Literary Criticism

- Introduction

- Literary Theories

- Steps to Literary Criticism

- Find Resources

- Cite Sources

- thesis examples

SAMPLE THESIS STATEMENTS

These sample thesis statements are provided as guides, not as required forms or prescriptions.

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________

The thesis may focus on an analysis of one of the elements of fiction, drama, poetry or nonfiction as expressed in the work: character, plot, structure, idea, theme, symbol, style, imagery, tone, etc.

In “A Worn Path,” Eudora Welty creates a fictional character in Phoenix Jackson whose determination, faith, and cunning illustrate the indomitable human spirit.

Note that the work, author, and character to be analyzed are identified in this thesis statement. The thesis relies on a strong verb (creates). It also identifies the element of fiction that the writer will explore (character) and the characteristics the writer will analyze and discuss (determination, faith, cunning).

Further Examples:

The character of the Nurse in Romeo and Juliet serves as a foil to young Juliet, delights us with her warmth and earthy wit, and helps realize the tragic catastrophe.

The works of ecstatic love poets Rumi, Hafiz, and Kabir use symbols such as a lover’s longing and the Tavern of Ruin to illustrate the human soul’s desire to connect with God.

The thesis may focus on illustrating how a work reflects the particular genre’s forms, the characteristics of a philosophy of literature, or the ideas of a particular school of thought.

“The Third and Final Continent” exhibits characteristics recurrent in writings by immigrants: tradition, adaptation, and identity.

Note how the thesis statement classifies the form of the work (writings by immigrants) and identifies the characteristics of that form of writing (tradition, adaptation, and identity) that the essay will discuss.

Further examples:

Samuel Beckett’s Endgame reflects characteristics of Theatre of the Absurd in its minimalist stage setting, its seemingly meaningless dialogue, and its apocalyptic or nihilist vision.

A close look at many details in “The Story of an Hour” reveals how language, institutions, and expected demeanor suppress the natural desires and aspirations of women.

The thesis may draw parallels between some element in the work and real-life situations or subject matter: historical events, the author’s life, medical diagnoses, etc.

In Willa Cather’s short story, “Paul’s Case,” Paul exhibits suicidal behavior that a caring adult might have recognized and remedied had that adult had the scientific knowledge we have today.

This thesis suggests that the essay will identify characteristics of suicide that Paul exhibits in the story. The writer will have to research medical and psychology texts to determine the typical characteristics of suicidal behavior and to illustrate how Paul’s behavior mirrors those characteristics.

Through the experience of one man, the Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, An American Slave, accurately depicts the historical record of slave life in its descriptions of the often brutal and quixotic relationship between master and slave and of the fragmentation of slave families.

In “I Stand Here Ironing,” one can draw parallels between the narrator’s situation and the author’s life experiences as a mother, writer, and feminist.

SAMPLE PATTERNS FOR THESES ON LITERARY WORKS

1. In (title of work), (author) (illustrates, shows) (aspect) (adjective).

Example: In “Barn Burning,” William Faulkner shows the characters Sardie and Abner Snopes struggling for their identity.

2. In (title of work), (author) uses (one aspect) to (define, strengthen, illustrate) the (element of work).

Example: In “Youth,” Joseph Conrad uses foreshadowing to strengthen the plot.

3. In (title of work), (author) uses (an important part of work) as a unifying device for (one element), (another element), and (another element). The number of elements can vary from one to four.

Example: In “Youth,” Joseph Conrad uses the sea as a unifying device for setting, structure and theme.

4. (Author) develops the character of (character’s name) in (literary work) through what he/she does, what he/she says, what other people say to or about him/her.

Example: Langston Hughes develops the character of Semple in “Ways and Means”…

5. In (title of work), (author) uses (literary device) to (accomplish, develop, illustrate, strengthen) (element of work).

Example: In “The Masque of the Red Death,” Poe uses the symbolism of the stranger, the clock, and the seventh room to develop the theme of death.

6. (Author) (shows, develops, illustrates) the theme of __________ in the (play, poem, story).

Example: Flannery O’Connor illustrates the theme of the effect of the selfishness of the grandmother upon the family in “A Good Man is Hard to Find.”

7. (Author) develops his character(s) in (title of work) through his/her use of language.

Example: John Updike develops his characters in “A & P” through his use of figurative language.

Perimeter College, Georgia State University, http://depts.gpc.edu/~gpcltc/handouts/communications/literarythesis.pdf

- << Previous: Cite Sources

- Next: Get Help >>

- Last Updated: May 10, 2024 3:27 PM

- URL: https://libguides.uta.edu/literarycriticism

University of Texas Arlington Libraries 702 Planetarium Place · Arlington, TX 76019 · 817-272-3000

- Internet Privacy

- Accessibility

- Problems with a guide? Contact Us.

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Developing a Thesis

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

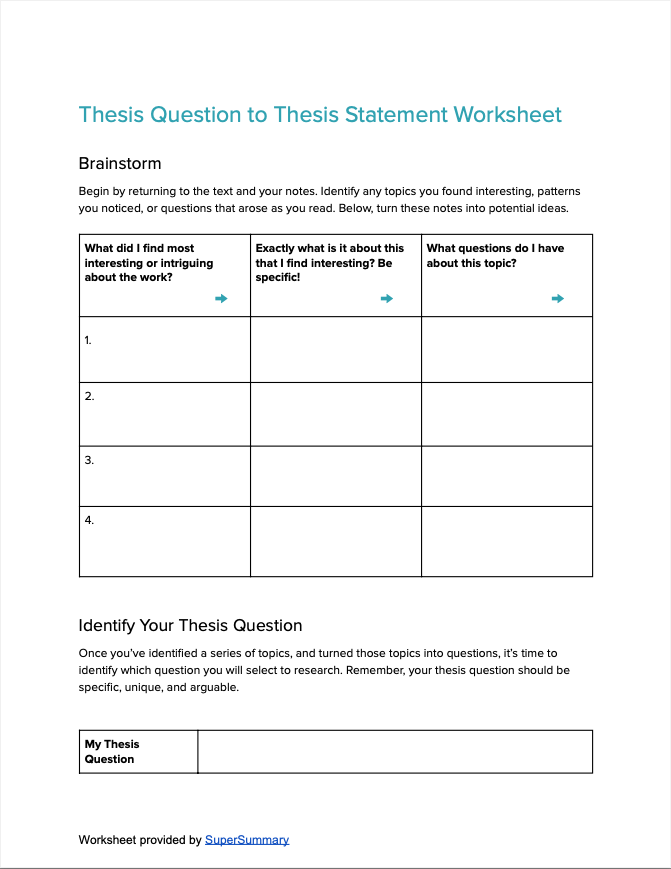

Once you've read the story or novel closely, look back over your notes for patterns of questions or ideas that interest you. Have most of your questions been about the characters, how they develop or change?

For example: If you are reading Conrad's The Secret Agent , do you seem to be most interested in what the author has to say about society? Choose a pattern of ideas and express it in the form of a question and an answer such as the following: Question: What does Conrad seem to be suggesting about early twentieth-century London society in his novel The Secret Agent ? Answer: Conrad suggests that all classes of society are corrupt. Pitfalls: Choosing too many ideas. Choosing an idea without any support.

Once you have some general points to focus on, write your possible ideas and answer the questions that they suggest.

For example: Question: How does Conrad develop the idea that all classes of society are corrupt? Answer: He uses images of beasts and cannibalism whether he's describing socialites, policemen or secret agents.

To write your thesis statement, all you have to do is turn the question and answer around. You've already given the answer, now just put it in a sentence (or a couple of sentences) so that the thesis of your paper is clear.

For example: In his novel, The Secret Agent , Conrad uses beast and cannibal imagery to describe the characters and their relationships to each other. This pattern of images suggests that Conrad saw corruption in every level of early twentieth-century London society.

Now that you're familiar with the story or novel and have developed a thesis statement, you're ready to choose the evidence you'll use to support your thesis. There are a lot of good ways to do this, but all of them depend on a strong thesis for their direction.

For example: Here's a student's thesis about Joseph Conrad's The Secret Agent . In his novel, The Secret Agent , Conrad uses beast and cannibal imagery to describe the characters and their relationships to each other. This pattern of images suggests that Conrad saw corruption in every level of early twentieth-century London society. This thesis focuses on the idea of social corruption and the device of imagery. To support this thesis, you would need to find images of beasts and cannibalism within the text.

Thesis Statements for a Literature Assignment

A thesis prepares the reader for what you are about to say. As such, your paper needs to be interesting in order for your thesis to be interesting. Your thesis needs to be interesting because it needs to capture a reader's attention. If a reader looks at your thesis and says "so what?", your thesis has failed to do its job, and chances are your paper has as well. Thus, make your thesis provocative and open to reasonable disagreement, but then write persuasively enough to sway those who might be disagree.

Keep in mind the following when formulating a thesis:

- A Thesis Should Not State the Obvious

- Use Literary Terms in Thesis With Care

- A Thesis Should be Balanced

- A Thesis Can be a Blueprint

Avoid the Obvious

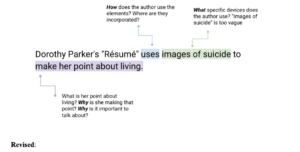

Bland: Dorothy Parker's "Résumé" uses images of suicide to make her point about living.

This is bland because it's obvious and incontestable. A reader looks at it and says, "so what?"

However, consider this alternative:

Dorothy Parker's "Résumé" doesn't celebrate life, but rather scorns those who would fake or attempt suicide just to get attention.

The first thesis merely describes something about the poem; the second tells the reader what the writer thinks the poem is about--it offers a reading or interpretation. The paper would need to support that reading and would very likely examine the way Parker uses images of suicide to make the point the writer claims.

Use Literary Terms in Thesis Only to Make Larger Points

Poems and novels generally use rhyme, meter, imagery, simile, metaphor, stanzas, characters, themes, settings and so on. While these terms are important for you to use in your analysis and your arguments, that they exist in the work you are writing about should not be the main point of your thesis. Unless the poet or novelist uses these elements in some unexpected way to shape the work's meaning, it's generally a good idea not to draw attention to the use of literary devices in thesis statements because an intelligent reader expects a poem or novel to use literary of these elements. Therefore, a thesis that only says a work uses literary devices isn't a good thesis because all it is doing is stating the obvious, leading the reader to say, "so what?"

However, you can use literary terms in a thesis if the purpose is to explain how the terms contribute to the work's meaning or understanding. Here's an example of thesis statement that does call attention to literary devices because they are central to the paper's argument. Literary terms are placed in italics.

Don Marquis introduced Archy and Mehitabel in his Sun Dial column by combining the conventions of free verse poetry with newspaper prose so intimately that in "the coming of Archy," the entire column represents a complete poem and not a free verse poem preceded by a prose introduction .

Note the difference between this thesis and the first bland thesis on the Parker poem. This thesis does more than say certain literary devices exist in the poem; it argues that they exist in a specific relationship to one another and makes a fairly startling claim, one that many would disagree with and one that the writer will need to persuade her readers on.

Keep Your Thesis Balanced

Keep the thesis balanced. If it's too general, it becomes vague; if it's too specific, it cannot be developed. If it's merely descriptive (like the bland example above), it gives the reader no compelling reason to go on. The thesis should be dramatic, have some tension in it, and should need to be proved (another reason for avoiding the obvious).

Too general: Edna St. Vincent Millay wrote many poems with love as the theme. Too specific: Edna St. Vincent Millay wrote "Love is not all: it is not meat nor drink" in <insert date> after <insert event from her life>. Too descriptive: Edna St. Vincent Millay's "Love is not all: it is not meat nor drink" is a sonnet with two parts; the first six lines propose a view of love and the next eight complicate that view. With tension and which will need proving: Despite her avowal on the importance of love, and despite her belief that she would not sell her love, the speaker in Edna St. Vincent Millay's "Love is not all: it is not meat nor drink" remains unconvinced and bitter, as if she is trying to trick herself into believing that love really does matter for more than the one night she is in some lover's arms.

Your Thesis Can Be A Blueprint

A thesis can be used as roadmap or blueprint for your paper:

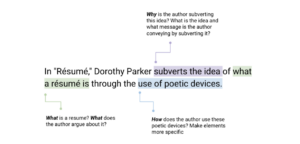

In "Résumé," Dorothy Parker subverts the idea of what a résumé is--accomplishments and experiences--with an ironic tone, silly images of suicide, and witty rhymes to point out the banality of life for those who remain too disengaged from it.

Note that while this thesis refers to particular poetic devices, it does so in a way that gets beyond merely saying there are poetic devices in the poem and then merely describing them. It makes a claim as to how and why the poet uses tone, imagery and rhyme.

Readers would expect you to argue that Parker subverts the idea of the résumé to critique bored (and boring) people; they would expect your argument to do so by analyzing her use of tone, imagery and rhyme in that order.

Citation Information

Nick Carbone. (1994-2024). Thesis Statements for a Literature Assignment. The WAC Clearinghouse. Colorado State University. Available at https://wac.colostate.edu/repository/writing/guides/.

Copyright Information

Copyright © 1994-2024 Colorado State University and/or this site's authors, developers, and contributors . Some material displayed on this site is used with permission.

Thesis Statements

What this handout is about.

This handout describes what a thesis statement is, how thesis statements work in your writing, and how you can craft or refine one for your draft.

Introduction

Writing in college often takes the form of persuasion—convincing others that you have an interesting, logical point of view on the subject you are studying. Persuasion is a skill you practice regularly in your daily life. You persuade your roommate to clean up, your parents to let you borrow the car, your friend to vote for your favorite candidate or policy. In college, course assignments often ask you to make a persuasive case in writing. You are asked to convince your reader of your point of view. This form of persuasion, often called academic argument, follows a predictable pattern in writing. After a brief introduction of your topic, you state your point of view on the topic directly and often in one sentence. This sentence is the thesis statement, and it serves as a summary of the argument you’ll make in the rest of your paper.

What is a thesis statement?

A thesis statement:

- tells the reader how you will interpret the significance of the subject matter under discussion.

- is a road map for the paper; in other words, it tells the reader what to expect from the rest of the paper.

- directly answers the question asked of you. A thesis is an interpretation of a question or subject, not the subject itself. The subject, or topic, of an essay might be World War II or Moby Dick; a thesis must then offer a way to understand the war or the novel.

- makes a claim that others might dispute.

- is usually a single sentence near the beginning of your paper (most often, at the end of the first paragraph) that presents your argument to the reader. The rest of the paper, the body of the essay, gathers and organizes evidence that will persuade the reader of the logic of your interpretation.

If your assignment asks you to take a position or develop a claim about a subject, you may need to convey that position or claim in a thesis statement near the beginning of your draft. The assignment may not explicitly state that you need a thesis statement because your instructor may assume you will include one. When in doubt, ask your instructor if the assignment requires a thesis statement. When an assignment asks you to analyze, to interpret, to compare and contrast, to demonstrate cause and effect, or to take a stand on an issue, it is likely that you are being asked to develop a thesis and to support it persuasively. (Check out our handout on understanding assignments for more information.)

How do I create a thesis?

A thesis is the result of a lengthy thinking process. Formulating a thesis is not the first thing you do after reading an essay assignment. Before you develop an argument on any topic, you have to collect and organize evidence, look for possible relationships between known facts (such as surprising contrasts or similarities), and think about the significance of these relationships. Once you do this thinking, you will probably have a “working thesis” that presents a basic or main idea and an argument that you think you can support with evidence. Both the argument and your thesis are likely to need adjustment along the way.

Writers use all kinds of techniques to stimulate their thinking and to help them clarify relationships or comprehend the broader significance of a topic and arrive at a thesis statement. For more ideas on how to get started, see our handout on brainstorming .

How do I know if my thesis is strong?

If there’s time, run it by your instructor or make an appointment at the Writing Center to get some feedback. Even if you do not have time to get advice elsewhere, you can do some thesis evaluation of your own. When reviewing your first draft and its working thesis, ask yourself the following :

- Do I answer the question? Re-reading the question prompt after constructing a working thesis can help you fix an argument that misses the focus of the question. If the prompt isn’t phrased as a question, try to rephrase it. For example, “Discuss the effect of X on Y” can be rephrased as “What is the effect of X on Y?”

- Have I taken a position that others might challenge or oppose? If your thesis simply states facts that no one would, or even could, disagree with, it’s possible that you are simply providing a summary, rather than making an argument.

- Is my thesis statement specific enough? Thesis statements that are too vague often do not have a strong argument. If your thesis contains words like “good” or “successful,” see if you could be more specific: why is something “good”; what specifically makes something “successful”?

- Does my thesis pass the “So what?” test? If a reader’s first response is likely to be “So what?” then you need to clarify, to forge a relationship, or to connect to a larger issue.

- Does my essay support my thesis specifically and without wandering? If your thesis and the body of your essay do not seem to go together, one of them has to change. It’s okay to change your working thesis to reflect things you have figured out in the course of writing your paper. Remember, always reassess and revise your writing as necessary.

- Does my thesis pass the “how and why?” test? If a reader’s first response is “how?” or “why?” your thesis may be too open-ended and lack guidance for the reader. See what you can add to give the reader a better take on your position right from the beginning.

Suppose you are taking a course on contemporary communication, and the instructor hands out the following essay assignment: “Discuss the impact of social media on public awareness.” Looking back at your notes, you might start with this working thesis:

Social media impacts public awareness in both positive and negative ways.

You can use the questions above to help you revise this general statement into a stronger thesis.

- Do I answer the question? You can analyze this if you rephrase “discuss the impact” as “what is the impact?” This way, you can see that you’ve answered the question only very generally with the vague “positive and negative ways.”

- Have I taken a position that others might challenge or oppose? Not likely. Only people who maintain that social media has a solely positive or solely negative impact could disagree.

- Is my thesis statement specific enough? No. What are the positive effects? What are the negative effects?

- Does my thesis pass the “how and why?” test? No. Why are they positive? How are they positive? What are their causes? Why are they negative? How are they negative? What are their causes?

- Does my thesis pass the “So what?” test? No. Why should anyone care about the positive and/or negative impact of social media?

After thinking about your answers to these questions, you decide to focus on the one impact you feel strongly about and have strong evidence for:

Because not every voice on social media is reliable, people have become much more critical consumers of information, and thus, more informed voters.

This version is a much stronger thesis! It answers the question, takes a specific position that others can challenge, and it gives a sense of why it matters.

Let’s try another. Suppose your literature professor hands out the following assignment in a class on the American novel: Write an analysis of some aspect of Mark Twain’s novel Huckleberry Finn. “This will be easy,” you think. “I loved Huckleberry Finn!” You grab a pad of paper and write:

Mark Twain’s Huckleberry Finn is a great American novel.

You begin to analyze your thesis:

- Do I answer the question? No. The prompt asks you to analyze some aspect of the novel. Your working thesis is a statement of general appreciation for the entire novel.

Think about aspects of the novel that are important to its structure or meaning—for example, the role of storytelling, the contrasting scenes between the shore and the river, or the relationships between adults and children. Now you write:

In Huckleberry Finn, Mark Twain develops a contrast between life on the river and life on the shore.

- Do I answer the question? Yes!

- Have I taken a position that others might challenge or oppose? Not really. This contrast is well-known and accepted.

- Is my thesis statement specific enough? It’s getting there–you have highlighted an important aspect of the novel for investigation. However, it’s still not clear what your analysis will reveal.

- Does my thesis pass the “how and why?” test? Not yet. Compare scenes from the book and see what you discover. Free write, make lists, jot down Huck’s actions and reactions and anything else that seems interesting.

- Does my thesis pass the “So what?” test? What’s the point of this contrast? What does it signify?”

After examining the evidence and considering your own insights, you write:

Through its contrasting river and shore scenes, Twain’s Huckleberry Finn suggests that to find the true expression of American democratic ideals, one must leave “civilized” society and go back to nature.

This final thesis statement presents an interpretation of a literary work based on an analysis of its content. Of course, for the essay itself to be successful, you must now present evidence from the novel that will convince the reader of your interpretation.

Works consulted

We consulted these works while writing this handout. This is not a comprehensive list of resources on the handout’s topic, and we encourage you to do your own research to find additional publications. Please do not use this list as a model for the format of your own reference list, as it may not match the citation style you are using. For guidance on formatting citations, please see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial . We revise these tips periodically and welcome feedback.

Anson, Chris M., and Robert A. Schwegler. 2010. The Longman Handbook for Writers and Readers , 6th ed. New York: Longman.

Lunsford, Andrea A. 2015. The St. Martin’s Handbook , 8th ed. Boston: Bedford/St Martin’s.

Ramage, John D., John C. Bean, and June Johnson. 2018. The Allyn & Bacon Guide to Writing , 8th ed. New York: Pearson.

Ruszkiewicz, John J., Christy Friend, Daniel Seward, and Maxine Hairston. 2010. The Scott, Foresman Handbook for Writers , 9th ed. Boston: Pearson Education.

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout and attribute the source: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Make a Gift

How to Write an Effective Literary Analysis Thesis Statement

Center for writing excellence blog.

Cailey Rogers is a class of 2024 Writing Center consultant. She is studying Journalism and English Literature. At Elon, she is a Communications Fellow and is involved in Elon Learning Assistance, Colonnades Literary and Art Journal, and the Pendulum.

I distinctly remember that when I was in middle school and just beginning to learn how to write essays, the most daunting task was crafting a thesis statement. Back then, my teachers would put so much emphasis on one part of the entire paper; now that I’m in college, I understand why.

Writing a thesis statement hasn’t become easier over time for me. In fact, now that I am writing complex papers for my 3000-level classes, it has proved to be even more challenging. But honestly, I have come to appreciate this part of a paper to the point where I cannot write the body paragraphs of my work until I am satisfied with the thesis statement.

As an English Literature major, I most look forward to writing thesis statements for literary analysis essays. But I realize that the idea of writing a long analysis on a piece of literature is not fun for everyone. Well, I’m going to offer some suggestions and advice to anyone tackling a literary analysis paper – whether this is your first time writing one, or you’ve been doing it for years, these thesis statement tips will give you a roadmap to creating a thesis that will not just start your paper off on the right note, but also display your writing skills and critical thinking. If you have a strong thesis, I guarantee that your paper will be more sophisticated and easier to write. While my focus here in on literary analysis, my tips apply to anyone writing an analysis and interpretation of a text.

Like any thesis statement, a literary analysis thesis should work as both a roadmap and a foundation for your essay. As the Writing Center at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill advises, the thesis statement should do more than illuminate how you are going to “interpret the significance of the subject matter under discussion;” it should also give the reader an outline of the paper itself. This means you need to state what topic you want to focus on, what specific details you will use as textual evidence, and why your argument is important. If you draw a clear map and build a sturdy foundation, the rest of your analysis can grow to be much stronger as a whole.

Let’s break down an example that may make this point a little easier to digest. Here is a practice thesis statement from the WAC Clearinghouse that distinguishes between a vague thesis and one that provides a detailed blueprint for the paper:

Another valuable piece of advice is to make sure not to state the obvious in your thesis statements. In addition to thinking of your thesis statement as a map or a foundation, think of it also as a hook. You want your readers to be interested in what you have to say, so make your thesis statement compelling enough so that a reader simply can’t resist reading the rest of the paper.

Here is another example from the WAC Clearinghouse on how to accomplish this feat:

Note: To learn more about the “what,” “how,” and “why” aspects highlighted in these examples, check out the second blog post in this series, where I discuss my own personal process when writing a literary analysis thesis statement here!

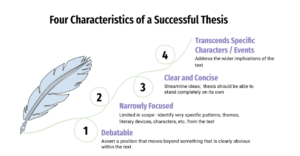

Now, these may seem like pretty standard suggestions that would work for all kinds of thesis statements across a variety of fields. And they are. That doesn’t mean they aren’t important to keep in mind, though. But I did come prepared with some suggestions that are specific to writing a literary analysis essay that I have learned from Dr. Janet Myers, Professor of English in the English Department at Elon University. I’ve taken several classes with Dr. Myers, written countless literary analysis papers, and these four simple characteristics to include in a thesis statement have gotten me through each one. According to Dr. Myers, these are the four characteristics of a successful thesis statement:

By this, I mean that you want to assert a position that moves beyond something that is clearly obvious within the text. More specifically, you are going to want to isolate a subject you can explore with your own voice. You don’t want to merely point out that a theme of pattern exists in a text; you want to argue about its meaning or purpose. Think of everything you write as being a contribution to a big conversation of scholars. What do you want to contribute to this conversation? You don’t want it to be just an observation but rather an argument that you can support and defend.

2. Narrowly Focused

Even though you do want to address some universal and pervading aspects of the text you are analyzing, you definitely don’t want to overburden yourself. The broader your thesis is, the more you would be required to explain, and the harder it would be for your audience to understand the particulars of your argument. So, make your thesis statement limited in scope. Identify a specific pattern, theme, literary device, character, or historical event (and there are certainly more possibilities) from the text that you want to analyze in your paper. This is where you could build the roadmap aspect of the thesis: list the elements in the order you will write about them in, and suddenly you will have a clear path for entire literary analysis.

3. Clear and Concise

This may seem obvious, but it is crucial. A clear thesis will play into the idea of a roadmap, but it will also avoid using long, complex clauses or unnecessary jargon. In terms of making it concise, look for any words in your thesis that may not add to the overall point you are trying to make, and cut them out. Streamline your thesis statement by simplifying your ideas as much as you can, almost as if you were trying to explain it to someone who has never read the text before. Ultimately, your thesis should be able to stand completely on its own. If you just gave your professor your thesis statement and left out the rest of your paper, your topic, evidence, and argument should all be transparent and evident.

4. Capable of Transcending Specific Characters and Events in the Text

This one is particularly important to keep in mind for a literary analysis paper. What makes a strong literary analysis is an argument that isn’t limited to one specific plot point or character within the text. Think of it this way: pretend you are trying to convince a friend that they should take up reading as a hobby because it is entertaining and enriching. But the only evidence you have to back this up is that you really enjoyed reading one book in the past month. Obviously, that is never going to convince your friend to take up reading because that argument only pertains to one person’s experience at a singular point in time. You would want to have more examples of how reading has changed people’s lives across the world, not just you. Also, you would probably want to address some of the larger persuasive arguments like how literature increases the value of an education, or how it can teach you about a variety of different topics. You would do the same thing in a literary analysis paper: you would want to address the wider implications of the text and find patterns or themes that pertain to more than one specific event or character. Challenge yourself to find connections between events and characters, and then trace those connections in your writing. But even more than that, try to find a universally significant message that your text represents. Literature is a reflection of reality, so find out what your text is trying to express about the real world, and then write about it.

I know it can seem intimidating to write a literary analysis paper, but if you follow these tips when writing your thesis, the challenge will suddenly seem much less impossible. If you want to continue learning about writing a successful literary analysis thesis statement, you can find another blog post I wrote about my personal process and tips by clicking on this link. And if you still find yourself doubting your work, you can always come to The Writing Center, and we would be happy to help you!

One response to “How to Write an Effective Literary Analysis Thesis Statement”

[…] In my short time at Elon, I have found that the most challenging and rewarding part of writing a long literary analysis paper is the thesis statement. It’s funny how just one small portion of what can become an eight-page essay seems impossible to accomplish. If you feel that way, you are certainly not alone. Even English majors struggle with it – I can say that from personal experience! That is exactly why I decided to share the tips and processes that have helped me the most when writing a literary analysis thesis statement in hopes that it could help others staring at a blank document, not knowing where to start or feeling like they will never be able to write a good paper about a piece of literature. If you want to know some of the general tips and tricks that I have acquired through my English classes and some other resources, you can read my first blog post here. […]

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Thesis Statements for a Literature Assignment

A thesis prepares the reader for what you are about to say. As such, your paper needs to be interesting in order for your thesis to be interesting. Your thesis needs to be interesting because it needs to capture a reader's attention. If a reader looks at your thesis and says "so what?", your thesis has failed to do its job, and chances are your paper has as well. Thus, make your thesis provocative and open to reasonable disagreement, but then write persuasively enough to sway those who might be disagree.

Keep in mind the following when formulating a thesis:

- A Thesis Should Not State the Obvious

- Use Literary Terms in Thesis With Care

- A Thesis Should be Balanced

- A Thesis Can be a Blueprint

Avoid the Obvious

Bland: Dorothy Parker's "Résumé" uses images of suicide to make her point about living.

This is bland because it's obvious and incontestable. A reader looks at it and says, "so what?"

However, consider this alternative:

Dorothy Parker's "Résumé" doesn't celebrate life, but rather scorns those who would fake or attempt suicide just to get attention.

The first thesis merely describes something about the poem; the second tells the reader what the writer thinks the poem is about--it offers a reading or interpretation. The paper would need to support that reading and would very likely examine the way Parker uses images of suicide to make the point the writer claims.

Use Literary Terms in Thesis Only to Make Larger Points

Poems and novels generally use rhyme, meter, imagery, simile, metaphor, stanzas, characters, themes, settings and so on. While these terms are important for you to use in your analysis and your arguments, that they exist in the work you are writing about should not be the main point of your thesis. Unless the poet or novelist uses these elements in some unexpected way to shape the work's meaning, it's generally a good idea not to draw attention to the use of literary devices in thesis statements because an intelligent reader expects a poem or novel to use literary of these elements. Therefore, a thesis that only says a work uses literary devices isn't a good thesis because all it is doing is stating the obvious, leading the reader to say, "so what?"

However, you can use literary terms in a thesis if the purpose is to explain how the terms contribute to the work's meaning or understanding. Here's an example of thesis statement that does call attention to literary devices because they are central to the paper's argument. Literary terms are placed in italics.

Don Marquis introduced Archy and Mehitabel in his Sun Dial column by combining the conventions of free verse poetry with newspaper prose so intimately that in "the coming of Archy," the entire column represents a complete poem and not a free verse poem preceded by a prose introduction .

Note the difference between this thesis and the first bland thesis on the Parker poem. This thesis does more than say certain literary devices exist in the poem; it argues that they exist in a specific relationship to one another and makes a fairly startling claim, one that many would disagree with and one that the writer will need to persuade her readers on.

Keep Your Thesis Balanced

Keep the thesis balanced. If it's too general, it becomes vague; if it's too specific, it cannot be developed. If it's merely descriptive (like the bland example above), it gives the reader no compelling reason to go on. The thesis should be dramatic, have some tension in it, and should need to be proved (another reason for avoiding the obvious).

Too general: Edna St. Vincent Millay wrote many poems with love as the theme. Too specific: Edna St. Vincent Millay wrote "Love is not all: it is not meat nor drink" in <insert date> after <insert event from her life>. Too descriptive: Edna St. Vincent Millay's "Love is not all: it is not meat nor drink" is a sonnet with two parts; the first six lines propose a view of love and the next eight complicate that view. With tension and which will need proving: Despite her avowal on the importance of love, and despite her belief that she would not sell her love, the speaker in Edna St. Vincent Millay's "Love is not all: it is not meat nor drink" remains unconvinced and bitter, as if she is trying to trick herself into believing that love really does matter for more than the one night she is in some lover's arms.

Your Thesis Can Be A Blueprint

A thesis can be used as roadmap or blueprint for your paper:

In "Résumé," Dorothy Parker subverts the idea of what a résumé is--accomplishments and experiences--with an ironic tone, silly images of suicide, and witty rhymes to point out the banality of life for those who remain too disengaged from it.

Note that while this thesis refers to particular poetic devices, it does so in a way that gets beyond merely saying there are poetic devices in the poem and then merely describing them. It makes a claim as to how and why the poet uses tone, imagery and rhyme.

Readers would expect you to argue that Parker subverts the idea of the résumé to critique bored (and boring) people; they would expect your argument to do so by analyzing her use of tone, imagery and rhyme in that order.

Carbone, Nick. (1997). Thesis Statements for a Literature Assignment. Writing@CSU . Colorado State University. https://writing.colostate.edu/guides/guide.cfm?guideid=51

beginner's guide to literary analysis

Understanding literature & how to write literary analysis.

Literary analysis is the foundation of every college and high school English class. Once you can comprehend written work and respond to it, the next step is to learn how to think critically and complexly about a work of literature in order to analyze its elements and establish ideas about its meaning.

If that sounds daunting, it shouldn’t. Literary analysis is really just a way of thinking creatively about what you read. The practice takes you beyond the storyline and into the motives behind it.

While an author might have had a specific intention when they wrote their book, there’s still no right or wrong way to analyze a literary text—just your way. You can use literary theories, which act as “lenses” through which you can view a text. Or you can use your own creativity and critical thinking to identify a literary device or pattern in a text and weave that insight into your own argument about the text’s underlying meaning.

Now, if that sounds fun, it should , because it is. Here, we’ll lay the groundwork for performing literary analysis, including when writing analytical essays, to help you read books like a critic.

What Is Literary Analysis?

As the name suggests, literary analysis is an analysis of a work, whether that’s a novel, play, short story, or poem. Any analysis requires breaking the content into its component parts and then examining how those parts operate independently and as a whole. In literary analysis, those parts can be different devices and elements—such as plot, setting, themes, symbols, etcetera—as well as elements of style, like point of view or tone.

When performing analysis, you consider some of these different elements of the text and then form an argument for why the author chose to use them. You can do so while reading and during class discussion, but it’s particularly important when writing essays.

Literary analysis is notably distinct from summary. When you write a summary , you efficiently describe the work’s main ideas or plot points in order to establish an overview of the work. While you might use elements of summary when writing analysis, you should do so minimally. You can reference a plot line to make a point, but it should be done so quickly so you can focus on why that plot line matters . In summary (see what we did there?), a summary focuses on the “ what ” of a text, while analysis turns attention to the “ how ” and “ why .”

While literary analysis can be broad, covering themes across an entire work, it can also be very specific, and sometimes the best analysis is just that. Literary critics have written thousands of words about the meaning of an author’s single word choice; while you might not want to be quite that particular, there’s a lot to be said for digging deep in literary analysis, rather than wide.

Although you’re forming your own argument about the work, it’s not your opinion . You should avoid passing judgment on the piece and instead objectively consider what the author intended, how they went about executing it, and whether or not they were successful in doing so. Literary criticism is similar to literary analysis, but it is different in that it does pass judgement on the work. Criticism can also consider literature more broadly, without focusing on a singular work.

Once you understand what constitutes (and doesn’t constitute) literary analysis, it’s easy to identify it. Here are some examples of literary analysis and its oft-confused counterparts:

Summary: In “The Fall of the House of Usher,” the narrator visits his friend Roderick Usher and witnesses his sister escape a horrible fate.

Opinion: In “The Fall of the House of Usher,” Poe uses his great Gothic writing to establish a sense of spookiness that is enjoyable to read.

Literary Analysis: “Throughout ‘The Fall of the House of Usher,’ Poe foreshadows the fate of Madeline by creating a sense of claustrophobia for the reader through symbols, such as in the narrator’s inability to leave and the labyrinthine nature of the house.

In summary, literary analysis is:

- Breaking a work into its components

- Identifying what those components are and how they work in the text

- Developing an understanding of how they work together to achieve a goal

- Not an opinion, but subjective

- Not a summary, though summary can be used in passing

- Best when it deeply, rather than broadly, analyzes a literary element

Literary Analysis and Other Works

As discussed above, literary analysis is often performed upon a single work—but it doesn’t have to be. It can also be performed across works to consider the interplay of two or more texts. Regardless of whether or not the works were written about the same thing, or even within the same time period, they can have an influence on one another or a connection that’s worth exploring. And reading two or more texts side by side can help you to develop insights through comparison and contrast.

For example, Paradise Lost is an epic poem written in the 17th century, based largely on biblical narratives written some 700 years before and which later influenced 19th century poet John Keats. The interplay of works can be obvious, as here, or entirely the inspiration of the analyst. As an example of the latter, you could compare and contrast the writing styles of Ralph Waldo Emerson and Edgar Allan Poe who, while contemporaries in terms of time, were vastly different in their content.

Additionally, literary analysis can be performed between a work and its context. Authors are often speaking to the larger context of their times, be that social, political, religious, economic, or artistic. A valid and interesting form is to compare the author’s context to the work, which is done by identifying and analyzing elements that are used to make an argument about the writer’s time or experience.

For example, you could write an essay about how Hemingway’s struggles with mental health and paranoia influenced his later work, or how his involvement in the Spanish Civil War influenced his early work. One approach focuses more on his personal experience, while the other turns to the context of his times—both are valid.

Why Does Literary Analysis Matter?

Sometimes an author wrote a work of literature strictly for entertainment’s sake, but more often than not, they meant something more. Whether that was a missive on world peace, commentary about femininity, or an allusion to their experience as an only child, the author probably wrote their work for a reason, and understanding that reason—or the many reasons—can actually make reading a lot more meaningful.

Performing literary analysis as a form of study unquestionably makes you a better reader. It’s also likely that it will improve other skills, too, like critical thinking, creativity, debate, and reasoning.

At its grandest and most idealistic, literary analysis even has the ability to make the world a better place. By reading and analyzing works of literature, you are able to more fully comprehend the perspectives of others. Cumulatively, you’ll broaden your own perspectives and contribute more effectively to the things that matter to you.

Literary Terms to Know for Literary Analysis

There are hundreds of literary devices you could consider during your literary analysis, but there are some key tools most writers utilize to achieve their purpose—and therefore you need to know in order to understand that purpose. These common devices include:

- Characters: The people (or entities) who play roles in the work. The protagonist is the main character in the work.

- Conflict: The conflict is the driving force behind the plot, the event that causes action in the narrative, usually on the part of the protagonist

- Context : The broader circumstances surrounding the work political and social climate in which it was written or the experience of the author. It can also refer to internal context, and the details presented by the narrator

- Diction : The word choice used by the narrator or characters

- Genre: A category of literature characterized by agreed upon similarities in the works, such as subject matter and tone

- Imagery : The descriptive or figurative language used to paint a picture in the reader’s mind so they can picture the story’s plot, characters, and setting

- Metaphor: A figure of speech that uses comparison between two unlike objects for dramatic or poetic effect

- Narrator: The person who tells the story. Sometimes they are a character within the story, but sometimes they are omniscient and removed from the plot.

- Plot : The storyline of the work

- Point of view: The perspective taken by the narrator, which skews the perspective of the reader

- Setting : The time and place in which the story takes place. This can include elements like the time period, weather, time of year or day, and social or economic conditions

- Symbol : An object, person, or place that represents an abstract idea that is greater than its literal meaning

- Syntax : The structure of a sentence, either narration or dialogue, and the tone it implies

- Theme : A recurring subject or message within the work, often commentary on larger societal or cultural ideas

- Tone : The feeling, attitude, or mood the text presents

How to Perform Literary Analysis

Step 1: read the text thoroughly.

Literary analysis begins with the literature itself, which means performing a close reading of the text. As you read, you should focus on the work. That means putting away distractions (sorry, smartphone) and dedicating a period of time to the task at hand.

It’s also important that you don’t skim or speed read. While those are helpful skills, they don’t apply to literary analysis—or at least not this stage.

Step 2: Take Notes as You Read

As you read the work, take notes about different literary elements and devices that stand out to you. Whether you highlight or underline in text, use sticky note tabs to mark pages and passages, or handwrite your thoughts in a notebook, you should capture your thoughts and the parts of the text to which they correspond. This—the act of noticing things about a literary work—is literary analysis.

Step 3: Notice Patterns

As you read the work, you’ll begin to notice patterns in the way the author deploys language, themes, and symbols to build their plot and characters. As you read and these patterns take shape, begin to consider what they could mean and how they might fit together.

As you identify these patterns, as well as other elements that catch your interest, be sure to record them in your notes or text. Some examples include:

- Circle or underline words or terms that you notice the author uses frequently, whether those are nouns (like “eyes” or “road”) or adjectives (like “yellow” or “lush”).

- Highlight phrases that give you the same kind of feeling. For example, if the narrator describes an “overcast sky,” a “dreary morning,” and a “dark, quiet room,” the words aren’t the same, but the feeling they impart and setting they develop are similar.

- Underline quotes or prose that define a character’s personality or their role in the text.

- Use sticky tabs to color code different elements of the text, such as specific settings or a shift in the point of view.

By noting these patterns, comprehensive symbols, metaphors, and ideas will begin to come into focus.

Step 4: Consider the Work as a Whole, and Ask Questions

This is a step that you can do either as you read, or after you finish the text. The point is to begin to identify the aspects of the work that most interest you, and you could therefore analyze in writing or discussion.

Questions you could ask yourself include:

- What aspects of the text do I not understand?

- What parts of the narrative or writing struck me most?

- What patterns did I notice?

- What did the author accomplish really well?

- What did I find lacking?

- Did I notice any contradictions or anything that felt out of place?

- What was the purpose of the minor characters?

- What tone did the author choose, and why?

The answers to these and more questions will lead you to your arguments about the text.

Step 5: Return to Your Notes and the Text for Evidence

As you identify the argument you want to make (especially if you’re preparing for an essay), return to your notes to see if you already have supporting evidence for your argument. That’s why it’s so important to take notes or mark passages as you read—you’ll thank yourself later!

If you’re preparing to write an essay, you’ll use these passages and ideas to bolster your argument—aka, your thesis. There will likely be multiple different passages you can use to strengthen multiple different aspects of your argument. Just be sure to cite the text correctly!

If you’re preparing for class, your notes will also be invaluable. When your teacher or professor leads the conversation in the direction of your ideas or arguments, you’ll be able to not only proffer that idea but back it up with textual evidence. That’s an A+ in class participation.

Step 6: Connect These Ideas Across the Narrative

Whether you’re in class or writing an essay, literary analysis isn’t complete until you’ve considered the way these ideas interact and contribute to the work as a whole. You can find and present evidence, but you still have to explain how those elements work together and make up your argument.

How to Write a Literary Analysis Essay

When conducting literary analysis while reading a text or discussing it in class, you can pivot easily from one argument to another (or even switch sides if a classmate or teacher makes a compelling enough argument).

But when writing literary analysis, your objective is to propose a specific, arguable thesis and convincingly defend it. In order to do so, you need to fortify your argument with evidence from the text (and perhaps secondary sources) and an authoritative tone.

A successful literary analysis essay depends equally on a thoughtful thesis, supportive analysis, and presenting these elements masterfully. We’ll review how to accomplish these objectives below.

Step 1: Read the Text. Maybe Read It Again.

Constructing an astute analytical essay requires a thorough knowledge of the text. As you read, be sure to note any passages, quotes, or ideas that stand out. These could serve as the future foundation of your thesis statement. Noting these sections now will help you when you need to gather evidence.

The more familiar you become with the text, the better (and easier!) your essay will be. Familiarity with the text allows you to speak (or in this case, write) to it confidently. If you only skim the book, your lack of rich understanding will be evident in your essay. Alternatively, if you read the text closely—especially if you read it more than once, or at least carefully revisit important passages—your own writing will be filled with insight that goes beyond a basic understanding of the storyline.

Step 2: Brainstorm Potential Topics

Because you took detailed notes while reading the text, you should have a list of potential topics at the ready. Take time to review your notes, highlighting any ideas or questions you had that feel interesting. You should also return to the text and look for any passages that stand out to you.

When considering potential topics, you should prioritize ideas that you find interesting. It won’t only make the whole process of writing an essay more fun, your enthusiasm for the topic will probably improve the quality of your argument, and maybe even your writing. Just like it’s obvious when a topic interests you in a conversation, it’s obvious when a topic interests the writer of an essay (and even more obvious when it doesn’t).

Your topic ideas should also be specific, unique, and arguable. A good way to think of topics is that they’re the answer to fairly specific questions. As you begin to brainstorm, first think of questions you have about the text. Questions might focus on the plot, such as: Why did the author choose to deviate from the projected storyline? Or why did a character’s role in the narrative shift? Questions might also consider the use of a literary device, such as: Why does the narrator frequently repeat a phrase or comment on a symbol? Or why did the author choose to switch points of view each chapter?

Once you have a thesis question , you can begin brainstorming answers—aka, potential thesis statements . At this point, your answers can be fairly broad. Once you land on a question-statement combination that feels right, you’ll then look for evidence in the text that supports your answer (and helps you define and narrow your thesis statement).

For example, after reading “ The Fall of the House of Usher ,” you might be wondering, Why are Roderick and Madeline twins?, Or even: Why does their relationship feel so creepy?” Maybe you noticed (and noted) that the narrator was surprised to find out they were twins, or perhaps you found that the narrator’s tone tended to shift and become more anxious when discussing the interactions of the twins.

Once you come up with your thesis question, you can identify a broad answer, which will become the basis for your thesis statement. In response to the questions above, your answer might be, “Poe emphasizes the close relationship of Roderick and Madeline to foreshadow that their deaths will be close, too.”

Step 3: Gather Evidence

Once you have your topic (or you’ve narrowed it down to two or three), return to the text (yes, again) to see what evidence you can find to support it. If you’re thinking of writing about the relationship between Roderick and Madeline in “The Fall of the House of Usher,” look for instances where they engaged in the text.

This is when your knowledge of literary devices comes in clutch. Carefully study the language around each event in the text that might be relevant to your topic. How does Poe’s diction or syntax change during the interactions of the siblings? How does the setting reflect or contribute to their relationship? What imagery or symbols appear when Roderick and Madeline are together?

By finding and studying evidence within the text, you’ll strengthen your topic argument—or, just as valuably, discount the topics that aren’t strong enough for analysis.

Step 4: Consider Secondary Sources

In addition to returning to the literary work you’re studying for evidence, you can also consider secondary sources that reference or speak to the work. These can be articles from journals you find on JSTOR, books that consider the work or its context, or articles your teacher shared in class.

While you can use these secondary sources to further support your idea, you should not overuse them. Make sure your topic remains entirely differentiated from that presented in the source.

Step 5: Write a Working Thesis Statement

Once you’ve gathered evidence and narrowed down your topic, you’re ready to refine that topic into a thesis statement. As you continue to outline and write your paper, this thesis statement will likely change slightly, but this initial draft will serve as the foundation of your essay. It’s like your north star: Everything you write in your essay is leading you back to your thesis.

Writing a great thesis statement requires some real finesse. A successful thesis statement is:

- Debatable : You shouldn’t simply summarize or make an obvious statement about the work. Instead, your thesis statement should take a stand on an issue or make a claim that is open to argument. You’ll spend your essay debating—and proving—your argument.

- Demonstrable : You need to be able to prove, through evidence, that your thesis statement is true. That means you have to have passages from the text and correlative analysis ready to convince the reader that you’re right.

- Specific : In most cases, successfully addressing a theme that encompasses a work in its entirety would require a book-length essay. Instead, identify a thesis statement that addresses specific elements of the work, such as a relationship between characters, a repeating symbol, a key setting, or even something really specific like the speaking style of a character.

Example: By depicting the relationship between Roderick and Madeline to be stifling and almost otherworldly in its closeness, Poe foreshadows both Madeline’s fate and Roderick’s inability to choose a different fate for himself.

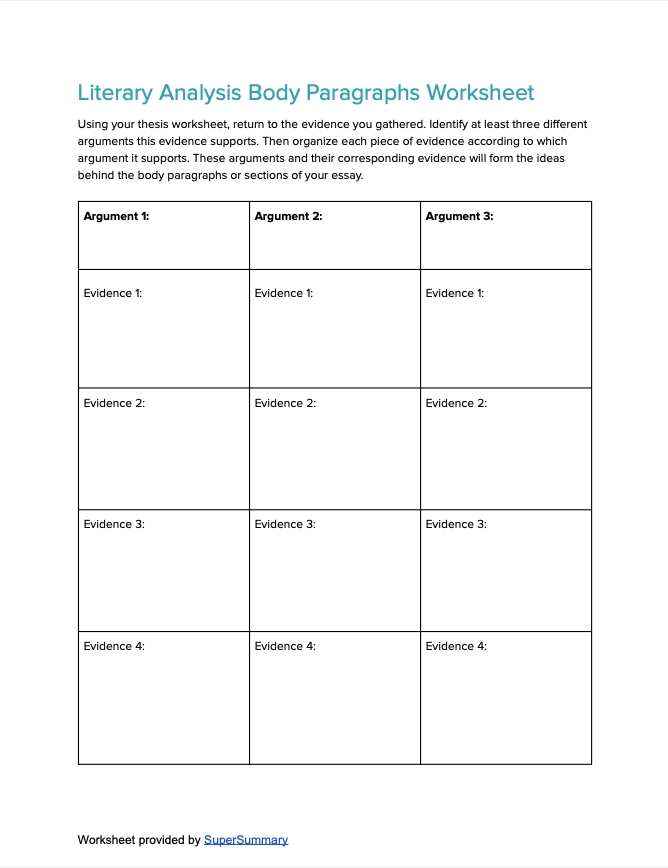

Step 6: Write an Outline

You have your thesis, you have your evidence—but how do you put them together? A great thesis statement (and therefore a great essay) will have multiple arguments supporting it, presenting different kinds of evidence that all contribute to the singular, main idea presented in your thesis.

Review your evidence and identify these different arguments, then organize the evidence into categories based on the argument they support. These ideas and evidence will become the body paragraphs of your essay.

For example, if you were writing about Roderick and Madeline as in the example above, you would pull evidence from the text, such as the narrator’s realization of their relationship as twins; examples where the narrator’s tone of voice shifts when discussing their relationship; imagery, like the sounds Roderick hears as Madeline tries to escape; and Poe’s tendency to use doubles and twins in his other writings to create the same spooky effect. All of these are separate strains of the same argument, and can be clearly organized into sections of an outline.

Step 7: Write Your Introduction

Your introduction serves a few very important purposes that essentially set the scene for the reader:

- Establish context. Sure, your reader has probably read the work. But you still want to remind them of the scene, characters, or elements you’ll be discussing.

- Present your thesis statement. Your thesis statement is the backbone of your analytical paper. You need to present it clearly at the outset so that the reader understands what every argument you make is aimed at.

- Offer a mini-outline. While you don’t want to show all your cards just yet, you do want to preview some of the evidence you’ll be using to support your thesis so that the reader has a roadmap of where they’re going.

Step 8: Write Your Body Paragraphs

Thanks to steps one through seven, you’ve already set yourself up for success. You have clearly outlined arguments and evidence to support them. Now it’s time to translate those into authoritative and confident prose.

When presenting each idea, begin with a topic sentence that encapsulates the argument you’re about to make (sort of like a mini-thesis statement). Then present your evidence and explanations of that evidence that contribute to that argument. Present enough material to prove your point, but don’t feel like you necessarily have to point out every single instance in the text where this element takes place. For example, if you’re highlighting a symbol that repeats throughout the narrative, choose two or three passages where it is used most effectively, rather than trying to squeeze in all ten times it appears.

While you should have clearly defined arguments, the essay should still move logically and fluidly from one argument to the next. Try to avoid choppy paragraphs that feel disjointed; every idea and argument should feel connected to the last, and, as a group, connected to your thesis. A great way to connect the ideas from one paragraph to the next is with transition words and phrases, such as:

- Furthermore

- In addition

- On the other hand

- Conversely

Step 9: Write Your Conclusion

Your conclusion is more than a summary of your essay's parts, but it’s also not a place to present brand new ideas not already discussed in your essay. Instead, your conclusion should return to your thesis (without repeating it verbatim) and point to why this all matters. If writing about the siblings in “The Fall of the House of Usher,” for example, you could point out that the utilization of twins and doubles is a common literary element of Poe’s work that contributes to the definitive eeriness of Gothic literature.

While you might speak to larger ideas in your conclusion, be wary of getting too macro. Your conclusion should still be supported by all of the ideas that preceded it.

Step 10: Revise, Revise, Revise

Of course you should proofread your literary analysis essay before you turn it in. But you should also edit the content to make sure every piece of evidence and every explanation directly supports your thesis as effectively and efficiently as possible.

Sometimes, this might mean actually adapting your thesis a bit to the rest of your essay. At other times, it means removing redundant examples or paraphrasing quotations. Make sure every sentence is valuable, and remove those that aren’t.

Other Resources for Literary Analysis

With these skills and suggestions, you’re well on your way to practicing and writing literary analysis. But if you don’t have a firm grasp on the concepts discussed above—such as literary devices or even the content of the text you’re analyzing—it will still feel difficult to produce insightful analysis.

If you’d like to sharpen the tools in your literature toolbox, there are plenty of other resources to help you do so:

- Check out our expansive library of Literary Devices . These could provide you with a deeper understanding of the basic devices discussed above or introduce you to new concepts sure to impress your professors ( anagnorisis , anyone?).

- This Academic Citation Resource Guide ensures you properly cite any work you reference in your analytical essay.

- Our English Homework Help Guide will point you to dozens of resources that can help you perform analysis, from critical reading strategies to poetry helpers.

- This Grammar Education Resource Guide will direct you to plenty of resources to refine your grammar and writing (definitely important for getting an A+ on that paper).

Of course, you should know the text inside and out before you begin writing your analysis. In order to develop a true understanding of the work, read through its corresponding SuperSummary study guide . Doing so will help you truly comprehend the plot, as well as provide some inspirational ideas for your analysis.

Module 8: Analysis and Synthesis

Analytical thesis statements, learning objective.

- Describe strategies for writing analytical thesis statements

- Identify analytical thesis statements

In order to write an analysis, you want to first have a solid understanding of the thing you are analyzing. Remember, when you are analyzing as a writer, you are:

- Breaking down information or artifacts into component parts

- Uncovering relationships among those parts

- Determining motives, causes, and underlying assumptions

- Making inferences and finding evidence to support generalizations

You may be asked to analyze a book, an essay, a poem, a movie, or even a song. For example, let’s suppose you want to analyze the lyrics to a popular song. Pretend that a rapper called Escalade has the biggest hit of the summer with a song titled “Missing You.” You listen to the song and determine that it is about the pain people feel when a loved one dies. You have already done analysis at a surface level and you want to begin writing your analysis. You start with the following thesis statement:

Escalade’s hit song “Missing You” is about grieving after a loved one dies.

There isn’t much depth or complexity to such a claim because the thesis doesn’t give much information. In order to write a better thesis statement, we need to dig deeper into the song. What is the importance of the lyrics? What are they really about? Why is the song about grieving? Why did he present it this way? Why is it a powerful song? Ask questions to lead you to further investigation. Doing so will help you better understand the work, but also help you develop a better thesis statement and stronger analytical essay.

Formulating an Analytical Thesis Statement

When formulating an analytical thesis statement in college, here are some helpful words and phrases to remember:

- What? What is the claim?

- How? How is this claim supported?

- So what? In other words, “What does this mean, what are the implications, or why is this important?”

Telling readers what the lyrics are might be a useful way to let them see what you are analyzing and/or to isolate specific parts where you are focusing your analysis. However, you need to move far beyond “what.” Instructors at the college level want to see your ability to break down material and demonstrate deep thinking. The claim in the thesis statement above said that Escalade’s song was about loss, but what evidence do we have for that, and why does that matter?

Effective analytical thesis statements require digging deeper and perhaps examining the larger context. Let’s say you do some research and learn that the rapper’s mother died not long ago, and when you examine the lyrics more closely, you see that a few of the lines seem to be specifically about a mother rather than a loved one in general.

Then you also read a recent interview with Escalade in which he mentions that he’s staying away from hardcore rap lyrics on his new album in an effort to be more mainstream and reach more potential fans. Finally, you notice that some of the lyrics in the song focus on not taking full advantage of the time we have with our loved ones. All of these pieces give you material to write a more complex thesis statement, maybe something like this:

In the hit song “Missing You,” Escalade draws on his experience of losing his mother and raps about the importance of not taking time with family for granted in order to connect with his audience.

Such a thesis statement is focused while still allowing plenty of room for support in the body of your paper. It addresses the questions posed above:

- The claim is that Escalade connects with a broader audience by rapping about the importance of not taking time with family for granted in his hit song, “Missing You.”

- This claim is supported in the lyrics of the song and through the “experience of losing his mother.”

- The implications are that we should not take the time we have with people for granted.

Certainly, there may be many ways for you to address “what,” “how,” and “so what,” and you may want to explore other ideas, but the above example is just one way to more fully analyze the material. Note that the example above is not formulaic, but if you need help getting started, you could use this template format to help develop your thesis statement.

Through ________________(how?), we can see that __________________(what?), which is important because ___________________(so what?). [1]

Just remember to think about these questions (what? how? and so what?) as you try to determine why something is what it is or why something means what it means. Asking these questions can help you analyze a song, story, or work of art, and can also help you construct meaningful thesis sentences when you write an analytical paper.

Key Takeaways for analytical theses

Don’t be afraid to let your claim evolve organically . If you find that your thinking and writing don’t stick exactly to the thesis statement you have constructed, your options are to scrap the writing and start again to make it fit your claim (which might not always be possible) or to modify your thesis statement. The latter option can be much easier if you are okay with the changes. As with many projects in life, writing doesn’t always go in the direction we plan, and strong analysis may mean thinking about and making changes as you look more closely at your topic. Be flexible.

Use analysis to get you to the main claim. You may have heard the simile that analysis is like peeling an onion because you have to go through layers to complete your work. You can start the process of breaking down an idea or an artifact without knowing where it will lead you or without a main claim or idea to guide you. Often, careful assessment of the pieces will bring you to an interesting interpretation of the whole. In their text Writing Analytically , authors David Rosenwasser and Jill Stephen posit that being analytical doesn’t mean just breaking something down. It also means constructing understandings. Don’t assume you need to have deeper interpretations all figured out as you start your work.

When you decide upon the main claim, make sure it is reasoned . In other words, if it is very unlikely anyone else would reach the same interpretation you are making, it might be off base. Not everyone needs to see an idea the same way you do, but a reasonable person should be able to understand, if not agree, with your analysis.

Look for analytical thesis statements in the following activity.

Using Evidence

An effective analytical thesis statement (or claim) may sound smart or slick, but it requires evidence to be fully realized. Consider movie trailers and the actual full-length movies they advertise as an analogy. If you see an exciting one-minute movie trailer online and then go see the film only to leave disappointed because all the good parts were in the trailer, you feel cheated, right? You think you were promised something that didn’t deliver in its execution. A paper with a strong thesis statement but lackluster evidence feels the same way to readers.

So what does strong analytical evidence look like? Think again about “what,” “how,” and “so what.” A claim introduces these interpretations, and evidence lets you show them. Keep in mind that evidence used in writing analytically will build on itself as the piece progresses, much like a good movie builds to an interesting climax.

Key Takeaways about evidence

Be selective about evidence. Having a narrow thesis statement will help you be selective with evidence, but even then, you don’t need to include any and every piece of information related to your main claim. Consider the best points to back up your analytic thesis statement and go deeply into them. (Also, remember that you may modify your thesis statement as you think and write, so being selective about what evidence you use in an analysis may actually help you narrow down what was a broad main claim as you work.) Refer back to our movie theme in this section: You have probably seen plenty of films that would have been better with some parts cut out and more attention paid to intriguing but underdeveloped characters and/or ideas.

Be clear and explicit with your evidence. Don’t assume that readers know exactly what you are thinking. Make your points and explain them in detail, providing information and context for readers, where necessary. Remember that analysis is critical examination and interpretation, but you can’t just assume that others always share or intuit your line of thinking. Need a movie analogy? Think back on all the times you or someone you know has said something like “I’m not sure what is going on in this movie.”

Move past obvious interpretations. Analyzing requires brainpower. Writing analytically is even more difficult. Don’t, however, try to take the easy way out by using obvious evidence (or working from an obvious claim). Many times writers have a couple of great pieces of evidence to support an interesting interpretation, but they feel the need to tack on an obvious idea—often more of an observation than analysis—somewhere in their work. This tendency may stem from the conventions of the five-paragraph essay, which features three points of support. Writing analytically, though, does not mean writing a five-paragraph essay (not much writing in college does). Develop your other evidence further or modify your main idea to allow room for additional strong evidence, but avoid obvious observations as support for your main claim. One last movie comparison? Go take a look at some of the debate on predictable Hollywood scripts. Have you ever watched a movie and felt like you have seen it before? You have, in one way or another. A sharp reader will be about as interested in obvious evidence as he or she will be in seeing a tired script reworked for the thousandth time.

One type of analysis you may be asked to write is a literary analysis, in which you examine a piece of text by breaking it down and looking for common literary elements, such as character, symbolism, plot, setting, imagery, and tone.

The video below compares writing a literary analysis to analyzing a team’s chances of winning a game—just as you would look at various factors like the weather, coaching, players, their record, and their motivation for playing. Similarly, when analyzing a literary text you want to look at all of the literary elements that contribute to the work.

The video takes you through the story of Cinderalla as an example, following the simplest possible angle (or thesis statement), that “Dreams can come true if you don’t give up.” (Note that if you were really asked to analyze Cinderella for a college class, you would want to dig deeper to find a more nuanced and interesting theme, but it works well for this example.) To analyze the story with this theme in mind, you’d want to consider the literary elements such as imagery, characters, dialogue, symbolism, the setting, plot, and tone, and consider how each of these contribute to the message that “Dreams can come true if you don’t give up.”

You can view the transcript for “How to Analyze Literature” here (opens in new window) .

- UCLA Undergraduate Writing Center. "What, How and So What?" Approaching the Thesis as a Process. https://wp.ucla.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/UWC_handouts_What-How-So-What-Thesis-revised-5-4-15-RZ.pdf ↵

- Keys to Successful Analysis. Authored by : Guy Krueger. Provided by : University of Mississippi. License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Thesis Statement Activity. Authored by : Excelsior OWL. Located at : https://owl.excelsior.edu/research/thesis-or-focus/thesis-or-focus-thesis-statement-activity/ . License : CC BY: Attribution

- What is Analysis?. Authored by : Karen Forgette. Provided by : University of Mississippi. License : CC BY: Attribution

- How to Analyze Literature. Provided by : HACC, Central Pennsylvania's Community College. Located at : https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pr4BjZkQ5Nc . License : Other . License Terms : Standard YouTube License

ENGL 2111 and 2112 World Literature: Thesis Statement

- Select Sources

- Annotated Bibliography

- Thesis Statement

- Research Paper

- About the Library