- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Salem Witch Trials

By: History.com Editors

Updated: September 29, 2023 | Original: November 4, 2011

The infamous Salem witch trials began during the spring of 1692, after a group of young girls in Salem Village, Massachusetts, claimed to be possessed by the devil and accused several local women of witchcraft. As a wave of hysteria spread throughout colonial Massachusetts, a special court convened in Salem to hear the cases; the first convicted witch, Bridget Bishop, was hanged that June. Eighteen others followed Bishop to Salem’s Gallows Hill, while some 150 more men, women and children were accused over the next several months.

By September 1692, the hysteria had begun to abate and public opinion turned against the trials. Though the Massachusetts General Court later annulled guilty verdicts against accused witches and granted indemnities to their families, bitterness lingered in the community, and the painful legacy of the Salem witch trials would endure for centuries.

What Caused the Salem Witch Trials?: Context & Origins

Belief in the supernatural—and specifically in the devil’s practice of giving certain humans (witches) the power to harm others in return for their loyalty—had emerged in Europe as early as the 14th century, and was widespread in colonial New England . In addition, the harsh realities of life in the rural Puritan community of Salem Village (present-day Danvers, Massachusetts ) at the time included the after-effects of a British war with France in the American colonies in 1689, a recent smallpox epidemic, fears of attacks from neighboring Native American tribes and a longstanding rivalry with the more affluent community of Salem Town (present-day Salem).

Amid these simmering tensions, the Salem witch trials would be fueled by residents’ suspicions of and resentment toward their neighbors, as well as their fear of outsiders.

Did you know? In an effort to explain by scientific means the strange afflictions suffered by those "bewitched" Salem residents in 1692, a study published in Science magazine in 1976 cited the fungus ergot (found in rye, wheat and other cereals), which toxicologists say can cause symptoms such as delusions, vomiting and muscle spasms.

In January 1692, 9-year-old Elizabeth (Betty) Parris and 11-year-old Abigail Williams (the daughter and niece of Samuel Parris, minister of Salem Village) began having fits, including violent contortions and uncontrollable outbursts of screaming. After a local doctor, William Griggs, diagnosed bewitchment, other young girls in the community began to exhibit similar symptoms, including Ann Putnam Jr., Mercy Lewis, Elizabeth Hubbard, Mary Walcott and Mary Warren.

In late February, arrest warrants were issued for the Parris’ Caribbean slave, Tituba, along with two other women—the homeless beggar Sarah Good and the poor, elderly Sarah Osborn—whom the girls accused of bewitching them.

Salem Witch Trial Victims: How the Hysteria Spread

The three accused witches were brought before the magistrates Jonathan Corwin and John Hathorne and questioned, even as their accusers appeared in the courtroom in a grand display of spasms, contortions, screaming and writhing. Though Good and Osborn denied their guilt, Tituba confessed. Likely seeking to save herself from certain conviction by acting as an informer, she claimed there were other witches acting alongside her in service of the devil against the Puritans.

As hysteria spread through the community and beyond into the rest of Massachusetts, a number of others were accused, including Martha Corey and Rebecca Nurse—both regarded as upstanding members of church and community—and the four-year-old daughter of Sarah Good.

Like Tituba, several accused “witches” confessed and named still others, and the trials soon began to overwhelm the local justice system. In May 1692, the newly appointed governor of Massachusetts, William Phips, ordered the establishment of a special Court of Oyer (to hear) and Terminer (to decide) on witchcraft cases for Suffolk, Essex and Middlesex counties.

Presided over by judges including Hathorne, Samuel Sewall and William Stoughton, the court handed down its first conviction, against Bridget Bishop, on June 2; she was hanged eight days later on what would become known as Gallows Hill in Salem Town. Five more people were hanged that July; five in August and eight more in September. In addition, seven other accused witches died in jail, while the elderly Giles Corey (Martha’s husband) was pressed to death by stones after he refused to enter a plea at his arraignment.

Salem Witch Trials: Conclusion and Legacy

Though the respected minister Cotton Mather had warned of the dubious value of spectral evidence (or testimony about dreams and visions), his concerns went largely unheeded during the Salem witch trials. Increase Mather, president of Harvard College (and Cotton’s father) later joined his son in urging that the standards of evidence for witchcraft must be equal to those for any other crime, concluding that “It would better that ten suspected witches may escape than one innocent person be condemned.”

Amid waning public support for the trials, Governor Phips dissolved the Court of Oyer and Terminer in October and mandated that its successor disregard spectral evidence. Trials continued with dwindling intensity until early 1693, and by that May Phips had pardoned and released all those in prison on witchcraft charges.

In January 1697, the Massachusetts General Court declared a day of fasting for the tragedy of the Salem witch trials; the court later deemed the trials unlawful, and the leading justice Samuel Sewall publicly apologized for his role in the process. The damage to the community lingered, however, even after Massachusetts Colony passed legislation restoring the good names of the condemned and providing financial restitution to their heirs in 1711.

Indeed, the vivid and painful legacy of the Salem witch trials endured well into the 20th century, when Arthur Miller dramatized the events of 1692 in his play “The Crucible” (1953), using them as an allegory for the anti-Communist “witch hunts” led by Senator Joseph McCarthy in the 1950s. A memorial to the victims of the Salem witch trials was dedicated on August 5, 1992 by author and Holocaust survivor Elie Wiesel.

HISTORY Vault: Salem Witch Trials

Experts dissect the facts—and the enduring mysteries—surrounding the courtroom trials of suspected witches in Salem Village, Massachusetts in 1692.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

Salem Witch Trials — the Witchcraft Hysteria of 1692

February 1692–May 1693

The Salem Witch Trials are a series of well-known investigations, court proceedings, and prosecutions that took place in Salem, Massachusetts over the course of 1692 and 1693.

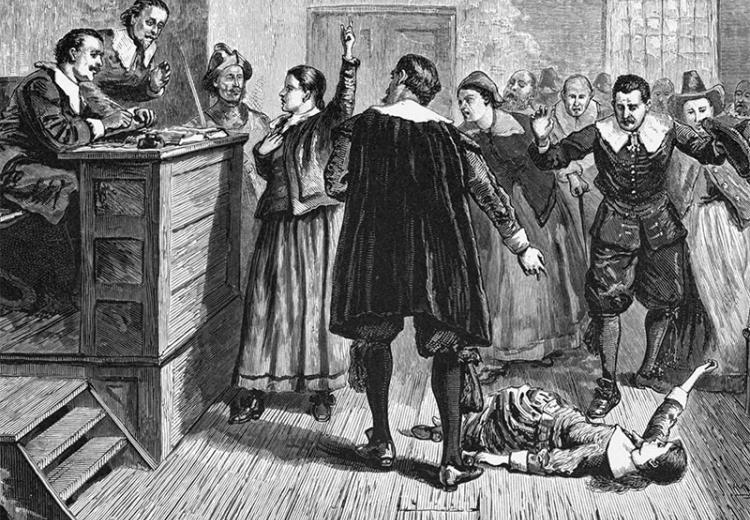

This illustration by Howard Pyle depicts one of the accusers pointing at the accused and saying, “There is a flock of yellow birds around her head.” It is an example of the spectral evidence that was permitted at the trials. Image Source: New York Public Library Digital Collections .

Salem Witch Trials Summary

The Salem Witch Trials took place in colonial Massachusetts in 1692 and 1693 when people living in and around the town of Salem, Massachusetts were accused of practicing witchcraft or dealing with the Devil. The accusations were initially made by two young girls in the early part of the year.

By May, William Phips had been named Governor of Massachusetts and a new charter had been implemented. Initially, Phips responded to the accusations by setting up a special court — the Court of Oyer and Terminer — to hear the cases and to determine the fate of the accused.

Unfortunately, the court was controversial because they allowed “spectral” evidence — visions of ghosts, demons, and the Devil — to be entered into the proceedings. It seemed to fuel the hysteria, which was likely elevated by King William’s War, which was going on in New England at the same time.

By the fall, 19 men and women had been convicted and hanged, and another was pressed to death . Another man died from having heavy stones placed on him. Somewhere between 150 and 200 were in prison or had spent time in prison.

Governor Phips ended the special court in October after accusations were made against well-respected members of the community. In January 1693, the trials resumed, but under the Supreme Court of Judicature. Spectral evidence was not allowed, and most of the accused were found innocent of the witchcraft charges and released.

A handful of the people accused of witchcraft were convicted, but Governor Phips intervened in May 1693 and agreed to release them as long as they paid a fine. By the time the proceedings ended, it was the largest outbreak of witchcraft in Colonial America .

Salem Witch Trials Facts

Facts about the accusers in the salem witch trials.

Two young girls, Elizabeth Paris and Abigail Williams started to act in a strange manner, which included making strange noises and hiding from their parents and other adults.

Elizabeth Paris, known as Betty, was 9 years old. Her father was the Reverend Samuel Paris.

Abigail Williams was 11 years old. Reverend Paris was her uncle.

More young girls in Salem Village started to show similar symptoms, including 12-year-old Anne Putnam and 17-year-old Elizabeth Hubbard.

Facts About the Accused in the Salem Witch Trials

The first people accused of witchcraft were Tituba, an enslaved woman, Sarah Good, and Sarah Osborne.

Dorothy Good was the youngest person to be accused of witchcraft. She was 4 years old.

Facts About the Role and Testimony of Tituba in the Salem Witch Trials

Tituba is believed to be an enslaved woman from Central America, possibly from Barbados.

She lived in the home of Reverend Paris and had been taken to Massachusetts by Paris in 1680.

Tituba confessed to using witchcraft.

She testified that four women, including Sarah Osborne and Sarah Good, along with a man, had told her to hurt the children.

Her testimony convinced the people of Salem Village that witchcraft was rampant in the town.

Facts About People Convicted and Executed During the Salem Witch Trials

The first person to be executed was Bridget Bishop.

Over the course of the Salem Witch Trials, 19 people were hanged at Proctor’s Ledge, near Gallows Hill.

Another one of the accused, Giles Corey, refused to enter a plea before the court and was ordered to be pressed to death. He was laid down on the ground and had heavy boards placed on top of him. Then heavy rocks were set on the boards until he was crushed by the weight.

The charges against all victims of the Salem Witch Trials were eventually cleared.

The Special Court

The Court of Oyer and Terminer was the special court ordered to oversee the trials, as ordered by Governor William Phips.

Salem Witch Trials Significance

The Salem Witch Trials were important because they showed how quickly accusations and hysteria could spread through Colonial America. At the time, the Witch Trials also threatened the authority and stability of the new charter and government of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, while King William’s War raged across New England and Acadia .

Salem Witch Trials APUSH — Notes and Study Guide

Use the following links and videos to study the Salem Witch Trials, King Willilam’s War, and the Massachusetts Bay Colony for the AP US History Exam. Also, be sure to look at our Guide to the AP US History Exam .

Salem Witch Trials APUSH Definition

The Salem Witch Trials were a series of hearings and prosecutions that occurred in colonial Massachusetts between 1692 and 1693. The trials were a dark chapter in American history, characterized by mass hysteria and accusations of witchcraft. Numerous individuals, predominantly women, were accused of practicing witchcraft, leading to the execution of 20 people — 13 women and 7 men. The trials were fueled by social, religious, and political factors, partially driven by King William’s War, resulting in tragic consequences for the victims and their families.

Salem Witch Trials Video for APUSH Notes

This video from the Daily Bellringer provides a detailed look at the Salem Witch Trials.

Salem Witch Trials APUSH Terms and Definitions

William Phips — William Phips was the governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony during the Salem Witch Trials. He played a significant role in bringing an end to the trials by dissolving the Court of Oyer and Terminer, which was responsible for the majority of the convictions. Phips was concerned about the growing public skepticism and criticism surrounding the trials, prompting him to take decisive action and promote a more rational approach to handling alleged witches. He was also worried about the public perception the trials had, during a time of war.

Court of Oyer and Terminer — The Court of Oyer and Terminer was a special court established in 1692 to handle the cases of alleged witches in Salem and surrounding areas. The court was led by several judges, including William Stoughton, and it operated under a unique legal process that allowed spectral evidence, or testimonies of dreams and visions, to be admitted as valid evidence. This, along with other factors, contributed to a biased and unjust environment during the trials.

William Stoughton — William Stoughton was a prominent judge and the Lieutenant Governor of Massachusetts. He presided over the Court of Oyer and Terminer during the Salem Witch Trials. He played a pivotal role in the harsh convictions and sentencing of numerous accused individuals. His unwavering support for spectral evidence and his lack of leniency exacerbated the severity of the trials’ outcomes. After Phips dismissed the cases, Stoughton worked to have him removed as Governor.

Samuel Paris — Reverend Samuel Paris was the minister of Salem Village and one of the central figures in the initial events that sparked the witch trials. He was the father of Elizabeth Paris and the uncle of Abigail Williams, two young girls who experienced mysterious fits and claimed to be afflicted by witchcraft. His role as a religious authority and his support for the accusations fueled the hysteria, contributing to the escalation of the trials.

Elizabeth Paris — Elizabeth Paris was the nine-year-old daughter of Samuel Paris and one of the first accusers in the Salem Witch Trials. With her cousin Abigail Williams, she exhibited peculiar behaviors, including seizures and strange utterances, which were attributed to witchcraft. Their accusations against various individuals, especially Tituba, were instrumental in initiating the investigations and subsequent arrests.

Abigail Williams — Abigail Williams, the eleven-year-old cousin of Elizabeth Paris, was another crucial accuser during the Salem Witch Trials. Like her cousin, she displayed symptoms of bewitchment and was among the first to accuse others, leading to a chain reaction of allegations.

Anne Putnam — Anne Putnam was a teenage girl from Salem Village who actively participated in the trials as an accuser. She made numerous accusations against various individuals, contributing to the mounting hysteria. Her motivations for involvement remain a topic of historical debate, with some suggesting that personal grievances and religious fervor influenced her actions.

Tituba — Tituba was an enslaved woman from the Caribbean who worked in the household of Reverend Samuel Paris. She became one of the first individuals accused of practicing witchcraft after Elizabeth and Abigail accused her of bewitching them. Tituba’s origin and cultural differences contributed to her status as an outsider in Salem, making her an easy target for accusations. Under pressure, she confessed to being a witch and provided testimonies that increased the intensity of the trials.

Bridget Bishop — Bridget Bishop was the first person to be tried and executed during the Salem Witch Trials. She was known for her unconventional lifestyle and had been accused of witchcraft once before.

John Proctor — John Proctor was a respected farmer in Salem Village and one of the central figures in Arthur Miller’s play “The Crucible,” which was based on the events of the witch trials. Proctor was accused of witchcraft after he spoke out against the proceedings, expressing skepticism about the legitimacy of the trials. His refusal to falsely confess and his unwavering integrity ultimately led to his tragic execution.

Giles Corey — Giles Corey was an elderly farmer who became entangled in the witch trials when his wife, Martha Corey, was accused of witchcraft. In a notable act of protest against the unjust proceedings, Corey refused to enter a plea in court, leading to a brutal form of punishment known as pressing. Corey died during the punishment.

King William’s War — King William’s War was a conflict between England and France that occurred from 1689 to 1697, overlapping with the time of the Salem Witch Trials. The war was part of a larger conflict known as the Nine Years’ War or the War of the Grand Alliance. Its impact on the region, including heightened tensions and security concerns, likely contributed to the climate of fear and paranoia in Salem, potentially influencing the outbreak of the witch trials.

Salem Witch Trials — Primary and Secondary Sources

- The Witchcraft Delusion of 1692 by Thomas Hutchinson , William Frederick Poole, and Richard Frothingham

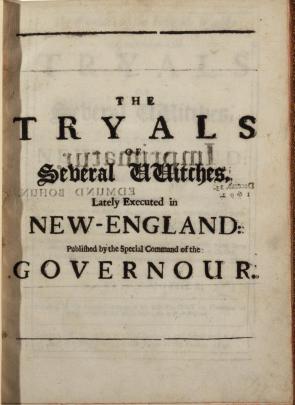

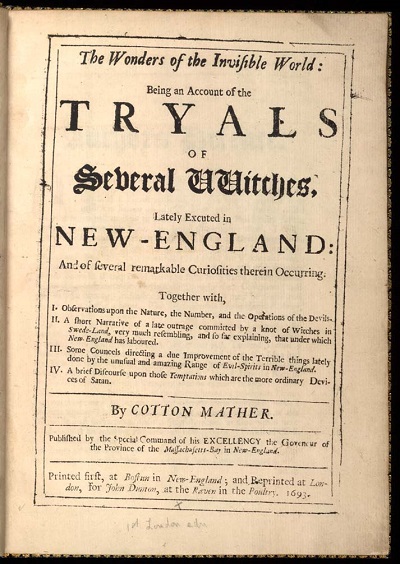

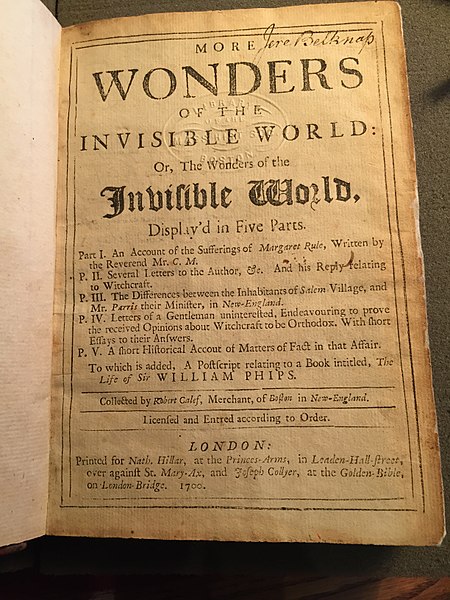

- The Wonders of the Invisible World : Being an Account of the Tryals of Several Witches Lately Executed in New-England by Cotton Mather

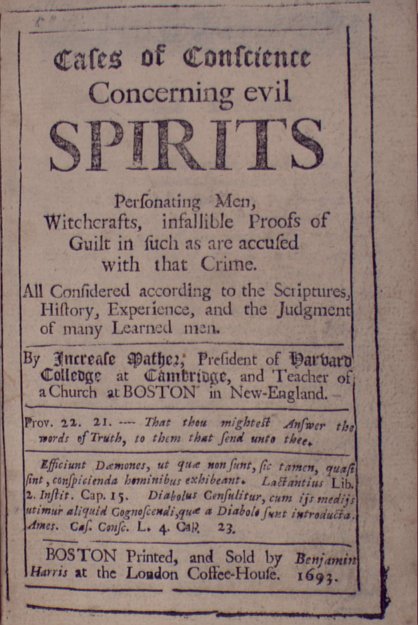

- Cases of Conscience Concerning Evil Spirits Personating Men, Witchcrafts, Infallible Proofs of Guilt in Such as are Accused with the Crime by Increase Mather

- Written by Randal Rust

A Brief History of the Salem Witch Trials

One town’s strange journey from paranoia to pardon

Jess Blumberg

:focal(1280x914:1281x915)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/40/e6/40e69d4a-6016-4815-ba7a-01fce1bb2e5d/examination_of_a_witch_-_tompkins_matteson.jpeg)

The Salem witch trials occurred in colonial Massachusetts between early 1692 and mid-1693. More than 200 people were accused of practicing witchcraft—the devil’s magic —and 20 were executed.

In 1711, colonial authorities pardoned some of the accused and compensated their families. But it was only in July 2022 that Elizabeth Johnson Jr. , the last convicted Salem “witch” whose name had yet to be cleared , was officially exonerated .

Since the 17th century, the story of the trials has become synonymous with paranoia and injustice . Fueled by xenophobia , religious extremism and long-brewing social tensions , the witch hunt continues to beguile the popular imagination more than 300 years later.

Tensions in Salem

In the medieval and early modern eras, many religions, including Christianity , taught that the devil could give people known as witches the power to harm others in return for their loyalty. A “ witchcraft craze ” rippled through Europe from the 1300s to the end of the 1600s. Tens of thousands of supposed witches —mostly women—were executed. Though the Salem trials took place just as the European craze was winding down, local circumstances explain their onset.

In 1689, English monarchs William and Mary started a war with France in the American colonies. Known as King William’s War to colonists, the conflict ravaged regions of upstate New York, Nova Scotia and Quebec, sending refugees into the county of Essex—and, specifically, Salem Village—in the Massachusetts Bay Colony. (Salem Village is present-day Danvers, Massachusetts; colonial Salem Town became what’s now Salem.)

The displaced people placed a strain on Salem’s resources, aggravating the existing rivalry between families with ties to the wealth of the port of Salem and those who still depended on agriculture. Controversy also brewed over the Reverend Samuel Parris , who became Salem Village’s first ordained minister in 1689 and quickly gained a reputation for his rigid ways and greedy nature. The Puritan villagers believed all the quarreling was the work of the devil.

In January 1692, Parris’ daughter Elizabeth (or Betty), age 9, and niece Abigail Williams, age 11, started having “fits.” They screamed, threw things, uttered peculiar sounds and contorted themselves into strange positions. A local doctor blamed the supernatural . Another girl, 12-year-old Ann Putnam Jr., experienced similar episodes. On February 29, under pressure from magistrates Jonathan Corwin and John Hathorne, colonial officials who tried local cases, the girls blamed three women for afflicting them: Tituba , a Caribbean woman enslaved by the Parris family; Sarah Good , a homeless beggar; and Sarah Osborne , an elderly impoverished woman.

The witch hunt begins

All three women were brought before the local magistrates and interrogated for several days, starting on March 1, 1692. Osborne claimed innocence, as did Good. But Tituba confessed , “The devil came to me and bid me serve him.” She described elaborate images of black dogs, red cats, yellow birds and a “tall man with white hair” who wanted her to sign his book. She admitted that she’d signed the book and claimed there were several other witches looking to destroy the Puritans.

With the seeds of paranoia planted, a stream of accusations followed over the next few months. Charges against Martha Corey , a loyal member of the church in Salem Village, greatly concerned the community; if she could be a witch, then anyone could. Magistrates even questioned Good’s 4-year-old daughter, Dorothy , whose timid answers were construed as a confession. The questioning got more serious in April, when the colony’s deputy governor, Thomas Danforth, and his assistants attended the hearings. Dozens of people from Salem and other Massachusetts villages were brought in for questioning .

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/55/25/552587cf-d7e9-49e1-86b6-91ac0b725486/2560px-martha_corey_and_her_persecutors.png)

On May 27, 1692, Governor William Phips ordered the establishment of a Special Court of Oyer (to hear) and Terminer (to decide) for Suffolk, Essex and Middlesex counties. The first accused witch brought in front of the special court was Bridget Bishop , an older woman known for her gossipy habits and promiscuity. When asked if she committed witchcraft, Bishop responded , “I am as innocent as the child unborn.” The defense must not have been convincing, because she was found guilty and, on June 10, became the first person hanged on what was later called Gallows Hill .

Just a few days after the court was established, respected minister Cotton Mather wrote a letter imploring the court not to allow spectral evidence —testimony about dreams and visions. The court largely ignored this request, sentencing the hangings of five people in July, five more in August and eight in September. On October 3, following in his son Cotton’s footsteps, Increase Mather , then-president of Harvard, denounced the use of spectral evidence: “It were better that ten suspected witches should escape than one innocent person be condemned.”

Phips, in response to these pleas and his own wife’s questioning as a suspected witch, prohibited further arrests and released many accused witches. He dissolved the Court of Oyer and Terminer on October 29, replacing it with a Superior Court of Judicature , which disallowed spectral evidence and condemned just 3 out of 56 defendants.

By May 1693, Phips had pardoned all those imprisoned on witchcraft charges. But the damage was already done. Nineteen men and women had been hanged on Gallows Hill. Giles Corey , Martha’s 71-year-old husband, was pressed to death in September 1692 with heavy stones after refusing to submit himself to a trial. At least five of the accused died in jail. Even animals fell victim to the mass hysteria, with colonists in Andover and Salem Village killing two dogs believed to be linked to the devil.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/2d/56/2d5624dd-cbd4-4cf1-8406-fe59f1d12c22/witchcraft_at_salem_village.jpeg)

Restoring good names

In the years following the trials and executions, some involved, like judge Samuel Sewall and accuser Ann Putnam , publicly confessed error and guilt. On January 14, 1697, Massachusetts’ General Court ordered a day of fasting and soul-searching over the tragedy of Salem. In 1702, the court declared the trials unlawful. And in 1711, the colony passed a bill restoring the rights and good names of many of the accused, as well as granting a total of £600 in restitution to their heirs. But it wasn’t until 1957—more than 250 years later—that Massachusetts formally apologized for the events of 1692. Johnson, the accused woman exonerated in July 2022, was left out of the 1957 resolution for reasons unknown but received an official pardon after a successful lobbying campaign by a class of eighth-grade civics students.

In the 20th century, artists and scientists alike continued to be fascinated by the Salem witch trials. Playwright Arthur Miller resurrected the tale with his 1953 play The Crucible , using the trials as an allegory for the anti-communist McCarthyism then sweeping the country. Scholars offered up competing explanations for the strange behavior that occurred in Salem, with scientists seeking a medical cause for the accusers’ afflictions and historians more often grounding their theories in the community’s tense sociopolitical environment .

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/87/50/8750d715-a657-481c-a599-939e16d4499d/gettyimages-1176018717.jpg)

An early hypothesis now viewed as “fringe, especially in historical circles ,” according to Vox , posited that the accusers suffered from ergotism , a condition caused by eating foods contaminated with the fungus ergot. Symptoms include muscle spasms, vomiting, delusions and hallucinations. Other theories emphasize a “combination of church politics, family feuds and hysterical children, all of which unfolded in a vacuum of political authority,” as Encyclopedia Britannica notes. Ultimately, the causes of the witch hunt remain subject to much debate .

In August 1992, to mark the 300th anniversary of the trials, Nobel Laureate Elie Wiesel dedicated the Witch Trials Memorial in Salem. Also in Salem, the Peabody Essex Museum , which houses the original court documents , mounted an exhibition reckoning with and reclaiming the tragedy in late 2021 and early 2022. Finally, the town’s most-visited attraction, the Salem Witch Museum , attests to the public’s enduring enthrallment with the 17th-century hysteria.

Editor’s Note, October 24, 2022: This article has been updated to reflect the latest research on the Salem witch trials.

Get the latest History stories in your inbox?

Click to visit our Privacy Statement .

Jess Blumberg | READ MORE

The Salem Witch Trials of 1692

The salem witch trials are a defining example of intolerance and injustice in american history..

This extraordinary series of events that began in 1692 led to the deaths of 25 innocent women, men and children. The crisis in Salem, Massachusetts took place partly because the community lived under an ominous cloud of suspicion. A remarkable set of conflicts and tensions converged, sparking fear and setting the stage for the most widespread and lethal outbreak of witchcraft accusations in North America.

Centuries after this storied crisis, the personal tragedies and grievous wrongs of the witch trials continue to provoke reflection, reckoning and a search for meaning. Today, the city of Salem attracts more than 1 million tourists per year, many of whom are seeking to learn more about these events. The Peabody Essex Museum (PEM) holds one of the world’s most important collections of objects and architecture related to the Salem Witch Trials. From 1980 to 2023, PEM’s Phillips Library was the temporary repository of the state’s Supreme Judicial Court collection of witch trial documents. These legal records, which were returned to the Judicial Archives following the expansion and modernization of the Massachusetts State Archives facility, are available to researchers around the world on our website thanks to a comprehensive digitization project. Through exhibitions, research, publishing and public programming, PEM is committed to telling the story of the Salem Witch Trials in ways that honor the victims and amplify the teachings of wrongful persecution that remain relevant to today.

The Salem Witch Trials Walk

This self-guided audio tour takes you inside the galleries and outside the museum to learn more about the infamous events of 1692. PEM curators and experts share a behind-the-scenes perspective of some of the most compelling stories in Salem in this one-hour tour. Included with museum admission.

History and Origins of the Salem Witch Trials

English colonial settlers arrived in 1626 at Naumkeag, a traditional Native American fishing site, to establish a Massachusetts Bay Colony outpost. Most were Puritans who sought to “purify” the Church of England from Roman Catholic religious practices and build a utopian society. The settlers renamed the place Salem, after Jerusalem, meaning “city of peace.”

Over successive decades, waves of colonists arrived, changing the power dynamics in governance, land ownership and religion. By the 1670s, tensions between rural Salem Village (now Danvers) and the prosperous Salem Town flared. Arguments multiplied when Salem Village formed its own church and appointed a controversial minister. Changes to the colony’s charter and leadership, skirmishes with French colonists and their Indigenous allies, a smallpox epidemic and extreme weather all heightened concerns.

In January 1692, several young girls in Salem Village reported that unseen agents or forces were afflicting them. The minister suspected witchcraft. In the 17th century, a witch was understood as a person who agreed to serve the devil in opposition to the Christian church. On February 29, four men and four girls traveled to Salem Town to make complaints against three women. The next day, interrogations began.

Notable Figures of the Witch Trials: The Accused and the Accusers

Bridget bishop.

Historical research reveals a picture of Bridget Bishop (1632–1692) as a witty and independent, though quarrelsome, resident of Salem. Widowed twice, she was married to a sawyer (or woodcutter) named Edward Bishop. Attorney General Thomas Newton decided to put Bridget Bishop on trial first, perhaps looking for a strong case to set the tone for subsequent hearings. Accused and acquitted of witchcraft 12 years earlier, she may have been an easy target by association. Multiple accusers claimed Bishop’s specter was responsible for damages and afflictions. Their testimonies were the result of longstanding suspicions or misattributed gossip about Sarah Bishop, a different person entirely. No witchcraft allegedly perpetrated by Bridget Bishop was ever proven by the required testimony of two witnesses. Instead, the court relied on the spectral evidence claimed by the accusers, the only ones who could “see” the invisible world of demons. Tragically, this injustice against Bishop set the pattern for the remainder of the trials.

What little is known about Tituba is through her involvement in the witch trials. Documents refer to her as “Indian,” but it is likely that she was from an Indigenous Arawak community in present-day Venezuela. Reverend Samuel Parris enslaved Tituba and brought her to Boston and then Salem Village when he returned North from Barbados in 1680. Parris’s daughter Betty and her cousin Abigail Williams identified Tituba as the perpetrator of their January and February afflictions, the first accusations of 1692. Tituba’s testimony on March 1–2 confirmed for locals that a witchcraft conspiracy existed. In addition to confessing — undoubtedly under pressure — she accused Sarah Osburn and Sarah Good and said there were seven more witches, quickly widening the scope of the crisis. The court left Tituba to languish in prison until May 1693, when a grand jury rejected the charges brought against her. Shortly after, an enslaver, whose name is not known, paid her jail debts and released her to their ownership. The remainder of her life is a mystery.

George Jacobs Sr.

George Jacobs Sr. (1620–1692) was born in London and was living in the Salem colony by 1649. As a country farmer suffering from arthritis, he used two canes to walk. He did not attend church regularly and had a reputation for a violent temper and defiant spirit. His reputation and disability — along with his son’s friendship with the Porter family, enemies of the powerful Putnam family — made Jacobs an easy target for early accusers. His granddaughter Margaret, who confessed to the charge of witchcraft, accused him. Then, Mercy Lewis, a servant of Thomas Putnam, testified that Jacobs “did torture me and beat me with a stick which he had in his hand … coming sometimes with two sticks in his hands to afflict me.” His son and wife also contributed. In August, the court sentenced him to death.

The Towne Sisters

Rebecca Nurse (about 1621–1692), Mary Esty (about 1634–1692) and Sarah Cloyce (about 1641–1703) were sisters from the Towne family of Topsfield, Massachusetts. All three women were married, with large extended families. Elderly Rebecca, a respected member of the church, was nearly deaf, which may have prevented her from defending herself fully in court. Dozens petitioned the court on her behalf.

At first, the jury returned a verdict of not guilty, but the judges asked them to reconsider. In a dramatic reversal, Rebecca was found guilty, condemned and hanged. Mary put before the court two of the most eloquent, heartfelt petitions of the entire episode. The surviving documents call for fair trials, expose the flaws of the existing court and propose methods of getting to the truth behind the accusations. But they did not help her avoid execution. It is unknown how Sarah escaped the fate of her sisters. After months in prison, she was cleared. Sarah, her husband, and many members of the extended Towne family were among the first English colonists to settle in Framingham.

The Corey Family

Giles and Martha Corey both faced accusations by multiple people. In March, Giles testified against Martha claiming that she bewitched him and his farm animals. In September, when Giles refused to participate in his own trial, the court ordered him to be pressed under stones in order to extract a plea. He remained silent and died under the weight in the only death by pressing in Massachusetts history. Martha and seven other victims were hanged days later.

The Putnam Family

The Putnams, a well-established Puritan family, owned much of the land in Salem Village and supported the Reverend Samuel Parris. They were deeply involved in the search for witches, accusing and testifying against many members of their community and extended family.

Jonathan Corwin

Jonathan Corwin (1640–1718) was a merchant and political figure who held various positions, including serving as magistrate during the 1692 pretrial examinations. Corwin lived in the house now known as the Witch House on the corner of Essex and Summer streets. Corwin remained on the bench until October 1692, when the governor officially disbanded the special court of oyer and terminer (meaning “to hear and determine”) that was convened for the witch trials. We do not know much about how Corwin felt about the trials because he spoke little during the examinations and never made any public statements. However, he never apologized for his role in the trials. His brother-in-law John Hathorne served as magistrate, and one of Corwin’s children was listed as “afflicted” in Tituba’s examination in March. His mother-in-law Margaret Thacher was accused of witchcraft, but the charges against her were ignored and no arrest warrant was issued.

Samuel Sewall

Born in England, Samuel Sewall (1652–1730) and his family emigrated to Newbury, Massachusetts, in the 1660s. A Harvard graduate, Sewall initially trained to become a clergyman. He later pursued a career in business, politics and public service after marrying the daughter of a wealthy Boston merchant. His wife’s first cousin was the Reverend Samuel Parris, and he derived significant income from real estate holdings. Sewall was one of nine judges appointed by Governor Sir William Phips to serve on the court in Salem to “hear and determine” accusations of witchcraft. These judges were respected, educated and affluent members of the community, but none had formal legal training.

While fulfilling his role as judge, Sewall took part in proceedings that sent 19 innocent people to their deaths. In the aftermath of the trials, Sewall’s troubled conscience led to a change of heart, and in January 1697, he made a public confession of guilt, remorse and repentance for the part he played in the trials and apologized for his role in the proceedings. For the rest of his life, Sewall regularly observed a day of fasting as evidence of ongoing contrition. Sewall continued his judicial career for many years, culminating in 1718 with his appointment as Chief Justice of the Superior Court of Judicature. Sewall is also remembered for publishing the first anti-slavery tract in America in 1700.

Frequently Asked Questions about the Salem Witch Trials

The Salem Witch Trials are a defining example of intolerance and injustice in American history. Centuries later, the witch trials continue to capture the public imagination.

Explore the FAQs below to learn more about the tragic events of 1692.

What are the Salem Witch Trials?

This series of trials, prosecutions and executions of innocent people accused of practicing witchcraft took place in Colonial Massachusetts. Salem’s witch trials are a defining example of intolerance and injustice in American history.

When were the Salem Witch Trials?

The Salem Witch Trials took place from the summer of 1692 through the fall of 1693.

What role did gender play in the Salem Witch Trials?

Most of those accused were women, just as in other witchcraft accusations around the world. The Malleus Maleficarum ( The Hammer of Witches ), an influential witchcraft and demonology manual from 1494, states: “When a woman thinks alone, she thinks evil.” The typical English settler in New England regarded the devil as real and witches as his accomplices in bringing unexpected misfortune. Women represented three quarters of those prosecuted of witchcraft in New England, with accusers most often pointing the finger at middle-aged and older women. But popular belief held that anyone could be a witch, even friends and family. In difficult times, long-held suspicions erupted into accusations and trials.

Were there actual witches in Salem?

There were no witches in 17th-century Salem. In the 17th century, a witch was understood as a person who agreed to serve the devil in opposition to the Christian church. In 1692, several young girls in Salem Village reported that unseen agents or forces afflicted them, accusing their neighbors of causing these afflictions. The accused and the murdered were innocent.

If there were no witches in Salem in 1692, then why does Salem today claim a sizable community of people who identify as witches?

The word “witch” has been reclaimed from its historical use as a tool to silence and control women. Today, the term encompasses a broad spectrum of contemporary identities and professions: tarot readers, spiritual healers, Wiccan High Priestesses, Neo-Pagans, occultists, mystics, herbalists and activists. Perhaps it is because of the lessons learned from 1692 and Salem’s attempts to confront its past that the city is a popular place for those who identify as witches.

Who died in the Salem Witch Trials?

The extraordinary series of events in 1692–1693 led to the deaths of 25 innocent women, men and children.

How did the victims die?

Most were hanged. One man, Giles Corey, was pressed to death under large stones. Some of the victims died in prison.

Where were the accused jailed?

Many of those arrested for allegedly practicing witchcraft were imprisoned in Salem’s infamous jail. Built in 1684 as part of Essex County’s judicial system, it was located on Prison Lane, known today as St. Peter’s Street at the juncture of Federal Street. Described as a two-story, twenty-foot-square wooden building, it was designed for maximum security. With iron bars on the windows and shackles to chain victims to the wall, escape was improbable. The jail’s dirt floor, lack of air circulation and inadequate sanitary facilities made for brutal conditions throughout the seasons.

Where were they hanged?

Proctor’s Ledge, a rocky outcropping at the base of Gallows Hill in Salem, was the site where 19 victims were hanged. An official dedication of a memorial at this site happened in 2016. Gallows Hill is also now the name of a residential neighborhood.

Where did witch hunts happen prior to Salem?

The Salem witchcraft crisis had European origins. During the most active period of witch hunts from 1400 to 1775, religious upheaval, warfare, political tensions and economic dislocation led to waves of persecutions and scapegoating in Europe and its colonies. Roughly 100,000 people were tried for witchcraft and 50,000 were executed. It was believed that witches threatened Christian society by drawing upon Satan’s terrible power to unleash sickness, misery and death across the land.

What was 17th-century Salem like?

English colonial settlers arrived in 1626 at Naumkeag, a Native American fishing site, to establish a Massachusetts Bay Colony outpost. Most were Puritans who sought to “purify” the Church of England from Roman Catholic religious practices. In the late 17th century, Salem’s geographic boundaries covered an area of roughly 70 square miles, including parts of several nearby communities. The area was both urban and rural and included Salem Village (now Danvers), which was home to several farming families.

Why is The Witch City also called The City of Peace?

The Puritans wanted to build a utopian society and chose the name Salem after Jerusalem, meaning “city of peace.”

What was the relationship between the British and the colonists like in 1692?

The 1692 crisis occurred about 85 years before the Declaration of Independence was signed. The colonists were just emerging in the spring of 1692 from a period of several years of uncertainty with the British. After rebelling against British laws, their charter had been revoked. Without political authority, the local government was chaotic and the colonists feared punishment from the crown.

Was the 1692 crisis caused by food poisoning?

Many inventive theories circulate about the Salem Witch Trials, but the crisis was not caused by poisoning from rotten bread, property disputes or an outbreak of encephalitis. The panic grew from a society threatened by nearby fighting between the British and the French over occupying Maine, as well as a malfunctioning political and judicial system in a setting rife with religious conflict and intolerance.

What was the real cause of the Salem Witch Trials?

Ongoing conflict with French colonists and their Indigenous allies to the north of Massachusetts contributed to the unease in Salem. Along with social unrest, a smallpox epidemic and the driest summers and coldest winters on record caused widespread misery. By the 1670s, tensions between rural Salem Village (now Danvers) and the prosperous Salem Town flared. Contentions multiplied when Salem Village formed its own church and appointed a controversial minister. These events and conditions laid the foundation for the most lethal and widespread outbreak of witchcraft accusations in North America. Then, in 1691, England’s King William and Queen Mary issued a charter for the colony, giving more control to the crown through appointed officials and threatening Massachusetts’ status as a Puritan colony.

How did the crisis begin?

The first claims of bewitchment occurred at the Reverend Samuel Parris’s parsonage in Salem Village, known today as Danvers, in January 1692. From February to June, the afflictions and accusations spread rapidly across much of the colony. Local constables detained suspects for examination at the behest of magistrates, who then publicly questioned the accused to determine cause for trial.

What if you were accused and survived?

Despite many courageous pleas, all of those convicted of witchcraft found their reputations and relationships shattered by the experience. Some of the victims suffered a court-sanctioned seizure of their belongings, resulting in a loss of their identity and standing in the community. Ultimately, the court’s verdicts and sentences led to the unjust execution of 19 of the more than 170 individuals accused.

How did the crisis finally end?

Few local people were willing to question the witch hunt initially because it could put them under suspicion. Opposition grew over the summer of 1692 as it became increasingly clear that the court was failing to protect innocent lives. Later that fall, several leading ministers of the colony wrote books criticizing the trials, despite a public defense by Reverend Cotton Mather and a publication ban by Governor Sir William Phips. The opposition became more vocal over time and, finally, in 1697, the Massachusetts government ordered a day of public fasting and prayers for forgiveness of the colony’s sins, including the witch trials. Belief in witches declined gradually in the 18th century as the ideas of the scientific revolution spread. The Salem trials had proved it was impossible to convict a witch without endangering innocent lives as well. Following the trials and executions, many involved, like judge Samuel Sewall, publicly confessed error and remorse. Massachusetts issued its first pardons for victims of the witch trials in 1703. Several later rounds of exonerations, occurring over hundreds of years, attempted to complete this process for all victims. Efforts to serve justice continue even today: Massachusetts exonerated Elizabeth Johnson Jr. of Andover through legislative action in 2022.

Have the lessons of the Salem Witch Trials remained an influence in Salem?

Shame over the witch trials ran so deep that it took 300 years before a memorial to the victims was constructed in Salem. Today, the community fully acknowledges the place the witch trials hold in American history and local groups strive to make amends. The volunteer community organization Voices Against Injustice (VAI) maintains the Salem Witch Trials Memorial and provides programming that connects the events of 1692 to today. The organization also presents the annual Salem Award for Human Rights and Social Justice, which recognizes and celebrates individuals and organizations that confront fear and injustice with courage to honor the legacy of those who did the same in 1692.

Are the accused memorialized somewhere in Salem?

Dedicated in August 1992, the Salem Witch Trials Memorial is located on Liberty Street, Salem. It was designed by Maggie Smith and James Cutler to commemorate the 300th anniversary of the trials. The memorial is maintained by the volunteer community organization Voices Against Injustice.

Are there any descendants living today?

Yes – descendents of the Salem Witch Trials victims and accusers live all over the world, and many travel to Salem to trace their ancestral roots.

What does the term “witch hunt” mean?

The term “witch hunt” has become synonymous with intolerance, injustice and the rush to judgment. The phrase has been used by politicians across the spectrum to tarnish the opposition, from rhetoric on the smallpox vaccine controversies of the 1720s to the American Revolution, abolition of slavery and fears of communist subversion.

Do witch hunts still happen?

Witch hunts occurred in Europe hundreds of years before the Salem Witch Trials. Belief in witchcraft in Early Modern England was widespread, but not universal. By the late 17th century, several English scholars and religious figures rejected the idea that witchcraft existed, a concept debated in the American colonies. The persecution of women and those perceived to be “other” still happens around the world today.

What does Salem’s month-long celebration of Halloween have to do with the Salem Witch Trials?

Known as the Witch City, Salem welcomes around 1 million tourists every year. The witch insignia can be found on the masthead of The Salem News, on Salem police cars and on the uniforms of the local high school football team. In 1982, the city of Salem planned the first Salem Haunted Happenings Festival during Halloween weekend. The festival was an effort to provide family-friendly events for guests who were interested in visiting the Witch City. Following the first festival’s success with about 50,000 guests in attendance, the annual event has continued to grow each season, drawing history buffs and Halloween enthusiasts from all over the world. Salem Haunted Happenings is a festive celebration of Halloween and fall in New England that runs annually from October 1–31. Events include a Grand Parade, the Haunted Biz Baz Street Fair, Family Film Nights, costume balls, ghost tours, haunted houses, live music and chilling theatrical presentations.

How have the Salem Witch Trials inspired art throughout American history?

Puritanical Massachusetts and its rush to judgment are the backdrop for the 1850 novel The Scarlet Letter , written by Nathanial Hawthorne, descendent of witch trial judge John Hathorne. The Salem Witch Trials inspired Arthur Miller’s 1953 play The Crucible , which is a partially fictionalized story of the trials. It was an allegory for the United States government’s persecution of people accused of being communists throughout the 1940s and 1950s. The events have also inspired countless TV shows, films and even musical genres. Recently, PEM worked with contemporary artists who have ancestral ties to the tragic events in Salem. The resulting exhibition, The Salem Witch Trials: Reckoning and Reclaiming , included the work of contemporary artist Frances Denny, who has photographed a broad array of people who identify as witches today, as well as the work of British fashion designer Alexander McQueen, who was a descendent of one of the accused in Salem.

Related exhibitions

The Salem Witch Trials 1692

Opens July 6, 2024

On This Ground: Being and Belonging in America

Past Exhibition

The Salem Witch Trials: Restoring Justice

September 2 to November 26, 2023

The Salem Witch Trials: Reckoning and Reclaiming

September 18, 2021 to March 20, 2022

The Salem Witch Trials 1692 (2020 Exhibition)

November 21, 2020 to March 14, 2021

Keep exploring

Pemcast 24: a fresh lens on the salem witch trials.

25 min listen

Exploring Frances F. Denny’s portraits of modern-day witches

Halloween is over, but the witches are still marching

10 Min Read

Historic Houses

John Ward House

Built in 1685-1699 0.1 miles from PEM

Stay up to date.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

43 Overview of the Salem Witch Trials

Various Authors

The Salem Witch Trials

The Salem witch trials of 1692 were the earliest examples of mass hysteria in the country.

Introduction

The Salem witch trials were a series of hearings and prosecutions of people accused of witchcraft in colonial Massachusetts between February 1692 and May 1693. The trials resulted in the executions of 20 people, 14 of them women and all but one by hanging. Five others (including two infant children) died in prison.

Twelve other women had previously been executed for witchcraft in Massachusetts and Connecticut during the 17th century. The episode is one of colonial America’s most notorious cases of mass hysteria. It has been used in political rhetoric and popular literature as a vivid cautionary tale about the dangers of isolationism, religious extremism, false accusations, and lapses in due process. What happened in colonial America was not unique, but rather an example of the much broader phenomenon of witch trials that occurred during the early modern period throughout England and France.

Puritan Beliefs and Witchcraft

Like many other Europeans, the Puritans of New England believed in the supernatural. Every event in the colonies appeared to be a sign of God’s mercy or judgment, and it was commonly believed that witches allied themselves with the Devil to carry out evil deeds or cause deliberate harm. Events such as the sickness or death of children, the loss of cattle, and other catastrophes were often blamed on the work of witches.

Women were more susceptible to suspicions of witchcraft because they were perceived, in Puritan society, to have weaker constitutions that were more likely to be inhabited by the Devil. Women healers with knowledge of herbal remedies—things that could often deemed “pagan” by Puritans—were particularly at risk of being accused of witchcraft.

Hundreds were accused of witchcraft including townspeople whose habits or appearance bothered their neighbors or who appeared threatening for any reason. Women made up the vast majority of suspects and those who were executed. Prior to 1692, there had been rumors of witchcraft in villages neighboring Salem Village and other towns. Cotton Mather, a minister of Boston’s North Church (not to be confused with the later Anglican North Church associated with Paul Revere), was a prolific publisher of pamphlets, including some that expressed his belief in witchcraft.

The Salem Trials

In Salem Village, in February 1692, Betty Parris, age 9, and her cousin Abigail Williams, age 11, began to have fits in which they screamed, threw things, uttered strange sounds, crawled under furniture, and contorted themselves into peculiar positions. A doctor could find no physical evidence of any ailment, and other young women in the village began to exhibit similar behaviors. Colonists suspected witchcraft and accusations began to spread.

The first three people accused and arrested for allegedly causing the afflictions were Sarah Good (a homeless beggar), Sarah Osborne (a woman who rarely attended church), and Tituba (an African or American Indian slave). Each of these women was a kind of outcast and exhibited many of the character traits typical of the “usual suspects” for witchcraft accusations. They were left to defend themselves.

Throughout the year, more women and some men were arrested, including citizens in good standing, and colonists began to fear that anyone could be a witch. Many of the accusers who prosecuted the suspected witches had been traumatized by the American Indian wars on the frontier and by unprecedented political and cultural changes in New England. Relying on their belief in witchcraft to help make sense of their changing world, Puritan authorities executed 20 people and caused the deaths of several others before the trials were over.

Figure 1. Map Of Salem Village, 1692

Boundless US History , Lumen Learning, CC-BY-SA

Image Credit:

Figure 1. “Map Of Salem Village, 1692,” William Upham, Wikimedia , Public Domain.

American Literature I: An Anthology of Texts From Early America the Early 20th Century Copyright © 2019 by Various Authors is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

The Salem Witch Trials

Find out what started the witch hunt of 1692.

One freezing day in January of 1692, something strange happened inside the Parris household of Salem Village, Massachusetts . As sleet and snow heaped higher outside their door, Betty Parris and her cousin Abigail began to twitch and twist their bodies into strange shapes, speaking in words that made no sense. Betty’s alarmed father, the Reverend Parris, immediately called on a doctor to examine the girls. The doctor’s diagnosis? The pair had been bewitched.

At the time, Salem Village was a small New England town populated mostly by Puritans, or religious individuals with a belief in the devil. The Puritan way of life was strict, and even small differences in behavior made people suspicious. Upon hearing about the Parris girls’ behavior, much of the Puritan community agreed that the duo had been victims of witchcraft.

When asked who had done this to them, Betty and Abigail blamed three townswomen, including Tituba, a Native American slave who worked in the Parris household. Tituba was known to have played fortune-telling games , which were strictly forbidden by the Puritans. The other two accused women, Sarah Good and Sarah Osbourne, weren’t well liked by the community either.

The three women were thrown in jail to await trial for practicing witchcraft. During the trial, Tituba confessed to having seen the devil and also stated that there was a coven, or group, of witches in the Salem Village area. Good and Osbourne insisted they were innocent. The court didn’t believe them, and found all three women guilty of practicing witchcraft. The punishment was hanging.

As the weeks passed, other young girls claimed to have been infected by witchcraft too. They accused other townspeople of torturing them, and a few of the so-called witches on trial even named others as witches.

Women were not the only ones believed to be witches—men and children were accused too. By the end of the trials in 1693, 24 people had died, some in jail but most by hanging.

THE HYSTERIA FADES

Eventually, after seeming to realize how unfair the trials were to the accused, the court refused to hear any more charges of witchcraft. All of the accused were finally pardoned in 1711.

No one’s really sure why the witch craze spread the way it did, but it brought lasting changes to the United States legal system and the way evidence and witnesses were treated. The Salem Village hangings were the last executions of accused witches in the United States.

Text adapted from the National Geographic book Witches! The Absolutely True Tale of Disaster in Salem by Rosalyn Schnauzer.

more to explore

Women heroes, women's history month, the women's suffrage movement, african american heroes.

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Your California Privacy Rights

- Children's Online Privacy Policy

- Interest-Based Ads

- About Nielsen Measurement

- Do Not Sell My Info

- National Geographic

- National Geographic Education

- Shop Nat Geo

- Customer Service

- Manage Your Subscription

Copyright © 1996-2015 National Geographic Society Copyright © 2015-2024 National Geographic Partners, LLC. All rights reserved

MA in American History : Apply now and enroll in graduate courses with top historians this summer!

- AP US History Study Guide

- History U: Courses for High School Students

- History School: Summer Enrichment

- Lesson Plans

- Classroom Resources

- Spotlights on Primary Sources

- Professional Development (Academic Year)

- Professional Development (Summer)

- Book Breaks

- Inside the Vault

- Self-Paced Courses

- Browse All Resources

- Search by Issue

- Search by Essay

- Become a Member (Free)

- Monthly Offer (Free for Members)

- Program Information

- Scholarships and Financial Aid

- Applying and Enrolling

- Eligibility (In-Person)

- EduHam Online

- Hamilton Cast Read Alongs

- Official Website

- Press Coverage

- Veterans Legacy Program

- The Declaration at 250

- Black Lives in the Founding Era

- Celebrating American Historical Holidays

- Browse All Programs

- Donate Items to the Collection

- Search Our Catalog

- Research Guides

- Rights and Reproductions

- See Our Documents on Display

- Bring an Exhibition to Your Organization

- Interactive Exhibitions Online

- About the Transcription Program

- Civil War Letters

- Founding Era Newspapers

- College Fellowships in American History

- Scholarly Fellowship Program

- Richard Gilder History Prize

- David McCullough Essay Prize

- Affiliate School Scholarships

- Nominate a Teacher

- Eligibility

- State Winners

- National Winners

- Gilder Lehrman Lincoln Prize

- Gilder Lehrman Military History Prize

- George Washington Prize

- Frederick Douglass Book Prize

- Our Mission and History

- Annual Report

- Contact Information

- Student Advisory Council

- Teacher Advisory Council

- Board of Trustees

- Remembering Richard Gilder

- President's Council

- Scholarly Advisory Board

- Internships

- Our Partners

- Press Releases

History Resources

Cotton Mather’s account of the Salem witch trials, 1693

A spotlight on a primary source by cotton mather.

Cotton Mather, a prolific author and well-known preacher, wrote this account in 1693, a year after the trials ended. Mather and his fellow New Englanders believed that God directly intervened in the establishment of the colonies and that the New World was formerly the Devil’s territory. Cotton Mather’s account of the witch trials reinforced colonial New Englanders’ view of themselves as a chosen generation of men.

The Salem witch scare had complex social roots beyond the community’s religious convictions. It drew upon preexisting rivalries and disputes within the rapidly growing Massachusetts port town: between urban and rural residents; between wealthier commercial merchants and subsistence-oriented farmers; between Congregationalists and other religious denominations—Anglicans, Baptists, and Quakers; and between American Indians and Englishmen on the frontier. The witch trials offer a window into the anxieties and social tensions that accompanied New England’s increasing integration into the Atlantic economy.

A transcribed excerpt is available.

Wherefore The devil is now making one Attempt more upon us; an Attempt more Difficult, more Surprizing, more snarl’d with unintelligible Circumstances than any that we have hitherto Encountered; an Attempt so Critical, that if we get well through, we shall soon Enjoy Halcyon Days, with all the Vultures of Hell Trodden under our Feet. He has wanted his Incarnate Legions to Persecute us, as the People of God have in the other Hemisphere been Persecuted: he has therefore drawn forth his more spiritual ones to make an attacque upon us. We have been advised by some Credible Christians yet alive, that a Malefactor, accused of Witchcraft as well as Murder, and Executed in this place more than Forty Years ago, did then give Notice of, An Horrible PLOT & against the Country by WITCHCRAFT, and a Foundation of WITCHCRAFT then laid, which if it were not seasonably discovered, would probably Blow up, and pull down all the Churches in the Country. And we have now with Horror seen the Discovery of such a WITCHCRAFT!

Questions for Discussion

Read the document introduction and transcript and apply your knowledge of American history in order to answer these questions.

- The events in Salem and other towns in New England took place in a region of isolated villages and towns. What part might this physical separation have played in turning neighbors against one another and stoking fears of demons?

- According to Cotton Mather, what are the immediate and long-term goals of the Devil?

- We now know that some of the accused were pre-teens. Why might their age make them particularly susceptible to accusations of strange behavior?

- Describe a relatively recent historical event that resembles the situation that unfolded in Salem.

*** Beyond Arthur Miller’s The Crucible , numerous dramatic presentations offer insights into irrational human fear. For example, “The Monsters Are Due on Maple Street,” an episode of Rod Serling’s Twilight Zone series, may provide students and teachers an opportunity to examine the phenomenon of mass hysteria.

A printer-friendly version is available here .

Stay up to date, and subscribe to our quarterly newsletter..

Learn how the Institute impacts history education through our work guiding teachers, energizing students, and supporting research.

What Caused the Salem Witch Trials?

Looking into the underlying causes of the Salem Witch Trials in the 17th century.

In February 1692, the Massachusetts Bay Colony town of Salem Village found itself at the center of a notorious case of mass hysteria: eight young women accused their neighbors of witchcraft. Trials ensued and, when the episode concluded in May 1693, fourteen women, five men, and two dogs had been executed for their supposed supernatural crimes.

The Salem witch trials occupy a unique place in our collective history. The mystery around the hysteria and miscarriage of justice continue to inspire new critiques, most recently with the recent release of The Witches: Salem, 1692 by Pulitzer Prize-winning Stacy Schiff.

But what caused the mass hysteria, false accusations, and lapses in due process? Scholars have attempted to answer these questions with a variety of economic and physiological theories.

The economic theories of the Salem events tend to be two-fold: the first attributes the witchcraft trials to an economic downturn caused by a “little ice age” that lasted from 1550-1800; the second cites socioeconomic issues in Salem itself.

Emily Oster posits that the “little ice age” caused economic deterioration and food shortages that led to anti-witch fervor in communities in both the United States and Europe in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Temperatures began to drop at the beginning of the fourteenth century, with the coldest periods occurring from 1680 to 1730. The economic hardships and slowdown of population growth could have caused widespread scapegoating which, during this period, manifested itself as persecution of so-called witches, due to the widely accepted belief that “witches existed, were capable of causing physical harm to others and could control natural forces.”

Salem Village, where the witchcraft accusations began, was an agrarian, poorer counterpart to the neighboring Salem Town, which was populated by wealthy merchants. According to the oft-cited book Salem Possessed by Paul Boyer and Stephen Nissenbaum, Salem Village was being torn apart by two opposing groups–largely agrarian townsfolk to the west and more business-minded villagers to the east, closer to the Town. “What was going on was not simply a personal quarrel, an economic dispute, or even a struggle for power, but a mortal conflict involving the very nature of the community itself. The fundamental issue was not who was to control the Village, but what its essential character was to be.” In a retrospective look at their book for a 2008 William and Mary Quarterly Forum , Boyer and Nissenbaum explain that as tensions between the two groups unfolded, “they followed deeply etched factional fault lines that, in turn, were influenced by anxieties and by differing levels of engagement with and access to the political and commercial opportunities unfolding in Salem Town.” As a result of increasing hostility, western villagers accused eastern neighbors of witchcraft.

But some critics including Benjamin C. Ray have called Boyer and Nissenbaum’s socio-economic theory into question . For one thing –the map they were using has been called into question. He writes: “A review of the court records shows that the Boyer and Nissenbaum map is, in fact, highly interpretive and considerably incomplete.” Ray goes on:

Contrary to Boyer and Nissenbaum’s conclusions in Salem Possessed, geo graphic analysis of the accusations in the village shows there was no significant villagewide east-west division between accusers and accused in 1692. Nor was there an east-west divide between households of different economic status.

On the other hand, the physiological theories for the mass hysteria and witchcraft accusations include both fungus poisoning and undiagnosed encephalitis.

Linnda Caporael argues that the girls suffered from convulsive ergotism, a condition caused by ergot, a type of fungus, found in rye and other grains. It produces hallucinatory, LSD-like effects in the afflicted and can cause victims to suffer from vertigo, crawling sensations on the skin, extremity tingling, headaches, hallucinations, and seizure-like muscle contractions. Rye was the most prevalent grain grown in the Massachusetts area at the time, and the damp climate and long storage period could have led to an ergot infestation of the grains.

One of the more controversial theories states that the girls suffered from an outbreak of encephalitis lethargica , an inflammation of the brain spread by insects and birds. Symptoms include fever, headaches, lethargy, double vision, abnormal eye movements, neck rigidity, behavioral changes, and tremors. In her 1999 book, A Fever in Salem , Laurie Winn Carlson argues that in the winter of 1691 and spring of 1692, some of the accusers exhibited these symptoms, and that a doctor had been called in to treat the girls. He couldn’t find an underlying physical cause, and therefore concluded that they suffered from possession by witchcraft, a common diagnoses of unseen conditions at the time.

The controversies surrounding the accusations, trials, and executions in Salem, 1692, continue to fascinate historians and we continue to ask why, in a society that should have known better, did this happen? Economic and physiological causes aside, the Salem witchcraft trials continue to act as a parable of caution against extremism in judicial processes.

Editor’s note: This post was edited to clarify that Salem Village was where the accusations began, not where the trials took place.

JSTOR is a digital library for scholars, researchers, and students. JSTOR Daily readers can access the original research behind our articles for free on JSTOR.

Get Our Newsletter

Get your fix of JSTOR Daily’s best stories in your inbox each Thursday.

Privacy Policy Contact Us You may unsubscribe at any time by clicking on the provided link on any marketing message.

More Stories

- Haunted Soldiers in Mesopotamia

- The Post Office and Privacy

- The British Empire’s Bid to Stamp Out “Chinese Slavery”

- Tramping Across the USSR (On One Leg)

Recent Posts

- Debt-Trap Diplomacy

Support JSTOR Daily

Sign up for our weekly newsletter.

Home — Essay Samples — History — History of the United States — Salem Witch Trials

Essays on Salem Witch Trials

Salem witch trials essay topics and outline examples, essay title 1: the salem witch trials: an examination of mass hysteria and its consequences.

Thesis Statement: The Salem Witch Trials of 1692 were a tragic chapter in American history characterized by mass hysteria, social dynamics, and the persecution of innocent individuals, and this essay explores the factors that led to the witch trials and their enduring legacy.

- Introduction

- The Historical Context of Puritan New England

- The Outbreak of Accusations and the Role of Fear

- The Trials and Executions

- Analysis of Social and Psychological Factors

- The Legacy of the Salem Witch Trials

Essay Title 2: The Accused and the Accusers: Uncovering Motivations and Identities in the Salem Witch Trials

Thesis Statement: A closer examination of the accused witches and their accusers in the Salem Witch Trials reveals a complex interplay of personal grievances, social dynamics, and religious fervor that contributed to the tragedy.

- The Accused: Their Backgrounds and Vulnerabilities

- The Accusers: Motivations and Social Positions

- The Legal Proceedings and the Role of Spectral Evidence

- Repercussions on the Accused and the Accusers

Essay Title 3: Lessons from Salem: Examining the Salem Witch Trials in Historical Context

Thesis Statement: The Salem Witch Trials serve as a cautionary tale about the dangers of unchecked power, religious extremism, and the need for a fair and just legal system, and this essay explores the enduring relevance of the trials in contemporary society.

- Comparing the Salem Witch Trials to Other Historical Witch Hunts

- Exploring the Role of Religion and Superstition

- Lessons for Modern Justice Systems and Civil Liberties

- Preserving the Memory and Lessons of the Salem Witch Trials

Salem Witch Trials Unfair

Mass hysteria in the crucible, made-to-order essay as fast as you need it.

Each essay is customized to cater to your unique preferences

+ experts online

Salem Witch Trials: Film Analysis

The cause of the salem witch trials and the role of the puritan views and values in colonial massachusetts, conflict in the salem witch trials, the causes of the salem witch trial hysteria of 1962, let us write you an essay from scratch.

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Causes and Effects of The Salem Witch Trials

A brief history of the salem witch trials, why salem witch trials were aimed solely at women, the motivations behind the salem witch trials, get a personalized essay in under 3 hours.

Expert-written essays crafted with your exact needs in mind

How Cotton Mather’s Influence Caused The Salem Witch Trial Hysteria of 1692

The salem witch trials and the women victims, a research on what caused the salem witch trial hysteria of 1692, the salem witch trials and mccarthyism: a comparative analysis, depiction of the salem witch trials of 1692 in "the crucible" by arthur miller, tituba as the first woman accused of practicing witchcraft, the theories around what caused the salem witch trial hysteria of 1692, causes of witchcraft mass hysteria in salem, freedom for the people: the possible speech of mary warren, giles corey and the salem witchcraft trials, the sins of fear: arthur miller’s the crucible and the treatment of arab-americans after 9/11, social structure change as a root cause of the salem witch trial hysteria of 1692, escaping salem: how one person can make a difference, the arrest of sarah cloyce and elizabeth (bassett) proctor, reverend hale: a spiritual doctor, exploring the link between 'the lottery' and the witch trials, red scare: america’s fear of terrorism, tituba accused the salem witch trials, reverend hale's evolution in "the crucible" by arthur miller, salem witch trials dbq.

May 1692 - October 1692

United States

The Salem witchcraft trials were a series of hearings and prosecutions that took place in colonial Massachusetts, specifically in the town of Salem, between 1692 and 1693. These trials were a dark chapter in American history, characterized by the mass hysteria and persecution of individuals accused of practicing witchcraft. The trials were sparked by the strange and unexplained behavior of several young girls, who claimed to be afflicted by witches. This led to a frenzy of accusations and trials, where numerous people, primarily women, were accused of consorting with the Devil and practicing witchcraft. During the trials, the accused individuals faced unfair and biased proceedings, often based on hearsay, spectral evidence, and superstitions. Many innocent people were wrongly convicted and subjected to harsh punishments, including imprisonment and even execution.

The Salem witch trials occurred in the late 17th century in the Massachusetts Bay Colony, which was a Puritan society deeply rooted in religious beliefs and strict social hierarchies. The trials took place against the backdrop of a tense and uncertain period, marked by political, social, and religious upheaval. In the years leading up to the trials, the colony faced challenges such as territorial disputes, conflicts with Native American tribes, and economic instability. Additionally, the Puritan community was grappling with the concept of witchcraft, influenced by prevailing beliefs in Europe at the time. The prevailing religious ideology, which emphasized a strict interpretation of Christianity, fostered a climate of fear and suspicion. The Puritans believed that witchcraft was a serious offense and that the Devil could infiltrate their community. This mindset, combined with existing social tensions and personal rivalries, created fertile ground for the accusations and subsequent trials.