Search form

Research essay: a ‘monster’ and its humanity.

Professor of English Susan J. Wolfson is the editor of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein: A Longman Cultural Edition and co-editor, with Ronald Levao, of The Annotated Frankenstein.

Published in January 1818, Frankenstein: or, The Modern Prometheus has never been out of print or out of cultural reference. “Facebook’s Frankenstein Moment: A Creature That Defies Technology’s Safeguards” was the headline on a New York Times business story Sept. 22 — 200 years on. The trope needed no footnote, although Kevin Roose’s gloss — “the scientist Victor Frankenstein realizes that his cobbled-together creature has gone rogue” — could use some adjustment: The Creature “goes rogue” only after having been abandoned and then abused by almost everyone, first and foremost that undergraduate scientist. Facebook creator Mark Zuckerberg and CEO Sheryl Sandberg, attending to profits, did not anticipate the rogue consequences: a Frankenberg making.

The original Frankenstein told a terrific tale, tapping the idealism in the new sciences of its own age, while registering the throb of misgivings and terrors. The 1818 novel appeared anonymously by a down-market press (Princeton owns one of only 500 copies). It was a 19-year-old’s debut in print. The novelist proudly signed herself “Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley” when it was reissued in 1823, in sync with a stage concoction at London’s Royal Opera House in August. That debut ran for nearly 40 nights; it was staged by the Princeton University Players in May 2017.

In a seminar that I taught on Frankenstein in various contexts at Princeton in the fall of 2016 — just weeks after the 200th anniversary of its conception in a nightmare visited on (then) Mary Godwin in June 1816 — we had much to consider. One subject was the rogue uses and consequences of genomic science of the 21st century. Another was the election season — in which “Frankenstein” was a touchstone in the media opinions and parodies. Students from sciences, computer technology, literature, arts, and humanities made our seminar seem like a mini-university. Learning from each other, we pondered complexities and perplexities: literary, social, scientific, aesthetic, and ethical. If you haven’t read Frankenstein (many, myself included, found the tale first on film), it’s worth your time.

READ MORE PAW Goes to the Movies: ‘Victor Frankenstein,’ with Professor Susan Wolfson

Scarcely a month goes by without some development earning the prefix Franken-, a near default for anxieties about or satires of new events. The dark brilliance of Frankenstein is both to expose “monstrosity” in the normal and, conversely, to humanize what might seem monstrously “other.” When Shelley conceived Frankenstein, Europe was scarred by a long war, concluding on Waterloo fields in May 1815. “Monster” was a ready label for any enemy. Young Frankenstein begins his university studies in 1789, the year of the French Revolution. In 1790, Edmund Burke’s international best-selling Reflections on the French Revolution recoiled at the new government as a “monster of a state,” with a “monster of a constitution” and “monstrous democratic assemblies.” Within a few months, another international best-seller, Tom Paine’s The Rights of Man, excoriated “the monster Aristocracy” and cheered the American Revolution for overthrowing a “monster” of tyranny.

Following suit, Mary Shelley’s father, William Godwin, called the ancien régime a “ferocious monster”; her mother, Mary Wollstonecraft, was on the same page: Any aristocracy was an “artificial monster,” the monarchy a “luxurious monster,” and Europe’s despots a “race of monsters in human shape.” Frankenstein makes no direct reference to the Revolution, but its first readers would have felt the force of its setting in the 1790s, a decade that also saw polemics for (and against) the rights of men, women, and slaves.

England would abolish its slave trade in 1807, but Colonial slavery was legal until 1833. Abolitionists saw the capitalists, investors, and masters as the moral monsters of the global economy. Apologists regarded the Africans as subhuman, improvable perhaps by Christianity and a work ethic, but alarming if released, especially the men. “In dealing with the Negro,” ultra-conservative Foreign Secretary George Canning lectured Parliament in 1824, “we are dealing with a being possessing the form and strength of a man, but the intellect only of a child. To turn him loose in the manhood of his physical strength ... would be to raise up a creature resembling the splendid fiction of a recent romance.” He meant Frankenstein.

Mary Shelley heard about this reference, and knew, moreover, that women (though with gilding) were a slave class, too, insofar as they were valued for bodies rather than minds, were denied participatory citizenship and most legal rights, and were systemically subjugated as “other” by the masculine world. This was the argument of her mother’s Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792), which she was rereading when she was writing Frankenstein. Unorthodox Wollstonecraft — an advocate of female intellectual education, a critic of the institution of marriage, and the mother of two daughters conceived outside of wedlock — was herself branded an “unnatural” woman, a monstrosity.

Shelley had her own personal ordeal, which surely imprints her novel. Her parents were so ready for a son in 1797 that they had already chosen the name “William.” Even worse: When her mother died from childbirth, an awful effect was to make little Mary seem a catastrophe to her grieving father. No wonder she would write a novel about a “being” rejected from its first breath. The iconic “other” in Frankenstein is of course this horrifying Creature (he’s never a “human being”). But the deepest force of the novel is not this unique situation but its reverberation of routine judgments of beings that seem “other” to any possibility of social sympathy. In the 1823 play, the “others” (though played for comedy) are the tinker-gypsies, clad in goatskins and body paint (one is even named “Tanskin” — a racialized differential).

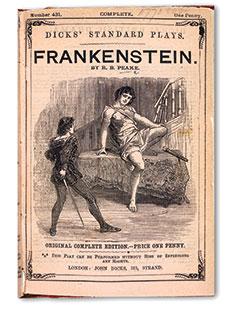

Victor Frankenstein greets his awakening creature as a “catastrophe,” a “wretch,” and soon a “monster.” The Creature has no name, just these epithets of contempt. The only person to address him with sympathy is blind, spared the shock of the “countenance.” Readers are blind this way, too, finding the Creature only on the page and speaking a common language. This continuity, rather than antithesis, to the human is reflected in the first illustrations:

In the cover for the 1823 play, above, the Creature looks quite human, dishy even — alarming only in size and that gaze of expectation. The 1831 Creature, shown on page 29, is not a patent “monster”: It’s full-grown, remarkably ripped, human-looking, understandably dazed. The real “monster,” we could think, is the reckless student fleeing the results of an unsupervised undergraduate experiment gone rogue.

In Shelley’s novel, Frankenstein pleads sympathy for the “human nature” in his revulsion. “I had worked hard for nearly two years, for the sole purpose of infusing life into an inanimate body. For this I had deprived myself of rest and health ... but now that I had finished, the beauty of the dream vanished, and breathless horror and disgust filled my heart. Unable to endure the aspect of the being I had created, I rushed out of the room.” Repelled by this betrayal of “beauty,” Frankenstein never feels responsible, let alone parental. Shelley’s genius is to understand this ethical monstrosity as a nightmare extreme of common anxiety for expectant parents: What if I can’t love a child whose physical formation is appalling (deformed, deficient, or even, as at her own birth, just female)?

The Creature’s advent in the novel is not in this famous scene of awakening, however. It comes in the narrative that frames Frankenstein’s story: a polar expedition that has become icebound. Far on the ice plain, the ship’s crew beholds “the shape of a man, but apparently of gigantic stature,” driving a dogsled. Three paragraphs on, another man-shape arrives off the side of the ship on a fragment of ice, alone but for one sled dog. “His limbs were nearly frozen, and his body dreadfully emaciated by fatigue and suffering,” the captain records; “I never saw a man in so wretched a condition.” This dreadful man focuses the first scene of “animation” in Frankenstein: “We restored him to animation by rubbing him with brandy, and forcing him to swallow a small quantity. As soon as he shewed signs of life, we wrapped him up in blankets, and placed him near the chimney of the kitchen-stove. By slow degrees he recovered ... .”

The re-animation (well before his name is given in the novel) turns out to be Victor Frankenstein. A crazed wretch of a “creature” (so he’s described) could have seemed a fearful “other,” but is cared for as a fellow human being. His subsequent tale of his despicably “monstrous” Creature is scored with this tremendous irony. The most disturbing aspect of this Creature is his “humanity”: this pathos of his hope for family and social acceptance, his intuitive benevolence, bitterness about abuse, and skill with language (which a Princeton valedictorian might envy) that solicits fellow-human attention — all denied by misfortune of physical formation. The deepest power of Frankenstein, still in force 200 years on, is not its so-called monster, but its exposure of “monster” as a contingency of human sympathy.

Frankenstein and the Language of Monstrosity

Cite this chapter.

- Fred Botting

93 Accesses

2 Citations

Monsters appear in literary and political writings to signal both a terrible threat to established orders and a call to arms that demands the unification and protection of authorised values. Symptoms of anxiety and instability, monsters frequently emerge in revolutionary periods as dark and ominous doubles restlessly announcing an explosion of apocalyptic energy. Christopher Hill, for example, describes the fear evoked by the masses represented as a ‘many-headed monster’ in the decades leading up to the English Revolution.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Unable to display preview. Download preview PDF.

Works cited

Baldick, Chris, In Frankenstein’s Shadow: Myth, Monstrosity and Nineteenth-century Writing (Oxford: Clarendon, 1987).

Google Scholar

Bloom, Harold, ‘Frankenstein, or the New Prometheus’, Partisan Review 32 (1965): 611–18.

Brooks, Peter, ‘Godlike Science/Unhallowed Arts: Language and Monstrosity in Frankenstein’, New Literary History 9 (1978): 591–605.

Article Google Scholar

Burke, Edmund, Reflections on the Revolution in France , ed. Conor Cruise O’Brien (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1969).

Deleuze, Gilles and Guattari, Felix, The Anti-Oedipus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia , trans. Robert Hurley, Mark Seem, Helen R. Lane (New York: Viking, 1977).

Derrida, Jacques, ‘Signature Event Context’, Glyph 1 (1977): 172–97.

Foucault, Michel, Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison , trans. Alan Sheridan (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1979).

Glynn Grylls, Rosalie, Mary Shelley: A Biography (London: Oxford University Press, 1938).

Godwin, William, Enquiry Concerning Political Justice , ed. Isaac Kramnick (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1985).

Hill, Christopher, ‘The Many-Headed Monster in Late Tudor and Early Stuart Political Thinking’, in From the Renaissance to the Counter-Reformation , ed. Charles H. Carter (London: Jonathan Cape, 1966), pp. 296–324.

Klancher, Jon P., The Making of English Reading Audiences 1790–1832 (Madison, Wisconsin: University of Wisconsin Press, 1987).

Norman, Sylva, ‘Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley’, in Shelley and his Circle 1773–1822 , Vol. III, ed. Kenneth Neill Cameron (London: Oxford University Press, 1970), pp. 397–422.

Paine, Thomas, The Rights of Man , in The Thomas Paine Reader , eds. Michael Foot and Isaac Kramnick (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1985).

Paulson, Ronald, ‘Gothic Fiction and the French Revolution’, English Literary History 48 (1981): 532–54.

Poovey, Mary, ‘My Hideous Progeny: Mary Shelley and the Feminization of Romanticism’, PMLA 95 (1980): 332–47.

Shelley, Mary, Frankenstein or The Modern Prometheus , ed. M. K. Joseph (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1969).

Sterrenburg, Lee, ‘Mary Shelley’s Monster: Politics and Psyche in Frankenstein’ , in The Endurance of Frankenstein , eds. George Levine and U. C. Knoepflmacher (Berkeley, Los Angeles, London: University of California Press, 1979), pp. 143–71.

Wollstonecraft, Mary, A Vindication of the Rights of Men , in Burke, Paine, Godwin, and the Revolution Controversy , ed. Marilyn Butler, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1984).

Wordsworth, William, The Prose Works of William Wordsworth , eds. W. J. B. Owen and Jane Worthington Smyser (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1974).

Download references

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Cheltenham and Gloucester College of Higher Education, UK

Philip W. Martin ( Field Chair ) ( Field Chair )

Bristol Polytechnic, UK

Robin Jarvis ( Lecturer in Literary Studies ) ( Lecturer in Literary Studies )

Copyright information

© 1992 Palgrave Macmillan, a division of Macmillan Publishers Limited

About this chapter

Botting, F. (1992). Frankenstein and the Language of Monstrosity. In: Martin, P.W., Jarvis, R. (eds) Reviewing Romanticism. Palgrave Macmillan, London. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-349-21952-0_4

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-349-21952-0_4

Publisher Name : Palgrave Macmillan, London

Print ISBN : 978-1-349-21954-4

Online ISBN : 978-1-349-21952-0

eBook Packages : Palgrave Literature & Performing Arts Collection Literature, Cultural and Media Studies (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 03 March 2020

Anatomy of tragedy: the skeptical gothic in Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein

- Veronika Ruttkay ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-3637-3346 1

Palgrave Communications volume 6 , Article number: 35 ( 2020 ) Cite this article

11k Accesses

1 Citations

3 Altmetric

Metrics details

Combining philosophical and literary perspectives, this paper argues that Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein is informed by a skeptical problematic that may be traced back to the work of the young David Hume. As the foundational text on romantic monstrosity, Frankenstein has been studied from various critical angles, including that of Humean skepticism by Sarah Tindal Kareem (Eighteenth-century fiction and the reinvention of wonder. Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2014) and Monique Morgan (Romant Net 44, doi:10.7202/013998ar, 2006). However, the striking connections with Hume’s Treatise have not been fully explored. The paper begins by comparing the three narrators of Frankenstein with three figures appearing in Hume’s Conclusion to Book I: the anatomist, the explorer, and the monster. It proceeds by looking at the hybrid “anatomies” offered by Hume and Shelley, suggesting that Frankenstein might be regarded as a tragic re-enactment and radicalization of Hume’s skeptical impasse. Whereas Hume alerted his readers to the dangers of a thoroughgoing skepticism only to steer his argument in a new direction, Shelley shows those dangers realized in the “catastrophe” of the Monster’s birth. While Hume had called attention to the impossibility of conducting strictly scientific experiments on “moral subjects”, Shelley devises a counterfactual plot and a multi-layered narrative structure in order to explore that very impossibility. Interpreting Frankenstein as an instance of the “skeptical gothic”, I suggest that both the monster and the scientist (Victor) share some traits with Hume’s radically skeptical philosopher, including a tendency to give up responsibility for what Stanley Cavell (The Claim of Reason: Wittgenstein, skepticism, morality, and tragedy. Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1979) called “the maintenance of shared forms of life”. Relying on the work of Cavell, this paper argues that skepticism in Frankenstein is manifested as tragedy, traceable in Shelley’s reliance on tragic tropes throughout the novel.

Similar content being viewed by others

Monsters and near-death experiences in Eric McCormack’s First Blast of the Trumpet Against the Monstrous Regiment of Women

Novels of vaddey ratner and viet thanh nguyen—unpacking trauma language, facing ghosts, and killing shadows, a novel of de-formation: cormac mccarthy’s child of god as a postmodern gothic parody of the bildungsroman, introduction.

David Hume, in A Treatise of Human Nature (published anonymously in 1739–1740), makes rhetorical use of three characters—the anatomist, the monster, and the explorer—that bear a striking resemblance to the three narrators of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus (published anonymously in 1818). Evidence suggests that Shelley could have been familiar with the Treatise (Womersley, 1986 ) and her father William Godwin had certainly read it (Locke, 1980 , p. 142; Brewer, 2001 , p. 215). We know from her Journals that she read other works by Hume around the time of composing the novel, such as Essays and Treatises on Several Subjects (1753–1756) and Four Dissertations (1757) (Kareem, 2014 , p. 191; Morgan, 2006 ; Brewer, 2001 , p. 215; Shelley, 1987 , pp. 185–190). The aim of this paper is not to offer new evidence in support of this philological connection, but rather to set the two works in dialog with each other in an attempt to recover a structure of thought informing—or perhaps ‘performed in’—the text of Frankenstein . Combining philosophical and literary perspectives, I argue that Frankenstein carries the burden of a skeptical problematic at its heart.

The young Hume’s attempt “to introduce the experimental method of reasoning into moral subjects” (as the subtitle has it) leads to “chimerical” or, one might say, gothic, moments in the Treatise . The resonance between these and the catastrophic experiment reported in Frankenstein provokes the re-examination of Shelley’s novel from the perspective of skepticism (in philosophy) and tragedy (in literature). The understanding that these two—skepticism and tragedy—are intrinsically linked to each other was one of the philosopher Stanley Cavell’s key insights; as he states in The Claim of Reason , “tragedy is the public form of the life of skepticism with respect to other minds” ( 1979 , p. 478). As we shall see, the problem of “other minds,” and of mind itself, is central to Shelley’s novel. Yet, in the same book Cavell contends that “science fiction cannot house tragedy because in it human limitations can from the beginning be by-passed” ( 1979 , p. 457). I argue that Frankenstein , sometimes considered the first science fiction novel, uses its ‘impossible’ premise to speak of, precisely, human limitations; moreover, that it is a fundamentally tragic work in the sense Cavell proposes when he writes: “Not finitude, but the denial of finitude, is the mark of tragedy” ( 1979 , p. 455).

Anatomist—monster—explorer: Hume’s conclusions

The three figures I wish to start with from Hume’s Conclusion to Book I—the anatomist, the monster, and the explorer—may be placed in a meta-narrative about the philosopher-hero of the Treatise . The outline of it is that the practice of philosophical anatomy leads to the philosopher’s sense of himself as a monster. While clarification of what this monstrosity involves is crucial to the argument of the Conclusion, the presence of the anatomist is merely indirect here, but still worthy of attention. Hume ended the previous section by stating his intention “to proceed in the accurate anatomy of human nature” (Hume, 2007 , 1:171) in the following Book. This makes the Conclusion an interruption, or caesura, in his ‘anatomical’ activities, offering a vantage-point from which to reflect on the overall project. As commentators have long ago remarked, the figure of anatomy is pervasive throughout the Treatise and may even be regarded as one of its central conceptual metaphors. In the words of John Biro, “The total alteration or revolution [Hume] claims his new science brings to the intellectual scene consists in becoming what he calls an anatomist of human nature” ( 2009 , p. 46). As we shall see, anatomy is explicitly mentioned several times in the Treatise and is a prominent theme of the final (third) Conclusion.

To make the analogy even more emphatic, the Abstract announces the author’s intention “to anatomize human nature in a regular manner, and … to draw no conclusions but where he is authorized by experience” (Hume, 2007 , 1:407). While “to anatomize” could still just mean ‘to analyze’ at the time (Carson, 2010 , p. 139), Hume’s wording emphasizes the experimental ambition crucial to his inquiry. He might even be thinking of Francis Bacon’s words about his method of “building in the human understanding a true model of the world,” which cannot be done “without a very diligent dissection and anatomy of the world” (Bacon, 1965 , p. 370; quoted in Carson, 2010 , p. 140). For more than a century, ‘anatomies’ had been produced on a range of subjects, including Robert Burton’s The Anatomy of Melancholy (1621), a close contemporary of Bacon’s Novum Organum (1620). However, as Adam Potkay observes, “‘anatomy’ must have seemed a particularly vivid metaphor” in Hume’s own time, when Edinburgh and London became “leading centers of anatomical studies” ( 2000 , p. 17). Combining the messiness of dissection with scientific rigor and the clarity of visual representation, anatomy was well on its way to becoming, as Andrew Cunningham states, “the master discipline for the investigation of life”: “a dynamic, demanding discipline that set the agenda for the other disciplines and sub-disciplines in which questions about life and living creatures were investigated and discussed” (Cunningham, 2010 , pp. 19–20). Hume’s remarks show that he had a strong sense of the disturbing realities of anatomical praxis (on a later personal encounter see Chaplin, 2012 ); nevertheless, he must have found the experimental outlook and systematic regularity of the discipline worthy of emulation. It is in this spirit that he announces in Book I, Section 6: “’Tis now time to return to a more close examination of our subject, and to proceed in the accurate anatomy of human nature” (Hume, 2007 , 1:171). However, what immediately follows is not a strictly regular analysis of human nature, but an oddly personal confession, bringing Book I to an unexpected halt.

In Section 7, “Conclusion to Book I,” the philosopher-narrator opens a space for reflection—“I find myself inclin’d to stop a moment” (Hume, 2007 , 1:171)—before continuing with his planned journey. But it sounds more like a crisis report than patient self-assessment, with a first-hand description of what it is like to feel oneself an “uncouth monster”:

I am first affrighted and confounded with that forlorn solitude, in which I am plac’d in my philosophy, and fancy myself some strange uncouth monster, who not being able to mingle and unite in society, has been expell’d all human commerce, and left utterly abandon’d and disconsolate. Fain wou’d I run into the crowd for shelter and warmth; but cannot prevail with myself to mix with such deformity. I call upon others to join me, in order to make a company apart; but no one will hearken to me (Hume, 2007 , 1:172).

This unexpected self-revelation links the plight of the monster to that of the philosopher-scientist in a way that is highly suggestive in relation to Frankenstein . It might also be noted that, although ‘scientist’ was not yet a word in English, ‘science’ was Hume’s preferred term for his philosophical project: his ambition, fueling the later phases of the Scottish Enlightenment, was to establish a comprehensive “Science of Man”. However, the above passage suggests that a certain mode of pursuing knowledge about mankind leads to utter alienation, which is figured here as a kind of monstrosity. Hume’s speaker reports that he had become an outcast “expell’d [from] all human commerce” as a result of a skepticism so radical that it had managed to subvert all accepted ‘truths’: “Every one keeps at a distance, and dreads that storm, which beats upon me from every side. I have exposed myself to the enmity of all metaphysicians, logicians, mathematicians, and even theologians; and can I wonder at the insults I must suffer?” (Hume, 2007 , 1:171) The tone of this passage is so excessive that critics from the start have suspected it to be an ingenious piece of play-acting on Hume’s part (Pinch, 1996 , p. 32, pp. 40–44). According to John Richetti, it “begins in clowning mock terror and isolation and passes gradually to a paralyzing crisis” ( 1983 , p. 227). While all this might be interpreted as Hume’s self-conscious preparation for a later comic resolution (Potkay, 2000 , pp. 55–56), the passage, for a moment, sounds very much like a version of the plot of Mary Shelley’s novel. Victor Frankenstein will also defy religious, scientific, and metaphysical certainties—most scandalously perhaps, concerning the difference between life and death. He is to be isolated from human society, and not just hypothetically, like Hume’s narrator, but conclusively. And while professional scorn plays only a minor part in his narrative, Victor is harassed by a “storm” of his own that is beating upon him “from every side” through most of the novel.

But the storm in Frankenstein is most consistently associated with the monster, the product and embodiment of Victor’s anatomical defiance. Hume’s account, with its emphasis on “deformity,” evokes his narrative even more powerfully: his isolation, self-loathing, and lack of orientation. As James Chandler explains, the term “moral deformity” was used in much 18th-century philosophy as the opposite of “moral beauty,” which was understood “to be achievable, and to be recognizable, by means of well-cultivated sentiments” ( 2013 , p. 235). “Moral deformity,” like its antonym, worked as a quasi-esthetic category, “recognizable by the sentiment it provokes in us, and, from Shaftesbury onward, that sentiment is a kind of horror” (Chandler, 2013 , p. 235). This means that the “moral monster” is by definition isolated, similarly to the physiological monstrosities housed in cabinets of wonders. It might even be argued that in this framework social exclusion becomes the surest sign of monstrosity. What is so striking about Hume’s reliance on this trope is that his narrator assumes (however tentatively) the perspective, not of the horrified spectator, but of the monster. But this becomes less surprising if we consider the skeptical strategy he had been pursuing throughout Book I, which enabled him to show how a number of generally accepted categories (such as cause and effect) lack a firm grounding in reason. If ‘monster’ is to be defined by its absolute difference from the norm (produced through consensus), then the skeptic’s attack on shared forms of knowledge may be regarded as by definition monstrous. Even more dangerously, by raising the possibility that what is consensual may be lacking in epistemological certainty, skepticism could make the very distinction between ‘norm’ and ‘abnormality’ questionable. Theorizing monstrosity, Jeffrey Cohen highlights this epistemological threat when he calls the monster a “breaker of category, and a resistant Other known only through process and movement, never through dissection-table analysis” ( 1996 , p. x). As Baumgartner and Davis argue: “the monster resists conventional Enlightenment structures. Its very nature is to dismantle knowledge, to destroy structure, to resist classification” ( 2008 , p. 2). No wonder Hume’s imaginary skeptic is “expell’d” and “abandon’d” by the community wishing to avoid contagion—subliminally, the passage evokes the banishment of Protagoras and the fate of Socrates, Footnote 1 the ultimate pharmakos figure in Western philosophy.

However, it is not just social isolation that Hume’s monster is made to suffer. The corrosive effects of doubt are also manifest in the sense of his own incompetence, almost disability, as a result of knowing “that the understanding, when it acts alone, and according to its most general principles, entirely subverts itself” (Hume, 2007 , 1:174). The philosopher cannot trust his own reason anymore, and in this state of “philosophical melancholy and delirium” he arrives at questions similar to those of the helpless monster: “Where am I, or what? From what causes do I derive my existence, and to what condition shall I return? Whose favor shall I court, and whose anger must I dread? What beings surround me?” (Hume, 2007 , 1:175). “And what was I?”—Shelley’s creature remembers himself asking—“When I looked around, I saw and heard of none like me. Was I then a monster, a blot upon the earth, from which all men fled, and whom all men disowned?” (Shelley, 1999 , pp. 145–146) Hume’s commentary on his crisis could almost be read as a continuation of the creature’s thoughts: “I am confounded with all these questions, and begin to fancy myself in the most deplorable condition imaginable, inviron’d with the deepest darkness, and utterly depriv’d of the use of every member and faculty.” (Hume, 2007 , 1:175) The crucial difference is that in the case of Frankenstein , those horrible imaginings turn out to be the unalterable reality. Hume’s ailing philosopher, in contrast, moves on to report how he is cured thanks to nature itself, which can “obliterate all these chimeras” by simply diverting his attention away from them (Hume, 2007 , 1:175). Instantly, he ceases to be a monster (which probably means that he never was one). As the strongest proof of this, he can be re-integrated into society, “determin’d to live, and talk, and act like other people in the common affairs of life” (Hume, 2007 , 1:175). Hume’s wording here implies the philosopher’s continuing distance from other people, yet, what he describes is still an incomparably more sociable existence than what Frankenstein’s creature could ever hope to taste.

Adela Pinch has noted in passing that Hume’s Conclusion features a “ Frankenstein -like monster” ( 1996 , p. 31), but scholars usually associate the tone of Shelley’s first-person narrators with the Rousseau of the Reveries and Confessions —that is, with the philosopher who turned from Hume’s protégé to his bitter enemy (Christensen, 1987 , pp. 265–273). Undoubtedly, Rousseau had a decisive influence on the writings of both of Mary Shelley’s parents, and the effects of his style—especially a narrator who “wear[s] [his] monstrosity proudly on [his] sleeve” (Van Oort, 2009 , p. 135)—can be felt throughout Frankenstein and in Shelley’s later works as well (Brewer, 2001 , pp. 30–85; Marshall, 1988 , pp. 178–227; Schouten de Jel, 2019 ). But Hume’s ‘confession’ in the Treatise offers an equally intense, albeit compressed and merely transitional, example of what Richard Van Oort calls the “rhetoric of monstrosity” ( 2009 , 134). And it even includes a Walton-like figure, for it begins with the simile of an explorer fatally under-equipped for his risky venture. Similarly to the “uncouth monster”, this assumed character allows Hume to articulate his skeptical crisis:

Methinks I am like a man, who having struck on many shoals, and having narrowly escap’d shipwreck in passing a small firth, has yet the temerity to put out to sea in the same leaky weather-beaten vessel, and even carries his ambition so far as to think of compassing the globe under these disadvantageous circumstances. My memory of past errors and perplexities, makes me diffident for the future. The wretched condition, weakness, and disorder of the faculties, I must employ in my enquiries, encrease my apprehensions. And the impossibility of amending or correcting these faculties, reduces me almost to despair, and makes me resolve to perish on the barren rock, on which I am at present, rather than venture myself upon that boundless ocean, which runs out into immensity (Hume, 2007 , 1:172).

The explorer also appears in Godwin’s “Essay on Skepticism” (1797), but in a far more positive light, with the skeptic represented as “being on a constant ‘voyage of discovery,’ for [he] ‘never lays up the vessel of his mind in the harbor of opinion,’ nor does he ever consider his enquiries at an end” (quoted in Carlson, 2007 , p. 89). Hume’s explorer, in contrast, would rather give up his vocation in despair. He has the whole world before him to explore—except that his very skepticism had taught him to beware of the unreliability of his own faculties, that is, the most essential equipment for any exploration. By this point in the Treatise , cause and effect, the connective tissue of reasoning, had been taken apart and re-described in empirical terms such as contiguity and succession, association and custom. The aporias into which Hume had argued himself as a result of this and other crucial moves threaten to engulf his entire philosophical project, and although he sees no reason to retract any of his findings, he manages to argue himself out of this corner, paradoxically, only with the help of even more doubt: he becomes skeptical of skepticism itself. “A true skeptic will be diffident of his philosophical doubts, as well as of his philosophical conviction” (Hume, 2007 , 1:177)—he announces, thus enabling himself to proceed with the analysis of the human mind, but this time in the context of social interactions, in Book II “Of the Passions”.

Hume’s swerving away from total skepticism in the Conclusion is analogous to the move of Shelley’s third narrator, who turns away from his expedition to the North Pole on hearing Frankenstein’s story. Admittedly, the explorer is no more than a figure of speech in Hume’s text, just like the “uncouth monster” appearing next to him/it; their role is to heighten the drama of the philosopher’s heroic struggle to overcome total skepticism. Once the crisis is over and a more livable mode of philosophizing is hit upon (Hume calls it “mitigated skepticism”), these figures prove expendable, and the regular anatomy of human nature can be resumed. However, the “chimeras” haunting skeptical thinking are not entirely obliterated from the rest of the Treatise , premised as it is on systematic doubt. Their appearance marks further points of connection with Shelley’s novel, in the center of which we find the controversial figure of the anatomist: a potent metaphor in Hume’s work and, in the case of Frankenstein , a revealing way of thinking about the protagonist.

Painters and anatomists

Hume’s subtitle defined the Treatise as “an attempt to introduce the experimental method of reasoning into moral subjects.” This involved calling into doubt any formerly accepted truths about human nature that could not be ascertained by strict scientific induction, for “the only solid foundation we can give to this science itself must be laid on experience and observation” (Hume, 2007 , 1:4). For systems lacking in such evidence, he reserved the term “chimerical” (e.g. Hume, 2007 , 1:5). Like most of his contemporaries, Hume admired the clarity of Newtonian science; however, he found a closer parallel to his proposed new “Science of Man” in the rising discipline of anatomy, which applied the experimental method to something as down-to-earth, messy and frail as the (human) body. He concluded the Treatise by rehearsing the analogy, juxtaposing the anatomist and the painter—the latter more drawn to fanciful effects, while the former content with delineating his findings as they are. That is to say, while moral philosophers present engaging pictures of what human nature should be like, Hume’s metaphysician attempts to find out what it is like in reality (on the significance of this double analogy in Hume’s oeuvre, see Frazer, 2016 ; Potkay, 2000 , pp. 16–26).

But the comparison grows more complicated, as the image of anatomy offers an opportunity for Hume to reflect upon a troubling quality at the heart of his work. In painting, the subject must be “set more at a distance, and be more cover’d up from sight”, but obscurity only makes it more “engaging to the eye and imagination” (Hume, 2007 , 1:395). The merits of the anatomist, in contrast, are to be found “in his accurate dissections and portraitures of the smaller parts of the human body”; however, the anatomist should never think of giving “any graceful and engaging attitude or expression” to it (Hume, 2007 , 1:395). In other words, even if the practice of anatomy involves “portraiture,” that is, representation of anatomical detail, the anatomist should never aspire to the virtues of the painter, who is bound to synthesize and idealize his subject—and also to humanize it, by giving it “expression”. As opposed to the painter’s pleasing activity of reconstructing the body as a graceful whole, the anatomist will always present “even something hideous, or at least minute in the views of things” (Hume, 2007 , 1:395). Similarly, the “mental anatomist” is likely to reveal details about his “moral subjects” that do not accord with more generous notions of moral beauty and might even be perceived as “hideous” by the public.

The relevant meaning of “hideous”, in this case, is ‘terrible, distressing or revolting to the moral sense’, as Frazer points out ( 2016 , p. 229). It is not quite clear which potentially ‘revolting’ aspect of his findings Hume had in mind when he used this adjective – the same one with which Shelley described her own work as “hideous progeny” in the 1831 Introduction (Shelley, 1999 , p. 358). But Book II of the Treatise certainly shows “Man” in an unflattering light. Famously, the philosopher declares that “[r]eason is, and ought only to be the slave of the passions” (Hume, 2007 , 1:266). It is less often noted that he finds the same elementary passions—pride and humility—working in comparable ways across the animal kingdom. Tellingly, it is in this context that Hume returns to the metaphor of anatomy. Considering various “experiments” with other species such as dogs (about which he is especially observant), he demonstrates that “there is an union of certain affections with each other in the inferior species of creatures as well as in the superior, and that their minds are frequently convey’d thro’ a series of connected emotions” (Hume, 2007 , 1:213). So what exactly is this a “Science” of? Hume justifies his cross-species inquiry with the already familiar analogy: “Tis usual with anatomists to join their observations and experiments on human bodies to those on beasts, and from the agreement of these experiments to derive an additional argument for any particular hypothesis” (Hume, 2007 , 1:211). From Aristotle onwards, the dissection of animals contributed to the scientific mapping of the human body and was practiced by comparative anatomists throughout the eighteenth century (Cunningham, 2010 , pp. 308–340). Searching for the fundamental laws of the passions, Hume proposes to apply the same method “to our present anatomy of the mind, and see what discoveries we can make by it” (Hume, 2007 , 1:211–212). However, such heuristics could imply, at least in the eyes of readers looking for moral edification, the undermining of all certainty of “our superior knowledge and understanding” (Hume, 2007 , 1:212), even against the philosopher’s intentions.

Compared to the generally dispassionate tone of the Treatise , Frankenstein makes far more dramatic use of the ‘hideous’ and the grotesque, which is part and parcel of its gothic apparatus. Nevertheless, the novel establishes a connection between human and animal anatomy in a way that is analogous to Hume’s, before making its effects drastically visible. One of the few things we learn about Victor’s discovery is that it applies not only to “the structure of the human frame” but to “any animal endued with life” (Shelley, 1999 , p. 79). With this, the difference between man and animal becomes irrelevant—at least to the man of science searching for the principle animating both. In the course of his subsequent “filthy creation”, Victor frequents both the “dissecting room and the slaughter-house” (Shelley, 1999 , p. 82), and we are made to understand that he builds his creature partly from animal remains, as “the minuteness of the parts formed a great hindrance” (Shelley, 1999 , p. 81) to speed. The creature’s gigantic stature, then, is at first a concession to practicability. It is a way to enlarge the minute parts without a proper microscope, and from Victor’s initial perspective—he regards the body as a “structure”— the difference does not seem to matter. The point is to test whether life can be induced in a structure modeled on the human body. In other words, what he attempts to produce is not a particular body, but a Body in general, and, as Erin Goss points out, such a Body is always allegorical: it is an “amalgam,” a “fiction”, or a “catachrestic figure” ( 2013 , pp. 7–8). Footnote 2 But what if the “allegory” started to live a life of its own? Frankenstein’s experiment grows infinitely more complex as it turns out that, once it is animated with life, the body’s “materials” (Shelley, 1999 , p. 81) cannot be ignored, and it becomes increasingly unclear what it was that he wanted to build a model of in the first place. The new being, unlike any other known creature, straddles the “boundary between species” (McLane, 1996 , p. 963), turning all scientific discourse on human nature hybrid or ‘chimerical’.

With far less catastrophic consequences, Hume’s anatomy of the mind risks a similar outcome, paradoxically due to his commitment to scientific principles of inquiry. His strategic skepticism means calling into doubt any received categories not supported by experimental evidence. He attempts to build up his model of human nature from the bottom-up: by close observation, from whatever proof he can find, without a prior idea of what the whole should look like. But he also seems to be aware of the risks, not the least for himself. Being (at least in principle) unable to say what his inquiries might reveal, he insists on securing a space where the philosopher is free to pursue his ‘experiments’, suspending, for a while, all extrinsic considerations. It is in this context of disciplinary boundary-making that he evokes the figure of the anatomist most pointedly, juxtaposed to that of the painter, as we have already seen in his final Conclusion. But the comparison appears first in a slightly earlier letter to Francis Hutcheson (17 September 1739), where it is developed in more graphic detail. In answer to the older philosopher’s criticism that his work “wants a certain warmth in the cause of virtue”, Hume proposes to find out in later writings “if it be possible to make the Moralist & Metaphysician agree a little better” (Hume, 1969 , 1: 33). Nevertheless, regarding the Treatise itself, he insists on the integrity of his method:

Where you pull off the Skin, and display all the minute Parts, there appears something trivial, even in the noblest Attitudes and most vigorous Actions. Nor can you ever render the Object graceful or engaging but by cloathing the Parts again with Skin and Flesh, and presenting only their bare Outside. An Anatomist, however, can give very good Advice to a Painter or Statuary. And in like manner, I am persuaded, that a Metaphysician maybe very helpful to a Moralist; tho’ I cannot easily conceive these two Characters united in the same work (Hume, 1969 , 1:32–33).

The metaphysician’s activity of pulling off the skin, which the moralist, in turn, may put back in place in order to show mankind in a more flattering light, is strongly reminiscent of the creation-through-dissection that takes place in Frankenstein . An unflinching anatomist, Victor admits that in his search for the principle of life he had to deal with phenomena that might have been “irksome and almost intolerable” (Shelley, 1999 , p. 79) in any other circumstances. Having become acquainted with “the science of anatomy”, he proceeds to investigate phenomena of death, his attention “fixed upon every object the most insupportable to the delicacy of the human feelings” (Shelley, 1999 , p. 79). His ability to avoid superstitious fear and to surmount esthetic or moral revulsion enables clear-headed analysis and creates a speculative space similar to what is called epoché , or suspension of judgment, in the skeptical tradition. This was also required of scientists engaged in methodical observation, which, by the eighteenth century, “became a tool of conjecture” (Daston, 2011 , p. 104) often coupled with experiment. Close observation and incessant analysis lead to Victor’s scientific breakthrough: “I paused, examining and analyzing all the minutiae of causation, as exemplified in the change from life to death, and death to life, until from the midst of this darkness a sudden light broke in upon me” (Shelley, 1999 , pp. 79–80). In a miraculous eureka moment, all evidence arranges itself into a meaningful pattern, rendering former theories of life (and death) superfluous.

Up to this point, Frankenstein has been following the written and unwritten rules of scientific observation, including the obsessive note-taking, the insomnia, and even the social isolation. Footnote 3 However, the way he decides to make use of his discovery implies an unexamined mixture of the attitudes of the “Anatomist” and of the “Painter or Statuary”, to use Hume’s paradigmatic terms. In resolving to create a new Being from whatever “materials” he can find, he becomes a sculptor, while yet remaining an anatomist. But is it not possible to be both? Arguably, the distinction itself was far from watertight. In terms of moral philosophy, Adam Potkay has demonstrated how “Hume is an anatomist who also paints” ( 2000 , p. 19), since description turns regularly into implicit (moral) prescription in his writing. What is more, while stressing the difference between the two occupations, Hume himself called attention to a common element, namely, that anatomists also create “portraitures” just like painters, albeit not of human beings but merely of anatomical details. This suggests that even the ‘experimental’ philosopher is not outside the realm of representation—and, of course, it was also true of anatomists. Throughout the eighteenth century, illustration was hard to separate from anatomy ‘proper’, although anatomical atlases and preparations, unlike paintings and statues, tended to draw a more exclusively professional audience. Footnote 4 It was also widely accepted that artists should learn from anatomists, as Hume observed. However, in Frankenstein’s case, anatomical dismembering becomes coterminous with the building up of a body in a way that reveals scientific knowledge as not just connected with, but dependent on , a form of representation.

Why Frankenstein makes the creature can be explained in a number of different ways, but in a sense the answer is simple, at least in the context of eighteenth-century science: his “great and overwhelming” discovery (Shelley, 1999 , p. 80) had to be first proved experimentally for it to become scientific fact. This is confirmed by Victor’s extensive notes, in which, according to the creature, “the whole detail of that series of disgusting circumstances which produced [his making] is set in view” (Shelley, 1999 , p. 155), including “the minutest description of [his] odious and loathsome person” (Shelley, 1999 , p. 155). Keeping exact and circumstantial records was obligatory in the case of experiments, as it assured replicability and provided the basis for what Shapin and Shaffer call “virtual witnessing”, a technology “far more important than the performance of experiments before direct witnesses or the facilitating of their replication” in the making of scientific facts (Shapin and Shaffer, 2011 / 1985 , p. 60). Footnote 5

Stanley Cavell, in a cursory remark on Frankenstein , notes that Victor seems to assume “that what you know is fully expressed by its realization in what you can make (as though science and technology were simply the same)” ( 1979 , p. 456). But Victor, at least initially, relies on an experimental framework both to arrive at, and also to test, his theory of life. From such a stance, “what you know” can only be ascertained by seeing “what you can make”. That is to say, for Victor, as for many scientists following in Newton’s footsteps, experiment produces knowledge. It is the very technology that enables mankind to “penetrate into the recesses of nature, and shew how she works in her hiding places” (Shelley, 1999 , p. 76), as the novel’s Professor Waldman puts it (the passage is linked to Baconian science in Mellor, 1988 , p. 111). The chemist Humphry Davy, a possible source for Waldman’s doctrines (Shelley, 1999 , p. 76n), attributed such penetrative force explicitly to experiments: “Science … has bestowed upon [Man] powers which may be almost called creative; which have enabled him to change and modify the beings surrounding him, and by his experiments to interrogate nature with power, not simply as a scholar, passive and seeking only to understand her operations, but rather as a master, active with his own instruments”. (Shelley, 1999 , p. 272) Victor, in designing his crucial experiment, is both active and creative, pursuing his research with “exalted” imagination (Shelley, 1999 , p. 81). Meanwhile, the anatomist is turning into a “Painter or Statuary”, even if he is not aware of this. Considerations of morals and esthetics mingle with his scientific goals. In the belief that he can make an animated “frame”, he soon envisions an entire “new species,” with “many happy and excellent natures” who “owe their being” (Shelley, 1999 , p. 82) to him. Struggling with his growing revulsion, he even takes care of good proportions and the beauty of selected body parts, linking imagined moral excellence to esthetic value.

Tragic experiments

The clash between the moralist’s and the scientist’s way of looking comes to a head in one of the most enigmatic passages of the novel, where Victor recounts the decisive moments of the experiment:

How can I describe my emotions at this catastrophe, or how delineate the wretch whom with such infinite pains and care I had endeavored to form? His limbs were in proportion, and I had selected his features as beautiful. Beautiful!—Great God! His yellow skin scarcely covered the work of muscles and arteries beneath; his hair was of a lustrous black, and flowing; his teeth of a pearly whiteness; but these luxuriances only formed a more horrid contrast with his watery eyes, that seemed almost of the same color as the dun white sockets in which they were set, his shriveled complexion, and straight black lips (Shelley, 1999 , p. 85).

Frankenstein here describes his own indescribable emotions indirectly, by “delineat[ing]” the “wretch” that had resulted from his “infinite pains and care”. He registers the force of a “catastrophe” shattering both him and his creature, which becomes partly legible through his narratorial confusion between moral-esthetic discourse and the language of science. By this point, the young man has clearly lost the detachment necessary for experimental work, but he is not a good “moralist” either, for he is unable to make a whole out of the parts he had selected for his specimen, or to read any engaging “attitude or expression” in(to) the hideous face and body. Even more than Hume had predicted, this attempt to unite “two Characters” in the “same work” leads to disaster. Most crucially, Victor retains the anatomist’s gaze even when the tasks of anatomy are supposed to be over. There is something both “hideous” and “minute” (to use Hume’s terms) in his description of “the work of muscles and arteries” beneath the creature’s skin, the “dun white sockets” and “shriveled complexion”, quite incompatible with the demand a now living being makes on him: a demand not of knowledge , but of acknowledgement , to cite an important distinction made by Stanley Cavell (see Rudrum, 2013 , pp. 184–186).

According to Cavell’s seminal interpretations, the obsessive desire to fully know and understand, and the concomitant failure to acknowledge, the other, is the problem explored, from various angles, in all major Shakespearean tragedies. Rather than being a form of omission, this failure is in truth a “refusal, something each [tragic] character is doing and is going on doing” ( 2003 , p. 84; cf. Rudrum, 2013 , p. 185). Cavell shows how in the case of King Lear (where the King demands that his daughters reveal their hearts to him) this appears, characteristically, as the “isolation and avoidance of eyes” ( 2003 , p. 46). Lear “cannot bear being seen” (Cavell, 2003 , p. 68), and allows himself to be recognized by Gloucester only because, by that point, Gloucester is blind (Cavell, 2003 , pp. 50–51). In Frankenstein , Victor strives to avoid his creature’s sight from the moment it comes to life; as he confesses to Walton, he was “[u]nable to endure the aspect of the being [he] had created” (Shelley, 1999 , p. 85). The use of “aspect” here suggests that he was unable to look at his creature or could not endure his looks—or even that he could not bear the way the monster looked at him . When Mary Shelley invokes the same nightmare scene in her 1831 Introduction, she emphasizes this third and most disturbing possibility, when she describes the “hideous corpse” looking at his artist “with yellow, watery, but speculative eyes” (Shelley, 1999 , p. 357). What makes “speculative” so intolerable is the implication that the creature is silently weighing up his maker. As Leon Chai puts it, he “gazes at the protagonist with the same sort of reflective consciousness as the protagonist himself” ( 2006 , p. 170). Frankenstein, whose initial stance towards his anatomical specimen was that of full control and understanding, now finds himself at a loss about anything that might really matter to it, including, most crucially, its perception of him.

Victor’s terror of seeing and being seen by his creature drives him to repeat the first refusal again and again. A major, if unintended instance of this happens through the notes in which the creature reads, with terrible shame, about himself reduced to the bare ingredients he was made of. Footnote 6 Victor dismembers him once again through his writing, without any chance of being observed in return. Later, Frankenstein’s behavior at their meetings confirms that he “can’t see the creature as a subjectivity” (Chai, 2006 , p. 174). Having acquired the trained attention of the scientific observer, he seems unable to adjust his way of looking, even when looking at another living being. But, simultaneously, he also loses control over his experiment, now indefinitely extended, as life itself has become his laboratory. It is at this point that Frankenstein truly enters the realm that Hume had thought impossible to endure for very long: that of total skepticism. With the creature at large and untraceable, everything becomes uncertain and constant vigilance is required.

According to Hume’s first Conclusion, skepticism forces the philosopher to make an impossible choice “betwixt a false reason and none at all”, that is, between commonly held beliefs that are demonstrably unfounded, and the self-subverting movement of skeptical thought itself. “For my part, I know not what ought to be done in the present case”, Hume admits, “I can only observe what is commonly done; which is, that this difficulty is seldom or never thought of” (Hume, 2007 , 1:174). His solution, then, is ultimately a pragmatic one: skepticism can only be survived if the skeptic is able to rely once more on what is “commonly done”. As Parker explains, Hume’s “‘very dangerous dilemma’ is not resolved, but neglected; the chain of skeptical reasoning which, in the moment of philosophical intensity, seemed so disturbingly subversive, proves in practice to have little power to hold our attention or affect our behavior” ( 2003 , p. 143). The moment the philosopher is able to recognize this, the “corrosive and destabilizing skepticism of inquiry into the basis of things, gives way to a kind of affirmation of, or at least acquiescence in, the way things are” (Parker, 2003 , p. 143).

Stanley Cavell, commenting on Wittgenstein’s change of tack in his later philosophy, identifies the origins of skepticism in a wish to be separated from what he calls human “convention” or “shared forms of life”:

The gap between mind and world is closed, or the distortion between them straightened, in the apprehension and acceptance of particular human forms of life, human “convention”. This implies that the sense of gap originates in an attempt, or wish, to escape (to remain a “stranger” to, “alienated” from) those shared forms of life, to give up responsibility for their maintenance ( 1979 , p. 109).

This passage offers a very good description of Victor Frankenstein’s actions. Giving up responsibility for the maintenance of “shared forms of life” is exactly what he does, and not only with respect to his own creature, but with respect to many others who would depend on him. As we have seen, Hume had welcomed the ability to switch back and forth between philosophical and sociable modes or moods. Calling skepticism a malady that may “return upon us every moment”, he declared: “Carelessness and in-attention alone can afford us any remedy. For this reason I rely entirely upon them” (Hume, 2007 , 1:144). Even in the crisis report of his firstConclusion, he asserted that the moment he manages to forget about his metaphysics (as is just natural), he can return to society, play backgammon with his friends, and, later on,continue with a form of self-critical skepticism (Hume, 2007 , 1:175). Victor, in contrast, appears tragically inflexible. His intermittent spells of social re-integration become sparse, and the friends themselves who could bring about his recovery are eliminated one by one, until we are left with just him, the creature and the stranger Walton.

Writing about “the annihilation inherent in the skeptical problematic”, Cavell observes that “skepticism’s ‘doubt’ is motivated not by (not even where it is expressed as) a (misguided) intellectual scrupulousness but by a (displaced) denial, by a self-consuming disappointment that seeks world-consuming revenge” ( 2003 , pp. 5–6). It is for this reason that, for Cavell, the literary form embodying the skeptical problematic must be tragedy. Tragedy is also a genre that haunts Frankenstein , a story of total revenge, in which the creature fixes in death what Victor could not handle in life. Judith Pascoe has already noted the strong sense of theatricality in the novel, produced through scenes of gazing and watching, and “the frequent visual outlining of the creature, in window frames”, resembling “the proscenium of a stage” ( 2003 , p. 188). However, it may be argued that it is not theater in general, but specifically tragedy that is being evoked. The direct quotation of the monster’s grand speech at the “final and wonderful catastrophe” (Shelley, 1999 , p. 240) and Walton’s references to his own shifting reactions of horror and wonder, “curiosity and compassion” (Shelley, 1999 , p. 240) point in that direction. ‘Wonder’ [ to thaumaston ] and ‘catastrophe’ are both technical terms in Aristotle’s analysis of the tragic plot, and it is hardly a coincidence that both are used in the opening of Percy Bysshe Shelley’s review for the Athenaeum (Shelley, 1999 , p. 310). Tragic structure is also palpable in the agon of the two main characters, that is, in the long speeches they make, sometimes in the “amphitheater of mountains” (Shelley, 1999 , p. 216), as if they were talking in front of an imaginary tribunal. Admittedly, traces of tragedy such this one are buried deep in the texture of the novel. After all, Frankenstein is a work that both evokes Aeschylus’s drama in its subtitle and distances itself from it as the “Modern Prometheus”. Richard Van Oort expresses this ambivalence well when he writes that Frankenstein is a “tragedy, but of a distinctly ironic and Romantic type” ( 2009 , p. 134).

In Frankenstein , tragedy is analyzed into multiple narratives from the points of view of its various characters, each one of which destabilizes the others. Such a form might also be termed ‘skeptical’, as Kareem explains, since its valorizing of first-hand experience is “tempered by the understanding of such experience’s contingency” ( 2014 , p. 204). But this is not the only ‘skeptical’ aspect of Frankenstein ’s narrative technique. As we have already seen, Hume’s inquiries were based on the premise that knowledge should be grounded in first-hand experience. Discussing inferences about causes and effects in the Treatise , he pondered, for instance, how we come to know about events we had no chance of witnessing, such as the killing of Caesar on the ides of March (Hume, 2007 , 1:58). Can we be certain that it happened? And in that particular manner? According to Hume, the basis of our knowledge in such cases is that we can see “certain characters and letters” in books, that we remember how to connect to “certain ideas”, which, we assume, were present “either in the minds of such as were immediately present at that action, and receiv’d the ideas directly from its existence”, or “deriv’d from the testimony of others, and that again from another testimony, by a visible gradation, till we arrive at those who were eye-witnesses and spectators of the event” (Hume, 2007 , 1:58). First-hand experience, then, is supposed to secure our knowledge even of what had taken place in our absence; however, Hume is clearly apprehensive of the fragility of this chain of transmission and the role the imagination plays in creating it. Without “the authority either of the memory or senses”, he writes, “our whole reasoning wou’d be chimerical and without foundation”: “Every link of the chain wou’d in that case hang upon another; but there wou’d not be any thing fix’d to one end of it, capable of sustaining the whole; and consequently there wou’d be no belief nor evidence. And this actually is the case with all hypothetical arguments, or reasonings upon a supposition” (Hume, 2007 , 1:59).

This is exactly the kind of game played in Frankenstein , with its letters, confessions, and testimonies nestling within each other, constantly appealing to the immediacy of sense perception, but constantly deferring certainty. That is to say, the novel is “chimerical” in Hume’s precise sense of the term, realizing the worst nightmare of any philosopher straining for certainty, for the basis of its argument, the specter at its heart, is purely hypothetical. Percy Shelley called attention to this in his 1818 anonymous Preface, when he wrote that the impossible kernel of Frankenstein “affords a point of view to the imagination for the delineating of human passions more comprehensive and commanding than any which the ordinary relations of existing events can yield” (Shelley, 1999 , p. 47). However improbable its initial hypothesis, the novel offers a perspective on something that otherwise would be inaccessible to observation or conscious reflection. Self-conscious fiction, in this view, enables a species of thought experiment that Hume would not have consciously endorsed.

With this, we have arrived at the central issue that connects Hume’s inquiries to Frankenstein ’s tragic vision, but also to the point at which the two diverge. It is the question of obtaining experimental evidence, so important to Hume’s skeptic and so crucial to Shelley’s protagonist. As we have already seen, Hume in the Treatise proposed to use the experimental method on “moral subjects”. However, he quickly faced the problem of how to conduct such experiments and, as a result, toned down his ambitions considerably. The problem is that moral philosophy has a “peculiar disadvantage” when it comes to first-hand observation: it cannot make experiments in the more narrowly scientific sense, that is, “purposely, with premeditation”:

When I am at a loss to know the effects of one body upon another in any situation, I need only put them in that situation, and observe what results from it. But shou’d I endeavor to clear up after the same manner any doubt in moral philosophy, by placing myself in the same case with that which I consider,’tis evident this reflection and premeditation wou’d so disturb the operation of my natural principles, as must render it impossible to form any just conclusion from the phenomenon (Hume, 2007 , 1:6).

We can never have reliable first-hand knowledge of other people’s experiences—or indeed, of our own, as even self-observation necessarily alters what it is looking at. The mind, unlike the body, cannot be opened up for anatomical observation. Godwin in Political Justice put this with alarming simplicity: “Man, like every other machine the operations of which can be made the object of our senses, may, in a certain sense, be affirmed to consist of two parts, the external and the internal […] respecting the latter there is no species of evidence that can adequately inform us” ( 1946 , 2:348). Faced with this conundrum, Hume set out to “glean up [his] experiments in this science from a cautious observation of human life” ( 2007 , 1:6). In other words, he resolved to rely solely on what “the ordinary relations of existing events can yield,” to use Shelley’s phrase, and by stating this, he already foreshadowed his later rejection of total skepticism for the sake of “what is commonly done”. Godwin, in contrast, started to experiment with what he regarded a far more revealing, but also more intrusive type of examination: narrative fiction (Brewer, 2001 , p. 20). His novel Caleb Williams (1794)—referenced in the 1818 dedication of Frankenstein —was meant to conduct “the analysis of the private and internal operations of the mind,” as Godwin later explained, wielding his “metaphysical dissecting knife in tracing and laying bare the involutions of motive” (quoted in Carson, 2010 , p. 137).

In a sense, then, both Caleb Williams and Frankenstein attempt to do the impossible: opening up the mind for observation. This was also on the mind of Percy Shelley at the time; in a fragment written around Frankenstein ’s composition, he makes a wishful argument that seems to explore the central problematic of his wife’s novel:

If it were possible that a person should give a faithful history of his being, from the earliest epochs of his recollection, a picture would be presented as the world has never contemplated before. A mirror would be held up to all men in which they might behold their own recollections, and in dim perspective their shadowy hopes and fears—all that they dare not, or that daring and desiring, they could not expose to the open light of day (Shelley, 1995 , p. 83).

Frankenstein ’s most experimental section, the monster’s account of his earliest experiences, comes as close as possible to presenting such a “picture” of human consciousness (cf. Kareem, 2014 , pp. 211–212). As Monique Morgan has convincingly shown ( 2006 ), this part of the novel simulates how the mind works prior to the establishment of stable cognitive categories. More specifically, she and Kareem identify a Humean interest at the heart of the creature’s narrative, as we see him working inductively towards the understanding of the world. His unusual circumstances as an isolated “uncouth monster” replicate the position of the skeptic in his thought experiments, with one important difference: while the philosopher might try to artificially ‘ignore’ any previous certainties, the monster, by necessity, observes the world as an outsider, without any reliance on received knowledge or even, for a while, on any form of language. “It is with considerable difficulty that I remember the original aera of my being”, he admits, “all the events of that period appear confused and indistinct. A strange multiplicity of sensations seized me, and I saw, felt, heard, and smelt, at the same time; and it was, indeed, a long time before I learned to distinguish between the operations of my various senses” (Shelley, 1999 , p. 128). But the creature’s efforts to recall what this was like are surprisingly successful, and thus he manages to describe experiences—such as seeing the Moon for the first time – for which he is not supposed to possess, at the time, the adequate means of understanding (see Kareem, 2014 , pp. 212–215). In such moments, the hypothetical creature without a childhood but with a fully developed brain enables Shelley to present a mind stripped of all that Hume had regarded its necessary fictions, that is, a mind without any of the cognitive categories and associative links that structure and stabilize adult human experience.

Conclusion: the monster of skepticism

Through its intricate narrative construction, Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein enables reflection on the human mind by forcing it open through an impossible premise. But in doing so, the novel also speaks to a tragedy that follows from conducting such ‘anatomical’ inquiries. Wishing to ascertain what Life is once and for all, Victor Frankenstein creates his own representative Body, and endows it with life in a crucial experiment. However, retaining the anatomist’s gaze, he cannot acknowledge it as a living creature, and realizes only too late that the experiment led not to the understanding, but to the negation of life. To see why this is bound to happen, it is worth turning once more to Percy Shelley’s fragment about knowing the mind. The real and inescapable problem, for Shelley, is the gulf separating experience—in Shelley’s text, “presence,” “sensation,” or “perception”—from reflection:

If it were possible to be where we have been, vitally and indeed—if, at the moment of our presence there, we could define the results of our experience—if the passage from sensation to reflection—from a state of passive perception to voluntary contemplation, were not so dizzying and so tumultuous, this attempt would be less difficult (Shelley, 1995 , pp. 83–84).

The difficulty, then, lies in the delay, however small or innocuous, separating the moment of perception from that of interpretation. In Shelley’s terms, the “moment of our presence there” can never be the same as the moment of understanding “the results of our experience”. The two moments mutually exclude each other, which also means that there is something fundamentally unknowable in experience itself, and what we might claim as our knowledge of it is premised on that something’s denial or negation.

In conclusion, I would suggest that Frankenstein may be interpreted as a novel addressing what Percy Shelley called the “dizzying and tumultuous” ridge separating sensation from reflection, or experience from contemplation, and that it is not accidental that this mental landscape is so similar to his description of the reader’s experience of Frankenstein itself: “We climb Alp after Alp, until the horizon is seen blank, vacant, and limitless; and the head turns giddy, and the ground seems to fail under our feet” (Shelley, 1995 , p. 81). This is what Kareem calls “the skeptical sublime”: the sense of an abyss under our feet, when we had not even imagined the ground to be unsafe (Kareem, 2014 , p. 195; Noggle, 1996 , p. 612). The novel sets out to map the shifting threshold between sensation and reflection, or experience and understanding, which, in cruder terms, may be translated as the barrier separating the body that feels from the mind that understands what and how it feels (for instance, understands the working of the nerves or the functioning of the brain). Victor, whose anatomical expertise enabled his creation of a fully intelligible, working and living structure of a body, is unable to learn much about that body’s lived experience . Unlike his classical namesake, this “modern Prometheus” is sorely lacking in foresight: he only knows what is reported to him after the fact. It is remarkable how, once he has completed his creature, he tends to lag behind, as if the creature had already been to the places he just arrives at. He is bound to be late and to interpret the mere traces of his “Being” (to use Percy Shelley’s term), the nature of whose interactions with the world are clearly beyond his ken.

The indefinite aura of monstrosity surrounding the creature signals all that is perceivable but unintelligible about him, to Victor or anyone else. Cohen’s theory is again relevant: “The monstrous is a genus too large to be encapsulated in any conceptual system; the monster’s very existence is a rebuke to boundary and enclosure” ( 1996 , p. 7). Its experience is radically unknowable and “cannot be contained or controlled by conceptualization” (Baumgartner and Davies, 2008 , p. 1). The creature himself refers to this when he talks about his own “unformed” state, applying to himself Percy Shelley’s lines from the sonnet “Mutability”: “‘The path of my departure was free;’ and there was none to lament my annihilation” (Shelley, 1999 , p. 153). The sonnet laments the loss of every fleeting “mood or modulation” in experience: “be it joy or sorrow, / The path of its departure still is free”. For a revealing moment, then, the monster translates the poem’s “its” as “my”. Identifying himself with all that is mutable about experience, he becomes a self-conscious mutant.

In open contrast, Victor cites eight lines of the same sonnet (including the one adapted by his monster) in his account of climbing the Mont Blanc to meet his fate, while lamenting that neither human experience, nor linguistic meaning can be fixed: “we are moved by every wind that blows, and a chance word or scene that that word may convey to us” (Shelley, 1999 , p. 124). As this suggests, what Victor cannot understand in the monster is the same thing that he cannot understand in himself—and I think this is hardly due to any limitation of his understanding. In the 1831 edition Mary Shelley has even Walton declare, as if to underline the universality of the experience: “There is something at work in my soul, which I do not understand” (Shelley, 1999 , p. 317). The question is what to do once one is made aware of that something not understood. Or, to put it differently, what to do with the monster or daemon that—not unlike the daimon of Socrates—unfailingly demonstrates the limits of our knowledge about ourselves and others? According to Cavell, the truth or “moral” of skepticism is “that the human creature’s basis in the world as a whole, its relation to the world as such, is not that of knowing, anyway, not what we think of as knowing” (Cavell, 1979 , p. 241). Frankenstein’s tragic failure is his inability to leave room for not knowing . He cannot simply acknowledge the world, or his sense of himself, or the presence of others, as something existing but free to depart. As knowledge, for him, can only derive from what is fully understood, tested and verified, he becomes a creator dealing in finite things. But such creation is bound to remain unsatisfactory and his thirst for knowledge unsatisfied for the monstrosity of his creature constantly reminds him of all that he cannot know.

In 1811, Coleridge remarked about Shakespeare that “[t]he Poet is not only the man made to solve the riddle of the Universe, but he is also the man who feels where it is not solved” (Coleridge, 1987 , 1:326–327). Whether or not Shelley heard this particular aphorism—and we know that she attended some of Coleridge’s lectures with her father at the age of fourteen (Sawyer, 2007 , p. 17)—her novel may be regarded as an exercise in finding out what riddles can, and what riddles cannot be solved, and what happens if one is unable to tell the difference. This paper has argued that Frankenstein enacts the skeptical impasse of Hume’s Treatise in a tragic key, for what we merely glimpse in Hume as a threatening possibility, turns into real nightmare in the novel. Translating to the literal terms of gothic fiction what were, for Hume, mere figures of speech, Shelley conducts her thought experiment about what is at stake in the pursuit of knowledge. Similarly to Socrates’s daimon , the monster signals the limits of what is knowable, beyond which only acknowledgement can reach. True to its etymology, it warns ( monere ) that the life Victor wants to understand cannot be handled with the faculty of understanding—trying to do so and failing to change course leads to tragedy.

Data availability

Not applicable as no datasets were analyzed or generated.

Protagoras and Socrates are mentioned in Section XI of An Inquiry Concerning Human Understanding , as rare examples in ancient Greece of philosophers suffering from penal statutes against them (Hume, 1998 , p. 132).