Why Science Fiction is the Best Film Genre

- Joseph Tomastik

- July 22, 2022

Science fiction has shown itself to be the best genre in film by combining the real and unreal in countless exciting and impactful ways. Here’s why.

In one way or another, everyone has had at least some exposure and experience with the science fiction genre. It’s pretty much impossible for someone to avoid it with how much it’s ingrained itself into our popular culture across every medium of art, from centuries-old texts to modern films. Some people may say they’re not fans of science fiction or even dismiss it as nothing more than a gimmick, but I think they’d be hard-pressed to look deeply into their history with entertainment and not find something in the genre that left a meaningful impact on them. I’ve definitely had more than a few such instances … so much so that, for years, I’ve considered science fiction to be the best genre of storytelling, particularly in film . If I were to list my favorite films of all time, science fiction would be the most common type to pop up. It’s inspired my imagination in a variety of ways from childhood through adulthood, and it allows for seemingly endless possibilities that fall nicely into the sweet spot of my personal tastes in media.

So, I want to celebrate science fiction by exploring what defines it, what makes it so special to me, and why I think it’s the best film genre that’s just as important and relevant now as it’s ever been!

WHAT DEFINES SCIENCE FICTION?

First, it’s best to properly establish what I consider to define science fiction as a genre. Science fiction is exactly that: science and fiction. It’s taking the setting, rules, and science of our real world and, to varying degrees, adding some sort of fictional spin to them. It’s not completely driven by undisputed fact, but it’s also not based entirely on the ideas of the artists. I think that, for something to be science fiction, the starting point of its conception has to be pure reality. The environment, history, and rules of the story all need to be rooted in what we know without question to be fact in our world. So, films like Star Wars or Dune don’t count in my eyes, as their universes are pretty much designed completely from the ground up, making them pure fantasy. The best way I can think to succinctly put it is that science fiction injects something fictional into reality , rather than having reality be put into something fictional.

Once those ground rules are defined, that’s when the fiction comes into play, able to be implemented in any number of ways. You can bring in one or two elements that haven’t been proven to exist in our universe yet, like time travel or intelligent alien life. You can have the story take place in the future with multiple technological innovations that we’ve yet to experience and may never see. You can take some known natural occurrence and distort or twist it around, or have the setting be an alternate reality with a few select changes while everything else is true to our world.

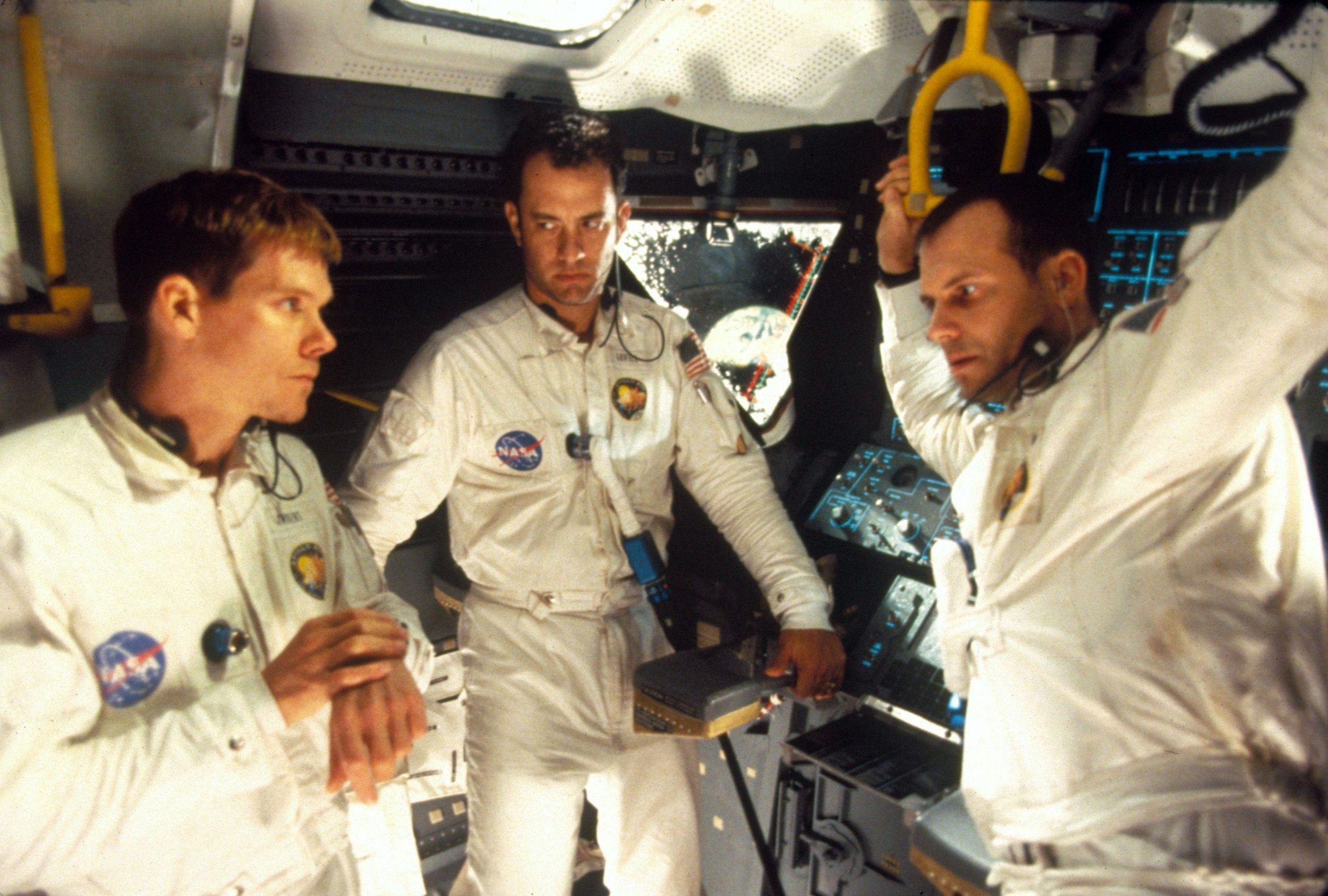

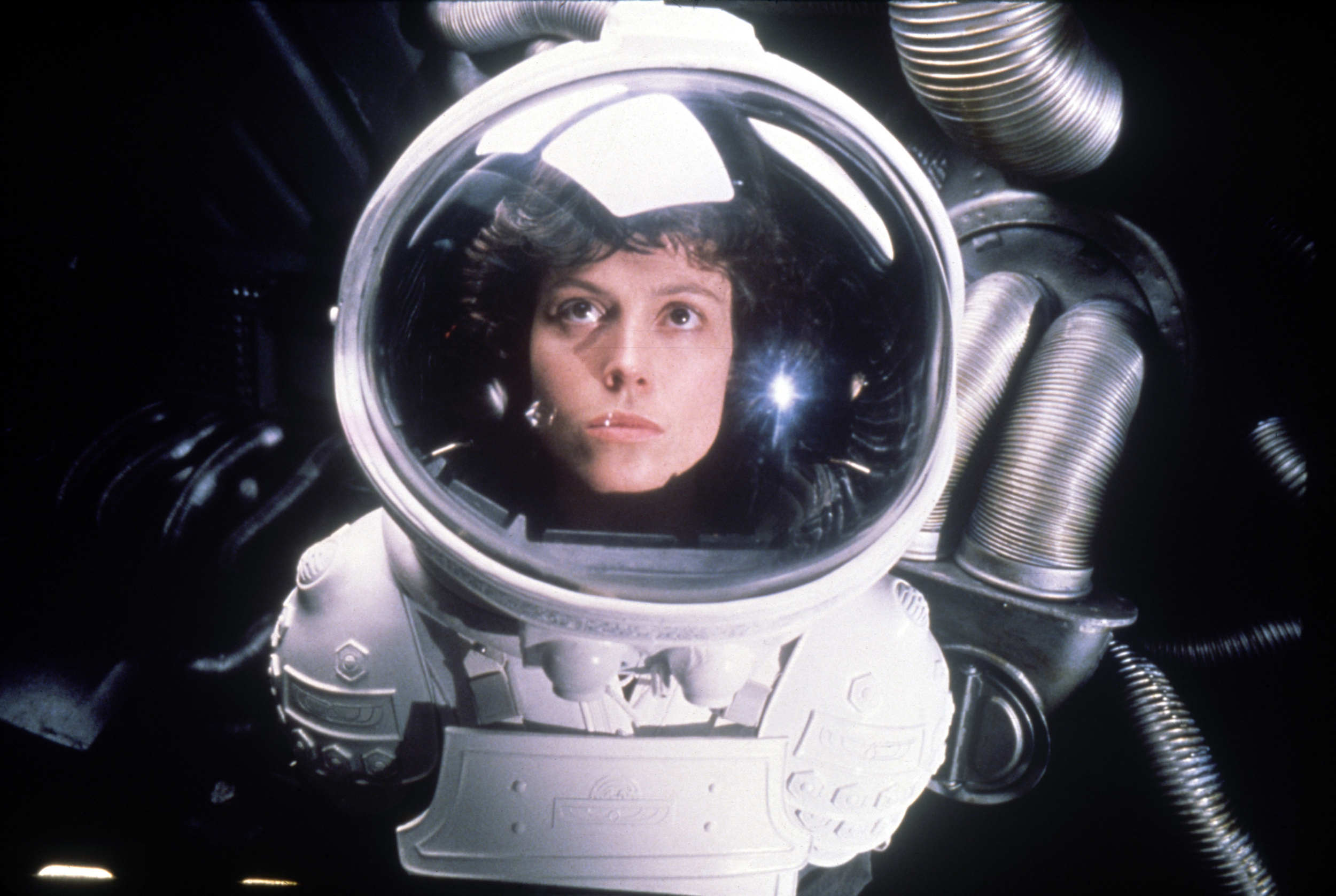

Additionally, all of those changes to reality should have at least some basis in pre-defined scientific concepts . This is why certain horror films like Annihilation and Alien , for instance, can also count as science fiction, as their horror elements are consistently linked to scientific and biological phenomena like cellular alterations and extraterrestrial life, whereas other horror films like The Conjuring or Hereditary don’t count because their fictional aspects are rooted solely in the supernatural. Like a lot of genres, the line can be blurry at times, but these are the criteria as I’ve come to accept them.

THE BEST OF BOTH WORLDS: BALANCING SCIENCE AND FICTION

So, what is it about science fiction that makes its appeal so instant and long-lasting to me and many others? Above all else, what I love most about science fiction is its ability to balance the strictly real with the strictly unreal to, when done properly, get the best of both worlds . In fantasy films and other such stories, creators can make up almost any rules and lore that they want, not needing to worry about whether or not it adheres to what someone else says is fact. While this allows imaginations to run wild as audiences are transported to entirely new worlds, it also creates a potentially higher barrier in getting people invested in those worlds. In the science fiction genre, the “real world” needs to be recognizable to at least some degree. As a result, it’s often a lot easier to connect to the settings and environments on a much more relatable level . There’s not nearly as much ground work that needs to be laid out that could potentially alienate us, and there aren’t nearly as many hurdles to jump through in selling us on the world being portrayed, because … well, it’s our own world, or at least a variation of it.

Plenty of straightforward dramas, action movies, and other kinds of films centered in reality have this same advantage, but what elevates science fiction as the best genre in that regard is that, at the same time, you also get the fun of messing around with that reality . Science fiction has the privilege of being able to twist, distort, or even outright change the pre-established real world to dazzle, frighten, or mystify the viewer with something they’ve never seen before. It can be as small as Ex Machina , where an artificially intelligent creation the likes of which we’ve yet to achieve can be brought to life for us to observe, think about, and even connect with on an emotional level because of how startlingly realistic it feels. Or it can be as grand as Inception , where the protagonists literally enter people’s dreams, resulting in exhilarating action sequences that couldn’t have worked had the film not played with reality in any way … while still having a starting point in reality that everyone is familiar with to make it feel more believable.

Science fiction at its best allows for the identifiable connection of something more grounded, and the wonder and memorability of something more heightened, all at once. It can definitely be a difficult tightrope walk , as you run the risk of the made-up or exaggerated parts of the story clashing with what’s supposedly more realistic. I think this is a big part of why some people say they don’t watch science fiction. They’ve likely been exposed to too many instances where these two sides clash and found them too off-putting. But that only makes it more impressive when the balancing act is pulled off. How does someone take the ordinary and believably twist it into something extraordinary? What doors are suddenly opened by mixing the real with the unreal? How does that change the motivations of the characters in the story…, and, by extension, what does that say about how we would behave if we experienced these changes in our actual lives? In the right hands, the potential for greatness in the genre is far higher than some may initially think.

SCIENCE FICTION SPANS MULTIPLE GENRES

Another one of my favorite aspects of science fiction is its versatility across multiple different genres . Think about some of the best, most iconic science fiction films ever made. The Thing, Back to the Future, 2001: A Space Odyssey, Inception , 12 Monkeys, Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind … these films are all so distinct from one another, ranging from pure horror to pure comedy to dark satire to fun action. Yet all of them are classified as at least partially science fiction, if not entirely. They all retain the essentials of what makes science fiction what it is, but they use those essentials to create very different experiences. Some of them are meant to be taken stone-cold seriously, some are happy-to-lucky crowd pleasers, and some fall in between, that last case requiring a balance of fun and serious within the balance of science and fiction. Regardless, these and other diverse entries in the genre all aim to do the same thing: bring something abnormal into normalcy and see how the world and characters deal with it.

I would even classify some comic book films as science fiction. Maybe not the purely grounded ones like The Dark Knight or those that heavily involve the supernatural like Doctor Strange , but the X-Men film series absolutely counts, since it establishes the existence of mutant human beings while otherwise keeping our own world and history intact. The same thing applies to a lot of monster movies , like Godzilla , whose titular creature is unleashed through scientific means and combated through science as well. Both of these films use their sci-fi conventions as means to portray and comment on real and important subjects – prejudice and identity in X-Men ’s case, and nuclear warfare and natural destruction in Godzilla ’s – giving them the social relevance that most of the best science fiction is known for.

Because of how universally applicable science fiction is to a wide range of genres, I question those who say they’re not really into it. Granted, I think that when a lot of people in the general public hear the term “science fiction” or “sci-fi”, it’s natural for their thoughts to immediately turn to some of the sillier, campier popcorn films of the genre. Big crowd-pleasing blockbusters like Independence Day , Back to the Future , or The Fifth Element are usually the most widely-recognized science fiction films to the population at large, and as a result, I think many people have a limited perspective of what science fiction can really be. I’m not at all saying that these are lesser films, just that they don’t represent the wide spectrum of what the genre is capable of. If anyone is looking for something more serious and intellectual, for instance, they may not think to turn to science fiction because of these kinds of preconceptions .

But no matter what your tastes are, I guarantee that there’s something in the sci-fi genre that’s right up your alley, which is something I can’t say for many other genres. Even horror, which is also very versatile in what can be done with it, has its limits on who will enjoy it, as not everyone is going to like being scared, disturbed, or shocked in any capacity. The action genre similarly won’t appeal to those who see no appeal in violence or destruction as entertainment, so even the best films of that genre have a limited reach. Science fiction doesn’t have a ceiling like that. It has something for everyone and can fit into whatever someone’s tastes may be , maybe even expanding their tastes by serving as a gateway to more surreal ideas outside of their comfort zone. I think that anyone who says they don’t care much for sci-fi simply hasn’t found the stories that are right for them yet.

THE DIFFERENT LEVELS OF SCIENCE AND FICTION

Such broad appeal raises questions regarding the merits that come from how much you focus on the science and how much you focus on the fiction of any given sci-fi film or story. Sometimes the more “realistic” an exploration of certain concepts is, the more startling it is to see it taken to unproven extremes. Interstellar , my favorite film of all time, makes amazing narrative use of gravitational time dilation. In the film, astronauts travel across galaxies and are exposed to the gravitational effects of a black hole that cause them to age decades more slowly than their loved ones on Earth. Though Interstellar absolutely takes liberties with a few of its scientific concepts, this is a phenomenon that actually happens, and the film heavily leans into the details of how it works. And because it’s portrayed as closely to proven fact as possible , the emotional impact and frightening nature of the situation are so much more palpable, audiences perhaps learn about something they’d never have thought was possible, and the film’s few forays into unprovable fiction have a lot more weight to them.

But it’s one thing to have only a few aspects of science be exaggerated. What about when an entire world is drenched in that exaggeration? The Blade Runner films technically take place in versions of our own world, but there are so many visual differences and advanced technological feats that they sometimes don’t even resemble our world. But they’re meant to portray the futures of the times they came out, and the future is open to a lot of different interpretations because we obviously don’t know what it entails. Seeing someone’s imagination of what present-day problems could possibly amount to in the future is often the best source of commentary for “cyberpunk” films like these, with Blade Runner and Blade Runner 2049 showing us environmental devastation , the line between life and machinery, and the god complexes of those in power, all of which were valid concerns then and are even more relevant now.

Some science fiction films start out fully centered in reality before dipping themselves into the complete unknown. Arguably the most prolific film in the genre to do this is 2001: A Space Odyssey. This classic starts out looking like a pretty believable take on human life in space, but it then introduces HAL 9000 as an artificial intelligence who runs amok trying to keep order and maintain the illusion of his perfection. The film then ends with one of the most trippy, bizarre sequences ever that comes solely from the minds of the filmmakers. These three segments vary wildly in how far-fetched they are, covering so much of science fiction’s range within a single film to explore how humanity’s search to advance themselves may end with those advancements overpowering them. The ending has no clear meaning, but I see it as the ultimate culmination of someone learning all that they can and realizing how small they are as a result. An infant in the grand scheme of things, if you will.

THE IMPORTANCE OF SCIENCE FICTION IN FILM AND BEYOND

As the popular saying goes, truth is often stranger than fiction . The universe is a challenging, complicated, and ambiguous place, whether it comes to our own human nature, events and shifts in landscapes and societies, or what lies beyond our understanding and awareness. Obviously, film and other artistic mediums are at their most powerful when they dig deep into these concerns and help us either make sense of them or, at the very least, think more deeply about them. Science fiction has proven to be no exception to this throughout history, and I consider it to be the best, mosteffective form through which to tell such stories. It gets people’s attention with creativity and spectacle, and it uses that as a gateway to explore a huge variety of profound questions and subjects viewers may have never considered before.

Don’t get me wrong, pretty much every genre has accomplished this in some way. But because of the blend of fact and fiction that science fiction not only heavily hinges on but often puts so much emphasis on, and because any and every point in time has a treasure trove of potential for the commentary science fiction provides, I believe science fiction is the genre in which those accomplishments come the most naturally. It’s also arguably one of the first “genres” to make it big with societies at large . As early as the original Frankenstein novel or as recently as Everything Everywhere All At Once , science fiction has always had something new and jaw-dropping to entrance audiences and make them think more deeply about the nature of their own lives and surroundings. And as long as there are storytellers who continue to tap into that, science fiction will remain the genre I consider the best and hold in the highest regard and importance.

Read our article on why science fiction needs to lighten up !

- TAGS: genre: sci-fi , Opinion

- Cannes Film Festival , Film Festivals , Films , Must Watch

Furiosa: A Mad Max Saga Review – Visceral Storytelling

- Serena Seghedoni

- May 19, 2024

Kinds of Kindness review: Lanthimos returns to his roots

- May 18, 2024

Oh, Canada Review: Schrader’s Cannes confession

- Philip Bagnall

The Strangers Chapter 1 Review: New cast, recycled ideas

- Films , Must Watch

The Blue Angels Film Review: Flying High

Everything we know about heartstopper season 3.

- Catherine Searcey

LATEST POSTS

Screen Rant

How sci-fi movies have changed in each decade (& why).

Your changes have been saved

Email Is sent

Please verify your email address.

You’ve reached your account maximum for followed topics.

Star Wars Reveals the Sith Luke Skywalker Would Have Become If He'd Joined Palpatine

George lucas' star wars plans debunk a huge sequel trilogy criticism (& reveal the real problem), "it feels like we should": daisy ridley hopes for co-star john boyega's return in her next star wars movie.

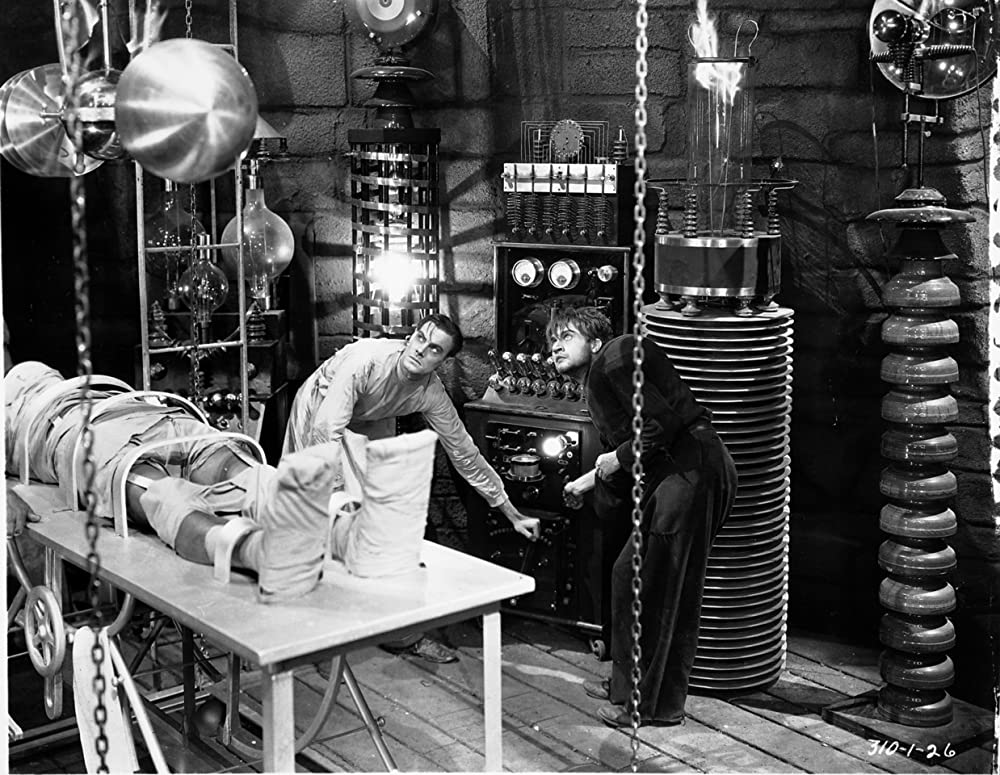

Science fiction was one of the first genres to emerge in film history, and it has changed dramatically in the 100+ years that it's been around. Sci-fi existed long before the invention of cinema, and originating in novels as far back as the early 1800s. Many historians of literature believe that Mary Shelley's Frankenstein is the first true work of science fiction in literary canon, helping to establish certain identifiable trends in the genre - such as the arrogant genius, and the potential dangers of scientific ambition.

After making the jump from literature to film in the early 1900s, science fiction was able to plumb new depths. What began as written imagination flourished on camera, and the genre began to explore new and exciting subgenres on-screen. Dozens of popular science-fiction novels were adapted into films that rendered the intangible into the visual. And outside of just adaptations, genre filmmakers were pushing the envelope with stories that reflected the realities of life in fantastical and futuristic ways. Movies like Planet of the Apes , Blade Runner , and The Terminator were all incredibly instrumental in establishing science-fiction as an ever-growing canon with its own set of tropes, characteristics, and cinematic language.

Related: Tron: Why The '80s Sci-Fi Movie Was So Expensive

As popular as sci-fi films are now, this wasn't necessarily always the case. With modern genre films experiencing heightened levels of popularity, it's important to note that this renaissance is the result of years of cinematic transformation, and dozens of science-fiction movies that pushed the envelope and broke new ground. Each decade brought new films, new trends, new tropes, and new ways to imagine the future of the human experience.

In the early 1900's, film had yet to become the dominating entertainment medium that it is recognized as today. In fact, the earliest recognized film recording, the Roundhay Garden Scene, had only been filmed 12 years before the turn of the century. The dawn of the 1900s popularized film being used as a source of entertainment, as before then the pioneers of the technology considered it a technology to be used in a solely scientific capacity. The Lumière Brothers (who were the first to showcase a moving picture to a gathered audience, essentially birthing cinema) believed that film was reserved for filming "actualities," the predecessor of the documentary. Unlike the documentary, actualities were unedited: raw recordings intended to depict life in as unaltered a manner as possible.

While the actuality was wildly popular at the end of the 1800s, film inevitably began to be used as a source of entertainment. Early filmmakers such as George Méliès began to push the boundaries of what film could be, with his short films A Trip to the Moon and The Impossible Voyage, released in 1902 and 1904 respectively. Both films represent the general atmosphere surrounding science fiction films at the time, even though in retrospect they'd lie more in the realm of science fantasy. Méliès films generally followed groups of intellectuals and theorists who decide to make a voyage to a fantastical realm or achieve some nigh-impossible goal, through the usage of absurd yet vaguely scientific equipment. Wildly popular across the globe, these movies inspired a wealth of imitators such as 1910's An Interplanetary Marriage, and established science fiction as a major force of imagination even in the early days of film.

Over 20 years after the creation of the first cinema camera, film was becoming more and more of an accessible artform. While not nearly as commonplace as our modern day excursions to the movie theater, all across the world artists from other mediums were beginning to view film as a revolutionary craft, leading to more and more features and short films being created. With George Méliès' last film, The Conquest of the Pole, being released in 1912, science fiction films were generally beginning to move away from his highly fantastical approach and settling into a more grounded atmosphere.

Related: How Inception Revolutionized Sci-Fi Movies For The 2010s

Movies such as 1916's 20,000 Leagues Under The Sea, the first movie ever filmed partially underwater, and The Master Mystery, an American film serial from 1918 starring Harry Houdini, showcased cinema's transition towards harder, more tangible scientific fiction. Subject matter included scientific expeditions and robotic automatons, representing the world's budding curiosity regarding the technological advancements of the day. Because of the rapid advancements in cinematic techniques, audiences also began to become more accustomed to the feature length film, a transition that would continue to the point where short films are much more niche today than they were 60 years ago.

During the early days of film, specifically the 1910s, a lot of the short films being made were escapist fantasies; experimental stories made by book authors and magicians. However, the 1920s marked a distinct shift in the structure of a lot of genre film, specifically science fiction. As filmmaking became a more sophisticated form, screenwriters and directors were beginning to infuse social commentary into the movies they were making. Science-fiction literature set the precedent, but the 1920s seriously established the capacity for movies to be a social allegory.

The greatest example of this to come out of the decade is Fritz Lang's 1927 masterpiece Metropolis , a shining example of the German expressionist movement. Heavily inspired by German industrialism as well as the widening gap between the rich elites and the poor working class, Metropolis depicts a future in which the lower class workers are forced to toil away underground while the 1% lives in towering skyscrapers. The atrocious disparity of living between the two classes was a direct parallel to the economic turmoil experienced by Germany in the aftermath of World War 1. To this day, Metropolis is a gold-standard for not only the dystopian future, but sci-fi entertainment in general.

While the genre flourished in the decades prior to the 1930s, the early 1930s saw the world climbing out of the economic horrors that marked the Great Depression. As a result of this, the science fiction genre was less idealistic than it had been in years prior. Both literature and film experienced a considerably darker shift in the genre, reflected in the growing prominence of science fiction being fused with other genres.

Related: Why Sci-Fi Movies Starring AI Actors Is Actually A Good Idea

The most iconic movies to come out of the decade were the Universal and Paramount sci-fi horror movies , most notably Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde and The Invisible Man. These films lie in a middle ground between the escapist fantasy of earlier pioneers as well as the harder sci-fi of the 20s and 30s, and the end result are movies that use science and technology to reflect the growing apprehension and dread felt by international audiences slowly moving out of the Great Depression. Unfortunately, things across the world got worse before they got better, as the aftermath of the Great Depression inevitably led to other, greater global horrors.

The 1940s bore witness to the largest scale global conflict of all-time: the meat-grinder known as World War 2. Countless lives were lost, and the effects were felt in culture and art across the world. While the most popular movies being produced at the time were war films , particularly outright propaganda drumming up support for either cause, sci-fi films also experienced the effects of the war effort. With Universal and Paramount continuing to pump out their iconic monster films, many American studios used science fiction tropes in pulp fiction like Flash Gordon to show the horrors of fascism and authoritarianism.

One film from this era, 1945's Strange Holiday, is very on-the-nose about its anti-authoritarian message. John Stevenson, the main character, comes back from a vacation and is shocked to discover that fascists have taken over the United States of America. Like lots of innocuous films at the time, the movie was actually secretly written by the General Motors corporation, a common practice at the time. Lots of industrial companies were repurposed to aid in the war effort, and one of the ways that they did this was using their funds to promote movies that justified the United States' actions in the war.

Science fiction in the 1950s went through one of the biggest cultural shifts to ever take place in the genre, a transformation which was directly tied to one of the most horrifying scientific breakthroughs ever. The first and only recorded usage of nuclear weapons was perpetrated against Japan at the tail end of World War 2. Little Boy and Fat Man were detonated over the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, three days apart, in August of 1945, and the combined death toll of both bombings lies somewhere around 200,000. Since then, for better or worse, the shadow of nuclear annihilation has loomed large over international affairs and modern society.

Related: Why Sci-Fi Movies Are So Divisive At The Box Office

Science fiction films were some of the first sources of entertainment to tackle this massive event. Using pulpy, garish filmmaking techniques, movies such as Them! and It Came From Beneath The Sea terrorized audiences with freakishly large animals either warped or unearthed by nuclear testing. The granddaddy of the kaiju film, Gojira , came out in 1954, directly inspired by the atomic fears borne out of the nuclear bombings.

However, the atomic age wasn't the only social issue being addressed in science fiction films. With the Soviet Union growing in power and influence, a major theme tackled in science-fiction films was the fear of invasion, a thinly-veiled allegory for the American fear of communism. The original Invasion of the Body Snatchers came out during this time, and with its emotionless alien imitators, the movie paradoxically became a double-edged allegory for both the Red Scare as well as the McCarthyist witch hunts that seized the nation.

The popularity of the films made during the "Golden Age" of science fiction persisted through the 1960s, leaving audiences with a deluge of atomic-inspired sci-fi horror as well as the total domination of the Shōwa-era Godzilla films. For most of the '60s it seemed as if aliens and radioactive creatures were everywhere, mostly because those types of films could be produced with relatively small budgets and were guaranteed money-makers for the studio. However, the tail end of the 1960s rejuvenated the sci-fi genre with two particular films that abandoned the hokey tone of their predecessors, and carried strands of Metropolis' socially-charged DNA.

1968 introduced moviegoers to Franklin J. Schaffner's Planet of the Apes, a scathing critique of the nuclear obsession that also happened to revolutionize special effects. Later that same year, Stanley Kubrick's widely-beloved masterwork 2001: A Space Odyssey was released, exploring a wealth of different themes ranging from humanity's search for meaning to the sentience of artificial intelligence. Both movies re-ignited the spark for intellectual science fiction on-screen and paved the way for many of the movies we have now.

Related: 1970s vs 1980s Sci-Fi Movies: Which Decade Was Better

While the cheap sci-fi horror film never fully went away, 2001 directly led to a surge in smart sci-fi thrillers being released internationally. Movies like The Andromeda Strain, Soylent Green, and Solaris were all slow, methodical science-fiction films that leaned heavily into the philosophical implications of the stories they were telling. At the same time however, the movie circuit was just beginning to understand the power of the blockbuster and what it could do when coupled with other types of movies.

The one-two punch of Star Wars in 1977 and Superman: The Movie in 1978 forever changed the landscape of filmmaking. One an original property, the other a comic book adaptation, both were insanely successful and led to the creation of massive game-changing franchises. Superman was almost twenty years ahead of the superhero movie curve and pioneered special effects work, while Star Wars... well, everyone knows what Star Wars did.

As popular movies generally do in Hollywood, the impact of Star Wars led to a wealth of imitators, most of which fell on the scale of cheap to decent. Battle Beyond the Stars is arguably the most famous of these imitations, mostly due to the fact that the advanced special effects were done by James Cameron himself. Cameron would go on to define the science-fiction genre in the 80s with his own film, The Terminator. One of a few truly original time-travel films, not only did The Terminator essentially write the book on time-travel paradoxes , but it also fit into a budding trend for sci-fi in the 80s, which was the futuristic apocalypse setting. Many different films used this in different ways, including Blade Runner and the animated Akira , but the collective panic surrounding a bleak technological future was undoubtedly inspired by the uncertainty revolving the ongoing Cold War.

If the '50s reflected the paranoia and fear regarding the world's entry into the nuclear age, then the '90s were all about the collective apprehension surrounding the dawn of the Internet Age. Countless films of this time period regarded technology with a sort of curious terror, such as Hardware, which follows a murderous robot enacting a rampage across a post-apocalyptic wasteland. Terminator 2 also reflected this kind of cybernetic paranoia, with the reveal that the Skynet system emerged from the creation of a complex super-processor.

Related: Is Sci-Fi's Origin Anti-Science?

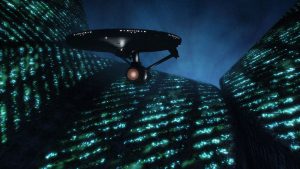

Of course, no movie from the 90s more accurately reflected the post-modernist attitude towards developing technology and the atmosphere surrounding the budding internet culture than The Matrix . Pulling from a wealth of different inspirations (including Buddhism, Superman, and Ghost in the Shell ), the Wachowskis' vision of a dystopian future in which humanity has been enslaved by robots perfectly captured the cultural zeitgeist, and inspired a wave of films that picked at those same themes.

The advent of CGI heavily influenced many films during this time, especially science fiction films, and nowhere is that more evident than the Star Wars prequel trilogy. Despite their complex and intricate world-building, Lucas' over-reliance on visual effects and cheap humor undercut what could have been a stellar return to a galaxy far, far away. However, that didn't stop other filmmakers from taking Lucas' pioneering work with CGI and repurposing it on other projects. James Cameron's 2009 film Avatar is, to this day, one of the most groundbreaking movies ever made simply because of the strides made in the department of visual effects . Coupling CGI and 3D technology gave moviegoing audiences an audio-visual experience whose impact can never be understated.

Ever since the dawn of the blockbuster in the 1970s, they have become more and more popular in the studio system, and the 2010s is arguably when they hit critical mass. Huge blockbuster franchises flourished during this time period, such as the Transformers movies as well as most of the Marvel Cinematic Universe . While superhero films first and foremost, most of them have roots in pulp science-fiction concepts and wear those influences on their sleeves when dealing with artificial intelligence or extraterrestrial superheroes.

Towards the tail end of this period the arthouse science fiction film grew in popularity. In the same vein as movies like 2001, indie filmmakers were pumping out daring and original concepts such as Under the Skin and Ex Machina , and even studios were occasionally taking risks on larger intellectual sci-fi films like Nolan's Interstellar .

Related: How Dune Changed Sci-Fi Movies (& Denis Villenueve Can Do It Again)

2020s and Beyond

Even with the trends of decades past behind us, it's hard to identify exactly where sci-fi will go next. While audiences have their eyes on certain upcoming releases such as Tenet and Denis Villenueve's long-anticipated Dune adaptation, no one knows for certain what could come next for the genre. Ever since its early days in the pages of classic literature, science-fiction has reflected the discoveries and experiences of the society that informs it. As long as culture and technology continue to develop across the globe in new and exciting ways, so too will science fiction continue to shock and surprise audiences worldwide.

More: How Director Jack Arnold Defined American Sci-Fi Movies

- SR Originals

The Genre of Science Fiction in Movies Term Paper

Introduction, “the war of the worlds”, “star wars”, “the fifth element”.

Bibliography

In this paper we will analyse “The War of the Worlds” (1953), “Star Wars” (1977) and “The Fifth Element” (1997), as movies that reflect the genre of science fiction being transformed from something that used to help people expanding their minds and to provide them with the insight onto the future, into the mere tool of entertainment, which in its turn, reflects the fact that, during the course of second half of twentieth century, White people’s existential vitality have been steadily undermined by degenerative socio-political doctrines, associated with the rise of neo-Liberalism.

When we closely analyze the traditional subtleties of literary genre of science fiction, we will be able to define its two most important characteristics: 1) It is exclusively associated with Western (White) civilization; 2) Classical science fiction works utilize futuristic motifs as the tool of attracting wider audience. Therefore, we can say that, up until comparatively recent times, the genre of science fiction in literature and movies was simply reflecting White people’s ability to push forward scientific and cultural progress. It is not by pure coincidence that this genre was at the peak of its popularity in late 19 th and early 20 th century, when after being released out of Christian imprisonment, Western creative genius was producing groundbreaking scientific discoveries every 2-3 years. However, if we look at the pace of scientific progress in last fifty years, it will appear that, within this period of time, not a single scientific breakthrough of universal magnitude was being accomplished. It is only informational technologies, associated with the rise of Internet (70% of Internet traffic relates to promotion of pornography), that were able to advance rapidly. Americans stopped sending manned spacecrafts to the Moon, Russians allowed their space station “Mir” to crush into the Earth. The whole concept of space exploration is now associated with rich moneybags getting cheep thrills out of being launched into the space as “tourists”, rather then with evolutionary progress of a mankind, as it used to be the case in comparatively recent times. Therefore, it will only be logical, on our part, to expect modern science fiction movies to reflect the reality of humanity’s civilizational progress being reversed backwards, as a result of more and more people in Western countries being preoccupied with “celebration of diversity”, as the only thing they are capable of doing. In the following parts of this paper, we will substantiate the conceptual validity of this statement, by embarking on closer analysis of movies mentioned in the initial thesis statement.

The movie “The War of the Worlds” was produced in 1953, when America’s national integrity was at its strongest and when Americans thought that such integrity could only be threatened from outside. It is now being often suggested that this movie had sublimated Americans’ subconscious fears of Commies. We can agree with such point of view to a certain extent, however, it is wrong to refer to “The War of the Worlds” as such that has apocalyptic motifs incorporated in its very core. Despite the fact that even U.S. military appears to be utterly helpless, while trying to deal with hostile Martians, the majority of movie’s characters do not yield to panic. They understand perfectly well that it is only the knowledge of Martians’ physical constitution that might provide them with a clue as to how fight them in most effective manner. This is why, throughout the movie, its main characters continue to discuss Martians’ appearance as such that relates to the physical conditions of their native planet: “Supposedly they are Martians Professor, what would they look like? Bigger then us, smaller? – Our gravitational force would weight them down; our heavier air would’ve pressed them. – You think they’d be breathing creatures like us? What about blood, hearts, and all that? – If they do have hearts, they’d be certainly beating at slower rate, but their sense might be quite different from ours…” (IMDB, 2000).

In other words, movie popularizes scientific notions among viewers, which actually corresponds to the original essence of science fiction as genre. This is because, people who are not being affected by racial mixing and by degenerative socio-political doctrines, derive aesthetic pleasure out of absorbing scientific knowledge, rather then out of watching people being blown to pieces. It is not by simple accident that the genre of science fiction has been traditionally liked by young people more then by representatives of older generations – in fifties, the sci-fi movies were actually helping teenagers to gain a better understanding of surrounding reality. Back then, in order to be considered as “cool”, a young man needed to know how to built model rockets and to be capable of swimming for 2 miles, for example, as opposed to today’s concept of “coolness” that closely relates to “gangsta” lifestyle. This is the reason why “The War of the Worlds” was able to gross US$ 2,000,000 (a huge amount of money in fifties) by satisfying people’s scientific curiosity as to the possible consequences of alien life forms being brought to the Earth. We can say that, unlike in many modern sci-fi movies, the essence of this particular genre in “The War of the Worlds” did not contradict the actual science. In fifties, Americans did not have doubts as to the value of their empirical sense of rationale, which is why “The War of the Worlds” does not feature any mystical motifs – the arrival of hostile aliens to Earth and their eventual demise correspond to biological laws of nature, as we know them. Therefore, we can refer to this particular movie as sci-fi classic, because in “The War of the Worlds”, the events revolve around scientific notions and not the other way around, as it became a customary practice in today’s science fiction movies.

George Lucas’ cinematographic masterpiece “Star Wars” was being subjected to extensive cultorogical studies ever since the time of its release in 1977, with majority of critics agreeing on movie’s high aesthetic value. However, even though that it formally relates to the genre of science fiction, we can barely discuss it as sci-fi movie, because “Star Wars” is nothing but an extrapolation of modern White people’s existential inadequateness, in form of futuristic “fairy tale”. In his article “Back to the Future”, where he talks about movies “Harry Potter”, “Lord of the Rings” and “Star Wars”, Michael Moses makes a very good point when he suggests that in seventies, the genre of sci-fi had ceased to relate to empirical science and was being transformed into the instrument for citizens to conduit their subconscious anxieties: “They (movies) nonetheless respond to a specifically modern set of social anxieties. Indeed, each expresses a deep discomfort with modernity itself. If the fundamental narrative structure of the films borrows heavily from tradition, the specific forms that both good and evil assume within them are those of the modern world… One of the contemporary discontents to which all three series respond is a general boredom with modern bourgeois existence. The escapism of these stories is an antidote to the routine that is the special curse of safe, static middle-class life” (Moses, p. 49). We can only agree with the author – “Star Wars” is a cinematographic quintessence of White people’s existential idealism, as it links metaphysical evil with corruption and implies that only young people, untainted by mental and physical inadequacy, are capable of “restoring justice in the Galaxy”.

One of movie’s most memorable scenes is when Luke Skywalker sits in the bar with Obi One Kenobi, while being surrounded by ugly creatures from outer space, who “celebrate diversity” by drinking, gambling and shooting each other. Kenobi talks about “civilized times”, which he clearly associates with the existence of law and order and which he considers as being inconsistent with “galactic multiculturalism”, seen on Tatooine. This scene provides us with the insight on “Star Wars” immense popularity. Apparently, movie promotes the idea that “fish begins to rot from the head”. In seventies, many White Americans were beginning to suspect that there was something seriously wrong with this nation – they were still remaining masters in their own country, but they sensed that such situation will not last for long. While being unable to rationalise their subconscious fears, Whites were increasingly tending to sublimate these fears into “cinematographic escapism”. “Star Wars” appears to be utterly unscientific, within a context of its portrayal of space travel, for example – yet, it is absolutely scientific in how it presents the very essence of the concept of scientific progress, as closely related to the notion of justice and to people’s inborn sense of idealism. It is not simply a coincidence that Luke Skywalker, while being shown as classic idealist, also embodies the ideal of Aryan physical perfection. It is White people’s existential idealism, which allowed them to operate with highly abstract categories (IQ rate), which in its turn, set preconditions for the emergence of culture and science. It is their genetic idealism that made it possible for the Whites to come winners out of seemingly impossible circumstances, throughout the history, and to become undisputed masters of the world by the end of 19 th century, while remaining at the spearhead of the process of biological evolution. This notion is not being taught to Whites in schools, however, it is being perceived by them on subconscious level, which is why the idea of idealistic young White man being able to effectively resist the forces of darkness, contained in “Star Wars”, continues to appeal to many Americans even today. Thus, we can conclude that “Star Wars” corresponds to the middle stage of the process of sci-fi genre being deprived of its scientific spirit; as such, that reflected the essence of world’s socio-political dynamics in seventies and eighties.

In last century, before the collapse of Roman Empire, the overwhelming majority of mongrelized Roman citizens were preoccupied with seeking entertainment, as the solemn purpose of their existence. As a result, in the eyes of corrupted Romans, the value of their science, philosophy and literature, was being increasingly perceived through the lenses of entertainment. We all know how Romans ended up. But apparently, not many people are capable of learning from the lessons of history, which is why America is now closely following the footsteps of ancient Rome, with hordes of barbarians from Third World eagerly waiting for Americans to fully succumb to existential decadence. It appears that they will not have to wait for much longer, as hook-nosed Hollywood producers had succeeded in “redesigning” the genre of science fiction to serve purely entertaining purposes. Nothing substantiates the validity of this statement better then Luc Besson’s movie “The Fifth Element”, which is nothing but masterfully designed set of special effects, with movie’s actual plot existing only in the minds of viewers. We can say that “The Fifth Element” actually portrays the beauty of living in “multicultural” society (primitive Arab tunes serving as musical accompaniment, neon advertisements in Chinese, Mangalores – whose level of intelligence and physical appearance remind us the residents of the “hood”). Still, it is quite unexplainable why “The Fifth Element” is being referred to as science fiction movie, as the only truly futuristic element in the movie are yellow cabs, sustained in the air by some mysterious force, subtleties of which Luc Besson does not bother to reveal to viewers. During the course of movie’s production, Besson’s main task was to instil his “masterpiece” with enough explosions and violence, in order to attract marginalized audience, rather then to provide people with the insight on things to come. Nevertheless, we cannot discuss “The Fifth Element” as such that does not deserve our attention, because just as “Star Wars”, it contains an idea of racial purity as directly corresponding to the essence of cultural and scientific progress, even though that instilling movie with such idea was the last thing on Besson’s mind.

In “The Fifth Element”, the humanity is portrayed as being corrupted beyond the point of recovery, which is why it fully deserves to be destroyed by Evil from outer space. Nevertheless, mankind does have a chance – Leeloo (perfect Aryan specimen) is capable of stopping the Evil from descending upon the Earth, by the fact of its mere existence. Korben Dallas (another perfect Aryan specimen), as person who likes to continuously show homosexual Ruby Rhod where he belongs, is being chosen to assist Leeloo in saving the humanity. After having succeeded in fighting off the Evil, both characters move to the next stage of process of saving humanity – making Aryan babies. Despite being presented in rather humorous manner, this idea possesses scientific properties, as we have illustrated earlier. This is why “The Fifth Element” is now being criticized for its apparent lack of “tolerance” by self-appointed “experts on racial relations”, such as Brian Ott, who in his article “Counter-Imagination as Interpretive Practice: Futuristic Fantasy and The Fifth Element” suggested that Besson’s flick should be outlawed: “The Fifth Element constructs sexual and racial difference in a manner that privileges and naturalizes White heterosexual masculinity. It destabilizes the categories of sexual and racial difference as they are negotiated within appeals to popular imagination” (Ott, p. 149). Therefore, we can say that, despite its essence as an entertainment flick, “The Fifth Element” does posses a scientific value, simply because it infuriates the hawks of political correctness, who strive to slow down and to eventually reverse the course of scientific progress as such that contradicts their dogma of “racial equality”.

In order for us to summarize this paper, we need to state the following: the genre of science fiction in movies has been traditionally linked with people’s ability to push forward scientific progress, which in its turn corresponds to their racial affiliation. The reason why early sci-fi movies can be described as rather “technocratic” then “entertaining”, is because at the time of their creation, Western societies were racially homogeneous, which caused viewers to associate “sci-fi pleasure” with gaining a scientific information. The practice of racial mixing undermines people’s ability to operate with abstract categories and makes it harder for them to keep their animalistic urges under control. Given the fact that “celebration of diversity” has been going on in America for more then 30 years, it comes as no surprise that more and more Americans tend to succumb to their primeval instincts, while being incapable to indulge in intellectual activities whatsoever. The evolution of sci-fi genre simply reflects this process – this genre has effectively ceased being associated with science and now only serves the purpose of providing marginalized population with cheep thrills. Thus, we can conclude that if current demographical trends continue to gain a momentum (in 2030, Whites will amount to only 2% of Earth’s population), the genre of sci-fi in movies will cease to exist, simply as result of people starting to regress backwards, in evolutionary sense of this word, while being increasingly incapable of understanding of what the concept of science stands for, in the first place.

Appleyard, B. “Why Don’t we Love Science Fiction?”. 2007. Times Online. 2008. Web.

Arango, T. “ At Sci Fi Channel, the Universe Is Expanding and the Future Is Now ”. 2008. The New York Times. Web.

Edelman, S. “Erasing the Smell of Sci-Fi”. 2006. Sci Fi Weekly. Web.

Polselli, A. “The Fall of the Sci-Fi Genre in Film”. 2007. Web.

Moses, M. (2003) “Back to the Future”. Reason, v. 35, no. 3, p. 48-57.

The War of the Worlds (1953). 2000. The Internet Movie Database. 2008. Web.

Ott, B. (2004). “Counter-Imagination as Interpretive Practice: Futuristic Fantasy and the Fifth Element”. Women’s Studies in Communication, v. 27, no. 2, p. 149-76.

McLean, G. “ The New Sci-Fi ”. 2007. Guardian News and Media. 2008. Web.

Morris, T. “The SciFi Superiority Complex: Elitism in SF/F/H”. 2004. Strange Horizons. 2006. Web.

Masterson, L. “Science Fiction Sub-Genres”. 2005. Sci-Fi Factor. 2008. Web.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2021, September 26). The Genre of Science Fiction in Movies. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-genre-of-science-fiction-in-movies/

"The Genre of Science Fiction in Movies." IvyPanda , 26 Sept. 2021, ivypanda.com/essays/the-genre-of-science-fiction-in-movies/.

IvyPanda . (2021) 'The Genre of Science Fiction in Movies'. 26 September.

IvyPanda . 2021. "The Genre of Science Fiction in Movies." September 26, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-genre-of-science-fiction-in-movies/.

1. IvyPanda . "The Genre of Science Fiction in Movies." September 26, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-genre-of-science-fiction-in-movies/.

IvyPanda . "The Genre of Science Fiction in Movies." September 26, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-genre-of-science-fiction-in-movies/.

- Social Democracy as the Ultimate Form of Government: "War of the Worlds" by H. Wells

- Advertisements of Chanel No. 5

- "The War of the Worlds" a Novel by Herbert Wells

- David Fincher's "Fight Club":Themes and Perception

- The Influence of Movie Genre on Audience

- The Movie ‘Sicko’ by Michael Moore

- Global Warming: "An Inconvenient Truth" by D. Guggenheim

- Friday Night Lights: Book vs. Movie

Science Essay

Essay About Science Fiction

Science Fiction Essay: Examples & Easy Steps Guide

People also read

Learn How to Write an A+ Science Essay

150+ Engaging Science Essay Topics To Hook Your Readers

Read 8 Impressive Science Essay Examples And Get Inspired

Essay About Science and Technology| Tips & Examples

Essay About Science in Everyday Life - Samples & Writing Tips

Check Out 5 Impressive Essay About Science Fair Examples

Whether you are a science or literature student, you have one task in common:

Writing an essay about science fiction!

Writing essays can be hard, but writing about science fiction can be even harder. How do you write an essay about something so diverse and deep? And where do you even start?

In this guide, we will discuss what science fiction is and how to write an essay about it. You will also get possible topics and example essays to help get your creative juices flowing.

So read on for all the information you need to ace that science fiction essay.

- 1. What Is Science Fiction?

- 2. What Is a Science Fiction Essay?

- 3. Science Fiction Essay Examples

- 4. How to Write an Essay About Science Fiction?

- 5. Science Fiction Essay Topics

- 6. Science Fiction Essay Questions

- 7. Science Fiction Essay Tips

What Is Science Fiction?

Science fiction is a genre of literature that often explores the potential consequences of scientific, social, and technological innovations. These might affect individuals, societies, or even the entire human race in the story.

The central conflict in many science fiction stories takes place within the individual human mind, addressing questions about the nature of reality itself.

It often follows themes of exploration, speculation, and adventure. Science fiction is popular in novels, films, television, and other media.

At its core, science fiction uses scientific concepts to explore the human condition or to create alternate realities. It often asks questions about the nature of reality, morality, and ethics in light of scientific advancements.

Now that we understand what science fiction is let's see some best essays on science fiction!

What Is a Science Fiction Essay?

Science fiction essays are written in response to a specific prompt, often focusing on a particular theme or idea.

They can be either creative pieces of writing or analytical works that examine the genre and its various elements.

It is different from a science essay , which discusses scientific topics in detail.

Science fiction essay aims to explore the implications of science fiction themes for our understanding of science and reality.

For science students, writing about science fiction can be useful to enhance their scientific curiosity and creativity.

Literature students get to write these essays a lot. So it is useful for them to be aware of some major scientific concepts and discoveries.

Here’s a video about what is science fiction:

Tough Essay Due? Hire Tough Writers!

Science Fiction Essay Examples

It can be helpful to look at examples when you're learning how to write an essay.

Here are some sample science fiction essay PDF examples:

Essay on Science Fiction Literature Example

Example Essay About Science Fiction

Short Essay About Science Fiction - Example Essay

Science Fiction Short Story Example

How to Start a Science Fiction Essay

Le Guin Science Fiction Essay

Pessimism In Science Fiction

Science Fiction and Fantasy

The Peculiarities Of Science Fiction Films

Essay on Science Fiction Movies

Looking for range of science essays? Here is a blog with some flawless science essay examples .

How to Write an Essay About Science Fiction?

Writing an essay on science fiction can be fun and exciting. It gives you the opportunity to explore new ideas and worlds.

Here are a few key steps you should follow for science fiction essay writing.

Know What Kind of Essay To Write

Science fiction essays can be descriptive, analytical, or exploratory. Always check with your instructor what kind of essay they want you to write.

For instance, a descriptive science fiction essay topic may describe the story of your favorite sci-fi novel or tv series.

Similarly, an analytical essay might require you to analyze a concept (e.g., time travel) in the light of science fiction literature.

On the other hand, explanatory essays require you to go beyond the literature to explore its background, influence, cultural impact, etc.

So different types of essays require different types of topics and writing styles. So it is important to know the type and purpose of your science fiction essay.

Find an Interesting Topic

There is a lot of science fiction out there. Find a movie, novel, or science fiction concept you want to discuss.

Think about what themes, messages, and ideas you want to explore. Look for interesting topics that can help make your essay stand out.

You can find a good topic by brainstorming the concepts or ideas that you find interesting. For instance, do you like the idea of traveling to the past or visiting futuristic worlds?

You'll find some great science fiction topics about the ideas you like to explore.

Do Some Research

Read more about the topic or idea you have selected.

Read articles, reviews, research papers, and talk to people who know science fiction. Get a better understanding of the idea you want to explore before diving in.

When doing research, take notes and keep track of sources. This will come in handy when you start writing your essay.

Organize Your Essay Outline

Now that you have done your research and have a good understanding of the topic, it's time to create an outline.

An outline will help you organize your thoughts and make sure all parts of your essay fit together. Your outline should include a thesis statement , supporting evidence, and a conclusion.

Once the outline is complete, start writing your essay.

Start Writing Your First Draft

Start your first draft by writing the introduction. Include a hook , provide background information, and identify your thesis statement.

Here is an example of a hook for a science fiction essay:

Your introduction should be catchy and interesting. But it also needs to show what the essay is about clearly.

Afterward, write your body paragraphs. In these paragraphs, you should provide supporting evidence for your main thesis statement. This could include quotes from books, films, or other related sources. Make sure you also cite any sources you use to avoid plagiarism.

Finally, conclude your essay with a summary of your main points and any final thoughts. Your science fiction essay conclusion should tie everything together and leave the reader with something to think about.

Edit and Proofread

Once your first draft is complete, it's time to edit and proofread.

Edit for any grammar mistakes, typos, or errors in facts. Check for sentence structure and make sure all your points are supported with evidence.

After that, read through your essay to check for flow and clarity. Make sure the essay is easy to understand and flows well from one point to the next.

Finally, make sure that the science fiction essay format is followed. Your instructor will provide you with specific formatting instructions. These will include font style, page settings, and heading styles. So make sure to format your essay accordingly.

Once you're happy with your final draft, submit your essay with confidence. With these steps, you'll surely write a great essay on science fiction!

Read on to check out some interesting topics, essay examples, and tips!

Science Fiction Essay Topics

Finding a topic for your science fiction essay is a difficult part. You need to find something that is interesting as well as relatable.

That is why we have collected a list of good topics to help you brainstorm more ideas. You can create a topic similar to these or choose one from here.

Here are some possible essay topics about science fiction:

- The Evolution of Science Fiction

- The Impact of Science Fiction on Society

- The Relationship Between Science and Science Fiction

- Discuss the Different Subgenres of Science Fiction

- The Influence of Science Fiction on Pop Culture

- The Role of Women in Science Fiction

- Describe Your Favorite Sci-Fi Novel or Film

- The Relationship Between Science Fiction and Fantasy

- Discuss the Major Themes of Your Favorite Science Fiction Story

- Explore the themes of identity in sci-fi films

Need prompts for your next science essay? Check out our 150+ science essay topics blog!

Science Fiction Essay Questions

Explore thought-provoking themes with these science fiction essay questions. From futuristic technology to extraterrestrial encounters, these prompts will ignite your creativity and critical thinking skills.

- How does sci-fi depict AI's societal influence?

- What ethical issues arise in genetic engineering in sci-fi?

- How have alien civilizations evolved in the genre?

- What's the contemporary relevance of dystopian themes in sci-fi?

- How do time travel narratives handle causality?

- What role does climate change play in science fiction?

- Ethical considerations of human augmentation in sci-fi?

- How does gender feature in future societies in sci-fi?

- What social commentary is embedded in sci-fi narratives?

- Themes of space exploration in sci-fi?

Science Fiction Essay Tips

So you've been assigned a science fiction essay. Whether you're a fan of the genre or not, this essay can be daunting.

But don't fear!

Here are some helpful tips to get you started on writing a science fiction essay that will impress your teacher and guarantee you a top grade.

Choose a Topic That Interests You

When it comes to writing a science fiction essay, it’s important to choose a topic that interests you.

Not only will this make the writing process more enjoyable, but it will also ensure that your essay is more engaging for the reader.

If you’re not sure what topic to write about, try brainstorming a few science fiction essay ideas until you find one that feels right.

Make Sure Your Essay is Well-Organized

Another important tip for writing a science fiction essay is to make sure that your essay is well-organized.

This means having a clear introduction, body, and conclusion. It also means ensuring that each paragraph flows smoothly into the next.

If your essay is disorganized or difficult to follow, chances are the reader will lose interest quickly.

Use Strong Verbs

When writing any type of essay, it’s important to use strong verbs. However, this is especially true when writing a science fiction essay.

Using strong verbs will help add excitement and energy to your writing, making it more engaging for the reader. Some examples of strong verbs include “discover,” “create,” and “explore.”

Be Creative

One of the best things about writing a science fiction essay is that you have the opportunity to be creative. This means thinking outside the box and coming up with new and innovative ideas.

If you’re struggling to be creative, try brainstorming with someone else or looking at other essays for inspiration.

Use Quotes Appropriately

While quotes can be helpful in supporting your argument, it’s important not to rely on them too heavily in your essay.

If you find yourself using too many quotes, chances are you’re not doing enough of your own thinking and analysis.

Instead of relying on quotes, try to paraphrase or summarize the main points from other sources.

To conclude the blog,

Writing a science fiction essay doesn’t have to be overwhelming. With these steps, examples, and tips, you can be sure to write an essay that will impress your teacher and guarantee you a top grade.

Whether it’s an essay about science fiction movies or novels, you can ace it with these steps! Remember, the key is to be creative and organized in your writing!

Don't have time to write your essay?

Don't stress! Leave it to us! Our science essay writing service is here to help!

Contact the team of experts at our essay writing service . We can help you write a creative, well-organized, and engaging essay for the reader. We provide free revisions and other exclusive perks!

Moreover, our AI-based essay typer will provide sample essays for you completely free! Try it out today!

Have questions? Ask our 24/7 customer support!

Write Essay Within 60 Seconds!

Betty is a freelance writer and researcher. She has a Masters in literature and enjoys providing writing services to her clients. Betty is an avid reader and loves learning new things. She has provided writing services to clients from all academic levels and related academic fields.

Paper Due? Why Suffer? That’s our Job!

Keep reading

Why Science Fiction Is the Most Important Genre

Slide: 1 / of 1 . Caption: Jonathan Nicholson/NurPhoto/Getty Images

- Author: Geek's Guide to the Galaxy. Geek's Guide to the Galaxy Culture

- Date of Publication: 09.08.18. 09.08.18

- Time of Publication: 8:50 am. 8:50 am

Yuval Noah Harari, author of the best-selling books Sapiens and Homo Deus , is a big fan of science fiction, and includes an entire chapter about it in his new book 21 Lessons for the 21st Century .

“Today science fiction is the most important artistic genre,” Harari says in Episode 325 of the Geek’s Guide to the Galaxy podcast. “It shapes the understanding of the public on things like artificial intelligence and biotechnology, which are likely to change our lives and society more than anything else in the coming decades.”

Because science fiction plays such a key role in shaping public opinion, he would like to see more science fiction that grapples with realistic issues like AI creating a permanent ‘useless class’ of workers. “If you want to raise public awareness of such issues, a good science fiction movie could be worth not one, but a hundred articles in Science or Nature , or even a hundred articles in the New York Times ,” he says.

But he thinks that too much science fiction tends to focus on scenarios that are fanciful or outlandish.

“In most science fiction books and movies about artificial intelligence, the main plot revolves around the moment when the computer or the robot gains consciousness and starts having feelings,” he says. “And I think that this diverts the attention of the public from the really important and realistic problems, to things that are unlikely to happen anytime soon.”

AI and biotechnology may be two of the most critical issues facing humanity, but Harari notes that they’re barely a blip on the political radar. He believes that science fiction authors and filmmakers need to do everything they can to change that.

“Technology is certainly not destiny,” he says. “We can still take action and we can still regulate these technologies to prevent the worst-case scenarios, and to use these technologies mainly for good.”

Listen to the complete interview with Yuval Noah Harari in Episode 325 of Geek’s Guide to the Galaxy (above). And check out some highlights from the discussion below.

Yuval Noah Harari on automation:

“It’s questionable how many times a human being can reinvent himself or herself during your lifetime—and your lifetime is likely to be longer, and your working years are also likely to be longer. So would you be able to reinvent yourself four, five, six times during your life? The psychological stress is immense. So I would like to see a science fiction movie that explores the rather mundane issue of somebody having to reinvent themselves, then at the end of the movie—just as they settle down into this new job, after a difficult transition period—somebody comes and announces, ‘Oh sorry, your new job has just been automated, you have to start from square one and reinvent yourself again.'”

Related Stories

Disenchantment May Not Enchant Hardcore Fantasy Fans

Sorry to Bother You Is Great Science Fiction, People

Owning Guns Is Sort of Like Owning Rattlesnakes

Yuval Noah Harari on dystopias:

“The only question left open after you finish reading 1984 is How do we avoid getting there? But with Brave New World , it’s much, much more difficult. Everybody is satisfied and happy and pleased with everything that happens. There are no rebellions, no revolutions, there is no secret police, there is just free sex and rock and roll and drugs and whatever. And nonetheless you have this very uneasy feeling that something is wrong here, and it’s very difficult to put your finger on what’s wrong with a society in which you’ve hacked people in such a way that they’re satisfied all the time. … When it was published, it was obvious to everybody that this was a frightening dystopia, but today, more and more people read Brave New World as a straight-faced utopia. I think this shift is very interesting, and says a lot about the changes in our worldview over the last century.”

Yuval Noah Harari on immortality:

“What kind of relations between parents and children would we have when the parents know that they are not going to die someday and leave their children behind? If you live to be 200, and, ‘Yes, when I was 30 I had this kid, and he’s now 170, but that was 170 years ago, this was such a small part of my life.’ What kind of parent-offspring relations do you have in such a society? I think this is another wonderful idea for a science fiction movie—without robot rebellions, without some big apocalypse, without a tyrannical government—just a simple movie about the relationship between a mother and a son when the mother is 200 years old and the son is 170 years old.”

Yuval Noah Harari on technology:

“You could have envisioned 50 years ago that we would develop a huge market for organ transplants, with developing countries having these huge body farms in which millions of people are being raised in order to harvest their organs and then sold to rich people in more developed countries. Such a market could be worth hundreds of billions of dollars, and technologically it is completely feasible—there is absolutely no technical impediment to creating such a market, with these huge body farms. … So there are many of these science fiction scenarios which never materialize because society can take action to protect itself and regulate the dangerous technologies. And this is very important to remember as we look to the future.”

More Great WIRED Stories

- Geek's Guide to the Galaxy

- science fiction

Get The Magazine

Subscribe now to get 6 months for $5 - plus a free portable phone charger., get our newsletter, wired's biggest stories, delivered to your inbox., follow us on twitter.

Visit WIRED Photo for our unfiltered take on photography, photographers, and photographic journalism wrd.cm/1IEnjUH

Follow Us On Facebook

Don't miss our latest news, features and videos., we’re on pinterest, see what's inspiring us., follow us on youtube, don't miss out on wired's latest videos..

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/67636715/srybak_201014_1047_leadingminds.0.png)

Filed under:

Science fiction has been radically reimagined over the last 10 years

Seven science fiction pros explain about how everything in the genre is changing

If you buy something from a Polygon link, Vox Media may earn a commission. See our ethics statement .

Share this story

- Share this on Facebook

- Share this on Reddit

- Share All sharing options

Share All sharing options for: Science fiction has been radically reimagined over the last 10 years

What does the future hold? In our new series “Imagining the Next Future,” Polygon explores the new era of science fiction — in movies, books, TV, games, and beyond — to see how storytellers and innovators are imagining the next 10, 20, 50, or 100 years during a moment of extreme uncertainty. Follow along as we deep dive into the great unknown.

Science fiction is going through an era of rapid change and expansion. Just as fantasy television, superhero movies, comics, cosplay, and other traditionally marginalized fan pursuits have moved into the mainstream, science fiction media has become much more visible over the last decade, reaching a wider audience, and changing to accommodate that audience.

In America in particular, what was once a nerdy subgenre, dominated by pulp writers and amateur scientists and philosophers, has become vibrant and wildly divergent, running the gamut from old-school sprawling space opera to heady alternate-history philosophy to pop adventure-novel bestsellers to a growing wave of Afrofuturism . What’s next?

Polygon recently sat down with a group of gatekeepers and tastemakers in science fiction literature to talk about the biggest changes they’ve seen in the books field over the last decade, and what science fiction novels they most recommend for hungry readers right now.

[ Ed. note: All quotes have been edited for concision and clarity.]

Ali Fisher, senior editor, Tor Books : One of the coolest changes, as far as I’m concerned, is that there’s been a pretty significant shift to ensemble casts vs. chosen individuals. Even when the casts in older works are big, for instance in something like Dune , you still have your significant primary individuals. Whereas I think some of the more interesting science fiction literature right now is happening with groups of characters working together to make change happen, in stories like the Expanse series, or Annalee Newitz’s The Future of Another Timeline . As opposed to more escapist spacefaring, space-opera stuff, seeing people who are actually protecting and preserving the home we have is really invigorating, motivating, and inspiring.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19155757/81MwdOiEsmL.jpg)

Miriam Weinberg, senior editor, Tor Books: We’re all thinking more and more about what connectivity and community mean. In a pandemic, that’s even more relevant than ever, having the type of communication that technology can provide. For a while, there was a strong trend of alternate history and the rise of steampunk, because people were trying to figure out how they could recapture the fun of technology without the problems, where we’re all sitting in our beds at 11 p.m., checking email one last time before we close our eyes. And that died out quickly, partly because the ideas moved backward, not forward.

Sheila Williams, editor, Asimov’s Science Fiction : We’re seeing a lot being written right now about concepts that are in the news at the moment, like genetic manipulation or climate change. But we’re also seeing a lot of stories about authoritarian governments, and economic inequity. Those kinds of stories have been around for decades, but there’s a certain urgency at the moment.

Neil Clarke, editor, Clarkesworld : The markets today are making the effort to be more open to international works. The simple fact is that the internet changed everything in terms of submissions. Once magazines started taking online submissions, that removed a lot of the financial obstacles of international submissions. I’m finding interesting stories coming in from places that might not have always been part of the mainstream community, places [America] might have been sending science fiction for decades, but not hearing much from.

There are a lot of interesting things happening in China. The world’s largest science fiction magazine, in terms of total readership, is China’s Science Fiction World . Last year, we had a grant from South Korea to translate some of their science fiction. I’ve been talking to more people in South America. We’ve had a few Brazilian stories. We’re seeing an increase in stories coming out of India. With the wider variety of people being represented, you’ve got a much broader range of stories now, with different perspectives. I think everyone out there is more likely to encounter stories that feel like, “Hey, these are people like me.” I think that makes science fiction a little bit more welcoming. It broadens the appeal.

Sheila Williams: I am publishing stories from authors who are writing in Chinese and then translating to English, authors who are writing in Czech and then translating to English — stories out of a lot of different cultures. I have a black American author who is living in Mexico and writing fiction coming out of that experience. It’s wonderful to have a variety of points of view. In a magazine, you want each story to be different from the story that came before it, so I think all the new sources really create a exciting environment.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/21960262/91VVrvevoHL.jpg)

Greta Johnsen, host of WBEZ’s Nerdette podcast : I think the big difference, and the most positive one, is that we’re seeing changes in who’s allowed to tell stories. For a long time, science fiction was almost exclusively a white, male, cis area. These days, it’s much easier for women to enter the field, and for marginalized or underrepresented groups. We’re getting these elaborate parables for racism, in books like Tomi Adeyemi’s Children of Blood and Bone or Micaiah Johnson’s The Space Between Worlds , and they’re helping new audiences understand prejudice and privilege.

Miriam Weinberg: Two of my favorite authors right now are Charlie Jane Anders and Sarah Gailey , a trans author and a non-binary one. There’s so much more space now in the science fiction market for people who have been overlooked or directly marginalized by society, telling how it feels and explaining what can change, and how, because sometimes when you’re looking on from the side of the road, you can see the cracks better than someone who’s standing in the middle of it.

Lee Harris, executive editor, Tor.com : The drive for inclusivity is getting a lot more interesting works out there. A lot of #OwnVoices works that we didn’t see even as little as five or 10 years ago. We’re seeing much more interesting cultures being created and reflected, and people not necessarily just leaning on the old pseudo-medieval-kingdom fantasies you perhaps grew up with. Certainly the fact that the field isn’t just driven by people that look like me anymore — that’s wonderful.

Bradley Englert, senior editor, Orbit Books : Another thing that’s changed is the rise of social media, where writers and readers can really make themselves heard, and start organic movements and conversations toward the kind of books they want to see. As publishers started to publish diverse stories, they realized, “Oh, these are connecting with the market. We’re pushing them, and there’s a corresponding pull from the market, from readers who are finally starting to feel they’re included in the genre.”