . The most common essay that is frequently assigned to students is expository, which consists of developing the topic through explanations, comparisons, and exemplifications. Here is where the fundamental idea of the essay is located and that is placed last.

The body of the essay

The body consists of the points that develop the essay in depth. In the example of the essay about soccer, the body could have the history of soccer, the rules of the game, the most important championships, etc

Form and organization the body

- Each topic should be covered in a separate paragraph.

- Each topic, preferably, should be introduced by a connector (Regarding… As regard… With respect to…)

- The development must contain more information than the introduction and conclusion because it constitutes the detailed information of the essay.

The conclusion

- The conclusion is preferably written in a single paragraph, and it is also preferred that it be the same or similar in size to that of the introduction. It starts with a connector (To finish…. In conclusion…)

- There should be a mention of one or two topics covered in the body.

Here goes the author’s personal opinion, (You, the person doing the essay, your opinion) an essay has, of course, personal opinions in its body, however, in the conclusion these must be emphatic.

To make it clear that the author is giving his or her opinion, he or she can use phrases such as “In my opinion…” “I think…” “I hold that …” “From my perspective … etc.

In the last part, you write what you think about the subject, if it’s a typical expository essay. What appears here depends on the type of essay, it can be the answer to the question, or the solution of the problem as the case may be.

- References go in a separate page that starts with the heading “References”. Add only those that have been cited, not the texts you read to do the essay.

- References must be placed in alphabetical order and according to APA standards.

Example of references

Savater, F. (1991). Ética para Amador. Barcelona: Ariel.

Thomas, Ann and Aron Thomas, Jr. (1956 ). Non-intervention: The law and its import in the Americas . Dallas, Texas: Southern Methodist University Press.

Transtle. (2022). How to Write an Essay: The Ultimate Step by Step Guide. Transtle . Available: https://www.transtle.com/general-learning/how-to-write-an-essay/ [Consulted: 2022, January 24th].

Walzer, M. (2000). Just and Unjust Wars: A Moral Argument with Historical Illustrations. (3rd edn.). New York: Basic Books.

Example of an essay

Text in the essay from: Mundanopedia.com

To revisit this article, visit My Profile, then View saved stories .

SOS! My Wedding Is 3 Months Away and I Still Don’t Have a Dress

By Nicole Kliest

As I type this, it’s been four weeks and five days since I first developed an eyelid twitch. After misdiagnosing myself with Bell’s palsy and then a stroke, my friend’s husband, an actual optometrist, reported back that it was probably just Myokymia brought on by stress. (“Everyone in New York City is stressed—plus, you’re planning a wedding.”) So for the last 33 days, whenever I have a conversation that lasts longer than 60 seconds—the approximate cadence in between spasms—I abruptly look away or tap the corner of my eye as though I am deep in thought, when really I’m just tamping down my fluttering anxiety.

I never wanted to be the person who penned a personal essay about wedding stress. To toot my own horn here for a brief moment: the consistent piece of feedback I receive from friends and acquaintances that makes me feel good about myself is that I am a so-called ‘chill’ person. A trait that living in New York City for nearly a decade has surely started to chisel away at, but nonetheless a core component of my personality that I cling to. Right now, though, there is a question that sends me into an uncharacteristic, decidedly not chill panic: have you found a dress yet?

I’m aware—world’s tiniest violin—that finding a wedding dress can be stressful. I’m not winning any sympathy or novelty awards here. But when confronted with the pressure to encapsulate your entire essence into one single dress, how can one possibly choose? I want to express a multitude of emotions that somehow feel in conflict with each other when distilled into clothing form. Sexy but soft, whimsical but practical, sleek yet complex… buying a wedding dress feels like a torturous practice in self-expression, one in which you must pigeonhole yourself into what type of bride you are and are not. Am I a Cecilie Bahnsen ballerina bride? Perhaps a bow-bedecked Sandy Liang lady? An elegant Khaite woman? A bold Bernadette character? Maybe even a Molly Goddard muse? Honestly—all of the above!

At the risk of sounding hokey, I had hoped a dress that embodied the unique facets of my personality would emerge. A tendency to buck tradition, quietly creative, a little bit romantic, not too dramatic, and with a predilection for nostalgia. But as I continue my search, no garment hits all the marks.

Of course, I could just cease my whining, pick a dress, and be done with it. But there’s the rub—I haven’t. I can’t? I can’t! In waiting for the one to grace my laptop screen and sweep me off my feet, I’ve managed to find myself three months out from my wedding with absolutely nothing to wear. (Save for the pair of Neous strappy heels that I chose a month after getting engaged. No brainer there!)

Conventional bridal rule of thumb says you should purchase your wedding dress eight to nine months out from your wedding. I got engaged in March of 2023 and will wed in August of this year, which gave me ample time to sort it out. But as timeline markers came—and went—I began to realize there was an issue. At this point, if I even stepped foot inside a bridal salon, I presume my three-month deadline would give the team a conniption.

And this isn’t procrastination, dear reader, I’ve been looking consistently for over a year now to no avail. On one recent day when my bum eye was experiencing a particularly furious set of twitches and I had to return yet another dress to UPS that didn’t work out, I did something out of character: I took to Instagram. “Do I know any other brides who put off buying their dress til the last minute because they can’t find anything they like? Just me?” The responses flooded in almost immediately.

“Literally me. Didn’t have my dress until two weeks before the day.”

“Omg yes and then everything was like ‘you need to order three months in advance’ and I was like my wedding is in 30 days…”

“I picked my shoes the night before.”

“I got something cheap and ended up tailoring it to my needs because I couldn’t find what I wanted.”

“I ordered a dress four days before my wedding that a friend picked out for me.”

“Yes. Super overwhelming. Two weeks before my wedding I wound up getting a sundress for $65 at a little shop at the end of the street. I’m still fine with the decision and I still have the dress after 13 years of marriage.”

“That was me! I got mine the month before.”

By Hayley Maitland

By Deanna Pai

By Hannah Jackson

I was not alone in my mercurial attitude toward wedding dresses, so it seemed. Through a haphazard Instagram poll, I had unearthed a community of individuals who experienced similar struggles, and in doing so, felt a wave of relief, albeit fleeting. (I still need something to wear, lest we forget.)

I wouldn’t blame you for writing this kind of conundrum off as vapid. I get it—if your main problem in life is that you cannot find a wedding dress, you’ve got it pretty good. But it isn’t my main problem. It’s just one I didn’t expect I’d be dealing with. And one that, truly, very few brides talk about. I’ve heard countless tales of trying on that one mystical dress and bursting into tears because they just knew it was the one. I’m still tapping my foot for that epiphany to arrive.

Lamenting my lack of decisiveness over dinner with a friend the other evening, she responded succinctly: “It’s the dress you like in the moment.” A simple proverb, but profound enough. It’s the dress you like in the moment. Tastes evolve, silhouettes change, and as long as I like what I’m wearing in the moment, that’s fine enough.

If I look back at my wedding and look like a tulle cottagecore cupcake, so be it! The notion that a wedding dress must encapsulate who you are as a person feels antiquated. An appreciation for wearing a cute outfit surrounded by the people you love should be enough. (Something I never thought I’d need reminding of, but here we are.) Keeping this in mind, I’ll be self-imposing a deadline to choose a dress I like—in the moment—within the next few weeks. Wish me (and my eyelid) good luck.

More Great Wedding Stories in Vogue

An Exclusive Look Inside Anant Ambani and Radhika Merchant’s Lavish Pre-Wedding Weekend

The 2024 Wedding Trends That Are In—And Out

This 77-Year-Old Bride Wore a Custom Attersee Suit for Her Manhattan Wedding Celebration

How Much to Spend on a Wedding Gift, According to Experts

The Best Wedding Dresses for Every Bridal Moment—From the Ceremony to the After-Party

Sign up for Vogue ’s wedding newsletter , an all-access invitation to the exceptional and inspirational, plus planning tips and advice

Never miss a Vogue moment and get unlimited digital access for just $2 $1 per month.

- WEATHER ALERT Flash Flood Warning Full Story

Cicada emergence begins in parts of Chicago area, mostly bugging suburbs: 'Don't be alarmed'

Cicadas have arrived in some Chicago suburbs, including Park Ridge

PARK RIDGE, Ill. (WLS) -- Cicadas have arrived in some Chicago suburbs, including Park Ridge.

They are all over the trees and the ground.

ABC7 Chicago is now streaming 24/7. Click here to watch

Residents said they started to see them come out over the weekend.

They haven't been bugging people too much, yet.

SEE MORE: ABC7 Chicago Cicada-Cast 2024 breaks down latest on Illinois emergence

The 17-year cicadas are emerging from their underground homes and covering large trees, much to the delight of children.

"I've been seeing a lot of them on the ground, doing some gardening, seeing them coming up then. And my kids are really enjoying them," Park Ridge resident Christina Cosgrove said.

Billions or even trillions of cicadas are expected, coming out from their long-time homes right now.

They're just big, dumb and ugly; there is not much you can do about it Emmy Buckley

"We are OK with them. We're animal nerds and everything, and it's just another activity for the kids to play with. So, they're catching them and putting them in their little container, and walking around in the backyard and then releasing them again," Park Ridge resident Nikki Allen said.

The 17-year and 13-year cicadas are overlapping in some areas downstate.

Show us your videos of cicadas in the Chicago area

"Soil temperatures has to be 64 degrees. So, here in Park Ridge, we've had 64 in many areas for the past three or four days. So, as the soil warms and stays consistent, they will keep popping up every day," said Joel Reiser, with Illinois Cicada Watch.

Reiser, who started the Illinois Cicada Watch Facebook group, said the emergence is ramping up quickly, and will eventually peak.

"People should know they are harmless. It's all about Mother Nature. They feed animals. They feed birds, also nutrients for the ground. Don't be alarmed. They don't bite," Reiser said.

Like the cicadas, Reiser's followers keep emerging.

"Ever since they've been here and coming out it's grown to almost 28,000 to this point right now," he said.

And there's no need for earplugs just yet. Residents said they're not loud now.

RELATED: Field Museum explains loud noise of cicada calls amid Illinois emergence

The birds have been feasting on them, and some people say they're considering the same.

"Some people were screenshotting the popcorn cicadas, and I think that's a texture that I can try. If I see it, and, if it was offered, I think I would try it, if there was a good sauce with it," Allen said.

As she whacked the weeds from her front lawn, Gail King tried to dodge the invasion.

"I'm astonished to see how much has come up," said King, a Park Ridge resident.

With dozens of holes in the soil, cicadas have come up and landed in King's trees, grass, ground and sidewalk. Park Ridge residents started noticing the red-eyed winged bugs Sunday.

"My one biggest tree, there are hundreds of them crawling up," Park Ridge resident Nancy Kwasigroch said.

But, Kwasigroch's smaller tree is being protected from the annoying critters. She and her neighbor, Kathy Meyer, are using netting to protect their trees that are 2 inches in diameter. Meyer is convinced 17 years ago, cicadas stunted the growth of another tree.

"That tree never grew really great, so wanted to protect them," Meyer said.

Some 18-year-old recent high school graduates were too young to remember the last time 17-year cicadas made an appearance. The teens are already sick of them.

"I feel like I'm crunching with every step. They are crawling. Then, you have the shells they are emerging out of: It's yucky," Park Ridge resident Ivy Suh said.

"They're just big, dumb and ugly; there is not much you can do about it," Park Ridge resident Emmy Buckley said.

The cicadas have a life cycle of about four to six weeks.

And they're likely to remain visible through June.

Some were getting a head start Monday. The insects were all over trees and headstones at a Niles cemetery.

Related Topics

2 batches of mosquitoes test positive for West Nile Virus in Illinois

Field Museum explains loud cicada noise amid emergence

ABC7 Cicada-Cast 2024 breaks down latest on IL emergence

Local bakery joins cicada buzz with cookies, cupcakes

Top stories.

High school track coach uses CPR to save student in cardiac arrest

- 26 minutes ago

Ex-MLB pitcher arrested in underage sex sting, FL sheriff says: VIDEO

- 31 minutes ago

Storms roll through Chicago area, but save strength for Tuesday

- 10 minutes ago

Philly teacher, student going viral for 'veggie dance' battle

- 42 minutes ago

Drivers caught parking on shoulder near O'Hare could soon face fines

- 2 hours ago

What's behind the weird flavors popping up on store shelves

Jose Andres gives keynote at restaurant show: 'We are anchors of hope'

Peoria Planned Parenthood reopens after 2023 firebombing attack

latest in US News

NYC's former 'hottest bachelor' Eric Schmidt, 69, spotted with...

Trump campaign plans to file lawsuit over ‘The Apprentice’...

Juneteenth proclaimed state holiday again in Alabama, after bill...

Surprise grizzly bear attack prompts closure of a mountain in...

Rudy Giuliani launches $30 'Rudy Coffee' after WABC drama,...

Mother moose kills Alaska man, 70, attempting to take photos of...

Trump's ex-fixer Michael Cohen admits stealing $60K from him...

Feds beef up Hatch Act to clamp down on political activity by...

Early memorial day forecast shows which parts of us will likely have the best weather.

- View Author Archive

- Get author RSS feed

Thanks for contacting us. We've received your submission.

It’s time to start checking the forecast for your Memorial Day weekend plans and the FOX Forecast Center has some good news for a majority of the U.S., including most of the eastern U.S. and West.

The forecast for the unofficial start of summer is especially important for the 43.8 million Americans AAA expects to travel 50 or more miles from home.

Here’s an early look at the 2024 Memorial Day forecast by region.

Northeast could be big weather winner for Memorial Day weekend

With little to no rain expected and mild temperatures, the Northeast might be the big winner for Memorial Day weekend outdoor plans.

New York is looking to be on the cooler side of the city’s past Memorial Days, with temperatures forecast in the upper 60s and mid-70s through the weekend.

Southeast stays hot and mostly dry

Hot temperatures across the Southeast are expected to stay steady, making it a good idea to include the beach or pool in your holiday weekend plans.

The current hot weather happening in Florida and Georgia will continue into next weekend.

More 90-degree days are in the forecast for Miami and Jacksonville . Meanwhile, Atlanta will be in the mid to upper 80s for the weekend.

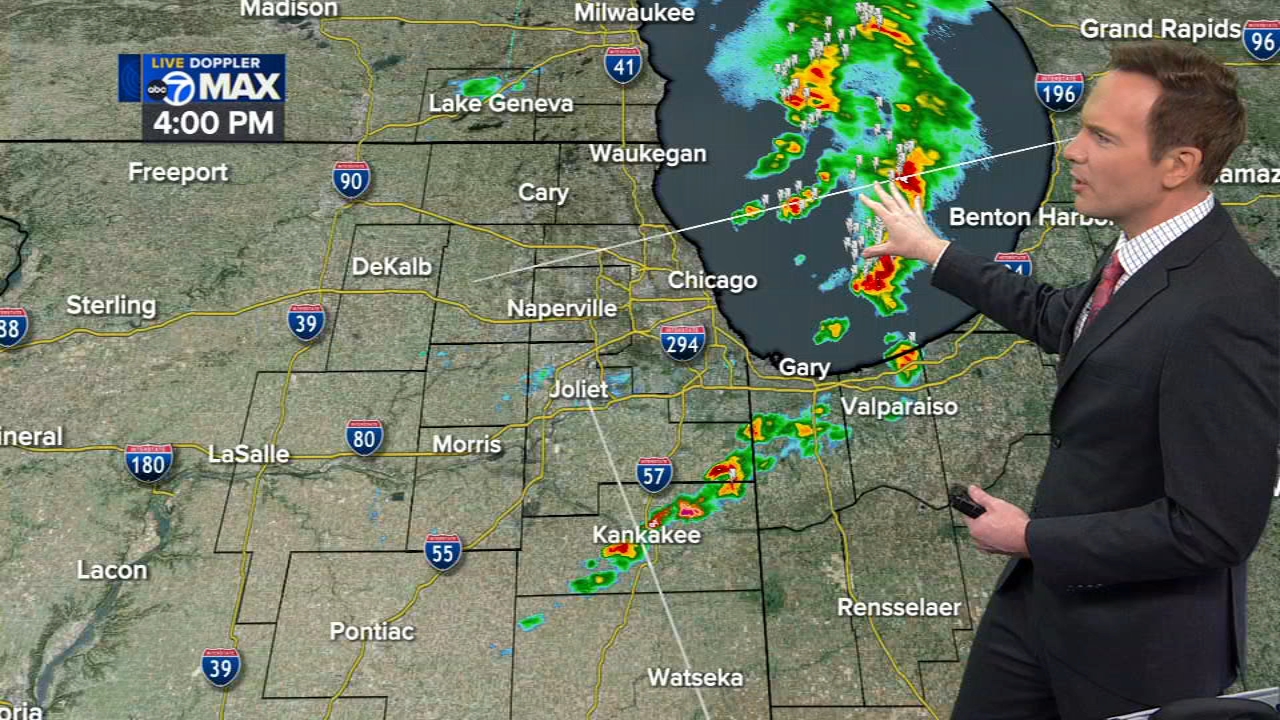

Central U.S. could once again face stormy weather

Make a backup plan for your outdoor grilling as the stormy pattern of April and May continues to grip America’s Heartland.

Ahead of next weekend, the Central U.S. is bracing for another possible derecho, which could bring extreme wind gusts and baseball-size hail. The multiday threat continues from the Plains into the Midwest through at least Tuesday.

A surge of cooler air will keep temperatures feeling springlike by the end of the workweek, and there are chances for rain.

The FOX Forecast Center is tracking a weather pattern supportive of more severe storms, that have brought tornadoes, giant hail and more damaging weather to parts of the Central U.S.

Major cities that might see thunderstorms on May 25, include Denver, St. Louis and Chicago.

Past Memorial Day weekends in Chicagoland have experienced some weather extremes, including highs topping out at 95 degrees in 2018 and 2012. This year should be milder with temperatures in the 70s.

Mild Memorial Day in the West

For the holiday weekend, Western states are more likely to experience springlike temperatures than summerlike. Thankfully, rain or snow is unlikely across the region.

Those in Southern California and New Mexico could have a beautiful weekend.

Share this article:

Advertisement

Watch CBS News

BMW, Jaguar Land Rover, VW used parts made with Chinese forced labor, Senate report finds

Updated on: May 20, 2024 / 3:51 PM EDT / AP

BMW, Volkswagen and Jaguar Land Rover have bought parts made by a Chinese company sanctioned under a 2021 law for using forced labor , a U.S. Senate investigation found, resulting in a call by lawmakers for stricter enforcement.

The automakers said in response to the Senate report released Monday that they've taken action to bring their cars into compliance with the law.

The Senate Finance Committee's two-year probe revealed that BMW imported to the U.S. at least 8,000 MINI vehicles containing parts produced by JWD after the Chinese supplier was sanctioned in December for its links to China's labor program in the far western region of Xinjiang.

The report said Jaguar Land Rover imported replacement parts including components made by JWD even after the automaker had been informed of the presence of the problematic product in its supply chain.

Volkswagen, however, disclosed to the U.S. border authorities that a shipment of its vehicles contained parts made by JWD, according to the report.