Marriage Equality: Same-Sex Marriage Essay (Critical Writing)

Introduction, same sex unions, history of same sex unions, debate on gay marriage.

Marriage has been regarded as one of the most important social institutions in the society. This is because it forms the basis of organization in any given society. “Marriage refers to an institution in which interpersonal relationships, usually intimate and sexual, are acknowledged in a variety of ways, depending on the culture or subculture in which it is found” (Dziengel, 2010).

Marriage is treated quite differently depending on the norms and values that exist in a given society. The current society is experiencing many social changes, which have influenced the nature of relationships among human beings. Marriage has also been affected by these social changes.

Marriage is today very dynamic and people treat it differently from what it used to be in the past. Same sex unions are becoming popular in many countries and they are quite prevalent in European countries as compared to other places. Same sex marriage is commonly known as gay marriage. “It refers to a legally or socially recognized marriage between two persons of the same biological sex or social gender” (Goldberg, 2010).

“Various types of same sex marriages have existed, ranging from informal, unsanctioned relationships to highly ritualized unions” (Haider & Joslyn, 2008). The early practice of this type of marriage was witnessed when Emperor Nero married a man who was serving as a servant in his Roman Empire.

Apart from Rome, this practice occurred in China during the Ming Dynasty and also in Spain. This type of marriage had very bad reputation and it was strongly rejected by many individuals and countries. “This attitude has been changing in the past few decades” (Haider & Joslyn, 2008). The twenty first century has witnessed a drastic change in the way people perceive this type of relationship.

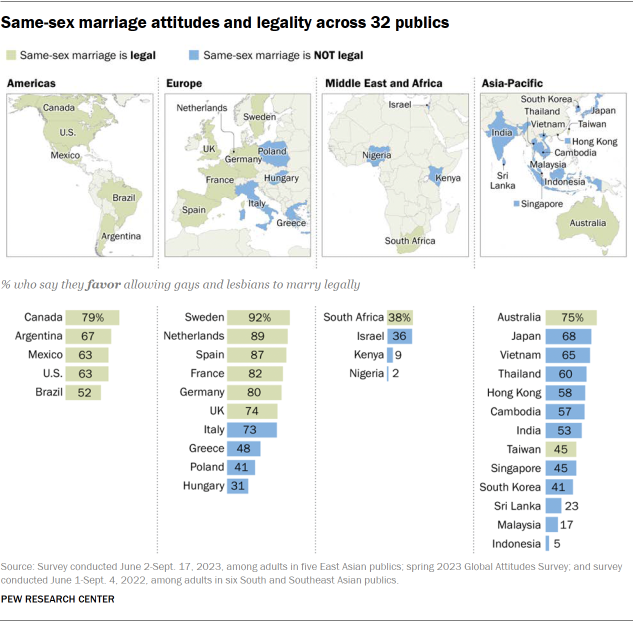

Netherlands in the year 2001 emerged to be the first country to allow gay relationships. In 2003 the government of Belgium accepted this type of union. In 2005 both Canada and Spain formally accepted gay marriages. In 2006 the people of South African were allowed to practice gay marriages.

Sweden allowed it in 2009. Last year, Argentina, Iceland and Portugal also accepted this kind of relationship. In Mexico it is legalized but with some restrictions in the sense that it can only be practiced within the city of Mexico. However, all Mexican states acknowledge it.

“Israel does not recognize same sex marriages performed on its territory, but recognizes same sex marriages performed in foreign jurisdiction” (Ronner, 2005). Apart form South Africa, other African countries still remain conservative and they are not willing to accept this relationship. “In the United States, although same sex marriages are not recognized federally, same sex couples can marry in five states and one district” (Smith, 2010).

Opposing Arguments

The subject of gay marriage has been seriously debated in many places. This issue has been discussed both in religious and political circles. The following arguments have been used to reject gay marriage.

The general question is that why should people practice this kind of relationship? This is what the majority of people opposed to it seem to be asking whenever this issue is raised in any discussion. This people contend that legal relationships are only those between men and women. Hence they do not see the sense of people engaging in any other type of intimate relationship (Ronner, 2005).

Marriage is often seen as a religious rite and in this case people look at it from the religious perspective. They therefore believe that if gay marriage is legitimized it would undermine the religious principles. This is because religion has always been used to sanctify marriages (Farrior, 2009).

The dignity of the church has been affected because of the different attitudes adopted by religious leaders on this matter. Some churches are likely to get split because they cannot come to an agreement on how to handle this issue. This has adversely affected their capacity to spread the gospel. Some members of the church have even lost their faith and trust in religion because they do not agree with the church leaders who support this kind of relationship.

For example, the Anglican Church members and their leaders have been arguing about gay marriages. Since some of them support it, they have now formed a separate church. The Catholic Church has also had the same problem. Some Catholic monks have also been accused of child molestation and this has really affected their reputation.

Marriage is naturally understood as an institution for raising children. Same sex marriages do not give children an opportunity to have a good development. “In this case some individuals strongly feel that same sex partners can not provide the moral and psychological support required for raising children” (Goldberg, 2010). This is because such children would find it quite unusual when they realize that their parents have the same sex. This can really affect them psychologically (Goldberg, 2010).

Gay marriages are understood as unnatural unions. “This premise influences other arguments and lies behind many negative opinions about homosexuality in general” (Acevado & Wada, 2011). Since gay relationships are not normal, they should be reduced to social unions instead of being authenticated by the national leaders in a given country. This is because if such abnormal behaviors are allowed, they are likely to become very prevalent in our society in the near future. This may cause very many social problems.

Marriage is also an important cultural symbol. “Apart from marriage being an institution, it is also a symbol representing our culture’s ideals about sex, sexuality, and human relationships” (Haider & Joslyn, 2008). Symbols are very important because it is through them that we develop a sense of belonging to a given society or race. “Thus when the traditional nature of marriage is challenged in any way, so are people’s basic identities” (Haider & Joslyn, 2008).

It would also be difficult and expensive to integrate this people into the society. This is because people have to be taught to accept them. “Teaching people to become tolerant to gay individuals would be expensive” (Smith, 2010).

Supporting Arguments

Even though gay marriage is not supported by some people, I disagree with them because of the following arguments.

Marriage enables people to have access to social and economic needs. “Studies repeatedly demonstrate that people who marry tend to be better off financially, emotionally, psychologically, and even medically” (Ronner, 2005). Therefore if gay couples are guaranteed the right to marry they will probably have the chance to benefit from being married. This will also be helpful to the gay communities at large. For example the gay couples would remain committed in helping each other because of the marriage vows.

It would also be wrong for gay relationships to be treated as civil unions. This is because if the gay individuals can get married, they stand a better chance of enjoying several opportunities. This can not be the case if they are in civil unions. “Equality before the law means that creating civil unions for gays will lead to civil unions for every one else and this type of marriage will be more of a threat than gay unions could possibly be” (Farrior, 2009).

The stability of our society can be enhanced if gay individuals can be given a chance to marry. Even the people who oppose this relationship believe that the family is the basis of our society. Therefore, if more families are formed through gay marriages, we can have a great society. The family also dictates the general trend in the society. Marriage would also facilitate the integration of gay people into their communities. Accepting gay relationships will therefore enhance the strength of our communities.

Many children are leading poor lifestyles and they cannot even access the common basic needs. Destitute children can have a chance to lead a good life if they can be adopted by married gay individuals. This is because they can provide emotional and financial support to such children. This can only be possible if they can be allowed to get married and adopt children.

Many people and groups are increasingly becoming conscious, and more concerned about the human rights. “Another argument that favors same sex marriages is that denying same sex couples legal access to marriage and all of its attendant benefits represents discrimination based on sexual orientation” (Dziengel, 2010). Many people and institutions promoting human rights concur with this assertion. People in same sex unions do not access the rights given to the married people.

Gay couples have faced myriad challenges. Most of them have experienced psychological problems associated with verbal and physical abuse. For example, some of them have been attacked and brutally killed. This is because many people are not wiling to be associated with them hence they always intimidate them. One way of eliminating this stigmatization is by simply making it legal for them to get married.

It has also been noted with a lot of concern that HIV/AIDS is spreading among the gay people because they operate illegally. Marriage would make this people more faithful to their partners. This can reduce the chances of them contracting HIV/AIDS because they will be more responsible.

From the above argument it is very clear that many countries and individuals are increasingly accepting the fact that gay relationships are equally good. It is therefore important for people to stop being conservative only when it comes to marriage, yet they accept other serious changes that take place in their society.

For example, if abortion can be legalized, why no not gay marriages? “Legalizing gay marriages will probably make the social economic and political institutions in our societies more effective” (Smith, 2010). This is because people will have similar goals, and they will not have differences based on sexual orientation. I am therefore optimistic that in the near future many people will support same sex relationships.

Acevado, G., & Wada, R. (2011). Religion and attitudes toward same sex marriages among U.S. Latinos. Wiley -Blackwell Social Science Quarterly , 92, 35-56.

Benard, S. (2009). Heterosexual previlage awareness, previlage and support of gay marriage among diversity course students. EBSCOhost Journal , 58, 3-7.

Dziengel, L. (2010). Advocacy coalitions and punctuated equilibriam in the same sex marriage debate: learning from pro-LGBT policy changes in Minneapolis and Minnesota. Journal of Gay and Lesbian services , 22, 165-182.

Farrior, S. (2009). Human rights advocacy on gender issues: challanges and opportunites. Oxford Journal of Human Rights Practice , 1, 83-100.

Goldberg, A. (2010). Lesbian and gay parents and their children: research on the family life cycle. Claiming a place at the family table: gay and lesbian families in the 21st century , 72, 230-233.

Haider, D., & Joslyn, M. (2008). Belives about the origin of homosexuality and support for gay rights. Oxford Journals public Opinion Quarterly , 72, 291-310.

Ronner, A. (2005). Homophobia and the law (law and public policy). New York: American Psychological Association.

Smith, M. (2010). Gender politics and same sex marriage debate in the United States. Oxford Jourrnals Social Politics , 17, 1-28.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2018, August 23). Marriage Equality: Same-Sex Marriage. https://ivypanda.com/essays/same-sex-marriage-2/

"Marriage Equality: Same-Sex Marriage." IvyPanda , 23 Aug. 2018, ivypanda.com/essays/same-sex-marriage-2/.

IvyPanda . (2018) 'Marriage Equality: Same-Sex Marriage'. 23 August.

IvyPanda . 2018. "Marriage Equality: Same-Sex Marriage." August 23, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/same-sex-marriage-2/.

1. IvyPanda . "Marriage Equality: Same-Sex Marriage." August 23, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/same-sex-marriage-2/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Marriage Equality: Same-Sex Marriage." August 23, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/same-sex-marriage-2/.

- Gay Marriage and Parenting

- Arguments for Supporting Same-Sex Marriage

- Factors Influencing Perception on Same-sex marriage in the American Society

- Why Gay Marriage Should Not Be Legal

- Gay Marriage Legalization

- Balancing Studies, Work, and Family Life

- Emotions and reasoning

- Correlation Between Multiple Pregnancies and Postpartum Depression or Psychosis

Evidence is clear on the benefits of legalising same-sex marriage

PhD Candidate, School of Arts and Social Sciences, James Cook University

Disclosure statement

Ryan Anderson does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

James Cook University provides funding as a member of The Conversation AU.

View all partners

Emotive arguments and questionable rhetoric often characterise debates over same-sex marriage. But few attempts have been made to dispassionately dissect the issue from an academic, science-based perspective.

Regardless of which side of the fence you fall on, the more robust, rigorous and reliable information that is publicly available, the better.

There are considerable mental health and wellbeing benefits conferred on those in the fortunate position of being able to marry legally. And there are associated deleterious impacts of being denied this opportunity.

Although it would be irresponsible to suggest the research is unanimous, the majority is either noncommittal (unclear conclusions) or demonstrates the benefits of same-sex marriage.

Further reading: Conservatives prevail to hold back the tide on same-sex marriage

What does the research say?

Widescale research suggests that members of the LGBTQ community generally experience worse mental health outcomes than their heterosexual counterparts. This is possibly due to the stigmatisation they receive.

The mental health benefits of marriage generally are well-documented . In 2009, the American Medical Association officially recognised that excluding sexual minorities from marriage was significantly contributing to the overall poor health among same-sex households compared to heterosexual households.

Converging lines of evidence also suggest that sexual orientation stigma and discrimination are at least associated with increased psychological distress and a generally decreased quality of life among lesbians and gay men.

A US study that surveyed more than 36,000 people aged 18-70 found lesbian, gay and bisexual individuals were far less psychologically distressed if they were in a legally recognised same-sex marriage than if they were not. Married heterosexuals were less distressed than either of these groups.

So, it would seem that being in a legally recognised same-sex marriage can at least partly overcome the substantial health disparity between heterosexual and lesbian, gay, and bisexual persons.

The authors concluded by urging other researchers to consider same-sex marriage as a public health issue.

A review of the research examining the impact of marriage denial on the health and wellbeing of gay men and lesbians conceded that marriage equality is a profoundly complex and nuanced issue. But, it argued that depriving lesbians and gay men the tangible (and intangible) benefits of marriage is not only an act of discrimination – it also:

disadvantages them by restricting their citizenship;

hinders their mental health, wellbeing, and social mobility; and

generally disenfranchises them from various cultural, legal, economic and political aspects of their lives.

Of further concern is research finding that in comparison to lesbian, gay and bisexual respondents living in areas where gay marriage was allowed, living in areas where it was banned was associated with significantly higher rates of:

mood disorders (36% higher);

psychiatric comorbidity – that is, multiple mental health conditions (36% higher); and

anxiety disorders (248% higher).

But what about the kids?

Opponents of same-sex marriage often argue that children raised in same-sex households perform worse on a variety of life outcome measures when compared to those raised in a heterosexual household. There is some merit to this argument.

In terms of education and general measures of success, the literature isn’t entirely unanimous. However, most studies have found that on these metrics there is no difference between children raised by same-sex or opposite-sex parents.

In 2005, the American Psychological Association released a brief reviewing research on same-sex parenting. It unambiguously summed up its stance on the issue of whether or not same-sex parenting negatively impacts children:

Not a single study has found children of lesbian or gay parents to be disadvantaged in any significant respect relative to children of heterosexual parents.

Further reading: Same-sex couples and their children: what does the evidence tell us?

Drawing conclusions

Same-sex marriage has already been legalised in 23 countries around the world , inhabited by more than 760 million people.

Despite the above studies positively linking marriage with wellbeing, it may be premature to definitively assert causality .

But overall, the evidence is fairly clear. Same-sex marriage leads to a host of social and even public health benefits, including a range of advantages for mental health and wellbeing. The benefits accrue to society as a whole, whether you are in a same-sex relationship or not.

As the body of research in support of same-sex marriage continues to grow, the case in favour of it becomes stronger.

- Human rights

- Same-sex marriage

- Same-sex marriage plebiscite

Compliance Lead

Lecturer / Senior Lecturer - Marketing

Assistant Editor - 1 year cadetship

Executive Dean, Faculty of Health

Lecturer/Senior Lecturer, Earth System Science (School of Science)

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

The story of marriage equality is more complicated — and costly — than you remember

Danielle Kurtzleben

Same-sex marriage supporters wear "Just married" shirts while celebrating the U.S Supreme Court ruling regarding same-sex marriage on June 26, 2015 in San Francisco. Justin Sullivan/Getty Images hide caption

Same-sex marriage supporters wear "Just married" shirts while celebrating the U.S Supreme Court ruling regarding same-sex marriage on June 26, 2015 in San Francisco.

Americans' views on same-sex marriage have undergone a revolution in a few short decades.

Public opinion on the issue swung so swiftly and decisively — and so little uproar resulted once it was legal nationwide — that one might easily assume the march toward marriage equality was a neat, steady progression.

But it was in fact a decades-long project that moved in fits and starts. As with pretty much any other political movement, there was disorganization and internal squabbling — many in the LGBTQ+ community didn't even see marriage equality as a priority (or even a worthy goal at all) a couple of decades ago.

And, as with other political movements, copious amounts of money provided a lot of the momentum.

All of that is recounted in The Engagement , journalist Sasha Issenberg's exhaustive, engrossing account of the decades-long fight for marriage equality. The NPR Politics Podcast 's Danielle Kurtzleben spoke with him for the show's regular book club feature. Their conversation is transcribed below and is edited for length and clarity.

Danielle Kurtzleben: Let's start with a very basic question: Why was this book important to write for you? Was the goal just to lay out the history of same-sex marriage, or was it something bigger?

Sasha Issenberg: I came to realize as I was working on it, that this was a kind of history of the American culture wars over the last generation — basically over my lifetime.

You know, I'm 41 years old. I started work on this 10 years ago, and it was the point when we were starting to talk about this as the defining civil rights movement of my generation, and I realized I'd been alive for the whole life of this as an issue. And I did not understand how it had emerged, and in many ways eclipsed not only other concerns to the LGBT community, but lots of other points of conflict or tension within our politics. It came in many ways to dominate American social policy debates for much of my adult life.

More same-sex couples eligible for Social Security survivors benefits

DK: This book also gets at how many of the people fighting for marriage equality were in the same boat, but rowing in different directions, is maybe a way of putting it. What are some good examples of how strategy got so messy?

SI: One thing that I think we as political journalists do terribly, and are often unaware of how terribly we do it, is write about conflicts within movements. You'll read or hear stories that say, 'the labor movement is doing X' or 'evangelicals are doing Y,' and anybody who has spent any time talking to labor leaders or evangelical clergy will realize that they spend much more time often bickering among themselves than they do necessarily thinking about how to work in a unified way.

As I dug into this history, that really became clear. What we would call the "gay rights movement" or the "LGBT community," that's a very big coalition, and there are a whole lot of different constituencies: gay men and lesbians who are invested in marriage, [as well as] bisexual and transgender people who often could marry the people that they love, regardless of what state law was about marriage.

And within the LGBT community, there are a lot of different policy concerns. You go back to the 1990s when this debate emerged, and there were people whose top priority was desegregating military and government service so openly gay people could serve, or who wanted just basic nondiscrimination protections, [like] writing sexual orientation into hate crimes laws.

And one of the sort of remarkable parts of the story is not just how ultimately gay marriage campaigners triumphed over opponents of same-sex marriage, but how within their own LGBT community and political movement, they raised the issue of marriage so that it went higher and higher on the list of priorities.

More Republican leaders try to ban books on race, LGBTQ issues

Frankly, a lot of that was driven by money. I told the story of a circle of very wealthy donors led by Tim Gill, who had been a software pioneer. And [he] decides that a lot of his philanthropy is going to be about gay rights. And marriage is the issue that resonates most with him.

Tim Gill attends a charity event to support LGBTQ youth in New York City on June 1, 2015. Bennett Raglin/Getty Images for GLSEN hide caption

And he ends up bringing together a circle of like-minded donors, almost all of whom are men who have either made their money through founding companies or through inheritance, who are very concerned about marriage — I think in part because very wealthy people spend a lot of time worrying about estate planning.

They build an infrastructure that is focused on marriage above — and maybe at the expense of — some of these other priorities and help bring together some of the leading lawyers and strategists in the movement.

I write about a meeting that they had in the spring of 2005, when a lot of gay rights activists saw this cause at a low point, and they set out a path to get a winning case before the Supreme Court within 20 years.

That forced other, established gay rights groups like the Human Rights Campaign or the National Gay and Lesbian Task Force to adjust their priorities, because they realized that the major money within their community cared about marriage. And if they weren't doing marriage work, they were going to lose out on some of that funding.

The U.S. Navy has christened a ship named after slain gay rights leader Harvey Milk

DK: Let's talk about the Supreme Court, which of course is a huge part of this book. You really get at the complex relationship between the Supreme Court and public opinion, and this is the thing that I'm always curious about: is it something justices pay attention to, and how does it affect them?

SI: We have a tough time figuring out what justices pay attention to because they're often not in real time public about their thoughts. But all the folks who are working on this issue operated from the assumption that the justices were not operating in some sort of vacuum — purposeful or inadvertent — in which they were oblivious to what was going on in the world around them.

And so in that 2005 strategy meeting I mentioned, they map out a 20-year path to a successful Supreme Court decision. What is seen as wildly optimistic at that point is getting before the Supreme Court in 2025. What they assumed was that the court would be willing to take bold stands for civil rights, as it has in its history, but that they did not want to be seen as working from a minority position — that the court wanted to be in a position where they were happy sort of reining in outlier states, as they did when they struck down school segregation, for example.

Plaintiff Jim Obergefell holds a photo of his late husband John Arthur as he speaks to members of the media after the U.S. Supreme Court handed down a ruling in favor of same-sex marriage rights on June 26, 2015 outside the court in Washington, D.C. Alex Wong/Getty Images hide caption

Plaintiff Jim Obergefell holds a photo of his late husband John Arthur as he speaks to members of the media after the U.S. Supreme Court handed down a ruling in favor of same-sex marriage rights on June 26, 2015 outside the court in Washington, D.C.

DK: But why would the court be worried about public opinion if they're ruling on constitutionality?

As people have said, the court gets its legitimacy from the other branches of government, from state and local governments, and thus from the public. And so, whatever the joke was that the Supreme Court doesn't have any army — they have no ability to enforce their decisions with anything other than both the public and governments that will go along and accept them.

One of the things I certainly expected after the Supreme Court ruled in 2015, that there would be more examples of local resistance in conservative states, mostly in the South and the rural West, where I thought there would be county clerks, county executives, governors, state attorneys general who said, "We will not enforce this order." And ultimately almost all of them dropped their opposition pretty quickly. I think that is a sign of a legitimacy that the court has earned over years by not taking decisions that public opinion and local politicians would not be willing to sustain. I think that's the big deal that we've had since the founding of the republic that gives court decisions their force.

DK: Another big question that I think a lot of us have continually had is, how exactly did opinion on same-sex marriage change? It has swung so decisively towards marriage equality during our lifetimes.

SI: Yeah, this is one of the things that drew me into this mystery 10 years ago. I was having a lot of conversations with pollsters who would tell me they had not seen opinion on a single issue move as quickly as it moved on marriage. And at that point, attitudes were moving 4 or 5 percentage points a year, only in one direction.

People now, in part, I think because of pop culture or general cultural acceptance, feel more comfortable coming out than they did a generation ago. People are realizing that they know people who are gay. Social scientists call this "contact theory" — the idea that we become more sympathetic or friendly due to the concerns of people once we've had personal contact with them. And it becomes a lot easier to be open, I think, to the arguments for same-sex marriage and more resistant to the arguments that were made against it when you know somebody in your life who is gay or lesbian and see the fundamental humanity of them, and in a certain way, the fundamental modesty of the demand for them to share their life with somebody they love.

Latin America

Chile's congress approves same-sex marriage by an overwhelming majority.

DK: There's one question that we got from various listeners, including Vidya Ravella. She asked, "What's the action plan for all the legal challenges that are expected? If there's a concerted effort to overturn this right, as is expected, this is the next fight, particularly if Roe is overturned this summer."

So before we even get to this question, maybe let's back up and ask how likely do you think it is that Obergefell could be overturned?

I do not think that there is any serious likelihood that the core holding of Obergefell , that the fundamental right to marry should extend to same-sex couples, is in doubt. And I think a large part of that is that it is politically unappealing. There's not a political demand for it the way there is a political demand for a change in abortion laws around the country.

I certainly understand why the fear is there for folks. But I think it's worth looking at the intersection of law and politics. Since the Obergefell decision, there were three Supreme Court justices appointed by a Republican president. Many people wanted to know their positions on Roe v. Wade . Nobody cared [about] their positions on Obergefell . Groups are focused on other issues now. Once you get to a point where these justices see 70% of the country looking the other way, regardless of what their sort of personal preferences might be, I think that that becomes a really significant impediment to them taking up this cause.

DK: Does that make marriage equality a unique issue, in that it's much harder to make the case that a same-sex marriage infringes upon your personal rights if you are in a heterosexual marriage? It's harder to make that case than, for example, to make the case that abortion opponents do, that an abortion hurts someone, or as another example, that affirmative action takes something away from someone. Is marriage equality just in its own class?

SI: You can look back at the history of social movements in the United States as on one hand, as these sort of contests over public values, over justice, liberty, freedom, privacy, fairness. You can also often read them very clearly as competitions for scarce resources.

So when women demanded property rights, husbands and fathers saw that as a challenge to their wealth. When women and African Americans demanded the vote, white men saw it as a threat to their political power, and the effort to expand rights or opportunities for immigrants has been seen by native-born people as a threat to their jobs and public benefits. Desegregation of schools set up this rivalry for places in neighborhood institutions on which people saw their property values implicated.

As you say, affirmative action, maybe in the purest sense, sets up a rivalry for jobs or places in academic institutions. Even the Americans with Disabilities Act may force landlords or developers to shift some of their budgets to paying for things that they might not have wanted to pay for. In every case, the majority had to give something up, something tangible to the demands of justice by a minority, right? And I think that that is a really important difference here, and I think made it very difficult to sustain opposition to this, because there weren't really stakeholders on the other side.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Perceived psychosocial impacts of legalized same-sex marriage: A scoping review of sexual minority adults’ experiences

Laurie a. drabble.

1 College of Health and Human Sciences, San José State University, San José, California, United States of America

Angie R. Wootton

2 School of Social Welfare, University of California, Berkeley, California, United States of America

Cindy B. Veldhuis

3 School of Nursing, Columbia University, New York, New York, United States of America

Ellen D. B. Riggle

4 Department of Political Science and Gender and Women’s Studies, University of Kentucky, Lexington, Kentucky, United States of America

Sharon S. Rostosky

5 Educational, Counseling and School Psychology, University of Kentucky, Lexington, Kentucky, United States of America

Pamela J. Lannutti

6 Center for Human Sexuality Studies, Widener University, Chester, Pennsylvania, United States of America

Kimberly F. Balsam

7 Department of Psychology, Palo Alto University, Palo Alto, California, United States of America

Tonda L. Hughes

8 School of Nursing & Department of Psychiatry, Columbia University Irving Medical Center, New York, New York, United States of America

Associated Data

All relevant data are within the manuscript and its Supporting Information files.

A growing body of literature provides important insights into the meaning and impact of the right to marry a same-sex partner among sexual minority people. We conducted a scoping review to 1) identify and describe the psychosocial impacts of equal marriage rights among sexual minority adults, and 2) explore sexual minority women (SMW) perceptions of equal marriage rights and whether psychosocial impacts differ by sex. Using Arksey and O’Malley’s framework we reviewed peer-reviewed English-language publications from 2000 through 2019. We searched six databases (PubMed, PsycINFO, CINAHL, Web of Science, JSTOR, and Sociological Abstracts) to identify English language, peer-reviewed journal articles reporting findings from empirical studies with an explicit focus on the experiences and perceived impact of equal marriage rights among sexual minority adults. We found 59 studies that met our inclusion criteria. Studies identified positive psychosocial impacts of same-sex marriage (e.g., increased social acceptance, reduced stigma) across individual, interpersonal (dyad, family), community (sexual minority), and broader societal levels. Studies also found that, despite equal marriage rights, sexual minority stigma persists across these levels. Only a few studies examined differences by sex, and findings were mixed. Research to date has several limitations; for example, it disproportionately represents samples from the U.S. and White populations, and rarely examines differences by sexual or gender identity or other demographic characteristics. There is a need for additional research on the impact of equal marriage rights and same-sex marriage on the health and well-being of diverse sexual minorities across the globe.

Introduction

Legalization of same-sex marriage represents one important step toward advancing equal rights for sexual and gender minorities. Over the past two decades same-sex marriage has become legally recognized in multiple countries around the world. Between 2003 and mid-2015, same-sex couples in the United States (U.S.) gained the right to marry in 37 of 50 states. This right was extended to all 50 states in June 2015, when the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Obergefell v. Hodges that same-sex couples in all U.S. states had equal marriage rights. As of October 2019, same-sex couples had the right to marry in 30 countries and territories around the world [ 1 ].

National laws or policies that extend equal marriage rights to same-sex couples signal a reduction in structural stigma and have the potential to positively impact the health and well-being of sexual minorities. Structural stigma refers to norms and policies on societal, institutional and cultural levels that negatively impact the opportunities, access, and well-being of a particular group [ 2 ]. Forms of structural stigma that affect sexual minorities—such as restrictions on same-sex marriage—reflect and reinforce the social stigma against non-heterosexual people that occurs at individual, interpersonal, and community levels [ 3 ]. According to Hatzenbuehler and colleagues, structural stigma is an under-recognized contributor to health disparities among stigmatized populations [ 4 – 6 ], and reductions in structural stigma can improve health outcomes among sexual minorities [ 7 , 8 ].

Marriage is a fundamental institution across societies and access to the right to marry can reduce sexual-minority stigma by integrating sexual minority people more fully into society [ 9 ]. Same-sex marriage also provides access to a wide range of tangible benefits and social opportunities associated with marriage [ 9 , 10 ]. Despite the benefits of marriage rights, sexual minorities continue to experience stigma-related stressors, such as rejection from family or community, and discrimination in employment and other life spheres [ 11 ]. In addition, reactions to same-sex marriage appear to differ among sexual minorities and range from positive to ambivalent [ 11 – 13 ]. Extending marriage rights to same-sex couples remedies only one form of structural stigma. Although legalization of same-sex marriage represents a positive shift in the social and political landscape, the negative impact of social stigma may persist over time. For example, a recent Dutch study found that despite 20 years of equal marriage rights, sexual minority adolescents continue to show higher rates of substance use and lower levels of well-being than their heterosexual peers [ 14 ]. This study underscores the importance of understanding the complex impact of stigma at the structural, community, interpersonal, and individual levels.

Impact on sexual minority health

A growing body of literature, using different methods from diverse countries where same-sex marriage has been debated or adopted, provides important insights into the impact of equal marriage rights on the health and well-being of sexual minority individuals. Research to date has consistently found that legal recognition of same-sex marriage has a positive impact on health outcomes among sexual and gender minority populations [ 15 – 20 ]. Studies in the U.S. have found evidence of reduced psychological distress and improved self-reported health among sexual minorities living in states with equal marriage rights compared to those living in states without such rights [ 5 , 21 – 23 ]. One state-specific study also found improved health outcomes for sexual minority men after legalization of same-sex marriage [ 24 ]. Furthermore, sexual minorities living in states that adopted, or were voting on, legislation restricting marriage recognition to different-sex couples reported higher rates of alcohol use disorders and psychological distress compared to those living in states without such restrictions [ 5 , 25 – 31 ]. Consistent with research in the U.S., findings from research in Australia on marriage restriction voting, found that sexual minorities living in jurisdictions where a majority of residents voted in support of same-sex marriage reported better overall health, mental health, and life satisfaction than sexual minorities in locales that did not support same-sex marriage rights [ 32 ].

Although existing literature reviews have documented positive impacts of equal marriage rights on physical and mental health outcomes among sexual minority individuals [ 15 – 20 ], to our knowledge no reviews have conducted a nuanced exploration of the individual, interpersonal, and community impacts of legalized same-sex marriage. An emerging body of quantitative and qualitative literature affords a timely opportunity to examine a wide range of psychosocial impacts of equal marriage rights. Understanding these impacts is important to guide and interpret future research about the potential protective health effects of same-sex marriage.

Potential differences between SMW and SMM

Given the dearth of research focusing on the health and well-being of sexual minority women (SMW), especially compared to the sizable body of research on sexual minority men (SMM) [ 33 , 34 ], there is a need to explore whether the emerging literature on same-sex marriage provides insights about potential differences in psychosocial impacts between SMW and SMM. Recent research underscores the importance of considering SMW’s perspectives and experiences related to same-sex marriage. For example, gendered social norms play out differently for women and men in same-sex and different-sex marriages, and interpersonal dynamics and behaviors, including those related to coping with stress, are influenced by gender socialization [ 35 ]. However, there is little research about how societal-level gender norms and gendered social constructions of marriage may be reflected in SMW’s perceptions of same-sex marriage. Structural sexism (e.g., gendered power and resource inequality at societal and institutional levels) differentially impacts women’s and men’s health [ 36 ], and may also contribute to sex differences in experiences and impacts of same-sex marriage. For example, research from the U.S. suggests that same-sex marriage rights may improve health outcomes and access to healthcare for SMM, but evidence is less robust for SMW [ 37 – 39 ]. Differences in health outcomes appear to be at least partially explained by lower socioeconomic status (income, employment status, perceived financial strain) among SMW compared to SMM [ 40 ]. Further, other psychosocial factors may contribute to differential experiences of legalized same-sex marriage. For example, a study of older sexual minority adults in states with equal marriage rights found that married SMW experienced more LGBTQ (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer) microaggressions than single SMW, but no differences by relationship status were noted among SMM [ 41 ]. Mean number of microaggressions experienced by SMW in partnered unmarried relationships fell between, but were not significantly different from, that of married and single SMW.

Theoretical framework

Social-ecological and stigma theoretical perspectives were used as the framework for organizing literature in this review (See Fig 1 ). Stigma occurs and is experienced by sexual minorities at individual, interpersonal, and structural levels, which mirror the levels of focus within the social-ecological framework [ 6 , 42 ]. Consequently, changes such as extending equal marriage rights to same-sex couples may influence sexual minorities’ experiences of stigma across all of these levels [ 43 ]. Gaining access to the institution of marriage is distinct from marital status (or being married) and likely impacts sexual minority adults across individual, interpersonal, and community contexts [ 44 ], regardless of relationship status.

From a social-ecological perspective, individual and interpersonal processes can amplify or weaken the impact of structural level policies, such as equal marriage rights, on sexual minority individuals’ health and well-being [ 43 , 45 , 46 ]. For example, on an individual level, experiences and perceptions of equal marriage rights may influence stigma-related processes such as internalized heterosexism, comfort with disclosure, and centrality of sexual identity [ 47 ]. Interpersonal and community level interactions may trigger stigma-related processes such as prejudice concerns, vigilance, or mistrust. Such processes may in turn, influence the impact of social policy change on sexual minority stress and well-being [ 48 – 50 ].

The impact of equal marriage rights among sexual minority individuals may also be influenced by other social and political factors such as state- or regional-level social climate [ 50 – 52 ], or inconsistency among other policy protections against discrimination (e.g., in housing or public accommodations) [ 11 , 50 ]. Sociopolitical uncertainty may continue long after the right to marry is extended to same-sex couples [ 53 , 54 ]. Monk and Ogolsky [ 44 ] define political uncertainty as a state of “having doubts about legal recognition bestowed on individuals and families by outside systems; being unsure about social acceptance of marginalized relationships; being unsure about how ‘traditional’ social norms and roles pertain to marginalized relationships or how alternative scripts might unfold” (p. 2).

Current study

The overall aim of this scoping review was to identify and summarize existing literature on psychosocial impacts of equal marriage rights among sexual minority adults. Specific objectives were to: 1) identify and describe the psychosocial impacts of equal marriage rights on sexual minority adults; and 2) explore SMW-specific perceptions of equal marriage rights and whether psychosocial impacts differ for SMM and SMW.

Study design

We used a scoping review approach, as it is well-suited for aims designed to provide a descriptive overview of a large and diverse body of literature [ 55 ]. Scoping reviews have become a widely used approach for synthesizing research evidence, particularly in health-related fields [ 55 ]. Scoping reviews summarize the range of research, identify key characteristics or factors related to concepts, and identify knowledge gaps in particular areas of study [ 56 , 57 ]. By contrast, systematic reviews are more narrowly focused on creating a critically appraised synthesized answer to a particular question pertinent to clinical practice or policy making [ 57 ]. We aimed to characterize and summarize research related to psychosocial impacts of equal marriage rights and same-sex marriage, including potential gaps in research specific to SMW. Following Arksey and O’Malley [ 56 ], the review was conducted using the following steps: 1) identifying the research question, 2) identifying relevant studies, 3) selecting studies, 4) charting the data, and 5) collating, summarizing and reporting results. Because this is a scoping review, it was not registered with PROSPERO, an international registry for systematic reviews.

Selection method

The authors used standard procedures for conducting scoping reviews, including following PRISMA guidelines [ 58 ]. Articles that report findings from empirical studies with an explicit focus on the psychosocial impacts of equal marriage rights and same-sex marriage on sexual minority adults are included in this review. All database searches were limited to studies in English language journals published from 2000 through 2019 (our most recent search was executed in June 2020). This time frame reflects the two decades since laws regarding same-sex marriage began to change in various countries or jurisdictions within countries. Literature review articles and commentaries were excluded. To ensure that sources had been vetted for scientific quality by experts, only articles in peer-reviewed journals were included; books and research in the grey literature (e.g., theses, dissertations, and reports) were excluded. There was no restriction on study location. A librarian searched PubMed, PsycINFO, CINAHL (Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature), Web of Science, JSTOR, and Sociological Abstracts databases using combinations of key search terms. Following is an example of the search terms used in CINAHL database searches: ((TI "marriage recognition" OR AB "marriage recognition") OR (TI marriage OR AB marriage) OR (TI same-sex OR AB same-sex) OR (TI "same sex" OR AB "same sex")) AND ((TI LGBT OR AB LGBT) OR (TI gay OR AB gay) OR (TI lesbian OR AB lesbian) OR (TI bisexual OR AB bisexual) OR (TI transgender OR AB transgender) OR (TI Obergefell OR AB Obergefell) OR (TI "sexual minorities" OR AB "sexual minorities))

Articles were selected in two stages of review. In stage one, the first author and librarian independently screened titles and abstracts for inclusion or exclusion using eligibility criteria. We excluded articles focused solely on the impact of relationship status on health outcomes, satisfaction or dynamics within marriage relationships, or the process of getting married (e.g., choices of who to invite, type of ceremony), or other topics that did not pertain directly to the research aims. For example, a study about the impact of getting married that also included themes pertaining to the impact or meaning of equal marriage rights was included in the full review. The first author and a librarian met to review and resolve differences and, in cases where relevance was ambiguous, articles underwent a full-text review (in stage 2). Table 1 summarizes exclusion categories used in the title and abstract reviews.

In stage two, articles not excluded in stage one were retrieved for full-text review. Each article was independently reviewed by two authors to assess study relevance. Discrepancies related to inclusion were few (less than 10%) and resolved through discussion and consensus-building among the first four authors. This process resulted in an analytic sample of 59 articles (see Fig 2 ).

Table 2 provides an overview of characteristics of the studies included in this scoping review. Most were qualitative and most aggregated SMW and SMM in analyses. Only 14 studies explored differences in impact for SMW and SMM, or separately examined the specific perceptions and experiences of SMW. Although search terms were inclusive of transgender individuals, samples in the studies we reviewed rarely included or focused explicitly on experiences of transgender or gender nonbinary identified individuals. In studies that explicitly included transgender and nonbinary individuals, sample sizes were rarely large enough to permit examination of differences based on gender identity (e.g., survey samples with 2–3% representation of nonbinary or transgender individuals) [ 44 , 59 – 63 ]. Other studies recruiting sexual minorities may have included transgender and nonbinary individuals (who also identified as sexual minorities), but did not assess gender identity. Among studies in which participant race/ethnicity was reported, most included samples that were majority White.

* Not mutually exclusive, classifications do not equal 100%.

Studies of the impact of legalized marriage on physical health were not excluded in the original search parameters; however, physical health has been addressed in prior reviews [ 15 – 20 ]. Further, because our research questions focused on psychosocial factors, we excluded studies on physical health unless they also addressed individual, interpersonal, or community psychosocial impacts of same-sex marriage legalization. Studies that focused on physical health impacts or access to health insurance were used only in the introduction.

Civil union was not explicitly included as a search parameter, but articles focusing on civil unions were captured in our search. Although civil unions are not equivalent to marriage, they often confer similar substantive legal rights. We included articles about civil union that explicitly pertained to our research question, such as a study that examined perceived stigma and discrimination before and after implementation of civil union legislation in one U.S. state [ 64 ], and excluded articles that did not (e.g., a study of relationship quality or longevity among same-sex couples in civil unions) [ 65 ].

A majority of the studies were conducted in the U.S. Of the 43 U.S. studies, 20 sampled from a single state, 10 included participants from multiple states, 12 used a national sample, and one had no human subjects (secondary analysis of legal cases). Of those sampling a single state, all focused on the impact of changes (or proposed changes) in same-sex marriage policy: 10 focused on Massachusetts (the first state in the U.S. to legalize same-sex marriage), two focused on Iowa, two on Vermont, and two on California. One article each included study participants from Nebraska, Oregon, Illinois, and a small (unnamed) non-metropolitan town in the Midwest.

Analysis method

We created a data extraction form to ensure consistency across team members in extracting key study information and characteristics including study design (e.g., quantitative, qualitative, or mixed method), location (e.g., country and/or region), sample (e.g., whether the study included or excluded SMW or SMM, assessed and reported race/ethnicity), and key results. Articles were also classified based on findings related to level of impact (e.g., individual, couple, family, community, or broader social attitudes toward LGBTQ+ individuals; see S1 Table ). A final category on significance/implications allowed reviewers to further identify and comment on major themes and relevance to the current review. Themes were then identified and organized using stigma and social-ecological frameworks.

Aim 1: Psychosocial impacts of same-sex marriage rights

Individual level impacts.

Although most studies about the impact of equal marriage rights have been conducted with couples or individuals in committed or married relationships, 15 studies in this review included sexual minority adults across relationship statuses. In general, studies examining the impact of equal marriage rights among sexual minorities suggest that equal access to marriage has a positive impact on perceptions of social acceptance and social inclusion regardless of relationship status [ 47 , 63 , 66 , 67 ]. For example, Riggle and colleagues [ 47 ] examined perceptions of sexual minority individuals in the U.S. during the period in which same-sex couples had equal marriage rights in some, but not all, U.S. states. Sexual minorities who resided in states with equal marriage rights reported less identity concealment, vigilance, and isolation than their peers in states without equal marriage rights. Similarly, using data from the longitudinal Nurses’ Health Study in the U.S., Charlton and colleagues [ 68 ] examined potential positive impacts of equal marriage rights on sexual identity disclosure. They found that participants living in states with any form of legal recognition of same-sex relationships (inclusive of marriage, civil unions, or domestic partnerships) were 30% more likely than those is states without legal recognition to consistently disclose a sexual minority identity across survey waves [ 68 ].

Researchers have documented ambivalence among sexual minority adults regarding the institution of marriage and whether same-sex marriage would impact other forms of structural or interpersonal stigma. Sexual minority participants in several studies expressed concern about continued interpersonal stigma based on sexual or gender identity, the limitations of marriage as a vehicle for providing benefits and protections for economically marginalized LGBTQ+ individuals, and the possibility that an increased focus on marriage would contribute to devaluing unmarried same-sex relationships [ 12 , 13 , 62 , 69 , 70 ]. Studies also documented concerns about marriage being inherently linked to heteronormative expectations and about assimilation to heterosexist cultural norms [ 60 , 69 , 71 ]. These concerns were summarized by Hull [ 69 ]: “The fact that LGBTQ respondents favor marriage more in principle (as a right) than in practice (as an actual social institution) suggests that marriage holds multiple meanings for them” (p. 1360).

Five studies explicitly examined racial/ethnic minority identities as a factor in individuals’ perceptions of same-sex marriage; one qualitative study focused exclusively on Black individuals in the U.S. [ 72 ] and the other four examined differences by race/ethnicity [ 64 , 66 , 67 , 73 ]. McGuffy [ 72 ] conducted in-depth interviews with 102 Black LGBT individuals about their perceptions of marriage as a civil rights issue before and after same-sex marriage was recognized nationally in the U.S. The study found that intersecting identities and experiences of discrimination related to racism, homophobia, and transphobia influenced personal views of marriage. For example, although most participants were supportive of equal marriage rights as a public good, many felt that the emphasis on marriage in social movement efforts overlooked other important issues, such as racism, economic injustice, and transgender marginalization.

The four other studies examining racial/ethnic differences in perceptions about whether equal marriage rights facilitated inclusion or reduced interpersonal stigma yielded mixed results. One found that residing in states with equal marriage rights was associated with greater feelings of acceptance among sexual minorities; however, White sexual minorities reported greater feelings of inclusion than participants of color [ 66 ]. By contrast, in a quasi-experiment in which SMW in a midwestern state were interviewed pre- or post- passage of civil union legislation, those interviewed after the legislation reported lower levels of stigma consciousness and perceived discrimination than those interviewed before the legislation; however, effects were stronger among SMW of color than among White SMW [ 64 ]. In a study of unmarried men in same-sex male couples, Hispanic/Latino men were more likely than non-Latino White participants to report perceived gains in social inclusion after equal marriage rights were extended to all U.S. states [ 67 ]. However, men who reported higher levels of minority stress (enacted and anticipated stigma as well as internalized homophobia) were less likely to show improvement in perceptions of social inclusion. Lee [ 73 ], using data from a national Social Justice Sexuality Project survey, found no statistical differences in Black, White and Latinx sexual minorities’ perceptions that equal marriage rights for same-sex couples had a moderate to major impact on their lives. In analyses restricted to Black participants, individuals with higher level of sexual minority identity salience reported significantly higher importance of equal marriage rights. Lee suggests that same-sex marriage was perceived by many study participants as a tool to gain greater acceptance in the Black community because being married is a valued social status.

Couple level impacts

We identified 15 studies that focused on couples as the unit of analysis. Findings from studies of the extension of equal marriage rights in U.S. states suggest positive impacts among same-sex couples, including access to financial and legal benefits as well as interpersonal validation, such as perceptions of being viewed as a “real” couple and increased social inclusion [ 12 , 59 , 63 , 74 , 75 ]. Furthermore, couples in several studies described the potential positive impacts of legal recognition of their relationship on their ability to make joint decisions about life issues, such as having children and medical care [ 75 ]. Couples also described having a greater sense of security associated with financial (e.g., taxes, healthcare) and legal (e.g., hospital visitation) benefits and reduced stress in areas such as travel and immigration [ 75 ]. Collectively, these findings suggest that marriage rights were perceived to imbue individuals in same-sex relationships with a sense of greater security, stability, and safety due to the legal recognition and social legitimization of same-sex couples. Although equal marriage rights were perceived as an important milestone in obtaining civil rights and reducing institutional discrimination, concerns about and experiences of interpersonal stigma persisted [ 76 – 78 ]. The social context of legal same-sex marriage may create stress for couples who elect to not marry. For example, in a study of 27 committed, unmarried same-sex couples interviewed after the U.S. Supreme Court decision on Obergefell, couples who chose not to marry described feeling that their relationships were less supported and perceived as less committed [ 79 ].

Reports from the CUPPLES study, a national longitudinal study of same-sex couples in the U.S. from 2001 to 2014, provided a unique opportunity to examine the impact of different forms of legal recognition of same-sex relationships. In wave three of the study during 2013–2014, open-ended qualitative questions were added to explore how individuals in long-term committed partnerships perceived the extension of equal marriage rights in many U.S. states. Themes included awe about the historic achievement of a long-awaited civil rights goal, celebration and elation, and affirmation of minority sexual identity and relationships, but also fears of backlash against sexual minority rights [ 80 ]. Some individuals who divorced after institutionalization of the right to same-sex marriage reported shame, guilt, and disappointment—given that they and others had fought so hard for equal marriage rights [ 81 ].

Studies outside the U.S. have also found evidence of positive impacts of legal recognition of same-sex couple relationships (e.g., increased social recognition and social support), as well as potential concerns [ 82 – 86 ]. For example, in a study of couples from the first cohort of same-sex couples to legally marry in Canada, participants described marriage as providing them with language to describe their partner that was more socially understood and helping to decrease homophobic attitudes among the people around them [ 83 ]. Some couples said they could fully participate in society and that marriage normalized their lives and allowed them to “live more publicly.” Couples also discussed the safety, security, and increased commitment that came from marriage, and some felt that marriage opened up previously unavailable or unimagined opportunities, such as becoming parents. However, some participants noted that their marriage caused disjuncture in relationships with their family of origin, as marriage made the relationship feel too real to family members and made their sexual identities more publicly visible.

Family level impacts

Seventeen studies examined the impact of equal marriage rights on sexual minority individuals’ or couples’ relationships with their families of origin. Although these studies predominately used cross-sectional survey designs, one longitudinal study included individuals in both different-sex and same-sex relationships before and after the U.S. Supreme Court decision that extended marriage rights to all states [ 44 ]. This study found that support from family members increased following national legalization of same-sex marriage [ 44 ]. A cross-sectional online survey of 556 individuals with same-sex partners in Massachusetts (the first U.S. state to extend equal marriage rights to same-sex couples), found that greater family support and acceptance of same-sex couples who married was associated with a stronger overall sense of social acceptance [ 66 ].

Other cross-sectional surveys found mixed perceptions of family support and feelings of social acceptance. For example, a study of 357 participants in long-term same-sex relationships found that perceived social support from family did not vary by state-level marriage rights or marital status [ 47 ]. However, living in a state with same-sex marriage rights was associated with feeling less isolated. The finding of no differences in perceived support might be partly explained by the fact that the sample included only couples in long-term relationships; older, long-term couples may rely less on support from their family of origin than younger couples [ 12 ].

In studies (n = 6) that included dyadic interviews with same-sex married couples [ 74 , 79 , 85 , 87 – 89 ], participants described a wide range of family members’ reactions to their marriage. These reactions, which emerged after same-sex marriage legalization, were typically described by couples as profoundly impactful. Couples who perceived increased family support and acceptance described these changes as triumphant [ 85 ], transformative [ 88 ], and validating [ 74 , 87 ]. Conversely, some same-sex couples reported feeling hurt and betrayed when familial reactions were negative or when reactions among family members were divided [ 85 , 87 , 89 ]. Findings from these and other studies suggest that if certain family members were accepting or rejecting prior to marriage, they tended to remain so after equal marriage rights and/or the couple’s marriage [ 61 , 74 , 90 , 91 ]. In some cases, family members were perceived as tolerating the same-sex relationship but disapproving of same-sex marriage [ 85 , 90 ].

Findings from studies of married sexual minority people suggest that family (especially parental) disapproval was a challenge in the decision to get married [ 92 ], possibly because disclosure of marriage plans by same-sex couples frequently disrupted family “privacy rules” and long-time patterns of sexual identity concealment within families or social networks [ 87 ]. In a few studies, same-sex partners perceived that their marriage gave their relationship more legitimacy in the eyes of some family members, leading to increased support and inclusion [ 61 , 66 , 89 – 91 ]. Further, findings from two studies suggested that participating in same-sex weddings gave family members the opportunity to demonstrate support and solidarity [ 87 , 93 ].

Two qualitative studies collected data from family members of same-sex couples. In one, heterosexual siblings (all of whom were in different-sex marriages) described a range of reactions to marriage equality—from support for equal marriage rights to disapproval [ 80 ]. The other study interviewed sexual minority migrants to sexual minority friendly countries in Europe who were married and/or raising children with a same-sex partner, and these migrant’s parents who lived in Central and Eastern European countries that prohibited same-sex marriage. Parents found it difficult to accept their adult child’s same-sex marriage, but the presence of grandchildren helped to facilitate acceptance [ 94 ].

Community level impacts

Twelve studies in this review examined the community-level impacts of same-sex marriage. These studies focused on community level impacts from two perspectives: impacts of equal marriage rights on LGBTQ+ communities, and the impacts of equal marriage rights on LGBTQ+ individuals’ interactions with their local communities or extended social networks.

LGBTQ+ communities . A prominent theme among these studies was that marriage is beneficial to LGBTQ+ communities because it provides greater protection, recognition, and acceptance of sexual minorities, their families, and their relationships—even beyond the immediate impact on any individual and their relationship or marriage [ 12 , 62 , 89 , 95 ]. Despite these perceived benefits, studies have found that some sexual minority adults view marriage as potentially harmful to LGBTQ+ communities because of concerns about increased assimilation and mainstreaming of LGBTQ+ identities [ 12 , 50 , 62 ], stigmatizing unmarried relationships [ 62 ], and weakening of unique and valued strengths of LGBTQ+ culture [ 12 ]. For example, Bernstein, Harvey, and Naples [ 96 ] interviewed 52 Australian LGBTQ+ activists and legislators who worked alongside activists for equal marriage rights. These authors described the “assimilationist dilemma” faced by activists: a concern that gaining acceptance into the mainstream societal institution of marriage would lessen the salience of LGBTQ+ identity and ultimately diminish the richness and strength of LGBTQ+ communities. Another downside of the focus on marriage as a social movement goal was the concern about reinforcing negative heteronormative aspects of marriage rather than challenging them [ 95 ].

Four studies explicitly examined possible community level impacts of same-sex marriage. In a mixed-methods study with 115 LGBTQ+ individuals in Massachusetts, participants reported believing that increased acceptance and social inclusion as a result of equal marriage rights might lessen reliance on LGBTQ+-specific activism, events, activities, and venues for social support [ 13 ]. However, a majority of study participants (60%) reported participating in LGBTQ+-specific events, activities, or venues “regularly.” A few studies found evidence of concerns that the right to marry could result in marriage being more valued than other relationship configurations [ 12 , 62 , 79 ].

Local community contexts and extended social networks . Studies examining the impact of same-sex marriage on sexual minority individuals’ interactions with their extended social networks and in local community contexts yielded mixed results. In an interview study with 19 same-sex couples living in the Netherlands, Badgett [ 66 ] found that LGBTQ+ people experienced both direct and indirect increases in social inclusion in their communities and extended social networks as a result of equal marriage rights. For example, direct increases in social inclusion included people making supportive comments to the couple and attending their marriage ceremonies; examples of indirect increases included same-sex spouses being incorporated into family networks [ 66 ]. Other studies found mixed or no change in support for LGBTQ+ people and their relationships. Kennedy, Dalla, and Dreesman [ 61 ] collected survey data from 210 married LGBTQ+ individuals in midwestern U.S. states, half of whom were living in states with equal marriage rights at the time of data collection. Most participants did not perceive any change in support from their community/social network following legalization of same-sex marriage; other participants reported an increase or mixed support from friends and co-workers. Similarly, Wootton and colleagues interviewed 20 SMW from 15 U.S. states and found positive, neutral, and negative impacts of same-sex marriage on their interactions in work and community contexts [ 50 ]. Participants perceived increased positivity about LGBTQ+ issues and more accepting attitudes within their extended social networks and local communities, but also reported hearing negative comments about sexual minority people more frequently and experiencing continued sexual orientation-based discrimination and stigma [ 50 ]. Many SMW reported feeling safer and having more positive conversations after Obergefell, but also continued to have concerns about being out at work as a sexual minority person [ 50 ].

Two studies examined the experiences of LGBTQ+ people in U.S. states in which same-sex marriage restrictions were decided by voters through ballot measures. These studies documented mixed impacts on participants’ interactions with extended social networks and community. Maisel and Fingerhut [ 28 ] surveyed 354 sexual minority adults in California immediately before the vote to restrict recognition of marriage to one man and one woman in the state (Proposition 8) and found that about one-third experienced interactions with social network members that were positive, whereas just under one-third were negative, and the rest were either mixed or neutral. Overall, sexual minority people reported more support than conflict with extended social network members and heterosexual community members over the ballot measure, with friends providing the most support [ 28 ]. Social support and solidarity from extended social network members in the face of ballot measures to restrict marriage recognition were also reported in an interview study of 57 same-sex couples residing in one of seven U.S. states that had passed marriage restriction amendments in 2006 [ 97 ]. However, some LGBTQ+ people also experienced condemnation and avoidance in their extended social networks [ 97 ].

Societal level impacts

Sixteen studies examined ways that same-sex marriage influenced societal attitudes about sexual minority individuals or contributed to additional shifts in policies protecting the rights of sexual minority individuals. Findings suggested that the right of same-sex couples to marry had a positive influence on the political and socio-cultural context of sexual minorities’ lives. For example, changes in laws may influence social attitudes or result in LGBTQ positive policy diffusion across states (jurisdictions). There is debate over whether legal changes, such as equal marriage rights, create or are simply reflective of changes in social attitudes toward a group or a social issue [ 98 ]. Flores and Barclay [ 98 ] theorize four different socio-political responses to changes in marriage laws: backlash, legitimacy, polarization, and consensus. Some scholars argue that changes in law are unlikely to impact social attitudes (consensus), while others argue that legal changes influence the political and social environment that shapes social attitudes. Possible effects range from decreased support for sexual minorities and attempts to rescind rights (backlash) to greater support for the rights of sexual minorities and possible future expansion of rights and protections (legitimacy).

Findings from research generally suggest a positive relationship between same-sex marriage and public support for the overall rights of sexual minorities (legitimacy), and mixed results related to changes in mass attitudes (consensus) [ 98 – 106 ]. For example, in a panel study in Iowa before and after a state Supreme Court ruling in favor of equal marriage rights, Kreitzer and colleagues found that the change in law modified registered voters’ views of the legitimacy of same-sex marriage and that some respondents felt “pressure” to modify or increase their expressed support [ 102 ]. Similarly, Flores and Barclay [ 98 ] found that people in a state with equal marriage rights showed a greater reduction in anti-gay attitudes than people in a state without equal marriage rights. Studies based on data from European countries also found that more positive attitudes toward sexual minorities were associated with equal marriage rights; improvements in attitudes were not evident in countries without equal marriage rights [ 9 , 105 , 106 ].

There is some evidence to support the third possible socio-political response to changes in marriage laws in Flores and Barclay’s model: increased polarization of the general public’s attitudes toward sexual minorities. Perrin, Smith, and colleagues [ 107 ], using successive-independent samples study of conservatives, moderates, and progressives across the U.S. found no overall changes in opinions attitudes about sexual minorities immediately after the Supreme Court decision extending equal marriage rights to all same-sex couples in the U.S. However, analyses by subgroup found that those who were conservative expressed more prejudice toward gay men and lesbians, less support for same-sex marriage, and less support for LGB civil rights immediately after the decision. Similarly, drawing on data from approximately one million respondents in the U.S. who completed implicit and explicit measures of bias against gay men and lesbian women (Project Implicit), Ofosu and colleagues [ 100 ] found that implicit bias decreased sharply following Obergefell. However, changes in attitudes were moderated by state laws; respondents in states that already had equal marriage rights for same-sex couples demonstrated decreased bias whereas respondents in states that did not yet have equal marriage rights evidenced increased bias [ 100 ]. Using data from the World Values Survey (1989–2014) in European countries, Redman [ 103 ] found that equal marriage rights were associated with increases in positive opinions about sexual minorities, but that the increase was driven largely by those who already held positive views.

Little support has been found for the hypothesis that the extension of equal marriage rights would be followed by a backlash of sharp negative shifts in mass attitudes and public policy [ 98 , 108 , 109 ]. For example, a general population survey in one relatively conservative U.S. state (Nebraska) found public support for same-sex marriage was higher after the Supreme Court ruling than before, suggesting no backlash in public opinion [ 108 ]. Similarly, Bishin and colleagues [ 109 ], using both an online survey experiment and analysis of data from a U.S. public opinion poll (National Annenberg Election Studies) before and after three relevant policy events, found little change in public opinion in response to simulated or actual policy changes.

Although equal marriage rights confer parental recognition rights, there are still legal challenges and disparate rulings and interpretations about some family law issues [ 77 , 110 , 111 ]. For example, some states in the U.S. have treated the parental rights of same-sex couples differently than those of different-sex (presumed heterosexual) couples. Both members of a same-sex couple have traditionally not been automatically recognized as parents of a child born or adopted within the relationship. However, the presumptions of parenthood after same-sex marriage was legalized have forced states to treat both members of same-sex couples as parents irrespective of method of conception or adoption status [ 112 ]. Still, results from a cross-national study of laws, policies, and legal recognition of same-sex relationships suggests that parental rights are recognized in some jurisdictions but not others [ 111 ].

Aim 2: SMW-specific findings and differences by gender

A total of 13 studies included in this review conducted SMW-specific analyses or compared SMW and SMM’s perceptions and experiences of same-sex marriage and equal marriage rights. In studies that included only SMW [ 50 , 64 , 68 , 77 , 81 , 86 , 89 , 91 ], findings emphasized the importance of relational and interpersonal impacts of same-sex marriage. Examples include creating safety for sexual identity disclosure and visibility [ 68 , 81 ], providing legal protections in relation to partners and/or children [ 77 , 81 ], offering social validation [ 86 , 89 ], and reducing stigma in larger community contexts [ 50 , 64 ]. Relational themes centered on concerns and distress when experiencing rejection or absence of support from family members or extended social networks [ 50 , 81 , 86 , 89 , 91 ].