- USF Research

- USF Libraries

Digital Commons @ USF > Theses and Dissertations

Physical Education and Exercise Science Theses and Dissertations

Theses/dissertations from 2021 2021.

Warming Up and Cooling Down: Perceptions and Behaviors Associated with Aerobic Exercise , Balea J. Schumacher

Theses/Dissertations from 2020 2020

An Examination of Changes in Muscle Thickness, Isometric Strength, and Body Water Throughout the Menstrual Cycle , Tayla E. Kuehne

Theses/Dissertations from 2019 2019

Psychological Responses to High-Intensity Interval Training Exercise: A Comparison of Ungraded Running and Graded Walking , Abby Fleming

Theses/Dissertations from 2018 2018

The Effects of Music Choice on Perceptual and Physiological Responses to Treadmill Exercise , Taylor A. Shimshock

Theses/Dissertations from 2016 2016

The Effect of Exercise Order on Body Fat Loss During Concurrent Training , Tonya Lee Davis-Miller

Anti-Fat Attitudes and Weight Bias Internalization: An Investigation of How BMI Impacts Perceptions, Opinions and Attitudes , Laurie Schrider

Theses/Dissertations from 2014 2014

The Effect of Music Cadence on Step Frequency in the Recreational Runner , Micaela A. Galosky

The Hypertrophic Effects of Practical Vascular Blood Flow Restriction Training , John Francis O'halloran

Theses/Dissertations from 2013 2013

The Effects of Exercise Modality on State Body Image , Elizabeth Anne Hubbard

Perceptual Responses to High-Intensity Interval Training in Overweight and Sedentary Individuals , Nicholas Martinez

Comparisons of acute neuromuscular fatigue and recovery after maximal effort strength training using powerlifts , Nicholas Todd Theilen

Theses/Dissertations from 2012 2012

The Impact of Continuous and Discontinuous Cycle Exercise on Affect: An Examination of the Dual-Mode Model , Sam Greeley

Systematic review of core muscle electromyographic activity during physical fitness exercises , Jason Martuscello

Theses/Dissertations from 2011 2011

The Effect of Unexpected Exercise Duration on Rating of Perceived Exertion in an Untrained, Sedentary Population , Lisa M. Giblin

The Effect of Various Carbohydrate Supplements on Postprandial Blood Glucose Response in Female Soccer Players , Nina Pannoni

Middle School Physical Education Programs: A Comparison of Moderate to Vigorous Physical Activity in Sports Game Play , Marcia Ann Patience

The Effects of Pre-Exercise Carbohydrate Supplementation on Resistance Training Performance During an Acute Resistance Training Session , Kelly Raposo

Theses/Dissertations from 2010 2010

Effects of Fat-Free and 2% Chocolate Milk on Strength and Body Composition Following Resistance Training , Ashley T. Forsyth

Relationship Between Muscular Strength Testing to Dynamic Muscular Performance in Division One American Football Players , Johnathan Fuentes

Effects of Ingesting Fat Free and Low Fat Chocolate Milk After Resistance Training on Exercise Performance , Breanna Myers

Theses/Dissertations from 2009 2009

Effects of a Commercially Available Energy Drink on Anaerobic Performance , Jason J. Downing

The Impact of Wearable Weights on the Cardiovascular and Metabolic Responses to Treadmill Walking , Kristine M. Fallon

Six Fifth Grade Students Experiences Participating in Active Gaming during Physical Eduction Classes , Lisa Witherspoon Hansen

The impact of wearable weights on perceptual responses to treadmill walking , Ashley T. Kuczynski

The Preference of Protein Powders Among Adult Males and Females: A Protein Powder Taste Study , Joshua Manter

Caloric Expenditure and Substrate Utilization in Underwater Treadmill Running Versus Land-Based Treadmill Running , Courtney Schaal

Theses/Dissertations from 2008 2008

A Survey of NCAA Division 1 Strength and Conditioning Coaches- Characteristics and Opinions , Jeremy Powers

Theses/Dissertations from 2007 2007

Perceptions of group exercise participants based on body type, appearance and attractiveness of the instructor , Jennifer Mears

Theses/Dissertations from 2006 2006

Be active! An examination of social support's role in individual vs. team competition in worksite health promotion , Lauren Kriz

Advanced Search

- Email Notifications and RSS

- All Collections

- USF Faculty Publications

- Open Access Journals

- Conferences and Events

- Theses and Dissertations

- Textbooks Collection

Useful Links

- Rights Information

- SelectedWorks

- Submit Research

Home | About | Help | My Account | Accessibility Statement | Language and Diversity Statements

Privacy Copyright

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Int J Environ Res Public Health

Effects of a Physical Education Program on Physical Activity and Emotional Well-Being among Primary School Children

Irina kliziene.

1 Educational Research Group, Institute of Social Science and Humanity, Kaunas University of Technology, Kaunas 44249, Lithuania

Ginas Cizauskas

2 Department of Mechanical Engineering, Faculty of Mechanical Engineering and Design, Kaunas University of Technology, Kaunas 51424, Lithuania; [email protected]

Saule Sipaviciene

3 Department of Applied Biology and Rehabilitation, Lithuanian Sports University, Kaunas 44221, Lithuania; [email protected]

Roma Aleksandraviciene

4 Department of Coaching Science, Lithuanian Sports University, Kaunas 44221, Lithuania or moc.liamg@ednargallenamor (R.A.); [email protected] (K.Z.)

5 Sports Centre, Vytautas Magnus University, Kaunas 51211, Lithuania

Kristina Zaicenkoviene

Associated data.

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

(1) Background: It has been identified that schools that adopt at least two hours a week of physical education and plan specific contents and activities can achieve development goals related to physical level, such as promoting health, well-being, and healthy lifestyles, on a personal level, including bodily awareness and confidence in physical skills, as well as a general sense of well-being, greater security and self-esteem, sense of responsibility, patience, courage, and mental balance. The purpose of this study was to establish the effect of physical education programs on the physical activity and emotional well-being of primary school children. (2) Methods: The experimental group comprised 45 girls and 44 boys aged 6–7 years (First Grade) and 48 girls and 46 boys aged 8–9 years (Second Grade), while the control group comprised 43 girls and 46 boys aged 6–7 years (First Grade) and 47 girls and 45 boys aged 8–9 years (Second Grade). All children attended the same school. The Children’s Physical Activity Questionnaire was used, which is based on the Children’s Leisure Activities Study Survey questionnaire, which includes activities specific to young children (e.g., “playing in a playhouse”). Emotional well-being status was explored by estimating three main dimensions: somatic anxiety, personality anxiety, and social anxiety. The Revised Children’s Manifest Anxiety Scale (RCMAS) was used. (3) Results: When analysing the pre-test results of physical activity of the 6–7- and 8–9-year-old children, it turned out that both the First Grade (92.15 MET, min/week) and Second Grade (97.50 MET, min/week) participants in the experimental group were physically active during physical education lessons. When exploring the results of somatic anxiety in EG (4.95 ± 1.10 points), both before and after the experiment, we established that somatic anxiety in EG was 4.55 ± 1.00 points after the intervention program, demonstrating lower levels of depression, seclusion, somatic complaints, aggression, and delinquent behaviours (F = 4.785, p < 0.05, P = 0.540). (4) Conclusions: We established that the properly constructed and purposefully applied eight-month physical education program had positive effects on the physical activity and emotional well-being of primary school children (6–7 and 8–9 years) in three main dimensions: somatic anxiety, personality anxiety, and social anxiety. Our findings suggest that the eight-month physical education program intervention was effective at increasing levels of physical activity. Changes in these activities may require more intensive behavioural interventions with children or upstream interventions at the family and societal levels, as well as at the school environment level. These findings have relevance for researchers, policy makers, public health practitioners, and doctors who are involved in health promotion, policy making, and commissioning services.

1. Introduction

Teaching in physical education has evolved rapidly over the last 50 years, with a spectrum of teaching styles [ 1 ], teaching models [ 2 ], curricular models [ 3 ], instruction models [ 4 ], current pedagogical models [ 5 , 6 ], and physical educational programs [ 7 ]. As schools provide benefits other than academic and conceptual skills at present, we can determine new ways to meet different goals through a variety of methodologies assessing contents from a multidisciplinary perspective. Education regarding these skills should also be engaged following a non-traditional methodology in order to overcome the lack of resources in traditional approaches and for teachers to meet their required goals [ 8 ].

Schools are considered an important setting to influence the physical activity of children, given the amount of time spent at school and the potential for schools to reach large numbers of children. Schools may be a barrier for interventions to promote physical activity (PA). Children are required to sit quietly for the majority of the day in order to receive academic lessons. A typical school day is represented by approximately 6 h, which may be extended by 30 min or longer if the child is provided motorized transportation and does not actively commute to and from school. Donnelly et al. [ 9 ] found that teachers who modelled PA by active participation in physical activity across the curriculum (i.e., promoted 90 min/week of moderate to vigorous physically active academic lessons; 3.0 to 6.0 METs, ∼10 min each) had greater SOFIT (a Likert scale from one to five, anchored with lying down for one and very active for five) scores shown by their students, compared to primary students with teachers using a lower level of modelling. Some studies have proposed the use of prediction models of METs for children, including accelerometer data. In such models, the slope and intercept of ambulatory activities (e.g., walking and running) differ from those of non-ambulatory activities, such as ball-tossing, aerobic dance, and playing with blocks [ 10 , 11 ]. Wood and Hall [ 12 ] found that children aged 8–9 years engaged in significantly higher moderate to vigorous physical activities during team games (e.g., football), compared to movement activities in PE lessons (e.g., dance).

It has been identified that schools which adopt two hours a week of PE and plan specific contents and activities to achieve development goals at the physical level can promote health, well-being, and healthy lifestyles on a personal level, including bodily awareness and confidence in one’s physical skills, as well as a general sense of well-being, greater security and self-esteem, sense of responsibility, patience, courage, and mental balance at the social level, including integration within society, a sense of solidarity, social interactions, team spirit, fair play, and respect for rules and for others, as well as wider human and environmental values [ 13 , 14 ]. Physical activity programs have been identified as potential strategies for improving social and emotional well-being in at-risk youth [ 15 ]. Emotional well-being permeates all aspects of the experience of children and has emerged as an essential element of mental health and reduction of anxiety, as well as a core component of health in general. Schools have a strong effect on children’s emotional development, and as they are an ideal environment to foster children’s emotional learning and well-being, failing to optimize the opportunity to do so could impact communities in negative ways [ 16 , 17 ]. Physical activity and exercise have positive effects on mood and anxiety, and a great number of studies have described the associations between physical activity and general well-being, mood, and anxiety [ 18 ]. Physical inactivity may also be associated with the development of mental disorders: some clinical and epidemiological studies have shown associations between physical activity and symptoms of depression and anxiety in cross-sectional and prospective longitudinal studies [ 19 ]. Low physical activity levels have also been associated with an increased prevalence of anxiety [ 20 ]. Levels of physical activity lower than those recommended by the World Health Organization are classified as a lack of physical activity or physical inactivity. Current guidelines on physical activity for children and adolescents aged 5–17 years generally recommend at least 60 min daily of moderate- to vigorous-intensity physical activities [ 21 ].

Therefore, we formulated the following research hypothesis: The application of a physical education program can have a positive impact on the physical activity and emotional well-being among primary school students.

The purpose of this study was to establish the effect of a physical education program on the physical activity and emotional well-being of primary school children.

Novelty of the work: For the first time, PE curriculum has been developed for second grade children, a new approach to physical education methodology. For the first time, anxiety is measured between first and second grades. Physical education has been a part of school curriculums for many years, but, due to childhood obesity, focus has increased on the role that schools play in physical activity and monitoring physical fitness [ 22 , 23 ].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. participants.

The schools utilized in this study were randomly chosen from primary schools in Lithuania. Four schools were chosen from different areas of Lithuania, which are typical of the Lithuanian education system (i.e., the state system), exercising in accordance with the description of primary, basic, and secondary education programs approved by the Lithuanian Minister of Education and Science in 2015. It ought to be noted that these schools structured classes without applying selection criteria; accordingly, it very well may be said that the students in the randomly chosen classes were additionally randomly allocated to the experimental and control groups. A non-probabilistic accurate sample was utilized in the study, where subjects were incorporated relying upon the objectives of the study.

The time and place of the study, with the consent of the guardians, were settled upon ahead of time with the school administration. This study was approved by the research ethics committee of the Kaunas University of Technology, Institute of Social Science and Humanity (Protocol No V19-1253-03).

The experimental group included 45 young women and 44 young men aged 6–7 years (First Grade) and 48 young women and 46 young men aged 8–9 years (Second Grade). The control group included 43 young women and 46 young men aged 6–7 (First Grade) and 47 young women and 45 young men aged 8–9 years (Second Grade). All children went to a same school.

2.2. Instruments

2.2.1. the evaluation of physical activity.

The Children’s Physical Activity Questionnaire [ 24 ] was utilized, which is based on the Children’s Leisure Activities Study Survey (CLASS) questionnaire, which includes activities explicit to small children, such as “playing in a playhouse.” The original intent of the proxy-reported CLASS questionnaire for 6–9 year olds was to evaluate the type, recurrence, and intensity of physical activity over a standard week [ 24 ].

2.2.2. The Revised Children’s Manifest Anxiety Scale

Enthusiastic well-being status was investigated by estimating three principal dimensions: somatic anxiety, personality anxiety, and social anxiety. The Revised Children’s Manifest Anxiety Scale (RCMAS) contains 37 items with 28 items used to measure anxiety and an additional 9 items that present an index of the child’s level of defensiveness. We were only concerned with the factor analysis of anxiety; along these lines, only those 28 items used to gauge anxiety were utilized. The RCMAS comprises three factors: (1) somatic anxiety, consisting of 12 items; (2) personality anxiety, consisting of 8 items; and (3) social anxiety, consisting of 8 items [ 25 ].

The outcomes were estimated as follows: (1) physical anxiety (more than or equal to 6.0 points—high somatic level, from 5.9 to 4.5 points—typical somatic level, and from 4.4 to 1.0 points—low somatic level); (2) personality anxiety (from 2.0 to 2.5 points—low personality anxiety level, from 2.6 to 3.5 points—typical personality anxiety level, and from 3.6 to 4.5 points—high personality anxiety level); and (3) social anxiety (more than or equal to 5.5 points—high social anxiety level, from 5.4 to 4.5 points—typical social anxiety level, and from 4.4 to 3.3 points—low social anxiety level). The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for the subscales ranged from 0.72 to 0.73.

2.3. Procedure

In this study, a pre-/mid-/post-test experimental methodology was utilized, in order to avoid any interruption of educational activities, due to the random selection of children in each group. The experimental group (First and Second Grades) was trialled for eight months. The technique for the physical education program was developed, and a model of educational factors that encourage physical activity for children was constructed.

Likewise, the methodical material for the physical education program [ 7 , 24 ] was prepared. The methodology depended on the dynamic exercise, intense motor skills repetition, differentiation, seating and parking reduction, and the physical activity distribution in the classroom (DIDSFA) model [ 26 , 27 ] ( Table 1 ).

Dynamic exercise, intense motor skills reiteration, differentiation, seating and parking reduction, and physical activity distribution in the classroom (DIDSFA) model—expanding dynamic learning time in primary physical education.

A physical education program was designed in order to advance physical activity to a significant degree, show development skills, and be agreeable. The suggested recurrence of physical education classes was three days out of the week. A typical DIDSFA First Grade model exercise lasted 30 min and had three sections: health fitness activities (10 min), ability fitness activities (15 min), and unwinding, focus, and reflection (5 min). The Second Grade model exercise lasted 45 min and comprised four sections: health fitness activities (20 min), ability fitness activities (20 min), and unwinding, focus, and reflection (5 min). Ten health-related activity units were designed, including aerobic dance, aerobic games, strolling/running, and jump-rope. The movements were developed by changing the intensity, length, and intricacy of the activities.

Although our primary focus was creating cardiovascular stamina, brief activities to develop stomach and chest strength, as well as movement skills, were incorporated. To improve motivation, children self-estimated and recorded their fitness levels from month to month. Four game units which developed ability-related fitness were incorporated (basketball, football, gymnastics, and athletics), and details of healthy lifestyles and unconventional physical activities were introduced. These sports and games had the potential for advancing cardiovascular fitness and speculation in the child’s community (e.g., fun transfers); unwinding, focus, and reflection improving with regular exercise; and valuable impacts for meditation or unwinding, namely through children’s yoga ( Table 2 ).

Physical education program (First and Second Grades).

During the study, physical education activities were taught through physical schooling, by preparing a textbook comprising two interrelated parts: (a) a textbook and (b) children’s notes. The textbooks were filled with logical tasks, self-evaluation, and activities relating to spatial perception and self-improvement. The methodological devices provide strategies for practicing with textbooks. The physical education pack considers a “natural” kind of integration and dynamic learning, building awareness, encouraging sensitivity to nature, and supporting healthy styles of living. The physical education pack takes into consideration a “natural” kind of integration and dynamic learning, building awareness, encouraging sensitivity to nature, and supporting healthy styles of living. The instructor’s manual has a unified structure, which makes it simple to utilize. Its proposals and advice are clear. The advanced version helps educators in their planning and execution activities.

The material seriously assesses intercultural mindfulness and sensitivity. The gender description is balanced; the two personalities highlighted in the textbook support this methodology. Vaquero-Solís et al. found that mixed procedures in their interventions, executed using a new methodology, greatly affected the participants [ 30 ]. Once each month, the standard methodology was applied, during which the change from hypothesis to practice was continuous. During the first exercise of the month, the material in the textbook was analysed for the future, and undertakings for the month were presented. The hypothesis was set up during practical sessions. During the hypothetical exercises, the children additionally had the chance to move around, practising the physical tasks given in the textbook. During the last exercise of the month, the tasks introduced in the textbook were performed; the activities of the month were rehashed, recalled, summed up, and assessed; and the assignment of children’s notes were performed. Children from the control group attended unmodified physical education exercises.

2.4. Data Analysis

Graphic statistics are presented for all methodical factors as the mean ± SD. The impact size of the Mann–Whitney U test was determined using the equation r = Z / N , where Z is the z-score and N is the total size of the sample (small: 0.1; medium: 0.3; large: 0.5). Statistical significance was defined as p ≤ 0.05 for all analyses. Analyses were carried out by utilizing the SPSS 23 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

3.1. Physical Activity of 6–7- and 8–9-Year-Old Children in the Experimental Group

Analysing the physical activity pre-test results of the 6–7- and 8–9-year-old children, it turned out that both the First Grade (92.15 MET, min/week) and Second Grade (97.50 MET, min/week) children in the experimental group were physically active during physical education lessons. The analysis of physical activity types, such as cycling to school, showed no differences in age, according to the MET; however, there were differences in walking to school—First Grade (15.98 MET, min/week) and Second Grade (23.50 MET, min/week)—in terms of age, according to the MET. In the context of average physical activity, a higher indicator (805.95 MET, min/week) was detected in the First Grade of the experimental group, in comparison with the Second Grade (1072.12 MET, min/week). Statistically significant differences were found in average MET for the First Grade (931.60 MET, min/week), in comparison with the Second Grade (1211.55 MET, min/week; p < 0.05, Table 3 ). The post-test of the First Grade (115.83 MET, min/week) experimental group was carried out to analyse average physical activity, in comparison with the Second Grade experimental group (130.01 MET, min/week), during physical education lessons. In the post-test, walking to school—First Grade (16.07 MET, min/week) and Second Grade (30.37 MET, min/week)—showed differences in age, according to the MET. Statistically significant differences were found during the analysis of average MET for the First Grade (1108.41 MET, min/week), in comparison with the Second Grade (1453.62 MET, min/week; p < 0.05, Table 3 ). We found a statistically significant difference between experimental and control groups ( p < 0.05) and between pre- and post-test.

Physical activity levels determined using the MET method.

Note. *, p < 0.05 (according to the Mann–Whitney U test) between physical activity types; # , p < 0.05 (according to the Mann–Whitney U test) between experimental and control groups; $ , p < 0.05 (according to the Mann–Whitney U test) between First and Second Grades; § , p < 0.05 (according to the Mann–Whitney U test) between pre-test and post-test.

3.2. Physical Activity of 6–7- and 8–9-Year-Old Children in the Control Group

Analysing the results considering the physical activity of 6–7- and 8–9-year-old children, it turned out that in the control group, both the First Grade (91.68 MET, min/week) and Second Grade (95.87 MET, min/week) children were physically active in physical education lessons during the pre-test. The analysis of physical activity types, such as cycling to school, found no differences in age, according to the MET. We found that walking to school—First Grade (0.00 MET, min/week) and Second Grade (22.15 MET, min/week—showed differences in age, according to the MET. Statistically significant differences were found during the analysis of average MET for the First Grade in the control group (906.40 MET, min/week), compared to the Second Grade (1105.71 MET, min/week; p < 0.05, Table 4 ). The post-test results for the First Grade of the control group (98.10 MET, min/week) were determined by the analysis of average physical activity, in comparison with the Second Grade children of the same group (105.70 MET, min/week), when doing physical education lessons. Statistically significant differences were found in average MET for the First Grade (995.66 MET, min/week), in comparison with the Second Grade (1211.70 MET, min/week; p < 0.05, Table 4 ).

The physical activity level using the MET method (the pre-test/post-test results of the control group).

The study performed at the beginning of the experiment showed that in the pre-test, the level of somatic anxiety of the primary school children in the CG was average (4.95 ± 1.10 points). When exploring the results of the somatic anxiety in the EG (4.95 ± 1.10 points) before and after the experiment, after the intervention programme, somatic anxiety in the EG was 4.55 ± 1.00 points, indicating lower levels of depression, seclusion, somatic complaints, aggression, and delinquent behaviours (F = 4.785, p < 0.05, P = 0.540; Figure 1 a).

Pre- and post-test levels of somatic anxiety ( a ), personality anxiety ( b ), and social anxiety ( c ) in primary school children. # , p < 0.05 between experimental and control groups; $ , p < 0.05 between First and Second Grades; *, p < 0.05 between pre- and post-test.

3.3. Anxiety of 6–7-Year-Old Children (First Grade)

When dealing with the personality anxiety results, we established that in the pre- and post-tests, the results of CG students did not statistically significantly differ (3.63 ± 0.80 points and 3.48 ± 0.50 points, respectively; F = 0.139, p > 0.05, P = 0.041). When analysing EG personality anxiety results in the pre- and post-tests, after the intervention programme, the EG personality anxiety results significantly decreased (3.55 ± 1.10 points and 2.78 ± 0.90 points, respectively; F = 5.195, p < 0.05, P = 0.549; Figure 1 b).

In the pre-test, the level of social anxiety in the CG was 6.15 ± 1.30 points. The post-test CG result was statistically significantly lower (5.18 ± 1.20 points; F = 4.75, p < 0.05, P = 0.752). When analysing the levels of the social anxiety of the EG, pre- and post-test results decreased after the intervention programme (6.32 ± 1.10 points and 4.25 ± 1.40 points, respectively) and significantly differed (F = 8.029, p < 0.05, P = 0.673; Figure 1 c).

3.4. Anxiety of 8–9-Year-Old Children (Second Grade)

The research performed at the beginning of the experiment showed that in the pre-test, the level of somatic anxiety of the adolescents in the CG was average (4.63 ± 1.10 points). When exploring the somatic anxiety results in the EG (4.50 ± 0.90 points) before the experiment and after it, a decrease in somatic anxiety in the EG was established (4.10 ± 0.75 points), indicating lower levels of depression, seclusion, somatic complaints, aggression, and delinquent behaviours (F = 4.482, p < 0.05, P = 0.610; Figure 1 a).

When dealing with the personality anxiety results, we established that in the pre- and post-test, the results of CG students were not statistically significantly different (3.10 ± 0.85 points and 2.86 ± 0.67 points, respectively; F = 0.127, p > 0.05, P = 0.057). When analysing the pre- and post-test EG personality anxiety results, after the intervention programme, the EG personality anxiety results decreased (2.93 ± 0.93 points vs. 2.51 ± 1.00 points, respectively; F = 6.498, p < 0.05, P = 0.758; Figure 1 b).

In the pre-test, the level of social anxiety in the CG was 4.55 ± 1.30 points. The post-test CG result was statistically significantly lower (3.70 ± 1.40 points; F = 4.218, p < 0.05, P = 0.652). When analysing the levels of social anxiety in the EG, pre- and post-test results decreased after the intervention programme (4.65 ± 1.15 points and 3.01 ± 1.50 points, respectively) and were significantly different (F = 8.021, p < 0.05, P = 0.798; Figure 1 c).

4. Discussion

The outcomes of this study showed that the proposed procedure for a physical education program and educational model encouraging physical activity in children had an impact on three primary dimensions—somatic anxiety, personality anxiety, and social anxiety—for children aged 6–7 and 8–9 years. The procedure depended on dynamic exercise, intense motor skills reiteration, differentiation, seating and parking reduction, and physical activity dissemination in the classroom model. Following eight months of applying this study’s physical education program, anxiety decreased in the children. Schools provide an opportune site for addressing PA promotion in children. With children spending a substantial number of their waking hours during the week at school, increased opportunities for PA are needed, especially considering trends toward decreased frequency of physical education in schools [ 31 , 32 ]. Considering physical education curricula, Chen et al. [ 29 ] described the following:

- Aerobic activities: Most daily activities should be moderate- to vigorous-intensity aerobic activities, such as bicycling, playing sports and active games, and brisk walking.

- Strength training: The program should include muscle-strengthening activities at least three days a week, such as performing calisthenics, weight-bearing activities, and weight training.

- Bone strengthening: Bone-strengthening activities should also be included at least three days a week, such as jump-rope, playing tennis or badminton, and engaging in other hopping-type activities.

School-related physical activity interventions may reduce anxiety, increase resilience, improve well-being, and increase positive mental health in children and adolescents [ 33 ]. Increasing activity levels and sports participation among the least active young people should be a target of community- and school-based interventions in order to promote well-being. Frequency of physical activity has been positively correlated with well-being and negatively correlated with both anxiety and depressive symptoms, up to a threshold of moderate frequency of activity. In a multi-level mixed effects model, more frequent physical activity and participation in sport were both found to independently contribute to greater well-being and lower levels of anxiety and depressive symptoms in both sexes [ 34 ]. There does not appear to be an additional benefit to mental health associated with meeting the WHO-recommended levels of activity [ 9 ]. Physical activity interventions have been shown to have a small beneficial effect in reducing anxiety; however, the evidence base is limited. Reviews of physical activity and cognitive functioning have provided evidence that routine physical activity can be associated with improved cognitive performance and academic achievement, but these associations are usually small and inconsistent [ 35 ]. Advances in neuroscience have resulted in substantial progress in linking physical activity to cognitive performance, as well as to brain structure and function [ 36 ]. The executive functions hypothesis proposes that exercise has the potential to induce vascularization and neural growth and alter synaptic transmission in ways that alter thinking, decision making, and behaviour in those regions of the brain tied to executive functions—in particular, the pre-frontal cortices [ 37 , 38 ]. The brain may be particularly sensitive to the effects of physical activity during pre-adolescence, as the neural circuitry of the brain is still developing [ 8 ].

During their school years, about 33% of primary and secondary school students experience the adverse effects of test anxiety [ 39 ]. Anxiety is an aversive motivational state which occurs when the degree of perceived threat is viewed as high [ 40 ]. In the concept of anxiety, a frequently made differentiation is created between trait anxiety, referring to differences in personality dimensions, and state anxiety, alluding to anxiety as a transient mindset state. These two kinds of anxiety hamper performance, particularly during complex and intentionally requested assignments [ 41 ]. Mavilidi et al. [ 42 ] presented a study investigating whether a short episode of physical activity can mitigate test anxiety and improve test execution in 6th grade children (11–12 years). The discoveries of the study by the above authors expressed that, even though test anxiety was not decreased as expected, short physical activity breaks can be utilized before assessments without blocking academic performance [ 43 ].

Physical activity has been associated with physiological, developmental, mental, cognitive, and social health benefits in young people [ 36 ]. While the health benefits of physical activity are well-established, higher levels of physical activity have also been associated with enhanced academic-related outcomes, including cognitive function, classroom behaviour, and academic achievement [ 44 ]. The evidence suggests a decline in physical activity from early childhood [ 45 ]. The physical and psychological benefits of physical activity for children and adolescents include reduced adiposity and cardiometabolic risk factors, as well as improvements in musculoskeletal health and psychological well-being [ 33 , 46 , 47 ]. However, population based-studies have reported that more than half of all children internationally are not meeting the recommended levels of physical activity, with rates of compliance declining with age from the early primary school years [ 9 ]. Therefore, it is imperative to promote physical activity and intervene early in childhood, prior to such a decline in physical activity [ 48 ]. Schools are considered ideal settings for the promotion of children’s physical activity. There are multiple opportunities for children to be physically active over the course of the school week, including during break times, sport, physical education class, and active travel to and from school [ 49 ]. There exists strong evidence of the benefits of physical activity for the mental health of children and adolescents, mainly in terms of depression, anxiety, self-esteem, and cognitive functioning [ 35 ].

Physiological adaptation (e.g., hormonal regulation) of the body during physical exercise can be applied additionally to psychosocial stressors, thus improving mental health [ 48 ]. Subsequently, it has been stated that intense physical activity which improves health-related fitness may be expected to evoke neurobiological changes affecting psychological and academic performance [ 43 ].

The results of this review contribute to knowledge about the multifaceted interactions influencing how physical activity can be enhanced within a school setting, given certain contexts. Evidence has indicated that school-based interventions can be effective in enhancing physical activity, cardiorespiratory and muscular fitness, psychosocial outcomes associated with physical activity (e.g., enjoyment), and other markers of health status in children. School- and community-based physical activity interventions, as part of an obesity prevention or treatment programme, can benefit the executive functions of children, specifically those with obesity or who are overweight [ 46 ]. Considering the positive effects of physical activity on health in general, these findings may reinforce school-based initiatives to increase physical activity [ 34 ]. This involves classroom teachers incorporating physical activity into class time, either by integrating physical activity into physically active lessons, or adding short bursts of physical activity with curriculum-focused active breaks [ 50 , 51 ]. It is widely accepted that physical inactivity is an important risk factor for chronic diseases; prevention strategies should begin as early as childhood, as the prevalence of physical inactivity increases even more in adolescence [ 52 ]. A physically active lifestyle begins to form very early in childhood and has a positive tendency to persist throughout life [ 52 ].

We all have an important role to play in increasing children’s physical activity. Schools must promote and influence a healthy environment for children. Most primary school children spend an average of 6–7 h a day at school, which is most of their daytime. A balanced and adapted physical education lesson provides cognitive content and training for developing motor skills and knowledge in the field of physical activity. Our 8-month physical education program can give children the opportunity to increase physical activity and improve emotional well-being, which can encourage children to be physically active throughout life.

5. Conclusions

Low physical activity in children is a major societal problem. The growing number of children with obesity is a concern for doctors and scientists. The focus of our study was to improve emotional well-being and physical activity in children. Since elementary school children spend most of their day at school, physical education lessons are a great tool to increase physical activity. A balanced and adapted physical education lesson can help to draw children’s attention to the health benefits of physical activity. It was established that the properly constructed and purposefully applied 8-month physical education program had an impact on the physical activity and emotional well-being of primary school children (i.e., 6–7 and 8–9 year olds) in three main dimensions: somatic anxiety, personality anxiety, and social anxiety. Our findings suggest that the 8-month physical education program intervention is effective for increasing levels of physical activity. Changes in these activities may require more intensive behavioural interventions in children or upstream interventions at the family and societal level, as well as at the school environment level. These findings have relevance for researchers, policy makers, public health practitioners, and doctors who are involved in health promotion, policy making, and commissioning services.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.K. and S.S.; methodology, I.K.; software, R.A.; validation, G.C.; formal analysis, K.Z.; investigation, K.Z.; resources, I.K.; data curation, G.C.; writing—original draft preparation, I.K.; writing—review and editing, S.S.; visualization, G.C.; supervision, R.A.; project administration, R.A.; funding acquisition, K.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki. The time and place of the study, with the consent of the parents of the participants, were agreed upon in advance with the school administration. This study was approved by the research ethics committee of Kaunas University of Technology, Institute of Social Science and Humanity (Protocol No V19-1253-03).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of interest.

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

- Open access

- Published: 02 April 2024

The effect of the Sport Education Model in physical education on student learning attitude: a systematic review

- Junlong Zhang 1 ,

- Wensheng Xiao 2 ,

- Kim Geok Soh 1 ,

- Gege Yao 3 ,

- Mohd Ashraff Bin Mohd Anuar 4 ,

- Xiaorong Bai 2 &

- Lixia Bao 1

BMC Public Health volume 24 , Article number: 949 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

1090 Accesses

Metrics details

Evidence indicates that the Sport Education Model (SEM) has demonstrated effectiveness in enhancing students' athletic capabilities and fostering their enthusiasm for sports. Nevertheless, there remains a dearth of comprehensive reviews examining the impact of the SEM on students' attitudes toward physical education learning.

The purpose of this review is to elucidate the influence of the SEM on students' attitudes toward physical education learning.

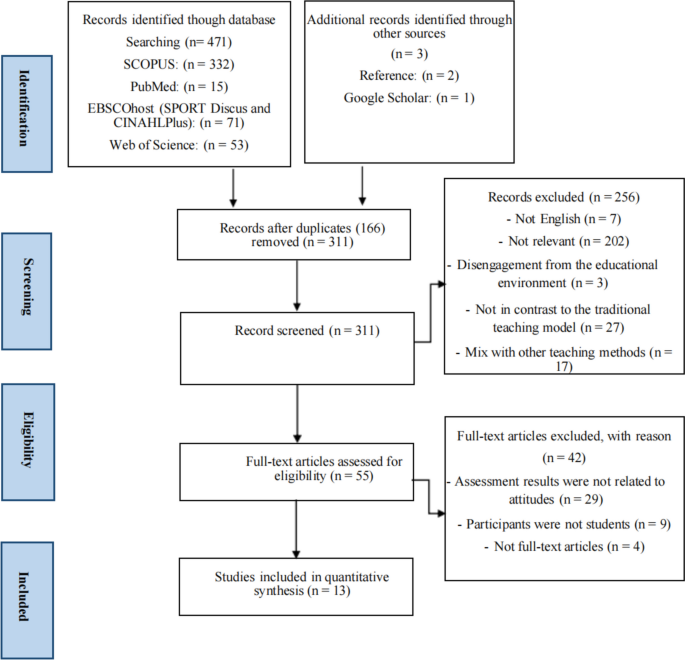

Employing the preferred reporting items of the Systematic Review and Meta-analysis (PRISMA) statement guidelines, a systematic search of PubMed, SCOPUS, EBSCOhost (SPORTDiscus and CINAHL Plus), and Web of Science databases was conducted in mid-January 2023. A set of keywords associated with the SEM, attitudes toward physical education learning, and students were employed to identify relevant studies. Out of 477 studies, only 13 articles fulfilled all the eligibility criteria and were consequently incorporated into this systematic review. The validated checklist of Downs and Black (1998) was employed for the assessment, and the included studies achieved quality scores ranging from 11 to 13. The ROBINS-I tool was utilized to evaluate the risk of bias in the literature, whereby only one paper exhibited a moderate risk of bias, while the remainder were deemed to have a high risk.

The findings unveiled significant disparities in cognitive aspects ( n = 8) and affective components ( n = 12) between the SEM intervention and the Traditional Teaching (TT) comparison. Existing evidence suggests that the majority of scholars concur that the SEM yields significantly superior effects in terms of students' affective and cognitive aspects compared to the TT.

Conclusions

Nonetheless, several issues persist, including a lack of data regarding junior high school students and gender differences, insufficient frequency of weekly interventions, inadequate control of inter-group atmosphere disparities resulting from the same teaching setting, lack of reasonable testing, model fidelity check and consideration for regulating variables, of course, learning content, and unsuitable tools for measuring learning attitudes. In contrast, the SEM proves more effective than the TT in enhancing students' attitudes toward physical learning.

Systematic review registration

( https://inplasy.com/ ) (INPLASY2022100040).

Peer Review reports

Introduction

In recent years, the "student-centered" teaching model, as a more effective alternative to the traditional "teacher-centered" teaching model, has gained increasing attention and recognition from education scholars and departments worldwide [ 1 , 2 ]. Metzler [ 3 ] identified a series of "student-centered" teaching models based on constructivism and social learning theories, each developed for specific course objectives [ 4 , 5 ]. Furthermore, it is widely acknowledged that instructional models are in a constant state of development, involving the generation, testing, refinement, and further testing processes under different educational objectives. These instructional models are designed to enable students to acquire a depth and breadth of knowledge in physical education [ 6 ]. In this regard, a series of instructional models have been identified as effective means to achieve specific objectives. Consequently, numerous studies have established that placing students at the center of the instructional process is the most effective approach [ 7 ], allowing for the assessment of the impact of these models on students' learning in physical education. For instance, Cooperative Learning (CL), rooted in the idea of learning together with others, through others, and for others [ 8 ], aims to promote five essential elements [ 9 ]: interpersonal skills, processing, positive interdependence, promoting interaction, and individual responsibility. The underlying concept of Teaching Game for Understanding (TGFU) involves shifting the focus from technical aspects of gameplay to the context (tactical considerations) through modification of representation and exaggeration [ 4 , 10 ]. Emphasizing placing learners in game situations where tactics, decision-making, and problem-solving are non-negotiable features, despite incorporating skill practice to correct habits or reinforce skills [ 11 ], TGFU is structured around six steps: game, game appreciation, tactical awareness, decision-making, skill execution, and performance. Teaching for Personal and Social Responsibility (TPSR), designed by Hellison [ 12 ], aims to cultivate personal and social responsibility in young people through sports activities, defining four major themes: integration, transfer, empowerment, and teacher-student relationships. It revolves around five responsibility goals: respecting the rights and feelings of others, effort (self-motivation), self-direction, caring (helping), and transferring beyond the "gym" [ 13 ]. The SEM comprises six key structural features: season, affiliation, formal competition, culminating events, record-keeping, and festivity. SEM seeks to provide students with authentic, educationally meaningful sporting experiences within the school sports context, aiming to achieve the goal of developing capable, cultured, and enthusiastic individuals [ 14 ]. This suggests a subtle intersection between SEM's developmental goals and enhancing students' learning attitudes (cognitive and emotional), laying the foundation for the selection of teaching model types in this study.

In previous SEM-centered reviews, the focus primarily centered on the model's positive impact on students' personal and social skills [ 15 , 16 ], motor and cognitive development [ 16 ], motivation [ 17 , 18 ], basic needs [ 18 ], prosocial attitudes [ 18 ], and learning outcomes [ 19 ], and it is concluded that the implementation of SEM has a positive effect on improving students' performance in these aspects. While these reviews contribute valuable insights, they exhibit certain limitations, such as a lack of comprehensive exploration of the model's impact on the cognitive and emotional dimensions in the context of school-based physical education. Therefore, our study attempts to bridge this gap by delving into the nuanced intersection between SEM and students' learning attitudes, aiming to provide a more comprehensive understanding of its impact on educational environments.

In the field of education, a focus on practical application and scholarly discourse is crucial and commendable [ 20 , 21 ]. From a practical perspective, research should offer valuable resources for curriculum designers, educators, and policymakers [ 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 ]. In theoretical terms, the contribution of research lies in addressing gaps in the literature by elucidating dimensions within physical education that remain insufficiently explored [ 26 ]. Our study is dedicated to significantly impacting physical education teaching through the practical application and scholarly discourse surrounding SEM. By revealing the subtle interactions between SEM and attitudes, we aim to provide valuable curriculum implementation recommendations for designers, practitioners, and policymakers, filling the gaps in how SEM shapes learning attitudes in educational environments.

In the realm of attitude research, scholars have traditionally classified attitude components into three types: single-component, two-component, and three-component. Advocates of the single-component view contend that attitudes are confined to the emotional dimension. For example, Fazio and Zanna [ 27 ] define attitude as "an evaluative feeling caused by a given object" (p. 162). Two-component researchers posit that attitudes comprise cognition and emotion, with the affective component measuring emotional attraction or feelings toward the object, and the cognitive component representing beliefs about the object's characteristics [ 28 , 29 ]. Bagozzi and Burnkrant [ 30 ] compared the effectiveness of one-component and two-component attitude models, concluding that incorporating both cognitive and emotional dimensions enhances attitude effectiveness. On the contrary, proponents of the three-component perspective argue that attitudes encompass cognition, emotion, and behavior, suggesting that cognitive and emotional responses to an object influence behavior. However, the three-component view has faced skepticism, with some researchers finding that attitude measurement explains only about 10% of behavior variance. Studies reporting higher correlations often focus on attitudes and behavioral intent rather than explicit behavior itself [ 31 , 32 , 33 ]. Our research places a deliberate emphasis on investigating the intersection between the SEM and attitudes to address a noticeable gap in the existing scholarly landscape. While none of the reviewed literature approached the subject from an attitude theory perspective, we prioritize this theoretical framework, acknowledging that attitudes significantly influence student learning [ 16 , 34 ]. Consequently, the exploration of the interplay between SEM and attitudes is considered indispensable for attaining a thorough comprehension of SEM's potential impact in educational contexts. By integrating attitude theory into this inquiry, there is an aspiration to unveil nuanced insights into the cognitive and emotional dimensions influenced by SEM, thereby enriching the understanding of the model's pedagogical implications.

The chosen systematic review approach in this study aims to enhance the reader's understanding of the research methodology, thereby strengthening the overall scientific rigor of the study [ 35 ].

Protocol and registration

This review adheres to the guidelines set forth by the Preferred Reporting Project for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA). The review has been registered on the International Registry Platform for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Programmes (INPLASY) under the registration number INPLASY2022100040. More information about the review can be found at the following link: https://inplasy.com/ .

Search strategy

In October 2004, Siedentop initiated SEM workshops, attracting widespread attention from scholars both domestically and internationally, marking the beginning of SEM practices [ 36 , 37 ]. Subsequently, in many advanced countries such as the United States, New Zealand, Australia, and the United Kingdom, SE has become a mainstream approach in physical education instruction [ 38 ]. Therefore, the retrieval period for this review is set from October 2004 to December 2023, encompassing relevant articles published during this timeframe. A systematic search of four electronic databases was conducted for relevant articles: SCOPUS, PubMed, EBSCOhost (SPORT Discus and CINAHL Plus), and Web of Science. The search aimed to identify studies on the effects of SEM on attitudes toward physical education learning. We employed advanced search methods and added the following search terms: ("Sport Education Model" OR "Sport Education" OR "Sport season") AND ("learning attitude" OR "sports attitude" OR "cognitive" OR "cognition" OR "usefulness" OR "importance" OR "perceptions" OR "affective" OR "emotional" OR "enjoyment" OR "happiness" OR "well-being" OR "Blessedness" OR "subjective well-being") AND ("student" OR "pupil" OR "scholastic" OR "adolescent" OR "teenager"). The search expressions were combined using logical operators. We also sought assistance from librarians in the field to ensure comprehensive results. Furthermore, we manually examined the reference lists of the included studies to identify additional relevant literature and validate the effectiveness of our search strategy.

Eligibility criteria

We employed the Picos framework, encompassing Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcomes, and Study Design, as the inclusion criteria for this systematic review (Table 1 ). Furthermore, the selected literature adhered to the following additional criteria: (i) it comprised full English texts published in peer-reviewed journals; (ii) the interventions were conducted within the context of physical education, with a comprehensive description of the intervention process and content; (iii) the effects of the SEM and TT on students' learning attitudes (cognitive and emotional) were compared on at least one dimension; (iv) quasi-experimental designs employing objective tests and measurements, along with studies presenting evaluation results, were considered. Exclusion criteria encompassed studies that combined physical education models with other teaching methods or models (hybrid or invasive). Initially, the search strategy was guided by a librarian, and duplications were eliminated by importing the retrieved literature into Mendeley reference management software. Subsequently, decisions regarding literature exclusion and retention were made through the screening of titles and abstracts. Ultimately, articles deemed highly relevant were read in full. The primary outcome aimed to assess attitudes (cognitive and affective) toward physical learning based on the SEM.

The search strategy was guided by a librarian, and the obtained literature was imported into Mendeley reference management software for duplicate removal. Decisions regarding literature inclusion and exclusion were made based on the screening of titles and abstracts. Articles that were deemed highly relevant were read in their entirety. The primary focus of this review was to assess attitudes (cognitive and affective) toward physical learning, specifically based on the SEM. The designation "not relevant" is employed to characterize articles subjected to thorough scrutiny, which fail to make substantive contributions to the fundamental focus of our research. More precisely, those articles deemed irrelevant were those that omitted consideration of the pivotal variables under examination, namely, cognitive and emotional dimensions. Furthermore, they were not situated within the milieu of a scholastic educational framework for physical education (SEM). This methodological approach has been instituted to uphold the establishment of a centralized and cohesive dataset requisite for subsequent analytical procedures [ 39 ] (See Fig. 1 ).

PRISMA summary of the study selection process

Study selection

Prior to conducting the search, consultation with an experienced librarian was sought to develop an effective retrieval strategy. Following this, two independent reviewers conducted the literature search. All retrieved studies were imported into Mendeley literature management software to identify and eliminate duplicates. Initially, the literature was screened based on the titles by two independent evaluators, who excluded irrelevant studies. Subsequently, the abstracts of the initially selected literature were reviewed against pre-established inclusion criteria to determine their eligibility for inclusion in the study. Finally, the full text of the included literature was reviewed by two authors, who extracted relevant information. In the case of any disagreements, a third author (K.G.S.) was involved in the review process.

Data extraction and quality assessment

The data extraction process involved collecting the following information: (1) author and year of publication; (2) research design, including the type of experiment or teaching project; (3) population details, such as student category, total number of students, age range, and gender distribution, as well as group size; (4) intervention characteristics, including the total number of interventions, weekly frequency of interventions, duration of each intervention, and consistency of intervention location; (5) a comparison group, typically involving the TT and country information; (6) results, which encompassed the measurement tools used, specific indicators measured, and the research findings. The collected data were independently summarized and reviewed by two authors, with the involvement of a third author to resolve any discrepancies or disagreements.

The methodological quality of the selected articles in this systematic review was assessed using the validated checklist developed by Downs and Black [ 40 ]. The checklist consisted of 27 items, which were categorized into three domains: reporting (items 1–10), validity (external validity: items 11–13; internal validity: items 14–26), and statistical power (item 27). Each item was scored, resulting in a total score ranging from 0 to 27, with higher scores indicating higher methodological quality.

In this review, the cross-sectional and longitudinal surveys were scored in detail using the Downs and Black checklist to evaluate the strengths and weaknesses of each study [ 40 ]. The scoring process involved two primary assessors independently assessing the selected studies. In case of any ambiguity or disagreement, a resolution was reached through reconciliation. If disagreements persisted, the assessment was conducted by one of the co-authors until a consensus was reached.

The classification criteria for the scores were as follows: studies with a score below 11 were considered to have low methodological quality, scores ranging from 11 to 19 indicated medium quality, and scores higher than 20 indicated high methodological quality [ 41 ]. Upon assessment, it was found that all selected articles in this review fell within the medium-quality range (see Table 2 ).

The studies risk of bias

The Risk of Bias in Non-randomized Studies-of Interventions (ROBINS-I) tool encompasses seven evaluation areas, which are further divided into three distinct stages: pre-intervention, intervention, and post-intervention. The pre-intervention stage includes two evaluation areas: confounding bias and selection bias of participants. The intervention stage focuses on the evaluation of bias in the classification of interventions. The post-intervention stage comprises four evaluation areas: bias due to deviations from intended interventions, bias due to missing data, bias in the measurement of outcomes, and bias in the selection of reported results. Each evaluation area is composed of multiple signaling questions, amounting to a total of 34 signaling questions.

Methodical quality

The articles underwent assessment using the validated checklist developed by Downs and Black (1998): 11–13 (mean = 12.38; median = 12; mode = 12 & 13). All the articles demonstrated a medium level of quality, indicating their suitability for inclusion in this review. Furthermore, it suggests the potential for higher-quality articles in future studies. Among the thirteen included articles, five were published within the last three years, constituting one-third of the included literature. This observation highlights the ongoing research interest and significance of the SEM in the investigation of various teaching models. In terms of the Hypothesis/aim/objective, participant characteristics, interventions, main findings, data variability, probability values, statistical tests, detailed intervention descriptions, reliable outcome measures, participant source ( n = 12), participant grouping ( n = 11), and random allocation ( n = 3) were adequately addressed. However, aspects such as reporting measurement outcomes in the introduction or methods section, confounder distribution, adverse events following the intervention, characterization of lost-to-follow-up patients, data analysis, blinding of participants and assessors, adjustment for confounding, and identification of chance results with a probability less than 5% ( n = 0) were not thoroughly addressed. Although the implementation of blind subjects, therapists, and assessors in teaching experiments poses challenges, future research should strive for higher quality and stronger levels of evidence [ 23 ].

After a detailed reading of the literature that meets the inclusion criteria of this review and the extraction and sorting of important information, it is presented in Table 3 .

The bias risk assessment results are summarized in Table 4 , which includes information such as author/date, field of study, study type, risk assessment tool, and overall rating. The main sources of bias identified were confounding factors and outcomes measurement. The evaluation revealed that only two experimental studies in the Confounders field had a moderate risk of bias, while the rest had a high risk of bias. All included literature demonstrated low risk in terms of subject selection, classification of recommended interventions, and deviation from established interventions. Furthermore, one-third of the literature showed low-risk missing data [ 23 , 42 , 50 , 51 ], while other studies did not provide relevant information. Lastly, nearly a third of the literature showed missing data for low-risk.

Overview of sports and experiment design

All thirteen papers included in this review utilized a pre-posttest design. The sports covered in these studies encompassed basketball, volleyball, soccer, ultimate Frisbee, table tennis, hockey, Polskie ringo, ball games, and body movements. Some studies examined two exercise programs [ 23 , 43 ], while the majority of research focused on basketball [ 44 , 52 , 53 ]. The participants in the course experiments were primarily college and high school students, with a limited number of studies investigating primary and junior high school students. The distribution of participants included college students (3), high school students (8), primary school students (1), and junior high school students (1). The sample sizes in these studies ranged from 40 to 508. Since the selected studies were teaching experiments, most of them involved mixed-sex classes, with four studies not specifying the gender of the students. Only one study established three experimental classes and two control classes [ 50 ], while the remaining studies had one experimental class and one control class. The number of interventions ranged from 8 to 25, with each intervention lasting between 45 and 90 min.

The majority of studies in the selected literature directly applied the SEM as the intervention. Five of the studies incorporated constructivism theory [ 48 ], self-determination theory [ 23 , 44 , 47 ], and ARCS learning motivation theory [ 52 ]. None of the literature investigated from the perspective of attitude theory. Furthermore, none of the selected studies mentioned the teaching standards or syllabus used to design the course content, nor did they provide explanations for the rationale behind the experimental teaching content. The number of interventions in the trials ranged from 8 to 25, with up to half of the studies using fewer than 18 interventions [ 42 , 47 , 48 , 49 , 50 , 52 , 53 ], the recommended class hours for large unit teaching are not met [ 54 ]. The duration of each intervention was most commonly reported as 45 or 60 min [ 42 , 43 , 44 , 47 , 49 , 50 , 51 , 52 , 53 ]. The frequency of weekly interventions varied from 1 to 5, but the majority of studies implemented interventions once a week [ 23 , 42 , 43 , 46 , 47 , 48 , 49 ]. The intervention frequency was generally low, and there was a scarcity of studies with higher intervention frequency. With the exception of one article that conducted the intervention in two schools without providing an explanation [ 50 ], the remaining studies were conducted within the same school.

The control classes in the selected literature implemented similar TT and forms, despite variations in naming used by scholars from different countries or even within the same country. The TT employed in the control classes were mainly Direct Instruction in Australia [ 43 , 46 , 47 , 51 , 52 ], Morocco [ 50 ], and Spain [ 42 , 43 , 44 ], In China, the traditional teaching models were referred to as TT [ 48 , 52 ] and Latent Growth Model [ 49 ]; Traditional Style in the United States and England [ 42 ], American Skill-drill-game [ 44 , 45 ], and multiactivity model [ 23 ].

Measuring instruments and main outcomes

The findings of this investigation were classified based on the impact of the SEM on various aspects of students' attitudes toward physical education: cognitive and affective domains. Through the segregation of subjects and constituents from prior research, the favorable and unfavorable indicators of affective and cognitive dimensions were predominantly derived from the existing body of literature.

The effect of SEM on student cognitive

In this literature review, it was evident that all the included studies reached a unanimous conclusion that the overall effectiveness of the SEM surpassed that of the TT. Among these studies, eight of them specifically evaluated students' cognitive performance [ 23 , 42 , 43 , 45 , 48 , 50 , 52 ]. Various assessment instruments were employed, such as the Intrinsic Motivation Inventory (IMI) [ 42 , 43 , 45 ], the Amotivation subscale of the Academic Motivation Scale (AMS) [ 23 ], the attitude questionnaire [ 48 ], the Spanish version of the Sport Satisfaction Instrument (SVSSI) [ 50 ], the ARCS Learning Motivation Scale, the Physical Education Affection Scale (PEAS) [ 52 ], and the ALT-PE data were collected using momentary time sampling for each team by trained coders [ 53 ].

The study participants encompassed junior high school students [ 43 ], high school students [ 23 , 42 , 45 , 48 , 50 ] and College students [ 52 , 53 ]. Most of these investigations revealed that following the intervention of the physical education course, the cognitive abilities of students in the intervention group exhibited significant improvement, surpassing those of the control group instructed through the TT. Conversely, no significant changes were observed within the control group before and after the experiment [ 23 , 42 , 48 , 50 ]. Nevertheless, one study reported a significant decrease in cognitive abilities among students in the control group before and after the experiment [ 54 ], the other two studies showed that both the experimental and control groups showed significant improvements, but the experimental group showed significantly greater improvements [ 52 , 53 ].

The effect of SEM on student's affective

In this comprehensive review, all the included studies examined students' affective aspects. The assessment instruments employed were as follows: Intrinsic Motivation Inventory (IMI) [ 42 , 43 , 44 , 45 , 47 ], Amotivation subscale of the Academic Motivation Scale (AMS) [ 23 ], Intention to be Physically Active Scale (IPAS) [ 46 ], the attitude questionnaire [ 48 ], Physical activity enjoyment scale (PACES) [ 49 ], the Spanish version of the Sport Satisfaction Instrument (SVSSI) [ 50 ], Positive and Negative Affect Scale (PANASN) [ 51 ] and the Physical Education Affection Scale (PEAS) [ 52 ].

The study participants encompassed primary school students [ 51 ], Junior high school students [ 43 ], high school [ 23 , 42 , 44 , 45 , 46 , 47 , 48 , 50 , 51 ] and College students [ 49 , 52 ]. Out of the 12 studies, four reported positive and/or negative interests or enjoyment among students. Among these, two studies indicated that the experimental group students exhibited significantly higher positive affect than the control group students [ 47 , 51 ]. However, the measurement results varied within the control group. One study reported no significant improvement [ 47 ], while another study showed significant improvement, but the effect was significantly greater in the experimental group compared to the control group [ 51 ]. Furthermore, one study demonstrated no significant difference between the two groups as the test indicators did not exhibit significant changes before and after the experiment [ 46 ].

Regarding the investigation of negative affect, three studies reported that the experimental group students exhibited significantly lower negative affect compared to the control group [ 47 , 51 ], with a significant decrease in negative affect observed in the experimental group while no significant change was noted in the control group. Additionally, one study showed no significant difference and no significant improvement in the test results between the two groups before and after the experiment [ 46 ].

Among the remaining eight studies, it was not specified whether the investigation focused on positive or negative effects. Among them, two studies solely compared the improvement effects between the experimental and control groups without conducting intra-group comparisons before and after the experiment, and the results revealed that the experimental group exhibited significantly better outcomes than the control group [ 45 , 49 ]; the remaining six studies conducted comparisons not only between groups before and after the experiment but also within each group. Five studies demonstrated a significant increase in the affected index of the experimental group, while the control group exhibited no significant change [ 23 , 42 , 44 , 48 , 52 ], and one study revealed that the experimental group displayed a significant improvement, while the control group experienced a significant decline [ 43 ].

This paper presents a comprehensive review of the effects of the SEM on students' attitudes towards physical education. Its aim is to distinguish this study from other published research on the application of the SEM interventions among students. The findings indicate that the SE model has the potential to enhance students' attitudes toward physical education in terms of cognition and affect. However, certain factors such as the lack of data on junior high school students and gender differences, the frequency and duration of intervention per week, the variation in the learning environment across groups taught in the same setting, the rationale behind the course content, and the selection of tools for measuring learning attitudes may influence the experimental outcomes. Nonetheless, considering the positive results observed in these studies, is SEM an effective way to interfere with students' attitudes toward physical education learning? In conjunction with the information presented in the " Results " section, this review offers a detailed analysis of the impact of various dimensions of student attitudes toward physical education learning.

As anticipated, eleven out of the thirteen studies included in this review focused on ball games, which aligns with the competitive nature of these sports [ 55 ]. This choice is well-suited to the seasonal characteristics of the Sports Education Model (SEM) [ 56 , 57 ]. When considering gender comparisons, incorporating gender research can enhance the reliability of experimental findings [ 58 , 59 ]. However, in all the studies included, the majority of researchers only used mixed experimental and control groups, without comparing gender distinctions. If significant differences exist in the effect of SEM on the learning attitudes of students of different genders, it would significantly impact the accuracy of the experimental results.

Regarding the frequency, number, and duration of each intervention, some scholars have suggested that these factors may have different effects on the experimental outcomes [ 60 ], However, among the thirteen studies reviewed, the largest number of interventions was only 25 [ 23 ], and most studies had fewer than 20 interventions. Most studies had fewer than 18 interventions. This deviates from the use of large unit teaching advocated by some scholars to enhance students' systematic cognition and learning experience of a sports event [ 54 , 61 ]. In the reform of the school curriculum, the State Council of China issued the Curriculum Standards for Physical Education and Health for Compulsory Education (2022 edition) for students, which also clearly mentioned that the length of class hours for large units should not be less than 18 lessons.

In terms of the rationality of classroom teaching form and content, Hastie et al. [ 62 ] developed an Instructional Checklist to evaluate the effectiveness of the SEM and TT. However, only four of the included studies addressed this aspect [ 46 , 47 , 50 ]. Regarding the selection of measurement tools, none of the studies examined students' learning attitudes using scales developed based on attitude theory. According to the two-component proponents of attitude, attitude theory defines attitude as the affective and cognitive (positive or negative) evaluation of individuals toward the object of attitude [ 28 , 29 , 30 , 63 ]. Failing to assess student attitudes using survey instruments developed based on the structural composition of attitudes is problematic, as these instruments may not accurately measure attitudes [ 64 ]. The critical concern regarding the assessment of student attitudes using survey instruments developed based on the structural composition of attitudes requires a more thorough explanation. This is particularly important because relying on instruments that do not align with the multi-dimensional nature of attitudes, encompassing affective, cognitive, and conative components, may lead to inaccurate measurements [ 64 ]. To elaborate further, historical quantitative investigations in physical education pedagogy often utilized instruments such as Kenyon's [ 65 ] or Simon and Smoll's [ 66 ], which might not capture the complete construct of attitude. For instance, Kenyon's instrument conceptualizes physical activity rather than attitude as a multidimensional construct, while Simon and Smoll's instrument, developed for adults, may not be entirely valid for children. This unidimensional perspective on attitude, focusing solely on the affective dimension, is problematic, as it overlooks the multi-component nature of attitude, as acknowledged in studies by Gonzàles [ 67 ], Mohsin [ 68 ], and Oppenheim [ 69 ]. Therefore, future research endeavors should delve into the intricacies of attitude assessment tools, considering the developmental differences and the multidimensional nature of attitudes to ensure comprehensive and accurate measurement in the context of physical education pedagogy.